Abstract

Controlling defect states and impurity incorporation in oxide semiconductors is crucial for advancing high-performance thin-film transistors. Here we show that hydrogen impurities act predominantly as deep-level electron traps, critically limiting both performance and reliability. Using density functional theory calculations supported by experimental analysis, we demonstrate that suppressing hydrogen incorporation markedly improves device characteristics. Indium–gallium–zinc oxide transistors fabricated under hydrogen-controlled conditions exhibit enhanced bias stability and, with an aluminum electron-injection layer, achieve a high field-effect mobility of about 120 cm2/V·s, nearly twice that of devices processed in hydrogen-rich environments. These devices also support high-speed switching up to 1 MHz. When integrated with a negative capacitance structure, they exhibit subthreshold swing values as low as 39 mV/dec, surpassing the thermionic limit. Inverter circuits with hydrogen-suppressed IGZO TFTs with an aluminum electron-injection layer deliver a gain of ~50, far exceeding the ~10 of conventional counterparts. These findings highlight hydrogen control as a key enabler of low-power, high-speed oxide electronics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As electronic devices continue to advance rapidly, the demand for high-performance semiconductor technologies has grown significantly. Among various candidates, oxide semiconductors have attracted considerable attention owing to their outstanding electrical properties, including high mobility (≥10 cm2/V·s), large-area uniformity, optical transparency, and compatibility with room-temperature processing1,2. A key advantage of oxide semiconductors lies in their conduction band, which is formed by the overlap of large, spherical 5 s orbitals. This unique electronic structure enables high conductivity even in the amorphous state, making oxide semiconductors highly suitable for various practical applications3,4,5.

These desirable characteristics have driven the successful commercialization of oxide semiconductor-based thin-film transistors (TFTs), which are widely used as backplanes in displays for mobile phones, smartwatches, monitors, automotive systems, and televisions. Beyond display technologies, oxide semiconductors are being actively explored for use in logic circuits, memory devices, and other next-generation electronic systems6,7,8,9. In particular, their compatibility with low-temperature processing methods makes them well-suited for emerging applications in flexible and stretchable electronics10,11.

To further enhance the performance of oxide TFTs, several approaches have been investigated, including crystallization, cation composition control, and the incorporation of metal layers. Among these, the insertion of a metal layer between the source and drain electrodes has proven particularly effective, as it improves carrier injection and reduces carrier scattering, leading to significant performance gains. In previous studies, TFTs using (Zn,Ba)SnO3 (ZBTO)—a defect-suppressed oxide semiconductor—exhibited substantially higher mobility than conventional oxide semiconductor TFTs such as ZTO, IZO, and IGZO, particularly when combined with an electron injection layer12,13,14,15. Remarkably, ZBTO TFTs with an electron injection layer even outperformed ZnON-based TFTs with similar configurations16. This superior performance is attributed to the suppression of oxygen-related defects and improved carrier channel quality, emphasizing the critical importance of precise defect engineering in optimizing oxide TFT characteristics17.

While a range of defect types in oxide semiconductors—such as oxygen vacancies and cation non-stoichiometry—can be effectively modulated through techniques like doping, deposition control, and post-annealing, hydrogen remains uniquely challenging to manage. Unlike other impurities, hydrogen incorporation is highly sensitive to the ambient environment during processing and exhibits complex, site-dependent behavior within the oxide lattice. Even at low concentrations, hydrogen can influence the electronic structure by acting as a shallow donor or by interacting with native defects. At higher concentrations, it promotes the formation of additional defects, degrades material stability, and compromises long-term device reliability. This dual role—as both a mobility enhancer and a source of deep-level traps that induce charge trapping and instability—makes hydrogen a critical but difficult factor to control in oxide semiconductors18,19,20.

Although prior research has examined the effects of hydrogen primarily through its deliberate introduction during fabrication, its behavior under hydrogen-suppressed conditions has not been evaluated thoroughly. In particular, systematic investigations into hydrogen-related defects under low-hydrogen environments remain scarce, hindering a comprehensive understanding of their influence on the electrical properties of oxide semiconductors. Consequently, despite hydrogen’s well-documented dual behavior, effective strategies for managing its incorporation remain underdeveloped.

Recent studies have explored the role of ultra-high vacuum (UHV, ~10⁻8 Torr) sputtering in controlling defect formation in oxide semiconductors due to its significant impact on key TFT performance metrics such as mobility, subthreshold swing, threshold voltage, and stability. Notably, UHV sputtering effectively suppresses hydrogen incorporation—an impurity that enhances mobility at low concentrations but leads to instability through charge trapping when present in excess21. In this study, UHV sputtering was employed to regulate hydrogen incorporation and overall defect chemistry, focusing on both oxygen vacancies and hydrogen-related defects in IGZO thin films.

Reducing hydrogen content led to improved material properties, including higher field-effect mobility and enhanced stability under both positive and negative bias temperature stress. The addition of an electron injection layer further improved performance, achieving a mobility of up to 134 cm2/V·s. Experimental analysis, supported by density functional theory (DFT) simulations, confirmed that these performance enhancements were primarily attributed to the suppression of hydrogen-related defects and their impact on charge trapping dynamics. IGZO TFTs fabricated under UHV conditions also demonstrated high-frequency operation up to 1 MHz, enabled by their high electron mobility. Furthermore, the integration of Al-doped IGZO TFTs into inverter circuits demonstrated the scalability and potential of this approach for logic applications.

These findings underscore the importance of controlling defect chemistry—particularly hydrogen-related defects—as a key aspect of defect engineering. This control is essential for advancing high-performance, energy-efficient oxide semiconductor platforms suitable for next-generation electronics.

