Abstract

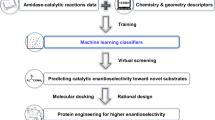

In recent years, industrial biocatalysis has significantly advanced, largely due to innovations in DNA sequencing, bioinformatics, and protein engineering. However, the challenge of implementing biocatalysis at an industrial scale while ensuring sustainability and cost-effectiveness remains a critical barrier. This study presents the development of a flash thermal racemization protocol for chemoenzymatic dynamic kinetic resolution (FTR-CE-DKR) of chiral amines, encompassing an investigation of substrate scope, catalyst screening, and optimization studies. The outcomes of this research facilitated the successful scale-up of an industrially relevant amide within a recycle-batch platform, achieving unprecedented scales of up to 100 grams and space-time yield (STY) values of up to 73.2 g L⁻¹ h⁻¹. Furthermore, the process exhibited very favorable sustainability metrics when benchmarked against previous reports, including atom economy, reaction mass efficiency, and process mass intensity. These findings represent a significant milestone in the biocatalytic production of optically active amines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chiral amines are important for the manufacturing of high-value chemicals, including active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and agrochemicals. Consequently, synthesis of these chiral building blocks has always been a highly topical and industrially relevant subject, with transition metal-catalyzed asymmetric (transfer) hydrogenation1,2 and biocatalysis3,4 as two of the most common approaches. The former may be considered as a more mature industrial technology5,6,7,8, where TON > 107 and TOF of >200 s−1 were reported recently9. In comparison, biocatalytic reactions are less productive and are more challenging to scale up10,11,12,13. Nevertheless, enzymes are generally regarded to be more sustainable than transition metal catalysts14, as it avoid the use of precious metal catalysts and expensive chiral ligands.

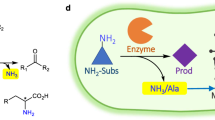

To date, one of the most successful industrial biocatalytic processes is the ChiPros process, developed by BASF in 200115. For the past two decades, the technology has been adopted across several manufacturing sites for the production of optically active amines, including a herbicide intermediate, with a total annual production of between 3 and 5 kt16. The overall process comprises of 3 steps (demonstrated in Scheme 1 using a generic 1-arylethylamine, 1):

1) The biocatalytic kinetic resolution of a racemic mixture of amine (RS)-1 in the presence of a lipase and a methoxyacetic acid ester, 3, as the acylating agent. The reaction proceeds to the theoretically maximum 50% conversion, affording the resolved amide (R)-2 in near-perfect optical purity of 99.5% ee. The mixture of (R)-2 and (S)-1 can be separated by distillation.

2) (R)-2 is hydrolyzed under basic conditions to liberate the amine (R)-1, which can be purified by distillation, while the sodium salt of methoxyacetic acid byproduct can be recovered and recycled.

3) Up to this point of the process, the racemate has been kinetically resolved into its constituent enantiomers. In practice, however, one enantiomer is often more valuable than the other. To minimize waste, the unwanted enantiomer can be racemized in the presence of catalytic amounts of acetophenone and a strong base via a Schiff base anion. After distillation, the resultant racemate can be combined with the original feedstock in step 1 for the lipase-catalyzed kinetic resolution.

While the ChiPros process is highly efficient, the need for a separate process to recycle the unwanted enantiomer (step 3) requires additional units of operation and resources, including multiple energy-intensive distillations for the isolation and recovery of amines. Furthermore, the method for recycling the unwanted enantiomer is not universally applicable, especially for secondary or tertiary amines.

In contrast, a chemoenzymatic dynamic kinetic resolution (CE-DKR) process can potentially offer a more sustainable alternative, whereby the lipase-catalyzed kinetic resolution is combined with a (chemo)catalyst that can selectively racemize the chiral center of the amine, such that the desired enantiomer can be obtained as the resolved amide with a theoretical yield of 100% (Scheme 2).

