Abstract

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD(H)) and its phosphorylated form NADP(H) are vitamin B3-derived redox cofactors essential for numerous metabolic reactions and protein modifications. Various health conditions are associated with disturbances in NAD+ homeostasis. To restore NAD+ levels, the main biosynthetic pathways have been targeted, with nicotinamide (Nam), nicotinamide riboside (NR) and nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) being the most prominent boosters. However, while many preclinical studies have examined the effects of these precursors, a direct comparison in humans is lacking, and recent rodent research suggests that the NAD+-boosting effects of NR and NMN may depend on their microbial conversion to nicotinic acid (NA), a mechanism not yet confirmed in humans. Here we show in a randomized, open-label, placebo-controlled study in 65 healthy participants that 14 days of supplementation with NR and NMN, but not Nam, comparably increases circulatory NAD+ concentrations in healthy adults. Unlike the chronic effect, only Nam acutely and transiently affects the whole-blood NAD+ metabolome. Using ex vivo fermentation with human microbiota, we identify that NR and NMN give rise to NA and specifically enhance microbial growth and metabolism. We further demonstrate ex vivo in whole blood that NA is a potent NAD+ booster, while NMN, NR and Nam are not. Ultimately, we propose a gut-dependent model for the modes of action of the three NAD+ precursors with NR and NMN elevating circulatory NAD+ via the Preiss–Handler pathway, while rapidly absorbed Nam acutely affects NAD+ levels via the salvage pathway. Overall, these results indicate a dual effect of NR and NMN and their microbially produced metabolite NA: a sustained increase in systemic NAD+ levels and a potent modulator of gut health. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT05517122.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD(H)) and its phosphorylated form NADP(H) are vitamin B3-derived redox cofactors that have a central role in hundreds of metabolic reactions and post-translational modifications of proteins1,2,3,4,5,6. Given its essentiality, disturbances in NAD+ homeostasis, and hence, a decline in NAD+ levels, have been associated with multiple health conditions7,8,9,10. Several strategies have been deployed to replenish NAD+ levels through feeding with precursors from its three canonical biosynthetic routes: the salvage pathway from nicotinamide (Nam), the Preiss–Handler pathway from nicotinic acid (NA) and the de novo biosynthesis from the essential amino acid tryptophan, which converges on the Preiss–Handler pathway4,7,8,9,11 (Fig. 1a).

a, Schematic of the dynamics of the NAD+ biosynthesis pathways. b–h, Concentrations of NAD+ (red), degradation products (yellow), NAD+ precursors (blue) and NAAD (green) in whole blood at baseline and after 14 days of daily administration of either placebo, Nam, NR or NMN. Data are shown for NAD+ (b), MeNam (c), MeXPY (d), NR (e), NMN (f), Nam (g) and NAAD (h). Significant differential changes over 14 days compared to placebo are indicated (based on two-sided ANCOVA). i–o, Acute effect of the three NAD+ precursors on the NAD+ metabolome at visit 3 (day 1) and visit 4 (day 14). The iAUC over 4 h is shown. Data are shown for NAD+ (i), MeNam (j), MeXPY (k), NR (l), NMN (m), NAM (n) and NAAD (o). Significant differences compared to placebo are indicated for each visit (based on a two-sided mixed model for repeated measurements). For NAAD (h,o), hash symbol marks that more than 85% of concentrations were below the LLOQ (0.02 µM) in the full dataset and the analysis was performed post hoc. All data in b–o are represented as boxes ranging from the upper to the lower quartile with the median indicated; error bars represent the minimum and maximum values. The number of data points (baseline/2 weeks or visit 3/visit 4) is indicated below each treatment. 0.01 < *P < 0.05; 0.001 < **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. Panel a created using BioRender.com.

The most prominent NAD+ boosters are Nam, nicotinamide riboside (NR) and nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN), while the use of NA is limited by skin flushing and gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms at high dose4,7,11,12. Although several studies have examined the acute and chronic effects of these precursors after oral administration4,7,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24, a head-to-head comparison of their impact on NAD+ levels in humans is lacking. Moreover, the oral bioavailability of polar and charged nucleotides and nucleosides similar to NR and NMN is notoriously poor25, and recent studies in rodents suggest that a substantial part of the NAD+-boosting effect of NR and NMN is mediated via their microbial conversion to NA26,27,28,29,30. Whether such gut microbial activities have a role in these precursor modes of action in a human clinical set-up remains elusive.

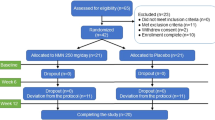

To compare the effects of the three NAD+ precursors NR, NMN and Nam versus placebo in healthy adults, a randomized, open-label, placebo-controlled four-arm study was conducted (NCT05517122; Extended Data Fig. 1). The primary endpoint of the study was the change in the whole-blood baseline level of NAD+ after 14 days of once-daily dosing. The acute (in the 4-h period after supplementation) and chronic (from baseline on day 1 to baseline on day 14) effects on the NAD+ metabolome in whole blood were secondary endpoints. The NAD+ metabolomes in plasma and urine were exploratory endpoints. Additional exploratory endpoints included targeted and untargeted metabolomics in plasma and urine, respectively.

A total of 67 participants were enrolled in the study and randomized to receive a daily dose of an NAD+ precursor, NR (1 g d−1, 3.4 mmol d−1, n = 17), NMN (1 g d−1, 3 mmol d−1, n = 15) or Nam (0.5 g d−1, 4.1 mmol d−1, n = 17), or placebo (n = 18) for 14 days (Extended Data Fig. 2; CONSORT diagram). However, two individuals received the wrong test product throughout the entire study period (one in the placebo arm and one in the NR arm), and the modified intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis (n = 65) excluded these two individuals. All data reported below correspond to the modified ITT population who received the correct NAD+ precursor, NR (n = 16), NMN (n = 15) or Nam (n = 17), or placebo (n = 17). The baseline demographic characteristics of the participants are summarized in Extended Data Table 1. The mean age of the participants was 34.7 ± 7.4 years (32 males and 33 females) with a mean body mass index (BMI) of 21.4 ± 1.8 kg m−2 for females and 23.7 ± 1.8 kg m−2 for males.

The three NAD+ precursors were well tolerated. Only three adverse events with a probable relation to the product occurred during the study; out of the total 65 participants analysed, 1 participant in the placebo group reported abdominal pain, 1 in the NR group experienced hypotension and 1 in the NMN group had headache.

After 14 days, chronic administration of NR and NMN significantly increased baseline whole-blood NAD+ concentrations by ~2-fold with concentration differences of 49.4 µM (95% confidence interval (CI), 39.5–59.3 µM; P < 0.001) and 43.1 µM (95% CI, 32.7–53.4 µM, P < 0.001) compared with placebo, respectively, while Nam did not (P = 0.461) (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Table 1). Using a single analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) linear model with baseline whole-blood NAD+ level (day 1 baseline), sex, age and assigned intervention as covariates, we did not identify an effect of sex or age on the results. Further analysis of the whole-blood NAD+ metabolome revealed that NADP+, NADPH and NADH levels were not significantly changed in any of the arms (Supplementary Table 1). Similarly, Nam, NR and NMN concentrations were not significantly affected (Fig. 1e–g). However, NR and NMN supplementation over 14 days led to significantly increased Nam concentrations in plasma in the low-micromolar range (Extended Data Fig. 3). Independent of the precursor type, the concentrations of the NAD+ degradation metabolite N1-methyl-nicotinamide (MeNam) and pooled N1-methyl-4-pyridone-5-carboxamide (Me4PY) and N1-methyl-2-pyridone-5-carboxamide (Me2PY) (MeXPY) were increased in whole blood (Fig. 1c,d), plasma (Extended Data Fig. 3) and urine (Extended Data Fig. 4a). Thus, the NAD+ degradation metabolites might not be a suitable surrogate for the NAD+ status of an individual. Although the whole-blood concentrations of nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide (NAAD) were mostly below the lower limit of quantification (LLOQ; < 0.02 µM; Supplementary Table 2), when analysing the corresponding signals post hoc, we observed that baseline levels increased after 2 weeks of treatment with NR and NMN, but not with Nam (Fig. 1h). Notably, chronic NR and NMN supplementation also led to increased urine concentrations of nicotinic acid riboside (NAR) (Extended Data Fig. 4a and Supplementary Table 3). Similarly, the concentration of NA-derived nicotinuric acid (NUR) increased with these two treatments, although to a lesser extent with NMN (P = 0.127). This metabolic footprint suggests that the increase in NAD+ by NR or NMN involves the Preiss–Handler pathway.

