Abstract

The European Union recently adopted ReFuelEU Aviation as a regulation to stimulate the use of alternative aviation fuels. We explore how this affects the climate impact of European aviation and its alignment with notions of successful climate change mitigation. Using stock-and-flow modelling and lifecycle assessment, we analyse the role of hydrogen in decarbonising the aviation system. We find that the adoption of alternative fuels alone does not guarantee successful mitigation, since the resulting temperature change can vary widely (2.2-8.9 millikelvin estimated by 2070) and most scenarios exceed CO2-based targets. Although alternative fuels can greatly reduce CO2 emissions and non-CO2 impacts—with hydrogen-powered aircraft yielding the largest reductions—persistent air traffic growth drives the near-term use of fossil resources and the long-term scale of non-CO2 effects. Therefore, we recommend reassessing aviation climate targets, including the consideration of non-CO2 effects in budget-based targets and stronger incentives to reduce near-term fossil kerosene use.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The air transport sector has become a linchpin of the global economy, but it is also a large contributor to environmental degradation, including climate change1,2. The climate change mitigation required to limit global warming to well below 2 °C, following the Paris Agreement3, is commonly interpreted as reducing greenhouse gas emissions to ‘net zero’ by 2050. In a net-zero scenario, any greenhouse gases emitted through human activities must be ‘offset’, i.e., balanced by an equivalent reduction of greenhouse gases. The International Air Transport Association (IATA) is among industry organisations making a voluntary net-zero commitment, with a considerable reliance on offsetting4. Furthermore, the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) is demonstrating the practical implementation of a climate change mitigation framework through the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA)5. This scheme aims to offset carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from international aviation in excess of a yearly limit, currently defined as 85% of such emissions in 2019. Coverage of climate forcers other than CO2 and lifecycle phases beyond the combustion phase is limited6. CORSIA maintains eligibility criteria aligned with its (limited) scope7, yet the legitimacy of offsetting as an effective climate mitigation tool is challenged by the abundance of low-quality efforts where offset sales do not result in the promised reduction of atmospheric greenhouse gases8,9,10. Broadly, the value of offsets in long-term impact reduction is debatable11,12. As such, the reliance on offsetting and the focus on CO2 at the expense of other climate forcers limits the suitability of these targets to the Paris Agreement.

In addition to offsetting, aviation industry roadmaps focus on measures centred around energy efficiency and substituting fossil kerosene with alternative aviation fuels (AAF)13,14,15,16. Industry actors have set ambitious non-binding targets for these two measures in past decades, but these targets have not been met17. In contrast to these voluntary targets, the European Union (EU) formalised legal requirements in 2023, under the so-called ReFuelEU Aviation initivative18. Following this regulation, EU airports must meet a minimum share of AAF in the fuel they supply, increasing from 2% in 2025 to 70% in 2050. This minimum can be met with sustainable aviation fuels (SAF), defined in the EU as drop-in fuels which meet certain sustainability requirements, or with select non-drop-in alternatives to fossil kerosene. Still, the development of AAF infrastructure faces logistical and technological challenges. Currently, most production methods are based on biomass feedstocks19, but the scale at which these feedstocks can be supplied sustainably is limited20. Therefore, there is great interest in fuels that do not rely on biomass. Hydrogen (H2) can be such a low-impact fuel if obtained from water electrolysis powered by renewable energy21. However, the relatively low volumetric energy density of hydrogen, even in liquid form, presents a challenge for aviation22,23. New technologies are needed to adapt aircraft accordingly, with the market entry of narrow-body hydrogen-powered aircraft expected for 203524. Hydrogen can also be used to produce synthetic drop-in fuels by combining it with a carbon source. This source can come from industrial flue gas, resulting in the delayed emission of fossil carbon, or from biomass or the direct air capture (DAC) of atmospheric CO225,26.

We do not yet know how the adoption of ReFuelEU Aviation will influence the climate impact of future aviation, nor how this future will compare to other targets for climate mitigation. The mitigation of aviation’s climate impacts has been addressed in multiple recent studies27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37, but these cannot necessarily be extrapolated to this context. First, the European scope matters. Understanding that access to aviation is distributed highly unequally38, we argue that a just transition towards sustainable aviation should be understood differently across regions. To illustrate, Åkerman et al.27 present a scenario where, within their definition of successful climate mitigation, per capita air travel is around 3000 km in 2060. Compared to the levels before the COVID-19 pandemic, this represents a tripling of global air travel, yet at the same time almost halving it for the Swedish population27. Assuming that commercial aviation will evolve differently across regions, we avoid describing the sector in terms of global trends.

Second, the analysis of mitigation pathways is inherently tied to how these pathways are conceptualised and understood. For example, we assume that the introduction of AAF—including the potential deployment hydrogen-powered aircraft—is driven by ReFuelEU, with additional measures to eliminate the use of fossil kerosene by 2060. Other studies consider different logic for the deployment of AAF (see Table 1 in Methods) and further mitigation measures. Here, we focus on AAFs, air traffic volumes, and aircraft technology. We do not consider contrail avoidance, although it could be a viable mitigation strategy39. Following the challenges introduced above, we exclude carbon storage and other offsetting techniques, despite their prominence in sectoral roadmaps (see also Discussion). Beyond technical and social dimensions, coverage of environmental dimensions varies too. CO2 is a common focus of aviation climate targets, thereby neglecting other climate forcers. Simultaneously, climate forcers such as nitrogen oxides (NOx) and persistent contrails stemming from aviation have a relatively short-lived effect, which presents a challenge to conventional climate metrics when trying to compare the impact of mitigation scenarios40. As a result, the use of climate metrics for aviation is the subject of active scientific debate41,42. To circumvent this challenge, we compare climate forcers in terms of warming equivalence and introduce two complementary criteria for successful climate change mitigation. First, we assess the ambition to achieve net-zero targets by 2050 by evaluating whether aviation’s contribution to temperature change increases from 2050 to 2070. Second, we use sectoral emission limits to evaluate a proxy warming budget for the coming decades. This allows for a comprehensive discussion of climate impacts, although introducing additional assumptions and limitations (see Discussion and Methods). However, considering impacts from diverse emissions is not sufficient when important sources of such emissions are excluded. Concerning aviation, simplifications which leave out the production phase of fossil kerosene or the use phase of alternative fuels are common29,43, yet such assumptions prevent both a consistent comparison between fuels and a holistic assessment of the sector44. To address this, our analysis integrates a forward-looking approach called prospective lifecycle assessment (pLCA)45,46,47. Such a method enables, for example, the conclusion that the synthesis of synthetic fuels must be powered by a low-carbon energy system in order for the fuel’s climate impacts to be below that of fossil kerosene29,48,49.

With these considerations accounted for, our analysis has a consistent coverage of the aviation system and its resulting climate impact. We describe future European aviation across various socio-technical scenarios, quantifying its evolution and climate impacts by integrating pLCA with a stock-and-flow model. Our analysis includes diverse projections for aircraft technology and air traffic volume. We compare hydrogen-powered aircraft with hydrogen used for drop-in synthetic fuels. In doing so, we deliberately exclude bio-based AAF. This is a deviation from commonly envisioned futures, but has a limited influence on the discussion of overall climate impacts. From this comparison, we observe that per unit air travel, e-fuel uses more hydrogen and has a higher overall impact than hydrogen-powered aircraft. Thereby, fulfilling ReFuelEU in part with hydrogen-powered aircraft results in reductions of yearly hydrogen consumption (13-26%) and CO2 emissions (23-32%), as well as temperature change in 2070 (13–16%). With or without hydrogen-powered aircraft, we find that most scenarios meet our definition of climate neutrality when replacing all fossil kerosene by 2060. However, we are hesitant to qualify this as successful climate mitigation: the target set for CO2 emissions is frequently exceeded and climate neutrality is highly sensitive to our assumptions surrounding non-CO2 impacts. We conclude that, in order to limit the climate impact of European aviation, additional measures must join ReFuelEU and limit the near-term use of fossil fuels. When faced with limits to the pace of decarbonisation, we recommend that such measures focus on demand management.

