Abstract

Bone lengthening and fracture repair depend on the anabolic properties of chondrocytes that function in an avascular milieu. The limited supply of oxygen and nutrients calls into question how biosynthesis and redox homeostasis are guaranteed. Here we show that glucose metabolism by the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) is essential for endochondral ossification. Loss of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase in chondrocytes does not affect cell proliferation because reversal of the non-oxidative PPP produces ribose-5-phosphate. However, the decreased NADPH production reduces glutathione recycling, resulting in decreased protection against the reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced during oxidative protein folding. The disturbed proteostasis activates the unfolded protein response and protein degradation. Moreover, the oxidative stress induces ferroptosis, which, together with altered matrix properties, results in a chondrodysplasia phenotype. Collectively, these data show that in hypoxia, the PPP is crucial to produce reducing power that confines ROS generated by oxidative protein folding and thereby controls proteostasis and prevents ferroptosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Bioenergetic and biosynthetic processes are necessary for tissue growth and functioning and rely on appropriate oxygen and nutrient supply. Therefore, most tissues are highly vascularized1, but the growth plate of long bones is an exception, as the residing chondrocytes proliferate and produce substantial amounts of collagenous extracellular matrix in an avascular environment2. Insight into the metabolic profile of chondrocytes will inform which nutrients and pathways are crucial to support the anabolic processes that regulate not only bone growth but also fracture repair and tissue regenerative therapies in an avascular environment.

Growth plate chondrocytes generate ATP mainly through glycolysis, as the diffusion of oxygen and fatty acids in the collagen-rich matrix is limited3,4,5. Hypoxia occurs especially in the centre of the growth plate and the residing chondrocytes depend on HIF signalling to metabolically adapt and survive3,6. However, chondrocytes located at the periphery of the growth plate require some level of glucose oxidation to avoid energy stress and maintain adequate proliferation and matrix synthesis4.

Along with energy homeostasis, biomass production is essential during the successive stages of chondrocyte differentiation, which are characterized by proliferation, matrix production and hypertrophy. In chondrocytes, glutamine metabolism and glucose-mediated serine production contribute to nucleotide and protein synthesis, which are necessary for proliferation and matrix production7,8. Biosynthetic pathways are, in general, also closely linked to redox reactions, but the importance of these redox pathways for the highly anabolic chondrocytes is poorly studied. The reducing power that is required for the synthesis of lipids, deoxyribonucleotides and proline is provided by NADPH, and the largest source of NADPH in the cytosol is the PPP9. NADPH also contributes to the recycling of oxidized (GSSG) to reduced glutathione (GSH), which scavenges ROS and thereby protects cells from oxidative damage. ROS are mainly produced in the mitochondria during oxidative phosphorylation, but they are also generated in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) when disulfide bridges are formed during oxidative protein folding, especially in cell types with a high protein production load like hepatocytes or pancreatic β cells. Disulfide bonds are primarily formed by protein disulfide isomerase (PDI), an ER oxidoreductase, which itself becomes reduced during this reaction. To maintain oxidative protein folding, PDI is re-oxidized by ER oxidoreductase 1 (ERO1), which in turn becomes re-oxidized by transferring electrons to oxygen, thereby generating H2O2. The produced H2O2 is converted to H2O either by ER peroxidases, which simultaneously recycle ER oxidoreductases and allow continuous protein folding, or by antioxidants such as GSH, which is then converted into GSSG. The glutathione redox state (GSH:GSSG) is thus important for oxidative protein folding and ER homeostasis, but the link with NADPH is not well characterized10,11.

Perturbations in protein folding or redox balance in the ER activate the unfolded protein response (UPR)12. To prevent proteotoxicity, the UPR not only increases protein-folding capacity but simultaneously reduces protein-folding load by stimulating proteasomal and lysosomal protein degradation. Prolonged ER stress ultimately leads to apoptosis or ferroptosis and thus determines cellular outcome. ER stress and UPR are recognized to be important regulators of chondrocyte behaviour, as gene mutations of extracellular matrix proteins or disruption of the UPR pathway result in chondrodysplasia phenotypes13,14,15,16. However, important questions remain on how cells secure proteostasis through redox reactions, especially in a nutrient-restricted environment like the growth plate.

In this study, we questioned how the metabolic profile of chondrocytes contributes to biosynthesis and redox homeostasis in this avascular environment. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) on murine growth plates revealed that the PPP is upregulated in differentiating, matrix-producing chondrocytes. Using in vivo and in vitro models, we demonstrate that the oxidative PPP (oxPPP) is dispensable for chondrocyte proliferation but crucial for oxidative protein folding and prevention of ferroptosis during differentiation in a hypoxic environment, indicating that PPP-derived NADPH is vital for ER redox homeostasis and cell survival when oxygen levels are limiting.

Results

The PPP is dynamically regulated in the growth plate

To study whether growth plate chondrocytes adjust their metabolic profile in relation to the various anabolic processes during the successive phases of differentiation, we performed scRNA-seq on isolated and digested growth plates from 3-day-old mice (Fig. 1a). After quality filtering, 7,109 cells were clustered according to their gene expression profile and cells were visualized using t-distributed stochastic neighbour embedding (t-SNE) (Fig. 1b,c and Extended Data Fig. 1a). We identified the three main chondrocyte differentiation stages using previously described marker genes (Extended Data Fig. 1b), including resting chondrocytes (Grem1, Efemp1, Frzb, CD200), columnar chondrocytes (Gdf10, Prelp) and hypertrophic chondrocytes (Ihh, Col10a1, CD200)17,18,19,20. In addition, our dataset also contained a cluster of actively cycling cells (MKi67; Fig. 1c and Extended Data Fig. 1b) that also expressed marker genes of columnar chondrocytes, confirming that the columnar region is characterized by proliferative chondrocytes. Interestingly, we also identified a cluster high in Fosl1 and Tnfrsf12a expression (Fig. 1c and Extended Data Fig. 1b), marker genes that were described to typify borderline cells, a population of transient mesenchymal progenitors in the growth plate20. Finally, we observed a small cluster of cells expressing Col1a1, probably cells from the adjacent bone (Fig. 1c and Extended Data Fig. 1b).

a, Schematic overview of the experimental setup for scRNA-seq of postnatal day 3 (P3) growth plates (n = 2). b, t-SNE visualization of cell populations in P3 growth plates. c, Heatmap of gene expression levels of the top 20 marker genes for resting chondrocytes (RCH), columnar chondrocytes (CCH), hypertrophic chondrocytes (HCH), actively proliferating cells (PC), borderline cells (BC) and contaminant cells (CC). A complete list of genes is provided in Supplementary Table 1. d, Pseudotime trajectory of RCH, CCH and HCH (left) and Loess regression-smoothened gene expression of indicated marker genes (right). Comp, component. e, Loess regression-smoothened gene expression of indicated glucose-related metabolic genes and gene sets. TCA, tricarboxylic acid; SSP, serine synthesis pathway. f G6PDH immunostaining on tibia growth plates at P3 (n = 5). Scale bar, 100 µm. g, 6-Phosphogluconate (6-P-gluconate) labelling from [1,2]-13C2 glucose (glc) during proliferation (prolif) or differentiation (diff) (n = 4). Relevant mass distribution vectors (MDVs) are shown.

To explore the link between chondrocyte metabolism and stage-specific anabolic processes, we analysed the expression level of curated KEGG metabolic gene sets in resting, columnar and hypertrophic chondrocytes and categorized them into seven different expression profiles based on their dynamic pattern (Extended Data Fig. 1c). Given that glucose is an important bioenergetic and biosynthetic source for chondrocyte function, we focused on glucose metabolism and observed that different glucose-linked metabolic pathways displayed distinct spatial patterns. To better visualize the dynamic profile, we performed trajectory interference analysis to deduce the differentiation trajectory from resting to hypertrophic chondrocyte (Fig. 1d) and mapped curated KEGG gene sets of glucose-catabolizing pathways. The expression of glycolysis-related genes increased in the columnar region with a maximum at the pre-hypertrophic stage followed by a decline in the hypertrophic chondrocytes (Fig. 1e). Interestingly, compared to the glycolysis expression profile, the gene expression for the tricarboxylic acid cycle and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) showed a different, almost reversed profile, with maximum levels in the resting and hypertrophic zones (Fig. 1e). This mirrored pattern between glycolysis and OXPHOS can be explained by the observation that columnar chondrocytes in the central region of the growth plate are the most distant from blood vessels and thus reside in a more hypoxic region, whereas resting and hypertrophic chondrocytes localize closer to the vasculature, allowing for oxygen-consuming glucose catabolism, as evidenced by transgenic mouse models4,6,21. In addition to the dynamic profile of glycolysis and OXPHOS, we observed a transient upregulation of serine synthesis pathway-linked gene expression in columnar chondrocytes (Fig. 1e), confirming our findings that the serine synthesis pathway is important for chondrocyte proliferation7. Lastly, pseudotime analysis also showed a dynamic regulation of genes of the PPP during chondrocyte maturation, with an increase during differentiation to columnar chondrocytes followed by a modest downregulation during hypertrophy (Fig. 1e).