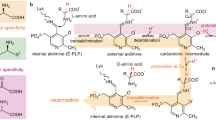

In principle, chiral amines containing an α-H can be racemized by reversible hydrogenation-dehydrogenation steps (Scheme 3). A number of homogenous and heterogeneous17,18 transition metal catalysts, including Ni19,20, Pd21,22,23,24,25, Ru26,27, Ir28,29,30,31, and even certain enzymes32,33,34,35, have been reported to be effective in scrambling the stereocenter. For the racemization of primary amines, the imine intermediate I could be arrested by another molecule of the primary amine to form secondary imine 4 and amine 5; the latter as a mixture of diastereoisomers. To suppress the formation of these side products, racemization is often conducted under an atmosphere of H2, or in the presence of a base additive. However, the presence of these additives shifts the position of the equilibrium, resulting in slower rate of racemization and prolonged reaction times.

Given that lipase-catalyzed resolution of amines is very efficient with selectivity factors, E, often >200, much of the research has been focused on the design of racemization catalysts that can operate synergistically under the same conditions as the biocatalyst in ‘one-pot’36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44. To avoid thermal degradation of the biocatalyst, the one-pot reactions were invariably performed at temperatures that are sub-optimal for the metal-catalyzed racemization, resulting in slow processes that are not useful for scale up. In a seminal review by Verho and Bäckvall in 201545, the compatibility between the enzyme and the racemization catalyst was identified as a critical issue for CE-DKR processes.

Prior to our work, there were only two attempts to compartmentalize the catalysts, so that each of them can operate independently under optimized and kinetically compatible conditions (Table 1). The first example of this approach was reported by De Miranda et al.46, where kinetic resolution of 1-phenylethylamine (1a) was achieved by a lipase in a packed bed reactor (PBR) at room temperature, while the racemization was performed in a continuous-stirred tanked reactor (CSTR) using a supported Pd catalyst at 70 °C (Entry 1, Table 1). In this hybrid system, the addition of ammonium formate was necessary to suppress the formation of side-products, but catalyst deactivation was a significant issue. Following this, Farkas et al. reported a single-pass flow system47, where a mixture of the racemic 1a, acylating reagent and ammonium formate was first passed through a PBR of the sol-gel immobilized lipase, followed by a mixed-bed PBR containing both the lipase and the racemization catalysts (Entry 2). However, as both reactors were operated isothermally at 60 °C, it does not offer any significant advantages over a “one-pot” system, and the productivity remained low. More recently, we disclosed an original method of achieving CE-DKR in a flow system, where the racemization of amine was facilitated under “flash thermal racemization” (FTR) conditions without any extraneous additives (Entry 3)48. This represented an original approach, whereby good reactivity and selectivity of amine racemization can be achieved by applying a short residence time at high temperature (9 s, 140 °C). Using this method, we were able to perform the CE-DKR of amines on a 1 g scale in 1 h.

In order to provide a fair comparison between (recycle)batch and single-pass operations, space-time-yield calculations were performed using the following equation (Eq. 1), where the total volume of solvent used to produce a specific quantity of product is utilized, rather than the volume of the reactor(s). Given that the use of solvent is always a substantial contributor to process mass intensity of a process (PMI), the resultant STY value will also reflect the sustainability of the process. Using this comparison, the FTR methodology does not compare so favorably, due to the large amount of solvent used, although the amount of Pd used is much lower than the other two processes.

Subsequently, the FTR process was explored further using DoE and transient flow methods, where relationships between temperature, amine concentration and flow rate with e.e. (%) and selectivity (%) were delineated (3 factors, 2 responses)49. The study revealed that the rate of racemization is strongly dependent on temperature, while the selectivity of the process was dependent on both temperature and flow rate/residence time. Remarkably, the initial concentration of the amine was not found to have a significant effect on the selectivity of the process, which bodes well for process intensification. In this paper, we will report the demonstration of the FTR-enabled CE-DKR methodology to the sustainable kinetic resolution of a chiral primary amine at scales up to 100 g—an unprecedented scale reported for the DKR of chiral amines.

Results and discussion

Building upon our earlier success48, we sought to further validate the potential for this methodology to synthesize a range of industrially relevant compounds, focusing on compounds synthesized by the ChiPros® process, as well as other bioactive building blocks. Given that the kinetic resolution is enzyme-specific, only the generality of the FTR by Pd/γ-Al2O3 is presented here (Table 2 and Section S2.1.1 in the Supplementary Info). As temperature was found to be the dominant effect49, the racemization of each substrate was performed at 140, 185, and 230 °C, while the residence time was held constant (9 s).

