Abstract

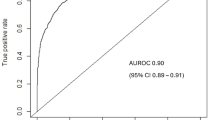

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is a life-threatening condition characterized by the dilation of the abdominal aorta, leading to a high risk of rupture. Current treatment options are limited, particularly for patients ineligible for surgical interventions. This study explores a novel immunotherapeutic approach using chimeric antigen receptor Treg cells targeting vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) to mitigate AAA progression. By leveraging the specificity and regulatory function of CAR-Treg cells, our research aims to modulate the immune response and reduce inflammation in the aneurysmal wall. Results from preclinical mouse models demonstrated that CAR-Treg cells effectively homed to the aneurysmal site, suppressed local inflammation, and decreased aortic dilation compared to control groups. These findings suggest that CAR-Treg cell therapy could provide a promising, non-surgical treatment option for AAA patients, addressing a critical unmet need in cardiovascular disease management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) stands as a critical health challenge globally, characterized by the pathological segmental dilation of the abdominal aorta. This condition poses a substantial risk of rupture, leading to severe hemorrhage and even fatal consequences1,2. Despite advancements in open surgery and endovascular therapy, there remains a conspicuous absence of effective pharmacological interventions for nonoperation-indicated AAAs3, necessitating innovative therapeutic approaches4,5. One promising avenue lies in harnessing the potential of immunotherapy, particularly focusing on modulating immune regulatory mechanisms.

The immune system’s intricate involvement in AAA pathogenesis has garnered significant attention in recent years. Increasing evidence suggests that AAA displays autoimmune disease characteristics. Particularly, T lymphocytes responding to AAA-related antigens in the aortic wall may contribute to an initial immune response. On the other hand, regulatory T lymphocytes (Tregs), as suppressors of T lymphocytes, present a notable deficiency in number and functionality in AAA patients, indicating a dysregulated immune response in the disease milieu6. Consequently, exploring strategies to augment Treg function emerges as a compelling therapeutic strategy. Intervention targeting the function or number of Treg cells in AAA is an effective strategy to inhibit the development of AAA7. In vitro adoptive transfer has yielded good results in mouse AAA models, but the excessive use of lymphocytes cultured in vitro may cause systemic immunosuppression in the body, and the imbalance of immune cells may lead to ineffective and disordered inflammatory responses8,9,10,11.

Chimeric antigen receptor technology and its application are important advances in cell and gene therapy in recent years12,13,14. Chimeric antigen receptor T lymphocytes therapy, a groundbreaking immunotherapeutic modality, has revolutionized cancer treatment by endowing T lymphocytes with enhanced antigen specificity and cytotoxicity. Extending the application of CAR technology to modulate immune regulatory pathways by using Treg instead of T lymphocytes presents a novel approach in AAA management6. Targeting key molecules implicated in AAA pathophysiology, such as vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), holds promise in mitigating disease progression. It provides a more accurate treatment method for cell therapy and has achieved good results in hematologic tumors15,16. Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) appears in activated endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells17. It can assist inflammatory cells in migrating to the lesion site via endothelial cells, and has been used as a therapeutic target for AAA in animal models18,19,20.

In this study, we aimed to construct a CAR-engineered regulatory T (CAR-Treg) cells targeting VCAM-1, explore its targeting potential and effect on AAA progression in mice, and delineate the possible underlying mechanisms. Through comprehensive in vivo investigations, we also seek to validate the efficacy and safety of this innovative immunotherapeutic approach.

Results

Treg cell communication and transcription factor dynamics in AAA and their implications for Treg cell function

A total of 8 AAA specimens and 8 normal abdominal aorta specimens from healthy individuals were collected (Supplementary Table 1). In AAA group, 7 of eight tissue were sent for single-cell sequencing, and 6 of eight normal abdominal aorta tissue were sent for scRNA-seq. Moreover, in AAA group, 5 of eight patients’ peripheral blood samples and were sent for single-cell sequencing. The six normal control peripheral blood samples for scRNA-seq from GEO database. In this study, extensive collections of tissue and blood samples were acquired for clinical purposes, including single-cell sequencing analyses. 42,287 tissue cells and 46,184 blood cells were collected from patients afflicted with abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA), alongside 39,445 tissue cells and 41,678 blood cells from a normative population.

Following rigorous quality control measures, normalization, and dimensionality reduction, an overall increase in T cell counts was observed in the blood and tissue samples from AAA patients, indicating a close association between T cells and the formation of abdominal aortic aneurysms (Fig. 1A). To further investigate the immunoregulatory functions of T cells, we isolated T cell populations from blood and tissue samples and classified them into several heterogeneous subgroups, including regulatory T cells (Tregs), activated CD4+ T cells, activated T cells, CD8+ T cells, cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs), naive CD4+ T cells, naive T cells, and γδT cells (Supplementary Table 2). The presence of Treg cells was consistently observed in both blood and tissue samples (Fig. 1B–E). The samples were corrected using Harmony, demonstrating good sample overlap (Supplementary Fig. 1A–D). The distribution of various T cell types, including Tregs, was described proportionally in the supplementary materials (Supplementary Fig. 1E).

Proportions of T cells, B cells, and plasma cells in arterial tissues from 7 AAA patients and blood samples from 6 AAA patients (A). UMAP plots of all T cell types in blood samples from AAA (left) and HC (middle). We also showing the distribution proportions of cell types and Treg cells are highlighted in red (B). UMAP plots of all T cell types in tissue samples from AAA (left) and HC (middle) and Treg cells are also highlighted in red (C). Dot plot showing increasing and decreasing trends of communication between Tregs from different sources (D). Signal communication activity of Tregs from PBMC and arterial tissue (E). Two overall signal patterns show the relative communication intensity between T cells from controls and T cells from AAA (F). Communication intensity of three different pathways (IL16, SELPLG, MHC-II) within different types of T cells (G). Three violin plots (H, I) represent gene expression in the three pathways. Expression in different types of T cells (tissue and PBMC cells) from AAA is shown in pink, while expression in the control group is shown in dark green.

Treg cells are a subclass of suppressive T cells that regulate the immune system, maintain tolerance to self-antigens, and prevent autoimmune diseases. Additionally, the proportion of Treg cells in blood and tissue samples was higher in the normal group compared to the AAA group (Fig. 1B, D). To explore the connection between Tregs from different sources and further investigate their differences during disease progression, we extracted common T cell types and conducted detailed discussions using cell communication analysis (Supplementary Fig 2A, B). The results indicated that blood-derived Tregs were enriched in the IL16, SELPLG, and MHC-II pathways (Supplementary Fig. 2D). Similarly, tissue-derived Tregs exhibited the same trend (Fig. 1E). Tregs from different sources in AAA patients showed good intercellular connectivity and were closely associated with CD8+ T cells (Fig. 1G, H and Supplementary Fig. 2). CD8+ and CD4+ T cells are associated with immune activation, and they communicate closely with Tregs. Therefore, Tregs, which are sensitive to antigen presentation and response-related T cells, show strong communication with these cells. This strong communication may indicate that Tregs help eliminate inflammation by suppressing immune responses, thereby protecting blood vessels from the formation of AAA.

Subsequently, we thoroughly explored the differences in receptor pairing. In the communication between blood-derived and tissue-derived Tregs in AAA, the receptor pairs HLA-DPB1/CD4, IL6/CD4, and SELPLG/SELL were upregulated (Fig. 1G–I). We extracted differentially upregulated signaling pathways for separate discussion. We observed an increased signal intensity in the MHC-II pathway related to antigen presentation at both blood and tissue levels in AAA patients (Supplementary Fig. 2E, F). Furthermore, communication results showed that the connection between blood-derived and tissue-derived Tregs in the AAA group became tighter. A similar trend was observed in pathways related to IL16 and SELPLG. SELPLG is the ligand for P-selectin, a high-affinity counter-receptor for the cell adhesion molecules P-, E-, and L-selectin. Additionally, gene regulation related to the signaling pathways also showed a similar trend, with increased expression of AAA-related genes in different Treg populations (Fig. 1H, J). From this, we can conclude that Tregs play a crucial role in regulating inflammatory responses and antigen presentation, being key to immune suppression.

