Abstract

In mammalian females, the transition from dormancy in primordial follicles to follicular development is critical for maintaining ovarian function and reproductive longevity. In mice, the quiescent primary oocyte of the primordial follicle contains a Balbiani body (B-body), an organelle aggregate comprised of a spherical structure of Golgi complexes. Here we show that the structure of the B-body is maintained by microtubules and actin. The B-body stores mRNA-capping enzyme and 597 mRNAs associated with mRNA-decapping enzyme 1 A (DCP1A). Gene ontology analysis results indicate that proteins encoded by these mRNAs function in enzyme binding, cellular component organization and packing of telomere ends. Pharmacological depolymerization of microtubules or actin led to B-body disassociation and nascent protein synthesis around the dissociated B-bodies within three hours. An increased number of activated developing follicles were observed in ovaries with prolonged culture and the in vivo mouse model. Our results indicate that the mouse B-body is involved in the activation of dormant primordial follicles likely via translation of the B-body-associated RNAs in primary oocytes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In mammalian females, normal ovarian function is sustained by a pool of primordial follicles, namely the ovarian reserve1. Each primordial follicle contains a quiescent primary oocyte and a single layer of pregranulosa cells. Coordinated quiescence in primary oocytes and pregranulosa cells is essential for maintaining dormancy in primordial follicles. In adult ovaries, a cohort of primordial follicles activates periodically to undergo follicular development, supporting female fertility and hormone production2.

The transition from dormancy to development in primordial follicles is likely regulated by intrinsic signaling and extrinsic factors. PTEN-PI3K (phosphatase and tensin homolog-phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase) pathway in primary oocytes is an intrinsic factor regulating quiescence in mice and humans3,4,5. In adult mouse ovaries with oocyte-specific Pten knockout, as well as in neonatal mouse ovaries and human ovarian tissues cultured with the PTEN inhibitor, bpV(pic), overactivation of primordial follicles was observed3,6. FOXO3a (forkhead box O3) is involved in primordial follicle activation in a PI3K-dependent manner. In mouse oocytes, FOXO3a activity is regulated by nucleocytoplasmic shuttling. FOXO3a is located in the cytoplasm of the germ cell during primordial follicle formation in postnatal day 1 (P1) mouse ovaries; in both the nucleus and cytoplasm of the primary oocyte in P3-P7 ovaries; and just in the nucleus of the primary oocyte in P14 and adult ovaries6,7. In Foxo3 null mice and the mice with oocyte-specific Foxo3 depletion, overactivation of primordial follicles led to a complete loss of ovarian follicles by 15 weeks8,9.

Forkhead box L2 (FOXL2) and Anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) are two extrinsic factors regulating primordial follicle dormancy. FOXL2 is a transcription factor that is expressed in pregranulosa cells in mouse fetal ovaries and the granulosa cells of ovarian follicles in adult mouse ovaries10,11. AMH is produced by granulosa cells of developing follicles (primary follicle stage and beyond) in mouse ovaries, and inhibits primordial follicle activation in cultured neonatal mouse ovaries and human ovarian tissues12,13. Primordial follicle overactivation phenotype was observed in postnatal ovaries of Foxl2 mutant mice and adult ovaries of Amh null mice10,11,14.

The Balbiani body (B-body) is a highly conserved, oocyte-specific cellular structure observed in invertebrates and vertebrates. The B-body is characterized by an organelle aggregate that has functions in RNA storage and translational regulation15,16,17. In the oocytes of Drosophila, zebrafish and Xenopus, the B-body contains mitochondria, Golgi complexes, endoplasmic reticulum (ER), proteins, and RNA granules. The RNAs segregated within the B-body play an essential role in specifying germ cells in early embryos via translational regulation15,16,17,18,19,20,21. The B-body has been observed in the oocytes of many mammalian species16,17,22,23,24. In both mice and humans, the B-body is found in the quiescent primary oocyte of the primordial follicle, and comprises mitochondria, Golgi complexes, and ER22,23,24,25,26. The mouse B-body contains a spherical aggregate of Golgi complexes, mitochondria are highly enriched around the Golgi aggregate during B-body formation in fetal germ cells and in some primary oocytes in postnatal ovaries (Fig. 1A, B)23,26,27. A recent study proposed that mouse primary oocytes do not contain a B-body due to the lack of consistent mitochondrial clusters around the spherical Golgi complexes28. However, an organelle aggregate functioning in RNA storage and translational regulation defines the B-body morphologically and functionally15,29.

A An EM image showing the cross-section of a B-body (arrow) in the quiescent primary oocyte at low-magnification. A’ A high-magnification EM image showing the cross-section of a B-body - highly stacked Golgi complexes in a circular structure. B A B-body stained by Golgi cis-face marker GM130 in a VASA-positive quiescent primary oocyte. B’ 3-D reconstructed image showing a B-body in a spherical structure. Co-immunostaining of the B-body by using GM130 and TGN46 (C), COPII (D), Clathrin (E), RNA green dye (F), PABPC (G), 7-methylguanosine (H), MIWI (I), MILI (J), AGO2 (K), EIF4E (L), ribosomal protein S6 (M), FMRP (N), GW182 (O), DDX6 (P), DCP2 (Q), DCP1A1-350 (R), DCP1A500-C (S), DCP1A300-400 (T), and mRNA-capping enzyme (mRNACE) (U). The antibody staining was repeated at least three times independently, and minimum n = 60 oocytes were examined to ensure that consistent staining results were observed. Confocal images from a single representative optical section are shown in the figure.

In the present study, we recognized and located the mouse B-body by the spherical structure of Golgi aggregate. We found that the B-body encloses RNAs and proteins involved in translational regulation. The integrity of the B-body maintained by actin and microtubules is involved in primary oocyte quiescence. Pharmacological depolymerization of actin or microtubules in cultured neonatal ovaries led to B-body disassociation and nascent protein synthesis around disassociated B-bodies within three hours. An increased number of developing follicles was observed in the inhibitor-treated ovaries in both culture and in vivo mouse models. Primordial follicle activation was prevented when translation was inhibited after B-body disassociation. Our study suggests that B-body-mediated RNA storage is involved in regulating the transition from quiescence to development in mouse primary oocytes.

Results

The mouse B-body compartments organelles, proteins and RNAs in the primary oocyte

To understand the molecular content and function of the mouse B-body, we determined how B-body Golgi complexes are organized together with other organelles and proteins in the primary oocyte. We found that the cis-faces of the Golgi (marked by GM130) were exposed to the cytosol, and the trans-faces of the Golgi (marked by TGN46) were enclosed in the lumen of the B-body, where centrosomes are located (Fig. 1B, C, Supplementary Fig. 1)26. This distribution of organelles is distinct from most somatic cells where the centrosome sits between the nucleus and Golgi cis-face30. Electron microscopy (EM) revealed many small vesicles residing inside and outside of the B-body (Fig. 1A). We analyzed the nature of these vesicles by staining primary oocytes with a COPII antibody, which labels ER-to-Golgi transport vesicles, and with a clathrin antibody, which marks secretory vesicles released from the Golgi trans-face31. Abundance of these proteins inside and outside of the B-body was examined by comparing the fluorescence intensity of antibody-stained primary oocytes (Supplementary Table 1). COPII-positive vesicles distributed throughout the cytoplasm, but were relatively less abundant in the B-body (Fig. 1D, Supplementary Table 1). By contrast, clathrin-positive vesicles were enriched inside the B-body and also across the cis-face of the Golgi complexes (Fig. 1E, Supplementary Table 1).

