Abstract

Interstrand crosslinked nucleic acids offer diverse applications, including stabilizing DNA nanostructures in nanotechnology, enhancing miRNA inhibition in therapeutics, and studying enzyme activity in biochemistry. In this study, we present a new crosslinking design strategy that incorporates two 2′-deoxythioguanosine residues at noncomplementary yet strategically proximal positions within an oligo DNA duplex, promoting efficient disulfide crosslinking under chemical oxidation conditions. Additionally, this approach enables a photoinduced crosslinking reaction using 365 nm UV light, further facilitating the formation of disulfide crosslinked duplex. Our results demonstrate that the proximity of reactive thiocarbonyl groups of 2′-deoxythioguanosines incorporated within the duplex favors disulfide bond formation. Herein, we report the design strategy, crosslinking reaction results, and characterization of the crosslinked product. Furthermore, we introduce a new photoinduced disulfide crosslinking reaction and elucidate its mechanism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The high fidelity of molecular recognition displayed in Watson–Crick base pairing1 allows oligodeoxynucleotides (ODNs) to recognize their complementary targets in a sequence-selective manner, forming hybridized duplex structures that reversibly dissociate according to thermodynamic principles2,3. Beyond this intrinsic sequence specificity, chemical functionalization4,5 further broadens the utility of nucleic acids by enhancing their thermal stability and resistance to enzymatic processes such as unwinding by helicases6,7 and cleavage by nucleases8,9, thereby expanding their applications in nanotechnology, therapeutics, and biochemistry.

Rational chemical functionalization of ODNs with specific functional groups or reactive moieties enables hybridization-specific reactions10. By strategically incorporating these groups into modified ODNs, base pairing derived from the assembly of complementary sequences positions reactive sites in close proximity, facilitating and accelerating specific chemical reactions11. This approach has been used to create covalently bonded interstrand crosslinked nucleic acid structures, resulting in thermally stable duplexes. These crosslinked nucleic acids have applications in nanotechnology, where they enhance the stability of thermally labile DNA nanostructures12,13. They also show promise in therapeutics, particularly as anti-miRNA agents, by improving miRNA inhibition efficiency14,15. Additionally, they serve as valuable tools for studying enzyme activity and elucidating molecular mechanisms in biochemistry16. Furthermore, they provide deeper insights into biological processes that maintain genomic integrity, thereby aiding investigations into DNA repair mechanisms and cellular responses to DNA damage17,18.

Various strategies have been developed to achieve interstrand crosslinking within nucleic acids using chemically functionalized ODNs. The introduction of reactive moieties into single-stranded probes enables site-specific crosslinking with unmodified complementary targets through diverse chemical reactions. For example, photo-activated crosslinking reactions have been reported using psoralen19,20,21, carbazole22,23,24,25, diaziridine26,27, chloro-aldehyde28, coumarin-modified ODNs29,30, or photocaged nucleobases31, which can be light-activated to generate interstrand crosslinks with complementary DNA strands. Chemically activated groups, such as furan derivatives undergoing oxidation-based crosslinking32,33, have also been applied. Our group has previously developed vinyl-mediated Michael-type crosslinking reactions between a reactive base analog and its complementary natural nucleobase34,35,36,37. Other strategies involve modifying one strand to generate electrophilic intermediates that are subsequently attacked by nucleophilic sites on the complementary DNA strand38,39,40,41,42.

Alternatively, interstrand crosslinking can be achieved by incorporating reactive groups into each strand of the duplex. Upon hybridization, these groups are brought into close proximity, which allows them to undergo covalent bond formation through well-established chemical reactions such as amide bond formation43, imine formation44,45,46, click reactions47,48, and photocycloaddition49,50,51,52. Among these, disulfide bonds—formed by the oxidation of free thiols introduced at opposing positions on complementary ODN strands—enable the controlled and reversible assembly of thio-modified ODNs53. Their unique properties, which include relative stability under physiological conditions54,55,56, reversibility, and responsiveness to redox environments57,58,59, facilitate their application in nanotechnology60,61,62,63, cellular delivery64, and therapeutic development65. For example, DNA structures designed with complementary regions and thiol groups can form mechanically interlocked assemblies via disulfide bond formation66. Such mechanically interlocked DNA structures have significant potential in nanotechnology, particularly in constructing DNA-based supramolecular systems. In addition, the fully interlinked structure remains stable unless exposed to reducing conditions, such as the cytosolic environment within cells, where disulfide-linked structures are cleaved, enabling targeted cargo release in drug delivery applications67. Furthermore, the reversible nature of disulfide-linked strands can be utilized as a mechanistic probe for studying enzyme activity and molecular interactions within nucleic acid contexts68. Grasby et al. introduced reversible interstrand disulfide crosslinks by oxidizing non-Watson–Crick 4-thiouridine (4SU) and 6-thioguanosine (6SG) base pairs incorporated at complementary positions in a double-flap structure (Fig. 1a). This crosslinked structure, cleaved under reducing conditions, was used to validate the proposed mechanism of the FEN enzyme69.

Previous studies on interstrand crosslinking using thio-modified nucleobases typically involve artificial nucleobases incorporated at complementary positions. Kawai et al. designed a self-complementary DNA strand containing an unnatural nucleoside with a thiophenyl group (SPh) at the central complementary site within the ODN duplex (Fig. 1b)70. Under oxidizing conditions, this duplex formed disulfide crosslinks, which could be reversibly cleaved in reducing conditions. Kondo et al. utilized a self-complementary DNA duplex incorporating consecutive 6-thioguanosine–6-thioguanosine (6SG–6SG) mismatches (Fig. 1c)71. Unlike the thiophenyl-containing ODN duplex, these mismatches exhibited resistance to oxidation, requiring metal ions to promote disulfide bond formation. The incorporation of central mismatched thioguanine bases destabilized the duplex, as hydrogen bonding between two thioguanine bases is not expected. This disruption increased nucleobase fluctuations in the central region and disrupted base-stacking order72. However, metal ions coordinated with sulfur atoms, restoring base stacking and reducing fluctuations, thereby stabilizing the structure. Therefore, the spatial alignment and proper stacking of thioguanine residues within the duplex structure influence their reactivity. The proximity and conformational preferences of these reactive moieties are critical in determining the efficiency of disulfide bond formation.

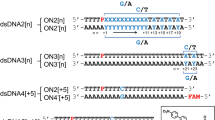

In this study, we present a new crosslink design strategy that incorporates two 2′-deoxythioguanosine residues at noncomplementary yet strategically proximal positions within an oligo DNA duplex (Fig. 2). The proposed design establishes an optimal spatial proximity that facilitates interstrand crosslinking, enabling the efficient and straightforward synthesis of disulfide-linked duplex under chemical oxidizing conditions. Notably, it also enables a light-triggered crosslinking reaction upon 365 nm ultraviolet (UV) irradiation, rapidly inducing disulfide bond formation and demonstrating the precise strategic positioning of reactive groups.

Results and discussion

Design and synthesis of oligo DNA duplex incorporating 2′-deoxythioguanosines

The interstrand crosslinking reaction was strategically designed using molecular modeling, which revealed that introducing 2′-deoxythioguanosine (TG) bases into each strand at positions offset by one nucleotide, rather than at complementary sites, positioned the sulfur atoms of opposing TG residues in close proximity (Fig. 2). The modeling further indicated that the formation of a disulfide bond between these closely positioned sulfur atoms would induce only minimal structural changes within the duplex. Based on these insights, we anticipated that a disulfide-crosslinked duplex with minimal conformational alterations could be obtained through a simple chemical modification. Accordingly, the phosphoramidite of 2′-deoxythioguanosine was synthesized following a previously reported procedure73 starting from commercially available 2′-deoxyguanosine (Scheme S1), then successfully incorporated into oligo DNA using standard solid-phase oligonucleotide synthesis method with an automated DNA synthesizer in DMT-ON mode (Scheme S2), yielding two 12-mer ODN sequences, ODN1 and ODN2 (Table S1) attached to a controlled-pore glass (CPG) solid support. The synthesized ODNs were treated with DBU to remove the 2-ethylhexylpropionate group while still being attached to the CPG resin. The ODNs were then cleaved from the CPG support using an alkaline NaSH solution (Scheme S2) to prevent air oxidation and sulfur loss, resulting in DMTr-protected ODNs. These CPG-cleaved ODNs were subsequently purified by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) (Figure S1a). The 5′-DMTr groups were then deprotected with 5% acetic acid, followed by a second RP-HPLC purification step to remove byproducts formed by air oxidation. (Figure S1b). Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) confirmed that the purified ODNs corresponded to the expected sequences. The synthesized oligo DNA strands were designed to form fully matched, complementary duplex incorporating 2′-deoxythioguanosine nucleotides at noncomplementary positions. The resulting duplex was then evaluated for its ability to form disulfide interstrand crosslinks.

