Abstract

Background

Sleep health comprises several dimensions such as sleep duration and fragmentation, circadian activity, and daytime behavior. Yet, most research has focused on individual sleep characteristics. Studies are needed to identify sleep/circadian profiles incorporating multiple dimensions and to assess their associations with adverse health outcomes.

Methods

This multicenter population-based cohort study identified 24 h actigraphy-based sleep/circadian profiles in 2667 men aged ≥65 years using an unsupervised machine learning approach and investigated their associations with dementia and cardiovascular disease (CVD) incidence over 12 years.

Results

We identify three distinct profiles: active healthy sleepers (AHS; 64.0%), fragmented poor sleepers (FPS; 14.1%), and long and frequent nappers (LFN; 21.9%). Over the follow-up, compared to AHS, FPS exhibit increased risks of dementia and CVD events (HR = 1.35, 95% CI = 1.02-1.78 and HR = 1.32, 95% CI = 1.08-1.60, respectively) after multivariable adjustment, whereas LFN show a marginal association with increased CVD events risk (HR = 1.16, 95% CI = 0.98-1.37) but not with dementia (HR = 1.09, 95%CI = 0.86-1.38).

Conclusions

These results highlight potential targets for sleep interventions and the need for more comprehensive screening of poor sleepers for adverse outcomes.

Plain language summary

Although sleep health encompasses multiple dimensions, most research has evaluated these features in isolation. We aimed to identify multidimensional sleep/circadian profiles and to examine their associations with the incidence of adverse health outcomes. Using wearable device activity data from a prospective cohort of older men, we identified three profiles: active healthy sleepers (AHS), fragmented poor sleepers (FPS), and long and frequent nappers (LFN). Compared to AHS, FPS had increased risks of developing dementia and cardiovascular disease (CVD) events over 12 years whereas LFN tended to have an increased risk of CVD events only. These results suggest potential targets for sleep interventions and underscore the critical need for comprehensive sleep health assessment in clinical practice and research settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Growing evidence has linked individual sleep characteristics and disturbed circadian rhythms with adverse health outcomes in older adults, including neurodegenerative and cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), two leading causes of disability and mortality worldwide1,2,3,4. However, the literature remains inconsistent5,6,7,8. Some studies have associated both short and long sleep duration with increased dementia risk9, while others found conflicting associations7,10,11. Similarly, although some research has suggested that more frequent or long naps were associated with a higher risk of CVD4,12, others showed a protective effect13.

These conflicting findings may be partly due to the lack of consideration of the multidimensional nature of sleep. Research has primarily examined sleep characteristics in isolation, whereas sleep involves a complex interplay of multiple dimensions such as duration, continuity, quality, circadian rhythmicity, and napping14. Adopting a holistic approach by considering common combinations of sleep characteristics could improve our understanding of multidimensional sleep patterns and their associations with outcomes. Moreover, such approach offers key methodological advantages over analyzing sleep characteristics in isolation, such as capturing interactions between multiple sleep dimensions and improving differentiation of outcome risks by leveraging more homogenous groups. Therefore, investigating these associations can provide valuable insights for public health strategies, aiding the identification of at-risk populations and targeted treatments or interventions.

In a community-dwelling cohort of older men, our objectives were: (1) to identify actigraphy-derived sleep health profiles based on multidimensional objective sleep and rest-activity variables, by using a novel and flexible clustering method; and (2) to investigate the longitudinal associations between these profiles and the incidence of dementia and CVD events over 12 years.

We identify three common sleep/circadian profiles: active healthy sleepers (AHS), fragmented poor sleepers (FPS), and long and frequent nappers (LFN). Compared to AHS, FPS exhibit higher risks of developing dementia and CVD over 12 years whereas LFN show a marginal association with CVD. These findings highlight potential targets for sleep interventions and the need for more comprehensive screening of poor sleep health for adverse outcomes.

Methods

We followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines.

Study design

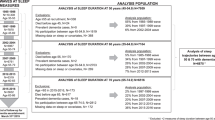

From 2000 to 2002, the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study (MrOS) enrolled 5994 community-dwelling men aged ≥65 years, able to walk without assistance, and without bilateral hip replacements, at six clinical centers across the United States15,16. Among them, 3135 were recruited into the ancillary MrOS sleep study and underwent a comprehensive sleep assessment between 2003 and 2005 (our study baseline). Men were screened for use of mechanical devices, including pressure masks for sleep apnea (positive airway pressure or oral appliance devices), or nocturnal oxygen therapy, and were excluded if they reported nightly use of any of these devices (except for intermittent users, n = 49). We excluded 331 men with missing actigraphy data or with fewer than 3 days or fewer than 3 nights of actigraphy data, and 137 with significant cognitive impairment at baseline (Modified Mini-Mental State Examination (3MS) score <80 or taking dementia medication), leading to a sample of 2667 participants (Supplementary Fig. 1). All participants provided written informed consent and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at each site. Our analytic study was approved by University of California San Francisco IRB.