The PPP contributes to cell proliferation through the production of ribose-5-phosphate but also to biosynthesis and redox homeostasis through the production of NADPH. How biosynthesis and redox homeostasis are regulated in the avascular growth plate is largely unknown; therefore, we focused on understanding the function of the PPP in this anabolic and largely hypoxic tissue. We first confirmed the dynamic profile of the PPP during chondrocyte differentiation by immunohistological staining of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH), the rate-limiting enzyme of the PPP. G6PDH was highly expressed in the resting zone, and thus fits with its function during proliferation but was also vastly detected in the pre-hypertrophic region, suggesting that G6PDH controls chondrocyte differentiation in the neonatal growth plate (Fig. 1f and Extended Data Fig. 2a). In addition, [1,2]-13C2-glucose-tracing in cultured growth plate chondrocytes showed that 6-phosphogluconate was more than 90% m+2-labelled during proliferation and differentiation (Fig. 1g and Extended Data Fig. 2b). Of note, the differentiation state was confirmed by increased expression of Col2a1 and Col10a1 (Extended Data Fig. 2c). These data indicate that glucose is metabolized through the oxPPP during both these processes. Taken together, our data indicate that the PPP is dynamically regulated in growth plate chondrocytes during bone development.

G6PDH determines chondrocyte survival but not proliferation

The PPP generates metabolic intermediates needed for cell proliferation, biosynthesis and prevention of oxidative stress. To study whether the PPP is critical during bone development, we deleted G6PDH in growth plate chondrocytes by crossing G6pdhfl/fl mice with collagen type 2 (Col2)-Cre transgenic mice. The resulting conditional knockout mice (G6pdhchon−) showed an efficient and chondrocyte-specific deletion of G6PDH, demonstrated at the gene expression and protein level (Extended Data Fig. 3a,b). G6pdhchon− neonatal mice were viable but smaller than their wild-type (WT) littermates (G6pdhchon+) as evidenced by a decrease in body weight and tibia length (Extended Data Figs. 3c,d and 4a,b). Histological analysis of the neonatal growth plate showed not only a reduction in size but also disorganization of the columnar and hypertrophic zone, especially in the central region (Fig. 2a,b and Extended Data Fig. 4c). This lack of columnar alignment was associated with decreased cell density (Fig. 2c), as quantified on Hoechst-stained sections, and with an increase in collagen type II-positive extracellular matrix (Extended Data Fig. 3e,f).

a,b, H&E staining of P3 growth plates of WT (G6pdhchon+) and chondrocyte-specific G6PDH-deficient (G6pdhchon−) mice (a), with quantification of the growth plate area (b) (n = 15; unpaired two-sided Student’s t-test vs G6pdhchon+). Boxed areas are magnified in a (right panels). Scale bar, 100 µm. c, Cell density in the resting and columnar zones of P3 G6pdhchon+ and G6pdhchon− growth plates, quantified on Hoechst staining (n = 8; unpaired two-sided Student’s t-test vs G6pdhchon+). d,e, BrdU immunostaining of P3 G6pdhchon+ and G6pdhchon− growth plates (d), with quantification of BrdU+ cells in the resting and columnar zones (e) (n = 8; unpaired two-sided Student’s t-test vs G6pdhchon+). Scale bar, 100 µm. f, Schematic of the effect of G6PDH deletion on oxPPP and non-oxPPP activity. Glc, glucose; glc-6-P, glucose-6-phosphate; TKT, transketolase. g, UMP m+1 (oxPPP) and m+2 (non-oxPPP) labelling from [1,2]-13C2 glucose in G6pdhchon+ and G6pdhchon− chondrocytes (n = 4; unpaired two-sided Student’s t-test vs G6pdhchon+). h, TUNEL staining on P3 G6pdhchon+ and G6pdhchon− growth plates (n = 8). Scale bar, 100 µm. i, Dead cells, measured by SYTOX Green flow cytometry, in differentiated hypoxic chondrocytes from G6pdhchon+ and G6pdhchon− mice (n = 3; unpaired two-sided Student’s t-test vs G6pdhchon+). j, NADPH and NADP+ levels in differentiated hypoxic chondrocytes from G6pdhchon+ and G6pdhchon− mice (n = 3; unpaired two-sided Student’s t-test vs G6pdhchon+). AU, arbitrary units. k, NADPH:NADP+ ratio in differentiated hypoxic chondrocytes from G6pdhchon+ and G6pdhchon− mice (n = 3; unpaired two-sided Student’s t-test vs G6pdhchon+). l, GSH:GSSG ratio in differentiated hypoxic chondrocytes from G6pdhchon+ and G6pdhchon− mice (n = 3; unpaired two-sided Student’s t-test vs G6pdhchon+). m, H2O2 levels, quantified by CellMeter Hydrogen Peroxide flow cytometry, in differentiated hypoxic chondrocytes from G6pdhchon+ and G6pdhchon− mice (n = 3; unpaired two-sided Student’s t-test vs G6pdhchon+). MFI, mean fluorescence intensity. n, Schematic of the effect of G6PDH deletion on growth plate chondrocytes. The data are presented as means ± s.d.

Because the PPP is critical for cell proliferation by producing ribose-5-phosphate, the backbone for nucleotide synthesis, we investigated whether cell proliferation was affected in G6pdhchon− mice. Interestingly, proliferation was similar in both genotypes as measured by BrdU immunohistochemistry or flow cytometry (Fig. 2d,e and Extended Data Fig. 3g). A possible explanation for this observation is that ribose-5-phosphate in G6PDH-null chondrocytes is generated by reversal of the non-oxidative arm of the PPP (non-oxPPP), which results in the conversion of glycolytic intermediates (fructose-6-P and glyceraldehyde-3-P) into ribose-5-phosphate by transketolase and transaldolase (Fig. 2f). To investigate this hypothesis, we performed [1,2]-13C2-glucose tracing into uridine monophosphate (UMP) as a proxy for ribose-5-phosphate. Generation of ribose-5-phosphate by the oxPPP will result in UMP m+1 labelling, whereas metabolization by the non-oxPPP will produce UMP m+2 labelling (Extended Data Fig. 2b). We observed, as expected, a significant decrease in UMP m+1 labelling in G6PDH-deficient chondrocytes but also noted an increase in UMP m+2 labelling, indicative of enhanced non-oxPPP activity (Fig. 2g). As further proof, we inhibited transketolase (non-oxPPP) activity by oxythiamine and observed a decrease in UMP m+2 labelling in both genotypes, but only WT chondrocytes showed an upregulation of UMP m+1 labelling, indicating that only WT cells could increase oxPPP activity as compensation (Extended Data Fig. 3h,i). Accordingly, oxythiamine treatment decreased cell proliferation in mutant but not WT chondrocytes (Extended Data Fig. 3j). These data indicate that the oxPPP is not necessary for the proliferation of chondrocytes as they can also produce ribose-5-phosphate by reversing the non-oxPPP.

As the observed hypocellularity (Fig. 2c) was not associated with a decrease in cell proliferation, we questioned whether cell viability was decreased in G6pdhchon− growth plates. We observed, especially in the central region, an increase in TUNEL-positive cells in mutant growth plates, indicative of cell death (Fig. 2h and Extended Data Fig. 5a). As this central region consists of differentiating chondrocytes but is also known to be highly hypoxic3,4, we reasoned that G6PDH is necessary for the survival of hypoxic differentiating chondrocytes. In vitro analysis showed that cell viability of proliferating G6PDH-null chondrocytes, both in normoxic (21% O2) and hypoxic (1% O2) conditions, was similar to WT cells (Extended Data Fig. 5b,c). However, differentiation of mutant but not WT chondrocytes in hypoxia resulted in a significant increase in cell death, a finding that accords with the TUNEL immunohistochemistry (Fig. 2i and Extended Data Fig. 5b,c). These data indicate that oxPPP activity is necessary to maintain cell viability in growth plate chondrocytes, especially during differentiation in hypoxic conditions.

G6PDH controls NADPH-mediated glutathione recycling

We next investigated how G6PDH deficiency decreased cell viability of differentiating hypoxic chondrocytes. In addition to producing ribose-5-phosphate, the PPP mediates the conversion of NADP+ to NADPH, which is a reducing cofactor in biosynthetic processes and necessary in the recycling of GSSG to GSH, an important antioxidant. Therefore, we wondered whether PPP-produced NADPH is critical for preventing oxidative stress during chondrocyte differentiation in hypoxia but less crucial during proliferation or normoxic conditions. Metabolomics analysis showed a decrease in NADPH in hypoxic mutant chondrocytes, both during proliferation and differentiation, resulting in a reduced NADPH:NADP+ ratio, indicating that hypoxic chondrocytes depend on the PPP for sufficient NADPH production and that other NADPH-generating pathways cannot compensate (Fig. 2j,k and Extended Data Fig. 5d–f). In addition, we detected a manifest increase in GSSG, resulting in a decreased GSH:GSSG ratio, during proliferation and differentiation of hypoxic G6PDH-null chondrocytes (Fig. 2l and Extended Data Fig. 5g–i) and in G6pdhchon− growth plates (Extended Data Fig. 5j), indicating impaired GSSG recycling. Moreover, G6PDH-null chondrocytes and G6pdhchon− growth plates showed an increase in total glutathione (GSH + GSSG) levels (Extended Data Fig. 5k,l), suggesting increased de novo GSH synthesis. Indeed, the increase in total glutathione was accompanied by an increase in gene expression of the transporters of amino acids necessary for de novo GSH synthesis (Slc1a4, cysteine; Slc1a5, glutamine; Slc6a9, glycine; Slc7a11, cystine; Extended Data Fig. 5m). Finally, H2O2 levels were significantly increased in cultured G6PDH-null chondrocytes but only during differentiation in hypoxia, indicating that the decreased NADPH:NADP+ and GSH:GSSG ratios can still prevent oxidative stress during proliferation but not during differentiation, probably because redox balance is more challenged during differentiation (Fig. 2m and Extended Data Fig. 5n–p).

