Abstract

End capping of oligonucleotides by modified nucleotides is essential for boosting resistance to 3’ exonuclease degradation, thereby enhancing their stability and therapeutic efficacy in vivo. However, the rationale behind these modifications remains unclear. In this study, we designed a novel nucleic acid analog, eTNA, by replacing deoxyribose with the α-D-erythrofuranosyl moiety. As an epimer of TNA (threose nucleic acid), it combines structural features from inverted-dT and TNA, both known for enhancing resistance against 3’-exonucleases. On top of this, we systematically investigated the stability of a series of oligonucleotides capped with inverted-dT, TNA and eTNA at the 5’-, 3’-, or both ends. The structural differences between eTNA and natural dT help to understand how the sugar ring’s conformation and rigidity affect duplex stability and exonuclease resistance. Our experimental and theoretical results show that the modified furanose affects the binding positions of terminal nucleotides in the phosphodiesterase active site, preventing phosphodiester hydrolysis. Our mechanistic study should benefit future therapeutic oligonucleotide design with end capping.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the past few decades, significant progress has been made in the development of oligonucleotide-based treatments, with 19 drugs approved for various diseases1,2. Typically, oligonucleotide therapeutics utilize short synthetic nucleic acid polymers to modulate gene expression, and target specific genes or proteins in various diseases3. They include antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), and microRNAs (miRNAs), which primarily function by forming double-stranded complexes with target RNA, leading to the cleavage or degradation of target mRNA and interruption of protein production4. Notably, oligonucleotide-based therapeutic platforms also encompass two distinct classes of functional molecules—aptamers and DNAzymes—derived from in vitro selection methodologies5,6. Aptamers are highly specific and bind strongly to target molecules5, while DNAzymes, a class of catalytic nucleic acids, combine sequence recognition with enzymatic activity7. As oligonucleotides have the potential to treat diseases associated with undruggable proteins, they offer a versatile and targeted approach at the molecular level5.

Although oligonucleotide therapeutics has demonstrated significant therapeutic potential, their clinical application still faces several challenges such as low delivery efficiency, off-target effects, and poor stability1,8. The biostability of oligonucleotide therapeutics is one of the most important difficulties hindering their development and clinical application, as unmodified DNA and RNA oligonucleotides decay fast in vitro and in vivo, particularly in blood9,10. Chemical modifications are frequently required to improve the intracellular and serum stability of oligonucleotides, therefore improving their resistance to nuclease metabolism and plasma half-life11. Various chemically modified oligonucleotides have been developed, including phosphorothioate ODN and sugar-modified XNAs like 2’-F-RNA, 2’-OMe-RNA, 2’-MOE-RNA, FANA (2’-fluoro-arabinonucleic acid), LNA (locked nucleic acid), phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomer (PMO)4 and TNA (threose nucleic acid)12. These modifications have been widely implemented in approved nucleic acid drugs and those in clinical trials, particularly for ASOs and siRNAs, which function through Watson-Crick base pairing with target RNA9. For instance, second-generation antisense oligonucleotides like Mipomersen and Inotersen have utilized 2’-O-methoxyethyl-modified nucleotides to enhance enzyme resistance1,9. In contrast, other types of oligonucleotide drugs, like aptamers and DNAzymes, require specific 3D structures to maintain their binding affinity or catalytic efficiency, making them sensitive to chemical modifications in their functional sequences13,14. For example, the DNAzyme 10–23, when modified with phosphorothioate (PS) linkages throughout its substrate recognition arms, showed significantly reduced catalytic activity14. To replicate ASO-like functions and stability, iterative design, build, test, and learn cycles are necessary to identify permissive sites within the scaffold for chemical modifications15,16. Extensive changes to the backbone may also impact hybridization efficiency and pose additional challenges related to chirality, hydrophobicity, and potential toxicity17.

Studies indicate that oligonucleotide degradation in serum, plasma, or in vivo primarily occurs through 3’ to 5’ exonucleolytic mechanisms5,10,18,19. The plasma half-life of oligonucleotides directly affects their clearance kinetics and tissue distribution, making long-term effectiveness—especially in non-liver tissues—largely dependent on stability18. Therefore, enhancing oligonucleotide stability, particularly at the 3’ end, is vital for improving accumulation in both hepatic and extrahepatic tissues18,20. For this, capping the 3’-end with unnatural nucleoside analogs has emerged as a key and straightforward strategy for boosting stability of aptamers or DNAzymes5,14,21. For example, the Selger laboratory synthesized oligonucleotides incorporating inverted deoxythymidine (inverted-dT, INV-T) at the ends, leading to a significantly extended half-life of 30 h in human serum, compared to just 20 min for natural oligonucleotides22. Similarly, Beigelman et al. reported that the inverted-dT residue enhanced stability by 30–50-fold depending on the specific chemistries involved21,23. Notable research by the Chaput laboratory and others on threose nucleic acid (TNA) has highlighted its exceptional stability against nucleases24,25,26, demonstrating its potential as a protective capping agent for safeguarding DNAzyme against degradation in various enzyme-rich environments27. This strategy has been successfully applied in FDA-approved aptamer drugs, such as Pegaptanib9 and Avacincaptad pegol28, both of which utilize 3’-end inverted-dT capping. Additionally, it is being investigated in several clinical-stage candidates, including ARC1779, REG1, and BAX49929.

The 3’-exonuclease resistance mechanisms of several uncommon terminal ribose modification have been elucidated through crystal structure analysis30,31 or molecular modeling studies32 based on the Klenow Fragment (KF) exonuclease from E. coli. Surprisingly, studies have not been conducted on the widely used INV-T, which is employed in FDA-approved aptamer drugs. Furthermore, no structural studies have been conducted on more relevant phosphodiesterases (PDEs), such as snake venom phosphodiesterase (VPD), as opposed to the Klenow Fragment (KF)31. VPD shares significant sequence and structural similarities with the human ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase 1 (ENPP1) family33,34, which hydrolyze extracellular nucleotide derivatives to regulate signaling pathways. Although KF shares some similarities to mammalian exonucleases, it exhibits subtle differences in both structure and catalysis mechanism compared to VPD33. The active site of KF contains two metal ions, Zn2+ and Mg2+, with the latter being crucial for stabilizing the leaving phosphate group30,31,35. In contrast, VPD contains two Zn2+ atoms at its active site33 and hydrolyzes phosphodiesters (Fig. 1A, B) via a two-step inline displacement mechanism (Fig. 1C) which utilizes the conserved threonine nucleophile at the active site36,37. Since VPD is more relevant to human PDEs in serum, investigating the molecular interactions between VPD and oligonucleotides with modified 3’-terminal nucleotides is essential for elucidating the structural basis for 3’-exonuclease resistance in these modified oligonucleotides.

A The crystal structure of VPD shows the enzyme consists of three structural domains, i.e. the N-term (blue), PDE (palecyan) and NUC (orange) domains. The active site is located in the PDE domain and contains two Zn2+ ions, PDB code: 5GZ5. B The binding site of VPD accommodating dTMP nucleotide is depicted by molecular surface (left) and cartoon models. Zn2+ ions are shown as spheres with labels. The N and S pockets for nucleotides are indicated. Crucial amino acid residues are colored differently in the surface model and shown as sticks in the cartoon model. C The two-step inline displacement mechanism proposed for the enzymatic hydrolysis of phosphodiester by PDEs. The R3’ represents the 3’-terminal nucleotide, while R is the second nucleotide counted from the 3’-end. Threonine (T185) acts as a nucleophile attacking the phosphorus to form a trigonal bipyramidal transition state. The Oγ atom of T185, phosphorus and the oxygen connecting to R are supposed to be aligned in a line as indicated by the blue arc arrows.

