Abstract

Background

Cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic (CKM) syndrome is a systemic disorder characterized by pathophysiological interactions among metabolic risk factors. We aimed to determine the prevalence of CKM syndrome and investigate the association between CKM stages and mortality in patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD).

Methods

We extracted data on patients with MASLD from NHANES III and the Chinese Kailuan cohort, enrolling a total of 2159 and 22,865 patients, respectively. Hepatic steatosis was assessed by liver ultrasound. Participants were categorized into three groups according to CKM stages: 1, 2, and 3–4. Mortality was evaluated using the Cox proportional hazards model with or without inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW).

Results

In NHANES III cohort, 84.5% MASLD patients meet the criteria for CKM stage 2 or higher, and 36.9% deaths are observed. CKM stages 3–4 is an independent risk factor for liver fibrosis after adjusting for confounding factors (aOR 2.24 95% CI: 1.14–4.40, P = 0.019). By using stage 1 as a reference, an increasing trend in all-cause mortality is shown in patients with higher stages (stage 2: aHR 1.55, 95% CI 1.17–2.07, P = 0.003; stages 3–4: aHR 2.69, 95% CI 1.92–3.76, P < 0.001), as well as for cardiovascular mortality during a follow-up of 50,895.4 person-years. Moreover, patients with stages 3-4 have the highest mortality risk among different stages across most subgroups. Similar results are validated in Kailuan cohort.

Conclusions

The majority of MASLD patients also have CKM syndrome. A significant increase in all-cause and cardiovascular mortality is associated with advancing CKM stages.

Plain Language Summary

Cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic (CKM) syndrome is a health disorder that comprises cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, obesity, and diabetes. People with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) have too much fat in their liver, and this is linked with being overweight, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. It is unclear whether CKM syndrome is associated with poor prognosis for people who also have MASLD. We assessed the CKM syndrome prevalence and its association with death in a large number of people with MASLD. We found presence of CKM syndrome increased liver fibrosis and likelihood of death. This research indicates CKM syndrome is a critical determinant of prognosis in MASLD patients. Further research into targeted interventions would be beneficial to halt its progression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is the most common chronic liver disease, affecting over 30% of the population globally1,2. Increasing evidence suggests that MASLD is not solely a liver-specific condition, but rather a systemic disorder that frequently coexists with other diseases, including cardiovascular disease (CVD) and chronic kidney disease3. CVD constitutes the leading cause of mortality among MASLD patients4,5, while the prevalence of CKD is increasing in those patients.

Excess and dysfunctional adipose tissue is central to the progression of MASLD, leading to local and systemic metabolic dysfunctions6,7. Dysfunctional adipose tissue, particularly visceral adipose tissue, secretes pro-inflammatory and pro-oxidative products that exacerbate damage to arterial, cardiac, and kidney tissues8. The inflammatory processes triggered by dysfunctional adipose tissue result in the downregulation of anti-inflammatory factors, promoting endothelial cell dysfunction and decreasing insulin sensitivity, thereby contributing to metabolic disturbances and impairing vascular function9. The development of MASLD amplifies systemic inflammation and insulin resistance10. In the context of CVD, the products of dysfunctional adipose tissue contribute to the progression of atherosclerosis and myocardial injury in CVD11,12, and aggravate glomerulosclerosis, kidney tubular inflammation, and kidney fibrosis in the development of CKD13.

Based on these complex correlations among multiple systems, the American Heart Association (AHA) introduced cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic (CKM) syndrome, which is defined as a systemic disorder characterized by pathophysiological interactions among metabolic risk factors, CKD, and CVD14. In MASLD population, CKM syndrome potentially altered disease progression and clinical outcomes15. However, fewer studies evaluated CKM syndrome stages in MASLD patients. The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of CKM syndrome and to investigate the associations between CKM and mortality risks among MASLD population.

This study evaluates the prevalence of CKM syndrome and its relationship with mortality among patients with MASLD, utilizing data from the NHANES III and Kailuan cohorts, which included 2159 and 22,865 individuals with MASLD, respectively. Results indicate that most of MASLD patients meet the criteria for stage 2 or higher of CKM syndrome. Multivariate logistic regression analysis identified CKM stages 3–4 as an independent risk factor for liver fibrosis after adjusting for confounding factors. Advanced CKM stages show a strong association with increased all-cause and cardiovascular-related mortality, indicating that CKM status is a crucial prognostic factor in MASLD.

