Abstract

Abrupt changes at decadal time scale are recurrent events in the modern climate system. Using multiple trend-change detection methods, here we report such an abrupt trend change in the early 2010s in the altimetry-based global mean sea level record, as well as in its thermal and mass components. Abrupt trend change in the mass component is mostly due to terrestrial water storage and to a lesser extent to ice sheet melting. The linear rate of rise of the global mean sea level increases abruptly from 2.9 ± 0.22 mm yr−1 over 1993–2011 to 4.1 ± 0.25 mm yr−1 over 2012–2024. Abrupt trend changes in numerous climate parameters have also been reported in the early 2010s, suggesting a more global phenomenon. Internal climate variability is likely the main driver of the early 2010s sharp change observed in sea level and components, although one cannot totally exclude any additional contribution from increased radiative forcing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As an essential climate variable, sea level rise is a most significant response to climate change, whose global mean rate has been increasing throughout the 21st Century1. A recent global study dedicated to interannual variations of sea level at a set of 1100+ virtual coastal stations derived from reprocessed satellite altimetry data and that are well distributed along the world coastlines revealed an abrupt step change in many coastal regions during the 2008–2012 time span2. Further investigation based on gridded altimetry data showed that this step change is not limited to the coast but is also observed offshore in the open ocean sea level, thus having a large-scale signature2. It corresponds to a steep increase in sea level beyond 2010–2011. Recent regional studies also found evidence of an abrupt change in sea level trend around the same date, e.g., along the coasts of southeast US and Gulf of Mexico3,4,5,6, as well as in the South China Sea7.

Such trend changes reported in coastal and regional sea level studies raise the question of a more global phenomenon. In fact, several recent articles (presented in detail in the “Discussion” section) have reported change in trends (also called regime shifts by the authors) between 2008 and 2012 in a broad variety of climate parameters, either at global or regional scale (e.g., atmospheric circulation, precipitation, terrestrial water storage, ocean heat content, sea surface temperature, etc.). Possible drivers (i.e., internal climate variability, change in radiative forcing or a combination of both) have been proposed to explain such abrupt changes in trends.

The objective of the present study is to analyze simultaneously the global mean sea level (GMSL) record from satellite altimetry (since the early 1990s) and its components (ocean thermal expansion, ocean mass change and individual mass components such as terrestrial water storage and land ice), in order to check whether the corresponding time series also display an abrupt trend change in the early 2010s. Two different change-point detection methods are applied to the GMSL and components time series to precisely determine the timing of the abrupt trend change. Our results show that the GMSL evolution over the altimetry era is better explained by two linear trends with a change point in early 2010s, rather than by a steady acceleration over the past 30 years, as considered in several recent published articles. The “Discussion” section addresses the issue of a regime shift that occurred quasi globally in the climate system in early 2010s and of potential drivers of this event.

Depending on the data availability, different periods are considered: 1993-present (satellite altimetry era), 2002-present (GRACE/GRACE Follow-On space gravimetry era) and 2005-present (Argo era).

Results

Our study shows that the GMSL rise derived from satellite altimetry over 1993-present, displays a clear change in trend between 2010 and 2012, with a larger trend beyond that date (the rate of rise is estimated to 2.9 ± 0.22 mm yr−1 and 4.1 ± 0.25 mm yr−1 over the two periods 1993–2011 and 2012–2024). To precisely locate in time the occurrence of the change in trend, we use two different methods dedicated to detect transitions or discontinuities, hence estimate the probability of a trend change in time series over a given short time span: (1) the Bayesian Estimator of Abrupt Change, Seasonal and Trend (BEAST)8, and (2) the DiscoTimeS, a method developed to detect seasonal signals, discontinuities, and trend changes in geophysical time series with varying noise characteristics9 (https://github.com/oelsmann/discotimes). Like BEAST, DiscoTimeS is a fully Bayesian approach that decomposes the signal into piecewise linear trend segments separated by change points, where both the number and locations of change points are treated as unknown variables. While the two models are conceptually similar, they differ in several key aspects, as described in the “Method” section. Their structural differences justify the used of these two methods to enhance confidence in the results. As shown below, the two methods give similar results.

Two configurations are considered for each case: (1) no detrending of the time series, (2) long-term linear trend removed.

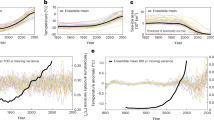

Figure 1a-d show the results for the GMSL time series using the BEAST method, with and without the long-term trend. In the first case (no detrending of the time series, Fig. 1a, b), a change in trend is detected, with 95% probability of occurrence between mid-2011 and end 2012. Looking at the detrended GMSL time series (Fig. 1c, d), years 2011–2012 clearly separates two distinct quasi-linear trends, with a steeper GMSL rise afterward.

a Original altimetry-based GMSL time series. b Probability of trend change with a peak at 2012.08 (black cross) and a total probability of 95% between 2011.45 and 2012.96. c Linearly detrended GMSL. d Probability of trend change with a peak at 2012.08 (black cross) and a total probability of 99% between 2011.40 and 2013.03. Orange lines represent linear trends.

Like for BEAST, the DiscoTimeS method is applied to both original and detrended GMSL time series (Figs. 2 and 3). For the original and linearly detrended GMSL time series, DiscoTimeS detects change points at about the end of 2010, overall aligning with the change points detected by BEAST for the late 2011-early 2012 period. DiscoTimeS identifies the change in GMSL trend about 1-year earlier than the BEAST method, but the results remain coherent.

a original GMSL time series. b shows the posterior distribution of the timing of the estimated change points with a mean value on 22th of September, 2010 and 18th of August, 1995. c, d are the same as (a, b) but for the linearly detrended GMSL. In (d), the timing of the changepoint is estimated at 28th of September, 2010. Orange lines represent linear trends.

