Abstract

While anatomical white matter (WM) alterations in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) are well-established, functional WM dysregulation remains rarely investigated. The current study examines WM functional connectivity and network properties alterations in AD and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and further describes their spatially correlated genes. AD and MCI shared decreased functional connectivity, clustering coefficient, and local efficiency within WM regions involved in impaired sensory-motor, visual-spatial, language, or memory functions. AD-specific dysfunction (i.e., AD vs. MCI and cognitively unimpaired participants) was predominantly located in WM, including anterior and posterior limb of internal capsule, corona radiata, and left tapetum. This WM dysfunction spatially correlates with specific genes, which are enriched in multiple biological processes related to synaptic function and development, and are mostly active in neurons and astrocytes. These findings may contribute to understanding molecular, cellular, and functional signatures associated with WM damage in AD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia, and is confirmed by detecting amyloid-β and tau deposits accumulation1,2. As the spatial patterns of amyloid-β/tau overlap with anatomical3 and functional networks4, existing models of AD neurobiology have hypothesized the active role of brain connectomes in the spread of pathology5,6. Previously, numerous neuroimaging studies explored the functional connectomics in AD within gray matter (GM)5,7. Although GM regions directly connected by white matter (WM) fiber bundles always show high functional connectivity (FC), the dysfunction within WM has often been ignored.

Recently, several studies have clarified that the blood-oxygen-level-dependent signals in WM can reflect the intrinsic neural activities in the human brain8,9,10. Specifically, the power spectra distributions of functional signals in WM are repeatable and highly consistent with the anatomical configurations11. Using independent component analysis, symmetrical WM functional organizations have been found to overlap spatially with WM anatomical structures12. Combining intracranial stereotactic-electroencephalography and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), Huang and colleagues showed the electrophysiological basis underlying FC in WM9. For the macro-scale organization, WM exhibited functional modules similar to GM13,14,15. At the molecular genetic level, the common pattern of WM dysfunction in major psychiatric disorders was correlated with synaptic function and excitatory neurons10. Although various studies have implicated the significance of WM degeneration, demyelination, and hyperintensities in AD pathology16,17, few have explored the potential role of WM dysfunction in AD18. Detailed characterizations of WM functional features would provide a comprehensive understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms of AD.

As an effective method to capture the topological features of functional brain networks, graph theoretical analysis can describe global and local topological patterns of activity in the human brain19. Assortativity, a global topological metric, measures resilience, with a larger value indicating a more robust network. Other nodal metrics, such as clustering coefficient and local efficiency, have proven to be effective in identifying AD with electroencephalograph functional networks20 and have described key features of WM functional network disorganization in neuropsychiatric disorders such as major depression21 and schizophrenia22.

The disrupted brain functions in AD are reflected in the macroscopic network configuration patterns and are inextricably linked to the disease’s molecular genetic etiology23,24. Genetic etiology affects the structural and functional attributes of the human brain25,26 and is associated with the risk of developing AD24. For example, APOEε4 carriers with amnestic mild cognitive impairment (amnestic MCI) showed decreased FC in WM regions27. AD’s abnormal structural connectome changes were linked with synaptic-related biological processes and neuronal cells28. Moreover, neurotransmitters and gene expression profiles relating to WM dysfunction in multiple psychiatric disorders have been reported10. Therefore, identifying the genetic influences underlying the variation in WM functional connectome is crucial for further clarifying the multiscale pathological processes in AD.

Here, we hypothesize that the macroscopic WM functional changes in AD align spatially with distinctive microstructural gene transcriptional signatures in the neurotypical adult brain. We first characterized the diagnosis-specific patterns of WM functional changes by measuring the FC, topological properties, and regional functional connectivity strength (RFCS) among clinical AD, MCI, and cognitively unimpaired (CU) participants. We observed that AD-specific dysfunctional connections were mainly distributed in WM regions. Next, we identified a significant spatial relationship between gene expression and regional WM dysfunction using the Allen Human Brain Atlas (AHBA)29 and partial least squares (PLS) regression. The associated gene sets were submitted to the enrichment analysis to provide preliminary transcriptional correlates of RFCS. Finally, we found that the spatial distributions of neurons and astrocytes overlapped with WM functional disconnection. These results shed light on the connection between transcriptional and cellular information and WM dysfunction in AD.

Results

Overall approach

The current study employed 53 individuals with mild AD, 90 individuals with MCI, and 100 matched CU individuals as a discovery dataset shared from the Open Access Series of Imaging Studies (OASIS-3, https://www.oasis-brains.org/)30. We also included 38 individuals with AD, 65 individuals with MCI, and 72 matched CU individuals shared from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) as the validation dataset. No significant group differences were found in age, sex, or education (P > 0.05, Supplementary Tables S1 and S21). Age, sex, and education were all regressed as covariates in all statistical analyses. Results in the main text are primarily reported from the discovery dataset unless explicitly stated as validation findings.

The data analysis procedure consisted of five main parts (Fig. 1). (a) Preprocessing of 243 participants’ fMRI data from OASIS-3. (b) Characterizing the diagnosis-specific FC and (c) topological properties on GM-, WM-, and whole-brain functional networks separately. (d) Calculating the group differences in RFCS. (e) Utilizing PLS regression to model the spatial relationship between the brain changes among clinical groups and transcriptional profiles, performing functional enrichment analysis on the first component of PLS (PLS1) gene sets, and assigning the PLS1 gene sets into different cell types. All main analyses were repeated in the validation dataset.

a Obtain fMRI data for 243 participants from the OASIS-3 dataset. b Perform functional connectivity (FC) analysis on the GM, WM, and whole brain. c Perform graph theory analysis on the functional networks of GM, WM, and whole brain separately. d Average all the FC connected to each given brain region to get regional FC strength (RFCS) and conduct the Kruskal–Wallis test on RFCS of GM or WM regions among CU, MCI, and AD groups. e First, partial least squares (PLS) regression was utilized to model the relationship between the brain changes among clinical groups and transcriptional profile. Next, the gene sets filtered according to the score of the first component of PLS (PLS1) (Z > |3|) were submitted to enrichment analysis on Metascape. The enriched gene ontology biological processes were overlapped with genome-wide meta-analysis studies (GWAS). Finally, the PLS1 gene sets were sorted into different cell types.

Altered functional connectivity in the whole brain

We first obtained 45 WM regions of interest (ROIs) and 96 GM ROIs by point-multiplying the JHU ICBM-DTI-81 WM atlas31 and the group-level WM mask, the Harvard-Oxford cortical atlas32 and group-level GM mask, respectively (see Methods, subsection Obtaining the group-level WM and GM masks). Next, we construct the FC matrices of 141 × 141 (i.e., 45 + 96) for the whole brain by performing Pearson correlation between time series of ROI-pairs for each individual. For details on all ROIs, see Supplementary Tables S3–S5.

Compared to CU, both AD and MCI showed decreased FC within WM between the left anterior (ALIC) and the right posterior limb of internal capsule (PLIC) (all t < −2.525, PFDR < 0.020), and two increased FC between GM and WM (i.e., between the right angular gyrus and right posterior thalamic radiation, all t > 3.104, PFDR = 0.004; between the left angular gyrus and left tapetum, all t > 3.497, PFDR < 0.002). Moreover, we also observed decreased FC within GM involving superior parietal lobule, postcentral gyrus, fusiform cortex, and occipital cortex (all t < −2.505, PFDR < 0.020) (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Table S6).

a From left to right: statistical values of FC, including H values from the Kruskal–Wallis test among three groups, and t values from two-sample T-tests between the MCI and CU, AD and CU, and AD and MCI groups. The color bars indicate the H or t values. The upper triangle of the matrix labels the connections with statistically significant differences by permutation test (10,000 times). FDR correction was used for multiple comparisons with P < 0.05. b Visualization of FC with significant correlation to MMSE. The P values of correlation coefficients were uncorrected. FC functional connectivity, AD Alzheimer’s disease, MCI mild cognitive impairment, CU cognitively unimpaired, MMSE Mini-Mental State Examination.

Compared with CU and MCI groups, AD-specific FC decreased within WM regions involving the ALIC, PLIC, the anterior/posterior corona radiata, the splenium of corpus callosum, the posterior thalamic radiation, and left tapetum (all t < −2.763, PFDR < 0.011), but enhanced between WM and GM (i.e., between right pre/postcentral gyrus and left ALIC, between right inferior frontal gyrus and left superior fronto-occipital fasciculus; all t > 2.382, PFDR < 0.028). However, no significant MCI-specific FC was found (i.e., in any ROI-pair, for comparison of FC between MCI vs. CU or MCI vs. AD, at least one PFDR > 0.050) (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Table S6).