Methods

Participants

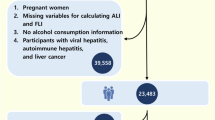

This cohort study obtained data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey [NHANES III; 1988–1994])16 and Kailuan cohort (2006-2016) in China17. Mortality data of NHANES III database were obtained from the Nationwide Death Index provided by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) of the Centers for Disease Control up to December 31, 2019. Cardiovascular mortality was defined as death due to heart diseases and cerebrovascular diseases. In NHANES III database, we identified 14,797 participants who underwent liver ultrasound examinations. Of them, 2159 individuals with MASLD were included after ruling out participants who did not meet the diagnosis of MASLD, had missing important data (FBG, HbA1c, urinary albumin to creatinine ratio [UACR] and eGFR), or combined with cancer at baseline (Fig. 1A). The Kailuan cohort was a prospective cohort study conducted in Tangshan, China, recruiting 101,511 participants aged 18–98 years18,19. The Kailuan cohort was conducted in large state-owned corporations with organized healthcare systems, including affiliated hospitals, and comprehensive medical insurance coverage. This allowed for thorough tracking of all participants’ mortality using medical insurance documents, social insurance records, hospital records, and death certificates. Cardiovascular mortality was defined according to ICD-10. In Kailuan cohort, 22,865 MASLD participants were eligible according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Fig. 1B). Both cohorts incorporate interviews, physical examinations, and laboratory measurements. NHANES data are publicly available through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/), and the Kailuan data can be accessed upon reasonable request and with permission from the Medical Ethics Committee of Kailuan General Hospital. NHANES was approved by the NCHS Research Ethics Review Board, and the Kailuan study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Kailuan Group Co., Ltd. Hospital/Medical Ethics Committee of Kailuan General Hospital. All participants provided informed consent.

Clinical and laboratory assessments

Physical and laboratory measurements for identifying MASLD and CKM stages were extracted and analyzed. In NHANES III cohort, demographic variables (age, sex, ethnicity, and poverty income ratio [PIR]), anthropometric variables (body mass index [BMI], waist circumference, systolic blood pressure [SBP], diastolic blood pressure [DBP], and alcohol use), medical history (stroke, congestive heart failure, cancer, coronary artery disease [CAD]), and laboratory parameters (platelet count [PLT], C-reactive protein [CRP], alanine transaminase [ALT], aspartate transaminase [AST], alkaline phosphatase [ALP], albumin [ALB], total cholesterol [TC], triglyceride [TG], high-density lipoprotein cholesterol [HDL-C], uric acid [UA], serum creatinine [Scr], estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR], urinary albumin, urinary creatinine, fasting blood glucose [FBG], 2 h post-load glucose, and hemoglobin A1c [HbA1c]) were included. Similarly, Kailuan cohort included the same data, except for AST, ALP, GGT, urinary albumin, urinary creatinine, and HbA1c. All clinical and laboratory assessments were performed at baseline and based on a single measurement.

Definition

MASLD was defined as hepatic steatosis detected by liver ultrasound examinations, plus at least 1 out of 5 cardiometabolic risk factors: (1) BMI ≥25 kg/m2 (23 kg/m2 in kailuan cohort) or waist circumference ≥94/80 cm in men/women (≥90/80 cm in men/women in kailuan cohort); (2) FBG ≥100 mg/dL (≥5.6 mmol/L) or 2 h post-load glucose level ≥140 mg/dL (≥7.8 mmol/L), or HbA1c ≥ 5.7%, or self-reported type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), or treatment with hypoglycemic drugs; (3) blood pressure ≥130/85 mmHg, or self-reported hypertension, or treatment with antihypertensive drugs; (4) plasma TG ≥ 150 mg/dL (≥1.70 mmol/L) or received lipid-lowering treatment; (5) plasma HDL-C ≤ 40 mg/dL (≤1.0 mmol/L) for men and ≤50 mg/dL (≤1.3 mmol/L) for women, or received lipid-lowering treatment. Additionally, individuals with other discernible causes, such as alcohol-related liver disease, viral hepatitis, or other aetiology, were excluded, and alcohol consumption should be less than 30 g/day in men and 20 g/day in women20. The CKM stages were determined as followed21: stage 0 is defined as no CKM risk factors, including overweight/obese (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 [≥23 kg/m2 in kailuan cohort]), hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia (TG < 135 mg/dL [<1.52 mmol/L]), metabolic syndrome, prediabetes, diabetes or CKD; stage 1 is defined as overweight, obese, high waist circumference (≥102/88 cm in men/women, or ≥90/80 cm in men/women if kailuan cohort), and/or prediabetes without the presence of other metabolic risk factors or CKD; stage 2 is considered as additional metabolic risk factors or moderate- or high-risk CKD22; stage 3 is diagnosed as very high-risk CKD22; stage 4 was defined based on the presence of established CVD, which included stroke, congestive heart failure, and CAD, as identified through self-reported physician diagnoses. Due to the absence of stage 0 participants and limited stage 4 cases, we categorized participants into three CKM stage groups: stage 1, stage 2, and combined stages 3–4.