The left column shows the GMSL time series (blue) with (from top to bottom) three different deterministic models (orange): a offset + linear trend, c offset + linear + quadratic acceleration, and e offset + piecewise linear trend with a breakpoint on 31 December 2011. The right column shows the same observations/models but with the linear trend removed. b offset + linear trend, d offset + linear + quadratic acceleration, and f offset + piecewise linear trend with a breakpoint on 31 December 2011 The shaded areas on the left and right columns correspond to the GMSL data uncertainty62.

An important question is whether the two linear trend (piecewise) model is a better choice to describe the GMSL time series compared to the model with a single linear trend, or to a model with a trend and an acceleration term (quadratic function). In effect, in a number of studies, the recent evolution of the altimetry-based GMSL is interpreted in terms of an acceleration over the altimetry era, estimated via a quadratic function10,11,12,13. Such an acceleration was reported over time spans longer than for the altimetry record in reconstructed past sea level time series14. However, as shown here, over the altimetry era, the GMSL record may alternately be interpreted as two successive linear trends separated by a shift around 2010–2012, followed by an increased rate of rise.

To test the significance of the GMSL trend change around 2010–2012 as suggested by both BEAST and DiscoTimeS Bayesian trend change estimators, we statistically compare three GMSL models: (1) a single long-term linear trend, (2) a quadratic function representing an acceleration, and (3) two successive linear trends with an abrupt trend change at 31 December 2011. These three models are illustrated in Fig. 3.

For each model, we use the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC)15, a measure of model complexity (number of parameters) and model-likelihood. The AIC is a model selection metric that balances goodness of fit and model complexity, defined as: AIC = 2k -2ln(L), where k is the number of parameters and L is the maximized likelihood of the model. We also consider the Bayesian information criteria (BIC)16 expressed as BIC = −2ln(L) + kln (N), where N is the sample number of the time series. Lower AIC and BIC indicate a better model. Results are presented in Table 1. It is worth mentioning that all trend calculations presented here account for the autocorrelation of the considered time series (the procedure is explained in detail in the “Method” section). As shown in Table 1, we find that across all criteria, the third model (based on piecewise trends) is the best-performing one. It is associated with the lowest AIC and BIC criteria, and the lowest root mean square error (RMSE) of model residuals.

We next examine climate parameters related to sea level in order to check whether an abrupt trend change is present in one or several parameters. Present-day GMSL rise has two main contributions1,17: ocean thermal expansion (called thermosteric sea level) and ocean mass change (also called barystatic sea level). Ocean mass variations result from ice sheets and glacier ice mass variations, with a contribution from exchange of water with continental river basins. Melting of land ice bodies leads to increase in ocean mass. Concerning terrestrial waters, increase of total water storage on land causes the ocean mass to decrease (and inversely) because of conservation of total water mass in the Earth system (considering the negligible contribution of the atmospheric reservoir). We analyzed time series of thermosteric and of ocean mass in order to detect possible changes in trend. Because the BEAST and DiscoTimeS methods give similar results, only results with BEAST are shown. These are presented in Figs. 4 and 5. As for the altimetry-based GMSL, a significant change in trend is observed around early 2012.

a Original time series. b Probability of trend change with a peak at 2013.0 (black cross) and a total probability of 99% between 2012.6 and 2013.3. c Linearly detrended thermosteric sea level. d Probability of trend change with a peak at 2013.0 (black cross) and a total probability of 100% between 2012.6 and 2013.4. Orange lines represent linear trends.

a Original barystatic sea level. b Probability of trend change with a peak at 2012.17 (black cross) and a total probability of 100% between 2012.0 and 2012.33. c Linearly detrended barystatic sea level. d Probability of trend change with a peak at 2012.17 (black cross) and a 100% probability of change between 2012.0 and 2012.33. Orange lines represent linear trends.

From Figs. 1, 2, 4 and 5, we note that the GMSL and its thermosteric and barystatic contributions show a clear change in trend around 2011–2012. This is also what we observe in total ocean heat content (OHC) that also displays a shift in late 2011- early 2012 (Fig. 6).

a Original OHC time series. b Probability of trend change with a peak at 2011.83 (black cross) and a total probability of 100% between 2010.47 and 2012.02. c Linearly detrended OHC. d Probability of trend change with a peak at 2011.83 (black cross) and a total probability of 95% between 2010.65 and 2012.03. Orange lines represent linear trends.

We further consider individual mass components that contribute to the ocean mass component. Figure 7 shows the terrestrial water storage (TWS) contribution based on GRACE/GRACE Follow-On observations since 2002, and expressed in terms of water height on land (hence a decrease in TWS corresponds to an increase of the GMSL). Note that the TWS time series used here includes the glaciers (but not the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets). As for the GMSL and barystatic component, a change in trend is detected late 2011.

a Original time series. b Probability of trend change with a peak at 2011.83 (black cross) and a total probability of 99% between 2011.41 and 2012.9. c Linearly detrended time series. d Probability of trend change with a peak at 2011.83 (black cross) and a total probability of 95% between 2011.28 and 2013.29. Orange lines represent linear trends.

The land ice contributions (ice sheets and glaciers) are also analyzed. Although the ice mass balance time series are available since 1993, time series start in 2005 as for the thermosteric sea level. Corresponding trend changes, based on the BEAST method, are shown in Supplementary Figs. S1 and S2. For both glaciers and ice sheets, there no clearly defined trend change, although BEAST detects some change in late 2011 for the total ice sheet cumulative mass balance and around 2015 for the glaciers. This would suggest that the late 2011-early 2012 shift detected in the TWS is mostly due to the liquid water bodies (surface waters, soil moisture and ground waters) rather than to the glaciers, and that the shift in the GMSL is dominated by both the thermosteric and (liquid) TWS, and to a lesser extent to ice sheet melting.

