Abstract

Background

Variant-adapted vaccines are recommended in vulnerable populations to address the waning immunity and the emergence of immune-escaping SARS-CoV-2 variants, yet data about immune responses to such vaccines in people living with HIV (PLWH) are limited. We therefore aimed to assess long-term immune responses to an original–BA.4/5 mRNA booster in this population.

Methods

In this prospective longitudinal study, PLWH receiving either an original–BA.4/5 bivalent booster or an original monovalent booster and HIV-negative healthcare workers (HCWs) receiving a bivalent booster were enrolled and sampled before (T0), 1 month (T1), and 4–9 months (T2) after the vaccine administration. SARS-CoV-2–specific T and B cells, RBD-binding antibodies, and RBD-blocking antibodies against both wild type (WT) and omicron BA.4/5 virus were determined.

Results

The bivalent booster is able to transiently increase both humoral and polyfunctional T cell responses in PLWH, with humoral responses comparable to those observed in HCWs. While T cell responses are cross-reactive against viral variants and stable over time, humoral immunity is imprinted to the ancestral virus and wanes quickly. Furthermore, whilst previous SARS-CoV-2 infection does not affect the trajectory of vaccine-elicited immune responses, markers of HIV-related T cell dysfunction are associated with lower antibody peak responses and higher antibody waning. Lastly, the bivalent booster was superior to the monovalent one in inducing BA.4/5-reactive RBD-blocking antibodies.

Conclusions

The original–BA.4/5 bivalent booster is highly immunogenic in PLWH and superior to the monovalent one in inducing humoral responses against the BA.4/5 virus, although HIV-related T cell dysfunction markers are associated with blunted and less durable antibody immunity.

Plain Language Summary

SARS-CoV-2 vaccines adapted to recently circulating variants are recommended in vulnerable populations, such as people living with HIV (PLWH). In this study, we studied immune responses to a newly designed mRNA vaccine in this cohort. We showed that the vaccine could stimulate antibodies, small proteins that the body produces against the SAR-CoV-2 original and the mutant BA.4/5 variants to fight the virus. This new design produced improved antibody responses against SARS-CoV-2 mutant variants compared with older designs, but PLWH with a compromised immune system have a short-lived protection against the evolving virus.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bivalent mRNA vaccines encoding both the parental strain and either BA.1 or BA.4/5 spike proteins were deployed in fall 2022 and recommended as booster doses especially in the elderly and in immunocompromised individuals to cope with the waning of humoral immunity over time and the SARS-CoV-2 evolution leading to the continuous emergence of novel immune-escaping viral variants.

Unexpectedly, despite the ability of such vaccines to effectively boost humoral immunity, several studies reported that neutralizing antibody levels against omicron BA.4/5 and subsequent variants were lower than neutralizing antibody responses against the wild-type strain after a bivalent booster, and not discernibly better than after a monovalent original one1,2,3,4,5, although other studies concluded the otherwise6,7. Likewise, even though both monovalent and bivalent boosters have been demonstrated to provide additional protection against severe COVID-19 due to omicron subvariants8, clinical data concerning the comparison between such types of boosters are conflicting, with studies variably reporting superior9,10,11 or similar12,13 effectiveness of bivalent mRNA vaccines compared to monovalent original ones.

The apparent inability of bivalent mRNA vaccines to preferentially boost omicron-specific immune responses may be the consequence of the inclusion of the ancestral spike component in the bivalent mRNA vaccines, which may exacerbate the immunologic imprinting, a phenomenon by which the immune system recognizes antigens from previous exposures more robustly than novel slightly different antigens14. This is further supported by the observation that omicron BA.5 breakthrough infections elicit higher neutralizing antibody responses towards omicron subvariants than both monovalent and bivalent booster, suggesting that the exposure to the omicron spike alone may overcome the immunologic imprinting to the ancestral strain3,5.

People living with HIV (PLWH) were among the immunocompromised populations who were prioritized for bivalent boosters given their allegedly higher risk of impaired immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 infection and worse COVID-19 outcomes15,16,17,18. A large body of literature has shown that the primary SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine cycle elicits robust humoral and cellular responses in PLWH15, with the exception of those with unsuppressed HIV viremia and/or poor immune reconstitution on antiretroviral therapy (ART)19,20,21,22. A first booster with an ancestral-strain vaccine is able to substantially enhance neutralizing antibody levels in PLWH, including those with hyporesponse after primary vaccination23,24,25,26, although markers of HIV-related T cell dysfunction (i.e., low CD4/CD8 ratio, low functionally-competent CD4 T cells, and high primed activated CD8 T cells) have been associated with faster antibody waning27. By contrast, data on immune responses to variant-adapted vaccines in this population remain limited28,29,30,31. Moreover, whether hybrid immunity and T cell dysfunction may shape immune responses to bivalent boosters and whether immunologic imprinting may affect their immunogenicity in PLWH is currently unclear.

Given these premises, we were hereby interested in the broad assessment of cellular and humoral immune responses to an original–BA.4/5 bivalent SARS-CoV-2 mRNA booster in PLWH on effective ART as compared to HIV-negative healthcare workers (HCWs), exploring the potential impact of previous SARS-CoV-2 infection, HIV-related T cell dysfunction and immunologic imprinting in shaping vaccine-elicited immunity. We show herein that the booster is highly immunogenic in PLWH and superior to the monovalent one in inducing humoral responses against the BA.4/5 viral variant, although markers of HIV-related T cell dysfunction are associated with blunted and fleeting antibody immunity.

Methods

Study design and population

In this prospective longitudinal study, PLWH receiving either an original–BA.4/5 bivalent booster (Comirnaty® Original/Omicron BA.4/5, Pfizer-BioNTech) or an original monovalent booster (Comirnaty®, Pfizer-BioNTech) as a fourth vaccine dose were consecutively enrolled at the Clinic of Infectious Diseases and Tropical Medicine, San Paolo Hospital, ASST Santi Paolo e Carlo, Department of Health Sciences, University of Milan (Milan, Italy), between May 2022 and February 2023, and followed-up until a period between November 2022 and November 2023.

HIV-negative HCWs receiving the Comirnaty® Original/Omicron BA.4/5 booster were also enrolled in the same period at the Occupational Medicine Unit, Verona Hospital, Department of Diagnostics and Public Health, University of Verona, Verona, Italy.

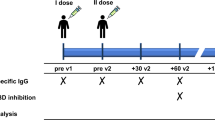

Peripheral blood samples were collected in EDTA tubes from all participants at three different time-points: the day of the booster administration (T0), 1 month after the booster (T1), and 4–9 months after the booster (T2; only for PLWH and HCWs who received the original–BA.4/5 bivalent booster) (Fig. 1a).

Schematic representation of the study design showing the time-points at which study participants were sampled (a), as well as the number of participants who were enrolled and the immune parameters that were measured at each specified time-point to explore: b peak and durability of immune responses to the original–BA.4/5 bivalent booster in PLWH either with or without previous SARS-CoV-2 infection; c the possible role of the ancestral spike in the bivalent vaccine in exacerbating immunologic imprinting thus affecting the bivalent booster immunogenicity in PLWH; d possible differences in bivalent booster immunogenicity and durability between PLWH and HIV-negative HCWs. Created in BioRender [Augello, M. (2025), https://BioRender.com/t94l162].

Demographic, clinical, and HIV-related characteristics of the study participants were collected at enrollment.

SARS-CoV-2 infection was determined by anamnesis and/or anti-nucleocapsid serology at baseline and during the follow-up period.

To determine peak and durability of immune responses to the original–BA.4/5 bivalent booster in PLWH, SARS-CoV-2–specific T and B cells as well as humoral immunity (RBD-binding and RBD-blocking antibodies) were measured at all time-points and then analyzed both overall and according to previous SARS-CoV-2 infection (Fig. 1b). The role of the HIV-related dysfunction in shaping immune responses to the booster was explored by computing the association between baseline (T0) T cell phenotypes and peak response (fold-increase, T1/T0 ratio) or waning (fold-decrease, T1/T2 ratio) of vaccine-induced cellular/humoral responses adjusting for potential confounders.

To explore the possible role of the ancestral spike in the bivalent vaccine in exacerbating immunologic imprinting thus affecting the bivalent booster immunogenicity, fold-increase of vaccine-elicited humoral immunity was compared between SARS-CoV-2–naïve PLWH vaccinated with the original–BA.4/5 booster and PLWH (without previous SARS-CoV-2 infection) who received the original monovalent booster (Fig. 1c).