The overall trend is in keeping with previous reports of Pd racemization catalysts21,22,23,24,25: For the racemization of primary benzylic substrates 1a-1f (entries 1–6), both electron-donating and withdrawing substituents can be accommodated, with the exception of chloride (entries 4 and 5), where no racemization was observed, even at 230 °C. The racemization is enhanced by introducing an N-substituent (entry 1 vs entry 8), but the racemization of the tertiary amine 1i was much slower (entry 9), and the aliphatic amine 1k did not racemize under these conditions (entry 11). Last but not least, chiral amines containing pharmacophore-like structures were also tested N-containing hetero- (1j) and carbo-cyclic structures (1m and 1n); the latter were found to racemize readily at 140 °C (entries 12–14).

During the exploration of substrate scope, (R)-(+)-1-(3-methoxyphenyl)ethylamine (1c) was identified as a suitable candidate for demonstrating the scalability of the FTR-DKR methodology. It is one of the chiral amines currently produced through the ChiPros® process, and serves as a valuable intermediate used in dietary supplements and formulation of personal care products. Moreover, it is a precursor for the synthesis of Tecalcet—an orally active calcimimetic compound used in the treatment of hyperparathyroidism50.

Previous research into the asymmetric synthesis of 1c provided useful benchmarks for our work. Notably, Han et al. reported a one-pot batch process incorporating catalytic hydrogenation and chemoenzymatic dynamic kinetic resolution (Scheme 4)51, whereby Pd/AlO(OH) was combined with a slight H2 pressure to facilitate the reversible reduction of oxime 6 to 1c. At the same time, CALB catalyzed the enantioselective acylation of (R)-1c using methyl 2-methoxylacetate (3a), a process that requires 3 days to produce just over 1 g of the chiral amide (2c). More recently, Tan et al described an enantioselective reductive amination of the arylmethyl ketone (7), catalyzed by a chiral phosphine-ligated ruthenium catalyst under H2 atmosphere52. The larger-scale reaction was exemplified by the use of only 750 mg of the ketone, affording 670 mg of (R)-1c in 89% yield and 94% e.e. after 1 day. The requirement for a very high H2 pressure (57 bar), alongside the use of toxic and environmentally hazardous fluorinated solvent (TFE), presents significant challenges for the translation of this methodology into a commercially viable process.

In our preliminary investigation, a total of 18 heterogeneous transition metal catalysts were systematically evaluated for their efficacy in racemizing (S)-1a, using a screening deck reactor (Section S.2.1.2 of the Supplementary Info). The results of this catalyst screening indicated that supported palladium (Pd) and platinum (Pt) catalysts exhibited particularly high levels of catalytic activity. Following this initial assessment, these two catalyst types were further investigated for their ability to racemize (R)-1c, and the findings are presented in Table 3.

Among the three Pd catalysts evaluated (Table 3, entries 1–3), the highest degree of racemization, indicated by the lowest enantiomeric excess (e.e.), was observed with both Pd(OH)2/C (Pearlman’s catalyst) and Pd/C. In contrast, the Pd/γ-Al2O3 catalyst was able to suppress side product formation much more effectively (100% selectivity), compared to its carbon-supported counterparts (entries 2 and 3 vs. entry 1). The acid-base properties of Pd catalysts were reported to significantly influence both the rate and selectivity of the racemization of chiral amines52. Hence, the enhanced activity of Pd(OH)₂/C can be attributed to the basic characteristics of PdO, which promote the formation of surface amide intermediates (Scheme 5). Conversely, the observed low selectivity with the catalyst supported on carbon (ca. 45%) may be linked to the high surface area and effective adsorption properties of activated carbon, which retain imine and amide intermediates on the surface, thereby facilitating intermolecular reactions that yield undesirable side products.

In comparison, the racemization of amines over Pt catalysts occurred at a considerably slower rate (entries 4 and 5). Once again, the selectivity was notably inferior when employing carbon support in contrast to alumina. From this limited catalyst screening (Table 3), we can surmise that the redox properties of the metal nanoparticles play a critical role in determining the extent of racemization (e.e), while the nature of the support significantly influences the selectivity outcomes.

