Abstract

A marsh-fronted seawall is a hybrid nature-based coastal protection solution because it attenuates wave energy, reduces erosion, and provides ecosystem services. However, we still have a limited understanding of how to quantify the marsh wave attenuation benefits for economic analysis. Here, we incorporate a prediction of wave attenuation that accounts for species-specific morphology and structural stiffness into a 1-D wave model and validate it with field measurements. Our results show that the wave attenuation varies by a factor of two across different vegetation species. Further, we performed a benefit-cost analysis, in which the economic benefits represent the environmental services value and avoided seawall heightening cost that would otherwise be required to deliver the same overtopping rate without vegetation. We applied the model to a real-world, marsh-fronted seawall design at Juniper Cove, Massachusetts. Although the benefit of marsh-fronted seawalls is sensitive to discount rate, they have benefit-cost ratios greater than one, indicating that it is an economically justified nature-based solution. Further, we found that wave attenuation and benefit-cost ratio are more sensitive to water depth than wave height. Our study demonstrates the importance of considering the coastal protection of marshes and economic benefits in one framework.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Each year, coastal storms threaten hundreds of millions of people1,2,3, disrupt transportation networks4,5, and produce billions of dollars in damage6,7. In 2022, in the United States alone, coastal storms have resulted in economic losses over USD$165 billion8. These costs are projected to increase with sea level rise and with more frequent and more severe storms promoted by climate change9. It was projected under the RCP8.5 global climate scenario that by 2100, global total assets exposed to coastal flooding will reach USD$14 trillion, which is equivalent to 20% of global GDP10. Without adaptation to the climate, humanity would experience annual economic losses of 0.3–9.3% of global GDP11,12,13. Therefore, climate-resilient solutions for coastal protection are pressing14.

Historically, the coast has been protected with gray infrastructure, such as seawall, which consists mostly of concrete15. The construction and maintenance of gray infrastructure are costly, and the increased storm intensity due to climate change will drive upgrades and repairs to maintain the desired level of coastal safety16,17. Gray infrastructure is designed to minimize overtopping and associated flooding. However, these hard structures are not efficient in dissipating wave energy and mostly reflect it, which poses a threat to nearby less protected coastlines18,19.

In contrast, natural shorelines, including marsh20,21,22, mangrove21,23, seagrass22,24, kelp beds22, coral reef21,22, oyster reef25,26, and sandy beach22,27, attenuate wave energy21,22. The nature-based hybrid solution of maintaining a marsh in front of a seawall provides flood risk reduction28,29, reduced wave load on the seawall30, and many environmental service benefits31. These natural coastlines dynamically adapt to sea level rise32, enhance resilience to erosion20, promote carbon sequestration33, and provide important ecosystem services34. For example, the reduced energy intensity and plant canopy structure of salt marshes provide shelter for fish nursery habitat35. Globally, there is growing interest in ecosystem restoration, such as the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Hazard Mitigation Assistance grant program in the United States36, the Natural Restoration Law in the European Union37, and the Nature-based Solutions Asian Hub in Asia38. Marsh-fronted seawalls might deliver the same level of desired coastal protection more economically, with lower construction and maintenance costs than gray infrastructure alone39. Recognition that existing marsh habitats can improve the performance of a seawall40 motivates the conservation and restoration of marshland for its natural coastal defense functions41,42.

Previous studies have demonstrated that salt marshes provide protection against wave action, storm surge, and erosion20,43,44. Wave attenuation by flexible and rigid vegetation has been quantified in the field45,46 and in the laboratory for specific vegetation species47,48,49,50. The effect of vegetation drag on wave propagation has been primarily modeled by calibrating an empirical drag coefficient that is fitted with observations of wave attenuation by real45,51,52 and artificial model plants53. The use of empirical drag coefficients lacks predictability for uncalibrated conditions, including changes in the vegetation characteristics between sites or due to seasonal growth patterns.

To provide predictability beyond a site-specific drag coefficient, a one-dimensional (1-D) wave attenuation model was developed based on a first-principles description of plant reconfiguration, which is the movement of flexible plants in response to wave velocity. The waves were assumed to travel perpendicular to the seawall. The vegetation drag was computed based on plant morphology, including the geometry and structural stiffness of the stem and leaves49. The evolution of wave height as the wave progresses toward a seawall was evaluated by considering the processes of dissipation by vegetation drag, shoaling, depth-induced wave breaking, and bed friction.

With the predicted wave height at the toe of the seawall, empirical equations in EurOtop, 201854 were used to compute the overtopping rate (Eq. 5.12, 5.16, 5.17, 5.20). The overtopping rate is also a function of freeboard \({R}_{c}\), which is the distance between the still-water level and the highest point of the seawall (Fig. 1). The coastal protection value of marshes was quantified by comparing the freeboard required to achieve the same targeted overtopping rate with and without marsh (see Methodology). The reduction in freeboard represents the reduction in seawall height that is made possible by including a marsh.

a Schematic of marsh-fronted vertical seawall annotated with benefit and cost components considered in the benefit-cost analysis (BCA). b Summary of model parameters based on Vuik et al.51.

A benefit-cost analysis (BCA) was used to evaluate whether the inclusion of a marsh in front of an existing seawall would be an economically justified alternative to heightening an existing seawall31,55,56,57,58. The BCA assumed a base case of an existing seawall without a fronting marsh. This illustrated the economic trade-off between restoring a degraded marshland, which reduces wave energy at an existing seawall or constructing additional seawall height on an existing seawall to achieve the same overtopping rate, i.e., same flood protection. In this way, the value of coastal protection contributed by a marsh can be quantified by the cost savings associated with the avoided seawall heightening59.

A marsh-fronted seawall has two additional categories of benefit. First, the marsh delivers important environmental services, including habitat, aesthetics, and improved water quality, the values of which have been compiled by FEMA31. Second, the reduction in wave energy can reduce erosion, especially at the toe of the seawall60. Because methods for estimating the volume of reduced erosion are not available in the literature, the present study did not account for reduced erosion in the BCA. The cost of marsh planting61 and marshland stabilization62 are the two categories of costs associated with the marsh.

Based on the range of values collected from literature (see Supplementary Notes 1), each monetized benefit and cost was organized into low, medium, and high estimates56,57 (see Methodology). For the seawall construction costs (used to evaluate the benefit of avoided seawall heightening), low and high estimates represent values in rural and urban settings, respectively, with a medium value computed as the median representative values found in literature59. The low, medium, and high estimates for all other categories were the lowest, median, and highest representative values found in literature21,31,59,61,63,64,65.

The benefit-cost ratio (BCR) computes the ratio of the total monetized benefits and costs. The BCR analysis was applied to the marsh-fronted seawall configuration shown in Fig. 1. Sensitivity to vegetation type and seasonality, storm condition, and discount rate were considered. To provide a specific example, the BCR analysis was applied to a real-world case study of the Columbus Avenue Seawall Reconstruction Project at Juniper Cove, Salem, Massachusetts, United States, to determine whether restoring the marsh in front of the seawall is economically justified (see Methodology).