Statistics and reproducibility

Statistical analyses were employed using R 4.3.3 (http://www.R- project.org). The baseline data missing by less than 10% is subjected to multiple imputation. ANOVA test or Kruskal-Wallis H test for continuous variables, and chi-square test for categorical variables were used to analyze the baseline characteristics of the participants. To evaluate the association between CKM stages and liver fibrosis, univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis were employed, and fibrosis-4 index (FIB-4) was used to assess liver fibrosis, with FIB-4 ≥ 1.3 indicating the presence of liver significant fibrosis23. Given the significant differences in mortality risk among patients of different ages, separate analyses were conducted for the population aged <60 years and ≥60 years. Cox proportional hazards model was used to assess the association of CKM stages with all-cause and cardiovascular mortalities, with sex, age, PIR, ethnicity, and FIB-4 adjusted. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis was further adjusted by inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW). Subgroup analysis was performed based on age, sex, BMI, ethnicity, and FIB-4. Statistical significance was defined as a -tailed P-value < 0.05.

Results

Population characteristics of the study population in NHANES III cohort

Table 1 showed the baseline characteristics of MASLD patients stratified by CKM stages in NHANES III cohort. 48.5% were male, and the median age was 43 (32, 59) years. CKM stage 1, 2, and 3–4 were present in 15.5%, 77.2%, and 7.3%, respectively. Patients with stages 3 and 4 had the highest proportions of hypertension (stage 1, 2, and 3–4: 0 vs 53.3% vs 71.3%, P < 0.001), diabetes mellitus (DM; 0 vs 24.8% vs 45.2%, P < 0.001) and CVD (0 vs 0 vs 93.0%, P < 0.001), highest levels of SBP (114 vs 126 vs 134, P < 0.001), BMI (27.4 vs 28.9 vs 29.4, P < 0.001), FBG (5.10 vs 5.35 vs 5.76, P < 0.001), HbA1c (5.2 vs 5.4 vs 5.8, P < 0.001), TC (4.94 vs 5.35 vs 5.69, P < 0.001) and UACR (4.57 vs 6.27 vs 10.42, P < 0.001), and the lowest level of eGFR (91.22 vs 85.32 vs 82.36, P < 0.001), while patients with stages 2 exhibited with the highest level of TG (1.05 vs 1.90 vs 1.57, P < 0.001) (Supplementary Data 2–4). Moreover, patients with CKM stages 3–4 were the oldest, had the highest CRP and FIB-4 (all P < 0.001). Significant disparities were observed between MASLD patients aged <60 and ≥60 years. Patients aged ≥60 years were more likely to have more metabolic risk factors, including higher proportions of hypertension, DM, CVD, and CKM stages 3–4, and higher levels of TC, UA, and higher FIB-4 (Supplementary Data 5).

Association between CKM stages and liver fibrosis

To examine the correlation between CKM stages and liver fibrosis in MASLD patients, univariate logistic regression analysis was used and it indicated that CKM stage 2 and stages 3–4 were both associated with liver fibrosis. Multivariate logistic regression analysis identified CKM stages 3–4 as an independent risk factor for liver fibrosis after adjusting for age, sex, PIR, ethnicity, BMI, TC, TG, waist circumference, hypertension and T2DM status (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 2.24 95% CI [95% confidence interval]: 1.14–4.40, P = 0.019) (Supplementary tables 3, 4).