Not only at the genetic level, but further assessments were made on the differential changes in transcription factors of Tregs to better evaluate their roles in blood and tissue (Fig. 2A, B). We further assessed cellular activity and found certain similarities between the AAA and normal groups (Supplementary Fig. 3A, B). We evaluated the Treg-specific marker transcription factor FOXP3, which belongs to the forkhead/winged-helix family, and found that it exhibits high expression and activity across different sources (Fig. 2C and Supplementary Fig. 3C). Several transcription factors with consistent regulatory roles, such as STAT1 (Fig. 2D), FOSB, and JUND, also exhibited high expression levels (Supplementary Fig. S3D, E). Despite observing a degree of transcriptional conservation, AAA patients exhibited an enrichment of immunosuppression-related transcription factors. For example, the transcriptional activity of IRF1 (Interferon Regulatory Factor 1), related to antigen presentation, was higher in AAA patients compared to the normal population. Its activity is regulated by inflammatory and cellular stress signals, affecting pathways such as MHC I and IFN-β. In cancer, IRF1 acts as a tumor suppressor, promoting apoptosis and inhibiting tumor cell proliferation (Fig. 2E). This suggests that this elevated trend plays a significant role in AAA, aligning with our communication results, including the co-elevation of blood-derived ETS1 (Fig. 2A). ETS1 regulates Treg cell function and stability, helping maintain immune system homeostasis and self-tolerance by interacting with other signaling pathways such as the TGF-β signaling pathway, preventing autoimmune diseases. This indicates that Tregs present in both blood and tissue exhibit coordinated regulatory mechanisms in AAA patients and the normal population, with some functional differences. In the AAA group, EZH2 was significantly active in blood-derived Treg cells, an enrichment not observed in the normal group (Fig. 2A, B). EZH2 is the catalytic subunit of the Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2), which is crucial for regulating gene expression. As a transcriptional repressor, EZH2 mediates the trimethylation of lysine 27 on histone H3 (H3K27me3), thereby suppressing gene expression (Fig. 2F). Additionally, the transcriptional repressor CREM also showed high expression levels (Supplementary Fig. 3F). These results suggest that Treg cells play a key role in regulating inflammatory responses, antigen presentation, and immunosuppression, especially demonstrating their significant biological functions and potential therapeutic targets in the progression of abdominal aortic aneurysms, laying a bioinformatics foundation for the development of TCR-Treg technology.

The heatmap of transcription factor enrichment in Tregs from AAA patients (A), the corresponding heatmap in normal controls (B), upregulated transcription factor FOXP3 extended in AAA, including AUC scores and gene set activity with enriched Ridgeplot (C), significant differences in antigen presentation-related STAT1 between AAA and normal groups, with detailed AUC scores and gene set activity visualized by Ridgeplot (D), IRF1 upregulated in AAA, including AUC scores and gene set activity with enriched Ridgeplot (E), and upregulated transcription factor EZH2 in AAA, including AUC scores and gene set activity with enriched Ridgeplot (F).

Comprehensive transcriptomic and single-cell sequencing analysis revealed immune and molecular signatures in AAA

The bioinformatic analysis was conducted as described previously. Using the limma package, differential analysis was performed on the data, resulting in a volcano plot for the differential genes between the AAA group and the control group. Among them, there were 624 upregulated genes and 395 downregulated genes in the AAA group (Fig. 3A). The GSEA enrichment analysis results indicate that the above differential genes are mainly enriched in inflammation-related pathways, such as “interferon alpha response,” “allograft rejection,” “oxidative,” “TNF-α signaling via NF-κB,” and “inflammatory response.”(Fig. 3B). The infiltration of 22 immune cell types was estimated using the R package CIBERSORT, and the correlation between VCAM-1 and the 22 immune cell types was analyzed using the Spearman method. A significant infiltration of T and B lymphocytes was revealed by the results of immune infiltration analysis. Further correlation analysis indicated a significant correlation between Treg cells and VCAM-1 within T lymphocytes (Fig. 3C, D). Classical biomarkers associated with apoptosis and inflammation, such as BAX, CASP1, CASP3, IL1β, TNF, MMP2, and MMP9, were chosen for comparative analysis between the two groups. Through transcriptomic sequencing analysis, it was found that these biomarkers were significantly upregulated in AAA (Fig. 3E). In the analysis of single-cell sequencing in AAA, principal component analysis results showed that cells in AAA were mainly clustered into the following cell populations, with VCAM-1 predominantly expressed in endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells (Fig. 3F, G).

Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes between the AAA group and the control group (A). The result of Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) indicated that the differentially expressed genes were mainly enriched in the inflammatory related pathways (B). Immune infiltration analysis shows significant infiltration of T and B lymphocytes (C). The correlation analysis results indicate a significant correlation between Treg cells and VCAM-1 in T lymphocytes (D). Correlation analysis reveals significant correlations between the expression of BAX, CASP1, IL1β, TNF, MMP2, MMP9, and VCAM-1 (E). The principal component analysis results indicate that VCAM-1 is primarily expressed in endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells (F, G).

Elevated level of T lymphocytes infiltration and increased VCAM-1 expression in human AAA tissue

According to the inclusion and exclusion criteria described in the methods, a total of 8 patient’s abdominal aortic aneurysm tissue and 8 specimens of normal human abdominal aorta were included. There were no differences in gender, age, comorbidities (such as hypertension, diabetes, coronary heart disease), smoking, and alcohol history between the two groups (P > 0.05). The baseline clinical data of both groups are shown in Supplementary Table 1. Through HE staining and EVG staining, the structural changes of the aortic wall and the degradation of elastic fibers were clearly demonstrated. Compared to healthy individuals’ aortic tissue, the degradation of elastic fibers in the aneurysmal wall tissue of AAA patients was significant (P < 0.001) (Fig. 4A–C). The presence of CD4+ T lymphocytes and VCAM-1 expression was detected using immunohistochemistry. Significant lymphocyte infiltration was observed in the aneurysm wall tissue of AAA patients (P < 0.001), and VCAM-1 expression levels were significantly higher in the aneurysm wall compared to the Control group (P < 0.001). (Fig. 4D–G). The relative expression level of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) was significantly lower in the AAA group compared to the Control group (P < 0.001), while the protein level of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) was significantly higher in the AAA group compared to the Control group (P < 0.01), as detected by WB analysis. Furthermore, the elevated expression of VCAM-1 in AAA patients was also validated through WB analysis (P < 0.01) (Fig. 4H–K). The TUNEL apoptosis staining method was employed to gain further insights into smooth muscle cell apoptosis in AAA tissues. Compared to healthy human aortic tissues, there was a significant increase in the proportion of apoptosis within the area where smooth muscle cells are situated in the aneurysmal wall of AAA patients (Fig. 4L, M).

HE staining (A) and EvG (B) staining images of normal human aorta and AAA aorta specimens (100× and 400× magnification); The elastin fiber fracture degradation score in human aneurysm specimens is significantly lower than that in healthy human aortic specimens (C); Immunohistochemical staining images of CD4 (D) and VCAM-1(E) in the aortic wall tissue of healthy individuals and AAA patients (100× and 400× magnification); Semi-quantitative analysis of CD4 (F) and VCAM-1 (G) immunohistochemical results in the aortic wall; Gel electrophoresis images illustrating the presence of VCAM-1, MMP-9, and α-SMA proteins in both healthy aortic tissues and those afflicted with AAA (H); Statistical representations delineating the expression profiles of VCAM-1 (I), MMP-9 (J), and α-SMA (K) proteins normalized to the reference gene GAPDH subsequent to independent replicated experiments; Fluorescent micrographs depicting apoptotic outcomes in the aortic wall tissues of healthy individuals and AAA patients using the TUNEL assay (L, 200× magnification); Semi-quantitative analysis of TUNEL immunofluorescence in arterial wall tissues from both groups (M). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

The expression levels of T lymphocytes and VCAM-1 were found to be increased in the aortic samples of AAA mice

