Abstract

In the commercialization of lithium-sulfur battery, multiphase reaction-induced polysulfide shuttling and uneven dispersion have become a bottleneck that needs to be solved. Inspired by the exquisite recognition and self-adaptive mechanisms of biomolecules in nature, this study proposes a bioinspired binder strategy based on Hyaluronic acid to reconstruct the interfacial microenvironment of the cathode at the molecular level. The binder, with its rich multipolar groups and dynamic hydrogen-bonding network, effectively enhances the anchoring and adsorption of polysulfides. Meanwhile, the unique double-helix chain structure of Hyaluronic acid generates a “breathing mode” that realizes the selective capture and spatial redistribution of active materials, thereby effectively promoting the kinetic conversion and reaction reversibility of polysulfides. The high-sulfur-loading cathode (63.8 wt%) assembled based on this mechanism manifests exceptional electrochemical performance, with an initial discharge capacity of 1347.75 mAh·g⁻¹ at 0.2 C and a capacity decay rate of merely 0.1% per cycle at 3 C.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lithium–sulfur battery (LSB) is regarded as the cutting-edge of next-generation energy storage technologies due to their remarkable theoretical energy density exceeding 2600 Wh kg⁻¹ and the advantages of sulfur’s high abundance, low cost, and environmental friendliness. However, their practical application is hindered by several critical challenges, particularly the rapid capacity decay and low sulfur utilization1,2,3,4. These issues are fundamentally rooted in two interconnected problems: (i) the poor interfacial contact between insulating sulfur species (with an electronic conductivity of approximately 5 × 10⁻³⁰ S cm⁻¹) and conductive substrates; (ii) the irreversible redistribution of active materials during cycling, which leads to the destructive polysulfide shuttling effect and continuous electrode structural degradation5,6,7,8,9.

These factors jointly impede the effective pathways for electron and ion transport, resulting in a significant reduction in cycle life. Importantly, these issues exacerbate the performance limitations of LSB through mutually reinforcing decay mechanisms. Poor interfacial contact not only weakens electron transfer kinetics but also promotes sulfur particle aggregation and inhomogeneous redistribution, further reducing the reactivity of active materials. Meanwhile, the dissolution and diffusion of lithium polysulfides (LiPSs) compromise the structural integrity of the electrodes, which in turn worsens the interfacial contact. This vicious cycle underscores that synchronously stabilizing the sulfur/electrode interface and precisely regulating LiPSs behavior are key scientific challenges for achieving commercially viable high-performance LSB10,11,12,13,14.

To address these challenges, researchers have proposed various strategies, such as nanostructured electrodes to enhance interfacial contact, functional catalysts or complex host materials (like metal-organic frameworks, covalent organic frameworks, and hierarchical porous carbons) to confine polysulfides and promote their conversion, and functional interlayers or modified separators to suppress the shuttling effect15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22. Despite significant progress, these strategies often come with notable trade-offs. The synthesis of advanced catalysts and intricate nanostructures typically involves complex and costly processes that are difficult to scale up. Additionally, introducing extra functional components inevitably increases the inactive mass of the electrode, dilutes the proportion of active materials, and thereby undermines the high-energy-density advantage of LSB23,24. Therefore, developing a simple, economical, and scalable strategy to simultaneously address poor interfacial contact and the polysulfide shuttling effect without introducing parasitic components or complex processes is imperative25.

Among various strategies, binder engineering has attracted considerable attention due to its ability to synchronously regulate electrode microstructure, interfacial chemistry, and reaction kinetics without significantly increasing inactive components. Unlike traditional inert polymers (e.g., PVDF) that solely provide mechanical adhesion, multifunctional binders are designed to be chemically active, enabling them to actively participate in the entire process of polysulfide anchoring, conversion, and electrode interface stabilization. For instance, an amphiphilic polysaccharide emulsion binder (HBEA) leverages its hydrophilic–lipophilic balance to maintain excellent adhesion while utilizing abundant polar groups to effectively anchor polysulfides and significantly enhance lithium-ion diffusion coefficients26. Flame-retardant binders integrate soft and rigid segments within the polymer framework, combining flexible mechanical strength with numerous polar sites. These not only accommodate volume changes of the sulfur cathode and suppress polysulfide shuttling but also release free radicals to terminate combustion reactions, markedly improving battery safety27. Furthermore, an eco-friendly aqueous binder derived from ramie gum (RG), rich in oxygen- and nitrogen-containing functional groups, inhibits the shuttle effect while maintaining electrode integrity, demonstrating stable areal capacity and cycling performance even under high loading conditions28. These studies highlight a growing trend of endowing binders with multiple functions-adsorption, conduction, mechanical adaptation, and special protection-through molecular design, offering pathways for developing high-efficiency, stable, and safe lithium-sulfur batteries. However, most current functional binders still face several common challenges: firstly, their synthesis often involves complex multi-step reactions or intricate structural design, hindering large-scale production; secondly, although these binders excel in specific functions, they fail to achieve dynamic and reversible regulation of polysulfides during charge/discharge processes, limiting long-term cycling stability; most importantly, existing binder systems struggle to optimally balance strong polysulfide anchoring with efficient lithium-ion transport, still facing the dilemma of “anchoring without conversion” or “conducting but insufficient confinement”.

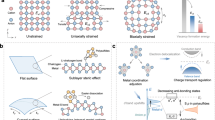

In response to these challenges, this study aims to develop a simple, economical, and scalable strategy that synchronously improves electrode interfacial contact and suppresses polysulfide shuttling without introducing redundant components or complex processes. Accordingly, we propose a bio-inspired dynamic chemical confinement strategy that fundamentally differs from conventional static physical confinement methods based on electrode/separator modifications. By incorporating hyaluronic acid (HA) as a multifunctional binder into the sulfur/carbon composite cathode system, we successfully constructed a biomimetic confinement microenvironment mimicking the extracellular matrix. The core mechanism of this strategy lies in the dynamic reconstruction characteristics of the hydrogen bond network in HA’s helical glycosidic chains during electrochemical cycling: during discharge, the exposed polar functional groups (-COOH/ -OH/ -NH₂) selectively anchor polysulfides through specific molecular recognition, while during charging, the controlled release of sulfur species is achieved through helix-coil conformational transitions, thereby establishing a unique “breathing-mode” polysulfide regulation mechanism (Fig. 1a).