Results

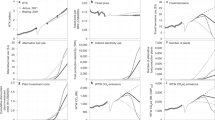

We developed a dynamic system model to estimate possible futures for European aviation. A stock-and-flow model generates fleets of aircraft and fuel infrastructure in order to meet the imposed air traffic volumes (Fig. 1a). Characteristics of the aircraft and fuels introduced are governed by two additional scenario parameters: the advancement of aircraft technology and the evolution of AAF use. The resulting flows are used to scale technology-level LCA data, covering both direct aircraft emissions and emissions across the lifecycles of aircraft and fuel infrastructure. Figure 1 provides an overview of the key parameters, parameter values, and the system boundary. We briefly elaborate on this in the following paragraphs. Detailed descriptions are given the corresponding parts of the Methods section.

a Illustration of the system modelled, comprising lifecycle of the aircraft fleet and the lifecycle of the fuels (lower boxes connected by solid arrows). Key scenario parameters (upper boxes) influence the system (dashed arrows), e.g., the fuel supply adapts to the demands of the aircraft fleet, but also to the prescribed share of alternative aviation fuels (AAF) (see also Supplementary Figs. 1–3). Scenario parameter values are shown with the corresponding colours and line styles used to distinguish scenarios in later figures. b The volume of air traffic in revenue passenger-kilometres (RPK) per year according to four trajectories: high growth (blue line), base growth (grey line, not included in the scenarios presented in the main text), and low growth (orange line), which are based on EUROCONTROL50,51, and degrowth (red line). c The share of AAF in the aviation fuel supply per year as modelled based on ReFuelEU18 (dashed grey line, not included in the scenarios presented in the main text) and how we extend ReFuelEU beyond 2050 (solid black line).

Our definition of European aviation covers departures of scheduled passenger flights from select countries in Europe. We model flights for 2024-2070 by scaling the air traffic patterns of 2019 according to high-level forecasts. We combine EUROCONTROL’s seven-year forecast (up to 2031)50 and the long-term forecast (up to 2050)51. We assume that the long-term year-on-year growth remain representative until 2070, i.e., ‘low growth’ of 0.7%, ‘base growth’ of 1.6%, and ‘high growth’ of 2.2%. Following public support for suppression of commercial aviation as a climate mitigation strategy52,53,54, we also considered an additional ‘degrowth’ trajectory, in which air traffic from 2035 onwards remains constant at 70% of the 2019 demand (Fig. 1b).

Technological improvements in aircraft efficiency vary from a business-as-usual scenario, with progress following historic trends55, to scenarios that include substantial improvements, from ‘optimistic’ expert estimates30, to speculative ‘breakthrough’ advances55. Future hydrogen-powered aircraft are correlated to these general trends, having a lower efficiency under business as usual and a higher efficiency under breakthrough. The latest aircraft generation we include is introduced in 2050, which is why we do not forecast beyond 2070. The fuel supply follows the ReFuelEU Aviation initiative, aiming to reduce fossil kerosene to 30% of the fuel supply by 2050. Although ReFuelEU does not extend past 2050, we consider an extended version of ReFeulEU, in which additional measures lead to the elimination of fossil kerosene by 2060 (Fig. 1c). In our scenarios, the alternatives to fossil kerosene are drop-in e-fuel and non-drop-in liquid hydrogen. Both alternative fuels are produced from electricity, modelled after a grid with a highly ambitious transition towards renewable energy.

Future scenarios

In order to effectively discuss possible futures, the scenario space is reduced from all possible combinations of scenario parameters to a few distinct sets, following principles of compatibility and distinctiveness, as demonstrated by, e.g., Delpierre et al.56 and Langkau et al.57. First, we consider the compatibility of the technology and demand scenario parameters. Transportation efficiency improvement is considered to stimulate demand, limiting its effectiveness as a climate change mitigation measure58. However, experts disagree on how introducing novel aircraft and fuel technologies interacts with measures to limit air traffic growth. Some argue that, with projected growth, the energy demand of aviation could become incompatible with the available energy resources29,36. Others argue that the higher cost associated with AAF will somewhat slow growth but that further limitations would delay the sector’s sustainability transition by diverting financial resources13,14. At least in some European countries, there appears to be public support to increase barriers to flight52,53,54, although political uptake is limited59,60. Based on these perspectives, we decide to positively correlate air traffic demand with the development of aircraft technology, leading to three technology-demand pairs (Fig. 1a). This correlation can be described narratively as follows: ‘In a high-growth scenario, the fuel efficiency imperative of the aviation sector enabled it to maintain its substantial growth, which in turn provided space for revolutionary aircraft technologies to mature. In combination with broad public support, this enabled the construction of AAF infrastructure at rates thought impossible. Conversely, in a degrowth scenario, the aviation sector lacked financial resources, which reinforced the slow development of AAF infrastructure and halted technological breakthroughs. Limited access to clean technology, in turn, limited the air traffic that could be achieved within stringent environmental regulations, further restricting available resources.’ This correlation is introduced in order to effectively explore the scenario space and not to imply a preference over alternative narratives.

Nine scenarios are selected by combining the three sets of demand-technology pairs with three distinct fuel mix scenario values (Fig. 1a). These fuel mixes consist of (1) a baseline, where the share of AAF is not increased, (2) the implementation of an extended version of ReFuelEU Aviation (Fig. 1c), but with no commercial introduction of hydrogen-powered aircraft, meaning that all AAF is modelled as e-fuel, and (3) the extended version of ReFuelEU Aviation, also featuring commercial hydrogen-powered aircraft in future generations, meaning that the share of AAF is met through a combination of liquid hydrogen and e-fuel.

Aircraft fleets

Future aircraft generations are introduced into the fleet with a bottom-up stock-and-flow model: each year, aircraft past retirement (which we assume to be after 22 years of use) are removed from the fleet and—to the extent that additional aircraft are needed in order to meet the current air traffic demand—aircraft from the latest generation are added. This creates an interaction between air traffic demand and the introduction of new technology. In a scenario with consistent high growth, a new generation increases its share of the fleet more rapidly than in a scenario with consistent slow growth—compare the introduction of the 2050 generation (gen. 3) in Fig. 2b and Fig. 2d.

The revenue passenger-kilometers (RPK) provided from 2024-2070, distinguishing generations (gen.) by the colour of the shading. This figure shows scenarios which include hydrogen-powered aircraft (white hatching). In scenarios which do not include hydrogen-powered aircraft, all RPK are satisfied with hydrocarbon-powered aircraft. As long as the evolution of air traffic demand is identical, the distribution of RPK per generation remains the same. a, c, e RPK totals of generations are shown. b, d, f Relative shares of RPK are shown for 2040, 2055, and 2070.

In scenarios which start with a strong decline in air traffic, few new aircraft are required during this period. Once these aircraft need replacing, 22 years after the decline started, we see that once again few new aircraft are introduced—observe the period around 2050 in Fig. 2e, leading to a small share of the 2050 generation in 2055 (Fig. 2f). Conversely, however, the aircraft retiring in the years following the decline were already in the fleet before the decline started. As the overall fleet shrunk, the retirement of this segment represents the turnover of a sizeable portion of the fleet as a whole. This results in the periods of slow replacement being alternated with periods or rapid replacement, to the extent that the share of the 2035 generation (gen. 2) initially increases the fastest for the degrowth scenarios (compare 2040 in Fig. 2b, d to the same year in Fig. 2f). Of course, the simplifications we make mean that such a pronounced ripple effect is not necessarily representative of reality, but this illustrates a possible consequence of prolonged shifts in the air traffic demand.

In scenarios featuring hydrogen-powered aircraft, these are introduced with consideration for the aircraft type and flight destination. We assume that the initial introduction of hydrogen-powered aircraft is limited to intra-European flights serviced by narrow-body aircraft—a segment which represents 48% of air traffic in terms of revenue passenger-kilometres (RPK) (see Table 2 in Methods). Because hydrogen-powered aircraft are introduced to the extent required to meet demand, only a fraction of European airports require hydrogen infrastructure in 2035. However, we do assume that this can extend to all European airports as time goes on, as well as some extra-European destinations after 2050 (see Table 3, as well as associated text, in Methods). With these ambitious assumptions, the share of air traffic powered by hydrogen rapidly grows from around 10% in 2040 to over 60% in 2070 (Fig. 2).

Fuel demand

Figure 3 illustrates how different parameter combinations affect fuel use and hydrogen demand. In the baseline scenarios—where AAF is not scaled up—total fuel demand initially diverges but then stabilises around 2035 with the introduction of future aircraft (Fig. 3a). This shows that demand plays a substantial role in the short term, while the contrast in fuel efficiency of aircraft technology becomes more influential over time. The business-as-usual scenario stabilises fuel use with 0% demand growth, while the breakthrough scenario stabilises fuel use with a year-on-year growth of 2.2%.