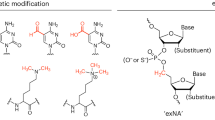

Inspired by the enhanced nuclease resistance of INV-T and TNA, this study investigates the molecular mechanisms underlying their 3’-exonuclease resistance. The INV-T switches the orientation of deoxyribose ring and subsequently the orientation of the thymine base (Fig. 2A). In the case of TNA, the phosphate group is shifted to 2’-OH of threofuranosyl ring, not only reducing the spacing between neighboring phosphate groups, but also changing the pucker conformation of the sugar ring (Fig. 2B). These structural changes should somehow disturb the recognition of 3’-exonuclease to the terminal nucleotide. Questions arise about how 3’-exonuclease recognizes normal 3’-terminal nucleotides and how structurally distinct XNAs inhibit enzymatic cleavage. To investigate these issues, we designed a novel nucleic acid by substituting deoxyribose with α-D-erythrofuranosyl, the epimer of α-L-threofuranosyl (termed eTNA, Fig. 2). This new structural configuration combines features of both inverted nucleotide and TNA, aiming to reveal how the conformation and rigidity of the sugar ring alter the binding poses of terminal nucleotides in the active site of phosphodiesterase. Subsequently, we synthesized oligonucleotides with three different terminal modifications—INV-T, TNA-T, and eTNA-T—and assessed their thermal stability and nuclease resistance. Molecular modeling studies were carried out to elucidate how these modifications affect duplex stability and enhance protection against 3’-exonucleases.

A Structures of the DNA oligonucleotides with a single dT, INV-T, or eTNA-T at the 3’-end. B Pucker conformations of all 4 terminal nucleotides obtained by QM structural optimization. Only backbone atoms are shown while the thymine base is represented by a single nitrogen atom with a T label. Carbon, oxygen, nitrogen, phosphorus and polar hydrogen atoms are colored in cyan, red, blue, orange and light-gray, respectively. The aesthetic star indicates the phosphate group.

Results and discussion

Structural features of terminal nucleotides

Modified nucleotides often exhibit distinct puckering conformations compared to canonical DNA or RNA, influencing the conformation of the oligonucleotide’s phosphodiester backbone and altering base stacking interactions between neighboring nucleotides. The puckering angles of all four thymine nucleotides were calculated based on structures optimized using quantum mechanics (QM) method (Fig. 2B). Both T and INV-T adopted a C2’-endo conformation, characteristic of B-form DNA. The pucker angle for TNA-T was measured at 33.4°, within the 36 ± 22° range observed by NMR for the 3’-terminal TNA nucleotide38, validating the reliability of the quantum mechanical optimizations. Subsequent analysis of the QM-optimized structure of eTNA-T revealed a markedly different sugar conformation, with a pucker angle of 9.5°, indicative of a C3’-endo conformation similar to that of the ribose ring in RNA. The pucker angles of all four nucleotides are detailed in the Supporting Information (Supplementary Table S1).

Synthesis of eTNA monomers

The eTNA nucleoside is an epimer of the TNA nucleoside. Our chemical synthesis strategy for eTNA is derived from the method established for TNA by Chaput and colleagues (Fig. 3)39. In this study, our synthesis began with the preparation of the glycosyl donor 5. Initially, D-erythronolactone (2) was prepared from the known compound D-isoascorbic acid (1) according to the reported procedures40. The oxidative cleavage of D-isoascorbic acid (1) was carried out in the presence of hydrogen peroxide and Na2CO3, followed by treatment with hydrochloric acid to induce an intramolecular lactonization, resulting compound D-erythronolactone (2). The 2’-O-position of 2 was selectively protected with a benzoyl group to facilitate the neighboring group participation effect for stereoselective β-glycosylation41. Subsequently, treatment of compound 3 with tert-butyldimethylchlorosilane and imidazole in CH2Cl2 furnish compournd 4. Finally, compound 4 was reduced from its lactone form to the corresponding lactol using DIBAL-H, followed by acetylation at the anomeric position, yielding glycosyl donor 5 in a 75% yield.

Reagents and conditions: a (1) Na2CO3, 30% aq. H2O2, H2O, 1 h, 0–40 °C; (2) active charcoal, 1 h, 40 °C; (3) Conc. HCl, pH = 1, 0.5 h, 0 °C, 70%; b benzoylchloride, 1:9 pyridine−CH2Cl2, 1 h, 0 °C, 60%; c tert-butyldimethylchlorosilane, imidazole, CH2Cl2, overnight, rt, 90%; d 1 M DIBAL-H in hexanes, anhydrous THF, 2.5 h, −78 °C; e sat. aq. potassium sodium tartrate, EtOAc, overnight, rt; f Ac2O, DMAP, CH2Cl2, 4 h, rt, 75% for three steps; g thymine, N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)acetamide (BSA), trimethylsilyltriflate (TMSOTf), anhydrous acetonitrile, 1 h, rt to 60 °C; h N6-benzoyladenine, BSA, TMSOTf, anhydrous toluene, 2 h, 95 °C; i triethylaminetrihydrofluoride, THF, overnight, rt, 80% for 6a, 75% for 6b; j 4,4’-dimethoxytrityl chloride (DMTrCl), 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP), pyridine, 6 h, 80 °C; k DMTrCl, DMAP, pyridine, overnight, 80 °C; l 1 M NaOH, 5:4 THF−MeOH, overnight, 0 °C to rt, 80%; m 1 M NaOH, 5:4 THF−MeOH, 7 h, 0 °C, 67%; n N,N-diisopropylethylamine, 2-cyanoethyl N,N-diisopropylchlorophosphoramidite, anhydrous CH2Cl2, 1 h, rt, 72% for 8a, 80% for 8b.

With the glycosyl donor 5 in hands, the Vorbrüggen glycosylation42 of silylated thymine was conducted in the presence of trimethylsilyl trifluoromethanesulfonate (TMSOTf) at 60 °C in anhydrous acetonitrile, resulting in the synthesis of fully protected nucleoside T for eTNA 6a. Similarly, glycosyl donor 5 was treated with silylated N 6-benzoyladenine and TMSOTf at 95 °C in anhydrous toluene, resulting the protected nucleoside A of eTNA 6b. Desilylation of the fully protected nucleosides T and A for eTNA was achieved using triethylamine trihydrofluoride as a mild desilylation reagent43, providing compounds 6a and 6b, respectively, in yields of 75–80% after crystallization. The 3’-O-position of 6a and 6b are tritylated with DMTr-Cl using pyridine as a base, followed by selective deprotection of 2’-O-benzoyl group by sodium hydroxide to provide compound 7a and 7b, respectively. The 2’-OH of 7a and 7b were phosphitylated with 2-cyanoethyl-N,N-diisopropylchlorophosphine to yield the phosphoramidite monomers 8a and 8b.

Overall, our synthetic protocol for eTNA phosphoramidites involves ten sequential chemical transformations, along with three crystallization steps and three chromatographic purifications, yielding T phosphoramidites at 13.1% and A phosphoramidites at 11.4%. The characterization of all compounds was carried out thoroughly using high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, as detailed in the Supporting Information (Supplementary Figs. S60–89).

Synthesis of oligonucleotides

After obtaining the pure eTNA phosphoramidites 8a and 8b, they were used as modified monomers in solid-phase syntheses and incorporated at the specified positions within the DNA strands, either in central or at terminal positions. Oligonucleotides modified at the terminus with INV-T and TNA-T were synthesized simultaneously, along with four RNA oligonucleotides containing 3’-end modified nucleosides. The synthesis of all oligonucleotides was carried out by utilizing standard solid-phase P (III) oligonucleotide chemistry. The synthesized oligonucleotides were subjected to purification via high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), and their identities were confirmed through MALDI-TOF mass analysis (Supplementary Figs. S3–24). The obtained data and sequences are presented in supporting information Supplementary Table S2.