As shown in Fig. 2a, we can observe three patterns: first, the regions showing FC differences between MCI and CU were all detected in the comparison between AD and CU; second, the extra changes in AD versus MCI were mainly related to WM; and third, the patients’ groups (i.e., MCI and AD) showed weakened intra-WM or intra-GM FC but enhanced inter-WM-GM FC. Moreover, we performed a robust modified Spearman correlation between the FC and clinical score of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE). We observed that both the FC between the left PLIC and the splenium of corpus callosum (Spearman’s r = 0.32, uncorrected P = 0.043) and between the right PLIC and left posterior corona radiata (Spearman’s r = 0.33, uncorrected P = 0.048) showed moderate positive correlations with MMSE of the AD group (Fig. 2b).

Global topological properties

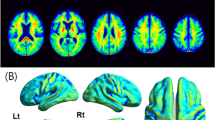

WM and GM ROIs are shown in Fig. 3a, b. The statistical results of global topological metrics were displayed in Fig. 3c. Compared with the CU group, both MCI and AD groups showed significantly decreased clustering coefficient in the GM network (MCI: PFDR = 0.0347, AD: PFDR = 0.0347) and the whole-brain network (MCI: PFDR = 0.0481, AD: PFDR = 0.0402). Additionally, the AD group exhibited decreased clustering coefficient in the WM network (PFDR = 0.0302) and reduced assortativity in the GM network (PFDR = 0.0447) compared to the CU group. No significant difference was observed for assortativity in the WM network (PFDR = 0.270) or the whole-brain network (PFDR = 0.2057).

a, b The ROI distribution of WM and GM, respectively. c Group differences in the global topological properties of WM, GM, and whole-brain functional networks. Box plots show the area under the curve (AUC) value of the topological metric for each group. Boxes denote the 25th to 75th centiles and the median line. The whiskers extend from the 5th to the 95th centiles, and data points beyond the whiskers are displayed as outliers. An asterisk indicates significant differences. The nodal topological properties differences in WM (d) and GM (e) among AD, MCI, and CU (left column), between AD and CU (second column), between MCI and CU (third column), and between AD and MCI (right column). Region colors indicate the positive (red) or negative (blue) statistical value. FDR correction was used for multiple comparisons with P < 0.05. GM gray matter, WM white matter, AD Alzheimer’s disease, MCI mild cognitive impairment, CU cognitively unimpaired.

Nodal topological organization

Analysis on graph metrics of WM ROIs revealed that both nodal clustering coefficient within 11 ROIs (all H > 8.842, PFDR < 0.0492) and nodal local efficiency within 9 ROIs (all H > 9.702, PFDR < 0.0391) exhibited significant group effects (Fig. 3d). Post hoc analysis on nodal clustering coefficient (Fig. 3d, the top two rows) revealed significantly lower values in both AD and MCI groups than CU group within the left corticospinal tract, the bilateral sagittal stratum, the left superior fronto-occipital fasciculus, and the bilateral uncinate fasciculus (all Z < −2.369, PFDR < 0.031). Compared with CU and MCI groups, the AD-specific clustering coefficient was reduced in the bilateral superior corona radiata and the posterior thalamic radiation (all Z < −2.263, PFDR < 0.0390). Moreover, in the right ALIC and left tapetum, only the clustering coefficient in AD was significantly lower than that in CU (all Z < −3.215, PFDR < 0.008). No significant MCI-specific clustering coefficient was found (i.e., in any ROI, for comparison of clustering coefficient between MCI vs. CU or MCI vs.AD, at least one PFDR > 0.050). More details are shown in Supplementary Table S7.

Post hoc analysis on local efficiency of WM ROIs (Fig. 3d, the bottom two rows) indicated that the values in both AD and MCI groups were significantly lower than those in the CU group within the left corticospinal tract, the bilateral sagittal stratum, and the bilateral uncinate fasciculus (all Z < −2.136, PFDR < 0.050). AD-specific local efficiency was smaller within the bilateral superior corona radiata, the posterior thalamic radiation, and the left tapetum (all Z < −2.130, PFDR < 0.050). No significant MCI-specific local efficiency was found (i.e., in any ROI, for comparison of local efficiency between MCI vs. CU or MCI vs.AD, at least one PFDR > 0.050). More details are shown in Supplementary Table S8.

For GM, results of nodal clustering coefficient showed significant differences among AD, MCI, and CU (all H > 10.73, PFDR < 0.050; Fig. 3e). Compared to CU, both AD and MCI groups had reduced clustering coefficient in the somatomotor network and visual network (all Z < −2.239, PFDR < 0.044). Additionally, the AD group showed a reduced clustering coefficient than CU in the dorsal attention network (all Z < −3.345, PFDR < 0.005). Nevertheless, the differences between the nodal clustering coefficient of the MCI and AD group (all Z > −1.703, PFDR > 0.126) were not significant after multiple comparison correction, nor were the differences among the nodal local efficiency of AD, MCI, and CU (all H < 12.922, PFDR > 0.1500). More details are shown in Supplementary Table S9.

Differences in regional functional connectivity strength

Results from WM ROIs (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Table S10) indicated that AD and MCI exhibited significantly lower RFCS than the CU group in the right superior corona radiata (all Z < −2.350, PFDR < 0.033). Compared to MCI and CU, AD-specific RFCS was significantly reduced in many regions, including the splenium of corpus callosum, the bilateral PLIC, the anterior and left posterior corona radiata, the right external capsule, and left tapetum (all Z < −2.268, PFDR < 0.039). However, no significant MCI-specific WM RFCS was found (i.e., in any ROI, for comparison of RFCS between MCI vs. CU or MCI vs.AD, at least one PFDR > 0.050). The Spearman’s rank correlation showed a moderate correlation between the WM RFCS and MMSE in the splenium of the corpus callosum (Spearman’s r = 0.33, uncorrected P = 0.011; Supplementary Fig. S1) in the AD group.

a, b The altered RFCS among the three groups and the results of post hoc analysis within WM and GM, respectively. Regional colors indicate the positive (red) or negative (blue) statistical value. FDR correction was used for multiple comparisons with P < 0.05. c The first component (PLS1) for predicting WM RFCS explained 65.72% of the variance (permutation test, 10,000 times, P = 0.0022). d Strong spatial correlation between the group difference in WM RFCS and PLS1 score (Spearman’s r = 0.8107, P < 0.001). RFCS regional functional connectivity strength; GM gray matter; WM white matter; AD Alzheimer’s disease; MCI mild cognitive impairment; CU cognitively unimpaired.

Findings from GM ROIs (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Table S11) revealed that both AD and MCI showed decreased RFCS than CU within the somatomotor, the dorsal and ventral attention, the default mode, and the visual networks (all Z < −2.490, PFDR < 0.026). Furthermore, AD showed an additional reduction in RFCS than CU within the limbic network (all Z < −3.253, PFDR < 0.005). MCI individuals showed an additional decrease in RFCS than CU in the right cingulate gyrus (Z = −3.270, PFDR = 0.005). Compared to CU and MCI groups, the AD-specific RFCS was found to be decreased in the right parahippocampal gyrus and the bilateral temporal occipital fusiform cortex, which were distributed in the limbic and visual networks (all Z < −2.255, PFDR < 0.045). No significant MCI-specific GM RFCS was found (i.e., in any ROI, for comparison of RFCS between MCI vs. CU or MCI vs.AD, at least one PFDR > 0.050).

Functional disconnection correlates with gene expression level

We estimated the gene expression matrices using the abagen toolbox33 on the AHBA dataset (http://human.brain-map.org, see Supplementary Information 2 for details). Due to the incomplete right hemispheres in the AHBA dataset (Supplementary Table S2), we focus our analysis on 48 GM ROIs and 21 WM ROIs in the left hemisphere. A 48 × 15,633 transcriptional level matrix of GM ROIs and a 21 × 15,632 transcriptional level matrix of WM ROIs were obtained (see Supplementary Information 3 for reports on obtaining gene expression matrices) and retained for subsequent analysis. We conducted a PLS regression34 to characterize the relationship between the RFCS and the gene transcriptional profiles for WM and GM separately. The first component of PLS (PLS1) for predicting WM RFCS explained 65.72% of the variance (permutation test, 5000 times, P = 0.0022, Fig. 4c), while for predicting GM RFCS explained 30.34% of its variance (permutation test, 5000 times, P = 0.1815). Accordingly, because the percentage of variance explained for GM RFCS did not reach a significant level, only the PLS regression results relating to the WM RFCS were considered for further analysis. Comparative analysis results using both GM and WM were discussed in Supplementary Information 8.