Lastly, to assess whether the bivalent booster immunogenicity and durability may be lower in PLWH compared to the general population, vaccine-induced antibodies fold-increase and fold-decrease were determined in HIV-negative HCWs and compared to those of PLWH adjusting for potential confounders (Fig. 1d).

The study was approved by the local Ethics Committee (Comitato Etico Milano Area 1, protocol number 0002574, 20/01/2022) and informed consent was obtained from each participant. All research was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Plasma and peripheral blood mononuclear cells isolation

Peripheral blood samples from each participants were used to isolate plasma and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). Plasma was separated by centrifugation and stored at –80 °C until use. PBMCs were obtained by Ficoll density gradient centrifugation (Biowest Lymphosep, Lymphocyte Separation Media, Cat# L0560) and stored at –80 °C and then in liquid nitrogen until use.

Markers of HIV-related T cell dysfunction

T cell phenotypes were quantified at baseline (T0) by flow cytometry. Briefly, flow cytometry samples were prepared with the automated BD FACSDuet™ Sample Preparation System by mixing 50 μL of fresh whole blood and 40 μL of fluorescently-labeled antibodies cocktail (CD45–V500, CD4–APC-Cy7, CD8–PerCP-Cy5.5, CD127–PE, CD38–APC, CD45RA–PE-Cy7) in BD Trucount™ Tubes. After a 20-minute incubation at room temperature, red blood cells were lysed with BD FACS™ Lysing Solution. Samples were then acquired on a BD FACSLyric™ Flow Cytometry System, and fcs files analyzed with BD FACSuite™ Clinical Application software. The gating strategy for a representative sample (generated with FlowJo v10) is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. The following phenotypes were determined within the lymphocyte gate and quantified as cells/μL: CD4 T cells (CD4+), CD8 T cells (CD8+), functionally-competent CD4 T cells (CD4+CD127+), activated CD8 T cells (CD8+CD38+), naïve CD4 T cells (CD4+CD45RA+), and naïve CD8 T cells (CD8+CD45RA+).

Anti-nucleocapsid serology

Anti-nucleocapsid (N) IgG were measured by means of a commercial kit [EUROIMMUN Anti-SARS-CoV-2 NCP ELISA IgG (Cat# EI 2606-9601-2G)] according to manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, EDTA plasma samples were diluted 1:101 in dilution buffer. 100 μL of diluted samples, calibrator, positive control, and negative control were loaded in duplicate into nucleocapsid-coated wells and incubated for 1 hour at +37 °C. Plates were washed ×3, and then incubated with 100 μL/well of peroxidase-conjugated anti-human IgG antibodies for 30 minutes at room temperature (RT). After washing ×3, plates were incubated with 100 μL/well of chromogen substrate [tetramethylbenzidine (TMB)/H2O2] for 15 minutes at RT in the dark, and then the reaction was quenched with 100 μL/well of stop solution (H2SO4 0.5 M). The optical density (OD) was measured immediately by using PerkinElmer EnSight™ Multimode Plate Reader at 450 nm and 650 nm. Samples were considered positive for anti-N IgG antibodies by means of a semi-quantitative method, according to the following formula: [(sample OD450 – sample OD650) / (calibrator OD450 – calibrator OD650)] ≥1.1.

SARS-CoV-2–specific T cells

SARS-CoV-2–specific T cells reactive against WT and BA.4/5 virus were assessed in cryopreserved PBMCs by means of intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) and degranulation assay in flow cytometry. Briefly, 1.5 ×106 thawed PBMCs were plated in RPMI 1640 (EuroClone RPMI, Cat# ECB2000) supplemented with 1% L-glutamine (Gibco, Cat# 25030-149), 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Sigma, Cat# P4333-100ML), and 10% human serum, and rested for 3 hours at +37 °C in CO2 incubator. PBMCs were then stimulated for 18 hours with overlapping peptide pools derived from the WT and BA.4/5 spike protein (Miltenyi Biotec PepTivator® SARS-CoV-2 Prot_S B.1.1.529/BA.5 WT Reference Pool – research grade, Cat# 130-132-050, and Miltenyi Biotec PepTivator® SARS-CoV-2 Prot_S B.1.1.529/BA.5 Mutation Pool – research grade, Cat# 130-132-051) at a concentration of 1 μg/mL. Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxin B (SEB) (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat# S4881-1MG) at a concentration of 1 μg/mL was used as positive control, while negative controls were left untreated. CD107a–PE antibody (BD Pharmingen™, Cat# 555801) was also added to each well for the degranulation assay. After 1 hour of stimulation brefeldin A [BD GolgiPlug™ Protein Transport Inhibitor (Containing Brefeldin A), Cat# 555029] and monensin [BD GolgiStop™ Protein Transport Inhibitor (Containing Monensin), Cat# 554724] were added to wells. After stimulation, cells were harvested, washed, and stained with viability dye [Viobility Fixable Dye 405/520 (Miltenyi Biotec, Cat# 120-028-574)] for 15 minutes at room temperature (RT) in the dark. After a washing step, cells were stained for surface markers for 30 minutes at +4 °C in the dark with the following fluorescently-labeled antibodies: CD3–FITC (BD Pharmingen™, Cat# 555339), CD4–APC-Vio®770 (Miltenyi Biotec, Cat# 130-113-223), CD8–PerCP-Vio®700 (Miltenyi Biotec, Cat# 130-110-682). After washing, cells were fixed and permeabilized with fixation/permeabilization solution (BD Cytofix/Cytoperm™ Fixation/Permeabilization Kit, Cat# 554714) for 20 minutes at +4 °C, then further washed and stained for intracellular cytokines for 30 minutes at +4 °C with the following fluorescently-labeled antibodies: IFN-γ–PE-Cy™7 (BD Pharmingen™, Cat# 557643), TNF-α–V450 (BD Horizon™, Cat# 561311), and IL-2–APC (Miltenyi Biotec, Cat# 130-111-304). Cells were then washed and resuspended in PBS. Samples were acquired using FACSVerse™ cytometer (BD Biosciences) and FCS files were analyzed using FlowJo 10.9 (BD Biosciences).

SARS-CoV-2–specific T cells were determined subtracting unspecific background cytokines (IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-2) production or degranulation (CD107a) in paired unstimulated samples (negative control) from stimulated samples; negative values were set to zero. SARS-CoV-2–specific Th1 and Tc1 cells were determined using the FlowJo Boolean OR Gate to identify CD4 and CD8 T cells expressing at least one Th1-like cytokine (IFN-γ, TNF-α, or IL-2). T cell polyfunctionality was assessed by using the FlowJo Boolean Combination Gates and SPICE 6.0 to identify single-, dual-, triple- cytokine-producing SARS-CoV-2–specific Th1/Tc1 cells. Representative plots of the gating strategy are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2.

SARS-CoV-2–specific B cells

SARS-CoV-2–specific B cells reactive against WT and BA.4/5 virus were measured in cryopreserved PBMCs by means of a commercial kit (Miltenyi Biotec SARS-CoV-2 RBD B Cell Analysis Kit, anti-human, Cat# 130-128-032), according to manufacturer’s instruction with few modifications. This assay is based on a double discrimination method to identify and phenotype RBD-specific B cells in flow cytometry after staining with RBD fluorescently-labeled tetramers. Firstly, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were thawed and rested in RPMI 1640 (EuroClone RPMI, Cat# ECB2000) supplemented with 1% L-glutamine (Gibco, Cat# 25030-149), 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Sigma, Cat# P4333-100ML), and 10% human serum for 2 hours at +37 °C in CO2 incubator. In the meanwhile, RBD-tetramer solutions were prepared by mixing 15 μg/mL biotinylated WT-RBD [Recombinant SARS-CoV-2 RBD (HEK)-Biotin (provided with the kit)] or biotinylated BA.4/5-RBD [ACROBiosystems Biotinylated SARS-CoV-2 Spike RBD, His,Avitag™ (BA.4&BA.5/Omicron), Cat# SPD-C82Ew] with streptavidin–PE (for RBD-tetramer-PE) or streptavidin–PE-Vio770 (for RBD-tetramer-PE-Vio770) in PEB buffer [PBS + 0.5% BSA (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat# A7030-100G) + EDTA 2 mM (EMD Millipore, Cat# 324504-500 ML)] for 15 minutes at room temperature (RT). 5–10 ×106 thawed PBMCs were then incubated with the antibody staining cocktail for 30 minutes at +4 °C: WT-RBD-tetramers or BA.4/5-RBD-tetramers, 7-AAD Staining Solution, CD19–APC-Vio770, CD27–VioBright-FITC, IgM–APC, IgG–VioBlue®, IgA–VioGreen™. After washing, cell pellet was resuspended in PEB buffer. Samples were acquired using FACSVerse™ cytometer (BD Biosciences) and FCS files were analyzed using FlowJo 10.9 (BD Biosciences). Memory B cells were defined as CD19+CD27+ live cells. SARS-CoV-2–specific memory B cells were identified by the double discrimination method (RBD-tetramer-PE+RBD-tetramer-PE-Vio770+) within memory B cells. IgM+, IgG+, and IgA+ cells where then gated within SARS-CoV-2–specific memory B cells. Representative plots of the gating strategy are shown in Supplementary Fig. 3.