Enrichment of Trailer Hitch (TRAL), a protein involved in RNA metabolism, in the mouse B-body has led to the proposal that the B-body functions in RNA storage23. To directly detect RNAs in the B-body, we stained primary oocytes with an RNA-binding dye (SYTO RNASelect Green Fluorescent Cell Stain). Specificity of the dye was validated by strong positive signals in the cytoplasm and the nucleolus, but not in the rest of the nucleus. Compared with RNA abundance in the cytoplasm, RNA content was lower in the B-body lumen (Fig. 1F, Supplementary Table 1). Similarly, poly(A)-binding protein (PABPC), which interacts with mRNA poly(A) tails in the cytoplasm, was present at a lower level in the B-body lumen compared with the oocyte cytoplasm (Fig. 1G, Supplementary Table 1)32,33. However, examining the distribution of mRNA 5’-caps, using the anti-7-methylguanosine antibody, revealed a comparable level of 7-methylguanosine between the inside and outside the B-body (Fig. 1H, Supplementary Table 1)34,35. To elucidate whether or not the B-body contains small RNAs, we stained primary oocytes using antibodies to MIWI (PIWI-like protein 1) and MILI (PIWI-like protein 2), which interact with piRNAs; and Argonaute 2 (AGO2), a major component of the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) that represses translation by interacting with miRNAs and endo-siRNAs36,37,38,39. MILI protein was excluded from the B-body, but in clusters of foci in the oocyte cytoplasm (Fig. 1J). MIWI and AGO2 proteins showed a relative homogenous distribution in the oocyte cytoplasm, as well as both inside and outside of the B-body, suggesting that small RNA-mediated translation repression may be involved in the B-body (Fig. 1I, K).

We asked whether proteins involved in translational regulation are present within the B-body40. Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (EIF4E), a protein required for translation initiation, was found both inside and outside of the B-body (Fig. 1L). By contrast, ribosomal protein S6, which is required for translation elongation, was absent inside the B-body, suggesting a low protein synthesis activity within the B-body (Fig. 1M). We further examined the expression of several RNA binding proteins involved in translational regulation. Fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP), a polyribosome-associated RNA binding protein that mainly functions in repressing mRNA translation, was only found outside of the B-body (Fig. 1N). The RNA binding protein GW182, which is involved in miRNA-mediated translational silencing, was found in the cytoplasm and within the B-body (Fig. 1O)41,42. Similarly, DEAD-box helicase 6 (DDX6), which is involved in processing body (P-body) and stress granule assembly, was found in the cytoplasm and inside of the B-body (Fig. 1P)43,44. mRNA-decapping enzyme 2 (DCP2), a co-factor involved in removing the mRNA 5′ cap and thus facilitating RNA storage or degradation, was detected in the form of granules and found in the cytoplasm and inside of the B-body (Fig. 1Q)45. Intriguingly, mRNA-decapping enzyme 1 A (DCP1A), showed distinct distribution patterns when using antibodies targeting different regions of the protein. The antibody targeting amino acids 1-350 of human DCP1A detected small foci in the oocyte cytoplasm and inside of the B-body. It also detected large foci in the surrounding pregranulosa cells (https://www.ptglab.com/products/DCP1A-Fusion-Protein-ag18027.htm) (Fig. 1R). The antibody targeting amino acid 500 to the C-terminus of the protein detected several small granules in the oocyte cytoplasm and the B-body, as well as in pregranulosa cells (Fig. 1S). The antibody targeting amino acids 300-400 specifically detected protein located on the inner side of the B-body Golgi cis-face in primary oocytes (Fig. 1T). A similar distribution of DCP1A protein in mouse primary oocytes was also observed by a previous study46. Like DCPA1300-400, the mRNA-capping enzyme (mRNACE) was highly enriched inside of the B-body (Fig. 1U, Supplementary Table 1). These observations suggest that the mouse B-body may have functions of RNA storage and translational regulation, possibly via DCP1A and mRNA-capping enzyme.

The mouse B-body is maintained by actin and microtubules

The B-body is only observed in quiescent primary oocytes (Fig. 1A). EM images revealed that in activated oocytes of developing follicles, recognized by enlarged oocytes and cuboidal shaped granulosa cells, the spherical structure of the B-body was dispersed (Fig. 2A, n = 97 developing oocytes examined in 74 EM sections from four independent ovaries)47. This observation was also confirmed by confocal imaging of Golgi morphology in the oocytes stained with a GM130 antibody (Supplementary Movie 1). To investigate how the integrity of the B-body is maintained, we examined the distribution of cytoskeleton proteins in quiescent primary oocytes48,49. We found that α-tubulins were co-localized with the B-body Golgi cis-face, suggesting a close interaction between microtubules and Golgi cis-face (Fig. 2B). Stable microtubules, represented by acetylated tubulins, were observed both outside and inside the B-body Golgi complexes (Fig. 2C, Supplementary Movie 2). Despite enriched tubulins on the B-body and the localization of centrosomes inside the B-body, microtubule minus-end binding protein CAMSAP3 and plus-end tracking protein EB1 were evenly distributed in the primary oocyte and were detected both inside and outside of the B-body (Fig. 2D, E)50,51. This result indicates that microtubules may not align in a polarized manner in the primary oocyte. Unlike tubulins, F-actin, detected by phalloidin, was in several clusters around the B-body (Fig. 2F, Supplementary Table 1). Proteomic analysis of primordial follicles (containing quiescent primary oocytes with B-bodies) and developing follicles (containing activated oocytes with disassociated B-bodies) identified 35 actin-related proteins and 31 tubulin-related proteins (Fig. 2G, Supplementary Table 2, Supplementary Data 1). These proteins may potentially interact with actin and microtubules to regulate B-body integrity.

A, A’ EM images showing a disassociated B-body in an activated follicle. B–F Distributions of α-tubulin (B), acetylated-tubulin (C), CAMSAP3 (D), EB1 (E), and F-actin (F) in quiescent primary oocytes. The antibody staining was repeated three times independently (minimum n = 60 oocytes were examined), confocal images from a single representative optical section are shown in the figure. G Heatmaps of Actin-related proteins and tubulin-related proteins detected by mass spectrometry in quiescent primordial follicles (QF) and developing follicles (DF). The expression level is shown as normalized spectral count.