Actigraphy

Participants wore a SleepWatch-O actigraph (Ambulatory Monitoring, Inc.) continuously on their nondominant wrist for ≥4 consecutive 24 h periods. Data were collected in proportional integration mode and scored by epoch to estimate wake and sleep periods using Action W-2 software and the University of California, San Diego scoring algorithm17. Trained scorers at the San Francisco Coordinating Center edited the data using participants’ sleep diaries to identify time in and out of bed as well as periods when the interval should be deleted because the watch was removed. Sleep indices were summarized across the monitoring period using means and standard deviations (SDs)18,19. Circadian rest-activity rhythm indices were generated using parametric extended cosine models and nonparametric variables20,21. A total of 37 actigraphy variables were examined and described in Table 1. There was a median of 5 (range 3–13) nights of actigraphy.

Dementia incidence

Over 12 years, participants attended four follow-up visits where they reported any physician-diagnosed dementia and their medication use, bringing all medications taken within the past 30 days. Dementia medication use was categorized based on the Iowa Drug Information Service Drug Vocabulary22. In addition, trained staff administered the 3MS test to assess global cognitive function. Similarly to previous studies5,23, incident dementia at any follow-up visit was defined by meeting at least one of the following criteria: (i) self-reported physician-diagnosed dementia; (ii) dementia medication use (verified by clinic staff based on examination of pill bottles); or (iii) a change in 3MS score of ≥1.5 SDs worse than the mean change from baseline to any follow-up visit. Participants were censored at the date of the diagnostic visit, death, or last visit.

Cardiovascular disease event incidence

Participants were surveyed for incident CVD events by postcard and phone contact every 4 months for ~12 years, with a response rate over 99%. Relevant medical records and documentation (e.g., laboratory results, diagnostic studies, notes, and discharge summaries) from any potential incident clinical events were obtained by the clinical center. For fatal events, the death certificate and hospital records from the time of death were collected. For fatal events that were not hospitalized, a proxy interview with next of kin and hospital records from the most recent hospitalization in the last 12 months were obtained. These documents were used to determine the underlying cause of death. For both nonfatal and fatal CVD events, all documents were adjudicated by a board-certified cardiologist using a prespecified adjudication protocol. Inter-rater agreement was periodically evaluated by one or more expert adjudicator(s) in a random subset of events to ensure quality control. Confirmed cardiovascular events were grouped as follows: 1) Coronary heart disease event: acute myocardial infarction (ST or non-ST elevation), sudden coronary heart disease death, coronary artery bypass surgery, mechanical coronary revascularization, hospitalization for unstable angina, ischemic congestive heart failure, or other coronary heart disease event not described above; 2) Cerebrovascular event: stroke or transient ischemic attack; 3) Peripheral vascular disease event: acute arterial occlusion, rupture, dissection, or vascular surgery; and 4) All-cause cardiovascular disease event: combines coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular event, and peripheral vascular disease. Participants were censored at the date of the first CVD event, death, last contact before March 1, 2015, or on March 1, 2015.

Covariate data

All participants completed questionnaires at baseline, which included items about demographics, living alone, smoking status, caffeine intake (mg/day), and alcohol use (>1 alcoholic drink/week). Level of physical activity was assessed using the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly24. Participants also self-reported their medical history, specifically prior physician diagnosis of heart attack, stroke, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension. The Geriatric Depression Scale was used to assess depressive symptoms, with higher scores corresponding to higher levels of depression25. Participants were asked to bring in all medications used within the preceding 30 days. All prescription and nonprescription medications were entered into an electronic database and each medication was matched to its ingredient(s) based on the Iowa Drug Information Service Drug Vocabulary (College of Pharmacy, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA)22. The use of antidepressants, benzodiazepines, and other sleep medications (non-benzodiazepines, non-barbiturate sedative hypnotics) were categorized. A comprehensive examination included measurements of body weight and height. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters. A subset of participants underwent a single-night in-home polysomnography (Compumedics, Safiro, Inc., Melbourne, Australia)26. The apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) was calculated as the total number of apneas and hypopneas per hour of sleep (accompanied by a ≥ 3% oxygen desaturation).

Statistics and reproducibility

We conducted a cluster analysis to identify distinct sleep/circadian profiles. Firstly, we selected variables for inclusion in the analysis, considering the high correlation among the actigraphy variables (Supplementary Fig. 2). When the correlation coefficient between two variables was >0.70, we retained only one of the variables prioritized on clinical meaningfulness, resulting in a final selection of 20 sleep/circadian variables. Secondly, we performed a principal component analysis (PCA) on the 20 selected variables to reduce data dimensionality (while preserving most of the data variation) and enhance the efficacy of subsequent clustering. The 20 variables included in the PCA for cluster creation are highlighted in Table 1. The number of principal components (PCs) was determined according to the Kaiser-Guttman criteria27, considering PCs with eigenvalues > 1, and complemented by visual inspection of the scree plot to identify the elbow point in the eigenvalues distribution (Supplementary Fig. 3)28. Thirdly, sleep/circadian profiles were identified using Multiple Coalesced Generalized Hyperbolic Distribution (MCGHD; MixGHD package in R) mixture models based on the six PCs derived from the PCA29,30. This method, as opposed to standard clustering approaches, was chosen for its ability to accommodate potentially skewed and/or asymmetric clusters, an important consideration given the skewed distributions often observed in actigraphy data (distributions are described in Supplementary Fig. 4). We explored models comprising one to five clusters, using k-medoids as the starting criterion, and determined the optimal number of clusters by examining the Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC), the Akaike Information Criteria (AIC) and the Integrated Complete-data Likelihood (ICL) (higher values indicating a better fit for the data). The optimal number of clusters was determined by selecting solutions displaying an elbow in the AIC and BIC plots and/or a subsequent drop in ICL. To assess the stability of the clustering solution, we applied a subsampling approach in which 5% of participants were randomly excluded, and the clustering algorithm was rerun on each subsample (n = 100). The similarity between each subsample clustering and the original full-sample clustering was quantified using the Adjusted Rand Index (ARI), which ranges from −1 (less agreement than expected by chance between two clusterings) to 1 (perfect agreement) with 0 indicating random agreement.