Acute dosing of the three precursors over 4 h resulted in strikingly different effects. Nam had the most profound acute impact on the NAD+ metabolome in whole blood (Fig. 1i–o). Whole-blood Nam concentrations significantly increased compared to placebo with a maximum concentration (Cmax) around 1 hour and an incremental area under the curve (iAUC) of 105.2 µM·h (95% CI, 87.4–122.9 µM·h; P < 0.001) (Supplementary Table 4 and Extended Data Fig. 5). Simultaneously, a mild transient elevation of NAD+, NR and NMN concentrations was observed at 1 hour (Fig. 1i,l,m and Supplementary Table 4). In addition, the intake of Nam also triggered the build-up of its degradation metabolites MeNam and MeXPY in whole blood (Fig. 1j,k), and these dynamics were further reflected in plasma (Supplementary Table 5) and in urine (Extended Data Fig. 4b). This suggests that Nam is quickly absorbed, metabolized and excreted after consumption. In contrast to Nam supplementation, the low NR and NMN concentrations in whole blood ( < 2 µM) were not affected after their administration of these precursors with no change in the circulatory NAD+ metabolome over 4 h (Fig. 1i–o and Supplementary Table 4). Yet, a longer time frame (for example, 24 h) might have allowed the capture of a longer-term acute effect of these precursors ( > 4 h). These acute effects on day 1 (visit 3, Fig. 1) were also consistent with effects on day 14 (visit 4, Fig. 1; Supplementary Tables 6 and 7) with the same magnitude. Interestingly, no acute increase in the concentration of the Preiss–Handler acidic NAD+ species NA and NAR was detected in whole blood or plasma in any of our intervention arms despite an LLOQ of 0.02 µM (Supplementary Table 2). Additionally, the post hoc assessment of NAAD did not show a significant difference in iAUC between the treatments and placebo (Fig. 1o). Overall, the NAD+ levels in whole blood after chronic supplementation with NR and NMN are consistent with previous clinical studies conducted with similar dosing regimen17,23. Here, we bring additional evidence that these precursors affect NAD+ levels to a similar extent. Published literature on the effect of Nam on NAD+ levels in humans is scarce7,14, and our data provide a more comprehensive understanding of the acute metabolic impact of Nam on the NAD+ metabolome.

We further investigated whether other blood metabolites were influenced by the three NAD+ precursors. When comparing changes at baseline across the 14 days, untargeted semi-quantitative metabolomics of whole-blood samples confirmed the effect of NR and NMN on NAD+ levels (Extended Data Fig. 6). In this set-up, a significant increase in NADH signal was also detected. This discrepancy from the targeted analysis is presumably owed to the longer sample storage time ( > 10 months) and use of a different extraction buffer containing yeast extract with no preservation of the redox ratio. Thereby, a minimal reduction in NAD+ concentration could have impacted NADH (median concentration of < 1 µM). NR and NMN treatments led to a similar elevation of riboflavin 5-monophosphate (FMN), 2-methylmalonate (2-Me-malonate) and phenylacetyl glutamine (Phe-Ac-Gln) levels, with all three of these molecules possibly derived from the gut microbiota31,32. As FMN together with flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD(H2)) is involved in many redox reactions, its alteration might also represent a direct consequence of the above-normal NAD+ concentrations. Only a few significant smaller changes were observed in the Nam and placebo groups. The impact of NR and NMN on these microbial metabolites indicates that they are retained longer in the gastrointestinal lumen and that the microbiome might be a factor in modulating the effect of NR and NMN on whole-blood NAD+.

Using quantitative plasma amino acid analysis (Supplementary Data 1), additional differential chronic effects of Nam and NR supplementation compared with placebo were detected including a more sustained concentration of homocysteine and cysteine (P < 0.05). A similar trend for baseline cysteine and homocysteine concentrations was also observed for the NMN-treated group with P values of 0.065 and 0.173, respectively. Notably, a strong acute increase in homocysteine was specifically detected in response to Nam compared with placebo on day 1 and day 14 with a more than eightfold median increase in the iAUC (P < 0.005) (Supplementary Data 1). This was expected and relates to the transient effect on the methyl pool donor driven by Nam methylation17,33, which might modulate methylation patterns. Such an effect was not detected with NR nor NMN. Other acute changes relating to whole-blood amino acids, nucleotides, fatty acids and energy metabolites were largely shared among the four groups (Supplementary Fig. 1) and, thus, linked to the intake of standardized breakfast.

To evaluate a possible metabolic conversion of the salvage pathway precursors NR and Nam by the microbiome and the potential effect of the resulting metabolites on the composition and/or metabolic activities of the microbiome, an ex vivo fermentation assay (SIFR technology) was conducted by exposing faecal-derived microbiota from healthy humans (n = 6) to NR (1 g l−1) or Nam (0.5 g l−1) and comparing to a non-substrate control (NSC) over 48 h.

By assessing the extracellular NAD+ metabolome, which is assumed to be bio-accessible, we found that the human microbiota was able to metabolize NR in several ways (Fig. 2a). On the one hand, NR was rapidly cleaved to Nam, reaching a peak of 2.1 mM at 8 h before being further deamidated to NA, resulting in a significant sustained concentration of 200–400 μM over the last 24 h in the supernatant. These effects are consistent with previous stable isotope tracer experiments in rodents that demonstrated that, after oral intake, NR is primarily cleaved to Nam and deamidated to NA by the microbiome26,27,29. After 24 h, we also observed the appearance of 6-hydroxynicotinic acid, the first intermediate in the bacterial degradation of NA, reaching 4 μM at 48 h. On the other hand, NR produced a much lower transient peak of NMN reaching 6.8 μM at 2 h, with the subsequent transient appearance of NAR and nicotinic acid mononucleotide (NAMN) with peaks of 4.9 and 2.4 μM at 4 h, respectively. These effects might be attributed to the phosphorylation of NR to NMN and the deamidation of NR and NMN to NAR and NAMN, respectively. We did not detect a significant extracellular level of NAD+. Experiments using Nam resulted in the production of NA only, indicating that Nam is not converted to NR or NMN by the microbiome (Fig. 2a). While expected variations in microbiota composition were observed among the six healthy donors (Extended Data Fig. 7), NR metabolism was notably consistent across these individuals. This corroborates its potential to be used by a broad population. In summary, we show that bacterial hydrolysis and deamidation of NR eventually result in the production of NA, a key metabolite of the Preiss–Handler pathway.

a–c, The faecal-derived individual microbiome from six healthy adult donors was exposed for 48 h to NR (blue) or Nam (orange) and compared to an NSC (grey). a, Extracellular NAD+ metabolome concentrations are expressed in µM. The significance of the treatment effect is indicated (two-sided linear mixed-effects model). b, Impact of NR (blue) or Nam (orange) on gas production, total SCFAs and pH compared to NSC (grey). The significance of the treatment effect is indicated (two-sided linear mixed-effects model). c, Impact of NR or Nam on total bacterial cell counts (one-way ANOVA) and individually induced changes in E. aldensis (one-sample t test) in samples collected after 48 h of simulated colonic incubations. Significant differences between the treatments and NSC are indicated. d, Impact of NR on key fermentation parameters and extracellular NA 24 h after its addition to fermenting microbiota derived from healthy adults (n = 6), healthy older individuals (n = 10) or individuals with Crohn’s disease (CD; n = 10). Statistical differences between the treatments are indicated (two-way ANOVA). Data in a–d are expressed as mean +/− s.d. (a,b) or as boxes ranging from the upper to the lower quartile with the median indicated and the error bars representing the minimum and maximum values. 0.05 < $P < 0.1; 0.01 < *P < 0.05; 0.001 < **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; NS, not significant.