Results and Discussion

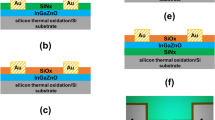

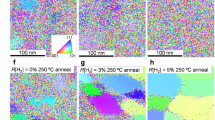

High-quality semiconductor thin films with minimal defect densities are essential for achieving both high mobility and excellent stability in oxide TFTs. Figure 1(a) presents a schematic of the fabrication process for IGZO thin films deposited under low vacuum (LV, 5.0 × 10-6 Torr) and ultra-high vacuum (UHV, hereafter referred to as HV, 3.7 × 10-8 Torr) conditions using a radio frequency (RF) magnetron sputtering system. The HV sputtering system minimizes hydrogen-related impurities in the IGZO films by effectively eliminating residual contaminants from the chamber. Consequently, sputtering under HV conditions enables the formation of high-density, high-quality IGZO thin films with reduced oxygen- and hydrogen-related defect states. Additionally, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images in Fig. 1(a) confirm that IGZO thin films deposited under both LV and HV conditions remain amorphous.

a Schematic diagrams and TEM images of the In-Ga-Zn-O thin film structures deposited by RF magnetron sputtering system under LV and HV conditions. XPS O1s XPS spectra of (b) LV and (c) HV IGZO thin films. d XRR spectra of IGZO thin film deposited by LV and HV conditions. e Thermal desorption spectra of mass number 18 for (i) H2O for LV and HV IGZO films.

Figure 1(b, c) show the O 1 s X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) spectra of IGZO films deposited under LV and HV conditions, respectively. The O 1 s peaks were deconvoluted into three sub-peaks centered at 530.7 ± 0.1 (O1), 531.8 ± 0.1 (O2), and 532.9 ± 0.1 eV (O3), which correspond to metal–oxygen bonds (O1), oxygen vacancies (O2), and hydroxyl group-related bonds (O3)22. The binding energies were calibrated using the C 1 s peak set at 285.6 eV. The O2 peak, indicative of oxygen-deficiency-related defects, accounted for 24.37% in the HV-deposited film, which is lower than the 25.43% observed for the LV-deposited film. This reduction in oxygen vacancy concentration confirms that fewer defect states are introduced under HV conditions due to the diminished presence of residual gases and external contaminants during deposition. Moreover, the hydroxyl-related O3 peak ratio was also lower in the HV-deposited film, further suggesting improved film quality under high-vacuum conditions.

The film density and structural quality of the oxide channel layer, both of which are strongly influenced by deposition conditions, directly affect device performance. To evaluate film density, X-ray reflectometry (XRR) was performed. Figure 1(d) displays the XRR spectra and fitting data for both LV and HV IGZO films. The higher critical angle observed in the HV-deposited film indicates greater film density compared to the LV sample. Quantitatively, the film density increased from 5.90 to 6.08 g/cm3 as the vacuum level was increased during the deposition process. This densification aligns with the atomic force microscopy (AFM) analysis shown in Supplementary Fig. 1, where the HV-deposited IGZO film exhibited a smoother surface with a root-mean-square (RMS) roughness of 0.065 nm, compared to 0.083 nm for the LV-deposited counterpart. These results collectively confirm the superior quality of IGZO films prepared under HV conditions23.

Thermal desorption spectroscopy (TDS) results in Fig. 1(e) and Supplementary Fig. 2(a)–(b) reveal the presence of hydrogen-related impurities—mainly OH and H2O—in the IGZO films. At lower temperatures, desorption of hydrogen species is attributed to physically adsorbed molecules on the film surface. However, desorption occurring above 300° C is indicative of chemically incorporated hydrogen species formed through reactions between the IGZO film and residual H2O in the sputtering chamber. Across the entire temperature range, the LV-deposited film exhibits significantly greater hydrogen content than the HV sample. During deposition, residual H2O in the chamber may dissociate into H+ and OH⁻, which can react with the IGZO target or growing film, leading to incorporation of OH⁻ into the film matrix24. While moderate hydrogen incorporation can passivate shallow traps and improve stability and electrical performance, excessive hydrogen content can lead to the formation of deep trap states in the channel. In particular, the higher OH⁻ concentration in the LV-deposited IGZO film may contribute to the reduced film density observed in XRR analysis25, consistent with the observed degradation in structural and electronic quality. During post-deposition annealing, thermally unstable OH- species can desorb from the matrix, leaving behind oxygen vacancies (Vo). In addition, radical fragments originating from residual H2O in the chamber may also interact with lattice oxygen, providing a secondary pathway for vacancy generation.

To understand and visualize the defect states in IGZO thin films, the dielectric function (ε2) spectra were analyzed using spectroscopic ellipsometry (SE), as shown in Fig. 2(a) and (b). The SE spectra were deconvoluted into two distinct band-edge states, denoted as D1 and D2, which provide critical information on the defect levels below the conduction band minimum (CBM)26,27. It is well established that D1 and D2 correspond to shallow donor states and deeper electron trap states, respectively, located below the conduction band edge (CBE).

Spectroscopic ellipsometry (SE) spectra of the dielectric function (ε2), deconvoluted into two distinct band edge states: D1 (shallow) and D2 (relatively deep), for IGZO thin films deposited under (a) LV and (b) HV conditions. c Infrared spectra of LV and HV IGZO thin films. d Schematic energy band diagram of the defect states in IGZO thin films deposited under LV and HV conditions.

The SE spectra revealed a clear distinction in defect-related states between IGZO films deposited under LV and HV conditions. Specifically, the HV-deposited films exhibited significantly lower intensities for both the D1 and D2 peaks, indicating a reduction in defect states compared to the LV-deposited films. These states, typically associated with oxygen vacancies (VO), introduce localized energy levels within the bandgap, which can degrade charge carrier transport and device stability. This result highlights the critical influence of deposition environment on defect formation in IGZO thin films. The lower defect density in HV-deposited films suggests superior electronic properties, such as enhanced carrier mobility, reduced subthreshold swing, and improved operational stability. The reduction of oxygen vacancy-related defects directly contributes to better device performance and reliability.

