Abstract

Background

Diabetic ketoacidosis is an acute, potentially life-threatening, metabolic complication and often first presentation of type 1 diabetes (T1D) mellitus. Here, we investigated the metabolic and lipid profiles from pediatric patients with T1D, at initial diagnosis and after two weeks of insulin treatment, employing findings from patients affected by maple syrup urine disease (MSUD) and the Recipient Epidemiology and Donor Evaluation Study (REDS) III RBC Omics.

Methods

27 patients with newly onset T1D were assessed at the University of Campania “L. Vanvitelli” at first diagnosis and 2 weeks after therapy with insulin. As part of the REDS-III RBC Omics, whole blood was collected from 13,091 healthy blood donors. Whole blood was also collected from 3 patients with MSUD by biallelic inactivating mutation of BCKDHA. Metabolomics and Lipidomics were performed via UHPLC-MS/MS.

Results

Our findings highlight a newly identified associations among short-chain hydroxyacyl-carnitines, ketoacidosis, and hematological alterations in T1D. An associative linkage with SNPs in the regions coding for branched chain ketoacid dehydrogenase A and B (BCDHKA/B) is noted by leveraging measurements of the same metabolites in over 13,000 healthy genetically characterized donor volunteers. MSUD, a rare genetic disorder characterized by inactivating mutations of the BCDHKA gene leading to inability to metabolize branched-chain amino acids, manifests a strong association between the branched-chain amino acid-derived ketoacids, associated acyl-carnitines, and acidosis.

Conclusions

These results indicate that T1D hematological alterations at onset might act as biomarkers linked to circulating levels of short-chain acyl-carnitines, providing risk stratification for T1D and potentially for MSUD. Carnitine metabolism may be a promising therapeutic target for both diseases.

Plain language summary

Type 1 diabetes (T1D) and maple syrup urine disease (MSUD) are rare conditions that lack reliable markers to predict how they will develop or how best to treat them. In our study, we looked at blood samples from 27 children newly diagnosed with T1D, 3 children with MSUD, and about 13,000 healthy people. We found certain changes in the blood that link the two diseases and show how these diseases affect the body. Some of these changes involve the metabolism of carnitine, a substance that helps the body use energy. Checking the way patients use carnitines may be useful for identifying patients at higher risk of being less sensitive to treatment and could serve as potential targets to improve treatment in both T1D and MSUD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1D) may present as an asymptomatic incidental finding, as new-onset classical diabetes symptoms (polydipsia, polyuria, hyperglycemia, and ketonuria), or as diabetic ketoacidosis. Although hyperglycemia without acidosis is the most common presentation1, early symptoms such as persistent bedwetting, candidiasis, increased thirst, or weight loss often go unnoticed in young children. Diabetic ketoacidosis is an acute and potentially life-threatening metabolic complication of absolute insulin insufficiency. Various studies estimate diabetic ketoacidosis to be the initial presentation for approximately 30% of children, with notably increased risk in younger children, whose symptoms are frequently overlooked and who are often quicker to deteriorate1,2.

In the setting of diabetic ketoacidosis, insulin deficiency paired with an increase in counter-regulatory hormones (glucagon, catecholamines, cortisol, and growth hormone) promotes a catabolic state and guides the body to exploit triglycerides and amino acids in place of glucose for energy production. Excess circulating glucagon stimulates lipolysis and muscle catabolism, and glycerol and alanine serve as substrates for hepatic gluconeogenesis. Hyperglycemia develops due to increased gluconeogenesis, glycogenolysis, and compromised glucose utilization at the peripheral tissues3.

During prolonged insulin-deficient states, oxaloacetate is shunted into gluconeogenesis, depleting the oxaloacetate pool within hepatic mitochondria. In the absence of adequate TCA cycle activity, acetyl-CoA from β-oxidation of the free fatty acids liberated by lipolysis is converted into ketones. The major products of ketogenesis are strong organic acids, which, in conjunction with high production of lactate, cause a high anion-gap metabolic acidosis4.

Simultaneously, hyperglycemia and hyperketonemia instigate osmotic diuresis, resulting in a marked loss of water and electrolytes through the urine, further worsened by nausea and vomiting. Hypovolemia can lead to increased catecholamine production and downstream glucagon production, worsening the patient’s already dire hyperglycemic state5. Excessive volume loss may result in renal hypoperfusion, explaining the high incidence of acute kidney injury in patients with diabetic ketoacidosis6,7.

On top of the already described events, T1D causes several acute and chronic changes in hematological parameters. Red blood cells suffer a dysregulated volume homeostasis that impacts hemoglobin concentrations, threatening erythrocyte survival8, as well as acute higher glycemic levels promote altered myelopoiesis and inflammation-related gene signature9,10.

Conversely, long-term hyperglycemia, which causes oxidative DNA damage, prompts a high proportion of apoptotic white blood cells in both animal models and patients, likely explaining the observed chronic decrease in neutrophils, lymphocytes, and basophils, as well as their relative functional degradation11,12. Additionally, lower platelet viability, lower platelet ATP content, and higher platelet counts have been recorded upon initial diabetes presentation, potentially predisposing patients to microangiopathy13. Generally, as erythrocytes are voracious consumers of glucose, hyperglycemia is recognized to affect their production, rheology, lifespan, and function14.

Peroxidation of membrane lipids is observed as a downstream complication of hyperglycemia. Acutely, membrane peroxidation is linked to disruption of cell hydration status and to several of the above alterations in hematological parameters15. After restoration of normoglycemic levels, these alterations can cause severe hemolysis, particularly in patients with additional susceptibilities such as glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency or secondary to severe hypophosphatemia16.

Changes to hematologic parameters represent a considerable consequence and a biomarker of the metabolic alterations observed in diabetic patients. In this study, metabolomics and lipidomics analyses were utilized to investigate the metabolic pathway alterations that underscore the hematological changes observed in T1D patients with and without ketoacidosis at onset and following treatment with insulin. Furthermore, we exploited multiomics data for blood samples from over 13,000 healthy donors to locate the genetic polymorphisms most associated with these metabolic alterations, ultimately leading to findings that polymorphisms in BCKDHA (chromosome 19) and BCKDHB genes (chromosome 6), in healthy donors, were found to be significant predictors of acyl-carnitine levels in the pRBCs. Finally, to prove that the alterations highlighted in patients with T1D are independent of the autoimmune features of the disease, we sought after a proof of concept of the association between acyl-carnitine metabolism and the metabolism of branched-chain amino acids (BCAA), performing a complete multiomics profile of blood samples from patients with maple syrup urine disease (MSUD) that ultimately supported the role of elevated branched-chain amino acid-derived ketoacids in altered carnitine metabolism and disrupted hematological parameters in both MSUD and T1D patients.

