Abstract

Background

In the era of personalized cancer treatment, understanding the intrinsic heterogeneity of tumors is crucial. Despite some patients responding favorably to a particular treatment, others may not benefit, leading to the varied efficacy observed in standard therapies. This study focuses on the prediction of tumor response to chemo-immunotherapy, exploring the potential of tumor mechanics and medical imaging as predictive biomarkers. We have extensively studied “desmoplastic” tumors, characterized by a dense and very stiff stroma, which presents a substantial challenge for treatment. The increased stiffness of such tumors can be restored through pharmacological intervention with mechanotherapeutics.

Methods

We developed a deep learning methodology based on shear wave elastography (SWE) images, which involved a convolutional neural network (CNN) model enhanced with attention modules. The model was developed and evaluated as a predictive biomarker in the setting of detecting responsive, stable, and non-responsive tumors to chemotherapy, immunotherapy, or the combination, following mechanotherapeutics administration. A dataset of 1365 SWE images was obtained from 630 tumors from our previous experiments and used to train and successfully evaluate our methodology. SWE in combination with deep learning models, has demonstrated promising results in disease diagnosis and tumor classification but their potential for predicting tumor response prior to therapy is not yet fully realized.

Results

We present strong evidence that integrating SWE-derived biomarkers with automatic tumor segmentation algorithms enables accurate tumor detection and prediction of therapeutic outcomes.

Conclusions

This approach can enhance personalized cancer treatment by providing non-invasive, reliable predictions of therapeutic outcomes.

Plain language summary

In personalized cancer treatment, it is important to understand that not all tumors respond the same way to therapy. While some patients may benefit from a particular treatment, others may not, leading to different outcomes. This study focuses on predicting how tumors will respond to a combination of chemotherapy and immunotherapy. Specifically, we looked at difficult-to-treat tumors with very stiff structures. These tumors can be softened with certain drugs making them more responsive to treatment. We developed a computer method to analyze medical images that measure the stiffness of tumors. Our method was trained on a large set of tumor images and was able to predict how well a tumor would respond to treatment. Overall, this approach could improve personalized cancer treatment using non-invasive medical imaging to predict which therapies will be most effective for each patient.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the fight against cancer, it is well recognized that tumors are highly heterogeneous and they might differ considerably not only between tumors of different types, but also among tumors of the same type or even the same tumor during progression. As a result, the efficacy of standard cancer therapies varies, and while some patients respond to a particular treatment, other patients do not gain any benefit. Consequently, crucial to cancer therapy is the prediction of a patient’s response to treatment1. Failure of standard therapies has led to the introduction of a new era of personalized, patient-specific treatments. The basis of these treatments is the identification of one or more biomarkers that characterize the state of a particular tumor. Emerging technologies have been used towards the development of new biomarkers analyzing mainly the human genome, but only a few of them have been approved for cancer prediction1.

Apart from genomic analysis, specific aspects of tumor mechanics could be used as potential predictive biomarkers. It has been well documented that specific types of stiff, “desmoplastic” tumors with a dense stroma (i.e., dense extracellular matrix and non-cancerous cells) are hard to treat and that making them softer through pharmacological interventions results in improved response to therapy2,3,4,5. Specifically, desmoplastic tumors, such as subsets of breast and pancreatic cancers and sarcomas, experience tissue stiffening as they grow within a host of normal tissue. This is caused by the activation of fibroblasts that overproduce extracellular matrix components, mainly collagen and hyaluronan6,7. Tumor stiffening induces compression of intratumor blood vessels compromising vessel function, i.e., impaired blood flow/perfusion and oxygen delivery8,9. In turn, hypo-perfusion reduces drug delivery to the tumor and hypoxia induces immuno-suppression, compromising cancer therapy10,11. To restore these abnormalities, a strategy to alleviate tumor stiffness by reprogramming activated fibroblasts to express normal levels of extracellular matrix prior to therapy has been tested in preclinical studies in our lab and with co-workers2,3,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18. This strategy has already been successful in clinical trials19 and new trials are on schedule (clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT03563248, EudraCT Number: 2022-002311-39), establishing a new class of drugs that aim to modulate tumor mechanics, known as mechanotherapeutics20.

Tumor stiffness can be monitored non-invasively with ultrasound shear wave elastography (SWE), which is being used for diagnosis and pathology assessment across different disease settings21,22,23,24. In oncology, SWE has demonstrated promising results in the context of unraveling associations between tumor stiffness and hypoxia, improving the diagnostic accuracy of rectal tumor staging25, enhancing radiologic assessment of breast tumors against standard B-mode anatomical imaging26 and differentiating between malignant and benign thyroid nodules27. Using relatively small cohorts, previous studies have demonstrated that SWE can also be important for potentially predicting response to treatment28,29,30. For example, Evans et al. reported that SWE-estimated interim changes (from baseline) in stiffness of breast tumors, were strongly associated with pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy28. Gu et al. demonstrated that SWE measurements in the mid-course of neoadjuvant chemotherapy were able to predict treatment response29. There are also recent studies that have demonstrated the utility of deep learning for SWE data analysis31,32,33,34,35. These studies have mainly focused on classifying malignant from benign lesions either by fine-tuning pre-trained models (initially trained in the ImageNet data, a large public natural image database)31,36, or through the development of convolutional neural networks (CNN) models that were trained from the beginning32,33,34. Recent evidence on medical image analysis, has demonstrated that hybridization of CNN models with attention mechanisms can improve the diagnostic performance of pure CNNs across various clinical applications and medical imaging modalities37. However, CNN-Attention models have not been examined in the setting of predicting tumor response to therapy from SWE data and, there is no previous study that investigates the ability of SWE in predicting tumor response to chemo-immunotherapy. The focus of this study is to explore the predictive power of SWE imaging combined with CNN-Attention models in determining the outcome of chemo-immunotherapy with or without mechanotherapeutics in murine tumor models.

Recent studies have demonstrated the benefits of combining CNN architectures with attention mechanisms in medical image analysis37. Although CNN models can efficiently learn local pixel interactions and have achieved performance gains over the last years, they have limited capabilities in modeling long-range pixel interactions37. In contrast, the attention mechanism is designed to learn long-range interactions within data. Briefly, the attention mechanism captures long-range pixel interactions by allowing the model to selectively focus on learning relationships between spatially distant regions within imaging data37,38. To learn complementary local-long range pixel interactions, there is an increasing trend to co-pollinate CNN models with attention modules which has led to performance improvements against pure CNN counterparts across various medical image analysis tasks, including classification37,38.

To this end, we employed SWE images of various murine tumor models, including breast cancer (4T1 and E0771), fibrosarcoma (MCA205), osteosarcoma (K7M2), and melanoma (B16F10) treated with chemo-immunotherapy5,16,18,39,40. We integrated a deep learning approach, consisting of a convolutional neural network enhanced with attention modules. This model, trained on a dataset of 1365 SWE images that were taken prior to treatment, was able to predict whether tumors were likely to respond, remain stable, or resist therapy.