Collectively, these findings show that G6PDH is necessary in chondrocytes to maintain NADPH-mediated GSSG recycling and redox homeostasis to prevent oxidative stress and cell death, especially during chondrocyte differentiation in the hypoxic centre of the growth plate (Fig. 2n).

G6PDH is linked to protein processing during differentiation

To further investigate the underlying mechanisms, we performed scRNA-seq on growth plates from G6pdhchon+ and G6pdhchon− pups. After quality filtering, 16,827 cells were clustered, visualized using t-SNE and annotated using the previously described marker genes (Fig. 3a and Extended Data Fig. 6a,b). Each genotype contained similar percentages of cells from each of the described clusters, but t-SNE visualization showed a substantial disparity between G6pdhchon+ and G6pdhchon− columnar and hypertrophic chondrocytes, indicative of phenotypical differences between genotypes (Fig. 3b). To explore which processes were altered in G6PDH-deficient chondrocytes, we performed gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) comparing G6pdhchon− versus G6pdhchon+ chondrocytes using curated KEGG pathways (Fig. 3c). G6pdhchon− mice showed an upregulation of KEGG pathways for ‘proteasome’, ‘protein processing in ER’ and ‘ferroptosis’, suggesting that G6PDH deletion affects proteostasis and lipid peroxidation, processes that can be linked to increased oxidative load. Furthermore, when we performed GSEA for each of the chondrocyte differentiation stages separately, we observed that among the three upregulated pathways, ‘protein processing in ER’ was ranked highest in resting chondrocytes, but ‘proteasome’ was top-ranked in columnar and ‘ferroptosis’ in hypertrophic chondrocytes, suggesting that the phenotype progressively evolves during chondrocyte differentiation from a homeostatic adaptive response to cell death (Extended Data Fig. 6c–e). These data are in line with our histological findings showing that the disorganization and reduced cell number were primarily observed in the central, (pre-)hypertrophic region of the growth plate, and with our in vitro data revealing that G6PDH deficiency increases oxidative stress and cell death primarily in hypoxic differentiating chondrocytes. Of note, G6pdhchon− growth plates also showed an increase in the metabolic pathways ‘glycine, serine and threonine metabolism’ and ‘one carbon pool by folate’, both of which can produce NADPH, suggesting that mutant chondrocytes try to compensate, albeit unsuccessfully, for the reduced NADPH generation by the PPP (Fig. 3c and Extended Data Fig. 6f).

a, t-SNE visualization of cell populations in P3 growth plates from G6pdhchon+ and G6pdhchon− mice (n = 2). b, t-SNE plots, colour-coded for G6pdhchon+ (grey) and G6pdhchon− (khaki) samples. Arrowheads indicate phenotypic differences between genotypes. c, Top ten upregulated and downregulated KEGG pathways obtained from GSEA in G6pdhchon− versus G6pdhchon+. Gly, glycine; Ser, serine; Thr, threonine; HIF, hypoxia-inducible factor; cGMP, cyclic guanosine monophosphate; PKG, protein kinase G; ECM, extracellular matrix; NES, normalized enrichment score.

G6PDH-generated NADPH regulates oxidative protein folding

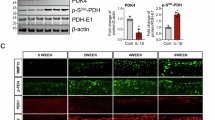

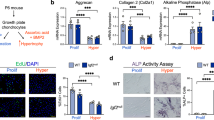

Given that GSEA suggests a progressive, differentiation-related malfunctioning in G6pdhchon− growth plates, we first focused on understanding the link between NADPH-mediated GSSG recycling and protein processing in ER, as this pathway was most increased in the resting chondrocytes (Extended Data Fig. 6c). The ER mediates oxidative protein folding, necessary for correct protein functioning, and the formation of disulfide bridges is mainly catalysed by PDI, encoded by P4hb, which functions as an electron acceptor and transfers the electrons indirectly to oxygen, resulting in H2O2 production10. Thus, along with the mitochondria, the ER is an important source of ROS production. To investigate the link between NADPH-mediated GSSG recycling and ER protein processing, we first investigated whether oxidative protein folding varies with the differentiation stage of chondrocytes. Using a tetraphenylethene maleimide (TPE-MI) probe, we observed higher levels of free cysteine thiols in proliferating than in differentiating chondrocytes, suggesting that oxidative protein folding increases during differentiation (Extended Data Fig. 7a–c). Indeed, pseudotime analysis of G6pdhchon+ chondrocytes showed an increase in the expression of the KEGG gene sets for ‘protein folding’ and ‘protein processing in ER’ during chondrocyte differentiation (Extended Data Fig. 7d). We then compared free cysteine thiol levels between WT and mutant chondrocytes and observed no difference between the two genotypes during proliferation, but free cysteine thiols were increased in G6PDH-null chondrocytes compared to WT chondrocytes during differentiation, suggesting decreased oxidative protein folding (Fig. 4a and Extended Data Fig. 7c). This decrease in disulfide formation can be ascribed to the reduction in total PDI protein levels and in the ratio of oxidized versus reduced PDI that we observed in differentiating hypoxic mutant chondrocytes (Fig. 4b,c). In addition, P4hb gene expression in mutant growth plates was decreased without a compensatory increase in other ER-resident oxidoreductases or PDI isoforms (Extended Data Fig. 7e). These data indicate that mutant chondrocytes reduce ER oxidative protein folding to avoid excessive ROS production, which can cause oxidative protein damage. Consistent with this idea, protein carbonylation, considered the hallmark for oxidative protein damage and detected using 1,3-dinitrophenol (DNP) flow cytometry, was not increased in G6PDH-null chondrocytes, indicating no manifest increase in oxidative protein damage (Fig. 4d and Extended Data Fig. 7f,g).

a, Free cysteine thiols measured by TPE-MI flow cytometry in differentiated hypoxic chondrocytes from G6pdhchon+ and G6pdhchon− mice (n = 3; unpaired two-sided Student’s t-test vs G6pdhchon+). b,c, PDI protein levels in reducing (***: P = 0.0002; unpaired two-sided Student’s t-test vs G6pdhchon+) (b) and non-reducing (*: P = 0.01; unpaired two-sided Student’s t-test vs G6pdhchon+) (c) conditions with β-actin as a loading control, in differentiated hypoxic chondrocytes from G6pdhchon+ and G6pdhchon− mice. Representative images from three independent experiments are shown. d, Protein carbonyl groups, measured by DNP flow cytometry, in differentiated hypoxic chondrocytes from G6pdhchon+ and G6pdhchon− mice (n = 3; unpaired two-sided Student’s t-test vs G6pdhchon+). e, Protein ubiquitination levels (left) with Ponceau S (right) as a loading control in differentiated hypoxic chondrocytes from G6pdhchon+ and G6pdhchon− mice. Representative images from six independent experiments are shown. f, mRNA levels of genes involved in endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation (ERAD: Edem1 (**: P = 0.001), Edem2, Man1a, Man1a2 (*: P = 0.048), Herpud1 (*: P = 0.01) or proteasomal degradation (PD: Vcp, Ufd1) or lysosomal degradation (LD: Lamp1 (*: P = 0.04), Lamp2 (*: P = 0.02), Ctsd (**: P = 0.004), Scarb2 (**: P = 0.005), Hexa (*: P = 0.04)) in G6pdhchon+ and G6pdhchon− growth plates (G6pdhchon+, n = 9; G6pdhchon−, n = 6; unpaired two-sided Student’s t-test vs G6pdhchon+). g, Trypsin-like, chymotrypsin-like and caspase-like proteasome activity in G6pdhchon+ and G6pdhchon− growth plates (n = 6; unpaired two-sided Student’s t-test vs G6pdhchon+). h, Relative lysosome abundance, measured by LysoTracker flow cytometry in differentiated hypoxic chondrocytes from G6pdhchon+ and G6pdhchon− mice (n = 5; unpaired two-sided Student’s t-test vs G6pdhchon+). i,j, Dead cells, measured by SYTOX Green flow cytometry in differentiated hypoxic chondrocytes from G6pdhchon+ and G6pdhchon− mice after overnight treatment with 10 µM MG132 (proteasome inhibitor) (i) or 5 µM chloroquine (CQ; lysosomal inhibitor) (j) (n = 6; two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test). k,l, Activation of unfolded protein response as evidenced by ATF4 immunostaining (k; n = 8) and Ddit3 (CHOP) gene expression (l) on G6pdhchon+ and G6pdhchon− growth plates (G6pdhchon+, n = 9; G6pdhchon−, n = 6; unpaired two-sided Student’s t-test vs G6pdhchon+). Scale bar, 100 µm. m, Protein synthesis, measured by O-propargyl-puromycin (OPP) flow cytometry, in differentiated hypoxic chondrocytes from G6pdhchon+ and G6pdhchon− mice (n = 3; unpaired two-sided Student’s t-test vs G6pdhchon+). n, Schematic representation of the role of G6PDH in oxidative protein folding. The data are presented as means ± s.d.

