Abstract

Implementing on-chip non-volatile optical memories has long been an actively pursued goal, promising significant enhancements in the capability and energy efficiency of photonic integrated circuits. Here, we demonstrate an non-volatile optical memory exclusively using the most common semiconductor material, silicon. By manipulating the photon avalanche effect, we introduce a trapping effect at the silicon-silicon oxide interface, which in turn demonstrates a non-volatile reprogrammable optical memory cell with a record-high 4-bit encoding, robust retention and endurance. This silicon avalanche-induced trapping memory provides a distinctively cost-efficient and high-reliability route to realize optical data storage in standard silicon foundry processes. We demonstrate its applications in trimming in optical interconnects and in-memory computing. Our in-memory computing test case reduces energy consumption by approximately 83% compared to conventional optical approaches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

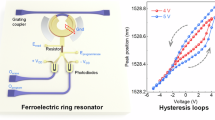

Data storage has become a crucial requirement in modern photonic systems, encompassing applications like optical interconnects, optical computing, and photonic quantum circuits. Photonic data storage can significantly improve the performance of existing photonic systems by eliminating the latency associated with electronic memories, reducing the need for optoelectronic conversion, and minimizing static energy consumption. In optical computing, for instance, optical memories can eliminate the von-Neumann bottleneck by reducing the traffic between the optical processor and electrical memory1, and facilitate system architectures such as spiking neural networks2 and in-memory optical computing3. However, achieving the storage of light poses a significant challenge due to the inherently weak interaction of photons. In response, many efforts have been made over the past decades to develop optical memories. Similar to electronic memories, optical memories are broadly classified into two main categories: volatile and non-volatile memories4. Volatile optical memories, that lose the stored data when the power is off, can be implemented through bistable optical devices5,6, optical ion excitation7, and recirculating loop arrangements8. Non-volatile optical memories, on the other hand, can maintain the stored data without power. They can be achieved by altering the material properties interacting with light, including phase-change memories (PCMs)9,10,11,12, ferroelectric memories13,14,15, micro-electro-mechanical systems (MEMS)16,17,18, floating-gate memories19,20,21,22,23, and optical memristors24,25,26,27. PCMs are characterized by thermal energy-dependent properties, transitioning between amorphous and crystalline states. This reversible transformation leads to significant changes in optical properties, affecting both the real and imaginary components of the complex refractive index. The representative PCM material is germanium-antimony-tellurium alloy (GST), which requires additional sputtering on photonic integrated circuits (PICs)11. Ferroelectric memories can toggle between two polarization states, which also require additional integration of ferroelectric materials, such as lead zirconium titanate (PZT), barium titanate (BTO), polyvinylidene flouride (PVDF), and hafnium oxide (HfO2), on the Si chip. MEMS devices employ various mechanisms, such as electrostatic, electrothermal, electromagnetic, and piezoelectric methods. Electrostatic actuation, in particular, allows low-power MEMS on a pure silicon (Si) platform. Extensive efforts have been dedicated to integrating MEMS into the standard Si photonics process, progressing from multi-layer MEMS to single-layer MEMS. However, the movable parts of MEMS still necessitate several additional processes for release17,18. Additionally, the switching voltage of MEMS tends to be very high. Optical floating-gate memories, akin to their electrical counterparts, involve a thin oxide dielectric layer and a floating gate, which are compatible with complementary-metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) technology. The application of a bias voltage to the floating gate induces a high electric field, facilitating carrier injection into the oxide layer. Consequently, the reflective index of the device undergoes changes owing to the plasma dispersion effect. The current Si photonics foundries also require additional doping and Si/III-V bonding processes for optical floating-gate memories. Optical memristors are also CMOS-compatible, which can be integrated on Si PICs through heterogeneous integration25. But similar to floating-gate memories, an extra memristor layer is needed in the devices, such as HfO2, zinc oxide (ZnO), titanium dioxide (TiO2), tungsten oxide (WOx), and tantalum pentoxide (Ta2O5)28. Besides that, the yield and reliability of memristors still face certain challenges29.

Unlike the aforementioned technologies of non-volatile optical memories, here we demonstrate an optical avalanche-induced trapping memory (ATM) exclusively utilizing the most common semiconductor material, Si. The wavelength shift is driven by the plasma dispersion effect, which is the predominant tuning mechanism in Si and is widely employed in Si photonics due to the absence of alternative mechanisms like the Pockels effect. Consequently, the Si optical memory is built on the standard Si photonics process, eliminating the need for additional materials, layers, or processes in the current Si photonics foundries. In the microelectronic community, bias temperature instability (BTI) has become a serious problem today as the size of metal-oxide-semiconductor field effect transistors (MOSFETs) shrinks. When the gate of a heated MOSFET is heavily biased, a strong electric field through the oxide layer results in the degradation of the MOSFET threshold voltage. Over the past decade, experimental evidence has confirmed that charge trapping is the cause of BTI30,31,32. While BTI poses a significant challenge in microelectronics, the associated charge trapping may hold promise for non-volatile memories. Here, we employ charge trapping at the Si-silicon oxide (SiO2) interface using the photon avalanche effect to achieve Si optical memories. Different from MOSFETs, there is no gate or vertical electric field on the oxide layer. Instead, traps at the Si-SiO2 interface are charged by unbalanced free carries originating from avalanche-multiplying photocurrent to avoid extremely high electric fields and the resulting instability. This mechanism allows for a hysteresis effect on the Si-SiO2 interface, imparting non-volatile switching characteristics to the optical memory device. The program and erase states of the optical memory are implemented through a standard Si P-N junction, ensuring full compatibility with existing Si photonics devices. Consequently, the Si ATMs offer a groundbreaking approach to achieving photonic data storage. Leveraging the existing fabrication process, it presents a simple, cost-efficient, and high-yield pathway to integrate optical memories into Si PICs, directly applicable in areas such as optical interconnects, optical computing, and photonic quantum circuits.