Beyond the metabolic activities of the gut microbiota on NR and Nam, we examined whether the metabolism of the microbiota itself was affected by the treatments within the same experiment. A principal-component analysis (PCA) of the fermentation parameters of pH, gas production, acetate, propionate, butyrate and branched-chain fatty acids showed a separation of the NR condition from the Nam condition and the NSC over time (Extended Data Fig. 8). Specifically, incubation with NR differentially impacted pH and by trend also gas production (P = 0.065) in comparison to Nam treatment and NSC, as shown in Fig. 2b. The strongest impact was observed in the first 8 h and in the second time window (8–24 h), while the time effects between 24 and 48 h were less pronounced (Fig. 2b). NR also significantly increased acetate and propionate concentrations over time (Supplementary Fig. 2), which was reflected in a significant increase in total short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) (Fig. 2b). These effects were accompanied by a higher total bacterial cell density when the microbiota was exposed to NR over 48 h (Fig. 2c). Notably, NR impacted the gut microbiome ex vivo. Unlike Nam, NR significantly increased the amount of Enterocloster aldensis (Fig. 2c). This effect was highly specific (no other species was significantly impacted) and consistent across the six different test individuals. This suggests that this Enterocloster species has a unique metabolic capability to use NR. Mechanistically, this metabolic boost might be linked to higher cellular NAD+ levels, which drive fermentation, and to a higher ribose content in the NR condition.

To further explore the role of NR in the gut microbiota, patients with known gut dysbiosis were enrolled and new fermentation experiments were conducted. The results among the three populations (healthy adults (n = 6), individuals with Crohn’s disease (n = 10) and healthy older donors (n = 10)) were consistent, showing a similar decrease in pH and an increase in gas and SCFAs (Fig. 2d). Moreover, under all conditions, NR led to a build-up of NA after 24 h (Fig. 2d).

Finally, we tested with the microbiota from 12 healthy older individuals whether NMN is metabolized similarly to NR. The build-up of Nam and NA was comparable with these two treatments (Extended Data Fig. 9), and both led to more growth, a similar decrease in pH, an increase in gas production and an increase in SCFA content (Extended Data Fig. 9). In contrast to NR, NMN provoked a rapid increase in the concentration of its deamidated form NAMN, which was further metabolized over 24 h. Overall, we show that, independently of the donor conditions, NR and NMN lead to metabolic adaptations of the gut microbiota, which may boost its growth. NA and SCFAs locally produced by the microbiome are both potent activators of G protein-coupled receptors such as GPR109a, GPR41 and GPR43 expressed on intestinal epithelial and immune cells. Therefore, the combined increase in NA and SCFA might uniquely contribute to enhancing the integrity of epithelial tissue, mitigating mucosal inflammation and maintaining intestinal homeostasis. Future studies determining the potential benefits of NR and NMN on the human gastrointestinal system and the microbial metabolism in both healthy populations and those with diseases are warranted.

To test our hypothesis that NA could effectively raise NAD+ levels in human whole blood, we performed a time course experiment over 7 h with whole blood from four healthy adult donors. Whole blood was incubated with NA, NAR or NAMN, belonging to the Preiss–Handler pathway, or their corresponding amidated forms, Nam, NR and NMN involved in the salvage pathway, all at equimolar concentrations of 50 µM. We found that NA increased the NAD+ signal by ~170% over time (Fig. 3a) and was concomitantly consumed (Fig. 3h). We also observed a transient increase in NAMN and a continuous increase in NAAD (Fig. 3e,f), but no change in the amidated species nor in riboses. The addition of NAR provided a similar increase in NAD+, NAMN and NAAD, and NAR was consumed over time, with a transient increase of NA. Overall, these results demonstrate that NA is an efficient precursor of NAD+ via the Preiss–Handler pathway in human blood (Fig. 3m). Although this pathway was active in whole blood, NAMN did not increase the NAD+ level. NAMN remained unchanged over time and did not affect any other metabolites measured, presumably because it is not taken up by blood cells. Remarkably, NMN and NR did not lead to an increase in NAD+ but were degraded rapidly to their building blocks (that is, Nam and pentose phosphates) within 0.5 and 1 hour, respectively (Fig. 3). Strikingly, regarding pentose phosphates, NR degradation resulted in an increase in ribose-1-phosphate, while NMN administration mainly led to a transient increase in ribose-5-phosphate, which was further processed in the non-oxidative pentose phosphate pathway to sedoheptulose-7-phosphate (Fig. 3i–l). This suggests that degradation of the two compounds depends on distinct enzymatic activities—that is, purine nucleoside phosphorylase (PNP) pathway for NR and CD38 for NMN34,35,36. Moreover, these enzyme activities might explain the different rates of degradation for the two compounds. However, whether the emerging pentose phosphates could support biosynthetic functions (for example, nucleotide biosynthesis) or feed glycolysis and energy production needs further investigation. Nam was fairly stable over time after administration, and when NR or NMN was added, it rapidly plateaued without affecting NAD+ concentrations. The potential reason for this lack of effect on NAD+ in vitro could be the cell type used or the duration and conditions of the experiment. Previously published data have shown contrasting effects of Nam on NAD+ concentrations in vitro37,38,39. Data concerning human erythrocytes are controversial. In 1957, NA was proposed to potentially be superior to Nam, especially at low concentrations40. In 1990, the phosphate concentration was observed to possibly affect preference for the substrate and pathway used for NAD+ biosynthesis41. Thus, the different conditions might explain the discrepancy between the in vivo observation with some salvage pathway activity and the in vitro experiment. In addition, the in vitro condition did not involve multiple organ compartments. Therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility that short-term deamidation of Nam to NA in the gut or base-exchange activities via CD38 (ref. 42) or BST1 (ref. 26) could have contributed to the mild increase in NAD+ after Nam administration in vivo. Yet, the possible contribution of base-exchange activities to whole-blood NAD+ concentrations needs further examination.

a, NAD+ levels. b–d, Salvage pathway metabolites NMN (b), NR (c) and Nam (d). e–h, Preiss–Handler pathway metabolites NAAD (e), NAMN (f), NAR (g) and NA (h). i, Total pool of pentose phosphates. j, Pentose phosphate pool containing ribose-1-phosphate (R1P). k, Pentose phosphate pool containing ribose-5-phosphate (R5P). l, Sedoheptulose-7-phosphate (S7P). All measurements were performed with blood from four healthy adult donors except for the starting point (0 min), which included three donors. All values in a–l are expressed as the mean ± s.d. a.u., arbitrary units. m, Qualitative representation of the impact of the NAD+ precursors on the NAD+ metabolome and pentose phosphate pathway in whole blood after 7 h. Circle size corresponds to the strength of the effect at the end of the treatment, and numbers indicate the time (in hours) of the maximum level of declining or transiently increased metabolites.

Together, these results support the notion that, in humans, the impact of NR and NMN on whole-blood NAD+ is mediated by microbially derived NA via the Preiss–Handler pathway and that NA is efficiently metabolized to NAD+.

Collectively, the clinical data combined with the ex vivo human microbiota and human whole-blood experiments led us to propose a human model where NR and NMN are retained and further metabolized in the gut by the microbiome giving rise to NA, which then boosts NAD+ levels in whole blood. In contrast, Nam is directly absorbed and metabolized, transiently increasing NAD+ levels (Fig. 4). A recently published model in rodents suggests that excess Nam might enter enterohepatic circulation to preserve NA levels30. Although we cannot exclude that enterohepatic circulation occurs as we did not assess liver metabolism or bile, we did not have an indication that this process greatly contributes to human whole-blood NAD+ in this study as baseline NAD+ concentrations were unaffected by Nam treatment.

NR and NMN elevate circulatory NAD+ levels via the Preiss–Handler pathway, while rapidly absorbed Nam acutely affects NAD+ via the salvage pathway. Bold arrow, high fast activity; intermediary arrow, intermediary sustainable activity; dashed arrow, low activity; blue bacteria in white rectangle, gut microbiota. WB, whole blood. Figure created using https://BioRender.com.