Thermal melting studies

The effect of INV-T, TNA-T and eTNA-T modifications on the thermal stability of oligonucleotide duplexes was assessed by analyzing changes in melting temperatures (Tm). The Tm curves were obtained with an UV−vis spectrophotometer equipped with a temperature controller, and the results were shown in Supplementary Table S3 and Table 1, and all Tm curves were shown in Supporting Information (Supplementary Figs. S25–28).

To evaluate the compatibility of eTNA phosphoramidite for oligonucleotide synthesis, we incorporated it site-specifically into the central position of DNA strands and measured the melting temperatures of the resulting duplexes (Supplementary Table S3). The results revealed that the incorporation of central eTNA severely destabilized duplex stability, with ΔTm values ranging from −11.3 to −16.0 °C. In contrast, DNA duplexes containing a single central TNA residue or a TNA–TNA pair exhibited only slight destabilization (ΔTm = −0.4 to −2.6 °C), highlighting TNA’s favorable accommodation within the DNA helix. The pronounced destabilization caused by eTNA likely arises from its distinct sugar configuration, which positions the nucleobase downward, disrupting base stacking and hydrogen bonding (Fig. 2). These findings underscore eTNA’s incompatibility as an internal modification.

Previous research has demonstrated that a single unpaired nucleotide at the ends of double-stranded nucleic acids, also known as “dangling ends”, can potentially enhance the stability of the duplex structure44. In view of this, INV-T, TNA-T or eTNA-T was incorporated at the terminus of DNA chains as dangling nucleotides to investigate their influence on DNA duplex stability, in comparison to the natural dT residue. The results were shown in Table 1. The findings indicated that incorporation of all four types of nucleotides showed an improvement in the stability of DNA duplexes when placed at the end of a DNA strand as dangling nucleotides, whether at the 3’ end, the 5’ end, or both ends. Notably, the presence of dangling dT nucleotides at both ends of the DNA strand led to a further enhancement in the stability of the DNA duplexes compared to those at only one end. Furthermore, different non-natural dangling Ts at the 5’ end or both ends of DNA exhibited a similar stabilizing effect on the DNA duplexes, with ΔTm values ranging from +1 °C to +2 °C. Overall, the positive effects of terminal dangling modifications on DNA duplexes suggested that the formation of the double helix structure remained largely unaffected by the introduction of inverted ends, indicating that these modified nucleotides did not disrupt Watson-Crick base-pairing.

To gain insights into the structural origins of the stabilization effect of these terminal modified Ts, we performed molecular dynamics (MD) simulations on DNA duplexes capped with 3’-dT, 3’-INV-T, 3’-eTNA-T and 3’-TNA-T (Supplementary Fig. S1). Previous studies suggest that dangling ends stabilize oligonucleotide duplexes through cross-strand stacking which protects the terminal base pair from water45. This mechanism was confirmed in MD trajectories of DNA duplexes capped by 3’-INV-T (Fig. S2B) and 3’-eTNA-T (Supplementary Fig. S2C) which displayed a higher population of cross-strand stacking conformations, exerting higher stabilization effects to the duplex. In contrast, the 3’-T nucleotide was primarily stacked on the neighbor thymine of the same strand, providing limited protection to the terminal base pair (Supplementary Fig. S2A).

Nuclease stability assays of 5’ or 3’- terminal modified oligonucleotides

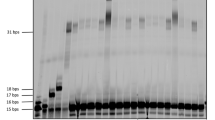

Given the critical role of biostability in the efficacy of nucleic acid drugs in biomedical applications, it is imperative to assess the stability of oligonucleotides bearing terminal modifications such as INV-T, TNA-T, eTNA-T, or dT in a biological environment. These modifications were introduced at the 5’-end, 3’-end, or both ends of the oligonucleotides. Subsequently, the oligonucleotides underwent nuclease degradation using bovine spleen phosphodiesterase (SPD)46, snake venom phosphodiesterase (VPD), or 50% human serum26. SPD and VPD exhibit 5’ to 3’ and 3’ to 5’ exonuclease activities, respectively. For further validation, we also added these modifications to the 3’ end of RNA oligonucleotides and treated them with VPD. The resulting stability profiles were depicted in the Supporting Information (Supplementary Figs. S29–59).

Capping the oligonucleotides with eTNA-T at the 5’-end significantly improved their exonuclease resistance against SPD (Fig. 4A). PAGE analysis showed no significant degradation throughout the observation period. Generally, oligonucleotides capped with 5’-INV-T exhibited the highest resistances to SPD, with almost no degradation. After 72 h of digestion with SPD, nearly 67% and 70% of the oligonucleotides protected with eTNA-T and TNA-T 5’-capping remained. 5’-modified oligonucleotides showed significant enhancement of stability compared to unmodified oligonucleotides which have a half-life of only a few minutes. To better mimic biological conditions, modified oligonucleotides were also subject to degradation in 50% human serum (Fig. 4C). As expected, the terminal eTNA modification extended the half-life of oligonucleotides from 8.7 min to 3.3 h, significantly enhancing the stability of oligonucleotides in human serum. Comparable effects were also observed for INV-T (T1/2 of 3.7 h) and TNA (T1/2 of 2.8 h) modifications.

Exonuclease resistance assays against VPD, known for its 3’ to 5’ exonuclease activity, were conducted for oligonucleotides capped with eTNA-T, INV-T, or TNA-T at the 3’-end (Fig. 4B). These modified oligonucleotides showed no observable degradation during the observation period of 72 h, whereas unmodified oligonucleotides remained stable for less than 15 min. When 3’-end modified oligonucleotides were subject to degradation in 50% human serum (as illustrated in Fig. 4D), it was observed that oligonucleotides with eTNA-T, INV-T and TNA-T exhibited significantly prolonged half-lives of 24.2, 10.5 and 18.8 h, while oligonucleotide with natural dT had a half-life of approximately 19 min. The eTNA-T modification increased 3’-exonuclease resistance, outperforming established modifications like TNA-T and INV-T, which are commonly used as standard commercial modifications.

Next, we investigated the potential to combine protective modifications at both the 5’ and 3’ ends of oligonucleotides simultaneously (Supplementary Fig. S29). It is not surprising that all dually-modified oligonucleotides—eTNA-T, INV-T, or TNA-T showed similar enhanced stability compared to their unmodified counterparts, with no notable degradation observed during the observation period. Upon exposure to 50% human serum (Supplementary Fig. S30), terminal modifications of oligonucleotides with eTNA-T, INV-T, or TNA-T at both ends show improved stability (half-life of 9.8, 12.4, and 24.0 h) when compared to unmodified oligonucleotides (half-life of 27.6 min). Surprisingly, 3’- and 5’-end dual modification of oligonucleotides with eTNA-T was less stable than 3’-end modification alone. In contrast, dual capping with TNA-T or INV-T further enhanced enzymatic resistance.

In addition, we tested the VPD stability of RNA oligonucleotides modified with eTNA, INV-T, and TNA-T at the 3’ end. The results were showed in the Supporting Information (Supplementary Fig. S31). All 3’ modifications increased the half-life of RNA oligonucleotides by 8–18 folds compared to unmodified RNA oligonucleotides, which had a half-life of only 1.6 min. Serum stability was not assessed due to rapid RNA degradation in serum, which is mainly due to the hydrolysis by RNase enzymes.

Collectively, comparative analyses reveal that eTNA-T 3’-capping outperforms both INV-T and TNA-T in 50% human serum, demonstrating 2.3-fold and 1.3-fold greater stability against 3’ → 5’ exonuclease degradation, respectively (Fig. 4D). The eTNA-T modification represents a significant advancement in 3’-end stabilization, probably providing high efficiency and broad applicability across nucleic acid therapeutics.

