Abstract

Impaired T cell immunity with aging increases mortality from infectious disease. The branching of asparagine-linked glycans is a critical negative regulator of T cell immunity. Here we show that branching increases with age in females more than in males, in naive T cells (TN) more than in memory T cells, and in CD4+ more than in CD8+ T cells. Female sex hormones and thymic output of TN cells decrease with age; however, neither thymectomy nor ovariectomy altered branching. Interleukin-7 (IL-7) signaling was increased in old female more than male mouse TN cells, and triggered increased branching. N-acetylglucosamine, a rate-limiting metabolite for branching, increased with age in humans and synergized with IL-7 to raise branching. Reversing elevated branching rejuvenated T cell function and reduced severity of Salmonella infection in old female mice. These data suggest sex-dimorphic antagonistic pleiotropy, where IL-7 initially benefits immunity through TN maintenance but inhibits TN function by raising branching synergistically with age-dependent increases in N-acetylglucosamine.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

RNA-seq data has been deposited with the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE184496. The mouse 10mm reference genome was obtained from https://hgdownload.soe.ucsc.edu/downloads.html#mouse. Statistical source data is provided for all main and Extended Data Figures in the supplementary information. Additional data that support the findings within this article are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The code for differential analysis of RNA-seq data using R package DESeq2 has been uploaded to a github repository and can be found at https://github.com/ucightf/demetriou.

References

Goronzy, J. J. & Weyand, C. M. Mechanisms underlying T cell ageing. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 19, 573–583 (2019).

Nikolich-Zugich, J. The twilight of immunity: emerging concepts in aging of the immune system. Nat. Immunol. 19, 10–19 (2018).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Estimates of deaths associated with seasonal influenza—United States, 1976–2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 59, 1057–1062 (2010).

Wiersinga, W. J., Rhodes, A., Cheng, A. C., Peacock, S. J. & Prescott, H. C. Pathophysiology, transmission, diagnosis, and treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. JAMA 324, 782–793 (2020).

Chen, P. L. et al. Non-typhoidal Salmonella bacteraemia in elderly patients: an increased risk for endovascular infections, osteomyelitis and mortality. Epidemiol. Infect. 140, 2037–2044 (2012).

Nichol, K. L., Nordin, J. D., Nelson, D. B., Mullooly, J. P. & Hak, E. Effectiveness of influenza vaccine in the community-dwelling elderly. N. Engl. J. Med. 357, 1373–1381 (2007).

Targonski, P. V., Jacobson, R. M. & Poland, G. A. Immunosenescence: role and measurement in influenza vaccine response among the elderly. Vaccine 25, 3066–3069 (2007).

Carrette, F. & Surh, C. D. IL-7 signaling and CD127 receptor regulation in the control of T cell homeostasis. Semin. Immunol. 24, 209–217 (2012).

den Braber, I. et al. Maintenance of peripheral naive T cells is sustained by thymus output in mice but not humans. Immunity 36, 288–297 (2012).

Qi, Q. et al. Diversity and clonal selection in the human T-cell repertoire. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 13139–13144 (2014).

Li, G. et al. Decline in miR-181a expression with age impairs T cell receptor sensitivity by increasing DUSP6 activity. Nat. Med. 18, 1518–1524 (2012).

Araujo, L., Khim, P., Mkhikian, H., Mortales, C. L. & Demetriou, M. Glycolysis and glutaminolysis cooperatively control T cell function by limiting metabolite supply to N-glycosylation. eLife 6, e21330 (2017).

Chen, I. J., Chen, H. L. & Demetriou, M. Lateral compartmentalization of T cell receptor versus CD45 by galectin-N-glycan binding and microfilaments coordinate basal and activation signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 35361–35372 (2007).

Demetriou, M., Granovsky, M., Quaggin, S. & Dennis, J. W. Negative regulation of T-cell activation and autoimmunity by Mgat5 N-glycosylation. Nature 409, 733–739 (2001).