Results

Model validation with field data

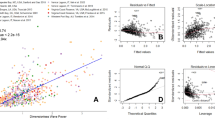

Reported plant morphology, rigidity66, and shoot density (shoots per bed area) were used to predict the evolution of wave height through marshes at two sites, Bath and Hellegat in the Netherlands, vegetated with Scirpus maritimus and Spartina anglica, respectively (see Supplementary Notes 2)51. Since the number of leaves per stem (\({N}_{l}\)) was not reported, a range of values was chosen to represent winter conditions, \({N}_{l}=0,\,2,\,4\) for Bath and \({N}_{l}=0,\,2,\,5\) for Hellegat, with the maximum corresponding to species-specific low values reported in Zhang et al.66, since leaf count is lower under winter conditions. With no calibration, the predicted wave height had excellent agreement with the measured wave height at both sites, with R2 values of 0.88 to 0.90 at Bath and 0.71 to 0.92 at Hellegat (Fig. 2a), which validated the 1-D wave model. A comparison of model results with and without marsh (solid and dashed blue lines in Fig. 2b) indicated that a marsh only 55 m wide led to 32% more wave height reduction than the scenario without vegetation, demonstrating that even small widths of marsh, typical for urban settings, can have a significant impact. Note that the reported wave conditions did not incur any stem breakage51. Under severe storms, stem breakage could be accounted for within the model by reducing a fraction of the stems to a typical breaking height that can be empirically characterized67.

a Predicted wave height validated against field data measured at Bath and Hellegat. Since the number of leaves per stem (\({N}_{l}\)) was not reported, error bars reflect range of leaf number expected for winter conditions (\({N}_{l}=0\) to \(4\)) at Bath (Scirpus maritimus) and (\({N}_{l}=0\) to \(5\)) at Hellegat (Spartina anglica). b Wave height evolution predicted with and without vegetation for Hellegat site with \({N}_{l}=2\). The location of wave height sensors is indicated as S1, S2, S3, and S4. Vegetation had three distinct zones of shoot density, indicated by gradations in green color. c, d Contribution of individual wave dissipation mechanisms (c) without and (d) with vegetation.

The model provided insights into the relative importance of each wave dissipation mechanism: work against vegetation drag66, shoaling68, depth-induced wave breaking69, and bed friction70. Without vegetation (Fig. 2c), wave breaking (yellow line) was the primary mechanism of wave energy dissipation. In contrast, with vegetation (Fig. 2d), vegetation drag (blue line) was the dominant mechanism, and dissipation through wave breaking (yellow line) was reduced to levels comparable to bed friction (purple line).

Wave attentuation depends on plant species

The wave reduction achieved by six healthy and two dormant marsh species, spanning a range of stem and leaf flexibility and dimensions, were compared using the marsh-fronted seawall configuration (Fig. 1). The cases with dormant plant characteristics (dotted lines in Fig. 3a and triangles in Fig. 3b) were based on the winter plant parameters at Bath and Hellegat between locations S3 and S4, which were validated in Fig. 2a. The morphology, stiffness, and shoot density (shoots per bed area) are shown in Supplementary Notes 3. The additional wave reduction achieved by each species was defined relative to the site without vegetation, but the same bathymetry (Fig. 3a). The wave height reduction was strongly correlated with the stem stiffness \({E}_{s}{I}_{s}\) (Fig. 3b), defined by the product of stem elastic modulus (\({E}_{s}\)) and bending moment of inertia (\({I}_{s}\)). Specifically, the invasive species Phragmities australis (blue line and circle) achieved the greatest additional wave attenuation due to its high structural stiffness for both stems and leaves (see Supplementary Notes 3). In the United States, Phragmities australis is often undesirable for ecological reasons, as it outcompetes native species and reduces nutrient availability at the site71,72, but its wave attenuation performance may make it desirable in some situations. Scirpus marquetry (yellow line and circle) provided the least wave attenuation due to its small stem diameter, giving it the lowest stiffness.

Additional wave height reduction compared to site without vegetation achieved by six healthy and two dormant marsh species a at different vegetation width, and b additional wave attenuation with 40-m marsh width as a function of stem rigidity. Triangles are dormant conditions for Spartina anglica and Scirpus maritimus. Stem rigidity is defined by the elastic modulus \({E}_{s}\), and bending moment of inertia \({I}_{s}.\). This figure corresponds to the marsh-fronted seawall configuration in Fig. 1, with water depth at the toe of seawall \({h}_{t}\)= 3 m. Other parameter values given in Fig. 1b were adopted from Vuik et al.51.

Moreover, our model predicted healthy plants provide 8% to 17% more wave attenuation than dormant plants (compare solid and dotted lines of black and orange lines in Fig. 3a), which was due to a higher number of leaves per stem, as well as higher stem stiffness \({E}_{s}{I}_{s}\) of healthy plants (black and orange circles in Fig. 3b) than dormant plants (black and orange triangles in Fig. 3b). This was consistent with seasonal variation discussed in Garzon et al.52, who showed that marshes provided 15% to 30% more reduction in wave height during fall than in winter.

Benefit-cost ratio for seawall fronted with marsh with sensitivity analysis

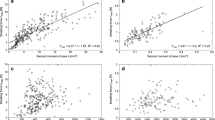

The benefit-cost ratio was estimated for the marsh-fronted seawall configuration (Fig. 1) with vegetation widths of 0 to 100 m, assuming the seawall already exists. The base case was defined with offshore wave height \({H}_{0}=\) 1.5 m, water depth \({h}_{t}=\) 3 m, plant species Spartina alterniflora, 50 years useful project life, and 2.5% discount rate, which is the rate given in the 2023 United States Water Resource Development Act73. The low category of benefit and cost values was used, because this yielded the lowest BCR values, and thus represented the most conservative assessment. A detailed breakdown of the BCA is shown in Supplementary Notes 4 for the base case with 20 m vegetation width, which corresponds to the orange line in Fig. 4c at 20 m vegetation width. Considering a wide range of conditions, the benefit-cost ratio was predominantly greater than one, indicating that marsh-fronted seawalls are an economically justified nature-based solution.

The base case is the marsh-fronted seawall in Fig. 1 with offshore wave height \({H}_{0}=\) 1.5 m, water depth at the seawall toe \({h}_{t}=\) 3 m, Spartina alterniflora plants, 50-year project life, and 2.5% discount rate73. The first sensitivity analysis varied water depth at the seawall toe, \({h}_{t}\), for which a shows wave height at the seawall toe, and b shows percentage of total monetized benefit contributed by avoided seawall heightening (solid line) and environmental services (dashed line), and c shows associated BCR values. d Sensitivity of BCR to storm condition, with the offshore wave height set to the shallow-water wave breaking limit \({H}_{0}=0.88{h}_{t}\). e Sensitivity of BCR to vegetation species. f Sensitivity of BCR to discount rate.

Four cases were considered to explore the sensitivity of BCR to storm conditions (defined by water depth at toe of seawall, \({h}_{t}\), and offshore wave height, \({H}_{0}\)), vegetation species, and choice of discount rate (Fig. 4). The first sensitivity test considered the water depth at the toe of the seawall (Fig. 4a–c). As water depth increases, the vegetation occupies a smaller fraction of the water column, so that the influence of vegetation drag on water motion decreases, which, in turn, decreases the wave dissipation. Thus, as water depth increases, a larger wave height reaches the toe of the seawall (Fig. 4a). The combination of greater water depth with a larger wave height reaching the seawall necessitates a higher seawall to prevent overtopping. Consequently, as water depth increases, the potential reduction in seawall height is diminished (Fig. 4b), reducing the monetized benefit of including a marsh (Fig. 4b). As a result, the BCR is lower for larger water depths (Fig. 4c).

First, note that the BCR for all water depths declines as vegetation width increases (Fig. 4c). Because wave energy loss is proportional to wave height squared, as wave height declines with distance over the marsh, the marginal decrease in wave height per unit marsh width also declines. This is shown by the reducing slope of wave height versus marsh width in Fig. 4a. As a result, the marginal benefit of seawall height reduction also declines, which is reflected in the decreasing BCR (Fig. 4c). Second, note that the BCR curves for the four water depths (four curves in Fig. 4c) converge at large marsh width. Since the environmental service benefits and marsh construction costs are constant per unit marsh width and not a function of water depth, the four curves converge as the marginal benefit from reduced seawall heightening per unit marsh width goes to zero.