Our findings indicate that SWE images can forecast the efficacy of chemotherapy, immunotherapy, or their combination. Given the established clinical use of SWE in oncology and other fields, our research holds promising implications for personalized therapeutic strategies in cancer treatment. Remarkably, these predictive capabilities hold true even when data from all tumor models are analyzed collectively.

Methods

Cell culture and tumor models

The in vivo experiments have already been successfully conducted and subsequently published5,16,18,39,40. Our research team, in collaboration with other colleagues from our laboratory, meticulously cultivated a diverse range of cancer cell lines under carefully tailored culturing conditions. The breast adenocarcinoma cell lines 4T1 and E0771 were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium supplemented with fetal bovine serum and antibiotics. The melanoma cell line B16F10 was maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium with similar supplements. The fibrosarcoma cell line K7M2 and MCA205 was grown in an expansion medium containing RPMI-1640, L-glutamine, sodium pyruvate, FBS, non-essential amino acids, antibiotics, and β-mercaptoethanol. All cell lines were incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 environment. The specific culturing conditions tailored to each cell line were determined based on previous research5,16,18,39,40.

We established syngeneic orthotopic models of murine mammary tumors by implanting specific numbers of 4T1 or E0771 cancer cells into the mammary fat pad of female mice. Similarly, osteosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, and melanoma models were generated by implanting K7M2, MCA205, and B16F10 cells, respectively, into the flanks of male or female mice. The cell count for implantation was determined from prior research5,16,18,39,40. All animal experiments adhered to the animal welfare regulations and guidelines of the Republic of Cyprus and the European Union.

Treatment protocol

All mice were treated with a mechanotherapeutic agent (200 mg/kg tranilast, 500 mg/kg pirfenidone) and chemo-immunotherapy, anti-mouse PD-L1 antibody (B7-H1, Bio X Cell, 10 mg/kg) was administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) and Doxil (3 mg/kg) intravascularly (i.v.)5,16,18,39,40. Upon reaching an average tumor volume of 150 mm3, we initiated treatment with mechanotherapeutic. When tumors averaged 350 mm3 in size, we introduced chemotherapy, immunotherapy, or a combination of these, every three days for three doses for immunotherapy and daily for chemotherapy. Tumor dimensions were regularly monitored, and tumor volume was calculated using a digital caliper. The elastography images were taken when tumors in all groups were approximately 350 mm³ in size, and before the initiation of chemo-immunotherapy. The end of treatment is defined as the day following the administration of the third dose of immunotherapy, or seven days after the initiation of chemotherapy. Supplementary Fig. 1 shows the representative SWE images before and after mechanotherapeutic treatment.

Ultrasound imaging

The images were taken using ultrasound shear wave elastography (SWE) on a Philips EPIQ Elite Ultrasound system with a linear array transducer (eL18-4). The transducer measures the velocity of 2D shear waves as they propagate through tissue perpendicular to the original acoustic impulse, creating a color-mapped elastogram (in kPa) superimposed on a B-mode standard anatomical ultrasound image. The color spectrum, ranging from blue (soft tissue) to red (hard tissue), provides insights into tissue stiffness. A confidence display was also employed to verify the shear wave quality within the user-defined region of interest (ROI). To address the issue of shear wave reflections at tumor boundaries, a thick gel (~1.5 cm thickness) was applied over the tumor surface to create a more uniform medium and thus, minimize the impact of wave reflections and boundary effects.

To ensure the accuracy and reliability of the SWE measurements, several critical technical parameters and practices were followed during imaging: Careful control of the transducer’s pressure and its precise positioning relative to the tumor ensured optimal wave generation and propagation, minimizing artifacts that could potentially affect the measurement’s accuracy. The Philips EPIQ Elite system’s processing algorithms were utilized to calculate the velocity of shear waves in real-time, providing immediate feedback on tissue stiffness. The focused beam radiation pressure shear wave source was positioned at the middle of the tumor. The settings that were used were: frequency 10 MHz, power 52%, B-mode gain 22 dB, dynamic range 62 dB.

Pre-processing

SWE images from murine tumors were used for training and testing all models in terms of predicting treatment response. SWE and B-mode ultrasound images were used to develop a model for automatic segmentations of the tumor area (Auto-Prognose-CNNattention model (SegforClass), see next section). SWE images were overlaid on B-mode images, hence the two datasets were geometrically registered. To train and evaluate the automatic segmentation model, we used an additional 579 SWE and B-mode images from mice that did not undergo chemo-immunotherapy. These images were selected from all five tumor types considered in our analysis, ensuring a comprehensive representation. Importantly, the imaging for these tumors was conducted simultaneously with the treated tumors, when the tumor volume was approximately 350 mm³. These images were used as an augmented dataset (a total number of 1944 images were employed for the development of this model). The tumor area was manually annotated in each of these images to create a mask for training and evaluating the model.

To develop the SegforClass method, we initially devised and trained a key-point detection algorithm to crop the elastography and B-mode data. The resulting images served as inputs for the U-Net model component of the SegforClass combined method.

For all models, we employed data augmentation methods, thereby artificially increasing the size of the training dataset41. Our augmentation techniques included horizontal and vertical flips, random rotations, brightness adjustments, as well as combining all these together. Specifically, for the U-Net component of the (Auto-Prognose-CNNattention) segmentation model, we augmented the data in the training set by applying horizontal and vertical flips. We employed horizontal and vertical flips only for data augmentation in order to improve the robustness and performance of the model by introducing variations to the training dataset to help in the generalization of the model to unseen data. The images that were flipped either vertically or horizontally were considered along with the original images to artificially increase the training dataset. This helps the model to learn from a bigger dataset (i.e., a wider range of B-mode images), which reduces overfitting and increases generalization. Changes in the brightness on a subset of the images in the training dataset were also used to all classification models. This was applied to images that had B-mode and SWE maps overlapped. These brightness adjustments were used not only for the B-mode underneath the elastography but to the whole elastography image. We introduced random crops and zoom operations, with a zoom range of 0.2, to simulate variations in the field of view and image scaling. A set of images underwent random rotations within a 60-degree range, introducing rotational variability to mimic different orientations of the anatomy during imaging procedures. A combination of these augmentations (excluding vertical flips but including horizontal flips, shear, and zoom) was also applied to a specified subset. We did not adjust or change the settings of the ultrasound system for the elastography.

The training set was designated for the initial training of various models, while the validation set was used to adjust the models’ hyper-parameters and select the optimal model based on cross-validation performance. Finally, the testing set was applied to assess the selected model’s efficacy on data that it had not previously encountered. The allocation of images to these sets was done randomly, with a distribution of 70% allocated to the training set, and 15% to each of the validation and testing sets.