In Supplementary Table S1 are gathered trend change dates detected in the GMSL and components time series by the two methods. Median dates and associated confidence intervals (95–100% probability) are reported. This summary illustrates the temporal coherence of the computed regime shifts across components of the sea level budget and methods.

Table 2 summarizes trends and associated standard errors (allowing for auto correlation of the time series) of the GMSL, thermosteric and barystatic time series. before and after 31 December 2011.

We further examine the GMSL budget over the common time span (2005–2020) of the three terms of the sea level budget, in order to check whether the piecewise model also fits better the sum of the thermosteric and barystatic components. Supplementary Fig. S3 shows the GMSL budget over 2005–2020. We applied BEAST to the sum of component time series (Fig. 8). A significant trend change is found in early 2012, in agreement with the GMSL case. As for the GMSL, we also compared the sum of components time series to a quadratic function and piecewise model. Corresponding residuals are 2.72 mm and 2.48 mm for the acceleration and piecewise models, respectively. Although the difference is small, the piecewise model is still preferred for the sum of components.

a Original sum of components time series. b Probability of trend change with a peak at 2012.25 (black cross) and a total probability of 100% between 2012.09 and 2012.82. c Linearly detrended time series. d Probability of trend change with a peak at 2012.25 (black cross) and a total probability of 99% between 2012.09 and 2012.85. Orange lines represent linear trends.

Discussion

While the GMSL evolution is currently interpreted as a steady acceleration over the altimetry era, here we suggest that it can be also robustly explained by two linear trends with a change point in the early 2010s. This is also observed in the GMSL components. Such an abrupt trend change may reflect a regime shift, i.e., a rapid transition from a given state to another18,19. If the former state corresponds to a period of about 10–15 years (as in the present study), the transition to the other state is expected to occur over ~1–2 years18,19.

The recent literature presents several pieces of evidence of abrupt trend changes (or regime shift) in climate in the early 2010s, both at global and regional scales.

Several articles report abrupt trend changes in the water cycle. For example, a trend change in the global mean TWS is found around early 201220, in agreement with our results. A trend change is also seen in precipitation data that is partly attributed to a change in trend of the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) index (defined as the leading mode of the Empirical Orthogonal Function decomposition of the Pacific sea surface temperature/SST, north of 20°N). Regional changes around 2011–2012 in other parameters of the water cycle have also been reported worldwide, e.g., in precipitation and TWS in central Mongolia21, in extreme floods in the Delaware river basin22, and in summer monsoon in North India23.

Other studies have shown that the summer atmospheric circulation in the Northern hemisphere has undergone a significant shift in the recent decades, particularly around 2011, coinciding with increased episodes of blocking events over Greenland, leading to increased surface ice melt24. Such a regime shift has been related to a dominant negative phase of the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO). An abrupt increase in Greenland melt has been reported for 2012, especially in south-western part of the ice sheet25, confirming results of a previous study26.

Abrupt trend changes have also been observed in some ocean parameters. Using in synergy ocean model simulations and observations, a change in trend of the AMOC (Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation) was detected in the early 2010s27, and interpreted as a pause in the AMOC weakening, driven by NAO- related enhanced natural variability. An abrupt regime shift in the North Pacific SST was found around 201328, with an increased SST rate beyond that date. The authors correlate the North Pacific regime shift in SST to a change in the atmospheric circulation, coinciding with an intensification of a positive winter Arctic Oscillation (AO). This North Pacific SST increase around 2013 echoes the recent finding29 that reports an accelerated global SST warming since 1985, but with a clear change in trend beyond 2010 (see their Fig. 2a). Another study30 based on ocean temperature data, shows that after a decade of warming, the Southern Oceans have cooled in certain regions after 2012. According to the authors, this shift is driven by changes in the Southern Annual Mode (SAM) and Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation (IPO). Finally, observed shifts in the early 2010s are not limited to physical parameters. For example, a proliferation of pelagic Sargassum is observed in the tropical Atlantic since 2011, attributed to a NAO-driven ocean mass transport anomaly and strong vertical mixing in this region31.

As summarized by the above discussion, the observed regime shift observed a number of climate parameters in the early 2010s seem clearly linked to internal climate variability within the coupled atmosphere-ocean system, i.e., changes in the PDO, NAO, AO, SAM, or IPO depending on regions and parameters.

Our study confirms the dominant influence of the PDO on the decadal fluctuations of the Pacific sea level, at least until 2018. This is illustrated in Fig. 9 that shows the linearly detrended Pacific sea level time series over 1993–2024, with the PDO superimposed. Over most of the altimetry era, the decadal variations of the Pacific sea level are well correlated to the PDO index (correlation of 0.7 between 1993–2018), with changes in trend of the Pacific sea level coinciding with changes in trend of the PDO. Note however that beyond 2018, the correlation breaks down, suggesting that another process is taking over the PDO. Whether still driven by the internal climate variability or due to external forcing factors is an open question.

It is worth mentioning that some studies have reported a change in the global radiative forcing over the recent years32,33,34,35. While two of these studies32,33 consider the past two decades together, using CERES (Clouds and the Earth’s Radiant Energy System) observations of the net energy flux at the top of the atmosphere, a study34 showed that anthropogenic radiative forcing increased around 2010, from 0.4 W m−2 over 2000–2009 to 0.6 W m−2 over 2010–2019. Note that the ocean heat uptake time series35 also presents a steep increase around 2011 (Fig. 7 of ref. 35), in agreement with our results. The global mean surface temperature rise has doubled over the two successive decades (2000–2009 and 2010–2019)34, from 0.18 °C per decade to 0.35 °C per decade. The first decade corresponds to the so-called ‘Pause in global warming’ (also called “Hiatus”), largely documented in the literature36,37,38, and mostly attributed to internal climate variability related to a decreasing trend of the PDO and a succession of La Nina events (cold phase of ENSO). Observations and model studies have suggested that this particular configuration caused wind-driven cooling of the eastern Pacific surface waters with large impacts on the global climate, including heat uptake by the deep ocean and reduced surface warming39,40,41,42,43,44.