Sleep and circadian characteristics were compared across clusters using the Kruskal-Wallis test. We calculated effect sizes using the eta-squared (η2) statistic to characterize the magnitude of cluster differences. The effect was considered small for η2 < 0.06, moderate for 0.06 ≤ η2 < 0.14, and large for η2 ≥ 0.1431. In post-hoc analyses, we performed multiple pairwise-comparisons using Dunn’s test adjusted for multiple comparisons with the Bonferroni correction. The sleep and circadian characteristics with the largest effect sizes were presented in radial plots for each sleep profile (Fig. 1). In a sensitivity analysis, clusters were re-determined after excluding participants who intermittently used nightly mechanical devices during sleep (n = 37) to assess their influence of the clustering results.

Panels (a−c) display radial plots for the profiles of active healthy sleepers, fragmented poor sleepers, and long and frequent nappers, respectively. The values represent the median quantile rank of each characteristic within the sample, grouped by profile. The sample’s highest ranked value is represented by the maximum value of 1, the median ranked value by 0.50, and the lowest ranked value by 0. These values illustrate the relative central distributions across each sleep profile. The sample size was n = 2667. Abbreviations: WASO wake after sleep onset

We performed unadjusted and multivariable adjusted Cox proportional hazards models with age as time scale to investigate whether identified sleep profiles were associated with the incidence of dementia and CVD events over 12 years. Covariates were selected based on potential biological plausibility, and included study site, race/ethnicity, education, smoking status, caffeine intake, alcohol use, physical activity, BMI, history of diabetes mellitus and hypertension, depressive symptoms, and sleep-related medications use. We assessed the proportional hazard assumption for each independent variable by examining the Schoenfeld residuals. If a variable violated the assumption, we carried out a stratified Cox regression model for that specific variable.

In sensitivity analyses, models were further adjusted for (i) history of heart attack and stroke, (ii) baseline AHI, (iii) living alone, and (iv) baseline 3MS score (for dementia analysis). We also excluded participants with incident dementia at the first follow-up visit to minimize reverse causation (for dementia analysis), and those with history of heart attack and stroke to minimize confounding bias (for CVD analysis).

Significance level was set at a two-sided p < 0.05 and statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.3.0.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

A total of 2667 men were eligible for cluster analysis. At baseline, participants had a median age of 75 years (interquartile range [IQR] = 72–80), 20.2% had a high school education or lower, and 90.0% were White. Compared to included participants, excluded men (n = 468) were older, less educated, more likely to be non-White and to live alone, and had less physical activity and alcohol consumption, but higher depressive symptoms and sleep medication use (Supplementary Table 1).

Sleep profiles

The PCA conducted on the 20 selected variables resulted in six PCs, collectively explaining 75.6% of the variance (Supplementary Fig. 3). The PCA loadings for each variable across PCs are presented in Supplementary Table 2. After examining the AIC, BIC, and ICL of the MGHD models, three distinct sleep/circadian profiles were identified (Supplementary Fig. 5): active healthy sleepers [AHS; n = 1,707 (64.0%)], fragmented poor sleepers [FPS; n = 376 (14.1%)], and long and frequent nappers [LFN; n = 584 (21.9%)]. The stability of the clustering results, as assessed by the ARI, indicated moderate to good quality (mean ARI = 0.58, median = 0.55, Q1 = 0.50, Q3 = 0.74). The three groups had a median of 5 nights of actigraphy (IQR = 5–5), and their ranges were as following: 3 to 11 for AHS, 4 to 13 for FPS, and 3 to 8 for LFN. All sleep characteristics are described in Table 2.

AHS were characterized by normal nighttime sleep duration (median = 6.7 h), higher sleep quality (median sleep efficiency = 83%, sleep maintenance = 87%, minimum = 234, L5 = 292), earlier timing of sleep (median sleep onset time = 23.1, start and midpoint of L5 = 0.23 and 2.73, midpoint of bed and onset interval = 2.79 and 2.92), stronger circadian rhythmicity (median amplitude = 3712, pseudo-F = 1078, intradaily variability = 0.60, interdaily stability = 0.76, relative amplitude = 0.86), and higher activity during wake periods (median M10 = 4049, alpha = −0.40) (description and interpretation of all sleep/circadian data are described in Table 1).