Benefiting from the amphiphilic molecular structure of HA and the aforementioned dynamic confinement mechanism, this strategy not only significantly promotes the uniform spatial distribution of polysulfides but also effectively enhances the sulfur-carbon interfacial contact characteristics, thereby greatly improving interfacial charge transfer kinetics (Fig. 1b). Further systematic mechanistic studies have revealed the intrinsic reasons for the enhanced performance: the structure-activity relationship between dynamic interfacial chemical bond reconstruction and the evolution behavior of polysulfides. Notably, this strategy achieves remarkable electrochemical performance without the introduction of any auxiliary components: it exhibits an extremely low-capacity decay rate of 0.105% at a high rate of 3 C, while maintaining a reversible specific capacity of 672 mAh g⁻¹ under a high sulfur loading of 9.2 mg cm⁻². This study not only elucidates the effectiveness of the bio-inspired dynamic chemical confinement mechanism but also provides an innovative solution with scalable potential for the industrial application of lithium-sulfur battery

Results and discussion

Hydrogen bonds, though weak interactions, exert a profound influence on the aggregate state, physical properties, and structural configuration. As shown in Fig. 2a, the molecular structure of HA is rich in hydrogen bond donors (–OH, –COOH, and –NH₂). Oxygen atoms in hydroxyl and carbonyl groups, due to their high electronegativity, attract electron pairs, rendering their carbon atoms partially positively charged; while nitrogen atoms in amino groups, with their lone pair electrons, can attract and stabilize hydrogen atoms from hydrogen bond donors (Supplementary Fig. 1)29,30. Electrostatic potential (ESP) analysis (Fig. 2b) reveals that when these hydrogen bond donors interact with electronegative polysulfide anions, the uneven charge distribution enables the formation of multiple hydrogen bonds, such as C = O ∙ ∙ ∙ S, NH ∙ ∙ ∙ S, and –OH ∙ ∙ ∙ S, through electrostatic interactions, constituting the foundation of a dynamic hydrogen bond network. Compared with conventional linear PVDF, the macrocyclic topology of HA significantly reduces the system’s free energy and stabilizes the molecular framework via intramolecular conjugation among polar functional groups. This structural optimization induces the formation of a uniform and dense hydrogen bond network, laying the structural groundwork for achieving a “breathing mode” regulation of polysulfides during subsequent electrochemical cycling.

a Molecular model of HA. b Electrostatic potential and binding energy between binder and polysulfide. c FT-IR Spectra. d S 2p XPS spectra. e 1H NMR analysis probing the HA–Li2S4 interactions within a simulated battery environment (1H NMR spectra over 5 days). f Molecular dynamics simulation snapshots of the interaction between HA binder and polysulfides. g The RDF of interaction between HA binder and Li+.

Experimental characterizations confirmed the strong adsorption characteristics of this network: the HA–LiPSs complex exhibits higher binding energy (the N–H ∙ ∙ ∙ S bond reaches –1.91 eV), indicating stronger synergistic interactions. FT-IR spectroscopy (Fig. 2c) provides direct evidence for hydrogen bond formation: the inherent N–H stretching vibration peaks of HA (3400 cm⁻¹, 2900 cm⁻¹) shift to 3456 cm⁻¹ and 2951 cm⁻¹ upon adsorption of LiPSs, forming characteristic N–H–Li vibration peaks. A wavenumber difference of approximately 50 cm⁻¹ (ΔV = V(NH–Li) – V(N–H)), combined with broadened and intensified absorption peaks, indicates enhanced hydrogen bond strength and density. XPS results (Fig. 2d) reveal key electronic structure changes: after adsorption of LiPSs, the O 1 s binding energy of hydroxyl (–OH) and carbonyl (C = O) groups in HA increases significantly (ΔE = 0.3 eV), providing electronic evidence for strong electronic coupling between the oxygen-containing functional groups of HA and LiPSs. ¹H-NMR spectra (Fig. 2e) further show that the proton signals of HA continue to shift downfield with increasing immersion time, indicating a dynamically enhanced interaction. More importantly, deconvolution results demonstrate that LiPSs preferentially bind with polar groups (–OH, –COOH) at the edges of HA molecules, revealing the formation of site-selective hydrogen bonds at the interface, which is key to achieving selective “inhalation” of polysulfides.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations further elucidate the dynamic nature of the hydrogen bond network. Snapshots in Fig. 2f and Supplementary Fig. 2 show that HA polymers are bridged by hydrogen bonds to form a continuous network structure. The uniformly distributed hydrogen bond sites (–OH, C = O, –NH₂) ensure that polysulfide molecules can be effectively captured at any location. In contrast, the PVDF and CMC systems, lacking intermolecular interactions, exhibit disordered stacking and minimal hydrogen bonds (none in PVDF, Supplementary Fig. 3). Figure 2g and Supplementary Fig. 4 indicate that in the HA system, the coordination number of Li–S₄ exhibits a critical inflection point around 2, corresponding to the threshold at which the hydrogen bond effect transitions from short-range order to dynamic reconstruction. When approximately two effective hydrogen bonds exist around Li–S₄, the flexible functional groups (e.g., hydroxyls) of HA dynamically break and reform hydrogen bonds through bond angle oscillations, achieving “adaptive binding.” This dynamic behavior at the microscopic level macroscopically manifests as an intelligent “breathing mode”: during discharge, exposed polar functional groups selectively anchor (“inhale”) polysulfides via strong hydrogen bonds; during charge, controlled release (“exhalation”) of sulfur species back to the positive electrode for reaction is achieved through helix–coil conformational transitions, thereby suppressing shuttling while avoiding stress concentration and active material loss caused by rigid confinement31,32.

The origin of this high dynamism lies in the multiple proton donor and acceptor sites within the HA molecule. These sites form synergistic hydrogen bonds with the sulfur terminals of Li–S₄, maintaining interface stability through a dynamic equilibrium (Supplementary Fig. 5). As shown in Supplementary Fig. 6, sulfur center coordination number analysis reveals a characteristic inflection point in the HA system at CN(S–S) ≈ 1, indicating that dynamic hydrogen bonds preferentially anchor terminal sulfur atoms, inhibiting the disordered cross-linking of long-chain polysulfides. More critically, the radial distribution function (RDF) integral intensity of S–S pairs in the HA system is as high as 7100, which is 3.2 and 3.9 times that of the CMC (2200) and PVDF (1800) systems, respectively. This reveals that the dynamic hydrogen bond network regulates the distribution of polysulfides via an “anchor–release” mechanism (i.e., “breathing”), forming locally high-concentration enrichment layers and significantly enhancing reaction kinetics33,34,35.

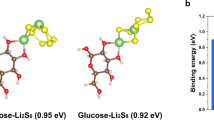

The enrichment phenomenon primarily stems from the molecular anchoring effect of HA on polysulfides and its unique “breathing mode” regulation mechanism during electrochemical cycling. DFT calculations (Fig. 3a) demonstrate that HA exhibits a significantly higher adsorption energy for Li₂S₄ (−25.0 kcal/mol) compared to conventional binders PVDF (−9.2 kcal/mol) and CMC (−16.8 kcal/mol), with its multiple polar functional groups (-OH/C = O/-NH₂) synergistically providing strong adsorption sites (ΔEads > −0.89 eV, Supplementary Fig. 7)36,37. This theoretical prediction was experimentally verified: Li₂S₄ solutions containing HA binder completely decolorized after 24 h (Fig. 3b), and showed the most significant absorbance decay at the characteristic peak of 415 nm in UV-Vis spectroscopy (Fig. 3c), visually demonstrating HA’s ability to achieve selective anchoring of polysulfides through molecular recognition.

a DFT calculations for the binding energies among diffent binder and LiPSs. b Photographs of the LiPSs adsorption experiment. c UV–vis spectrum with different samples after immersion in Li2S4 solution for 24 h. d S 2p XPS spectra for HA binder soaked with Li2S4. e Sulfur K-edge XAS of different binder electrode after exposure to polysulfide solution. f In-situ time-resolved Raman image of the S@HA cathode.

