Abstract

Clinical notes represent a vast but underutilized source of information for disease characterization, whereas structured electronic health record (EHR) data such as ICD codes are often noisy, incomplete, and too coarse to capture clinical complexity. These limitations constrain the accuracy of datasets used to investigate disease pathogenesis and progression and to develop robust artificial intelligence (AI) systems. To address this challenge, we introduce Ci-SSGAN (Clinically Informed Semi-Supervised Generative Adversarial Network), a novel framework that leverages large-scale unlabeled clinical text to reannotate patient conditions with improved accuracy and equity. As a case study, we applied Ci-SSGAN to glaucoma, a leading cause of irreversible blindness characterized by pronounced racial and ethnic disparities. Trained on a demographically balanced subset of 349587 unlabeled ophthalmology notes and 2954 expert-annotated notes (drawn from an institutional corpus of 2.1 million notes), Ci-SSGAN achieved 0.85 accuracy and 0.95 AUROC, representing a 10.19% AUROC improvement compared to ICD-based labels (0.74 accuracy, 0.85 AUROC). Ci-SSGAN also narrowed subgroup performance gaps, with F1 gains for Black patients (+ 0.05), women (+ 0.06), and younger patients (+ 0.033). By integrating semi-supervised learning and demographic conditioning, Ci-SSGAN minimizes reliance on expert annotations, making AI development more accessible to resource-constrained healthcare systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) and large language models (LLMs) are transforming healthcare by uncovering insights from complex medical data that are often inaccessible in routine clinical decision-making. Domain-specific language models such as BioClinical BERT1,2,3, Med-PaLM4,5, MedGemma6, and GPT7,8,9,10 have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in processing clinical text, enabling applications from disease classification to clinical reasoning and question-answering.

Approximately 80% of clinically relevant information in electronic health records (EHRs) is found in unstructured clinical notes, which capture nuanced patient presentations, physician reasoning, and disease progression in ways that structured labels, such as ICD codes, often fail to represent11. Despite their richness, clinical notes remain largely underutilized for large-scale research and model development12. In contrast, ICD codes and other structured EHR labels are widely used but are known to be noisy13, incomplete, and often too coarse for tasks requiring fine-grained annotation. This mismatch leaves researchers with inaccurate datasets that limit both clinical insights and the reliability of AI systems built upon them.

Clinical practice generates vast amounts of unlabeled notes, and our tertiary academic center institution alone has over 250 million, including two million ophthalmology records (as illustrated in Fig. 1a). Obtaining expert labels at this scale is impractical, leaving abundant data largely unusable for supervised learning. Expert clinical grading remains the gold standard for disease classification, yet obtaining such labels at scale is costly and time-consuming. However, fully supervised models, including BERT variants1,2,14, require large, high-quality labeled datasets that are rarely available for specialized disease classification tasks.

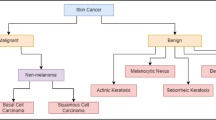

a Abundant unlabeled ophthalmology notes compared with limited expert annotations. b Ci-SSGAN generator combines unlabeled text embeddings (blue arrow), demographics (orange arrow), and noise (dashed black arrow) to produce synthetic data, with the discriminator classifying glaucoma subtypes and output evaluated to ensure fairness by measuring each subgroup disparities. Non-GL=non-glaucoma, OAG/S= open angle glaucoma/suspect, ACG/S= angle closure glaucoma/suspect, XFG/S= exfoliation glaucoma/syndrome, PDG/S= pigmentary dispersion glaucoma/syndrome, and SGL= secondary glaucoma. R= real, F= fake. Parts of this figure were created with BioRender.com.

Furthermore, EHR labels in their current form can reinforce biases and overlook important subgroups, especially for diseases with complex subtypes or variable presentations. When combined with limited labeled data, these biases reduce model reliability and underscore the need for frameworks that harness unstructured clinical data while promoting equitable performance. When training data lacks demographic diversity or contains label noise, supervised models perform substantially worse11,15,16. For example, prior studies have shown that feature-dependent label noise, annotator disagreements, or limited diversity in training corpora can degrade performance, and these effects are not fully corrected by fine-tuning17,18.

To address label scarcity, systemic biases, and the underutilization of abundant unlabeled clinical notes, we propose Ci-SSGAN (Clinically Informed Semi-Supervised Generative Adversarial Network), a framework explicitly designed to ensure equitable performance across demographic groups (as illustrated in Fig. 1b). The framework achieves higher accuracy with substantially fewer labeled examples. It ensures reliable outcomes and reduces disparities by conditioning semi-supervised generation on unlabeled clinical text and patient characteristics. Unlike standard semi-supervised GANs19,20 which use only noise as their generator inputs, Ci-SSGAN introduces three key innovations: (1) a clinically informed generator that integrates embeddings from unlabeled clinical text with demographic conditions and noise, creating synthetic data that is both clinically meaningful and demographically representative; (2) multi-conditional learning that explicitly incorporates race, gender, and age to combat dataset imbalance and ensure consistent performance across all subgroups; and (3) a systematic equity framework using our proposed Parity Violation (PV) score to quantify and minimize disparities in positive and negative predictive values across demographics.

We evaluated Ci-SSGAN in glaucoma subtype detection, a disease that highlights both the opportunities and challenges of AI in healthcare. Glaucoma is the leading cause of irreversible blindness worldwide, projected to affect 80 million people by 2040 with considerable racial, ethnic and socioeconomic disparities making it a compelling test case for equitable AI. Additionally, ICD coding for glaucoma classification has particularly poor specificity21 (less than 50%) and achieves only ~81% accuracy22, with systematic undercoding, overcoding, and subtype misclassification that undermine reliable labeling. Glaucoma exemplifies both the global burden of disease, and the equity challenges that Ci-SSGAN aims to address. Pronounced disparities exist across race, gender, and age groups23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30, making it a compelling real-world test case for equitable AI.

This combination of global burden, pronounced disparities and imperfect structured labels, makes glaucoma an ideal real-world setting to evaluate Ci-SSGAN. By leveraging over two million unlabeled ophthalmology notes alongside a smaller expert-annotated set, our framework demonstrates how semi-supervised learning can address the labeled-data bottleneck while promoting equitable performance across subgroups. Although glaucoma serves as our case study, the approach can be generalized to other diseases where unlabeled notes are abundant but equitable performance remains elusive.

Results

Patients demographics and clinical characteristics

The labeled dataset comprised 2954 notes for 1105 patients (53.5% female) and the unlabeled dataset contained 349587 notes for 108574 patients (59% female) who received care at the Massachusetts Eye and Ear (MEE) ophthalmology department from May 2015 to December 2024.

The participants’ age at the time of study ranged from 30 to 90 years for both datasets, with median of 62 and 68 for labeled and unlabeled datasets, respectively. The patients’ demographics in the labeled dataset include 41.7% White or Caucasian, 29.6% Black or African American, and 28.7% Asian. The unlabeled dataset showed similar racial distribution with 40.2% White or Caucasian, 19.5% Black or African American, and 40.3% Asian patients. Table 1 shows demographics and clinical characteristics of the patients in both datasets.

Model performance and equity analysis

To comprehensively demonstrate the advantages of our proposed semi-supervised learning method, We trained all methods with 25%, 50%, and 100% of the labeled notes and evaluated at the patient level. Unless stated otherwise, higher is better for Accuracy/F1/AUROC/AUPRC, and lower is better for the Parity-Violation (PV) score. The labeled dataset (1105 patients, 2954 notes) was split into 90% for model development (1000 patients, 2660 notes) and 10% as a held-out test set (105 patients, 294 notes). Within the 90% development partition, we performed stratified 5-fold cross-validation at the patient level, ensuring demographic balance across folds. For each fold, approximately 80% of the development patients were used for training, 10% for early stopping, and 10% for fold-specific validation. This process yielded five independently trained models per method and per labeled data fraction. All five models from each configuration were evaluated on the identical held-out test set, and reported metrics represent mean ± standard deviation across the five models’ predictions on this fixed test set. We evaluated the performance of Ci-SSGAN at each labeled data fraction against two fully supervised models (Base BERT1 and BioClinical BERT2), as well as the standard SSGAN19,20. For classification, we defined six outcome classes: non-glaucoma (Non-GL), open-angle glaucoma/suspect (OAG/S), angle-closure glaucoma/suspect (ACG/S), exfoliation glaucoma/syndrome (XFG/S), pigmentary glaucoma/syndrome (PDG/S), and secondary glaucoma (SGL). These categories were chosen to reflect clinically relevant subtypes with sufficient representation for model training and evaluation.