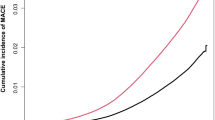

Relationship between CKM stages and mortality in NHANES III cohort

During a follow-up of 50,895.4 person-years, 36.9% of (797/2159) deaths were observed in MASLD patients, with the mortality rate of 15.7 per 1000 person-years in NHANES III cohort. Patients with CKM stages 3–4 (62.7 per 1000 person-years) had the highest all-cause mortality rate than those with CKM stage 1 (42.1 per 1000 person-years) and 2 (38.1 per 1000 person-years), respectively. Kaplan-Meier survival curves showed that MASLD patients with stages 3–4 had the lowest survival rate, followed by those with stage 1 after adjusting for age, sex, PIR, ethnicity and FIB-4 (Fig. 2). Similar results were obtained after adjusting for IPTW (Supplementary Fig. 1). Univariate Cox Proportional Hazards analysis indicated a steadily and statistically increasing trend in all-cause mortality for MASLD patients with higher CKM stages (Fig. 3A a), and similar findings were also found in subgroups based on age (except for no statistically significant difference between stage 2 and stage 1) (Fig. 3A b–c). After adjusting by sex, age, PIR, ethnicity, and FIB-4, similar results were still observed (Fig. 3A a–c). Furthermore, after adjusting for the confounders in IPTW, patients with stages 3-4 had a higher risk of all-cause mortality compared to those with stage 1(Fig. 3A a–c). We explored the association between CKM stages and cardiovascular mortality, and found resemble correlations as those found with all-cause mortality. The adjusted HRs for stages 3–4 in the overall cohort and patients aged ≥60 years were 4.60 (2.56–8.25) and 3.19 (1.53–6.65), respectively, while that in patients aged <60 years was up to 20.94 (7.75–56.53). After being weighted by IPTW, these associations remained significant (Fig. 3B a–c) (Supplementary Data 6). In sensitivity analyses further adjusting for smoking status, the associations between CKM staging and all-cause or cardiovascular mortality remained largely unchanged (Supplementary Tables 5, 6), supporting the robustness of our findings.

A All-cause mortality; B Cardiovascular mortality; a Overall cohort; b Patients aged <60 years; c Patients aged ≥60 years. Note: Hazard ratios were estimated using Cox proportional hazards regression models (two-sided tests). No adjustments were made for multiple comparisons. Multivariable model: adjusted for sex, age (not adjusted for age subgroup), poverty income ratio, ethnicity, and fibrosis-4 index; Adjusted for IPTW: the multivariable model was adjusted after IPTW. The central marker represents the hazard ratio (point estimate), and the error bars indicate the 95% confidence intervals. A (a): total number, n = 2159; stage 1, n = 335; stage 2, n = 1667; stages 3 and 4, n = 157. A (b): total number, n = 1631; stage 1, n = 306; stage 2, n = 1,269; stage 3–4, n = 56. A (c): total number, n = 528; stage 1, n = 29; stage 2, n = 398; stage 3–4, n = 101. B (a): total number, n = 1623; stage 1, n = 298; stage 2, n = 1238; stages 3 and 4, n = 87. B (b): total number, n = 1383; stage 1, n = 281; stage 2, n = 1067; stage 3–4, n = 35. B (c): total number, n = 240; stage 1, n = 17; stage 2, n = 171; stage 3–4, n = 52. IPTW inverse probability of treatment weighting, HR hazard ratio, 95% CI 95% confidence interval.

Subgroup analysis was performed based on sex (male and female), BMI (<25.0 kg/m2, 25.0–29.9 kg/m2, and ≥30 kg/m2), ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and Mexican-American) and FIB-4 (<1.3 and ≥1.3) across the overall cohort and different age groups. Patients with stages 3–4 also faced the highest all-cause risk among different CKM stages across most different subgroups before and after IPTW (Table 2 and Supplementary Data 7). Furthermore, the associations between CKM stages and CVD mortality maintained significant across most different subgroups before and after IPTW, except for most subgroups in patients aged ≥60 years (Supplementary Data 8, 9).