The second sensitivity analysis varied both water depth and offshore wave height to compare storm conditions (Fig. 4d). The offshore wave height \({H}_{0}\) was set at its maximum storm value using the shallow-water wave breaking limit for the water depth at the seawall toe, \({h}_{t}\). Specifically, \({H}_{0}=0.88{h}_{t}\). The offshore wave heights (legend in Fig. 4d) were all larger than the base condition \({H}_{0}=1.5\) m shown in Fig. 4c. Again, because wave energy loss is proportional to wave height squared, the greater offshore wave height resulted in higher BCR. Specifically, compare the left-side of Fig. 4c, d, in which the blue, orange, yellow, and purple BCR curves (\({h}_{t}=\) 2, 3, 4, and 5 m, respectively) are each higher in Fig. 4d, for which the offshore wave height is higher. Further, for storm conditions, Fig. 4d again illustrates the decreasing marginal benefit with increasing vegetation width, such that BCR decreases with increasing marsh width. Finally, the BCR lines cross each other at large vegetation widths because, given a larger offshore wave height, there is greater overall potential for avoided seawall heightening benefit.

The third sensitivity test explored the impact of vegetation species and seasonality (Fig. 4e). As shown in Fig. 3, the larger and more rigid Phragmites australis produced the greatest wave attenuation, which is reflected in the highest BCR (blue line and circle). Variation in plant characteristics over a growing season was explored by comparing the average reported stem height and number of leaves per stem for Spartina anglica (solid orange line) with the validated dormant plant parameters from Hellegat between locations S3 and S4 (dotted orange line)51,66. This demonstrated that the seasonality of plant conditions influenced the BCR by roughly a factor of 1.5 (Fig. 4e). However, both plant conditions achieved a BCR above 1.0.

The fourth sensitivity test explored the influence of discount rate (Fig. 4f), considering values from 0% to 11%, which spans typical values applied globally for long-term project evaluations. This includes the United States Water Resources Development Act, which from 1971 to 2024 used 2.25% to 8.875%73,74, the European Commission Impact Assessment Guidelines at 4%75,76, and discount rates for natural assets in land-use planning at 0% to 11%77. The salt marsh establishment and maintenance costs, and the avoided seawall heightening benefit were computed as one-off capital costs at the start of the project, while the environmental services benefits were annual benefits. Higher discount rates penalize long-term environmental services value to a greater degree than near-term net capital costs (salt marsh construction cost minus avoided seawall heightening benefits). As a result, the BCR values were lower for higher discount rates. Moreover, the BCR was more sensitive to a change in discount rate when the discount rate was lower.

BCA case study example

To illustrate the BCA for a real-world example, we considered the Columbus Avenue Seawall Reconstruction project at Juniper Cove, Salem, Massachusetts, United States. The project proposes to raise the seawall height and restore the salt marsh in front of the seawall to improve resilience against coastal flooding78,79. The hydrodynamic conditions for a 10-, 50-, and 100-year storm events, proposed seawall height, and areal extent of each vegetation type were obtained from the project design report78. Since the Juniper Cove site has a mildly curving coastline, a 1-D wave model is appropriate, which assumes that all wave energy is transferred in the cross-shore direction. In the Juniper Cove case study, the wave propagation towards a mildly curved shoreline was analyzed by subdividing it into 10 transects (Fig. 5d), along which the 1-D wave model was applied between the breakwater and the seawall (see Methodology), with assumptions that the marsh is fully established.

Showing a wave height at the seawall, b wave overtopping rate at seawall, and c additional seawall height required such that the seawall without vegetation would achieve the same overtopping rate as the vegetated case. d Location of Transects 1 to 10 ordered from West to East with ArcGIS Pro World Imagery basemap103. e Benefit-cost ratio (BCR) for healthy and dormant vegetation under 10-, 50-, and 100-year storm events evaluated at different discount rates.

The wave height at the seawall is shown in Fig. 5a for cases with healthy vegetation (dashed lines), dormant vegetation (dotted lines), and without vegetation (solid lines) under the three storm conditions. Overtopping rates were computed from wave height at the seawall (Fig. 5b). Without vegetation (solid lines) and with dormant vegetation (dotted lines), overtopping rates along most of the seawall do not satisfy the pedestrian safety level of 0.01 to 0.02 m3 s−1 with \({h}_{t}=\) 1 m, defined in EurOtop, 201854 (horizontal green band in Fig. 5b). However, with healthy vegetation (dashed lines) the safety requirement is satisfied for the 10- and 50-year storms (blue and yellow dashed lines).

For each transect, we calculated the additional seawall height required such that the seawall without vegetation would achieve the same overtopping rate as the vegetated case (Fig. 5c). Since seawalls are typically constructed with a top elevation that is level, the required seawall height was governed by the transect requiring the largest additional seawall heightening. For healthy plants, this corresponded to 1.7 m (Transect 10) for the 10-year storm (blue dashed line), 1.3 m (Transect 6) for the 50-year storm (yellow dashed line), and 1.1 m (Transect 6) for the 100-year storm (orange dashed line). These values were used as the avoided seawall heightening benefit for healthy plants (see Methodology), and this process was repeated for dormant plants. As expected, the BCR of healthy plants (dashed lines) was significantly higher than dormant plants (dotted lines, Fig. 5e). The healthy plants provided 16% to 50% more wave attenuation than dormant plants, which was consistent with the 15% to 30% protection difference between fall and winter plants reported in Garzon et al.52. The dormant plants had similar BCR across the three return periods because the dormant plants provided a similar low degree of wave dissipation across all three storms. The BCR for dormant plants drops below 1.0 for discount rates greater than or equal to 6%, which echoes the strong influence of discount rates on investment decisions based on BCR and the need to consider seasonal variation in vegetation.

Discussion

A model that captures the morphology and rigidity of marsh plants produced good predictions of wave attenuation. The model demonstrated that wave attenuation is sensitive to structural stiffness, plant morphology, and shoot density (Fig. 3)49. While it is a common practice in coastal modeling to describe wave attenuation with drag coefficients calibrated with in situ measurements45,51,52, these drag coefficients are also sensitive to plant morphology and flexibility, and thus may not be accurate for new sites with different vegetation, or even at different seasons at the same site. In contrast, the new model can predict wave attenuation based on site-specific vegetation morphology and species heterogeneity. This enables a quantitative evaluation of year-round coastal protection, capturing seasonal variation associated with growth patterns, which can be used to determine whether temporary additional flood-response measures are needed during specific seasons of the year. However, since it is labor-intensive to collect the necessary vegetation characteristics, there is a need for efficient methods that map vegetation species, plant height, and shoot density. Some recent studies have mapped the spatial distribution of salt marsh species and leaf area index using visual, multispectral, hyperspectral imageries, and Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) data collected by satellites, planes, and unmanned aircraft systems (drones)80,81,82. Point clouds derived from 3-D reconstruction from LiDAR data and Structure from Motion photogrammetry techniques can be used to estimate ground elevation and plant height83,85,85. However, remote sensing methods face significant challenges with acquiring sufficient ground truth data, visual obstructions by dense vegetation canopies, high equipment cost, and high computation cost on large datasets84,85.

The wave attenuation model was used to predict the reduction in wave height achieved by a marsh situated in front of a seawall (Fig. 1). The breakdown of each wave dissipation mechanism (Fig. 2) revealed that the loss of wave energy to work against vegetation drag made the waves less likely to reach breaking conditions69. Because wave breaking generates turbulence and sediment resuspension86,87, a reduction in wave breaking would have the added benefit of reducing resuspension, which should favor sediment retention within the marsh. In addition, because breaking waves generate scouring at coastal infrastructures88, a reduction in wave breaking would also reduce scouring maintenance costs. Because methods for estimating the volume of reduced erosion are not available in the literature, the present study did not account for reduced erosion in the BCA.

The reduced wave height achieved by the marsh allows the height of the seawall to be reduced while achieving the same defense against coastal flooding. The reduction of the seawall height was considered a benefit (reduced cost) in the BCR analysis, which is often used to guide decisions for coastal planning89. The BCR was shown to be sensitive to several factors, including design storm conditions (water depth and offshore wave height), vegetation species and seasonality, and choice of discount rate. However, in most cases BCR > 1.0 supported the conclusion that marsh-fronted seawall is a viable nature-based solution, even in locations for which only a narrow width of marsh is possible.