Performance improvements with Ci-SSGAN were consistent in both note-level and patient-level analyses (see Fig. 2, Table 2 and Supplementary Figs. S1 and S2), confirming the robustness of its gains over Base BERT, Bio BERT, and standard SSGAN regardless of evaluation granularity. Across all labeled data fractions, Ci-SSGAN achieved the highest Accuracy, AUC-PR, and AUCROC, with improvements over Base BERT and Bio BERT particularly pronounced in low-data settings (AUC-PR \(+\)0.091 and \(+\)0.092 at 25%). Standard deviations across 5 folds were consistently low, indicating stable performance across runs.

a Racial groups, b Gender groups, and c Age groups using 25% of the labeled data. Left panels show accuracy (solid bars) and F1-score (hatched bars) for each subgroup and overall performance. Right panels present corresponding parity violation scores, indicating fairness across demographic subgroups. Ci-SSGAN consistently achieves higher accuracy and F1-scores with lower parity violations compared to other models. The results are presented on five CV folds. Acc Accuracy, F1 = F1- macro.

When utilizing only 25% of labeled data (Fig. 2), Ci-SSGAN achieved notable gains over Base BERT, increasing overall accuracy from 0.78 to 0.843 and F1 score from 0.747 to 0.809 (P < 0.001). With 100% of labeled data (Supplementary Fig. S3), overall Accuracy and F1 score rose further, from 0.844 to 0.873 and from 0.81 to 0.86, respectively, compared with Base BERT (P < 0.001).

Performance was stratified by demographic subgroups (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. S3). To evaluate fairness, we applied our PV score, which measures disparities in positive and negative predictive values across groups (see Methods). Lower PV scores reflect more equitable performance.

For race subgroups, with 25% labels (Fig. 2a), Ci-SSGAN achieved the highest Accuracy/F1 across Asian, Black, and White cohorts; its PV was 0.056, lower than Base BERT 0.133 and Bio-Clinical BERT 0.158, but higher than SSGAN 0.027. With 100% labels (Supplementary Fig. S3a), Ci-SSGAN again led on Accuracy/F1 and achieved PV = 0.023, matching SSGAN 0.023 and below Base BERT 0.032 and Bio-Clinical BERT 0.077.

For gender subgroups, with 25% labeled data (Fig. 2b), Ci-SSGAN achieved the highest predictive performance (Accuracy/F1) for females (0.830/0.802) and males (0.857/0.809), exceeding SSGAN, Base BERT, and Bio-Clinical BERT. For fairness, Ci-SSGAN was second-best (PV = 0.007), below Base BERT (0.037) and Bio-Clinical BERT (0.066) and slightly above SSGAN (0.003). With 100% labeled data (Supplementary Fig. S3b), Ci-SSGAN again led on Accuracy/F1 (female 0.895/0.897; male 0.850/0.840; overall 0.873/0.860) and achieved the lowest PV (0.003 vs SSGAN 0.014, Base BERT 0.020, Bio-Clinical BERT 0.028).

Across age strata (years), Ci-SSGAN consistently achieved the strongest predictive performance. With 25% labeled data (Fig. 2c), accuracy/F1 were 0.836/0.707 for 30–55 y, 0.844/0.817 for 55–70 y, and 0.843/0.807 for ≥70 y; corresponding values were 0.784/0.700, 0.794/0.786, and 0.792/0.748 for SSGAN; 0.789/0.674, 0.749/0.656, and 0.790/0.765 for Base BERT; and 0.787/0.649, 0.730/0.689, and 0.749/0.720 for Bio-Clinical BERT. Fairness, assessed by the PV score, also favored Ci-SSGAN at 25% (PV = 0.025 vs SSGAN 0.063, Bio-Clinical BERT 0.088, Base BERT 0.211). With 100% labels (Supplementary Fig. S3c), Ci-SSGAN achieved higher accuracy and F1-scores across all age groups; its PV was 0.041, lower than Bio-Clinical BERT (0.095) and SSGAN (0.075), and slightly higher than Base BERT (0.035).

Class-wise performance evaluation of the model using PR and ROC analyses demonstrated that Ci-SSGAN achieved the highest overall AUC-PR (0.893), despite an AUC-ROC of only 0.001 below Base BERT (Fig. 3). Ci-SSGAN achieved higher precision and recall across most classes, with notably high AUC-PR scores for OAG/S (0.932), ACG/S (0.961), and XFG/S (0.919). For SGL, the rarest class, Ci-SSGAN achieved an AUC-PR of 0.714, substantially outperforming other models. These gains were consistent at 100% labeled data (Supplementary Fig. S4).

a Ci-SSGAN, b SSGAN, c Base BERT, and d Bio BERT for multi-class glaucoma subtype and non-glaucoma classification. Each curve shows performance for a specific class, including five glaucoma subtypes and non-glaucoma, with a “Random” baseline for reference showing as dashed line. Ci-SSGAN is designed to condition the generator based on clinical context, while SSGAN is designed without clinical context. Base BERT and Bio BERT are fully supervised baselines. The results are presented on five CV folds. All models were trained using 25% of the labeled data.

Model interpretability and reliability analysis

To fully characterize models’ behavior, we analyzed feature representation patterns, predictive uncertainty, and token-level interpretability.

The UMAP visualizations in Fig. 4 show that Ci-SSGAN learns more distinct and well-separated patient-level clusters across demographic groups compared to regular SSGAN. Each point represents a patient embedding, derived by averaging note-level feature representations from the discriminator’s final shared layer. Clinically, these clusters correspond to patients with similar disease characteristics, demographic profiles, and glaucoma subtypes, indicating that Ci-SSGAN organizes patients into clinically meaningful groups rather than overlapping latent spaces. These visualizations provide empirical validation that the 3-dimensional demographic conditioning vector effectively biases generated samples despite its lower dimensionality compared to noise (100D) and text embeddings (768D). Quantitatively, Ci-SSGAN achieved higher silhouette scores for race (0.68), gender (0.72), and age (0.57) compared to SSGAN (0.52, 0.26, and 0.17), reflecting clearer group separation and reduced feature overlap. This improvement is especially pronounced for gender, where Ci-SSGAN’s score (0.72) was significantly higher than SSGAN’s (0.26; P < 0.05), demonstrating that demographic-specific information is better preserved in the learned feature space when clinical context is incorporated. This demographic separation demonstrates that the generator successfully learns to produce samples that reflect their conditioning demographics, preventing mode collapse toward majority populations (Supplementary Fig. S15).

a, d colored by race, b, e gender, and c, f age groups. Each point is a sample, with proximity reflecting similarity in the 256-dimensional discriminator feature space. Ci-SSGAN produces more compact, well-separated clusters across demographics, indicating improved feature organization when incorporating clinical context. Features are from the best fold trained on 25% labeled data.

Across race, gender, and age subgroups, Ci-SSGAN consistently exhibited the lowest predictive uncertainty (Fig. 5), with median entropy values of 0.243 at 25% labeled data and 0.263 at 100% labeled data, compared with SSGAN (0.5 and 0.6), Base BERT (0.727 and 0.458), and Bio BERT (0.687 and 0.447).

a race, b gender, and c age groups. Light colors indicate 25% training data; dark colors indicate 100% data. Ci-SSGAN (gray) maintains lowest uncertainty ( < 0.2 entropy) regardless of data size, while BERT models (red/green) show high uncertainty with 25% data (0.6–1.4 entropy) that reduces substantially with 100% data (0.2–0.4 entropy). SSGAN (blue) exhibits intermediate performance. The horizontal line indicates the median and the error bars represent the minimum and maximum values observed for each group.