Taken together, these data show that G6PDH deletion decreases NADPH levels, resulting in impaired GSSG recycling. This defect reduces oxidative protein folding during chondrocyte differentiation by decreasing the levels and reoxidation of PDI, which is necessary for optimal disulfide bridge formation (Fig. 4n). We speculate that this decrease in oxidative protein folding precludes excessive ROS load in the ER but at the expense of increased unfolded protein levels.

PPP-generated NADPH controls ER proteostasis

Accumulation of unfolded and misfolded proteins will lead to ER stress, which triggers a series of defence mechanisms including increased protein degradation and activation of the UPR. Unfolded proteins in the ER can become ubiquitinated to target them for proteasomal degradation, a process called ER-associated degradation22. The scRNA-seq data showed that this pathway was highly increased in differentiating chondrocytes in the G6pdhchon− growth plates (Extended Data Fig. 6d). Accordingly, we found increased expression of several genes involved with ER-associated degradation, such as Edem1, Man1a2 and Herpud1, in mutant growth plates as well as enhanced protein ubiquitination in G6PDH-deficient in vitro differentiated hypoxic chondrocytes (Fig. 4e,f). In addition, trypsin-like and chymotrypsin-like proteasome activities were increased in growth plates and in cultured differentiated hypoxic chondrocytes isolated from G6pdhchon− mice (Fig. 4g and Extended Data Fig. 7h). A second protein degradation mechanism is the clearing of unfolded proteins through lysosomal degradation. We detected increased expression of genes involved in lysosomal degradation, such as Lamp1, Ctsd and Scarb2, in G6pdhchon− growth plates (Fig. 4f) and an increase in lysosomes in G6PDH-deficient in vitro differentiated hypoxic chondrocytes, by using LysoTracker flow cytometry (Fig. 4h and Extended Data Fig. 7i,j). These findings indicate that G6PDH-deficient chondrocytes upregulate proteasomal and lysosomal degradation to cope with the increased load of unfolded proteins and prevent a further rise in cell death (Fig. 2i). Consistent with this hypothesis, adding the proteasome inhibitor MG132 or the lysosome inhibitor chloroquine enhanced cell death manifestly in G6PDH-null chondrocytes but only minimally in WT chondrocytes (Fig. 4i,j). In addition to protein degradation, cells also cope with ER stress by activating the UPR. We found that BiP gene expression (Hspa5) was increased in G6pdhchon− growth plates, which was accompanied by an increase in eIF2α phosphorylation, ATF4 protein expression and CHOP (Ddit3) gene expression, indicative of the activation of protein kinase-like ER kinase (PERK)-mediated UPR (Fig. 4k,l and Extended Data Fig. 7k–m). In addition, protein synthesis was decreased in G6PDH-deficient in vitro differentiated hypoxic chondrocytes, probably mediated by eIF2α signalling to reduce protein load (Fig. 4m and Extended Data Fig. 7n). Of note, ATF6 cleavage and Xbp1 splicing were not altered upon G6PDH deficiency, indicating that ATF6-mediated or IRE1α-mediated UPR were not activated (Extended Data Fig. 7l,m). Together, these data show that increased levels of unfolded proteins in G6PDH-deficient chondrocytes stimulate proteasomal and lysosomal degradation and activate the PERK-mediated UPR.

In conclusion, NADPH generated by the PPP is crucial for PDI-mediated disulfide bridge formation, protein folding and ER proteostasis during chondrocyte differentiation. Chondrocytes respond to G6PDH deletion by reducing protein load through UPR activation and by increasing protein degradation to minimize ER stress-induced chondrocyte cell death (Fig. 4n).

G6PDH activity assures collagen properties

Chondrocyte differentiation is characterized by the production of a collagenous matrix that later serves as a template for bone matrix formation by the osteoblasts during the process of endochondral ossification23. PDI is a key enzyme in disulfide bridge formation and is also a component of the enzyme prolyl 4-hydroxylase, which hydroxylates proline residues in collagen, necessary for the assembly and stability of the triple helix of collagen type 2 (ref. 24). Therefore, we reasoned that a decrease in PDI levels could negatively affect collagen hydroxylation and matrix properties. Hydroxyproline levels were decreased in G6PDH-deficient in vitro differentiated hypoxic chondrocytes (Fig. 5a). In addition, the matrix of G6pdhchon− growth plates was less resistant to degradation by matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9) and MMP13 (Fig. 5b,c), indicating reduced collagen cross-linking. Consistent with this idea, Safranin O staining showed a decrease in cartilage remnants in the primary spongiosa of mutant mice, indicating that removal of the mutant cartilage matrix was facilitated (Fig. 5d).

a, Hydroxyproline (OH-proline) levels in differentiated hypoxic chondrocytes from G6pdhchon+ and G6pdhchon− mice (G6pdhchon+, n = 6; G6pdhchon−, n = 5; unpaired two-sided Student’s t-test vs G6pdhchon+). b,c, OH-proline content released in supernatant or remaining in neonatal growth plates (GP) from G6pdhchon+ and G6pdhchon− mice after incubation with MMP9 (b) or MMP13 (c) (n = 4; unpaired two-sided Student’s t-test vs G6pdhchon+). d, Safranin O (SafO) staining of the primary spongiosa of neonatal G6pdhchon+ and G6pdhchon− mice with the quantification of SafO-positive area (n = 4, *: P = 0.02, unpaired two-sided Student’s t-test vs G6pdhchon+). Scale bar, 100 µm. The data are presented as means ± s.d.

Taken together, these data indicate that downregulation of PDI activity as a response to G6PDH deficiency negatively affects collagen matrix properties of long bone growth plates.

Chondrocytic G6PDH prevents ferroptosis

The third most highly upregulated pathway in G6pdhchon− growth plates, especially in hypertrophic chondrocytes, was ferroptosis (Fig. 3c and Extended Data Fig. 6e). This iron-dependent type of cell death is caused by excessive lipid peroxidation and is often initiated at the ER25. An important enzyme in preventing ferroptosis is glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4), which relies on GSH to neutralize lipid hydroperoxides formed through the reaction of polyunsaturated fatty acids with ROS. We therefore reasoned that the decrease in GSSG recycling upon G6PDH deletion negatively impacted GPX4 functioning, which, together with the increased ROS levels, induced ferroptosis. Indeed, we detected increased lipid peroxidation in mutant growth plates, measured by its byproduct, 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) (Fig. 6a) and by oxidized BODIPY C11 flow cytometry (Fig. 6b and Extended Data Fig. 8a–c). Using the BODIPY C11 assay, we observed that hypoxia increased lipid peroxidation in cultured proliferating and differentiating chondrocytes of both genotypes, but the most pronounced increase was observed in G6PDH-null differentiating hypoxic chondrocytes, which display the highest ROS levels (Extended Data Figs. 8c and 5o). In addition, Ptgs2 expression, a marker gene of ferroptosis onset, was upregulated in G6pdhchon− growth plates (Fig. 6c), which can thus contribute to the decreased cell viability in G6PDH mutant chondrocytes (Fig. 2h,i and Extended Data Fig. 5c). Of note, the expression of genes involved in iron uptake and processing (Tfrc, Steap3, Slc11a2) or the activation of polyunsaturated fatty acids (Lpcat, Acsl4) was not changed in G6pdhchon− growth plates, largely excluding these pathways as inducers of ferroptosis in our model (Fig. 6c). Taken together, these data show that G6PDH deficiency in growth plate chondrocytes results in increased lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis (Fig. 6d).

a, Lipid peroxidation measured by 4-HNE levels in G6pdhchon+ and G6pdhchon− growth plates (n = 3; unpaired two-sided Student’s t-test vs G6pdhchon+). b, Lipid peroxidation measured as oxidized BODIPY (oxBODIPY) C11 flow cytometry in G6pdhchon+ and G6pdhchon− growth plates (in vivo, n = 6; unpaired two-sided Student’s t-test vs G6pdhchon+) or differentiated hypoxic chondrocytes (in vitro, n = 3; unpaired two-sided Student’s t-test vs G6pdhchon+). c, Gpx4, Gss, Gsr, Tfrc, Steap3, Slc11a2, Lpcat Acsl4 and Ptgs2 (*: P = 0.03) mRNA levels in G6pdhchon+ and G6pdhchon− growth plates (G6pdhchon+, n = 9; G6pdhchon−, n = 6; unpaired two-sided Student’s t-test vs G6pdhchon+). d, Schematic representation of the role of G6PDH in ferroptosis prevention. GPX4, glutathione peroxidase 4; PUFA-PL, polyunsaturated fatty acid-containing phospholipids. The data are presented as means ± s.d.

Increased ROS levels not only damage proteins and membrane lipids but can also damage DNA, leading to cell death. However, we did not observe a difference in DNA oxidation between WT and mutant mice, as evidenced by deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) immunohistochemistry (Extended Data Fig. 8d), indicating that DNA is not affected by the decrease in GSSG recycling in G6PDH-deficient chondrocytes.

