Abstract

Background

Loudness hyperacusis may alter brain function beyond the discomfort elicited by regular sound levels. Yet, the neuroscientific literature of hyperacusis has largely focused on the sensory neural components, and often in the context of other comorbid conditions. Our goal was to investigate brain-wide neural interactions associated with loudness hyperacusis using resting-state fMRI and machine learning classification.

Methods

Fourteen young, healthy adults experiencing hyperacusis were recruited and compared to twenty-five age-, gender-, and education-matched control individuals. All participants had normal hearing thresholds and they were classified as having hyperacusis based on having a score greater than 22 on the Hyperacusis Questionnaire (HQ). Functional connectivity measures were used in a machine learning model that distinguished participants with hyperacusis from controls. Model weights were further analyzed systematically to reveal the cognitive brain networks and regional hubs where functional coupling was significantly altered in hyperacusis.

Results

Here, we observe that participants with hyperacusis are distinguishable from control individuals using a functional connectivity-based classification model, which yields a classification F1-score of 0.679. Owing to optimized feature selection, the model coefficients capture highly specific neural connectivity differences between the groups, including brain regions and networks implicated in semantic processing, working memory, emotion processing, and self-regulation. Furthermore, network connectivity measures, scaled by model-informed coefficients, explain up to 53% of the variance in individual HQ scores.

Conclusions

Through rigorous data-driven modeling, we characterize the reduced sound tolerance condition of loudness hyperacusis as being associated with atypical spontaneous connectivity across cognitive networks that extend beyond the auditory system. Such improved knowledge of the condition validates patient experiences and has implications for future treatments and assessments.

Plain Language Summary

When someone is sensitive to the loudness of everyday sounds that do not seem to affect those around them, we call it loudness hyperacusis. Often, hyperacusis affects activities of daily living and impacts psychological health. We compared brain differences using a type of brain imaging called MRI in young adults with hyperacusis and an age-matched control group without hyperacusis. Using advanced computational approaches, we measured differences in functional connections across a large number of brain regions. We found that individuals with loudness hyperacusis may process information from their senses differently, especially when it comes to attention and memory. Besides sound-attenuation strategies, treatments that address the brain’s meaning-making networks and emotional response to sounds could help those with hyperacusis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Poor tolerance towards sounds is one of the definitive behaviors for the disorder of hyperacusis1. Individuals suffering from hyperacusis perceive everyday regular sounds as too loud and react with adverse emotional, physical, and physiological responses2,3. Based on reactions to acoustic stimuli, finer subcategories are suggested - (1) loudness hyperacusis, where moderately loud sounds cause discomfort, (2) annoyance hyperacusis, where sounds evoke negative emotional reactions, (3) fear hyperacusis, where individuals seek avoidance, or show anticipatory response to sounds, and (4) pain hyperacusis, where individuals experience pain even at low sound levels4,5. Given the pronounced behavioral manifestations of hyperacusis, it is compelling to investigate its neural correlates within brain networks associated with cognitive and affective functions, particularly those involving the auditory, limbic, and attentional systems. In this study, we leveraged a comprehensive brain-wide network analysis to ascertain the altered cortical and subcortical connectivity profiles in loudness hyperacusis using rigorous machine learning methods. We focused on loudness hyperacusis5 alone and we use “hyperacusis” to indicate “loudness hyperacusis” for the remainder of the article.

Neuroscientific research on hyperacusis has largely been confined to neural activity within the sensory pathways of the auditory system6,7,8,9. Brain regions involved in early auditory processing have consistently shown hyperactivity when hyperacusis co-occurs with hearing loss and/or tinnitus, suggesting the engagement of compensatory mechanisms related to central auditory gain10,11,12. Beyond auditory regions, only a limited number of brain areas have been investigated for functional changes in hyperacusis, with most studies primarily employing task-based paradigms. For example, increased sound-evoked neural activity and/or connectivity have been reported in the striatum13, amygdala & hippocampus6,7,13, as well as the cerebellum and reticular formation6.