When increasing the labeled fraction from 25% to 100%, the change in median entropy was minimal for Ci-SSGAN (\(-\)5.3%), indicating stable confidence even in low-label regimes, whereas SSGAN showed a 16.9% reduction, Base BERT 34.1%, and Bio BERT 32.0%, reflecting greater dependency on labeled data for uncertainty reduction. This trend was consistent across racial groups (Asian, Black, White), gender groups (male, female), and age ranges (30–55, 55–70, ≥70), with the performance gap most pronounced under the 25% labeled data condition. Figure 5 illustrates these results.

Clinically, these results indicate that Ci-SSGAN not only improves classification performance but also delivers markedly more reliable predictions. Supplementary Fig. S5 supports this by showing class-wise probability radar plots where Ci-SSGAN predictions form tightly clustered, high-confidence outputs (mean confidence = 0.990, ACC = 0.890) compared with the more dispersed, less certain outputs of standard SSGAN (mean confidence = 0.975, ACC = 0.829).

Gradient-weighted token attribution, averaged across five folds, shows model-specific patterns of feature use (Fig. 6). For display, we first select the top 20 tokens per model after HIPAA filtering and then renormalize their scores to sum to 1.0 within each model. Under this convention, Ci-SSGAN exhibits a concentrated profile, with the wordpiece “igmentary” (from pigmentary glaucoma) accounting for 0.478 of the displayed attribution, followed by “glaucoma” (0.102) and “pseudoexfoliation” (0.019), consistent with clinically focused conditioning. SSGAN is more diffuse (maximum 0.195 for “fovea”), Base BERT the most dispersed (maximum 0.103 for “cyclophotocoagulation”), and Bio-Clinical BERT similarly diffuse (maximum 0.073). The maximum displayed attribution share is 6.5-fold higher for Ci-SSGAN than for Bio-Clinical BERT (0.478 vs 0.073), suggesting more concentrated, disease-oriented token selection with architectural clinical conditioning. Because the plot reflects relative attribution among the top tokens aggregated across notes, it should be interpreted as a comparative profile rather than evidence of token frequency; per-class token profiles are provided in Supplementary Fig. S6.

Wordpiece-level attributions are normalized per note to sum to 1 and then averaged across notes (5-fold CV). To avoid rare-token artefacts, only tokens that appear in ≥ 50 notes ( ≥ 100 total occurrences) are considered. Bars show the mean normalized attribution share for the top 20 tokens per model. Values printed on the bars represent the distribution of attribution mass among the displayed top tokens, not corpus-level frequency. Models trained by 25% of labeled data were used to extract these tokens.

Prediction performance of Ci-SSGAN subtype detection versus ICD code labels on the test dataset

We further demonstrate that our model can outperform ICD code-based labels, using glaucoma subtype detection as a test case which suffer from coarse and noisy ICD codes, frequently requiring re-annotation. Ci-SSGAN yielded confusion matrices with reduced cross-subtype misclassifications and closer alignment with expert clinical grading compared with ICD-based labels (Fig. 7). Of the 105 test patients, 94 had ≥1 ICD code that mapped unambiguously to a glaucoma subtype; the remaining 11 lacked a mapped code or had only non-specific/suspect codes and were excluded from the ICD confusion matrix.

a Ci-SSGAN predictions derived from free-text clinical notes. b ICD-based subtype assignments derived from structured billing codes. Ci-SSGAN demonstrates fewer cross-subtype misclassifications and stronger concordance with expert labels across all six subtypes: Non-GL, OAG/S, ACG/S, XFG/S, PDG/S, and SGL. ICD-based labels were assigned using predefined diagnostic code mappings, with a prioritization hierarchy applied when multiple codes were present. Of 105 patients in the test cohort, 94 had at least one valid ICD code. The remaining 11 had no linked billing record or only non-specific/suspect codes (e.g., H40.9/365.9), which we do not use for subtype assignment.

Ci-SSGAN achieved higher performance than ICD-based labels across all evaluation metrics (Fig. 8 and Supplementary Fig. S7). Overall accuracy was significantly higher for Ci-SSGAN (0.853) compared with ICD-based labels (0.744, P < 0.05), with substantial per-class improvements in Non-GL (0.818 vs. 0.636, P < 0.05), OAG/S (0.955 vs. 0.773, P < 0.05), and ACG/S (0.929 vs. 0.500, P < 0.05). Similarly, the overall F1 score was greater for Ci-SSGAN (0.855 vs. 0.744, P < 0.05), with the largest margins in Non-GL (0.750 vs. 0.519, P < 0.05), OAG/S (0.857 vs. 0.739, P < 0.05), and ACG/S (0.929 vs. 0.636, P < 0.05).

Each bar represents performance for a specific class, with the “Overall” category summarizing all classes. Ci-SSGAN uses both labeled and unlabeled data with clinical context, whereas ICD code labels rely solely on diagnosis codes from medical records. Improvements were most pronounced in challenging subtypes such as primary angle-closure glaucoma (ACG/S), open-angle glaucoma (OAG/S), and Non-GL cases. AUROC and AUCPR calculated using one-vs-rest strategy with macro-averaging across six glaucoma classes.

From a clinical standpoint, the improvements in AUROC and AUPRC are substantial. Relative to ICD, Ci-SSGAN achieved a higher AUROC (0.949 vs 0.847, P < 0.01), with per-class gains in Non-GL (\(+\)0.151), OAG/S (\(+\)0.117), and ACG/S (\(+\)0.208) (P < 0.05 each). AUPRC (which is sensitive to class prevalence and emphasizes precision at high recall) also improved overall (0.847 vs 0.619, P < 0.01). The largest per-class AUPRC gains were observed for Non-GL (\(+\)0.401, indicating fewer false positives across glaucoma subtypes), OAG/S (\(+\)0.262), and ACG/S (\(+\)0.309) (P < 0.05 each). Although AUPRC is particularly informative for rarer subtypes, we report it for all classes, including the majority Non-GL class, to provide a complete per-class view. Overall performance metrics for all models are summarized in Table 3.

Benchmarking

We benchmarked Ci-SSGAN (trained on 100% of labeled data) against state-of-the-art large language models including GPT-4o8, Med-Gemma 4B6, and LLaMA-3.2-3B31 using zero-shot classification on the test set of 294 clinical notes from 105 patients (Table 4). All clinical notes were de-identified and notes longer than 512 tokens were split into overlapping segments of 512 tokens (with 64-token overlap) to preserve context continuity. To ensure HIPAA compliance, GPT-4o was accessed through Mass General Brigham’s AI Zone platform, a secure environment built on Microsoft Azure AI Foundry and approved for protected health information processing, with model parameters configured as temperature=0.8, top-p = 1.0, and maximum token length of 4096. Med-Gemma 4B and LLaMA-3.2-3B were downloaded from Hugging Face and deployed locally using identical prompts. Ci-SSGAN achieved higher overall performance across all evaluation metrics (accuracy: 0.840, F1: 0.843, AUC-ROC: 0.949, AUC-PR: 0.852), substantially outperforming GPT-4o (accuracy: 0.641, F1: 0.655, AUC-ROC: 0.785, AUC-PR: 0.515) with absolute improvements of 19.9 percentage points in accuracy, 18.8 percentage points in F1 score, 16.4 percentage points in AUC-ROC, and 33.7 percentage points in AUC-PR. GPT-4o showed marginally higher accuracy than Ci-SSGAN for the XFG/S subtype (0.752 vs. 0.750), while Ci-SSGAN outperformed all LLMs across the remaining five glaucoma subtypes.