Results for 2024-2070 under the nine selected scenarios, which vary the air traffic volume with the level of aircraft (AC) technological improvements (indicated by the line colour: blue, orange, or red) and an evolving fuel mix (indicated by the line style: dashed, dash-dotted, or solid). a Fossil kerosene consumed by aircraft. b AAF consumed by aircraft (saturated lines) and, for scenarios which include hydrogen-powered aircraft, the hydrogen consumed as non-drop-in AAF (desaturated lines). c The hydrogen production required when accounting for the supply chain of both AAF types considered. This panel also indicates 20% of the European Union’s 2030 target hydrogen supply (the total consisting of 10 million tonnes production and 10 million tonnes import)74 (lower dotted black line) and 20% of European hydrogen production in 2050, following a net-zero emissions scenario (the total being 44 million tonnes)21 (upper dotted black line). Note that the scenarios where the share of AAF is not increased (i.e., those represented with a dashed line) remain close to zero in the two lower panels.

In the scenarios following our extended version of ReFuelEU, the required AAF share (Fig. 1c) is achieved by introducing hydrogen-powered aircraft and by replacing fossil kerosene by e-fuel. The combined AAF used across scenarios with or without hydrogen-powered aircraft is therefore similar (Fig. 3b), with some divergence emerging due to differences in the energy demand for hydrogen-powered and hydrocarbon-powered aircraft. Hydrogen-powered aircraft could require less energy per available seat-kilometre (ASK) than their contemporary hydrocarbon-powered counterparts (see Methods). This is why the introduction of hydrogen-powered aircraft reduces the total demand for aviation fuel when assuming breakthrough future technology. In optimistic and business-as-usual scenarios, this is not the case, and introducing hydrogen aircraft increases the total fuel demand. Since ReFuelEU defines a share of AAF, such changes to the total fuel demand influence how much fossil kerosene can be used (Fig. 3a).

Because the initial fleet composition is identical across scenarios, the number of aircraft reaching their retirement age is also the same up to 2046. When combined with the differing energy demands of hydrogen-powered aircraft, this leads to similar use of hydrogen as AAF in 2035-2046 across scenarios (see the desaturated lines in Fig. 3b). Consequently, hydrogen makes up over 50% of the 2042 AAF supply in the degrowth scenario, with a temporary peak of 70% in 2045, while in the high-growth scenario it first exceeds 50% in 2056. This illustrates how future aircraft efficiencies, fleet compositions, and the incentives set for AAF use are all closely related in determining how the sector takes shape.

The total hydrogen required across scenarios also relates to aircraft energy efficiency. However, another dimension to consider here is the efficiency with which hydrogen is used to fuel aircraft. In the production of drop-in e-fuel, hydrogen is first used in a reverse water-gas shift reaction to obtain carbon monoxide (CO) from CO2, which is then combined with additional hydrogen in a Fischer-Tropsch reaction to obtain hydrocarbons. This leads to a consumption of 1.61 MJ hydrogen per 1 MJ of e-fuel. On the other hand, fuelling an aircraft with 1 MJ of liquid hydrogen requires only 1.02 MJ hydrogen, with minor losses in transportation and liquefaction steps (see Methods). As a result, the introduction of hydrogen aircraft always leads to a reduction in the overall hydrogen production required (Fig. 3c). Nonetheless, the hydrogen demand remains substantial across all scenarios. By 2050, hydrogen demand in aviation could exceed 20% of European production following a net-zero emissions pathway21 in both low-demand and high-demand scenarios.

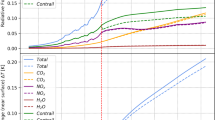

Climate impacts of fuels

Environmental flows of climate forcing agents are added up across the aviation system, spanning the full lifecycle of fuels and aircraft. We use the computational framework of Smith et al.61 to express the combined impact of climate forcers as time-dependent warming-equivalent emissions, using aviation-specific parameters based on Arriolabengoa et al.42. These warming-equivalent emissions are multiplied by the transient climate response to cumulative CO2 emissions62, thereby obtaining the aviation system’s contribution to temperature change (Fig. 4b). However, since contemporary climate targets often focus on CO2, we also consider yearly CO2 emissions (Fig. 4a) and their accumulation (Fig. 4b) in relation to sectoral targets. We further elaborate on the rationale and implementation of these choices in their corresponding parts of the Methods section.

Results for 2024-2070 under the nine selected scenarios, which vary the air traffic volume with the level of aircraft (AC) technological improvements (indicated by the line colour: blue, orange, or red) and an evolving fuel mix (indicated by the line style: dashed, dash-dotted, or solid). The dotted black line represents the CO2 limit described by ICAO and IATA. a Total emissions, considering only CO2. b Temperature change from aviation based on CO2 emissions alone (saturated lines and dotted black line) and based on multiple climate forcers, notably including NOx and persistent contrails (desaturated lines).

Initially, the CO2 emissions from fossil-powered scenarios are comparable to those of AAF-powered scenarios (Fig. 4a). In fact, the CO2 emitted per RPK slightly increases initially (Supplementary Fig. 4c), given the high impact of an AAF value chain which still makes considerable use of fossil energy (Supplementary Fig. 5). As the energy mix rapidly transitions to renewable sources and the AAF share increases, AAF-powered scenarios begin to show substantial benefits, leading to a reduction in CO2 emissions and temperature change (Fig. 4).

AAF scenarios with hydrogen-powered aircraft emit 23-32% less CO2 annually than those without, but this reduction is modest compared to the reduction of roughly 80% relative to scenarios without ReFuelEU (Fig. 4a). Differences such as the diverging hydrogen demand (Fig. 3c) are limited in their influence on climate change, since we assume that AAF value chains are largely free of fossil resources by the time that hydrogen-powered aircraft enter the fleet. The difference in temperature change is more noticeable: we assume that a turbine burning hydrogen produces 90% less NOx emissions in cruise than one burning the same energy content in hydrocarbons63, leading to a distinct change in NOx impacts (Supplementary Fig. 6). However, such assumptions about the non-CO2 effects of AAF are highly uncertain (see Methods).

CO2 limit and air traffic volumes

We combine the ICAO and IATA targets mentioned earlier into a single annual CO2 limit (Fig. 4a), which does not consider other climate forcers (see Methods). This limit can be translated into a corresponding budget, equivalent to 2.4 Gton CO2 or a temperature change of 1.1 mK (Fig. 4b). Figure 4 shows that both the low-growth and high-growth scenarios consistently exceed the combined ICAO/IATA target, overshooting the budget in 2043 and 2038, respectively. In contrast, AAF-powered degrowth scenarios stay below the annual CO2 target for several decades, helping to offset the overshoot seen between 2045 and 2070 (Fig. 4a). As a result, the degrowth scenarios with and without hydrogen-powered aircraft reach the budget in 2067 and after 2070, respectively. Additional representations of this limit for different scenarios can be found in Supplementary Fig. 6.

It is notable that the fossil-powered degrowth scenario exceeds the CO2 budget later (2050 versus 2038) and to a lesser degree (overshoot in 2070 of 1.3 versus 2.3–2.5 Gton CO2) than either of the AAF-powered high-growth scenarios. This is closely related to fossil kerosene use (compare Fig. 4a to Fig. 3a). As discussed above, the assumed differences in technological development can largely compensate for growth, but only beyond 2035, leading to these distinct differences in cumulative CO2 emissions. This highlights the crucial influence of future air traffic on the resulting impacts. This influence is even more prominent when considering non-CO2 effects, which we discuss in the following section.

Climate neutrality and non-CO2 effects

In addition to CO2, aviation affects the climate through emissions such as methane (CH4), nitrogen oxides (NOx), hydrogen (H2), and the formation of persistent contrails (see Methods). When considering these non-CO2 effects, the overall temperature change is much higher (Fig. 4b), mainly due to the inclusion of NOx and aviation-induced cloudiness (Supplementary Fig. 5). Although non-CO2 effects are still highly uncertain, we assume that their impact is lessened with the introduction of AAF63,64. In addition to the reduction of NOx emissions from hydrogen-powered aircraft, mentioned above, AAF could result in lower impacts from persistent contrails: soot particles act as condensation nuclei in contrail formation, and as synthetic fuels undergo cleaner combustion, less soot is emitted (see Methods). As a result, temperature change sees a (temporary) reduction in AAF-powered scenarios as the AAF share increases (compare Fig. 4b to Fig. 3c), reaching a relative minimum by 2060 (Fig. 4b). In the degrowth and low-growth scenarios, temperature change stabilises at this lower level, while in the high-growth scenario, it increases again as air traffic continues to rise.