Our study had several limitations. The ex vivo stream with human whole blood could not capture the mild acute impact of Nam on the NAD+ metabolome. One reason could be that the isolated whole blood does not entirely reflect the in vivo situation, where the Nam-derived degradation metabolites may additionally affect NAD+. Although our findings support the notion that part of the NAD+-increasing effects of NR and NMN is mediated by gut-derived NA, we did not detect increased NA concentrations in the venous whole-blood samples of the study. This is presumably due to NA’s slow release, rapid uptake and subsequent metabolism to NAD+ as shown in our in vitro whole-blood experiments. To follow up on any of these microbial activities, the inclusion of stool samples is highly recommended to confirm the reaction rates for deamidation. Additionally, faecal clinical samples might also give more clarity on intestinal concentrations of the different precursors to optimize the design of fermentation experiments performed ex vivo. In addition, we cannot rule out the possibility that simultaneously released Nam might serve other organs to generate NAD+ via the salvage pathway43. While NR and NMN were shown in mouse models to acutely affect Nam and NA concentrations in the circulation, our human study did not recapitulate these effects. Possible reasons include different dosages of the precursors used and differential absorption, with the latter potentially being affected by the standardized breakfast used in the human trial. Finally, this study was performed with a healthy population, and NAD+ concentrations were raised above normal values. Further studies are needed to evaluate the consequences of restoring NAD+ to normal concentrations in a disease population. A limitation of our ex vivo fermentation study was that shallow shotgun sequencing provides limited sequencing depth. While this allows reliable taxonomic profiling of the gut microbiome, it has reduced sensitivity for detecting low-abundance taxa and does not enable functional analysis of specific genes.

In conclusion, this head-to-head comparison of three NAD+ precursors in healthy adults shows that NR and NMN are comparable in their ability to chronically increase baseline whole-blood NAD+ levels, while Nam provides only an acute transient effect. Our findings suggest that, contrary to Nam, NR and NMN are not directly absorbed in the systemic circulation but are slowly metabolized by the microbiota to NA, a very potent NAD+ precursor in whole blood. Furthermore, ex vivo fermentation with human-derived microbiota demonstrated that NR induces metabolic microbial adaptations regardless of donor conditions and, together with NMN, increases SCFA production. This suggests that the oral intake of NR and NMN and their microbially produced metabolite NA may offer dual benefits: a sustained increase in systemic NAD+ levels and enhanced gut health.

Methods

Clinical study design

A randomized, open-label, placebo-controlled, four-arm parallel group study was conducted at the Clinical Innovation Lab, Nestlé Research, Lausanne, Switzerland, from 14 July to 24 November 2022. Each group received either placebo (microcrystalline cellulose, Pure Encapsulations; daily dose of 500 mg) or one NAD+ precursor, tested at a comparable dose: Nam (Pure Encapsulations; daily dose of 500 mg, 4.1 mmol), NR (TRU NIAGEN Pro; daily dose of 1,000 mg, 3.4 mmol) or NMN (UltraHealth; daily dose of 1,000 mg, 3 mmol), administered once daily for 14 consecutive days. On day 1 and day 14, participants collected their first morning urine sample and were provided a standardized breakfast consisting of a complete nutrition drink (BOOST Plus Calories, Nestlé Health Science) to be taken at least 2 h before the first blood sampling at baseline time (T0h). Immediately after blood sampling, the placebo or one of the NAD+ precursors was orally consumed with 200 ml of water (T0). Blood samples were subsequently obtained at 1 h (h) (T1h), 2 h (T2h) and 4 h (T4h). Between T0h and T4h, all urine was collected. From day 1 to day 14, the participants daily consumed the placebo or one of the NAD+ precursors at home, at the end of or within 30 min of finishing their usual breakfast.

Study drug compliance was calculated from self-reporting. Participants were randomized before the first intake in a 1:1:1:1 ratio to one of the four arms (Nam, NR, NMN and placebo). Randomization was stratified based on sex (female/male) and age (18–35 years and 36–50 years). Calculation of the sample size was done based on published data on NAD+ concentrations21. In brief, we assumed a standard deviation of NAD+ at day 1 (pre-dose) of 5 μM and at day 14 (pre-dose) of 20 μM, to detect a difference of +23 μM in the NAD+ level in whole blood between active arms and placebo, with 80% power and a 5/3 = 1.66% ⍺ ratio. This implied having 15 participants in each active arm and 12 participants in the placebo arm. Assuming a drop-out rate of 10% in each arm, a total of 68 participants needed to be recruited to ensure that at least 60 completed the trial and could be included in the full analysis set. Extended Data Fig. 1 summarizes the study design.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) being a healthy male or female aged 18 to 50 years at enrolment and (2) having a BMI of between 18.5 and 27.0 kg m−². Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) having any chronic or acute medical condition and/or history of a significant medical condition and/or psychiatric condition; (2) the use of prescription drugs known to potentially interact with NAD+ precursors (for example, tetracycline antibiotics, anticoagulants, bile acid sequestrants) within 14 days or five half-lives (whichever was longer) before the first dose of investigational product; and (3) the use of multivitamin/multimineral supplements, NAD+ precursor supplementation (for example, nicotinic acid or niacinamide), L-tryptophan supplementation and/or any over-the-counter medication promoting ‘healthy ageing’ or ‘anti-ageing’ or ‘longevity’ up to 30 days before the first dose of investigational product. The research protocol was approved by the Commission Cantonale (VD, Switzerland) d’éthique de la recherche sur l’être humain (CER-VD, 2022-00759). The investigators obtained written informed consent from all participants. This study followed Good Clinical Practice guidelines and is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov, with identifier: NCT05517122. Data collection and analysis were performed with blinding to the conditions of the experiments.

Whole-blood NAD+ metabolome analysis by LC–MS/MS

Quantitative analysis of the NAD+ metabolome in whole blood was carried out based on a previously developed and published analytical method44. Chromatographic separation was performed on an analytical column (2.1 mm × 150 mm, 5 μm pore size, 200 Å HILICON iHILIC-Fusion), guarded by a pre-column (2.1 mm × 20 mm, 200 Å HILICON iHILIC-Fusion Guard Kit) operating at 35 °C. Compound detection was performed using a triple-quadrupole spectrometer (TSQ Altis, Thermo Scientific) operating in positive electrospray ionization mode. The mobile phase (10 mM ammonium acetate at pH 9 (A) and acetonitrile (B)) was pumped at a flow rate of 0.25 ml min−1 over a linear gradient of decreasing organic solvent, followed by re-equilibration for a total run time of 30 min. The external calibrations were extended from 0.2–150 μM to 0.2–400 μM (Nam and NAD+(P)(H)) and from 0.02–15 μM to 0.02–40 μM (NR, NMN, MeNam, MeXPY, NAAD and NA). Peak area ratio (analyte/internal standard) and concentrations were calculated with the built-in Quan Browser software for all samples. Samples were analysed as they were collected (12 series in total) to minimize NAD degradation as the trial lasted for over 6 months.

Urine NAD+ metabolome analysis by LC–MS/MS

Quantitative analysis of the NAD+ metabolome in human urine was developed and validated as follows. On the analysis day, samples were thawed at 4 °C for 1 hour. An aliquot of 50 µl was used for extraction while keeping the samples cold on ice throughout the procedure. For each aliquot, 200 µl of cold acetonitrile containing available synthetic internal standards at a concentration of 5 µM was used followed by a few seconds of agitation and 10 min of centrifugation (21,130 g) at 4 °C. After the centrifugation, the supernatant was transferred to new Eppendorf tubes and dried overnight in a vacuum centrifuge at 4 °C and 5 mbar. Dried samples were reconstituted in 50 µl of water and centrifuged for 1 min at 15,000 rpm at 4 °C, and the supernatants were transferred into glass vials for liquid chromatography followed by tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) analysis. Chromatographic separation was performed with an Acquity I-class ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) system (Waters) on an analytical column (150 mm × 2.1 mm, ACE 3 C18-PFP). The mobile phase (0.005% formic acid, 5 mM ammonium acetate, 0.12% heptafluorobutyric acid in water (A) and acetonitrile (B)) was pumped at a flow rate of 0.25 ml min−1 over a linear gradient of increasing organic solvent, followed by re-equilibration for a total run time of 14 min. Compound detection was performed using a triple-quadrupole spectrometer (Xevo TQ-S, Waters) operating in positive electrospray ionization mode. Capillary voltage was set to 3 kV, the ion source temperature was at 150 °C and the vaporizer temperature was fixed at 350 °C. Peak area ratio (analyte/internal standard) and concentrations were calculated with the built-in TargetLynx software for all samples. Urine samples were randomized using the following criteria over six analytical batches: sex, age, arm, visit and time point.