To further elucidate the atomic-level mechanism of the “breathing mode,” XPS was employed to characterize the surface structure of HA before and after Li₂S₄ adsorption. The results indicated the formation of thiosulfates and polythionates on the HA surface (Fig. 3d), confirming that the hydrogen bonding effect not only promotes adsorption but also initiates sulfur redox reactions. By comparing O 1 s, C 1 s, and N 1 s spectra (Supplementary Fig. 8), ion-dipole interactions between HA and polysulfide anions were identified, providing electronic structure evidence for the “controlled release of sulfur species through conformational transitions during charging.” Synchrotron-based X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) further revealed the hydrogen bond-mediated sulfur chemical reconstruction pathway: the S@HA electrode exhibited characteristic peaks at 2472 eV and 2477.0 eV (Fig. 3e), indicating the generation of insoluble Li₂SO₃. This product, directionally transformed under the guidance of hydrogen bonding, serves as a key component of the solid electrolyte interphase (SEI), effectively suppressing the dissolution of active materials38,39,40. MD simulations (Supplementary Fig. 9) quantitatively demonstrated that this mechanism reduces the polysulfide diffusion coefficient by 93% (DLiPSs = 3.819 × 10⁻⁹ cm²/s), providing kinetic evidence for the dynamic confinement effect of the “breathing mode.”

The inhibitory effect of the “breathing mode” on polysulfides was further corroborated by polysulfide dissolution experiments: the S@HA electrode solution exhibited the lightest color and the slowest dissolution rate (Supplementary Fig. 10), proving its ability to effectively suppress polysulfide diffusion. Most importantly, in situ Raman spectroscopy (Fig. 3f and Supplementary Fig. 11) directly captured the cyclic characteristics of the “breathing mode”: the S@HA electrode only detected S₈ characteristic peaks at the initial and final stages of charge/discharge, with no polysulfide signals during the process, indicating that the hydrogen bond network both enhances anchoring and promotes conversion. In contrast, control groups S@PVDF and S@CMC electrodes continuously showed Li₂S₈/ Li₂S₆/ Li₂S₄ peaks, confirming that traditional binders cannot achieve controlled release, leading to polysulfide accumulation and the shuttle effect.

Benefiting from abundant polar groups (–OH, C = O, –NH₂) and the resulting dynamic hydrogen-bonding network, HA compresses the HOMO–LUMO gap to 2.2 eV via dipole–dipole and hydrogen-bond interactions (Fig. 4a), which is significantly lower than that of PVDF (ΔEH-L (PVDF) ≈ 6.5 eV). This markedly enhances molecular excitation capability and reaction activity. The enhanced reactivity facilitates the formation of hydrogen bonds between HA and lithium ions, thereby demonstrating exceptional ion/electron conduction performance.

a HOMO and LUMO living model of HA. b Energy barrier of Li+ migration along the binder chain. c Calculated MSD of Li+ as a function of the simulation time. d N 1 s XPS spectra. e EIS spectra of the different binder electrodes. f CV curves tested at different scanning rates of S@HA. g GITT voltage profiles of S@HA at 0.2 mA. h Cyclic Voltametric Curve of different electrodes at a scan rate of 0.1 mV s−1.

DFT calculations (Fig. 4b) further confirm that the hydrogen-bond network formed between polar groups in HA glycosidic chains and lithium ions constructs a quasi-“ionic channel” structure, which serves as a key foundation for the ion transport function in the “breathing mode”. This structure effectively guides lithium-ion migration, reducing the diffusion energy barrier for lithium ions in the HA system to 0.54 eV, considerably lower than that in the PVDF system (0.96 eV). MD simulations (Fig. 4c) elucidate the dynamic characteristics of this process: in the S@HA system, lithium ions migrate via short-range, directional, and ordered hopping between the abundant –OH, C = O, and –NH₂ hydrogen-bond sites on the HA polymer, facilitated by the traction effect within the hydrogen-bond network. In contrast, PVDF and CMC systems exhibit disordered stacking due to lack of intermolecular interactions, resulting in disordered lithium-ion migration with low mobility and chaotic diffusion pathways.

Experimental data indicate that the lithium-ion diffusion coefficient within the hydrogen-bond network of the HA system reaches 3.264 × 10⁻⁶ cm s⁻¹, two orders of magnitude higher than those of PVDF/CMC systems. XPS results (Fig. 4d) show a decrease in the binding energy of the –C–NH₂ group from 399.9 eV to 399.5 eV, further confirming the coordination between –NH₂ and Li⁺ to form ionic channels. Moreover, the improved wettability (Supplementary Fig. 12) and reduced charge transfer impedance (Fig. 4e) of S@HA electrodes demonstrate that the hydrogen-bonding effect effectively reduces solid-liquid interfacial.

To quantify the enhancement effect of the “breathing mode” on Li⁺ diffusion and sulfur redox reaction kinetics, variable scan rate cyclic voltammetry (CV) tests (Fig. 4f and Supplementary Fig. 13) revealed that S@HA electrodes exhibit more distinct redox peaks, higher response currents, and lower polarization voltages. The apparent lithium-ion diffusion coefficient calculated using the Randles-Sevcik equation41 (Supplementary Fig. 14) confirmed that S@HA electrodes possess the fastest Li⁺ diffusion rate. Galvanostatic intermittent titration technique (GITT) measurements (Fig. 4g and Supplementary Fig. 15) further showed that S@HA electrodes have lower activation resistance and Li₂S nucleation resistance, attributable to the enhanced electrode-electrolyte interfacial interaction mediated by the hydrogen-bond network’s “breathing mode”.

These results indicate that the hydrogen-bond-based network significantly enhances the redox reactivity of sulfur in S@HA electrodes. The lower oxidation peak potential and higher reduction peak potential suggest that the “breathing mode” effectively reduces polarization during the LiPSs conversion process (Fig. 4h and Supplementary Figs. 16–17). Tafel slope analysis (Supplementary Fig. 18) confirmed that batteries based on S@HA electrodes exhibit the lowest Tafel slope during sulfur transformation. Notably, even under a high sulfur loading of 7.54 mg cm⁻² (Supplementary Fig. 19), the S@HA electrode maintains excellent sulfur utilization.