FPS were characterized by shorter nighttime sleep duration (median = 5.6 h) and longer time in bed (median= 8.8 h), lower sleep quality (median sleep efficiency= 64%, sleep maintenance = 71), higher sleep fragmentation (median sleep latency = 53 min, wake after sleep onset= 126 min, L5 = 525, and median SD for sleep onset = 1.14, bedtime= 0.68, wake-up time = 0.72, midpoint of bed and onset interval = 0.58 and 0.75), later timing of sleep and activity (median acrophase = 14.69, wake-up time = 7.5, start of M10 = 8.7, up-mesor = 7.4, sleep onset time = 23.7, midpoint of onset interval = 3.48), and weaker circadian rhythmicity (median amplitude = 3294, relative amplitude = 0.77).

LFN were characterized by longer (median = 79 min) and more frequent naps (median = 5.5), normal nighttime sleep duration (median = 6.4 h), good sleep quality (median sleep efficiency = 82%, sleep maintenance = 85%), earlier timing of activity (median acrophase = 13.51, start and midpoint of M10 = 7.6 and 12.6, down-mesor = 19.9), and more fragmented circadian rhythmicity (median pseudo-F = 805, intradaily variability = 0.70, interdaily stability = 0.73, amplitude = 3250).

All sleep and circadian variables differed significantly across the three profiles (p < 0.0001). Among the cluster analysis variables, large effect sizes were found for the following (ordered by descending order of contribution): alpha (η2 = 0.213), minimum (η2 = 0.193), wake after sleep onset (η2 = 0.188), minutes napping (η2 = 0.160), and sleep latency (η2 = 0.157). Other variables with large effect sizes included sleep efficiency, down-mesor, sleep maintenance, relative amplitude, number of naps, and L5 (Table 2). Sleep profiles based on the largest contributors were illustrated in Fig. 1.

Compared to AHS, FPS were more likely to live alone, to be less educated and less physically active, while LFN were slightly older. Both FPS and LFN were more likely to be non-White, smokers, to have a history of hypertension and a higher BMI. AHS consumed less caffeine than FPS (Table 3).

Exclusions of participants who intermittently used nightly mechanical devices during sleep (n = 37) showed similar sleep/circadian profiles (Supplementary Table 3).

Dementia incidence

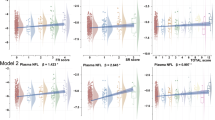

Among the 2562 men with dementia data, 461 (18.0%) incident dementia cases were identified (annual incidence rate = 27.6/1000 person-years) over 12 years of follow-up (median = 6.1 [IQR = 3.2-10.5]). Kaplan–Meier curves are shown in Fig. 2. In unadjusted models, FPS had an increased risk of dementia (hazard ratios (HR) = 1.34, 95% confidence intervals (CI) = 1.03-1.74) compared to AHS. There was no association with dementia risk for LFN (HR = 1.11, 95% CI = 0.89-1.39). After adjusting for demographics, behaviors, comorbidities and sleep medication use, results were similar (HR = 1.35, 95% CI = 1.02–1.78 for FPS and HR = 1.09, 95% CI = 0.86–1.38 for LFN). Sensitivity analyses adjusting for different set of covariates displayed comparable findings (Supplementary Tables 4–7) as well as the exclusion of incident dementia cases identified at the first follow-up visit (HR = 1.42, 95% CI = 1.01–1.98 for FPS and HR = 1.20, 95% CI = 0.90-1.61 for LFN; Supplementary Table 8).

P-values are derived from Wald tests based on unadjusted Cox proportional hazards models, using the Active healthy sleepers profile as the reference group. a, b correspond to Kaplan–Meier plots for dementia incidence and cardiovascular disease events incidence, respectively. Green, blue, and yellow lines correspond to Active healthy sleepers, Fragmented poor sleepers, and Long and frequent nappers profiles, respectively. The sample size was n = 2562 for dementia outcome and n = 2606 for cardiovascular disease outcome. Abbreviations: CVD cardiovascular disease, No. number

CVD event incidence

Among 2606 men with CVD data, 839 (32.2%) incident CVD events were identified (annual incidence rate = 42.4/1000 person-years) over 12 years of follow-up (median = 9.7 [IQR = 4.5-10.5]). Kaplan–Meier curves are shown in Fig. 2. In unadjusted models, both FPS and LFN were significantly associated with a higher risk of CVD events compared to AHS (HR = 1.44, 95% CI = 1.19–1.74 and HR = 1.21, 95% CI = 1.02–1.42, respectively). After multivariable adjustment, FPS were significantly associated with a higher risk of CVD events compared to AHS (HR = 1.32, 95% CI = 1.08-1.60), while LFN showed a borderline association (HR = 1.16, 95% CI = 0.98-1.37, p = 0.08). Results remained consistent in the sensitivity analysis after further adjustment (Supplementary Tables 4–6 and 9), although the association for LFN was strongly attenuated after exclusion of participants with a history of heart attack or stroke (HR = 1.07, 95% CI = 0.87-1.31; Supplementary Table 9).

Discussion

In a prospective cohort of older men, we identified three distinct multidimensional sleep/circadian profiles using machine learning: active healthy sleepers [AHS], fragmented poor sleepers [FPS], and long and frequent nappers [LFN]. Compared to AHS, FPS had increased risks of developing dementia and CVD events over 12 years whereas LFN tended to have an increased risk of CVD events, but not dementia. These results suggest that poor sleep and disrupted circadian rhythms may be risk factors or preclinical markers of dementia and CVD and highlight potential target populations for sleep interventions.

