Abstract

Early and accessible detection of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) remains a major clinical challenge. We developed a machine learning–based blood transcriptomic model, the Lactylation-Derived Score (LDS), from lactylation-related genes across nine AD cohorts, using a standardized pipeline with z-score normalization, random forest–based feature screening, plsRglm modeling, and 10-fold cross-validation. LDS was externally tested in seven independent brain transcriptomic datasets and clinically validated in an independent plasma cohort (n = 540); logistic regression was used to integrate LDS with plasma phosphorylated tau 181 (p-tau181) and p-tau217. LDS achieved an AUC of 0.897 (95% CI 0.849–0.934) in the Training Cohort and 0.772 (95% CI 0.729–0.815) in the plasma validation cohort, while the three-marker model (LDS + p-tau181 + p-tau217) yielded the highest diagnostic performance (AUC 0.859, 95% CI 0.824–0.893). LDS alone effectively identified AT⁺ individuals (AUC 0.861, 95% CI 0.827–0.897), and a five-gene classifier derived from LDS genes stratified amnestic mild cognitive impairment with an AUC of 0.809 (95% CI 0.714–0.836). LDS-high individuals showed neuroinflammatory activation and metabolic stress signatures, indicating that this scalable, interpretable transcriptomic model complements plasma p-tau biomarkers and supports precision digital medicine in AD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a chronic and progressive neurodegenerative disorder and the leading cause of dementia in the elderly population1,2. Clinically, AD manifests as gradual cognitive decline, behavioral changes, and loss of independence, profoundly affecting patients’ quality of life and creating a major burden for caregivers and healthcare systems3,4. With the rapid global population aging, its incidence and prevalence continue to rise, posing a pressing public health challenge1,5. Despite advances in elucidating its core pathological hallmarks—including amyloid-β (Aβ) deposition, tau hyperphosphorylation, synaptic dysfunction, and neuroinflammation—early identification of individuals at risk remains an unmet clinical need6,7,8. In high-risk or prodromal conditions, such as amnestic mild cognitive impairment (aMCI), which confers an elevated risk of AD conversion but is not synonymous with early AD, symptoms are often subtle and may escape detection by conventional cognitive tests or neuroimaging9,10. Although cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers offer diagnostic value, their invasiveness and cost limit their use in large-scale population screening11. These limitations underscore the need for non-invasive, biologically informative biomarkers to support early risk stratification and clinical decision-making in AD.

Recent research has underscored the value of blood-based biomarkers such as plasma phosphorylated tau 181 (p-tau181), phosphorylated tau 217 (p-tau217), neurofilament light chain (NfL), and Aβ42/40 in AD diagnosis and progression monitoring. However, most of these biomarkers are centered around classical AD hallmarks and may not capture the full spectrum of molecular disruptions, including metabolic or epigenetic alterations12,13. Thus, exploring novel molecular mechanisms and peripheral indicators beyond the Aβ-tau axis is vital to advance early detection.

Lactate, traditionally regarded as a glycolytic byproduct, is now recognized as a key metabolic regulator with signaling functions in immune response, energy metabolism, and cellular adaptation14,15,16. Lactylation, a recently discovered post-translational modification, represents a direct molecular link between glycolysis and epigenetic gene regulation17,18,19,20. Dysregulated lactylation has been implicated in cancer, infection, and several neurological conditions, yet its role in AD remains largely unexplored.

In this study, we developed a Lactylation-Derived Score (LDS) to translate lactylation-related molecular signatures into a non-invasive, clinically actionable biomarker framework for AD. Using a two-stage machine-learning pipeline on multi-cohort brain transcriptomic data, we derived a seven-gene LDS model with high and stable diagnostic performance, which was further validated in an independent clinical plasma cohort. LDS scores correlated with Braak stage and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), showed a stepwise increase from normal controls (NC) to aMCI and AD, and, when combined with plasma p-tau181 and p-tau217 via logistic regression, improved detection of AD and amyloid-tau positive (AT⁺) individuals. Collectively, LDS represents a mechanistically informed, interpretable blood-based tool with translational potential for early detection and patient stratification in AD. An overview of the study design is presented in Fig. 1.

Panel I: Two GEO brain transcriptomic datasets (GSE5281 and GSE84422; 102 NC and 121 AD samples) were integrated as the Training Cohort, processed by log2 transformation, quantile normalization, and ComBat batch correction, and 32 differentially expressed lactylation-related genes (DE-LRGs) were identified. Panel II: Using multiple feature-selection and machine-learning algorithms, 113 candidate models were screened and an RF + plsRglm LDS model based on seven key genes (GFAP, GTF2I, RB1, PFKM, BCLAF1, SPR, SMARCC1) was established. Panel III: LDS was validated and benchmarked against published signatures and single genes in seven independent GEO cohorts, demonstrating robust cross-platform diagnostic performance. Panel IV: In an independent clinical plasma cohort (NC = 180, aMCI = 90, AD = 270; total n = 540), the seven LDS genes (RT-qPCR) and p-tau181/217 (Simoa) were measured to evaluate diagnostic performance for AD and aMCI, identify AT⁺ individuals, and explore clinical utility and potential therapeutic targets. This figure was created with BioRender.com and is used under a permitted license.

Results

Transcriptomic profiling reveals chromatin- and mitochondria-related lactylation alterations in AD

To identify lactylation-related genes with potential regulatory roles in AD, we integrated transcriptomic data from the GSE5281 and GSE84422 datasets and constructed a unified Training Cohort after batch effect correction (Supplementary Fig. 1). Based on this combined dataset, differential expression analysis revealed 163 lactylation-related genes that were significantly dysregulated between AD and NC groups (P < 0.05, Supplementary Fig. 2A). Functional enrichment analysis using KEGG and GO showed that the upregulated genes were primarily involved in ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling, spliceosome assembly, and epigenetic transcriptional regulation (Supplementary Fig. 2B–C), suggesting a strong association with chromatin structure remodeling in neurons. In contrast, downregulated genes were significantly enriched in pathways related to AD pathogenesis, mitochondrial respiratory chain activity, and protein processing in the endoplasmic reticulum. Corresponding GO terms highlighted “mitochondrial structure” and “synaptic function” (Supplementary Fig. 2D–E). These findings indicate that lactylation dysregulation in AD may be subtype-specific and mechanistically linked to both epigenetic alterations and metabolic disturbances in neurons, potentially contributing to disease onset and progression.

Lactylation-based subtyping reveals metabolic–immune divergence in AD patients

To investigate the potential heterogeneity of lactylation modification in AD patients, consensus clustering was performed on the Training Cohort based on lactylation scores. Evaluation of the CDF curve and delta area plot indicated that K = 2 was the optimal clustering solution (Fig. 2A–C). The resulting subtypes were designated Cluster 1 and Cluster 2, with Cluster 1 showing significantly higher lactylation scores than Cluster 2 (Fig. 2D).

A–C CDF curve, delta area plot, and PAC score identifying optimal cluster number (k = 2). D Comparison of lactylation scores between Clust 1 and Clust 2. E GO and KEGG enrichment of upregulated genes in Clust 1. F GSVA analysis showing pathway activation differences between subtypes. G, H Immune cell infiltration scores via MCP-counter and xCell algorithms. I Differential expression of immune checkpoint genes. Subtype comparisons were performed using two-sided Kruskal–Wallis tests followed by Benjamini–Hochberg FDR correction. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Differential gene expression and enrichment analyses revealed that upregulated genes in Cluster 1 were significantly enriched in pathways related to oxidative phosphorylation, mitochondrial electron transport, and ATP metabolism. KEGG analysis also showed strong enrichment in neurodegenerative disease–related pathways, including “Alzheimer’s disease” and “Parkinson’s disease” (Fig. 2E, Supplementary Fig. 3A). GSVA further demonstrated that Cluster 1 exhibited enhanced activity in pathways related to neuronal metabolism and synaptic function, indicating a more metabolically active profile (Fig. 2F).