Molecular mechanism of exonuclease resistance of 3’-capped oligonucleotides

Motivated by the significant enhancement of exonuclease resistance in terminally capped oligonucleotides, we aimed to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying 3’-exonuclease resistance. Early experiments indicated that cleavage by 3’-exonucleases primarily contributes to oligonucleotide degradation in serum. We chose VPD as a model enzyme because it is commonly used to assess 3’-exonuclease resistance for oligonucleotides26. Additionally, the recent reporting of VPD crystal structures allows for direct investigation of interactions between oligonucleotides and VPD33.

For simplicity in the computational studies, we used dinucleotides consisting of a normal thymidine and a modified thymidine (INV-T, TNA-T, eTNA-T) to model oligonucleotides with terminal modifications. The 5’-O of the first thymidine was capped with a methyl phosphate group, resulting in dinucleotides labeled as MpTT, MpTiT, MpTeT, and MpTtT, respectively. We employed ligand-protein docking and molecular dynamics simulations to construct structural models for VPD and these dinucleotides. The catalytic active site of VPD (Fig. 1B) features a bi-zinc metal center, a nucleobase-binding pocket (N pocket) between aromatic amino acids F186 and Y269, and an S pocket for VDP accommodating the second nucleotide of dinucleotide substrates. Binding poses of all four dinucleotides in VPD’s active site are illustrated in Fig. 5. The binding orientations of the normal thymidine in all four dinucleotides were similar (Fig. 6B), indicating reliable structural models. While the 5’-methyl phosphate group varied among binding poses due to the absence of the remaining oligonucleotide segments, it showed minimal interactions with the 3’-terminal nucleotides. Consequently, we focused our analyses on the 3’-terminal nucleotides, disregarding the 5’-methyl phosphate group.

From A to D are binding poses of MpTT (dT), MpTiT (INV-T), MpTeT (eTNA-T) and MpTtT (TNA-T), respectively. Critical amino acids in the active site of VPD are depicted as sticks with carbon atoms colored in cyan. Zn2+ ions are shown as gray spheres with labels Zn1 and Zn2, respectively. The dinucleotides are shown as sticks with carbons in the 3’-end nucleotides colored in yellow, while carbons in the 5’-end nucleotides are colored in magentas. Superimposition between the transition state (TS) like structures of dinucleotides and the rat NPP2 x VO5 TS analog complex structure are presented on the right side. Distances between atoms or hydrogen bonds are indicated by dashed black lines.

A Binding pose of natural thymidine dinucleotide (MpTT). Key amino acid residues surrounding the dinucleotide are indicated. The molecular surface of VPD is shown. B Superimposition of binding poses of all four dinucleotides. C, D Different orientations of the 3’-terminal thymine bases between deoxyribose-based nucleotides (MpTT and MpTiT) and threose-based nucleotides (MpTtT and MpTeT) in the N pocket of VPD. Dinucleotides are depicted by sticks with oxygen, nitrogen, phosphorus and polar hydrogens colored in red, blue, orange and white, respectively. Carbon atoms from different nucleotides colored: MpTT (dT), green; MpTiT (INV-T), cyan; MpTeT (eTNA-T), magentas; MpTtT (TNA-T), yellow. Zinc atoms are shown as gray spheres.

The four 3’-terminal nucleotides displayed diverse binding poses (Figs. 5 and 6B), particular for the sugar ring and the thymine base. The 3’-terminal thymines of MpTT (T3’) and MpTiT (INV-T) occupied the N pocket, with their rings sandwiched between the aromatic residues F186 and Y269 (Figs. 5A, B and 6A, B). In the cases of MpTeT (eTNA-T) and MpTtT (TNA-T), their nucleobase moieties were positioned closer to the entrance of the N pocket and were more solvent-exposed (Figs. 5C, D and 6B), rather than extending into the space between F186 and Y269. Previous studies have shown that the strength of π-π stacking between nucleobases and the phenol ring of Y269 is crucial for NTP recognition by VPD. In the cases of MpTeT and MpTtT, this π-π stacking interaction was absent. Furthermore, these nucleotides were more solvent-exposed, likely reducing the binding affinities of oligonucleotides capped with eTNA-T or TNA-T. This diminished binding affinity partially explains the hydrolysis resistance of eTNA-T and TNA-T capped oligonucleotides.

Close inspection into binding poses of all dinucleotides revealed that the orientations of the nucleobases were mainly determined by the configurations of the sugar rings (Fig. 6C, D). The deoxyribose ring of MpTT adopted an orientation nearly vertical to the plane of the phenol ring of Y269 of VPD and the 3’-OH group on the sugar ring formed a hydrogen bond with the amine group of K271 in VPD (Figs. 5A and 6A). The binding pose of T3’ was quite similar to that of dTMP in its cocrystal structure (PDB code: 4GTX; Fig. 1B) with mouse Enpp1 which is homologous to VPD. For the other three modified thymidines (Fig. 6C, D), the sugar rings were all parallel to the phenol ring of Y269, due to the direct connection of the phosphate group to these rings. As a result, 5’-OH of INV-T in MpTiT formed a hydrogen bond with the carboxylic oxygen of D305, which also coordinated with Zn2 (Fig. 5B). This interference could disrupt the enzyme’s catalytic function, as both carboxylic oxygens of D305 can coordinate with Zn2. The thymine base of INV-T was also parallel to the phenol ring of F269 and reached the space between F186 and Y269 (Figs. 5B and 6C). Although the nucleobases in DNA typically adopt a vertical orientation relative to the pseudo-plane of the deoxyribose ring, the sugar ring of INV-T adopted a C2’-endo puckering conformation, allowing considerable rotational freedom for the thymine base. In MpTeT, however, the thymine group was almost vertical to the sugar ring, pointing away from F186 and Y269 of VPD (Figs. 5C and 6D). This was because the sugar ring adopted a C3’-endo conformation with the 2’-OH blocking the thymine base to rotate as in INV-T (Fig. 7A). A similar binding pose was observed for the TNA-T in MpTtT (Figs. 5D and 6D).

Dinucleotides are depicted by sticks with carbon atoms of the normal thymidines colored in cyan. The calculated binding poses of 3’-eTNA-T (A) and 3’-TNA-T (B) are colored in magentas. Imaged binding poses for thymines of 3’-eTNA-T and 3’-TNA-T are generated by manually rotating the base round the glycosidic bond and the carbon atoms are colored in yellow. Steric clashes between atoms are indicated by dashed yellow arcs.

Realizing that both the conformation and rigidity of the sugar ring significantly influence the binding poses of the 3’-terminal nucleosides in VPD’s active site, we questioned whether these structural effects perturb subsequent enzymatic catalysis steps, such as transition state formation. According to the two-step inline displacement mechanism, the hydrolysis of phosphodiesters involves a five-coordinate trigonal bipyramidal transition state (Fig. 1C). Critical to this process is the accessibility of the phosphorus to the Oγ atom of T185, as well as the angle formed by Oγ of T185, the phosphorus, and the leaving oxygen, which should be close to 180°. Failure to meet either condition would hinder the hydrolysis of the phosphodiester. We then constructed transition state-like (TS-like) structure models for all four dinucleotides using steered molecular dynamics simulations and assessed their stability. As shown in Fig. 5, the alignment of Oγ of T185, the phosphorus, and the leaving oxygen connected to the second thymidine closely matched the rat NPP2-VO5 TS analog complex structure (PDB code: 5IJS). Interestingly, during short molecular dynamics simulations (5 ns) with a strong distance restraint applied between Zn1 and the nearest oxygen of the phosphate group, all three modified 3’-terminal dinucleotides quickly deviated from their TS-like structures (Fig. 5B–D). In contrast, the dinucleotide formed by two normal thymidine maintained its TS-like structure (Fig. 5A). These results clearly indicate that it is significantly more difficult for these modified dinucleotides to form the five-coordinate trigonal bipyramidal transition state in VPD’s active site.