While the end of the pause in global warming could still be also internal variability, it is worth noting that it coincides with an increase in effective radiative forcing related to a significant reduction of aerosols emissions34. Aerosols inventories indeed reveal significant reduction of aerosols emissions in many regions of the world during the past two decades45,46, especially in China, where a reduced aerosol emission trend has been observed after 2010. Ground-based measurements also show decline of atmospheric nitrogen deposition over China since 201047. Similarly, a shift is observed in inorganic aerosols formation and nitrogen deposition over the United States in 201148. The increase in the Earth energy imbalance beyond 2010–2011 may not only result from reduced aerosols emissions29 but possibly also from additional mechanisms related to cloud and sea ice feedbacks49. Another study50 indeed shows a clear shift in trend in the anthropogenic effective radiative forcing around 2012, of 0.9 W m−2 in terms of Earth energy imbalance over the 2010–2022 time span, corresponding to an increased warming rate of ~0.2 °C per decade.

If we go back in time (before the altimetry era), a number of past regime shifts have been reported in the literature51. In particular, the notable 1976/77 climate shift that has been the subject of numerous studies19,52,53,54,55,56,57. This event exhibited basin-scale SST anomalies, a phase change in the PDO and IPO, persistent modifications to the Walker circulation and tropical Pacific zonal SST gradients. Thus, internal variability is clearly favored to explain the 1976/77 climate shift.

From the above discussion, and recalling that the increased rate of change in the GMSL and in some of its components as of the early 2010s corresponds to the termination of the so-called ‘Pause in global warming’ that affected the 2000s decade, we would also favor internal climate variability related to a trend change of the PDO combined with a strongly negative NAO to explain the shift observed across numerous climate parameters at this epoch. However, we cannot exclude that an increase in anthropogenic radiative forcing related to a reduction of aerosols emissions has also played some role. Attribution studies using coupled climate models are definitely needed to further investigate the exact causes of the early 2010s abrupt change in climate.

As a final note, we briefly discuss the relative shortness of the GMSL time series used in this study, since it raises the question of the robustness of our results. The early 2010s trend change observed in the GMSL is indeed constrained by an observational window of only 30 years (the current duration of the high precision altimetry era). We tested a longer time series using an historical mean sea level reconstruction58. This reconstruction (of annual resolution) is based on tide gauge records and incorporates prior knowledge about physical processes from ancillary observations and geophysical models. Here we limit the reconstructed time series to 1980-present because prior 1980, the sparseness of the tide gauge network increases the data uncertainty. We applied BEAST to this time series (see Supplementary Fig. S4) and still find an abrupt trend change in the early 2010s. Because the historical sea level reconstruction is essentially based on tide gauge data and covers a 40-year long time span, it confirms the robustness of the abrupt trend change reported in the satellite altimetry-based sea level record. But, we are well aware that the early 2010s trend change event observed among several climate parameters should be interpreted in a cautionary sense: a robust, multi-component reorganization within the climate system, supported by empirical evidence, while acknowledging that its climatic persistence and underlying mechanisms are still unknown. In addition, we do not claim that the early 2010 event necessarily reflects anthropogenic climate change. Our discussion rather favors internal climate variability. But as mentioned above, one cannot however totally exclude any contribution from increased radiative forcing. Definitely, deeper investigations are required to elucidate this important question.

Methods

Data

Global mean sea level

For the GMSL, we use satellite altimetry data based on the most recent DT2024 reprocessing of the TOPEX/Poseidon and Jason missions59. This data set is available from the Copernicus Climate Change Service (https://climate.copernicus.eu). It covers the period January 1993 to December 2024. The seasonal signal is removed, and a 6-month smoothing is applied. The Glacial Isostatic Adjustment correction is applied (of −0.3 mm yr−1 in terms of global mean60). A wet tropospheric correction is also applied to account for the radiometer drift onboard the Jason-3 satellite61. The original 10-day time series data is resampled at a monthly interval. Note that the DT2024 GMSL record is a recently released version of the previous DT2021 sea level record available from AVISO. Both data sets differ very little except during the first 6 years of the record where the TOPEX-A instrumental drift is corrected in DT2021 and not in DT2024, because the reprocessing of the TOPEX/Poseidon mission in the latter data set is supposed to account for this instrumental drift correction59. However, whether a TOPEX-A drift needs to be applied to the DT24 record or not remains unclear. Its impact on the GMSL trend of the first years of the altimetry record is significant: E.g., the GMSL trend estimated over January 1993 to December 2011 amounts to 2.65 mm yr−1 for DT2021 and 2.9 mm yr−1 for DT2024. For the Pacific Ocean, we also used altimetry-based gridded sea level time series from the Copernicus Climate Change Service (https://climate.copernicus.eu), with the Jason-3 radiometer drift correction also applied. For both DT2021 and DT2024 data sets, data uncertainties are accounted for62.

Thermosteric sea level

We consider five ocean temperature data sets from: (1) the Scripps Institution of Oceanography (SIO)63, (2) the International Pacific Research Center (IPRC, https://apdrc.soest.hawaii.edu/projects/Argo/), (3) JAMSTEC64, (4) EN4, version 2.265 and (5) ISAS (In Situ Analysis system)66,67. These data sets are mostly based on Argo monthly gridded temperature data at 1° × 1° resolution and different depth levels until 2000 m. For all data sets, the gridded thermosteric sea level is computed from the gridded data using the Lenapy library (https://github.com/CNES/lenapy) from the Centre National d’Études Spatiales (CNES), based on the Gibbs seawater oceanography toolbox of the 2010 Thermodynamic Equation Of Seawater (TEOS-10). We further globally average the five gridded thermosteric data sets to provide an ensemble mean thermosteric time series for the 0–2000 m ocean depth layer. The data uncertainties are based on the dispersion of the five time series around their mean.