Human-AI comparative validation study

To evaluate clinical validity, we assessed model performance against independent annotations from three fellowship-trained glaucoma specialists on 218 clinical notes (details in Supplementary Figs. S8 and S9). Model-reviewer concordance varied by grader (Table 5): accuracy 0.591–0.842 (mean: 0.728), Cohen’s κ 0.434–0.788 (mean: 0.621), and macro F1-score 0.624–0.782 (mean: 0.722). Despite variability in class assignments, the model maintained strong discriminatory ability across all reviewers (AUROC: 0.814–0.948, mean: 0.899; AUCPR: 0.650–0.851, mean: 0.770). This variation reflects inherent subjectivity in glaucoma classification, as inter-rater reliability among human experts showed moderate-to-substantial agreement (pairwise Cohen’s κ: 0.646–0.831, mean: 0.74; Supplementary Table S2). Detailed per-reviewer metrics are in Supplementary Fig. S10.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that clinically informed semi-supervised generative modeling can help address two long-standing challenges in healthcare AI: the scarcity of reliable labels and the inequities in subgroup performance, by harnessing abundant unlabeled clinical notes. Glaucoma exemplifies the urgency of these challenges and the potential of Ci-SSGAN to mitigate them, particularly for under-represented groups such as Black patients, females, and younger individuals who experience worse disease outcomes23,24,29,30. Biases in structured EHR labels, especially when combined with limited annotations, have been shown to undermine model reliability11,15,16, and prior work highlights how feature-dependent noise, annotator disagreement, and limited diversity in training corpora degrade performance in ways that fine-tuning alone cannot resolve17,18. While semi-supervised GANs have attempted to address data scarcity, they typically depend on noise or broad demographic inputs19,20,32,33, reducing their ability to capture clinically meaningful signals. Unlike standard SSGAN models used in image classification19,20,33, where the generator is conditioned only on noise or limited demographics, Ci-SSGAN introduces three key innovations: integration of note embeddings to capture clinical context, multi-conditional learning to counter subgroup imbalance, and an explicit fairness objective using the PV metric.

Across varying amounts of labeled data, Ci-SSGAN consistently outperformed both supervised and semi-supervised baseline models (Table 2 and Figs. 2 and 3). Its conditional generation on clinical embeddings enabled robust improvements even with limited annotations, and these benefits extended to high-label settings where other models typically plateau. For example, with only 25% labeled data, Ci-SSGAN achieved an accuracy of 0.871 ± 0.03, surpassing SSGAN (0.859 ± 0.04) and Base BERT (0.824 ± 0.05), alongside a substantial AUC-PR improvement ( + 0.091 over BioBERT). These advantages persisted as labeled data increased with the framework achieving over 9% higher precision–recall performance compared to standard supervised approaches, illustrating its ability to extract value from unlabeled notes while maintaining equitable subgroup performance. We also benchmarked Ci-SSGAN against three large general-purpose medical language models (GPT-4o8, Med-Gemma 4B6, and LLaMA-3.2-3B31) to contextualize its task-specific performance (Table 4). Across key metrics, Ci-SSGAN achieved 19.9 to 33.7 percentage-point higher accuracy and F1-scores relative to GPT-4o, reflecting the benefit of domain-specific semi-supervised training. GPT-4o showed a slight edge on the XFG/S subtype (0.752 vs. 0.750), consistent with its broader linguistic coverage. Despite being medical-domain specific, Med-Gemma 4B showed limited zero-shot performance (accuracy: 0.160), demonstrating that even specialized medical LLMs require task-specific adaptation for fine-grained clinical classification. These results highlight that integrating structured clinical context and demographic conditioning can improve task-specific performance for ophthalmology-specific note classification tasks compared with general medical LLMs.

Importantly, Ci-SSGAN semi-supervised design enables remarkable label efficiency. Comparing 25% to 100% labeled data (Supplementary Table S1), performance gains were modest (accuracy +0.036, F1 + 0.039, AUROC + 0.007, AUCPR + 0.026), indicating that the model extracts near-optimal information from unlabeled notes. This efficiency lowers the barrier to AI development, enabling strong results without exhaustive annotations, which is particularly valuable for rare diseases, underrepresented groups or when resources are limited. Notably, improvements remained substantial even with 100% labeled data (Table 3), not contradicting the label-efficiency advantage but highlighting complementary effects: in low-label regimes, Ci-SSGAN leverages unlabeled notes to compensate for limited supervision, while in high-label regimes it combines full supervised signal with adversarially generated diversity, pushing beyond the ceiling of purely supervised models. While BERT variants plateau once additional labels no longer reduce uncertainty, Ci-SSGAN continues to improve by preserving rare subtypes and demographic variability, a capability enabled by our strategic racial balancing approach combined with stratified augmentation across race, gender, and age groups (see Methods). This multi-level balancing strategy ensures adequate representation of Black and Asian patients, who are disproportionately affected by glaucoma but historically underrepresented in medical AI datasets23,24,25,27,28,29,30,34, as well as intersectional subgroups that may have unique disease presentations. By conditioning the generator on demographics sampled from this intentionally balanced distribution rather than the original imbalanced institutional data (75% White, 7% Black, 5% Asian), the model maintains representation of rare disease-demographic combinations across all subgroups, preventing the mode collapse toward majority populations that commonly occurs in GANs trained on imbalanced data35,36. This demographic conditioning mechanism, combined with our diversity loss and clinical consistency objectives, ensures that synthetic samples reflect the full spectrum of patient presentations rather than converging on the most common patterns, explaining why Ci-SSGAN’s margin of improvement can appear larger at 100% labeled data even though relative efficiency is most impactful with limited data.

Ci-SSGAN also produced more discriminative feature representations and reduced predictive uncertainty (see Supplementary Fig. S5), supporting reliable outputs across demographic subgroups. Attribution analysis further showed that the model concentrated attention on disease-specific terms (e.g., “pigmentary,” “pseudoexfoliation”), with over six-fold greater attribution focus compared to Bio BERT. This sharper reliance on clinically meaningful features provides mechanistic insight into why the framework achieves both improved performance and interpretability. Importantly, while BERT models became increasingly confident only as more labels were added, Ci-SSGAN maintained the lowest overall uncertainty and preserved sensitivity to rare subtypes. This balance between certainty and diversity prevents overconfident errors and underscores the framework’s design to promote equitable performance.

When benchmarked against ICD-based glaucoma coding, Ci-SSGAN showed markedly higher concordance with expert grading (Table 3 and Fig. 8), particularly for open-angle and angle-closure subtypes and in distinguishing non-glaucoma cases. These results highlight how leveraging unlabeled notes can overcome the coarse granularity and systematic misclassification inherent to structured coding. From an equity perspective, PV scores were substantially reduced across race, gender, and age, with notable gains for Black patients (\(+\)6.7% F1 vs. Bio BERT), illustrating that conditioning generative models on unlabeled clinical text offers a viable path to mitigating potential systemic biases.

Although our case study focused on glaucoma, the architecture is conceptually applicable to other medical conditions with abundant clinical documentation but limited labels, such as diabetic retinopathy staging37,38,39, age-related macular degeneration classification40,41,42, cardiac disease risk stratification43,44,45, or psychiatric disorder classification46,47,48. The main limitation preventing validation in these areas is the lack of large-scale, expert-annotated note datasets, which constrains systematic evaluation beyond glaucoma. While further validation will be needed once such resources become available, our results suggest that multi-conditional semi-supervised learning on unstructured text has the potential to improve accuracy, reliability, and fairness in diverse healthcare contexts.