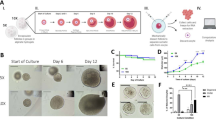

To directly test the role of microtubules and actin in maintaining B-body integrity, we used an in vitro ovary culture model to manipulate microtubule or actin dynamics within cells. Postnatal day 4 (P4) ovaries, in which ~90% of the follicles are quiescent primordial follicles, were dissected and incubated with polymerization inhibitors of actin (cytochalasin D at 10 µM) or tubulin (nocodazole at 10 µM) for two hours (2 h), then cultured for additional six days (6 d) to allow activated follicles to grow (Fig. 3A)52,53. After a 2 h inhibitor treatment, percentages of primary oocytes containing a B-body in control, cytochalasin D-treated, or nocodazole-treated ovaries were 85.9%, 44.6%, and 29.5%, respectively, indicating both inhibitors significantly disrupted B-body integrity. Moreover, 2 h incubation of the combination of two inhibitors (cytochalasin D and nocodazole) caused an increased disruption of B-body with 19.2% of the primary oocytes still contained a B-body (Fig. 3B, C, Supplementary Data 2). In cytochalasin D-treated primary oocytes, B-body Golgi complexes remained linear and clustered, but had lost their spherical structure. In nocodazole-treated primary oocytes, B-body Golgi complexes fragmented into small pieces and dispersed throughout the primary oocyte (Fig. 3B). This result indicates that microtubules and actin may function differently in maintaining the spherical structure of the B-body.

A Schemes of neonatal mouse ovary culture and mouse injection. B Immunostaining of GM130 showing the Golgi complex morphology after a 2 h-drug treatment (arrowheads: B-bodies; arrows: disassociated B-bodies). C Percentages of primary oocytes containing a B-body in the ovaries after a 2 h drug treatment. D Ovarian morphology of drug-treated ovaries after 6 days culture. E Numbers of developing follicles in each drug-treated ovary after 6 days culture. F Numbers of developing follicles in each P10 ovary after the drug injection. Nascent protein synthesis revealed by fluorescent positive O-propargyl-puromycin (OPP) foci in the ovaries treated with cytochalasin D (cytoD) for 2 h (G–K) and cytochalasin D plus cycloheximide (cyclo) for 2 h followed by cycloheximide for 1 h (L). M Numbers of developing follicles in each drug-treated ovary after 6 days culture. Drug treatment in cultured ovaries and injection were repeated three times independently. N = 60 oocytes were examined for OPP distribution. Confocal images from a single representative optical section are shown in the figure. Quantification results were analyzed statistically by using one-way ANOVA and shown as Mean ± SD, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant *.

Primordial follicle activation and nascent protein synthesis upon B-body disassociation

To elucidate whether the loss of B-body integrity is associated with primordial follicle activation, we analyzed ovarian morphology of inhibitor-treated ovaries after 6 days culture. In postnatal mouse ovaries, primordial follicles are located in the cortex area of the ovary; developing follicles are located in the center of the ovary and characterized by enlarged oocytes (over 25 μm in diameter) surrounded by one to multiple layers of cuboidal granulosa cells2,54. The inhibitor-treated ovaries contained a significantly increased number of developing follicles, recognized by the larger volume of VASA+ oocytes (Fig. 3D, Supplementary Fig. 2). On average, 73.8 ± 21.9 developing follicles per ovary were found in control, versus 154.8 ± 11.7 in cytochalasin D-treated ovaries, 124.4 ± 20.5 in nocodazole-treated ovaries, and 143.1 ± 21.8 in cytochalasin D and nocodazole combination-treated ovaries (Fig. 3E, Supplementary Data 2). A similar effect of follicle activation was also observed when we injected cytochalasin D or nocodazole to P4 mice, about two times more developing follicles were found in ovaries of injected mice than control mice (Fig. 3A, F, Supplementary Data 2). A roughly ten-fold difference in developing follicle numbers observed between the in vitro and in vivo experiments may be due to the sub-optimal follicle development condition of in vitro culture compared with physiological condition of the in vivo model. These results demonstrate that primordial follicle activation as the result of disrupted actin or microtubules may involve B-body disassociation. We noticed that compared with control and cytochalasin D-treated ovaries, nocodazole-treated ovaries were smaller in size, developing follicles were near the ovarian surface and appeared to be deformed. Whereas in control and cytochalasin D-treated ovaries, developing follicles remained in the center of the ovary. This indicates that nocodazole may have caused more negative effects on overall ovarian morphology and structure. Due to this reason, we used cytochalasin D in our subsequent study for B-body disassociation.

Previous studies and our present work suggest that the B-body may have the function of RNA storage23. To reveal whether protein synthesis takes place around the B-body after its disassociation, O-propargyl-puromycin (OPP) was added to the cultured ovaries at various time points after a 2 h incubation of cytochalasin D to label newly synthesized proteins55,56. At 0.5 h after removing cytochalasin D, OPP-positive protein foci were observed near the disassociated B-bodies (Fig. 3H, arrows) but were absent around the intact B-bodies (Fig. 3G, arrowheads). Protein foci were most abundant around disassociated B-bodies 1 h after cytochalasin D removal (Fig. 3I). By 2 h, foci became more dispersed in the cytoplasm (Fig. 3J), and by 3 h, almost no foci were observed in the primary oocytes with disassociated B-bodies (Fig. 3K). When we inhibited protein synthesis by culturing the ovaries with cycloheximide (10 µg/ml) during the 2 h cytochalasin D treatment and 1 h after the treatment, protein foci were not observed around the dispersed B-bodies (Fig. 3L, arrows). The numbers of developing follicles in just cycloheximide-treated (2 h) ovaries and cytochalasin D plus cycloheximide-treated (2 h) ovaries were comparable to that in control ovaries (Fig. 3M, Supplementary Data 2). Protein foci were not observed around the dispersed B-bodies in control ovaries that were treated with DMSO (solvent of OPP) 0.5–3 h after cytochalasin D removal (Supplementary Fig. 3). In summary, local protein synthesis, which takes place within three hours of B-body disassociation might be involved in primordial follicle activation.

B-body-associated mRNAs identified by DCP1A RNA immunoprecipitation

To identify the RNAs in the B-body, we conducted RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) using the DCP1A300-400 antibody. Specificity of the DCP1A300-400 antibody was validated by immunoblotting of proteins pulled down from primordial follicles by the DCP1A300-400 antibody. A band between 65 and 80 kDa was detected in the pull-down sample, which is consistent with the expected molecular weight of DCP1A protein (~74 kDa) (Fig. 4A and Supplementary Fig. 4). The DCP1A band and RNAs were absent in the sample pulled down using rabbit IgG (Fig. 4A, Supplementary Fig. 5). RNA sequencing result showed that 597 mRNAs were significantly enriched in DCP1A pull-down RNA samples and thus were abundant in the B-body. 246 mRNAs were enriched in the cytoplasm compared to the pull-down RNAs (Fig. 4B, Supplementary Data 3). To validate the sequencing result we conducted in situ hybridization of DCP1A-associated mRNAs together with antibody staining of DCP1A or GM130 on P4 ovarian sections. We found that microRNAs mir331 and mir200c positive puncta co-localized with the circular-shaped DCP1A in the B-body. mRNAs of Plxna3, Pglyrp1 and Osgin1 showed distinct puncta at the perinuclear region of the primary oocyte and co-localized with the B-body labeled by GM130 antibody staining. No positive puncta were observed on the sections blotted with the negative control probe DapB (Fig. 4C, Supplementary Fig. 6). Taken together, these results demonstrated that the mouse B-body stores RNAs possibly through DCP1A.