Dennis, J. W., Nabi, I. R. & Demetriou, M. Metabolism, cell surface organization, and disease. Cell 139, 1229–1241 (2009).

Lau, K. S. et al. Complex N-glycan number and degree of branching cooperate to regulate cell proliferation and differentiation. Cell 129, 123–134 (2007).

Mkhikian, H. et al. Genetics and the environment converge to dysregulate N-glycosylation in multiple sclerosis. Nat. Commun. 2, 334 (2011).

Mkhikian, H. et al. Golgi self-correction generates bioequivalent glycans to preserve cellular homeostasis. eLife 5, e14814 (2016).

Mortales, C. L., Lee, S. U. & Demetriou, M. N-Glycan branching is required for development of mature B cells. J. Immunol. 205, 630–636 (2020).

Morgan, R. et al. N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase V (Mgat5)-mediated N-glycosylation negatively regulates Th1 cytokine production by T cells. J. Immunol. 173, 7200–7208 (2004).

Mortales, C. L., Lee, S. U., Manousadjian, A., Hayama, K. L. & Demetriou, M. N-Glycan branching decouples B Cell innate and adaptive immunity to control inflammatory demyelination. iScience 23, 101380 (2020).

Dennis, J. W., Warren, C. E., Granovsky, M. & Demetriou, M. Genetic defects in N-glycosylation and cellular diversity in mammals. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 11, 601–607 (2001).

Sy, M. et al. N-Acetylglucosamine drives myelination by triggering oligodendrocyte precursor cell differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 295, 17413–17424 (2020).

Grigorian, A. & Demetriou, M. Mgat5 deficiency in T cells and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. ISRN Neurol. 2011, 374314 (2011).

Bahaie, N. S. et al. N-Glycans differentially regulate eosinophil and neutrophil recruitment during allergic airway inflammation. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 38231–38241 (2011).

Li, C. F. et al. Hypomorphic MGAT5 polymorphisms promote multiple sclerosis cooperatively with MGAT1 and interleukin-2 and 7 receptor variants. J. Neuroimmunol. 256, 71–76 (2013).

Zhou, R. W. et al. N-glycosylation bidirectionally extends the boundaries of thymocyte positive selection by decoupling Lck from Ca(2)(+) signaling. Nat. Immunol. 15, 1038–1045 (2014).

Lee, S. U. et al. Increasing cell permeability of N-acetylglucosamine via 6-acetylation enhances capacity to suppress T-helper 1 (TH1)/TH17 responses and autoimmunity. PLoS One 14, e0214253 (2019).

Grigorian, A. et al. Control of T Cell-mediated autoimmunity by metabolite flux to N-glycan biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 20027–20035 (2007).

Lee, S. U. et al. N-glycan processing deficiency promotes spontaneous inflammatory demyelination and neurodegeneration. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 33725–33734 (2007).

Park, J. H. et al. Suppression of IL7Ralpha transcription by IL-7 and other prosurvival cytokines: a novel mechanism for maximizing IL-7-dependent T cell survival. Immunity 21, 289–302 (2004).

Becklund, B. R. et al. The aged lymphoid tissue environment fails to support naive T cell homeostasis. Sci. Rep. 6, 30842 (2016).

Martin, C. E. et al. IL-7/anti-IL-7 mAb complexes augment cytokine potency in mice through association with IgG-Fc and by competition with IL-7R. Blood 121, 4484–4492 (2013).

Grabstein, K. H. et al. Inhibition of murine B and T lymphopoiesis in vivo by an anti-interleukin 7 monoclonal antibody. J. Exp. Med. 178, 257–264 (1993).

Martin, C. E. et al. Interleukin-7 availability is maintained by a hematopoietic cytokine sink comprising innate lymphoid cells and T cells. Immunity 47, 171–182 e174 (2017).

Weitzmann, M. N., Roggia, C., Toraldo, G., Weitzmann, L. & Pacifici, R. Increased production of IL-7 uncouples bone formation from bone resorption during estrogen deficiency. J. Clin. Invest. 110, 1643–1650 (2002).