The superior selectivity demonstrated by Pd/γ-Al2O3 led us to select it as the preferred catalyst for the racemization of (R)-1c. In contrast to our earlier studies conducted using dilute amine solutions (<100 mM)48,49, the FTR study in this work was performed using a synthetically useful amine concentration (0.25–1 M). Subsequently, a DoE model consisting of a 25-experiment I-optimal split-plot screen was generated to examine the racemization of (R)-1c (0.25–1 M) between 120 and 240 °C and residence times of between 4 and 20 s (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 3 of the Supplementary Info).

The findings from the DoE study closely mirror our previously conducted studies. Specifically, selectivity can be enhanced by reducing the residence time, effectively suppressing the formation of side products, whereas variations in temperature and amine concentration did not yield any significant impact on selectivity. Conversely, the racemization of (R)-1c (e.e.) displayed a strong dependence on temperature and flow rate, whereas amine concentration appeared to exert no influence on this process. Such “pseudo-zero order” observed for the amine may be ascribed to the small amount of accessible active catalytic sites in the packed bed (only 200 mg of the catalyst was used) compared to the large quantity of amine (0.25–1 M) in a single pass, i.e., the adsorption of the system is saturated.

To check for catalyst deactivation, selected experiments from the initial set of twenty-five were repeated both within and in addition to the DoE experiments (Supplementary Info Table 4, Supplementary Info). The results showed very good reproducibility, proving that Pd catalyst remained stable over the course of these experiments. The DoE model predicted a potential optimum for the racemization of (R)-1c at 230 °C in 4 s, to afford 1c with 41% e.e. and 94% selectivity. Pleasingly, this aligned extremely well with experimental results, where 1c was obtained in 38% e.e. and 91% selectivity under the stated conditions.

Most significantly, the DoE study suggests that it is possible to utilize a highly concentrated solution of amine at high flow rates (short residence time) with no detectable catalyst deactivation, which are important criteria for process intensification. Encouraged by these results, the racemization of a 1 M solution of (R)–1c was performed on a larger scale (15 g) in a batch-recycle process (Fig. 2). Over 80 min, the enantiomeric excess of the amine was reduced to 4% e.e. with an overall selectivity of 80% (blue datapoints). Using the same amount of the Pd catalyst (200 mg), the process was subsequently scaled up ten-fold to 150 g, whereupon the e.e. of (R)-1c can be reduced to 6% in 15 h (orange data points), and the primary amine can be recovered in 82% yield.

Next, the kinetic resolution of (rac)-1c by methyl 2-methoxyacetate (3a) catalyzed by Novozym-435 in a packed-bed reactor was also optimized using DoE. Setting the flow rate at 5 mL min−1 to align with the racemization step, the effect of temperature (20–70 °C), acyl donor equivalents (0.5–2) and amine concentration (0.25–1 M) on conversion and e.e. were explored (Fig. 3 and Table S5 of Supplementary Info). The model created showed a high level of precision and demonstrated that 42% conversion could be achieved in a single pass using 1 M of (rac)-1c, two equivalents of 3a at 70 °C, affording the kinetically resolved amide product 1c with excellent optical purity (99% e.e.).

Finally, the two PBRs were combined in tandem in a recycle-batch system, where the reactants were recycled continuously via a reservoir (Fig. 4 and Section 4.4 in Supplementary Info). Previously, molecular sieves were deployed to remove the methanol byproduct which can cause deactivation of the catalyst. To cater for the increase in reaction scale, the molecular sieves were replaced by a distillation column fitted to the reaction reservoir, which was heated at 70 °C during the reaction, to extract methanol from the reaction mixture continuously (methanol forms an azeotrope with toluene at 64 °C, with an approximate 12% toluene content).