Results

Device structure

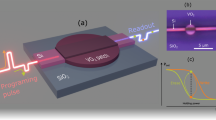

The schematic diagram of the non-volatile Si optical ATM is presented in Fig. 1a, the device is fabricated on a (100) orientation, 220 nm-thick Si-on-insulator (SOI) wafer. The optical memory incorporates an all-pass microring resonator (MRR) structure, with the MRR waveguide doped to form a Si P-N junction. The waveguide core region is doped with P-type and N-type dopants to create a depletion interface inside the core region. A standard SiO2 layer covers the entire Si all-pass MRR. The imperfect transition between crystalline Si and amorphous SiO2 leads to some unbonded Si atoms, creating unpaired electrons that localize on the defect Si atoms and forming dangling bond traps. The configuration of Si-SiO2 interface is depicted in Fig. 1b, with potential traps including: 1) \({E}^{{\prime} }\) oxide trapping center, O3 ≡ Si•, which comprises of an unpaired electron localized on a Si atom while back-bonded three oxygen atoms; 2) Pb0 interface center, Si3 ≡ Si•, which involves an unpaired electron and back-bonded three Si atoms; and 3) Pb1 interface center, Si2O ≡ Si•, characterized by an unpaired electron and back-bonded two Si atoms and one oxygen atom. \({E}^{{\prime} }\) traps have levels near the middle of the SiO2 bandgap, facilitating hole capture from the Si layer, thereby exhibiting donor-like traps33. Pb0 and Pb1 trap centers only show donor-like states within the Si bandgap allowing for hole capture34. These donor-like traps are electrically neutral when empty and positively charged when occupied by holes. The occupation of the traps varies according to the stress conditions applied to the device. The charged traps in the Si-SiO2 interface establish a localized electrical field that repels dopant charges of the same polarity in the Si waveguide away from the interface. This space charge distribution relocates the doping profile of the Si P-N junction, thereby changing the effective refractive index of the waveguide through the Si plasma dispersion effect. As a result, by occupying/emptying the interface traps, the Si MRR waveguide exhibits different refractive indices and thus distinct resonant wavelengths in its optical spectrum. It is worth noting that the trap occupation ratio changes under specific stress conditions, therefore, once this device is programmed/erased, it will exhibit a multi-level non-volatile wavelength shift.

a Schematic diagram of the Si ATM based on microring structure (inset: microscope image of the device), and the program and erase process within the memory waveguide. b Configuration of the Si-SiO2 interface and associated traps, with Si atoms shown in orange, oxygen atoms in blue, and traps in purple. c Measured resonant wavelength switches of the Si optical ATM at 25 °C (green), 50 °C (orange), and 75 °C (purple). d Measured optical spectrum of the Si ATM in the erase (green) and program (purple) states at 75 °C. e Measured dark current of the Si ATM at 25 °C (green), 50 °C (orange), and 75 °C (purple), along with expanded current curves in the avalanche region (program region) and the forward region (erase region).

Program and erase characteristics

The program and erase conditions of the Si ATM are depicted in Fig.1a. For programming, the Si P-N junction is reverse-biased close to its avalanche breakdown voltage while an O-band laser is fed into the MRR to generate a considerable photocurrent Iph of ~ 100 μA. This notable Iph arises from the combination of photon-assisted tunneling, resonant enhancement, and avalanche gain35. Under this condition, the Si-SiO2 interface traps will gradually capture holes. The positively charged traps redistribute the doping profile of the waveguide, and the device exhibits the program state. The photocurrent is crucial during the program progress; otherwise, the resonant wavelength shift relying solely on high reverse bias voltage would be very small. This is because, to generate more free holes for trap capture, both photoillumination and impact ionization are required. Impact ionization itself, i.e., high reverse bias stress, cannot offer enough extra holes to significantly change the trap occupancy. In contrast, only electrical stress is required during the erase progress. The Si P-N junction is forward biased to generate a forward current Ifw of around hundreds μA. The large Ifw can discharge the traps, therefore, reset the optical memory to the erase state. The detailed analysis is described in the Mechanisms and simulations section.

The switch in resonant wavelength of the optical memory are presented in Fig. 1c, from bottom to top, measured at 25 °C, 50 °C, and 75 °C, respectively. All data points are recorded with electrical power off, with even scan indices taken after erasing and odd scan indices after programming. The program state demonstrates a red-shifted resonant wavelength compared to the erase state across all three temperatures. Specifically, the resonant wavelength shift Δλ is ~ 17 pm at 25 °C, ~ 20 pm at 50 °C, and ~ 42 pm at 75 °C. The difference between two states Δλ increases with temperature. This indicates that hole trapping is a temperature-dependent process. One possible explanation is that hole trapping is a non-radiative multi-phonon process (NMP)31, wherein the traps are required to be thermally excited before they can capture holes followed by structural relaxation, see Supplementary Note 1. Given that devices under 75 °C show the most significant memory shift, the subsequent results were measured at 75 °C unless otherwise specified. The corresponding transmission spectrum within three cycles of the optical memory at 75 °C is shown in Fig. 1d. The three erase state curves and the three program state curves overlap well, respectively, indicating the optical memory device has stable and reproducible states. The red-shifted Δλ of ~ 42 pm results in an extinction ratio (ER) of ~ 18 dB.

In addition to the non-volatile change in the optical domain, the device also exhibits a shift in the electrical domain. Figure 1e shows the measured dark current versus bias voltage ranging from +1 V to -8 V, where the solid lines are the erase state and the dash lines represent the program state. First of all, the device in the program state has a higher dark current at reverse bias at all temperatures, possibly due to the charged traps leading to a higher surface leakage current. Besides that, a voltage shift phenomenon is observed in both the avalanche region and forward region. In the enlarged plot of the avalanche region, it is evident that the breakdown voltage of the programmed optical memory is approximately 25 mV higher than that of the device in the erase state. The charged traps repel dopants of the same polarity, causing an expansion of the depletion layer and, consequently, an increase in breakdown voltage. Conversely, the optical memory in the erase state exhibits a ~ 50 mV higher forward bias voltage for the same current value compared to that in the program state. This voltage shift is attributed to the variation in the built-in voltage Vbi of the Si P-N junction, which is expressed as

where kB is the Boltzmann constant, T is the temperature, q is the elementary charge, NA is the acceptor concentration, ND is the donor concentration, and ni is the intrinsic carrier concentration. The charged traps in the program state repel the NA doping concentration, leading to a decrease in the Vbi. Consequently, the optical memory is an optoelectronic device that displays nonvolatile memory effect in both optical and electrical domains.