Testing of disulfide crosslinking under chemical oxidation

As previously mentioned, the oxidation of thiocarbonyl groups in thio-modified nucleobases to form disulfide linkages within a duplex is known to be accelerated by oxidizing agents such as H2O2 or molecular iodine (I2)74. To assess the efficiency of disulfide crosslink formation, we first tested I2 as an oxidizing agent (Fig. 3a). A reaction mixture containing complementary ODN1 and ODN2 sequences (10 µM each) was incubated with I2 (100 µM) in phosphate buffer (20 mM, pH 7.0) containing NaCl (100 mM) at 10 °C for 1 h. Denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) analysis revealed the disappearance of single-stranded ODN bands and the emergence of a high-yield, low-mobility band, indicating efficient crosslinking (Fig. 3b). To evaluate the time dependence of the crosslinking reaction, the reaction was monitored over 1.0–60 min. The results showed that crosslink formation occurred rapidly, reaching high efficiency within 1.0 min of I2 incubation (Fig. S2a). The reaction was quenched upon the addition of dithiothreitol (DTT), a reducing agent, at a 2:1 molar ratio relative to I2, whereas an excess of the oxidizing agent enhanced the crosslinking efficiency (Fig. 3c).

a Schematic representation of the reversible disulfide interstrand crosslinking reaction in TG-containing DNA duplex. Crosslinking is induced under oxidative conditions (either chemically using I2 or via photoirradiation with 365 nm UV light) and reversed under reducing conditions using DTT. PAGE analysis of disulfide crosslinking via chemical oxidation. b ODN strands (10 µM each) were prepared in phosphate buffer (pH 7.0, 20 mM) containing NaCl (100 mM) and incubated with oxidizing agent, I2 (100 µM) at 10 °C for 1.0 h (−DTT condition). c ODN duplexes were treated with DTT at a 2:1 (200 µM DTT: 100 µM I2) or 1:2 ratio (+DTT condition). PAGE analysis of photoinduced crosslinking. d ODN strands (10 µM each) were prepared in phosphate buffer (pH 7.0, 20 mM) containing NaCl (100 mM) and photoirradiated with 365 nm LED light (UV light intensity: 3.0 W/m²) for 10 s and 30 s at 0 °C (−DTT condition). e Duplex photoirradiated for 30 s with DTT (200 µM) or incubated with DTT (200 µM) after 30 s of irradiation (365 nm LED light, intensity: 3.0 W/m²) (+DTT condition). PAGE analysis condition: 16% acrylamide, 20% formamide, and SYBRTM Gold staining.

In addition to the single stranded and hetero-crosslinked product bands, faint low-mobility bands were consistently observed by PAGE (Fig. 3). These bands disappeared upon DTT treatment (Fig. 3c), suggesting the presence of self-crosslinked species formed via disulfide bonds. Such self-crosslinking likely arises from a partial self-complementary base pairing that enables transient duplex formation, thereby facilitating intermolecular disulfide homo-crosslinking (Fig. S3a) through slow air oxidation over time. Denaturing PAGE analysis indicated that these self-crosslinked ODNs migrated more slowly than the fully complementary crosslinked duplex, likely due to highly mismatched crosslinked structures that hinder electrophoretic mobility. Notably, these self-crosslinks were readily reduced by DTT, whereas the presence of a complementary strand selectively promoted hetero-crosslinking with the aid of an excess oxidizing agent (Fig. 3c).

To better characterize the self-crosslinked species, HPLC was used to analyze each single-stranded ODN solution, which revealed two distinct peaks A and B (Fig. S3b). Peak B was identified as a self-crosslinked product, as DTT reduction yielded the corresponding single-stranded ODN in PAGE analysis (Fig. S3c), confirming the presence of reversible disulfide bonds. MALDI-TOF MS analysis of peak B predominantly showed reduced single-stranded ODNs due to the cleavage of disulfide bonds during laser desorption/ionization. However, low-intensity signals corresponding to intact self-crosslinked products were also detected (SI, MALDI-TOF MS).

The HPLC-purified hetero-crosslinked product was similarly analyzed by MALDI-TOF MS. As observed for the self-crosslinked species, the spectrum mainly showed peaks corresponding to the reduced single strands (ODN1 and ODN2) with a low-intensity peak corresponding to the intact crosslinked duplex ([M-H]− calcd for disulfide-crosslinked duplex: 7320.11, found: 7320.32).

The reversibility of the crosslinked adduct was further examined using the reducing agent glutathione (GSH). PAGE analysis revealed that the crosslinked product exhibited concentration-dependent reversibility, yielding two distinct bands corresponding to ODN1 and ODN2 (Fig. S4). These findings confirm the formation of the intended disulfide crosslinked product consisting of ODN1 and ODN2 strands.

Next, we quantified the yield of the disulfide crosslinking reaction. To ensure accurate measurement, pre-existing self-crosslinked ODNs were removed prior to the reaction because they reduced the availability of free thiol groups required for efficient crosslinking. HPLC analysis using ODN1 and ODN2 showed that the crosslinked product was obtained with a 95% yield (Fig. S5), indicating near-quantitative conversion of single-stranded ODNs to the disulfide-linked product.

Overall, our design enables rapid and nearly quantitative interstrand disulfide crosslinking of noncomplementary TG-incorporated residues, achieving a yield of 95% within 1 min under oxidizing conditions.

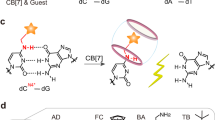

Testing crosslinking potential under photoirradiation

Unlike native DNA canonical bases, which absorb only UVC and UVB light, thio-modified nucleobases act as UVA-sensitive chromophores that absorb UV light at longer wavelengths. Sulfur substitution at the exocyclic oxygen atoms of the C6 position in purine bases significantly redshifts the lowest-energy absorption band. For instance, 2′-deoxyguanosine has a UV absorption maximum (λmax) of 251 nm, whereas its 6-sulfur-substituted derivative, 2′-deoxythioguanosine (6-TG), absorbs at a longer wavelength of 341 nm75. This shift allows the selective photoactivation of thio-nucleobases under UVA irradiation. Incorporating thio-modified nucleobases into DNA enhances photoreactivity under UVA light, leading to the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and various DNA lesions, including interstrand crosslinks. Notably, 6-TG incorporated into cellular DNA75,76,77,78 has been widely used in photocrosslinking studies involving canonical nucleic acid bases or proteins79. Meanwhile, synthetic ODNs incorporating 6-TG are known to form crosslinks with natural pyrimidine nucleobases via a [2 + 2] photocycloaddition reaction, which involves the thiocarbonyl group of 6-TG and the 5,6-double bond of thymine base on the opposite strand80,81. Given this well-established photoreactivity, we examined our oligo DNA duplex incorporating 6-TGs under UV irradiation to evaluate its potential for interstrand crosslink formation.

A duplex solution (10 µM of each ODN) in phosphate buffer (20 mM, pH 7.0) containing 100 mM NaCl was photoirradiated with 365 nm UV light at 0 °C for up to 30 s (Fig. 3a). PAGE analysis revealed efficient crosslinking, as indicated by the disappearance of single-stranded ODN bands and the appearance of a high-intensity, low-mobility band corresponding to the crosslinked product (Fig. 3d). To determine the type of crosslink formed, the duplex mixture was irradiated in the presence of DTT (200 µM) or incubated with DTT (200 µM) after photoirradiation. In both cases, the crosslink product band vanished (Fig. 3e), indicating the formation of a DTT-cleavable disulfide crosslink upon photoirradiation. A time-dependent analysis of the crosslinking reaction (Fig. S2b) showed that just 10 s of photoirradiation at a higher light intensity was sufficient to induce efficient crosslink formation. HPLC analysis showed that photoinduced crosslinking between ODN1 and ODN2 achieved a yield of 93% (Fig. S5), which indicates that this method efficiently converts single-stranded ODNs into disulfide-linked duplexes, similar to I2-induced crosslinking.

MALDI-TOF MS analysis of the HPLC-purified hetero-crosslinked product obtained after photoirradiation revealed peaks corresponding to the reduced single strands (ODN1 and ODN2), along with a low-intensity peak corresponding to the intact crosslinked duplex (SI, MALDI-TOF MS). To further confirm the structure of the photoinduced crosslink, nuclease digestion was performed on the crosslinked duplex, and the results were compared with those of the I2-mediated crosslink using the I2 reaction mixture as a positive control. HPLC analysis of the hydrolysates obtained from digested crosslinked duplexes (Fig. 4a) revealed a new peak with a longer retention time alongside peaks corresponding to natural nucleosides (Fig. 4b). Electrospray ionization–mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) analysis confirmed that this new peak matched the mass of disulfide-crosslinked guanosine nucleosides (ESI-HRMS (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for [C20H24N10O6S2]+: 565.1394, found: 565.1381), verifying the formation of a disulfide crosslink product under both conditions.

a Schematic representation of enzymatic digestion experiment for I2-mediated and photoinduced crosslinked products. The CL product (500 pmol) was incubated with a 10× nucleoside digestion mix reaction buffer and 1× nucleoside digestion mix at 37 °C for 3 h. b HPLC analysis followed by ESI-MS analysis of hydrolysates obtained from digested crosslinked duplexes, confirming the mass of disulfide-crosslinked guanosine nucleosides. The chromatograms show retention time (X-axis) from 0 to 25 min, and the peaks correspond to detector response (intensity, Y-axis) monitored at 254 nm, with an approximate signal range of 0–450,000 μV.