Few studies have used clustering32,33,34 or latent class35,36,37 analyses to discern sleep profiles in older adults. Moreover, these studies faced important limitations, including cross-sectional design32, reliance on self-reported sleep data32,35,36, lack of rest-activity variables32,34,35,36, and a focus on clinical populations34. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to identify objective sleep and circadian profiles in community-dwelling older men using both sleep and rest-activity parameters with prospective follow-up for health outcomes. We identified three sleep profiles with high heterogeneity, as evidence by the wide range of values and the significant differences in all actigraphy-derived variables across the groups (p < 0.0001 for all). The AHS group was the most common profile (64%), characterized by a combination of favorable characteristics: normal nighttime sleep duration, higher sleep quality, and stronger circadian rhythmicity. The LFN (21.9%) were characterized by longer and more frequent naps, alongside a combination of favorable and unfavorable dimensions: normal nighttime sleep duration, good sleep quality, and more fragmented circadian rhythms. The third group was the FPS (14.1%) who had a combination of unfavorable characteristics: shorter nighttime sleep duration, lower sleep quality, higher sleep fragmentation, delayed sleep/activity timing, and weaker circadian rhythmicity. Although each cluster is characterized by distinct main features, it is important to acknowledge that some overlap exists between the profiles. For instance, LFN’s nighttime sleep efficiency and duration are comparable to those of AHS, suggesting shared good sleep quality between AHS and LFN, while FPS and LFN exhibit similar levels of circadian rhythmicity. This overlap indicates that the clusters represent a continuum of sleep and circadian behaviors, highlighting the complexity of sleep health. Compared to prior research, our study provides a deeper characterization of nighttime and daytime sleep patterns by using a broader set of objective parameters, including extensive analysis of circadian rhythms. This provided a more nuanced and complete understanding of participants’ multidimensional sleep and circadian patterns. Additionally, the advanced machine learning technique has further enhanced classification accuracy.

Compared to AHS, FPS had a higher risk of dementia, consistent with variable-centered research linking short sleep duration, sleep fragmentation, poor sleep efficiency, and weak circadian rhythms with dementia incidence2,6,38,39,40. This result is also in line with our previous work demonstrating the association between a multidimensional measure of sleep health and long-term cognitive decline41. Our result extends those of a recent cross-sectional, person-centered study that used self-reported sleep, which found that the poor sleepers group performed worse on several cognitive tests compared to the healthy sleepers group32. Potential underlying mechanisms include accumulation of amyloid-beta and tau proteins, disturbed glymphatic clearance, metabolic dysfunction, inflammation, and disrupted 24-h melatonin rhythms42,43,44,45. Given melatonin’s neuroprotective effects -such as reducing amyloid-beta production, mitigating tau hyperphosphorylation, alleviating oxidative stress, and enhancing blood-brain barrier function- its dysregulation may further link poor sleep health to increased dementia risk45. However, we cannot exclude the fact that preclinical dementia-related changes may also influence sleep and circadian patterns46,47,48. FPS also had an increased risk of CVD events, in line with several prior studies of individual sleep parameters49,50,51. Increase sympathetic activity and blood pressure, disrupted endothelial function, and inflammatory processes may explain in part this association52. Interestingly, AHI differed across the three groups, with the FPS group exhibiting the highest median AHI (Table 3). Adjusting for baseline AHI slightly attenuated the association between FPS and dementia risk (Supplementary Table 5), but the effect size and confidence intervals remained largely unchanged. This suggests that sleep apnea may partially mediate this relationship whereas the association between FPS and CVD remained robust after adjusting for AHI, highlighting the importance of other mechanisms. Taken together, these results showed that FPS were associated with poor incident cognitive and cardiovascular health.

We did not observe an association between LFN and dementia incidence. This finding contributes to the ongoing debate on napping and dementia. Some studies have reported that longer or more frequent naps were linked to a higher risk of dementia and faster cognitive decline5,53, while others have found a lower risk54,55 or no association7,56. Our study demonstrated that long and frequent napping, when combined with good nighttime sleep dimensions, might not affect the risk of dementia. This underscores the importance of clustering analysis and considering combination of sleep and circadian dimensions, as longer and more frequent naps alone were associated with a higher risk of dementia in our sample. Furthermore, this is in line with a previous clustering study which showed that a high sleep propensity group (characterized by long naps) was protective against all-cause mortality, while napping alone was associated with a higher risk33. Interestingly, LFN were linked to increased risk of CVD events, although the association was of marginal significance. Prior research on napping and CVD has been mixed, with several studies suggesting a higher risk of CVD associated with more frequent or longer naps4,12, while others suggested a protective effect13. Daytime napping may result from short or poor nighttime sleep (as a compensatory mechanism) or indicate poor overall health, both of which can contribute to increase CVD risk. However, these hypotheses do not fully explain our findings since LFN had normal nighttime sleep duration with good sleep quality, and LFN did not differ from AHS regarding sociodemographic factors and comorbidities. Although the exact reasons why LFN might be associated with CVD but not dementia are not well-understood, assumptions include autonomic nervous system disruptions or other metabolic changes not examined in this study57,58, which may impact more the cardiovascular risk. It may also involve cardiovascular mechanisms that do not relate to dementia risk or have a less direct effect on it. Further research, including mediation analyses, is needed to better understand the role of napping in relation to adverse health outcomes and their underlying mechanisms.