To assess climate mitigation beyond the target of net-zero CO2 emissions, the temperature increase can be used to define ‘climate-neutral aviation by 2050’: if the temperature increase does not exceed its 2050 level in subsequent years, the system could be considered climate neutral29,32. From 2050 to 2070, temperature change reduces by 13–20% for the AAF-powered degrowth scenarios and by 11-18% for those with low growth. A high-growth scenario can stay 1% below its 2050 temperature change with hydrogen-powered aircraft; without hydrogen-powered aircraft, the temperature change in 2070 is 7% higher than in 2050. However, when discarding the assumption that AAF reduce contrail impacts, temperature change follows the traffic trajectory past 2050 (Supplementary Fig. 6). In this case, only the degrowth scenario with hydrogen-powered aircraft could be considered climate neutral (Supplementary Fig. 7).

Aside from the uncertainty of AAF non-CO2 impacts, the fact that climate neutrality as defined here can be achieved under any growth scenario, despite large differences in impact, suggests that this is not a robust measure of successful climate mitigation. Because this definition of climate neutrality defines success with respect to a future reference year, it neglects the harmful effect of emissions which occurred prior to this reference year. A more meaningful measure of success requires a budget-based target. The CO2 budget is an example of this, and appears here as though it could be a good indicator of success. However, because it excluded non-CO2 impacts, overshoots appear smaller than they actually are. If the CO2-based budget applied to aviation’s full climate impact in 2070, CO2 represents just 15-19% of the total overshoot (Supplementary Table 1)—except for AAF-powered degrowth scenarios, where this is less than 2% due to CO2 emissions remaining close to the budget.

Discussion

Our scenarios envision the development of a hydrogen economy powered almost entirely by renewable energy. This implies the rapid and fundamental transformation of societal energy systems. If hydrogen is produced through electrolysis powered by fossil fuels or via steam methane reforming, even with carbon capture and storage, there is a much smaller reduction in climate impact (compare Supplementary Fig. 7 to Supplementary Fig. 8). Moreover, these systems have broader environmental effects beyond radiative forcing, such as resource depletion and air, soil, and water pollution (Supplementary Fig. 9). Acknowledging this reality, the aviation sector faces limits to the amount of low-impact hydrogen it can responsibly claim. This study does not quantify these limits; however, European policy outlines ambitions for future hydrogen production and supply. According to these ambitions, a hydrogen-based aviation sector would consume a large portion (15-45%) of Europe’s domestic hydrogen production by 2050 (Fig. 3c). Hydrogen is used more efficiently when powering aircraft directly than in the production of hydrocarbon e-fuel: assuming that hydrogen-powered aircraft achieve large-scale viability, this could reduce hydrogen consumption by 13-26% compared to using drop-in e-fuels (Fig. 3c). If part of the AAF mix in the presented scenarios were bio-based fuels, hydrogen consumption would decrease further, at the expense of biomass feedstocks. Depending on the particular feedstocks and fuel production pathways, e-fuels and bio-fuels can have similarly low climate impacts once fossil fuels are largely phased out25,49,65. We therefore expect that the exclusion of bio-based AAF from our analysis has a limited influence on the discussion of overall climate impact.

Provided that low-impact AAF replace fossil kerosene at scale, our analysis indicates that, by 2060, net CO2 emissions are less than one-fifth of those from an equivalent fossil-fuelled scenario (Fig. 4a). This suggests that achieving a climate-neutral aviation sector is feasible, with the temperature change caused by aviation reaching a (temporary) peak before 2050 (Fig. 4b). This conclusion is based on the assumption that alternative fuels reduce the impact of contrail formation, thereby compensating for the remaining CO2 emissions. However, because the requirements of ReFuelEU scale with the fuel supply, emission targets set by ICAO and IATA are likely to be exceeded unless accompanied by short-term demand reduction (Fig. 4b). Therefore, achieving climate neutrality by 2050 is not an accurate indicator of aviation’s contribution to climate change, for which a measure reflecting its total impact is necessary. This risk was previously identified by Brazzola et al.32, which we demonstrate in the context of ReFuelEU.

Following this reality, the notion of a sectoral climate budget becomes essential. Gössling and Humpe36 model how global aviation might respond to a strictly enforced climate budget, concluding that the risk of exceeding climate targets can be greatly reduced by decreasing the near-term air traffic volume, but that traffic could increase again following successful decarbonisation. Our work supports this observation: after 2035, the influence of high year-on-year air traffic growth on climate impact can broadly be negated (Fig. 4b), so reducing the overall demand prior to 2035 could lead to a similar temporary reduction. Following our approach, up to 8% of the CO2-based budget remains when combining degrowth with technological breakthroughs (Supplementary Fig. 7), allowing for addition air travel within the budget—which could increase further were decarbonisation to exceed the trajectory we assume here. Still, when understanding the impact of NOx and contrails as closely linked with total fuel use and distance flown respectively, there is a limit to the yearly provisioning of AAF-powered air transport within a given sectoral climate budget. In this context, CO2 is primarily a concern to the extent that its accumulation limits how much of the total budget remains in the future, again highlighting the importance of phasing out fossil fuels. This illustrates how, from a climate budget perspective, our current use of the aviation sector directly influences the ability of future generations to benefit from flight. Kito et al.28 aptly discuss this as ‘intergenerational equity’. From this perspective, demand management becomes a temporal redistribution of air travel.

It is important to recognise that the aviation sector does not commit itself to meeting the evaluated climate targets solely by reducing its own emissions. Instead, CORSIA operates as an offsetting scheme, where the aviation sector either prevents emissions in other sectors or facilitates negative emissions. This is problematic for several reasons. First, offsetting excessive CO2 emissions only addresses part of aviation’s contribution to climate change (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Table 1), as Sacchi et al.29 also illustrate. Second, relying heavily on offsetting reflects a limited vision of the future and may undermine alternative approaches11,66. Techniques such as carbon removal could help return atmospheric CO2 to pre-industrial levels. This requires compensating for past emissions—using it to extend the use of fossil resources is a secondary distraction67. To the extent that this latter application could be justifiably allocated to aviation, we argue that it should contribute to addressing economic and environmental inequality—for example, by benefitting regions less prepared for the large-scale deployment of AAF or with a relatively lower contribution to past emissions. Even within our analysis, climate targets were formulated based on the historical distribution of environmental burdens. This should not be mistaken for a fair or just distribution68,69 and further highlights the normative issues at play in international aviation policy70. These issues cannot be resolved without addressing the ethical questions and value judgments they entail. This lies beyond the scope of this study but offers valuable insights for future research.

In light of these considerations, we suggest that the adoption of measures to limit or reduce air travel could be effective in reducing both near-term use of fossil resources and the continuous impacts of non-CO2 effects to the extent that other measures risk falling short of the desired impact mitigation. Various economic policies could facilitate a modal shift, e.g., from air to rail71, but it is evident that many flights have no feasible alternative. Reducing air travel also implies journeys not taken. While a journey doesn’t always have a clear necessity or benefit to the traveller72,73, this dimension is hard to access on a policy level. Restrictions to air travel should effectively mitigate climate change while fostering an equitable society on a liveable planet. The social and environmental realisation of these goals could be undermined by unintended incentives, e.g., by reinforcing current traffic patterns or encouraging additional long-distance flights. Ensuring an equitable distribution of flight activity within and between regions for both present and future generations will require innovative policy solutions. Our findings highlight the urgent need for such solutions.

Methods

We model the period 2024-2070 using a time resolution of one year. The sectoral model has a general workflow which starts by quantifying the air transport volume at each time step, depending on the traffic projection used. This feeds into a connected stock-and-flow model, creating persistent fleets of aircraft and fuel infrastructure to meet the required air transport and fuel supply. Time-explicit lifecycle inventories are generated and aggregated for the matching stocks and flows, creating timeseries of emissions. These time series are used to calculate warming-equivalent emissions, leading to a value for the change in temperature over time.

Modelling requirements and comparison to previous work

As outlined in the introduction, we conducted this work in order to understand the implications of ReFuelEU for the climate impact of European aviation. When quantifying and discussing this climate impact, ongoing academic and societal discussions of how to define successful climate change mitigation for aviation must be considered (see Aviation climate targets, below). For our assessment of the sector to be robust, it should consider diverse trends for air traffic demand and improvements to aircraft technology. Within these trends, it is relevant to consider the possibility of hydrogen-powered aircraft, given the European focus on hydrogen13,74. Based on these considerations, we formulated requirements for our modelling setup:

-

1.