Furthermore, the crosslinked product was characterized for its thermal stability and conformational properties. Thermal stability was assessed by measuring the melting temperature (Tm) at 260 nm over a range of 0–90 °C. The crosslinked duplexes exhibited a significant increase in Tm (>80 °C) compared with the noncrosslinked duplex (46 °C) and native duplex (59 °C), indicating enhanced thermal stability due to the covalently linked strands (Figs. 5 and S6). These results confirm the successful formation of the crosslinked product.

a Comparison of the native duplex and the TG-containing duplex. b Thermal stability of the TG-containing duplex before and after the crosslinking reaction. Measurement conditions: Tm was determined by monitoring UV absorption at 260 nm from 0 to 90 °C at a heating rate of 1.0 °C/min. [ODN] = 2.0 μM, [NaCl] = 100 mM, in 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0).

To evaluate the conformational effects of incorporating TG residues into precrosslinked and crosslinked oligo DNA duplexes, circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy was performed. The CD spectra were recorded at 25 °C over a wavelength range of 210–350 nm. Overall, the CD spectra of noncrosslinked and crosslinked duplexes displayed typical B-DNA features, including a positive band around 280 nm due to base stacking and a negative band around 245 nm, characteristic of DNA helicity (Fig. S7), consistent with the right-handed helical structure of B-form DNA82,83. An increased intensity of the negative bands in the crosslinked duplexes was observed compared with that in the noncrosslinked duplex, likely due to helical conformational changes induced by covalent linkage formation. These results support the close proximity of the reactive thiocarbonyl groups of TG residues incorporated within our duplex, which facilitates disulfide crosslink formation under oxidative conditions without significantly distorting the B-DNA helix.

Evaluating the applicability of crosslinking design: sequence and orientation dependency

While the inherent reactivity of crosslinking moieties largely defines their potential for crosslink formation, their spatial positioning within the duplex plays an equally critical role in determining the reaction efficiency. Both the proximity and orientation (angular positioning) of reactive groups are crucial factors for interstrand crosslinking in chemically modified ODNs. Although hybridization templates bring reactive groups into close spatial proximity, ensuring they are within bonding distance11, proximity alone is insufficient. Efficient crosslinking also requires favorable orientation and proper angular alignment of the reactive moieties to achieve higher reaction rates, greater yields, and improved selectivity for the intended interstrand crosslinking over competing side reactions. Previous studies have shown that inadequate orientation can limit the crosslinking reaction efficiency45 and yield, or favor side reactions, even when reactive groups are positioned within bonding distance84,85,86. Furthermore, the placement of reactive motifs within the duplex, such as at the terminal or internal positions, and shifting reactive moieties toward the 5′- or 3′-end can influence crosslinking outcomes38,87,88,89. This is because variations in local flexibility, base stacking, and structural constraints affect how readily the reactive groups align and approach their counterparts on the opposite strand, thereby modulating crosslinking efficiency and selectivity. Therefore, designing an effective interstrand crosslinking system with high efficiency, yield, and selectivity requires consideration of both the distance and relative orientation of reactive residues as well as their positional context within the duplex.

To rigorously evaluate the proposed crosslinking strategy—in which TG residues are incorporated at noncomplementary positions—we first examined whether the crosslinking efficiency depends on the TG positions within the duplex when their orientation is maintained as in the original design. Duplexes maintaining the original TG orientation but differing in position were therefore designed (Fig. 6a). In the ODN1-2–ODN2-2 duplex, the TG in ODN1 was shifted three nucleotides toward the 3′ end, while the corresponding TG in ODN2 was shifted equivalently toward the 5′ end. This design positioned the TG residues near the duplex ends and adjacent to a guanine base, creating a local environment different from the original design. Shifting TGs toward the ends placed them in a region that may experience greater local flexibility than the centrally positioned original design. Additionally, this design enabled evaluation of the influence of electron transfer from adjacent bases, particularly guanine. Guanine is the most readily oxidized natural nucleobase and acts as a significant electron donor90. It is known to quench the excited state of nearby photoreactive groups through photoinduced electron transfer (PET)91,92, thereby dissipating energy and reducing the efficiency of the intended photochemical reaction. Therefore, this design allowed us to determine whether the position within the duplex and an adjacent guanine interferes with TG photoexcitation and crosslink formation when the overall orientation is maintained. ODN1-2–ODN2-2 efficiently and selectively produced disulfide-linked products under both chemical oxidation and photoirradiation conditions (Fig. 6b, c). The crosslinked products were fully cleaved with DTT, which confirms the disulfide linkage. Notably, the crosslinking efficiency was comparable to that of the original ODN1–ODN2 duplex, which indicates that maintaining the same orientation of the residues preserved both the reaction efficiency and resulting disulfide-linked product, while the sequence position and adjacency to guanine did not impede reactivity.

a Design of duplexes featuring TG residues at various positions and orientations relative to the original ODN1–ODN2 duplex. ODN1-2–ODN2-2 and ODN1-Term–ODN2-Term duplexes retained the same TG orientation as the original design, whereas, ODN3–ODN2 and ODN3-T–ODN2-A duplexes featured the opposite orientation. b–i PAGE analysis of disulfide crosslinking in TG-modified duplexes under chemical oxidation and photoirradiation conditions. b, c ODN1-2–ODN2-2 duplex and d, e ODN1-Term–ODN2-Term duplex form selective disulfide crosslinks under chemical oxidation and photoirradiation which are fully cleavable by DTT. f, g ODN3–ODN2 duplex and h, i ODN3-T–ODN2-A duplex yield mainly DTT-resistant products under chemical oxidation and show no photoinduced crosslinking activity. Chemical oxidation conditions: ODN strands (10 µM each) in phosphate buffer (pH 7.0, 20 mM) containing NaCl (100 mM) and DTT (100 µM) were treated with I2 (200 µM) at 10 °C for 1.0 h. The formed crosslinked (CL) product was incubated with DTT (200 µM) at 10 °C for 30 min. Photoirradiation conditions: ODN strands (10 µM each) in phosphate buffer (pH 7.0, 20 mM) containing NaCl (100 mM) were irradiated with 365 nm LED light (UV light intensity: 3.0 W/m2) for 30 s at 0 °C. The formed CL product was incubated with DTT (200 µM) at 10 °C for 30 min. PAGE analysis condition: 16% acrylamide, 20% formamide, and SYBRTM Gold staining.

Next, we examined whether crosslinking outcomes are affected by the position of TG residues within the duplex: mid-duplex versus terminal. Mid-duplex modifications place reactive residues in a rigid structure stabilized by base stacking, which helps align the reactive groups precisely and promotes selective disulfide formation. In contrast, terminal residues are more flexible, prone to end fraying93, and more exposed to the solvent, which can destabilize alignment or increase susceptibility to side reactions. To test this, we designed the ODN1-Term–ODN2-Term duplex (Fig. 6a), where TG residues were incorporated at the terminal positions while maintaining the same orientation as in the original design. This duplex formed disulfide crosslinks selectively under both chemical oxidation and photoirradiation (Fig. 6d, e) with only minor formation of DTT-resistant side products under photoirradiation (Fig. 6e). These findings show that, although placing residues at the terminal introduces additional flexibility and potential side reactions, effective and selective disulfide crosslinking is still achievable when the orientation is maintained.

Having established that crosslinking efficiency is not constrained by position, we next aimed to determine if this strategy is limited to a specific alignment or can function across different orientations, which would demonstrate broader potential applicability. Subsequently, we tested the impact of reversing the orientation of the reactive groups by designing a duplex featuring an opposite alignment of the reactive TG residues (ODN3–ODN2, Fig. 6a). In this design, the TG position in ODN3 was shifted from the 5th position in ODN1 to the 7th position in the 5′ → 3′ direction, thereby placing the TG residues in an opposite orientation relative to the original ODN1–ODN2 duplex. The ODN3–ODN2 duplex was tested under the same optimized chemical oxidation and photoirradiation conditions as ODN1–ODN2, and the crosslinked products were analyzed by DTT treatment to distinguish disulfide crosslinks from reduction-resistant side products. Unlike the original ODN1–ODN2 duplex, which selectively formed disulfide crosslinks, the crosslinked products of the ODN3–ODN2 duplex were mostly resistant to cleavage by DTT under chemical oxidation (Fig. 6f). Only partial cleavage was observed, indicating that the main products were non-disulfide (DTT-resistant) crosslinks most likely formed through competing reactions, with only minor disulfide formation. Moreover, no crosslinking activity was observed under photoirradiation (Fig. 6g). Given that the ODN3 sequence places a guanine base next to the TG residue, we investigated whether this could account for the lack of photoinduced crosslinking when the orientation was opposite to the original design. To test this, we designed an additional duplex (ODN3-T–ODN2-A, Fig. 6a) with an extra spacer base intended to disrupt possible electronic interactions. However, ODN3-T–ODN2-A exhibited crosslinking behavior similar to that of ODN3–ODN2, mainly forming DTT-resistant products under chemical oxidation along with minor disulfide crosslinking (Fig. 6h) and showed no crosslinking activity upon photoirradiation (Fig. 6i). This suggests that the presence of adjacent guanine is not the main factor suppressing photoreactivity. Instead, the relative orientation of the reactive groups appears to be the key factor influencing the efficiency and selectivity of disulfide crosslink formation.