The AAA model was induced in Rag1−/− mice by applying porcine pancreatic elastase to the exterior of the abdominal aorta. Compared to the Sham group, the diameter of the abdominal aorta in the AAA group expanded by more than 50% (Fig. 5A, B). HE staining revealed dilatation of the abdominal aortic lumen, thickening of the outer membrane, and extensive immune cell infiltration in the AAA group (Fig. 5C). EvG staining demonstrated evident disruption/fracture of elastic fibers in the AAA tissues (Fig. 5D, P < 0.001). These alterations are consistent with the fundamental pathological characteristics of AAA. The animal model was successfully established (Fig. 5A–D). The expression of lymphocytes (CD4) and VCAM-1 in mouse aortas was detected using the method of immunohistochemical staining. An obvious infiltration of lymphocytes (Fig. 5E, F , P < 0.001) and a significant increase in the expression level of VCAM-1 (Fig. 5G, H, P < 0.001) were observed in the aneurysmal wall tissue of the AAA group compared to the Sham group. In comparison to the Sham group, it was observed that the expression level of α-SMA was significantly reduced (Fig. 5I, L, P < 0.05), and the protein level of MMP-9 was markedly increased (Fig. 5I, K, P < 0.05) in the AAA group as detected by WB. The high expression of VCAM-1 in the abdominal aortic aneurysm wall tissue of AAA mice was confirmed by Western Blot (Fig. 5I, J, P < 0.001). TUNEL staining was used to clarify smooth muscle cell apoptosis in mouse AAA tissues, Results showed a significant increase in apoptotic index in AAA mice compared to Sham (P < 0.001) (Fig. 5M, N).

Representative images (A) and aortic diameter (B) of abdominal aorta from each group. HE and EvG staining images of aorta in Sham and AAA groups of mice (C 100× and 400× magnifications); Semi-quantitative statistical graph of the degree of elastic fiber fracture in the aortic wall (D); Immunohistochemical staining results of CD4 (E) and VCAM-1 (G) in the aortic tissues of mice from the Sham group and AAA group (100× and 400× magnification); Semi-quantitative analysis of CD4 (F) and VCAM-1 (H) immunohistochemical results in the aortic wall; Gel electrophoresis images illustrating the presence of VCAM-1, MMP-9, and α-SMA proteins (I) in both healthy aortic tissues and those afflicted with AAA; Statistical representations delineating the expression profiles of VCAM-1 (J), MMP-9 (K), and α-SMA (L) proteins normalized to the reference gene GAPDH subsequent to independent replicated experiments; Fluorescent images of apoptosis in mouse aortic wall tissues detected by TUNEL assay (M, 200× magnification); Semi quantitative analysis of TUNEL immunofluorescence in arterial walls of two groups (N). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

CAR-Treg cells maintain normal secretion of IL-10 and TGF-β

We isolated Treg cells from peripheral blood of both healthy individuals and AAA patients (Supplementary Fig. 4A). The sorted cells were analyzed using flow cytometry. After 24 h of cultivation and expansion, clonal clusters of cells emerged (Supplementary Fig. 4B). Peripheral blood Treg cells entered the logarithmic growth phase on days 8–10 (Supplementary Fig. 4C). RNA was isolated from actively growing normal human Treg cells and Treg cells from patients with AAA. PCR was utilized to assess the mRNA expression levels of IL-10 (Fig. 6A) and TGFB (Fig. 6B). Additionally, ELISA was employed to quantify the concentrations of IL-10 and TGF-β in the supernatant of Treg cell cultures derived from both healthy individuals and AAA patients. The mRNA levels of IL-10 (Fig. 6C) and TGFB (Fig. 6D) were notably diminished in Treg cells from AAA patients in comparison to those from healthy individuals (P < 0.001; P < 0.01), paralleled by significantly reduced cytokine concentrations (P < 0.001; P < 0.001). In this study, we achieved the successful construction of CAR-Treg cells aimed at targeting VCAM-1, a pivotal molecule implicated in the pathogenesis of abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA). Utilizing a lentiviral vector harboring the specific scFv against VCAM-1, Treg cells were genetically modified to express the chimeric antigen receptor6. This modification aimed to enhance the specificity and functionality of Treg cells in modulating immune responses within the AAA microenvironment. CAR-Treg cells targeting VCAM-1 were constructed by transfecting cells with a lentiviral vector targeting VCAM-1. Within 48–72 h post-transfection, green fluorescent protein (GFP) began to be expressed in the cells. The expression of GFP was observed under a fluorescence microscope, and transfection efficiency reaching 60% was confirmed by flow cytometry (Fig. 6E–I) and Western blotting (Fig. 6J), indicating successful construction of VCAM-1-targeting CAR-Treg cells (Fig. 6K, L). The constructed CAR-Treg cells and untransfected Treg cells were cultured and expanded separately. Cell counts were performed, and growth curves were plotted, revealing no significant difference in proliferation rates between the groups (Fig. 6M). PCR was conducted to detect the mRNA levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 (Fig. 6N) and TGFB (Fig. 6O), and ELISA was used to measure the concentrations of IL-10 (Fig. 6P) and TGF-β (Fig. 6Q) in the cell culture supernatants. The results showed no statistical difference between the two groups (P > 0.05). We believe that during the cell culture stage, there is no distinction in functionality between CAR-Treg cells and Treg cells.

Results of PCR analysis showing mRNA levels of IL-10 (A) and TGFB (B) in Treg cells from healthy individuals and AAA patients; Discrepancies in IL-10 (C) and TGF-β (D) concentrations in culture supernatant of Treg cells from normal human and AAA patients as detected by ELISA; GFP expression was observed under bright-field and fluorescence microscopy 72 h post-transfection (E); Flow cytometric analysis confirmed transfection efficiency at 60% (F–H); Statistical analysis of transfection efficiency was performed through repeated experiments (I); Western blotting detected GFP protein expression in CAR-Treg cells (J); The expression level of FOXP3 (K) and GFP (L) in the CAR-Treg cell group; Growth curves of CAR-Treg cells and Treg cells (M); Statistical analysis of PCR results for mRNA levels of IL-10 (N) and TGFB (O) in CAR-Treg cells and Treg cells; Differential concentrations of IL-10 (P) and TGF-β (Q) in the culture medium of CAR-Treg cells and Treg cells were detected by ELISA. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

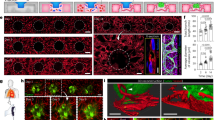

CAR-Treg cells targeted AAA mice arterial walls successfully

The AAA (A), AAA + Treg (A + T), and AAA + CAR-Treg (A + C) groups were imaged together using an in vivo small animal imaging system. In the A group, no positive signals were observed during imaging. In the A + T group, distinct positive signal areas appeared in the upper abdomen, which gradually weakened and disappeared by the 14th day. In the A + C group, positive signals of lower intensity than those in the A + T group appeared in the middle of the upper abdomen, and by the 14th day, the original positive signal intensity decreased, with spindle-shaped positive signals appearing below it. On the 14th day, major organs including the liver, heart, lungs, kidneys, aorta, and spleen were imaged in 6 cm cell culture dish. In the A group, no positive signals were detected, while in the A + T group, positive signals appeared successively in the liver, spleen, and kidneys. In the A + C group, positive signals were observed successively in the liver, spleen, and aorta. Comparison among the three groups indicated that the CAR-Treg group exhibited positive signals targeting the aorta. When the three groups of blood vessels were placed in the same 6 cm cell culture dish for imaging again, it was clearly observed that the CAR-Treg group had relatively high-intensity positive signals. This suggests that CAR-Treg cells successfully targeted the tissue of the abdominal aorta in mice (Fig. 7A–C). Compared to the sham group, the diameter of the abdominal aorta in the AAA group expanded by more than 50%. The diameter in the AAA + Treg and AAA + CAR-Treg groups were significantly smaller than that in the AAA group (P < 0.001), and the diameter in the AAA + CAR-Treg group was smaller than that in the AAA + Treg group (P < 0.01) (Fig. 7D, E). The results of HE staining revealed an augmentation in luminal diameter of the abdominal aorta, accompanied by thickening of the outer membrane and notable infiltration of immune cells in both the AAA group, AAA + Treg group, and AAA + CAR-Treg group. EvG staining displayed a pronounced disruption of elastic fibers within AAA tissue (P < 0.001). These alterations corresponded with the fundamental pathological features of AAA. Notably, the severity of elastic fiber disruption in the AAA + CAR-Treg group appeared less pronounced compared to both the AAA group and AAA + Treg group (Fig. 7F, G). Immunohistochemical staining of arterial tissues in each group was performed to assess the expression of the inflammatory cytokine (IL-17a), T cells infiltrate (CD3), macrophages (F4/80), and neutrophils marker (ELA2) in the different aorta tissues. A high level of IL-17a, CD3, F4/80 and ELA2 expression was observed in all three AAA groups compared to the Sham group (P < 0.001), as depicted in the Fig. 7H, J, L, N. Furthermore, based on the scoring results of immunohistochemical staining, it was found that the expression levels of IL-17a CD3, F4/80 and ELA2 in the AAA + Treg group and AAA + CAR-Treg group were significantly lower than those in the AAA group (P < 0.001). Additionally, the expression level of IL-17a (Fig. 7H, I) and CD3 (Fig. 7J, K) in the AAA + CAR-Treg group was significantly lower than that in the AAA + Treg group. However, no significant difference was observed in the expression levels of F4/80 (Fig. 7L, M) and ELA2 (Fig. 7N, O) between the AAA + CAR-Treg group and the AAA+Treg group. These findings suggest that the CAR-Treg treatment more effectively reduces T cell infiltration (CD3) and the inflammatory cytokine IL-17a compared to Treg treatment alone, highlighting a potentially superior immunomodulatory effect of CAR-Tregs in mitigating inflammation in AAAs.