Memory performance

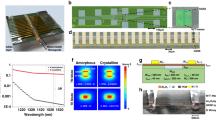

The Si P-N junction-based optical memory can be optoelectronically programmed and electronically erased, showcasing clear and repeatable switching capabilities. To quantify the performance of the Si ATM, we conducted additional measurements. Figure 2a illustrates the optical spectrum of the Si MRR, recorded at 60-second intervals during programming. The spectrum gradually red-shifts as the program time increases, indicating that this optical memory exhibits multiple states depending on the duration of programming. At the resonant wavelength of the erase state (approximately 1313.52 nm, as marked by the black dashed line in Fig. 2a), the optical power levels of these multiple states are plotted in Fig. 2b. These states were averaged over five measurements, with standard deviation error bars shown. The optical power transmission increases almost linearly with program time, supporting 26 distinct states, with optical power ranging from approximately 0.0 to 0.16. The average standard deviation (σ) across these 26 optical power states is about 0.004. These multiple states arise from varying levels of trap occupation, as the process of traps capturing holes follows a rate equation, making the number of charged traps a function of program time. Figure 2c shows the corresponding resonant wavelengths from Fig. 2a versus program time. As expected, the resonant wavelengths increase with program time similar to an exponential function 1 − e−t. The red-shifted resonant wavelength indicates an increased refractive index of the waveguide. According to the well-known plasma dispersion effect of Si, changes in doping that result in an increase in refractive index also lead to a reduction in free carrier absorption loss. The corresponding Q factors are depicted in Fig. 2d, aligning with the anticipated increasing trend versus program time. The fluctuation of the Q factors is attributed to uncertainties arising from the Lorentzian fitting of the optical spectrum.

a Measured optical spectrum of the Si ATM during programming, recorded every 60 s, progressing from left to right over time. b Multiple optical power states versus program time of the Si ATM at the wavelength of ~ 1313.52 nm, as indicated by the black dash line in Fig. a. The error bars for different states were measured based on five trials. c Corresponding resonant wavelengths versus program time. d Corresponding quality factors (Q) of the microring Si optical memory from Lorentzian shape fitting. e Retention measurements of non-volatile resonant wavelengths of the program (purple) and erase (green) states within a 24-hour period. f Endurance measurements of the Si optical ATM with 100 cycles of program and erase.

One critical parameter for non-volatile memory is its retention capability. The resonant wavelengths of the optical ATM were monitored every 10 minutes over a 24-hour period in both the program and erase states. As illustrated in Fig. 2e, both program and erase states demonstrate stable resonant wavelengths. The program state has an average resonant wavelength of ~ 1313.56 nm with a standard error of ~ 1.49 pm, and the erase state has an average resonant wavelength of ~ 1313.52 nm with a standard error of ~ 1.24 pm. Given the lack of any observable decay in either state, the device is expected to remain stable well beyond the 24-hour measurement period. The remarkable stability over one day highlights the retention capability of the Si optical memory. Cyclability is another important figure of merit for memory performance. To evaluate this, the optical ATM was subjected to a cycling test by alternately programming and erasing. The program operation is reverse biased near the breakdown voltage with a photocurrent Iph of ~ 100 μA for 2500 s, while the erase operation is forward biased with hundreds μA current Ifw for 600 s. Due to the relatively long cycle time, 100 cycles have been measured for this device to mitigate the risk of instability in the experimental setup over extended durations. The measured resonant wavelengths after programming and erasing are plotted in Fig. 2f, the optical memory shows consistent and repeatable switching behavior over 100 cycles, confirming its endurance capability.

Mechanisms and simulation

The imperfect interface transition between (100) Si and amorphous SiO2 introduces dangling bond traps, and these traps undergo filling and emptying during program and erase operations. The following charge switch of traps results in the hysteresis effect of the Si P-N junction-based waveguide. The transient behavior of donor-like traps is described by the rate equation

where FtD is the occupation probability of donor-like traps, vP and vN denote the thermal velocities for holes and electrons, σP and σN are the trap capture cross-sections for holes and electrons, P and N represent the concentrations of free holes and electrons, Fdeg is the degeneracy factor, ni is the intrinsic carrier concentration, EtD and Ei are the donor-like traps and intrinsic energy levels36. There are four distinct terms on the right side of Eq. (2): (1) a charge rate by capturing valence band holes, (2) a discharge rate to the valence band, (3) a discharge rate through conduction band electrons, and (4) a charge rate due to the emission of electrons to the conduction band. These charge/discharge rates linearly depend on the trap cross-sections σP and σN, which describe the interaction between carriers and traps. Therefore, σP and σN are functions of trap location distance d into the SiO2,

where the constants σP0 and σN0 are about 10−15 cm2 and 10−17 cm2, respectively37,38. κh and κe are the evanescent wavectors for electrons and holes,