Overall, these results demonstrate that the efficiency and selectivity of disulfide crosslinking in TG-modified duplexes are strongly orientation-dependent and are governed primarily by the relative orientation of the reactive residues, while not being restricted by the sequence position. Duplexes with opposite alignments yielded predominantly DTT-resistant products and lacked photoinduced crosslinking, whereas maintaining the original orientation enabled efficient and selective disulfide formation both at internal and terminal sites. Thus, while flexibility in residue positioning and terminal placement can be tolerated, the strategy remains dependent on maintaining a favorable orientation of TG residues to achieve efficient and selective interstrand crosslinking.

To elucidate the origin of the distinct reactivity observed between the two orientations in disulfide crosslinking, molecular modeling was conducted to evaluate the distance and angular parameters of the disulfide-forming TG residues. The interatomic distance between the sulfur atoms of closely positioned TG residues was calculated to be 4.27 Å in the ODN1–ODN2 duplex (original design) (Fig. S8a) and 4.86 Å in the ODN3–ODN2 duplex (opposite orientation) (Fig. S8b). Although the sulfur atoms in the original design were in closer proximity, this difference (Δ = 0.59 Å) alone is insufficient to explain the contrasting reactivity outcomes. Instead, structural analysis revealed pronounced differences in the conformational changes and angular alignment associated with crosslink formation. The bond angles were measured between the C6–S bonds of each TG and the two sulfur atoms (C6–S···S) in the pre-crosslinking state, and between the C6–S–S bonds in the post-crosslinking state. (Figure S8). In the original design, the angles decreased modestly from 110.6° and 111.6° to 104.9° and 105.4° (Fig. 7a), corresponding to angular adjustments (i.e., change required to achieve the crosslinked geometry) of Δ = −5.7° and −6.2°, respectively. Thus, the initial geometry (average 111.1°) was already close to the final crosslinked angle (average 105.2°). This minor reorientation (average 6.0°) indicates that the duplex was pre-organized for the crosslinking reaction, requiring only a minor conformational adjustment to reach the transition state, thereby lowering the activation energy for bond formation. Consequently, this design efficiently produced disulfide crosslinks under chemical oxidation and photoirradiation conditions.

a ODN1–ODN2 duplex (original orientation) showing near-optimal pre-organization, with minor angular adjustment. b ODN3–ODN2 duplex (opposite orientation) showing poor pre-organization, requiring large angular reorientation prior to crosslinking. The CPK models indicate TG bases. The molecular modeling and energy minimization were performed by using MacroModel (Schrödinger). OPLS4 and water were used as the force field and solvent, respectively.

In contrast, the opposite-direction design displayed notable angular changes from 93.3° and 87.9° to 106.5° and 106.8°, respectively, after crosslinking (Fig. 7b). These correspond to significant increases of Δ = +13.2° and +18.9°, respectively. The initial geometry (average 90.6°) was far from the final disulfide-linked angle (average 106.7°), which indicates that the duplex is poorly pre-organized for the crosslinking reaction. Consequently, a major conformational adjustment and substantial reorientation (average 16.1°) were required prior to bond formation, which resulted in a higher transition energy barrier that was unfavorable for direct disulfide formation. As a result, the reaction was diverted toward unexpected reaction pathways where the slower formation of S–S bonds allowed competing reactions to take place, resulting mainly in DTT-resistant crosslinked products. Under chemical oxidation conditions, disulfide-linked species were formed only as minor products, and no disulfide crosslink formation was observed upon photoirradiation.

Taken together, these results indicate that the near-optimal pre-organization in the original design facilitated efficient and selective disulfide crosslinking, whereas the poor pre-organization in the opposite design required a substantial conformational reorientation that raised the activation barrier and led to inefficient disulfide crosslink formation. Thus, the efficiency and selectivity of disulfide crosslinking in TG-modified DNA duplexes are governed primarily by the relative orientation of the reactive residues rather than their exact sequence position. Therefore, this strategy offers a broad scope with respect to sequence context and residue positioning provided that the favorable orientation of TG residues is maintained.

Elucidating photoinduced crosslinking reaction mechanism

Thio-modified nucleobases exhibit high intersystem crossing (ISC) rate constants (transition from the singlet state to the triplet state) upon UVA exposure, with the triplet state displaying high photoreactivity94 (Scheme 1 and Eq. 1) due to thiolation that stabilizes sulfur electronic excitation, enabling thiobases to act as photosensitizers, generate ROSs, and enhance photoreactivity toward various photochemical reactions. An important consideration is that 6-TG exhibits context-dependent photochemical reactivity upon UVA irradiation, with the resulting products varying significantly depending on its molecular environment—whether as a monomer or incorporated into synthetic ODNs. Several studies95,96,97,98 have demonstrated that singlet oxygen (1O2) is the primary ROS generated upon UVA irradiation of 6-TG. This occurs via a type II photosensitization pathway, where energy transfer from triplet 6-TG (3TG) to ground-state oxygen (3O2) produces 1O2 (Eq. 2). However, 3TG may also lose energy via electron transfer to 3O2, generating superoxide radicals (O2•−), a process favored in the presence of an electron donor (D) (Eq. 3)99,100. This reaction forms TG•− and D•+, with O2•− expected to arise via electron transfer from TG•− to 3O2, regenerating the ground-state TG (⁰TG).

Eq. (1) Upon UVA irradiation, ground-state thioguanosine (0TG) is excited to the singlet state (1TG), which undergoes an intersystem crossing (ISC) to the excited triplet state (3TG). Two possible pathways of 3TG to generate ROS in the presence of 3O2, Eq. (2) 3TG can transfer energy to 3O2, generating 1O2 via a type II reaction. Eq. (3) Alternatively, electron transfer from 3TG to 3O2 can produce O2•− in a type I reaction, a process that is favored in the presence of electron donors.

While the type II photosensitization pathway and its products are well-reported, there are remarkably few studies on type I photosensitization—where electron transfer generates O2•−. Despite the well-known and diverse photochemical reactivity of 6-TG, no previous study, to our knowledge, has clearly demonstrated photoinduced disulfide bond formation between two 6-TG nucleobases incorporated within an oligo DNA duplex. Accordingly, we aimed to elucidate the mechanism underlying disulfide crosslink formation under photoirradiation and to determine whether type I or type II photosensitization predominates in this photochemical reaction system.

To explore our reaction system, we proposed a speculative mechanism (Fig. 8) in which UV irradiation of the oligo DNA duplex incorporating 6-TGs induces charge separation via a single electron transfer (SET) process. Upon photoexcitation, TG on one strand transitions to its triplet excited state (3TG), making it more redox-active than its ground state and allowing it to act as an electron acceptor101,102. Meanwhile, 0TG on the opposite complementary strand serves as an electron donor. The strong reducing nature of the sulfur atom in 6-TG facilitates this process103, resulting in the formation of a radical anion (TG•−) at the acceptor site and a radical cation (TG•+) at the donor site. Although charge recombination, which regenerates neutral 0TGs, is possible, this process is suppressed under air-saturated conditions due to the abundance of 3O2. Instead, TG•− acts as a type I photosensitizer, transferring an electron to 3O2 to produce O2•− and regenerate 0TG. Simultaneously, TG•+ undergoes deprotonation to form a neutral thiyl radical (TG•), which then reacts with 0TG via homolytic cleavage of the thiocarbonyl double bond, leading to the formation of a disulfide-crosslinked adduct. This process generates a carbon-centered radical that delocalizes on the purine ring of the 6-TG base. Incorporation of oxygen, derived from either O2•− or 3O2 generates a peroxyl anion (–OO−) or peroxyl radical (–OO•), which eventually loses a proton, yielding a stable disulfide-crosslinked structure within the DNA duplex.

Based on this hypothesis, we identified four key elements underlying the proposed mechanism. First, 3O2 plays a critical role in the electron transfer step, driving the reaction toward the formation of the crosslinked product. Second, the electron transfer step results in the formation of O2•− as ROS via a type I photosensitization pathway. Third, the reaction is initiated by SET and subsequent charge separation, facilitated by the close proximity of reactive thioguanosines within the duplex structure. Finally, a thiyl radical intermediate is generated, enabling the crosslinking reaction.