In contrast, immune profiling based on multiple algorithms (MCP-counter, xCell, quanTIseq, and IPS) revealed that Cluster 2 displayed higher levels of immune cell infiltration and immune activation scores, including significant upregulation of Tregs, plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs), and neutrophils (Fig. 2G, H). Moreover, immune checkpoint genes such as CTLA4, PDCD1, TNFRSF8, TNFRSF9, TNFRSF14, TNFSF14, and PVR were significantly overexpressed in Cluster 2 (Fig. 2I). Despite lower lactylation levels, Cluster 2 exhibited stronger immune activation, suggesting that the relationship between lactylation status and immune phenotype may be modulated by additional signaling pathways or regulatory factors.

Further analysis revealed distinct expression patterns between the two subtypes across various immune-related gene categories, including chemokines, immunostimulatory molecules, MHC genes, and immune receptors, supporting the immunological divergence of the two lactylation-defined AD subtypes (Supplementary Fig. 3B-E).

Development and validation of the LDS model for AD diagnosis

Based on the previously defined LDS model constructed from 113 candidate machine-learning pipelines, we next evaluated its diagnostic performance across multiple cohorts. In the Training Cohort, LDS achieved an AUC of 0.897 (95% CI: 0.849–0.934), with a sensitivity of 83.5% (95% CI: 75.8–89.0%), specificity of 80.4% (95% CI: 71.6–86.9%), and overall accuracy of 82.1% (95% CI: 76.5–86.5%) (Fig. 3A and Table 1). Consistently, internal validation using bootstrap resampling (1000 iterations) in the Training Cohort yielded highly similar AUC estimates, confirming the stability of the discriminative performance of the LDS model. Across the seven independent external validation datasets, LDS consistently yielded AUCs greater than 0.72, with a maximum AUC of 0.906 (95% CI: 0.719–1.000) and an average AUC of 0.822, indicating robust cross-platform generalization (Fig. 3A, B, Table 1). Seven key lactylation-related genes—GFAP, GTF2I, RB1, PFKM, BCLAF1, SPR, and SMARCC1—were selected based on VIMP > 0 scores from the initial RF model and incorporated into the final LDS model. In the Training Cohort, six of these genes—except PFKM—were significantly upregulated in AD (Supplementary Fig. 4A and Supplementary Table 1), and co-expression analysis showed strong positive correlations between GFAP and GTF2I/SMARCC1, with a negative correlation between GFAP and PFKM (Supplementary Fig. 4C). Single-gene ROC analysis identified GFAP as the best individual marker, with an AUC of 0.820 (95% CI: 0.765–0.875), whereas the composite LDS model consistently outperformed all single genes (Fig. 3C and Supplementary Table 1). Moreover, GFAP, SPR, and SMARCC1 were overexpressed and PFKM was downregulated across the seven external datasets, and GFAP maintained strong diagnostic performance in multiple cohorts (Supplementary Fig. 4D–J). Beyond discrimination, DCA in the Training Cohort showed that LDS provided higher standardized net benefit than the “treat-all” or “treat-none” strategies over a wide range of thresholds (Fig. 3D), with similar DCA profiles in the external GEO cohorts and the independent clinical plasma cohort (Supplementary Fig. 4K). Calibration curves in the Training and validation datasets further demonstrated good agreement between predicted and observed AD probabilities (Supplementary Fig. 4B, L). Collectively, these findings indicate that the LDS model, derived from lactylation-related molecular features, provides high diagnostic accuracy with well-quantified uncertainty, good calibration, and stable performance across multicenter and multi-platform datasets, supporting its potential for clinical translation.

A Heatmap showing AUC values of the LDS model, eight published transcriptomic signatures, and the seven individual LDS genes across the Training Cohort and seven external GEO cohorts; colors indicate AUC magnitude. B ROC curves and confusion matrices of the optimal “RF+plsRglm” model across the 8 validation cohorts. C ROC curves of the seven individual LDS genes (GFAP, GTF2I, RB1, PFKM, BCLAF1, SPR, and SMARCC1) for distinguishing AD from NC in the Training Cohort (n = 121 AD and n = 102 NC). D Decision curve analysis of the LDS model in the Training Cohort, showing standardized net benefit across a range of risk thresholds compared with “treat-all” and “treat-none” strategies. All AUCs were derived from ROC analyses with 95% CI; where applicable, differences between AUCs were assessed using two-sided DeLong tests.

SHAP-based interpretation and cross-cohort stability of the LDS model

To interpret how each gene contributed to the LDS classifier, we applied SHAP to the final RF + plsRglm model. In the Training Cohort, SHAP summary plots showed that higher expression of GFAP, RB1, PFKM, BCLAF1, SMARCC1, SPR, and GTF2I generally increased the predicted LDS risk score, with GFAP exerting the largest impact on the model output (Fig. 4A). Ranking genes by mean absolute SHAP values confirmed GFAP as the most influential feature, followed by RB1, PFKM, BCLAF1, SMARCC1, SPR, and GTF2I (Fig. 4B).

We next evaluated the stability of gene contributions across datasets. SHAP importance profiles derived from the LDS model in the Training Cohort, seven external GEO cohorts, and the independent clinical plasma cohort were highly correlated, indicating consistent patterns of feature importance (Supplementary Fig. 5A). In each cohort, GFAP remained the top contributor, whereas BCLAF1, SMARCC1, SPR, RB1, and GTF2I showed similar relative rankings (Supplementary Fig. 5B), supporting the robustness and biological plausibility of the LDS gene set across platforms and populations.

Independent plasma validation confirms clinical robustness and superiority of the LDS model

To further evaluate the clinical applicability of LDS, we established an independent clinical plasma cohort comprising 270 AD patients and 180 age-matched NC participants. Plasma expression of the seven LDS genes was quantified by RT-qPCR; six genes (all except PFKM) were significantly upregulated in AD, consistent with the Training Cohort (Fig. 5A). In single-gene analyses, BCLAF1 showed the best performance with an AUC of 0.742 (95% CI: 0.697–0.788), followed by GFAP (0.731, 95% CI: 0.685–0.777), whereas PFKM performed worst (0.540, 95% CI: 0.487–0.593) (Fig. 5B and Supplementary Table 2). When these genes were integrated into the LDS panel, the model achieved an AUC of 0.772 (95% CI: 0.729–0.815), with a sensitivity of 48.1% (95% CI: 42.3–54.1%), specificity of 96.7% (95% CI: 92.9–98.5%), and overall accuracy of 67.6% (95% CI: 63.1–71.7%) in the plasma cohort (Fig. 5C, Table 1), indicating strong discriminative ability and excellent rule-out capacity for AD.

A Plasma expression of the seven LDS genes in NC and AD groups in the independent clinical cohort (n = 180 NC, n = 270 AD). B ROC curves of each LDS gene for discriminating AD from NC in the same cohort. C ROC curve and confusion matrix of the LDS model for AD vs NC in the plasma cohort. D Comparison of AUCs (with 95% CI) for the LDS model, eight published gene signatures, and single LDS genes across the Training Cohort and seven external GEO cohorts. Group comparisons were performed using the Mann–Whitney U test, and ROC-based performance metrics were compared using the DeLong method. ***P < 0.001.