A consistent trajectory for the AAF share, regardless of other factors. This is necessary in order to align the deployment of AAF with the requirements of ReFuelEU.

-

2.

A consistent system boundary and coverage of impacts. In order to address the impacts of flight from a lifecycle perspective, all energy carriers must be considered with a so-called well-to-wing system boundary, spanning from infrastructure and production to use of the fuel, with coverage of all related climate impacts without a priori assuming that a fuel has zero impact.

-

3.

A consideration for the role of air transport demand in the introduction of novel aircraft. This is necessary in order to understand the possible impact of fleet dynamics on the diffusion of future aircraft generations. For example, growing demand necessitates a growing fleet, with more new aircraft coming in than are being retired. Such behaviour can affect the rate at which new generations make up a given share of the total fleet.

-

4.

The inclusion of hydrogen-powered aircraft. The inclusion of such aircraft must, of course, also comply with the other requirements.

-

5.

An evaluation of climate mitigation which considers:

-

5.1

. An equivalent to goals which include the immediate future. Such goals do not focus (exclusively) on achieving a climate-neutral sector, but set targets for gradual climate mitigation.

-

5.2

. An equivalent to net-zero 2050 goals. With such goals, impacts are evaluated starting from a future year. This places the focus on an advanced state of the transition towards climate neutrality.

-

5.1

The details of how we implemented each of these requirements are given in the following sections. We also reviewed related aspects in previous works which discuss aviation climate mitigation pathways (Table 1). These articles provide insightful perspectives on the future of aviation’s impact on climate change, although none meet all of our requirements. This is natural, considering differences in research objective.

Aviation climate targets

Achieving so-called ‘climate-neutral’ or ‘net-zero’ aviation by 2050 are recurring concepts without a universal definition. Industry roadmaps are typically defined in terms of CO2 emitted during flight, with the only coverage of other climate impacts being AAF fuel production13,14. This approach neglects other activities supporting flight, as well as non-CO2 effects such as contrail formation. We consider the 2050 net-zero goal using what Sacchi et al. term ‘warming neutrality’, which ‘requires that the [radiative] forcing is stabilised at the 2050 level’29, considering all climate forcers associated with the aviation system. This definition is conceptually similar to the ‘Bronze’ standard for climate neutrality, defined by Brazzola et al.32. In other words, we consider commercial aviation to be climate neutral if the temperature change resulting from the sector does not increase past its 2050 level. We evaluate this by comparing the temperature change in 2050 and 2070, the end of our temporal scope.

In addition to the trend in warming beyond 2050, which the above definition considers, there is the question of what magnitude of warming the aviation sector should remain within. This is an emerging subject of discussion69 and cannot be fully operationalised within the scope of this study. As a proxy, we follow the reasoning of Kito et al.28, who created a CO2 budget based on the emission limits for CO2 of the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) and the International Air Transport Association (IATA). The limits are based on the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA). In short, this scheme, which currently extends to 2035, sets a yearly limit to emissions from international aviation, covering CO2 and a few other greenhouse gases6. In response to the disruptive effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on aviation, this yearly limit was adjusted to 85% of covered emissions in 20195. IATA has set the goal that, after 2035, this limit will be linearly reduced such that it reaches zero in 20504 (Fig. 1a). Using our model, we estimate 150 Mton CO2 emissions for 2019. We use this value to scale the yearly emission limit, rather than the 147 Mton CO2 reported by the European Union Aviation Safety Agency75. This yearly emission limit creates an equivalent warming limit (Fig. 1b). Since this limit is specific to CO2 emissions, it does not apply to other climate forcers.

System boundary

As described above, sectoral targets often do not adopt a consistent lifecycle perspective. Nevertheless, we attempt to amend this, using a so-called well-to-wing perspective for fossil fuel and AAF, which spans the cradle-to-grave construction, operation, and decommissioning of fuel production infrastructure in addition to fuel use (Supplementary Fig. 1). Additionally, the lifecycles of the aircraft structures are included, as their share in environmental impacts has been speculated to increase with the use of AAF76. Due to a lack of prospective data, airports and the construction of new fuel distribution infrastructure are excluded. These are known to make a small contribution to the climate change impact of the sector55. When considering the environment more broadly, their share becomes more prominent55,76, but this falls outside the scope of the present work.

Despite their prominent role in sectoral narratives, offsetting and negative carbon technologies are excluded from our analysis. As discussed in our introduction, we make this choice based on the inefficacy of past offsetting measures. Sacchi et al.29 include a detailed description of carbon capture and storage across various scenarios, illustrating that this shifts the climate burden to ‘excessive pressure on economic and natural resources’. Although our inventories allow the quantification of additional environmental impacts (Supplementary Fig. 9), we focus on climate change and do not quantify economic indicators but further discuss these limitations (see Discussion).

Impact mitigation measures relating to passenger occupancy rate and technological improvement of AAF infrastructure were assessed, but excluded from the main results due to their limited influence (Supplementary Fig. 10). Several other possible measures were not quantified here, including increased aircraft replacement rates, improved air traffic management, and the introduction of electric aircraft. However, this does not mean that these measures are unimportant.

European aviation and air transport demand

International agreements generally define the aviation emissions allocated to a particular region based on the flights departing from that region. This approach is used here as well. In the context of this research, ‘Europe’ is defined as a selection of countries closely aligned in their approach to reducing greenhouse gas emissions, being the EU, the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), which includes Iceland, Norway, Switzerland, and Liechtenstein, and additionally, the United Kingdom. This geographical definition is adopted from the Destination 2050 report13. Note that the United Kingdom is not subject to ReFuelEU, but does have a similar approach to decarbonising aviation, setting targets for the AAF share of the fuel supply, with its target of 75% AAF in 205077 being comparable with ReFuelEU minimum of 70%.

The volume of air transport is estimated by processing flight data78 from 2019 and scaling this according to the demand for 2024-2070. To evaluate commercial aviation, the scope is limited to the most common types of flight, being passenger transport on scheduled flights. It can, therefore, be described in terms of RPK. As we approximate the sector as generic narrow-body and wide-body aircraft, the RPK for these generic aircraft is determined based on the movements of the most commonly used narrow-body and wide-body aircraft79. For both aircraft types, a number of flight segments are created (Table 2), which are used to generate aircraft fleets (see Fleet dynamics). Flights are divided into distance segments, each given a representative flight distance, used when modelling the segment’s flights (see Aircraft performance and aircraft product systems). Furthermore, separate segments are identified for intra-Europe or extra-Europe flights, using our definition of ‘Europe’, as this factor is considered in the introduction of hydrogen aircraft, shown in the last column of Table 2 (see Fleet dynamics). A generic seat occupancy of 80% is assumed. This value is in line with historic trends55 but below aspirational goals16. However, this does not influence the comparative assessment between scenarios. Seat occupancy was found to have a relatively limited impact on the overall results when compared to other variables (Supplementary Fig. 10).

The demand for 2024-2070 following the EUROCONTROL pathways (‘low growth’, ‘base growth’, and ‘high growth’) is determined by combining EUROCONTROL’s seven-year50 and 2050 forecasts51. For 2024-2031, the 2019 data is scaled according to the projections for en-route service unites. For 2032-2070, the projected growth rate in flight numbers is used; by scaling the 2019 data as a whole, we neglect the trend towards larger aircraft and further flight distances13. Our ‘degrowth’ pathway strongly deviates from any industry forecast. This pathway is based on a panel consultation of the Dutch population on achieving national climate targets54. Several of the options most widely chosen by participants involve the suppression of commercial aviation, aligning with public support in France and the United Kingdom to disincentivise air travel52,53. The authors report this as two measures: a ban on flights to destinations within 600 km and a reduction in the number of flights by 30%54. We, therefore, opt for a linear reduction in yearly RPK from 2024 to 2034, after which it stagnates at 70% of the 2019 value. No distinction is made among distance segments when applying these growth trajectories.

Fleet dynamics

There are several ways to represent the technological development of aircraft as a function of time. We use a dynamic stock-and-flow model representing long-lived capital goods, covering both aircraft and key AAF production infrastructure (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 3). Fleets are formed by combining stocks that perform the same function, e.g., representing different generations of narrow-body aircraft. After defining an initial condition for each fleet, its composition changes at each time interval: units which pass their maximum age leave the fleet, after which enough units enter the fleet so that the fleet can meet its required output (see Table 2). To this end, the seating capacity, yearly distance flown, fuel type, and operational lifetime are key aircraft characteristics (Table 3), while plants in the AAF supply chain are described by their yearly production capacity and operational lifetime (Table 4). Generally, an older aircraft is replaced before reaching its design lifetime, in the range of 25-30 years, provided that the airline operating it can afford the new model28,55,80. Several economic factors feed into this, which are beyond our scope. Instead, we use a constant maximum age of 22 years for all aircraft and set up an initial fleet with a mean age of around 11 years30.