Based on our computational calculations and structural analyses, we propose a mechanism to explain the 3’-exonuclease resistance of the three modified thymidines against VPD. In the enzyme-substrate (ES) complex, the direct connection of the phosphate group to the sugar ring forces it into a parallel orientation with the phenol ring of Y269 in VPD (Fig. 7). The position of the thymine base on the opposite side of the sugar ring leads to varying binding poses in the N-binding pocket of VPD (Fig. 6B), depending on the sugar pucker conformations (Fig. 2). Consequently, reduced binding affinity occurs when the thymine binding is suboptimal, such as lacking π-π interactions with Y269. Additionally, the rigidity of the sugar ring hampers the formation of productive transition states, further affecting the catalytic reaction. Together, these factors contribute to the enhanced 3’-exonuclease resistance of oligonucleotides with modified 3’-terminal thymidine.

This mechanism, to our knowledge, is the first molecular mechanism proposed for the underlying VPD resistance of 3’-terminal modifications of oligonucleotides, facilitated by the recent publication of VPD crystal structures33. For nearly 40 years, the principle of blocking metal ion binding at the site equivalent to Zn1 in VPD (Fig. 1B) has guided the design of 3’-exonuclease resistant oligonucleotides9. This principle stems from crystallographic studies showing that bulky modifications, such as phosphorothioate (PS) and 2’-O-substituents, prevent Mg2+ from occupying the active site of KF when bound to DNA oligomers30,31. However, no evidence suggests that 3’-terminal modified nucleotides replace Zn1 at the VPD active site, highlighting the need for caution when using KF to design new modifications. VPD is routinely employed as a model enzyme to evaluate the 3’-exonuclease resistance of oligonucleotides, particularly as it closely resembles human ENPP1, a key contributor to oligonucleotide degradation in human serum47. Here, we investigate the exonuclease resistance mechanism directly based on VPD structures. The mechanism proposed in this manuscript can serve as a guiding principle for the future design of 3’-exonuclease resistant nucleotides.

3’-Capping as a minimal strategy for enhancing oligonucleotide exonuclease resistance

Chemical modification strategies in oligonucleotide therapeutics differ significantly between drug classes. Antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) and siRNAs, which rely on Watson-Crick base pairing, employ extensive backbone modifications—such as phosphorothioate (PS) linkages, 2’-F-RNA, 2’-O-methyl (2’-OMe), and locked nucleic acid (LNA)—to enhance enzymatic resistance and hybridization stability1. In contrast, aptamers (e.g., Pegaptanib) and DNAzymes require precise three-dimensional structures for their function, making them sensitive to broad modifications14. Their structural sensitivity necessitates a minimal approach, with modifications restricted to non-functional termini or combined with localized sugar adjustments (e.g., 2’-F, 2’-OMe) to avoid disrupting critical catalytic cores or binding pockets14,27. This underscores the importance of 3’-terminal capping as a critical solution. By selectively blocking 3’ → 5’ exonuclease degradation—the primary pathway for oligonucleotide clearance—this approach enhances biostability while maintaining structural integrity5,10,18,19.

The 3’-terminus is essential for optimizing aptamer and DNAzyme therapeutics. Clinically validated strategies include Pegaptanib’s3’-inverted thymidine (INV-T) capping, combined with 2’-F/2’-OMe modifications9, and Avacincaptad pegol’s28 dual 3’-capping/PEGylation system to extend systemic circulation. In addition to extending plasma half-life, 3’-end engineering may address several limitations of global modifications, including (1) minimal disruption to critical secondary/tertiary structures14; (2) elimination of chirality issues associated with PS linkages3; and (3) enhanced predictability in structure-activity relationships27. This approach lessens the need for iterative optimization of functional sequences by focusing modifications on non-critical termini.

Emerging innovations, including novel caps and mechanistic studies of exonuclease recognitions, are positioning 3’-terminal chemistry as a cornerstone for advancing oligonucleotide therapies. This study introduces eTNA, a new 3’-capping analog derived from the stereochemical epimerization of TNA, and demonstrates its superior resistance to 3’-exonuclease. Utilizing molecular modeling with venom phosphodiesterase (VPD)—a human ENPP1 homolog critical for the degradation of therapeutic oligonucleotides—we reveal that eTNA’s unique sugar puckering (9.5° compared to TNA’s 33.4°) flips the 2’-OH toward solvent and forces thymine into a high-energy syn conformation, destabilizing VPD binding. In contrast to inverted-dT, which blocks catalysis by preventing transition-state formation, eTNA disrupts enzyme-substrate recognition through disturbed π-π stacking and impedes catalytic progression, providing dual resistance mechanisms. Comparative analyses with TNA further emphasize eTNA’s enhanced ability to evade enzymatic degradation, attributable to its stereochemical reconfiguration. By integrating atomistic MD simulations of VPD complexes with functional validation, this work establishes a rational framework for designing 3’-capping analogs that maintain structural integrity in aptamers and DNAzymes. This approach advances stability-enhanced oligonucleotide therapeutics through targeted, scalable modifications rather than relying solely on the empirical trial-and-error strategy.

Conclusion

In summary, while the recognition of 3’-terminal nucleotide modifications by 3’-exonucleases and how structurally distinct XNAs inhibit enzymatic cleavage remain unclear, we have investigated the structural and functional effects of terminal modifications on natural oligonucleotides and the underlying molecular mechanisms using chemical biology and computational modeling. Experimental and computational analyses of oligonucleotides capped with inverted-dT, TNA and eTNA at the 5’-, 3’-, or both ends were carried out. Particularly, we designed a novel nucleic acid by substituting deoxyribose with α-D-erythrofuranosyl, the epimer of α-L-threofuranosyl (termed eTNA), which can be produced easily and effectively incorporated into synthetic oligonucleotides through solid-phase synthesis. This structure combines features of both inverted nucleotide and TNA, helps to reveal how the conformation and rigidity of the sugar ring affect the binding poses of terminal nucleotides in the phosphodiesterase active site. Our findings indicate that the terminal modification of oligonucleotides with eTNA confers marked resistance to exonucleases, irrespective of whether the modification is at the 3’-terminus, 5’-terminus, or both. Computational investigations revealed that the introduction of these modifications, which impart increased rigidity and altered nucleoside conformations, modulates the interactions between 3’-terminal nucleosides and phosphodiesterases, such as VPD, thereby impeding the formation of the catalytic transition state. Our work should benefit the rational design of end-capping nucleotides for oligonucleotide drugs, particularly aptamers and DNAzymes, thereby improving resistance to 3’-exonuclease degradation.

Methods

General

Unless otherwise specified, all non-aqueous reactions were conducted in dry glassware under argon or nitrogen gas balloon pressure. All chemicals and solvents were of laboratory grade as obtained from commercial suppliers and were used without further purification; anhydrous solvents were purchased as the highest grade. Organic solvents are designated as follows: EtOAc, ethyl acetate; CH2Cl2, dichloromethane; MeOH, methanol; THF, tetrahydrofuran. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was performed on TLC glass sheets covered with silica gel 60 F254. Flash column chromatography (FC): silica gel of 100–200 mesh or 200–300 mesh. NMR spectra were measured at 400 MHz for 1H, 101 MHz for 13C and 162 MHz for 31P. The J values are given in Hz; δ values are given in ppm relative to Me4Si as internal standard.