Imaging results on days 1, 5, 9, and 14 after cell injection for groups A, A + T, and A + C (A); Imaging of major organs (liver, heart, lung, kidney, aorta, spleen) on day 14 after cell injection, placed in 6 cm culture dish showing positive signal distribution (B–I); Corresponding organs numbered as follows: 1-liver, 2-heart, 3-lung, 4-kidney, 5-aorta, 6-spleen (B-II); Imaging of the aortas of the three groups on day 14 after cell injection in 6 cm culture dish showing positive signal distribution (C); Representative images of aorta from each group (D); Statistical graph of maximum aortic outer diameter, following CAR-Treg cell therapy (E), the diameter of mouse AAA decreased significantly (Sham, N = 6; AAA, N = 6; AAA + Treg, N = 6; AAA + CAR-Treg, N = 6); The HE and EvG staining images of mouse aortas from each group (F, 100× and 400× magnification); Semi-quantitative analysis of elastic fiber rupture in the arterial wall (G); Immunohistochemical staining of arterial tissues for four different intervention or treatment strategies, IL-17a (H), CD3 (J), F4/80 (L) and ELA2 (N) expression was observed 100× and 400× magnification, and scoring results of immunohistochemical staining for IL-17a (I), CD3 (K), F4/80 (M) and ELA2 (O). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

The presence of apoptotic cells in the intimal-medial region of the aneurysmal wall was observed in the AAA group, AAA + Treg group, and AAA + CAR-Treg group compared to the Sham group (P < 0.001). Furthermore, it was noted that the degree of apoptosis in the AAA + CAR-Treg group was less than that in the AAA + Treg group (P < 0.001) (Fig. 8A, B). Through Western Blot detection, it was found that compared to the AAA group, significant decreases in the expression levels of MMP-9, IL-17a, Caspase-3, BAX, and COX-2 were observed in both the AAA + CAR-Treg cell therapy group and the AAA + Treg cell therapy group, with a significant increase noted in the expression level of α-SMA in the AAA + CAR-Treg cell therapy group. When compared to the AAA + Treg group, significant decreases in the expression levels of MMP-9, IL-17a, Caspase-3, BAX, and COX-2 were observed in the AAA + CAR-Treg cell therapy group, along with a significant increase in the expression level of α-SMA (Fig. 8C–J).

TUNEL apoptosis staining results images of mouse aortic tissues from each group (A, 200×); Semi-quantitative analysis of TUNEL apoptosis staining results in aortic walls (B); Protein gel electrophoresis images of aortic tissue from each group of mice (C); Bar graphs showing the relative expression levels of VCAM-1 (D), MMP-9 (E), α-SMA (F), Caspase-3 (G), COX-2 (H), IL-17a (I), and Bax (J) proteins normalized to the internal reference GADPH after independent replicate experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Discussion

AAA remains a major public health issue over the world14. Despite surgical advances, there is a lack of effective nonoperative therapies limiting AAA progression for those non-operation indicated patients21. The findings of our study for the first time underscore the therapeutic potential of CAR-Treg cell immunotherapy targeting VCAM-1 in the management of AAA. Through a multifaceted approach integrating bioinformatics analyses, preclinical experimentation, and molecular characterization, we have elucidated crucial insights into the mechanistic basis and therapeutic efficacy of this innovative immunotherapeutic strategy. The observed deficiency in Treg numbers and function in AAA patients aligns with previous reports6,22,23 and highlights the dysregulated immune response implicated in AAA pathogenesis24. Our study addresses this immunological aberration by harnessing the immunomodulatory potential of CAR-Treg cells, specifically engineered to target VCAM-1, a key molecule implicated in AAA mechanisms.

AAA development is characterized by a prominent CD4+ T-cell inflammation25. Tregs serve as an important component of the immune system responsible for the maintenance of immunologic homeostasis and inhibition of excessive inflammatory infiltration26. Our previous studies have shown an association between AAAs and impaired immunoregulation by Tregs22,23. Furthermore, recent animal studies have revealed that Treg manipulation can influence AAA formation and inflammation, and demonstrated a critical role of Tregs in regulating AAA expansion6,10. Thus, these preclinical studies support the conception that therapy directed toward Treg function or quantity may provide an effective strategy for the prevention of AAA development. One major challenge is the optimal method to provide this therapy. Despite the methods to expand Treg population by selective cytokine IL-2 or by systemic injection were successful, their off-target effects like systemic immunosuppression et al. remain uncertain8,27 Adopting the principle of CAR-T in cancer treatment, a groundbreaking immunotherapeutic modality of a revolutionized treatment by endowing T lymphocytes with enhanced antigen specificity and cytotoxicity to cancer cells, chimeric antigen receptor- engineered Treg targeting specific antibody was designed28, engineered and generated in present study with expectation of its more efficiency and less side-effect29. However, selection of the targeting antibody is pivotal to the whole experiment.

VCAM-1 is a type I transmembrane protein expressed in activated endothelial cells and vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), and it plays a role in the adhesion and migration of inflammatory cells to damaged tissues, serves as a widely utilized biomarker for promoting inflammation30. An alternative therapeutic strategy for AAA involves targeting endothelial adhesion molecules, such as VCAM-1, which plays a critical role in leukocyte recruitment and vascular inflammation. Wang et al. demonstrated that miR-126, a microRNA known to regulate VCAM-1 expression, can be used to suppress this adhesion molecule and effectively reduce the inflammatory response in AAA. Their study utilized a theranostic approach by delivering miR-126 mimics via ultrasound-targeted microbubbles, which enhanced the localized effect of the therapy and minimized off-target effects. This approach could serve as a complementary strategy to our use of CAR-Treg cells, providing a non-invasive method for targeting the inflammatory processes involved in AAA development19. By focusing on VCAM-1, our study targets a key molecular player in the inflammatory cascade, aiming to disrupt the cycle of immune cell infiltration and subsequent tissue degradation within the aneurysmal wall. Our experiments have revealed that VCAM-1 is significantly overexpressed in both human and murine AAA tissues, which has been confirmed by other studies. Previous reports have shown that, compared to control groups, in murine AAA models, co-localization staining of VCAM-1 with VSMCs revealed a higher proportion of VSMC-associated VCAM-1 than endothelial cell-associated VCAM-1 (more than threefold)31. This observation is similar to what was previously observed in rabbit atherosclerotic vascular models, where VSMC-expressed VCAM-1 may facilitate the recruitment and retention of inflammatory cells within the arterial wall32. Recent research has indicated that VCAM-1 exhibits specific expression in vascular diseases and may serve as a potential therapeutic target for vascular disorders17. In the analysis of the correlation of differentially expressed genes bioinformatics, we found that among T cells, the correlation between Tregs and VCAM-1 was the most significant, suggesting that Treg cells may modulate immune responses and inflammatory reactions through interactions with VCAM-1, and the expression of VCAM-1 may also affect the migration of Treg cells. Thus, utilizing a comprehensive methodology encompassing bioinformatics, immunohistochemistry, and various molecular techniques, we delved into the intricate dynamics between Treg cells, VCAM-1 expression, and AAA development. The successful targeting and infiltration of CAR-Treg cells into AAA tissue mark a significant advancement in the application of engineered immunotherapy for vascular diseases. This success is attributed to the precise engineering of Treg cells to recognize and bind to VCAM-1, enabling their accumulation in inflamed vascular tissues where VCAM-1 is upregulated. The localized suppression of inflammation by these targeted Treg cells could herald a new era in AAA management, focusing on biological therapy tailored to the disease’s underlying mechanisms rather than symptomatic treatment or mechanical intervention alone. By directing CAR-Treg cells to areas of VCAM-1 expression within the AAA tissue, this study pioneers a targeted approach to immunomodulation, precisely where the inflammatory processes are most active. This strategy not only amplifies the potential therapeutic impact of Treg cells but also minimizes systemic immunosuppression risks, offering a safe and more focused intervention33. This localized immunosuppression is pivotal in curtailing the vicious cycle of inflammation, extracellular matrix degradation, and smooth muscle cell apoptosis that characterizes AAA progression.