Deep learning models

For tumor (response, stable and non-response) classification, we employed three different approaches assessed as prognostic models. Responsive, stable and non-responsive tumors were defined by their relative tumor volume change, employed the RECIST (i.e., Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors) criterion42, occurred between the time of the chemo-immunotherapy administration and the end of the treatment (Fig. 1a): Responsive (relative tumor volume change <1.2), stable (1.2 <relative tumor volume change <2), and non-responsive (relative tumor volume change >2). Firstly, we developed and trained various architectures from the beginning, by devising numerous convolutional neural networks (CNNs) designs followed by fully connected layers prior to classification. Our best-performing model (named as “Prognose-CNNattention”), comprises convolutional layers, followed by interleaved max-pooling and fully connected layers. To further optimize classification performance by modeling both local-global pixel relationships from the input data, we further enhanced the CNN model by adding two sequential trainable soft-attention mechanisms which are integrated as part of the model training. These mechanisms enable the network to focus on the most important regions of the input images. Following experimentation, we empirically engineered the attention modules to the output of the second and third convolutional blocks Fig. 2.

a Schematic of the experimental protocol and the time of shear wave elastography (SWE) measurements. Analysis of SWE images based on b the therapy applied and c the cancer cell lines, along with the corresponding distribution of images among the three classes: response, stable, and non-response. The dataset comprises a total of 1365 images. The specific cancer cell lines included are the murine mammary adenocarcinomas (breast tumors) 4T1 and E0771, the fibrosarcoma MCA205, the osteosarcoma K7M2, and the melanoma B16F10. d Representative SWE images accompanied by B -mode images, with dashed lines indicating the tumor region of interest (ROI). The images were taken prior to initiation of chemo-immunotherapy when tumors in all groups were approximately 350 mm³ in volume and they were used to predict tumor response to therapy.

The prediction G of the last layer of the network is combined with the L1 and L2 estimators in the second and third layers, respectively. Attention weights a1 and a2 are created by applying a softmax function to the compatibility scores c1 and c2. Attention mechanism outputs G1 and G2 are finally concatenated to create the final prediction of the model.

The Prognose-CNNattention model accepts SWE images as inputs and the manually drawn tumor region of interest (ROI, as model input) in 64x64x3 dimensions, and produces a prediction probability for each of the three classes. To prevent overfitting on the training set, we integrated dropout layers as shown in Fig. 2 and early stopping of the training process if performance was not improving after 100 epochs, by retrieving the best weights up to that stage. We used sparce categorical cross-entropy loss function and grid search for hyperparameter tuning. Following experimentation, we found that the optimal batch size was 32 and that using Stochastic Gradient Descent optimizer leads to lower validation loss and faster convergence, as compared to Adam optimizers. The optimal learning rate was 0.0035, but we used cosine decay learning rate, an adaptive learning rate scheduling technique, to improve convergence and generalization. Through this process, learning rate is gradually reduced over epochs in a cosine manner.

Subsequently, we developed a U-Net-based43 architecture to automate tumor segmentations and feed them later into the Prognose-CNNattention model. The U-net architecture comprises an encoder that performs downsampling by reducing the spatial dimensions and increasing the depth of the image to capture its concepts, and a decoder that does upsampling by restoring the spatial dimensions, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. Unlike the original U-Net architecture, we used fewer convolutional layers to prevent overfitting. We examined two models for tumor segmentation in this study. The first model uses SWE images with RGB channels in (64 x 64 x 3) as input, and the second model uses grayscale (64 x 64 x 1) B-mode images. Previous studies33 have demonstrated that using the B-mode for tumor segmentation can perform better, because the tumor boundaries are well defined from the B-mode anatomical images against the color SWE images. The batch size for the training and validation sets is 32. The output of the models is a segmentation map that assigns each pixel of the input image to either the tumor area or the background. Following hyperparameter tuning, we found that the Adam optimizer with a starting learning rate of 0.001 was optimum for training our model. We also applied the same cosine decay learning rate strategy as described for the Prognose-CNNattention model.

The U-Net-based tumor ROI segmentations were fed into the Prognose-CNNattention model to perform predictions of responsive, stable, and non-responsive tumors to anti-neoplastic therapies, offering a fully automated procedure. This combined framework was named “Auto-Prognose-CNNattention”. The main difference between Prognose-CNNattention and SegforClass is that the former performs classification using manually drawn tumor ROIs, whilst the latter produces automatic tumor segmentations prior to classification (executed again through the Prognose-CNNattention model).

Finally, Xception44, VGG16, Inception-v345 and ResNet5046 pre-trained models were used, fine-tuned, and assessed for their prognostic ability to detect responsive, stable, and non-responsive tumors. To train the models, we adopted the pre-trained weights of each architecture derived from their original training on the “ImageNet”, as initial weights. Following this, we appended our classifier at the end of each architecture and proceeded with fine-tuning our model by performing further training using our data. During fine-tuning, all model layers weights were kept unfrozen to allow the model to learn in-SWE-domain data distributions.

The employment of Xception, VGG16, Inception-v3, and ResNet50 pre-trained models, initially trained on the extensive ImageNet dataset, introduces a foundation of generalized visual recognition capabilities to our study. However, the intrinsic difference between the general imagery of ImageNet and the specialized nature of shear wave elastography (SWE) and B-mode ultrasound images necessitates a meticulous fine-tuning process. This process allows these models to adapt from their broad initial training to the nuanced requirements of medical imaging, specifically the identification and classification of tumor responses in SWE images. The fine-tuning involved adjusting the models to recognize patterns and features pertinent to ultrasound images, a task divergent from the models’ original training. It is crucial to acknowledge that while these pre-trained models bring a wealth of pre-learned features, the transition to medical imaging data introduces complexities due to the unique characteristics of ultrasound images, such as texture, contrast, and noise patterns, which differ markedly from the natural images in ImageNet. This adaptation phase is pivotal for leveraging the models’ deep learning capabilities within a medical context, aiming to enhance their prognostic ability for precise tumor response classification. The decision to keep all model layers weights unfrozen during fine-tuning was strategic, ensuring the models’ comprehensive adaptation to the specificities of SWE-domain data, thereby mitigating the potential for performance discrepancies attributed to the models’ origins in non-medical image recognition.

We trained all models on A100 and V100 NVIDIA GPUs with 40GB and 16GB respectively. We used TensorFlow and Keras for the implementation and training of the models and Python programming language for statistical analysis and evaluation. The training process of the deep learning models is illustrated in Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4.

Bootstrapping for confidence interval computations

In our statistical analysis, we employed bootstrapping, a powerful resampling technique, to compute confidence intervals for various metrics derived from our dataset. Bootstrapping involves repeatedly sampling, with replacement, from the observed dataset to generate a large number of simulated samples, known as bootstrap samples. For each bootstrap sample, we calculated the statistic of interest. This process was iterated thousands of times, leading to a distribution of the computed statistics from which confidence intervals were derived. Specifically, we created 100 subsamples from the original training set. Out of these 100 predictions, we computed the mean value of each observation and established 95% confidence intervals.