This system was used initially tested using 10 g of (rac)-1c. We were delighted to see that the system was able to convert 91% of the amine to the desired (R)-2c with 96% e.e. and 84% selectivity in 2 h and 20 min. Encouraged by this, the process was attempted on a 100 g scale. For operational reasons, the reaction was conducted over 4 days only during working hours; during which aliquots from the reservoir were extracted every hour and analyzed, before the system was shut down overnight (indicated by gray vertical lines in Fig. 5). Despite these interruptions, catalytic turnovers were able to resume after each scheduled downtime. After 14 hours of operation, the reaction proceeded to 95% conversion with excellent retention of the optical purity of the amide (99% e.e.). However, a noticeable decrease in the selectivity for the primary amine was detectable, decreasing to 96% after ca. 5 h, and 88% after 8 h. We attribute this erosion of selectivity to the presence of high concentration of the amide product in the reaction mixture (ca. 60% at 5 h), which may competitively bind with the enzyme active site, reducing the rate of kinetic resolution, allowing the formation of side products to become competitive.

In an authoritative review on industrial biocatalysis by Bornscheuer and co-workers53, (recently updated54) the range of STYs of industrial processes was reported between the range of 0.001–0.3 kg L−1 h−1, and values exceeding 10 g L−1 h−1 are rare. Using this as a benchmark, the productivity values of known literature reports of CE-DKR of chiral amines, performed on ≥1 g of the racemic precursor, are collated in Table 4. Once again, to ensure fair comparison between “one-pot” (entries 2, 3, and 5) and recycle-batch processes, the total amount of solvents deployed in the process was deployed as the volume element in the calculation of STY’s (Eq. 1), rather than the size of the reactor, which will intrinsically favor the batch-recycle system.

The calculations show that the FTR methodology delivered a STY of 73.2 g L−1 h−1 for the reaction performed with 10 g of the amine (Table 4, entry 6), which is the highest reported to date for the CE-DKR of chiral amines. Using the same amounts of catalysts (200 mg and 3 g of the chemo- and bio-catalysts, respectively) for the 10-fold scaleup, the STY decreases to 13.6 g L−1 h−1 (entry 7) as may be expected, but still well within the productivity expected of an industrial scale process, without compromising the optical purity of the resolved amide (99% ee). While this may be lower than the STY calculated for the one-pot synthesis of a different chiral amine 10 reported by Jia (entry 5), it is important to note that the amounts of catalysts deployed by the FTR protocol were also substantially lower than the one-pot procedure (200 mg vs 27.5 g for Pd, and 3 g vs 18.3 g for the biocatalyst). Given that the price of precious metal catalysts is a significant contributor to the cost of goods, this result can be considered as a milestone for chemoenzymatic kinetic dynamic resolution of chiral amines.

Last but not least, the Green Chemistry metrics of these gram-scale reactions were compared using the CHEM21 toolkit, including atom economy (AE), reaction mass efficiency (RME) and process mass intensity (PMI) (Table 5)55. Comparing the result from this work (entries 6 and 7) from our preliminary work (entries 1 and 3), improvements across all the metrics have been achieved. What is particularly notable is the PMI value of <7, which is among the lowest recorded for this process.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have shown that the flash-thermal racemization protocol can be successfully scaled up to 100 g and demonstrated that the FTR methodology outperforms previously reported catalytic systems in a quantifiable way, in terms of productivity, green chemistry metrics, and cost-effectiveness, setting a new milestone for the industrial production of optically active amines by CE-DKR methods. However, the study also highlighted areas where further development work is needed; namely, reduced selectivity at high amide conversion. Potential amide inhibition may be addressed by modifying the reactor design to separate the optically active amide from the unresolved amine following kinetic resolution, for example. Work is currently underway to utilize the data collected in this work to design different reactor systems, as well as technoeconomic and sustainability assessments, which we hope to report in due course.

Methods

100 g scale FTR-CE-DKR of R–2-methoxy-N-(1-(3-methoxyphenyl)ethyl)acetamide, (R)-2c

The reactor was primed by anhydrous toluene at 1 mL min−1 for 10 min, before the KR and FTR reactors were heated to 70 °C and 230 °C, respectively. Once the desired temperatures were reached, the inlet was switched to the delivery a solution of (rac)–1c (100 g, 661 mmol) and methyl 2-methoxyaceate, 3a (138 g, 2 equiv.) in toluene (661 mL, 1 M) from a 1 L, 3-necked RB flask fitted with a distillation column. During the reaction, the RB flask was heated and stirred at 70 °C to remove the MeOH by-product via azeotropic distillation. After 14 h, the reaction reached 95% conversion and 90% selectivity (HPLC). The reaction mixture was cooled down, washed with 2 M HCl (3 × 50 mL), dried with MgSO4, filtered, and reduced in vacuo to yield (R)-2c as an orange oil (101 g, 68%, 99% e.e.).