Grigorian, A. et al. N-acetylglucosamine inhibits T-helper 1 (Th1)/T-helper 17 (Th17) responses and treats experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 40133–40141 (2011).

Blaschitz, C. & Raffatellu, M. Th17 cytokines and the gut mucosal barrier. J. Clin. Immunol. 30, 196–203 (2010).

Liu, J. Z., Pezeshki, M. & Raffatellu, M. Th17 cytokines and host-pathogen interactions at the mucosa: dichotomies of help and harm. Cytokine 48, 156–160 (2009).

Parry, C. M. et al. A retrospective study of secondary bacteraemia in hospitalised adults with community acquired non-typhoidal Salmonella gastroenteritis. BMC Infect. Dis. 13, 107 (2013).

Ren, Z. et al. Effect of age on susceptibility to Salmonella Typhimurium infection in C57BL/6 mice. J. Med. Microbiol. 58, 1559–1567 (2009).

Raffatellu, M. et al. Simian immunodeficiency virus-induced mucosal interleukin-17 deficiency promotes Salmonella dissemination from the gut. Nat. Med. 14, 421–428 (2008).

Geddes, K. et al. Identification of an innate T helper type 17 response to intestinal bacterial pathogens. Nat. Med. 17, 837–844 (2011).

Vranjkovic, A., Crawley, A. M., Gee, K., Kumar, A. & Angel, J. B. IL-7 decreases IL-7 receptor alpha (CD127) expression and induces the shedding of CD127 by human CD8+ T cells. Int. Immunol. 19, 1329–1339 (2007).

Sportes, C. et al. Administration of rhIL-7 in humans increases in vivo TCR repertoire diversity by preferential expansion of naive T cell subsets. J. Exp. Med. 205, 1701–1714 (2008).

Kim, H. R., Hong, M. S., Dan, J. M. & Kang, I. Altered IL-7Rα expression with aging and the potential implications of IL-7 therapy on CD8+ T-cell immune responses. Blood 107, 2855–2862 (2006).

Ucar, D. et al. The chromatin accessibility signature of human immune aging stems from CD8(+) T cells. J. Exp. Med. 214, 3123–3144 (2017).

Abdel Rahman, A. M., Ryczko, M., Pawling, J. & Dennis, J. W. Probing the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway in human tumor cells by multitargeted tandem mass spectrometry. ACS Chem. Biol. 8, 2053–2062 (2013).

Brandt, A. U. et al. Association of a marker of N-acetylglucosamine with progressive multiple sclerosis and neurodegeneration. JAMA Neurol. 78, 842–852 (2021).

Passtoors, W. M. et al. IL7R gene expression network associates with human healthy ageing. Immun. Ageing 12, 21 (2015).

Davey, D. A. Androgens in women before and after the menopause and post bilateral oophorectomy: clinical effects and indications for testosterone therapy. Womens Health (Lond.) 8, 437–446 (2012).

Taylor, J. et al. Transcriptomic profiles of aging in naive and memory CD4(+) cells from mice. Immun. Ageing 14, 15 (2017).

Gubbels Bupp, M. R., Potluri, T., Fink, A. L. & Klein, S. L. The confluence of sex hormones and aging on immunity. Front. Immunol. 9, 1269 (2018).

Peckham, H. et al. Male sex identified by global COVID-19 meta-analysis as a risk factor for death and ITU admission. Nat. Commun. 11, 6317 (2020).

Takahashi, T. et al. Sex differences in immune responses that underlie COVID-19 disease outcomes. Nature 588, 315–320 (2020).

Bove, R. M. et al. Effect of gender on late-onset multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. 18, 1472–1479 (2012).

Klein, S. L. & Flanagan, K. L. Sex differences in immune responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 16, 626–638 (2016).

Fink, A. L. & Klein, S. L. Sex and gender impact immune responses to vaccines among the elderly. Physiology (Bethesda) 30, 408–416 (2015).