Finally, in situ X-ray diffraction (Supplementary Fig. 20) revealed a unique amorphous Li₂S deposition pathway in S@HA, resulting from the uniform nucleation induced by the hydrogen-bond network via the “breathing mode”, which effectively mitigates active site blockage caused by localized Li₂S accumulation. This amorphous deposition mode, together with the hydrogen-bond-optimized ion transport path and reduced conversion barrier, synergistically optimizes the full-cycle sulfur redox reaction (Supplementary Fig. 21), fully demonstrating the cooperative enhancement mechanism by which the hydrogen-bond network in HA glycosidic chains achieves simultaneous anchoring-conversion of polysulfides and transportation of lithium ions through the “breathing mode”.

The dynamic cross-linking characteristics of hydrogen bonds in binders can effectively mitigate the volumetric expansion stress of active materials, thereby significantly enhancing the structural integrity and interfacial stability of electrodes. LSV test (Supplementary Fig. 22) reveals that HA polymers exhibit no decomposition within the voltage range of 2-4 V (vs. Li+/Li), demonstrating excellent electrochemical stability. This stability is attributed to the stable chemical bonds and functional group structures within the HA molecules, which effectively suppress oxidative degradation at high potentials. Moreover, the polar functional groups (−OH, −COOH, −NH₂) abundant in HA can form stable coordination networks with lithium ions, significantly enhancing cross-linking density and exhibiting superior anti-swelling performance in ether-based electrolytes (Supplementary Fig. 23).

This structure also improves the compatibility with S/C composite materials. PVDF primarily relies on van der Waals forces to bind S/C particles. Its linear structure is ill-suited to accommodate the volume changes during sulfur phase transitions, leading to electrode structural degradation (Supplementary Fig. 24a–d and 25). CMC can encapsulate active materials, but its dense binding layer hinders electrolyte penetration and increases interfacial impedance (Supplementary Fig. 24e–h). In contrast, HA effectively inhibits sulfur species aggregation through multiple hydrogen bonds, promoting uniform dispersion of active materials (Supplementary Fig. 24i–l) and demonstrating dynamic self-adaptive reconfiguration capabilities under various conditions (Supplementary Fig. 26). It can also form a mechanically buffering layer with stress-dissipating functions at the current collector interface (Supplementary Fig. 27).

Mechanical property tests further corroborate these structural advantages. Macroscopically, the 180° peel test (Supplementary Fig. 28) indicates that HA possesses the highest binding strength (>2.2 N), with a gradually rising and sustained high-level curve, reflecting the synergistic effect of strong hydrogen bonds and three-dimensional network interlocking. CMC has a moderate strength (~0.788 N) but exhibits brittleness and swelling instability; PVDF has the lowest strength (~0.363 N) and poor binding capability. Nanoindentation (Supplementary Fig. 29) results reveal that HA combines moderate hardness with high resilience (Supplementary Fig. 30). Its loading-unloading curve is smooth and continuous, indicating excellent stress-dissipation and crack-propagation resistance capabilities. In contrast, PVDF has low modulus and is prone to creep; CMC has high modulus but is brittle and struggles to maintain structural integrity. These multiscale mechanical advantages enable the S@HA electrode to maintain interfacial integrity and long-term stability during cycling (Supplementary Fig. 31).

This structural stability plays a crucial role in electrode deformation processes. Quasi-in situ SEM analysis (Supplementary Fig. 32) reveals the dynamic deformation characteristics of different binder systems: In the initial discharge stage (2.3 V), all electrodes exhibit typical crack patterns and porous structures. As discharge progresses to 2.1 V, S@PVDF and S@CMC electrodes show significant surface fragmentation due to the volumetric expansion of sulfur species during lithiation. However, at deep discharge to 1.6 V, uniform deposition of Li₂S alleviates electrode surface cracks. Notably, the S@HA electrode demonstrates a unique structural evolution throughout the discharge process. As the electrochemical process advances, surface cracks gradually heal, ultimately forming a uniform and dense morphology. Observations during the charging process are even more striking: S@PVDF and S@CMC electrodes exhibit rapid crack propagation at the onset of charging, indicating irreversible structural damage caused by cyclic stress, which severely impedes lithium-ion transport. In contrast, thanks to the self-healing properties of its dynamic hydrogen bond network, the S@HA electrode not only effectively suppresses crack regeneration but also maintains the integrity of ion transport channels. This remarkable mechanical stability stems from the dual functional dissipation mechanisms of the hydrogen bond network: On one hand, it buffers the volumetric stress of active particles through dynamic polymer chain reconfiguration; on the other hand, it resists electrolyte expansion deformation through strong interfacial interactions, thereby achieving synergistic optimization of electrode structure and function.

The integrity of electrode structure further affects interfacial stability. In-situ EIS (Supplementary Figs. 33-35) reveals that during the Li₂S₈/Li₂S₆ dissolution stage (2.4–1.9 V), electrodes in PVDF and CMC systems experience a sharp increase in Rct (charge transfer impedance) due to binder swelling, while the S@HA system maintains low interfacial impedance. Particularly during the phase transition from Li₂S₈ to Li₂S₄ (around 1.9 V), this further indicates that dynamic hydrogen bonds significantly mitigate the abrupt impedance increase caused by suppressing the aggregation and volumetric deformation of active materials, fully demonstrating the pivotal role of dynamic hydrogen bonds in maintaining electrode structural stability and electrochemical interfacial integrity (Supplementary Table 1).

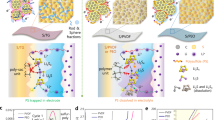

Based on the aforementioned experimental results, we have constructed schematic diagrams of the structural evolution of different binder systems in electrodes (Fig. 5a-c). During electrochemical cycling, PVDF binders tend to self-expand due to their weak intermolecular forces, causing active materials to detach from the conductive network and resulting in the degradation of electrode structural integrity and electrical contact performance. CMC binders can form rigid cross-linked networks, but their flexibility and dynamic responsiveness are insufficient to maintain electrode structural integrity during the volumetric expansion/contraction of sulfur species. In contrast, HA-based binders, with their abundant hydrogen bond networks, exhibit the following structural characteristics: 1) Efficient encapsulation of active materials and conductive agents through strong interfacial interactions; 2) Formation of a three-dimensional network structure with dynamic self-adaptive properties; 3) Good mechanical-electrochemical coupling stability of the entire electrode during charge-discharge processes. This unique molecular design not only forms a tight synergy among various components of the electrode but also significantly optimizes the electrochemical behavior of the electrode through the dynamic interfacial stabilization mechanism of the hydrogen bond network. Li₂S nucleation experiments (Fig. 5d–f) show that the S@HA electrode exhibits significantly enhanced peak current (0.39 mA) and deposition capacity (36.47 mAh·g⁻¹), far surpassing the PVDF control group (0.15 mA/ 1.95 mAh·g⁻¹). More importantly, deposition morphology analysis reveals an essential difference (Fig. 5g): The S@HA electrode exhibits a two-dimensional interfacial growth mode (2DI), promoting dense and uniform deposition of Li₂S (the inset of Fig. 5d–f); in contrast, the PVDF system exhibits a three-dimensional particulate growth (3DP), resulting in a loose and aggregated deposition morphology. These results reveal that the hydrogen bond effect can achieve controllable transformation and efficient utilization of polysulfides.