We found a strong spatial correlation between the group difference in WM RFCS and PLS1 score (Spearman’s r = 0.8107, P < 0.001; Fig. 4d). Particularly, in the anterior/superior/anterior corona radiata, the tapetum, and the ALIC, both the PLS1 score and the group difference of WM RFCS were high. However, in regions including the corticospinal tract, the inferior cerebellar peduncle, the medial lemniscus, and the cingulum in the cingulate cortex, the PLS1 score and the group difference in WM RFCS showed lower values.

Biological enrichment pathways of functional disconnection

We identified 2936 genes in the PLS1 gene set (|Z | > 3). By comparing the PLS1 gene sets and the reported AD-related gene lists, we found six overlapping genes (i.e., BCHE, APOC1, CHRNA3, SORL1, PSEN2, and GSK3B) in comparison to in situ hybridization gene from AHBA (https://help.brain-map.org/display/humanbrain/Documentation), and 18 overlapping genes (i.e., ABCA1, ADAM10, ANK3, FERMT2, NTN5, APOE, PLCG2, HS3ST5, ABCA7, BCKDK, RASGEF1C, USP6NL, TNIP1, SORL1, WNT3, MYO15A, EPDR1, and SLC24A4) in comparison to genome-wide meta-analysis studies (GWAS)24,35. The expression matrix of these 23 genes can be found in Supplementary Fig. S2. In addition, we observed that 20 of 23 genes significantly correlated with the WM RFCS changes in spatial distribution. Among these correlations, 11 were positive (ABCA1, ADAM10, ANK3, APOC1, APOE, BCHE, CHRNA3, FERMT2, HS3ST5, NTN5, and PLCG2) and 9 were negative (EPDR1, GSK3B, MYO15A, PSEN2, RASGEF1C, SLC24A4, SORL1, TNIP1, and WNT3; all PFDR < 0.05; Fig. 5a and Supplementary Table S12). Moreover, we identified a protein–protein interaction (PPI) network with 14 edges (P < 8.07 × 10−13) for the 23 overlapping genes. Functional enrichments in this PPI network identified several Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways, such as “Alzheimer’s disease” (Fig. 5b). More terms can be found in Supplementary Fig. S3.

a Strong positive or negative correlation between specific gene expression and WM RFCS changes (ABCA1, ADAM10, ANK3, APOC1, APOE, BCHE, CHRNA3, EPDR1, FERMT2, GSK3B, HS3ST5, MYO15A, NTN5, PLCG2, PSEN2, RASGEF1C, SLC24A4, SORL1, TNIP1, WNT3, all PFDR < 0.05). b PPI network of overlapping genes, highlighting significantly enriched KEGG pathways, with “Alzheimer’s disease” marked in yellow. c Ontology terms for PLS1 genes. d Ontology terms enriched based on the classified PLS1 gene sets in different cell types (Astro, Astrocytes: number = 171, adjust Pperm = 0.0261; Endo, Endothelial: number = 137, adjusted Pperm > 0.05; Micro, Microglia: number = 111, adjust Pperm > 0.05; Neuro-Ex, Excitatory neurons: number = 293, adjust Pperm < 0.001; Neuro-In, Inhibitory neurons number = 233, adjust Pperm < 0.001; Oligo, Oligodendrocytes: number = 102, adjust Pperm > 0.05; OPCs, Oligodendrocyte precursors: number = 25, adjust Pperm > 0.05; permutation test, 10,000 times, FDR corrected).

We selected gene ontology (GO) biological processes and KEGG pathways to conduct the enrichment analysis on the PLS1 gene set. After correction for multiple comparison, significant GO biological processes associated with the PLS1 genes were identified, such as “trans-synaptic signaling,” “regulation of synapse structure or activity,” “modulation of chemical synaptic transmission,” “regulation of secretion,” “neuron projection development,” “behavior” (Fig. 5c, Supplementary Table S13). The multi-gene-list meta-analysis revealed eleven enrichment pathways overlapping between the PLS1 gene set and GWAS (Supplementary Fig. S4). These terms included “regulation of secretion,” “neuron projection development,” “regulation of synapse structure or activity,” “behavior,” “synapse organization,” and so on. We also revealed additional AD-related pathways that could not be obtained from genes in GWAS, including “lipid biosynthetic process,” “brain development,” “intracellular protein transport,” “trans-synaptic signaling,” and so on. These transcriptomic results remained robust when we applied a more stringent threshold to the PLS1 gene set (|Z| > 4) (Supplementary Information 9).

Cellular signatures

For genes in the significant PLS1 list, we observed notable distribution in excitatory neurons (293 genes), inhibitory neurons (233 genes), astrocytes (171 genes), endothelial cells (137 genes), microglia (111 genes), oligodendrocytes (102 genes), and oligodendrocyte precursors (25 genes). The number of genes in the excitatory neurons, inhibitory neurons, and astrocytes reached a significant level (permutation test, 10,000 times, all adjust Pperm < 0.0261, Fig. 5d). Functional enrichment results demonstrated five significant pathways, including the “regulation of synapse organization,” “regulation of plasma membrane bounded cell projection organization,” “modulation of chemical synaptic transmission,” and “neuron projection development” (Supplementary Fig. S5). The ontology terms and cell types information for the AD-related 23 genes from the PLS1 gene set are shown in Supplementary Table S14.

Reproducibility analysis

We replicated the main analyses on the validation dataset to evaluate the reproducibility of our findings (Supplementary Information 10). In the validation dataset, the age, sex, or education was matched (Supplementary Table S21) and regressed in all statistical analyses. Kruskal–Wallis test revealed significant differences in RFCS for some regions that overlapped with the findings from the discovery dataset (Supplementary Information 10.5). However, no significant topological difference was detected in the validation dataset after the false discovery rate (FDR) correction. Several factors may contribute to the non-significant results observed in the validation cohort, including differences in sample size, variability within the dataset, or heterogeneity of the patients. To further compare the results from the two datasets, we utilized the Dice Similarity Coefficient to compare the results from both datasets more effectively. We found a moderate-to-high reproducibility in the directional agreement for all fMRI phenotypic differences (Supplementary Information 10.6). Then we related gene expression to WM RFCS changes in the validation dataset. A total of 1699 genes in the PLS1 gene set (|Z| > 3) were identified and significantly overlapped with the genes obtained from the discovery dataset (odds ratio = 1.936, P < 0.0001). We further compared the significant GO biological processes and KEGG pathways (PFDR < 0.01) identified from two datasets, and observed a considerable overlap (odds ratio = 39.995, P < 0.0001) (Supplementary Information 10.8). The multi-gene-list meta-analysis revealed a substantial number of significant terms shared between both datasets, including “neuron projection development,” “synapse organization,” “behavior,” and “brain development” (Fig. 6). Other detailed information could be found in Supplementary Information 10. These overlapping results across datasets highlight the reproducibility of biological findings.

Discussion

Combining whole-brain resting-state FC and gene transcriptional profiles, we characterized AD’s dysfunctional connectivity and diagnosis-related transcriptional and cellular signatures in WM areas. Compared to CU individuals, both AD and MCI groups exhibited decreased intra-WM/-GM FC, increased inter-WM-GM FC, and reduced network properties (i.e., assortativity, global/local clustering coefficient, and nodal local efficiency) in WM (and in GM) functional networks. AD-specific dysfunctional connections were mainly distributed in WM regions, including the ALIC, the PLIC, the corona radiata, and the left tapetum. Moreover, based on the WM RFCS, we constructed PLS regression models and identified genes/cells associated with AD WM damage from a data-driven perspective. Twenty of twenty-three overlapped genes spatially correlated with the RFCS difference among clinical groups. Ontology terms enriched from the PLS1 gene set widely overlapped with terms obtained from GWAS and the validation dataset. Finally, we classified PLS1 genes into seven cell types, identifying the astrocytes and the excitatory and inhibitory cells as strong predictors of functional WM damage in AD.