A Western blot image showing proteins pulled down by the DCP1A300-400 antibody. Rabbit (Rb) IgG was used as the negative control. IgG heavy chain (~50 kDa) was detected in both antibody pull-down (PD) samples. DCP1A protein (~74 kDa) was detected in primordial follicle protein lysis (input), Rb IgG unbounded (UB) sample and DCP1A pull-down sample. B Volcano plot showing enriched mRNAs in the DCP1A pull-down sample or in the cytoplasm. C In situ hybridization images showing the expression and location of RNAs that are highly enriched in DCP1A pull-down mRNAs. The probe to DapB was used as the negative control. (n = 60 oocytes). D Protein expression (normalized spectral count) of DCP1A pull-down mRNAs and cytoplasm-enriched mRNAs in quiescent primordial follicles (QF) and developing follicles (DF). E, F Gene ontology analysis results showing the top 10 candidates of the molecular function (E), biological process (F), REACTOM (G) of DCP1A pull-down mRNAs. The RNA-IP and in situ hybridization were repeated three times independently.

We further compared the protein expression of DCP1A-associated mRNAs between primordial and developing follicles, and found that the majority (451 out of 597, 75.5%) of the proteins encoded by these mRNAs were absent in quiescent primordial follicles, as well as in developing follicles (432 out of 597, 72.3%) (Fig. 4D, Supplementary Data 1). This result indicates that B-body-associated mRNAs may be translated transiently after B-body disassociation, consistent with our observation of nascent protein synthesis upon B-body disassociation (Fig. 3G–I). Gene ontology analysis revealed that the most represented molecular function (16 in total), biological process (56 in total) and REACTOM (61 in total) of these mRNAs were enzyme binding, cellular component organization and packaging of telomere ends (Fig. 4E–G). Collectively, this result suggests the initial cellular and molecular processes taking place upon B-body disassociation that may facilitate primordial follicle activation.

B-body may function downstream of FOXO3a-mediated primordial follicle activation

FOXO3a is one of the main downstream factors of PI3K-dependent primordial follicle activation. FOXO3a is enriched in the nucleus of the quiescent primary oocyte. In the oocyte of the developing follicle, FOXO3a is hyperphosphorylated and exported from the nucleus to the cytoplasm6,8. To address how B-body integrity is associated with FOXO3a-mediated primordial follicle activation, we first examined B-body integrity and FOXO3a location in primary oocytes of P4 ovaries. We found that majority of the primary oocytes were FOXO3a nucleus positive (FOXO NU + ) and contained a B-body, indicating their quiescent state (Fig. 5A, F, Supplementary Data 2). All oocytes in developing follicles (primary and beyond) of P4 ovaries and inhibitor treated-ovaries were FOXO3a nucleus negative (FOXO NU-; Fig. 5A, G–I, white arrows). In P4 ovaries, disassociated B-bodies (yellow arrows) were found in FOXO NU- (white arrows in Fig. 5B–D) and FOXO NU+ primary oocytes (Fig. 5C). Similarly, intact B-bodies (yellow arrowheads) were found in FOXO NU- (Fig. 5D) and FOXO NU+ primary oocytes (Fig. 5E). Further quantification revealed that among the primary oocytes with a B-body 79.4% were FOXO NU + ; and among the primary oocytes without a B-body 63.4% were FOXO NU+ (Fig. 5F, F’, Supplementary Data 2).

A–E The expression and distribution of FOXO3a in primary oocytes in P4 ovaries. White arrows indicate developing oocytes (A) and primary oocytes (in B–E) with FOXO3a nucleus negative staining. (F, F’) Percentages of primary oocytes with (w) or without (w/o) a B-body that were FOXO3a nucleus positive (FOXO NU + ) or negative (FOXO NU-). G–I The expression and distribution of FOXO3a in control, cytochalasin D-, and bpV(pic)-treated ovaries. J, J’ Percentages of primary oocytes with a B-body that were FOXO NU + or FOXO NU- in cultured ovaries. K, K’ Percentages of primary oocytes without a B-body that were FOXO NU + or FOXO NU- in cultured ovaries. F’, J’, K’ show the individual data points for the same data as in (F, J, K). The numbers in (F, J, K) represent the percentages of FOXO NU+ primary oocytes. L The proposed model of primary oocyte quiescence and activation regulated by B-body-mediated RNA storage. Quantification results were analyzed statistically by using unpaired t-test and shown as Mean ± SD, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant *.

In the ovaries treated with cytochalasin D for 2 h, the percentage of primary oocytes containing a B-body decreased to 44.4%. Among those, 69.0% were FOXO NU+ (Fig. 5J, J’, Supplementary Data 2). Similarly, among the primary oocytes without a B-body 73.4% were FOXO NU+ (Fig. 5K, K’, Supplementary Data 2). Percentages of FOXO NU+ primary oocytes remained comparable (69-78%) in cultured control ovaries, as well as the ovaries 2 h and 24 h after cytochalasin D treatment (Fig. 5J, K, Supplementary Data 2). These results indicate that altered B-body integrity did not change FOXO3a phosphorylation and nuclear exportation. By contrast, when we promoted FOXO3a phosphorylation by treating the ovaries with the PTEN inhibitor bpV(pic) (100 μM) for 2 h, only 1.9% of the primary oocytes remained FOXO NU + , and the percentage of primary oocytes containing a B-body decreased to 18.8%. Among those, only 13% were FOXO NU+ (Fig. 5I, J, Supplementary Data 2), indicating B-body disassociation upon PTEN inhibition and FOXO3a phosphorylation. These results suggest that the B-body might function downstream of FOXO3a-mediated primordial follicle activation (Fig. 5L).

Discussion

In mammals, primordial follicles form in fetal and neonatal ovaries and become dormant following formation. Similar to quiescent somatic cells, quiescent primary oocytes in primordial follicles not only arrest in the cell cycle (meiotic prophase I) in a reversible manner, but also arrest in cell growth57. Among a large pool of primordial follicles in the adult ovary, how a certain number of primordial follicles are activated periodically for development remains an open question.

Here, we show that the mouse B-body is involved in regulating primary oocyte quiescence via RNA storage possibly by using DCP1A. In somatic cells, mRNA decapping is a process that cleaves the 5’ cap structure, which allows mRNA decay in processing bodies and stress granules58,59. In the germline, DCP1A is involved in RNA storage and transportation in Drosophila oogenesis and mouse spermatogenesis21,60,61. The mouse DCP1A protein has three identified isoforms (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein). In our study, only the antibody targeting DCPA1300-400 detected DCP1A that is specifically localized inside the B-body along the cis-Golgi in the primary oocyte, while others stained small foci both in primary oocytes and surrounding somatic follicle cells. A similar pattern of DCP1A distribution in mouse primary oocytes was also reported in a previous study46. Whether mouse oocytes contain a germline-specific isoform of DCP1A protein is an intriguing open question. Our study also found that the mRNA-capping enzyme was enclosed in a cluster within the B-body in quiescent primary oocytes. In the activated oocyte with a disassociated B-body, mRNA-capping enzyme was no longer in a cluster, instead it became in close association with DCP1A on the cis-Golgi (Supplementary Fig. 7, Fig. 5L), suggesting that 5′-cap modification-related mechanism might be used in mice for mRNA storage and translational regulation. In hepatitis B virus and in erythroid cells of a beta-thalassemic mouse model, the mRNA re-capping mechanism is used for translational regulation62. Future studies using advanced sequencing techniques to reveal the dynamics of 5′ cap of DCP1A-associated mRNAs are needed to uncover the molecular mechanisms of RNA storage and translational regulation in the mouse B-body.