RBD-binding antibodies

Total RBD-binding antibodies reactive against WT and BA.4/5 virus were measured in EDTA plasma samples by a homemade ELISA16,20,32. Briefly, high-binding 96-well plates (Greiner Bio-One, Cat# 655061) were coated with 3 µg/mL of recombinant wild-type SARS-CoV-2 receptor binding domain (RBD) [ACROBiosystems SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) S protein RBD, His Tag (MALS verified), Cat# SPD-C52H3] or recombinant Omicron BA.4/5 SARS-CoV-2 RBD [ACROBiosystems SARS-CoV-2 Spike RBD Protein, His Tag (BA.4&BA.5/Omicron) (MALS verified), Cat# SPD-C522r] diluted in 50 mM of carbonate-bicarbonate buffer pH 9.6 (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat# C3041-50cap) and incubated overnight at +4 °C. Plates were then washed with washing buffer [PBS + 0.05% TWEEN®20 (Sigma, Cat# P9416-100ML)] and blocked for 1.5 hours with blocking buffer [PBS + 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat# A7030-100G)] at +37 °C. Plasma samples were serially diluted in assay buffer (PBS + 1% BSA) (1:200, 1:1200, 1:7200), loaded (50 μL/well) into plate wells in duplicates, and incubated for 2 hours at +37 °C. After washing ×3, a mix of biotinylated goat anti-human k and λ light chain antibodies (Bethyl Laboratories, Cat# A80-115B and A80-116B) were used at 1:2500 dilution for detection, followed by avidin-HRP (ThermoFisher, Cat# 18-4100-51) diluted at 1:2000, for 30 minutes at RT in the dark and mild agitation. After washing ×3, the detection was carried out with 3,3’,5,5’-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) (Invitrogen, Cat# 229280010) for 3–5 minutes at RT, and the reaction quenched with H2SO4 1 M (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat# 4803641000). Plasma samples collected before the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic were also included as negative controls (same dilution of test samples), whereas an RBD-specific monoclonal antibody [ACROBiosystems Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Spike RBD Antibody, Chimeric mAb, Human IgG1 (AM130), Cat# S1N-M130] was included as positive control (diluted at 1:1, 1:6, 1:36). The optical density (OD) was measured by using PerkinElmer EnSight™ Multimode Plate Reader at 450 nm and 650 nm. Samples OD values were background-subtracted [(sample OD450 – sample OD650) – (blank OD450 – blank OD650)], and the area under the curve (AUC) was determined with GraphPad Prism 10.1.

RBD-blocking antibodies

RBD-blocking antibodies reactive against WT and BA.4/5 virus, which are antibodies inhibiting the binding of the spike RBD to its receptor ACE2 and thus a surrogate of neutralizing antibodies, were measured in EDTA plasma samples by commercially available kits [ACROBiosystems Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Neutralizing Antibody Titer Serologic Assay Kit (Spike RBD), Cat# RAS-N022, and ACROBiosystems Anti-SARS-CoV-2 (BA.4&BA.5) Neutralizing Antibody Titer Serologic Assay Kit (Spike RBD), Cat# RAS-N107], according to manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 50 μL/well of diluted plasma samples (1:100 in dilution buffer), positive control, and negative control were incubated with 50 μL/well of HRP-SARS-CoV-2 Spike RBD 1 μg/mL for 1 hour at +37 °C in the dark. After washing ×3, 100 μL/well of substrate solution were added and incubated for 20 minutes at +37 °C in the dark, followed by reaction quenching with 50 μL/well of stop solution. The optical density (OD) was measured by using PerkinElmer EnSight™ Multimode Plate Reader at 450 nm and 630 nm. Samples OD values were background-subtracted (OD450 – OD630), and results were expressed as percentage (%) of inhibition of RBD-ACE2 binding, calculated as: [1 − (sample OD/negative control OD)] × 100.

Statistics and reproducibility

Continuous variables were expressed as median (interquartile range, IQR), while categorical variables as number, n (percentage, %). Kruskal-Wallis or Friedman test with Dunn’s multiple comparison test, Wilcoxon test, and Mann-Whitney test were used for comparisons of continuous variables as appropriate. Fisher exact test was employed for comparison of categorical variables. Spearman’s correlation test was used to explore correlations between continuous variables. Multivariable linear regression analysis adjusted for potential confounders was used to explore: (i) the association between markers of HIV-related T cell dysfunction (CD4+CD127+ cells, CD8+CD38+ cells, CD4+CD45RA+ cells, CD8+CD45RA+ cells, and CD4/CD8 ratio; independent variables) and immune responses to the bivalent booster in PLWH (dependent variable); (ii) the association between HIV status (independent variable) and RBD-binding/blocking antibodies fold-change following the bivalent booster (dependent variable). Details on the statistical test used are reported in the respective figure legends. Data were analyzed and graphed with GraphPad Prism 10.1. Permutation test in SPICE 6.0 was employed to compare polyfunctionality patterns of SARS-CoV-2–specific Th1/Tc1 cells. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

Study population

Thirty PLWH who received an original–BA.4/5 bivalent booster of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine were enrolled. Sixteen of them had no SARS-CoV-2 infection before the booster administration or during the follow-up period, whilst 14 participants experienced a previous SARS-CoV-2 infection (Supplementary Table 1). All participants received the booster as a fourth vaccine dose at a median time of 435 (IQR: 404–451) days from the previous one. All of them had a history of homologous mRNA vaccination. T2 was at a median of 235 (IQR: 185–272) days from T0. Participants characteristics are reported in Table 1. Briefly, median age was 51 (IQR: 42–55) years, 27 (90%) were males, and 26 (86.7%) Caucasian. Median CD4 T cell count was 790 (IQR: 598–929) cells/μL, with a median CD4/CD8 ratio of 0.78 (IQR: 0.59–1.1). All participants have been on antiretroviral therapy (ART) for a median of 134 (IQR: 65–187) months, and all of them were virologically suppressed (plasma HIV-RNA < 20 copies/mL).

Fifteen PLWH (without previous SARS-CoV-2 infection) who received an original monovalent booster as a fourth dose were also recruited. They were comparable to PLWH who received the original–BA.4/5 bivalent booster in terms of demographic characteristics, although PLWH receiving the monovalent booster had a lower CD4 T cell count [530 (IQR: 310–648) cells/μL versus 781 (IQR: 623–921) cells/μL, P = 0.0267] (Supplementary Table 2).

As controls, 19 HIV-negative HCWs who received an original–BA.4/5 bivalent booster as a fourth mRNA vaccine dose were enrolled. HCWs were mostly females [16 (84.2%) versus 3 (10%), P < 0.0001] and older than PLWH [median age: 59 (IQR: 54–62) years versus 51 (IQR: 42–55) years, P = 0.0003]. Most of them (15/19, 78.95%) had no comorbidities, two had arterial hypertension, one a cardiovascular disease, and another one a respiratory system disease. Eight out of 19 had a history of previous SARS-CoV-2 infection (Supplementary Table 1). The median interval between T0 and T2 was shorter than in the PLWH cohort [132 (IQR: 119–138) days versus 235 (IQR: 185–272) days, P < 0.0001].

SARS-CoV-2–specific T cell responses after bivalent booster

Firstly, wild type (WT)- and omicron BA.4/5-reactive SARS-CoV-2–specific T cells were quantitatively and qualitatively assessed in PLWH by means of flow cytometry after stimulation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) with overlapping peptide pools derived from the WT and BA.4/5 spike protein.

Frequencies of SARS-CoV-2–specific Th1 and cytotoxic (CD107a+) CD4 T cells were not increased after the bivalent booster, and were equally reactive against WT and BA.4/5 virus as well as being stable across time-points; additionally, no significant differences in Th1 cells trajectories were detected according to previous SARS-CoV-2 infection (Fig. 2a–c).