To further compare deep-trap states in IGZO films prepared under LV and HV conditions, infrared (IR) spectroscopy was performed. As shown in Fig. 2(c), a characteristic peak appears at 1379 cm−1, corresponding to hydrogen-related defects (H⁻). These defects are known to introduce deep trap states near the valence band maximum (VBM), resulting in charge trapping and long-term instability in oxide semiconductors28. The HV IGZO films exhibited a significantly weaker peak at 1379 cm−¹ compared to their LV counterparts, indicating reduced hydrogen incorporation and a lower concentration of deep-trap states. This suppression of hydrogen-related defects under HV conditions further supports the expectation of improved electrical performance and stability.

Based on the SE and IR analyses, an energy band diagram illustrating the defect states in IGZO thin films is presented in Fig. 2(d). This diagram summarizes the relative positions of the D1 and D2 states, along with the deep-trap states introduced by VO and H⁻. The reduced densities of these states in HV-deposited films indicate a more stable electronic structure and lower likelihood of trap-assisted charge transport, both of which are essential for reliable device operation. Together, the SE and IR results provide a comprehensive understanding of how vacuum conditions during deposition critically affect the defect landscape in IGZO thin films, underlining the importance of process optimization for achieving high-performance electronic devices.

To examine the electrical properties of transistors influenced by the defect states in the IGZO active layer, two types of TFT devices were fabricated and evaluated: one incorporating an HV-deposited IGZO film, and the other using an LV-deposited film. Figure 3(a, b) display the electrical characteristics of the respective devices, with the dotted lines representing the extracted field-effect mobility. Transfer parameters were obtained from the saturation regime with the drain voltage (VD) fixed at 10 V. Additionally, transfer curves for nine TFTs fabricated under each deposition condition are provided in Supplementary Fig. 3(a) and (b).

The HV IGZO TFT, fabricated with a high-density channel and reduced defect states, demonstrated excellent performance, exhibiting a subthreshold swing of 150 mV/dec and a field-effect mobility of 13.8 cm2/V·s. In contrast, the LV IGZO TFT, characterized by a lower-density channel and higher defect density, showed inferior performance, with a subthreshold swing of 210 mV/dec and a field-effect mobility of only 9.67 cm2/V·s. The degraded characteristics of the LV device are attributed to the presence of voids and electron trap sites within the low-density structure, which hinder charge transport and adversely affect the switching behavior of the transistor.

Next, an electron injection layer (EIL) of Al were introduced into both LV and HV IGZO TFTs, and their electrical characteristics were evaluated and compared. The EIL was deposited directly onto the IGZO active layer, covering half the channel length. To optimize the mobility enhancement effect of the EIL, electrical characteristics were analyzed as a function of sputtering power and thickness, as shown in Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5. Increasing the sputtering power improved the quality of the EIL, resulting in significant mobility enhancement. However, at sputtering powers of 60 W or higher, plasma-induced damage led to device breakdown. Similarly, increasing the thickness of the EIL also improved mobility due to enhanced electron injection. However, beyond a thickness of 20 nm, mobility saturated, with no further substantial improvements. Based on these results, the optimal EIL deposition conditions were determined to be a sputtering power of 40 W and a thickness of 20 nm. Furthermore, cross-sectional TEM images (Supplementary Fig. 6) confirmed that both LV and HV IGZO films maintained their amorphous phase after the introduction of the EIL, with no signs of crystallization.

Figure 3(c) compares the transfer characteristics and extracted field-effect mobility of EIL IGZO TFTs deposited under LV and HV conditions. The corresponding transfer parameters for both the reference and EIL-introduced devices are summarized in Table 1. The results reveal that the mobility enhancement effect of the EIL was significantly greater in the HV IGZO devices, reaching 118.2 cm2/V·s, compared to 58.0 cm2/V·s in the LV IGZO devices. In addition, HV IGZO devices exhibited steeper subthreshold swing (SS) characteristics than their LV counterparts, regardless of the presence of the EIL. In a previous study, it was demonstrated that incorporating an EIL into oxide semiconductor-based transistors forms a conducting region and induces an electron injection effect. The substantial mobility improvement observed in HV IGZO TFTs is attributed to the low density of defect states in the IGZO active layer, which enables injected electrons from the Al EIL to contribute effectively to conduction without significant trapping or scattering.

It is also noted that IGZO TFTs incorporating other EIL materials—including In-Sn-O (ITO), In, and Au, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 7—exhibited similar or slightly enhanced electrical performance. This suggests that the EIL devices do not form an omega-shaped (ω-shaped) current path, a configuration reported to result from the low resistance of certain EIL29. Moreover, EIL HV IGZO TFTs fabricated using a one-step process that simultaneously forms the source, drain, and EIL showed a 13.1-fold mobility increase, achieving 103.6 cm2/V·s (Supplementary Fig. 8). The slightly lower mobility compared to that of the optimized EIL device may be attributed to resistance introduced by the thin source/drain electrodes. Importantly, these three layers were deposited simultaneously with a thickness of 20 nm using RF sputtering, demonstrating that this approach does not add complexity or increase fabrication costs.