Although mechanisms of enhanced central auditory gain have been implicated in hyperacusis, reconfigurations in higher-order brain networks—whether as a consequence of central gain or through other processes—have not been adequately contextualized. Considering the psychological and behavioral symptoms associated with hyperacusis2, it is plausible that trait-like alterations in neural activity and connectivity extend across multiple cognitive networks. For instance, the emotion processing network (linked to adverse feelings elicited by sounds), the attention network (involved in orienting toward stimuli perceived as overly intense) and the default mode network (associated with affected psychological state) likely manifest abnormal neural communication patterns in hyperacusis. Yet, prior neural investigations have been largely confined to a narrow set of brain regions selected based on a priori hypotheses (example: central gain in auditory perception). As a result, these findings lack perspective of the broader functional reorganization that may occur in the brain in response to reduced sound tolerance. Moreover, studies of functional neural correlates of hyperacusis without co-occurring tinnitus and/or hearing loss are rare14 and remain largely unexplored in existing literature. Lastly, neural responses to sound stimuli have been well-characterized for hyperacusis in adults, typically in the context of comorbid tinnitus7,8, whereas few studies have investigated the effects on brain-wide intrinsic functional connectivity due to chronic loudness hyperacusis alone.

To address these gaps, we choose a well-defined, homogeneous cohort of subjects and apply a methodologically rigorous approach. During participant recruitment, we screen for mild to moderate cases of loudness hyperacusis, in the narrow age range of young college students. We minimize the confounding influences of aging and lifestyle, and also take into account plausible factors related to neurological, psychological, and auditory health, as well as other sound tolerance disorders (e.g., misophonia15,16). We analyze whole-brain resting-state functional connectivity and assess interactions among large-scale neural networks and between standardized functional regions of interest (ROIs) encompassing the entire cerebral cortex and subcortex. Given that whole-brain connectivity analysis substantially increases data dimensionality relative to conventional seed-based approaches, we adopt machine learning algorithms along with regularization techniques and identify robust, distinguishing patterns of network interactions associated with hyperacusis. We observe substantial contrasts in intrinsic functional connectivity related to emotion and cognitive processing between the two groups, and less so with auditory processing.

Methods

Participant recruitment and categorization

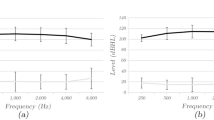

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign under protocol #IRB24 −1118, with risk level assessed to be minimal, and conforming to the standards set by the Declaration of Helsinki. An online survey was circulated among undergraduate population at the university between the ages of 18–25 and sampled roughly in a 50/50 sex distribution (Table 1). The participants gave informed consent for survey data usage in accordance with the university’s Institutional Review Board. Based on the responses and their willingness to be contacted, participants were recruited from the survey respondents for the in-person study and informed consent was obtained again for the remaining parts of the study. The survey included questions on demographics, Hyperacusis Questionnaire17 (HQ), and other psychological health questionnaires. A participant was considered to have hyperacusis if their HQ score was greater than or equal to 2218. Participants were also carefully screened for no likelihood of having misophonia using the diagnostic criteria proposed by Lewin et al. 19; this and fear or pain hyperacusis were evaluated through a semi-structured interview conducted by a clinical psychology doctoral student, and supervised by a clinical psychologist. None of the participants in the hyperacusis (HA) or control (CTR) groups had these other types of hyperacusis. Current depression symptom severity was also evaluated using clinician ratings on the Mood Episodes section of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-520. Pure-tone audiometry (PTA) tests were conducted across several frequencies (shown in Supplementary Fig. 1a). PTA profiles were matched between the hyperacusis and control groups, and also used to exclude participants with hearing loss (having average PTA across 0.5,1,2,4 KHz >=25 dB HL). In this article, we present our analyses and results based on the resting state functional MRI phase of the study for individuals in the HA (n = 14) and CTR (n = 25) groups.

Brain imaging

MRI acquisition

An MRI safety screening form and a consent form were filled out by the participants and reviewed by the MR technician before beginning scan acquisition. Resting state functional MRI data was acquired on a 3 T Siemens Prisma scanner with a 20-channel head coil for 10 min while the participant lay with eyes open, fixating on a cross at the center of the display screen. Double sound protection gear—ear plugs and MR-safe noise cancellation headphones—was employed to minimize possible discomfort due to continuous scanner noise. Participants were given the option to end the study at any time in case of any discomfort experienced in the scanner, sound-related or otherwise. A gradient echo-planar imaging sequence with transversal orientation (repetition time [TR] = 1500 ms, echo time [TE] = 30 ms, flip angle = 73°, 40 slices, voxel size = 3 × 3 × 3 mm3) was used to obtain functional MRI data. A total of 400 resting state volumes were acquired per participant. Additionally, a structural scan was obtained through a T1-weighted sagittal MPRAGE image (TR = 2300 ms, TE = 2.32 ms, flip angle = 8°, 192 slices, voxel size = 0.9 × 0.94 × 0.94 mm3) and was used for preprocessing functional resting state scans.