Relationship between CKM stages and mortality in Kailuan cohort

The Kailuan cohort predominantly consists of male participants (77.0%), with a median age of 52 years. The prevalence of CKM stages 1, 2, and 3–4 in this cohort is comparable to that observed in the NHANES III cohort, at 14.7%, 79.1%, and 6.2%, respectively. Individuals at CKM stages 3–4 exhibit the highest prevalence of hypertension (stage 1, 2, and 3-4: 0 vs 67.1% vs 71.3%, P < 0.001), diabetes (stage 1, 2, and 3–4: 0 vs 18.8% vs 38.9%, P < 0.001), and cardiovascular disease (stage 1, 2, and 3–4: 0% vs 0% vs 49.4%, P < 0.001), whereas those at stage 2 show the highest triglyceride levels (1.09 vs 1.95 vs 1.83, P < 0.001). These patterns closely mirror those reported in the NHANES III cohort. The baseline characteristics were detailed in Supplementary Tables 1, 2.

In Cox regression analysis, the risk of all-cause and CVD mortality in MASLD patients gradually increased significantly as CKM stages worsened in both the overall cohort and different age groups (Fig. 4) (Supplementary Data 10). Compared to those with stage 1, patients with stages 3–4 were significantly associated with an increased risk of all-cause and CVD mortality, and their adjusted HRs were higher than those of stage 2. In addition, male patients with stage 2 had a higher all-cause and CVD mortality risk compared to those with stage 1. Contrarily, female patients with stage 2 displayed no notable mortality risk compared to those with stage (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Data 10).

A All-cause mortality; B Cardiovascular mortality; (a) Overall cohort; (b) Patients aged <60 years; (c) Patients aged ≥60 years. Note: Hazard ratios were estimated using Cox proportional hazards regression models (two-sided tests). No adjustments were made for multiple comparisons. Multivariable model: adjusted for sex and age (not adjusted for age subgroup); adjusted for IPTW: the multivariable model was adjusted after IPTW. The central marker represents the hazard ratio (point estimate), and the error bars indicate the 95% confidence intervals. A (a): total number, n = 22,865; stage 1, n = 3366; stage 2, n = 18,074; stages 3 and 4, n = 1425. A (b): total number, n = 17,832; stage 1, n = 2982; stage 2, n = 14,074; stages 3 and 4, n = 776. A (c): total number, n = 5033; stage 1, n = 384; stage 2, n = 4000; stages 3 and 4, n = 649. B (a): total number, n = 20,164; stage 1, n = 2822; stage 2, n = 15,098; stages 3 and 4, n = 2244. B (b): total number, n = 15,712; stage 1, n = 2627; stage 2, n = 12,400; stage 3–4, n = 685. B (c): total number, n = 4452; stage 1, n = 339; stage 2, n = 3,538; stage 3–4, n = 575. PTW inverse probability of treatment weighting, HR Hazard ratio, 95% CI 95% confidence interval.

Discussion

This study showed that 84.5% of MASLD patients in the United States and 85.3% of patients in a Chinese population-based cohort were classified as CKM stage 2 or higher, respectively. CKM stages 3–4 were an independent risk factor for liver fibrosis in MASLD patients. A significant association was found between worsening CKM stage and increased risk of all-cause and CVD-related mortality across different subgroups.

The increased prevalence of CKM syndrome has been consistently increasing across different populations24. In the United States, CKM syndrome has affected more than 25% of adults, driven by increasing rates of obesity, diabetes, and hypertension25. Nearly 63.6% of U.S. adults met the criteria for CKM syndrome ≥ stage 226. In our study, the prevalence of CKM syndrome was significantly higher in MASLD patients compared to the general population.

Previous cohort studies have demonstrated that MASLD is independently associated with an elevated prevalence of CVD and CVD-related events27. In addition, many studies have suggested that MASLD might be an independent risk factor for CKD28,29,30. A meta-analysis enrolling 96,595 adults showed that MASLD is associated with a nearly 40% increase in incident CKD31. MASLD shares common features with CKM syndrome, and both of them have a myriad of metabolic risk factors, including obesity, hypertension, and T2DM32,33. The high overlap between MASLD and CKM syndrome contributes to the increased burden of CVD and related complications.