Frequency (percentage, %) of total SARS-CoV-2–specific Th1 (IFN-γ+ or TNF-α+ or IL-2+) cells reactive against WT and BA.4/5 virus within CD4 T cells in the entire cohort (a) and in PLWH stratified according to previous SARS-CoV-2 infection (b). c Frequency (percentage, %) of SARS-CoV-2–specific cytotoxic (CD107a+) CD4 T cells reactive against WT and BA.4/5 virus within CD4 T cells. Frequency (percentage, %) of SARS-CoV-2–specific CD4 T cells producing IFN-γ+ (d), TNF-α+ (e), or IL-2+ (f) reactive against WT and BA.4/5 virus within CD4 T cells. g Donut charts showing the median distribution of polyfunctionality profiles within SARS-CoV-2–specific Th1 cells; the donut slices represent median percentages of tri- (3+), bi- (2+), and mono- (1+) functional Th1 cells reactive against WT and BA.4/5 virus; the arches around the circumference indicate the particular cytokine (IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-2) produced by the portion of T cells that lie under the arc; parts of the donut surrounded by multiple arches represent polyfunctional cells. h Frequency (percentage, %) of trifunctional (IFN-γ+TNF-α+IL-2+) SARS-CoV-2–specific Th1 cells reactive against WT and BA.4/5 virus within CD4 T cells. Green/orange circles (scatter plots): individual values; black bars (scatter plots): median values; green/orange boxes (scatter plots): interquartile ranges; green/orange diamonds and triangles (trajectory plots): median values; green/orange error bars (trajectory plots): interquartile ranges; statistical analyses in scatter plots: Kruskall–Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test (comparison between time-points; P values < 0.1 showed in green or orange above solid lines) and Wilcoxon test (comparison between WT- and BA.4/5-reactive T cells; P values < 0.1 showed in black above dashed lines); statistical analyses in trajectory plots: Mann–Whitney test (comparison between PLWH with no SARS-CoV-2 infection and PLWH with previous SARS-CoV-2 infection); statistical analyses between donut charts: permutation test; T0 (day of booster administration): n = 25; T1 (1 month after booster administration): n = 26; T2 (4–9 months after booster administration): n = 23. SARS-CoV-2–specific T cells were measured subtracting unspecific cytokine production in paired unstimulated control samples from stimulated samples.

However, when assessing the intracellular production of specific Th1 cytokines, IFN-γ+SARS-CoV-2–specific CD4 T cells appeared to be quantitively more reactive towards WT than BA.4/5 virus at both T0 and T1 (Fig. 2d–f).

Despite stable frequencies of total SARS-CoV-2–specific CD4 T cells, the bivalent booster induced a transient increase of trifunctional IFN-γ+TNF-α+IL-2+CD4 T cells reactive against both WT and BA.4/5 at T1, followed by a reduction to baseline levels at T2; however, polyfunctional CD4 T cell responses were higher against WT than BA.4/5 at all time-points (Fig. 2g–h).

Similarly as described for CD4 T cells, the bivalent booster did not increase frequencies of SARS-CoV-2–specific Tc1 and cytotoxic CD8 T cells; moreover, no differences were detected according to variant-reactivity or previous SARS-CoV-2 infection (Fig. 3a–c). However, WT-reactive IFN-γ+CD8 T cells were higher than BA.4/5–reactive ones at T1 (Fig. 3d–f). As far as polyfunctionality profiles, the bivalent booster administration was followed by a transient increase in bifunctional IFN-γ+TNF-α+IL-2– WT-reactive CD8 T cells, which thus outnumbered BA.4/5-reactive ones; furthermore, a shift of BA.4/5-reactive monovalent CD8 T cells from IFN-γ to TNF-α and IL-2 production was also observed upon the booster administration (Fig. 3g–h).

Frequency (percentage, %) of total SARS-CoV-2–specific Tc1 (IFN-γ+ or TNF-α+ or IL-2+) cells reactive against WT and BA.4/5 virus within CD8 T cells in the entire cohort (a) and in PLWH stratified according to previous SARS-CoV-2 infection (b). c Frequency (percentage, %) of SARS-CoV-2–specific cytotoxic (CD107a+) CD8 T cells reactive against WT and BA.4/5 virus within CD8 T cells. Frequency (percentage, %) of SARS-CoV-2–specific CD8 T cells producing IFN-γ+ (d), TNF-α+ (e), or IL-2+ (f) reactive against WT and BA.4/5 virus within CD8 T cells. g Donut charts showing the median distribution of polyfunctionality profiles within SARS-CoV-2–specific Tc1 cells; the donut slices represent median percentages of tri- (3+), bi- (2+), and mono- (1+) functional Tc1 cells reactive against WT and BA.4/5 virus; the arches around the circumference indicate the particular cytokine (IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-2) produced by the portion of T cells that lie under the arc; parts of the donut surrounded by multiple arches represent polyfunctional cells. h Frequency (percentage, %) of bifunctional (IFN-γ+TNF-α+IL-2–) SARS-CoV-2–specific Tc1 cells reactive against WT and BA.4/5 virus within CD8 T cells. Green/orange circles (scatter plots): individual values; black bars (scatter plots): median values; green/orange boxes (scatter plots): interquartile ranges; green/orange diamonds and triangles (trajectory plots): median values; green/orange error bars (trajectory plots): interquartile ranges; statistical analyses in scatter plots: Kruskall–Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test (comparison between time-points; P values < 0.05 showed in green or orange above solid lines) and Wilcoxon test (comparison between WT- and BA.4/5-reactive T cells; P values < 0.05 showed in black above dashed lines); statistical analyses in trajectory plots: Mann–Whitney test (comparison between PLWH with no SARS-CoV-2 infection and PLWH with previous SARS-CoV-2 infection); statistical analyses between donut charts: permutation test; T0 (day of booster administration): n = 25; T1 (1 month after booster administration): n = 26; T2 (4–9 months after booster administration): n = 23. SARS-CoV-2–specific T cells were measured subtracting unspecific cytokine production in paired unstimulated control samples from stimulated samples.

When performing a multivariable linear regression analysis adjusted for age, sex, previous SARS-CoV-2 infection, baseline/peak levels and – for the fold-decrease analysis – days between T0 and T2, we did not find any association between baseline markers of HIV-related T cell dysfunction (CD4+CD127+ cells, CD8+CD38+ cells, CD4+CD45RA+ cells, CD8+CD45RA+ cells, and CD4/CD8 ratio) and fold-increase or fold-decrease of polyfunctional SARS-CoV-2–specific T cells.

SARS-CoV-2–specific B cell responses after bivalent booster

Next, SARS-CoV-2–specific memory B cells were evaluated in PLWH by flow cytometry following staining of PBMCs with WT- and BA.4/5-RBD fluorescently-labeled tetramers.

The original–BA.4/5 bivalent booster did not significantly increase frequencies of SARS-CoV-2–specific memory B cells reactive against WT and BA.4/5 virus; actually, a reduction in WT-reactive memory B cells was observed in the long term compared to baseline, although they were higher than those reactive towards BA.4/5 at all time-points (Fig. 4a). Moreover, no differences were detected according to previous SARS-CoV-2 infection (Fig. 4b).

Frequency (percentage, %) of SARS-CoV-2–specific memory B cells reactive against WT and BA.4/5 virus within memory B cells in the entire cohort (a) and in PLWH stratified according to previous SARS-CoV-2 infection (b). c Donut charts showing the median distribution of IgM+, IgG+, and IgA+ cells within SARS-CoV-2–specific memory B cells. Green/orange circles (scatter plots): individual values; black bars (scatter plots): median values; green/orange boxes (scatter plots): interquartile ranges; green/orange diamonds and triangles (trajectory plots): median values; green/orange error bars (trajectory plots): interquartile ranges; statistical analyses in scatter plots: Kruskall–Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test (comparison between time-points; P values < 0.05 showed in green or orange above solid lines) and Wilcoxon test (comparison between WT- and BA.4/5-reactive T cells; P values < 0.05 showed in black above dashed lines); statistical analyses in trajectory plots: Mann–Whitney test (comparison between PLWH with no SARS-CoV-2 infection and PLWH with previous SARS-CoV-2 infection); T0 (day of booster administration): n = 15; T1 (1 month after booster administration): n = 15; T2 (4–9 months after booster administration): n = 12.

When assessing antibody classes (IgM, IgG, or IgA) expressed on the surface of virus-specific memory B cells, no striking changes were observed after the booster administration, with IgG+ cells being the more abundant across time-points, whilst IgA+ ones the less represented (Fig. 4c).

WT-reactive memory B cells were positively correlated with WT-reactive Th1 cells at T0, and with WT-reactive cytotoxic CD8 T cells at T1. BA.4/5-reactive memory B cells were positively correlated with BA.4/5-reactive cytotoxic CD4 T cells at T0, and with BA.4/5-reactive cytotoxic CD4 T cells at T1 (Supplementary Fig. 4). No correlations were found between SARS-CoV-2–specific memory B cells and T cells at T2.