Bonding diagram of different binder cathodes: a S@PVDF cathode, b S@CMC, c S@HA cathode. Li2S nucleation tests based on different electrodes for evaluating nucleation kinetics, SEM illustration shows the deposition morphology: d PVDF, e CMC, f HA. g Dimensionless current-time transient to perform peak fitting according to theoretical 2D and 3D models, Im (peak current), and tm (time needed to achieve the peak current) detected from the current-time transients. h Synchrotron X-ray tomography of the S@HA electrode. i S 2p XPS spectra of the different binder electrode after 10th cycles.

This effect is further verified in interfacial stability studies. In situ synchrotron imaging (Fig. 5h and Supplementary Fig. 36) shows that after 100 cycles, the S@HA electrode maintains good sulfur distribution uniformity with a high active sulfur retention rate of 98.6%, far superior to the PVDF system (sulfur loss of 46.6%) (Supplementary Fig. 37). Moreover, XPS tests indicate (Fig. 5i) that no Li₂S deposition peak is detected in the HA system electrode, while a clear Li₂S signal is present in the PVDF system. This contrast directly confirms that the stable interfacial environment constructed by the HA binder not only enhances the transformation kinetics of polysulfides but also fundamentally inhibits the formation of “dead sulfur” by regulating the deposition process, achieving an essential improvement in electrode/interfacial stability.

To evaluate the efficacy of the hydrogen bonding effect, lithium-sulfur batteries were constructed using different binders, and their electrochemical performance was systematically analyzed. At a discharge rate of 1 C (Fig. 6a), the S@HA electrode maintained a specific capacity of approximately 554 mAh·g⁻¹ after 500 cycles, which not only exceeded the initial capacities of S@PVDF and S@CMC electrodes but also indicated highly efficient sulfur utilization. To further assess the suitability of the sulfur electrode under harsh conditions, tests were conducted under lean electrolyte conditions (E/S = 5 uL mg-1). The results demonstrated that even under such conditions, the S@HA electrode exhibited excellent stability at 1 C, delivering an initial discharge capacity of 729.4 mAh·g⁻¹ and retaining 666.2 mAh·g⁻¹ after 200 cycles (Supplementary Fig. 38), with the capacity showing a slight initial increase followed by a gradual decrease. This further confirms the effective stabilizing effect of hydrogen bonding on polysulfides. To evaluate the long-term cycling durability of the binders, charge-discharge cycling tests were performed at a current rate of 0.2 C (Supplementary Fig. 39). The results revealed that the S@HA electrode exhibited an initial discharge capacity of 1347.75 mAh·g⁻¹. In contrast, due to severe polysulfide shuttle effect leading to significant active sulfur loss, the reversible capacities of S@PVDF and S@CMC electrodes decreased to 762.56 mAh·g⁻¹ and 827.87 mAh·g⁻¹, respectively, after 100 cycles. However, the S@HA electrode still maintained a stable reversible capacity of 1038.53 mAh·g⁻¹ after 100 cycles, demonstrating its efficient trapping capability and reversible interaction with polysulfides. Furthermore, long-term cycling tests at a low rate of 0.1 C (Supplementary Fig. 40) showed that the capacity decay rate of the S@HA electrode was only 0.025%, significantly lower than those of the S@PVDF (0.446%) and S@CMC (0.573%) electrodes. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 41, the S@HA electrode exhibited the best capacity retention and cycling stability across various rates, indicating that the hydrogen bonding effect significantly improves the multiphase conversion of sulfur species, thereby enhancing the cycling stability and rate capability of lithium-sulfur batteries.

In battery chemistry, the significant increase in electrode resistance at high current rates primarily originates from interparticle resistance, leading to hindered ion transport. To evaluate the effectiveness of the hydrogen bond effect at high rates, we conducted rate tests at 3 C and variable-rate tests (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Fig. 42). The results showed that the S@HA electrode exhibited high discharge capacity and stability (0.105% per cycle) at high rates, with significantly superior rate performance compared to the S@PVDF and S@CMC electrodes. When the current density was returned to 0.1 C, the reversible capacity of the S@HA electrode was as high as 1130.03 mAh·g⁻¹, while the capacities of the S@PVDF and S@CMC electrodes were only 789.13 mAh·g⁻¹ and 145.21 mAh·g⁻¹, respectively. The significant capacity decay of the S@PVDF and S@CMC electrodes can be attributed to the imbalanced migration and transformation of polysulfides at different rates, leading to the accumulation of insoluble polysulfides, a phenomenon known as “dead sulfur,” which increases electrode resistance and restricts the transport of lithium ions and electrons. In contrast, the excellent rate performance of the S@HA electrode is mainly due to the hydrogen bond network optimizing ion transport pathways and reducing ion migration resistance.

Furthermore, by fabricating high-sulfur-loading electrodes, we further demonstrated the potential of the hydrogen bond effect. As shown in Fig. 6c, when the sulfur loading reached 7.54 mg·cm⁻², the capacity decay rate of the S@HA electrode was only 0.067% per cycle. Even at an ultra-high sulfur loading of 9.2 mg·cm⁻², the battery still maintained a high capacity of 672 mAh·g⁻¹ while preserving good kinetic processes and reversible reactions (Supplementary Fig. 43).

To verify the practical application potential of the HA binder, we assembled pouch battery (Supplementary Fig. 44). Voltage tests showed an output of 2.371 V, and the battery was capable of stably powering a large number of light-emitting diodes. Moreover, the pouch battery subjected to constant current cycling at a rate of 0.2 C exhibited excellent cycling stability (Supplementary Fig. 45). These results further demonstrated the practicality of the HA binder. Compared with carefully designed lithium-sulfur battery binders (Fig. 6d) and existing commercial binders (Fig. 6e), the HA binder showed significant advantages in rate performance and stability.

Essentially, the HA binder, through its abundant functional groups (such as carboxyl, hydroxyl, and amide groups), forms numerous hydrogen bonds with active materials, thereby enhancing intermolecular interactions. This hydrogen bond network not only optimizes the electronic contact between sulfur active components and conductive agents but also significantly improves the redox kinetics of polysulfides, accelerating their transformation process. Meanwhile, the abundant hydrogen bond sites within the network effectively capture LiPSs, preventing their excessive diffusion and loss in the electrolyte (Fig. 6f). The combined effects of these hydrogen bond interactions significantly enhance the overall performance of lithium-sulfur battery.