Analysis of plasma hydrosoluble vitamins by LC–MS/MS

Sample preparation was automated and performed on a Microlab Star M liquid handler (Hamilton). Briefly, samples were thawed at room temperature, vortexed and transferred to polypropylene plates containing internal standards, ascorbic acid (AsC) and DL-dithiothreitol. Samples were precipitated with 7.5% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and centrifuged at 2,500 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was then transferred and filtered onto an AcroPrep Advance 96 filter plate with a 0.2-µm membrane (Pall) before analysis. Analyses of water-soluble vitamins were performed on an Acquity I-class UPLC system (Waters) hyphenated to a Xevo TQ-XS triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer (Waters). Separations were performed on an ACE Excel column (2 μm, C18-PFP 100, × 2.1 mm) in gradient mode using solutions containing 5% acetic acid with 0.2% heptafluorobutyric acid (HFBA) in Milli-Q water (Merck, DE) and acetonitrile as mobile phases. Data were acquired using MassLynx software (Waters), and chromatographic peaks were integrated with TargetLynx (Waters). For quantification, an R script integrated into the Laboratory Information Management System (SLims) was used. Plasma samples were randomized using the following criteria over eight analytical batches: sex, age, arm, visit and time point.

Serum amino acid analysis by LC–MS/MS

The sample preparation involving a derivatization step was automated and carried out on a Microlab Star M liquid handler (Hamilton). Briefly, plasma samples were thawed at room temperature, vortexed, transferred to a polypropylene plate and precipitated with a solution containing labelled internal standards in methanol + 0.1% formic acid (FA) before being centrifuged at 2,500 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was then collected for the derivatization step in borate buffer at pH 8.8 with aminoquinolyl-N-hydroxysuccinimidyl carbamate at 55 °C for 10 min and agitated at 500 rpm. Finally, samples were diluted 50-fold with a 10 mM solution of ammonium formate and 0.1% formic acid before LC–MS/MS analysis. Amino acid analyses were performed on an Acquity I-class UPLC system (Waters) hyphenated to a Xevo TQ-XS triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer (Waters). Separations were performed on an AccQtag Ultra C18 column (1.7 μm, 2.1 ×100 mm). Data were acquired using MassLynx software (Waters), and chromatographic peaks were integrated with TargetLynx (Waters). For quantification, an R script integrated into the SLims server was used.

Untargeted metabolomics

Fifty-microlitre whole-blood samples were thawed and extracted with liquid–liquid extraction as described above. NSK-B (CIL), creatinine (n-methyl-D3) (CIL), 2-ketoisovalarate (13C5) (CIL), nicotinamide-D4 (CDN isotopes), p-cresol sulfate (D7), lactate (13C3) (CIL), choline (D9) (CIL) and a 13C-labelled yeast extract produced in house were deployed as internal standards. Different amounts of pooled extracts served as quality control samples. After drying, samples were resuspended in acetonitrile/water (70/30, v/v) before analysis by LC–high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS). The liquid chromatography system (Vanquish UHPLC, Thermo Scientific) was connected to an Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Orbitrap Fusion Lumos Tribrid, Thermo Scientific) equipped with a heated electrospray ionization source operating in negative and positive ionization mode. Separation was achieved with a HILIC analytical column (2.1 mm × 100 mm, 5 µm pore size, 200 Å, ZIC-pHILIC)45,46. Acetonitrile and water containing 10% ammonium acetate and 0.4% ammonium hydroxide served as elution buffers.

The workflow used to process and analyse untargeted metabolomics data relied on an internal automated pipeline, coded in R and developed using several open-source packages47. First, the Thermo RAW files were converted into centroided mzXML files with RawConverter (version 1.2.0.1). The mzXML files were read and processed by the pipeline using methods from the MSnbase package (version 2.12.0)48. Picking, grouping and alignment of the peaks in LC–MS spectra were performed with the xcms package (version 3.8.2)49, providing a table of metabolic features, each of which was characterized by its mass-to-charge ratio, its retention time, the area and the height of the peak across the different samples.

To identify the redundant information in the feature table, the pipeline makes use of the RAMClust algorithm (through its implementation in the RAMClustR package), which provides a method to group together features from a single compound50. The peak areas of the relevant features were normalized to isotopically labelled internal standards by means of the best-matched internal standard (B-MIS), loosely based on the B-MIS method51. For each feature, we searched in a list of 51 internal standards for the one with the most similar behaviour in the peak area of 29 pooled quality control samples at different concentrations, by means of a correlation analysis with the normalized signal (which is the ratio between the peak area of the feature and of the internal standard) and the concentration of the quality control samples. The ‘best’ internal standard was the one that maximized the linear correlation coefficient, and it was used to normalize the peak area of the feature in all samples. If, for a given feature, none of the internal standards gave an acceptable correlation (that is, if r was < 0.8 for all internal standards), the feature was excluded from further consideration.

Finally, metabolic features were annotated by matching their exact mass and their retention time to an internal list of 445 injected compounds. A putative annotation, based on the matching of exact masses to the Human Metabolome Database (HMDB)52, was also proposed for some features not been annotated with the internal library.

Ex vivo fermentation study

Systemic Intestinal Fermentation Research (SIFR) experiments were performed at Cryptobiotix to simulate the fermentation of the test products by gut microbiota derived from different donors, as recently described53. The first ex vivo fermentation experiment used faecal samples from healthy donors. The experiment comprised a three-arm study design with a control (NSC), Nam (0.5 g l−1) and NR (1 g l−1). In each arm, individual faecal samples (collected according to a procedure approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Ghent, reference number BC-09977) from six healthy human adults (20 to 50 years old with a BMI between 18 and 25 kg m−2) were exposed to the test product for a maximum of 48 h. Samples were collected at T0, T1h, T2h, T4h, T8h, T24h and T48h. The total amount of bacterial cells present in each sample was detected via flow cytometry. To do so, samples were diluted in anaerobic PBS, followed by cell staining with SYTO 16 at a final concentration of 1 µM, and counted via a BD FACSVerse flow cytometer (BD).

Microbial composition analysis was performed on 6 faecal microbiota (0 h) and 18 ex vivo incubated microbiome samples (three-study arms (NSC, NR and Nam) for 6 participants at 48 h), according to a methodology described by Van den Abbeele et al. (2023)54. Briefly, quantitative insights into treatment effects were obtained by combining relative abundances (%) from shallow shotgun sequencing (4.3 million reads per sample on average) with total cell counts from flow cytometry, allowing estimation of cell counts per ml for different taxonomic groups. DNA was extracted from bacterial pellets via the SPINeasy DNA Kit for Soil (MP Biomedicals). DNA libraries were prepared with Nextera XT, indexed, PCR amplified, purified with magnetic beads, quantified and sequenced on the Illumina NextSeq 2000 platform (2 × 150 bp). Unassembled sequencing reads were converted to relative abundances (%) using the CosmosID-HUB Microbiome Platform (app.cosmosid.com, CosmosID; accessed on 9 January 2024).