SARS-CoV-2–specific humoral responses after bivalent booster

Then, vaccine-elicited humoral immunity was comparatively investigated in PLWH and HIV-negative HCWs by RBD-binding and RBD-blocking antibodies (a known surrogate of neutralizing antibodies).

Both RBD-binding and RBD-blocking WT- and BA.4/5-reactive total antibodies were transiently increased in PLWH upon the bivalent booster, with a subsequent reduction to baseline levels at T2. WT-reactive antibodies were higher than BA.4/5-reactive ones at all time-points. Moreover, no significant differences were recorded in trajectories of humoral responses according to prior SARS-CoV-2 infection (Fig. 5a–d). As expected, RBD-binding antibodies and RBD-blocking antibodies were positively correlated at all time-points (Fig. 5e).

RBD-binding antibodies – expressed as area under the curve (AUC) – against WT and BA.4/5 virus in the entire cohort of PLWH (a) and in PLWH stratified according to previous SARS-CoV-2 infection (b). RBD-blocking antibodies – expressed as percentage (%) of inhibition of RBD-ACE2 binding – against WT and BA.4/5 virus in the entire cohort of PLWH (c) and in PLWH stratified according to previous SARS-CoV-2 infection (d). Green/orange circles (scatter plots): individual values; black bars (scatter plots): median values; green/orange boxes (scatter plots): interquartile ranges; green/orange diamonds and triangles (trajectory plots): median values; green/orange error bars (trajectory plots): interquartile ranges; statistical analyses in scatter plots: Kruskall–Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test (comparison between time-points; P values < 0.05 showed in green or orange above solid lines) and Wilcoxon test (comparison between WT- and BA.4/5-reactive T cells; P values < 0.05 showed in black above dashed lines); statistical analyses in trajectory plots: Mann–Whitney test (comparison between PLWH with no SARS-CoV-2 infection and PLWH with previous SARS-CoV-2 infection); T0 (day of booster administration): n = 29; T1 (1 month after booster administration): n = 29; T2 (4–9 months after booster administration): n = 24. e Correlation between RBD-binding and RBD-blocking antibodies. Green/orange circles: individual values; solid black line: simple linear regression line; green/orange shadows: 95% confidence bands; statistical analysis: Spearman’s correlation test (r and P value reported above the plot).

Trajectories of vaccine-elicited humoral responses in HCWs were similar to those observed in PLWH (Fig. 6a–d), as were correlations between RBD-binding and RBD-blocking antibodies (Fig. 6e).

RBD-binding antibodies – expressed as area under the curve (AUC) – against WT and BA.4/5 virus in the entire cohort of HCWs (a) and in HCWs stratified according to previous SARS-CoV-2 infection (b). RBD-blocking antibodies – expressed as percentage (%) of inhibition of RBD-ACE2 binding – against WT and BA.4/5 virus in the entire cohort of HCWs (c) and in HCWs stratified according to previous SARS-CoV-2 infection (d). Green/orange hexagons (scatter plots): individual values; black bars (scatter plots): median values; green/orange boxes (scatter plots): interquartile ranges; green/orange diamonds and triangles (trajectory plots): median values; green/orange error bars (trajectory plots): interquartile ranges; statistical analyses in scatter plots: Friedman test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test (comparison between time-points; P values < 0.05 showed in green or orange above solid lines) and Wilcoxon test (comparison between WT- and BA.4/5-reactive T cells; P values < 0.05 showed in black above dashed lines); statistical analyses in trajectory plots: Mann–Whitney test (comparison between HCWs with no SARS-CoV-2 infection and HCWs with previous SARS-CoV-2 infection); T0 (day of booster administration): n = 19; T1 (1 month after booster administration): n = 19; T2 (4–9 months after booster administration): n = 19. e Correlation between RBD-binding and RBD-blocking antibodies. Green/orange hexagons: individual values; solid black line: simple linear regression line; green/orange shadows: 95% confidence bands; statistical analysis: Spearman’s correlation test (r and P value reported above the plot).

When comparing fold-changes of vaccine-induced antibodies between PLWH and HCWs, no differences were found in fold-increase of RBD-binding/blocking antibodies in the two groups, except for a lower increase of BA.4/5-reactive RBD-blocking antibodies in PLWH (Fig. 7a, d). Instead, fold-decrease of both RBD-binding and RBD-blocking antibodies was higher in PLWH compared to HCWs (Fig. 7b, e). However, when assessing the association between HIV status and antibody fold-changes by a multivariable regression model adjusted for potential confounders (sex, age, previous SARS-CoV-2 infection, baseline/peak antibody levels and – for the fold-decrease analysis – days between T0 and T2), HIV status appeared to significantly affect neither the fold-increase nor the fold-decrease of RBD-binding/blocking antibodies reactive against the WT and BA.4/5 virus (Fig. 7c, f).

Fold-increase (T1/T0 ratio) and fold-decrease (T1/T2 ratio) of total RBD-binding (a, b) and RBD-blocking antibodies (d, e) against WT and BA.4/5 virus in PLWH (nT1/T0 = 29, nT1/T2 = 23) and HCWs (n = 19) receiving the bivalent booster. Values equals to 1 indicate no increase/decrease, while values higher than 1 indicate an increase/decrease. Green/orange circles and hexagons: individual values; black bars: median values; green/orange boxes: interquartile ranges; statistical analyses: Mann–Whitney test (comparison between PLWH and HCWs; P values < 0.05 showed in green or orange above solid lines) and Wilcoxon test (comparison between WT- and BA.4/5-reactive antibodies; P values < 0.05 showed in black above dashed lines). c, f Multivariable linear regression analysis exploring the association between HIV status (independent variable) and RBD-binding/blocking antibodies fold-change (dependent variable) adjusted for potential confounders as specified below the forest plot. Green/orange circles: β coefficient; black error bars: 95% confidence interval (CI).

We then assessed the possible role of markers of HIV-related T cell dysfunction in shaping humoral responses to the bivalent booster in PLWH. By fitting a multivariable linear regression model adjusted for age, sex, previous SARS-CoV-2 infection and baseline antibody levels, fold-increase of RBD-binding antibodies appeared positively associated with CD4+CD127+ and CD8+CD45RA+ cells, while fold-increase of RBD-blocking antibodies with CD4+CD127+ cells. Likewise, fold-decrease of RBD-blocking antibodies was positively associated with CD8+CD38+ cells at multivariable regression analysis adjusted for age, sex, previous SARS-CoV-2 infection, peak antibody levels and days between T0 and T2 (Supplementary Table 3).

SARS-CoV-2–specific humoral responses after monovalent or bivalent booster

To delve into the possible role of immunologic imprinting in affecting immunogenicity of the bivalent booster in PLWH, fold-increase of vaccine-elicited humoral immunity was comparatively assessed in PLWH who received the original–BA.4/5 bivalent booster and those who received an original monovalent booster.

Bivalent and monovalent boosters induced a similar increase of RBD-binding antibodies (Fig. 8a). However, while monovalent booster mainly induced WT-reactive RBD-blocking antibodies, bivalent booster mainly elicited BA.4/5-reactive RBD-blocking antibodies (Fig. 8b).

Fold-increase (T1/T0 ratio) of total RBD-binding (a) and RBD-blocking antibodies (b) against WT and BA.4/5 virus in PLWH (without previous SARS-CoV-2 infection) receiving monovalent (MV) original (n = 15) or bivalent (BV) original–BA.4/5 booster (n = 16). Values equals to 1 indicate no increase, while values higher than 1 indicate an increase. Green/orange squares and diamonds: individual values; black bars: median values; green/orange boxes: interquartile ranges; statistical analyses: Mann–Whitney test (comparison between PLWH receiving MV or BV booster; P values < 0.05 showed in green or orange above solid lines) and Wilcoxon test (comparison between WT- and BA.4/5-reactive antibodies; P values < 0.05 showed in black above dashed lines).

Discussion

Variant-adapted SARS-CoV-2 vaccines are recommended in fragile populations to cope with the waning immunity and the emergence of immune-escaping viral variants, although knowledge on the immunogenicity and the durability of immune memory to such vaccines in PLWH is limited. In this prospective longitudinal study, we sought to detail immune responses to an original–BA.4/5 bivalent mRNA booster in PLWH on effective ART, exploring the role of hybrid immunity, HIV-related T cell dysfunction and immunologic imprinting in shaping vaccine-induced immunity.