The fuel type of aircraft factors into their fleet dynamics based on the compatibility of hydrogen aircraft with the flight segments. The value used here (Table 2) indicates what share of aircraft introduced to satisfy the segment’s demand is hydrogen aircraft, provided a suitable hydrogen aircraft exists for the specified time and scenario (Supplementary Fig. 3). Following the Destination 2050 report13, we assume that early hydrogen aircraft exclusively service intra-Europe routes. A potential of 1 implies that all intra-Europe flights are eventually serviced by hydrogen aircraft. However, this does not require all European airports to immediately accommodate hydrogen aircraft, as the new aircraft introduced yearly only represent a minority of the total fleet. Furthermore, to reflect that there could be hydrogen-compatible airports outside of Europe, the extra-Europe wide-body segments are given a hydrogen potential of 0.5.

Fuel supply and fuel product system

We base the introduction of AAF on the ReFuelEU Aviation rules. These describe the minimum volume of compliant AAF that must be used in a given period. This is generalised to a set share per year (Fig. 1c). To evaluate this share, ReFuelEU Aviation specifies that hydrogen should be considered based on energy content18. We extend this to e-fuel, assuming a lower heating value (LHV) for each fuel: 43 MJ/kg for fossil kerosene, 45 MJ/kg for e-fuel, and 120 MJ/kg for hydrogen.

The logical order applied when quantifying the fuel supply starts from the reference flow, with the air traffic demands being used to construct the aircraft fleets (see Fleet dynamics). For each time interval, the activity of the aircraft fleet requires a certain volume of hydrocarbon fuels (here, fossil kerosene and e-fuel) and liquid hydrogen. In scenarios that comply with a certain minimum volume of AAF, all liquid hydrogen contributes to this minimum, with the remainder achieved through e-fuel as part of the total hydrocarbon demand.

Having determined the volume of each fuel required per time interval, the fuel production chains are quantified. For fossil kerosene, this is done by connecting a relevant background process (see Prospective background lifecycle inventories). For the AAF, fleets of key production plants are created. The efficiency of production plants based on emerging technologies is defined as a function of the plant’s construction year. As estimated performances vary, this is considered as sensitivity (Supplementary Fig. 10).

Hydrogen is assumed to be produced through water electrolysis using proton exchange membrane (PEM) electrolysers. The performance of the electrolysers, including future improvements, is based on literature46,56,81 (Supplementary Table 2). The oxygen molecules (O2) obtained from electrolysis are not considered a co-product but are left out of the inventory. Hydrogen distribution is based on Sacchi et al.29, requiring 3.2 kWh/kg electricity for compression. For use on hydrogen aircraft, hydrogen is liquefied after distribution82. Liquefaction is represented by its operational energy demand alone (Supplementary Table 2). Transportation and boil-off losses are each estimated at 1%, resulting in hydrogen emission to the air.

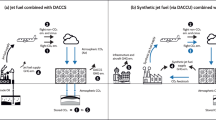

The sorbent-based direct air capture (DAC) system is based on the inventories of Terlouw et al.83. We estimate its performance and learning rates by comparing and combining several sources84,85,86 (Supplementary Table 3). Fischer-Tropsch plants are also described by combining several sources87,88,89. Several products are created in such plants. To isolate impacts related to the production of e-fuel, physical allocation centred around lower heating value (LHV) is applied, in line with the literature. The production process is simplified to flows of CO2, H2, and electricity (Supplementary Table 4). Due to a lack of data, cooling water and wastewater are cut off.

The fuel tank-to-wing phase (i.e., combustion) distinguishes between the three fuels while accounting for the aircraft using the fuel and aspects of the flight itself. The flight is split up into the landing and take-off cycle (LTO), where emissions are relatively low to the ground, and climb/cruise/descent (CCD), where emissions are higher up. Fuel use for LTO is assumed to be consistent across flights, while CCD scales with the flight distance. Inventories for hydrocarbon fuels are based on the EMEP/EEA air pollutant emission inventory guidebook90. Metal impurities released when combusting fossil kerosene, taken from the ecoinvent 3.9.1 database91, are also included in these inventories but do not affect climate change. E-fuel is assumed not to have these metal impurities nor sulphur impurities, meaning that no sulphur oxides (SOx) are formed. Inventories for hydrogen use assume a gas turbine63, resulting in NOx emissions and contrail formation, although we make no further distinction with a fuel cell-driven electric powertrain.

Aircraft performance and aircraft product systems

The present fleet is represented using the fuel use, emissions, and seating capacity of common aircraft, used as proxies. These are the Airbus A320 and A320neo narrow-body aircraft and the Boeing 777-300 and Airbus A350-900 wide-body aircraft (Table 3 and Table 5). This choice of reference aircraft is adopted from Grewe et al.30. The newer of these aircraft (meaning the A320neo and A350-900) are also used as reference for future generations (Table 6). The business-as-usual scenario is based on the historical trends in performance observed by Cox et al.55. Grewe et al.30 provide expert estimates for the improvements that could be achieved in conventional aircraft over the course of the coming decades, which forms our optimistic scenario. Speculatively, larger improvements are possible when introducing new aircraft concepts, represented in the breakthrough scenario, which uses values obtained from Cox et al.55.

For hydrogen aircraft, estimates reported by ICAO are used92. These express three scenarios for the fuel use of hydrogen aircraft relative to their contemporary conventional aircraft while accounting for payload capacity. The resulting range aligns with values reported elsewhere82,93,94. To streamline the scenario space, hydrogen and hydrocarbon aircraft performances are combined into a single variable.

Cradle-to-gate and end-of-life processes are included for each aircraft entering and leaving the fleet. We adapt aircraft material composition (Supplementary Table 5) and the energy demands of these processes from Cox et al.55. Industry estimates95,96,97 are used to quantify manufacturing waste through so-called buy-to-fly rations: 8:1 for aluminium alloy95, 1.5:1 for composites96, and 2.2:1 for other materials97. Since hydrogen aircraft are likely to have a higher operating empty weight (OEW) than contemporary hydrocarbon aircraft, their mass is increased by 10%22, but no change to their relative material composition is considered. For the sake of simplicity, aircraft cradle-to-gate and end-of-life processes, including OEW, are considered independent from aircraft performance.

Prospective background lifecycle inventories

The inventories created through the methods described above use economic activities not modelled within this work, but directly adopted from another source. Through these activities, the service system connects itself to the background. The background databases used here are each generated using the Python library premise46. This library enables the transformation of an ecoinvent database to align with the regions and scenarios of an integrated assessment model, adding several additional activities in the process.

The ‘SSP2-PkBudg1150’ pathway of the REMIND model98 is used to generate background databases for the narrative scenarios. In this pathway, the global mean surface temperature increase by 2100 is around 1.7 °C, thereby achieving the goal of the Paris Agreement. Databases are generated for five-year time intervals. Selected flows which connect to the foreground are then exported and linearly interpolated to align with the one-year time interval. The ‘EUR’ region of REMIND is assumed to be representative of the geographic region considered. As a sensitivity analysis, a prospective hydrogen market generated for this pathway by Wei et al.21 is used instead of the assumption that all hydrogen is created through electrolysis (Supplementary Fig. 8).

Impact assessment

Aviation has several environmental effects, noise, air quality degradation, and climate change being among the most prevalent. Focussing on climate change, a topic of interest is the non-CO2 effects of aviation. The most prevalent of these are caused by nitrogen oxides (NOx) and by condensation of water into contrails, resulting in aviation-induced cloudiness (AIC)2. However, the short lifespan of these climate forcers raises conceptual challenges41. For example, calculating the Global Warming Potential (GWP) of a climate forcer simplifies its impact to a static number, but makes it dependent on the chosen time horizon and misrepresents its impact over time40. In order to address these challenges, Allen et al.40 introduced the concept of GWP*, which scales according to the change in emissions over time, rather than the absolute quantity emitted. In the following years, Cain et al.99 and Smith et al.61 expand and refine the calculation of warming-equivalent emissions, focussing their calibration on the impact of methane (CH4). Quantifying climate impacts in terms of warming equivalence is useful in obtaining an impression of the temperature response within the temporal scope considered. This temperature change is calculated by multiplying the warming-equivalent emissions with the transient climate response to cumulative CO2 emissions (TCRE) factor. Likely, TCRE falls in the range of 0.27-0.63 K per 1000 Gton CO2—here, we use the best estimate of 0.45 K per 1000 Gton CO262. A drawback of expressing impact following warming equivalence is that climate forcing beyond the temporal scope at hand is obfuscated.