Methods

Sample and patient data collection

The primary observational study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki at the University of Campania “L. Vanvitelli” upon Local Ethic Committee Approval (approval number 368) and collection of written informed consent for each patient. 27 patients with newly onset T1D (within a few hours from the first identification of hyperglycemic status) were taken care of according to standard clinical practice. Patients were sampled for baseline metabolic assessment with no other prior interventions apart from fluid replacement and before beginning Insulin therapy. Individual anonymized baseline and on-treatment characteristics are reported in Supplementary Data 1. 13 of the 27 patients qualified for a diagnosis of diabetic ketoacidosis by ISPAD clinical practice consensus guidelines 202217. At baseline, average glucose was 329 (±163) mg/dL and average HbA1c was 11.7 (±2.3) %. Patients underwent clinical management according to ISPAD guidelines17. Follow-up visits and sampling were performed after 15 (±5) days from the onset of the disease with an average subcutaneous Insulin therapy of 0.8 (±0.3) U/Kg and an average glucose level of 108 (±55) mg/dL (Supplementary data 1). 4 matching healthy controls were sampled for this dataset. As part of the Recipient Epidemiology and Donor evaluation Study (REDS) III RBC Omics, whole blood was collected from 13,091 donors enrolled across four different blood centers as previously described18. Whole blood was collected from three patients having a diagnosis of MSUD with a biallelic inactivating mutation of BCKDHA. This dataset employed sampling and analysis of 6 matching healthy controls. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki; specimens were collected at the Central Pennsylvania Clinic, Boston Children’s Hospital, and Lancaster General Hospitals under institutionally reviewed Protocol No. 2014-12 and upon signing of informed consent.

Blood-based matrices (plasma, whole blood, pRBCs) were only analyzed in this study.

Metabolites from plasma were extracted at a ratio of 1:25 and from whole blood and packed red blood cells at a ratio of 1:10 with cold MeOH:MeCN:H2O (5:3:2, v:v:v) and 100% MeOH for metabolomics/oxylipins/bile acids and lipidomics analysis, respectively. Suspensions were vortexed vigorously for 30 min at 4 °C. Insoluble material was pelleted by centrifugation (18,213 × g, 10 min, 4 °C), and supernatants were isolated for analysis by UHPLC-MS.

Metabolomics analysis

A Vanquish UHPLC system (Thermo) was coupled to an Orbitrap Exploris 120 mass spectrometer (Thermo). 10 μL injections of the samples were resolved across a 2.1 × 150 mm, 1.7 µm Kinetex SB-C18 column (Phenomenex) using a 5 min, reversed-phase gradient from a previously described method and as detailed in Supplementary Methods19. Resultant files were processed with El-Maven (Elucidata) alongside the KEGG database for metabolite assignment and peak integration as previously described20.

High-throughput metabolomics of the 13,091 REDS RBC Omics donors

Metabolomics extraction and analyses in a 96-well plate format were performed as described15,21,22,23,24,25,26. RBC samples were transferred on ice to a 96-well plate and frozen at −80 °C at Vitalant San Francisco prior to shipment in dry ice to the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus. Plates were thawed on ice, then a 10 μL aliquot was transferred with a multi-channel pipettor to 96-well extraction plates. A volume of 90 μL of ice-cold 5:3:2 MeOH:MeCN:water (v/v/v) was added to each well, with an electronically-assisted cycle of sample mixing repeated three times. Extracts were transferred to 0.2 µm filter plates (Biotage), and insoluble material was removed under positive pressure using nitrogen applied via a 96-well plate manifold. Filtered extracts were transferred to an ultra-high-pressure liquid chromatography (UHPLC-MS — Vanquish) equipped with a plate charger. A blank containing a mix of standards detailed before27 and a quality control sample (the same across all plates) were injected 2 or 4 times each per plate, respectively, to qualify instrument performance throughout the analysis. For each measured metabolite, median values on each plate were determined; all samples were normalized intra-plate to the respective median value prior to merging the entire dataset (principal component analyses – PCA of pre- vs post-normalization data are shown in Nemkov et al., Cell Metabolism 202426). Metabolites were resolved on a Phenomenex Kinetex C18 column (2.1 × 30 mm, 1.7 μm) at 45 °C using a 1-min ballistic gradient method in positive and negative ion modes (separate runs) over the scan range 65–975 m/z exactly as previously described21. The UHPLC was coupled online to a Q Exactive mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher). The Q Exactive MS was operated in negative ion mode, scanning in Full MS mode (2 μscans) from 90 to 900 m/z at 70,000 resolution, with 4 kV spray voltage, 45 sheath gas, and 15 auxiliary gas. Following data acquisition, .raw files were converted to.mzXML using RawConverter, then metabolites assigned and peaks integrated using El-Maven (Elucidata) in conjunction with an in-house standard library28. A list of experimental m/z, retention times, metabolite IDs (either KEGG or HMDB), and adducts is provided in Nemkov et al. Cell Metabolism 202426.

Lipidomics analysis

A Vanquish UHPLC system (Thermo) was coupled to a Q Exactive mass spectrometer (Thermo). 5 µL injections of the samples were resolved across a 2.1 × 30 mm, 1.7 µm Kinetex C18 column (Phenomenex) using a 5 min, reversed-phase gradient adapted from a previous method29. The Q Exactive was run independently in positive and negative ion modes, scanning using data-dependent MS2 (top 10) from 125–1500 m/z at 17,500 resolution, with 45 Arb sheath gas, 25 Arb auxiliary gas, and 4 kV spray voltage in both modes. Calibration was performed prior to the run using the PierceTM Positive and Negative Ion Calibration Solutions (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The run order of samples was randomized, and technical replicates were injected after every 12 samples to assess quality control. Lipid assignments and peak integration were performed using LipidSearch v 5.0 (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

mQTL analysis

Metabolite quantitative trait loci (mQTL) analysis was performed as previously described for the REDS RBC Omics cohort and is described in detail within Supplementary Methods25. Briefly, genotyping was performed via Transfusion Medicine microarray. 811,782 SNPs passed quality control and were utilized for further analysis. Shape-IT30 was used to phase the data, followed by imputation using Impute 2 alongside the 1000 Genomes Project phase 3 all-ancestry reference haplotypes31. We utilized R-4.4.1 paired with the SNPRelate R-package to calculate principal components of ancestry32. We then used the ProbABEL R-package to perform association analyses for acyl-carnitines using an additive SNP model33. We adjusted for sex, age, frequency of blood donation in the last 2 years, blood donor center, and 10 ancestry principal components. OASIS was used to annotate the top SNPs with position, chromosome, allele frequencies, closest gene, type of variant, position relative to the closest gene model, and other information.