Since seawall construction cost varies by a factor of 20 between the low and high-value estimates (see Supplementary Notes 4), the monetized benefits from avoided seawall heightening are site-specific. The benefit from avoided seawall heightening would be higher for urban regions that typically have higher labor, material, and administrative costs to build seawalls63. Therefore, site-specific BCA unit costs, such as Supplementary Notes 5 for the Juniper Cove case study, are essential to deliver a meaningful economic analysis.

The seasonality of plants (Fig. 4e) and changes in water depth (Fig. 4c) impacted the BCR by roughly a factor of 1.5 and 2 respectively. Sea level rise would both increase the water depth and decrease the available marsh width due to coastal squeeze, where the seawall acts as a physical barrier that prevents the marshes from migrating inland as the intertidal limits shift landwards90. In Fig. 4a, the effects of sea level rise can be interpreted as a reduced marsh width (leftward shift along the horizontal axis) and an increase in water depth (upward shift along the vertical axis). Designs that consider time horizons associated with significant sea level rise should consider both effects. This would require information on both the local sea level rise, as well as the sediment accretion rate, which together determine the change in intertidal zone width91. Specifically, sustainable marshes require an accretion rate that keeps pace with the rate of sea level rise92,93 with adequate room for horizontal landward expansion93. Otherwise, an additional investment would be needed to build up the land before planting, with earth-moving contributing a high additional cost, which would lower the BCR.

Recall that wave attenuation follows a decreasing marginal influence with increasing marsh width (Fig. 4a), so that the highest BCR occurs approaching zero marsh width (Fig. 4). This limit is obviously infeasible, as a marsh of negligible width cannot survive. Marsh restoration guidelines94 recommend a minimum marsh width of 5 m, and sufficient sediment availability 95 for a marsh to be sustainable. Although the marginal benefit from wave damping decreases with wider marshes, it is desirable to maximize the marshland size for the ecosystem services benefits, which increase with marsh size, while achieving BCR > 1. In reality, the spatial extent of the marsh is not usually a design choice but is constrained by the bathymetry and tidal elevations, which set the intertidal range within which the marsh can exist78.

The BCR outcomes were sensitive to the choice of discount rate, which was especially apparent for the dormant vegetation in the Juniper Cove case study (Fig. 5e). The BCR for dormant plants was less than 1.0 for discount rates greater or equal to 6%. More generally, BCR values vary by more than a factor of two across the range of discount rates between 0% and 11% (Fig. 4f). Therefore, policies that govern the choice of discount rate have a strong influence on the BCR outcome, which directly affects project investment decisions76. In addition to considering the opportunity costs of alternative investment funds or government bond return rates, the discount rate should also reflect how heavily future ecosystem services are valued. One may consider a lower discount rate, knowing that future ecosystem services are important to hedge against climate challenges of rising sea levels and more intensive storms.

The BCR of all nature-based solutions is very sensitive to the value assigned to environmental services. For a marsh-fronted seawall, the environmental services can contribute more than 50% of the total benefits (dashed lines, Fig. 4b). The low and high estimates for environmental services value differ by a factor of two (see Supplementary Notes 4), which introduces uncertainty in the BCR. A systematic framework is needed to value ecosystem services with more certainty. To address this, in February 2024, the Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) under the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) of the United States of America released a first-ever guide for methodologies to quantify ecosystem services in BCA in the United States89. This provided frameworks to identify environmental changes offered by nature-based solutions and to generate a list of the associated benefits to human welfare, such as human physical and mental health, ecological conditions, and economic productivity. The present study provides an example of how ecosystem services can be quantified in the BCA framework. Specifically, the coastal protection benefit of the marsh was framed in terms of the reduction in construction costs associated with a reduced seawall height.

Methodology

Methodology for 1-D wave attenuation model

A one-dimensional model oriented perpendicular to the shoreline was used to predict the wave amplitude, \({a}_{w}\), at the seawall. The wave height was assumed to be twice the wave amplitude, \(H=2{a}_{w}\). The change in wave amplitude was calculated for a sequence of spatial steps (\(\Delta x\)) marching from an offshore location to the seawall96. The amplitude at spatial step \(i+1\) was calculated from the amplitude at spatial step \(i\) and the action of four mechanisms that influence wave energy, each defined at spatial step \(i\): (1) loss to vegetation drag (\({K}_{{{\rm{v}}}}\)), (2) shoaling (\({K}_{{{\rm{sh}}}}\)), (3) depth-induced wave breaking (\({K}_{{{\rm{br}}}}\)), and (4) loss to bed friction (\({K}_{{{\rm{bed}}}}\)).

The model assumed linear waves, with period \(T\) and angular frequency \(\omega =2\pi /T\). The wave number \(k\) and wavelength \(\lambda =2\pi /k\) were defined by the water depth \(h\) and the dispersion relationship

with gravitational acceleration \(g=9.81\) ms−1.

Wave amplitude change due to vegetation drag, \({{{\boldsymbol{K}}}}_{{{\bf{v}}}}\)

Flexible plants, such as marsh grass, move in response to wave forcing, which is called reconfiguration. Reconfiguration reduces the hydrodynamic drag generated by individual plants. The influence of reconfiguration on plant drag, and by extension on wave dissipation, can be described in terms of two non-dimensional parameters66, the wave Cauchy number Ca, and the length ratio L. These parameters are defined separately for leaves and stems, denoted by subscript \(l\) and \(s\), respectively. First, the Cauchy number is the ratio of hydrodynamic drag to plant element rigidity, which is described in terms of the plant geometry (leaf length \({l}_{l},\) width \(b\), and thickness \(d\), and stem length \({l}_{s}\) and diameter \(D\)), and the plant rigidity, defined by Young’s modulus (\({E}_{l}\) and \({E}_{s}\)) and the bending moment of inertia (\({I}_{l}=b{d}^{3}/12\), \({I}_{s}=\pi {D}^{4}/64\)).

The reference wave velocity, \({U}_{w}\) (ms−1), is defined at the top of the canopy, or at the water surface if the plants are emergent. The wave orbital velocity within the plant canopy is assumed to be the same as an unobstructed linear wave, which is reasonable (within 10% from the top of the plant) for most coastal marsh49, such that

in which \(z=\left\{\begin{array}{c}{l}_{l},\\ h,\end{array}\right.\) \(\begin{array}{l}{{\rm{if}}}\, {{\rm{marsh}}} \,{{\rm{is}}} \, {{\rm{submerged.}}}\\ {{\rm{if}}}\, {{\rm{marsh}}}\, {{\rm{is}}}\, {{\rm{emergent.}}}\end{array}\)

Second, the length ratio, \(L\), is the ratio of the plant element length (leaf or stem) to the wave orbital excursion \({A}_{w}={U}_{w}/\omega\),

The coefficient of wave dissipation by vegetation is Eq. 14 in Zhang et al.66, which has been validated against field measurements, as reported in Fig. 8 of Zhang et al.66.

This defines the stepwise reduction in wave amplitude attributed to vegetation \({K}_{{\rm{v}}}\) (as in Eq. 1)96.

The wave drag coefficient (\({C}_{D,l}\) and \({C}_{D,s}\)) for leaves and stems is derived from measurements of drag on flat plates and cylinders, respectively, and are functions of the respective Keulegan-Carpenter numbers, \(K{C}_{l}={U}_{w}T/b\) and \(K{C}_{s}={U}_{w}T/D\) (see Supporting Information in Zhang et al.66).