We explicitly acknowledge several limitations we faced in this study. Data were drawn from a single academic health system; external validation is required to ensure generalizability across institutions and note types. Smaller demographic groups (Hispanic/Latinx, Indigenous, multi-racial) were underpowered and should be included in future equity analyses. Expert annotations, while highly consistent (kappa \(\approx\) 0.90), may reflect prevailing clinical biases. From a translational perspective, future deployment of Ci-SSGAN would likely require integration into clinical decision-support systems (CDS) with careful evaluation of human–AI collaboration strategies (e.g., clinician override, uncertainty visualization, and workflow co-design), to ensure safe and equitable use in practice. In the present study, we implemented several rigorous validation strategies to establish reliability: (1) expert adjudication by six fellowship-trained glaucoma specialists who independently labeled the test set (Cohen’s κ = 0.90), providing gold-standard ground truth; (2) prospective human-in-the-loop validation comparing model predictions against independent annotations from three fellowship-trained glaucoma specialists across 218 clinical notes, demonstrating substantial human-AI concordance (mean accuracy=0.728, Cohen’s κ = 0.621, AUROC = 0.899; See Table 5 and Supplementary Fig. S10) that aligns with the moderate-to-substantial inter-rater reliability observed among human experts themselves (mean κ = 0.74); (3) comparison with ICD-based coding to assess concordance with existing clinical documentation systems (Table 3 and Fig. 8); and (4) comprehensive fairness evaluation across demographic subgroups to identify potential biases. These analyses collectively provide strong evidence of technical performance and algorithmic fairness under controlled conditions. Nevertheless, prospective human–machine comparative studies remain essential to determine clinical utility. Such studies should evaluate clinician-AI collaborative workflows with respect to diagnostic accuracy, time efficiency, and decision support; assess real-world outcomes such as time-to-diagnosis, referral appropriateness, and vision preservation; and examine implementation factors including user acceptance, workflow integration, automation bias, and safety through failure mode and uncertainty analyses. While conducting such trials will require institutional review board approval, EHR integration, and significant clinical resources beyond the scope of this methodological development, the current work provides the technical foundation and empirical justification for future prospective validation efforts. To further improve interpretability, the next version of Ci-SSGAN will incorporate an auxiliary reasoning head designed to generate explicit rationales for each classification decision. This head will be trained jointly with the discriminator to map latent text representations to interpretable concepts or concise natural-language explanations, thereby linking predictive accuracy to clinical transparency. In parallel, future extensions could integrate imaging modalities such as OCT and visual field data with clinical text to enable multimodal glaucoma modeling and progression prediction, as demonstrated in our prior hybrid structural-functional fusion frameworks49. Integrating such structured reasoning modules will enable clinicians to review not only the predicted subtype but also the model’s supporting rationale as an essential step toward trustworthy deployment of generative models in clinical practice. While our UMAP analysis (Fig. 4) and subgroup performance metrics (Figs. 2 and 3) provide strong empirical evidence that 3-dimensional demographic conditioning effectively biases generated samples toward their conditioned demographics, future work could incorporate explicit auxiliary demographic prediction as an additional discriminator head. This would provide direct supervision for demographic coherence and enable quantitative assessment of whether generated samples accurately reflect their conditioning demographics, complementing the current implicit validation through the discriminator’s conditional evaluation of sample realism. Such explicit demographic supervision could further improve fairness by ensuring generated samples maintain appropriate demographic characteristics throughout training.

Building on these considerations, future work should include multi-center validation to ensure robustness across diverse populations and prospective clinical evaluation to measure outcomes such as time-to-diagnosis and vision preservation. In addition to methodological safeguards such as differential-privacy training and threat modeling, improved note-derived annotations could directly enable construction of more accurate cohorts for large-scale epidemiologic and genetic studies, as well as better-powered clinical trials. Integration into CDS systems could facilitate more accurate patient labeling, risk stratification, and referral triaging, thereby enhancing early detection and timely care. Comprehensive fairness audits, including intersectional subgroup analyses and debiasing strategies, remain essential to address residual disparities. Finally, co-designed workflows with clinicians and patients (particularly in under-resourced communities) will be key to translating technical advances into equitable care delivery.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that semi-supervised generative model, when grounded in clinical context and demographic information, can simultaneously improve accuracy and equity in healthcare AI. By leveraging abundant unlabeled notes, Ci-SSGAN reduces dependence on large, annotated datasets and helps preserve subgroup performance that often degrades in low-data settings. These findings highlight the broader potential of clinically informed semi-supervised learning to address both data scarcity and systemic bias in real-world applications.

Methods

The Institutional Review Board at Mass General Brigham (MGB) approved this study, which adhered to the ethical guidelines outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for research involving human participants. Given the retrospective design, the requirement for informed consent was waived.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

In our Mass Eye and Ear (MEE) dataset, which encompasses over 250 million clinical notes, we included notes from the ophthalmology departments comprising 3.2% of total notes. We filtered the notes with dates between May 2015 and December 2024. The majority of physician-generated notes are concentrated in two primary categories: “Progress Note” and “Assessment and Plan Note,” collectively totaling over 90 million notes. The notes vary in length with minimum and maximum lengths of 1 and 386561 characters, respectively (interquartile range = 455–1672 characters). For analysis, we applied the following inclusion criteria: (1) note length between 200 and 5000 characters (approximately 40–1100 tokens); (2) patients aged ≥30 years; and (3) race limited to White or Caucasian, Black or African American, and Asian patients due to sample size considerations for other demographic groups. A sliding window approach was used for longer notes exceeding the tokenizer’s maximum length of 512 tokens to split them into overlapping chunks of 512 tokens (overlap = 64) to ensure context continuity. The resulting source corpus comprises 2129171 notes from 327814 patients (88.2% White, 6.8% Black or African American, 5% Asian), from which we derived two distinct datasets for model training: (1) an unlabeled dataset of 349587 notes from 108574 patients, selected through stratified random sampling to ensure demographic balance across race, gender, and age groups; and (2) a labeled dataset created through expert curation as described below. Supplementary Fig. S11 shows the department specialties, note type, and note length distribution in the source corpus.

Clinical note curation and expert labeling

Notes were initially filtered by glaucoma-related keywords extracted from the literature and online ophthalmology resources50. Using stratified random sampling, we selected at least 50 patients per glaucoma subtype with each patient having a minimum of two notes, balanced by subtype, race, and sex, yielding 1117 patients with 4321 notes. Six fellowship-trained glaucoma specialists independently reviewed the 4321 notes, with each note reviewed by at least two clinicians to assign diagnosis (glaucoma/suspect, non-glaucoma, or insufficient information) and, when applicable, glaucoma subtype classification: open-angle glaucoma/suspect (OAG/S; including normal- tension glaucoma, high-tension glaucoma, ocular hypertension, and open-angle suspect), angle-closure glaucoma/suspect (ACG/S; including angle-closure suspect), exfoliation glaucoma/syndrome (XFG/S), pigmentary dispersion glaucoma/syndrome (PDG/S), and secondary glaucoma (SGL). Discordant cases were adjudicated by consensus review. Inter-rater agreement on a 10% subset yielded Cohen’s kappa (κ)=0.90, indicating excellent concordance. Following clinical review, notes were further filtered by inclusion criteria (200-5000 characters, age ≥ 30 years, race limited to Asian/Black/White) and exclusion criteria (duplicated, empty, or templated notes), resulting in 2954 notes from 1105 patients. Notes with diagnostic uncertainty (N = 81) or insufficient information (N = 30) were excluded during this step. The final curated set comprised 2954 notes from 1105 patients distributed across six categories: OAG/S (N = 1211), ACG/S (N = 174), XFG/S (N = 232), PDG/S (N = 383), SGL (N = 146), and Non-GL (N = 808), serving as the ground truth for model training and evaluation. The workflow for dataset generation, including data collection, preprocessing, and labeling, is shown in Supplementary Fig. S12. Annotations were collected and managed using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture), a secure, HIPAA-compliant web-based platform provided by MGB, which ensured standardized data entry, audit trails, and secure storage of all reviewer assessments. Annotation was performed at the note level, with each clinical note receiving an independent diagnostic label based on the clinical information documented at that specific encounter. Patients with multiple notes could have different labels across time points, reflecting disease progression, diagnostic refinement, or clinical evolution. Among the 1105 patients, 132 patients (12%) exhibited diagnostic transitions across sequential notes (Supplementary Fig. S13), with the most common patterns including progression from Non-GL to OAG/S (43 patients). For patient-level evaluation, a predefined priority hierarchy (XFG/S > PDG/S > SGL > ACG/S > OAG/S > Non-GL) was applied to assign a single patient-level label when multiple subtypes were present across notes, prioritizing the most specific and clinically significant diagnosis.