Our application of the lentiviral vector is identical to the second-generation CAR structure already on the market, with its stability and clinical safety duly established. The single-chain variable fragment (scFv) targeting VCAM-1 is derived from an open patent research outcome34, the scFv sequence targeting VCAM-1 utilized in our study originates from a human monoclonal antibody known for its specific binding to VCAM-1, exhibiting strong affinity towards VCAM-1 expressed on endothelial cells in both human and murine subjects35, while also demonstrating low immunogenicity, which specificity has been thoroughly affirmed. Notably, the selected scFv exhibits targeting efficacy towards both human and murine subjects, facilitating its utility in both scientific research and laying the groundwork for subsequent clinical trials. In the construction of VCAM-1-CAR-Treg, we employed a two-step lentiviral transduction method to enhance transduction efficiency, ensuring it remains above 60%. Furthermore, the utilization of small animal in vivo imaging system further validated the specificity of VCAM-1-CAR-Treg targeting in animal experiments.

Cell-based therapy has emerged as a promising approach for treating cardiovascular diseases36. Due to the regenerative properties of stem cells, cellular therapy has garnered increasing attention. In animal experiments, researchers have evaluated several cell types in the mouse model of AAA, among which mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have been studied most extensively. It is noteworthy that MSCs derived from adipose tissue of AAA patients exhibit a significant aging trend37. Studies have found that mesenchymal stem cells can induce vascular repair responses, resulting in restricted progression of mouse AAA. This effect may be attributed to the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines, secretion of extracellular vesicles with immunomodulatory characteristics, and paracrine responses mediated by VSMC contractile phenotype. Although there are numerous reports of MSCs migrating to the arterial wall in these studies, evidence regarding their differentiation into vascular smooth muscle cells or endothelial cells is limited. Currently, the prevailing view is that their paracrine-mediated effects serve as the basis for suppressing AAA development.

As mentioned earlier, there is a phenomenon of decreased expression of FOXP3 in peripheral blood CD4+CD25+ Treg cells, accompanied by a reduction in the number of CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ T cells, leading to an overall deficiency in CD4+CD25+ Treg function38,39. Furthermore, there are numerous cases in animal experiments where the adjustment of Treg cell number or function suppresses the development of AAA. However, the method of directly infusing large amounts of Treg cells in vitro also faces a challenge. While the use of conventional cell transfer methods shows great potential in the treatment of immunosuppressive diseases or graft-versus-host disease, direct large-scale use of ex vivo cultured cells still poses certain safety risks, such as causing systemic immune suppression40,41. The CAR-Treg technology we employ has shown great potential in various animal disease models, and antigen-specific Treg cells, especially CAR-Treg cells, are generally believed to have superior inhibitory effects compared to polyclonal Treg cells11. Treg cells must migrate to the site of lesions to exert their inhibitory effects. CAR-Treg cells achieve self-activation and proliferation through recognition of antigens specifically expressed at the disease site. They inhibit local inflammation through cell contact and secretion of cytokines, resulting in better efficacy, higher safety, and fewer adverse reactions. CAR-Treg therapy represents a highly promising next-generation immunosuppressive therapy. However, it is worth mentioning that a specific issue pertains to this treatment’s specificity of targeting.

Besides, several important considerations warrant discussion. Firstly, the long-term safety and efficacy of CAR-Treg cell therapy in AAA management remain to be elucidated through comprehensive translational studies. Additionally, optimization of CAR-Treg cell manufacturing protocols and refinement of targeting strategies are imperative to enhance therapeutic outcomes and minimize off-target effects. Secondly, while our study demonstrates the potential of VCAM-1 CAR Treg in influencing aortic remodeling in AAA, the observed therapeutic effects are modest. As highlighted by the reviewer, the differential impact of VCAM-1 CAR Treg compared to control Treg on aortic diameter is minimal, which may limit its clinical applicability. Additionally, while we focused on a 14-day post-infusion period, the duration of the CAR Treg effect remains unclear, and further studies are needed to assess longer-term outcomes. Furthermore, while the elastase model offers significant advantages in terms of mimicking aspects of human AAA, it is important to note several limitations that may bias our findings, lack of human-like immune responses, the Rag1−/− mouse model lacks functional T and B cells, which are important in human AAA pathology. While this allows us to study the direct impact of Tregs in isolation, the absence of these immune cells means the model does not fully replicate the complex immune environment of human AAA, where both innate and adaptive immune responses play key roles. Finally, we recognize that lipid metabolism and atherosclerosis are also key components in the pathogenesis of AAA, ApoE-deficient mice, when subjected to AngII infusion, are a well-established model for atherosclerosis and AAA, particularly due to the significant overlap in the immune responses and lipid metabolism observed in these models. Incorporating this model would allow us to better examine the synergistic effects of immune modulation and lipid metabolism in AAA development, providing more comprehensive insights into the disease’s pathology. The CAR-Treg technology has shown significant effects in animal models of diseases such as graft-versus-host disease, diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, inflammatory diseases, asthma, vitiligo, hemophilia, and others42. Based on our previous research on the functional deficiency of Treg cells in the peripheral blood of AAA patients, we have constructed Treg cells with specificity for AAA targets in this experiment22. In vivo experiments in mice have confirmed the targeting ability of these CAR-Tregs and validated their effective therapeutic effects. Our team is also the first in the world to construct and apply CAR-Tregs for the treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysms in mice. Our research findings indicate that this method can effectively reduce the proportion of inflammatory infiltration and smooth muscle cell apoptosis in mouse AAA, thereby delaying the progression of AAA. This targeted therapeutic approach may serve as a novel strategy for treating AAA.

Conclusion

CAR-Treg cells targeting VCAM-1 present a promising novel therapeutic approach for AAA management. By leveraging the immunomodulatory potential of Treg cells and the pivotal role of VCAM-1 in vascular inflammation, this research lays the groundwork for novel interventions that could significantly alter AAA’s clinical management. The implications of these findings extend beyond AAA, offering insights into the broader application of immunotherapy in vascular and autoimmune diseases.

Methods

This study was performed according to the Guidelines of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local ethics committee of the China Medical University. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the First Hospital of China Medical University (ethical approval number: [2021]134). All animal experimentation approved by the Ethics Committee for Animal Experimentation of China Medical University. We have complied with all relevant ethical regulations for animal use.

Collection of human aorta tissue specimens and peripheral blood

This study prospectively recruited patients diagnosed with abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) at the Department of Vascular Surgery, First Hospital of China Medical University, between September 1, 2021, and March 1, 2022 as previous study43. Additionally, normal abdominal aorta specimens from age- and gender-matched organ donors were obtained from the Department of Organ Transplantation, First Hospital of China Medical University. This study was performed according to the Guidelines of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local ethics committee of the China Medical University. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the First Hospital of China Medical University (ethical approval number: [2021]134), and informed consent was obtained from the families of all organ donors. Inclusion criteria for AAA patients were: 1. A definite diagnosis of abdominal aortic aneurysm after a full aortic CTA examination; 2. Complete medical records and corresponding auxiliary examinations. Exclusion criteria for AAA patients were: 1. Inflammatory abdominal aortic aneurysm; 2. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome; 3. Marfan syndrome; 4. History of endovascular repair for aortic dissection or abdominal aortic aneurysm; 5. Other known genetic vascular or connective tissue diseases; 6. Cancer; 7. Infection; 8. Concurrent autoimmune diseases or receiving immunosuppressive or modulating therapy: psoriasis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Behcet’s disease, atopic dermatitis, ulcerative colitis, etc. Preoperatively, peripheral blood samples were collected from AAA patients in fasting state using purple anticoagulant tubes. Control group patients were selected from a healthy population matched for age and gender. After collection, the samples were stored in a refrigerator at 4°C for later use.