The cardiovascular, hepatic, and renal systems are intricately linked through shared pathophysiological mechanisms3. Acute or chronic disorders and derangements in one organ may adversely impact the function of the other two organs, with multiple bidirectional cause-effect relationships. Insulin resistance is one common underlying mechanism that contributes to the progression of CVD and renal injury in MASLD patients34. During insulin insulin-resistant state, insulin fails to suppress hepatic glucose production but promotes lipid synthesis, leading to hypertriglyceridemia and formation of atherosclerosis35. In addition, metabolic disturbances lead to immune activation in adipose tissue, with individuals typically exhibiting chronic low-grade inflammation36. In the inflammatory state, adipose tissue releases pro-inflammatory factors, such as tumor necrosis factor α, interleukin-6, and CRP, which trigger endothelial dysfunction37. Impairment of endothelial function is an early step in the atherosclerotic process, and thus critical to the development of CVD and CKD38. Moreover, inappropriate activation of the renin angiotensin aldosterone system is an important hormonal factor causing cardiovascular and renal injury in MASLD patients39. An epidemiological study demonstrated a clear correlation between elevated aldosterone levels and increased rates of CVD40.

As a multisystem disease, CVD and CKD are the core components of CKM syndrome, and together they constitute the main pathophysiological features of this syndrome. Progression along CKM stages is associated with increased relative and absolute risk for CVD, kidney failure, and mortality14. In our study, the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in MASLD patients gradually increased significantly as CKM stages worsened. Worsening renal function in patients with CVD is associated with a higher morbidity and mortality due to further derangement of the cardiovascular system41. This vicious cycle is particularly pronounced in MASLD patients, exacerbating the overall disease burden. Early identification and intervention in patients showing signs of CKM syndrome can help break the vicious cycle of worsening metabolic dysfunction, cardiovascular disease, and renal impairment. In addition, while elderly individuals are generally considered to be a high-risk group, our study found that with increasing cardiorenal syndrome stages, the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality was significantly higher in patients aged <60 years than in those aged ≥60 years. As individuals age, the function of various organ systems naturally declines, particularly the cardiovascular and renal systems, increasing the prevalence of CKM42. Unlike younger patients, in those over 60 years old, simple metabolic disturbances (CKM stages 0–2) posed limited threats to the mortality risk. However, the presence of very high-risk CKD or a high predicted risk of CVD (CKM stages 3–4) was still significantly associated with an increased risk of mortality, regardless of age.

Our study is strengthened by leveraging two large, population-based cohorts from distinct geographic regions and ethnic backgrounds—the U.S. NHANES cohort and the Chinese Kailuan cohort. NHANES represents a multi-ethnic U.S. population with greater racial/ethnic diversity, while the Kailuan cohort consists predominantly of middle-aged and older Chinese adults. The Kailuan cohort includes a relatively healthier and occupationally homogeneous population (industrial workers), with more uniform access to health care. In contrast, NHANES includes participants from a wide range of backgrounds. Considering potential differences in demographic characteristics, lifestyle factors, and healthcare systems, a validation cohort is crucial for ensuring the robustness and broader applicability of our results beyond a single dataset.

Despite the large sample size and extended follow-up period, several limitations of this study must be acknowledged. First, the baseline data for the US cohort were obtained between 1988 and 1994, which may not accurately reflect the contemporary prevalence of CKM stages in MASLD patients. Additionally, given that the Kailuan cohort is derived from a single city in northern China, the generalizability of our findings to the broader Chinese population may be limited. Further studies in more diverse populations are warranted to validate our observations. Second, all covariates were available only at baseline and were based on single–time measurements, so we could not capture changes in possible confounders over time during follow-up. Third, the lack of key data required to define advanced CKM stages—such as cardiac biomarkers, echocardiography, coronary angiography, cardiac computed tomography, atrial fibrillation, and peripheral artery disease—may have led to an underestimation of stages 3 and 4. Fourth, the reliance on self-reported medical history could introduce biases in estimating CKM stage prevalence. In addition, the lack of detailed information on medication use may introduce unmeasured confounding, potentially influencing the observed associations. Future studies with more comprehensive pharmacologic data are needed to clarify the role of these treatments in modifying CKM-related outcomes.