Structured labels were also derived from ICD-10/ICD-9 billing codes (pre- and post-October 2015) to construct an ICD-based baseline. Mapping was: XFG/S: H40.14, 365.52; PDG/S: H40.13, 365.13; OAG/S (including suspects and ocular hypertension): H40.1, H40.01, H40.02, H40.05, 365.1, 365.01, 365.04, 365.05; ACG/S: H40.2, H40.03, H40.06, 365.2, 365.02, 365.06; SGL: H40.3, H40.4, H40.5, H50.6, 365.3, 365.4, 365.5, 365.6. General or nonspecific glaucoma codes were mapped to Non-GL. For patients with multiple subtype codes, a predefined priority (XFG/S > PDG/S > SGL > ACG/S > OAG/S > Non-GL) was applied to assign a single label, following our prior mapping strategy51. These ICD-derived labels were used only for the ICD-based baselines and for comparison with Ci-SSGAN.

Data preprocessing

To ensure adequate representation for equity-focused analysis, we implemented strategic racial balancing in both labeled and unlabeled datasets. The original institutional dataset exhibited substantial racial imbalance (75% White, 7% Black, 5% Asian, 12% Others/Unknown). For the labeled dataset, we selected notes from underrepresented racial groups at higher rates during the annotation process, yielding 1,182 White notes (40%), 886 Black notes (30%), and 886 Asian notes (30%), compared to the original institutional distribution. This strategic selection during annotation ensured adequate sample sizes for Black and Asian patients, who are disproportionately affected by glaucoma but historically underrepresented in medical datasets. For the unlabeled dataset, we determined the minimum count across the three selected races and sampled equal numbers of notes per racial group (156,566 notes per race = 469,698 total notes), then applied age filtering ( ≥ 30 years), yielding 349,587 notes before augmentation. This balanced sampling approach ensured that demographic vectors used for conditioning the generator and discriminator during training reflected adequate representation of all racial groups rather than the original institutional imbalance. All notes were de-identified using the Philter package to ensure HIPAA compliance52. Text was tokenized with BioClinical BERT2,3, and processed using a sliding window strategy to handle the tokenizer’s 512-token limit. Notes longer than 512 tokens were split into overlapping segments of 512 tokens (with 64-token overlap) to preserve context continuity. Each segment was padded if shorter than 512 tokens and wrapped with [CLS] and [SEP] tokens. Demographics (age, gender, race) were encoded numerically, with age normalized to 0-1 and categorical variables converted to integer representations. Age was normalized using uniform min-max scaling from the observed range [30,90] years to [0, 1]. Gender was binary encoded (Female=0, Male=1), with Unknown/Other categories excluded. Race was encoded numerically (Asian=2, Black or African American=1, White or Caucasian=0), with other racial categories excluded due to insufficient sample sizes as described in the inclusion criteria. During model training, demographic vectors for conditioning the generator and discriminator were sampled directly from patient batches in these balanced datasets, ensuring that synthetic samples reflected adequate representation across all racial groups.

For model training, the labeled dataset was split into 90% for training and validation (1000 patients, 2660 notes) and 10% for a held-out test set (105 patients, 294 notes). Patient-level splits ensured that notes from the same individual did not appear in both training and evaluation sets. Five-fold cross-validation was used within the training partition, with a further 10% of patients in each fold set aside for early stopping.

To increase training diversity and further balance race-gender-age distributions, we implemented a custom rule-based pipeline in Python 3.10 consisting of: (1) section shuffling; (2) synonym substitution using a manually curated dictionary of 17 ophthalmology term sets; (3) bidirectional abbreviation expansion from a 20-term clinical dictionary; (4) measurement format standardization; and additional strategies including modifier variation, neutral statement injection, procedure description variation, and formatting noise. For each note, 2–5 strategies were randomly selected, generating 1–5 variants per note. Augmentation rates were adjusted by race, gender, and age groups to ensure balanced representation across all demographic subgroups, including intersectional combinations, in the final training data fed to the models. Validation and test sets were not augmented to maintain evaluation integrity. After augmentation, the labeled training corpus increased from 2660 to 12825 notes, and the unlabeled partition increased from 349587 to 1399568 notes. Data preprocessing and augmentation steps are illustrated in Fig. 9.

Patient demographics, note types, and clinical note distributions are shown on the left. Processed notes are then de-identified and augmented (token shuffling, synonym substitution, abbreviation expansion, and full spelling), as illustrated on the right. Data augmentation was applied with stratified rates adjusted by race, gender, and age groups to ensure balanced representation across all demographic subgroups in the final training data.

The proposed Ci-SSGAN architecture

We compared Ci-SSGAN against four baselines: Base BERT, BioClinical BERT, and standard SSGAN (Full model architectures in Supplementary Table S3). Both SSGAN and Ci-SSGAN incorporate demographic conditioning in the generator (age, race, gender) and discriminator; the key distinction is Ci-SSGAN’s additional use of unlabeled clinical text embeddings (768-dimensional) in the generator input. This design isolates the contribution of clinical context: both semi-supervised models leverage demographic information, but only Ci-SSGAN additionally incorporates semantic information from unlabeled clinical notes. Base BERT and BioClinical BERT are fully supervised models without adversarial training. Unlike regular SSGANs which only use random noise as input to the generator19,32,33,53,54, Ci-SSGAN introduces a novel architecture where the generator directly learns from unlabeled clinical text. The model comprises three components: (1) a Bio-ClinicalBERT text encoder producing 768-dimensional embeddings from clinical notes; (2) a clinically-informed generator accepting 871-dimensional input, combining 100-dimensional Gaussian noise, 3-dimensional demographics (age, race, gender), and crucially, 768-dimensional unlabeled text embeddings; and (3) a dual-head discriminator with shared feature extraction for both 6-class glaucoma classification and real/fake discrimination. The 100-dimensional noise vector was chosen based on established semi-supervised learning literature19,32,33 and validated through experiments with 200D and 500D alternatives. Monitoring discriminator and generator learning curves (Supplementary Fig. S15) confirmed that 100D noise achieved healthy adversarial balance without mode collapse. While the demographic vector is lower-dimensional (3D) than noise (100D) or text embeddings (768D), its effectiveness is validated through UMAP clustering analysis (Fig. 4) showing clear demographic separation in the learned feature space, and through consistent subgroup performance (Figs. 2 and 3, Supplementary Fig. S3) demonstrating the generator produces demographically appropriate samples.

The discriminator employs dual heads with distinct supervision strategies. The source head performs real/fake discrimination supervised on all samples (\({L}_{{real}}+{L}_{{fake}}\)). The classifier head performs 6-class glaucoma classification supervised exclusively on real labeled samples via focal loss (\({L}_{{supervised}}\)). Generated samples do not require ground truth class labels; the total discriminator loss (\({L}_{{supervised}}+\) \({L}_{{real}}+{L}_{{fake}}\)) applies \({L}_{{supervised}}\) only to real labeled samples, with this component masked for unlabeled and generated samples. During training, demographic vectors are maintained consistently for each sample: when a synthetic sample is generated conditioned on demographics d = (age, race, gender), the same demographic vector d is provided to the discriminator when evaluating that sample, ensuring the discriminator can properly assess whether the generated sample is realistic for that specific demographic profile and enabling fair evaluation across demographic subgroups. This architecture enables the model to learn medical language patterns from large unlabeled clinical notes to improve classification accuracy when labeled data are scarce. Demographic vectors are sampled from the balanced training data (see Data preprocessing), which combined strategic selection of notes from underrepresented racial groups at higher rates during annotation with stratified augmentation across race, gender, and age dimensions. This multi-level balancing strategy enables the generator to learn realistic demographic-disease associations for all subgroups, including intersectional combinations (e.g., young Black females, elderly Asian males), rather than being dominated by majority populations. All BioClinicalBERT parameters were fine-tuned (no freezing was applied), so both the transformer weights and the fully connected layers were updated during training. The generator, discriminator, and text encoder were trained jointly in an adversarial framework using separate optimizers and hyperparameters with a multi-component loss combining supervised focal loss, adversarial loss, feature matching, clinical consistency, and diversity terms to address class imbalance, preserve clinical semantics, and prevent mode collapse. A detailed description of the model learning curves, model architecture, and full list of loss functions are provided in the Figs. S14 and S15 and Tables S4 and S5 in the Supplementary material. An overview of the proposed Ci-SSGAN architecture, including the generator and discriminator components with their inputs, is shown in Fig. 10.