Materials

Antibodies against α-SMA (alpha smooth muscle actin; ab5694), MMP-9 (ab58803), and VCAM-1 (ab37150) were procured from Abcam, United Kingdom. GAPDH Antibody, IL-17A, GFP tag Monoclonal antibody, COX-2, BAX, and Caspase-3 were obtained from Proteintech, China. The ScFv (VCAM-1)-2ndCART lentiviral vector was sourced from Shanghai Genechem Co., Ltd., China. For the isolation of Treg cells, CD4+ T lymphocytes were enriched using the mouse CD4+ T lymphocytes isolation kit (Miltenyi, Germany).

Bioinformatics

Transcriptomic Data Analysis from GEO Database: Transcriptomic data were retrieved from the publicly available GEO database, specifically the GSE232911 dataset, comprising 26 samples of healthy human abdominal aortic tissues and 220 samples of abdominal aortic aneurysm tissues. Differential Analysis using the limma Package: Differential analysis was conducted using the limma package. Initially, normalization and correction of data from different samples were performed. Subsequently, an inter-group comparison matrix was constructed. The lmFit function was employed for linear model fitting, followed by the application of the eBayes function for Bayesian testing. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA): Gene Set Enrichment Analysis was executed using the clusterProfiler package, with the hallmark gene set (c2.cp.kegg.v7.1.symbols.gmt) serving as the reference dataset. Immunoinfiltration Analysis: CIBERSORT, an R package, was utilized to estimate the infiltration levels of 22 immune cell types. Following this estimation, the Spearman method was applied to analyze the correlation between VCAM-1 and the 22 immune cell types.

Single-cell RNA sequencing

First, for abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) tissue, we performed single-cell sequencing on samples from 7 patients. Correspondingly, for normal abdominal aortic tissue, we obtained samples from 6 organ transplant donors for single-cell sequencing. Additionally, we selected peripheral blood samples from 5 out of these 7 AAA patients for single-cell sequencing. Sequencing was performed on RNA. As a control for peripheral blood, we compared and analyzed the single-cell sequencing data from peripheral blood samples of 6 normal individuals from the public dataset GSE235857. In this study, the freshly collected tissue samples were washed with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and stored in the preservation solution (SeekOne, China) for freezing within 30 min after surgery. The perivascular connective tissue and adipose tissue were meticulously excised. For each sample, a piece of aortic tissue (1–2 cm2) was separated into thin layers and cut into small pieces in DMEM (Gibco, USA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Then, the small pieces of tissue were placed into SeekOne digestion solution (SeekOne, China) for 30–45 min, which mainly contained collagenase type II (Sigma, USA), collagenase type IV (Sigma, USA), Seekone protease E (SeekOne, China), SeekOne protease G (SeekOne, China), SeekOne protease H (SeekOne, China), hyaluronidase type I (Sigma, USA), and Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS, Sigma, USA). After 2–3 rounds of digestion in a 37 °C water bath, the tissue was completely digested. Then, we filtered the cells with a 70-μm cell filter and centrifuged them at a speed of 300–400 × g at 4 °C for 5–6 min. After removing erythrocytes (Miltenyi, USA), the decision to perform debris and dead cell removal was made (Miltenyi, USA). Cell count and viability were estimated using the fluorescence Cell Analyzer (Countstar® Rigel S2) with AO/PI reagent serum albumin. Finally, the fresh cells were washed twice in DMEM and then resuspended at a concentration of 1 × 105 cells per ml in HBSS and 2% FBS. We utilized SeekGene’s SeekOne® MM Single Cell 3’ library preparation kit to construct scRNA-seq libraries with improved efficiency and reduced duplication rate. We began by loading the appropriate number of cells into the flow channel of the SeekOne® MM chip, containing 170,000 microwells, using gravity to aid cell settling. After allowing sufficient time for settling, any remaining unsettled cells were carefully removed. To label individual cells, we employed Cell Barcoded Magnetic Beads (CBBs), which were pipetted into the flow channel and precisely localized within the microwells using a magnetic field. Subsequently, we lysed the cells within the SeekOne® MM chip, releasing RNA that was captured by the CBBs in the same microwell. Reverse transcription was performed at 37 °C for 30 min to synthesize cDNA with cell barcodes. Exonuclease I treatment was used to eliminate any unused primers on the CBBs. The barcoded cDNA on the CBBs then underwent hybridization with a random primer containing a Reads 2 SeqPrimer sequence at its 5’ end, facilitating the extension and creation of the second DNA strand with cell barcodes at the 3’ end. After denaturation, the resulting second strand DNA was separated from the CBBs and purified. The purified cDNA product was amplified through PCR, and unwanted fragments were removed through a clean-up process. Full-length sequencing adapters and sample indexes were added to the cDNA through an indexed PCR. Indexed sequencing libraries were further purified using SPRI beads to remove any remaining impurities. Quantification of the libraries was performed using quantitative PCR (KAPA Biosystems KK4824). Finally, the libraries were sequenced using either the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform with PE150 read length or the DNBSEQ-T7 platform with PE100 read length. The resulting gene-cell expression matrix was utilized for further analysis in Seurat within R version 4.3.1. Cells were screened based on the following criteria: gene counts ranging between 200 and 7000, UMI counts below 30,000, and exclusion of cells with more than 10% mitochondrial content. Subsequently, Seurat’s Clustree function was used to evaluate the relatively suitable resolution, the FindClusters function was implemented with a clustering analysis resolution parameter of 0.5. The resulting clusters were visualized using either t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) or Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP). Each cluster was annotated with a cell type using known marker genes. Finally, Seurat’s FeaturePlot and VlnPlot functions were used to visualize the expression of specific genes in our analysis. The scRNA-seq data were uploaded to the National Genomics Data Center (NGDC) database from China National Center of Bioinformation (accession number HRA011745).

Establishment of the AAA model

7-week-old male Rag1−/− (C57BL/6J background) mice were purchased from Suzhou Cyagen Biotechnology Co., Ltd., with a weight range of 14–17 g. They were housed in the SPF-grade animal facility at the Animal Experimental Center of China Medical University, with temperature fluctuations between 20 and 26 °C and relative humidity fluctuations between 50 and 70%. The light-dark cycle was set at 12 h interval, and they were provided with regular drinking water and maintenance feed. The housing environment and experimental protocols for the mice complied with the “Regulations for the Use and Management of Laboratory Animals at China Medical University”, and were approved by the Ethics Committee for Animal Experimentation of China Medical University. After one week of adaptive growth, mice were fed with 5% Bayluscide water for 3–4 days. Each mouse was irradiated under an X-ray biological irradiator with a total dose of 300 rad. At least 4 h after irradiation, each mouse was given 5 × 106 CD4+ T lymphocytes (sourced from healthy human peripheral blood) via the tail vein. After 3 more days of feeding, the AAA model in Rag1−/− mice was induced using the method of external application of porcine pancreatic elastase6 (Supplementary Fig. 5A–F).

Aortic tissue collection and histopathologic analysis

At the end of each animal experimental protocol, animals were euthanized, and the vascular tree was carefully exposed and dissected by laparotomy. The images of the mouse aorta samples were captured and recorded using a small animal dissection microscope (Beijing Tiannuoxiang Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). The aorta tissues were isolated and positioned under the microscope, and images were captured to observe changes in aortic morphology and diameters. Abdominal aorta tissues were collected and processed, followed by histopathologic analysis Briefly, the aorta was fixed with 10% formalin for 48 h at room temperature before being embedded in paraffin for sectioning. Cross sections (5.0 µm) were collected at the maximal diameter of the abdominal aorta. One or two sections from each location were subjected to HE staining and elastin van Gieson staining, respectively. Degradation of medial elastic lamina was analyzed by Elastin van Gieson (EvG) staining using Elastic Stain Kit as per manufacturer instructions. Images were taken and elastin breaks (fragmentation) per section were manually counted by 2 experienced investigators blinded to the treatments.