We found that 579 mRNAs were associated with DCP1A in the mouse B-body. Nascent protein synthesis found only around disassociated B-bodies suggests that these RNAs are translated upon B-body disperses. Gene ontology analysis of these RNAs indicates the initial biological processes that may be responsible for primordial follicle activation, including substantial kinase binding, and organelle and chromatin organization, which may prepare quiescent primary oocytes for future exponential growth involving large scale transcription and translation activities. Telomere and DNA repair were identified by the REACTOM analysis, indicating that B-body-associated RNAs may function to ensure DNA integrity of oocytes undergoing development. This result raises a question of oocyte fate with unrepaired DNA damage. In mice and humans, chemotherapy drugs and radiation deplete primordial follicles via causing DNA damage and primordial follicle overactivation63. The follicle loss was alleviated when primordial follicle activation was repressed, or DNA damage check point was voided64,65,66. Important additional questions, including whether DCP1A depletion causes defects in B-body RNA storage and primary oocyte quiescence, and whether other RNA binding proteins are involved in RNA storage in the B-body should be carefully addressed in our future study.

We showed that B-body integrity, maintained by actin and microtubules, is involved in primordial follicle quiescence. In Drosophila, zebrafish and Xenopus, microtubules and actin are involved in organizing mitochondria and localizing mRNAs in the B-body15,21. In zebrafish, the microtubule actin crosslinking factor (MACF1) plays an essential role in B-body disassembly67,68. Interestingly, MACF1 was detected in both primordial follicles and developing follicles in the present study, while its function in oocyte development remains uncovered. We demonstrated that depolymerization of actin and microtubules led to B-body disassociation and primordial follicle activation. This result coincides with previous findings on the role of mechanical stress and actin dynamics in primordial follicle activation in mice and humans. The concept of altering mechanical stress for primordial follicle activation was used in fertility treatment in women with a low ovarian reserve and poor ovarian response4,7,69. Similarly, inhibition of PTEN signaling effectively activates quiescent primordial follicles in mouse, swine and human ovarian tissues, suggesting that the mechanisms underlying primordial follicle quiescence may be highly conserved in mammals3,4,5,70,71. In the present study, we showed that inhibition of PTEN activity disrupted B-body integrity, but B-body disassociation did not cause FOXO3a nuclear export. This indicates that B-body may function downstream of the FOXO3a phosphorylation-mediated primordial follicle activation. Because PTEN pathway is involved in many cellular processes in the cell, exact interactions between the B-body and FOXO3a-mediated primordial follicle activation should be carefully investigated in future study using mutant mouse models.

Although B-body disassociation observed in the present study poses a similar potential approach to active primordial follicles to improve fertility outcomes, whether or not activated follicles via B-body disassociation have normal abilities to complete follicle development and support oocyte maturation needs to be carefully addressed in our future study. It was reported that human secondary follicles activated by using the PTEN inhibitor, bpv(HOpic), had significantly compromised follicle growth compared with those from control culture72.

The human B-body was identified as an aggregate of organelles, including centrosomes, Golgi complexes, and mitochondria next to the nucleus in quiescent primary oocytes24. How organelles are organized in the human B-body, and whether the human B-body also serves the function of RNA storage to maintain primary oocyte quiescence will be explored in our future study. In summary, the present study characterized molecular content and a novel role of the mouse B-body in regulating primary oocytes quiescence via RNA storage. Our findings shed light on how primordial follicles, an extremely long-lived cellular complex, are maintained for years to decades in mammals.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Female and male CD-1 mice (6 weeks old) were acquired from Charles River Laboratories and housed at 1:1 ratio for experimental breeding. All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care & Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of Missouri (protocol number: 36647), the University of Michigan (PRO00008693), and the Buck Institute for Research on Aging (A10239). The experiments were conducted in accordance with the Guides for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the University of Missouri, the University of Michigan, and the Buck Institute. We have complied with all relevant ethical regulations for animal use.

Ovarian tissue processing, antibody immunostaining and oocyte quantification

For B-body characterization, postnatal day 4 (P4) ovaries were dissected in cold phosphate buffer saline (PBS), whole mount antibody staining was done in the following two approaches for better antibody penetration: 1) ovarian tissues were disassociated into cell clusters by incubating with trypsin (0.25%) for 3 mins at room temperature. The cell clusters were embedded in Smear Gell (Diagnocine LLC) on chambered slides to maintain 3-D structure of the cells. The cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) at room temperature for 15 minutes, and washed in PBST2 (PBS with 0.1% Tween 20 and 0.5% Triton X-100). 2) P4 ovaries were fixed in 4% PFA at 4 °C for 2 h, the ovaries were washed and dissected into small pieces in PBST2. Ovarian tissues were incubated with primary antibodies that have been validated for immunofluorescence staining by the vendors (Supplementary Table 3) at 4 °C overnight. For negative controls, ovarian tissues were also incubated with normal rabbit or mouse IgG isotypes at the same dilution as the primary antibodies (Supplementary Fig. 8). The next day, tissues were washed in PBST2 and incubated with secondary antibodies at 4°C overnight. Tissues were washed in PBST2 and incubated with DAPI at room temperature for 30 min to stain nuclei. The tissues were then mounted on slides and imaged using confocal microscopy. Minimum n = 20 oocytes of each staining from three independent staining experiments were examined to ensure the consistency of staining results. Fiji image analysis software was used to measure the fluorescence intensity of antibody staining inside and outside of the B-body on series confocal images. The optical section of the biggest cross-section of the B-body (spherical GM130 staining) was used for the measurement by following the protocol (https://theolb.readthedocs.io/en/latest/imaging/measuring-cell-fluorescence-using-imagej.html). For each measurement, a fixed area was selected to read the integrated density of both inside and outside of the B-body.

For oocyte quantification in the ovaries after a 6-day culture, whole ovaries were fixed in 4% PFA at 4 °C overnight. Tissues were stained with an anti-VASA (MVH) antibody to reveal oocytes. The stained tissues were mounted on glass microscope slides using imaging spacers and imaged using confocal microscopy at 10 μm per scan. Developing follicles were recognized by containing VASA positive oocytes that were bigger than 25 μm in diameter and surrounded by cuboidal granulosa cells. Using Fiji image analysis software, developing follicles in the whole ovary were counted. For ovaries of P10 mice treated with inhibitors at P4, whole ovaries were fixed in 4% PFA at 4 °C overnight. Tissues were washed with PBS and incubated with 30% sucrose overnight before being embedded in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound. Serial sections of the entire ovary were cut at 10 μm and stained with an anti-VASA (MVH) antibody. Developing follicles were counted at every 5th section. The number of developing follicles per ovary was calculated as follows: number of developing follicles per ovary = average developing follicles per section X number of sections of the ovary. Developing follicle counts were statistically analyzed using one-way ANOVA. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Electron microscopy

Electron microscopic imaging was done by the Microscopy and Image Analysis Laboratory (MIL) at the University of Michigan.