Data availability

Data generated during the study are either included in the Supplementary Information or available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Zhang, X. & Shao, P.-L. Industrial applications of asymmetric (transfer) hydrogenation. in Asymmetric Hydrogenation and Transfer Hydrogenation 175–219 (Wiley, 2021).

Shi, Y., Rong, N., Zhang, X. & Yin, Q. Synthesis of chiral primary amines via enantioselective reductive amination: from academia to industry. Synthesis 55, 1053–1068 (2023).

Simić, S. et al. Shortening synthetic routes to small molecule active pharmaceutical ingredients employing biocatalytic methods. Chem. Rev. 122, 1052–1126 (2022).

O’Connell, A. et al. Biocatalysis: landmark discoveries and applications in chemical synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 53, 2828–2850 (2024).

Johnson, N. B., Lennon, I. C., Moran, P. H. & Ramsden, J. A. Industrial-scale synthesis and applications of asymmetric hydrogenation catalysts. Acc. Chem. Res. 40, 1291–1299 (2007).

Shimizu, H., Nagasaki, I., Matsumura, K., Sayo, N. & Saito, T. Developments in asymmetric hydrogenation from an industrial perspective. Acc. Chem. Res. 40, 1385–1393 (2007).

Cotarca, L., Verzini, M. & Volpicelli, R. Catalytic asymmetric transfer hydrogenation: an industrial perspective. Chim. Oggi. 32, 36–41 (2014).

Genêt, J. P., Phansavath, P. & Ratovelomanana-Vidal, V. Asymmetric hydrogenation: design of chiral ligands and transition metal complexes. synthetic and industrial applications. Isr. J. Chem. 61, 409–426 (2021).

Yin, C. C. et al. A 13-million turnover-number anionic Ir-catalyst for a selective industrial route to chiral nicotine. Nat. Commun. 14, 3718 (2023).

Hauer, B. Embracing nature’s catalysts: a viewpoint on the future of biocatalysis. ACS Catal. 10, 8418–8427 (2020).

Tufvesson, P., Fu, W., Jensen, J. S. & Woodley, J. M. Process considerations for the scale-up and implementation of biocatalysis. Food Bioprod. Process 88, 3–11 (2010).

Vikhrankar, S. S. et al. Enzymatic routes for chiral amine synthesis : protein engineering and process optimization. Biol. Targets Ther. 18, 165–179 (2024).

Basso, A. & Serban, S. Industrial applications of immobilized enzymes-A review. Mol. Catal. 479, 35–54 (2019).

Sheldon, R. A. Green chemistry and biocatalysis: engineering a sustainable future. Catal. Today 431, 114571 (2024).

Hieber, G. & Ditrich, K. Introducing ChiPros™ -: biocatalytic production of chiral intermediates on a commercial scale. Chim. Oggi. 19, 16–20 (2001).

Breuer, M. et al. Industrial methods for the production of optically active intermediates. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. 43, 788–824 (2004).

Kovacs, B. et al. Racemization of secondary-amine-containing natural products using heterogeneous metal catalysts. ChemCatChem 10, 2893–2899 (2018).

Parvulescu, A., Janssens, J., Vanderleyden, J. & De Vos, D. Heterogeneous catalysts for racemization and dynamic kinetic resolution of amines and secondary alcohols. Top. Catal. 53, 931–941 (2010).

Geukens, I., Plessers, E., Seo, J. W. & De Vos, D. E. Nickel nanoparticles as racemization catalysts for primary amines. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 2623–2628 (2013).

Parvulescu, A. N., Jacobs, P. A. & De Vos, D. E. Heterogeneous Raney nickel and cobalt catalysts for racemization and dynamic kinetic resolution of amines. Adv. Synth. Catal. 350, 113–121 (2008).

Shakeri, M., Tai, C. W., Gothelid, E., Oscarsson, S. & Bäckvall, J. E. Small Pd nanoparticles supported in large pores of mesocellular foam: an excellent catalyst for racemization of amines. Chem. Eur. J. 17, 13269–13273 (2011).