Statistical analysis

Using MetaboAnalyst 5.0 software, also used for plotting linear regressions and generating a central network plot, raw T1D experiment metabolomics and lipidomics data were autoscaled and normalized either by median, for plasma, or by sum, for whole blood and packed red blood cells. MSUD experimental data was autoscaled only. Employing the normalized data, groups were compared using analysis of variance (ANOVA) with false discovery rate (FDR) correction in MetaboAnalyst or Student’s t-test, and heat maps were generated for each matrix34. Results were analyzed via non-parametric two-tailed Spearman’s rank correlation tests with the un-normalized, autoscaled data, and to generate correlation plots for variables of interest. Additional figures were generated using GraphPad Prism 10 and BioRender.com.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

Diabetic ketoacidosis has predictable, yet variable effects on clinical parameters

We compared clinical parameters for 27 children (ages 2–16, average age 8) with T1D at the time of diagnosis (Fig. 1A) and found values consistent with the existing literature on diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) (Fig. 1B). Numerical data for the patient characteristics shown in the heat map are included in Supplementary Table 1. Patients with ketoacidosis had significantly elevated blood ketones, acidosis, and high creatinine. Although not statistically significant in our patients’ population, patients presenting with DKA had higher plasma osmolality at onset as well as elevated heart rate, systolic blood pressure, and diastolic blood pressure. Hematological changes related to hemolysis had a non-significant trend of slightly increased severity in patients with DKA, with, for example, patients with DKA showing a 26% reduction in haptoglobin and 32% increase in sideremia compared to patients with the absence of DKA, with no children lower than 2 years of age tested. Overall, hematological baseline parameters were overlapping among the two categories and tended to normalize upon insulin replacement, as described below, with a significant and substantial increase in MCV, for example. Despite being a life-threatening condition, there is a notable absence of distinct clinical biomarkers for T1D acute and long-term adverse events and comorbidities, including markers of DKA severity, warranting a deeper molecular investigation.

A Workflow for the collection of plasma, whole blood, and packed red blood cells from patients for metabolomics and lipidomics analysis. B Heat map of the clinical parameters measured at diagnosis for type 1 diabetes mellitus patients, both with and without ketoacidosis. C Heat map of the clinical parameters collected for patients at initial diagnosis (0 d) with type 1 diabetes mellitus and after 14 days (14 d) of insulin therapy. D Heat map of the combined metabolome and lipidome of patient plasma before and after treatment with insulin. E Heat map of the combined metabolome and lipidome of patient red blood cells before and after treatment with insulin. Within all heat maps, hierarchical clustering was utilized to group metabolites, lipids, or clinical parameters that presented similarly across patients. Significant metabolites (p < 0.05) were marked with *.

Insulin therapy triggers large-scale changes in clinical parameters and blood chemistry

Two weeks of insulin therapy yielded distinct and significant changes in hematological parameters in T1D patients independently of the type of onset (Fig. 1C, numerical values in Supplementary Table 2). When observing the fifteen most significantly affected clinical parameters, creatinine (0.74–0.57 mg/dL, p < 0.0001) and glucose (329–108 mg/dL, p < 0.0001) were predictably decreased upon treatment. Hematological changes were especially pronounced, as evidenced by large decreases in neutrophil (5200–3500/µL, p < 0.0001), and white blood cell counts (10,130–7420/µL, p < 0.0001), as well as MCHC (35.5–32.7 f/dL, p < 0.0001), hemoglobin (13.6–12.9 mg/dL, p < 0.05), and ferritin (119–39 ng/mL, p < 0.001) levels. Mean corpuscular volume significantly and substantially increased (75.7–83.9 fL, p < 0.0001), and the variability of RBC size increased (RDW-SD, 34.8–41.2 fL, p < 0.01). These findings suggest that hematological shifts are a critical component of the physiological effects of absolute insulin deficiency and subsequent treatment. These dramatic changes are seen before and after treatment, regardless of whether patients had an initial presentation of diabetic ketoacidosis (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Changes to the molecular composition of blood components were assessed using mass-spectrometry-based metabolomics and lipidomics of plasma (Fig. 1D) and red blood cells (Fig. 1E) at the time of diagnosis and after two weeks of insulin therapy in comparison to healthy controls (n = 4). In both biological compartments, insulin treatment decreased fatty acids and acyl-carnitines. Additionally, glycolytic intermediates were decreased in RBCs, and TCA cycle intermediates were increased in plasma following treatment (Fig. 1D, E, fully labeled heat maps are in Supplementary Fig. 2). Purines accumulated upon insulin treatment selectively in the RBCs.

Linear regressions for key metabolites involved in glycolysis and purine metabolism illustrate changes in each metabolite from the timepoint of initial diagnosis to after two weeks of insulin therapy (Supplementary Fig. 3). In plasma, glucose (FC 0.512) and pyruvate (FC 0.922) decreased as insulin increased GLUT-2 insertion into plasma membranes. Within the red blood cells, we observed increased glycolytic intermediates, indicating increased utilization of glycolysis as a source of energy. Lactate levels also decreased (FC 0.802), likely due to decreased reliance on anaerobic respiration. Diabetes is known to be associated with increased purine catabolism, so decreasing hypoxanthine levels (FC 0.591) and increased downstream allantoate (FC 1.413) were consistent with existing knowledge.

Additional linear regressions for metabolomics data collected from whole blood show increased levels of TCA metabolites, indicating increased utilization of aerobic respiration for energy generation (Supplementary Fig. 4). Branched-chain amino acids leucine/isoleucine (FC 0.642) decrease after treatment. Hydroxybutyrylcarnitine (AC 4:OH, FC 0.170) and valerylcarnitine (AC 5:0, FC 0.563) are also found to massively decrease following insulin therapy. The findings of the linear regressions for metabolites found in plasma, pRBCs, and whole blood, and their congruence with the existing literature on T1D, substantiate the reliability of our data for further analysis.

Pathway analyses reveal that alterations to energy and redox metabolism and lipid metabolism underlie clinical findings characteristic of type 1 diabetes mellitus patients

Using a central network plot to visualize correlations between clinical measurements of hematological parameters reveals positive associations of haptoglobin to age, \({{\rm{HCO}}}_{3}^{-}\), base excess, creatinine (after 24 h), and the ratio between onset creatinine and follow-up creatinine.

Correlation of multiomics data merged with clinical features yields lipid metabolism and energy/redox metabolism as most significantly correlated with changes observed in patients’ clinical measurements between their initial diagnosis and after two weeks of insulin therapy (Fig. 2C). Next, we used Spearman correlations of merged multiomics data with clinical parameters of highest relevance to diabetic ketoacidosis. Top positive correlates of clinical lab measurements of blood creatinine were mass-spectrometry measurements of creatinine in whole blood and RBCs (Fig. 2D). Similarly, a strong positive correlation was noted between clinically measured glucose and our MS measurements, internally validating the strength of our analytical platform in this study (Fig. 2E).