Aortic tissue immunohistochemical staining

The procedure for immunohistochemical staining of the abdominal aorta is outlined as follows: Paraffin-embedded sections of the abdominal aorta were deparaffinized with xylene and subsequently rehydrated with ethanol. Following rinsing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), antigen retrieval was carried out using a sodium citrate solution for 3 min. Endogenous peroxidase activity and non-specific staining were blocked using inhibitors, after which the primary antibody was incubated overnight at 4 °C. On the subsequent day, slides were cleaned, and a biotinylated IgG polymer and streptavidin-peroxidase conjugate were sequentially applied, followed by DAB staining. Hematoxylin staining and differentiation with a hydrochloric acid alcohol solution were then performed. Slides were subsequently dehydrated using an ethanol gradient and cleared with xylene. Finally, the slices were stained according to routine methods and photographed under a light microscopy. Two experienced researchers, blinded to the conditions, utilized Image J Pro software to determine the average intensity of positive expression of the target protein on each slide. Three sections were analyzed per vessel sample and results were averaged.

CD4+ T lymphocytes and Treg cell isolation

Applying the Human CD4+ T lymphocytes Sorting Kit and the Human Treg Cell Sorting Kit for the sorting of human CD4+T lymphocytes and human Treg. After sorting, the cells were cultured at a density of 106 cells/ml in 1640 medium supplemented with 1% penicillin/streptomycin.

Lentivirus generation and transfection

Lentiviral vectors targeting VCAM-1 with green fluorescent protein (GFP) were provided by Genechem (Shanghai, China). Individual scFv targeting VCAM-1 is derived from synthesized and screened via phage display libraries. In order to enhance the transfection efficiency, a 24-well plate (untreated surface) was precoated with RetroNectin. The logarithmic growth phase of Treg cells was selected and transfected using the recommended transfection volume at an MOI of 3 according to the instructions. The transfection was performed through a well plate secondary transfection method was adopted. After transfection for 72 h, GFP expression was observed by fluorescence microscopy, and the transfection efficiency was further confirmed by flow cytometry analysis. Finally, GFP expression was verified by Western blotting experiment (Supplementary Method).

In-vivo monitoring of Treg and CAR-Treg cell distribution in an AAA mouse model using DiR fluorescent staining

A deep-red cell membrane fluorescent probe solution (DiR Iodide cell membrane deep-red fluorescent probe, Shanghai Yeasen Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) was prepared using PBS. Expanded Treg cells and CAR-Treg cells were collected and centrifuged at 300 × g for 5 min at room temperature. The cells were resuspended in an appropriate volume of the staining working solution to achieve a cell density of 1 × 106 cells/ml and incubated at 37 °C for 20 min. After incubation, the cells were centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 5 min, and the supernatant was discarded. The cells were gently resuspended in pre-warmed growth medium at 37 °C, centrifuged again, and the supernatant discarded. Finally, the cells were resuspended in PBS to adjust the density to 1 × 107 cells/ml. On Day 14 after the establishment of the AAA model, a single-use sterile insulin syringe was used to inject 200 µl of PBS into the tail vein of mice in the AAA group, 200 µl of stained Treg cells into the AAA+Treg group, and 200 µl of stained CAR-Treg cells into the AAA + CAR-Treg group. The three groups of AAA mice were imaged on Days 1, 5, 9, and 14 after injection using an in-vivo imaging system (Kodak In-vivo Imaging System FX Pro, Bruker Corporation, Germany). This small animal imaging system was used to monitor the accumulation and distribution of DiR-stained cells in the body. Stronger fluorescence signals indicated higher accumulation of stained cells at specific sites such as the aorta and major organs. The imaging parameters were set as follows: excitation wavelength 720 nm and emission wavelength 780 nm. On Day 14, the major organs and aortas were excised and imaged ex-vivo in a 6-cm cell culture dish for further analysis. The positive signals observed represent the fluorescently labeled Treg and CAR-Treg cells. The cells were stained with the DiR Iodide probe, which integrates into the cell membrane, producing a deep-red fluorescence detectable by the in-vivo imaging system. The intensity of the fluorescence corresponds to the accumulation of the cells at specific sites, such as the aorta, reflecting the distribution and retention of the cells over time in the various experimental groups.

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was extracted from human Treg cells using Trizol reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions and subjected to DNase I digestion to remove potential DNA contamination. cDNA was reversely transcribed from total RNAs using an Improm-II RT kit with RNase inhibitor and Random primers and diluted to a working concentration of 5 ng/µL. FS UNIVERSAL SYBR GREEN MASTERROX was used in RT-qPCR. RT-qPCR was performed on the CFX Connect Real-Time PCR Detection System or Light Cycler 480 Instrument for 96-well plates, respectively, using SYBR Green RT-qPCR master mix. The cycle threshold values were obtained using CFX Manager Software or Light Cycler 480 software and later analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCTmethod to determine relative changes in gene expression across all samples. Relative mRNA expression level was defined as the ratio of target gene expression level to 18S expression level, with that of the control sample set as 1.0. Primers were designed using the Primer Express software, and the sequence for each primer was listed in Supplementary Table 3.

Western blot analysis

Equal amount of protein was separated by SDS-PAGE with 10–12% Tris-glycine gel and subjected to standard Western blot analysis. The blots were subjected to densitometric analysis with the Image J software. Relative protein expression level was defined as the ratio of target protein expression level to GADPH expression level with that of the control sample set as 1.0.

Treg cells IL-10 and TGF-β Levels

Treg cells IL-10 and TGF-β Levels were measured using a Human IL-10 and TGF-β ELISA Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

TUNEL staining

TUNEL staining was performed using a TUNEL kit. TUNEL-positive cells with TUNEL staining restricted to the nuclei as confirmed by DAPI double staining were considered apoptotic (TUNEL-positive); diffusely TUNEL-stained cells with no apoptotic morphology were excluded.

Statistics and reproducibility

Data collection and evaluation of all experiments was performed blinded to the group identity. Results are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism (v8.0; GraphPad Software). The Shapiro–Wilk normality test and F test were used for checking the normality and homogeneity of variance of the data sets. Accordingly, 2-tailed unpaired Student’s t test was used for comparisons between 2 groups, or 1/2-way ANOVA with a post hoc test of Tukey analysis was applied when >2 groups were compared if the data displayed a normal distribution. Conversely, a nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test was applied for comparing 2 groups if the data did not display normal distribution. A value of P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant44.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The dataset HRA011745, supporting the findings of this study, is available via controlled access at the China National Center for Bioinformation (CNCB) Genomic Sequence Archive (GSA-Human) under accession number HRA011745 https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa-human/browse/HRA011745). Controlled access is mandated by China’s Interim Measures for the Management of Human Genetic Resources (HGRAC, 2019) to ensure compliance with national legal and ethical regulations for human genomic data. Researchers can request access by submitting an application through the CNCB portal, with responses typically provided within 8–10 weeks following review by relevant regulatory bodies, including ethics committees and HGRAC. A data use agreement is available upon request via the CNCB portal. For further assistance, please contact the CNCB at gsa@big.ac.cn. The uncropped and unedited blot images are shown in Supplementary Fig. 6. The numerical source data can be found in the Supplementary Data 1. Other supporting data related to this work are available upon request.

References

Golledge, J., Thanigaimani, S., Powell, J. T. & Tsao, P. S. Pathogenesis and management of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Eur. Heart J. 44, 2682–2697 (2023).

Song, K., Guo, C., Yang, K., Li, C. & Ding, N. Clinical characteristics of aortic aneurysm in MIMIC-III. Heart Surg. Forum 24, E351–E358 (2021).

Puertas-Umbert, L. et al. Novel pharmacological approaches in abdominal aortic aneurysm. Clin. Sci.137, 1167–1194 (2023).

Hu, K. et al. Pathogenesis-guided rational engineering of nanotherapies for the targeted treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysm by inhibiting neutrophilic inflammation. ACS Nano. 18, 6650–6672 (2024).