D-Erythronolactone (2)

To a precooled solution of D-isoascorbic acid (35.2 g, 0.2 mol) (1) in 500 mL of distilled H2O, Na2CO3 (42.4 g, 0.4 mol) was incrementally added in ten portions over a 20-min period, during which the evolution of CO2 was observed. Then, 30% aq. H2O2 (44 mL, 0.45 mol) was added dropwise to the resulting solution in ice bath. The reaction mixture was removed from ice bath and allowed to heat to 40 °C and stirred for another 1 h. After that, the reaction mixture was treated with 8.0 g of activated charcoal (200 mesh) and stirred at 40 °C until bubbles were no longer observed. The suspension was filtered through a pad of celite, and the filtered cake was washed by H2O (2 × 50 mL). The filtrate was cooled to 0 °C, and hydrochloric acid was added dropwise until the pH of solution reached 1, then the solvent was removed under reduced vacuum and further dried under high vacuum. The crude product was obtained as a white solid. Subsequently, 100 mL of EtOAc was added, and the suspension was heated to 90 °C with stirring. The hot suspension was filtered, and the filtrate was collected. This process was repeated five times. The filtrates were combined and concentrated, and crystallized at 4 °C overnight. After filtration, the compound 2 was obtained as a white crystal: yield 16.5 g (70%).1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 5.79 (s, 1H), 5.39 (s, 1H), 4.38 (d, J = 4.3 Hz, 1H), 4.28 (dd, J = 9.9, 3.0 Hz, 1H), 4.25–4.21 (m, 1H), 4.05 (d, J = 9.8 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 176.86, 72.24, 69.90, 68.83. HRMS: calcd for C4H6O4 [M + H+] 119.0339, found 119.0340.

2-O-Benzoyl-D-erythronolactone (3)

Compound 2 (9.8 g, 84.4 mmol) was dissolved in 90 mL of CH2Cl2 and 10 mL of pyridine, and then cooled to 0 °C, benzoyl chloride (10.7 mL, 92.84 mmol) was added dropwise and the mixture was stirred in 0 °C for 1 h. The mixture was concentrated under vacuum, and redissolved in 50 mL of EtOAc, washed with 1 N HCl (3 × 50 mL). The organic layer was collected and dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated, crystallized at 4 °C overnight. The mixture was filtered and compound 3 was obtained as a white crystal: yield 9.2 g (60%).1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.06 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.72 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.58 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 5.93 (s, 1H), 5.80 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 1H), 4.64 – 4.60 (m, 1H), 4.56 (dd, J = 10.0, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 4.24 (d, J = 9.9 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 172.69, 165.21, 134.34, 130.08, 129.29, 129.22, 73.47, 71.64, 67.59. HRMS: calcd for C11H10O5 [M + H+] 223.0601, found 223.0596.

2-O-Benzoyl-3-O-tert-butyldimethylsilyl-D-erythronolactone (4)

Compound 3 (12.0 g 54.0 mmol), imidazole (9.2 g, 135.1 mmol) and tert-butyldimethylchlorosilane (8.9 g, 59.4 mmol) were dissolved in 200 mL of CH2Cl2 and stirred overnight at room temperature. The mixture was concentrated under vacuum, and redissolved in 50 mL of EtOAc, washed with H2O (3 × 50 mL). The organic layer was collected and dried over Na2SO4 and then concentrated and separated through silica gel column chromatography (5:1 hexanes−EtOAc) and compound 4 was obtained as a colorless syrup: yield 16.4 g (90%).1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.85 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H), 7.40 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.26 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 5.65 – 5.54 (m, 1H), 4.40 (d, J = 5.3 Hz, 1H), 4.34 (dd, J = 11.2, 3.4 Hz, 1H), 4.29 (d, J = 11.1 Hz, 1H), 0.63 (s, 9H), 0.00 (s, 3H), -0.09 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 173.49, 165.59, 133.51, 129.89, 129.17, 128.46, 70.74, 69.09, 68.93, 25.41, 18.18, -4.90, -5.39. HRMS: calcd for C17H24O5Si [M + H+] 337.1466, found 337.1458.

1-O-Acetyl-2-O-benzoyl-3-O-tert-butyldimethylsilyl-D-erythrofuranose (5)

Compound 4 (10.0 g, 29.72 mmol) was dissolved in 150 mL of anhydrous THF, then the mixture was cooled to −78 °C in acetone/dry ice bath, diisobutylaluminumhydride (35.66 mL, 35.66 mmol, 1 M in hexanes) was added dropwise to the mixture with a syringe in 20 min. The mixture was stirred under nitrogen for additional 2.5 h at −78 °C, 5 mL of MeOH was added slowly with a syringe (evolution of bubble was observed). After 10 minutes, acetone/dry ice bath was removed and the reaction mixture was warm to room temperature, added with 100 mL of sat. aq. potassium sodium tartrate and 150 mL of EtOAc and further stirred overnight at room temperature. The mixture was extracted with EtOAc (3 × 50 mL), the organic layers were combined and dried over Na2SO4 and then concentrated.

The residue was dissolved in150 mL of CH2Cl2 and then cooled to 0 °C, 40 mg of 4-dimethylaminopyridine and Ac2O (3.07 mL, 32.69 mmol) were added to the solution. The ice bath was removed and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 4 h, and then concentrated. The residue was separated through a silica gel column chromatography (15:1 hexanes−EtOAc) and compound 5 was obtained as a white solid: yield 8.4 g (75%).1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.03 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 7.72 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.59 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 5.95 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 5.55 (q, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 4.61 (dd, J = 4.7, 2.7 Hz, 1H), 4.36 (dd, J = 10.0, 5.0 Hz, 1H), 4.12 (dd, J = 10.0, 3.4 Hz, 1H), 2.13 (s, 3H), 0.77 (s, 9H), 0.10 (s, 3H), 0.00 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 170.15, 165.59, 134.00, 129.83, 129.70, 129.21, 101.52, 75.63, 73.55, 70.56, 25.76, 21.33, 18.00, -4.86, -4.93. HRMS: calcd for C19H28O6Si [M + H+] 381.1728, found 381.1714.

1-(2’-O-Benzoyl-α-D-erythrofuranosyl)thymine (6a)

Compound 5 (4.14 g, 10.88 mmol) and thymine (1.44 g, 11.42 mmol) were dissolved in 30 mL of anhydrous acetonitrile, and N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)acetamide (5.86 mL, 23.94 mmol) was added. The mixture was stirred under nitrogen at room temperature until solids were completely dissolved, then TMSOTf (3.03 mL, 17.41 mmol) was added, and stirring at 60 °C for 1 h. The reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature, and 10 mL of sat. aq. NaHCO3 was added and stirred for another 1 h at room temperature. The suspension was filtered through a pad of celite, and the filter cake was washed by EtOAc (2 × 20 mL). The filtrate was combined and organic solvent was removed under vacuum. The residue was diluted with 50 mL of EtOAc, and washed with brine (3 × 20 mL). The organic layer was dried over Na2SO4 and EtOAc was removed under vacuum.

The residue was dissolved in 30 mL of THF, and triethylamine trihydrofluoride (3.55 mL, 21.76 mmol) was added. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight, and then concentrated. The mixture was flowed through silica gel column (50:1 CH2Cl2 − MeOH) and eluent fractions were collected and concentrated to dryness, a white solid was obtained. 15 mL of EtOAc was added, the mixture was heated with stirring until solids were completely dissolved. Compound 6a was crystallized from the solution at 4 °C overnight. After filtration, the product was obtained as a white solid: yield 2.9 g (80%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.40 (s, 1H), 8.06 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 7.69 (t, J = 6.3 Hz, 2H), 7.57 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 5.86 (dd, J = 12.5, 6.6 Hz, 2H), 5.53 (t, J = 3.6 Hz, 1H), 4.66 (q, J = 6.2 Hz, 1H), 4.53 (dd, J = 10.5, 3.9 Hz, 1H), 4.02 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 1.82 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 165.58, 164.19, 151.39, 137.42, 133.96, 130.04, 129.87, 129.21, 110.42, 88.80, 74.17, 72.56, 71.34, 12.49. HRMS: calcd for C16H16N2O6 [M + H+] 333.1081, found 333.1070.