Supernatant samples for metabolite measurements were generated by centrifugation at 9,000 g and filtration via a 0.22-µm filter. Concentrations of SCFAs, acetate, propionate and butyrate were determined via gas chromatography with flame ionization detection (Trace 1300, Thermo Fisher Scientific) following diethyl ether extraction55. pH was measured using a calibrated pH electrode (Hanna Instruments, Edge HI2002). A similar experiment was conducted to assess whether NR could also have a similar effect in older individuals and patients with Crohn’s disease as in healthy donors. Faecal samples were collected from ten healthy older donors (above 65 years old and with no gastrointestinal disorders) and ten patients with Crohn’s disease (compliant with the criteria for mild-to-moderate active Crohn’s disease: PRO2 > 8 and faecal calprotectin >250 mg kg−1). An exclusion criterion for all donors was antibiotic use within the 3 months before participation in the study. NR was used as test product at a concentration of 1 g l−1, and samples were collected at T0 and T24h. Supernatants were collected and stored at –80 °C until sample analysis.

Quantitative analysis of the NAD+ metabolome in fermentation samples was performed at Nestlé Research. Classical protein precipitation was applied to the samples with the addition of available synthetic internal standards, evaporation and reconstitution of samples. Chromatographic separation was based on the chromatographic conditions of the human urine analysis. The chromatographic separation was based on ion-pairing interaction (2.1 mm × 150 mm, 1.7 µm pore size, 100 Å ACE C18-PFP analytical column). Compound detection was done by using a triple-quadrupole spectrometer (Xevo TQ-S from Waters) operating in positive electrospray ionization mode. Peak area ratio (analyte/internal standard) and concentrations were calculated with the built-in TargetLynx software.

Whole-blood cell culture

Fresh fully anonymized human whole blood with K2 EDTA as an anticoagulant (Transfusion Interrégionale CRS, Switzerland) was diluted 1:1 in RPMI medium 1640 (Life Technologies) with added glutamine (Life Technologies) and penicillin-streptomycin (Life Technologies). After overnight incubation at 37 °C and 5% CO2, 1 ml of whole-blood culture aliquots was transferred to test tubes and spiked with 1 mM Nam (Sigma), NA (Sigma), NAR (Abmole), NR (Abmole), NAMN (Sigma) or NMN (Sigma) in water, with a final concentration of 50 µM. During incubation at 37 °C and 5% CO2, 60 µL of each sample was directly harvested with liquid–liquid extraction as described above for the untargeted metabolomics, at the following time points: 0, 30, 60, 120, 180, 240, 300 and 420 min. NSK-B (CIL), creatinine (n-methyl-D3) (CIL), 2-ketoisovalarate (13C5) (CIL), nicotinamide-D4 (CDN isotopes), p-cresol sulfate (D7), lactate (13C3) (CIL), choline (D9) (CIL), NA (D4) (CDN isotopes), NR (D4) (Santa Cruz) and a 13C-labelled yeast extract produced in house served as isotopically labelled internal standards. Similarly to the untargeted metabolomics, samples were analysed with LC–HRMS after drying overnight. Data analysis was performed with Xcalibur (Thermo).

Statistics

All statistical analyses of targeted clinical measures were performed using R software (version 4.3.3). Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05. For the analyses, all randomized participants were included, except for two who received the incorrect investigational product throughout the entire study. These participants were excluded from the modified ITT population. Data points below LLOQ or above the upper limit of quantification (ULOQ) were imputed as follows. For targeted whole-blood concentrations, values below LLOQ were replaced with half of the LLOQ. For targeted plasma and urine measures outside the quantification range, the concentrations were replaced with the LLOQ or ULOQ. The assumptions of the statistical model were examined and satisfied. Logarithmic transformation of the dependent variable was performed when assumption checks indicated non-normality or heteroscedasticity.

For chronic effects, the differences in changes between day 14 baseline and day 1 baseline across all groups were estimated using a single ANCOVA linear model with the baseline metabolic levels (day 1 baseline), sex, age and assigned intervention as covariates. In the presence of outliers, a robust ANCOVA model was applied using the same set of covariates.

Moreover, the iAUC, Cmax of metabolites from baseline to 4 h for each visit and 4-h changes in urinary metabolite levels were compared between groups using an individual mixed models for repeated measurements. The R script to calculate the iAUC is provided in the Supplementary Software 1. The model included visit (day 1, day 14), baseline whole-blood metabolite levels (day 1 baseline), sex, age, assigned intervention and the interaction between assigned intervention and visit as fixed effects. Participant-level variability was modelled as a random effect to account for the correlation between repeated measures within participants.

For untargeted metabolomics in whole blood, the statistical relevance of the fold change in the levels of a given metabolite between two different time points was assessed with a Wilcoxon paired-sample tests in R. The results of these tests were benchmarked against those of linear mixed models, which included the sex and age of the participant as random effects.

For analysis of the time course data of targeted metabolomics and the key fermentative parameters in ex vivo fermentation experiments with human-derived microbiota of six healthy donors, we fitted linear mixed-effects models for each parameter using the lme package56 in R. We set treatment, time, time2 and the interaction between treatment and time and time2 as the fixed effects, and donor as the random intercepts effect. The lmerTest package was used to obtain fixed-effects P values57. All P values were corrected for multiple testing when appropriate using the Benjamini–Hochberg method.

The statistical analysis of the comparisons between bacterial cell densities and the changes in E. aldensis in fermentation experiments with microbiota from healthy adults at 48 h was assessed in GraphPad Prism 10.4.1. For bacterial density comparisons, a paired one-way ANOVA with correction for multiple testing was performed. P values were corrected for multiplicity with the Tukey test. For E. aldensis, log2-transformed fold changes in Nam- and NR-treated samples versus NSC were analysed (due to high variability in the absolute numbers at the beginning) with a paired one-sample t test. The statistical analysis of the data from the ex vivo fermentation study (gas production, SCFA, pH and NA) in healthy adults, healthy older participants and participants with Crohn’s disease was performed in GraphPad Prism 10.4.1. A two-way ANOVA with correction for multiple comparisons was performed. P values were corrected for multiplicity with the Tukey test.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Numerical source data are available alongside the article (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28694867)58. Individual patient demographic information is not publicly available because public sharing of these data was not part of the original participant informed consent. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

For area under the curve, R script including all packages used for the determination of the iAUC is provided with this paper.

References

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30 (2000).

Kanehisa, M. Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. 28, 1947–1951 (2019).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Kawashima, M. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG for taxonomy-based analysis of pathways and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D587–D592 (2023).

Migaud, M. E., Ziegler, M. & Baur, J. A. Regulation of and challenges in targeting NAD+ metabolism. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 25, 822–840 (2024).

Ferro, V. & Moco, S. NAD+ (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, oxidized form). Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 36, 292–293 (2025).

Canto, C., Menzies, K. J. & Auwerx, J. NAD+ metabolism and the control of energy homeostasis: a balancing act between mitochondria and the nucleus. Cell Metab. 22, 31–53 (2015).

Katsyuba, E., Romani, M., Hofer, D. & Auwerx, J. NAD+ homeostasis in health and disease. Nat. Metab. 2, 9–31 (2020).

Yaku, K., Okabe, K. & Nakagawa, T. NAD metabolism: implications in aging and longevity. Ageing Res. Rev. 47, 1–17 (2018).

Zapata-Perez, R., Wanders, R. J. A., van Karnebeek, C. D. M. & Houtkooper, R. H. NAD+ homeostasis in human health and disease. EMBO Mol. Med. 13, e13943 (2021).

Abdellatif, M., Sedej, S. & Kroemer, G. NAD+ metabolism in cardiac health, aging, and disease. Circulation 144, 1795–1817 (2021).

Bogan, K. L. & Brenner, C. Nicotinic acid, nicotinamide, and nicotinamide riboside: a molecular evaluation of NAD+ precursor vitamins in human nutrition. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 28, 115–130 (2008).

Alegre, G. F. S. & Pastore, G. M. NAD+ precursors nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) and nicotinamide riboside (NR): potential dietary contribution to health. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 12, 445–464 (2023).

Li, X. et al. The acute effect of different NAD+ precursors included in the combined metabolic activators. Free Radic. Biol.Med. 205, 77–89 (2023).

Takahashi, Y. et al. Nicotinamide suppresses hyperphosphatemia in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 65, 1099–1104 (2004).