Conclusions

In summary, this study elucidates a “breathing-type” polysulfide regulation mechanism driven by the dynamic hydrogen bonding network of HA-based binder, clarifying its concentration-energy synergistic effect on the redox reactions of LiPSs. Based on the spatial arrangement of symmetrically arranged polar functional groups (-COOH/ -OH), HA constructs an integrated interfacial structure of “enrichment - catalysis - stabilization”, realizing dynamic regulation of LiPSs diffusion and transformation pathways. This hydrogen-bond-driven breathing mechanism demonstrates remarkable adaptability: during discharge, the extended helical conformation forms high-density binding sites, achieving selective capture and local enrichment of LiPSs; while during charge, the helix-coil conformation transition promotes controllable release of sulfur species through reversible hydrogen bond reorganization. Ultimately, it breaks the inherent limitations of traditional static binders, achieving spatially uniform sulfur deposition. And the battery maintains a capacity of 590.62 mAh g⁻¹ after 200 cycles at a 3 C rate, significantly outperforming traditional binders. Notably, this simple strategy provides a promising solution for promoting low-cost, high-performance, and easily scalable lithium-sulfur batteries, strongly advancing the commercialization process of lithium-sulfur batteries.

Methods

Chemicals

The following chemicals were used in this study: N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP, 99.95 wt%, Aladdin), polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF, 99.9 wt%, DODOCHEM), Carbon (Super P, 99.9%, Timcal), Sulfur (99.95 wt%, Aladdin), Li2S (99.99%, Aladdin) 1,3-dioxolane (DOL, 99.9 wt%), 1, 2-dimethoxyethane (DME, 99.9 wt%), lithium bis (trifluoromethanesulfonic) imide (LiTFSI, 99.99 wt%), lithium nitrate (LiNO3, 99.9 wt%, DODOCHEM), Hyaluronic acid (HA, Mv: 1.0-1.8 M, Aladdin), Sodium carboxymethylcellulose (CMC-2200, DoDoChem), Lithium (99.99%, China Energy Lithium Co., Ltd).

Electrode preparation

A sulfur/ carbon (S/C) composite composed of sulfur and carbon black with a mass ratio of 7:3 was heated in a crucible at 155 °C for 12 h. Thermogravimetric analysis shows that the percentage of sulfur in the active electrode is ~70%. Then, the active material and HA binder are mixed according to the ratio of 10:1, and stirred in deionized water to form a uniform slurry by magnetic stirring. The electrode preparation procedure using CMC binder is the same as above, and the electrode preparation procedure using PVDF binder is carried out in the same way as described above, except that deionized water is replaced by NMP. Aluminum foil is used as a current collector. The electrode was dried in vacuum at 50 °C for 12 h. The loading density of sulfur is between 1.2 and 1.5 mg cm−2.

Coin battery assembly and electrochemical tests

With S@PVDF, S@CMC and S@HA materials as the positive electrode, lithium metal as the negative electrode and polypropylene film as the separator, 80 µL of electrolyte was added to each battery, and the CR2025 button battery was assembled for electrochemical testing.

The electrolyte was 1 M bis (trifluoromethane) sulfonamide lithium salt (LITFSI), which was dissolved in a mixed solution of 1,3-dioxolane (DOL) and dimethyl ether (DME) (1:1, v/v) with 2 wt% LiNO3. Galvanostatic charge–discharge tests were performed using a Neware BTS2300 system (Shenzhen, China) at room temperature at a voltage range of 1.6–2.8 V.

Cyclic voltammetry measurements were performed at a scan rate of 0.1 mV s−1, and the cyclic voltammetry (CV) was recorded at different scanning rates in the voltage range of 1.6–2.8 V using the CHI660E electrochemical workstation instrument. Additionally, electrochemical impedance spectra (EIS) measurements were performed from 100 kHz to 0.1 Hz on an Auto lab PGSTAT-302N.

Pouch battery preparation

Sulfur electrodes with around 1 mg cm−2 were cut to be 4.5 cm × 5 cm (cathode and Al substrate). Cut the lithium foil (5 cm × 6 cm) into a size slightly larger than the anode, and attach the lithium foil to the copper mesh (80 mesh) by beating, with the protruding copper mesh as the tab. Polypropylene is used as the diaphragm. soon afterwards, Place the sulfur electrodes on one side of PP diaphragm. Then, a piece of Li anode was placed on another side of Polypropylene diaphragm. Certain amount of electrolyte (2 mL) was injected into the stack. Then, the package was sealed under vacuum. All battery were assembled in Ar-containing glovebox.

Absorption test

Li2S and S were added at a 1:5 molar ratio to the Li–S electrolyte to prepare the Li2S6 solution. Furthermore, 30 mg of PVDF, CMC and HA were separately dissolved in 5 mL of 20 mmol Li2S6 solutions and placed at room temperature for 24 h to compare the absorption capacity of the polysulfides. The concentration change was observed using UV–Vis (Shimadzu UV-3600i Plus).

Li2S nucleation test

The 0.2 mol L–1 Li2S8 catholyte prepared by mixing lithium sulfide and sublimed sulfur in Tetraglyme solvent with a molar ratio of 1:7. Commercial aluminum foil with a diameter of 12 mm was loaded by Carbon with PVDF, CMC or HA powder for preparing cathode, the ratio of carbon to binder is 7:3. The Li foil served as anode. 20 μL Li2S8 catholyte was dropped onto the cathode and 20 μL LiTFSI (1.0 mol L–1) anolyte was added into anode compartment. The Li2S nucleation test process was mainly divided into two processes: galvanostatically discharged to 2.07 V at 0.112 mA and potentiostatically discharged at 2.02 V until the current was below 10–2 mA. The capacities of Li2S precipitation were analyzed by Faraday’s law.

Materials characterisation

The structure, morphology and composition of the samples were characterised using X-ray diffraction (XRD) (Rigaku mini Flex600X, Cu Kα radiation), a field emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM) (Nova Nano SEM 450), AFM (Bruker Dimension Icon) and TEM (USA Thermo Fisher Talos F200s). The functional groups and chemical bonds in the samples were studied using Raman spectra (Lab RAM HR, 532 nm excitation), FT-IR (German Bruker ALPHA infrared spectrometer), NMR (German Bruker Avance NEO 400 MHz) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) (Thermo Scientific K-Alpha). The operando sulfur K-edge X-ray absorption spectra (XAS) are measured at the Australian Synchrotron (ANSTO). The slurry-coated side was adhered to 3 cm transparent tape, while the back was attached to a glass slide using double-sided tape. The transparent tape was then pulled vertically at a constant speed of 45 mm·min⁻¹ using the tensile tester. Optical images of the peeled electrode and current collector post-testing were captured using a mobile phone camera. Nanoindentation tests were performed on Anton Paar NHT³ Nanoindentation Tester, with a maximum load of 500 µN and a peak load dwell time of 5 s.