A Central network plot showing the variables most associated via Spearman’s rho with hematological parameters measured in the study participants. Negative associations are labeled in blue and positive associations are labeled in red, while line thickness denotes the relative size of Spearman’s rho. B Schematic depicting metabolites which contribute to and are generated by the TCA cycle and urea cycle. C Correlation matrix of metabolites, lipids, and clinical variables across all studied specimens. Metabolites involved in energy and redox metabolism, as well as lipid metabolism, were highlighted as key correlates within this analysis. D–G Spearman rho correlation plots assessing the variables most correlated with D clinical measurements of creatinine (g/dL); E clinical glucose measurements (mg/dL); F ketonemia; G base excess. H Heat maps of the fatty acids and acyl-carnitines in red blood cells collected at initial diagnosis (0 d) and after 14 days (14 d) of insulin therapy. I Heat maps of the fatty acids and acyl-carnitines in plasma, collected at initial diagnosis (0 d) and after 14 days (14 d) of insulin therapy. Carnitines and fatty acids are presented by increasing the acyl chain length.

We next utilized Spearman rho to assess correlates to two principal clinical findings of diabetic ketoacidosis, ketonemia (Fig. 2F) and negative base excess (Fig. 2G). Both illuminated changes to acyl-carnitines, especially hydroxylated short-chain acyl-carnitines such as hydroxybutyrylcarnitine (AC 4-OH) in plasma. Increased plasma and whole blood acyl-carnitines were correlated with ketonemia and inversely correlated with base excess. In addition, sedoheptulose 7-phosphate was positively correlated with ketonemia and negatively correlated with base excess, indicating increased utilization of the pentose phosphate pathway during the ketoacidotic state.

Consequently, we asked whether steady-state levels of acyl-carnitines and fatty acids change with insulin treatment in plasma (Fig. 2H) and RBCs (Fig. 2I) on the basis of acyl chain length. Across all chain lengths, fatty acids and acyl-carnitines trended high at the time of diagnosis and declined following extended treatment. Changes were primarily seen within patient plasma, rather than within RBCs.

Correlation with HbA1c, used as a readout for the length and extent of hyperglycemia, indicated that ketonemia, liver enzymes (ALT, AST), creatine phosphokinase, and change in mean corpuscular volume were the top positive correlates with HbA1c levels. These findings were consistent with liver and tissue damage in the setting of sustained hyperglycemia. Rhamnose, reticulocytes (percent and concentration), and mean platelet volume were all negatively correlated with HbA1c (Supplementary Fig. 7A). Digging deeper into the alterations of mean corpuscular volume in patients with T1D, we identified negative correlations of mean corpuscular volume (Supplementary Fig. 7B) and change in mean corpuscular volume (from diagnosis to after two weeks of insulin treatment, Supplementary Fig. 7C) with electrolytes such as potassium, calcium, and sodium, and positive correlations with reticulocytes (percent and concentration).

Finally, we correlated our measurements to the initial insulin dose (Supplementary Fig. 7D) and the follow-up insulin dose (Supplementary Fig. 7E), both normalized to patient body weight. The top positive correlates with initial insulin dose, as expected, were HbA1c, ketonemia, and creatinine, all markers of hyperglycemia and/or ketoacidosis, indications for the provision of insulin to patients. The initial insulin dose, interestingly, was negatively correlated with insulin dose at follow-up. When considering follow-up insulin dose, the most positively correlated parameters were reticulocytes (percent and concentration), heptanoic acid, MPV, and rhamnose. Liver enzymes (AST and ALT) were negatively correlated with follow-up insulin dose, as well as serum electrolytes (specifically sodium and calcium), and change in mean corpuscular volume. These changes may potentially act as biomarkers for overall insulin deficit.

We generated similar Spearman rho plots for an additional nine clinical parameters that can be found in the Supplementary Material.

Polymorphisms of the BCKDH gene predict pRBC acyl-carnitine levels in pRBCs

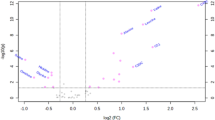

The blood phenotype of ketoacidosis-associated T1D in this cohort is strongly suggestive of disrupted BCAA/acyl-carnitine metabolism. Mature RBCs lack mitochondria and primarily employ free carnitine and acyl-carnitines for complex and cell-specific repair of oxidized membrane lipids via the Lands Cycle. Additionally, carnitine metabolism in RBCs has emerged as a strongly reproducible pathway in blood donors15. To interrogate the genetic basis for altered BCAA and carnitine metabolism in this context, we leveraged packed red blood cell specimens from the Recipient Epidemiology and Donor Evaluation Study (REDS)-III RBC Omics index donor cohort (n = 13,091 donors, units stored for 42 days). These units were profiled via genome-wide association studies, utilizing levels of butyrylcarnitine (AC 4:0, Fig. 3A), 2-Methylbutyroylcarnitine (AC 4:Me, Fig. 3B), valerylcarnitine (AC 5:0, Fig. 3C), and 3-hydroxyvalerylcarnitine (AC 5:OH, Fig. 3D) as continuous variables for mQTL analysis. To identify the genetic polymorphisms underlying L-carnitine levels, 870,000 SNPs were monitored, and polymorphisms in BCKDHA (chromosome 19) and BCKDHB genes (chromosome 6) were found to be significant predictors of acyl-carnitine levels in the pRBCs (Supplementary Table 3). While BCKDHA and B were common hits across multiple mQTL analyses, we must acknowledge that several other genetic traits were linked with heterogeneous levels of these ACs, including carnitine transporters SLC22A16, SLC22A4 and SLC22A5, carnitine o-acetyl-transferase (CRAT) – already the focus of recent study by our group15; or other enzymes involved in acyl-CoA or lipid metabolism (e.g., Dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase – DLD; Short-chain specific acyl-CoA dehydrogenase – ACADS; Methylcrotonoyl-CoA carboxylase subunit alpha – MCCC1 or 2; Biotin--protein ligase - HLCS), lipid oxidation (Polyunsaturated fatty acid 5-lipoxygenase -ALOX5 – already the focus of recent work on RBC-type ferroptosis23) or antioxidant pathways like glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD – Fig. 3A–D).