Ocean mass

We use the barystatic (i.e., the global mean ocean mass) variable from the AVISO Ocean Heat Content-Earth Energy Imbalance (OHC-EEI) extended dataset v568. This variable represents the global mean ocean mass and associated uncertainty. It is based on a GRACE/GRACE Follow-On ensemble of 120 solutions69 as of 2002, and it is extended back in time with the ESA’s SLBC_CCI data set70 that estimated the global mean ocean mass from individual mass contributions. The time series covers the period January 1993 to May 2022.

Ocean heat content

We also use the OHC variable from the AVISO OHC-EEI extended dataset v5 (Magellium/LEGOS71). It is computed using the altimetry-based sea level corrected for the barystatic component68, a measure of the full depth thermosteric sea level, from which the OHC is derived. This OHC data set is supposed to sample the full ocean depth from surface to bottom. It covers the period January 1993 to May 2022.

Ice sheet mass balance

We use the ice sheet cumulative mass balance data from the IMBIE project72,73 (https://climate.copernicus.eu/climate-indicators/ice-sheets). This dataset provides at monthly interval cumulative mass change and associated uncertainty for the Antarctic and the Greenland ice sheets and their sum between 1992 and 2020. The data are reconciled estimates of mass balance from three independent satellite-based techniques: altimetry, gravimetry and input-output method.

Global glacier mass balance

The glaciers dataset used here is the Glacier Mass Change Gridded Data from 1976 to Present74, derived from the Fluctuations of Glaciers (FoG) Database. The dataset consists of global annual glacier mass changes (in Gt) distributed on a global regular grid at 0.5° resolution based on the FoG database of the World Glacier Monitoring Service. Gridded data from the hydrological year 1992–1993 to hydrological year 2021–2022 are averaged globally to obtain a global mean glacier time series.

Terrestrial water storage

For TWS, we consider the GRACE/GRACE-FO dataset from GFZ75,76. The Level 3 version used here is based on the GFZ RL06 Level-2B product77. The total TWS time series is obtained by averaging the 1° × 1° grids over all continental regions, excluding Greenland and Antarctica. As a result, it includes the glacier contribution. The time series covers the period April 2002 to December 2024.

Method

Several approaches have been developed for detecting transitions and discontinuities in climate records78,79,80,81. In this study, we apply two methods: (1) the Bayesian estimator of abrupt changes in trends in time series (BEAST)8, (2) the DiscoTimeS method9. We further check the results using a linear regression method. These three methods are briefly described below.

Bayesian estimator of abrupt change in trend

The Bayesian Estimator of Abrupt change, Seasonal change and Trend (BEAST)8 detects changes in trends by modeling the time series as an addition of seasonal, trend, and noise components. This kind of tool combines Bayesian algorithms that give a good balance between managing complexity and moderate computational needs, with Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC)-based stochastic sampling techniques that improve the detection reliability and robustness80. The method has been compared with other change point detection tools and has been shown to have high detection accuracy82. The code is in open access and available as a Python package (https://github.com/zhaokg/Rbeast).

The same configuration is used here for all the time series. In the figures presented, the minimum separation time interval between two neighboring trend change points (called trend segment8) is constrained to 8 years to avoid changes point detection from 1 year to another. In addition to the 8-years nominal case, different tests have been performed on the GMSL variable, using 4, 6, 10, and 12 years for the trend segment, to check the influence of this parameter (Supplementary Figs. S5–S8).

An additional test was performed using the DT2021 data set for the GMSL instead of DT2024, with a 8-year trend segment (Supplementary Fig. S9). Results are similar to the DT2024 case.

In all cases, an ensemble of 100 MCMC is computed to obtain a robust estimate of the change point (tests using 1000 MCMC ensemble give similar results, suggesting rapid convergence and a clearly identifiable change point).

The BEAST method is applied to both original and detrended time series. In the latter case, a linear trend is computed by a least-squares fit and removed from the time series. When a seasonal signal is present in the time series, the BEAST tool is used to compute and further remove it.

DiscoTimeS: a method to detect change points in geophysical time series

DiscoTimeS is a fully Bayesian method developed to detect seasonal signals, discontinuities, and trend changes in geophysical time series with varying noise characteristics9 (https://github.com/oelsmann/discotimes). BEAST and DiscoTimeS differ in several key aspects: the MCMC algorithms only used in BEAST, the formulation of hyperparameters, and the specification of prior distributions. For example, DiscoTimeS uses discrete Bernoulli priors for the number of changepoints, whereas BEAST assumes a uniform prior. Additionally, BEAST enforces a minimum spacing between change points, a constraint not applied in DiscoTimeS. For DiscoTimeS, we perform 4000 iterations using the No-U-Turn (NUTS) sampler83. We run four different chains and select the best performing model among the members of this ensemble based on the Pareto-smoothed importance sampling leave-one-out cross-validation (PSIS-LOO) parameter84.