Models interpretation

Before the trainable soft-attention mechanism was added to the CNN model in this study, the Grad-CAM technique47 was used to get a heatmap visualization that highlights the regions of the images that the model considered important for the classification prediction. After the addition of the soft-attention mechanism, attention heatmaps of the estimators were subsequently generated to visualize these crucial regions. Both the Grad-CAM technique applied to the Prognose-CNN model and the attention maps applied to the Prognose-CNNattention model for visualization purposes are post-hoc techniques, meaning that are applied after the models have been trained. While the post-hoc techniques for visualization are applied after the models have been trained, the trainable soft-attention mechanisms are trained during the training process of the model.

Assessment of intra- and inter-user variability

To ensure the robustness and reliability of our findings, we conducted a thorough evaluation of both intra- and inter-user variability. This was crucial for validating the consistency and reproducibility of tumor segmentation and classification performed both manually by experts and automatically by our models. Intra-user variability was assessed by having the same expert perform tumor segmentation and classification on a randomly selected subset of images at two different time points, separated by a two-week interval. Inter-user variability was evaluated by comparing the tumor segmentation and classification performed by different experts on the same set of images. Specifically, segmentations by two laboratory experts in human performance, and an expert radiation oncologist were compared. This comparison enabled us to understand the variability in segmentation approaches and interpretations between different experts with varying levels of experience and expertise. The findings from these variability assessments were used to inform the training and evaluation of our deep learning models. Understanding the extent of variability helped in fine-tuning the models to account for differences in expert interpretations, ultimately aiming to develop a model that performs consistently across a range of segmentation scenarios.

Statistical analysis

All machine learning models were evaluated for their ability to detect responsive, stable, and non-responsive tumors by calculating the area under the receiver-operating-characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC). We report the specificity, sensitivity, PPV, NPV and ROC, AUC (Tables 1 and 2). Given the balanced nature of our dataset, we used the macro-average over the micro-average, treating all classes with equal importance. The Dice score was used to evaluate the segmentation performance of the SegforClass model.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

Development and Evaluation of the Prognose-CNNattention Model for Predicting Tumor Response to Chemo-Immunotherapy

We developed a deep learning methodology based on SWE images, which involved a CNN model enhanced with attention modules, named as Prognose-CNNattention model. The Prognose-CNNattention model was developed and evaluated as a prognostic model in the setting of detecting responsive, stable, and non-responsive tumors to chemotherapy, immunotherapy, or the combination, following mechanotherapeutics administration. A dataset of 1365 SWE images was obtained from 630 tumors/mice (2-3 SWE images per tumor) as derived from our previous experiments5,16,18,39,40 (Fig. 1b–d) and used to train and evaluate all our deep learning models. In the experiments, mechanotherapeutic treatment – that does not have any anti-tumor effects – was initiated when tumors reached a size of 100-150mm3 and administered daily throughout the experimental protocol. The chemo-immunotherapy was initiated 3-7 days after the start of mechanotherapeutics. Responsive, stable and non-responsive tumors were defined by their relative tumor volume change, employed the RECIST (i.e., Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors) criterion42, occurred between the time of the chemo-immunotherapy administration and the end of the treatment (Fig. 1a): Responsive (relative tumor volume change <1.2), stable (1.2 <relative tumor volume change <2), and non-responsive (relative tumor volume change >2). The dataset includes 502 images from tumors that responded to therapy, 421 from tumors that stayed stable, and 442 from non-responsive tumors. In our analysis, we considered images from different tumor types together in order to increase the sample size for training, validation, and testing but also in order to showcase that biomarkers derived from tumor stiffness can be applied successfully independently from the tumor type. Also, our analysis focused on the effect of stiffness on tumor response and other parameters, including the sex of the mice was beyond its scope.

Before the development of the models, images were split into training, validation, and testing sets. The training set was used to train all different models. The validation set was used to fine-tune all models’ hyper-parameters and evaluate which was the best-performing model through cross-validation assessments. The testing set was used to evaluate the performance of the best-performing (final) model from the previous step on unseen data. The training, validation, and testing sets were determined randomly and consisted of 70%, 15%, and 15% of the images, respectively.

Furthermore, to access the predictive accuracy of our Prognose-CNNattention model, we compared it with predictions from four widely explored pre-trained (on the large ImageNet dataset) classification models, namely Xception, VGG16, Inception-v3 and ResNet50, which were fine-tuned and evaluated as baseline models. Also, apart from the development of the prediction model, we were also interested in automating the tumor segmentation process from the B-mode images. Thus, we developed a U-Net-based classification model to automate tumor area segmentations prior to classification. We named the combined U-Net and Prognose-CNNattention framework as Auto-Prognose-CNNattention (SegforClass) and reassessed the performance of our predictive scheme.

Diagnostic performance of the prognose-CNNattention mode

The Prognose-CNNattention model architecture is shown in Fig. 2. This model leverages a sophisticated classification framework that integrates multiple layers of processing and attention mechanisms to achieve its remarkable diagnostic performance. One of the distinctive features of the Prognose-CNNattention model is the incorporation of attention mechanisms, which markedly contribute to its high performance. Attention weights, represented as ‘a1’ and ‘a2’, are created by applying a softmax function to compatibility scores ‘c1’ and ‘c2’. These compatibility scores capture the relevance and importance of various elements in the input data, allowing the model to focus on the most informative aspects. The Prognose-CNNattention model architecture demonstrated the highest diagnostic performance in predicting responsive, stable, and non-responsive tumors, against all other models (Prognose-CNNattention, Prognose-CNN (without Attention), Auto-Prognose-CNNattention, Xception, VGG16, Inception-V3, ResNet50) evaluated in this study (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1).

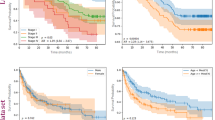

Table 1 and Fig. 3a present the receiver operating characteristic curves (ROC)- derived results of the Prognose-CNNattention model. The Prognose-CNNattention model achieved an accuracy of 0.87 on the test set and an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.96. Figure 3b shows the ROC curves of the three classes for the evaluation of the same model at all thresholds. Additionally, to assess the robustness and reliability of our findings, we conducted a comprehensive evaluation of both intra- and inter-user variability in tumor segmentation and classification. This evaluation involved two laboratory experts in human performance, who classified the images into three categories based on their expertise, at two distinct time points separated by a two-week interval to assess intra-user variability. This process ensured the validation of the consistency and reproducibility of manual classifications against the automated model predictions. The classification performance of laboratory experts (Expert 1 and 2), presented as twins cross/star respectively across two sessions in Fig. 3a, b, reflects not only their diagnostic accuracy but also the consistency of their classifications over time and across different evaluators. The confusion matrix of the Prognose-CNNattention model is presented in Fig. 3c, which demonstrates that specimens responsive to therapy were not predicted as non-responsive by the model, and vice versa. The Prognose-CNNattention-derived model outcomes for all 3 classes are detailed in Table 2. By employing 100 bootstrap resamples for each metric of interest, we were able to derive confidence intervals that accurately reflect the variability and uncertainty inherent in our complex dataset (Table 1). The results of this method revealed that the confidence intervals obtained through bootstrapping were tighter and more reliable. Based on the curve comparison, it was determined that the difference between the ROC of the Prognose-CNAttention model and the ROC of the best pre-trained model is statistically significant. This finding indicates that although the Prognose-CNAttention model demonstrated only a marginal improvement, this enhancement was consistent across various ROC thresholds, underlining its significance. Therefore, the Prognose-CNAttention model performs better than the best pre-trained model in a statistically significant manner.