Xu, G., Lan, S. Q., Fu, S. M., Wu, J. P. & Yang, L. R. Highly efficient dynamic kinetic resolution of benzylic amines with palladium catalysts on oxidized multiwalled carbon nanotubes for racemization. Tetrahedron Lett. 56, 2714–2719 (2015).

Xu, S. et al. Dynamic kinetic resolution of amines by using palladium nanoparticles confined inside the cages of amine-modified MIL-101 and lipase. J. Catal. 363, 9–17 (2018).

Ferreira, M. M. M. et al. Preparation, characterization and catalytic activity of palladium catalyst supported on MgCO3 for dynamic kinetic resolution of amines. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 29, 2144–2149 (2018).

Kim, Y., Park, J. & Kim, M. J. Fast racemization and dynamic kinetic resolution of primary benzyl amines. Tetrahedron Lett. 51, 5581–5584 (2010).

Apps, J. F. S. et al. Racemisation of 1-arylethylamines with Shvo-type organoruthenium catalysts. Synlett 25, 1391–1394 (2014).

Adriaensen, K. et al. Novel heterogeneous ruthenium racemization catalyst for dynamic kinetic resolution of chiral aliphatic amines. Green Chem 22, 85–93 (2020).

Jerphagnon, T. et al. Fast racemisation of chiral amines and alcohols by using cationic half-sandwich ruthena- and iridacycle catalysts. Chem. Eur. J. 15, 12780–12790 (2009).

Kwan, M. H. T. et al. Deactivation mechanisms of iodo-iridium catalysts in chiral amine racemization. Tetrahedron 80, 131823 (2021).

Blacker, A. J., Stirling, M. J. & Page, M. I. Catalytic racemisation of chiral amines and application in dynamic kinetic resolution. Org. Process Res. Dev. 11, 642–648 (2007).

Stirling, M. J., Mwansa, J. M., Sweeney, G., Blacker, A. J. & Page, M. I. The kinetics and mechanism of the organo-iridium catalysed racemisation of amines. Org. Biomol. Chem. 14, 7092–7098 (2016).

Koszelewski, D., Grischek, B., Glueck, S. M., Kroutil, W. & Faber, K. Enzymatic racemization of amines catalyzed by enantiocomplementary omega-transaminases. Chem. Eur. J. 17, 378–383 (2011).

Ruggieri, F., van Langen, L. M., Logan, D. T., Walse, B. & Berglund, P. Transaminase-catalyzed racemization with potential for dynamic kinetic resolutions. ChemCatChem 10, 5026–5032 (2018).

El Blidi, L. et al. Switching from (R)- to (S)-selective chemoenzymatic DKR of amines involving sulfanyl radical-mediated racemization. Org. Biomol. Chem. 8, 4165–4168 (2010).

Koszelewski, D., Clay, D., Rozzell, D. & Kroutil, W. Deracemisation of alpha-chiral primary amines by a one-pot, two-step cascade reaction catalysed by omega-transaminases. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 2289–2292 (2009).

Gastaldi, C., Gautier, A., Forano, C., Hélaine, V. & Guérard-Hélaine, C. Hybrid catalysis in concurrent mode: how to make catalysts and biocatalysts compatible? ChemCatChem 16, e202301703 (2024).

Hessefort, L. Z., Harstad, L. J., Merker, K. R., Ramos, L. P. T. & Biegasiewicz, K. F. Chemoenzymatic catalysis: cooperativity enables opportunity. ChemBioChem 24, e202300334 (2023).

González-Granda, S., Albarrán-Velo, J., Lavandera, I. & Gotor-Fernández, V. Expanding the synthetic toolbox through metal-enzyme cascade reactions. Chem. Rev. 123, 5297–5346 (2023).

Kracher, D. & Kourist, R. Recent developments in compartmentalization of chemoenzymatic cascade reactions. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 32, 100538 (2021).

Liu, Y. T. et al. Construction of chemoenzymatic cascade reactions for bridging chemocatalysis and Biocatalysis: principles, strategies and prospective. Chem. Eng. J. 420, 127659 (2021).