Bypassing GSSG recycling restores proteostasis

Collectively, our data show that G6PDH deletion in growth plate chondrocytes decreases NADPH levels and the GSH:GSSG ratio, resulting in increased ROS levels, altered proteostasis and increased lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis. Given the central role of impaired GSSG recycling in our hypothesis, we explored whether bypassing the need for GSSG recycling could prevent the observed phenotype. To this end, we supplemented cultured chondrocytes with either reduced glutathione ethyl ester (GSEE), a cell-permeable form of GSH, or N-acetyl-l-cysteine (NAC). Both treatments restored the increased H2O2 levels in differentiated G6PDH-null chondrocytes to WT levels (Fig. 7a and Extended Data Fig. 9a), an effect probably resulting from improved protein folding, as TPE-MI flow cytometry showed a decrease in free cysteine thiols (Fig. 7b and Extended Data Fig. 9b). In addition, this treatment normalized the increase in protein ubiquitination, trypsin-like, chymotrypsin-like and caspase-like proteasome activity as well as LysoTracker flow cytometry in mutant chondrocytes (Fig. 7c–g and Extended Data Fig. 9c–g). Finally, GSEE and NAC decreased lipid peroxidation and restored cell viability in G6PDH-deficient chondrocytes (Fig. 7h,i and Extended Data Fig. 9h,i).

a, H2O2 levels, measured by CellMeter Hydrogen Peroxide flow cytometry, in differentiated hypoxic chondrocytes from G6pdhchon+ and G6pdhchon− mice with or without cell-permeable reduced glutathione (GSEE; 1 mM) (n = 6; two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test). b, Free thiol groups, measured by TPE-MI flow cytometry, in differentiated hypoxic chondrocytes (n = 3; two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test). c Protein ubiquitination levels (left) with Ponceau S (right) as a loading control in differentiated hypoxic chondrocytes. Representative images from six independent experiments are shown. d–f, Trypsin-like (d), chymotrypsin-like (e) and caspase-like (f) proteasome activity in differentiated hypoxic chondrocytes (n = 6; two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test). g, Lysosome abundance, as measured by LysoTracker flow cytometry, in differentiated hypoxic chondrocytes (n = 6; two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test). h, Lipid peroxidation, measured as oxidized BODIPY C11 (oxBODIPY C11) in differentiated hypoxic chondrocytes (n = 6; two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test). i, Cell death, measured by SYTOX Green flow cytometry in differentiated hypoxic chondrocytes (n = 9; two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test). The data are presented as means ± s.d.

Our data show that G6PDH is crucial to providing sufficient NADPH in differentiating hypoxic growth plate chondrocytes to safeguard adequate GSSG recycling. Indeed, GSH regeneration is essential to reduce ROS levels during oxidative protein folding and prevent ferroptosis, thereby ensuring growth plate matrix properties and chondrocyte cell survival in the developing bones (Fig. 8).

Overview of the role of the PPP during chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation. Deletion of G6PDH, the rate-limiting enzyme of the oxPPP does not affect chondrocyte proliferation, as reversal of the non-oxPPP produces sufficient ribose-5-P for nucleotide synthesis. On the other hand, the oxPPP is necessary for the hypoxic differentiating chondrocytes, as the produced NADPH guarantees glutathione recycling, which in turn will scavenge ROS formed during oxidative protein folding. The PPP thus controls proteostasis and prevents ferroptosis.

Discussion

We show that in an avascular hypoxic environment, like the growth plate of long bones, NADPH fulfils a critical role in scavenging ROS generated during oxidative protein folding to preserve cell viability and tissue functioning. Chondrocytes that lack G6PDH are NADPH-insufficient and, in response to the impaired GSSG recycling and reduced protein folding, they activate the UPR and protein degradation to avoid proteotoxicity and cell death. Yet the reduced GSH:GSSG ratio and persistent oxidative stress also induce lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis. Therefore, protein production in a hypoxic environment requires adequate reducing power to recycle GSH and maintain oxidative protein folding (Fig. 8).

PPP-produced NADPH is considered to be crucial in the defence against oxidative stress, which is often induced by exogenous sources or disrupted mitochondrial activity26. We report an additional function for PPP-derived NADPH, as it is also necessary to confine ROS generated during oxidative protein folding in the ER. G6PDH deletion reduces NADPH:NADP+ and GSH:GSSG ratios and increases ROS levels, which elicits a drop in disulfide bridge formation during protein production as a protective response, leading to UPR activation and protein degradation. This defect in proteostasis can be rescued by either GSEE or NAC supplementation, further proving that PPP-derived NADPH is needed for proper GSSG recycling during oxidative protein folding. This NADPH–GSH axis probably complements the ER peroxidases GPX7 and GPX8 that use H2O2 to re-oxidize oxidoreductases, such as PDI, thereby lowering ROS levels27. Our data also reveal that maintaining NADPH–GSH homeostasis becomes indispensable when cells have a high protein production rate and need to function in a challenging hypoxic environment (Fig. 8). Indeed, ROS levels were particularly increased in differentiating G6PDH-deficient chondrocytes, probably because the oxidative protein folding load is higher at this stage than in proliferating cells. Moreover, the combination of differentiation and hypoxia induces even more oxidative stress, possibly because hypoxia induces mitochondrial ROS production and stimulates reductive carboxylation of glutamine, thereby increasing the NADPH demand28,29. Of note, oxidative protein folding is still possible in hypoxia because ERO1, which transfers electrons to oxygen, can function under low oxygen tension owing to its very low Km for oxygen30. Accordingly, cell death was most pronounced in differentiating hypoxic mutant chondrocytes. These findings indicate that microenvironmental conditions may overwhelm the NADPH capacity of protein-producing cells and elicit proteotoxicity. It would be interesting to investigate whether other protein-secreting cells, like pancreatic β cells producing insulin31 or hepatocytes secreting albumin32, depend on PPP-generated NADPH for protein folding as well and are also susceptible to proteotoxicity in hypoxia.

The activation of the UPR and the increase in proteasomal and lysosomal protein degradation in G6PDH-deficient chondrocytes did not resolve the oxidative stress, which, in turn, promoted membrane lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis. It is noteworthy that the ER is considered an initiating site of lipid peroxidation during ferroptosis, as the earliest signs of ferroptosis are observed on internal membranes, especially the ER, before lipid peroxidation is detected at the plasma membrane33. We propose that lipid peroxidation is initiated in the ER of G6PDH-null chondrocytes because of the increased oxidative load in this compartment. Indeed, the scRNA-seq analysis of the G6PDH-deficient growth plate showed a sequential stage-dependent profile, starting with an increase in protein processing and proteasome activation and followed by ferroptosis induction. This sequential pattern suggests that the different pathways are closely linked and that the impaired oxidative protein folding accompanied by increased ROS levels probably leads to lipid peroxidation of ER membranes and later to ferroptosis. Thus PPP-generated NADPH may prevent ferroptosis indirectly, by ensuring that GSH is recycled to guarantee ROS scavenging during oxidative protein folding. In addition, GSH also prevents lipid peroxidation directly because it is a cofactor of GPX4, which reduces toxic lipid hydroperoxides to less dangerous lipid alcohols25.

The reduced cell number in G6PDH-deficient growth plates is thus caused by increased cell death and not by impaired proliferation. This observation contrasts with other normal and malignant proliferative cells such as intestinal and cancer cells that display reduced proliferation upon G6PDH inactivation26. Indeed, in many proliferative cell types, the oxPPP is required to generate ribose-5-phosphate for nucleotide synthesis, whereas G6PDH-deficient chondrocytes can produce this metabolic intermediate by rewiring glucose carbon flux through the non-oxPPP (Fig. 8), highlighting the metabolic flexibility of chondrocytes.

A limitation of our study is that Col2-Cre targets growth plate chondrocytes at every stage of differentiation, which might mask some stage-specific effects. However, our data clearly show that G6PDH and the oxidative PPP are mainly important during chondrocyte differentiation in the hypoxic environment. Although rather unlikely given this observation, Col10-Cre driver mice could be used to assess the potential effects of G6PDH deletion in more mature hypertrophic chondrocytes at earlier stages of chondrocyte differentiation.

In sum, our study uncovers an important role for G6PDH-mediated PPP activity, as it protects chondrocyte integrity during bone development. We show that the PPP generates NAPDH to support GSSG recycling, which facilitates oxidative protein folding, sustains ER proteostasis and prevents ferroptosis during chondrocyte differentiation. We speculate that the NADPH-supported protein folding is important not only for chondrocyte functioning in the avascular growth plate during bone development but also in the cartilage callus during fracture repair or when therapies rely on regenerative bone strategies.

Methods

Animals

Chondrocyte-specific G6PDH-null mice were generated by crossing G6pdhfl/fl mice (harbouring exon 10 flanked by LoxP sites; kindly provided by P. Carmeliet, VIB-KU Leuven, Belgium) with transgenic mice expressing Cre recombinase under the control of the collagen type II (Col2a1) promotor34, resulting in Col2-Cre+; G6pdhfl/fl mice (which we refer to as G6pdhchon−). WT littermates (Col2-Cre−; G6pdhfl/fl; referred to as G6pdhchon+) were used as controls. Phenotyping, body weight and tibia length measurements were performed on 3-day-old male and female mice. All mice (100% C57BL/6J background) were housed and bred under conventional conditions (22 °C; 50–60% humidity; a 14 h light, 10 h dark cycle) and fed a normal chow diet. Experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Research Advisory Committee of the KU Leuven (P254/2015, P221/2017).