Klöwer et al.31, Sacchi et al.29, and Arriolabengoa et al.42 have each assessed aviation based on warming-equivalent emissions, although the details of their implementations vary substantially. We base our calculations on Arriolabengoa et al., directly adapting their code in ours100, defining warming-equivalent emissions as:

where

As such, warming-equivalent emissions are made up of two terms: the extent to which warming equivalence is determined by a change in radiative forcing ∆F(t) due to variations over a time period ∆t, and the extent to which it is determined by the immediate forcing of those emissions, F(t). The unitless parameter s determines the proportional contribution of each term. AGWPH is the Absolute Global Warming Potential of CO2 with respect to a time horizon H, here, 100 years. We use values for s and ∆t proposed by Arriolabengoa et al. as ‘updated settings’. These represent impacts relating to the lifetime of CH4 (such as the effect of NOx on decreasing atmospheric CH4) following the calibration of Cain et al.99 (s = 0.25, ∆t = 20), while modelling climate forcers with shorter-lived effects (such as persistent contrails) based entirely on year-on-year changes in emission (s = 0.0, ∆t = 1). This is conceptually similar to the approach Sacchi et al. take to very-short-lived effects29.

However, the parameters of Arriolabengoa et al. only extend to non-CO2 effects stemming from flight itself42: contrails, NOx, H2O, soot, and SOx. In order to adequately represent the impact of ground-level activities beyond CO2, we reintroduce the parameters for CH4 and introduce new ones for the direct emission of H2. To do so, we use the radiative efficiency of Paulot et al.101. Hydrogen influences radiative forcing indirectly, by affecting the production of methane, ozone, and stratospheric water. We therefore give it the same warming-equivalent parameters as CH4 and the more persistent effects of NOx. Since the contribution of CH4 and H2 to the results is minimal (Supplementary Fig. 6), we consider it unnecessary to include additional climate forcers, which we expect to have comparable or smaller contributions.

The principle used by Sacchi et al.29 to consider the effect of fuel composition on ice crystal formation64 is adopted. This is estimated using the hydrogen mass fraction of the fuel, which is taken to be 13.73% for fossil kerosene and 15.29% for e-fuel. Following the relation of Sacchi et al., using e-fuel instead of fossil kerosene would reduce AIC impacts by 65.95%. For hydrogen-powered aircraft, we furthermore adopt the assumption of Kossarev et al.22 that e-fuel and hydrogen result in similar AIC impacts. However, Kossarev et al. estimate this reduction to be no more than 40%, indicating that our estimates for AIC of AAF are relatively optimistic. Even with this large reduction, AIC remains the most prominent contributor to temperature change (Supplementary Fig. 6). It must be stressed that the AIC impact of future fuels is a subject of ongoing research, with additional uncertainty added by the possibility of contrail avoidance strategies, which are not covered in this work.

Data availability

Recreating the full workflow requires access to the ecoinvent 3.9.1 database91, system model ‘Allocation, cut-off by classification’ (licence required) and the EUROCONTROL Aviation Data Repository for Research78 (access restricted). To facilitate reproduction, the Zenodo repository for this study (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14222579)100 includes intermediate data. All graphed data is also provided in this repository.

Code availability

The Zenodo repository for this study (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14222579)100 provides all scripts used in generating the results from intermediate data. The generation of the intermediate data involved use of the Activity Browser102 (version 2.9.2) and premise46 (version 1.8.0).

References

Grobler, C. et al. Marginal climate and air quality costs of aviation emissions. Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 114031 (2019).

Lee, D. S. et al. The contribution of global aviation to anthropogenic climate forcing for 2000 to 2018. Atmos. Environ. 244, 117834 (2021).

UNFCCC. The Paris Agreement (UNFCCC, 2015).

IATA. Net Zero Carbon 2050 Resolution (IATA, 2022).

ICAO. Resolution A41-22: Consolidated statement of continuing ICAO policies and practices related to environmental protection – Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA). (2023).

ICAO. CORSIA Methodology for Calculating Actual Life Cycle Emissions Values. https://www.icao.int/environmental-protection/CORSIA/Documents/CORSIA_Eligible_Fuels/ICAO%20document%2007%20-%20Methodology%20for%20Actual%20Life%20Cycle%20Emissions%20-%20June%202022.pdf (2022).

ICAO. CORSIA Emissions Unit Eligibility Criteria. https://www.icao.int/environmental-protection/CORSIA/Documents/ICAO_Document_09.pdf (2019).

Trencher, G., Nick, S., Carlson, J. & Johnson, M. Demand for low-quality offsets by major companies undermines climate integrity of the voluntary carbon market. Nat. Commun. 15, 6863 (2024).

Badgley, G. et al. Systematic over-crediting in California’s forest carbon offsets program. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 1433–1445 (2022).

Ahonen, H.-M., Kessler, J., Michaelowa, A., Espelage, A. & Hoch, S. Governance of fragmented compliance and voluntary carbon markets under the Paris agreement. Polit. Gov. 10, 235–245 (2022).

Stuart, D., Gunderson, R. & Petersen, B. Climate change and the Polanyian counter-movement: Carbon markets or degrowth?. New Polit. Econ. 24, 89–102 (2019).

Markusson, N., McLaren, D. & Tyfield, D. Towards a cultural political economy of mitigation deterrence by negative emissions technologies (NETs). Glob. Sustain. 1, e10 (2018).

NLR & SEO. Destination 2050: A Route to Net Zero European Aviation. https://www.destination2050.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Destination2050_Report.pdf (2021).

ATAG. Waypoint 2050. https://aviationbenefits.org/downloads/waypoint-2050/ (2021).

ICAO. Report on the Feasibility of a Long-Term Aspirational Goal (LTAG) for International Civil Aviation CO2 Emission Reductions. (2022).

IATA. Aviation Net-Zero CO2 Transition Pathways. https://www.iata.org/contentassets/8d19e716636a47c184e7221c77563c93/nz-roadmaps.pdf (2024).

Jamie, B. & Keith, A. Missed Targets: A Brief History of Aviation Climate Targets of the Early 21st Century https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5d30896202a18c0001b49180/t/6273db16dcb32d309eaf126e/1651759897885/Missed-Targets-Report.pdf (2022).

European Parliament & Council of the European Union. Regulation (EU) 2023/2405 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 October 2023 on Ensuring a Level Playing Field for Sustainable Air Transport (ReFuelEU Aviation) (2023).

Detsios, N. et al. Recent advances on alternative aviation fuels/pathways: a critical review. Energies 16, 1904 (2023).

Krogh, A., Lozano, E. M., Thellufsen, J. Z., Grue, J. & Pedersen, T. H. Method for comparing efficiency and system integration potential for biomass-based fuels production pathways. J. Clean. Prod. 376, 134336 (2022).

Wei, S., Sacchi, R., Tukker, A., Suh, S. & Steubing, B. Future environmental impacts of global hydrogen production. Energy Environ. Sci. 17, 2157–2172 (2024).

Kossarev, K., Scholz, A. E. & Hornung, M. Comparative environmental life cycle assessment and operating cost analysis of long-range hydrogen and biofuel fueled transport aircraft. CEAS Aeronaut. J. 14, 3–28 (2023).

Gangoli Rao, A., Yin, F. & Werij, H. G. C. Energy transition in aviation: the role of cryogenic fuels. Aerosp 7, 181 (2020).

Airbus. ZEROe. https://www.airbus.com/en/innovation/zero-emission-journey/hydrogen/zeroe (2023).

van der Giesen, C., Kleijn, R. & Kramer, G. J. Energy and climate impacts of producing synthetic hydrocarbon fuels from CO2. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 7111–7121 (2014).

Habermeyer, F., Weyand, J., Maier, S., Kurkela, E. & Dietrich, R. U. Power Biomass to Liquid—an option for Europe’s sustainable and independent aviation fuel production. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-022-03671-y (2023).

Åkerman, J., Kamb, A., Larsson, J. & Nässén, J. Low-carbon scenarios for long-distance travel 2060. Transp. Res. Part Transp. Environ. 99, 103010 (2021).