Linear regression accounting for autocorrelation

Although both Bayesian trend change estimators described above indicate significant shifts around the 2010–2012 period, the simplest method to test the significance of a trend change is to compare two simple linear regression models: one with a trend change and one without. The piecewise trend change model for our observations y is:

where:

And where:

-

x is a vector containing n time steps,

-

\({\beta }_{0}\) is the intercept,

-

\({\beta }_{1}\) is the slope before the breakpoint x0,

-

\({\beta }_{2}\) is the slope after the breakpoint,

-

ε∼N(0, σ2) is the error term (assuming white noise) or ε = pεt -1 +kt, kt∼N(0, σk2) for a first-order autoregressive (AR) process, the lag-1 AR coefficient p

Accounting for autocorrelation in the residuals is important because correlation reduces the effective sample size and therefore increases the uncertainties in the estimated parameters. It also has an effect on model comparison statistics, such as AIC and BIC, which are influenced by the number of parameters, and the magnitude of the residuals. The correlation coefficients (for first- and second-order autoregressive (AR) processes) are iteratively estimated from the residuals using the Yule-Walker method. The AR(x) coefficients influence the parameter uncertainties via the covariance matrix of the residuals, which becomes a function of the AR(x) coefficients and has non-zero off-diagonal entries. To estimate the best-performing model, i.e., the model with the most likely changepoint timing, we fit the model using ordinary least-squares, by iterating x0 over all possible time steps. Then we compute the variance of the residuals, assuming that the best model is the one with the lowest residual variance. The results are illustrated in Fig. 10.

In (a), the black line represents the most-likely model, the blue line shows the detrended GMSL. The gray lines represent all possible realizations, with transparency scaled by (sigma2)5. b shows the variance of the residuals (y - ymodel), as well as the timing where the lowest variance is obtained (December 31st, 2011).

Data availability

The DT2024 gridded altimetry data set is available from the Copernicus web site (https://climate.copernicus.eu (https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.4c328c78)). The DT2021 global mean sea level time series is available at https://www.aviso.altimetry.fr/en/data/products/ocean-indicators-products/mean-sea-level/data-acces.html. The Argo data are available from the https://sio-argo.ucsd.edu and https://apdrc.soest.hawaii.edu/projects/argo websites. The OHC data are available from Magellium/LEGOS at https://doi.org/10.24400/527896/A01-2020.003. The glacier mass balance data are available from Copernicus at https://doi.org/10.24381/CDS.BA597449. The IMBIE ice sheet mass balance is available at https://doi.org/10.5285/77B64C55-7166-4A06-9DEF-2E400398E452.

References

IPCC. Climate Change 2021—The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896 (Cambridge University Press, 2021).

Leclercq, L. et al. Spatio-temporal changes in interannual sea level along the world coastlines. Glob. Planet. Chang. 253, 104972 (2025).

Dangendorf, S. et al. Acceleration of U.S. Southeast and Gulf Coast sea-level rise amplified by internal climate variability. Nat. Commun. 14, 1935 (2023).

Yin, J. Rapid decadal acceleration of sea level rise along the US East and Gulf coasts during 2010–22 and its impact on hurricane-induced storm surge. J. Clim. 36, 4511–4529 (2023).

Steinberg, J. M., Piecuch, C. G., Hamlington, B. D., Thompson, P. R. & Coats, S. Influence of deep-ocean warming on coastal sea-level decadal trends in the Gulf of Mexico. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 129, e2023JC019681 (2024).

Leclercq, L. et al. Coastal sea level rise at altimetry-based virtual stations in the Gulf of Mexico. Adv. Space Res. 75, 1636–165275 (2025).

Cheng, X. et al. Regime shift of the sea level trend in the South China Sea modulated by the tropical Pacific decadal variability. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2022GL102708 (2023).

Zhao, K. et al. Detecting change-point, trend, and seasonality in satellite time series data to track abrupt changes and nonlinear dynamics: a Bayesian ensemble algorithm. Remote Sens. Environ. 232, 111181 (2019).

Oelsmann, J. et al. Bayesian modelling of piecewise trends and discontinuities to improve the estimation of coastal vertical land motion: DiscoTimeS: a method to detect change points in GNSS, satellite altimetry, tide gauge and other geophysical time series. J. Geod. 96, 62 (2022).

Dieng, H. B., Cazenave, A., Meyssignac, B. & Ablain, M. New estimate of the current rate of sea level rise from a sea level budget approach. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 3744–3751 (2017).

Nerem, R. S. et al. Climate-change–driven accelerated sea-level rise detected in the altimeter era. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 115, 2022–2025 (2018).

Guérou, A. et al. Current observed global mean sea level rise and acceleration estimated from satellite altimetry and the associated measurement uncertainty. Ocean Sci. 19, 431–451 (2023).

Hamlington, B. D. et al. The rate of global sea level rise doubled during the past three decades. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 1–4 (2024).

Dangendorf, S. et al. Persistent acceleration in global sea-level rise since the 1960s. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 705–710 (2019).

Akaike, H. Information Theory and an Extension of the Maximum Likelihood Principle. in Selected Papers of Hirotugu Akaike (eds Parzen, E., Tanabe, K. & Kitagawa, G.) 199–213 (Springer, 1998).

Schwarz, G. Estimating the dimension of a model. Ann. Stat. 6, 461–464 (1978).

IPCC. Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate (eds Pörtner, H.-O. et al.) 755 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 2019).

Rodionov, S. N. A sequential algorithm for testing climate regime shifts. Geophys. Res. Lett. 31, L09204 (2004).

Overland, J., Rodionov, S., Minobe, S. & Bond, N. North Pacific regime shifts: definitions, issues and recent transitions. Prog. Oceanogr. 77, 92–102 (2008).

Buzzanga, B., Hamlington, B., Fasullo, J., Landerer, F. & Peidou, A. Interdecadal variability of terrestrial water storage since 2003. Commun. Earth Environ. 6, 1–9 (2025).

Zhang, X. et al. Understanding the shift in drivers of terrestrial water storage decline in the central Inner Mongolian steppe over the past two decades. J. Hydrol. 636, 131312 (2024).

Sun, N. et al. Amplified extreme floods and shifting flood mechanisms in the Delaware River Basin in future climates. Earth’s. Future 12, e2023EF003868 (2024).