We found that the original–BA.4/5 bivalent booster transiently increases polyfunctionality of SARS-CoV-2–specific Th1 and Tc1 cells, as well as RBD-binding and RBD-blocking antibodies reactive towards both WT and BA.4/5 virus. Given that polyfunctional T cells have been associated with protection from severe disease, while humoral immunity has been chiefly related with protection from infection16,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40, these data suggest that the bivalent booster can enhance protection against both acquisition of infection and, in case of infection establishment, severe disease. Prior studies in immunocompetent and immunocompromised individuals showed that SARS-CoV-2 monovalent and bivalent mRNA boosters markedly increase neutralizing antibody levels but do not substantially augment T cell responses1,23,25,28,41. However, these studies only analyzed total T cell immunity, thus failing to detect any enhancement in polyfunctionality of SARS-CoV-2–specific T cells.

Despite the remarkable increase of RBD-binding and RBD-blocking antibodies, no significant rise in SARS-CoV-2–specific memory B cells frequencies was observed upon the booster administration. As reported by previous research42,43,44, although we did not specifically assess B cell clones, this finding may suggest that vaccine-induced enhancement of humoral immunity is primarily due to recall of pre-existing memory B cells with subsequent differentiation in antibody-secreting cells (ASCs), rather than de novo priming of naïve B cells in germinal centers.

Interestingly, when delving into the possible role of the HIV-related T cell dysfunction in shaping immune responses to the bivalent booster in PLWH, we found that such peculiar alterations of the T cell phenotypes are associated with blunted and less durable antibody responses: in detail, low counts of both functionally-competent CD4 T cells and naïve CD8 T cells are associated with reduced fold-increase of humoral immunity upon vaccination, while high counts of activated CD8 T cells are associated with greater fold-decrease of RBD-blocking antibodies later on. These relationships are not surprising when considered in the context of the well-known association between the persistent T cell dysregulation despite ART and adverse immunological/clinical outcomes45,46,47 as well as poor vaccine immunogenicity in PLWH48,49. These findings are also in accordance with a previous study by our group that reported low CD4+CD127+ cells and high CD8+CD38+CD45RO+ cells to be associated with faster antibody waning following mRNA booster vaccination in PLWH27.

Noteworthy, a remarkable interindividual variability in SARS-CoV-2–specific immunity was observed at all time-points, especially in RBD-blocking antibodies. Although we have not specifically addressed the issue herein, this variability may be attributable at least partially to the underlying genetic landscape of vaccinees, as human leukocyte antigen (HLA) allelic composition and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in cytokine and cytokine receptor genes have been recognized as key determinants of interindividual variability in immune responses to different vaccines50,51, including those against SARS-CoV-252.

Remarkably, in keeping with previous literature which reported antibody levels to wane more rapidly than T cells after both natural infection53 and vaccination20,54,55,56, we displayed herein that while vaccine-induced humoral responses wane quite quickly, returning to baseline levels between 4 and 9 months after the bivalent booster administration, percentages of SARS-CoV-2–specific CD4 and CD8 T cells remain stable over time, thus ensuring long-lasting protection from severe disease.

When assessing the possible role of previous SARS-CoV-2 infection in modulating immune responses to the original–BA.4/5 bivalent booster in our cohort of PLWH, we did not find discernable differences in baseline levels or trajectories of both cellular and humoral immunity according to past infection status. This is in accordance with a recent study showing no differences in humoral and T-cell responses after the BA.1-containing mRNA-1273.214 bivalent vaccine between PLWH with hybrid immunity and those with vaccine-induced immunity alone30. Likewise, no significant differences in WT- and BA.5-reactive T cells after a BA.5-containing bivalent booster were found between PLWH who had evidence of natural infection versus those who did not in another study31. Although hybrid immunity, derived from a combination of infection and vaccination, has been shown to ensure immune protection which is higher in both magnitude and durability than that provided by either infection or vaccination alone57, previous SARS-CoV-2 infection may have a greater influence on the immune response to the primary cycle than to booster doses, as recently reported in another cohort of PLWH22.

We also found that, while total SARS-CoV-2–specific T cell responses are equally reactive towards WT and BA.4/5 virus, thus pointing to cross-reactivity of T cells to viral variants as previously reported33, BA.4/5-reactive IFN-γ+ and polyfunctional CD4 and CD8 T cells are less abundant than those reactive against the WT virus both before and following the bivalent booster administration. Likewise, a dominance of SARS-CoV-2–specific memory B cells as well as RBD-binding and RBD-blocking antibodies towards the parental strain was observed across time-points. These findings are in line with previous reports on neutralizing antibodies after bivalent vaccination1,2,3,4,5,58, and may result from immunologic imprinting by previous exposures to the monovalent vaccines and/or to the ancestral SARS-CoV-2 virus14.

However, it is worth noting that although the immunologic imprinting may be a theoretical concern, and a possible negative effect on protection from omicron infection has been indeed evidenced59,60, imprinting with pre-omicron strains do not necessarily compromise protection against severe disease sustained by infection with omicron subvariants59,61,62. Such clinical data are indeed in agreement with our and previous immunological laboratory observations suggesting that immunologic imprinting chiefly affect humoral immunity14, which is involved in protection from infection, while protection from severe disease primarily rely on T cell immunity which is relatively shielded by immunologic imprinting owing to T cell cross-reactivity.

In light of such findings, to further delve into the possible role of the ancestral spike in the bivalent vaccine in exacerbating immunologic imprinting thus affecting the bivalent booster immunogenicity, we then comparatively assessed the fold-increase of humoral responses following either the original–BA.4/5 bivalent booster or the original monovalent booster. We found that, despite comparable increase in RBD-binding antibodies, the bivalent booster mostly expanded BA.4/5-reactive RBD-blocking antibodies. Since neutralization activity has been described as the better correlate of protection from SARS-CoV-2 infection63,64,65, such data point to a superiority of the bivalent vaccine in boosting anti-omicron protective humoral immunity in PLWH.

Lastly, to determine whether the bivalent booster immunogenicity and durability are lower in PLWH compared to the general population, fold-changes of vaccine-elicited antibodies were compared between PLWH and a cohort of HIV-negative HCWs. When accounting for potential confounders, both fold-increase and fold-decrease of RBD-binding and RBD-blocking antibodies appeared to be unaffected by the HIV status. This is in keeping with previous research reporting that while immune responses to the primary SARS-CoV-2 vaccine cycle may be lower in some PLWH15, immunogenicity of original or variant-adapted booster doses in PLWH is comparable to those observed in the general population30,31,66,67.

A strength of the present study is the detailed characterization of both cellular and humoral responses up to 9 months from the bivalent booster administration in PLWH, therefore providing insights not only into immunogenicity yet also into immune memory durability in this fragile population. However, some limitations should be acknowledged. Firstly, the sample size is relatively small and PLWH with low CD4 T cell counts are not represented in this cohort, thus potentially hindering the generalizability of our findings. Secondly, PLWH receiving the bivalent booster and those receiving the monovalent original one were not matched for CD4 T cell counts, with the latter featuring significantly lower CD4 T cells; however, as median CD4 T cell counts were higher than 500 cells/μL in both groups, and since parameters of immune recovery have been reported not to affect immunogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 boosters, this discrepancy is unlikely to have biased our results. Furthermore, owing to unavailability of PBMCs, only humoral responses have been compared between the two aforementioned groups; nevertheless, total SARS-CoV-2–specific T cell responses appeared to be equally reactive against WT and BA.4/5, hence pointing to a relative sparing of T cell immunity from immunologic imprinting. Likewise, no PBMCs were available from HIV-negative HCWs, hence limiting the possibility of this study to draw definite conclusions about the ability of the bivalent booster to appropriately enhance cellular immunity in PLWH; yet, T cell responses after BA.1- or BA.5-containing bivalent vaccines have been shown similar in people with and without HIV in recent studies30,31, thus suggesting a negligible influence of the HIV status on the cellular immunogenicity of variant-adapted vaccines. Additionally, previous SARS-CoV-2 infection was defined based on anamnesis (without knowing the exact number of exposures) and/or anti-nucleocapsid serology positivity (which is intrinsically limited by its quick waning), therefore it might be not completely accurate. Furthermore, immune reactivity towards more recent circulating variants such as XBB.1.5, BA.2.86, and EG.5 has not been specifically tested in this study; however, a relative effectiveness of the original–BA.4/5 bivalent booster in preventing severe COVID-19 during the circulation of omicron XBB.1.5 and other sublineages has been reported68,69, therefore reassuring about the effectiveness of such vaccines against emerging viral variants. Lastly, although it would have been interesting to compare individuals receiving the bivalent vaccine as a booster and those receiving it alone as a first vaccine dose, such a comparison were not possible in our cohort as variant-adapted bivalent vaccines were deployed in fall 2022, when the vast majority of the population including PLWH had already received two or three doses of the monovalent vaccine against the ancestral virus. In this respect, a study leveraging a mouse model showed that Omicron mRNA vaccine alone, WT mRNA vaccine alone, and Omicron mRNA vaccine as a heterologous booster on top of WT mRNA vaccine were all able to elicit broad antibody responses, including activities against SARS-CoV-2 variants70. Given that antibody responses to vaccination are conserved between mouse and human71, we believe that these preclinical findings may also be translated into humans.