Changed functional connectivity in the whole brain

Decreased FC within GM regions has been widely reported to correlate with AD patients’ deteriorated cognitive performance and detected in regions exhibiting abnormal amyloid deposition7,36. Results in this study consistently revealed that FC was weakened not only within GM but also within WM. The positive correlation between the intra-WM FC and MMSE suggests that the reduced FC within WM may be partly involved in cognitive impairment, similar to the observed GM effect. In contrast, FC between the WM and GM was enhanced, suggesting an excessive information exchange between these brain structures, possibly due to compensatory mechanisms37 and/or typically observed hyperactivity with AD progression38.

Furthermore, we noticed that ALIC, PLIC, the corona radiata, and the left tapetum were involved in the most significant group differences. The ALIC has been proposed as a target for deep brain stimulation in AD since its full connection with all neuromodulation targets39. The PLIC was previously observed to be involved in the FC aggravated in amnestic APOEε4 carriers, the major genetic risk for developing AD27. The corona radiata shows decreased fractional anisotropy linked to lower sphingomyelin, which may aid in vivo AD prediction40. The tapetum presents lower fractional anisotropy in individuals with a family history of AD41. These findings align with prior research and offer additional evidence highlighting the critical role that WM FC plays in AD development.

Abnormalities in gray matter and white matter functional network topology

For topological metrics, assortativity characterizes the resilience of a network. A network with high assortativity contains multiple nodes with similar degrees, thereby performing better in coping with nodal dysfunction. Global clustering coefficient is an index of functional segregation, and denotes the prevalence of connection clusters19. In the present study, we observed reduced assortativity coefficient and global clustering coefficient within the GM functional network in AD patients, which is highly consistent with previous studies7,42. Moreover, the lower global clustering coefficient in AD and MCI patients was observed within WM functional networks and the whole-brain network (i.e., including GM and WM). These results demonstrate the WM dysfunction in AD, supporting the vulnerability and disrupted specialized functioning of patients’ brain networks across the entire GM and WM.

Nodal clustering coefficient and local efficiency are the two leading indices of regional functional specificity. Local clustering coefficient reflects the prevalence of clustered connectivity around each node, while the local efficiency measures how efficiently a network exchanges information19. In the current study, nodal clustering coefficient and local efficiency were significantly decreased for AD or MCI groups within GM or WM regions. Specifically, these regions are primarily engaged in four functions: sensory-motor (i.e., postcentral gyrus43 and corticospinal tract44), visual-spatial (i.e., parahippocampal gyrus45, bilateral sagittal stratum46, temporal fusiform cortex47, temporal occipital fusiform cortex, supracalcarine cortex48, occipital pole, posterior thalamic radiation49, and left tapetum50), language (i.e., planum polare, heschls gyrus, planum temporale, and bilateral uncinate fasciculus51), and memory-executive function (i.e., parahippocampal gyrus45, anterior limb of internal capsule52). Noticeably, the deficits in these functions are the clinical phenotypes of AD53. These findings support that the two nodal metrics of WM effectively capture the pathological features typically observed in AD. Furthermore, it had been reported that reduced clustering coefficient and local efficiency in GM were accompanied by more tau burden in AD54. However, we did not detect significantly decreased local efficiency in GM regions. Given that our participants were classified as having mild AD, they may still be in an earlier stage of tau pathology development, which could account for the absence of abnormal local efficiency in our findings55,56. The relationship between WM functional network reconfiguration and amyloid and tau burden remains to be explored.

AD-risk genes related to the functional connectivity changes

The WM dysfunction pattern significantly co-localized with gene expression profiles. In the PLS1 gene set, we noted a strong-positive (or negative) spatial correlation between the 20 genes expression level and the changes of WM RFCS.

ABCA1 is linked to cholesterol transport and apolipoprotein E (APOE) metabolism in the brain57,58. The rare, predicted damaging variants in ABCA1, alongside variants in SORL1 and ABCA7, are significantly associated with increased AD risk59. The APOE ε4 allele plays a role in the toxicity of both β-amyloid and phosphorylated tau protein60 and is considered the most significant genetic risk factor for late-onset AD61. The influence of the APOE gene on cortical FC has been widely reported62,63,64. Moreover, the mutations in PSEN2 are unambiguously involved in the metabolism of brain amyloid-β61, and transcriptomic variations in PSEN2 may contribute to the pathogenesis of sporadic AD65. Beyond their roles in AD, these genes have also been implicated in other neurodegenerative diseases. For instance, ABCA1 is associated with Parkinson’s disease58, while APOE variants have been linked to frontotemporal dementia and vascular dementia60. In addition, our analysis found a strong correlation between BCHE gene expression and decreased RFCS in patients. BCHE encodes butyrylcholinesterase (BuChE), an enzyme highly expressed in WM and associated with amyloid protein plaque accumulation and AD progression66. Previous inhibition of BuChE has brought potential benefits for patients suffering from AD67. Furthermore, the SLC24A4 gene has emerged as a promising key biomarker for AD diagnosis due to its involvement in brain amyloidosis and tauopathy68. Our findings underscore a strong spatial relationship between these AD-related genes and WM FC, complementing the existing results. Additional direct and causal analyses are warranted to further elucidate the underlying biological mechanisms.

Biological processes enriched with the PLS1 gene set

We identified ontology terms enriched on the PLS1 gene set, which contained 11 of 13 terms enriched from genes in GWAS of AD24,35. These terms cover many biological functions, including behavior, protein, synapse, and cellular processes. Notably, synapse-related processes such as “regulation of synapse structure or activity,” “synapse organization,” and “modulation of chemical synaptic transmission” were detected. Synaptic loss and damage underlie the symptoms of neurodegenerative disease69. Trillions of synapses in the healthy brain form the path of information flow. In AD patients, the accumulation of amyloid-β may induce a decrease in synaptic signaling and damage the communication at synapses1. The processes of “neuron projection development” and “behavior” further illustrate the impact of AD on cognitive functions. Neuron projection development is crucial for establishing proper neural circuits. Proper neuronal projection plays a critical role in maintaining cognition and preventing neurodevelopmental disorders70. Research involving the AD mouse model suggested that a significant proportion of subcortical amyloid-β was derived from cortico-thalamic axonal projections71. In addition, it has been hypothesized that tau pathology within specific projection neurons, particularly those characterized by vulnerable microenvironments, can initiate sporadic AD72. These insights underscore the importance of neuronal projections in the progression of AD, and the changes in WM may underlie the cognitive impairment observed in AD patients. Importantly, these processes were replicable in the validation dataset, supporting the transcriptional signature of WM dysfunction in AD.

We also revealed additional AD-related pathways that could not be obtained from genes in GWAS. Abnormal “intracellular protein transport” was the earliest defect observed in neurodegenerative disorders and contributed to the pathogenesis of AD73. The “trans-synaptic signaling” involved communication between the post- and pre-synapses and mediated the establishment and plasticity of synapses. Disruption of trans-synaptic signaling could lead to dysfunction and cognitive impairment74. These terms showed a strong association with AD and further suggest the potential role of WM FC in AD pathology.

Cellular features

Finally, we observed that a substantial portion of the genes in the PLS1 list were significantly distributed in excitatory neurons, inhibitory neurons, and astrocytes. The excitatory neurons exhibited a decline as AD pathology progressed75. Among the excitatory neurons, the pyramidal cells were thought to be responsible for the spread of pathological proteins through their axons and, thus, the critical element in AD76. Inhibitory interneurons regulate neuronal network oscillations essential for cognitive functions. Disruption of inhibitory function contributed to hyperexcitability in AD, which may serve as a predictive marker of cognitive impairment38. Moreover, the balance between excitatory and inhibitory neuronal activity was essential for normal cognition. Disturbances in this balance serve as a key factor driving neurodegeneration and network dysfunction77 and could cause the intellectual decline in AD78. Astrocytes have been recognized for their remarkable morphological changes during AD progression. These cells are vital for nutrient supply for neurons, eliminating unnecessary synaptic connections79 and maintaining brain homeostasis maintenance80. Properly controlling astrocyte pathology could be a promising approach for AD treatment80,81.