Tian, K., Thanigaimani, S., Gibson, K. & Golledge, J. Systematic review examining the association of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor and angiotensin receptor blocker prescription with abdominal aortic aneurysm growth and events. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejvs.2024.03.034 (2024).

Suh, M. K. et al. Ex vivo expansion of regulatory T cells from abdominal aortic aneurysm patients inhibits aneurysm in humanized murine model. J. Vasc. Surg. 72, 1087–1096 e1081 (2020).

Davis, F. M. & Obi, A. T. Recognizing the evolving and beneficial role of regulatory T cells in aneurysm growth. J. Vasc. Surg. 72, 1097 (2020).

Ait-Oufella, H. et al. Natural regulatory T cells limit angiotensin II-induced aneurysm formation and rupture in mice. Arterioscler. Thrombosis Vasc. Biol. 33, 2374–2379 (2013).

Meng, X. et al. Regulatory T cells prevent angiotensin II-induced abdominal aortic aneurysm in apolipoprotein E knockout mice. Hypertension 64, 875–882 (2014).

Yang, F. et al. Propionate alleviates abdominal aortic aneurysm by modulating colonic regulatory T-cell expansion and recirculation. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 7, 934–947 (2022).

Zhang, Q. et al. Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) Treg: a promising approach to inducing immunological tolerance. Front. Immunol. 9, 2359 (2018).

Edinger, M. Driving allotolerance: CAR-expressing Tregs for tolerance induction in organ and stem cell transplantation. J. Clin. Investig. 126, 1248–1250 (2016).

Zhang, X., Zhu, L., Zhang, H., Chen, S. & Xiao, Y. CAR-T cell therapy in hematological malignancies: current opportunities and challenges. Front. Immunol. 13, 927153 (2022).

Abramson, J. S. et al. Lisocabtagene maraleucel for patients with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphomas (TRANSCEND NHL 001): a multicentre seamless design study. Lancet 396, 839–852 (2020).

Yang, J. et al. Next-day manufacture of a novel anti-CD19 CAR-T therapy for B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: first-in-human clinical study. Blood Cancer J. 12, 104 (2022).

Raje, N. et al. Anti-BCMA CAR T-cell therapy bb2121 in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 380, 1726–1737 (2019).

Troncoso, M. F. et al. VCAM-1 as a predictor biomarker in cardiovascular disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 1867, 166170 (2021).

Zhao, G. et al. KLF11 protects against abdominal aortic aneurysm through inhibition of endothelial cell dysfunction. JCI Insight 6, https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.141673 (2021).

Wang, X. et al. Dual-targeted theranostic delivery of miRs arrests abdominal aortic aneurysm development. Mol. Ther. 26, 1056–1065 (2018).

Stather, P. W. et al. Meta-analysis and meta-regression analysis of biomarkers for abdominal aortic aneurysm. Br. J. Surg. 101, 1358–1372 (2014).

Golledge, J. et al. Lack of an effective drug therapy for abdominal aortic aneurysm. J. Intern Med. 288, 6–22 (2020).

Yin, M. et al. Deficient CD4 + CD25 + T regulatory cell function in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysms. Arterioscler. Thrombosis Vasc. Biol. 30, 1825–1831 (2010).

Jiang, H. et al. Abnormal acetylation of FOXP3 regulated by SIRT-1 induces Treg functional deficiency in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysms. Atherosclerosis 271, 182–192 (2018).

Yuan, Z. et al. Abdominal aortic aneurysm: roles of inflammatory cells. Front. Immunol. 11, 609161 (2020).

Dale, M. A., Ruhlman, M. K. & Baxter, B. T. Inflammatory cell phenotypes in AAAs: their role and potential as targets for therapy. Arterioscler. Thrombosis Vasc. Biol. 35, 1746–1755 (2015).

Goswami, T. K. et al. Regulatory T cells (Tregs) and their therapeutic potential against autoimmune disorders - advances and challenges. Hum. Vaccin Immunother. 18, 2035117 (2022).

Harris, F., Berdugo, Y. A. & Tree, T. IL-2-based approaches to Treg enhancement. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 211, 149–163 (2023).

Al-Haideri, M. et al. CAR-T cell combination therapy: the next revolution in cancer treatment. Cancer Cell Int. 22, 365 (2022).

Zhang, E., Gu, J. & Xu, H. Prospects for chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cell therapy for solid tumors. Mol. Cancer 17, 7 (2018).

Troncoso, M. F. et al. Targeting VCAM-1: a therapeutic opportunity for vascular damage. Expert Opin. Therapeutic Targets 27, 207–223 (2023).

Li, H., Cybulsky, M. I., Gimbrone, M. A. Jr. & Libby, P. Inducible expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 by vascular smooth muscle cells in vitro and within rabbit atheroma. Am. J. Pathol. 143, 1551–1559 (1993).

Schulte, S. et al. Cystatin C deficiency promotes inflammation in angiotensin II-induced abdominal aortic aneurisms in atherosclerotic mice. Am. J. Pathol. 177, 456–463 (2010).

Dees, S., Ganesan, R., Singh, S. & Grewal, I. S. Regulatory T cell targeting in cancer: emerging strategies in immunotherapy. Eur. J. Immunol. 51, 280–291 (2021).

Liu, C. et al. Single-chain variable fragment antibody of vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 as a molecular imaging probe for colitis model rabbit investigation. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging 2019, 2783519 (2019).

Greineder, C. F. et al. Molecular engineering of high affinity single-chain antibody fragment for endothelial targeting of proteins and nanocarriers in rodents and humans. J. Control Rel. 226, 229–237 (2016).

Marsico, G., Martin-Saldana, S. & Pandit, A. Therapeutic biomaterial approaches to alleviate chronic limb threatening ischemia. Adv. Sci.8, 2003119 (2021).

Huang, X. et al. Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells isolated from patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm exhibit senescence phenomena. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2019, 1305049 (2019).

Buckner, J. H. Mechanisms of impaired regulation by CD4(+)CD25(+)FOXP3(+) regulatory T cells in human autoimmune diseases. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 10, 849–859 (2010).

Cao, Q. et al. Downregulation of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells may underlie enhanced Th1 immunity caused by immunization with activated autologous T cells. Cell Res. 17, 627–637 (2007).

Steiner, R. & Pilat, N. The potential for Treg-enhancing therapies in transplantation. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 211, 122–137 (2023).

Noyan, F. et al. Prevention of allograft rejection by use of regulatory T cells with an MHC-specific chimeric antigen receptor. Am. J. Transplant. 17, 917–930 (2017).

Arjomandnejad M., Kopec A. L., Keeler A. M. CAR-T regulatory (CAR-Treg) cells: engineering and applications. Biomedicines 10, https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10020287 (2022).

Tang, D. et al. Y chromosome loss is associated with age-related male patients with abdominal aortic aneurysms. Clin. Inter. Aging 14, 1227–1241 (2019).

Feng, G., Qin, G., Zhang, T., Chen, Z. & Zhao, Y. Common Statistical Methods and Reporting of Results in Medical Research. CVIA 6, 117–125 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 82170507 and 81970402 to Jian Zhang, grant 81800407 to Han Jiang, grant 81600370 to Yanshuo Han), Liaoning Provincial Applied Basic Research Program (grant 2022JH2/101300037 to Jian Zhang), International Science and Technology Cooperation Program of Liaoning Province (grant: 2023JH2/10700019 to Han Jiang), the Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province (grant: 2023-MS-096 to Yanshuo Han).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: J.Z., Y.S.H., Y.L. Methodology: Q.G., J.U., H.J., X.Z. Investigation: Q.G., P.E., S.S., D.B. Visualization: Q.G., Y.C.H., Y.M.L. Supervision: D.B., J.Z., Y.S.H. Writing—original draft: Q.G., Y.L., Y.S.H. Writing—review & editing: D.B., J.Z., Q.G., Y.S.H.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Elizabeth L. Chou and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Dr Dr Madhumita Basu and Dr Ophelia Bu. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gang, Q., Lun, Y., Zhang, X. et al. Targeting VCAM-1 with chimeric antigen receptor and regulatory T cell for abdominal aortic aneurysm treatment. Commun Biol 8, 1230 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08604-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08604-9