For benchmarking, we compared LDS with eight published AD-related multi-gene signatures (oxidative stress, cuproptosis, metabolic, mitochondrial, T-cell receptor (TCR) signaling, m7G methylation, ICD, and chromatin-related models) and calculated AUCs with 95% CIs in all eight public datasets. LDS ranked within the top or upper-middle range in six of eight datasets and yielded the highest AUCs in the Training Cohort, GSE132903, and GSE29378 (Fig. 5D). Pairwise DeLong tests with Benjamini–Hochberg FDR correction showed that LDS significantly outperformed at least five of the eight literature models in multiple datasets (P < 0.05; Fig. 5D, Supplementary Data 1). These data further support the stability, generalizability, and translational potential of LDS for blood-based AD diagnosis.

LDS improves diagnostic performance and complements p-tau biomarkers for detecting AD and AT+ individuals

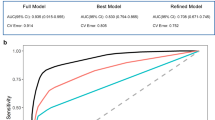

To assess whether the LDS model provides additional diagnostic value beyond established phosphorylated tau biomarkers, we compared LDS with plasma p-tau181 and p-tau217 in the independent clinical plasma cohort. As expected, both p-tau181 and p-tau217 were significantly higher in AD than in NC (Fig. 6A). LDS scores correlated positively with p-tau181 (r = 0.320, P < 0.0001) and p-tau217 (r = 0.253, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 6B, C, Supplementary Fig. 6A). In single-marker ROC analyses, p-tau181 and p-tau217 achieved AUCs of 0.828 (95% CI: 0.788–0.864) and 0.843 (95% CI: 0.806–0.878), with sensitivities of 59.6% (95% CI: 53.7–65.3%) and 73.7% (95% CI: 68.1–78.6%) and specificities of 98.9% (95% CI: 96.0–99.7%) and 85.6% (95% CI: 79.7–89.9%), respectively (Fig. 6D–F, Table 2). Logistic regression models combining LDS with p-tau181 and/or p-tau217 further improved discrimination; the three-marker model (LDS + p-tau181 + p-tau217) yielded an AUC of 0.859 (95% CI: 0.824–0.893), sensitivity of 70.4% (95% CI: 65.4–76.2%), specificity of 98.9% (95% CI: 94.4–99.1%), and overall accuracy of 81.8% (95% CI: 77.9–85.1%) (Fig. 6G, Table 2). DeLong tests with Benjamini–Hochberg correction confirmed that LDS-based combinations outperformed LDS alone (P < 0.05; Table 2), and DCA showed higher standardized net benefit for combined models than for LDS or either p-tau marker alone (Supplementary Fig. 6B). To assess LDS for detecting tau pathology, we stratified participants into AT⁺ and AT⁻ subgroups; LDS distinguished AT⁺ from AT⁻ individuals with an AUC of 0.861 (95% CI: 0.827–0.892), sensitivity of 71.1% (95% CI: 65.1–76.4%), specificity of 89.9% (95% CI: 85.1–93.3%), and accuracy of 79.8% (95% CI: 75.8–83.2%) (Fig. 6H, Table 2). These findings indicate that LDS complements plasma p-tau181 and p-tau217 and can non-invasively identify individuals with underlying tau pathology (AT⁺).

A Plasma expression levels of p-tau181 and p-tau217 in AD vs NC groups (n = 180 NC, n = 270 AD). Correlation between LDS scores and p-tau181 (B) or p-tau217 (C) in the Independent clinical plasma cohort. D ROC curves of LDS, p-tau181, and p-tau217 for discriminating against AD from NC. Confusion matrices showing classification performance of p-tau181 (E) and p-tau217 (F). G ROC curves of combined models integrating LDS with p-tau biomarkers for AD vs NC. H ROC curve of LDS for stratifying AT+ vs AT– individuals, indicating its potential for detecting tau pathology. Statistical analyses included Mann–Whitney U testing for expression, Spearman correlation for association analysis, and DeLong testing for ROC comparison. ***P < 0.001.

LDS score reflects population heterogeneity and correlates with neuropathological and functional severity

To evaluate LDS performance in different subgroups, we performed age- and sex-stratified ROC analyses in both the Training Cohort and the independent clinical plasma cohort. In the Training Cohort, LDS showed higher discrimination in participants aged ≤ 70 years than in those > 70 years (AUC = 0.960, 95% CI: 0.850–1.000 vs 0.893, 95% CI: 0.846–0.935) and in males than in females (AUC = 0.937, 95% CI: 0.900–0.966 vs 0.787, 95% CI: 0.632–0.914) (Fig. 7A, B). In the independent clinical plasma cohort, performance was better in the > 70 years subgroup than in those ≤ 70 years (AUC = 0.794, 95% CI: 0.746–0.836 vs 0.566, 95% CI: 0.408–0.721), while the sex-related pattern was similar (male AUC = 0.838, 95% CI: 0.783–0.890; female AUC = 0.708, 95% CI: 0.642–0.776) (Fig. 7C, D), indicating demographic influences on LDS accuracy.

A, B ROC curves of the LDS model in the Training Cohort stratified by age (< 70 vs ≥ 70 years) and sex (female vs male). C, D ROC curves of the LDS model in the independent clinical plasma cohort stratified by age and sex. E Spearman correlations between LDS risk score and Braak stage, MMSE, NFT density (NFTD), and plaque load in Training cohort. F Spearman correlations between LDS risk score and ADL, age, FRAIL, MMSE, PSQI, and SDS scores in the clinical plasma cohort. Associations were assessed using Spearman correlation, and subgroup ROC comparisons were analyzed using the DeLong test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

We then examined correlations between LDS risk scores and clinical measures. In the Training Cohort, LDS correlated positively with Braak stage (r = 0.49), neurofibrillary tangle density (r = 0.52), and plaque burden (r = 0.43), and negatively with MMSE score (r = −0.27) (Fig. 7E). In the independent clinical plasma cohort, LDS was associated with age (r = 0.35), FRAIL score (r = 0.17), MMSE score (r = −0.44), ADL (r = 0.27), PSQI (r = 0.26), and SDS (r = 0.14) (Fig. 7F). Together, these results show that LDS reflects demographic and disease-related heterogeneity and is linked to neuropathological and functional severity.

LDS high-risk group exhibits neuroinflammation and metabolic dysfunction

To explore mechanisms underlying the LDS model, we stratified samples into high- and low-risk groups according to LDS scores and performed differential expression and enrichment analyses. GO analysis showed that genes upregulated in the high-risk group were mainly involved in cellular and tissue development, glial differentiation, and wound healing, with molecular functions enriched in cytokine binding and extracellular matrix organization, consistent with immune activation (Supplementary Fig. 7A–C). Hallmark pathway analysis further indicated increased TNFα signaling via NF-κB, IL6–JAK–STAT3 signaling, complement activation, and interferon responses, accompanied by reduced oxidative phosphorylation, DNA repair, and unfolded protein response pathways (Supplementary Fig. 7D). LDS scores were positively correlated with immune and inflammatory pathways and negatively correlated with metabolism-related protective pathways (Supplementary Fig. 7E).

Immune profiling by ssGSEA and xCell revealed greater infiltration of immunosuppressive and pro-inflammatory cells (Tregs, pDCs, neutrophils) in the high-risk group, whereas low-risk individuals were enriched for neuroprotective immune populations such as activated dendritic cells and CD8⁺ T cells (Supplementary Fig. 7F, left). Immune function scores were also higher in the high-risk group for antigen-presentation inhibition, immune checkpoints, inflammation-promoting activity, and type I/II interferon responses (Supplementary Fig. 7F, right), and radar plots highlighted clearly separated immune signatures between the two risk groups (Supplementary Fig. 7G–H). Together, these data indicate that LDS high-risk individuals are characterized by immune activation, neuroinflammation, and metabolic dysfunction, whereas the low-risk group maintains a more stable neuroimmune state, supporting the mechanistic interpretability of the LDS model and suggesting potential therapeutic targets.