In conclusion, the majority of MASLD patients meet the criteria for CKM syndrome with ≥stage 2. CKM stages 3–4 are strongly and significantly associated with liver fibrosis in MASLD patients. All-cause mortality and cardiovascular-related mortality significantly increased with advancing CKM stages. CKM syndrome plays a critical role in the development of MASLD and MASLD-related liver fibrosis, requiring early identification and intervention of CKM syndrome in clinical practice.

Data availability

Data from the NHANES cohort are publicly accessible at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/. The Kailuan cohort was administered by the team of Professor Jingli Gao. Data from kailuan cohort are not publicly available due to the presence of potentially sensitive and politically related information, and can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request by emailing lijier@nju.edu.cn or tsgaojingli@163.com. The source data of NHANES III cohort are in Supplementary Data 1. The numerical data used to plot Figs. 2–4 are available in Supplementary Data 6, 10.

Code availability

The code used for data analysis is available on GitHub https://github.com/Zhu-Yixuan/MASLD-CKM.git.

References

Le, M. H. et al. 2019 Global NAFLD Prevalence: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 20, 2809–2817.e2828 (2022).

Li, J. et al. Prevalence, incidence, and outcome of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in Asia, 1999-2019: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 4, 389–398 (2019).

Byrne, C. D. & Targher, G. NAFLD: a multisystem disease. J. Hepatol. 62, S47–S64 (2015).

Targher, G., Byrne, C. D., Lonardo, A., Zoppini, G. & Barbui, C. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and risk of incident cardiovascular disease: A meta-analysis. J. Hepatol. 65, 589–600 (2016).

Targher, G., Byrne, C. D. & Tilg, H. NAFLD and increased risk of cardiovascular disease: clinical associations, pathophysiological mechanisms and pharmacological implications. Gut 69, 1691–1705 (2020).

Lee, E., Korf, H. & Vidal-Puig, A. An adipocentric perspective on the development and progression of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol. 78, 1048–1062 (2023).

Marcelin, G., Gautier, E. L. & Clément, K. Adipose Tissue Fibrosis in Obesity: Etiology and Challenges. Annu Rev. Physiol. 84, 135–155 (2022).

Neeland, I. J. et al. Visceral and ectopic fat, atherosclerosis, and cardiometabolic disease: a position statement. Lancet Diab. Endocrinol. 7, 715–725 (2019).

Ouchi, N., Parker, J. L., Lugus, J. J. & Walsh, K. Adipokines in inflammation and metabolic disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 11, 85–97 (2011).

Hutchison, A. L., Tavaglione, F., Romeo, S. & Charlton, M. Endocrine aspects of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD): Beyond insulin resistance. J. Hepatol. 79, 1524–1541 (2023).

Frostegård, J. Immunity, atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease. BMC Med. 11, 117 (2013).

Ormazabal, V. et al. Association between insulin resistance and the development of cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 17, 122 (2018).

Amdur, R. L. et al. Use of Measures of Inflammation and Kidney Function for Prediction of Atherosclerotic Vascular Disease Events and Death in Patients With CKD: Findings From the CRIC Study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 73, 344–353 (2019).

Ndumele, C. E. et al. A Synopsis of the Evidence for the Science and Clinical Management of Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic (CKM) Syndrome: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 148, 1636–1664 (2023).

Janota, O. et al. Metabolically “extremely unhealthy” obese and non-obese people with diabetes and the risk of cardiovascular adverse events: the Silesia Diabetes - Heart Project. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 23, 326 (2024).

Plan and operation of the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-94. Series 1: programs and collection procedures. Vital Health Stat. 1,1–407 (1994).

Yeo, Y. H. et al. Anthropometric Measures and Mortality Risk in Individuals With Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD): A Population-Based Cohort Study. Aliment Pharm. Ther. 62, 168–179 (2025).

Zhao, M. et al. Associations of Type 2 Diabetes Onset Age With Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality: The Kailuan Study. Diab. Care 44, 1426–1432 (2021).

Zhou, Y. F. et al. Effectiveness of a Workplace-Based, Multicomponent Hypertension Management Program in Real-World Practice: A Propensity-Matched Analysis. Hypertension 79, 230–240 (2022).

Rinella, M. E. et al. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. J. Hepatol. 79, 1542–1556 (2023).

Ndumele, C. E. et al. Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic Health: A Presidential Advisory From the American Heart Association. Circulation 148, 1606–1635 (2023).