Neonatal ovary culture

P4 ovaries were dissected in sterile cold PBS and cultured in 400 μl culture media (basal media): DMEM-F12 media supplemented with 3 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA), 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 10 mIU/ml follicular stimulating hormone (FSH). Three ovaries were placed on a membrane insert (Millipore) in a well of a 4-well cell culture plate. Initially, ovaries were cultured for 2 h with an inhibitor. After the drug treatment, ovaries were washed with basal media three times then placed onto a new membrane insert containing the basal media. After a 6-day culture, ovaries were fixed in 4% PFA for further analyses. Drugs used in the present study: cytochalasin D (Sigma C8273, 10 μM); nocodazole (Sigma M1404, 10 μM); bpV(pic) (Sigma SML0885, 100 μM), cycloheximide (Sigma 01810, 10 μg/ml). Control ovaries were treated with the same volume of solvent dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO).

Injections to neonatal mice

Drugs were injected into P4 neonatal female mice subcutaneously at the back of the neck. The dosage of the drugs was calculated based on pup’s body weight. Drugs used for injection: cytochalasin D (0.1 μg/g bodyweight); nocodazole (0.1 μg/g bodyweight). Control mice were injected with the same volume of solvent DMSO in PBS.

Nascent protein synthesis analysis

Click-iT® Plus OPP protein synthesis assay kit was used to detect newly synthesized proteins. After a 2 h incubation with cytochalasin D (10 μM), ovaries (three per group) were rinsed and then incubated with cell culture medium. 0.2 mM OPP (1:100 dilution of the original stock) was added to ovaries at the time points of 0.5 h, 1 h, 2 h, and 3 h after removing cytochalasin D. Ovaries were incubated with OPP (O-propargyl-puromycin) for 30 min (or with the same amount of DMSO for the control groups) before being fixed in 4% PFA. Fixed ovaries were processed according to the manufacturer’s protocol to detect newly synthesized protein within the 30 min window of incubation. The ovaries were co-stained with GM130 antibody to visualize the B-body.

Isolation of primordial follicles and early developing follicles

P8 ovaries were used to isolate quiescent primordial follicles and early developing follicles (primary follicles and a few secondary follicles). In brief, ovaries were placed in a culture dish containing cold PBS, and the cortical layer of the ovaries was separated from the medulla region using fine needles under a stereomicroscope. Early developing follicles, recognized by their large oocyte size, were removed from the cortical layer using fine needles. Individual developing follicles without primordial follicles attached were collected. The cortical tissue and developing follicles were collected in separate tubes and cryopreserved for further analysis.

Proteomic analysis

Proteomic analyses were conducted by the Proteomic & Peptide Synthesis Core at the University of Michigan Medical School. Primordial follicles and early developing follicles that were pooled from three independent collections (~20 mice per collection) were submitted to the core. In brief, tissues were homogenized in RIPA buffer. 20 μg of each sample was processed by SDS-PAGE using 10% Bis-Tris NuPAGE gel with MES buffer. The gel was run to approximately 5 cm. The mobility region was excised into 20 equal sized segments and in-gel digestion was performed on each using a robot (ProGest, DigiLab). Half of each gel digest was analyzed by nano LC-MS/MS with a Waters NanoAcquity HPLC system interfaced to a ThermoFisher Q Exactive. Data were searched using a local copy of Mascot with the following parameters: Enzyme: Trypsin/P; Database: SwissProt Mouse (concatenated forward and reverse plus common contaminants); Fixed modifications: Carbamidomethyl (C); Variable modifications: Oxidation (M), Acetyl (N-term), Pyro-Glu (N-term Q), Deamidation (N,Q); Mass values: Monoisotopic; Peptide Mass Tolerance: 10 ppm; Fragment Mass Tolerance: 0.02 Da; Max Missed Cleavages: 2. Mascot DAT files were parsed into Scaffold (Proteome software) for validation, filtering and creating a non-redundant list per sample. Data were filtered using at least 1% protein and peptide FDR and requiring at least two unique peptides per protein.

RNA immunoprecipitation and RNA sequencing

Magna RIPTM RNA-binding protein immunoprecipitation kit (Sigma-Aldrich 17-700) was used to isolate RNAs that bind with DCP1A. In brief, cortical tissues of P8 ovaries containing primordial follicles were digested by trypsin (0.05%) to break the tissue into single-cell suspension. After washing with PBS, cells were spun down by centrifugation and stored in a −80 °C freezer for future analysis. Cells were processed according to the manufacturer’s protocol of the kit. The DCP1A 300-400 antibody (ab47811) was used for DCP1A protein immunoprecipitation, and rabbit IgG was used as the negative control. Protein samples from the immunoprecipitation were run using the 10% NuPAGE Bis-Tris gel and transferred onto a PVDF membrane. The membrane was blotted with the DCP1A antibody (22373-1-AP) to validate the specificity of the immunoprecipitation. Total RNAs (RNAs isolated from cell lysis) and RNAs enriched by the DCP1A300-400 antibody immunoprecipitation were submitted to the Advanced Genomics Core at the University of Michigan Medical School for RNA sequencing. Sequencing libraries were prepared using SMARTer Stranded Total RNA-Seq Kit v2- Pico input Mammalian, and sequenced using HiSeq-4000, paired end 50 bp cycle. Sequencing results were analyzed using Tuxedo/Cuffdiff2 (with DE at gene and isoform level) and conducted by the Bioinformatics Core at the University of Michigan Medical School. Functional annotation of RNA sequencing results was conducted by using g:Profiler: https://biit.cs.ut.ee/gprofiler/gost (Dec, 2019)

mRNA in situ hybridization

To examine the location of mRNAs in primary oocytes, frozen sections of P4 ovaries were collected under RNAase free condition. The in situ was conducted using RNAscope 2.5HD reagent kit (322300) and RNAscope probes for the targeted mRNAs and a negative control probe (Advance Cell Diagnostics). The sections were processed according to the manufacturer’s protocols and counter-stained with hematoxylin to visualize the nuclei.

Statistics and reproducibility

Sample size of the mice used in the present study was determined using power analysis, with a significance threshold of 0.05 and a power level of 80%. Data were analyzed and plotted using Prism 10 (GraphPad Prism 10.1.2). Parametric t-tests were used to examine the difference between two experimental groups. Multiple experimental groups were analyzed using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s tests. All data was presented as mean ± SD. P-value level of at least P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Supplementary Information files. Source data for Figs. 3 and 5 are in Supplementary Data 2. Data from proteomic analysis are included in Supplementary Data 1. Data from RNA immunoprecipitation are included in Supplementary Data 3. Sequencing data from the RNA-seq experiment are available in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository (accession number: GSE276220).