To evaluate the plausibility of the proposed mechanism, we first examined the effect of 3O2 on the reaction efficiency by performing the reaction under an argon atmosphere (Figs. 9a and S9). Using a sealed reaction tube flushed with argon, the samples were irradiated with 365 nm light. PAGE analysis (Fig. 9b) revealed a significant reduction in reaction efficiency under these conditions, as evidenced by a notable decrease in the band intensity of the crosslinked product compared with that observed under air-saturated conditions. These findings highlight the crucial role of 3O2 in driving the photoinduced disulfide crosslinking reaction and enhancing its efficiency. The abundance of 3O2 suppresses charge recombination, thereby promoting crosslink formation, whereas low 3O2 levels allow the recombination of charged radical species, regenerating neutral 0TGs and ultimately reducing the overall reaction efficiency.

a Schematic illustration of crosslinking reaction under argon (Ar) atmosphere to evaluate the influence of O2. b PAGE analysis for reaction efficiency under Ar atmosphere versus air-saturated conditions. ODN strands (10 µM each) were prepared in phosphate buffer (20 mM, pH 7.0) containing NaCl (100 mM); photoreaction was then performed using 365 nm LED light (UV light intensity: 3.0 W/m²) for 30 s at 0 °C in an open tube (air-saturated) or in a sealed tube flushed with Ar for 3 or 5 min, followed by irradiation under Ar flow. PAGE analysis condition: 16% acrylamide, 20% formamide, SYBRTM Gold staining, and ChemiDoc MP imaging system. Quantitative analysis of the crosslinked product (% band intensity) showed a marked decrease in reaction efficiency under Ar conditions compared to air-saturated conditions. The crosslinking yield was calculated from the intensity of the crosslinked product band over the sum of the product and remaining single-stranded ODNs.

As a further attempt, we sought to identify the predominant ROS involved in the photosensitization process by using various scavengers and assessing their impact on the photochemical reaction (Fig. S10a). Photoirradiation experiments were conducted in the presence of mannitol (a hydroxyl radical •OH quencher)73,74, superoxide dismutase (SOD, an O2•− scavenger)75,76, and sodium azide (a 1O2 quencher)77, at varying concentrations, with reaction outcomes analyzed via PAGE. However, even at high scavenger concentrations, no significant modulation in reaction efficiency was observed (Fig. S10b, S10c, S10d). The quenching of these species did not noticeably affect reaction yield, suggesting that none play a direct role in driving crosslink formation. This finding supports our proposed mechanism, in which O2•− is a byproduct of electron transfer to 3O2 rather than a direct contributor to the crosslinking reaction.

As an alternative approach, we attempted to detect photogenerated O2•− in the reaction system using nitro blue tetrazolium chloride (NBT) as a detection probe. NBT, a yellow, water-soluble compound, specifically reacts with O2•− to form formazan, a purple, water-insoluble product with a characteristic absorption in the wavelength range of 500–600 nm, detectable via UV–Vis spectroscopy (Fig. 10a)104,105. To investigate O2•− production, the oligo DNA duplex was irradiated with 365 nm UV light in the presence of NBT. Since 10 s of irradiation was sufficient for efficient crosslinking, we performed O2•− detection at 10 s and 1.0 min for comparison. The formation of formazan, indicating O2•− generation, was monitored via UV–Vis spectroscopy. As a negative control, a buffer solution containing only NBT, without oligo DNA, was irradiated under identical conditions. The UV–Vis spectra showed no absorption in the wavelength range of 500–600 nm (Fig. 10b), confirming the absence of formazan formation. In contrast, the duplex irradiated for 10 s exhibited a strong absorption band in this range (Fig. 10c), confirming O2•− generation.

a–e: Detection of the photogenerated O2●− using nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT). a Schematic of O2•− detection using NBT as a detection probe to form the UV-detectable formazan compound. UV–Vis spectra showing the absorption intensity at approximately 500–600 nm (corresponding to formazan) for different samples: b negative control (buffer solution containing NBT without ODN), c duplex solution, d single-stranded ODN, and e crosslinked product solution (10 s preirradiated duplex). All samples were photoirradiated in the presence of NBT. Conditions: single-stranded ODN, duplex, or CL product (40 µM, 4.0 µL) was irradiated with NBT (600 µM) in 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0, containing 100 mM NaCl) at 0 °C using a 365 nm UV LED (UV light intensity: 34.1 W/m²) for 10 s or 1 min. Formazan formation was analyzed by UV–Vis (400–800 nm) spectroscopy after dilution with DMSO. f, g: SET kinetics in duplex vs. Single-stranded oligo-DNA systems. f In-duplex SET: The duplex structure facilitates faster O2•− generation by promoting efficient SET kinetics through a proximity effect, which aligns the donor (0TG) and acceptor (³TG) in a favorable geometry. g Interstrand SET: The single-stranded system exhibits inefficient SET kinetics, leading to slower electron transfer and undetectable O2•− levels under short photoirradiation time.

Interestingly, when a single-stranded oligo DNA was irradiated for 10 s, no corresponding formazan absorption was observed (Fig. 10d), suggesting that O2•− was not produced under these conditions. However, after 1.0 min of irradiation, a weak absorption band appeared, indicating delayed O2•− generation compared with the duplex (Fig. 10d). These findings suggest that the duplex structure facilitates O2•− production by enabling faster electron transfer kinetics than the single-stranded oligo DNA. The rigid duplex conformation, along with the proximity effect provided by the hybridized structure, aligns the electron donor (0TG) and acceptor (3TG) in a favorable geometry for rapid SET (Fig. 10f). Consequently, under short irradiation (10 s), charge separation generates TG•− and TG•+ species, followed by electron transfer to 3O2, enabling O2•− detection. In contrast, the single-stranded ODN lacks these structural constraints (Fig. 10g), reducing the likelihood of favorable alignment between the reactive components and making the SET step less efficient. Consequently, the reaction exhibits slower kinetics, requiring longer irradiation times for detectable O2•− generation. This was confirmed by irradiating the single strand for 1 h, which led to more pronounced O2•− production in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. S11).

We have confirmed that crosslinking terminates O2•− generation. This was demonstrated by irradiating a solution containing the crosslinked product in the presence of NBT, where no absorption band was observed in the 500–600 nm range (Fig. 10e), indicating the absence of detectable O2•−. Collectively, these results underscore the critical role of the DNA duplex structure in facilitating rapid electron transfer and efficient O2•− generation. In the duplex system, O2•− is generated swiftly through electron transfer to 3O2. However, once crosslinking occurs and no free TG is available for further electron transfer, O2•− generation is suppressed, aligning with our proposed reaction mechanism.

Our mechanism suggests that the neutral thiyl radical (TG•) forms as an intermediate during the crosslinking reaction through the oxidation and proton loss of TG•+. Based on this hypothesis, we anticipated that chemical reduction could restore oxidized TG• back to 0TG, thereby propagating O2•− generation (Fig. 11a). This hypothesis is supported by a previous study100, which reported that monitoring 6-TG monomer/UVA-induced photosensitization in the presence of GSH induces O2•− oxidation–GSH reduction cycles, with the thiyl radical as an intermediate. To test this hypothesis, we irradiated a TG-containing single strand in the presence of GSH as a reducing agent and monitored O2•− generation using the NBT assay. The solution containing GSH exhibited a significantly higher absorption intensity corresponding to the formazan compound compared to the solution without GSH (Figs. 11b and S12a), indicating enhanced O2•− generation. This increase was further confirmed visually, as the GSH-containing solution displayed a more intense purple color (Figs. 11c and S12b), indicative of greater formazan formation. These results strongly support the formation of the thiyl radical as a key intermediate in the photosensitization process. Reduction of TG• by GSH sustains photoinduced O2•− generation (Path A, Fig. 11a). However, after prolonged photo-irradiation, when GSH is fully oxidized to GSSG, the thiyl radical is expected to rapidly react with 3O2 (Path B, Fig. 11a)100, leading to the formation of various oxidation products95,96,97.

a Scheme showing O2•− generation and formation of thiyl radicals in TG-containing single strand. Path A (+GSH): reduces TG• back to 0TG, promoting continuous generation of photoinduced O2•−. Path B (−GSH): in the absence of GSH, TG• undergoes oxidation, leading to the gradual loss of O2•− generation over time. b NBT assay results: UV–Vis absorption spectra showing the absorption band intensity corresponding to the formazan compound in TG-containing single-strand oligo DNA irradiated with and without GSH. c Visual observation result showing more intense purple color, indicative of formazan formation, in the solution with GSH compared to the solution without GSH. Conditions: Single-stranded ODN (60 µM, 4.0 µL) was irradiated with 600 µM NBT in 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0, 100 mM NaCl) with or without 300 µM GSH at 0 °C using a 365 nm UV LED (UV light intensity: 3.0 W/m²) for 1 h. Formazan formation was analyzed by UV-Vis (400–800 nm) after dilution with DMSO.

Our proposed mechanism is further supported by the likely formation of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) as a secondary byproduct. This H2O2 could originate from species generated during the photoinduced reaction, either through protonation of the hydroperoxide anion (HOO−) or recombination of a hydroperoxyl radical (HOO•) with O2•−. To confirm its presence, we used the OxiVision™ Green sensor, an H2O2-selective fluorescent probe. A strong fluorescence response was observed when the probe was incubated with a 10 s photoirradiated duplex solution compared to the nonirradiated control (Fig. S13), confirming H2O2 generation upon photoirradiation.