Data was generated using pRBCs from the REDS RBC Omics index donor cohort utilizing blood samples collected from 13,091 donors across 4 blood centers. Acyl-carnitines were quantified using MS and used as a metabolite quantitative trait locus (mQTL) for genome-wide association studies. Manhattan plots of A butyrylcarnitine (AC 4:0), B 2-methylbutyroylcarnitine (AC 4:Me), C valerylcarnitine (AC 5:0), D hydroxyvalerylcarnitine (AC 5:OH). Genetic variants above the significance threshold of p = 5e-8 are labeled. E Locus zoom mapping the region on chromosome 19 that codes for BCKDHA. F Locus zoom mapping the region on chromosome 6 that codes for BCKHDB.

Since this cohort of donors represents a large group of healthy adult blood donors, these findings suggest that BCKDHA and BCKDHB polymorphisms are prominent predictors of acyl-carnitine levels in the overall human population. SNPs identified in BCKDHA/B in healthy donors relate to metabolic variability affecting acyl-carnitine homeostasis and have not been reported as disease-causing variants (e.g., intron variants like rs10409485, rs10413735, rs10416743, or rs10422956 for BCKDHA – full list in Supplementary Table 3; or rs1040592 or rs1040594 for BCKDHB). However, a subset of the 13,091 donors were found to be heterozygote carriers for rs10864, a clinical variant (RCV000289821.5; NM_183050.4(BCKDHB):c.*2282C>T) associated with MSUD.

Markedly high rates of recombination were observed at the BCKDHA (Fig. 3E) and BCKDHB (Fig. 3F) loci, indicating high genetic diversity. BCKDHA and BCKDHB encode branched-chain ketoacid dehydrogenase E1 subunit alpha and beta, respectively. These form a heterotetrameric α-ketoacid decarboxylase subunit of the branched-chain α-ketoacid dehydrogenase complex, which is critical for the catabolism of branched-chain amino acids valine, leucine, and isoleucine. Deficiency of BCKD causes maple syrup urine disease (MSUD), an autosomal recessive inborn error of metabolism where rare biallelic loss-of-function variants cause enzymatic inactivation of the branched-chain alpha-ketoacid dehydrogenase (BCKDH), required to metabolize the three branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) leucine, isoleucine, and valine.

Biallelic inactivating mutation of the BCKDHA gene impacts BCAA and acyl-carnitine metabolism

As described above, our unbiased analysis of 870,000 SNPs from a cohort of healthy donors (REDS-III RBC Omics index donor cohort) showed several polymorphisms in genes involved in acyl-CoA or lipid metabolism, lipid oxidation, or antioxidant pathways to be significant predictors of acyl-carnitine levels in the pRBCs. Being MSUD, the only monogenic disease linked to genes identified in a prior dataset, we focused our primary analysis on the shared metabolic anomalies among T1D and MSUD patients. Patients with a deficiency of branched-chain α-ketoacid dehydrogenase (BCKD) presented indeed an ideal cohort in which to test the association between acyl-carnitine metabolism and the metabolism of BCAAs. BCAAs are fundamental anabolic intermediates for skeletal muscle and whole-body energy homeostasis; moreover, they also act as signaling molecules35. The Pennsylvania Amish population has a high incidence of the classical Ashkenazi Jewish variant of BCKDHA (538G>C, p.R183P)36. This affects the same BCKDHA protein highlighted in the previous REDS study15 but represents a different inactivating mutation. For this comparison, whole blood from 3 patients with a biallelic BCKDHA mutation and 6 healthy controls was collected and metabolically profiled (Fig. 4A). This part of the study aimed to investigate the broader impact of MSUD on blood metabolism beyond dysregulated branched-chain amino acids (BCAA), with a focus on ketocids and acyl-carnitines. As such, hematological parameters were not assessed in this small MSUD cohort.

A Workflow for the collection and metabolomics analysis of whole blood from controls and patients with MSUD. B Partial least-squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA). C Variable importance plot with the metabolites that contributed most to the separation between groups in the PLS-DA. D Heat map with hierarchical clustering of the top 50 metabolomic features by t-test. Acyl-carnitines were bolded, and branched-chain amino acids and their associated ketoacids were bolded in green. E Violin plots for branched-chain amino acids and their associated ketoacids. F Violin plots for several short-chain acyl-carnitines.

A partial least-squares discriminant analysis showed distinct separation between these groups based on their metabolomes (Fig. 4B). The metabolites that contributed the most to this separation were L-Isoleucine and 3-Methyl-2-Oxobutanoate, the ketoacid of L-Valine. Since MSUD is a disease of impaired branched-chain amino acid metabolism, the significant contributions of these metabolites to group separation were unsurprising. It is also notable that another driver of the separation between these groups was butanoyl-l-carnitine (AC 4:0), a short-chain acyl-carnitine (Fig. 4C).

A heat map (top 50 metabolites by t-test) elaborates on the differences in the metabolome between control and MSUD patients (Fig. 4D). L-Isoleucine, L-Leucine, and the ketoacids of all three branched-chain amino acids were shown to be elevated within the MSUD blood samples by this heat map, differently from patients with newly onset T1D that showed similar directionality in terms of organic acidemia but with different metabolites (e.g., acetoacetate, β-hydroxybutyrate). Indeed, the BCAA and alpha-ketoacid impairment reported in the MSUD, linked to broader clinical symptoms due to the central nervous and immune systems, as well as skeletal muscle dysfunction, is due to a pathogenic defect in any BCKAD subunit, while the hallmark ketones of T1D ketoacidosis are due to a metabolic rewiring due to the lack of Insulin. Three of the top 50 features are acyl-carnitines, which were lower in patients with the mutant BCKDHA. As one of the four acyl-carnitines used previously as an mQTL, the presence of butyrylcarnitine (AC 4:0) within this heat map further reinforces its association with the BCKDHA locus.

Violin plots confirmed elevated levels of branched-chain amino acids and their corresponding ketoacids in the blood of MSUD patients (Fig. 4E). Additionally, violin plots showed consistently lower levels of short-chain acyl-carnitines in MSUD patients’ blood relative to controls (Fig. 4F). Indeed, on top of sharing common metabolic features, the directionality of the changes in acyl-carnitine levels differs between patients with T1D or MSUD, due to the differing primary metabolic derangements (lipolysis-driven vs. BCAA catabolic block).

Although this analysis was limited by the small MSUD patient cohort (n = 3) due to the rarity of this oftentimes lethal autosomal recessive disease, these results further cement the link between branched-chain amino acid oxidation by BCKDH and acyl-carnitine homeostasis. While DKA and MSUD are etiologically distinct, our findings showed that both conditions converge on shared metabolic signatures involving disrupted BCAA and acyl-carnitine metabolism. In DKA, insulin deficiency drives enhanced lipolysis and amino acid catabolism, leading to elevated levels of ketone bodies and BCAA-derived ketoacids. Similarly, MSUD, due to inactivating mutations in BCKDHA/B, leads to pathological accumulation of BCAA and their corresponding ketoacids. By extension, our findings act as a guiding light for our investigation into how acyl-carnitine levels become disrupted in the setting of diabetic ketoacidosis, which results in elevated branched-chain ketoacids in plasma, like that observed in MSUD patients.