References

Pepling, M. E. Follicular assembly: mechanisms of action. Reproduction 143, 139–149 (2012).

Lintern-Moore, S. & Moore, G. P. The initiation of follicle and oocyte growth in the mouse ovary. Biol. Reprod. 20, 773–778 (1979).

Li, J. et al. Activation of dormant ovarian follicles to generate mature eggs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 10280–10284 (2010).

Kawamura, K. et al. Hippo signaling disruption and Akt stimulation of ovarian follicles for infertility treatment. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 17474–17479 (2013).

Adhikari, D., Risal, S., Liu, K. & Shen, Y. Pharmacological inhibition of mTORC1 prevents over-activation of the primordial follicle pool in response to elevated PI3K signaling. PLoS One 8, e53810 (2013).

John, G. B., Gallardo, T. D., Shirley, L. J. & Castrillon, D. H. Foxo3 is a PI3K-dependent molecular switch controlling the initiation of oocyte growth. Dev. Biol. 321, 197–204 (2008).

Nagamatsu, G., Shimamoto, S., Hamazaki, N., Nishimura, Y. & Hayashi, K. Mechanical stress accompanied with nuclear rotation is involved in the dormant state of mouse oocytes. Sci. Adv. 5, eaav9960 (2019).

John, G. B., Shirley, L. J., Gallardo, T. D. & Castrillon, D. H. Specificity of the requirement for Foxo3 in primordial follicle activation. Reproduction 133, 855–863 (2007).

Castrillon, D. H., Miao, L., Kollipara, R., Horner, J. W. & DePinho, R. A. Suppression of ovarian follicle activation in mice by the transcription factor Foxo3a. Science 301, 215–218 (2003).

Schmidt, D. et al. The murine winged-helix transcription factor Foxl2 is required for granulosa cell differentiation and ovary maintenance. Development 131, 933–942 (2004).

Uda, M. et al. Foxl2 disruption causes mouse ovarian failure by pervasive blockage of follicle development. Hum. Mol. Genet 13, 1171–1181 (2004).

Durlinger, A. L. et al. Anti-Müllerian hormone inhibits initiation of primordial follicle growth in the mouse ovary. Endocrinology 143, 1076–1084 (2002).

Carlsson, I. B. et al. Anti-Müllerian hormone inhibits initiation of growth of human primordial ovarian follicles in vitro. Hum. Reprod. 21, 2223–2227 (2006).

Durlinger, A. L. et al. Control of primordial follicle recruitment by anti-Müllerian hormone in the mouse ovary. Endocrinology 140, 5789–5796 (1999).

Jamieson-Lucy, A. & Mullins, M. C. The vertebrate Balbiani body, germ plasm, and oocyte polarity. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 135, 1–34 (2019).

Kloc, M., Bilinski, S. & Etkin, L. D. The Balbiani body and germ cell determinants: 150 years later. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 59, 1–36 (2004).

FL., M. Oocyte Polarity and the Embryonic Axes: The Balbiani Body, an Ancient Oocyte Asymmetry., (San Rafael (CA): Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences, 2010).

Boke, E. et al. Amyloid-like Self-Assembly of a Cellular Compartment. Cell 166, 637–650 (2016).

Wallace, R. A. & Selman, K. Ultrastructural aspects of oogenesis and oocyte growth in fish and amphibians. J. Electron Microsc Tech. 16, 175–201 (1990).

Cox, R. T. & Spradling, A. C. A Balbiani body and the fusome mediate mitochondrial inheritance during Drosophila oogenesis. Development 130, 1579–1590 (2003).

Voronina, E., Seydoux, G., Sassone-Corsi, P. & Nagamori, I. RNA granules in germ cells. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 3, a002774 (2011).

Amin, R., Bukulmez, O. & Woodruff, J. B. Visualization of Balbiani Body disassembly during human primordial follicle activation. MicroPubl Biol 2023 https://doi.org/10.17912/micropub.biology.000989 (2023).

Pepling, M. E., Wilhelm, J. E., O’Hara, A. L., Gephardt, G. W. & Spradling, A. C. Mouse oocytes within germ cell cysts and primordial follicles contain a Balbiani body. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 187–192 (2007).

Hertig, A. T. The primary human oocyte: some observations on the fine structure of Balbiani’s vitelline body and the origin of the annulate lamellae. Am. J. Anat. 122, 107–137 (1968).

Hertig, A. T. & Adams, E. C. Studies on the human oocyte and its follicle. I. Ultrastructural and histochemical observations on the primordial follicle stage. J. Cell Biol. 34, 647–675 (1967).

Lei, L. & Spradling, A. C. Mouse oocytes differentiate through organelle enrichment from sister cyst germ cells. Science 352, 95–99 (2016).

Pepling, M. E. & Spradling, A. C. Mouse ovarian germ cell cysts undergo programmed breakdown to form primordial follicles. Dev. Biol. 234, 339–351 (2001).

Dhandapani, L. et al. Comparative analysis of vertebrates reveals that mouse primordial oocytes do not contain a Balbiani body. J Cell Sci 135 https://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.259394 (2022).

The Balbiani Body and Germ Cell Determinants: 150 Years Later.

Yadav, S. & Linstedt, A. D. Golgi positioning. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 3, a005322 (2011).

Klumperman, J. Architecture of the mammalian Golgi. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 3, a005181 (2011).

Adam, S. A., Nakagawa, T., Swanson, M. S., Woodruff, T. K. & Dreyfuss, G. mRNA polyadenylate-binding protein: gene isolation and sequencing and identification of a ribonucleoprotein consensus sequence. Mol. Cell. Biol. 6, 2932–2943 (1986).

Burd, C. G., Matunis, E. L. & Dreyfuss, G. The multiple RNA-binding domains of the mRNA poly(A)-binding protein have different RNA-binding activities. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11, 3419–3424 (1991).

Schibler, U. & Perry, R. P. Characterization of the 5′ termini of hn RNA in mouse L cells: implications for processing and cap formation. Cell 9, 121–130 (1976).

Schoenberg, D. R. & Maquat, L. E. Re-capping the message. Trends Biochem Sci. 34, 435–442 (2009).

Grivna, S. T., Pyhtila, B. & Lin, H. MIWI associates with translational machinery and PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) in regulating spermatogenesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 13415–13420 (2006).

Kuramochi-Miyagawa, S. et al. Mili, a mammalian member of piwi family gene, is essential for spermatogenesis. Development 131, 839–849 (2004).

Iwakawa, H. O. & Tomari, Y. Life of RISC: Formation, action, and degradation of RNA-induced silencing complex. Mol. Cell 82, 30–43 (2022).

Ameres, S. L., Hung, J. H., Xu, J., Weng, Z. & Zamore, P. D. Target RNA-directed tailing and trimming purifies the sorting of endo-siRNAs between the two Drosophila Argonaute proteins. Rna 17, 54–63 (2011).

Gray, N. K. & Wickens, M. Control of translation initiation in animals. Annu. Rev. cell developmental Biol. 14, 399–458 (1998).