Taken together, these findings provide strong mechanistic support for our proposed reaction pathway. The initiation of the reaction via charge separation and SET is evidenced by the accelerated O2•− generation in the duplex system. Moreover, we confirmed that 3O2 plays a crucial role in facilitating the electron transfer step, resulting in O2•− generation, which is efficiently detected in our system as an electron transfer product rather than as a direct driving force of the reaction. Additionally, our results indicate that the reaction proceeds via a thiyl radical intermediate, which enables interstrand crosslinking.

Impact of TGs orientation on photoinduced crosslinking efficiency

Having elucidated the underlying photoinduced crosslinking reaction mechanism, we next sought to rationalize the lack of reactivity observed in the opposite orientation upon photoirradiation (Fig. 6g, i). To this end, we compared the efficiency of O2•− generation in the ODN2–ODN3 duplex (opposite orientation) using the NBT method with that in the ODN1–ODN2 duplex (original design) as a positive control. While the original design generated O2•− efficiently within 10 s of irradiation (Fig. 10c), no detectable O2•− was observed for the opposite orientation under the same conditions (Fig. 12a). Detectable levels appeared only after 1.0 min of irradiation, indicating that the opposite orientation exhibited a notable delay in O2•− generation. These results are consistent with the lack of crosslinking reactivity in the opposite orientation.

a O2•− generation in the ODN2–ODN3 duplex (opposite orientation) measured by the NBT assay under photoirradiation. Conditions: duplex (40 µM, 4.0 µL) was irradiated with NBT (600 µM) in 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0, containing 100 mM NaCl) at 0 °C using a 365 nm UV LED (UV light intensity: 34.1 W/m2) for 10 s or 1 min. Formazan formation was analyzed by UV–Vis (400–800 nm) spectroscopy after dilution with DMSO. b Schematic illustrating how the opposite orientation of TG residues accelerates charge recombination, shortens the lifetime of TG●−, and reduces electron transfer efficiency to O2.

As noted earlier, structural analysis of the two duplex designs using molecular modeling revealed key differences in the orientation and angular alignment of the TG residues. When viewed from the same angle, a striking difference in their relative positioning was apparent. In the original design (ODN1–ODN2 duplex), the TG residues were oriented away from each other rather than directly stacked on top, resulting in larger spatial separation. This observation is consistent with the longer interatomic distances (N1–N1 = 4.76 Å, C2–C2 = 5.76 Å), which suggests reduced overlap of the reactive groups (Fig. S14a, S14b). In contrast, the opposite orientation (ODN3–ODN2 duplex) caused the TG residues to be more directly stacked, leading to a closer spatial approach. This is consistent with the shorter interatomic distances (N1–N1 = 3.80 Å, C2–C2 = 3.69 Å), which reflect partial overlapping of the residues (Fig. S14a, S14b).

These structural differences align well with the experimental results of O2•− generation and can be rationalized within the proposed reaction mechanism. In the original design, the TG residues point in directions that maintain sufficient spatial separation for charge-separated species to persist long enough for TG•− to transfer an electron to O2, efficiently producing O2•−. In contrast, the opposite orientation (ODN3–ODN2 duplex) has partial overlapping between TG residues, which facilitates rapid charge recombination (Fig. 12b) that shortens the lifetime of TG•−. This limits its ability to transfer an electron to O2 and thereby results in slower O2•− generation.

Collectively, by taking all structural analyses into account, these findings demonstrate that the orientation and degree of overlap of TG residues within a DNA duplex dictate photoinduced crosslinking. In the original design, the pre-organized duplex structure minimizes the angular adjustments required for crosslinking, while the smaller overlap between TG residues enables effective electron transfer to O2, leading to efficient O2•− generation and disulfide crosslinking. In the opposite orientation, the poorly pre-organized duplex structure requires major conformational adjustments, and the closely stacked TG residues accelerate charge recombination, which slows electron transfer to O2 and delays O2•− formation. This ultimately reduces the photoinduced reactivity toward crosslinking.

Repetitive reversibility of crosslinking reaction

We next examined the ability of our oligo DNA duplex design to undergo multiple cycles of crosslink formation and cleavage under controlled conditions without significant loss of functionality or structural integrity. This property is essential for applications requiring reversible crosslinking for dynamic control, such as stimuli-responsive materials59, drug delivery systems66,106, and biochemical studies107,108. Maintaining the crosslinking performance over multiple cycles would enable repeated switching between the crosslinked and non-crosslinked states, making the system suitable for such applications. To assess this, we tested the reversibility under chemical oxidation using I2 and reduction using DTT (Fig. 13a). PAGE analysis confirmed that excess I2 efficiently induced crosslink formation, whereas excess DTT cleaved the disulfide bonds (Fig. 13b). This cycle was repeated effectively for three iterations, demonstrating consistent disulfide bond formation and cleavage without loss of efficiency.

a, b Chemical oxidation (I2) and reduction with DTT. Conditions: ODN strands (10 µM each), phosphate buffer pH 7.0 (20 mM), NaCl (100 mM), DTT (100 µM), I2 (200 µM), incubated at 10 °C (lane 4), then maintaining DTT:I2 ratios of 2:1 for cleavage and 1:2 for crosslinking (lanes 5–8). c, d Photo-oxidation in the presence of Py–SS–Py followed by DTT reduction. Conditions: ODN strands (10 µM each), phosphate buffer pH 7.0 (20 mM), NaCl (100 mM), Py–SS–Py (100 µM), DTT (100 µM), 365 nm LED light (UV light intensity: 3.0 W/m²) for 10 min at 0 °C.

We also tested the reversibility of crosslinking under photo-oxidation and DTT reduction conditions (Fig. 13c). DTT temporarily inhibits crosslink generation by cleaving disulfide bonds; however, prolonged photoirradiation depletes DTT, enabling high-yield crosslink formation. The minimum DTT concentration required for effective cleavage of the photoinduced crosslink product was 100 µM (Fig. S15a). Adding 2,2′-dipyridyl disulfide (Py–SS–Py) as a disulfide trapping reagent enabled the sequestration of DTT, permitting crosslinking to resume under extended photoirradiation (up to 10 min) (Fig. S15b). Over time, thiol-disulfide exchange mediated by Py–SS–Py oxidized DTT, reducing its cleavage efficiency and allowing high-yield crosslinking. Under these conditions, photoinduced crosslinking remained effective for up to three cycles (Fig. 13d). After the second crosslinking step, a negligible yield of a side crosslink product was observed; however, the intended disulfide crosslink remained the dominant product throughout the cycles. To evaluate the biological relevance of this system, we examined the stability of disulfide-crosslinked duplexes in cell lysates. The disulfide crosslinks were rapidly cleaved within 1 min upon incubation in the lysate (Fig. S16), demonstrating that this system responds efficiently to intracellular reducing environments under physiologically relevant conditions. This reversible property could enable applications in structural dynamics studies as well as in targeted release within biochemical systems66,109.

To expand this crosslinking strategy beyond simple DNA duplexes, we examined its applicability to structurally diverse nucleic acid systems. A 72-mer linear DNA strand was designed with TG residues incorporated into the complementary regions near the 5′ and 3′ ends, along with two poly(T)14 flexible spacers to facilitate strand folding (Fig. S17a). This design brings the TG residues near the 5′ and 3′ ends into proximity, enabling intramolecular disulfide bond formation under oxidative conditions and resulting in a disulfide-crosslinked stem-loop structure (Fig. S17a). Both chemical oxidation and photoirradiation conditions efficiently promoted crosslinking, and subsequent treatment with reducing agents restored the linear form (Fig. S17b, S17c). Reversibility was confirmed through repeated redox cycling: sequential I2-mediated oxidation and DTT reduction allowed multiple cycles of bond formation and cleavage (Fig. S17b), whereas photoirradiation–DTT cycles showed reduced efficiency after the first cycle, likely due to partial hydrolysis of TG residues (Fig. S17c). This reversible redox-responsive switching offers promising applications because disulfide cleavage can be precisely triggered by the intracellular environment to restore the linear construct and enable controlled intracellular release. Importantly, these results demonstrate that disulfide-based crosslinking can be applied beyond simple duplexes to more structurally complex nucleic acid architectures.

Conclusions

Herein, we successfully demonstrated that incorporating noncomplementary 2′-deoxythioguanines within an oligo DNA duplex enables efficient interstrand disulfide crosslinking through proximity-driven reactions under various oxidation conditions, without significantly distorting the B-DNA helix. This design facilitated rapid crosslinking within 1 min under chemical oxidation, achieving a nearly quantitative yield (95%), and introduced a novel photoinduced reaction that afforded disulfide crosslink formation within 10 s of 365 nm UV irradiation with 93% yield. Formation of the intended disulfide-crosslinked product was confirmed through multiple experiments, including its susceptibility to cleavage under reducing conditions and enzymatic digestion, which identified disulfide-crosslinked guanosine nucleosides as the exclusive product, indicating a clean reaction profile. The crosslinked duplexes exhibited significantly enhanced thermal stability (Tm > 80 °C) compared with the noncrosslinked duplex (47 °C), confirming successful covalent strand linkage formation.