Reliability tests were carried out under positive bias temperature stress (PBTS) and negative bias temperature stress (NBTS), with the threshold voltage shift (ΔVTH) values for both LV and HV IGZO TFTs presented in Fig. 3(d) and (e). The stress temperatures were set at 60 and 100 °C. Each device underwent stability test for 3600 s at a fixed gate voltage (VGS = ± 2 MV/cm) and drain voltage (VDS = 0.1 V). The transfer curves under bias stress conditions are shown in Supplementary Fig. 9. HV IGZO devices exhibited excellent stability under both NBTS and PBTS, maintaining ΔVTH values within ± 0.3 V even at 100°C. This reliable performance is attributed to the reduced density of defect states and the optimized hydrogen concentration in the IGZO films deposited under HV conditions30,31. In contrast, IGZO films deposited under LV conditions contain a higher density of defect states, which promote charge trapping and result in larger ΔVTH shifts under bias temperature stress.

Notably, LV IGZO devices with high hydrogen content showed significant degradation in stability under negative bias temperature illumination stress (NBTIS, 1000 lux), as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 10. The time-dependent evolution of ΔVTH under NBTIS is compared in Fig. 3(f). This degradation is attributed to hydrogen-related defects that introduce localized deep states within the bandgap. These states can be photoexcited under illumination, altering their charge states. Under negative bias, reorganizing these states leads to persistent electron trapping32,33. These results highlight the critical role of suppressing hydrogen-induced defects in improving both the stability and electrical performance of IGZO TFTs.

In addition to the substantial mobility enhancement, EIL HV IGZO TFTs exhibited highly stable operation under both PBTS and NBTS at 100 °C, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 11. This indicates that the incorporation of the EIL does not introduce additional defects into the oxide semiconductor. The combination of high mobility and excellent thermal reliability underscores the potential of oxide semiconductors for use in a broad range of applications, extending beyond displays to include semiconductor memory devices.

As demonstrated, the enhancement in field-effect mobility due to the EIL is more significant in HV IGZO TFTs than in LV counterparts. This difference is attributed to variations in hydrogen concentration between the two IGZO channels, as hydrogen is known to form defects that trap electrons in oxide semiconductors34,35,36. To further investigate this, DFT calculations were performed, focusing on substitutional hydrogen at oxygen sites. These sites are known to be kinetically stable and can persist even after annealing at 400°C28,37.

Our calculations reveal that substitutional hydrogen in amorphous IGZO (a-IGZO) can behave as both a donor (\({{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{{{{\rm{O}}}}}^{+}\)) and an acceptor [\({({{{\rm{H}}}}-{{{\rm{DX}}}})}^{-}\)]. In the donor configuration (\({{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{{{{\rm{O}}}}}^{+}\)), the hydrogen atom forms multicenter bonds with surrounding cations37, as shown in Fig. 4(a), which prevents the formation of midgap states and generates a free electron. In contrast, the acceptor-like defect \({({{{\rm{H}}}}-{{{\rm{DX}}}})}^{-}\) introduces a deep-level trap by capturing an electron (Fig. 4(b))34,35. This deep level originates from the interaction between the hydrogen 1 s orbital and a nearby cation–cation bond state (Fig. 4(c)).

Density of states (DOS) for (a) \({{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{{{{\rm{O}}}}}^{+}\) and (b) \({({{{\rm{H}}}}-{{{\rm{DX}}}})}^{-}\) models. In (b), the trap level is fully occupied with two electrons. c The charge density distribution of the trap state in (b). d Transition levels of three different substitutional H defects in IGZO. The values of \(\varepsilon (+/-)\) are referenced to the conduction band minimum.

Figure 4(d) shows the transition levels \(\varepsilon (+/-)\), which represent the Fermi level position where the formation energies of \({{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{{{{\rm{O}}}}}^{+}\) and \({({{{\rm{H}}}}-{{{\rm{DX}}}})}^{-}\) become equal, for three different substitutional configurations. Typically, donor defects are more stable at lower Fermi levels (\({E}_{{{{\rm{F}}}}}\)) because donating electrons to the conduction band costs less energy, whereas acceptors follow the opposite trend. Therefore, \({{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{{{{\rm{O}}}}}^{+}\) dominates when \({E}_{{{{\rm{F}}}}} < \varepsilon (+/-)\), while \({({{{\rm{H}}}}-{{{\rm{DX}}}})}^{-}\) becomes more favorable when \({E}_{{{{\rm{F}}}}} > \varepsilon (+/-)\). The calculated transition levels lie near the conduction band minimum (CBM), suggesting that both configurations can coexist in n-type IGZO.

Importantly, these results indicate that substitutional hydrogen can act as electron traps when the transistor is turned on. As the gate voltage increases, the Fermi level near the interface between the gate insulator and the IGZO channel rises above the CBM. Under such high \({E}_{{{{\rm{F}}}}}\) conditions, \({{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{{{{\rm{O}}}}}^{+}\) defects near the interface tend to convert into the more stable \({({{{\rm{H}}}}-{{{\rm{DX}}}})}^{-}\) configuration by capturing free electrons. This electron-trapping process is expected to be more significant in LV-IGZO films due to their higher hydrogen concentration.

In HV-IGZO, however, when an EIL is introduced, a substantial number of \({{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{{{{\rm{O}}}}}^{+}\) defects are likely converted to \({({{{\rm{H}}}}-{{{\rm{DX}}}})}^{-}\) even before the gate voltage sweep, due to pre-injection of free electrons from the EIL. As a result, the remaining population of \({{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{{{{\rm{O}}}}}^{+}\) traps that could capture electrons during the VG sweep is considerably lower. In contrast, LV-IGZO, with its higher hydrogen content, retains a larger number of \({{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{{{{\rm{O}}}}}^{+}\) defects even after electron injection from EIL. Therefore, the EIL is more effective in enhancing the field-effect mobility of HV-IGZO TFTs than in LV-IGZO TFTs.