Discussion

In the present study, we provide a multiomics perspective on the hematologic changes that occur in type 1 diabetes patients before and during insulin treatment. Previous studies have reported numerous changes to hematological parameters in untreated T1D patients, but the specific molecular alterations underlying these changes and their clinical relevance have yet to be explored. Thus, we exploited mass-spectrometry-based metabolomic and lipidomic techniques, paired with clinical data, to elucidate the intra- and extracellular chemical transformations that underlie hematologic stress in T1D patients.

In most tissues, L-carnitine is heavily utilized for the transfer of long-chain fatty acids into the mitochondria for the purpose of β-oxidation. Though mature RBCs lack mitochondria and other organelles, they employ L-carnitine and acyl-carnitines for complex and cell-specific repair of oxidized membrane lipids via the Lands Cycle37. Peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids in the presence of reactive oxygen species and especially following depletion of the glutathione pool may instigate cellular ferroptosis, a non-apoptotic cell death mechanism. Sensitivity to ferroptosis has been found to be modulated by the degree of unsaturation of membrane lipids38. Consequently, the metabolic pathways overseeing membrane repair, fatty acid metabolism, and response to free radical damage are critical for cell membrane and hence cell integrity39.

A recent pioneering study by Nemkov et al. using the REDS dataset reported that carnitine metabolism was the most reproducible metabolic pathway within individual donors across assays of blood donations collected at different timepoints. Using genome-wide association studies, they identified genomic features that explain the heterogeneity of acyl-carnitine composition observed across the donor pool. Additionally, they reported that depletion of carnitine pools in end-of-storage RBCs was associated with hemolysis and increased erythrocyte vesiculation, congruent with previous research on the role of acyl-carnitines in membrane repair40.

In this study, we found broad dysregulation of acyl-carnitine and fatty acid metabolism upon initial presentation of T1D in patients both with and without ketoacidosis. Further analyses revealed that ketoacidosis, which represents a more severe presentation of T1D, is significantly correlated with elevated levels of acyl-carnitines, notably oxidized acyl-carnitines such as AC 4:OH. L-carnitine was also negatively correlated with characteristics of ketoacidosis, representing a depletion of the carnitine pool.

Acyl-carnitines, which interfere with insulin signaling and impair cellular glucose uptake, additionally disturb glucose homeostasis41. Furthermore, inflammation and secondary oxidative stress can worsen insulin resistance42. In the context of autoimmune destruction of insulin-producing pancreatic beta cells, these adaptive changes become maladaptive, worsening the metabolic and clinical features of T1D.

Following multiple correlation analyses, we propose that these changes underlie many of the altered hematological parameters observed in type 1 diabetes mellitus patients at presentation: elevated hematocrit, hemoglobin, platelet count, ferritin, sideremia, and reticulocytes, with low haptoglobin level, with some of them linked to the T1D primary inflammatory state and others to the metabolic alterations. Upon two weeks of insulin treatment, these patients had pronounced hematological changes. These clinical findings suggest that hematological shifts are a critical component of the physiological effects of absolute insulin deficiency and subsequent treatment, and altered carnitine metabolism may underlie these changes, acting as a biomarker of newly onset T1D-metabolic mixed features secondary to both insulin deficiency and resistance.

Next, we utilized findings from the previously described REDS publication40 to characterize the genetic polymorphisms associated with those acyl-carnitines most significantly associated with markers of insulin deficiency and/or ketoacidosis. mQTL analysis identified polymorphisms in BCKDHA and BCKDHB as significant predictors of acyl-carnitine heterogeneity. Interestingly, deficiency of BCKD activity is a well-documented inborn error of metabolism, resulting in maple syrup urine disease. To investigate the association between BCKD deficiency and acyl-carnitine dysregulation, we collected whole blood samples from MSUD patients with a nonsynonymous BCKDHA variant. In addition to changes in branched-chain amino acid metabolism, which distinguished these patients from controls, we observed that multiple short-chain acyl-carnitines were significantly lower in the MSUD patients. In addition, the most affected acyl-carnitines were those most correlated with the T1D phenotype, including AC 4:0 and AC 5:1.

The outcomes presented in this manuscript suggest that altered branched-chain amino acid metabolism may impede normal acyl-carnitine and Lands cycle function. Plasma branched-chain amino acid levels are elevated in patients with insulin resistance and/or deficiency43. Branched-chain amino acids, obtained from both diet and proteolysis, have been shown to both decrease insulin sensitivity and stimulate insulin secretion, worsening a patient’s presentation of T1D44. In addition, in the setting of DKA, in which depletion of the oxaloacetate pool stalls hepatic gluconeogenesis, we may expect branched-chain amino acid levels to rise. While leucine is ketogenic, isoleucine and valine are gluconeogenic amino acids and thus build up in the bloodstream, potentially acting as signaling molecules for multi-organ metabolic crosstalk.

This study has several limitations inherent to its ambitious aim of identifying shared metabolic pathways between two diseases of distinct etiopathogenesis—type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1D) and maple syrup urine disease (MSUD). First, the rarity of both conditions (particularly MSUD) and the stringent inclusion criteria necessarily limited the sample sizes, which may restrict the statistical power to detect subtler metabolic alterations or to perform subgroup analyses. Second, the cross-sectional design limits our ability to capture dynamic changes in metabolism over the course of disease progression or treatment beyond the two-week window analyzed in the T1D cohort. Third, by local clinical protocols, patients with the most severe presentation of T1D (e.g., those requiring intensive care unit admission) were not enrolled, potentially excluding key metabolic extremes from our dataset.

In addition, the REDS-III RBC Omics dataset, while extensive and well-powered for mQTL analysis, is composed of adult donors and thus may not fully recapitulate age-specific metabolic profiles relevant to pediatric T1D. Furthermore, although our focus was on branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) metabolism and its downstream acyl-carnitine signatures, this narrowed lens may have missed additional relevant metabolic pathways that differ or overlap between T1D and MSUD. Moreover, while the methods used in the manuscript provide a high level of confidence in metabolite annotation, it must be acknowledged that the ultra-high-throughput metabolomics methods leveraged in this study – while critical to allow the analysis of over 13 thousand samples across multiple cohorts of patients with T1D, MSUD and healthy blood donors, was insufficient to analytically resolve isobaric isomers that could be otherwise resolved with slower throughput LC gradients or orthogonal approaches, such as chemical derivatization, gas chromatography, or ion mobility. All the above will be the focus of future longitudinal and mechanistically focused investigations.