Our findings have important clinical and public health implications. By identifying common multidimensional sleep and circadian patterns in older men using advanced machine learning techniques, this study enhances our understanding of the interrelations between numerous sleep/circadian parameters and underscores the critical need for comprehensive sleep health assessment in clinical practice and research settings. Both FPS and LFN exhibited poor circadian activity rhythmicity, emphasizing the importance of this dimension of sleep health. Future studies should incorporate circadian rhythms when examining adverse outcomes. Moreover, our results highlight specific at-risk groups that could benefit from sleep interventions and prevention efforts, and support poor sleep patterns as a marker or risk factor for cognitive and cardiovascular health. Public health initiatives may consider prioritizing the screening and monitoring of older adults with weak circadian rhythms combined with poor nighttime sleep or with high daytime napping.

Strengths of this study include a 12 year longitudinal design with high retention rates, a multidimensional measure of sleep and rest-activity rhythms using objective measures, and consideration of numerous potential confounders. We also used an innovative machine learning approach capable of detecting clusters with flexible shapes, which standard clustering methods cannot achieve. However, there are also limitations. Although we applied a prespecified algorithm previously used in MrOS studies5,23, which aligns with approaches from other cohort studies11,59, the diagnosis of dementia relied on both objective (e.g., dementia medication, cognitive tests) and self-reported data (e.g., self-reported physician diagnosis), which may lead to outcome misclassification. Moreover, the timing of dementia incidence was based on study visit dates, which may not reflect the actual onset of dementia, and information on dementia subtypes was lacking. Due to the lack of biomarkers of neurodegeneration in this study, we were unable to determine whether specific sleep profiles are associated with distinct neurodegenerative pathways. Future research should incorporate objective biomarkers, such as phosphorylated tau (p-tau)217, p-tau181, or white matter hyperintensities, to better understand their relationship with sleep profiles. CVD events assessment relied in part on self-report potentially introducing bias, but this approach was completed with rigorous, objective assessments and expert confirmation, making it a well-established and widely accepted method in the literature60,61. Additionally, actigraphy data were available only at baseline, with a median duration of 5 nights. Future research should use longer actigraphy recordings to more robustly assess circadian rhythmicity and examine changes in sleep over time to identify dynamic profiles and minimize potential bias due to single-time-point assessments. This study predominantly involves White older men, limiting the generalizability of the results. Future research should replicate these methods in more diverse samples. Lastly, as an observational study, we cannot assume causal relationships between sleep profiles and dementia or CVD events.

Conclusions

In older men, we identified three multidimensional actigraphy-derived sleep/circadian profiles. Compared to AHS, FPS were associated with less favorable cognitive and cardiovascular health over 12 years, while FPS were linked to increased risk of CVD events, but not dementia. These results suggest potential targets for sleep interventions and prevention efforts and emphasize the need for careful screening of poor sleepers for adverse outcomes. Moreover, our study highlights the importance of future research to consider combinations of sleep characteristics.

Code availability

Code for identification of clusters is accessible at https://zenodo.org/records/1579252162.

References

Xu, W., Tan, C. C., Zou, J. J., Cao, X. P. & Tan, L. Sleep problems and risk of all-cause cognitive decline or dementia: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 91, 236–244 (2020).

Winer, J. R. et al. Impaired 24-h activity patterns are associated with an increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and cognitive decline. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 16, 35 (2024).

Cappuccio, F. P., Cooper, D., D’Elia, L., Strazzullo, P. & Miller, M. A. Sleep duration predicts cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur. Heart J. 32, 1484–1492 (2011).

Yamada, T., Hara, K., Shojima, N., Yamauchi, T. & Kadowaki, T. Daytime napping and the risk of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality: a prospective study and dose-response meta-analysis. Sleep 38, 1945–1953 (2015).

Leng, Y., Redline, S., Stone, K. L., Ancoli-Israel, S. & Yaffe, K. Objective napping, cognitive decline, and risk of cognitive impairment in older men. Alzheimers Dement. 15, 1039–1047 (2019).

Lysen, T. S., Luik, A. I., Ikram, M. K., Tiemeier, H. & Ikram, M. A. Actigraphy-estimated sleep and 24 hour activity rhythms and the risk of dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 16, 1259–1267 (2020).

Cavaillès, C. et al. Trajectories of sleep duration and timing before dementia: a 14 year follow-up study. Age Ageing 51, afac186 (2022).

Wang, S. et al. Associations between sleep duration and cardiovascular diseases: a meta-review and meta-analysis of observational and Mendelian randomization studies. Front Cardiovasc Med. 9, 930000 (2022).

Ohara, T. et al. Association between daily sleep duration and risk of dementia and mortality in a japanese community. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 66, 1911–1918 (2018).

Lutsey, P. L. et al. Sleep characteristics and risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Alzheimers Dement. 14, 157–166 (2018).

Diem, S. J. et al. Measures of sleep-wake patterns and risk of mild cognitive impairment or dementia in older women. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 24, 248–258 (2016).