Risk stratification of aMCI individuals using lactylation-related signatures and plasma tau biomarkers

aMCI is widely considered a transitional state with high risk of conversion to AD. To assess whether lactylation-related alterations emerge at this prodromal stage, we analyzed plasma samples from 90 aMCI patients and 180 NC participants. The LDS risk score and plasma p-tau181 and p-tau217 levels were all significantly higher in aMCI than in NC (Fig. 8A). Correlation analysis showed moderate positive associations among LDS, p-tau181, p-tau217, and the five LDS genes (Supplementary Fig. 8A). For aMCI identification, ROC analysis revealed that p-tau217 achieved the highest AUC of 0.838 (95% CI: 0.786–0.886), followed by LDS with an AUC of 0.750 (95% CI: 0.678–0.813) and p-tau181 with an AUC of 0.694 (95% CI: 0.617–0.768) (Supplementary Fig. 8B, Table 3). Logistic regression models combining LDS with p-tau biomarkers further improved discrimination; LDS + p-tau181 and LDS + p-tau217 yielded AUCs of 0.802 (95% CI: 0.742–0.861) and 0.896 (95% CI: 0.856–0.935), respectively, and the three-marker model (LDS + p-tau181 + p-tau217) reached an AUC of 0.912 (95% CI: 0.872–0.947) (Fig. 8B, Table 3).

A Plasma LDS score, p-tau181, and p-tau217 levels in NC and aMCI groups in the independent clinical cohort (n = 180 NC, n = 90 aMCI). B ROC curves of LDS and its combinations with p-tau181/217 for distinguishing aMCI from NC in the same cohort. C Plasma expression of the five selected LDS genes (GFAP, GTF2I, BCLAF1, SPR, SMARCC1) in NC and aMCI groups. D ROC curves of four machine-learning models (logistic regression, RF, SVM, LASSO) based on the five genes for aMCI vs NC. E ROC curve of the combined model integrating RF classifier with p-tau181 and p-tau217 for aMCI vs NC. F ROC curve of the RF model for identifying AT⁺ vs AT⁻ individuals in the plasma cohort. Group comparisons were performed using the Mann–Whitney U test and ROC metrics were compared using the DeLong statistical method. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

To enhance prediction using LDS-related genes, we examined expression of the seven LDS genes and identified five (GFAP, GTF2I, BCLAF1, SPR, SMARCC1) that were significantly upregulated in aMCI (Fig. 8C). These genes were used to build aMCI classifiers with four machine-learning algorithms. The RF model showed the best performance, with an AUC of 0.809 (95% CI: 0.714–0.836), sensitivity of 90.9%, specificity of 57.2%, and overall accuracy of 79.3% (Fig. 8D, Supplementary Table 3). Variable importance analysis highlighted GFAP and BCLAF1 as the major contributors (Supplementary Fig. 8C). Integrating the RF-derived gene score with p-tau181 and p-tau217 further increased accuracy, yielding an AUC of 0.915 (95% CI: 0.887–0.927), with sensitivity of 90.3%, specificity of 75.9%, and accuracy of 85.2% (Fig. 8E, Supplementary Table 3). When participants were stratified into AT⁺ and AT⁻ groups, this RF-based model almost perfectly distinguished AT⁺ individuals, achieving an AUC of 0.999 (95% CI: 0.984–1.000), sensitivity of 99.4%, specificity of 100%, and accuracy of 99.6% (Fig. 8F, Supplementary Table 3), underscoring its potential for early identification of individuals with underlying tau pathology.

Drug enrichment analysis reveals potential therapeutic targets for lactylation-related genes in AD

To explore potential therapeutic strategies targeting key lactylation-related genes, we performed drug enrichment analysis using the DSigDB module on the Enrichr platform. Based on a significance threshold of P < 0.05, several small-molecule compounds were identified as candidates that may modulate aberrant signaling pathways associated with LDS genes. These included nocodazole, neostigmine bromide, scriptaid, trichostatin A, eugenol, aspirin, valproic acid, and ethosuximide (Table 4). Notably, many of the top candidates were HDAC inhibitors, supporting the hypothesis that lactylation dysregulation in AD may be driven by epigenetic mechanisms. Previous studies have shown that HDAC inhibitors can improve synaptic plasticity and cognitive function in AD animal models, highlighting their potential neuroprotective effects21. In addition, compounds associated with energy metabolism and microtubule stability were also identified, suggesting multiple possible intervention pathways targeting lactylation-related genes in AD. These findings provide preliminary insight into druggable mechanisms underlying lactylation dysregulation and broaden the translational potential of the LDS model in guiding personalized therapeutic development.

Discussion

Digital medicine aims to bridge AI-based computational models with clinically actionable, scalable diagnostics, a need that is particularly pressing in AD, where early and widely deployable tools remain limited. AD diagnosis in its early stages remains a formidable clinical challenge because traditional cognitive assessments, CSF biomarkers, and positron emission tomography (PET) imaging are often invasive, costly, or insufficiently sensitive during prodromal phases13,22,23. Blood-based biomarkers represent a promising alternative, but most existing assays primarily target hallmark AD pathologies such as amyloid-β and tau proteins, potentially overlooking broader molecular dysregulation12,24,25. In this context, we developed LDS, a blood-based, machine learning–derived multi-gene model based on lactylation-related gene signatures identified from brain transcriptomic data. LDS showed high diagnostic performance in the Training Cohort (AUC 0.897, 95% CI: 0.849–0.934) and maintained robust accuracy across seven external brain datasets. In the independent plasma cohort, RT-qPCR-based LDS achieved an AUC of 0.772 (95% CI: 0.728–0.815) with very high specificity, and DCA further supported its clinical utility and generalizability as a digital-medicine–oriented, blood-based diagnostic tool.

Our study also provides an objective comparison between LDS and established plasma p‑tau biomarkers. Consistent with prior literature26,27,28, p-tau217 outperformed p-tau181 in diagnostic accuracy (AUC 0.843, 95% CI: 0.802–0.882 vs. 0.828, 95% CI: 0.787–0.870), reflecting its stronger association with core tau pathology. However, single-analyte assays do not capture the immune–metabolic dysregulation represented by LDS. Integrating LDS with one or both p-tau markers using multivariable logistic regression significantly enhanced diagnostic performance; the three-marker model (LDS + p-tau181 + p-tau217) reached an AUC of 0.859 (95% CI: 0.822–0.893) while preserving high specificity. Notably, LDS alone already showed strong performance for identifying AT⁺ individuals (AUC 0.861), with further gains when combined with p-tau markers, highlighting the complementary value of protein-based and transcriptomic biomarkers for capturing AD’s complex pathophysiology.

LDS also showed tight links to disease severity and prodromal risk. LDS scores correlated significantly with MMSE and Braak stage, connecting the molecular signature to both cognitive impairment and neuropathological burden. In the plasma cohort, LDS scores were higher in aMCI than in NC and further elevated in AD, suggesting a stepwise progression. A five-gene aMCI classifier derived from LDS genes achieved good discrimination, and its combination with p-tau181 and p-tau217 yielded an AUC around 0.915 with high sensitivity for AT⁺ individuals, indicating that lactylation-related molecular alterations emerge early in the neurodegenerative process and may support early risk stratification, enrichment of high-risk aMCI, and disease monitoring.

The feasibility of using peripheral blood transcriptomic signatures to reflect central nervous system (CNS) pathology is supported by growing evidence of brain–blood molecular coupling. Although the blood–brain barrier (BBB) restricts free molecular exchange, its integrity is often compromised in neurodegenerative conditions, allowing CNS-derived proteins and RNA to appear in circulation29,30. Plasma p‑tau181 and p‑tau217 levels correlate with CSF concentrations and tau PET positivity, while Aβ42/Aβ40 ratios and NfL partially reflect amyloid deposition and axonal injury29,31. Our LDS findings extend this concept by demonstrating that peripheral transcriptomic patterns related to lactylation and immune–metabolic stress can serve as surrogates of central molecular alterations. These results support the biological plausibility of blood-based multi-gene diagnostics in AD.