Poyan Mehr, A. et al. De novo NAD+ biosynthetic impairment in acute kidney injury in humans. Nat. Med. 24, 1351–1359 (2018).

Ito, T. K. et al. A nonrandomized study of single oral supplementation within the daily tolerable upper level of nicotinamide affects blood nicotinamide and NAD+ levels in healthy subjects. Transl. Med. Aging 4, 45–54 (2020).

Conze, D., Brenner, C. & Kruger, C. L. Safety and metabolism of long-term administration of NIAGEN (nicotinamide riboside chloride) in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of healthy overweight adults. Sci. Rep. 9, 9772 (2019).

Elhassan, Y. S. et al. Nicotinamide riboside augments the aged human skeletal muscle NAD+ metabolome and induces transcriptomic and anti-inflammatory signatures. Cell Rep. 28, 1717–1728 (2019).

Berven, H. et al. NR-SAFE: a randomized, double-blind safety trial of high dose nicotinamide riboside in Parkinson’s disease. Nat. Commun. 14, 7793 (2023).

Trammell, S. A. et al. Nicotinamide riboside is uniquely and orally bioavailable in mice and humans. Nat. Commun. 7, 12948 (2016).

Airhart, S. E. et al. An open-label, non-randomized study of the pharmacokinetics of the nutritional supplement nicotinamide riboside (NR) and its effects on blood NAD+ levels in healthy volunteers. PLoS ONE 12, e0186459 (2017).

Dolopikou, C. F. et al. Acute nicotinamide riboside supplementation improves redox homeostasis and exercise performance in old individuals: a double-blind cross-over study. Eur. J. Nutr. 59, 505–515 (2020).

Pencina, K. M. et al. MIB-626, an oral formulation of a microcrystalline unique polymorph of β-nicotinamide mononucleotide, increases circulating nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide and its metabolome in middle-aged and older adults. J. Gerontol. A 78, 90–96 (2023).

Igarashi, M. et al. Chronic nicotinamide mononucleotide supplementation elevates blood nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide levels and alters muscle function in healthy older men. NPJ Aging 8, 5 (2022).

Gross, C. J. & Henderson, L. M. Digestion and absorption of NAD by the small intestine of the rat. J. Nutr. 113, 412–420 (1983).

Yaku, K. et al. BST1 regulates nicotinamide riboside metabolism via its glycohydrolase and base-exchange activities. Nat. Commun. 12, 6767 (2021).

Shats, I. et al. Bacteria boost mammalian host NAD metabolism by engaging the deamidated biosynthesis pathway. Cell Metab. 31, 564–579 (2020).

Kim, L. J. et al. Host–microbiome interactions in nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) deamidation. FEBS Lett. 597, 2196–2220 (2023).

Chellappa, K. et al. NAD precursors cycle between host tissues and the gut microbiome. Cell Metab. 34, 1947–1959 (2022).

Yaku, K. et al. Nicotinamide riboside and nicotinamide mononucleotide facilitate NAD+ synthesis via enterohepatic circulation. Sci. Adv. 11, eadr1538 (2025).

Bedani, R., Cucick, A. C. C., Albuquerque, M. A. C., LeBlanc, J. G. & Saad, S. M. I. B-group vitamins as potential prebiotic candidates: their effects on the human gut microbiome. J. Nutr. 154, 341–353 (2024).

Krautkramer, K. A., Fan, J. & Backhed, F. Gut microbial metabolites as multi-kingdom intermediates. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 19, 77–94 (2021).

Sun, W. P. et al. Comparison of the effects of nicotinic acid and nicotinamide degradation on plasma betaine and choline levels. Clin. Nutr. 36, 1136–1142 (2017).

Sauve, A. A., Munshi, C., Lee, H. C. & Schramm, V. L. The reaction mechanism for CD38. A single intermediate is responsible for cyclization, hydrolysis, and base-exchange chemistries. Biochemistry 37, 13239–13249 (1998).

Bzowska, A., Kulikowska, E. & Shugar, D. Purine nucleoside phosphorylases: properties, functions, and clinical aspects. Pharmacol. Ther. 88, 349–425 (2000).

Wielgus-Kutrowska, B., Kulikowska, E., Wierzchowski, J., Bzowska, A. & Shugar, D. Nicotinamide riboside, an unusual, non-typical, substrate of purified purine-nucleoside phosphorylases. Eur. J. Biochem. 243, 408–414 (1997).

Gaut, Z. N. & Solomon, H. M. Uptake and metabolism of nicotinic acid by human blood platelets. Effects of structure analogs and metabolic inhibitors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 201, 316–322 (1970).

Oyama, T. et al. Supplementation of nicotinic acid and its derivatives up-regulates cellular NAD+ level rather than nicotinamide derivatives in cultured normal human epidermal keratinocytes. Life 14, 413 (2024).

Dutta, T. et al. Source of nicotinamide governs its metabolic fate in cultured cells, mice, and humans. Cell Rep. 42, 112218 (2023).

Preiss, J. & Handler, P. Synthesis of diphosphopyridine nucleotide from nicotinic acid by human erythrocytes in VITRO1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 79, 1514–1515 (1957).

Micheli, V., Simmonds, H. A., Sestini, S. & Ricci, C. Importance of nicotinamide as an NAD precursor in the human erythrocyte. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 283, 40–45 (1990).

Madawala, R. et al. CD38 mediates nicotinamide mononucleotide base exchange to yield nicotinic acid mononucleotide. J. Biol. Chem. 301, 108248 (2025).

Liu, L. et al. Quantitative analysis of NAD synthesis-breakdown fluxes. Cell Metab. 27, 1067–1080 (2018).

Giner, M. P. et al. A method to monitor the NAD+ metabolome-from mechanistic to clinical applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 10598 (2021).

Elia, I. et al. Proline metabolism supports metastasis formation and could be inhibited to selectively target metastasizing cancer cells. Nat. Commun. 8, 15267 (2017).

Chaleckis, R. et al. Unexpected similarities between the Schizosaccharomyces and human blood metabolomes, and novel human metabolites. Mol. Biosyst. 10, 2538–2551 (2014).

He, L., Diedrich, J., Chu, Y.-Y. & Yates, J. R. III Extracting accurate precursor information for tandem mass spectra by RawConverter. Anal. Chem. 87, 11361–11367 (2015).

Gatto, L. & Lilley, K. S. MSnbase—an R/Bioconductor package for isobaric tagged mass spectrometry data visualization, processing and quantitation. Bioinformatics 28, 288–289 (2012).

Smith, C. A., Want, E. J., O’Maille, G., Abagyan, R. & Siuzdak, G. XCMS: processing mass spectrometry data for metabolite profiling using nonlinear peak alignment, matching, and identification. Anal. Chem. 78, 779–787 (2006).

Broeckling, C. D., Afsar, F. A., Neumann, S., Ben-Hur, A. & Prenni, J. E. RAMClust: a novel feature clustering method enables spectral-matching-based annotation for metabolomics data. Anal. Chem. 86, 6812–6817 (2014).

Boysen, A. K., Heal, K. R., Carlson, L. T. & Ingalls, A. E. Best-matched internal standard normalization in liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry metabolomics applied to environmental samples. Anal. Chem. 90, 1363–1369 (2018).

Wishart, D. S. et al. HMDB: the Human Metabolome Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, D521–D526 (2007).

Van den Abbeele, P. et al. Bridging preclinical and clinical gut microbiota research using the ex vivo SIFR technology. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1131662 (2023).

Van den Abbeele, P. et al. Low-no-calorie sweeteners exert marked compound-specific impact on the human gut microbiota ex vivo. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 74, 630–644 (2023).

Van den Abbeele, P., Deyaert, S., Albers, R., Baudot, A. & Mercenier, A. Carrot RG-I reduces interindividual differences between 24 adults through consistent effects on gut microbiota composition and function ex vivo. Nutrients 15, 2090 (2023).

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1–48 (2015).

Kuznetsova, A., Brockhoff, P. B. & Christensen, R. H. lmerTest package: tests in linear mixed effects models. J. Stat. Softw. 82, 1–26 (2017).