Goss, P. E., Reid, C. L., Bailey, D. & Dennis, J. W. Phase IB clinical trial of the oligosaccharide processing inhibitor swainsonine in patients with advanced malignancies. Clin. Cancer Res. 3, 1077–1086 (1997).

Grigorian, A. & Demetriou, M. Manipulating cell surface glycoproteins by targeting N-glycan-galectin interactions. Methods Enzymol. 480, 245–266 (2010).

Acknowledgements

We thank C. Kawas (UC Irvine) for access to subjects from the ‘90+ cohort’. Research was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (R01AI108917, M.D.; R01AI144403, M.D.; R01AI126277, M.R.; R01AI114625, M.R.), the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (R01AT007452, M.D.), the Burroughs Wellcome Fund (Investigator in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease Award, M.R.) and a predoctoral fellowship from the American Heart Association (S.K.). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript. Obtaining human blood was supported by a Clinical Translational Science Award to the Institute for Clinical and Translation Science, UC Irvine.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.M. and M.D. conceptualized the study. K.L.H., H.M., S.K., M.R., J.P., J.W.D. and M.D. developed the methodology. K.L.H., H.M., K.K., C.L., R.W.Z., J.P., S.K., P.Q.N.T, K.M.L., A.D.G., J.L.H., D.G., P.L.L., H.S. and B.L.N. performed the investigation. K.L.H, H.M. and M.D. wrote the original draft. H.M. and M.D. reviewed and edited the manuscript. K.L.H, H.M. and M.D. provided visualizations. H.M., M.R., J.W.D. and M.D. supervised the project. M.R. and M.D. acquired funding.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

J.D. and M.D. are named as inventors on a patent application that describes GlcNAc as a biomarker for multiple sclerosis. J.D. and M.D. are named as inventors on a patent for use of GlcNAc in multiple sclerosis. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Aging thanks Jung-Hyun Park and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

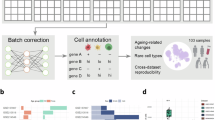

Extended Data Fig. 1 Mouse T cells display a sex-dimorphic increase in N-glycan branching with age.

a) Fructose 6-phosphate may be metabolized by glycolysis or enter the hexosamine pathway to supply UDP-GlcNAc to the Golgi branching enzymes Mgat1, 2, 4 and 5, which generate mono-, bi-, tri-, and tetra-antennary GlcNAc branched glycans, respectively. The branching enzymes utilize UDP-GlcNAc with declining efficiency such that both Mgat4 and Mgat5 are limited for branching by the metabolic production of UDP-GlcNAc. Small molecule inhibitor kifunensine (KIF) can be used to eliminate N-glycan branching. Plant lectin L-PHA (Phaseolus vulgaris, leukoagglutinin) and ConA (concanavalin A) binding sites are also shown. Abbreviations: OT, oligosaccharyltransferases; GI, glucosidase I; GII, glucosidase II; MI, mannosidase I; MII, mannosidase II; Mgat, N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase; GalT3, galactosyltransferase 3; iGnT, i-branching enzyme β1,3-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase; KIF, kifunensine; GlcNAc, N-acetylglucosamine; UDP, uridine diphosphate; Km, Michaelis constant of the enzyme. b) The gating strategy is demonstrated for CD4+ TN cells. Lymphocytes were first gated on singlets, followed by gating on CD3+CD4+CD8−CD25−CD62L+CD44− cells by sequential steps. c, d) Splenocytes from five young and old mice were analyzed for L-PHA (c) or ConA (d) binding by flow cytometry, gating on the indicated CD4+ T cell subsets. Absolute geometric mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) is shown to allow direct comparison between naive and memory subsets. e-i) CD4+ TN cells (e-g) CD19+ B cells (h) or thymocytes (i) were obtained from the lymph node (e), spleen (f-h) or thymus (i) of female (e, g-i) or male (f-h) mice of the indicated ages, and analyzed for L-PHA binding by flow cytometry. Absolute or normalized geometric mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) are shown. Each symbol represents a single mouse. P-values by two-tailed Mann–Whitney (c, d) or two-tailed Wilcoxon (e, h, i). Error bars indicate mean ± s.e.m.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Elevated IL-7 signaling increases N-glycan branching in old female naiveT cells.