Cell isolation and culture

Cell isolation

Growth plate chondrocytes were isolated from the distal femur and proximal tibia of 3–6-day-old male and female mice as previously described7. In brief, after removal of the perichondrium, dissected growth plates were digested using 2 mg ml−1 collagenase type II in minimum essential medium alpha (αMEM) GLUTAMAX supplemented with 100 units per ml penicillin, 50 μg ml−1 streptomycin and 10% FBS (all from Gibco, ThermoFisher Scientific) for 3 h at 37 °C. The cell suspension was passed through a 70 µm nylon mesh, centrifuged (300g for 7 min at room temperature, 20–21 °C) and chondrocytes were seeded in DMEM (Gibco) containing 5.5 mM glucose (Sigma-Aldrich), 2 mM glutamine (Gibco), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Gibco) and supplemented with 100 units per ml penicillin, 50 μg ml−1 streptomycin and 10% FBS (hereafter referred to as ‘growth medium’) at a density of 18 × 104 cells per cm². Cells were cultured at 37 °C, 5% CO2 and 21% O2.

Chondrogenic maturation

To mimic the in vivo differentiation of growth plate chondrocytes in vitro, confluent monolayers were switched to chondrogenic differentiation medium (growth medium supplemented with 50 µg ml−1 l-ascorbic acid (Sigma-Aldrich), 10 ng ml−1 recombinant human transforming growth factor-β1 (rhTGF-β1; PeproTech) and 20 µM Y-27632 (ROCK inhibitor; Axon Medchem) and cultured at 21% or 1% O2 (Whitley H35 Hypoxystation, Laboconsult); this time point was considered differentiation day 0. The medium was refreshed daily, and all in vitro analyses were performed on day 2 or 3 of chondrogenic differentiation unless stated otherwise.

In vitro treatments

To inhibit lysosomal or proteasomal activity, cells were treated overnight, starting on day 1 of chondrogenic differentiation, with 5 µM chloroquine or 10 µM MG132, respectively (both from Sigma-Aldrich) with dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma-Aldrich) as the vehicle control. Transketolase activity was inhibited using 100 µM oxythiamine (Sigma-Aldrich) for 48 h. To rescue the increase in oxidative stress, cells were treated with 1 mM GSEE (Sigma-Aldrich) or 500 µM NAC (Sigma-Aldrich) starting on day 0 of chondrogenic differentiation until day 3.

scRNA-seq

Growth plates were isolated from the distal femur and proximal tibia of 3-day-old mice (male G6pdhchon+, n = 1; male G6pdhchon−, n = 1; female G6pdhchon+, n = 1; female G6pdhchon−, n = 1). The enzymatic digestion protocol was optimized to obtain a high yield of single cells in a short time frame; therefore, we used 5 mg ml−1 collagenase type II in αMEM GLUTAMAX supplemented with 100 units per ml penicillin, 50 μg ml−1 streptomycin and 10% FBS for 1.5 h at 37 °C (hereafter referred to as ‘high-concentration collagenase digest’). The cell suspension was passed through a 40 µm nylon mesh, centrifuged (300g for 7 min at room temperature) and resuspended in PBS supplemented with BSA. Single-cell suspensions were converted to barcoded scRNA-seq libraries using the Chromium Single Cell 3′ Reagent Kits v.3 (10× Genomics), aiming for 5,000 cells per library. Libraries were sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 and mapped to the mouse genome (build mm10) using CellRanger software (10× Genomics). The 10× CellRanger output was analysed using the BIOMEX platform35. Linear trajectory interference analysis was performed using the SCORPIUS algorithm and locally weighted smoothing regression was performed for the visualization of gene or KEGG pathway expression along the established pseudotime trajectory. These single-cell data have been deposited in the Array Express under accession code E-MTAB-14554.

Gene and protein expression analysis

Gene expression

RNA was extracted from isolated growth plates using TRIzol (ThermoFisher Scientific). In brief, growth plates were homogenized in TRIzol followed by chloroform phase separation. Next, RNA was precipitated using isopropanol, and after washing with 75% ethanol, the pellet was air-dried and resuspended in distilled water. RNA from cultured cells and other isolated tissues was extracted using the NucleoSpin RNA Isolation Kit (Macherey Nagel). mRNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA (Superscript II Reverse Transcriptase; ThermoFisher Scientific) and gene expression analysis was performed on the StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR system software v.2.3 (ThermoFisher Scientific) using specific primer sets (Supplementary Table 2). Values were normalized to Hprt expression and expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method.

Protein expression

For whole cell lysates, cultured cells were rinsed with ice-cold PBS and lysed in RIPA buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 5 mM EDTA, 1% NP40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS supplemented with PhosSTOP and cOmplete protease inhibitor cocktail; both from Roche). For whole cell lysates from growth plates, tissue was rinsed with ice-cold PBS and lysed in RIPA buffer using a Dounce homogenizer. Protein concentrations were determined with the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific).

Unless otherwise stated, proteins were separated by SDS–PAGE under reducing conditions and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. After 60 min blocking with 5% dry milk (Sigma-Aldrich) in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween-20, membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies detecting ATF4 (11815, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:1,000), ATF6 (70B1413.1, Novus Biologicals, 1:1,000), β-actin (A5441, Sigma-Aldrich, 1:10,000), eIF2a (5324, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:1,000), G6PDH (8866, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:1,000), p-eIF2a (3398, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:1,000) and ubiquitin (3936, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:1,000). Appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (anti-mouse HRP-conjugated, Dako; anti-rabbit HRP-conjugated, Dako) were used for chemiluminescent detection (Western Lightning Plus, PerkinElmer). As a loading control for ubiquitinated protein expression, nitrocellulose membranes were stained with 0.5% Ponceau S (Sigma-Aldrich) in 1% acetic acid.

To analyse reduced and oxidized PDI by western blot, cells were lysed in 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 2% SDS supplemented with PhosSTOP and cOmplete protease inhibitor cocktail and 40 mM ethylmaleimide to block free cysteines. Protein concentrations were measured and proteins were separated by SDS–PAGE under reducing or non-reducing conditions. Upon transfer, nitrocellulose membranes were blocked and incubated overnight at 4 °C with antibodies against PDI (3501, Cell Signaling Technology) or β-actin. Appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies were used for chemiluminescent detection. Images were acquired using an Odyssey XF Imaging system and LICOR software (LICORbio).

Flow cytometry

Proliferation in vivo

To study cell proliferation in vivo, 3-day-old mice were injected intraperitoneally with BrdU (150 µg g−1 body weight) or saline, used as a vehicle. After 4 h, growth plates were dissected and cells were isolated using the high-concentration collagenase digest (see ‘scRNA-seq’). Incorporated BrdU was detected using the FITC BrdU Flow kit (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Samples were analysed on the BD FACSCanto II (BD Biosciences; 488 nm blue laser at 530/30 nm emission using FACSDiva software v.6.1.3), and the percentage of BrdU-positive cells was calculated using Kaluza software v.2.1 (Beckman Coulter).

Lipid peroxidation in vivo

To study lipid peroxidation in vivo, 3-day-old mice were injected intraperitoneally with BODIPY 581/591 C11 (2 mg g−1 body weight; ThermoFisher Scientific) or saline used as a vehicle. After 4 h, growth plates were dissected and cells were isolated using high-concentration collagenase digest and resuspended in PBS. Oxidized BODIPY C11 was measured at 530/30 nm emission (excitation, 488 nm blue laser), and the mean fluorescence intensity was calculated using Kaluza software.

Lipid peroxidation in vitro

Cultured differentiating chondrocytes were incubated with 5 µM BODIPY 581/591 C11 for 30 min at 37 °C. Cells were collected for flow cytometry by high-concentration collagenase digest (15 min at 37 °C), centrifugation (250g for 5 min at room temperature) and resuspension in PBS. As a positive control, cells were treated overnight with 10 µM erastin before BODIPY 581/591 incubation. Oxidized BODIPY C11 was quantified as the mean fluorescent intensity using Kaluza software.

H2O2 measurement

Cultured differentiating chondrocytes were incubated with CellMeter Pacific Blue (AAT Bioquest) using 4 µl ml−1 culture medium for 30 min at 37 °C, whereafter they were collected for flow cytometry. As a positive control, cells were treated with 1 mM H2O2 for 60 min before CellMeter incubation. CellMeter was measured at 450/50 nm emission (excitation, 405 nm violet laser), and mean fluorescent intensity was quantified using Kaluza software.

Oxidative protein damage

To study oxidative protein damage, we measured protein carbonylation using flow cytometry. In this assay, 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH) is used for the derivatization of carbonyl groups into DNP residues, which can further be detected by anti-DNP antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich). Cultured differentiating chondrocytes were collected for flow cytometry and, after centrifugation, fixed in 100% methanol for 5 min on ice. Subsequently, samples were treated with DNPH (90448-S7150, OxyBlot Protein Oxidation Detection Kit, Sigma-Aldrich) for 45 min at room temperature. Samples were washed three times with Hank’s Buffered Salt Solution (HBSS; Gibco) supplemented with 2% FBS and incubated with rabbit anti-DNP antibody (1:100 dilution; 90451-S7150) for 60 min on ice, followed by incubation with anti-rabbit AF488 secondary antibody (1:100 dilution, A11008, ThermoFisher Scientific) at room temperature for 30 min, after which DNP fluorescence was detected using flow cytometry (488 nm blue laser at 530/30 nm emission). As a positive control, cells were treated with 1 mM H2O2 for 120 min before cell collection. The DNP mean fluorescent intensity was quantified using Kaluza software.