Kito, M., Takayabu, H. & Nansai, K. Carbon-neutral pathways to 2050 for Japan’s aviation industry in the absence of a mass supply of sustainable aviation fuels. J. Ind. Ecol. https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.13443 (2023).

Sacchi, R. et al. How to make climate-neutral aviation fly. Nat. Commun. 14, 3989 (2023).

Grewe, V. et al. Evaluating the climate impact of aviation emission scenarios towards the Paris Agreement including COVID-19 effects. Nat. Commun. 12, 1–10 (2021).

Klöwer, M. et al. Quantifying aviation’s contribution to global warming. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 104027 (2021).

Brazzola, N., Patt, A. & Wohland, J. Definitions and implications of climate-neutral aviation. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 761–767 (2022).

Dray, L. et al. Cost and emissions pathways towards net-zero climate impacts in aviation. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 956–962 (2022).

Bergero, C. et al. Pathways to net-zero emissions from aviation. Nat. Sustain. 6, 404–414 (2023).

Planès, T., Delbecq, S. & Salgas, A. AeroMAPS: a framework for performing multidisciplinary assessment of prospective scenarios for air transport. J. Open Aviat. Sci. https://doi.org/10.59490/joas.2023.7147 (2023).

Gössling, S. & Humpe, A. Net-zero aviation: Transition barriers and radical climate policy design implications. Sci. Total Environ. 912, 169107 (2024).

Brazzola, N., Meskaldji, A., Patt, A., Tröndle, T. & Moretti, C. The role of direct air capture in achieving climate-neutral aviation. Nat. Commun. 16, 588 (2025).

Gössling, S. & Humpe, A. The global scale, distribution and growth of aviation: Implications for climate change. Glob. Environ. Change 65, 102194 (2020).

Prather, M. J., Gettelman, A. & Penner, J. E. Trade-offs in aviation impacts on climate favour non-CO2 mitigation. Nature 643, 988–993 (2025).

Allen, M. R. et al. A solution to the misrepresentations of CO2-equivalent emissions of short-lived climate pollutants under ambitious mitigation. Npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 1, 16 (2018).

Megill, L., Deck, K. & Grewe, V. Alternative climate metrics to the Global Warming Potential are more suitable for assessing aviation non-CO2 effects. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 1–9 (2024).

Arriolabengoa, S., Planès, T., Mattei, P., Cariolle, D. & Delbecq, S. Lightweight climate models could be useful for assessing aviation mitigation strategies and moving beyond the CO2-equivalence metrics debate. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 1–16 (2024).

Rupcic, L. et al. Environmental impacts in the civil aviation sector: current state and guidance. Transp. Res. Part Transp. Environ. 119, 103717 (2023).

Pollet, F., Planès, T. & Delbecq, S. A comprehensive methodology for performing prospective life cycle assessments of future air transport scenarios. in 34th Congress of the International Council of the Aeronautical Sciences (ICAS, 2024).

Giesen, C., Cucurachi, S., Guinée, J., Kramer, G. J. & Tukker, A. A critical view on the current application of LCA for new technologies and recommendations for improved practice. J. Clean. Prod. 259, 120904 (2020).

Sacchi, R. et al. Prospective environmental impact assessment (premise): a streamlined approach to producing databases for prospective life cycle assessment using integrated assessment models. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 160, 112311 (2022).

Thonemann, N., Schulte, A. & Maga, D. How to conduct prospective life cycle assessment for emerging technologies? A systematic review and methodological guidance. Sustainability 12, 1192 (2020).

Barke, A., Bley, T., Thies, C., Weckenborg, C. & Spengler, T. S. Are sustainable aviation fuels a viable option for decarbonizing air transport in Europe? An environmental and economic sustainability assessment. Appl. Sci. 12, 597 (2022).

Ballal, V., Cavalett, O., Cherubini, F. & Watanabe, M. D. B. Climate change impacts of e-fuels for aviation in Europe under present-day conditions and future policy scenarios. Fuel 338, 127316 (2023).

EUROCONTROL. EUROCONTROL Seven-Year Forecast 2025-2031—Spring 2025 Update. https://www.eurocontrol.int/publication/eurocontrol-forecast-2025-2031 (2025).

EUROCONTROL. EUROCONTROL Aviation Long-Term Outlook. https://www.eurocontrol.int/publication/eurocontrol-forecast-2024-2050 (2024).

Climate Assembly UK. The Path to Net Zero: Climate Assembly UK Report. https://climateassembly.uk/report/read/ (2020).

Convention Citoyenne pour le climat. Contribution of the Citizens’ Convention on Climate for a Way out of the Crisis. https://www.conventioncitoyennepourleclimat.fr/en/2020/04/20/contribution-of-the-citizens-convention-on-climate-for-a-way-out-of-the-crisis/ (2020).

Populytics. Burgerkeuzes in Kaart: Resultaten van de Nationale Klimaatraadpleging 2023. https://populytics.nl/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/20231025-Eindrapport-Klimaatraadpleging.pdf (2023).

Cox, B., Jemiolo, W. & Mutel, C. Life cycle assessment of air transportation and the Swiss commercial air transport fleet. Transp. Res. Part Transp. Environ. 58, 1–13 (2018).

Delpierre, M., Quist, J., Mertens, J., Prieur-Vernat, A. & Cucurachi, S. Assessing the environmental impacts of wind-based hydrogen production in the Netherlands using ex-ante LCA and scenarios analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 299, 126866 (2021).

Langkau, S. et al. A stepwise approach for scenario-based inventory modelling for prospective LCA (SIMPL). Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 28, 1169–1193 (2023).

Font Vivanco, D., Kemp, R. & van der Voet, E. The relativity of eco-innovation: environmental rebound effects from past transport innovations in Europe. J. Clean. Prod. 101, 71–85 (2015).

Giraudet, L.-G. et al. “Co-construction” in deliberative democracy: lessons from the French Citizens’ Convention for Climate. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 9, 1–16 (2022).

Corder, M. Dutch government shelves plans to reduce flights from Amsterdam’s busy Schiphol Airport. AP News https://apnews.com/article/schiphol-flights-reduction-scrapped-fb284758c580d7d24d544f4760c3f605 (2023).

Smith, M. A., Cain, M. & Allen, M. R. Further improvement of warming-equivalent emissions calculation. Npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 4, 19 (2021).

IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report Of The Intergovernmental Panel On Climate Change. 2391. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896 (2021).

Mitchell, J. & Hobson, M. 1.A Annex hydrogen combustion. in EMEP/EEA Air Pollutant Emission Inventory Guidebook 2023 (European Environmental Agency, 2023).

Burkhardt, U., Bock, L. & Bier, A. Mitigating the contrail cirrus climate impact by reducing aircraft soot number emissions. Npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 1, 37 (2018).

Penke, C., Falter, C. & Batteiger, V. Pathways and environmental assessment for the introduction of renewable hydrogen into the aviation sector. Sustain. Prod. Life Cycle Eng. Manag. 41–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-50519-6_4 (2021).

Köves, A. & Bajmócy, Z. The end of business-as-usual?—A critical review of the air transport industry’s climate strategy for 2050 from the perspectives of Degrowth. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 29, 228–238 (2022).

Malm, A. & Carton, W. Seize the means of carbon removal: the political economy of direct air capture. https://doi.org/10.1163/1569206X-29012021 (2021).

Heide, M. & Gjerris, M. Embedded but overlooked values: ethical aspects of absolute environmental sustainability assessments. J. Ind. Ecol. https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.13472 (2024).

Delbecq, S., Fontane, J., Gourdain, N., Planès, T. & Simatos, F. Sustainable aviation in the context of the Paris agreement: a review of prospective scenarios and their technological mitigation levers. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 141, 100920 (2023).

Mai, D. T. T. & Yan, B. Divergences between the European Union and China on reducing international aviation emissions. Asia Eur. J. 21, 1–21 (2023).

Álvarez-Antelo, D., López-Muñoz, P., Llases, L. & Lauer, A. Towards a sustainable mobility lifestyle: Exploring the flight to rail shift through model-based behavioural change scenarios. Ecol. Econ. 230, 108498 (2025).

Baltruszewicz, M. et al. Social outcomes of energy use in the United Kingdom: household energy footprints and their links to well-being. Ecol. Econ. 205, 107686 (2023).

Gössling, S., Hanna, P., Higham, J., Cohen, S. & Hopkins, D. Can we fly less? Evaluating the ‘necessity’ of air travel. J. Air Transp. Manag. 81, 101722 (2019).