Finally, a shape-factor for leaf \({K}_{l}=1\) and for stem \({K}_{s}={K}_{l}{\left(\frac{{C}_{D,l}}{{C}_{D,s}}\right)}^{\frac{1}{4}}\) was defined by Zhang et al.66 to account for differences in shape that are not reflected in the Cauchy number. A summary of variables used in the calculation of the vegetation coefficient \({K}_{{\rm{v}}}\) is given in Table 1.

Wave amplitude change due to shoaling, \({{{\boldsymbol{K}}}}_{{{\bf{sh}}}{{{,}}}{{\boldsymbol{i}}}}\)

The group velocity describes the speed of wave energy propagation96. For shallow-water conditions, it is a function of water depth, \(h\).

As water depth decreases toward shore, group velocity decreases, which generally results in an increase in wave amplitude, called shoaling68. Shoaling conserves wave energy (~\({{C}_{g}{a}_{w}}^{2},\)) from which the shoaling coefficient in Eq. 1 can be defined as:

Wave amplitude change due to wave breaking, \({{{\boldsymbol{K}}}}_{{\rm{br}},i}\)

The wave height at which breaking begins, \({H}_{b}\), depends on the wave condition (Miche’s breaking criterion, Table 2)97,98. The wave height in a random sea is assumed to have a Rayleigh-type probability distribution69, with root-mean-square wave height value \({H}_{{rms}}\), for which the probability \({Q}_{b}\) of wave height reaching the breaker height is:

For a random sea, the average rate of wave energy dissipation due to breaking is69:

with \(\alpha\) a scale coefficient of order 1, which we assume to be 1. Conservation of energy requires that the spatial rate of change in wave energy flux equals the energy dissipated by breaking:

The wave energy per surface area is \(E=\frac{1}{8}{{\rm{\rho }}}g{H}_{{rms}}^{2}\). Assuming \({C}_{g}\) is unchanged and the breaking occurs over a distance comparable to or longer than the stepsize, the fraction of the wave energy lost in step \(\Delta x\) is:

For simplicity, we follow the evolution of a single wave height, replacing \({H}_{{rms}}\) by \(H\), but extension to a random sea would be straightforward. For Fig. 2 model validation, \({H}_{{rms}}\) is the reported wave height measured on-site from Vuik et al.51. The wave height was assumed to be twice the wave amplitude \(H=2{a}_{w}\). Since \(E \sim {a}_{w}^{2}\), the breaking coefficient in Eq. 1 is:

Wave amplitude change due to bed friction, \({{{\boldsymbol{K}}}}_{{\rm{bed}},i}\)

The effects of bed friction on wave energy attenuation are not significant51, such that coarse approximations would not significantly affect the precision of wave modeling. The bed was assumed to be a medium size sand, \({d}_{90}=0.5\) mm, with equivalent roughness \({k}_{e}\) = \(2{d}_{90}\), and wave friction factor \(f=0.1{k}_{e}/{A}_{w,{{\rm{bed}}}}\), with \({A}_{w,{{\rm{be}}}d}\) the wave excursion at the bed70. Assuming linear waves and that bed friction is the only mechanism of wave energy dissipation (see details in Section 9.2.2 of Dean & Dalrymple, 199170),

with

Decomposition of contributions from the four energy dissipation mechanisms

From Eq. 1, the contributions of individual wave dissipation mechanisms are not additive in a linear fashion, so the compound effect of all four mechanisms is less than the sum if each component contributes independently. The following steps were used to estimate the fractional contribution of each mechanism to the reduction in wave amplitude over a given step. First, the dissipation coefficients \({K}_{i}\) were recast into a fractional change in amplitude. Specifically, \((\frac{{a}_{w,i}-{a}_{w,i+1}}{{a}_{w,i}})=1-{K}_{i}\), which was used to define the reduction factors

Second, the proportional contribution from each mechanism (\(m={{\rm{v}}},{{\rm{sh}}},{{\rm{br}}},{{\rm{or \ bed}}}\)) to the amplitude reduction is:

Third, since shoaling may increase or decrease wave amplitude, additional steps were needed to define the shoaling reduction factor, \({R}_{{\rm{sh}},i}=1-{K}_{{\rm{sh}},i}^{* }\). Specifically,

The dummy parameter \({d}_{i}\) records whether shoaling increases or decreases wave amplitude.

The modified portion contributed by shoaling is then:

Finally, the wave amplitude reduction contributed by a particular mechanism (with subscript \(m={{\rm{v}}},{{\rm{sh}}},{{\rm{br}}},{{\rm{or\; bed}}}\)) is:

For example, wave amplitude reduction by vegetation drag is:

Salt marsh plant morphology and material properties

For the model validation reported in Fig. 2 in the Results, plant parameters at Bath and Hellegat were reported in Vuik et al.51 and adapted from Zhang et al.66, based on the species descriptions in Vuik et al.51. The vegetation parameters used are shown in Supplementary Notes 2.

For the comparison of wave attenuation achieved by six different marsh species (Fig. 3), plant characteristics were taken from Zhang et al.66, summarized in Supplementary Notes 3.

Value of marsh in terms of reduced seawall height

The coastal protection value of the marsh was quantified in terms of the avoided cost of heightening the seawall. In the absence of a marsh, larger waves reach the seawall, which requires greater seawall height to achieve the same overtopping rate. Engineering relationships provided in EurOtop, 201854 describe the overtopping rate as a function of the freeboard \({R}_{c}\), which is the distance between still-water elevation and the highest point of the seawall structure. The wave height at the toe of the seawall was predicted from the 1-D wave model and used to compute the overtopping rate for different values of freeboard54. The freeboard required for a targeted overtopping rate determined the required seawall height with and without a marsh. For Fig. 4, the marsh was assumed to be fully developed, and the targeted overtopping rate was chosen to be 3 (10−4) m3 s−1, which is the most conservative mean discharge limit defined for pedestrian safety in Table 3.3 of EurOtop, 201854. The overtopping rate depends on the slope of the seawall, and we assume a vertical seawall. Therefore, Eq. 5.17 of EurOtop, 201854 was used.

Methodology for BCA

A BCA was constructed to compare whether placing a marsh in front of an existing seawall would be more economically beneficial than heightening the seawall to deliver the same overtopping rate. The benefits considered were the avoided cost of heightening the seawall and the marshland environmental services. The costs considered were the installation of marsh plugs and the creation and maintenance of the marshland. Both the benefit from avoided seawall heightening and the cost from marshland creation need to be annualized, while the other items can be reported as annual values. The monetized benefits and costs were compared using a BCR:

Present value (\(P\)) of construction costs, marshland earthworks, seawall height reduction, were converted into annualized value99 using Eq. 27.

in which \(n=\) 1 \(=\) number of discounting evaluations per year, \(r\) is the discount rate, and \(t=50\) years of marsh service lifetime, which is the standard period of useful life for coastal wetlands defined by FEMA31. For coastal wetlands, the standard period of useful project life is typically assumed to be 50 years, while an acceptable range is 50 to 100 years, if the land is protected, and a maximum of 100 years represents perpetuity31.

Quantify the value of environmental (ecosystem) services

Environmental services include the ecosystem functions and aesthetic value of the salt marsh31. For example, because waves and currents are reduced within a marsh, they provide important quiescent habitat for aquatic species35. The marsh also improves water quality and protects property value by reducing the impact of coastal storms. Monetary values for these services have been estimated in previous studies, summarized in Table 3. In addition, there is an aesthetic and property value associated with reducing seawall height, as can be achieved with a hybrid marsh-seawall structure, which has not been systematically evaluated and thus cannot be included in this study.

Table 3 summarizes the benefit and cost per 1 m length (along the coastline) of seawall-marsh hybrid infrastructure. Some of the items have a large range of reported values. To simplify the sensitivity analysis, these were sorted into low, medium, and high ranges56,57. A more comprehensive list of literature values for each benefit and cost is tabulated in Supplementary Notes 1. Marsh plantings were assumed to be 0.46 m (18 inches) apart, based on reported practices78, so the planting density was 5 plugs per m2.