Detection of free cysteines

Free cysteine thiols were detected using TPE-MI36 (Sigma-Aldrich). In brief, cultured differentiating chondrocytes were incubated with 50 µM TPE-MI for 30 min at 37 °C and collected for flow cytometry. As a positive control, cells were treated with 1% β-mercaptoethanol for 60 min before TPE-MI incubation. TPE-MI fluorescence was detected using a 405 nm violet laser at 450/50 emission, and the mean fluorescent intensity was calculated using Kaluza software.

LysoTracker

Cultured differentiating chondrocytes were labelled with 50 nM LysoTracker Green DND-26 (ThermoFisher Scientific) for 30 min at 37 °C and collected for flow cytometry. As a positive control, cells were treated overnight with 10 µM chloroquine before LysoTracker incubation. LysoTracker fluorescence was detected by flow cytometry (488 nm blue laser at 530/30 nm emission), and the mean fluorescent intensity was calculated using Kaluza software.

Cell viability

Cultured differentiating chondrocytes were incubated with 100 nM of SYTOX Green nucleic acid stain (ThermoFisher Scientific) for 15 min at room temperature, collected for flow cytometry and SYTOX Green fluorescence was measured at 530/30 nm emission (excitation, 488 nm blue laser). The percentage of dead cells (SYTOX Green-positive cells) was calculated using Kaluza software.

Cell proliferation BrdU ELISA

Cell proliferation during oxythiamine treatment was measured by BrdU incorporation using the Cell Proliferation ELISA (Roche) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, isolated chondrocytes were treated with 100 µM oxythiamine the day after seeding. After 24 h, BrdU was added to the cell culture medium for 4 h, whereafter cells were fixed, DNA was denatured and anti-BrdU antibody conjugated to peroxidase was added. After adding the substrate, the colour development was measured using Synergy H1 (Biotek, Biospx) ELISA reader and Skanit for Multiskan GO v.2.0 software. The obtained values were normalized to DNA content.

Mass spectrometry-based metabolomics analysis and stable isotope tracing

To measure oxPPP and non-oxPPP activity, proliferating chondrocytes were cultured for 24 h in glucose-free DMEM supplemented with 10% dialysed FBS and 5.5 mM [1,2]-13C2-glucose (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories). For metabolite extraction from cultured cells, proliferating or differentiating chondrocytes were washed with ice-cold 0.9% NaCl and metabolites were extracted using 80% methanol supplemented with 2 µM d27 myristic acid (hereafter referred to as ‘extraction buffer’). To extract NADPH and NADP+ moieties from cultured cells, 50:30:20 (methanol:acetonitrile:Tris (20 mM, pH 9.3)) was used as an extraction buffer. For metabolite extraction from growth plates, growth plates were washed with ice-cold 0.9% NaCl and homogenized in extraction buffer using a bead beater homogenizer. Following incubation with extraction buffer, samples were centrifuged (18,000g for 15 min at 4 °C) and the supernatant was analysed using liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry performed by the VIB Metabolomics Core (Leuven, Belgium). Metabolite annotation was performed based on an in-house library, and peak areas of 6-phosphogluconate, GSH, GSSG, NADPH, NADP+ and UMP were analysed using Xcalibur software (ThermoFisher Scientific). For [1,2]-13C2-glucose tracing analysis, the percentage of isotopologues for 6-phosphogluconate and UMP was calculated based on the relative contribution of each isotopologue to the total abundance of the metabolite. In addition, correction for naturally occurring stable isotope abundances was performed using in-house-developed software at the VIB Metabolomics Core. GSH, GSSG, NADPH and NADP+ levels were corrected for protein levels or tissue weight.

Proteasome activity assay

Trypsin-like, chymotrypsin-like and caspase-like proteasome activities were measured as previously described37. In brief, cultured differentiating chondrocytes were washed with ice-cold PBS and lysed in proteasome lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 7.8, 10 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 250 mM sucrose, 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT)); isolated growth plates were washed with ice-cold PBS and lysed in proteasome lysis buffer using a Dounce homogenizer. Samples were sonicated and centrifuged (16,000g for 10 min at 4 °C). Proteasome assay buffer (lysis buffer supplemented with 2 mM ATP and 100 µM Suc-LLVY-AMC (chymotrypsin-like activity substrate; Enzo Life Sciences), 100 µM Z-ARR-AMC (trypsin-like activity substrate; Sigma-Aldrich) or 100 µM Z-LLE-AMC (caspase-like activity substrate; Sigma-Aldrich)) was added to 50 µl sample in a black-walled 96-well plate and incubated for 60 min at 37 °C. Fluorescence was measured at 360/460 excitation/emission on the Synergy H1 spectrophotometer (BioTek) using Skanit for Multiskan GO v.2.0. Measurements were corrected for protein content.

Hydroxyproline measurement

Hydroxyproline content was quantified by a colourimetric protocol as previously described4 In brief, cultured cells or growth plates were hydrolysed for 3.5 h at 135 °C in 6 N HCl. Samples were vacuum-evaporated and dissolved in demineralized water. After the addition of chloramine-T to oxidize the hydroxyproline residues, samples were supplemented with Ehrlich’s aldehyde reagent and incubated at 65 °C for chromophore development. A standard curve was made to calculate the absolute amount of hydroxyproline per sample, which was then normalized to protein content (cultured cells) or tissue weight (growth plates). To assess collagen resistance to MMP-mediated degradation, growth plates were incubated with MMP9 (0.4 ng μl−1; Bio-Techne) or MMP13 (0.2 ng μl−1; Bio-Techne) for 24 h at 37 °C before hydrolysis of the remaining tissue and supernatant.

4-HNE quantification

For quantification of 4-HNE levels in growth plates, extraction was performed according to a previously published protocol38 Growth plates were dissected and homogenized in extraction buffer (100 mM Tris pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM phenylmethyl sulfonyl fluoride supplemented with PhosSTOP and cOmplete protease inhibitor cocktail). Samples were centrifuged (13,000g for 30 min at 4 °C) and the supernatant was collected. Quantification of 4-HNE was performed on 50 µl of supernatant using the Lipid Peroxidation (4-HNE) Assay Kit (Abcam) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and absorbance was measured at 450 nm (Synergy H1 spectrophotometer Biotek; BioSpx). Measurements were corrected for tissue weight.

Histochemistry and histomorphometry

Images were taken using an Axioplan 2 microscope (Zeiss) and histomorphometry and immunomorphometry were performed using related Axiovision software (Zeiss Zen 2.5 and Zeiss Axiovision v.4.9.1).

Histomorphometric analysis was performed as previously described7 using H&E-stained sections for the quantification of growth plate area and Hoechst-stained sections for the quantification of chondrocyte cell density (two sections per mouse; ImageJ software v2.0.0, NIH-LOCI).

For immunohistochemical stainings, paraffin-embedded tibia sections were incubated overnight with primary antibodies against 8-OHdG (ab10802, Abcam, 1:500), ATF4 (11815, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:20), BrdU (proliferating cells; OBT0030, Bio-Rad, 1:500), COL2 (MAB8887, Chemicon, 1:200) and G6PDH (ab231828, Abcam, 1:500). Signal visualization was obtained with following secondary antibodies: anti-rabbit biotin-conjugated (E0432, Dako, 1:100) or anti-rat biotin-conjugated (E0468, Dako, 1:600) and amplification kit (TSA Cyanine 3 system (Akoya Biosciences) or TSA fluorescein System (Akoya Biosciences); anti-mouse FITC conjugated (F0257, Sigma-Aldrich, 1:100) or anti-goat AF546 conjugated (A21085, Invitrogen). For BrdU immunostaining, mice were injected intraperitoneally with BrdU in saline at 150 µg g−1 body weight 4 h before being killed. To detect cell death, TUNEL staining with the In situ Cell Death Detection kit (Roche) was used. In brief, sections were permeabilized for 2 min on ice with 0.1% sodium citrate containing 0.1% Triton X-100, and TUNEL reaction mixture was applied for 1 h at 37 °C. All sections were stained with Hoechst to visualize cell nuclei. Using ImageJ software, we quantified the number of cells positive for BrdU, TUNEL or ATF4 relative to the total number of chondrocytes in the different subregions of interest or in the total growth plate. The percentage of G6PDH+ cells in the growth plate was quantified using QuPath v 0.5.0 software. Given the regional differences in the expression level of G6PDH, we subdivided it into seven horizontal regions of interest, with the resting and columnar zones each split into three subregions and one region of interest for the hypertrophic zone. Triangle thresholding was applied to distinguish G6PDH6+ from G6PDH− cells and the fraction of positive cells per zone was quantified.