a) Representative flow cytometry plots of donor and recipient cells post-adoptive transfer. b) Negatively selected CD4+ T cells were FACS sorted for TN (CD62L+CD44−) and TEM (CD62L−CD44+) populations. Representative flow cytometry plots demonstrating purity of sorted cells used for RNA-seq. c) Principal component analysis (PCA) of RNA-seq data comparing gene expression in CD4+ TN and CD4+ TEM cells from young male (7-8 weeks old), young female (10-11 weeks old), old male (83-86 weeks old) and old female (85 weeks old) mice. Three biological replicates were performed for each group. d) Out of 24062 genes analyzed by RNA-seq, 158 DEGs were identified when comparing young and old CD4+ TN cells in females, 192 DEGs were identified in males, and 44 DEGs were shared. e) Young and old naive CD4+ T cell mRNA expression of N-glycan pathway genes by real-time qPCR. f) Flow cytometric analysis of IL7Rα in ex vivo CD4+ TN cells from young and old male mice. g) L-PHA versus IL7Rα expression in ex vivo CD4+ TN cells from old male and female mice. h, i) Flow cytometric analysis of IL7Rα in ex vivo young and old CD4+ TEM cells from female (h) and male (i) mice. j-l) C57BL/6 mice of the indicated ages were injected intraperitoneally with either isotype control (1.5 mg) or anti-IL-7 antibody (M25, 1.5 mg) three times per week for two (j) or four (k, l) weeks, and analyzed for L-PHA or IL7Rα expression in blood (k) or spleen (j, l). Each symbol represents a single mouse unless specified otherwise. P-values determined by one-tailed Wilcoxon (f), linear regression (g), two-tailed Wilcoxon (h, i), Kruskal–Wallis with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test (j), or one-tailed Mann–Whitney (k, l). Error bars indicate mean ± s.e.m.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Thymectomy and ovariectomy are insufficient to drive increases in N-glycan branching.

a-i) Female mice underwent thymectomy (a-c), ovariectomy (d-g), both surgeries (h, i), or corresponding sham procedures at the age of 9 weeks. Flow cytometry on blood at the indicated timepoints post-procedure was performed to detect percentage of CD4+ TN cells (a), IL7Rα expression (b, d, g, h), or L-PHA binding (c, e, f, i), gating on CD4+ TN cells. Absolute or normalized geometric mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) are shown. Each symbol at a particular timepoint represents a single mouse. P-values determined by one-tailed Mann–Whitney (b, d, g, h). Error bars indicate mean ± s.e.m.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Age-dependent increases in N-glycan branching suppress proinflammatory T cell function.

a) L-PHA binding of splenocytes from Mgat2fl/fl and Mgat2fl/fllck-cre female mice, gated on CD4+ TN cells. b) Splenocytes from an old mouse were treated with or without kifunensine for 24 hours, then analyzed for L-PHA binding by flow cytometry, gating on CD4+ TN cells. c) Splenocytes from female mice of the indicated ages and genotypes were activated with plate-bound anti-CD3 for 15 minutes. Following fixation and permeabilization, phospho-ERK1/2 induction was analyzed in CD4+ TN cells by flow cytometry, gating additionally on L-PHA negative cells in Mgat2fl/fl/lck-cre mice. d, e) Flow cytometric analysis of purified mouse splenic CD4+ T cells activated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 for 4 days with TH17 (TGFβ + IL-6+IL-23) or iTreg (TGFβ) inducing conditions, gating additionally on L-PHA negative cells in Mgat2fl/fl/lck-cre mice. f) Female Mgat2fl/fl and Mgat2fl/fllck-cre mice were inoculated with streptomycin (0.1 ml of a 200 mg/ml solution in sterile water) intragastrically one day prior to inoculation with S. Typhimurium (5×108 colony forming units, CFU per mouse) by oral gavage. CFU in the cecal content was determined 72 hours after infection. Data shown are representative of two (c), or at least three (a, b, d, e) independent experiments. P-values by one-tailed Mann–Whitney (f). Error bars indicate mean ± s.e.m (c, d, e) or geometric mean (f).