A cost breakdown example is shown in Supplementary Notes 4 assuming a 20-m wide (perpendicular to shore) Spartina alterniflora marsh in front of the seawall (as in Fig. 1) and evaluated for a wave period of 5.0 s, offshore wave height of 1.5 m, and 3 m water depth at the toe of the seawall. The marsh facilitated a 1.03 m reduction in seawall height. The resulting BCR values are listed in Supplementary Notes 4.

Money adjustments and monetized components list

The impact of inflation on costs incurred in different years was calculated following the Civil Works Construction Cost Index System (CWCCIS)100. The Composite Index (Table 4) is a weighted average cost index among 19 categories of infrastructure projects. Costs reported in other currencies were converted into $USD using exchange rates on July 1st of each year, representing mid-year, which was also done in Linham et al.59.

Methodology for BCA case study on Juniper Cove

The Columbus Avenue Seawall Reconstruction Project was designed to improve the resilience against coastal flooding at Juniper Cove, Salem, Massachusetts, United States, by raising the seawall height and restoring salt marsh habitat in front of the seawall78,79. This case study focused on the seawall fronted by salt marsh, between 44 Columbus Avenue and the loading dock, measuring approximately 79 m in length (Fig. 6). The 1-D wave model was applied between the breakwater and the seawall.

The existing uneven seawall will be raised by 0.46 to 0.91 m (1.5 to 3 ft) along its length to a level 3.51 m (11.5 ft) NAVD88 elevation. The areal extent of marsh is 1600 m2 and includes regions of Spartina patens and Spartina alterniflora defined in the site plan found on page 21 of the Columbus Avenue Seawall Reconstruction Project Preliminary Design Summary Letter by GZA GeoEnvironmental, Inc78.

1-D wave modeling for Juniper Cove case study

Modeling the wave propagation between the breakwater and the seawall required knowledge of bathymetry, hydrodynamic conditions at the breakwater, and vegetation characteristics. Firstly, the bathymetry of Juniper Cove was obtained from 1887 to 2016 USGS CoNED Topobathy DEM (Compiled 2016): New English, published in 2017 on NOAA101. Ten transects were chosen to subdivide the seawall section along the shore, with labels Transect 1 to Transect 10 from West to East, shown in Fig. 5d. Secondly, the design report used SWAN, a numerical wave model, to forecast the wave conditions at the harbor inlet breakwater under 10-, 50-, and 100-year storms, which were used as the boundary condition for the 1-D wave model. The hydrodynamic conditions for each return period are summarized in Table 5.

Thirdly, the vegetation was chosen based on its preferred tidal regime. Spartina alterniflora would be planted where the ground elevation is between −0.30 and 1.22 m NAVD88 (−1 and 4 ft), while Spartina patens would be planted where the ground elevation is between 1.22 and 1.52 m NAVD88 (4 and 5 ft). To evaluate the effects of plant seasonality on the BCA, the healthy and dormant vegetation properties are shown in Supplementary Notes 6.

BCA for Juniper Cove case study

A detailed breakdown of the unit cost for each construction component was provided in the Engineer’s Cost Estimate sheet in Appendix C of the preliminary design report78. For this case study, the relevant cost components for marsh planting were: (1) High marsh plantings—Spartina patens, (2) Low marsh plantings—Spartina alterniflora, (3) salt marsh sand, (4) sill construction, and (5) salt marsh maintenance. Consistent with the preliminary design report, a 15% contingency cost and a 15% engineering closeout cost were factored into the total cost.

The benefits were the reduced seawall heightening and the environmental services provided by the marsh. The reduced seawall heightening was computed as the additional freeboard needed without vegetation to achieve the same overtopping rate as the vegetation case. The unit benefit of avoided seawall heightening was based on the granite stone wall construction cost listed in the Engineer’s Cost Estimate sheet in Appendix C of the preliminary design report78. A service life of 50 years was assumed. An example of the BCA at 2% discount rate is shown in Supplementary Notes 5.

Data availability

The field data used in the model validation and the hypothetical marsh-fronted seawall configuration are both adopted from Vuik et al.51. The plant parameters were adopted from Zhang et al.66. Data on the Columbus Avenue Seawall Reconstruction project at Juniper Cove were adopted from Taylor & Smith78 and the bathymetry of the site is accessed from 1887-2016 USGS CoNED Topobathy DEM (Compiled 2016): New English, published in 2017 on NOAA101. Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated during the current study.

Code availability

The codes for 1-D wave modeling and BCA are both written in MATLAB (Version 23.2.0 R2023b). The code for 1-D wave modeling is available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13372875102. Any additional code is also available from the corresponding author on request.

Change history

08 December 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03061-y

27 November 2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01918-2

References

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2022: impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. contribution of working group ii to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. (2022).

McGranahan, G., Balk, D. & Anderson, B. The rising tide: assessing the risks of climate change and human settlements in low elevation coastal zones. Environ. Urban 19, 17–37 (2007).

Kunze, S. & Strobl, E. A. The global long-term effects of storm surge flooding on human settlements in coastal areas. Environ. Res. Lett. 19, 024016 (2024).

Jacobs, J. M. et al. Chapter 12: Transportation. Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: the fourth national climate assessment, volume II. https://nca2018.globalchange.gov/chapter/12/ (2018).

Martello, M. V. & Whittle, A. J. Estimating coastal flood damage costs to transit infrastructure under future sea level rise. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 137 (2023).

Hallegatte, S., Green, C., Nicholls, R. J. & Corfee-Morlot, J. Future flood losses in major coastal cities. Nat. Clim. Chang 3, 802–806 (2013).

Kirezci, E., Young, I. R., Ranasinghe, R., Lincke, D. & Hinkel, J. Global-scale analysis of socioeconomic impacts of coastal flooding over the 21st century. Front. Mar. Sci. 9, 1024111 (2023).

NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI). In: U.S. Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters. Available at. https://doi.org/10.25921/stkw-7w73 (2024).

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Hurrican costs. NOAA office for coastal management (2023).

Kirezci, E. et al. Projections of global-scale extreme sea levels and resulting episodic coastal flooding over the 21st Century. Sci. Rep. 10, 11629 (2020).

Hinkel, J. et al. Coastal flood damage and adaptation costs under 21st century sea-level rise. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 3292–3297 (2014).

Pycroft, J., Abrell, J. & Ciscar Martinez, J. C. The global impacts of extreme sea-level rise: a comprehensive economic assessment. Environ. Resour. Econ. (Dordr). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-014-9866-9 (2015).

Asuncion, R. C. & Lee, M. Impacts of sea level rise on economiic growth in developing Asia. https://doi.org/10.22617/WPS178618-2 (2017).

Vallejo, L. & Mullan, M. Climate-resilient infrastructure: getting the policies right. In: OECD Environment Working Papers 121, (2017).

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE). Shore protection manual volume II. (1984).

Hummel, M. A., Griffin, R., Arkema, K. & Guerry, A. D. Economic evaluation of sea-level rise adaptation strongly influenced by hydrodynamic feedbacks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, 2025961118 (2021).

Singhvi, A., Luijendijk, A. P. & van Oudenhoven, A. P. E. The grey – green spectrum: A review of coastal protection interventions. J. Environ. Manag. 311, 114824 (2022).

Balaji, R., Sathish Kumar, S. & Misra, A. Understanding the effects of seawall construction using a combination of analytical modelling and remote sensing techniques: Case study of Fansa, Gujarat, India. Int. J. Ocean Clim. Syst. 8, 153–160 (2017).

Waryszak, P., Gavoille, A., Whitt, A. A., Kelvin, J. & Macreadie, P. I. Combining gray and green infrastructure to improve coastal resilience: lessons learnt from hybrid flood defenses. Coast. Eng. J. 63, 335–350 (2021).

Möller, I. et al. Wave attenuation over coastal salt marshes under storm surge conditions. Nat. Geosci. 7, 727–731 (2014).