From a mechanistic perspective, lactylation represents a novel epigenetic modification that links glycolytic metabolism to gene regulation32. Reactive astrocytes, which are central to neuroinflammatory cascades in AD, exhibit enhanced glycolysis and lactate accumulation, providing substrates for protein lactylation. GFAP, a core astrocytic marker and one of the LDS components, exemplifies this metabolic–epigenetic link33,34,35. Lactylation may influence GFAP expression, filament assembly, and interactions with other cytoskeletal or signaling proteins, potentially amplifying astrocytic reactivity. This modification could alter downstream inflammatory pathways including JAK‑STAT3 and NF‑κB, promote microglial activation, and contribute to T‑cell exhaustion, thereby accelerating neurodegeneration. In our study, high LDS scores were associated with immune checkpoint upregulation and activation of TNFα–NF-κB, JAK–STAT3, and complement pathways, whereas low LDS profiles exhibited more homeostatic neuroimmune and metabolic features. Together, these data suggest that astrocytic lactylation may serve as a mechanistic bridge between metabolic stress and neuroimmune dysregulation in AD.

Drug enrichment analysis further identified potential compounds targeting LDS-related pathways, including histone deacetylase inhibitors (valproic acid, scriptaid) and metabolic or cytoskeletal modulators such as nocodazole. These agents have demonstrated preclinical efficacy in restoring epigenetic balance, reducing Aβ deposition, and improving cognition32,36,37, highlighting the potential translational relevance of LDS for guiding therapeutic development.

Despite the promising results, this study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, most transcriptomic analyses were conducted on retrospectively collected GEO datasets, which may be affected by unmeasured confounders and platform-specific biases, even though we applied harmonized preprocessing and ComBat batch correction and validated LDS across multiple independent cohorts. Second, LDS was derived from bulk tissue and blood expression profiles and therefore does not capture cell type–specific or isoform-level lactylation changes; future single-cell and spatial studies will be needed to refine the underlying biology. Third, the independent clinical plasma cohort was recruited from a single center, and the generalizability of LDS to more diverse, community-based and multi-ethnic populations remains to be established. Fourth, our analyses are primarily diagnostic and observational; functional experiments were beyond the scope of this work, and causal mechanisms linking lactylation-related genes to AD onset and progression remain to be elucidated. Finally, we focused on a panel of seven lactylation-related genes; additional lactylation targets and complementary omics layers (e.g., proteomics, metabolomics) were not systematically integrated and may further improve model performance. These limitations should be addressed in future longitudinal, multi-omics and mechanistic studies to fully realize the translational potential of LDS.

Collectively, our findings demonstrate that lactylation-related gene signatures captured by the LDS model provide a robust, biologically interpretable blood-based biomarker for AD diagnosis and early risk stratification, including aMCI and AT⁺ individuals. By complementing established plasma p-tau markers, LDS enriches the molecular understanding of AD and could be integrated into electronic health records or digital health platforms as a machine learning–based risk score, enabling scalable, real-world screening and longitudinal monitoring.

Methods

Data acquisition, preprocessing, and identification of differentially expressed lactylation-related genes

A total of nine publicly available AD-related transcriptomic datasets were included in this study: GSE528138, GSE8442239, GSE12206340, GSE13290341, GSE2814642, GSE4835043, GSE3698044, GSE3726345, and GSE2937846. All datasets were obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database. Based on the dataset comparison summarized in Table 5, GSE5281 and GSE84422 were selected as the Training Cohort due to their relatively large sample sizes, rigorous diagnostic annotation, and consistent microarray platforms, enabling reliable harmonization and model construction. The remaining seven datasets were used as independent external validation cohorts to assess the robustness and generalizability of the LDS model across different brain regions (e.g., hippocampus, frontal cortex, neocortex), platforms (e.g., GPL570, GPL6947, GPL6244), populations (USA, Japan, Singapore), and diagnostic criteria (clinical diagnosis, Braak stage, MMSE, Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD), or autopsy). Detailed information regarding sample sources, profiling platform, demographic characteristics, brain regions, and diagnostic standards for each dataset is provided in Table 5.

To ensure analytical consistency, raw expression matrices and platform annotation files were downloaded using the “GEOquery” package in R47. Gene names were standardized based on probe annotation files. All datasets underwent log2 transformation and quantile normalization to minimize technical variation across different microarray platforms. Quality control was then performed using the “limma” package, and low-expression genes and outlier samples were removed.

To construct a unified Training Cohort, we selected GSE5281 and GSE84422 due to their large sample sizes and comparable tissue types. To address potential batch effects between the two datasets, we applied the ComBat algorithm from the “sva” package48. Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to visualize data distribution before and after batch correction, confirming the consistency of the merged cohort. After these preprocessing steps, we obtained a high-quality and standardized expression matrix for downstream analysis, including differential gene expression, functional annotation, immune landscape evaluation, and machine learning model construction.

Based on the merged Training Cohort, we performed differential expression analysis using the “limma” package. A linear modeling approach followed by empirical Bayes moderation was used to compare global gene expression between the AD and NC groups. Raw P values were adjusted for multiple testing using the Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) procedure, and both nominal and FDR-adjusted P values are reported in the corresponding Supplementary Data 2. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were defined as those with FDR < 0.05 and |log₂ fold change | ≥ 0.585, which corresponds to an absolute fold change of ≥ 1.5 and is commonly used to balance biological relevance and sensitivity in transcriptomic studies. To focus on lactylation-related biology, we obtained a curated list of 327 lactylation-related genes (LRGs) from published literature49. The intersection of DEGs and LRGs yielded 32 differentially expressed lactylation-related genes (DE-LRGs), which served as candidate diagnostic features for downstream analysis.

Consensus clustering and subtype classification

To identify potential molecular subtypes based on lactylation-related signatures, consensus clustering was performed using the “ConsensusClusterPlus” R package. The input matrix was composed of 32 DE-LRGs identified between AD and NC samples. The data were centered and scaled prior to clustering. We applied the partitioning around medoids (PAM) algorithm with Spearman correlation as the distance metric. Clustering was repeated over 500 bootstraps, with 80% of samples resampled in each iteration. The optimal number of clusters (K) was determined by jointly evaluating the consensus matrix heatmaps, cumulative distribution function (CDF) plots, delta area plot, and item-consensus distributions. K = 2 was selected as the optimal solution based on maximal cluster stability, separation, and interpretability. Detailed plots and rationale are provided in Supplementary Fig. 9.

Functional enrichment and immune landscape analysis

To investigate the biological mechanisms underlying lactylation-based subtypes, we performed pathway enrichment analyses using DEGs between the two subtypes (filter criteria: adjusted P < 0.05). Functional annotation was conducted using the “clusterProfiler” package in R. Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses were carried out, with gene annotation supported by the “org.Hs.eg.db” database. Significantly enriched terms were defined by a q-value < 0.05. Results were visualized using bubble and bar plots, highlighting differences in biological processes (BP), cellular components (CC), molecular functions (MF), and metabolic pathways across subtypes.

To further assess the activation status of hallmark pathways across samples, we applied Gene Set Variation Analysis (GSVA). Two reference gene sets— “c2.cp.kegg.v7.5.1.symbols.gmt” and “h.all.v7.5.1.symbols.gmt”—were used as background to evaluate enrichment score variations between lactylation-high and lactylation-low subtypes and between high-risk and low-risk LDS groups.