a Macro-average ROC with the one-vs-rest scheme that shows the performance metrics difference between the Prognose-CNNattention model and the pre-trained networks (right) and the performance metrics difference between the Prognose-CNN models with and without attention, and Auto-Prognose-CNNattention framework (SegforClass) (left). b ROC curves of the three classes for the Prognose-CNNattention model. The performance of a laboratory experts is plotted in a, b by twins cross/star respectively across two sessions. c Confusion matrix of the Prognose-CNNattention. d Prognose-CNNattention model performance per treatment group. The ratio of responsive, stable and non-responsive tumors per treatment group in our dataset compared to how the model classified the tumors in each treatment group. P values for the ROC curves between the ROC of the Prognose-CNAttention and the ROC of best pre-trained (Prognose-CNN models without attention, Auto-Prognose-CNNattention, Xception, VGG16, Inception-V3, ResNet500.043, 0.0021, 0.0015, 0.0001, 0.0007. 0.0023 respectively.

Subsequently, we carried out further analysis to evaluate how well the Prognose-CNNattention model performed per treatment procedure. The results are shown in Fig. 3d. This analysis was essential to ensure that the model consistently provides acceptable results and behaves fairly for all treatment groups. Based on the results, we can say that the model performs well for all treatment groups with only a small percentage of misclassified tumors.

Our analysis extends to evaluating the Prognose-CNNattention model’s predictive performance across various tumor types, as detailed in Supplementary Fig. 5. The confusion matrices provided for each tumor type reveal critical insights into the model’s diagnostic accuracy and its capacity to generalize across different cancer categories. Notably, the model demonstrates commendable performance in classifying tumors as responsive, stable, or non-responsive to treatment across all examined tumor types.

Comparative analysis of pre-trained models’ predictive accuracy

Although all pre-trained models examined showed high diagnostic performance, they showed lower accuracy in predicting responsive, stable, and non-responsive tumors from SWE data, against the Prognose-CNNattention, Prognose-CNN and SegforClass models (Table 1, Fig. 3a). Confusion matrices of all pre-trained models during inference in the test set, are shown in Supplementary Fig. 6.

Impact of attention mechanisms on model performance

We further performed an ablation experiment to evaluate the performance of the Prognose-CNNattention without attention (Prognose-CNN). Table 2 shows a detailed comparison between the Prognose- CNNattention and the Prognose-CNN models. By incorporating trainable attention mechanisms in the Prognose-CNNattention model, the model’s accuracy improved by 0.02 against its plain CNN counterpart. Additionally, the Prognose-CNNattention model achieved the highest AUC, sensitivity and PPV in terms of predicting responsive tumors.

Performance of SegforClass model in tumor segmentation and classification

Subsequently, we developed methods for the automatic segmentation of the tumor from the ultrasound B-mode images. We developed two U-Net models, one used SWE images, and the other standard anatomical B-mode images for training and testing. The segmentation model that used B-mode images outperformed the SWE U-Net model. In particular, the model with B-mode images achieved a Dice coefficient score of 0.81 on the test set, whilst the model that used SWE images achieved a score of 0.79. Following this experiment, B-mode images were used in the final SegforClass model. The Auto-Prognose-CNNattention-derived model outcomes for all three classes are shown in Table 2. The diagnostic performance metrics were slightly lower compared to the Prognose-CNNattention model. The segmentation maps of Fig. 4 demonstrate the agreement between the manual and automatic segmentations, by presenting the areas where the model successfully identified the tumor region. Fig. 5 shows examples of the SegforClass model framework. Supplementary Fig. 7 shows the ROC curves of the three classes for the evaluation of the same model at all thresholds, and the confusion matrix of the SegforClass model.

Manual segmentation is annotated by a laboratory expert while automatic segmentation is predicted by the model. Segmentation maps show the regions where the model accurately predicts the tumor area. The model predicts whether each pixel belongs to tumor area or to the background. True positive and true negative represent correct predictions.

The SWE and B-mode parts are first identified in the ultrasound images. B-mode is then used as input for the tumor segmentation model and when the tumor region is segmented, it is transferred to the elastography (SWE) images. The tumor area is finally cropped and used as input for the prognostic prediction model. In the first example of the figure, the model predicted the tumor as stable with the probability of 78% and in the second example the model predicted the tumor as responsive with the probability of 99%.

Validation of SegforClass model through expert manual segmentation

We further evaluated our SegforClass model outcomes by comparing these against manually drawn tumor areas from an additional expert radiation oncologist recruited from the German Oncology Center (GOC, Limassol, Cyprus). The expert radiation oncologist manually segmented the tumor areas in B-mode images in a subset of the test set. The complete dataset was manually annotated by an ultrasound expert from our lab.

To ascertain the robustness and reliability of our tumor segmentation and classification, we extensively assessed both intra- and inter-user variability. This involved: (a) Evaluating intra-user variability by having each expert repeat the segmentation and classification on a selected subset of images across two sessions, separated by a two-week interval. (b) Assessing inter-user variability through comparisons between segmentations and classifications performed by two laboratory experts and an expert radiation oncologist on the same set of images. Using the Dice coefficient score as our metric, we conducted two primary evaluations: (1) comparing manual segmentations among the experts, and (2) comparing the manual segmentation by the expert radiation oncologist with segmentations derived from the SegforClass model (as shown in Supplementary Fig. 8). Both sets of comparisons achieved a Dice score of 0.79–0.81, indicating a high level of agreement. This high Dice score, reflecting consistent and reproducible segmentations between manual annotations by our laboratory and ultrasound experts, and between these manual annotations and the SegforClass model’s output, validates the accurate annotation of the dataset.

The laboratory expert 1 in human performance was responsible for the manual annotation of the tumor areas in the dataset, ensuring the accuracy of the ground truth against which the SegforClass model’s performance was benchmarked. The expert radiation oncologist, specifically recruited from the German Oncology Center (GOC Limassol, Cyprus), manually segmented the tumor areas in B-mode images for a subset of the test set. This manual segmentation by the expert radiation oncologist was then compared to the SegforClass model-derived segmentations. Similarly, the ultrasound expert from 2 the lab manually annotated the complete dataset. The manual segmentations from both the expert radiation oncologist and the ultrasound experts 1 and 2 were then used to evaluate the SegforClass model outcomes.