Subrahmanyam, K. V. et al. Regional shift in the peak time of maximum Indian summer monsoon rainfall in recent decades. Geophys. Res. Lett. 52, e2024GL112697 (2025).

Preece, J. R. et al. Summer atmospheric circulation over Greenland in response to Arctic amplification and diminished spring snow cover. Nat. Commun. 14, 3759 (2023).

Graversen, R. G., Heiskanen, T., Bintanja, R. & Goelzer, H. Abrupt increase in Greenland melt enhanced by atmospheric wave changes. Clim. Dyn. 62, 7171–7183 (2024).

Nghiem, S. V. et al. The extreme melt across the Greenland ice sheet in 2012. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L20502 (2012).

Lee, S.-K. et al. A pause in the weakening of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation since the early 2010s. Nat. Commun. 15, 10642 (2024).

Xiao, D. & Ren, H.-L. A regime shift in North Pacific annual mean sea surface temperature in 2013/14. Front. Earth Sci. 10, 2022 (2023).

Merchant, C. J., Allan, R. P. & Embury, O. Quantifying the acceleration of multidecadal global sea surface warming driven by Earth’s energy imbalance. Environ. Res. Lett. 20, 024037 (2025).

Wang, L. et al. Recent shift in the warming of the southern oceans modulated by decadal climate variability. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2020GL090889 (2021).

Jouanno, J., Berthet, S., Muller-Karger, F., Aumont, O. & Sheinbaum, J. An extreme North Atlantic Oscillation event drove the pelagic Sargassum tipping point. Commun. Earth Environ. 6, 1–11 (2025).

Loeb, N. G. et al. Satellite and ocean data reveal marked increase in Earth’s heating rate. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL093047 (2021).

Kramer, R. J. et al. Observational evidence of increasing global radiative forcing. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2020GL091585 (2021).

Jenkins, S. et al. Is Anthropogenic global warming accelerating?. J. Clim. 35, 7873–7890 (2022).

Hakuba, M. Z. et al. Trends and variability in Earth’s energy imbalance and ocean heat uptake since 2005. Surv. Geophys 45, 1721–1756 (2024).

Trenberth, K. E. & Fasullo, J. T. An apparent hiatus in global warming. Earth’s. Future 1, 19–32 (2013).

Smith, D. Has global warming stalled. Nat. Clim. Chang. 3, 618–619 (2013).

Fyfe, J. C. et al. Making sense of the early-2000s warming slowdown. Nat. Clim. Chang. 6, 224–228 (2016).

Meehl, G. A., Arblaster, J. M., Fasullo, J. T., Hu, A. & Trenberth, K. E. Model-based evidence of deep-ocean heat uptake during surface-temperature hiatus periods. Nat. Clim. Chang. 1, 360–364 (2011).

Kosaka, Y. & Xie, S.-P. Recent global-warming hiatus tied to equatorial Pacific surface cooling. Nature 501, 403–407 (2013).

Watanabe, M. et al. Strengthening of ocean heat uptake efficiency associated with the recent climate hiatus. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 3175–3179 (2013).

England, M. H. et al. Recent intensification of wind-driven circulation in the Pacific and the ongoing warming hiatus. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 222–227 (2014).

Nieves, V., Willis, J. K. & Patzert, W. C. Recent hiatus caused by decadal shift in Indo-Pacific heating. Science 349, 532–535 (2015).

Trenberth, K. E. Has there been a hiatus. Science 349, 691–692 (2015).

Quaas, J. et al. Robust evidence for reversal of the trend in aerosol effective climate forcing. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 12221–12239 (2022).

Hodnebrog, O. et al. Recent reductions in aerosol emissions have increased Earth’s energy imbalance. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 166 (2024).

Liu, L., Wen, Z., Liu, S., Zhang, X. & Liu, X. Decline in atmospheric nitrogen deposition in China between 2010 and 2020. Nat. Geosci. 17, 733–736 (2024).

Pan, D. et al. Regime shift in secondary inorganic aerosol formation and nitrogen deposition in the rural United States. Nat. Geosci. 17, 617–623 (2024).

Allan, R. P. & Merchant, C. J. Reconciling Earth’s growing energy imbalance with ocean warming. Environ. Res. Lett. 20, 044002 (2025).

Forster, P. M. et al. Indicators of Global Climate Change 2022: annual update of large-scale indicators of the state of the climate system and human influence. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 15, 2295–2327 (2023).

Fraedrich, K., Gerstengarbe, F.-W. & Werner, P. C. Climate Shifts during the Last Century. Clim. Chang. 50, 405–417 (2001).

Miller, A. J., Cayan, D. R., Barnett, T. P., Graham, N. E. & Oberhuber, J. M. The 1976-77 climate shift of the Pacific ocean. Oceanography 7, 21–26 (1994).

Trenberth, K. E. & Hurrell, J. W. Decadal atmosphere-ocean variations in the Pacific. Clim. Dyn. 9, 303–319 (1994).

Wu, L., Lee, D. E. & Liu, Z. The 1976/77 North Pacific climate regime shift: the role of subtropical ocean adjustment and coupled ocean–atmosphere feedbacks. J. Clim. 18, 5125–5140 (2005).

Hartmann, B. & Wendler, G. The significance of the 1976 Pacific climate shift in the climatology of Alaska. J. Clim. 18, 4824–4839 (2005).

Xavier, A. K., Varikoden, H., Babu, C. A. & Reshma, T. Influence of PDO and ENSO with Indian summer monsoon rainfall and its changing relationship before and after 1976 climate shift. Clim. Dyn. 61, 5465–5482 (2023).

Xiao, D. Spatial–temporal characteristics of the atmospheric decadal abrupt changes around 2013 and their differences from those in the late 1970s. Clim. Dyn. 63, 118 (2025).

Dangendorf, S. et al. Probabilistic reconstruction of sea-level changes and their causes since 1900. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 16, 3471–3494 (2024).