For immune microenvironment profiling, we integrated several computational algorithms, including Microenvironment Cell Populations-counter (MCP-counter)50, xCell50, quantification of the Tumor Immune contexture (quanTIseq)50, Immunophenoscore (IPS)51, and Estimation of STromal and Immune cells in MAlignant Tumor tissues using Expression data (ESTIMATE)52 to quantify the abundance of various immune and stromal cell populations. Specific attention was given to T cells, macrophages, dendritic cells, and regulatory T cells (Tregs) to capture key differences in immune cell infiltration across subgroups.

In addition, to explore immune regulation characteristics, we curated literature-based immune-related gene sets, including immune checkpoints, Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) molecules, immunostimulatory genes, and chemokines. Their expression profiles were compared across lactylation subtypes using heatmaps and boxplots. Immune functional scores were computed via the single-sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA) algorithm51, and radar plots were generated to visualize the immune activity landscape of different LDS risk groups.

Construction and multi-cohort validation of the LDS diagnostic model

To construct a lactylation-associated diagnostic model for AD, the DE-LRGs identified in the previous step were used as initial candidate variables. Model development followed a two-stage machine learning framework:

(1) Embedded feature selection: Five feature selection algorithms were applied, including Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) regression, generalized linear model boosting (glmBoost), random forest (RF), bidirectional stepwise generalized linear modeling (StepGLM [both]), and backward stepwise generalized linear modeling (StepGLM [backward]). These methods were used to identify stable and predictive variables from the DE-LRG set.

(2) Classification modeling: The selected features were then used to train twelve classification algorithms, including LASSO, Ridge regression, Elastic Net (ENet), support vector machine (SVM), RF, extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost), partial least-squares generalized linear modeling (plsRglm), glmBoost, Naïve Bayes, linear discriminant analysis (LDA), generalized boosted regression modeling (GBM), and StepGLM. In total, 113 models were generated—98 models using feature selection followed by classifier training and 15 models using the full DE-LRG set without prior feature filtering.

All models were trained within a unified machine learning framework implemented in R using the RunML platform. The pipeline included standardized preprocessing (z-score normalization of gene-expression features, i.e., centering to zero mean and scaling to unit variance based on the Training Cohort, with the same parameters applied to the external GEO and plasma cohorts), hyperparameter optimization through grid search or internal cross-validation, and performance evaluation using 10-fold cross-validation. Model-specific hyperparameter settings and search ranges are summarized in Supplementary Table 4. Model performance was quantified using area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), concordance index (C-index), accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity.

Model generalizability was assessed by first evaluating performance in the primary Training Cohort, followed by validation across seven independent external cohorts. To compare discriminative power among high-performing models, pairwise DeLong tests were conducted, with full results provided in Supplementary Data 3.

The final diagnostic framework, termed the LDS, was established using a two-step modeling strategy in which RF was first applied for feature stability screening, followed by model construction using plsRglm. This approach demonstrated the most consistent cross-cohort performance among all candidate pipelines. The resulting LDS consists of seven lactylation-associated genes—GFAP, GTF2I, RB1, PFKM, BCLAF1, SPR, and SMARCC1—selected based on their positive variable importance (VIMP > 0) in the RF feature selection stage, indicating reproducible predictive contribution. To characterize their individual diagnostic relevance, each gene was further evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis, expression profiling, and correlation assessment.

Finally, to benchmark the LDS against existing transcriptomic diagnostic signatures, eight previously published AD molecular models (Oxidative Stress-based model53, Cuproptosis-related model54, Metabolic model55, Mitochondrial Dysfunction model56, T cell receptor-based model57, 7-methylguanosine [m7G] model58, Immunogenic Cell Death [ICD] model59, and Chromatin Remodeling model60) were re-evaluated across all included cohorts. Pairwise DeLong tests demonstrated consistently superior or comparable diagnostic performance of LDS, with detailed comparisons summarized in Supplementary Data 3.

Model interpretation using Shapley additive explanations (SHAP)

To interpret the contribution of each gene to the LDS model, we applied SHAP. For the final RF + plsRglm classifier, SHAP values were computed for each sample to quantify the marginal contribution of each of the seven LDS genes to the model output (AD vs NC prediction). We summarized feature importance using the mean absolute SHAP value for each gene in the Training Cohort and visualized both the distribution and ranking of SHAP values. In addition, we repeated SHAP-based interpretation in each external GEO cohort and in the independent clinical plasma cohort to assess the stability of gene importance patterns across datasets.

Independent clinical plasma cohort: sample collection, LDS model validation, and aMCI risk stratification

The independent plasma cohort was prospectively enrolled at Zhongda Hospital, Southeast University, between January 2023 and December 2024. The study received approval from the institutional ethics committee (Approval No. 2024ZDSYLL172-PO1) and written informed consent was obtained from all participants in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

A total of 540 participants were included, consisting of 270 patients with AD, 90 individuals with aMCI, and 180 NC participants. AD diagnosis followed the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke–Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS-ADRDA) criteria and was confirmed by board-certified neurologists using standardized neuropsychological assessments61. aMCI was defined according to the Petersen criteria, requiring subjective memory decline, objective memory impairment, preserved general cognition, and intact daily functioning62. NC participants exhibited normal cognitive performance with MMSE ≥ 28 and no history of neurological, psychiatric, or major systemic disorders.

Fasting blood samples were collected, processed within 1 h by centrifugation at 4 °C, and stored at −80 °C. Plasma levels of mRNA expression of the seven LDS genes (GFAP, GTF2I, RB1, PFKM, BCLAF1, SPR, and SMARCC1) were quantified by Reverse Transcription Quantitative Real-time PCR (RT-qPCR), and p-tau181 and p-tau217 were measured using Single Molecule Array (Simoa) assays. All analyses were conducted in a blinded manner with respect to clinical diagnosis.

To evaluate the diagnostic generalizability of the LDS, the previously established seven-gene model was applied directly to the independent plasma cohort to discriminate AD from NC participants. Model performance was assessed using ROC analysis, reporting AUC, sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy with 95% confidence interval (CI). In addition to evaluating LDS, p-tau181, and p-tau217 separately, we constructed multivariable logistic regression models that incorporated LDS together with p-tau181 and/or p-tau217 as predictors for AD vs NC. Participants were further stratified into AT⁺ and AT⁻ groups based on predefined biomarker thresholds, and analogous logistic regression models were fitted to assess the ability of LDS and its combinations with p-tau181/217 to identify AT⁺ individuals.

To assess the potential of LDS-associated transcriptional alterations for early-stage detection, a separate aMCI classifier was independently developed, rather than derived from the AD–NC model. This classifier was built using the five LDS genes most consistently upregulated in aMCI (GFAP, GTF2I, BCLAF1, SPR, and SMARCC1). Four machine-learning algorithms—RF, SVM, logistic regression, and LASSO—were trained under 10-fold cross-validation, and feature importance in RF was quantified using the Gini index. For downstream clinical application, we further used logistic regression to build integrated models that combined the RF-derived gene-expression risk score with p-tau181 and/or p-tau217 to evaluate their additive value in detecting aMCI, including AT⁺ cases. Clinical and functional assessments included age, sex, MMSE score, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), Nutritional Risk Screening 2002 (NRS2002), Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS), Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS), Fatigue, Resistance, Ambulation, Illnesses, and Loss of weight (FRAIL) scale, Activities of Daily Living (ADL) score. (Table 6).