where \({m}_{{{{\rm{h}}}}}^{* }\) and \({m}_{{{{\rm{e}}}}}^{* }\) are the effective masses of holes and electrons, EV and EC stand for the conduction band edge and valence band edge. In the subsequent simulations, it is assumed that the trap spatial density is uniform up to a certain depth and zero above that, and the traps are considered to be monoenergetic. The band diagram of the Si P-N junction under program operation is illustrated in Fig. 3a. At a high reverse bias close to the breakdown voltage, avalanche gain occurs inside the depletion region. The photon-generated carriers accelerate within the depletion region due to the high electric field, leading to the impact ionization events. Due to the significant difference between the ionization coefficients of holes (β) and electrons (α) in Si, impact ionization predominantly happens in electrons39,40. The current density contributed by electrons, JN, exhibits an exponential-like growth from left to right due to the increasing number of impact ionization-generated electrons. As the current density is uniform across the entire junction, the complementary hole current density, JP, is represented by the red curve in the middle chart of Fig. 3a. The average JP > JN inside the depletion region because of the electron-preferred impact ionization. The electron and hole number distribution can then be extracted from the current density by \(N={J}_{{{{\rm{N}}}}}/q{V}_{{{{\rm{dN}}}}}\) and P = JP/qVdP, where \({V}_{{{{\rm{dN}}}}}\) and VdP are the drift velocities of the electrons and holes. As JP > JN and \({V}_{{{{\rm{dN}}}}}\gg {V}_{{{{\rm{dP}}}}}\), the hole concentration P is much higher than the electron concentration N inside the depletion region. Therefore, the first term on the right side of Eq. (2), VPσPP(1 − FtD), dominates the transient behavior. The Si-SiO2 traps get charged by capturing holes. Conversely, the Si P-N junction is forward-biased to erase the memory. The band diagram and current density distribution of the erase-operated junction are shown in Fig. 3b. The JN and JP are almost at the same level due to the similar acceptor and donor doping concentrations, NA and ND, inside the Si junction. The electron concentration at − xP is \(N(-{x}_{{{{\rm{P}}}}})=\frac{{n}_{{{{\rm{i}}}}}^{2}}{{N}_{{{{\rm{A}}}}}}{{{{\rm{e}}}}}^{qV/{k}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}T}\) and the hole concentration at xN is \(P({x}_{{{{\rm{N}}}}})=\frac{{n}_{{{{\rm{i}}}}}^{2}}{{N}_{{{{\rm{D}}}}}}{{{{\rm{e}}}}}^{qV/{k}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}T}\), indicating that the P and N have similar concentrations. Therefore, the discharge term contributed by electrons is not negligible, the rate equation will lead to a new balance state with a smaller FtD.

Schematic of the mechanism of the Si optical ATM: band diagrams, current density distributions, and free carrier number distributions of the Si P-N junction during the program (a) and erase (b) operations. During the program operation, electrons (purple particles) undergo impact ionization along the x-direction, resulting in an exponentially increased electron current density JN. The complementary hole current density JP is then plotted. The corresponding carrier number distribution reveals an excess of holes compared to electrons. During the erase progarm, the junction is forward biased, the electron and hole current densities/carrier numbers become nearly equal. c Band diagrams of the Si-SiO2 interface during the program and erase operations. Excess holes (green particles) are captured by interface traps during the program operation and discharged into the valence band during the erase operation. d, Simulated trap occupation probability of the Si optical ATM at the virgin, program, erase, post-erase stay, and post-program stay states.

The band diagrams of the Si-SiO2 interface during the program and erase operations are shown in Fig. 3c. The traps are charged due to the significantly higher P concentration during the program operation, and they are discharged as the P ~ N during the erase operation. After the program and erase operations, the Si ATM is left unbiased, yet the alteration in the traps’ charge endures, continuing to influence the waveguide’s refractive index. The simulated occupation probability of traps, FtD, is plotted in Fig. 3d. In the virgin state, the device has not been probed at all, the traps are empty. During the program operation, the occupation probability gradually increases with time, and the saturation time is on the order of 103 s. On the contrary, the erase operation discharges the traps, where the erase speed is faster than the program due to the higher free carrier concentrations. The FtD quickly reduced from ~ 74% to ~ 22%, and then reaches a steady state. To show the non-volatility of this Si optical ATM, we also simulate the steady state after the erase and program operations, where P and N values are zero as there is no bias and current through the device. The occupation probability of traps remains constant without voltage.

In order to validate the model of the Si optical ATM, an additional device on the same chip has been measured to demonstrate the virgin, program, and erase states. Figure 4a shows the measured optical spectrum of the device, where the virgin state exhibits the shortest resonant wavelength, the program state shows the longest resonant wavelength, and the erase state has a slightly red-shifted resonant wavelength compared to the virgin state. The measured results align well with our simulated occupation probability in Fig. 3d, the erase operation cannot fully empty the charged traps. The corresponding resonant wavelength is plotted in Fig. 4b, the optical ATM can program/erase several times, allowing a repeatable non-volatile wavelength shift of more than 40 pm. The program and erase speeds are also measured to further verify our model. As depicted in Fig. 4c, the resonant wavelength versus operation time is measured every 60 s during the program (purple dots) and every 10 s during the erase (green dots) operations. The program operation takes about 1500 s to fully shift the Si optical memory, while the erase operation only requires 300 s to set the memory resonant wavelength back. The speed measurement also agrees well with the simulated results of our model. It is noteworthy that FtD is a normalized probability, the resonant wavelength shift is also influenced by the trap density at the Si-SiO2 interface. While the two Si optical memories reported here demonstrate a comparable non-volatile resonant wavelength shift of ~ 42 pm, the hero device on this chip enables a shift of ~ 71 pm, corresponding to an ultra-high ER of ~ 26 dB. Detailed spectrum and resonant wavelengths are provided in Supplementary Note 2.