The designed proximity and precise positioning of the reactive thiocarbonyl groups in the 2′-deoxythioguanosine-incorporated duplex structure were critical for achieving efficient disulfide crosslinking. Additionally, it was demonstrated that the orientation of TG residues within a DNA duplex dictates both the efficiency and selectivity of crosslink formation. In the ODN1–ODN2 design, the TG in ODN1 was positioned in a 5′-offset manner relative to the TG in ODN2, which yielded a pre-organized duplex structure that required only minor conformational changes and small angular adjustments, thereby minimizing the activation energy for efficient crosslinking. In the ODN2–ODN3 design, the TG in ODN3 was positioned in a 3′-offset manner relative to the TG in ODN2, which produced a poorly pre-organized duplex that required major conformational adjustments and increased the activation energy. This, in turn, slowed the disulfide crosslinking reaction and promoted competing reactions under chemical oxidation. The structure of the resulting DTT-resistant product and the mechanistic details of its formation are currently being elucidated.

Mechanistic investigations of photoinduced disulfide crosslink formation revealed that (1) the reaction is initiated by SET followed by charge separation, where photoexcited 3TG acts as an electron acceptor, accepting an electron from 0TG to generate TG•− and TG•+ radicals; (2) molecular oxygen (3O2) plays a crucial role in the electron transfer step, driving the reaction toward disulfide bond formation; (3) O2•− is produced as a byproduct of electron transfer to 3O2; and (4) TG• is a key intermediate in the process.

We further confirmed that O2•− is generated upon photoirradiation with distinct kinetics: duplex system exhibits faster O2•− generation, but once the disulfide crosslink forms and 6-TG is depleted, further SET and electron transfer to 3O2 are suppressed. In single-stranded 6-TG system, O2•− generation occurs more slowly and is dependent on 6-TG concentration and irradiation time. Over time, O2•− generation diminishes as TG• rapidly reacts with 3O2, forming various oxidation products. However, GSH-mediated reduction of TG• regenerates 6-TG, sustaining further O2•− production.

Additionally, we demonstrated that our duplex design permits reversible crosslinking, allowing multiple cycles of crosslink formation and cleavage under oxidation–reduction conditions. Furthermore, this redox-responsive switching between crosslinked and noncrosslinked states can be extended to more structurally complex nucleic acid constructs. Such reversible redox responsiveness holds promise for developing dynamic DNA-based systems for nanotechnology, drug delivery, and biotechnological applications.

The design principles established here, together with the insights from molecular modeling and mechanistic elucidation of the reaction mechanism, provide a valuable foundation for the rational design of nucleic acid crosslinking strategies. Beyond the validation of proximity-driven crosslinking and photoinduced reactivity, these findings highlight the potential of thioguanine-mediated chemistry as a versatile platform for dynamic and reversible covalent modifications of nucleic acids. Such advances are expected to broaden the scope of nucleic acid chemistry and facilitate future applications of chemically and photoinduced crosslinking.

Methods

Synthesis of 2′-deoxythioguanosine phosphoramidite and its incorporation into oligo DNA

First, 2′-deoxyguanosine was protected with tert-butyldimethylsilyl (TBDMS) groups to yield compound 1. Compound 1 was then reacted with 2-mesitylenesulfonyl chloride to activate the 6-position of guanine, forming a sulfonate ester intermediate. This intermediate was subsequently treated with 2-ethylhexyl 3-mercaptopropionate in the presence of N-methylpyrrolidine to yield compound 2. Next, the 2-amino group of compound 2 was protected with phenoxyacetyl chloride to yield compound 3. The TBDMS groups were then removed using tetrabutylammonium fluoride (TBAF), resulting in the corresponding diol product, compound 4. The 5′-hydroxyl group of compound 4 was selectively protected with 4,4-dimethoxytrityl (DMTr) chloride in pyridine to form compound 5. The phosphoramidite derivative of compound 5 was synthesized using 2-cyanoethyl-N,N-diisopropylchlorophosphoramidite, affording compound 6 (Scheme S1). Compound 6 was successfully incorporated into oligo DNA through a standard solid-phase synthesis approach using an automated DNA synthesizer (Scheme S2) and purified by HPLC to yield the intended ODN sequences (see SI).

MALDI–TOF MS measurement

Lyophilized ODN samples obtained after HPLC purification were dissolved in H2O for MALDI–TOF MS analysis. The matrix was prepared by mixing di-ammonium hydrogen citrate (5 mg/50 µL, in H2O) with 3-hydroxypicolinic acid (25 mg/500 µL, in 1:1 H2O/CH3CN, v/v). A 1 µL aliquot of the matrix solution was first spotted onto the MALDI sample plate, followed by 1 µL of the ODN sample solution. After drying at room temperature, the samples were analyzed by MALDI–TOF mass spectrometry.

Disulfide crosslinking under iodine reaction conditions (PAGE analysis)

A duplex formed from the complementary sequences ODN1 and ODN2 (10 µM each) was incubated with iodine (100 µM, prepared in DMSO) in a phosphate buffer solution (20 mM, pH 7.0) containing NaCl (100 mM) at 10 °C. The total reaction volume was 4.0 µL. The reaction mixture was quenched by adding a loading buffer containing 10 mM EDTA in 80% formamide and analyzed using denaturing 16% polyacrylamide, 20% formamide gel electrophoresis. The gel image was visualized using SYBR™ Gold stain.

Preparative disulfide crosslink under iodine reaction conditions (large scale)

A large-scale crosslinking reaction under iodine conditions was performed as described above, with the oligo DNA amount increased to 500 pmol. The reaction solution was then desalted using Sep-Pak® C18 Plus short cartridge (WatersTM) and purified using an illustra™ NAP™-5 column (Cytiva). The collected fraction containing the crosslinked product was dried by lyophilization.

Photoinduced disulfide crosslinking reaction (PAGE analysis)

Complementary strands (10 µM each) were prepared in phosphate buffer (20 mM, pH 7.0) containing 100 mM NaCl and irradiated at 0 °C using a 365 nm LED light source. The total volume of the irradiated solution was 4.0 µL. The reaction mixture was quenched by adding a loading buffer containing 10 mM EDTA in 80% formamide and analyzed using denaturing 16% polyacrylamide and 20% formamide gel electrophoresis. The gel image was visualized using SYBR™ Gold stain.

Preparative disulfide crosslinking under photoirradiation conditions (large scale)

The photoreaction was performed as described above using a total oligo concentration of 10 µM in a 4.0 µL reaction volume and repeated 12 times to achieve a total oligo amount of 500 pmol. The photoirradiated reaction solutions were combined, desalted using Sep-Pak® C18 Plus short cartridge (WatersTM), and lyophilized.

Characterization of self-crosslinked products

Self-crosslinked products were isolated by HPLC under the following conditions: NACALAI TESQUE, COSMOSIL, 5C18-MS-II packed column (10 ID × 250 mm), gradient system: (A) 0.1 M TEAA buffer, (B) 5%–30% acetonitrile over 20 min followed by a linear gradient to 100% over 20–30 min, column temperature: 35 °C, flow rate of 1 mL/min, and detection using a UV detector at 254 nm. HPLC-purified self-crosslinked products were analyzed by PAGE after DTT treatment. ODNs (10 µM) in phosphate buffer (20 mM, pH 7.0) containing NaCl (100 mM) were incubated with DTT (200 µM) at 10 °C for 30 min, and samples were subsequently analyzed by denaturing PAGE (16% acrylamide, 20% formamide) and visualized by SYBR™ Gold staining.

HPLC quantification of crosslinking yield

Crosslinking reactions were performed on a 500 pmol scale by using ODN1 and ODN2 under the conditions described above. Reaction yields were quantified by HPLC with single-stranded ODNs and duplex standards used as references for peak assignment and normalization. The crosslinking yield was calculated as the percentage of the normalized product peak area relative to the sum of all normalized peak areas, where each HPLC peak area was divided by the corresponding molar extinction coefficient at 260 nm (ε = 260 nm). HPLC Conditions: NACALAI TESQUE, COSMOSIL, 5C18-MS-II packed column (10 ID × 250 mm), gradient system was conducted at a column temperature of 45 °C, flow rate of 1 mL/min, and detection using a UV detector at 254 nm: (A) 0.1 M TEAA buffer and (B) acetonitrile at 5%–30% over 20 min followed by a linear gradient to 100% over 20–30 min.