1-(3’-O-dimethoxytrityl-α-D-erythrofuranosyl)thymine (7a)

A mixture of 6a (2.42 g, 7.28 mmol), 4,4’-dimethoxytrityl chloride (3.7 g, 10.92 mmol) and 40 mg of 4-dimethylaminopyridine was co-evaporated with anhydrous pyridine (2 × 20 mL) before dissolution in 20 mL of anhydrous pyridine, and the reaction mixture was stirred at 80 °C for 6 h. The solvent was removed under vacuum, and the residue was redissolved in 50 mL of EtOAc, which was washed with brine three times (3 × 50 mL). The organic layer was collected and dried over Na2SO4 and then concentrated.

The residue was dissolved in a mixture of 15 mL of THF and 12 mL of MeOH, and then stirring at ice bath, added 7.2 mL of ice-cold 1 N aq. NaOH. After 1 h, another 7.2 mL of ice-cold 1 N aq. NaOH was added, and ice bath was removed and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight. After that, the reaction was quenched with 36 mL of 10% aq. NH4Cl, and the volatile solvent was removed under vacuum. Then, the residue was diluted with 30 mL of EtOAc, and washed with brine (3 × 50 mL). The organic layer was collected and dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated. Purification by silica gel column chromatography (100:1 CH2Cl2 − MeOH) gave compound 7a as yellow solid: yield 3.09 g (80%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.13 (s, 1H), 7.44 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 7.32 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.28 – 7.15 (m, 5H), 7.09 (s, 1H), 6.78 (dd, J = 19.1, 8.9 Hz, 4H), 5.90 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 5.76 (s, 1H), 5.00 (d, J = 4.5 Hz, 1H), 4.37 (dd, J = 6.9, 4.3 Hz, 1H), 4.06 (dd, J = 9.4, 2.6 Hz, 1H), 3.70 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 6H), 3.65 (d, J = 9.5 Hz, 1H), 1.63 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 164.18, 158.66, 158.57, 151.10, 145.94, 137.68, 136.31, 135.97, 130.68, 130.44, 128.21, 128.06, 127.07, 113.37, 113.28, 88.44, 86.96, 76.23, 75.03, 70.29, 55.38, 12.27. HRMS: calcd for C30H30N2O7 [M + Na+] 553.1945, found 553.1924.

1-(3’-O-Dimethoxytrityl-α-D-erythrofuranosyl)thymine 2’-(2-cyanoethyl)-N,N-diisopropylphosphoramidite (8a)

Compound 7a (1.26 g, 2.37 mmol) in 15 mL of anhydrous CH2Cl2 was pre-cooled in ice bath, and N,N-diisopropylethylamine (2.07 mL, 11.85 mmol) was added, and the mixture was stirred in ice bath. After that, 2-cyanoethyl N,N-diisopropylchlorophosphoramidite (1.06 mL, 4.74 mmol) was added dropwisely, ice bath was removed and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature. After 1 h, the reaction was quenched with 10 mL of sat. aq. NaHCO3, and the mixture was washed with sat. aq. NaHCO3 (3× 20 mL). The organic layer was dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated. Purification by silica gel column chromatography (1:1 hexanes−EtOAc with 0.1% Et3N) gave compound 8a as a white foam: yield 1.25 g (72%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 8.25 (s, 1H), 7.48 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 7.39 - 7.32 (m, 4H), 7.26 - 7.20 (m, 3H), 6.82 - 6.76 (m, 4H), 6.53 (s, 1H), 5.62 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H), 4.85 (dd, J = 6.6, 4.3 Hz, 1H), 4.17 - 4.12 (m, 2H), 4.03 – 3.97 (m, 1H), 3.90 – 3.85 (m, 1H), 3.79 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 6H), 3.73 (dd, J = 6.7, 3.5 Hz, 1H), 2.67 – 2.61 (m, 2H), 1.80 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 3H), 1.66 (s, 2H), 1.26 - 1.21 (m, 12H); 31P NMR (162 MHz, CDCl3) δ 151.29, 148.57. HRMS: calcd for C39H47N4O8P [M + H+] 731.3204, found 731.3175.

Bovine spleen phosphodiesterase II (SPD) resistance assay

3 μg of eTNA-T-5’, INV-T-5’, TNA-T-5’ or DNA-T-5’ was treated with Phosphodiesterase II from bovine spleen (12.6 mU/µL, 1.2 μL) in 10 µL reaction buffer (CaCl2 100 mM, sodium succinate 300 mM, pH 6.0) at 37 °C for different time intervals, and then heated at 90 °C for 5 min to stop the reactions. Then, the samples were mixed with 10 µL stop buffer (8 M urea, 5 mM Tris-HCl, 20 mM EDTA, pH 7.5), analyzed on 15% denaturing PAGE gels, stained with GelRed, and visualized with a Bio-Rad gel imager (GelDoc XR+). The images were analyzed with ImageJ.

Snake venom phosphodiesterase I (VPD) resistance assay

1 μg of eTNA-T-3’, INV-T-3’, TNA-T-3’ or DNA-T-3’ (R-eTNA-T-3’, R-INV-T-3’, R-TNA-T-3’ or Native RNA) was treated with phosphodiesterase I (2 mU/µL, 0.5 μL) from Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake Venom in 10 µL reaction buffer (50 mM Tris-Borate, 7 mM MgCl2, pH 7.5) at 37 °C for different time intervals, and then heated at 90 °C for 5 min to stop the reactions. Then, the samples were mixed with 10 µL stop buffer (8 M urea, 5 mM Tris-HCl, 20 mM EDTA, pH 7.5), analyzed on 15% denaturing PAGE gels, stained with GelRed, and visualized with a Bio-Rad gel imager (GelDoc XR+). The images were analyzed with ImageJ.

50%Human serum resistance assay

500 ng of eTNA-T-3’, INV-T-3’, TNA-T-3’, DNA-T-3’, eTNA-T-5’, INV-T-5’, TNA-T-5’, DNA-T-5’, eTNA-T-5'3’, INV-T-5'3’, TNA-T-5'3’ or DNA-T-5'3’ was treated with 50% Human serum (HS) in 10 µL PBS reaction buffer at 37 °C for different time intervals, and then heated at 90 °C for 5 min to stop the reactions. Then, the samples were mixed with 10 µL stop buffer (8 M urea, 5 mM Tris-HCl, 20 mM EDTA, pH 7.5), analyzed on 15% denaturing PAGE gels, stained with GelRed, and visualized on a Bio-Rad gel imager (GelDoc XR+). The images were analyzed with ImageJ.

Data availability

The data supporting this study are available in the manuscript, the Supporting Information and Supplementary Data.

References

Gökirmak, T. et al. Overcoming the challenges of tissue delivery for oligonucleotide therapeutics. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 42, 588–604 (2021).

Miao, Y. et al. Current status and trends in small nucleic acid drug development: leading the future. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 14, 3802–3817 (2024).

Uhlmann, E. & Peyman, A. Antisense oligonucleotides: a new therapeutic principle. Chem. Rev. 90, 543–584 (1990).

Khvorova, A. & Watts, J. K. The chemical evolution of oligonucleotide therapies of clinical utility. Nat. Biotechnol. 35, 238–248 (2017).

Keefe, A. D., Pai, S. & Ellington, A. Aptamers as therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 9, 537–550 (2010).

Baum, D. A. & Silverman, S. K. Deoxyribozymes: useful DNA catalysts in vitro and in vivo. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65, 2156–2174 (2008).

Santoro, S. W. & Joyce, G. F. A general purpose RNA-cleaving DNA enzyme. PNAS 94, 4262–4266 (1997).