Another key implication of our simulation is that bias-induced VTH shifts are closely tied to the hydrogen concentration. As \({{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{{{{\rm{O}}}}}^{+}\) and \({({{{\rm{H}}}}-{{{\rm{DX}}}})}^{-}\) have distinct atomic configurations, transitions between them—electron trapping (\({{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{{{{\rm{O}}}}}^{+}+2{e}^{-}\to {({{{\rm{H}}}}-{{{\rm{DX}}}})}^{-}\)) and detrapping—require atomic rearrangements. These structural changes are thermally activated, meaning an energy barrier must be overcome. Under applied positive (or negative) gate bias, this barrier is lowered, allowing rapid trapping (or detrapping) of electrons. However, in the absence of external bias, the recovery is much slower, resulting in measurable shifts in threshold voltage.

Given this mechanism, HV-IGZO devices—having lower hydrogen concentrations—exhibit smaller VTH shifts compared to their LV-IGZO counterparts, which aligns with our experimental findings. These results underscore the critical importance of controlling hydrogen-related defects in achieving high-performance oxide semiconductors. While ultra-high vacuum deposition can mitigate such defects to some extent, further strategies are required to suppress hydrogen incorporation more effectively. Promising approaches include defect passivation, targeted doping, and optimized post-deposition annealing to reduce hydrogen-induced instability.

To explore potential applications in low-power electronic circuits beyond displays, EIL HV IGZO TFTs with high-κ Al2O3 gate dielectrics were fabricated (Supplementary Fig. 12(a) and (b)). These high-k EIL HV IGZO devices exhibited a nine-fold enhancement in field-effect mobility of ~134 cm2/V·s and achieved a steep SS of 80 mV/dec, while supporting low-voltage operation. To the best of our knowledge, this represents the highest performance reported in the literature to date. Figure 5(a) compares the field-effect mobility and SS values obtained in this work with previously reported oxide transistors incorporating high-κ gate dielectrics38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48. A detailed comparison of electrical parameters is summarized in Supplementary Table 1. While some prior transistors demonstrate steep SS values below 100 mV/dec, they generally exhibit limited mobility (<60 cm2/V·s). In contrast, devices with very high mobility (>100 cm2/V·s) tend to show relatively large SS values exceeding 100 mV/dec.

Comparison of the field-effect mobility (a) as a function of subthreshold swing and (b) operating frequency for the references and this work. Circles represent TFTs with the same gate dielectric material, corresponding to their color in (a). c Transfer characteristics of HV EIL IGZO TFTs with ferroelectric HZO and high-k Al2O3 gate dielectric layer. d Point SS values as a function of drain current for the HV EIL IGZO TFTs with HZO and Al2O3 layer.

The high-speed switching characteristics of the EIL HV IGZO TFTs were evaluated under pulsed gate voltages ranging from −10to 10 V at frequencies of 10 kHz, 0.1 MHz, and 1 MHz, with a fixed drain voltage of 5 V. At 10 kHz and 0.1 MHz, the devices maintained stable and consistent drain currents in the milliampere range with negligible noise (Supplementary Fig. 13). Even at 1 MHz, the devices continued to exhibit reliable gate switching and consistent drain current modulation with minimal error. When benchmarked against previously reported oxide TFTs in terms of mobility and operating frequency, the EIL HV IGZO device developed in this work achieved the highest performance (Fig. 5(b))49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57. These results highlight the effectiveness of the high-mobility EIL HV IGZO structure in improving both charge transport and switching speed, underscoring its promise for future high-speed electronics.

EIL HV IGZO negative capacitance (NC) field-effect transistors (FETs) were also fabricated using HfxZr1-xO2 (HZO) as the ferroelectric layer and Al2O3 as the high-κ dielectric. Their electrical performance, particularly when integrated with an Al EIL for mobility enhancement, is shown in Fig. 5(c). Figure 5(d) further presents the point SS as a function of drain current, extracted from the transfer characteristics. The EIL HV IGZO NC-FET exhibited an exceptionally low SS value of 39.7 mV/dec—well below the thermionic Boltzmann limit of 60 mV/dec—highlighting its strong potential for use in low-power applications such as dynamic random-access memory (DRAM)58,59. Moreover, the device incorporating the Al EIL showed a significantly higher drain current compared to the device without the EIL (Supplementary Fig. 12(c)). This ultralow SS behavior is attributed to the negative capacitance effect arising from the HZO ferroelectric layer, which exhibits negative differential capacitance in the energy barrier region during polarization switching.

Finally, two EIL HV IGZO TFTs were integrated to construct an inverter logic circuit, as illustrated in the schematic layout in Fig. 6(a). The voltage transfer characteristics and gain of the inverter circuit employing the Al EIL are presented in Fig. 6(b) and (c), respectively. For comparison, the performance of an inverter composed of HV IGZO TFTs without the Al EIL is shown in Supplementary Fig. 14. Measurements were conducted at supply voltages (VDD) ranging from 1−5 V in 1 V steps, with the input voltage (VIN) swept from −5 to 5 V. The results confirmed full-swing inverter operation. The inverter gain, calculated as G = ∂VOUT/∂VIN, reached 7.43 for the configuration without the Al EIL at VDD = 5 V. In contrast, the inverter incorporating EIL HV IGZO TFTs demonstrated significantly improved gain values ranging from 7.5−50.2 depending on VDD. This gain enhancement is attributed to the increased switching speed enabled by the high mobility of the EIL HV IGZO devices.