Detection of lactylation-related gene expression

Total RNA was extracted from plasma using the TRIzol LS reagent (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany), and RNA concentration and purity were assessed by NanoDrop spectrophotometry. cDNA synthesis was performed using the HiScript III RT SuperMix kit (Vazyme Biotech, China). RT-qPCR was conducted using Taq Pro Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme Biotech, China) on the 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, USA). The thermal cycling protocol included an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 seconds and annealing at 60 °C for 30 s, repeated for 40 cycles, with a total reaction volume of 20 μL. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as the internal control, and all reactions were performed in technical triplicates. Primer sequences for the key lactylation-related genes are listed in Supplementary Table 5. Relative gene expression levels were calculated using the 2–ΔΔCT method.

Plasma p-tau181 and p-tau217 Quantification

Plasma levels of p-tau181 and p-tau217 were measured using Simoa technology (CJC-Di6000A, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The assay utilizes capture antibodies specific for the phosphorylated tau epitopes immobilized on paramagnetic beads, combined with biotinylated detection antibodies and streptavidin-β-galactosidase enzyme conjugates, enabling ultrasensitive digital quantification of target proteins. Calibration curves were constructed using recombinant p-tau standards, and concentrations were calculated using a four-parameter logistic regression model. Quality control samples were included to monitor assay performance. All analyses were performed blinded to clinical diagnosis.

Identification of candidate therapeutic agents

To explore potential therapeutic compounds targeting the key genes identified in the LDS model, we performed drug enrichment analysis using the Drug Signature Database (DSigDB) module on the Enrichr platform (https://maayanlab.cloud/Enrichr/), which integrates drug–gene interaction data. The seven key lactylation-related genes from the LDS model were input into the Enrichr system, and enrichment analysis was conducted to identify small molecules significantly associated with these targets. Compounds were ranked based on enrichment scores, and those with a P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The top-ranked candidate agents were extracted, many of which were associated with epigenetic regulation or energy metabolism, such as histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors and microtubule modulators.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.3.1). For continuous variables, normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Normally distributed variables were compared using Student’s t-test (two groups) or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (≥3 groups), and non-normally distributed variables were compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test or Kruskal–Wallis test. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square (χ²) test or Fisher’s exact test. Associations between continuous variables (e.g., LDS, p-tau181, p-tau217, clinical and neuropathological scores) were evaluated using Spearman’s rank correlation and reported as correlation coefficients (r) with corresponding P values.

Diagnostic performance of LDS, p-tau181, p-tau217, and their combinations, as well as aMCI classifiers, was evaluated using ROC analysis. AUCs, sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy were reported with 95% CI. Differences between AUCs were assessed using two-sided DeLong tests; when multiple models were compared, P values from DeLong tests were adjusted using the Benjamini–Hochberg FDR method. Calibration curves for the LDS and combined models were generated using bootstrap resampling to compare predicted versus observed event probabilities, and decision curve analysis (DCA) was used to quantify standardized net benefit across a range of threshold probabilities.

For analyses involving multiple comparisons (e.g., differential expression, pathway enrichment, subtype comparisons, and correlation heatmaps), P values were corrected using the Benjamini–Hochberg FDR procedure, and FDR < 0.05 was considered significant. Unless otherwise specified, all other P values are two-sided and unadjusted, with P < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Data availability

The public transcriptomic datasets used in this study were obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database under accession numbers GSE5281, GSE84422, GSE122063, GSE132903, GSE28146, GSE48350, GSE36980, GSE37263, and GSE29378. These datasets are freely available at “https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/. The independent plasma cohort data generated and analyzed during this study are not publicly available due to ethical and privacy restrictions but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and with appropriate institutional approval.

Code availability

The analytical codes involved in this study can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

2021 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement 2021, 17:327-406.

Granzotto, A. & Sensi, S. L. Once upon a time, the Amyloid Cascade Hypothesis. Ageing Res. Rev. 93, 102161 (2024).

Apostolova, L. G. Alzheimer disease. Continuum 22, 419–434 (2016).

Muhigwa, A. & Kalenzaga, S. Psychological and behavioral symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: Impact on professional caregivers burden and non-pharmacological management strategies. NPG Neurologie Psychiatr. Gériatrie 25, 203–210 (2025).

Leidal, A. M., Levine, B. & Debnath, J. Autophagy and the cell biology of age-related disease. Nat. Cell Biol. 20, 1338–1348 (2018).

Scheltens, P. et al. Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet 397, 1577–1590 (2021).

Congdon, E. E., Ji, C., Tetlow, A. M., Jiang, Y. & Sigurdsson, E. M. Tau-targeting therapies for Alzheimer disease: current status and future directions. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 19, 715–736 (2023).

Karran, E. & De Strooper, B. The amyloid hypothesis in Alzheimer disease: new insights from new therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 21, 306–318 (2022).

Zagórska A., Czopek A., Fryc M., Jaromin A. & Boyd B. J. Drug discovery and development targeting dementia. Pharmaceuticals 16, (2023).

Sharon O. et al. Slow wave synchrony during NREM sleep tracks cognitive impairment in prodromal Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 21, (2025).

Ostrowitzki, S. et al. Evaluating the safety and efficacy of crenezumab vs placebo in adults With Early Alzheimer disease: two phase 3 randomized placebo-controlled trials. JAMA Neurol. 79, 1113–1121 (2022).

Karikari, T. K. et al. Diagnostic performance and prediction of clinical progression of plasma phospho-tau181 in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Mol. Psychiatry 26, 429–442 (2021).

Dubois, B., von Arnim, C. A. F., Burnie, N., Bozeat, S. & Cummings, J. Biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease: role in early and differential diagnosis and recognition of atypical variants. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 15, 175 (2023).

Zhou, J. et al. Astrocytic LRP1 enables mitochondria transfer to neurons and mitigates brain ischemic stroke by suppressing ARF1 lactylation. Cell Metab. 36, 2054–2068.e2014 (2024).

Yang, H. et al. Microglia lactylation in relation to central nervous system diseases. Neural Regen. Res. 20, 29–40 (2025).

Xu, K., Zhang, K., Wang, Y. & Gu, Y. Comprehensive review of histone lactylation: structure, function, and therapeutic targets. Biochem. Pharm. 225, 116331 (2024).

Zhang, D. et al. Metabolic regulation of gene expression by histone lactylation. Nature 574, 575–580 (2019).

Yang, Z. et al. Lactylome analysis suggests lactylation-dependent mechanisms of metabolic adaptation in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Metab. 5, 61–79 (2023).

Yang, K. et al. Lactate promotes macrophage HMGB1 lactylation, acetylation, and exosomal release in polymicrobial sepsis. Cell Death Differ. 29, 133–146 (2022).

Zhang, T., Huang, Q. & Gan, K. F. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomal lactate dehydrogenase A promotes tendon-bone healing via histone lactylation-mediated cartilage regeneration. World J. Stem Cells 17, 106282 (2025).

Gräff, J. et al. An epigenetic blockade of cognitive functions in the neurodegenerating brain. Nature 483, 222–226 (2012).

Calil, V. et al. Challenges in the diagnosis of dementia: insights from the United Kingdom-Brazil Dementia Workshop. Dement. Neuropsychol. 14, 201–208 (2020).

Landau, S. M. et al. Amyloid PET imaging in Alzheimer’s disease: a comparison of three radiotracers. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 41, 1398–1407 (2014).

Chong, J. R. et al. Plasma P-tau181 to Aβ42 ratio is associated with brain amyloid burden and hippocampal atrophy in an Asian cohort of Alzheimer’s disease patients with concomitant cerebrovascular disease. Alzheimers Dement. 17, 1649–1662 (2021).

Janelidze, S. et al. Head-to-Head Comparison of 8 Plasma Amyloid-β 42/40 Assays in Alzheimer Disease. JAMA Neurol. 78, 1375–1382 (2021).

Mendes, A. J. et al. Head-to-head study of diagnostic accuracy of plasma and cerebrospinal fluid p-tau217 versus p-tau181 and p-tau231 in a memory clinic cohort. J. Neurol. 271, 2053–2066 (2024).