DFT calculational method

The electron exchange and correlation were described with GGA-PBE functional42,43,44. The localized double-numerical quality basis set with a polarization d-function (DNP-4.4 file) was chosen to expand the wave functions45. To accommodate the van der Waals interactions, the Grimme-06 (DFT-D2) method was used for all the DFT calculations43,46. The core electrons of the metal atoms were treated using the effective core potentials (ECP)47, and the orbital cutoff was 4.5 Å for all atoms. For the geometry optimization, the convergences of the energy, maximum force, and maximum displacement were set as 1 × 10−5 Ha, 2 × 10−3 Ha/Å, and 5 × 10−3 Å, and the SCF convergence for each electronic energy was set as 1.0 × 10–6 Ha. The adsorption energy and transfection barrier are calculated by the following equations42,43.

Where, \({E}_{{molecule},{gas}}\), \({E}_{{catalyst}}\), \({E}_{{molecule}* }\), and \({E}_{{TS}}\) represent the energy of the gas molecule, the energy of the clean catalyst, the energy of the molecule adsorbed state, and the energy of transition state structure.

Molecular dynamics simulation

Classic molecular dynamics simulations were carried out to investigate the mixed solution from the atomic level. Three cases (System1, System2, System3) were built for Molecular Dynamic simulations.

Case System1 contains 21 HT, 18 Li, 6 TFSI, 6 S4, 10 DME, 10 DOL molecules, Case System2 contains 80 CMC, 18 Li, 6 TFSI, 6 S4, 10 DME, 10 DOL molecules. Case System3 contains 80 PVDF, 18 Li, 6 TFSI, 6 S4, 10 DME, 10 DOL molecules. The initial configuration systems were constructed through the software of PACKMOL48, all the molecules were inserted in a simulation box.

The OPLSAA force field49,50,51 was employed to describe the HT, CMC, PVDF, Li, TFSI, S4, DME, DOL molecules. The CM5 charge was employed. The molecular force field is consisted of nonbonded and bonded interaction. The nonbonded interaction contains van deer Waals (vdW) and electrostatic interaction, which is described by the Eq. 1 and Eq. 2, respectively.

In the equation, \({q}_{i}\)、\({q}_{j}\) are atomic charge, \({r}_{{ij}}\) is the distance between atoms, σ is the atomic diameter, \(\varepsilon\) is the atomic energy parameter.

For different kinds of atoms, the geometric mix rules were adopted for vdW interactions, which is following the Eq. 3. The cutoff distance of vdW and electronic interactions was set to 1.2 nm, and the PME method was employed to calculate long-range electrostatic interactions.

For the simulation, an energy minimization was firstly employed to relax the simulation box. Then, an NVT ensemble with a 1.0 fs time step is employed to optimized the simulation box, where the temperature is set to 298.15 K. The temperature was kept via the Nose-Hoover thermostat. The NVT optimization time was set to 10.0 ns, which is enough long to obtain a stable system. Then, another NVT with a 1.0 fs time step and time was set to 1.0 ns, to record the trajectory for subsequent analysis. the atomic trajectories every 1000 femtoseconds. where the temperature is set to 298.15 K.

In all the MD simulation, the motion of atoms was described by classical Newton’s equation, which was solved using the velocity-Verlet algorithm. And all the Molecular Dynamic simulations were performed by using GROMACS 2022.2 package52. The results were analyzed using Gromacs tool-suites, the Visual Molecular Dynamic program (VMD)53, and additional scripts written by the researchers.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the main text and Supplementary Information. Should any raw data files be needed in another format, all of them available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request (Xue Li, lixue@kust.edu.cn).

References

Manthiram, A., Fu, Y. & Su, Y.-S. Challenges and prospects of lithium-sulfur battery. Acc. Chem. Res. 46, 1125–1134 (2013).

Mikhaylik, Y. V. & Akridge, J. R. Polysulfide shuttle study in the Li/S battery system. J. Electrochem. Soc. 151, A1969–A1976 (2004).

Seh, Z. W., Sun, Y., Zhang, Q. & Cui, Y. Designing high-energy lithium-sulfur battery. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45, 5605–5634 (2016).

Song, X. et al. Solvated metal complexes for balancing stability and activity of sulfur free radicals. Escience 4, 100225 (2024).

Wang, Y. B. et al. Strategies of binder design for high-performance lithium-ion battery: a mini review. Rare Met. 41, 745–761 (2022).

Yang, W. H. et al. Multifunctional sulfur-immobilizing GO/MXene aerogels for highly-stable and long-cycle-life lithium-sulfur battery. Rare Met. 42, 2577–2591 (2023).

Lu, H. et al. Multimodal engineering of catalytic interfaces confers multi-site metal-organic framework for internal preconcentration and accelerating redox kinetics in lithium-sulfur battery. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202318859 (2024).

Xiang, Y. et al. Tuning the crystallinity of titanium nitride on copper-embedded carbon nanofiber interlayers for accelerated electrochemical kinetics in lithium-sulfur battery. Carbon Energy 3, e450 (2024).

Zhao, F.-N., Xue, H. T., Yao, X. J., Wan, L. & Tang, F. L. Theoretically unraveling the performance of 2D-FeS2 as cathode material for Li-S battery. Mater. Today Commun. 38, 107704 (2024).

Mayren, A. et al. Chitosan binders for sustainable lithium-sulfur batteries: Synergistic effects of mechanical and polysulfide trapping properties. Electrochim. Acta 480, 143917 (2024).

Xiong, R. et al. Synergistic improvement of the overall performance of lithium-sulfur batteries. Chin. Sci. Bull. 67, 1072–1087 (2022).

Guo, Y. et al. Interface engineering toward stable lithium-sulfur batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 17, 1330–1367 (2024).

Peng, H.-J. et al. A Cooperative Interface for Highly Efficient Lithium-Sulfur Batteries. Adv. Mater. 28, 9551 (2016).

Li, L. et al. Engineering electronic inductive effect of linker in metal-organic framework glass toward fast-charging and stable-cycling quasi-solid-state lithium metal batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2505700 (2025).

Lu, H. et al. Multimodal engineering of catalytic interfaces confers multi-site metal-organic framework for internal preconcentration and accelerating redox kinetics in lithium-sulfur batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202318859 (2024).

Song, C.-L. et al. 3D catalytic MOF-based nanocomposite as separator coatings for high-performance Li-S battery. Chem. Eng. J. 381, 122701 (2020).

Zhang, M. et al. Versatile separators toward advanced lithium-sulfur batteries: status, recent progress, challenges and perspective. Chemsuschem 17, e202400538 (2024).

Zhu, R. et al. Advances in electrochemistry of intrinsic conductive metal-organic frameworks and their composites: mechanisms, synthesis and applications. Nano Energy 122, 109333 (2024).

Gu, J. et al. Sustaining vacancy catalysis via conformal graphene overlays boosts practical Li-S batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 18, 5940–5951 (2025).

Hao, M. et al. Adsorption-catalysis synergy boosting the conversion of polysulfide over mesoporous carbon confined molecular catalysts. Adv. Energy Mater. 15, 2501226 (2025).