In conclusion, this study showcases that the original–BA.4/5 bivalent mRNA vaccine is able to transiently boost both humoral and polyfunctional T cell responses in PLWH on effective ART, thus providing additional protection from both infection and severe disease. While T cell responses are cross-reactive against viral variants and stable over time, hence ensuring long-lasting protection from severe COVID-19, humoral responses are strikingly imprinted to the ancestral virus and wane quickly. Furthermore, whilst previous SARS-CoV-2 infection does not affect the trajectory of vaccine-elicited immune responses, markers of HIV-related T cell dysfunction are associated with lower antibody peak responses and higher antibody waning. Future research is required to understand the clinical implications of these immune response patterns in the current COVID-19 endemic phase and to determine whether further SARS-CoV-2 vaccine boosters should be prioritized in PLWH.

Data availability

All source data used to generate Figs. 2–8 are provided as supplementary data (Supplementary Data 1–10). Given their sensitive nature, individual-level data used to generate Table 1 (demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population) are not publicly available due to national data privacy regulations; however, they will be made available on reasonable request from corresponding author in an anonymized form in accordance with the institutional data-sharing protocols.

References

Collier, A. Y. et al. Immunogenicity of BA.5 Bivalent mRNA Vaccine Boosters. N. Engl. J. Med. 388, 565–567 (2023).

Wang, Q. et al. Antibody Response to Omicron BA.4-BA.5 Bivalent Booster. N. Engl. J. Med. 388, 567–569 (2023).

Wang, Q. et al. SARS-CoV-2 neutralising antibodies after bivalent versus monovalent booster. Lancet Infect. Dis. 23, 527–528 (2023).

Hoffmann, M. et al. Effect of hybrid immunity and bivalent booster vaccination on omicron sublineage neutralisation. Lancet Infect. Dis. 23, 25–28 (2023).

Wang, Q. et al. Deep immunological imprinting due to the ancestral spike in the current bivalent COVID-19 vaccine. Cell Rep. Med. 4, 101258 (2023).

Davis-Gardner, M. E. et al. Neutralization against BA.2.75.2, BQ.1.1, and XBB from mRNA Bivalent Booster. N. Engl. J. Med. 388, 183–185 (2023).

Zou, J. et al. Neutralization of BA.4-BA.5, BA.4.6, BA.2.75.2, BQ.1.1, and XBB.1 with Bivalent Vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 388, 854–857 (2023).

Mateo-Urdiales, A. et al. Relative effectiveness of monovalent and bivalent mRNA boosters in preventing severe COVID-19 due to omicron BA.5 infection up to 4 months post-administration in people aged 60 years or older in Italy: a retrospective matched cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 23, 1349–1359 (2023).

Tan, C. Y. et al. Effectiveness of bivalent mRNA vaccines against medically attended symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19-related hospital admission among SARS-CoV-2-naive and previously infected individuals: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 23, 1343–1348 (2023).

Chae, C. et al. Comparing the effectiveness of bivalent and monovalent COVID-19 vaccines against COVID-19 infection during the winter season of 2022-2023: A real-world retrospective observational matched cohort study in the Republic of Korea. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 135, 95–100 (2023).

Auvigne, V., Tamandjou Tchuem, C. R., Schaeffer, J., Vaux, S. & Parent Du Chatelet, I. Protection against symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection conferred by the Pfizer-BioNTech Original/BA.4-5 bivalent vaccine compared to the mRNA Original monovalent vaccines - A matched cohort study in France. Vaccine 41, 5490–5493 (2023).

Wong, C. K. H., Lau, K. T. K., Au, I. C. H., Lau, E. H. Y. & Cowling, B. J. Comparison of bivalent and monovalent mRNA vaccine boosters. Clin. Infect. Dis.78, 633–636 (2024).

Grewal, R. et al. Effectiveness of mRNA COVID-19 monovalent and bivalent vaccine booster doses against Omicron severe outcomes among adults aged ≥50 years in Ontario, Canada: a Canadian Immunization Research Network (CIRN) Study. J. Infect. Dis. 229, 394–397 (2024).

Koutsakos, M. & Ellebedy, A. H. Immunological imprinting: Understanding COVID-19. Immunity 56, 909–913 (2023).

Augello, M., Bono, V., Rovito, R., Tincati, C. & Marchetti, G. Immunologic Interplay Between HIV/AIDS and COVID-19: Adding Fuel to the Flames? Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 20, 51–75 (2023).

Augello, M. et al. Association between SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia, skewed T cell responses, inflammation, and severity in hospitalized COVID-19 people living with HIV. iScience 27, 108673 (2024).

Giacomelli, A. et al. Risk of COVID-19 in-hospital mortality in people living with HIV compared to general population according to age and CD4 strata: data from the ICONA network. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 136, 127–135 (2023).

Alrubayyi, A. et al. Characterization of humoral and SARS-CoV-2 specific T cell responses in people living with HIV. Nat. Commun. 12, 5839 (2021).

Antinori, A. et al. Humoral and Cellular Immune Response Elicited by mRNA Vaccination Against Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in People Living With Human Immunodeficiency Virus Receiving Antiretroviral Therapy Based on Current CD4 T-Lymphocyte Count. Clin. Infect. Dis. 75, e552–e563 (2022).

Augello, M. et al. Six-month immune responses to mRNA-1273 vaccine in combination antiretroviral therapy treated late presenter people with HIV according to previous SARS-CoV-2 infection. AIDS 37, 1503–1517 (2023).

Vergori, A. et al. SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Vaccine Response in People Living with HIV According to CD4 Count and CD4/CD8 Ratio. Vaccines 11, 1664 (2023).

Montesi, G. et al. Predicting humoral responses to primary and booster SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination in people living with HIV: a machine learning approach. J. Transl. Med. 22, 432 (2024).

Tau, L. et al. Humoral and Cellular Immune Responses of People Living With Human Immunodeficiency Virus After 3 Doses of Messenger RNA BNT162b2 Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Vaccine: A Prospective Cohort Study. Open Forum. Infect. Dis. 10, ofad347 (2023).

Lapointe, H. R. et al. People With Human Immunodeficiency Virus Receiving Suppressive Antiretroviral Therapy Show Typical Antibody Durability After Dual Coronavirus Disease 2019 Vaccination and Strong Third Dose Responses. J. Infect. Dis. 227, 838–849 (2023).

Vergori, A. et al. Immunogenicity to COVID-19 mRNA vaccine third dose in people living with HIV. Nat. Commun. 13, 4922 (2022).

Jongkees, M. J. et al. Immunogenicity of an Additional mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination in People With HIV With Hyporesponse After Primary Vaccination. J. Infect. Dis. 227, 651–662 (2023).

Augello, M. et al. Markers of T-cell dysfunction and not inflammaging predict the waning of humoral responses to SARS-CoV-2 mRNA booster vaccination in people with HIV. AIDS 38, 1987–1990 (2024).

Vergori, A. et al. Neutralizing activity and T-cell response after bivalent fifth dose of messenger RNA vaccine in people living with HIV. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 134, 195–199 (2023).

Cheung, P. K. et al. SARS-CoV-2 live virus neutralization after four COVID-19 vaccine doses in people with HIV receiving suppressive antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 37, F11–F18 (2023).

Jongkees, M. J. et al. Immunogenicity of a bivalent BA.1 COVID-19 booster vaccine in people with HIV in the Netherlands. AIDS 38, 1355–1365 (2024).

Sop, J. et al. Bivalent mRNA COVID vaccines elicit predominantly cross-reactive CD4. Cell Rep. Med. 5, 101442 (2024).

Rovito, R. et al. Association between SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia and dysregulated immune response in acutely ill hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Sci. Rep. 12, 19658 (2022).

Sette, A. & Crotty, S. Adaptive immunity to SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Cell 184, 861–880 (2021).