Methodological considerations and future directions

Several limitations of the current study need to be noted. First, these results are based on a cross-sectional design, which cannot adequately delineate the relationship between the WM functional changes and the disease course. Second, our findings were primarily based on clinical dementia rating (CDR) scores, which could not fully capture the heterogeneity of the underlying conditions in the clinical groups. Third, environmental factors such as pollutants and lifestyle were not rigorously controlled. Exposure to environmental pollutants could induce oxidative stress, encourage the production of amyloid-β, and finally affect the epigenetic or genetic regulation82. Sleep disorder could lead to greater functional disconnection and compensatory functional network organization in MCI patients83. Future studies could benefit from exploring how various environmental variables interact with genetic factors in AD and MCI patients. Fourth, to minimize the nuisance effects on WM from nearby GM, we adopted a practical anatomical WM atlas to obtain WM regions. However, the inconsistent region sizes in the WM atlas inevitably impact the mean functional signal. How to segment the WM tract better for functional signal extraction could be an important topic for future work. Finally, the gene data were derived from the neurotypical templates based on postmortem tissue from cognitively normal individuals. Although the identified transcriptional patterns remain relevant in capturing vulnerability to disease factors, as proved by previous studies10, they may not be representative enough for the whole-brain molecular signatures of patients.

In summary, the current study characterized functional dysregulation in WM (and in GM) of the AD/MCI brain and its spatial gene expression and cellular correlates. AD and MCI individuals showed decreased FC and clustering coefficients in both GM and WM regions, which are linked to cognitive functions typically impaired in AD. Using the PLS model and enrichment analyses, we investigated the gene transcriptional signature associated with WM functional changes and obtained the related biological processes and cell types in AD. The identified ontology terms shared considerable overlap with terms obtained from GWAS and supported the significance of WM functional changes in AD. These findings provide insight into the association between the transcriptional data and WM dysfunction and further advance our understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms of AD.

Methods

Participants

The current study employed the discovery dataset shared from the OASIS-3 (https://www.oasis-brains.org/)30. Evaluated by the CDR score, all participants were categorized as 53 mild AD (CDR = 1), 90 MCI (CDR = 0.5), and 100 age-, sex-, and education-matched CU (CDR = 0). The MMSE was used to evaluate clinical symptoms. The detailed quality control steps for images can be found in Supplementary Information 1, lifestyle information is available in Supplementary Information 6, and the effect of APOE ε4 on FC is discussed in Supplementary Information 7. All participants were consented into Knight ADRC-related projects following procedures approved by the Institutional Review Board of Washington University School of Medicine.

As an independent validation sample, we included 175 participants with T1 and resting functional images, consisting of 38 AD, 65 MCI, and 72 CU. The validation dataset was obtained from the ADNI database (adni.loni.usc.edu). The ADNI was launched in 2003 as a public-private partnership, led by Principal Investigator Michael W. Weiner, MD. The primary goal of ADNI has been to test whether serial MRI, positron emission tomography, other biological markers, and clinical and neuropsychological assessment can be combined to measure the progression of MCI and early AD. For up-to-date information, see www.adni-info.org. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or authorized representatives and study partners. The research was conducted following protocols approved by the institutional review board at each participating site. All ethical regulations relevant to human research participants were followed.

MRI acquisition

Discovery dataset

High-resolution T1-weighted images and resting-state fMRI were acquired using a 16-channel head coil on Siemens TIM Trio 3 T scanners. The main scanning parameters for resting-state fMRI include: repetition time (TR) = 2200 ms, echo time (TE) = 27 ms, flip angle = 90°, number of slices = 36, slice thickness = 4 mm, and voxel size = 4 × 4 × 4 mm3. The scanning parameters for T1-weighted anatomical images are as follows: TR = 2400 ms, TE = 3.16 ms, flip angle = 8°, voxel size = 1 × 1 × 1 mm3, number of slices = 176, and slice thickness = 1 mm.

Validation dataset

MRI data were obtained on 3 T scanners. The main scanning parameters for resting-state fMRI include: TR = 3000 ms, TE = 30 ms, flip angle = 80°, number of slices = 48, slice thickness = 3.31 or 3.40 mm, and voxel size = 3.31 × 3.31 × 3.31 or 3.44 × 3.44 × 3.40 mm3. The scanning parameters for T1-weighted anatomical images are as follows: TR = 6.81 or 2300 ms, TE = 3.16 or 2.98 ms, flip angle = 9°, and voxel size = 1.2 × 1 × 1 or 1 × 1 × 1 mm3.

Preprocessing steps of functional images

The preprocessing of neuroimaging data was performed using the Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM12, https://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/software/spm12/) and Data Processing Assistant for Resting-State fMRI (DPARSF, V4.4_180801, http://rfmri.org/dparsf). The first 10 volumes of functional images were removed to avoid magnetization disequilibrium for each participant. The remaining 154 volumes were realigned. All participants have maximum motion <2 mm and 2°. The T1 structural images were co-registered and then segmented into GM, WM, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Nuisance signals (i.e., the 24 parameters and the mean signal of CSF) were regressed. A temporal scrubbing regressor was also utilized to reduce the effect of head motion. The linear trend was removed for the signal drift correction. The band-pass filtering (0.01–0.1 Hz) was used to reduce the impact of low-frequency drift and high-frequency physiological noise. Spatial smoothing was performed separately within the GM and WM templates with a 4 mm FWHM. Finally, the smoothed functional images were normalized into the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space and resampled to 3 × 3 × 3 mm3.

Obtaining the group-level white matter and gray matter masks

To avoid confusion between GM and WM signals, we created the group-level GM and WM mask in line with the previous study13,14. Specifically, by determining the maximum probability of whether each voxel belongs to the GM, WM, or CSF, we can get binarized GM and WM masks for each participant. Then, the individual masks were compared across all participants. Voxels that account for over 60% of the total individual WM templates were classified as WM. Noticeably, a lenient threshold greater than 20% across participants was adopted for GM, and any voxels identified in the WM mask were removed. In addition, the resulting GM and WM masks were compared to the functional images. Those voxels identified as GM or WM but accounted for less than 80% of functional data across all participants were also excluded. Finally, the Harvard-Oxford subcortical atlas32 was used to mark and exclude the deep regions from the group-level WM mask, including the thalamus, caudate nucleus, putamen, globus pallidus, and nucleus accumbens.

Constructing functional connectivity matrices in white matter and gray matter

Before performing the network properties analysis, we conducted the point multiplication on the group-level WM mask and the JHU ICBM-DTI-81 WM atlas31 to obtain a final WM atlas with 48 ROIs. This procedure to obtain the final WM atlas has been widely employed in previous studies8,10,13, matching the anatomical architecture well12, and allowing for consistency and comparability with existing literature. We excluded 3 ROIs with no voxels or the number of voxels was one. Eventually, 45 ROIs were retained as the final WM mask. Additionally, the group-level GM mask was point multiplied with the Harvard-Oxford cortical atlas32 to obtain the final GM mask with 96 ROIs. For details on ROIs, see Supplementary Tables S3 and S4.

The averaged time series of each WM/GM ROI was separately extracted from the functional images for each participant. By conducting Pearson’s correlation analysis between each pair of WM masks, we obtained a 45 × 45 WM correlation matrix for each participant and transformed the correlation coefficient into Fisher’s Z score. Similarly, we obtained a 96 × 96 GM connection matrix and a 141 × 141 whole-brain connectivity matrix for each individual.

Network topological property analysis

Graph theoretical analysis was carried out using the Graph Theoretical Network Analysis (GRETNA) Toolbox (http://www.nitrc.org/projects/gretna/). The sparsity threshold values were identified by referring to the previous study22. The maximal threshold was defined as the correlation coefficient value, which ensured all connections were significant (P < 0.05). The minimum threshold was defined as follows: (1) the mean degree over all nodes of each network was >2 × log(N) (N expresses the number of nodes, N = 45 in WM network, N = 96 in GM network, and N = 141 in the whole-brain network); (2) the number of nodes in the largest component was >70% × N. The range of sparsity thresholds was 0.23–0.46 for the WM functional network, 0.11–0.50 for the GM functional network, and 0.09–0.47 for the whole-brain network, with a common step of 0.01.

To characterize the topological properties of brain networks, we calculated two global network metrics (i.e., assortativity and global clustering coefficient) and two nodal parameters (i.e., nodal clustering coefficient and nodal local efficiency) on the unweighted, undirected graphs.

Assortativity quantifies the resilience of a network. The formula is as follows:

\({k}_{i}\), \({k}_{j}\) are the degrees of the nodes at the ends of the edge \(i\), with \(i=1\ldots l\).