Kocha, C. et al. 30 years of sea level anomaly reprocessed to improve climate and mesoscale satellite data record, https://ostst.aviso.altimetry.fr/programs/2023-ostst-complete-program, https://doi.org/10.24400/527896/a03-2023.3804 (2023).

Peltier, W.R., Argus, D. F. & Drummond, R. Comment on “An assessment of the ICE-6G_C (VM5a) glacial isostatic adjustment model” by Purcell et al. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 123, 2019–2028 (2018).

Brown, S., Willis, J. K. & Fournier, S. Jason-3 wet path delay correction. Ver. F. PO.DAAC, CA, USA, https://doi.org/10.5067/J3L2G-PDCOR (2023).

Prandi, P. et al. Local sea level trends, accelerations and uncertainties over 1993–2019. Sci. Data 8, 1 (2021).

Roemmich, D. & Gilson, J. The 2004–2008 mean and annual cycle of temperature, salinity, and steric height in the global ocean from the Argo Program. Prog. Oceanogr. 82, 81–100 (2009).

Hosoda, S., Ohira, T. & Nakamura, T. A monthly mean dataset of global oceanic temperature and salinity derived from Argo float observations. JAMSTEC Rep. Res. Dev. 8, 47–59 (2008).

Good, S. A., Martin, M. J. & Rayner, N. A. EN4: quality controlled ocean temperature and salinity profiles and monthly objective analyses with uncertainty estimates. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 118, 6704–6716 (2013).

Gaillard, F., Reynaud, T., Thierry, V., Kolodziejczyk, N. & von Schuckmann, K. In situ–based reanalysis of the global ocean temperature and salinity with ISAS: variability of the heat content and steric height. J. Clim. 29, 1305–1323 (2016).

Kolodziejczyk, N., Prigent-Mazella, A. & Gaillard, F. ISAS temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen gridded fields, SEANOE, https://doi.org/10.17882/52367 (2023).

Marti, F. et al. Monitoring the ocean heat content change and the Earth energy imbalance from space altimetry and space gravimetry. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 14, 229–249 (2022).

Blazquez, A. et al. Exploring the uncertainty in GRACE estimates of the mass redistributions at the Earth surface: implications for the global water and sea level budgets. Geophys. J. Int. 215, 415–430 (2018).

Horwath, M. et al. Global sea-level budget and ocean-mass budget, with a focus on advanced data products and uncertainty characterisation. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 14, 411–447 (2022).

Magellium/LEGOS. OHC/EEI from space: climate indicators: Ocean heat content and Earth energy imbalance. https://doi.org/10.24400/527896/A01-2020.003 (2023).

Shepherd, A. et al. Antarctic and Greenland Ice Sheet mass balance 1992-2020 for IPCC AR6. https://doi.org/10.5285/77B64C55-7166-4A06-9DEF-2E400398E452 (2021).

Otosaka, I. N. et al. Mass balance of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets from 1992 to 2020. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 15, 1597–1616 (2023).

Copernicus Climate Change Service. Glacier mass change gridded data from 1976 to present derived from the Fluctuations of Glaciers Database. https://doi.org/10.24381/CDS.BA597449 (2023).

Boergens, E., Dobslaw, H. & Dill, R. GFZ GravIS RL06 Continental Water Storage Anomalies. https://doi.org/10.5880/GFZ.GRAVIS_06_L3_TWS (2019).

Boergens, E. et al. Uncertainties of GRACE-based terrestrial water storage anomalies for arbitrary averaging regions. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 127, e2021JB022081 (2022).

Dahle, C. & Murböck, M. Post-processed GRACE/GRACE-FO Geopotential GSM Coefficients GFZ RL06 (Level-2B Product). https://doi.org/10.5880/GFZ.GRAVIS_06_L2B (2019).

Legates, D. R. & Outcalt, S. I. Detection of climate transitions and discontinuities by Hurst rescaling. Int. J. Climatol. 42, 4753–4772 (2022).

Beaugrand, G. Theoretical basis for predicting climate-induced abrupt shifts in the oceans. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 370, 20130264 (2015).

Maeng, H. & Fryzlewicz, P. Detecting linear trend changes in data sequences. Stat. Pap. 65, 1645–1675 (2024).

Gupta, M., Wadhvani, R. & Rasool, A. Comprehensive analysis of change-point dynamics detection in time series data: a review. Expert Syst. Appl. 248, 123342 (2024).

Li, J., Li, Z.-L., Wu, H. & You, N. Trend, seasonality, and abrupt change detection method for land surface temperature time-series analysis: evaluation and improvement. Remote Sens. Environ. 280, 113222 (2022).

Hoffman, M. D. & Gelman, A. The No-U-Turn sampler: adaptively setting path lengths in Hamiltonian Monte Carlo. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 15, 1593–1623 (2014).

Vehtari, A., Gelman, A. & Gabry, J. Practical Bayesian model evaluation using leave-one-out cross-validation and WAIC. Stat. Comput. 27, 1413–1432 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This study is partly funded by the ESA Climate Change Initiative Sea Level project (https://climate.esa.int/en/projects/sea-level). L.L. is supported by this project (grant number 4000126561/19/I-NB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.C. and L.L. designed the study. L.L. and J.O. analyzed the data. A.C., L.L., and J.O. wrote a first version of the manuscript. All co-authors, A.C., L.L., J.O., M.P., S.J., S.C., J.F.L., F.B., R.A., contributed to discussing the results, to editing and final writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks John Church, Christian Franzke and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Nicole Khan and Alice Drinkwater. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Leclercq, L., Oelsmann, J., Cazenave, A. et al. Abrupt trend change in global mean sea level and its components in the early 2010s. Commun Earth Environ 7, 130 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03149-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-03149-5