Lu, H. et al. Synergistic adsorption-diffusion-catalytic effect boosting polysulfides conversion by rational isotype heterojunction design for highly reversible lithium-sulfur batteries. Adv. Functional Mater. 2425863 (2025).

Lee, J. et al. Bridging the gap between academic research and industrial development in advanced all-solid-state lithium-sulfur batteries. Chem. Soc. Rev. 53, 5264–5290 (2024).

Qi, B. et al. A review on engineering design for enhancing interfacial contact in solid-state lithium-sulfur batteries. Nano-Micro Lett. 16, 71 (2024).

Zhang, H. et al. Fe3O4-doped mesoporous carbon cathode with a plumber’s nightmare structure for high-performance Li-S batteries. Nat. Commun. 15, 5451 (2024).

Xie, J. et al. A supramolecular capsule for reversible polysulfide storage/delivery in lithium-sulfur batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 16223–16227 (2017).

He, Y. et al. Amphipathic emulsion binder for enhanced performance of lithium-sulfur batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 12, 12681–12690 (2024).

Yu, G. et al. A flame-retardant binder with high polysulfide affinity for safe and stable lithium-sulfur batteries. Sci. China-Chem. 67, 1028–1036 (2024).

Ma, S. et al. Eco-friendly aqueous binder derived from waste ramie for high-performance Li-S battery. Chin. Chem. Lett. 36, 109853 (2025).

Feng, S., Fu, Z. H., Chen, X. & Zhang, Q. A review on theoretical models for lithium-sulfur battery cathodes. Infomat 4, e12304 (2022).

Yang, X., Luo, J. & Sun, X. Towards high-performance solid-state Li-S battery: from fundamental understanding to engineering design. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 2140–2195 (2020).

Li, P. et al. Hyaluronic acid with double helix ion channels for efficient electrolyte retention and polysulfide regulation in lean-electrolyte lithium-sulfur batteries. Adv. Mater. e11272 (2025).

Yang, Q. et al. Chlorine bridge bond-enabled binuclear copper complex for electrocatalyzing lithium-sulfur reactions. Nat. Commun. 15, 3231 (2024).

Yang, Q. et al. An electrolyte engineered homonuclear copper complex as homogeneous catalyst for lithium-sulfur batteries. Adv. Mater. 36, 2405790 (2024).

Yang, Q. et al. Integrated design of homogeneous/heterogeneous copper complex catalysts to enable synergistic effects on sulfur and lithium evolution reactions. Angew. Chem.-Int. Ed. 64, e202415078 (2025).

Li, S. et al. Engineering of lignocellulose pulp binder for ah-scale lithium-sulfur batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 15, 2405461 (2025).

Zhang, L. & Guo, J. Understanding the reaction mechanism of lithium-sulfur battery by in situ/operando X-ray absorption spectroscopy. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 44, 6217–6229 (2019).

Ling, M. et al. Nucleophilic substitution between polysulfides and binders unexpectedly stabilizing lithium sulfur battery. Nano Energy 38, 82–90 (2017).

Zhang, L. et al. Effective electrostatic confinement of polysulfides in lithium/sulfur battery by a functional binder. Nano Energy 40, 559–565 (2017).

Zhang, L. et al. Revealing the electrochemical charging mechanism of nanosized Li2S by in situ and Operando X-ray absorption spectroscopy. Nano Lett. 17, 5084–5091 (2017).

Liang, X., Garsuch, A. & Nazar, L. F. Sulfur cathodes based on conductive mxene nanosheets for high-performance lithium-sulfur battery. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 3907–3911 (2015).

Theibault, M. J. et al. High entropy sulfide nanoparticles as lithium polysulfide redox catalysts. Acs Nano 17, 18402–18410 (2023).

Wang, H. et al. Synergistic interactions of neighboring platinum and iron atoms enhance reverse water-gas shift reaction performance. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 2264–2270 (2023).

Fan, F. et al. Theoretical investigation on the inert pair effect of Ga on both the Ga-Ni-Mo-S nanocluster and the direct desulfurization of 4,6-dimethyldibenzothiophene. Fuel 333, 126351 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. Dynamic structure of active sites in ceria-supported Pt catalysts for the water gas shift reaction. Nat. Commun. 12, 914 (2021).

Wang, J., Cheng, D. G., Chen, F. & Zhan, X. Chlorine-decorated ceria nanocubes for facilitating low-temperature cyclohexane oxidative dehydrogenation: unveiling the decisive role of surface species and acid properties. Acs Catal. 12, 4501–4516 (2022).

McDonald, N. A. & Jorgensen, W. L. Development of an all-atom force field for heterocycles. Properties of liquid pyrrole, furan, diazoles, and oxazoles. J. Phys. Chem. B 102, 8049–8059 (1998).

Sun, D. et al. Engineering high-coordinated cerium single-atom sites on carbon nitride nanosheets for efficient photocatalytic amine oxidation and water splitting into hydrogen. Chem. Eng. J. 462, 142084 (2023).

Liao, C. et al. State interaction linear response time-dependent density functional theory with perturbative spin-orbit coupling: benchmark and perspectives. JACS Au 3, 358–367 (2023).

Martinez, L., Andrade, R., Birgin, E. G. & Martinez, J. M. PACKMOL: a package for building initial configurations for molecular dynamics simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 30, 2157–2164 (2009).

Kaminski, G. A., Friesner, R. A., Tirado-Rives, J. & Jorgensen, W. L. Evaluation and reparametrization of the OPLS-AA force field for proteins via comparison with accurate quantum chemical calculations on peptides. J. Phys. Chem. B 105, 6474–6487 (2001).

Robertson, M. J. et al. Development and testing of the OPLS-AA/M force field for RNA. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 15, 2734–2742 (2019).

Ribeiro, J. & Tajkhorshid, E. Accessible molecular modeling environment with VMD and NAMD. Abstr. Pap. Am. Chem. Soc. 258, 443 (2019).

Nakajima, T., Katouda, M., Kamiya, M. & Nakatsuka, Y. NTChem: a high-performance software package for quantum molecular simulation. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 115, 349–359 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank Kunming University of Science and Technology Analysis and Testing Center and Scientific Compass Company for their testing services. The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Yunnan Engineering Research Center Innovation Ability Construction and Enhancement Projects [2023-XMDJ-00617107], Natural Science Foundation of Yunnan Province [202401AS070646], Natural Science Foundation of Jiangxi Province [20232BAB214038].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wenhao Yang: Writing-original draft, Data curation. Dan You, Zhicong Ni: Writing-original draft, Data curation. Yingjie Zhang: Supervision, Project administration., Jiajun Wang, Weihong Lai: Conceptualization. Yunxiao Wang, Xue Li, Yiyong Zhang: Writing-review & editing, Supervision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, W., You, D., Ni, Z. et al. Hyaluronic acid molecular orientation induces uniform distribution of polysulfides for high-performance lithium-sulfur battery. Commun Mater 6, 261 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00982-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-00982-1