The occupied traps at the Si-SiO2 interface place a fixed charge on the surface of the Si waveguide. This charge induces a doping redistribution within the Si P-N junction, thereby altering the refractive index of the waveguide. In Fig. 5a, the simulated doping concentration profiles of the Si P-N junction are compared without trapped charge (erase state) and with a charged trap density of 5 × 1012 cm−2 (program state). Given that the occupied traps carry positive charges, the P-type dopants are repelled from the surface, while the N-type dopants are attracted close to the surface. The corresponding transverse electric (TE) optical mode of the Si P-N junction-based waveguide can then be simulated for different doping profiles, as depicted in Fig. 5b. The traced effective refractive index change versus trapped charge concentrations is plotted in Fig. 5c. At a trapped defect density of 5 × 1012 cm−2, the effective index increases by approximately 9.6 × 10−5. At the same time, the free carrier absorption loss of the Si waveguide is reduced. As the orange curve shows, the loss reduces by ~ 1.3 dB cm−1. The calculated resonant wavelength change, derived from the simulated effective index change, is presented in Fig. 5d, where the Si MRR memory could shift about 45 pm with a 5 × 1012 cm−2 charged trap density. In order to verify the trap density, the corresponding Q factor and ER trends are plotted in Fig. 5e. The Q factor, ~ 6300, increases with higher trap density, and the ER rises from about 25 dB to 27 dB. Both trends align well with the measured results in Fig. 2a. The simulated wavelength shift, Q factor, and ER collectively corroborate the experimental measurements, affirming the consistency between simulation and device performance.

a Simulated doping concentration distributions of the Si P-N junction with 0 cm−2 and 5 × 1012 cm−2 trapped defect density. b Transverse electric (TE) mode energy distribution inside the Si P-N junction waveguide. c Simulated effective index change (purple) and loss change (orange) of the Si P-N junction waveguide versus trapped defect density. Corresponding d resonant wavelength change, e Q factor (purple) and extinction ratio change (orange) of the Si microring resonator memory versus trapped defect density, where the ⋆ indicates the measured results from the programmed Si optical memory.

Applications

The Si optical ATM showcases multiple non-volatile states using the standard Si photonics process, enabling the direct integration of memory functionality into existing Si photonic systems. For instance, MRR-based optical interconnects encounter a challenge in fabrication variances, as the resonant wavelength of MRR is sensitive to such variances41. Fine-tuning becomes necessary to align the MRR resonant wavelength precisely and avoid channel crosstalk. Leveraging the Si optical memory, this trimming process becomes straightforward, as the program/erase process of the MRR memory does not interfere with the volatile tuning of the Si MRRs. Consequently, it eliminates the need for energy-intensive thermal tuning in current optical interconnects. Figure 6a illustrates the measured optical spectrum of a 5-channel dense wavelength division multiplexing (DWDM) MRR modulator array before and after programming. Fabrication variances resulted in uneven channel spacing, with the narrowest gap between channels (ch) 5 and 1. To correct this, the ch1 MRR was programmed to induce a non-volatile redshift. The programmed spectrum, shown by the purple curve, exhibits a more uniform channel spacing compared to the initial spectrum, represented by the green curve. The difference in spacing between ch5-ch1 and ch1-ch2 was reduced by approximately 0.1 nm, bringing it closer to the ideal spacing. The coupling of crosstalk from the adjacent modulation channel in the DWDM array is plotted in Fig. 6b, where the optical power is shown on a linear scale and ch5 is modulated back and forth42. After programming, ch1 is positioned farther from ch5 compared to its initial state, effectively reducing crosstalk, as reflected by the optical power change at modulation frequencies in the top subplot of Fig. 6b. This reduction in optical crosstalk results in an improvement of about 2.5 dB. Such crosstalk improvements are even more pronounced with DWDM arrays with narrower channel spacing.

Trimming of optical interconnects: a Measured optical spectrum of a dense wavelength division multiplexing (DWDM) microring modulator array before and after trimming (inset: microscope image of the DWDM modulator array)45. The bottom panel provides a zoomed-in view of the spectrum within the dashed-line box, highlighting the programmed channel 1 (ch1). b Coupling of crosstalk from adjacent modulation channel in the DWDM array before and after trimming. Solid and dashed lines indicate the spectrum changes before and after modulation, while green and purple lines represent the DWDM array states before and after trimming, respectively. The zoomed-in section in the top chart reveals reduced crosstalk (purple) after trimming. Optical neural network: c Example implementation of an optical matrix-vector multiplier employing the microring resonator (MRR) optical memory weight bank44. A DWDM laser source is directed into the MRR memory weight bank, where the optical signals are weighted based on the MRR memory settings and summed by balanced photodiodes. d A neural layer considering the precision and noise of its optical implementation46, with precision and noise data derived from measurements of the Si memory (inset). e Conceptual illustration of a 4-layer optical neural network for handwritten-digital classification. f Corresponding testing accuracy and loss using the MNIST dataset for the ideal MRR without noise (dash lines) and the MRR optical memory (solid lines). The inset shows the testing truth table. g Inference power consumption of a N × N optical matrix-vector multiplier with heater-based MRR weights (black dash line) and optical memory-based MRR weights (red solid line).