Discussion

In the realm of medical imaging and diagnostics, the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and deep learning methodologies is rapidly gaining traction. Our study offers compelling preclinical evidence that underscores the potential of deep learning techniques in harnessing the power of SWE for the development of objective and reliable biomarkers. The primary objective of these biomarkers is to predict how tumors will respond to chemo-immunotherapy with or without the use of mechanotherapeutics to sensitize the tumor microenvironment. This prediction capability is crucial as it can differentiate between tumors that are likely to respond to treatment and those that are not. One of the notable findings of our study is the potential of the SWE images, to serve as a mechanical/imaging biomarker. This biomarker can provide insights into the tumor’s probable response even before the initiation of therapy. The automation of this prognosis process, facilitated by AI, is another groundbreaking aspect of our research.

In preclinical studies, the literature reports elastic modulus values for 4T1 breast cancer models within the range of 30–40 kPa48 and for E0771 breast tumors within 40–60 kPa49, positioning them at the highest end of the stiffness spectrum typically observed in murine desmoplastic tumors. For the B16F10 melanoma model, the reported values are approximately 20 kPa48, reflecting the differences in extracellular matrix composition and mechanical properties characteristics of melanomas. In clinical settings, SWE has been mostly applied to breast tumors and it was found to exhibit higher stiffness values than murine tumors, with measurements around 110 kPa49. This notable discrepancy underlines the potential variances in tumor microenvironments and mechanical properties between murine models and human tumors. There is a lack of pertinent SWE data in the literature for the fibrosarcoma and osteosarcoma cell lines employed in our study, except for our previous work that was employed here5,39. The lack of such data underscores a critical area for future investigation, highlighting the necessity for a more comprehensive mechanical characterization, spanning a wider range of tumor types. In our study, the elastic modulus of 4T1 (36.92 ± 5.7 kPa), E0771 (52.36 ± 5.3 kPa), and B16F10 (26.22 ± 5.2 kPa) tumors that were not treated with mechanotherapeutics, closely matched the ranges reported in the literature, affirming the accuracy of our SWE imaging methodology. Notably, a comparison between the elastic modulus values before and after treatment with a mechanotherapeutic agent reveals significant changes (p-values 0.00032, 0.000012, 0000084, respectively): 4T1 (30.21 ± 6.3 kPa), B16F10 (21.04 ± 3.1 kPa), and E0771 (33.03 ± 6.7 kPa).

The integration of AI and medical imaging is not just about enhancing diagnostic accuracy; it is about redefining patient care. With over 2000 ongoing clinical trials, immunotherapy is reshaping the cancer treatment landscape. The development of predictive biomarkers offers a dual advantage: safeguarding patients from potentially harmful therapies and guiding patient-specific treatment optimization. Our study underscores the potential of ultrasound-derived images of stiffness as biomarkers of response to treatment combinations. This paves the way for comprehensive clinical research to identify biomarkers based on ultrasound or magnetic resonance for predicting patient responses to cancer immunotherapy.

Pre-clinical studies utilizing shear wave elastography (SWE) have greatly advanced our understanding of tumor physiology, particularly in distinguishing between benign and malignant neoplasms50,51,52. By quantitatively measuring tissue stiffness, SWE offers a non-invasive biomarker that correlates with the pathological state of tumors. Malignant tumors typically exhibit a denser and more rigid extracellular matrix than benign tumors, a feature that reflects in their higher stiffness values on SWE53,54. This distinction is crucial, as it enables the early differentiation of cancerous growths from non-cancerous ones, facilitating timely and appropriate therapeutic interventions. Further enhancing the utility of SWE, research has also explored its application in monitoring the dynamic changes in tumor stiffness in response to various treatments. AI, especially deep learning, has transformed tumor diagnosis and prediction in medical imaging55,56,57. By analyzing complex imaging data to identify patterns invisible to the human eye, AI enhances diagnostic accuracy, predicts treatment outcomes, and can potentially have a major impact in personalized care.

Our model shows promise in predicting tumor responses, yet transitioning from pre-clinical models to clinical applications involves overcoming considerable challenges. The complexity of clinical diagnosis and treatment necessitates a personalized approach, considering factors beyond tumor size. Recognizing this, we are advancing our research through clinical trials in collaboration with the Bank of Cyprus Oncology Center (Nicosia, Cyprus, EudraCT number: 2022-002311-39) for sarcoma patients and the German Oncology Center (Limassol, Cyprus) for breast tumor patients. These trials aim to validate our model’s applicability in a clinical setting, with early results indicating variability in the elastic modulus across tumor types and sizes. Incorporating SWE imaging into standard diagnostic procedures, we are refining our model to accommodate the diverse characteristics of human tumors, ensuring its relevance and effectiveness in informing treatment decisions. This effort underscores our commitment to bridging the gap between laboratory research and patient care, highlighting the importance of multidisciplinary collaboration in bringing innovative diagnostic tools to the clinic.

For successful clinical translation, several key steps are necessary, including conducting validation studies with human subjects to confirm the efficacy of our model in a clinical environment, integrating our findings into existing diagnostic protocols to enhance the accuracy of tumor characterization, and developing comprehensive guidelines for interpreting shear wave elastography (SWE) imaging results to support clinical decision-making. Furthermore, we consider the implications of tumor misclassification in clinical practice, recognizing that inaccuracies in tumor classification could have considerable consequences on treatment planning and patient outcomes. Misclassified tumors might lead to inappropriate treatment strategies, potentially affecting the efficacy of the treatment and the patient’s quality of life. Therefore, minimizing misclassification rates is crucial to improving treatment outcomes and ensuring that patients receive the most appropriate care based on accurate tumor characterization.

We have developed deep-learning models that can classify tumors into three categories based on their likely response to therapy: responsive, stable, or non-responsive. This classification is derived from the mechanical biomarker obtained from the SWE images. Furthermore, we have also ventured into the development of deep learning models specifically designed for the segmentation of tumor regions from ultrasound medical images. The automation of these processes is a major leap forward as it offers laboratory professionals and clinical researchers a powerful tool. This tool amalgamates the benefits of a mechanical biomarker with the predictive capabilities of deep learning models, thereby streamlining decision-making processes for patient-specific treatment plans. We should note that while the mechanical aspects of the TME, such as tumor stiffness, are crucial, it is imperative to recognize that biological factors also play a pivotal role in tumor growth, progression, and treatment resistance. Therefore, methodologies such as the one presented here could be complementary to biological markers and considered together by oncologists when deciding the optimal treatment plan.

A noteworthy advantage of employing deep learning and convolutional neural networks over traditional shallow machine learning algorithms is the model’s ability to scan the distribution of the elastic modulus across the entire tumor area. This is in contrast to merely considering average values for smaller regions. However, it’s essential to highlight that while large pre-trained deep learning architectures have shown promise in various challenging tasks, their intricate nature can sometimes lead to overfitting during the fine-tuning phase. This overfitting can, in turn, result in a performance that is subpar compared to shallower architectures that are trained from the ground up.