Lu, M. et al. Overcoming pharmaceutical Bottlenecks for nucleic acid drug development. Acc. Chem. Res. 56, 224–236 (2023).

Egli, M. & Manoharan, M. Chemistry, structure and function of approved oligonucleotide therapeutics. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, 2529–2573 (2023).

Kilanowska, A. & Studzińska, S. In vivo and in vitro studies of antisense oligonucleotides - a review. RSC Adv. 10, 34501–34516 (2020).

Nair, J. K. et al. Impact of enhanced metabolic stability on pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of GalNAc–siRNA conjugates. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, 10969–10977 (2017).

Schöning, K.-U. et al. Chemical etiology of nucleic acid structure: the α-Threofuranosyl-(3’→2’) oligonucleotide system. Science 290, 1347–1351 (2000).

Zaitseva, M. et al. Conformation and thermostability of oligonucleotide d(GGTTGGTGTGGTTGG) containing thiophosphoryl internucleotide bonds at different positions. Biophys. Chem. 146, 1–6 (2010).

Schubert, S. et al. RNA cleaving ‘10-23’ DNAzymes with enhanced stability and activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 5982–5992 (2003).

Liu, Y. et al. Chemical evolution of ASO-like DNAzymes for effective and extended gene silencing in cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 53, gkaf144 (2025).

Nguyen, K., Malik, T. N. & Chaput, J. C. Chemical evolution of an autonomous DNAzyme with allele-specific gene silencing activity. Nat Commun. 14, 2413 (2023).

Bramsen, J. B. et al. A large-scale chemical modification screen identifies design rules to generate siRNAs with high activity, high stability and low toxicity. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, 2867–2881 (2009).

Yamada, K. et al. Enhancing siRNA efficacy in vivo with extended nucleic acid backbones. Nat. Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-024-02336-7 (2024).

Shaw, J.-P. et al. Modified deoxyoligonucleotides stable to exonuclease degradation in serum. Nucleic Acids Res. 19, 747–750 (1991).

Chen, H. et al. Branched chemically modified poly(A) tails enhance the translation capacity of mRNA. Nat. Biotechnol. 43, 194–203 (2025).

Kratschmer, C. & Levy, M. Effect of chemical modifications on aptamer stability in serum. Nucleic Acid Ther. 27, 335–344 (2017).

Ortigão, J. F. et al. Antisense effect of oligodeoxynucleotides with inverted terminal internucleotidic linkages: a minimal modification protecting against nucleolytic degradation. Antisense Res. Dev. 2, 129–146 (1992).

Beigelman, L. et al. Chemical modification of hammerhead ribozymes. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 25702–25708 (1995).

Matsuda, S. et al. Shorter is better: the α-(l)-threofuranosyl nucleic acid modification improves stability, potency, safety, and Ago2 binding and mitigates off-target effects of small interfering RNAs. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 19691–19706 (2023).

Qin, B. et al. Enzymatic synthesis of TNA protects DNA nanostructures. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 63, e202317334 (2024).

Culbertson, M. C. et al. Evaluating TNA stability under simulated physiological conditions. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 26, 2418–2421 (2016).

Wang, Y., Nguyen, K., Spitale, R. C. & Chaput, J. C. A biologically stable DNAzyme that efficiently silences gene expression in cells. Nat. Chem. 13, 319–326 (2021).

de la Torre, B. G. & Albericio, F. The pharmaceutical industry in 2023: an analysis of FDA drug approvals from the perspective of molecules. Molecules 29, 585 (2024).

Ni, S. et al. Recent progress in aptamer discoveries and modifications for therapeutic applications. Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 9500–9519 (2021).

Brautigam, C. A. & Steitz, T. A. Structural principles for the inhibition of the 3’-5’ exonuclease activity of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I by phosphorothioates. J. Mol. Biol. 277, 363–377 (1998).

Teplova, M. et al. Structural origins of the exonuclease resistance of a zwitterionic RNA. PNAS 96, 14240–14245 (1999).

Kumar, P. et al. Chimeric siRNAs with chemically modified pentofuranose and hexopyranose nucleotides: altritol-nucleotide (ANA) containing GalNAc–siRNA conjugates: in vitro and in vivo RNAi activity and resistance to 5’-exonuclease. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, 4028–4040 (2020).

Pan, C.-T. et al. The evolution and structure of snake venom phosphodiesterase (svPDE) highlight its importance in venom actions. eLife 12, e83966 (2023).

Ullah, A. et al. The sequence and a three-dimensional structural analysis reveal substrate specificity among snake venom phosphodiesterases. Toxins 11, 625 (2019).

Curley, J. F., Joyce, C. M. & Piccirilli, J. A. Functional evidence that the 3’-5’ exonuclease domain of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I employs a divalent metal ion in leaving group stabilization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119, 12691–12692 (1997).

Hausmann, J. et al. Structural snapshots of the catalytic cycle of the phosphodiesterase Autotaxin. J. Struct. Biol. 195, 199–206 (2016).

Kato, K. et al. Structural insights into cGAMP degradation by Ecto-nucleotide pyrophosphatase phosphodiesterase 1. Nat. Commun. 9, 4424 (2018).

Ebert, M.-O. The structure of a TNA−TNA complex in solution: NMR study of the octamer duplex derived from α-(L)-Threofuranosyl-(3’-2’)-CGAATTCG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 15105–15115 (2008).

Sau, S. P. et al. A scalable synthesis of α-L-threose nucleic acid monomers. J. Org. Chem. 81, 2302–2307 (2016).

Cohen, N. et al. Enantiospecific syntheses of leukotrienes C4, D4, and E4, and [14,15-3H2] leukotriene E4 dimethyl ester. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 105, 3661–3672 (1983).

Xiong, C. et al. Synthesis and immunological studies of oligosaccharides that consist of the repeating unit of streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 3 capsular polysaccharide. Chem. Eur. J. 24, 8205–8216 (2018).

Dumbre, S. G., Jang, M.-Y. & Herdewijn, P. Synthesis of α-L-threose nucleoside phosphonates via regioselective sugar protection. J. Org. Chem. 78, 7137–7144 (2013).

Pirrung, M. C., Shuey, S. W., Lever, D. C. & Fallon, L. A convenient procedure for the deprotection of silylated nucleosides and nucleotides using triethylamine trihydrofluoride. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 4, 1345–1346 (1994).

Bommarito, S., Peyret, N. & SantaLucia, J. Jr Thermodynamic parameters for DNA sequences with dangling ends. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 1929–1934 (2000).

Isaksson, J. & Chattopadhyaya, J. A uniform mechanism correlating dangling-end stabilization and stacking geometry. Biochemistry 44, 5390–5401 (2005).

Ilankumaran, P. et al. Patterns of resistance to exonuclease digestion of oligonucleotides containing polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon diol epoxide adducts at N6 of deoxyadenosine. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 14, 1330–1338 (2001).

Wójcik, M. et al. Nucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase 1 is responsible for degradation of antisense phosphorothioate oligonucleotides. Oligonucleotides 17, 134–145 (2007).

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the Mei laboratory for helpful suggestions and comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by the following funding: National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2022YFF1201800); Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Synthetic Genomics (2023B1212060054); Shenzhen Key Laboratory of Synthetic Genomics (ZDSYS201802061806209); Shenzhen Institute of Synthetic Biology Scientific Research Program (JCHZ20210002). We are grateful to the Shenzhen Infrastructure for Synthetic Biology for instrument support and technical assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.M., W.M., X.H. and C.X. conceived the project and designed the experiments. J.W., X.C., Z.D., C.Z., M.L. and C.Y. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the preparation and editing of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wen, J., Zhang, C., Chen, X. et al. An epimer of threose nucleic acid enhances oligonucleotide exonuclease resistance through end capping. Commun Chem 8, 144 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01545-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01545-8