Enzymatic digestion experiment of crosslinked products and HPLC analysis

To the lyophilized reaction mixture containing 500 pmol of crosslinked products, 17.0 μL of distilled, sterilized H2O was added, followed by 2.0 μL of 10X nucleoside digestion mix reaction buffer and 1.0 μL of nucleoside digestion mix (New England Biolabs). The reaction mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 3 h. Samples were analyzed by HPLC under the following conditions: COSMOSIL 5C18-AR-II Packed Column (4.6 × 250 mm), gradient system with (A) 50 mM NH4COOH and (B) acetonitrile, 0%–40% (B) over 20 min, followed by a linear gradient to 100% (B) over 20–30 min, column temperature of 35 °C and flow rate of 1 mL/min. The chromatograms show retention time (X-axis) from 0–25 min, and the peaks correspond to detector response (intensity, Y-axis) monitored at 254 nm, with an approximate signal range of 0–450,000 μV. A new peak with a longer retention time appeared in the HPLC profile. The corresponding fractions were separated, lyophilized, and analyzed by ESI-MS. The observed mass spectrum data were as follows: ESI-HRMS (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for disulfide crosslinked guanosine adduct [C20H24N10O6S2]+: 565.1394, found: 565.1381.

Melting temperature (T m) measurements

For melting temperature (Tm) measurements, a 100 μL solution of duplex (2.0 μM) in phosphate buffer (20 mM, pH 7.0) containing NaCl (100 mM) was transferred to a micro quartz cell with a 1-cm path length. The melting temperature was measured by UV absorption at 260 nm from 0 °C to 90 °C at a rate of 1.0 °C/min. Each sample was measured three times, and the results were averaged to obtain the final value. The melting temperature was measured using a V-730 (JASCO Corporation) spectrophotometer equipped with a temperature controller.

CD spectrum measurements

A 100 μL solution of duplex (4.0 μM) in phosphate buffer (20 mM, pH 7.0) containing NaCl (100 mM) was transferred to a microquartz cell with a 1-cm path length. The CD spectra were analyzed at 25 °C over a wavelength range of 210–350 nm using a J-720WI (JASCO Corporation) spectropolarimeter equipped with a temperature controller.

Disulfide crosslinking in TG-modified duplexes: sequence and orientation dependency

Chemical oxidation conditions: Complementary ODN strands (10 µM each) were prepared in phosphate buffer (20 mM, pH 7.0) containing NaCl (100 mM) were incubated with DTT (100 µM) at 10 °C for 30 min to reduce self-crosslinked species. Crosslinking was then induced by treatment with I2 (200 µM) at 10 °C for 1 h. The resulting crosslinked products were subsequently incubated with DTT (200 µM) at 10 °C for 30 min prior to analysis.

Photoinduced crosslinking conditions: Duplexes (10 µM) were prepared in phosphate buffer (20 mM, pH 7.0) containing NaCl (100 mM) and irradiated with 365 nm LED light (UV intensity: 3.0 W/m2) for 30 s at 0 °C. The resulting crosslinked products were then incubated with DTT (200 µM) at 10 °C for 30 min prior to analysis.

PAGE analysis: Samples were analyzed by denaturing PAGE (16% acrylamide, 20% formamide) and visualized with SYBR™ Gold staining.

Testing photoinduced crosslinking under argon (Ar) atmosphere

The photoreaction solution was prepared as described above, and the experiment was conducted by sealing the reaction tube with a plastic septum and parafilm and then flushing it with argon gas through a syringe to remove air. The sealed reaction tube was irradiated with 365-nm light under an argon flow. The reaction mixture was then quenched by adding a loading buffer (containing 10 mM EDTA in 80% formamide) and analyzed by denaturing 16% polyacrylamide and 20% formamide gel electrophoresis. SYBRTM Gold staining was used to visualize the gel image.

Detection of photogenerated superoxide radicals using the NBT method

For the detection of photogenerated superoxide radicals using the NBT method, solutions (4.0 μL) of single-stranded ODN, duplex, or a solution containing the CL product (10-s preirradiated duplex) at 40 µM were irradiated with 600 µM NBT in a 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing 100 mM NaCl at 0 °C using a 365 nm UV LED light source (UV light intensity: 34.1 W/m²) for 10 s and 1.0 min. After photoirradiation, the solutions were diluted with DMSO to dissolve the formed formazan compound and analyzed using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer over a wavelength range of 400–800 nm.

Testing the effect of GSH on the propagation of superoxide radical generation using NBT method

To test the effect of GSH on the propagation of superoxide radical generation using the NBT method, solutions (4.0 μL) of single-stranded ODN (60 µM) were irradiated with 600 µM NBT in 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing 100 mM NaCl and 300 µM GSH at 0 °C using a 365 nm UV LED light source (UV light intensity 2.96 W/m²) for 1.0 h. After photoirradiation, the solutions were diluted with DMSO to dissolve the formed formazan compound and analyzed using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer over a wavelength range of 400–800 nm. The same experiment was performed without including GSH in the photoreaction mixture.

Detection of hydrogen peroxide generation in the photoreaction mixture

A solution (4.0 μL) of duplex (40 µM) in a 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing 100 mM NaCl was irradiated at 0 °C using a 365 nm UV LED light source for 10 s (UV light intensity: 34.1 W/m²), then incubated with 10 µM OxiVision Green™ hydrogen peroxide sensor at room temperature for 45.0 min. Fluorescence emission spectra were recorded using a fluorescence spectrometer (λex = 490 nm) at 25 °C. The same experiment was performed using a duplex solution without photoirradiation and a photoirradiated blank solution in the absence of duplex.

Repetitive reversibility of crosslinking reaction

Chemical oxidation (I2) and reduction (DTT): For I2-mediated oxidation and DTT reduction, a 100 µM I2 crosslinking reaction solution was prepared as previously described and incubated with 200 µM DTT at 10 °C. The crosslinked product was then recovered by adding 200 µM I2 to the same solution and incubating at 10 °C. This cycle of crosslink formation and cleavage was repeated thrice, maintaining a DTT:I2 concentration ratio of 2:1 for cleavage and 1:2 for crosslinking. After each step, the reaction solutions were analyzed by denaturing 16% polyacrylamide, 20% formamide gel electrophoresis, and the gel image was visualized using SYBR™ Gold stain.

Photo-oxidation and DTT reduction: For the photo-oxidation and DTT reduction experiments, a solution of the photoinduced crosslink product was incubated with 100 µM DTT, followed by the addition of 100 µM 2,2′-dipyridyl disulfide (Py–SS–Py). The solution was then photoirradiated using a 365 nm UV LED for 10.0 min at 0 °C (UV light intensity 3.0 W/m²). This process was repeated three times, and all reaction solutions were analyzed using denaturing 16% polyacrylamide, 20% formamide gel electrophoresis, with visualization using SYBR™ Gold stain.

Stability of the crosslinked products in cell lysate

Reaction mixtures containing HPLC-purified I2-induced and photoinduced crosslinked products (2.5 µM) in phosphate buffer (20 mM, pH 7.0) were incubated with HeLa whole-cell lysate (0.125 µg/µL; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) at 37 °C for 1 and 10 min. The sample mixtures were subsequently analyzed by denaturing PAGE (16% acrylamide, 20% formamide) and visualized using SYBR™ Gold staining.

Intramolecular disulfide crosslinking to form a disulfide-crosslinked stem-loop structure

Chemical oxidation (I2) and reduction (DTT): a 72-mer ODN strand (0.5 µM) was prepared in phosphate buffer (20 mM, pH 7.0) containing NaCl (100 mM) and DTT (50 µM). Crosslinking was induced by treatment with I2 (100 µM), and the reaction was incubated at 10 °C for 30 min. Redox cycling was performed three times, maintaining a DTT:I2 concentration ratio of 2:1 for cleavage and 1:2 for crosslinking.

Photoirradiation and DTT reduction: a 72-mer ODN strand (0.5 µM) was prepared in phosphate buffer (20 mM, pH 7.0) containing NaCl (100 mM) and irradiated with 365 nm LED light (UV intensity: 34.1 W/m2) for 30 s at 0 °C. The resulting photoinduced crosslinked product was incubated with 100 µM DTT, followed by the addition of 100 µM Py–SS–Py. The solution was then irradiated again using a 365 nm UV LED for 30 s at 0 °C (UV light intensity 3.0 W/m2).

Reaction mixtures were analyzed by denaturing PAGE (16% acrylamide, 20% formamide) and visualized using SYBR™ Gold staining.

Data availability

The raw data that support the findings of this study are available in the Figshare repository at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30737996.

References

Sessler, J. L., Lawrence, C. M. & Jayawickramarajah, J. Molecular recognition via base-pairing. Chem. Soc. Rev. 36, 314–325 (2007).

Craig, M. E., Crothers, D. M. & Doty, P. Relaxation kinetics of dimer formation by self complementary oligonucleotides. J. Mol. Biol. 62, 383–401 (1971).

Sugimoto, N. et al. Thermodynamic parameters to predict stability of RNA/DNA hybrid duplexes. Biochemistry 34, 11211–11216 (1995).

Sharma, V. K., Sharma, R. K. & Singh, S. K. Antisense oligonucleotides: modifications and clinical trials. Med. Chem. Commun. 5, 1454–1471 (2014).

Smith, C. I. E. & Zain, R. Therapeutic oligonucleotides: state of the art. Annu. Rev. Pharm. Toxicol. 59, 605–630 (2019).

Wu, Y. Unwinding and rewinding: double faces of helicase? J. Nucleic Acids 2012, 140601 (2012).