The generator takes as input random noise, demographic features (age, race, gender), and embeddings from unlabeled clinical text, producing synthetic text embeddings to fool the discriminator. The discriminator processes both real and generated embeddings along with demographic features, outputting a real/fake score and class predictions. For each sample, the same demographic vector is passed to both generator and discriminator, ensuring demographic consistency during training. The classifier head receives supervision exclusively from real labeled samples (shown by the label arrow); generated and unlabeled samples contribute only to real/fake discrimination and do not require ground truth class labels. The labels 0-5 refer to: Non-GL, OAG/S, ACG/S, XFG/S, PDG/S, and SGL, respectively. Demographics make the generator demographically conditioned synthesis as it knows how to create appropriate synthetic data for each type of patient. For clarity, only diversity loss is shown. LG is also trained with adversarial, feature matching, and clinical consistency losses. All components, including the BioClinicalBERT encoder and fully connected layers, were fine-tuned. Generator and discriminator were updated alternately using separate optimizers and hyperparameters. Both SSGAN and Ci-SSGAN incorporate demographic conditioning; the key distinction is Ci-SSGAN’s additional use of unlabeled clinical text embeddings (768-dim) in the generator input.

Training protocol

Training was conducted using Python 3.10 and PyTorch 2.3.1 on eight NVIDIA H100 GPUs 80 GB memory each) in a distributed data-parallel setup. Hyperparameters, including learning rates for each model component, were optimized using Optuna55 with 50 trials. The final selected learning rates were \(3\times {10}^{-5}\) for the text encoder, \(1\times {10}^{-4}\) for the discriminator, and \(2\times {10}^{-4}\) for the generator. Models were trained for up to 250 epochs with early stopping (patience = 11), batch size = 16, and gradient clipping at a max norm of 0.5. Underrepresented classes, particularly SGL, were upweighted using dynamically calculated class weights with a 5\(\times\) boost factor. Focal Loss (\(\gamma =2\)) was used to emphasize hard-to-classify cases. The semi-supervised training framework incorporated 349853 unlabeled notes from 155392 patients, utilized in both standard SSGAN and Ci-SSGAN training. Unlabeled embeddings were provided to the generator alongside noise and demographics, enabling clinically relevant synthetic sample generation and enhancing feature diversity. Model comparisons were performed against baseline models (Base BERT and BioClinical BERT) trained with full parameter fine-tuning. Supplementary Table S6 shows the full list of hyperparameters and model configurations.

Performance metrics and statistical analysis

Model performance was evaluated using accuracy, F1 score, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC), and area under the precision–recall curve (AUCPR). These metrics assessed both overall glaucoma detection accuracy and demographic-specific performance across racial, gender, and age subgroups, with analysis conducted at both note and patient levels. Accuracy provides a global measure of correct classifications, while the F1 score balances precision and recall, offering a clinically meaningful view of how well the model detects glaucoma cases without excessive false positives. AUROC measures the model’s ability to discriminate between disease and non-disease across all decision thresholds. AUCPR emphasizes precision in identifying true positive cases. For our 6-class glaucoma classification task, we computed both per-class and overall AUROC/AUCPR metrics using the one-vs-rest (OvR) approach. For each glaucoma subtype, we binarized the problem by treating the target class as positive and all other five classes as negative, then calculated AUROC and AUCPR using the predicted probability for the target class. Overall metrics represent the unweighted mean (macro-average) across all six classes, treating each class equally regardless of sample size. We selected OvR rather than one-vs-one (OvO) because OvR provides clinically interpretable per-class metrics56, as each class is represented by one classifier only, allowing direct inspection of class-specific decision boundaries; OvR is the most commonly used strategy for multiclass classification and represents a computationally efficient default choice; and OvR aligns with clinical decision-making where each subtype must be distinguished from the broader differential diagnosis57, whereas OvO would generate 15 pairwise comparisons that are less interpretable for clinical applications. All AUROC and AUCPR calculations were performed using scikit-learn (version 1.3.0).

We evaluated performance stratified by age groups (30–55, 55–70, >=70 years), gender (female, male), and race (Asian, Black, White). To quantify model’s bias across demographics, we introduce a new PV score that simultaneously evaluates over-diagnosis and under-diagnosis disparities across demographic Categories (C) using PPV and NPV. This metric bridges model’s fairness with clinical practice by measuring disparities in both false positive and false negative prediction rates and is formulated as:

\({PV\; score}=\,{\max }_{i,j}\left|C{(g}_{i})-C{(g}_{j})\right|\), Where \(C{(g}_{i})=\frac{2\times ({PPV}{(g}_{i})\times {NPV}{(g}_{i}))}{{PPV}{(g}_{i})+{NPV}{(g}_{i})}\)

Here, \({{g}}_{i}\) and \({g}_{j}\) are individual groups within that category. This formulation bridges fairness with clinical practice by penalizing disparities in both false-positive and false-negative rates. Prediction uncertainty for each sample was determined using Tsallis entropy58, computed as

where \({P}_{i}\) is the predicted probability of class \(i\). Given the class imbalance in glaucoma subtype classification, we set the entropic parameter to \(q\) = 0.25, which emphasizes uncertainty in rare classes and provides greater sensitivity to predictions involving underrepresented glaucoma types59.

All tests were two-sided with significance set at P < 0.05. Model performance was compared across metrics, data fractions, and demographic subgroups. Pairwise differences (accuracy, F1, AUROC, AUCPR, PV score) were assessed using paired t-tests across five cross-validation folds. Subgroup analyses (race, gender, age) used ANOVA with post-hoc t-tests. Multiple comparisons were adjusted with Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) correction, and adjusted P < 0.05 was considered significant. Analyses were performed in Python 3.10 using SciPy (v1.13) and statsmodels (v0.14).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The codes for the proposed model are available at https://github.com/Mousamoradi/Ci-SSGAN.

References

Koroteev, M. V. BERT: a review of applications in natural language processing and understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:2103.11943 (2021).

Lee, J. et al. BioBERT: a pre-trained biomedical language representation model for biomedical text mining. Bioinformatics 36, 1234–1240 (2020).

Alsentzer, E. et al. Publicly available clinical BERT embeddings. Proceedings of the 2nd Clinical Natural Language Processing Workshop 72–78 (2019).

Singhal, K. et al. Toward expert-level medical question answering with large language models. Nat. Med. 31, 943–950 (2025).

Singhal, K. et al. Large language models encode clinical knowledge. Nature 620, 172–180 (2023).

Sellergren, A. et al. Medgemma technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2507.05201 (2025).

Wang, S., Hu, M., Li, Q., Safari, M. & Yang, X. Capabilities of GPT-5 on Multimodal Medical Reasoning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2508.08224 (2025).

Achiam, J. et al. Gpt-4 technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.08774 (2023).

Patel, S. B. & Lam, K. ChatGPT: the future of discharge summaries?. Lancet Digit. Health 5, e107–e108 (2023).

Ali, S. R., Dobbs, T. D., Hutchings, H. A. & Whitaker, I. S. Using ChatGPT to write patient clinic letters. Lancet Digit. Health 5, e179–e181 (2023).

Guo, Y. et al. The curious decline of linguistic diversity: Training language models on synthetic text. Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: NAACL 2024, 3589–3604 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Clinical information extraction applications: a literature review. J. Biomed. Inform. 77, 34–49 (2018).

Moradi, M. et al. PyGlaucoMetrics: a stacked weight-based machine learning approach for glaucoma detection using visual field data. Medicina 61, 541 (2025).

Shah, R. et al. OphthaBERT: Automated Glaucoma Diagnosis from Clinical Notes. medRxiv, 2025.2006. 2008.25329151 (2025).

Hekler, A. et al. Effects of label noise on deep learning-based skin cancer classification. Front. Med. 7, 177 (2020).