Summarizing, by profiling the multi-pathway effects of insufficient branched-chain amino acid catabolism in MSUD patients, we were able to confirm broad changes to lipid bilayer composition and acyl-carnitine levels within patient blood samples in response to the buildup of branched-chain amino acids and their associated ketoacids.

Finally, beyond elucidating the pathway alterations that underlie blood cells’ responses to insulin deficiency, this investigation took a step forward in the use of molecular assays for the study of metabolic disease. Here, we generated a multiomics dataset for the further investigation of metabolic and lipidomic alterations that occur in the setting of T1D, DKA, and insulin therapy, which may inform future analyses. In the absence of abundant distinct clinical markers for severity and long-term prognosis of diabetic ketoacidosis, the changes observed in acyl-carnitines may serve as a molecular fingerprint for DKA for earlier detection and optimized short- and long-term treatment of this life-threatening T1D complication. Additionally, these hematologic perturbations may serve as biomarkers for the relative physiological burden of hyperglycemia and insulin deficiency, as well as the effectiveness of treatment, in T1D patients.

These findings also offer insight into MSUD, a rare and severe disease that typically manifests as early-onset failure to thrive, developmental delays, and neurological injury in infants when left undetected and thus untreated45. Though this was a small cohort, this study takes steps toward unearthing additional molecular fingerprints that can make MSUD diagnosis more swift and precise, so as to prevent the irreversible sequelae of untreated disease.

Such analyses may open doors for targeted investigation into potential treatments for hematologic fluctuations upon insulin infusion and for improving insulin sensitivity. For instance, supra-physiological levels of L-carnitine supplementation have been used to improve anemia in patients with chronic hepatitis46, chronic kidney injury47, and to boost RBC storage capabilities40, and may also be considered within this selected patient population. Moreover, L-carnitine supplementation has been shown to reduce cardiac microvascular injury in an animal model of diabetic cardiomyopathy48. Given the prevalence of type 1 diabetes mellitus and related morbidity and mortality, as well as the absence of reliable biomarkers for risk stratification and treatment effectiveness, taking strides to document the disease’s molecular phenotype may be the key toward deeper understanding, more accurate diagnosis, and more nuanced treatment of this multi-system disease.

Data availability

The T1D clinical and high-throughput metabolomics and lipidomics datasets supporting the findings of this study are provided in Supplementary Data 1. Figures 1 and 2, along with all other figures and tables in the Supplementary Information, are based on analyses of Supplementary Data 1. mQTL analysis and data represented in Fig. 3 are derived by re-analysis of the dataset described by Nemkov et al.15. All other data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Mencher, S. R., Frank, G. & Fishbein, J. Diabetic ketoacidosis at onset of type 1 diabetes: rates and risk factors today to 15 years ago. Glob. Pediatr. Health 6, 2333794x19870394 (2019).

Dabelea, D. et al. Trends in the prevalence of ketoacidosis at diabetes diagnosis: the SEARCH for diabetes in youth study. Pediatrics 133, e938–e945 (2014).

Hatting, M., Tavares, C. D. J., Sharabi, K., Rines, A. K. & Puigserver, P. Insulin regulation of gluconeogenesis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1411, 21–35 (2018).

Laffel, L. Ketone bodies: a review of physiology, pathophysiology and application of monitoring to diabetes. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 15, 412–426 (1999).

Palmer, B. F. & Clegg, D. J. Electrolyte and acid-base disturbances in patients with diabetes mellitus. N. Engl. J. Med. 373, 548–559 (2015).

Hursh, B. E., Ronsley, R., Islam, N., Mammen, C. & Panagiotopoulos, C. Acute kidney injury in children with type 1 diabetes hospitalized for diabetic ketoacidosis. JAMA Pediatr. 171, e170020 (2017).

Marzuillo, P. et al. Acute kidney injury and renal tubular damage in children with type 1 diabetes mellitus onset. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 106, e2720–e2737 (2021).

Gallagher, P. G. Disorders of erythrocyte hydration. Blood 130, 2699–2708 (2017).

Nagareddy, P. R. et al. Hyperglycemia promotes myelopoiesis and impairs the resolution of atherosclerosis. Cell Metab. 17, 695–708 (2013).

Fang, X. et al. Glycemic reduction alters white blood cell counts and inflammatory gene expression in diabetes. J. Diabetes Complicat. 32, 1027–1034 (2018).

Jafar, N., Edriss, H. & Nugent, K. The effect of short-term hyperglycemia on the innate immune system. Am. J. Med. Sci. 351, 201–211 (2016).

Rayfield, E. J. et al. Infection and diabetes: the case for glucose control. Am. J. Med. 72, 439–450 (1982).

Wu, F. et al. Platelet mitochondrial dysfunction of DM rats and DM patients. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 8, 6937–6946 (2015).

Wang, Y. et al. The relationship between erythrocytes and diabetes mellitus. J. Diabetes Res. 2021, 6656062 (2021).

Nemkov, T. et al. Genetic regulation of carnitine metabolism controls lipid damage repair and aging RBC hemolysis in vivo and in vitro. Blood https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2024023983 (2024).

Turpin, C. et al. Enhanced oxidative stress and damage in glycated erythrocytes. PLoS ONE 15, e0235335 (2020).

Glaser, N. et al. ISPAD clinical practice consensus guidelines 2022: diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state. Pediatr. Diabetes 23, 835–856 (2022).

Endres-Dighe, S. M. et al. Blood, sweat, and tears: red blood cell-omics study objectives, design, and recruitment activities. Transfusion 59, 46–56 (2019).

Nemkov, T., Reisz, J. A., Gehrke, S., Hansen, K. C. & D'Alessandro, A. High-throughput metabolomics: isocratic and gradient mass spectrometry-based methods. Methods Mol. Biol. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-9236-2_2 (2019).

Nemkov, T., Hansen, K. C. & D'Alessandro, A. A three-minute method for high-throughput quantitative metabolomics and quantitative tracing experiments of central carbon and nitrogen pathways. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. https://doi.org/10.1002/rcm.7834 (2017).

Nemkov, T., Yoshida, T., Nikulina, M. & D’Alessandro, A. High-throughput metabolomics platform for the rapid data-driven development of novel additive solutions for blood storage. Front. Physiol. 13, 833242 (2022).

Nemkov, T., Reisz, J. A., Gehrke, S., Hansen, K. C. & D’Alessandro, A. High-throughput metabolomics: isocratic and gradient mass spectrometry-based methods. Methods Mol. Biol. 1978, 13–26 (2019).