KDIGO 2022 Clinical Practice Guideline for Diabetes Management in Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. 102, S1-s127 (2022).

Kjaergaard, M. et al. Using the ELF test, FIB-4 and NAFLD fibrosis score to screen the population for liver disease. J. Hepatol. 79, 277–286 (2023).

Khan, S. S. et al. Novel Prediction Equations for Absolute Risk Assessment of Total Cardiovascular Disease Incorporating Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic Health: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 148, 1982–2004 (2023).

Ostrominski, J. W. et al. Prevalence and Overlap of Cardiac, Renal, and Metabolic Conditions in US Adults, 1999-2020. JAMA Cardiol. 8, 1050–1060 (2023).

Aggarwal, R., Ostrominski, J. W. & Vaduganathan, M. Prevalence of Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic Syndrome Stages in US Adults, 2011-2020. Jama 331, 1858–1860 (2024).

Li, M., Wang, H., Zhang, X. J., Cai, J. & Li, H. NAFLD: An Emerging Causal Factor for Cardiovascular Disease. Physiol. (Bethesda) 38, 0 (2023).

Wang, T. Y. et al. Association of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease with kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 18, 259–268 (2022).

Cheung, A. & Ahmed, A. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Chronic Kidney Disease: A Review of Links and Risks. Clin. Exp. Gastroenterol. 14, 457–465 (2021).

Byrne, C. D. & Targher, G. NAFLD as a driver of chronic kidney disease. J. Hepatol. 72, 785–801 (2020).

Mantovani, A. et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease increases risk of incident chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Metabolism. 79, 64–76 (2018).

Qi, X., Li, J., Caussy, C., Teng, G. J. & Loomba, R. Epidemiology, screening, and co-management of type 2 diabetes mellitus and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Hepatology. [Online ahead of print] (2024).

Ma, X. et al. The impact of an increased Fibrosis-4 index and the severity of hepatic steatosis on mortality in individuals living with diabetes. Hepatol. Int. 18, 952–963 (2024).

Aroor, A. R., McKarns, S., Demarco, V. G., Jia, G. & Sowers, J. R. Maladaptive immune and inflammatory pathways lead to cardiovascular insulin resistance. Metabolism 62, 1543–1552 (2013).

Titchenell, P. M., Lazar, M. A. & Birnbaum, M. J. Unraveling the Regulation of Hepatic Metabolism by Insulin. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 28, 497–505 (2017).

Bremer, A. A., Devaraj, S., Afify, A. & Jialal, I. Adipose tissue dysregulation in patients with metabolic syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 96, E1782–E1788 (2011).

Andersen, C. J., Murphy, K. E. & Fernandez, M. L. Impact of Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome on Immunity. Adv. Nutr. 7, 66–75 (2016).

Vanhoutte, P. M. Endothelial dysfunction: the first step toward coronary arteriosclerosis. Circ. J. 73, 595–601 (2009).

Bender, S. B., McGraw, A. P., Jaffe, I. Z. & Sowers, J. R. Mineralocorticoid receptor-mediated vascular insulin resistance: an early contributor to diabetes-related vascular disease?. Diabetes 62, 313–319 (2013).

Milliez, P. et al. Evidence for an increased rate of cardiovascular events in patients with primary aldosteronism. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 45, 1243–1248 (2005).

Morcos, R. et al. The Healthy, Aging, and Diseased Kidney: Relationship with Cardiovascular Disease. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 69, 539–546 (2021).

Rex, N., Melk, A. & Schmitt, R. Cellular senescence and kidney aging. Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 137, 1805–1821 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82170609, 81970545), NSFC-RGC Forum for Young Scholars (No. 82411560273), and the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (No. BK20231118).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concept and design: J.L. and J.S.; Acquisition of data and technique support: Q.C., Y.Z., J.G., S.L., C.W., and X.Q.; Drafting manuscript: Q.C., Y.Z., W.N., F.R., X.B., N.G., R.J., Y.S., Z.F., and Y.C.; Critical revision of the manuscript: J.L. and J.S.; Access and verification of the underlying data: J.L.; All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Medicine thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Q., Zhu, Y., Gao, J. et al. Cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic (CKM) syndrome is associated with increased mortality in individuals with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). Commun Med 5, 492 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01195-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01195-w