Narayan, S. et al. The effectiveness, costs and coastal protection benefits of natural and nature-based defences. PLoS One 11, e0154735 (2016).

Morris, R. L., Konlechner, T. M., Ghisalberti, M. & Swearer, S. E. From grey to green: efficacy of eco-engineering solutions for nature-based coastal defence. Glob. Change Biol. 24, 1827–1842 (2018).

Horstman, E. M. et al. Wave attenuation in mangroves: a quantitative approach to field observations. Coast. Eng. 94, 47–62 (2014).

Paul, M., Bouma, T. J. & Amos, C. L. Wave attenuation by submerged vegetation: combining the effect of organism traits and tidal current. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 444, 31–41 (2012).

Xu, W. et al. Review of wave attenuation by artificial oyster reefs based on experimental analysis. Ocean Eng. 298, 117309 (2024).

Morris, R. L. et al. The application of oyster reefs in shoreline protection: are we over-engineering for an ecosystem engineer? J. Appl. Ecol. 56, 1703–1711 (2019).

Meyer, R. E., Strikwerda, J. C. & Vanden-Broeck, J.-M. Notes on wave attenuation on beaches. Wave Motion 17, 11–31 (1993).

Vuik, V., Borsje, B. W., Willemsen, P. W. J. M. & Jonkman, S. N. Salt marshes for flood risk reduction: quantifying long-term effectiveness and life-cycle costs. Ocean Coast. Manag. 171, 96–110 (2019).

Marin-Diaz, B. et al. Using salt marshes for coastal protection: effective but hard to get where needed most. J. Appl. Ecol. 60, 1286–1301 (2023).

Rosenberger, D. & Marsooli, R. Benefits of vegetation for mitigating wave impacts on vertical seawalls. Ocean Eng. 250, 110974 (2022).

Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). FEMA Ecosystem Service Value Updates. (2022).

Schuerch, M. et al. Future response of global coastal wetlands to sea-level rise. Nature 561, 231–234 (2018).

Chmura, G. L., Anisfeld, S. C., Cahoon, D. R. & Lynch, J. C. Global carbon sequestration in tidal, saline wetland soils. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 17 (2003).

Jordan, P. & Fröhle, P. Bridging the gap between coastal engineering and nature conservation?: a review of coastal ecosystems as nature-based solutions for coastal protection. J. Coast. Conserv. 26, 4 (2022).

Barbier, E. B. et al. The value of estuarine and coastal ecosystem services. Ecol. Monogr. 81, 169–193 (2011).

Smith, G. & Vila, O. A national evaluation of state and territory roles in hazard mitigation: building local capacity to implement fema hazard mitigation assistance grants. Sustainability 12, 1–18 (2020).

Hering, B. D. et al. Securing success for the nature restoration law. Science 382, 1248–1251 (2023).

International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Nature-based solutions Asian Hub launches to accelerate uptake in the region. Available at. https://www.iucn.org/news/202309/nature-based-solutions-asian-hub-launches-accelerate-uptake-region (2023).

Sutton-Grier, A. E., Wowk, K. & Bamford, H. Future of our coasts: the potential for natural and hybrid infrastructure to enhance the resilience of our coastal communities, economies and ecosystems. Environ. Sci. Policy 51, 137–148 (2015).

van Zelst, V. T. M. et al. Cutting the costs of coastal protection by integrating vegetation in flood defences. Nat. Commun. 12, 6533 (2021).

Arkema, K. K. et al. Coastal habitats shield people and property from sea-level rise and storms. Nat. Clim. Chang. 3, 913–918 (2013).

Spalding, M. D. et al. The role of ecosystems in coastal protection: adapting to climate change and coastal hazards. Ocean Coast. Manag. 90, 50–57 (2014).

Borsje, B. W. et al. How ecological engineering can serve in coastal protection. Ecol. Eng. 37, 113–122 (2011).

Gedan, K. B., Kirwan, M. L., Wolanski, E., Barbier, E. B. & Silliman, B. R. The present and future role of coastal wetland vegetation in protecting shorelines: answering recent challenges to the paradigm. Clim. Change 106, 7–29 (2011).

Garzon, J. L., Maza, M., Ferreira, C. M., Lara, J. L. & Losada, I. J. Wave attenuation by Spartina saltmarshes in the Chesapeake bay under storm surge conditions. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 124, 5220–5243 (2019).

Jadhav, R. S., Chen, Q. & Smith, J. M. Spectral distribution of wave energy dissipation by salt marsh vegetation. Coast. Eng. 77, 99–107 (2013).

Maza, M. et al. Large-scale 3-D experiments of wave and current interaction with real vegetation. Part 2: experimental analysis. Coast. Eng. 106, 73–86 (2015).

van Veelen, T. J., Fairchild, T. P., Reeve, D. E. & Karunarathna, H. Experimental study on vegetation flexibility as control parameter for wave damping and velocity structure. Coast. Eng. 157, 103648 (2020).

Zhang, X. & Nepf, H. Wave-induced reconfiguration of and drag on marsh plants. J. Fluids Struct 100, 103192 (2021).

Baker, S., Murphy, E., Cornett, A. & Knox, P. Experimental study of wave attenuation across an artificial salt marsh. Front. Built. Environ. 8 (2022).

Vuik, V., Jonkman, S. N., Borsje, B. W. & Suzuki, T. Nature-based flood protection: the efficiency of vegetated foreshores for reducing wave loads on coastal dikes. Coast. Eng. 116, 42–56 (2016).

Garzon, J. L., Miesse, T. & Ferreira, C. M. Field-based numerical model investigation of wave propagation across marshes in the Chesapeake Bay under storm conditions. Coast. Eng. 146, 32–46 (2019).

Houser, C., Trimble, S. & Morales, B. Influence of blade flexibility on the drag coefficient of aquatic vegetation. Estuaries Coast 38, 569–577 (2015).

EurOtop. EurOtop manual on wave overtopping of sea defences and related structures. www.overtopping-manual.com (2018).

Scodari, P. National economic development procedures manual overview. http://www.iwr.usace.army.mil/index.htm (2009).

Thomas, V. & Chindarkar, N. The Picture from Cost-Benefit Analysis. in Economic Evaluation of Sustainable Development 63–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-6389-4_3. (Springer Singapore, 2019).

Wang, J. J., Li, X. Z., Lin, S. W. & Ma, Y. X. Economic evaluation and systematic review of salt marsh restoration projects at a global scale. Front. Ecol. Evol. 10, 865516 (2022).

URS Group Inc. BCA Reference Guide (2009).

Linham M., Green C., Nicholls R. Costs of adaptation to the effects of climate change in the world’s large port cities. Work stream 2, Report 14 of the AVOID programme (AV/WS2/D1/R14). Available online at www.avoid.uk.net (2010).

Powell, K. A. Toe scour at sea walls subject wave action. Report No. SR 119 (1987).

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE). Appendix C-Planning Analyses North Atlantic Coast Comprehensive Study (NACCS): Resilient adaptation to increasing risk Appendix C-Planning Analyses-i (2015).

Dijkman, J. A Dutch perspective on coastal louisiana flood risk reduction and landscape stabilization Second Interim Report (2007).

Jonkman, S. N., Hillen, M. M., Nicholls, R. J., Kanning, W. & Van Ledden, M. Costs of adapting coastal defences to sea-level rise—New estimates and their implications. J. Coast Res. 29, 1212–1226 (2013).

Oppenheimer, M. et al. Sönke Dangendorf (Germany), Petra Döll (Germany) (2019).

Jin, D., Watson, C., Kite-Powell, H. & Kirshen, P. Evaluating Boston Harbor cleanup: an ecosystem valuation approach. Front. Mar. Sci. 5, 478 (2018).

Zhang, X., Lin, P. & Nepf, H. A simple-wave damping model for flexible marsh plants. Limnol. Oceanogr. 66, 4182–4196 (2021).