Conclusions

Hydrogen, though commonly present, is often an overlooked element in oxide semiconductors, despite its subtle yet significant impact on device performance. In this study, the influence of hydrogen on defect formation and charge transport characteristics in oxide semiconductors has been systematically investigated. IGZO films deposited under high-vacuum (HV) conditions exhibited lower hydrogen content and a reduced density of oxygen vacancies, resulting in improved film quality and enhanced electrical performance. DFT calculations revealed that substitutional hydrogen in amorphous IGZO tends to transform into deep-level trap states under bias stress, ultimately degrading device performance and long-term stability. IGZO TFTs fabricated under HV conditions demonstrated enhanced field-effect mobility (up to 134 cm2/V·s), a low subthreshold swing (as low as 39.7 mV/dec), and excellent bias stability (ΔVTH < ±0.3 V at 100°C). These devices also supported high-speed operation at 1 MHz and were successfully integrated into inverter logic circuits, exhibiting high gain and confirming their scalability and suitability for low-power, high-performance applications. Overall, the findings underscore the critical role of hydrogen in oxide semiconductor physics and offer valuable insights into defect engineering strategies for advancing future high-performance electronic devices.

Methods

Device fabrication

The reference and Al-introduced IGZO transistors were fabricated on heavily boron-doped p-type Si substrates with a thermally grown 100 nm-thick SiOx. The substrate was sonicated in acetone and methanol for 10 min each and then dried with N2 gas. 20 nm-thick IGZO thin film was deposited on the p-Si substrates using a radio frequency (RF) magnetron sputtering system. Then, rapid thermal annealing (RTA) was conducted at 400 °C for one hour in air ambient. Subsequently, 100 nm-thick Aluminum (Al) Source/Drain (S/D) electrodes were formed by thermal evaporation. Finally, the Al electron injection layer was deposited using RF sputtering system, where Ar flow rate and working pressure are 10 sccm and 3 mTorr, respectively. Various Al plasma powers (20, 40, and 60 W) were applied to compare the effect of the Al electron injection layer. All thin films were patterned by shadow masks and the channel width and length (W/L) are 800/200 μm, respectively. In devices with high-k dielectrics and inverter circuits, a 40 nm-thick ITO gate electrode was deposited via sputtering. Additionally, 50 nm-thick high-k Al2O3 dielectric layers were fabricated using the PEALD process with a plasma power of 50 W.

Fabrication of IGZO thin film

a-IGZO films were deposited by RF magnetron sputtering using polycrystalline InGaZnO4 target. RF power, oxygen flow rate ratio [RO2 = [O2]/([O2]+[Ar])], Ptot was fixed at values of 80 W, 4%, and 2 mTorr, respectively. Base pressure of the sputtering chamber varied from 3.7 × 10-8 Torr to 5.0 × 10-6 Torr to control the amounts of defect states and hydrogens incorporated in the IGZO film.

Characterizations

Cross-sectional transmission electron microscopy (TEM) samples were fabricated using an in situ lift-out technique within a dual-beam focused ion beam (FIB) system (FEI Helios NanoLabTM). To investigate the chemical bonding states of tin cations and oxygen anions, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was conducted utilizing a monochromatic Al Kα X-ray source. Prior to the XPS measurements, a low-energy Ar⁺ ion beam (200 eV) was applied for 60 seconds to remove potential surface contaminants. The desorption of H-related chemical species such as H, H2, OH, and H2O were analyzed with thermal desorption spectroscopy measurement (ESCO, EMD-WA 1000S).

Density functional theory calculations

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were carried out using Vienna Ab-initio Simulation Package with PAW pseudopotentials60,61. The energy cutoff for expanding plane-wave basis was set to 400 eV. The PBE functional62 was employed to evaluate exchange-correlation energy, with an on-site energy (Ueff) of 7.5 eV for Zn 4 d states. The IGZO supercell model consisted of 18 formula units of InGaZnO4, and its amorphous structure was generated by means of the melt-quench method via ab-initio molecular dynamics simulations63. A k-point of (0.25, 0.25, 0.25) was sampled for supercell calculations. To address the band-gap underestimation inherent to the PBE method, the band edges were shifted based on quasiparticle energy corrections reported in a previous study63.

Data availability

Data are available from the corresponding authors (youngho84@inu.ac.kr, j.kim@unist.ac.kr, or khs3297@dongguk.edu) upon reasonable request.

References

Nomura, K. et al. Room-temperature fabrication of transparent flexible thin-film transistors using amorphous oxide semiconductors. nature 432, 488–492 (2004).

Byeon, G. et al. Solution-state NMR assignment and secondary structure propensity of the full length and minimalistic-truncated prefibrillar monomeric form of biofilm forming functional amyloid FapC from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Inform. Display 24, 159–165 (2023).

Kamiya, T., Nomura, K. & Hosono, H. Origins of high mobility and low operation voltage of amorphous oxide TFTs: electronic structure, electron transport, defects and doping. J. Display Technol. 5, 273–288 (2009).

Park, J.-M. et al. All-solid-state synaptic transistors with lithium-ion-based electrolytes for linear weight mapping and update in neuromorphic computing systems. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 47229–47237 (2023).

Park, J.-M. et al. Oxide thin-film transistors based on i-line stepper process for high PPI displays. J. Inform. Display 24, 103–108 (2023).

Tripathi, A. K. et al. Applied physics letters 98, 202105 2011. Appl. Phys. Lett. 98, 2011 (2011).

Lee, M. J. et al. Multi-layered culture of human skin fibroblasts and keratinocytes through three-dimensional freeform fabrication. Adv. Funct. Mater. 19, 1587–1595 (2009).

Inoue, H. et al. Nonvolatile memory with extremely low-leakage indium-gallium-zinc-oxide thin-film transistor. IEEE J. Solid State Cir. 47, 2258–2265 (2012).

Song, Y.-W. et al. Doping modulated ion hopping in tantalum oxide based resistive switching memory for linear and stable switching dynamics. Appl. Surf. Sci. 631, 157356–157356 (2023).