Li, P. et al. Objective assessment of daytime napping and incident heart failure in 1140 community-dwelling older adults: a prospective, observational cohort study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 10, e019037 (2021).

Häusler, N., Haba-Rubio, J., Heinzer, R. & Marques-Vidal, P. Association of napping with incident cardiovascular events in a prospective cohort study. Heart 105, 1793–1798 (2019).

Buysse, D. J. Sleep health: can we define it? does it matter?. Sleep 37, 9–17 (2014).

Orwoll, E. et al. Design and baseline characteristics of the osteoporotic fractures in men (MrOS) study — a large observational study of the determinants of fracture in older men. Contemp. Clin. Trials 26, 569–585 (2005).

Blank, J. B. et al. Overview of recruitment for the osteoporotic fractures in men study (MrOS). Contemp. Clin. Trials 26, 557–568 (2005).

Kripke, G. irardinJ., Mason, D. F., Elliott, W. J. & Youngstedt, J. A. SD. Sleep estimation from wrist movement quantified by different actigraphic modalities. J. Neurosci. Methods 105, 185–191 (2001).

Blackwell, T., Ancoli-Israel, S. & Redline, S. Stone KL, Osteoporotic fractures in men (MrOS) study group. factors that may influence the classification of sleep-wake by wrist actigraphy: the MrOS sleep study. J. Clin. Sleep. Med. 7, 357–367 (2011).

Wallace, M. L. et al. Multidimensional sleep and mortality in older adults: a machine-learning comparison with other risk factors. J. Gerontol. A. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 74, 1903–1909 (2019).

Marler, M. R., Gehrman, P., Martin, J. L. & Ancoli-Israel, S. The sigmoidally transformed cosine curve: a mathematical model for circadian rhythms with symmetric non-sinusoidal shapes. Stat. Med. 25, 3893–3904 (2006).

Van Someren, E. J. et al. Bright light therapy: improved sensitivity to its effects on rest-activity rhythms in Alzheimer patients by application of nonparametric methods. Chronobiol. Int. 16, 505–518 (1999).

Pahor, M. et al. Drug data coding and analysis in epidemiologic studies. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 10, 405–411 (1994).

Xiao, Q. et al. Nonparametric parameters of 24 hour rest–activity rhythms and long-term cognitive decline and incident cognitive impairment in older men. 77, 250–258 (2021).

Washburn, R. A., Smith, K. W., Jette, A. M. & Janney, C. A. The physical activity scale for the elderly (PASE): development and evaluation. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 46, 153–162 (1993).

Sheikh, J. & Yesavage, J. Geriatric depression scale: recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin. Gerontol. 5, 165–173 (1986).

Song, Y. et al. Relationships between sleep stages and changes in cognitive function in older men: the MrOS sleep study. Sleep 38, 411–421 (2015).

Guttman, L. Some necessary conditions for common-factor analysis. Psychometrika 19, 149–161 (1954).

Jolliffe I. T. Principal component analysis for special types of data. In Principal Component Analysis (ed. Jaadi, Z.) 338–372 (Springer, 2002).

Tortora, C., Franczak, B. C., Browne, R. P. & McNicholas, P. D. A mixture of coalesced generalized hyperbolic distributions. J. Classif. 36, 26–57 (2019).

Tortora, C., Browne, R. P., ElSherbiny, A., Franczak, B. C. & McNicholas, P. D. Model-based clustering, classification, and discriminant analysis using the generalized hyperbolic distribution: MixGHD R package. J. Stat. Softw. 98, 1–24 (2021).

Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral SciencesSubsequent edition, Vol. 590 (Routledge Academic, 1988).

Du, L. et al. Associations between self-reported sleep patterns and health, cognition and amyloid measures: results from the wisconsin registry for Alzheimer’s prevention. Brain Commun. 5, fcad039 (2023).

Wallace, M. L. et al. Actigraphy-derived sleep health profiles and mortality in older men and women. Sleep 45, zsac015 (2022).

Targa, A. D. S. et al. Sleep profile predicts the cognitive decline of mild-moderate Alzheimer’s disease patients. Sleep 44, zsab117 (2021).

Leigh, L., Hudson, I. L. & Byles, J. E. Sleeping difficulty, disease and mortality in older women: a latent class analysis and distal survival analysis. J. Sleep. Res. 24, 648–657 (2015).

Yu, J., Mahendran, R., Abdullah, F. N. M., Kua, E. H. & Feng, L. Self-reported sleep problems among the elderly: a latent class analysis. Psychiatry Res. 258, 415–420 (2017).

Smagula, S. F. et al. Latent activity rhythm disturbance sub-groups and longitudinal change in depression symptoms among older men. Chronobiol. Int. 32, 1427–1437 (2015).

Sabia, S. et al. Association of sleep duration in middle and old age with incidence of dementia. Nat. Commun. 12, 2289 (2021).

Lim, A. S. P., Kowgier, M., Yu, L., Buchman, A. S. & Bennett, D. A. Sleep fragmentation and the risk of incident Alzheimer’s disease and cognitive decline in older persons. Sleep 36, 1027–1032 (2013).

Tranah, G. J. et al. Circadian activity rhythms and risk of incident dementia and mild cognitive impairment in older women. Ann. Neurol. 70, 722–732 (2011).