Extended Data Fig. 5 Age-dependent increases in N-glycan branching suppress T cell activity in human females.

a-d) Human PBMCs from healthy females (a, c) or males (b, d) as indicated were analyzed for L-PHA binding by flow cytometry gating on CD8+ T cells (a, b) or CD19+ B cells (c, d). e, f) CD4+ TN cells (CD45RA+CD45RO−) from healthy females (e) and males (f) under the age of 65 were analyzed for L-PHA binding by flow cytometry. g) Human PBMCs from young (22-38 years old) and old (90-94 years old) female subjects were analyzed for L-PHA binding on CD4+ TN cells (CD45RA+CD45RO−) before or after 96 hours of culture in complete media. Shown is the ratio or each old subject over the average of the young at the two timepoints. Each symbol represents a single individual. R2 and p-values by linear regression (a-f) or by paired one-tailed t test, following passage of Shapiro–Wilk normality test (g). Error bars indicate mean ± s.e.m.

Extended Data Fig. 6 N-acetylglucosamine and IL-7 synergize to raise N-glycan branching in human T cells.

a, b) PBMCs from nine healthy female donors (28-45 years old) were cultured with or without rhIL-7 (50 ng/ml) and/or GlcNAc (10 mM or 40 mM) for 9 days, then analyzed for L-PHA binding by flow cytometry, gating on CD4+ TEM (CD45RA−CD45RO+CCR7−) cells (a) or CD8+ TEM (CD45RA−CD45RO+CCR7−) cells (b). c) Mouse plasma from female mice of the indicated ages was analyzed for HexNAc levels by LC-MS/MS. d, e) Flow cytometric analysis of human PBMCs stimulated by anti-CD3 in the presence or absence of kifunensine as indicated for 24 hours to analyze for activation marker CD69 (d) or 72 hours to assess proliferation by CFSE dilution (e), gating on CD4+ T cells. f) Female human PBMCs were treated in vitro with kifunensine for 24 hours, followed by analysis of L-PHA binding on CD4+ TN cells by flow cytometry. Data shown is representative of three independent experiments with different donors. g) Female human PBMCs were treated in vitro with kifunensine for up to four days, followed by analysis of L-PHA binding on CD4+ TN cells by flow cytometry. P-values by Kruskal–Wallis with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test (a, b), two-tailed Mann–Whitney (c), and one-tailed Mann–Whitney (d, e). Error bars indicate mean ± s.e.m.

Supplementary information

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Statistical Source Data.

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical Source Data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Statistical Source Data.

Source Data Fig. 4

Statistical Source Data.

Source Data Fig. 5

Statistical Source Data.

Source Data Fig. 6

Statistical Source Data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Statistical Source Data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Statistical Source Data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Statistical Source Data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Statistical Source Data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Statistical Source Data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 6

Statistical Source Data.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mkhikian, H., Hayama, K.L., Khachikyan, K. et al. Age-associated impairment of T cell immunity is linked to sex-dimorphic elevation of N-glycan branching. Nat Aging 2, 231–242 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43587-022-00187-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43587-022-00187-y

This article is cited by

-

SIRT3-SUMO regulated Treg cell differentiation and asthma development by mediating N-glycosylation through the FAO pathway

Cell Biology and Toxicology (2025)

-

Membrane organization by tetraspanins and galectins shapes lymphocyte function

Nature Reviews Immunology (2024)

-

N-acetylglucosamine inhibits inflammation and neurodegeneration markers in multiple sclerosis: a mechanistic trial

Journal of Neuroinflammation (2023)