Another application is the optical neural network (ONN), which recently has garnered significant interest due to its potential to drastically boost speed and energy efficiency by several orders of magnitude43. Unfortunately, the lack of optical memory creates a memory wall between the ONN chip and electrical memory, resulting in significant energy consumption for weight management. Our ATM device offers a solution to this bottleneck. An example implementation of an optical matrix-vector multiplier is illustrated in Fig. 6c, employing the MRR optical memory weight bank44. Incoming wavelength division multiplexed (WDM) signals are weighted by reconfigurable MRRs to realize multiplication. The weighted signals are then accumulated by the balanced photodiode for the output. Since the proposed MRR optical memory is fully compatible with high-speed MRR modulators45, ONN training can be achieved through the volatile MRR modulation effect. Once trained, the weights can be encoded into the MRRs using the non-volatile optical memory effect. As a result, ONN inference entails zero static energy consumption while achieving multiplication at the speed of light. As the ONN operates in the analog domain, its performance is constrained by the precision and noise characteristics of physical devices. To incorporate these practice parameters in the ONN, the optical neural layer is depicted in Fig. 6d, where the weights are normalized and then adjusted to accommodate MRR memory precision and noise46. The demonstrated optical memory enables a precision of 26 steps, with a standard deviation of overall noise of ~ 0.004, accounting for the MRR thermal drift and stochastic programming processes. A 4-layer ONN is employed to simulate the handwritten-digital classification using the MNIST dataset, as shown in Fig. 6e. The testing accuracy and loss of this ONN are illustrated in Fig. 6f, where the dash lines represent the ONN based on the ideal MRR with 27 precision and zero noise, and the solid lines are the ONN with the demonstrated MRR optical memory. For MNIST classification, the MRR optical memory-based ONN reaches a testing accuracy of ~ 94.8% and a testing cross-entropy loss of ~ 0.176, showing similar performance to the ideal MRR-based ONN. Additionally, the more complex Fashion-MNIST dataset was trained using the same ONN, where the MRR optical memory-based ONN achieved a testing accuracy of approximately 84.4%, also comparable to the ideal MRR-based ONN. More detailed results for the ONNs are presented in Supplementary Note 5. Thanks to the non-volatile nature of the MRR optical memory, weight power consumption during inference is effectively zero. Figure 6g illustrates the comparison of inference power consumption between the N × N matrix-vector multiplier using heater-based MRR weights and the one using optical memory-based MRR weights. The power consumption of traditional heater-based MRR weights increases with N2, dominating the overall power consumption. In contrast, the optical memory-based multiplier incurs power consumption only from the transmitter and receiver, which increases linearly with N. At N = 20, the power consumption of the optical memory-based matrix-vector multiplier is reduced by a factor of ~ 34. For the proposed ONN in Fig. 6e, the heater-based one exhibits an energy efficiency of 2.77 × 1012 MAC J−1. In contrast, the ATM-based ONN eliminates approximately 83% of the energy consumption associated with the weights, achieving an energy efficiency of 1.64 × 1013 MAC J−1, marking an improvement of about 5.9 times. Detailed calculation is provided in Supplementary Note 6.

Discussion

In this work, we demonstrate a non-volatile optical memory based on standard Si photonic devices. Diverging from existing memory technologies, the Si ATM leverages disparate current densities of holes and electrons from avalanche-multiplying photocurrent to generate hysteresis trapping charge at Si-SiO2 interface. With no alterations to the fabrication processes, the Si ATM maintains full compatibility with Si photonics foundries, making it seamlessly integrated into standard process design kit (PDK) and directly applicable in Si PICs. Furthermore, the Si ATM is a generic device that is not contingent on the specifications of a particular Si photonics foundry. While the Si ATMs reported in the main text were produced at Advanced Micro Foundry (AMF), we have successfully replicated a similar non-volatile memory phenomenon in a Si P-N junction-based MRR fabricated at CEA-Leti. The detailed results for the Leti-fabricated optical memory are provided in Supplementary Note 3.

The showcased Si optical memory exhibits a non-volatile shift of approximately 42 pm in its resonant wavelength, yielding a commendable ER of ~ 18 dB. The extent of non-volatile shift depends on the interface trap density, and the leading device on the wafer can attain an impressive resonant wavelength shift of ~ 71 pm with an ultra-high ER of ~ 26 dB. Consequently, enhancing the Si ATM shift is achievable through the engineering of the interface trap density. This Si optical memory also facilitates multiple states, with 26 distinct states achieved by varying the program time. The retention performance of the Si optical memory is commendable, as both the program and erase states maintain a highly stable resonant wavelength for at least 24 hours. Furthermore, the cyclability of the Si ATM is validated through 100 program-erase cycles, affirming the device’s endurance and demonstrating consistent and repeatable switching behavior. A survey of recent non-volatile optical memories is provided in Table 1. Benefiting from the ATM mechanism, this device boasts an exceptionally streamlined material stack Si, which necessitates no alterations to current Si photonics foundry processes. While the performance of the Si ATM is on par with other advanced technologies, its primary limitation lies in the relatively modest switching speed. This speed can be enhanced through better control and engineering of the trap charge rate. On the other hand, the gradual charging process affords the ATM a greater number of distinct states compared to its competitors, further enhancing its versatility.

A charge-trapping model has been developed for the Si ATM. The rate equation of the occupation probability of donor-like traps highly depends on the concentrations of free electrons and holes. Given that electrons are much easier to impact ionization than holes in Si, and the drift velocity of electrons is significantly faster than that of holes, the free holes concentration is way larger than that of free electrons within the device during the program operation. The surplus holes thus effectively fill the donor-like traps, establishing a non-volatile charge difference at the Si-SiO2 interface. This fixed charge offset, in turn, alters the doping profile inside the Si junction, interacting with the optical mode within the waveguide. The simulated results agree well with the measurements, offering an elucidation for the observed behavior of this innovative optical memory.

The performance of the all-Si optical memory, according to the trapping model’s rate equation, is highly dependent on factors such as interface trap density, trap energy levels, trap capture cross-sections, and unbalanced free carrier levels. Future work aims to enhance the initial performance of the ATM by engineering and controlling the interface traps. Another promising approach to enhancing Si ATM performance is the introduction of a vertical electric field. Unlike the high electric fields required in electronic flash memory for Fowler-Nordheim tunneling and hot-carrier injection, a relatively low electric field could be sufficient to accelerate excess holes, thereby increasing the trap occupation probability and improving the response speed. These enhancements could result in a more substantial refractive index change (i.e., a larger wavelength shift) at room temperature and improve the switching speed by three to four orders of magnitude. Currently, the program laser wavelength is in the O-band due to grating coupler limitations, using a shorter wavelength laser could generate multiplied photocurrent more efficiently, further reducing energy consumption. Additionally, the ATM mechanism is not confined to the MRR structure; the non-volatile index change phenomenon can be seamlessly integrated into other Si photonic components. In summary, an optical memory ATM is demonstrated on the Si photonics platform with zero change of standard processes, paving a simpler and most cost-efficient pathway to enhance the performance of existing PICs by eliminating the electronic memory latency, reducing times for optoelectronic conversion, and minimizing static energy consumption. Si ATM can be applied to various applications such as trimming in optical interconnects and inference in ONNs. By leveraging Si ATM, ONNs retain their ability to potential boost speed while minimizing energy consumption for weight management.