D’Alessandro, A. et al. Ferroptosis regulates hemolysis in stored murine and human red blood cells. Blood 145, 765–783 (2025).

D’Alessandro, A. et al. Genetic polymorphisms and expression of Rhesus blood group RHCE are associated with 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate in humans at high altitude. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2315930120 (2024).

Nemkov, T. et al. Regulation of kynurenine metabolism by blood donor genetics and biology impacts red cell hemolysis in vitro and in vivo. Blood 143, 456–472 (2024).

Nemkov, T. et al. Biological and genetic determinants of glycolysis: phosphofructokinase isoforms boost energy status of stored red blood cells and transfusion outcomes. Cell Metab. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2024.06.007 (2024).

Stefanoni, D. et al. Red blood cell metabolism in Rhesus macaques and humans: comparative biology of blood storage. Haematologica 105, 2174–2186 (2020).

Nemkov, T., Hansen, K. C. & D’Alessandro, A. A three-minute method for high-throughput quantitative metabolomics and quantitative tracing experiments of central carbon and nitrogen pathways. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 31, 663–673 (2017).

Reisz, J. A., Zheng, C., D’Alessandro, A. & Nemkov, T. Untargeted and semi-targeted lipid analysis of biological samples using mass spectrometry-based metabolomics. Methods Mol. Biol. 1978, 121–135 (2019).

Delaneau, O., Coulonges, C. & Zagury, J. F. Shape-IT: new rapid and accurate algorithm for haplotype inference. BMC Bioinform. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-9-540 (2008).

Howie, B., Marchini, J. & Stephens, M. Genotype imputation with thousands of genomes. G3 https://doi.org/10.1534/g3.111.001198 (2011).

Zheng, X. et al. A high-performance computing toolset for relatedness and principal component analysis of SNP data. Bioinformatics https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bts606 (2012).

Aulchenko, Y. S., Struchalin, M. V. & van Duijn, C. M. ProbABEL package for genome-wide association analysis of imputed data. BMC Bioinform. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-11-134 (2010).

Pang, Z. et al. MetaboAnalyst 5.0: narrowing the gap between raw spectra and functional insights. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, W388–W396 (2021).

Mann, G., Mora, S., Madu, G. & Adegoke, O. A. J. Branched-chain amino acids: catabolism in skeletal muscle and implications for muscle and whole-body metabolism. Front. Physiol. 12, 702826 (2021).

Edelmann, L. et al. Maple syrup urine disease: identification and carrier-frequency determination of a novel founder mutation in the Ashkenazi Jewish population. Am. J. Hum. Genet. https://doi.org/10.1086/323677 (2001).

O’Donnell, V. B. New appreciation for an old pathway: the Lands Cycle moves into new arenas in health and disease. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 50, 1–11 (2022).

Yang, W. S. et al. Regulation of ferroptotic cancer cell death by GPX4. Cell 156, 317–331 (2014).

Bartolacci, C. et al. Targeting de novo lipogenesis and the Lands cycle induces ferroptosis in KRAS-mutant lung cancer. Nat. Commun. 13, 4327 (2022).

Nemkov. T. et al. Genetic regulation of carnitine metabolism controls lipid damage repair and aging RBC hemolysis in vivo and in vitro. Blood https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2024023983 (2024).

Petersen, K. F. et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in the elderly: possible role in insulin resistance. Science https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1082889 (2003).

Koves, T. R. et al. Mitochondrial overload and incomplete fatty acid oxidation contribute to skeletal muscle insulin resistance. Cell Metab. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2007.10.013 (2008).

Vanweert, F. et al. Role of branched-chain amino acid metabolism in the pathogenesis of obesity and type 2 diabetes-related metabolic disturbances BCAA metabolism in type 2 diabetes. Nutr. Diabetes https://doi.org/10.1038/s41387-022-00213-3 (2022).

Gancheva, S., Jelenik, T., Álvarez-Hernández, E. & Roden, M. Interorgan metabolic crosstalk in human insulin resistance. Physiol. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00015.2017 (2018).

Kenneson, A., Osara, Y., Pringle, T., Youngborg, L. & Singh, R. H. Natural history of children and adults with maple syrup urine disease in the NBS-MSUD Connect registry. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymgmr.2018.01.001 (2018).

Sato, S. et al. Efficacy of L-carnitine on ribavirin-induced hemolytic anemia in patients with hepatitis C virus infection. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. https://doi.org/10.3350/cmh.2018.0070 (2019).

Bonomini, M., Zammit, V., Pusey, C. D., De Vecchi, A. & Arduini, A. Pharmacological use of L-carnitine in uremic anemia: has its full potential been exploited?. Pharmacol. Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2010.11.006 (2011).

Li, S. et al. L-carnitine alleviates cardiac microvascular dysfunction in diabetic cardiomyopathy by enhancing PINK1-Parkin-dependent mitophagy through the CPT1a-PHB2-PARL pathways. Acta Physiol. https://doi.org/10.1111/apha.13975 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This study was additionally supported through funding by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R21HL150032, R01HL146442, R01HL148151, R01HL149714 to A.D.). The authors acknowledge support from the REDS RBC Omics and REDS-IV-P CTLS programs, sponsored by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute contract 75N2019D00033, and from the NHLBI Recipient Epidemiology and Donor Evaluation Study-III (REDS-III) RBC Omics project, which was supported by NHLBI contracts HHSN2682011-00001I, -00002I, -00003I, -00004I, -00005I, -00006I, -00007I, -00008I, and -00009I. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.R. and P.M. designed the T1D study; D.R. and F.V. collected the samples; D.R., M.C., and A.Z. collected clinical data and provided patients’ clinical care; P.J.N. and M.P.B. designed the REDS RBC Omics study; V.K. and H.D.M. designed and supervised the MSUD arm of the study; E.J.E. and G.P.P. performed mQTL analyses; A.L.G., M.D., J.A.R., S.B., T.N., and A.D. generated omics data; A.L.G., E.J.E., A.K., and A.D. prepared figures; A.L.G., D.R., J.A.R., M.D., and A.D. wrote the first version of the manuscript and all the authors contributed critically to the final version. Guarantor(s) are D.R. and A.D.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

A.D. and T.N. are founders of Omix Technologies and advisory board members of Hemanext Inc. A.D. is also a SAB member for Macopharma. D.R. received consulting fees from Nerviano Medical Sciences S.r.l. and Agios Pharmaceuticals, Inc., unrelated to the topic described and the research performed for the manuscript. The other authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Medicine thanks Amand Schmidt and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Roberti, D., Grier, A.L., Reisz, J.A. et al. Altered branched chain ketoacids underlie shared metabolic phenotypes in type 1 diabetes and maple syrup urine disease. Commun Med 5, 311 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01028-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01028-w