Carceller, J. M., Arias, K. S., Climent, M. J., Iborra, S. & Corma, A. One-pot chemo- and photo-enzymatic linear cascade processes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 53, 7875–7938 (2024).

Hao, R. et al. Bottom-up synthesis of multicompartmentalized microreactors for continuous flow catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 20319–20327 (2023).

Ferraz, C. A. et al. Synthesis and characterization of a magnetic hybrid catalyst containing lipase and palladium and its application on the dynamic kinetic resolution of amines. Mol. Catal. 493, 111106 (2020).

de Souza, S. P. et al. New biosilified Pd-lipase hybrid biocatalysts for dynamic resolution of amines. Tetrahedron Lett. 58, 4849–4854 (2017).

Verho, O. & Bäckvall, J. E. Chemoenzymatic dynamic kinetic resolution: a powerful tool for the preparation of enantiomerically pure alcohols and amines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 3996–4009 (2015).

de Miranda, A. S., de Souza, R. O. M. A. & Miranda, L. S. M. Ammonium formate as a green hydrogen source for clean semi-continuous enzymatic dynamic kinetic resolution of (+/−)-α-methylbenzylamine. RSC Adv. 4, 13620–13625 (2014).

Farkas, E. et al. Chemoenzymatic dynamic kinetic resolution of amines in fully continuous-flow mode. Org. Lett. 20, 8052–8056 (2018).

Takle, M. J. et al. A flash thermal racemization protocol for the chemoenzymatic dynamic kinetic resolution and stereoinversion of chiral amines. ACS Catal. 13, 10541–10546 (2023).

Takle, M. J. et al. Flash thermal racemization of chiral amine in continuous flow: an exploration of reaction space using DoE and transient flow. Org. Process Res. Dev. 29, 545–554 (2020).

Fox, J., Lowe, S. H., Petty, B. A. & Nemeth, E. F. NPS R-568: a type II calcimimetic compound that acts on parathyroid cell calcium receptor of rats to reduce plasma levels of parathyroid hormone and calcium. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 290, 473–479 (1999).

Han, K., Kim, Y., Park, J. & Kim, M.-J. Chemoenzymatic synthesis of the calcimimetics (+)-NPS R-568 via asymmetric reductive acylation of ketoxime intermediate. Tetrahedron Lett. 51, 3536–3537 (2010).

Tan, X. et al. Asymmetric synthesis of chiral primary amines by ruthenium-catalyzed direct reductive amination of alkyl aryl ketones with ammonium salts and molecular H2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 2024–2027 (2018).

Wu, S., Snajdrova, R., Moore, J. C., Baldenius, K. & Bornscheuer, U. T. Biocatalysis: enzymatic synthesis for industrial applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 88–119 (2021).

Bayer, T., Wu, S., Snajdrova, R., Baldenius, K. & Bornscheuer, U. T. An update: enzymatic synthesis for industrial applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202505976 (2025).

McElroy, C. R., Constantinou, A., Jones, L. C., Summerton, L. & Clark, J. H. Towards a holistic approach to metrics for the 21st century pharmaceutical industry. Green Chem 17, 3111–3121 (2015).

Thalén, L. K. & Bäckvall, J.-E. Development of dynamic kinetic resolution on large scale for (±)-1-phenylethylamine. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 6, 823–829 (2010).

Ma, G. et al. A novel synthesis of rasagiline via a chemoenzymatic dynamic kinetic resolution. Org. Process Res. Dev. 18, 1169–1174 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr Benjamin Deadman (BJ Deadman Consultancy) for advice on the DoE work. The work was funded by an EPSRC Prosperity Partnership grant: Innovative Continuous Manufacturing for Industrial Chemicals (“IConIC”, EP/X025292/1), with additional cash contributions from BASF SE.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The experiments were performed by M.J.T., supervised by K.K.M.H. and K.H., while the other authors (D.M.M., P.S., J.D., and C.H.) provided materials, advice, and direction during the project. The manuscript was written by M.J.T. and K.K.M.H., and all authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Takle, M.J., Maurer, D.M., Staehle, P. et al. Scalable and sustainable synthesis of chiral amines by biocatalysis. Commun Chem 8, 403 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01783-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01783-w