Statistics

Data are presented as the mean ± s.d. In all figures, n represents the number of individually phenotyped mice or the number of in vitro biological replicates. Cells and mice were randomly assigned to the different experimental groups. For each independent in vitro experiment, at least three biological replicates were used. For immunoblots, at least three independent experiments were performed and representative images are shown. No statistical methods were used to pre-determine sample sizes, but our sample sizes are similar to those reported in previous publications4,5,8. Data distribution was assumed to be normal but this was not formally tested. Data collection and analysis were not performed blind to the conditions of the experiments. Mice and data points were not excluded from the analyses. Statistical analyses (GraphPad Prism v.9 software) were performed using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-tests or two-way or three-way ANOVAs followed by a Tukey–Kramer multiple comparison test, as specified in the figure legends. Results were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Figure artwork

Figure artwork was created with BioRender.com.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Mouse scRNA-seq data generated in this study have been deposited in the ArrayExpression under accession code E-MTAB-14554. Gel source images are provided in this paper. All other data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and Supplementary Information and from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Vander Heiden, M. G. & DeBerardinis, R. J. Understanding the intersections between metabolism and cancer biology. Cell 168, 657–669 (2017).

Stegen, S. & Carmeliet, G. Metabolic regulation of skeletal cell fate and function. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 20, 399–413 (2024).

Schipani, E. et al. Hypoxia in cartilage: HIF-1α is essential for chondrocyte growth arrest and survival. Genes Dev. 15, 2865–2876 (2001).

Stegen, S. et al. HIF-1α metabolically controls collagen synthesis and modification in chondrocytes. Nature 565, 511–515 (2019).

van Gastel, N. et al. Lipid availability determines fate of skeletal progenitor cells via SOX9. Nature 579, 111–117 (2020).

Yao, Q. et al. Suppressing mitochondrial respiration is critical for hypoxia tolerance in the fetal growth plate. Dev. Cell 49, 748–763.e7 (2019).

Stegen, S. et al. De novo serine synthesis regulates chondrocyte proliferation during bone development and repair. Bone Res. 10, 14 (2022).

Stegen, S. et al. Glutamine metabolism controls chondrocyte identity and function. Dev. Cell 53, 530–544.e8 (2020).

Hosios, A. M. & Vander Heiden, M. G. The redox requirements of proliferating mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 7490–7498 (2018).

Gansemer, E. R. & Rutkowski, D. T. Pathways linking nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate production to endoplasmic reticulum protein oxidation and stress. Front. Mol. Biosci. 9, 858142 (2022).

Zhang, L. et al. Biochemical basis and metabolic interplay of redox regulation. Redox Biol. 26, 101284 (2019).

Hetz, C., Zhang, K. & Kaufman, R. J. Mechanisms, regulation and functions of the unfolded protein response. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 21, 421–438 (2020).

Wang, W. et al. Atf4 regulates chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation during endochondral ossification by activating Ihh transcription. Development 136, 4143–4153 (2009).

Kondo, S., Saito, A., Asada, R., Kanemoto, S. & Imaizumi, K. Physiological unfolded protein response regulated by OASIS family members, transmembrane bZIP transcription factors. IUBMB Life 63, 233–239 (2011).

Cameron, T. L. et al. Cartilage-specific ablation of XBP1 signaling in mouse results in a chondrodysplasia characterized by reduced chondrocyte proliferation and delayed cartilage maturation and mineralization. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 23, 661–670 (2015).

Hisanaga, S. et al. PERK-mediated translational control is required for collagen secretion in chondrocytes. Sci. Rep. 8, 773 (2018).

Lui, J. C. et al. Spatial and temporal regulation of gene expression in the mammalian growth plate. Bone 46, 1380–1390 (2010).

Leijten, J. C. et al. Gremlin 1, frizzled-related protein, and Dkk-1 are key regulators of human articular cartilage homeostasis. Arthritis Rheum. 64, 3302–3312 (2012).

Chau, M. et al. Gene expression profiling reveals similarities between the spatial architectures of postnatal articular and growth plate cartilage. PLoS ONE 9, e103061 (2014).

Mizuhashi, K., Nagata, M., Matsushita, Y., Ono, W. & Ono, N. Growth plate borderline chondrocytes behave as transient mesenchymal precursor cells. J. Bone Miner. Res. 34, 1387–1392 (2019).

Holzer, T. et al. Respiratory chain inactivation links cartilage-mediated growth retardation to mitochondrial diseases. J. Cell Biol. 218, 1853–1870 (2019).

Vembar, S. S. & Brodsky, J. L. One step at a time: endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 944–957 (2008).

Long, F. & Ornitz, D. M. Development of the endochondral skeleton. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 5, a008334 (2013).

Myllyharju, J. Prolyl 4-hydroxylases, key enzymes in the synthesis of collagens and regulation of the response to hypoxia, and their roles as treatment targets. Ann. Med. 40, 402–417 (2008).

Dixon, S. J. & Olzmann, J. A. The cell biology of ferroptosis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 25, 424–442 (2024).

TeSlaa, T., Ralser, M., Fan, J. & Rabinowitz, J. D. The pentose phosphate pathway in health and disease. Nat. Metab. 5, 1275–1289 (2023).

Shergalis, A. G., Hu, S., Bankhead, A. 3rd & Neamati, N. Role of the ERO1–PDI interaction in oxidative protein folding and disease. Pharmacol. Ther. 210, 107525 (2020).

Stegen, S. et al. HIF-1α promotes glutamine-mediated redox homeostasis and glycogen-dependent bioenergetics to support postimplantation bone cell survival. Cell Metab. 23, 265–279 (2016).

Loopmans, S., Tournaire, G., Stockmans, I., Stegen, S. & Carmeliet, G. Hypoxia rewires glucose and glutamine metabolism in different sources of skeletal stem and progenitor cells similarly, except for pyruvate. J. Bone Miner. Res. 39, 150–160 (2024).

Wang, L. & Wang, C. C. Oxidative protein folding fidelity and redoxtasis in the endoplasmic reticulum. Trends Biochem. Sci. 48, 40–52 (2023).

Cerf, M. E. Beta cell dysfunction and insulin resistance. Front. Endocrinol (Lausanne) 4, 37 (2013).

Zhou, Z., Xu, M. J. & Gao, B. Hepatocytes: a key cell type for innate immunity. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 13, 301–315 (2016).

von Krusenstiern, A. N. et al. Identification of essential sites of lipid peroxidation in ferroptosis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 19, 719–730 (2023).

Ovchinnikov, D. A., Deng, J. M., Ogunrinu, G. & Behringer, R. R. Col2a1-directed expression of Cre recombinase in differentiating chondrocytes in transgenic mice. Genesis 26, 145–146 (2000).

Taverna, F. et al. BIOMEX: an interactive workflow for (single cell) omics data interpretation and visualization. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, W385–W394 (2020).

Chen, M. Z. et al. A thiol probe for measuring unfolded protein load and proteostasis in cells. Nat. Commun. 8, 474 (2017).

Maher, P. Proteasome assay in cell lysates. Bio Protoc. 4, e1028 (2014).

Cao, J. et al. DJ-1 suppresses ferroptosis through preserving the activity of S-adenosyl homocysteine hydrolase. Nat. Commun. 11, 1251 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank J. Goveia (Unicle Biomedical Data Science) for support during scRNA-seq analysis. G.C. acknowledges funding from the Fund for Scientific Research–Flanders (FWO, G.0B3418 and G0C5120N and Large-Scale Research Infrastructure I013518N) and from KU Leuven (C24/17/077); P.C. is supported by a grant from Methusalem (Flemish government). S.S. and S.L. received funding from the FWO (S.S, senior postdoctoral fellowship; 12H5920N; S.L., PhD fellowship strategic basic research; 1S46318N).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.L. and G.C. conceptualized the study. S.L., K.R., T.v.B., K.M., I.S., N.P. and S.S. conducted the investigation. P.C. and D.L. provided resources; S.S. and G.C. obtained funding. S.L. wrote the original draft of the manuscript; S.S. and G.C. contributed to manuscript review and editing. G.C. supervised the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Metabolism thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Alfredo Giménez-Cassina, in collaboration with the Nature Metabolism team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Single-cell RNA sequencing of the neonatal growth plate.

a Diagram of cell populations in postnatal day 3 growth plates. b tSNE plots, color-coded for the expression of the indicated marker genes. Grey arrowheads indicate cells with high expression of the respective marker gene in resting (RCH), columnar (CCH), hypertrophic (HCH) and proliferating chondrocytes (PC), and in borderline cells (BC) and contaminant cells (CC). c Heatmap and schematic profile of the expression of KEGG metabolic gene sets in resting (RCH), columnar (CCH) and hypertrophic chondrocytes (HCH).

Extended Data Fig. 2 In vitro [1,2]-13C2 glucose tracing and chondrogenic differentiation.

a Quantification of the number of G6PDH-positive cells in defined regions of interest in the resting zone (RZ), columnar zone (CZ) and hypertrophic zone (HZ) of the growth plate of 3-day old mice (n = 5). b Schematic representation of labeling of pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) intermediates after [1,2]-13C2 glucose tracing. (non-)oxPPP = (non-)oxidative PPP; UMP = uridine monophosphate. c Col2a1, Col10a1, Cbfa1 and Mmp13 gene expression at day 0 (confluent culture) and after three days of chondrogenic stimulation with ascorbic acid, TGF-β1 and ROCK inhibitor of chondrocytes isolated from murine growth plates (n = 6; unpaired, two-sided Student’s t test vs day 0). The data are presented as means ± SD.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Conditional deletion of G6PDH in chondrocytes.