Lee, G. et al. Enhancing energy density in flexible all-solid-state supercapacitors via dielectricizer zwitterion-containing quasi-solid-state polymer electrolyte (Adv. Funct. Mater. 52/2024. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2405530 (2024).

Petti, L. et al. Metal oxide semiconductor thin-film transistors for flexible electronics. Appl. Phys. Rev. 3, 021303 (2016).

Nahm, H.-H., Kim, H.-D., Park, J.-M., Kim, H.-S. & Kim, Y.-H. ACS Applied Mater. Interfaces 12, 3719 (2019).

Park, J.-M. et al. Improved field-effect mobility of In–Ga–Zn–O TFTs by oxidized metal layer. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 67, 4924–4928 (2020).

Lee, J., Bak, S.-Y., Lee, S.-H., Jang, H. & Yi, M. Super-Lamination HZO/ZrO₂/HZO of ferroelectric memcapacitors with morphotropic phase boundary (MPB) for high capacitive ratio and non-destructive readout. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 45, 2355–2358 (2024).

Lee, S. H. et al. J. Alloys Compd 862, 158009 (2021).

Kim, T., Kim, M. J., Lee, J. & Jeong, J. K. Boosting carrier mobility in zinc oxynitride thin-film transistors via tantalum oxide encapsulation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 22501–22509 (2019).

Park, J.-M. et al. Metal-induced n+/n homojunction for ultrahigh electron mobility transistors. NPG Asia Mater. 12, 81 (2020).

Pan, W. et al. J. Alloys Compd. 947, 169509 (2023).

Nam, Y., Kim, H.-O., Cho, S. H. & Park, S.-H. K. Effect of hydrogen diffusion in an In-Ga-Zn-O thin film transistor with an aluminum oxide gate insulator on its electrical properties. RSC Adv. 8, 5622–5628 (2018).

Kim, H. J. et al. Role of incorporated hydrogen on performance and photo-bias instability of indium gallium zinc oxide thin film transistors. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 46, 055104 (2012).

Miyase, T. et al. ROles of hydrogen in amorphous oxide semiconductor In-Ga-Zn-O: comparison of conventional and ultra-high-vacuum sputtering. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 3, 3085–Q3090 (2014).

Velichko, R., Magari, Y. & Furuta, M. Defect passivation and carrier reduction mechanisms in hydrogen-doped In-Ga-Zn-O (IGZO:H) films upon low-temperature annealing for flexible device applications. Materials 15, 334 (2022).

Grochowski, J. et al. Origin of lower film density and larger defect density in amorphous In–Ga–Zn–O deposited at high total pressure. J. Display Technol. 11, 523–527 (2015).

Ide, K. et al. Effects of working pressure and annealing on bulk density and nanopore structures in amorphous In–Ga–Zn–O thin-film transistors. Japanese J. Appl. Phys. 56, 03BB03 (2017).

Kim, J. et al. Radiation-induced liver disease: current understanding and future perspectives. NPG Asia Mater. 9, e359 (2017).

Li, Q., Ma, J., Hu, K. & Hu, H. A low-cost and high-performance casted titanium matrix composite with Cr3C2 additions. Mater. Lett. 330, 133407–133371 (2023).

Kim, D.-G. et al. Negative threshold voltage shift in an a-IGZO thin film transistor under X-ray irradiation. RSC Adv. 9, 20865–20870 (2019).

Bang, J. Matsuishi, S. Hosono, H. Hydrogen anion and subgap states in amorphous In–Ga–Zn–O thin films for TFT applications. Appl. Phys. Lett. 110, 232105 (2017).

Lee, J. Y., Ju, B.-K. & Lee, S. Y. Frequency response characteristics depending on the metal capping structure and length of the amorphous SiZnSno thin film transistor. Trans. Electrical Electronic Mater. 24, 279–284 (2023).

Kim, D.-G. et al. Thermally activated defect engineering for highly stable and uniform ALD-amorphous IGZO TFTs with high-temperature compatibility. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 36550–36563 (2023).

Aslam, M. et al. Temperature-dependent hydrogen modulations of Ultra-Scaled a-IGZO thin film transistor under gate bias stress. IEEE Open J. Nanotechnol. 5, 9–16 (2024).

Takeda, Y., Takahashi, T., Miyanaga, R., Bermundo, J. P. S. & Uraoka, Y. Degradation due to photo-induced electron in top-gate In-Ga-Zn-o thin film transistors with n−region under negative bias stress and light irradiation. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 44, 765–768 (2023).

Dang, G. T., Kawaharamura, T., Furuta, M, Saxena, S., Allen, M. W. Stability of In-Ga-Zn-O metal-semiconductor field-effect-transistors under bias, illumination, and temperature stress. Appl. Phys. Lett. 107, 143504 (2015).

Kang, Y. et al. Fully drawn all-organic flexible transistors prepared by capillary pen printing on flexible planar and curvilinear substrates. Adv. Electronic Mater. 1, 1400006 (2015).

Nahm, H.-H., Park, C. & Kim, Y.-S. Bistability of hydrogen in ZnO: origin of doping limit and persistent photoconductivity. Sci. Rep. 4, 4124 (2014).

Kang, Y. & Han, S. An origin of unintentional doping in transition metal dichalcogenides: the role of hydrogen impurities. Nanoscale 9, 4265–4271 (2017).

Janotti, A. & Van de Walle, C. G. Hydrogen multicentre bonds. Nat. Mater. 6, 44–47 (2007).

Zhao, X.-H. et al. Fracture toughness of Ti2AlNb alloy with different Al content: Intrinsic mechanism, extrinsic mechanism and prediction model. J. Alloy Compd. 952, 170068–170062 (2023).