Christen, S. et al. Acute and chronic effect on plasma amino acid levels. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28694867 (2026).

Acknowledgements

We thank all the participants of the clinical study. In addition, we thank the Clinical Research Unit at Nestlé Research for all operational aspects of the clinical study. This particularly includes S. Oguey-Araymon for clinical coordination, C. Cottiny for laboratory management, J. Mauger and V. Cernyskov for project and data management, L. Philippe for supply management, P. Sun as lead of the Clinical Innovation Lab at Nestlé Research and A. Themis Vyllioti as medical director. Further, we thank R. Chiba for her support with the urine analysis. Finally, we thank J. Corthesy and O. Ciclet from Nestlé Research for leading and coordinating targeted analytical platforms for vitamin and amino acid measurements in plasma. We also thank the statistical support provided by J. Poppe (Cryptobiotix).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.C. conceptualized the human study. P.V.d.A. and S.N. conceptualized the ex vivo fermentation study. S.C. and J.-P.G. conceptualized the whole-blood culture study. K.R., L.G., I.B., S.C., M.-P.G. and A.F. carried out the analytical work. R.R., M.-P.G., A.F. and S.C. prepared the data for analysis. A.N. and R.R. carried out the statistical analysis. B.C., S.C., J.-P.G., S.N. and K.R. carried out the data interpretation. B.C., S.C., J.-P.G., K.R., M.-P.G. and S.N. wrote the paper. All authors reviewed the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

S.C., S.N., K.R., L.G., M.-P.G., I.B., R.R., A.F., A.N. and J.-P.G. are employees at Nestlé Research, which is part of Société des Produits Nestlé SA. B.C. is an employee of Nestlé Health Science. P.V.d.A. is an employee of Cryptobiotix SA.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Metabolism thanks Karthikeyani Chellappa, Lindsay Wu and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Yanina-Yasmin Pesch, in collaboration with the Nature Metabolism team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Clinical study design.

Scheme of the randomized, open-label, placebo-controlled four-arm study and flowchart comparing the acute and chronic effect of NR, NMN and Nam on whole blood NAD+ levels.

Extended Data Fig. 2 CONSORT diagram of the study.

A total of 67 participants were enrolled in the study and randomized, and 65 participants were included in the modified ITT analysis.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Chronic changes in the plasma NAD+ metabolome after precursor supplementation.

Raw plasma concentrations of NAD+ derived metabolites (yellow) and NAD+precursors (blue) before and after supplementation with placebo, Nam, NR or NMN for 2 weeks. Data are shown for MeNam (a), MeXPY (b), NR (c), NMN (d) and NAM (e). Boxes ranging from the upper to the lower quartile with an indication of the median and the error bars represent the minimal and maximal values. The number of data points is indicated below each treatment. Statistical significance of the differential changes compared to placebo is indicated (based on two-sided ANCOVA). * (0.05<P < 0.01), ** (0.01<P < 0.001), *** (P < 0.001). # indicates that no statistical analysis was performed as only ~25 % of the concentrations were above LLOQ (0.01 µM).

Extended Data Fig. 4 Chronic and acute effects of the NAD+ precursors on the urinary NAD+ metabolome.

Boxes ranging from the upper to the lower quartile with an indication of the median and the error bars represent the minimal and maximal values. Urine concentrations below LLOQ (Supplementary Table 2) were imputed with the LLOQ, and the number of data points is indicated below each treatment. a, Baseline concentrations of NAD+ precursors (blue), NAD+ degradation products (yellow) and NAR (green) in urine at visit 3 (V3, day 1) and at visit 4 (V4) after 14 days of daily consumption of either placebo, Nam, NR or NMN. Statistical significance of the differential changes compared to placebo is indicated (based on two-sided ANCOVA). b, Acute concentration changes of NAD+ precursors (blue), NAD+ degradation products (yellow) and NAR (green) in urine at V3 (day 1) over 4 h after consumption of either placebo, Nam, NR or NMN. Statistical significance of the differential changes compared to placebo is indicated (based on two-sided MMRM). * (0.05<P < 0.01), ** (0.01<P < 0.001), *** (P < 0.001).

Extended Data Fig. 5 Acute effect of the NAD+ precursors on the whole blood NAD level over 4 h after consumption.

a–c, Acute response of the salvage pathway precursors Nam, NR and NMN. d–e, Acute response on NAD+ and NADP + . f, Acute response on NAD+ excretion metabolites MeNam and MeXPY. All values (a–f) are expressed as mean +/- s.d. (placebo n = 17, Nam n = 17, NR n = 16, NMN n = 15).

Extended Data Fig. 6 Chronic effects of the NAD precursors assessed by untargeted semi-quantitative metabolomics in whole blood.

a, NR (n = 16) b, NMN (n = 15) c, Nam (n = 17) and d, placebo (n = 17). Increased dot sizes and fonts indicate the shared changes between Nam and NMN treatments. The grey dotted line depicts a P value cutoff of 0.05 (paired Wilcoxon test). 2-Me-malonate, 2-methyl-malonic acid; Phe-Ac-Gln, phenylacetyl glutamine; Thr, threonine; Kyn, kynurenine; Met, methionine; N-Ac-Arg, N-acetyl-arginine; N-Ac-Ala, N-acetyl-alanine; glycocholic, glycocholic acid; glycochenodeoxycholic, glycochenodeoxycholic acid; Glu-Ser, γ-glutamyl-serine; dimethyl-Arg, dimethyl-arginine; Asp, aspartate; C16:0, palmitate; FMN, flavin mononucleotide; Desamino-Tyr, Desaminotyrosine; FAD, flavin adenine dinucleotide.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Microbial community composition of the gut microbiota of six human adults.

The microbial composition from faecal samples of six healthy donors was analyzed by shallow shotgun sequencing. a, PCA over microbial composition. The blue arrows indicate the loadings. b, Individual microbial composition of gut microbiota from six human adults.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Fermentation parameters differentiate NR from the non-substrate control (NSC) and Nam conditions over time.

PCA over the fermentation parameters pH, gas production, acetate, propionate, butyrate and branched chain fatty acids (bCFA) (sum of isobutyrate, isovalerate and isocaproate). The treatments (NSC, Nam and NR) and time points are indicated. Blue arrows represent the loadings of each fermentation parameter.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Impact of NR and NMN on fermentations with faecal-derived microbiomes of 12 healthy elderly subjects ( > 70 y) over 48 h.

All values (a–b) are expressed as mean +/- s.d. a, The differential impact of NR (1 g/L, blue) and NMN (1 g/L, pink) on the extracellular NAD+ metabolome in fermentations. For NMN, 11 out of 12 concentrations were above the upper limit of quantification (ULOQ) (400 µM) at the first time point (2 h). The significance of the treatment effect is indicated (two-sided linear mixed-effects model). b, The impact of NR (1 g/L, blue) and NMN (1 g/L, pink) on key fermentation parameters in comparison to non-substrate control (NSC). The significance of the treatment effect is indicated (two-sided linear mixed-effects model). c, The effect of NR or NMN on total bacterial cell counts after 48 h. Boxes ranging from the upper to the lower quartile with an indication of the median and the error bars represent the minimal and maximal values. The significance of the treatment effect is indicated (one-way ANOVA). * (0.01<P < 0.05), ** (0.001<P < 0.01), *** (P < 0.001), ns not significant.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Tables 1–7 and Figs. 1 and 2.

Supplementary Software 1

R script including all packages used for the determination of the iAUC.

Supplementary Data 1

Acute and chronic amino acid changes in plasma and acute metabolic changes at visit 3 over 4 h analysed by untargeted whole-blood metabolomics.

Supplementary Data 2

Impact of NR (blue) and Nam (orange) on propionate, acetate and butyrate by the healthy adult’s gut microbiota, compared to a non-substrate control (NSC, grey).

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 6

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 9

Statistical source data.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Christen, S., Redeuil, K., Goulet, L. et al. The differential impact of three different NAD+ boosters on circulatory NAD and microbial metabolism in humans. Nat Metab 8, 62–73 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42255-025-01421-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42255-025-01421-8