The exploration of SWE for predicting tumor response, in conjunction with the Prognose-CNN model, marks a notable departure from traditional imaging methodologies. Unlike CT or MRI, which assess tumor response based on changes in size, SWE evaluates the mechanical properties of tissues offering a novel biomarker for therapeutic outcomes. This distinction underlines the transformative potential of SWE in oncology, suggesting that it could lead to more nuanced and potentially earlier indicators of treatment efficacy. Integrating SWE images with advanced AI analytics could refine personalization in cancer treatment, highlighting the crucial role of innovative imaging techniques. The distinct focus of SWE necessitates comprehensive studies to establish its clinical utility fully and to integrate its advantages into the standard-of-care, promising to redefine how tumor responses are evaluated and therapies are tailored. To this end, SWE is a relatively simple imaging modality that could be integrated in standard-of-care imaging as part of diagnosis. Therefore, from the very first time a tumor is diagnosed through ultrasound imaging, SWE images can be taken and analyzed to predict tumor response to therapy. Such a prediction could be incorporated along with other information that clinicians consider in order to support them in the decision-making process and optimal treatment protocols. Our model, while promising as a tool for predicting tumor response, must undergo extensive clinical testing and refinement to enable its clinical translation.

It is important to note that while the attention mechanism provides a theoretical advantage in focusing on salient features38, the actual improvement in performance was consistent but relatively moderate, especially when compared to CNN without attention. However, it is known that the performance of deep learning models can be influenced by several factors including the quality and size of the training dataset, the representativeness of the data for the problem at hand, and the optimization of model parameters38.

Our results suggest that while the attention mechanism offers a novel approach, its benefits in the context of predicting tumor response in ultrasound elastography are consistently incremental when compared to all other models developed in our work. This observation underscores the need for careful consideration of model architecture in relation to the specific characteristics of the medical imaging data and the clinical problem being addressed. One of our future endeavors is to transfer the methods and insights of this work to the clinical setting. Although the Prognose-CNNattention outperformed all other models, we will carefully evaluate all model architectures in terms of their ability to classify responsive from stable and non-responsive tumors.

The attention maps estimated at the output of the 2nd and 3rd CNN blocks of the Prognose-CNNattention technique reveal that the model considers complementary information by focusing on areas with high and low stiffness, respectively. Our study’s inclusion of a trainable attention mechanism has led to substantial improvements in prognostic predictions. This emphasizes the potential advantages of incorporating attention mechanisms, particularly when predictions are based on the distribution of a single attribute like stiffness across an input image. In this manner, the Prognose-CNNattention model is capable of learning both local and global representations from the SWE data. Conversely, Grad-CAM maps47 indicate that the Prognose-CNN model (without attention) concentrates on focalized information around the high-stiffness areas. This focus might extend even outside the tumor area, which can at least partly explain its lower diagnostic performance compared to the attention-enabled variant. Interestingly, we observed a performance drop when transitioning to the SegforClass framework. This decrease can be attributed primarily to the segmentation model’s performance, especially in scenarios where the B-mode imaging doesn’t offer a clear visualization of the tumor. The segmentation inaccuracies can cascade into misclassifications by the classification model, particularly when the input Region of Interest (ROI) contains elastography regions not associated with the tumor. Supplementary Fig. 9 provides a visual comparison between the Grad-CAM maps of the Prognose-CNN model and the attention maps of the Prognose-CNNattention model.

While our study has provided valuable insights, it is not without limitations. One such limitation is the application of the prognostic prediction model and the tumor segmentation model to mice specimens instead of human patients. However, the silver lining here is the availability of abundant data for mice, which has expedited the validation process of using the elastic modulus as a mechanical biomarker for prognostic purposes in pre-clinical studies. With the foundation laid, models trained on abundant pre-clinical SWE images can be fine-tuned using transfer learning techniques for limited human data, paving the way for broader applications in the future.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed in this study are available Supplementary Data 1.

Code availability

The underlying source code for this study can be accessed via Zenodo58.

References

Borrebaeck, C. A. Precision diagnostics: moving towards protein biomarker signatures of clinical utility in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 17, 199–204 (2017).

Jain, R. K., Martin, J. D. & Stylianopoulos, T. The role of mechanical forces in tumor growth and therapy. Annu Rev. Biomed. Eng. 16, 321–346 (2014).

Stylianopoulos, T., Munn, L. L. & Jain, R. K. Reengineering the physical microenvironment of tumors to improve drug delivery and efficacy: from mathematical modeling to bench to bedside. Trends cancer 4, 292–319 (2018).

Martin, J. D., Cabral, H., Stylianopoulos, T. & Jain, R. K. Improving cancer immunotherapy using nanomedicines: progress, opportunities and challenges. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 17, 251–266 (2020).

Voutouri, C. et al. Ultrasound stiffness and perfusion markers correlate with tumor volume responses to immunotherapy. Acta Biomater. 167, 121–134 (2023).

Stylianopoulos, T. et al. Causes, consequences, and remedies for growth-induced solid stress in murine and human tumors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 15101–15108 (2012).

Voutouri, C. & Stylianopoulos, T. Accumulation of mechanical forces in tumors is related to hyaluronan content and tissue stiffness. PloS One 13, e0193801 (2018).

Angeli, S. & Stylianopoulos, T. Biphasic modeling of brain tumor biomechanics and response to radiation treatment. J. Biomech. 49, 1524–1531 (2016).

Vavourakis, V. et al. A validated multiscale in-silico model for mechano-sensitive tumour angiogenesis and growth. PLoS Comput. Biol. 13, e1005259 (2017).

Jain, R. K. Antiangiogenesis strategies revisited: from starving tumors to alleviating hypoxia. Cancer Cell 26, 605–622 (2014).

Mpekris, F. et al. Combining microenvironment normalization strategies to improve cancer immunotherapy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 3728–3737 (2020).

Chauhan, V. P. et al. Angiotensin inhibition enhances drug delivery and potentiates chemotherapy by decompressing tumor blood vessels. Nat. Commun. 4, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms.3516 (2013).

Papageorgis, P. et al. Tranilast-induced stress alleviation in solid tumors improves the efficacy of chemo- and nanotherapeutics in a size-independent manner. Sci. Rep. 7, 46140 (2017).

Polydorou, C., Mpekris, F., Papageorgis, P., Voutouri, C. & Stylianopoulos, T. Pirfenidone normalizes the tumor microenvironment to improve chemotherapy. Oncotarget 8, 24506–24517 (2017).

Panagi, M. et al. TGF-β inhibition combined with cytotoxic nanomedicine normalizes triple negative breast cancer microenvironment towards anti-tumor immunity. Theranostics 10, 1910–1922 (2020).

Mpekris, F. et al. Normalizing the microenvironment overcomes vessel compression and resistance to nano-immunotherapy in breast cancer lung metastasis. Adv. Sci. 8, 2001917 (2021).

Voutouri, C. et al. Endothelin inhibition potentiates cancer immunotherapy revealing mechanical biomarkers predictive of response. Adv. Ther. 4, 2000289 (2021).

Panagi, M. et al. Polymeric micelles effectively reprogram the tumor microenvironment to potentiate nano-immunotherapy in mouse breast cancer models. Nat. Commun. 13, 7165 (2022).