Zhang, Y., Lin, Y., He, G., Ge, B. & Liu, W. Balanced performance improvement of a-InGaZnO thin-film transistors using ALD-derived Al2O3-passivated high-k HfGdOxDielectrics. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2, 3728–3740 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. Ultraviolet-assisted low-thermal-budget-driven α-InGaZnO thin films for high-performance transistors and logic circuits. ACS nano 16, 4961–4971 (2022).

Liu, H. et al. High performance and hysteresis-free a-IGZO thin film transistors based on spin-coated hafnium oxide gate dielectrics. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 44, 1508–1511 (2023).

Samanta, S. et al. Low subthreshold swing and high mobility amorphous indium–gallium–zinc-oxide thin-film transistor with thin HfO2Gate dielectric and excellent uniformity. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 41, 856–859 (2020).

JinJ. Adv. Electron. Mater. 9, 22011172023.

Kim, D.-G. et al. Selectively nitrogen doped ALD-IGZO TFTswith extremely high mobility and reliability. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 31652–31663 (2023).

Kim, M. et al. The impact of plasma-enhanced atomic layer deposited ZrSiOx insulators on low voltage operated In-Sn-Zn-O thin film transistors. Ceramics Int. 45, 19166–19172 (2019).

Kim, J., Choi, S., Jo, J.-W., Park, S. K. & Kim, Y.-H. Dual effects of human placenta-derived neural cells on neuroprotection and the inhibition of neuroinflammation in a rodent model of Parkinson's disease. Thin Solid Films 660, 814–830 (2018).

Choi, C. H., Kim, T., Kim, M. J., Yoon, S. H. & Jeong, J. K. Mechanism of external stress instability in plasma-enhanced ALD-Dderived HfO2/IGZO thin-film transistors. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 70, 2317–2323 (2023).

Kim, Y. S., Hwang, T., Oh, H. J., Park, J. S. & Park, J. S. A microphysiological system with an anaerobic air-liquid interface and functional mucus layer for coculture of intestinal bacteria and primary human colonic epithelium. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 11, 2301097 (2024).

Wang, W. et al. CMOS backend-of-line compatible memory array and logic circuitries enabled by high performance atomic layer deposited ZnO thin-film transistor. Nat. Commun. 14, 6079 (2023).

Naqi, M., Cho, Y. & Kim, S. High-speed current switching of inverted-staggered bottom-gate a-IGZO-based thin-film transistors with highly stable logic circuit operations. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 5, 3378–3383 (2023).

Rodriguez-Lopez, O. et al. Flexible a-IGZO TFT-based circuit for active addressing in neural stimulation electrode arrays. Adv. Mater. Technol. 8, 2301046 (2023).

Chen, Z., Lan, L. & Peng, J. Approaching subthreshold-swing limit for thin-film transistors by using a giant-dielectric-constant gate dielectric. RSC Adv. 9, 27117–27124 (2019).

Kelly, A. G. et al. All-printed thin-film transistors from networks of liquid-exfoliated nanosheets. Science 356, 69–73 (2017).

Hwang, J. Y., Hong, M. T., Yun, E. J. & Bae, B. S. Analog-to-digital converter with oxide thin-film transistors. J. Inform. Display 17, 79–85 (2016).

Heo, K.-J., Lee, J.-Y., Tarsoly, G. & Kim, S.-J. Multi-functional molybdenum oxide doping to improve the electrical characteristics of indium oxide thin film transistors. Electron. Mater. Lett. 21, 9–21 (2025).

Mazumdar, S., Nyaypati, M., Sambandan, S. & Bhattacharyya, A. J. Cadmium sulfide nanocrystal sensitized vertically aligned titanium dioxide rods for large area image sensors on 3-D substrates. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 4, Q119–Q123 (2015).

Naqi, M., Kim, B., Kim, S. W. & Kim, S. Pulsed gate switching of mos2field-effect transistor based on flexible polyimide substrate for ultrasonic detectors. Adv. Funct.l Mater. 31, 2007389 (2021).

Pujar, P. et al. Adv. Funct. Materi. 31, 2103748 (2021).

Luo, Z. et al. Sub-thermionic, ultra-high-gain organic transistors and circuits. Nat. Commun. 12, 1928 (2021).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Kresse, G. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Kang, Y. et al. APL Materials, 2.2014.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (Grant numbers: 2022R1A2C2008273). This work was also supported by Korea Evaluation Institute of Industrial Technology grant funded by the Korean Government Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (RS-2022-00155706). This work was supported by the Technology Innovation Program(or Industrial Strategic Technology Development Program(RS-2025-02308064, Development of High-Performance Oxide Backplane 2G Panel Technology for Low-Power MicroLED Displays) funded By the Ministry of Trade Industry & Energy(MOTIE, Korea). J.K. acknowledges support from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (RS-2024-00458251). Additional support was provided by the Technology Innovation Program (RS-2025-25454815) funded by the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (MOTIE, Korea).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.-M.P., S.C.J. and M.S. contributed equally to this work. Y.K., J.K., and H.-S.K. supervised the project. J.-M.P., S.C.J. and M.S. conceived and designed the experiment. J.-M.P., M.S. and K.-S.A. characterized device performance. S.C.J. helped to fabricate and characterize all films. J.-M.P., S.C.J. and M.S. analyzed the experimental data. Y.K. do the Density functional theory calculations. J.-M.P., S.C.J., M.S. and Y.K. wrote the manuscript and revised the manuscript. K.-S.A., J.K. and H.-S.K provided comments on the manuscript. All authors discussed the result and the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Park, JM., Jang, S., Song, M. et al. Suppressing Hydrogen-related Trap States in indium–gallium–zinc oxide thin-film transistors for High-Mobility and Low-Power Oxide Electronics. Commun Mater 6, 280 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-01003-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-01003-x