Clustering coefficient of node \(i\) characterizes the prevalence of clustered connectivity around individual nodes, and is defined as follows:

\(C(i)\) is the clustering coefficient of node \(i\), \({t}_{i}\) is the number of edges in the subgraph \({N}_{i}\), and \({k}_{i}\) represents the number of nodes connected to node \(i\).

Local efficiency measures how efficient the communication is between the first neighbors of a node \(i\) when \(i\) is removed. The formula is as follows:

\({k}_{i}\) is the number of nodes in the subgraph \({N}_{i}\) that includes all neighboring nodes of node i, and \({d}_{{jh}}({N}_{i})\) is the shortest path length between node j and node h in subgraph \({N}_{i}\).

Statistical analyses

To investigate the differences among AD, MCI, and CU groups, we conducted statistical analysis on FC, graph theoretical metrics, and RFCS separately. We performed non-parametric permutation tests on FC (10,000 times) and conducted the Kruskal–Wallis test on RFCS and the area under the curve (AUC) of topological metrics. In the post hoc analysis, the Mann-Whitney U test was used for all measures. Among all the above analyses, the effects of age, sex, and education were all regressed as covariates. Finally, a robust Spearman’s rank correlation with a bootstrap of 1000 times was performed to examine the association between clinical characteristics and FC. Unless otherwise specified, all P values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the FDR procedure with a significant threshold of 0.05.

The trade-off in the gene dataset

Microarray dataset from the AHBA can provide a spatially refined analysis of gene expression across brain regions and has been utilized in many high-quality studies investigating various neuropsychiatric disorders, including AD23, schizophrenia84, neurodevelopmental disorders85, major depressive disorder86, and other major psychiatric disorders10. However, this spatial resolution comes with trade-offs. Microarray has a more restricted dynamic range and typically detects fewer differentially expressed genes than RNA-Seq87. In our study, we opted to use the same AHBA microarray dataset as earlier neuropsychiatric research, as this detailed mapping of gene expression patterns is particularly valuable for our current study. We conducted two supplementary experiments to validate the quality of gene data (Supplementary Information 11).

Microarray gene expression

Regional microarray expression data were obtained from 6 postmortem brains (one female, ages 24.0–57.0, mean (s.d.) = 42.50 (13.38), Supplementary Information 2) provided by the AHBA29 (https://human.brain-map.org). Data were processed with the abagen toolbox (version 0.1.3; https://github.com/rmarkello/abagen) using a 45-region volumetric atlas in MNI space. First, microarray probes were reannotated using data provided by the reference88, probes not matched to a valid Entrez ID were discarded. Next, probes were filtered based on their expression intensity relative to background noise89, yielding 31,569 probes. When multiple probes indexed the expression of the same gene, we selected and used the probe with the most consistent pattern of regional variation across donors90 (i.e., differential stability). Gene expression values were normalized across tissue samples using a robust sigmoid function91. Samples assigned to the same brain region were averaged separately for each donor and across donors. Finally, we got a 45 × 15,632 regional expression matrix for WM and a 96 × 15,632 regional expression matrix for GM. See Supplementary Information 3 for detailed reports on estimating gene expression matrices.

Relating gene expression to functional changes in brain regions

To relate the FC of each brain region to the transcriptional values, we calculated the RFCS. For WM regions, RFCS was estimated by averaging its FC with the other 44 WM regions. Similarly, for GM regions, RFCS was calculated by averaging its FC with the other 95 GM regions. Group differences in RFCS were examined using the Kruskal–Wallis test (see “Methods,” subsection “Statistical analyses”).

Because the right hemispheres in the AHBA dataset were incomplete (i.e., two of the six right hemispheres were collected)88, gene expression values of only 48 GM ROIs and 21 WM ROIs in the left hemisphere were used for subsequent analyses. A PLS regression model34 was built using the principal components of the imaging-transcription matrix as the independent variables to predict the group differences in GM or WM RFCS, respectively. Then, the permutation test (5000 times) was used to evaluate the significance of the variance. After that, we performed bootstrapping to estimate the PLS1 weights for each gene and normalized the weight scores. PLS1 genes were filtered using the weight score |Z| > 384.

Enrichment analysis

To figure out the molecular features of the thousands of genes, we submitted the PLS1 (|Z| > 3) gene set to Metascape92 (http://metascape.org). Two core default ontologies (i.e., GO biological processes and KEGG pathways) were selected. The significant threshold of 0.05 was set for all terms, and FDR correction was used for multiple comparisons. Moreover, to compare the gene set obtained by data-driven analysis versus genes derived through meta-analysis, we conducted the multi-gene-list meta-analysis between the PLS1 gene set and AD risk genes from the GWAS24,35. Furthermore, a PPI network for the overlapped genes was identified by utilizing STRING (version 12.0, https://string-db.org/), with a high confidence value of 0.793.

Cell types

We assigned the PLS1 gene set to seven types of cells, including the astrocytes, endothelial cells, microglia, excitatory neurons, inhibitory neurons, oligodendrocytes, and oligodendrocyte precursors, by overlapping the PLS1 gene set with previously reported gene sets for each cell type85. Next, a permutation test was conducted to determine the significant number of genes belonging to each cell type. Finally, we performed functional enrichment analysis based on the gene set within each cell type to investigate the cellular signatures associated with the abnormal WM RFCS.

Statistics and reproducibility

Statistics were performed using MATLAB and GraphPad Prism. See the above section titled “Statistical analyses” for details. For the genetic analysis, the comparative analysis was performed using both GM and WM (Supplementary Information 8). The transcriptomic results remained robust when we applied a more stringent threshold to the PLS1 gene set (|Z| > 4) (Supplementary Information 9). We repeated the main analysis on the validation dataset obtained from the ADNI database (38 AD, 65 MCI, and 72 CU). To quantify the reproducibility of WM dysfunction in AD, we calculated the Dice Similarity Coefficient based on t value signs (e.g., AD vs. CU) between the discovery and validation datasets. To validate the transcriptomic findings, we performed a multi-gene-list meta-analysis on the PLS1 gene sets from both datasets, utilizing the odds ratio to measure the degree of overlap. Details are shown in Supplementary Information 10.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Imaging data supporting this study are publicly available from the OASIS-3 dataset (https://central.xnat.org) and the ADNI dataset (https://adni.loni.usc.edu/) upon registration and compliance with the data usage agreement. Human gene expression data in this study are available from the Allen Brain Atlas (“Complete normalized microarray datasets,” https://human.brain-map.org/static/download). Cell-specific gene set list can be obtained at https://static-content.springer.com/esm/art%3A10.1038%2Fs41467-020-17051-5/MediaObjects/41467_2020_17051_MOESM8_ESM.xlsx. The gene sets derived from PLS1 and GWAS can be found in Supplementary Data 1 and 2, respectively.

Code availability

All analytical procedures in the current study are based on publicly available software. The neuroimaging preprocessing, functional connectivity, and graph theoretical analysis are performed using SPM12, DPARSF (V4.4_180801, http://rfmri.org/dparsf), and GRETNA (v2.0.0, http://www.nitrc.org/projects/gretna/), respectively. Transcriptional level matrices were obtained using the abagen toolbox (v.0.1.4, https://github.com/rmarkello/abagen) on the AHBA dataset (http://human.brain-map.org). Codes for PLS can be found at https://github.com/SarahMorgan/Morphometric_Similarity_SZ84. The adapted codes are available on Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15294200)94. Gene enrichments were performed at https://metascape.org/gp/#/main/step1. The brain maps were visualized with the BrainNet Viewer (v1.7, https://www.nitrc.org/projects/bnv/).

References

Alzheimers Dement. 2023 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 19, 1598–1695 (2023).

Jack, C. R. et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 14, 535–562 (2018).

Iturria-Medina, Y. & Evans, A. C. On the central role of brain connectivity in neurodegenerative disease progression. Front. Aging Neurosci. 7, 1–10 (2015).

Pereira, J. B. et al. Amyloid and tau accumulate across distinct spatial networks and are differentially associated with brain connectivity. eLife 8, e50830 (2019).

Mijalkov, M. et al. Nonlinear changes in delayed functional network topology in Alzheimer’s disease: relationship with amyloid and tau pathology. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 15, 112 (2023).