Murphy, J. E. et al. Total neoadjuvant therapy with FOLFIRINOX in combination with Losartan followed by chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced pancreatic cancer: A Phase 2 clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 5, 1020–1027 (2019).

Sheridan, C. Pancreatic cancer provides testbed for first mechanotherapeutics. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 829–831 (2019).

Cui, X. W. et al. Ultrasound elastography. Endosc. Ultrasound 11, 252–274 (2022).

Mislati, R. et al. Shear wave elastography can stratify rectal cancer response to short-course radiation therapy. Sci. Rep. 13, 16149 (2023).

Wang, H. et al. Shear wave elastography can differentiate between radiation-responsive and non-responsive pancreatic tumors: an ex vivo study with murine models. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 46, 393–404 (2020).

Wang, H. et al. Elastography can map the local inverse relationship between shear modulus and drug delivery within the pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma microenvironment. Clin. Cancer Res. 25, 2136–2143 (2019).

Chen, L. D. et al. Assessment of rectal tumors with shear-wave elastography before surgery: comparison with endorectal US. Radiology 285, 279–292 (2017).

Berg, W. A. et al. Shear-wave elastography improves the specificity of breast US: the BE1 multinational study of 939 masses. Radiology 262, 435–449 (2012).

Liu, B. J. et al. Quantitative shear wave velocity measurement on acoustic radiation force impulse elastography for differential diagnosis between benign and malignant thyroid nodules: a meta-analysis. Ultrasound Med Biol. 41, 3035–3043 (2015).

Evans, A. et al. Prediction of pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy for primary breast cancer comparing interim ultrasound, shear wave Elastography and MRI. Ultraschall Med. 39, 422–431 (2018).

Gu, J. et al. Early assessment of shear wave elastography parameters foresees the response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with invasive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 23, 52 (2021).

Hayashi, M., Yamamoto, Y. & Iwase, H. Clinical imaging for the prediction of neoadjuvant chemotherapy response in breast cancer. Chin. Clin. Oncol. 9, 31 (2020).

Fujioka, T. et al. Classification of breast masses on ultrasound shear wave elastography using convolutional neural networks. Ultrason Imaging 42, 213–220 (2020).

Liao, W.-X. et al. Automatic identification of breast ultrasound image based on supervised block-based region segmentation algorithm and features combination migration deep learning model. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 24, 984–993 (2019).

Zhang, X. et al. Deep learning-based radiomics of b-mode ultrasonography and shear-wave elastography: Improved performance in breast mass classification. Front. Oncol. 10, 1621 (2020).

Zhou, Y. et al. A radiomics approach with CNN for shear-wave elastography breast tumor classification. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 65, 1935–1942 (2018).

Li, H. et al. Deep learning in ultrasound elastography imaging: A review. Med. Phys. 49, 5993–6018 (2022).

Misra, S. et al. Bi-modal transfer learning for classifying breast cancers via combined B-mode and ultrasound strain imaging. IEEE Trans. Ultrason Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 69, 222–232 (2022).

Papanastasiou, G., Dikaios, N., Huang, J., Wang, C. & Yang, G. Is attention all you need in medical image analysis? A review. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform 28, 1398–1411 (2023).

Morris, D. M. et al. A novel deep learning method for large-scale analysis of bone marrow adiposity using UK Biobank Dixon MRI data. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 24, 89–104 (2024).

Mpekris, F. et al. Translational nanomedicine potentiates immunotherapy in sarcoma by normalizing the microenvironment. J. Control Rel. 353, 956–964 (2022).

Mpekris, F. et al. Normalizing tumor microenvironment with nanomedicine and metronomic therapy to improve immunotherapy. J. Control Rel. 345, 190–199 (2022).

Brigato, L. & Iocchi, L. In 2020 25th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR). 2490–2497 (IEEE).

Eisenhauer, E. A. et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur. J. Cancer 45, 228–247 (2009).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. in Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2015: 18th International Conference, Munich, Germany, October 5-9, 2015, Proceedings, Part III 18. 234-241 (Springer).

Chollet, F. in Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 1251–1258.

Szegedy, C., Vanhoucke, V., Ioffe, S., Shlens, J. & Wojna, Z. in Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2818–2826.

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. in Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 770–778.

Selvaraju, R. R. et al. in Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision. 618–626.

Riegler, J. et al. Tumor elastography and its association with collagen and the tumor microenvironment. Clin. Cancer Res. 24, 4455–4467 (2018).

Zheng, D. et al. Biomimetic nanoparticles drive the mechanism understanding of shear-wave elasticity stiffness in triple negative breast cancers to predict clinical treatment. Bioact. Mater. 22, 567–587 (2023).

Chang, J. M. et al. Clinical application of shear wave elastography (SWE) in the diagnosis of benign and malignant breast diseases. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 129, 89–97 (2011).

Chang, J. M. et al. Comparison of shear-wave and strain ultrasound elastography in the differentiation of benign and malignant breast lesions. Am. J. Roentgenol. 201, W347–W356 (2013).

Olgun, D. Ç. et al. Use of shear wave elastography to differentiate benign and malignant breast lesions. Diagn. Interven. Radiol. 20, 239 (2014).

Brassart-Pasco, S. et al. Tumor microenvironment: extracellular matrix alterations influence tumor progression. Front. Oncol. 10, 397 (2020).

Eble, J. A. & Niland, S. The extracellular matrix in tumor progression and metastasis. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 36, 171–198 (2019).

Bi, W. L. et al. Artificial intelligence in cancer imaging: clinical challenges and applications. CA: Cancer J. Clin. 69, 127–157 (2019).

Jiang, X., Hu, Z., Wang, S. & Zhang, Y. Deep learning for medical image-based cancer diagnosis. Cancers 15, 3608 (2023).

Kumar, Y., Gupta, S., Singla, R. & Hu, Y.-C. A systematic review of artificial intelligence techniques in cancer prediction and diagnosis. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 29, 2043–2070 (2022).

Voutouri, C. et al. A convolutional attention model for predicting response to chemo-immunotherapy from ultrasound elastography in mouse tumor models. Zenodo, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13771359 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This project received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement no 101069207 and 863955) to T.S. GP was supported by the MIS under Grant 5154714 of the National Recovery and Resilience Plan Greece 2.0 funded by EU under the NextGenerationEU Program

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.V., D.E., G.P., T.S. designed research, C.V., D.E., C.Z., I.S. performed research, C.V., D.E., C.Z., I.S., G.P., T.S. analyzed data, G.P., T.S. supervised the project, C.V., D.E., C.Z., I.S., G.P., T.S. wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Medicine thanks Guy Cloutier, Sanne van Lith and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Voutouri, C., Englezos, D., Zamboglou, C. et al. A convolutional attention model for predicting response to chemo-immunotherapy from ultrasound elastography in mouse tumor models. Commun Med 4, 203 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-024-00634-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-024-00634-4

This article is cited by

-

Using mathematical modelling and AI to improve delivery and efficacy of therapies in cancer

Nature Reviews Cancer (2025)