Methods

Fabrication

The Si optical memories were fabricated at Advanced Micro Foundry (AMF), Singapore. The chips are based on industry-standard 220 nm-thick SOI wafers. The Z-shape junction was formed from Phosphorous (for N-type) and Boron (for P-type) implants.

Measurements

The bias voltage was supplied by a Keithley 2400 source meter. An O-band tunable laser Santec TSL-550 was used as the light source for photocurrent and optical spectrum. All spectrum and resonant wavelengths were measured without bias voltage for non-volatile performance. The optical spectrum of the multiple states was measured without bias voltage after every 60 s of programming. The retention results were measured after a one-time program/erase operation, and then the spectrum was recorded without bias voltage every 10 minutes over 24 hours. The endurance results for 100 cycles are measured with an automatic setup that uses the same stress conditions for all program/erase operations.

Simulations

The rate equation of donor-like traps was solved by the solve nonstiff differential equations - low order method (ode23) in Matlab. The donor-like traps energy level, EtD, was chosen to be 0.5 eV. The free carrier concentrations P and N were calculated from the current densities during program and erase operations. The doping profiles of the Si P-N junction under different trapped defect density, shown in Fig. 5a, were simulated by Lumerical Charge, assuming a 6 nm thick defect region at the interface. The simulated doping profiles were then imported into Lumerical Mode to simulate the corresponding TE mode in Fig. 5b and extract effective refractive index change and loss change of the Si waveguide.

The ONN simulation utilized AnalogVNN, a PyTorch-based framework designed to incorporate the precision and noise characteristics of ONNs46. A 4-layer ONN architecture, depicted in Fig. 6c, was utilized for the MNIST handwritten digit classification task. The input digital image is resized from the original 28 × 28 to 8 × 8 pixels using bilinear interpolation to reduce the length of the input vector, which is fed into a linear optical neural layer. The three subsequent optical neural layers comprised matrices of sizes (8 × 8) × 20, 20 × 10, and 10 × 10. The activation function (f) for the first two layers is a Gaussian error linear unit (GeLU) and the activation function for the output layer is a Softmax function. The optimizer employed was Adam.

The total power consumption of an N × N vector-matrix multiplier is determined by the sum of power from N transmitters at the fan-in stage, N receivers at the fan-out stage, and N2 weights at the multiplication stage. It is expressed as Pmult = NPTX + NPRX + N2PW, where PTX represents transmitter power, PRX denotes receiver power, and PW stands for weight module power47. In the inference power calculation of Fig. 6e, the power consumption of the MRR modulator, balanced photodiode, heater-based MRR weight, and optical memory-based MRR weight is 1.3 mW, 0.5 mW, 3 mW, and 0 mW, respectively. More detailed power calculation is provided in Supplementary Note 6.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Shastri, B. J. et al. Photonics for artificial intelligence and neuromorphic computing. Nat. Photonics 15, 102–114 (2021).

Zenke, F., Agnes, E. J. & Gerstner, W. Diverse synaptic plasticity mechanisms orchestrated to form and retrieve memories in spiking neural networks. Nat. Commun. 6, 6922 (2015).

Ríos, C. et al. In-memory computing on a photonic platform. Sci. Adv. 5, eaau5759 (2019).

Alexoudi, T., Kanellos, G. T. & Pleros, N. Optical ram and integrated optical memories: a survey. Light.: Sci. Appl. 9, 91 (2020).

Liu, L. et al. An ultra-small, low-power, all-optical flip-flop memory on a silicon chip. Nat. Photonics 4, 182–187 (2010).

Kuramochi, E. et al. Large-scale integration of wavelength-addressable all-optical memories on a photonic crystal chip. Nat. Photonics 8, 474–481 (2014).

Malacarne, A., Bogoni, A. & Poti, L. Erbium–ytterbium-doped fiber-based optical flip-flop. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 19, 904–906 (2007).

Berrettini, G. et al. All-optical digital circuits exploiting soa-based loop memories. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 18, 847–858 (2011).

Ríos, C. et al. Integrated all-photonic non-volatile multi-level memory. Nat. photonics 9, 725–732 (2015).

Zhang, Y. et al. Broadband transparent optical phase change materials for high-performance nonvolatile photonics. Nat. Commun. 10, 4279 (2019).

Zheng, J. et al. Gst-on-silicon hybrid nanophotonic integrated circuits: a non-volatile quasi-continuously reprogrammable platform. Opt. Mater. Express 8, 1551–1561 (2018).

Fang, Z. et al. Non-volatile materials for programmable photonics. APL Materials 11 (2023).

Scott, J. Applications of modern ferroelectrics. science 315, 954–959 (2007).

Mikolajick, T., Schroeder, U. & Slesazeck, S. The past, the present, and the future of ferroelectric memories. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 67, 1434–1443 (2020).

Geler-Kremer, J. et al. A non-volatile optical memory in silicon photonics. In 2021 Optical Fiber Communications Conference and Exhibition (OFC), 1–3 (IEEE, 2021).

Honardoost, A., Henriksson, J., Kwon, K., Luo, J. & Wu, M. C. Low-loss wafer-bonded silicon photonic mems switches. In 2022 Optical Fiber Communications Conference and Exhibition (OFC), 1–3 (IEEE, 2022).

Han, S. et al. 32 × 32 silicon photonic mems switch with gap-adjustable directional couplers fabricated in commercial cmos foundry. J. Opt. Microsyst. 1, 024003 (2021).

Quack, N. et al. Integrated silicon photonic mems. Microsyst. Nanoengineer. 9, 27 (2023).

Barrios, C. A. & Lipson, M. Silicon photonic read-only memory. J. Lightwave Technol. 24, 2898 (2006).

Song, J.-F. et al. Integrated photonics with programmable non-volatile memory. Sci. Rep. 6, 22616 (2016).