Cavaillès, C. et al. Multidimensional sleep health and long-term cognitive decline in community-dwelling older men. J. Alzheimers Dis. 96, 65−71 (2023).

Xie, L. et al. Sleep drives metabolite clearance from the adult brain. Science 342, 373–377 (2013).

Lucey, B. P. It’s complicated: the relationship between sleep and Alzheimer’s disease in humans. Neurobiol. Dis. 144, 105031 (2020).

Yaffe, K., Falvey, C. M. & Hoang, T. Connections between sleep and cognition in older adults. Lancet Neurol. 13, 1017–1028 (2014).

Zhang, Z. et al. Melatonin: A potential nighttime guardian against Alzheimer’s. Mol. Psychiatry 30, 237–250 (2025).

Oh, J. et al. Profound degeneration of wake-promoting neurons in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 15, 1253–1263 (2019).

Theofilas, P. et al. Locus coeruleus volume and cell population changes during Alzheimer’s disease progression: a stereological study in human postmortem brains with potential implication for early-stage biomarker discovery. Alzheimers Dement. 13, 236–246 (2017).

Wang, J. L. et al. Suprachiasmatic neuron numbers and rest-activity circadian rhythms in older humans. Ann. Neurol. 78, 317–322 (2015).

Wang, Z. et al. Association of sleep duration, napping, and sleep patterns with risk of cardiovascular diseases: a nationwide twin study. J. Am. Heart Asso. 11, e025969 (2022).

Yan, B. et al. Objective sleep efficiency predicts cardiovascular disease in a community population: the sleep heart health study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 10, e016201 (2021).

Paudel, M. L. et al. Rest/activity rhythms and mortality rates in older men: MrOS sleep study. Chronobiol. Int. 27, 363–377 (2010).

Belloir, J., Makarem, N. & Shechter, A. Sleep and circadian disturbance in cardiovascular risk. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 24, 2097–2107 (2022).

Li, P. et al. Daytime napping and Alzheimer’s dementia: a potential bidirectional relationship. Alzheimers Dement. 19, 158–168 (2022).

Keage, H. A. D. et al. What sleep characteristics predict cognitive decline in the elderly?. Sleep. Med. 13, 886–892 (2012).

Anderson, E. L. et al. Is disrupted sleep a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease? evidence from a two-sample Mendelian randomization analysis. Int J. Epidemiol. 50, 817–828 (2021).

Wong, A. T. Y., Reeves, G. K., Floud, S. Total sleep duration and daytime napping in relation to dementia detection risk: results from the million women study. Alzheimers Dement. 19, 4978−4986 (2023).

Nakayama, N. et al. Napping improves HRV in older patients with cardiovascular risk factors. West J. Nurs. Res. 41, 1241–1253 (2019).

Ghazizadeh, H. et al. The association between daily naps and metabolic syndrome: evidence from a population-based study in the Middle-East. Sleep. Health 6, 684–689 (2020).

Deal, J. A. et al. Hearing impairment and incident dementia and cognitive decline in older adults: the health ABC study. 72, 703–709 (2017)

Collet, T. H. et al. Endogenous testosterone levels and the risk of incident cardiovascular events in elderly men: the mros prospective study. J. Endocr. Soc. 4, bvaa038 (2020).

Karlsen, H. R. et al. Anxiety as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease independent of depression: a prospective examination of community-dwelling men (The MrOS study). Psychol. Health 36, 148–163 (2021).

Cavaillès, C. et al. Zenodo code. Zenodo. https://zenodo.org/records/15792521 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the study staff and all the men who participated in MrOS Sleep Study. K.Y. is supported in part by (NIA) R35AG071916 and R01AG066137. Y.L. is supported by the NIA grants R21AG085495 and R01AG083836. The MrOS Study is supported by National Institutes of Health funding. The following institutes provided support: the National Institute on Aging (NIA), the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS), the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research under the following grant numbers: U01 AG027810, U01 AG042124, U01 AG042139, U01 AG042140, U01 AG042143, U01 AG042145, U01 AG042168, U01 AR066160, R01 AG066671, and UL1 TR002369). The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) provided funding for the MrOS Sleep ancillary study “Outcomes of Sleep Disorders in Older Men” under the following grant numbers: R01 HL071194, R01 HL070848, R01 HL070847, R01 HL070842, R01 HL070841, R01 HL070837, R01 HL070838, and R01 HL070839.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.C. contributed to the conception and design of the work, the analysis, the interpretation of data, and the draft of the manuscript. M.W. contributed the design of the work and the analysis. Y.L. contributed to the interpretation of the data and the revision of the manuscript. K.L.S. and S.A.I. contributed to the revision of the manuscript. K.Y. contributed to the design of the work, the acquisition and interpretation of data, and the revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Medicine thanks Ziliang Xu and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.[A peer review file is available.]

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cavaillès, C., Wallace, M., Leng, Y. et al. Multidimensional sleep profiles via machine learning and risk of dementia and cardiovascular disease. Commun Med 5, 306 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01019-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01019-x

This article is cited by

-

Circadian rhythm profiles derived from accelerometer measures of the sleep-wake cycle in two cohort studies

Nature Communications (2025)