Tan, A. T. et al. Early induction of functional SARS-CoV-2-specific T cells associates with rapid viral clearance and mild disease in COVID-19 patients. Cell Rep. 34, 108728 (2021).

Chandran, A. et al. Rapid synchronous type 1 IFN and virus-specific T cell responses characterize first wave non-severe SARS-CoV-2 infections. Cell Rep. Med. 3, 100557 (2022).

Rydyznski Moderbacher, C. et al. Antigen-Specific Adaptive Immunity to SARS-CoV-2 in Acute COVID-19 and Associations with Age and Disease Severity. Cell 183, 996–1012.e1019 (2020).

Sattler, A. et al. SARS-CoV-2-specific T cell responses and correlations with COVID-19 patient predisposition. J. Clin. Invest 130, 6477–6489 (2020).

Rovito, R. et al. Hallmarks of Severe COVID-19 Pathogenesis: A Pas de Deux Between Viral and Host Factors. Front. Immunol. 13, 912336 (2022).

Paolini, A. et al. Patients Recovering from Severe COVID-19 Develop a Polyfunctional Antigen-Specific CD4+ T Cell Response. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 8004 (2022).

Su, Y. et al. Multi-Omics Resolves a Sharp Disease-State Shift between Mild and Moderate COVID-19. Cell 183, 1479–1495.e1420 (2020).

Solera, J. T. et al. Bivalent COVID-19 mRNA vaccine against omicron subvariants in immunocompromised patients. Lancet Infect. Dis. 23, e266–e267 (2023).

Goel, R. R. et al. Efficient recall of Omicron-reactive B cell memory after a third dose of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine. Cell 185, 1875–1887.e1878 (2022).

Muecksch, F. et al. Increased memory B cell potency and breadth after a SARS-CoV-2 mRNA boost. Nature 607, 128–134 (2022).

Pérez-Then, E. et al. Neutralizing antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 Delta and Omicron variants following heterologous CoronaVac plus BNT162b2 booster vaccination. Nat. Med. 28, 481–485 (2022).

Ron, R. et al. CD4/CD8 ratio and CD8+ T-cell count as prognostic markers for non-AIDS mortality in people living with HIV. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Immunol. 15, 1343124 (2024).

Kiazyk, S. A. & Fowke, K. R. Loss of CD127 expression links immune activation and CD4(+) T cell loss in HIV infection. Trends Microbiol. 16, 567–573 (2008).

Bofill, M. et al. Increased numbers of primed activated CD8+CD38+CD45RO+ T cells predict the decline of CD4+ T cells in HIV-1-infected patients. AIDS 10, 827–834 (1996).

Avelino-Silva, V. I. et al. CD4/CD8 Ratio and KT Ratio Predict Yellow Fever Vaccine Immunogenicity in HIV-Infected Patients. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 10, e0005219 (2016).

Tian, Y. et al. Immune Response to Hepatitis B Virus Vaccine Among People Living With HIV: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Immunol. 12, 745541 (2021).

Posteraro, B. et al. The link between genetic variation and variability in vaccine responses: systematic review and meta-analyses. Vaccine 32, 1661–1669 (2014).

Haralambieva, I. H. et al. The genetic basis for interindividual immune response variation to measles vaccine: new understanding and new vaccine approaches. Expert Rev. Vaccines 12, 57–70 (2013).

Santos-Rebouças, C. B. et al. Immune response stability to the SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine booster is influenced by differential splicing of HLA genes. Sci. Rep. 14, 8982 (2024).

Bonifacius, A. et al. COVID-19 immune signatures reveal stable antiviral T cell function despite declining humoral responses. Immunity 54, 340–354.e346 (2021).

Goel, R. R. et al. mRNA vaccines induce durable immune memory to SARS-CoV-2 and variants of concern. Science 374, abm0829 (2021).

Zhang, Z. et al. Humoral and cellular immune memory to four COVID-19 vaccines. Cell 185, 2434–2451.e2417 (2022).

Agrati, C. et al. Persistent Spike-specific T cell immunity despite antibody reduction after 3 months from SARS-CoV-2 BNT162b2-mRNA vaccine. Sci. Rep. 12, 6687 (2022).

Lasrado, N. & Barouch, D. H. SARS-CoV-2 Hybrid Immunity: The Best of Both Worlds. J. Infect. Dis. 228, 1311–1313 (2023).

Bronder, S. et al. Potent induction of humoral and cellular immunity after bivalent BA.4/5 mRNA vaccination in dialysis patients. NPJ Vaccines 9, 25 (2024).

Chemaitelly, H. et al. Long-term COVID-19 booster effectiveness by infection history and clinical vulnerability and immune imprinting: a retrospective population-based cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 23, 816–827 (2023).

Chemaitelly, H. et al. History of primary-series and booster vaccination and protection against Omicron reinfection. Sci. Adv. 9, eadh0761 (2023).

Chemaitelly, H. et al. Immune Imprinting and Protection against Repeat Reinfection with SARS-CoV-2. N. Engl. J. Med. 387, 1716–1718 (2022).

Qassim, S. H. et al. Population immunity of natural infection, primary-series vaccination, and booster vaccination in Qatar during the COVID-19 pandemic: an observational study. EClinicalMedicine 62, 102102 (2023).

Gilbert, P. B. et al. A Covid-19 Milestone Attained - A Correlate of Protection for Vaccines. N. Engl. J. Med. 387, 2203–2206 (2022).

Feng, S. et al. Correlates of protection against symptomatic and asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Med. 27, 2032–2040 (2021).

Garcia-Beltran, W. F. et al. COVID-19-neutralizing antibodies predict disease severity and survival. Cell 184, 476–488.e411 (2021).

Cheng, M. Q., Li, R., Weng, Z. Y. & Song, G. Immunogenicity and effectiveness of COVID-19 booster vaccination among people living with HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Med. 10, 1275843 (2023).

Cherneha, M. et al. Immunogenicity of the Monovalent Omicron XBB.1.5-Adapted BNT162b2 COVID-19 Vaccine in People Living with HIV (PLWH). Vaccines 12, 785 (2024).

Fabiani, M. et al. Relative effectiveness of bivalent Original/Omicron BA.4-5 mRNA vaccine in preventing severe COVID-19 in persons 60 years and above during SARS-CoV-2 Omicron XBB.1.5 and other XBB sublineages circulation, Italy, April to June 2023. Euro Surveill. 28, 2300397 (2023).

Tartof, S. Y. et al. Effectiveness of BNT162b2 BA.4/5 bivalent mRNA vaccine against a range of COVID-19 outcomes in a large health system in the USA: a test-negative case-control study. Lancet Respir. Med. 11, 1089–1100 (2023).

Fang, Z. et al. Omicron-specific mRNA vaccination alone and as a heterologous booster against SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Commun. 13, 3250 (2022).

Corbett, K. S. et al. SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine design enabled by prototype pathogen preparedness. Nature 586, 567–571 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the individuals enrolled in this study who agreed to participate to this research. Our special thanks also go to all the physicians and nurses at the Clinic of Infectious Diseases and Tropical Medicine at San Paolo Hospital in Milan who continuously helped in patients’ care, as well as laboratory personnel whose role in the conduct of the study was crucial. We also acknowledge the VaxICONA-ORCHESTRA Study Group, whose individual members are reported in the Supplementary Information, for the contribution to the participants’ enrollment. This study was presented in part at CROI 2024, 3–6 March 2024, Denver (Colorado, USA) – abstract #388, and awarded as Best Basic Science Abstract at the ICAR-CROI Awards 2024 (CROI Affiliated Event for Italian Young Investigators). This study was supported by funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program under grant agreement no. 101016167 within the ORCHESTRA project (Connecting European Cohorts to Increase Common and Effective Response to SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic), and grant agreement no. 101046016 within the EuCARE project (European Cohorts of Patients and Schools to Advance Response to Epidemics).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

M.A. designed the study, enrolled participants, collected clinical data, designed the experimental plan and performed the experiments, analyzed and interpreted the data, designed the figures, and wrote the manuscript. V.B. and R.R. performed part of the experiments and interpreted the data. G.S. and S.P. contributed to healthcare workers enrollment. A.T. and C.T. contributed to data interpretation and critical revision of the manuscript. A.V., A.M.A., E.R., S.M., S.N., F.M., A.A., E.T., A.S. and A.d’A.M. contributed to critical revision of the manuscript. G.M. conceived and designed the study, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Medicine thanks Ester Ballana and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Augello, M., Bono, V., Rovito, R. et al. Long-term immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.4/5 mRNA booster in people living with HIV. Commun Med 5, 92 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-00799-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-00799-6