Vuik, V., Suh Heo, H. Y., Zhu, Z., Borsje, B. W. & Jonkman, S. N. Stem breakage of salt marsh vegetation under wave forcing: a field and model study. Estuar. Coast Shelf Sci. 200, 41–58 (2018).

Bryan, K. R. & Power, H. E. Wave behaviour outside the surf zone. Sandy Beach Morphodynamics 61–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-102927-5.00004-7 (2020).

Battjes, J. A. & Janssen, J. P. F. M. Energy loss and set-up due to breaking of random waves. Coast. Eng. Proc. 1, 32 (1978).

Dean, R. G. & Dalrymple, R. A. Water wave mechanics for engineers and scientists. vol. 2 (World Scientific, Singapore, 1991).

Gratton, C. & Denno, R. F. Restoration of arthropod assemblages in a Spartina salt marsh following removal of the invasive plant phragmites australis. Restor. Ecol. 13, 358–372 (2005).

Windham, L. & Lathrop, R. G. Jr. Effects of Phragmites Australis (Common Reed) Invasion on Aboveground Biomass and Soil Properties in Brackish Tidal Marsh of the Mullica River, New Jersey. 22, 927–935 (1999).

Congressional Research Service. Discount rates in the economic evaluation of U.S. army corps of engineers projects name redacted specialist in natural resources policy name redacted analyst in natural resources policy. www.crs.gov (2016).

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE). Economic Guidance Memorandum, 24-01, Federal Interest Rates for Corps of Engineers Projects for Fiscal Year 2024. (2024).

Hermelink, A. H. & De Jager, D. Evaluating our future-the crucial role of discount rates in European commission energy system modelling. (2015).

European Commission. European Commission IMPACT ASSESSMENT GUIDELINES. https://ec.europa.eu/smart-regulation/impact/commission_guidelines/docs/iag_2009_en.pdf (2009).

Markanday, A. et al. Determining discount rates for the evaluation of natural assets in land-use planning: an application of the equivalency principle. J. Clean. Prod. 230, 672–684 (2019).

Taylor, L. & Smith, D. A. Preliminary Design Summary Letter—October 2020. https://www.salem.com/sites/g/files/vyhlif12836/f/uploads/columbus_ave_wall_-_design_summary_letter_with_attachments_-_10-21-20.pdf (2020).

Smith, D. A. Preliminary Design Letter—Executive Summary—November 2020. https://www.salem.com/sites/g/files/vyhlif12836/f/uploads/columbus_ave_wall_design_summary_letter_-_executive_summary_11-3-2020.pdf (2020).

Campbell, A. & Wang, Y. High spatial resolution remote sensing for salt marsh mapping and change analysis at fire Island national seashore. Remote Sens (Basel) 11, 1107 (2019).

Belluco, E. et al. Mapping salt-marsh vegetation by multispectral and hyperspectral remote sensing. Remote Sens. Environ. 105, 54–67 (2006).

Figueroa-Alfaro, R. W., van Rooijen, A., Garzon, J. L., Evans, M. & Harris, A. Modelling wave attenuation by saltmarsh using satellite-derived vegetation properties. Ecol. Eng. 176, 106528 (2022).

Hladik, C. & Alber, M. Accuracy assessment and correction of a LIDAR-derived salt marsh digital elevation model. Remote Sens. Environ. 121, 224–235 (2012).

DiGiacomo, A. E. et al. Modeling salt marsh vegetation height using unoccupied aircraft systems and structure from motion. Remote Sens (Basel) 12, 2333 (2020).

Pinton, D., Canestrelli, A., Wilkinson, B., Ifju, P. & Ortega, A. Estimating ground elevation and vegetation characteristics in coastal salt marshes using UAV-based lidar and digital aerial photogrammetry. Remote Sens. (Basel) 13, 4506 (2021).

Green, M. O. & Coco, G. Review of wave-driven sediment resuspension and transport in estuaries. Rev. Geophys. 52, 77–117 (2014).

Voulgaris, G. & Collins, M. B. Sediment resuspension on beaches: response to breaking waves. Mar. Geol. 167, 167–187 (2000).

Bijker, E. W., Asce, M. & De Bruyn, C. A. Erosion around a pile due to current and breaking waves (1988).

Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA). Guidance for assessing changes in environmental and ecosystem services in benefit-cost analysis office of information and regulatory affairs office of management and budget. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/ESGuidance.pdf (2024).

Zhi, L. et al. Seawall-induced impacts on large river delta wetlands and blue carbon storage under sea level rise. Sci. Total Environ. 859, 159891 (2023).

Passeri, D. L. et al. The dynamic effects of sea level rise on low-gradient coastal landscapes: a review. Earth's Future 3, 159–181 (2015).

Kirwan, M. & Temmerman, S. Coastal marsh response to historical and future sea-level acceleration. Quat. Sci. Rev. 28, 1801–1808 (2009).

Fagherazzi, S. et al. Salt marsh dynamics in a period of accelerated sea level rise. J. Geophys. Res. Earth. Surf. 125, (2020).

Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS). Planted tidal marsh. https://www.vims.edu/ccrm/outreach/living_shorelines/design/non_structural/planted_marsh/ (2024).

Stralberg, D. et al. Evaluating tidal marsh sustainability in the face of sea-level rise: a hybrid modeling approach applied to San Francisco Bay. PLoS One 6, e27388 (2011).

Mendez, F. J. & Losada, I. J. An empirical model to estimate the propagation of random breaking and nonbreaking waves over vegetation fields. Coast. Eng. 51, 103–118 (2004).

Southgate, H. N. Wave breaking—a review of techniques for calculating energy losses in breaking waves. (1988).

Lee, K.-H. & Cho, Y.-H. Simple breaker index formula using linear model. J Mar Sci Eng 9, (2021).

Hastings, N. A. J. Financial methods. In: Physical Asset Management: With An Introduction to the ISO 55000 Series of Standards 101–122 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-62836-9_5.

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE). ER 1110-2-1302, Civil Works Construction Cost Index System (CWCCIS). https://Usace.Contentdm.Oclc.Org/Digital/Collection/P16021coll9/Id/2899.

OCM Partners 2023. 1887–2016 USGS CoNED topobathy DEM (Compiled 2016): New England from 2010-06-15 to 2010-08-15. NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information, https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/inport/item/49419 (2016).

Lee, E. I. H. NepfLab/1D-wave-model. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13372875 (2024).

Maxar (2023). Esri ‘World Imagery’ [basemap] Scale 1:1551. Release name maps 2024.R03. Description WV03, Vivid Advanced, Block name: Vivid Advanced Boston US 23Q4.

Google Earth Pro. Juniper Cove, Salem, MA, USA. June 13, 2022. 42°31’57.10“N, 70°52’06.72“W, Eye alt 504 m. Google Image © 2024 Airbus. Accessed: July 12, 2024.

Acknowledgements

E.I.H.L. discloses support for the research of this work from the Schoettler Scholarship Fund awarded by the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The authors also thank Professor Paul Kirshen, Professor Bas Borsje, Dr. Alyssa Novak, Dr. Juliet Simpson, Professor Andrew Whittle, and Dr. Michael Martello for their advice on wave modeling and economic assessment of seawall construction projects.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.I.H.L.: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, data curation, visualization. Writing – original draft, review, and editing. H.M.N.: Conceptualization, methodology, resources, supervision, project administration. Writing – review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Juan L. Garzon and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Martina Grecequet. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, E.I.H., Nepf, H. Marsh restoration in front of seawalls is an economically justified nature-based solution for coastal protection. Commun Earth Environ 5, 605 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01753-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01753-5

This article is cited by

-

Nature-based solutions extend the lifespan of a regional levee system under climate change

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Nature-based Solutions as Building Blocks for coastal flood risk reduction: a model-based ecosystem service assessment

Scientific Reports (2025)