Karimi, D., Dou, H., Warfield, S. K. & Gholipour, A. Deep learning with noisy labels: exploring techniques and remedies in medical image analysis. Med. Image Anal. 65, 101759 (2020).

Agro, M. T. & Aldarmaki, H. Handling realistic label noise in BERT text classification. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.16337 (2023).

Chen, H. et al. On the diversity of synthetic data and its impact on training large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.15226 (2024).

Salimans, T. et al. Improved techniques for training gans. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 29, 2226–2234 (2016).

Hwang, D. Y., Nechaev, Y., de Lichy, C. & Zhang, R. G. A. N.-L. M.: Generative adversarial network using language models for downstream applications. Proceedings of the 16th International Natural Language Generation Conference, 69–79 (2023).

Tran, J. H. et al. Use of diagnostic codes for primary open-angle glaucoma polygenic risk score construction in electronic health record–linked biobanks. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 267, 204–212 (2024).

Liebman, D. L. et al. Accuracy of ICD-10 glaucoma codes in a large academic practice. Ophthalmol. Glaucoma 8, 643–645 (2025).

Halawa, O. A. et al. Race and ethnicity differences in disease severity and visual field progression among glaucoma patients. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 242, 69–76 (2022).

Halawa, O. A. et al. Racial and socioeconomic differences in eye care utilization among Medicare beneficiaries with glaucoma. Ophthalmology 129, 397–405 (2022).

Racette, L., Wilson, M. R., Zangwill, L. M., Weinreb, R. N. & Sample, P. A. Primary open-angle glaucoma in blacks: a review. Surv. Ophthalmol. 48, 295–313 (2003).

Tehrani, S. Gender difference in the pathophysiology and treatment of glaucoma. Curr. Eye Res. 40, 191–200 (2015).

Qiu, Y. et al. Association between sex hormones and visual field progression in women with primary open angle glaucoma: a cross-sectional and prospective cohort study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 13, 756186 (2021).

Zhang, N., Wang, J., Chen, B., Li, Y. & Jiang, B. Prevalence of primary angle closure glaucoma in the last 20 years: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Front. Med. 7, 624179 (2021).

Lee, J. et al. Rate of progression among different age groups in glaucoma with high myopia: a 10-year follow-up cohort study. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 276, 201–209 (2025).

Lee, E. J. et al. Different glaucoma progression rates by age groups in young myopic glaucoma patients. Sci. Rep. 14, 2589 (2024).

Dubey, A. et al. The llama 3 herd of models. arXiv e-prints, arXiv: 2407.21783 (2024).

Odena, A. Semi-supervised learning with generative adversarial networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1606.01583 (2016).

Pasupa, K., Tungjitnob, S. & Vatathanavaro, S. Semi-supervised learning with deep convolutional generative adversarial networks for canine red blood cells morphology classification. Multimed. Tools Appl. 79, 34209–34226 (2020).

Issarti, I. & Rozema, J. J. in Artificial Intelligence in Ophthalmology 19–36 (Springer, 2025).

Srivastava, A., Valkov, L., Russell, C., Gutmann, M. U. & Sutton, C. Veegan: reducing mode collapse in gans using implicit variational learning. Adv. Neural Inform. Process. Syst. 30, 3310–3320 (2017).

Xu, D., Yuan, S., Zhang, L. & Wu, X. in 2018 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data). 570–575 (IEEE).

Ting, D. S. W. et al. Development and validation of a deep learning system for diabetic retinopathy and related eye diseases using retinal images from multiethnic populations with diabetes. Jama 318, 2211–2223 (2017).

Vij, R. & Arora, S. A systematic review on diabetic retinopathy detection using deep learning techniques. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 30, 2211–2256 (2023).

Bora, A. et al. Predicting the risk of developing diabetic retinopathy using deep learning. Lancet Digit. Health 3, e10–e19 (2021).

Moradi, M., Chen, Y., Du, X. & Seddon, J. M. Deep ensemble learning for automated non-advanced AMD classification using optimized retinal layer segmentation and SD-OCT scans. Comput. Biol. Med. 154, 106512 (2023).

Moradi, M., Huan, T., Chen, Y., Du, X. & Seddon, J. Ensemble learning for AMD prediction using retina OCT scans. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 63, 732–F0460–0732–F0460 (2022).

Moradi, M. Computational Modeling and Machine Learning Methods for Advancing Healthcare: Medical Image Analysis and Model Validation in Kidney Assessment, AMD Detection, and Pulse Oximetry. PhD thesis, University of Massachusetts Amherst (2024).

Attia, Z. I. et al. Screening for cardiac contractile dysfunction using an artificial intelligence–enabled electrocardiogram. Nat. Med. 25, 70–74 (2019).

Johnson, K. W. et al. Artificial intelligence in cardiology. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 71, 2668–2679 (2018).

Krittanawong, C. et al. Deep learning for cardiovascular medicine: a practical primer. Eur. Heart J. 40, 2058–2073 (2019).

Shatte, A. B., Hutchinson, D. M. & Teague, S. J. Machine learning in mental health: a scoping review of methods and applications. Psychol. Med. 49, 1426–1448 (2019).

Graham, S. et al. Artificial intelligence for mental health and mental illnesses: an overview. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 21, 116 (2019).

Vedanta, S. & Rao, M. in 2024 9th International Conference on Computer Science and Engineering (UBMK). 1–6 (IEEE).

Moradi, M. et al. Deep feature fusion for detecting glaucoma progression using hybrid model of structural and functional data. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 66, PP007–PP007 (2025).

Stein, J. D. et al. Evaluation of an algorithm for identifying ocular conditions in electronic health record data. JAMA Ophthalmol. 137, 491–497 (2019).

Fujita, A. et al. Treatment patterns of childhood glaucoma in the United States: Analysis of IRISⓇ Registry (Intelligent Research in Sight). Am. J. Ophthalmol. 271, 210–221 (2025).

Norgeot, B. et al. Protected Health Information filter (Philter): accurately and securely de-identifying free-text clinical notes. NPJ Digit. Med. 3, 57 (2020).

Sricharan, K. et al. Semi-supervised conditional gans. arXiv preprint arXiv:1708.05789 (2017).

Dai, Z., Yang, Z., Yang, F., Cohen, W. W. & Salakhutdinov, R. R. Good semi-supervised learning that requires a bad GAN. Adv. Neural Inform. Process. Syst. 30, 6510–6520 (2017).

Takuya Akiba, S. S. et al. Optuna: a next-generation hyperparameter optimization framework. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, 2623–2631 (2019).

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830 (2011).

Rifkin, R. & Klautau, A. In defense of one-vs-all classification. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 5, 101–141 (2004).

Tsallis, C. Possible generalization of Boltzmann-Gibbs statistics. J. Stat. Phys. 52, 479–487 (1988).

Abe, S. Axioms and uniqueness theorem for Tsallis entropy. Phys. Lett. A 271, 74–79 (2000).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH: R01 EY036222 and R21 EY035298), and MIT-MGB AI Cures Grant. We thank Mass General Brigham's AI Zone team for providing secure, HIPAA-compliant access to GPT-4o through the Azure AI Foundry platform.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.M. conceived the study and contributed to conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, software, validation, data preparation and cleaning, writing (original draft, review and editing), and visualization. R.S. contributed to validation, data preparation and cleaning, review and editing, and visualization. A.F. performed data preparation, clinical grading, and review and editing. N.B. contributed to clinical grading and review and editing. D.M.V. contributed to clinical grading and review and editing. K.A. and D.L.L. performed clinical grading. S.K.H. contributed to methodology. M.W. and T.E. provided resources and funding. M.E. contributed to validation, review and editing, project administration, and visualization. N.Z. contributed to clinical grading, review and editing, resources, project administration, and funding. N.Z. and M.E. contributed equally. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Moradi, M., Shah, R., Fujita, A. et al. Clinically informed semi-supervised learning improves disease annotation and equity from electronic health records: a glaucoma case study. npj Digit. Med. 9, 82 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02267-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02267-w