Kirsebom, B. E. et al. Repeated plasma p-tau217 measurements to monitor clinical progression heterogeneity. Alzheimers Dement. 21, e70319 (2025).

Kahouadji, S. et al. Evaluation of serum NFL, T-tau, p-tau181, p-tau217, Aβ40 and Aβ42 for the diagnosis of neurodegenerative diseases. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. (2024).

Mielke, M. M. et al. Comparison of plasma phosphorylated tau species with amyloid and tau positron emission tomography, neurodegeneration, vascular pathology, and cognitive outcomes. JAMA Neurol. 78, 1108–1117 (2021).

Muir, R. T., Ismail, Z., Black, S. E. & Smith, E. E. Comparative methods for quantifying plasma biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease: implications for the next frontier in cerebral amyloid angiopathy diagnostics. Alzheimers Dement. 20, 1436–1458 (2024).

Graham, N. S. N. et al. Axonal marker neurofilament light predicts long-term outcomes and progressive neurodegeneration after traumatic brain injury. Sci. Transl. Med. 13, eabg9922 (2021).

Guo, S. et al. Developing diagnostic biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease based on histone lactylation-related gene. Heliyon 10, e37807 (2024).

Harris, R. A. et al. Aerobic glycolysis in the frontal cortex correlates with memory performance in wild-type mice but not the APP/PS1 mouse model of cerebral amyloidosis. J. Neurosci. 36, 1871–1878 (2016).

Weaver, K. E. et al. Posterior cingulate lactate as a metabolic biomarker in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 610605 (2015).

Liguori, C. et al. CSF lactate levels, τ proteins, cognitive decline: a dynamic relationship in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 86, 655–659 (2015).

Gao, Y., Aljazi, M. B., Wu, Y. & He, J. Vorinostat, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, ameliorates the sociability and cognitive memory in an Ash1L-deletion-induced ASD/ID mouse model. Neurosci. Lett. 764, 136241 (2021).

Liu, J., Wang, L. N. & Jia, J. P. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma agonists for Alzheimer’s disease and amnestic mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drugs Aging 32, 57–65 (2015).

Readhead, B. et al. Multiscale analysis of independent Alzheimer’s cohorts finds disruption of molecular, genetic, and clinical networks by human herpesvirus. Neuron 99, 64–82.e67 (2018).

Wang, M. et al. Integrative network analysis of nineteen brain regions identifies molecular signatures and networks underlying selective regional vulnerability to Alzheimer’s disease. Genome Med. 8, 104 (2016).

McKay, E. C. et al. Peri-infarct upregulation of the oxytocin receptor in vascular dementia. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 78, 436–452 (2019).

Piras, I. S. et al. Transcriptome changes in the Alzheimer’s disease middle temporal gyrus: importance of RNA metabolism and mitochondria-associated membrane genes. J. Alzheimers Dis. 70, 691–713 (2019).

Blalock, E. M., Buechel, H. M., Popovic, J., Geddes, J. W. & Landfield, P. W. Microarray analyses of laser-captured hippocampus reveal distinct gray and white matter signatures associated with incipient Alzheimer’s disease. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 42, 118–126 (2011).

Sárvári, M. et al. Menopause leads to elevated expression of macrophage-associated genes in the aging frontal cortex: rat and human studies identify strikingly similar changes. J. Neuroinflammation 9, 264 (2012).

Hokama, M. et al. Altered expression of diabetes-related genes in Alzheimer’s disease brains: the Hisayama study. Cereb. Cortex 24, 2476–2488 (2014).

Tan, M. G. et al. Genome wide profiling of altered gene expression in the neocortex of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. Res. 88, 1157–1169 (2010).

Yao Z. et al. Age-related decline in hippocampal tyrosine phosphatase PTPRO is a mechanistic factor in chemotherapy-related cognitive impairment. JCI Insight 8 (2023).

Davis, S. & Meltzer, P. S. GEOquery: a bridge between the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) and BioConductor. Bioinformatics 23, 1846–1847 (2007).

Leek, J. T., Johnson, W. E., Parker, H. S., Jaffe, A. E. & Storey, J. D. The sva package for removing batch effects and other unwanted variation in high-throughput experiments. Bioinformatics 28, 882–883 (2012).

Sun, Z. et al. Construction of a lactate-related prognostic signature for predicting prognosis, tumor microenvironment, and immune response in kidney renal clear cell carcinoma. Front. Immunol. 13, 818984 (2022).

Zeng, D. et al. IOBR: multi-omics immuno-oncology biological research to decode tumor microenvironment and signatures. Front. Immunol. 12, 687975 (2021).

Charoentong, P. et al. Pan-cancer immunogenomic analyses reveal genotype-immunophenotype relationships and predictors of response to checkpoint blockade. Cell Rep. 18, 248–262 (2017).

Yoshihara, K. et al. Inferring tumour purity and stromal and immune cell admixture from expression data. Nat. Commun. 4, 2612 (2013).

Zhang, Y. & Kiryu, H. Identification of oxidative stress-related genes differentially expressed in Alzheimer’s disease and construction of a hub gene-based diagnostic model. Sci. Rep. 13, 6817 (2023).

Nie, B. et al. Systematic analysis of cuproptosis-related genes in immunological characterization and predictive drugs in Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 15, 1204530 (2023).

Li, J. et al. Identification of diagnostic genes for both Alzheimer’s disease and Metabolic syndrome by the machine learning algorithm. Front. Immunol. 13, 1037318 (2022).

Zhang, Y. et al. Identification of mitochondrial related signature associated with immune microenvironment in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Transl. Med. 21, 458 (2023).

Guo, W. et al. Exploring the interaction between T-cell antigen receptor-related genes and MAPT or ACHE using integrated bioinformatics analysis. Front. Neurol. 14, 1129470 (2023).

Ma, C. et al. Identification and prediction of m7G-related Alzheimer’s disease subtypes: insights from immune infiltration and machine learning models. Front. Aging Neurosci. 15, 1161068 (2023).

Wang, R. et al. Identification of immunogenic cell death-related genes involved in Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Rep. 14, 3786 (2024).

Xiong, F. et al. Identification of chromatin regulatory factors related to immunity and treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Mol. Neurosci. 73, 85–94 (2023).

Croisile, B., Auriacombe, S., Etcharry-Bouyx, F. & Vercelletto, M. [The new 2011 recommendations of the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease: preclinical stages, mild cognitive impairment, and dementia]. Rev. Neurol. 168, 471–482 (2012).

Petersen, R. C. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J. Intern. Med. 256, 183–194 (2004).

Acknowledgements

This work was Supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82373781), Jiangsu Provincial Medical Key Discipline (Laboratory) Cultivation Unit (JSDW202240), the Jiangsu Provincial Key Laboratory of Critical Care Medicine (JSKLCCM202202015), Southeast University Doctoral Students Innovation Ability Enhancement Program (CXJH_SEU_24219), Zhongda Hospital Affiliated to Southeast University, Jiangsu Province High-Level Hospital Pairing Assistance Construction Funds (zdlyg09) and Health Research project of Health Commission of Jiangsu Province (BJ23014).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception or design: S.M., D.W.C., Y.H.C., G.Q.W. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: S.M., D.W.C., Y.H.C., G.Q.W. Sample collection and data processing: Y.Z.L., M.L.Z., J.W.W., Y.M.Y., Y.X.L. Drafting the work or revising: S.M., Y.H.C. Final approval of the manuscript: all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, S., Chen, D., Li, Y. et al. A machine learning–enabled blood transcriptomic signature for digital diagnosis and subtyping of Alzheimer’s disease. npj Digit. Med. 9, 126 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02305-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02305-7