Vogel, J. W. et al. Connectome-based modelling of neurodegenerative diseases: towards precision medicine and mechanistic insight. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 24, 620–639 (2023).

Wang, J. et al. Disrupted functional brain connectome in individuals at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Biol. Psychiatry 73, 472–481 (2013).

Ding, Z. et al. Detection of synchronous brain activity in white matter tracts at rest and under functional loading. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA115, 595–600 (2018).

Huang, Y. et al. Intracranial electrophysiological and structural basis of BOLD functional connectivity in human brain white matter. Nat. Commun. 14, 3414 (2023).

Ji, G.-J. et al. White matter dysfunction in psychiatric disorders is associated with neurotransmitter and genetic profiles. Nat. Ment. Health 1, 655–666 (2023).

Li, M., Gao, Y., Ding, Z. & Gore, J. C. Power spectra reveal distinct BOLD resting-state time courses in white matter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2103104118 (2021).

Huang, Y. et al. Detection of functional networks within white matter using independent component analysis. Neuroimage 222, 117278 (2020).

Peer, M., Nitzan, M., Bick, A. S., Levin, N. & Arzy, S. Evidence for functional networks within the human brain’s white matter. J. Neurosci. 37, 6394–6407 (2017).

Wang, P. et al. Structural and functional connectivity mapping of the human corpus callosum organization with white-matter functional networks. Neuroimage 227, 117642 (2021).

Wang, P. et al. White matter functional connectivity in resting-state fMRI: robustness, reliability, and relationships to gray matter. Cereb. Cortex 32, 1547–1559 (2022).

Nasrabady, S. E., Rizvi, B., Goldman, J. E. & Brickman, A. M. White matter changes in Alzheimer’s disease: a focus on myelin and oligodendrocytes. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 6, 22 (2018).

Taylor, A. N. W. et al. Tract-specific white matter hyperintensities disrupt neural network function in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 13, 225–235 (2017).

Gao, Y. et al. Functional connectivity of white matter as a biomarker of cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS ONE 15, e0240513 (2020).

Rubinov, M. & Sporns, O. Complex network measures of brain connectivity: uses and interpretations. Neuroimage 52, 1059–1069 (2010).

Yu, H., Lei, X., Song, Z., Liu, C. & Wang, J. Supervised network-based Fuzzy learning of EEG signals for Alzheimer’s disease identification. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 28, 60–71 (2020).

Li, J. et al. White-matter functional topology: a neuromarker for classification and prediction in unmedicated depression. Transl. Psychiatry 10, 365 (2020).

Jiang, Y. et al. Characteristics of disrupted topological organization in white matter functional connectome in schizophrenia. Psychol. Med. 52, 1333–1343 (2022).

Adewale, Q., Khan, A. F., Carbonell, F. & Iturria-Medina, Y.Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative Integrated transcriptomic and neuroimaging brain model decodes biological mechanisms in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. eLife 10, e62589 (2021).

Bellenguez, C. et al. New insights into the genetic etiology of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Nat. Genet. 54, 412–436 (2022).

Fornito, A., Arnatkevičiūtė, A. & Fulcher, B. D. Bridging the gap between connectome and transcriptome. Trends Cogn. Sci. 23, 34–50 (2019).

Hibar, D. P. et al. Common genetic variants influence human subcortical brain structures. Nature 520, 224–229 (2015).

Lin, H. et al. Disrupted white matter functional connectivity in aMCI APOEε4 carriers: a resting-state study. Brain Imaging Behav. 15, 1739–1747 (2021).

Yu, H. et al. Morphological connectivity differences in Alzheimer’s disease correlate with gene transcription and cell-type. Hum. Brain Mapp. 44, 6364–6374 (2023).

Hawrylycz, M. J. et al. An anatomically comprehensive atlas of the adult human brain transcriptome. Nature 489, 391–399 (2012).

LaMontagne, P. J. et al. OASIS-3: longitudinal neuroimaging, clinical, and cognitive dataset for normal aging and Alzheimer disease. medRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2019.12.13.19014902 (2019).

Mori, S. et al. Stereotaxic white matter atlas based on diffusion tensor imaging in an ICBM template. Neuroimage 40, 570–582 (2008).

Desikan, R. S. et al. An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. Neuroimage 31, 968–980 (2006).

Markello, R. D. et al. Standardizing workflows in imaging transcriptomics with the abagen toolbox. eLife 10, e72129 (2021).

Abdi, H. Partial least squares regression and projection on latent structure regression (PLS regression). WIREs Comp. Stat. 2, 97–106 (2010).

Wightman, D. P. et al. A genome-wide association study with 1,126,563 individuals identifies new risk loci for Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Genet. 53, 1276–1282 (2021).

Sheline, Y. I. & Raichle, M. E. Resting state functional connectivity in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Biol. Psychiatry 74, 340–347 (2013).

Jones, D. T. et al. Cascading network failure across the Alzheimer’s disease spectrum. Brain 139, 547–562 (2016).

Targa Dias Anastacio, H., Matosin, N. & Ooi, L. Neuronal hyperexcitability in Alzheimer’s disease: What are the drivers behind this aberrant phenotype?. Transl. Psychiatry 12, 257 (2022).

Cheyuo, C. et al. Connectomic neuromodulation for Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of invasive and non-invasive techniques. Transl. Psychiatry 12, 490 (2022).

Gonzalez, C. E. et al. Peripheral sphingolipids are associated with variation in white matter microstructure in older adults. Neurobiol. Aging 43, 156–163 (2016).

Bendlin, B. B. et al. White matter is altered with parental family history of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 6, 394–403 (2010).

Fathian, A. et al. The trend of disruption in the functional brain network topology of Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Rep. 12, 14998 (2022).

Mastria, G. et al. Morphology, connectivity, and encoding features of tactile and motor representations of the fingers in the human precentral and postcentral gyrus. J. Neurosci. 43, 1572–1589 (2023).

Feng, W. et al. Corticospinal tract lesion load: an imaging biomarker for stroke motor outcomes. Ann. Neurol. 78, 860–870 (2015).

LaFlamme, E. M., Waguespack, H. F., Forcelli, P. A. & Malkova, L. The parahippocampal cortex and its functional connection with the hippocampus are critical for nonnavigational spatial memory in macaques. Cereb. Cortex 31, 2251–2267 (2021).

Berro, D. H., Herbet, G. & Duffau, H. New insights into the anatomo-functional architecture of the right sagittal stratum and its surrounding pathways: an axonal electrostimulation mapping study. Brain Struct. Funct. 226, 425–441 (2021).

Spagna, A., Hajhajate, D., Liu, J. & Bartolomeo, P. Visual mental imagery engages the left fusiform gyrus, but not the early visual cortex: a meta-analysis of neuroimaging evidence. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 122, 201–217 (2021).

Zhang, X. et al. Association of visual health with depressive symptoms and brain imaging phenotypes among middle-aged and older adults. JAMA Netw. Open 5, e2235017 (2022).

Zarkali, A. et al. Fiber-specific white matter reductions in Parkinson hallucinations and visual dysfunction. Neurology 94, e1525–e1538 (2020).

Lee, S. W. et al. White matter abnormalities of the tapetum and their associations with duration of untreated psychosis and symptom severity in first-episode psychosis. Schizophr. Res. 201, 437–438 (2018).

Zhang, J. et al. Correlations between dual-pathway white matter alterations and language impairment in patients with aphasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychol. Rev. 31, 402–418 (2021).

Benito-León, J. et al. Diffusion tensor imaging in orthostatic tremor: a tract-based spatial statistics study. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 6, 2212–2222 (2019).

Graff-Radford, J. et al. New insights into atypical Alzheimer’s disease in the era of biomarkers. Lancet Neurol. 20, 222–234 (2021).

Cope, T. E. et al. Tau burden and the functional connectome in Alzheimer’s disease and progressive supranuclear palsy. Brain 141, 550–567 (2018).

Schöll, M. et al. Biomarkers for tau pathology. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 97, 18–33 (2019).

Jagust, W. Imaging the evolution and pathophysiology of Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 19, 687–700 (2018).

Horgusluoglu, E. et al. Integrative metabolomics-genomics approach reveals key metabolic pathways and regulators of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 18, 1260–1278 (2022).

Paseban, T., Alavi, M. S., Etemad, L. & Roohbakhsh, A. The role of the ATP-Binding Cassette A1 (ABCA1) in neurological disorders: a mechanistic review. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 27, 531–552 (2023).