Zhu, R. et al. Non-volatile optoelectronic memory based on a photosensitive dielectric. Nat. Commun. 14, 5396 (2023).

Cheung, S. et al. Ultra-power-efficient, electrically programmable, multi-state photonic flash memory on a heterogeneous iii-v/si platform. Laser & Photonics Reviews 2400001 (2024).

Cheung, S. et al. Non-volatile iii-v/si photonic charge-trap flash memory. In 2023 IEEE Photonics Conference (IPC), 1–2 (IEEE, 2023).

Tossoun, B., Sheng, X., Strachan, J. & Liang, D. The memristor laser. In 2020 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM), 7-6 (IEEE, 2020).

Cheung, S. et al. Heterogeneous iii-v/si non-volatile optical memory: A mach-zehnder memristor. In CLEO: Science and Innovations, STu5G–6 (Optica Publishing Group, 2022).

Youngblood, N., Ríos Ocampo, C. A., Pernice, W. H. & Bhaskaran, H. Integrated optical memristors. Nature Photonics 1–12 (2023).

Cheung, S. et al. Non-volatile memristive iii-v/si photonics. In 2023 IEEE Silicon Photonics Conference (SiPhotonics), 1–2 (IEEE, 2023).

Hu, H. et al. Inkjet-printed tungsten oxide memristor displaying non-volatile memory and neuromorphic properties. Advanced Functional Materials 2302290 (2023).

Adam, G. C., Khiat, A. & Prodromakis, T. Challenges hindering memristive neuromorphic hardware from going mainstream. Nat. Commun. 9, 5267 (2018).

Stathis, J. H. & Zafar, S. The negative bias temperature instability in mos devices: A review. Microelectron. Reliab. 46, 270–286 (2006).

Hehenberger, P. P.Advanced characterization of the bias temperature instability. Ph.D. thesis, Technische Universität Wien (2011).

Rzepa, G. et al. Physical modeling of nbti: From individual defects to devices. In 2014 International Conference on Simulation of Semiconductor Processes and Devices (SISPAD), 81–84 (IEEE, 2014).

Entner, R.Modeling and simulation of negative bias temperature instability. Ph.D. thesis, Technische Universität Wien (2007).

Füssel, W., Schmidt, M., Angermann, H., Mende, G. & Flietner, H. Defects at the si/sio2 interface: their nature and behaviour in technological processes and stress. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detect. Associated Equip. 377, 177–183 (1996).

Yuan, Y. et al. Mechanisms of enhanced sub-bandgap absorption in high-speed all-silicon avalanche photodiodes. Photonics Res. 11, 337–346 (2023).

Simulating the hysteresis effects of si/sio2 interface traps. Silvaco Inc (2010).

Baba, S., Kita, A. & Ueda, J. Mechanism of hot carrier induced degradation in mosfet’s. In 1986 International Electron Devices Meeting, 734–737 (IEEE, 1986).

Hofmann, K. R., Werner, C., Weber, W. & Dorda, G. Hot-electron and hole-emission effects in short n-channel mosfet’s. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 32, 691–699 (1985).

Tan, C. et al. Avalanche noise measurement in thin si p+-in+ diodes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 76, 3926–3928 (2000).

Kang, Y. et al. Monolithic germanium/silicon avalanche photodiodes with 340 ghz gain–bandwidth product. Nat. photonics 3, 59–63 (2009).

Yuan, Y. et al. All-silicon microring transceivers enabling single-lane throughput exceeding 128 gb/s. In Frontiers in Optics, FM5D–4 (Optica Publishing Group, 2023).

Sharma, J. et al. Silicon photonic microring-based 4 × 112 gb/s wdm transmitter with photocurrent-based thermal control in 28-nm cmos. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 57, 1187–1198 (2021).

Feldmann, J. et al. Parallel convolutional processing using an integrated photonic tensor core. Nature 589, 52–58 (2021).

Tait, A. N. et al. Neuromorphic photonic networks using silicon photonic weight banks. Sci. Rep. 7, 7430 (2017).

Yuan, Y. et al. A 5 × 200 gbps microring modulator silicon chip empowered by two-segment z-shape junctions. Nat. Commun. 15, 918 (2024).

Shah, V. & Youngblood, N. AnalogVNN: A fully modular framework for modeling and optimizing photonic neural networks. APL Mach. Learn. 1, 026116 (2023).

Dabos, G. et al. Neuromorphic photonic technologies and architectures: scaling opportunities and performance frontiers. Opt. Mater. Express 12, 2343–2367 (2022).

Ríos, C. et al. Ultra-compact nonvolatile phase shifter based on electrically reprogrammable transparent phase change materials. PhotoniX 3, 26 (2022).

Fang, Z. et al. Ultra-low-energy programmable non-volatile silicon photonics based on phase-change materials with graphene heaters. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 842–848 (2022).

Geler-Kremer, J. et al. A ferroelectric multilevel non-volatile photonic phase shifter. Nat. Photonics 16, 491–497 (2022).

Taki, K. et al. Nonvolatile optical phase shift in ferroelectric hafnium zirconium oxide. Nat. Commun. 15, 3549 (2024).

Tossoun, B. et al. High-speed and energy-efficient non-volatile silicon photonic memory based on heterogeneously integrated memresonator. Nat. Commun. 15, 551 (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Y. conceptualized the devices, taped out the chips, performed the measurements, built the model, performed the simulations, and wrote the manuscript. Y.P., S.C., W.V.S., and J.Z. participated in the measurements, S.H. participated in the simulations, Z.H., D.L., M.F., and R.G.B supervised the study and gave important technical advice. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

This manuscript has been previously reviewed at another journal that is not operating a transparent peer review scheme. The manuscript was considered suitable for publication without further review at Communications Physics.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yuan, Y., Peng, Y., Cheung, S. et al. All-silicon non-volatile optical memory based on photon avalanche-induced trapping. Commun Phys 8, 39 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-01934-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-01934-4