Eystathioy, T. et al. A phosphorylated cytoplasmic autoantigen, GW182, associates with a unique population of human mRNAs within novel cytoplasmic speckles. Mol. Biol. cell 13, 1338–1351 (2002).

Eystathioy, T. et al. A panel of monoclonal antibodies to cytoplasmic GW bodies and the mRNA binding protein GW182. Hybrid. hybridomics 22, 79–86 (2003).

Ayache, J. et al. P-body assembly requires DDX6 repression complexes rather than decay or Ataxin2/2L complexes. Mol. Biol. Cell 26, 2579–2595 (2015).

Ripin, N., Macedo de Vasconcelos, L., Ugay, D. A. & Parker, R. DDX6 modulates P-body and stress granule assembly, composition, and docking. J Cell Biol 223 https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.202306022 (2024).

Wurm, J. P. & Sprangers, R. Dcp2: an mRNA decapping enzyme that adopts many different shapes and forms. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 59, 115–123 (2019).

Flemr, M., Ma, J., Schultz, R. M. & Svoboda, P. P-body loss is concomitant with formation of a messenger RNA storage domain in mouse oocytes. Biol. Reprod. 82, 1008–1017 (2010).

Williams, C. J. & Erickson, G. D. Morphology and Physiology of the Ovary. [Updated 2012 Jan 30]. In: Feingold, K. R., Anawalt, B., Blackman, M. R. et al. editors. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK278951/ (2000).

Thyberg, J. & Moskalewski, S. Role of microtubules in the organization of the Golgi complex. Exp. cell Res. 246, 263–279 (1999).

Heimann, K., Percival, J. M., Weinberger, R., Gunning, P. & Stow, J. L. Specific isoforms of actin-binding proteins on distinct populations of Golgi-derived vesicles. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 10743–10750 (1999).

Meng, W., Mushika, Y., Ichii, T. & Takeichi, M. Anchorage of microtubule minus ends to adherens junctions regulates epithelial cell-cell contacts. Cell 135, 948–959 (2008).

Berrueta, L. et al. The adenomatous polyposis coli-binding protein EB1 is associated with cytoplasmic and spindle microtubules. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95, 10596–10601 (1998).

Canning, J., Takai, Y. & Tilly, J. L. Evidence for genetic modifiers of ovarian follicular endowment and development from studies of five inbred mouse strains. Endocrinology 144, 9–12 (2003).

Ikami, K. et al. Altered germline cyst formation and oogenesis in Tex14 mutant mice. Biol. Open 10, bio058807 (2021).

Picton, H. M. Activation of follicle development: the primordial follicle. Theriogenology 55, 1193–1210 (2001).

Liu, J., Xu, Y., Stoleru, D. & Salic, A. Imaging protein synthesis in cells and tissues with an alkyne analog of puromycin. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 413–418 (2012).

Enam, S. U. et al. Puromycin reactivity does not accurately localize translation at the subcellular level. Elife 9, e60303 (2020).

Cheung, T. H. & Rando, T. A. Molecular regulation of stem cell quiescence. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 14, 329–340 (2013).

Sheth, U. & Parker, R. Decapping and decay of messenger RNA occur in cytoplasmic processing bodies. Science 300, 805–808 (2003).

Balagopal, V. & Parker, R. Polysomes, P bodies and stress granules: states and fates of eukaryotic mRNAs. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 21, 403–408 (2009).

Lin, M. D., Fan, S. J., Hsu, W. S. & Chou, T. B. Drosophila decapping protein 1, dDcp1, is a component of the oskar mRNP complex and directs its posterior localization in the oocyte. Dev. Cell 10, 601–613 (2006).

Kotaja, N. et al. The chromatoid body of male germ cells: similarity with processing bodies and presence of Dicer and microRNA pathway components. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 2647–2652 (2006).

Trotman, J. B. & Schoenberg, D. R. A recap of RNA recapping. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 10, e1504 (2019).

Kim, S. Y., Cho, G. J. & Davis, J. S. Consequences of chemotherapeutic agents on primordial follicles and future clinical applications. Obstet. Gynecol. Sci. 62, 382–390 (2019).

Kano, M. et al. AMH/MIS as a contraceptive that protects the ovarian reserve during chemotherapy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, E1688–E1697 (2017).

Goldman, K. N. et al. mTORC1/2 inhibition preserves ovarian function and fertility during genotoxic chemotherapy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 3186–3191 (2017).

Bolcun-Filas, E., Rinaldi, V. D., White, M. E. & Schimenti, J. C. Reversal of female infertility by Chk2 ablation reveals the oocyte DNA damage checkpoint pathway. Science 343, 533–536 (2014).

Escobar-Aguirre, M., Zhang, H., Jamieson-Lucy, A. & Mullins, M. C. Microtubule-actin crosslinking factor 1 (Macf1) domain function in Balbiani body dissociation and nuclear positioning. PLoS Genet 13, e1006983 (2017).

Gupta, T. et al. Microtubule actin crosslinking factor 1 regulates the Balbiani body and animal-vegetal polarity of the zebrafish oocyte. PLoS Genet 6, e1001073 (2010).

Kawamura, K., Ishizuka, B. & Hsueh, A. J. W. Drug-free in-vitro activation of follicles for infertility treatment in poor ovarian response patients with decreased ovarian reserve. Reprod. Biomed. Online 40, 245–253 (2020).

Adhikari, D. et al. The safe use of a PTEN inhibitor for the activation of dormant mouse primordial follicles and generation of fertilizable eggs. PLoS One 7, e39034 (2012).

Raffel, N. et al. The effect of bpV(HOpic) on in vitro activation of primordial follicles in cultured swine ovarian cortical strips. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 54, 1057–1063 (2019).

McLaughlin, M., Kinnell, H. L., Anderson, R. A. & Telfer, E. E. Inhibition of phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN) in human ovary in vitro results in increased activation of primordial follicles but compromises development of growing follicles. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 20, 736–744 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R01GM126028), Howard and Georgeanna Johns Foundation for Reproductive Medicine, the University of Michigan startup fund, and the University of Missouri startup fund. K.I. is a recipient of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Oversea Research Fellowship. E.A.D.M was supported by the Lalor Foundation. S.J. was supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R56HD104821).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.L. designed and conducted experiments, analyzed data, prepared Figs. 1–5, and wrote the main manuscript text. K.I. conducted experiments and analyzed data. E.A.D.M. conducted experiments, analyzed data, prepared supplementary files, and wrote the main manuscript text. S.K. conducted experiments. F.W. conducted experiments and wrote the main manuscript text. H.A. conducted experiments. R.P. conducted experiments. S.J. conducted experiments.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Haiyang Wang and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Jun Wei Pek and Manuel Breuer. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lei, L., Ikami, K., Diaz Miranda, E.A. et al. The mouse Balbiani body regulates primary oocyte quiescence via RNA storage. Commun Biol 7, 1247 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-024-06900-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-024-06900-4

This article is cited by

-

Biomolecular condensates: molecular structure, biological functions, diseases, and therapeutic targets

Molecular Biomedicine (2025)