Holstege, H. et al. Exome sequencing identifies rare damaging variants in ATP8B4 and ABCA1 as risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Genet. 54, 1786–1794 (2022).

Shi, Y. et al. ApoE4 markedly exacerbates tau-mediated neurodegeneration in a mouse model of tauopathy. Nature 549, 523–527 (2017).

Frisoni, G. B. et al. The probabilistic model of Alzheimer disease: the amyloid hypothesis revised. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 23, 53–66 (2022).

Butt, O. H. et al. Network dysfunction in cognitively normal APOE ε4 carriers is related to subclinical tau. Alzheimers Dement. 18, 116–126 (2022).

Singh, N. A. et al. APOE ε4 influences within and between network functional connectivity in posterior cortical atrophy and logopenic progressive aphasia. Alzheimers Dement. 19, 3858–3866 (2023).

De Marco, M. & Venneri, A. ApoE-dependent differences in functional connectivity support memory performance in early-stage Alzheimer’s disease (P4.094). Neurology 88, P4.094 (2017).

Course, M. M. et al. Aberrant splicing of PSEN2, but not PSEN1, in individuals with sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 146, 507–518 (2023).

Li, Q., Yang, H., Chen, Y. & Sun, H. Recent progress in the identification of selective butyrylcholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 132, 294–309 (2017).

Xing, S. et al. Structure and therapeutic uses of butyrylcholinesterase: application in detoxification, Alzheimer’s disease, and fat metabolism. Med. Res. Rev. 41, 858–901 (2021).

Tan, M.-S. et al. Associations of Alzheimer’s disease risk variants with gene expression, amyloidosis, tauopathy, and neurodegeneration. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 13, 15 (2021).

Griffiths, J. & Grant, S. G. N. Synapse pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 139, 13–23 (2023).

Wang, N., Wan, R. & Tang, K. Transcriptional regulation in the development and dysfunction of neocortical projection neurons. Neural Regen. Res. 19, 246–254 (2024).

Sasmita, A. O. et al. Oligodendrocytes produce amyloid-β and contribute to plaque formation alongside neurons in Alzheimer’s disease model mice. Nat. Neurosci. 27, 1668–1674 (2024).

Arnsten, A. F. T., Datta, D., Del Tredici, K. & Braak, H. Hypothesis: Tau pathology is an initiating factor in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 17, 115–124 (2021).

Larose, A., Miller, C. C. J. & Mórotz, G. M. The lemur tail kinase family in neuronal function and disfunction in neurodegenerative diseases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 81, 447 (2024).

Südhof, T. C. Towards an understanding of synapse formation. Neuron 100, 276–293 (2018).

Mathys, H. et al. Single-cell atlas reveals correlates of high cognitive function, dementia, and resilience to Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Cell 186, 4365–4385.e27 (2023).

Ruan, Z. et al. Alzheimer’s disease brain-derived extracellular vesicles spread tau pathology in interneurons. Brain 144, 288–309 (2021).

Maestú, F., De Haan, W., Busche, M. A. & DeFelipe, J. Neuronal excitation/inhibition imbalance: core element of a translational perspective on Alzheimer pathophysiology. Ageing Res. Rev. 69, 101372 (2021).

Lauterborn, J. C. et al. Increased excitatory to inhibitory synaptic ratio in parietal cortex samples from individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Commun. 12, 2603 (2021).

Lee, J.-H. et al. Astrocytes phagocytose adult hippocampal synapses for circuit homeostasis. Nature 590, 612–617 (2021).

Arranz, A. M. & De Strooper, B. The role of astroglia in Alzheimer’s disease: pathophysiology and clinical implications. Lancet Neurol. 18, 406–414 (2019).

Kim, J., Yoo, I. D., Lim, J. & Moon, J.-S. Pathological phenotypes of astrocytes in Alzheimer’s disease. Exp. Mol. Med. 56, 95–99 (2024).

Rahman, M. A. et al. Emerging risk of environmental factors: insight mechanisms of Alzheimer’s diseases. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 27, 44659–44672 (2020).

Luo, Y. et al. Functional brain connectivity in mild cognitive impairment with sleep disorders: a study based on resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging. Front. Aging Neurosci. 14, 812664 (2022).

Morgan, S. E. et al. Cortical patterning of abnormal morphometric similarity in psychosis is associated with brain expression of schizophrenia-related genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 9604–9609 (2019).

Seidlitz, J. et al. Transcriptomic and cellular decoding of regional brain vulnerability to neurogenetic disorders. Nat. Commun. 11, 3358 (2020).

Li, J. et al. Cortical structural differences in major depressive disorder correlate with cell type-specific transcriptional signatures. Nat. Commun. 12, 1647 (2021).

Zhao, S., Fung-Leung, W.-P., Bittner, A., Ngo, K. & Liu, X. Comparison of RNA-seq and microarray in transcriptome profiling of activated T cells. PLoS ONE 9, e78644 (2014).

Arnatkevic̆iūtė, A., Fulcher, B. D. & Fornito, A. A practical guide to linking brain-wide gene expression and neuroimaging data. Neuroimage 189, 353–367 (2019).

Quackenbush, J. Microarray data normalization and transformation. Nat. Genet. 32, 496–501 (2002).

Hawrylycz, M. et al. Canonical genetic signatures of the adult human brain. Nat. Neurosci. 18, 1832–1844 (2015).

Fulcher, B. D., Little, M. A. & Jones, N. S. Highly comparative time-series analysis: the empirical structure of time series and their methods. J. R. Soc. Interface 10, 20130048 (2013).

Zhou, Y. et al. Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. Nat. Commun. 10, 1523 (2019).

Szklarczyk, D. et al. STRING v11: protein–protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D607–D613 (2019).

Li, Y. White matter dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease is associated with disease-related transcriptomic signatures. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15294200 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by grants from the Sichuan Science and Technology Program (grant number: 2024NSFSC1661), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers: NSFC62401106 and NSFC62171101), and the China MOST2030 Brain Project (grant number: 2022ZD0208500). The cell cartoon components in Fig. 1 were from Servier Medical Art, provided by Servier, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 unported license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/). The discovery dataset was provided by OASIS (OASIS-3: Longitudinal Multimodal Neuroimaging): Principal Investigators: T. Benzinger, D. Marcus, J. Morris; NIH P30 AG066444, P50 AG00561, P30 NS09857781, P01 AG026276, P01 AG003991, R01 AG043434, UL1 TR000448, R01 EB009352. AV-45 doses were provided by Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, a wholly owned subsidiary of Eli Lilly. Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the ADNI database (adni.loni.usc.edu). As such, the investigators within the ADNI contributed to the design and implementation of ADNI and/or provided data but did not participate in the analysis or writing of this report. A complete listing of ADNI investigators can be found at: https://adni.loni.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/how_to_apply/ADNI_Acknowledgement_List.pdf. The validation dataset collection and sharing for this project were funded by the ADNI (National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904) and DOD ADNI (Department of Defense award number W81XWH-12-2-0012). ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: AbbVie, Alzheimer’s Association; Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation; Araclon Biotech; BioClinica, Inc.; Biogen; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; CereSpir, Inc.; Cogstate; Eisai Inc.; Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; EuroImmun; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and its affiliated company Genentech, Inc.; Fujirebio; GE Healthcare; IXICO Ltd; Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC.; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development LLC.; Lumosity; Lundbeck; Merck & Co., Inc.; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC.; NeuroRx Research; Neurotrack Technologies; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfizer Inc.; Piramal Imaging; Servier; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company; and Transition Therapeutics. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research is providing funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute at the University of Southern California. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of Southern California.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.B. and P.W. led the project. Y.L., P.W., and B.B. were responsible for the study concept and the design of the study. Y.L. and G.Z. performed the reproducibility analysis. Y.L. and P.W. analyzed the neuroimaging data. Y.L. and J.P. analyzed the transcriptional data. Y.L., L.L., and F.Z. created the figures. Y.L. wrote the manuscript. Y.L., P.W., Y.I.-M., D.Y., and B.B. revised the draft. All authors approved the final version to be submitted for publication and agree to be accountable for all aspects of this work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Eva Bagyinszky and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Ibrahim Javed and Joao Valente and Joao Valente. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Zhou, G., Peng, J. et al. White matter dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease is associated with disease-related transcriptomic signatures. Commun Biol 8, 820 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08177-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08177-7