MRI data pre-processing

The anatomical and functional MRI data were organized participant-wise through BIDS structuring21 and pre-processed through fMRIprep pipeline22 using the default parameters. Briefly, the steps performed were (1) fieldmap estimation, (2) structural preprocessing including bias field correction, skull-stripping, tissue segmentation, surface reconstruction, spatial normalization to MNI-152 template, (3) functional preprocessing including reference volume generation, fieldmap alignment, slice-time correction, T1w co-registration, spatial smoothing with an isotropic Gaussian kernel of 6 mm full-width half-maximum, head-motion estimation and removal of outlier volumes. After preprocessing, the voxel-level time series were normalized by z-scoring.

Head motion and physiological parameters were found to be similar between the groups and therefore not included as covariates for pre-processing fMRI timeseries – see Supplementary Methods 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1b, c for more details.

Functional connectivity

Between brain regions

Normalized (z-scored) voxel time series were grouped and averaged as per Schaefer parcellation23 to obtain resting-state time series corresponding to 400 regions of interest (ROIs) spanning the cerebral cortex. Additionally, normalized time series for voxels in the subcortex were grouped and averaged as per Harvard-Oxford subcortical atlas to obtain timeseries corresponding to 14 subcortical ROIs (listed in Supplementary Data). Functional connectivity was measured between all pairs of ROIs (ROI-ROI FC) using Pearson’s correlation coefficient between the respective ROI time series. The FC matrix for a participant was symmetric and of dimension 414 × 414. Thus the lower triangle of FC matrix comprised of 85,491 functional connections which included the complete ROI-ROI FC battery for an individual. The diagonal of the matrix contained all 1 s by definition and was ignored.

Between region and whole brain

Functional connectivity of an ROI with whole-brain was measured by summing all 413 measures in the ROI-ROI FC matrix corresponding to a given ROI.

Between brain networks

The 400 ROIs of Schaefer atlas23 map onto one of seventeen functional networks defined by Yeo parcellation24 (Supplementary Data), which are subtypes within wider cognitive networks. We grouped the cortical ROIs into the eight broader networks among the 17 subtypes, namely Control (A,B,C), Default Mode (A,B,C), Dorsal Attention (A,B), Limbic (A,B), Salience/Ventral Attention (A,B), Somatomotor (A,B), Temporo-parietal, and Visual (A,B). The 14 subcortical ROIs were grouped as a separate (ninth) ‘Subcortex’ network. We measured the strength of functional connectivity among the 8 cortical networks and also the subcortex, by aggregating the ROI FC values corresponding to all regional connections, or FC edges, that existed between the networks. For a given participant, inter-network connectivity between two networks, N1 and N2, was measured by summing the FC estimates across all ROI-ROI edges linking N1 with N2. Similarly, intra-network connectivity for a network was measured by summing FC estimates across the ROI-ROI edges comprising the network. Thus network connectivity matrix for a given participant comprised of 36 between-network, and 9 within-network measures.

Machine learning classification

Datasets

For data augmentation, we divided the resting state fMRI session data for a given participant into two samples, with alternate volumes along time contributing to one sample. Thus, each participant’s data contributed two samples, or two sets of ROI FC matrices—FC1 and FC2 matrix of size 414 × 414 each. Each participant’s fMRI voxel data were downsampled based on alternate timepoints—voxel time points 1,3,7, etc. were normalized, grouped, and averaged along the 414 ROIs and used to estimate individual functional connectivity matrix (FC1; dimension: 414 × 414). Similarly, voxel time points 2,4,6, etc. were used to estimate additional matrix (FC2; dimension: 414×414). Since correlation-based measures do not depend on the temporal sequence of variables (ROI time series), the ROI timeseries could be downsampled as described, yielding two resting state FC measures per participant.

We compared FC matrices between participants to estimate the effects of downsampling. We calculated Pearson’s correlation values between participants’ FC battery (vector of connectivity values) from FC1, from FC2, and from ‘full-FC’ matrices (FC estimated on the entire resting state session data). We compared the distribution of correlation values for within-subject comparisons and between-subject comparisons using Welch’s two-sided t-tests, separately for the two groups.

With 14 participants in hyperacusis group and 25 in control group, combining FC1 and FC2 gave a total of 78 datapoints of multivariate ROI FC vectors. The dataset columns, i.e. ROI-ROI FCs, were normalized (z-scored) and used as the independent variables in the machine learning classification model, and a binary variable indicating participant group (0 for hyperacusis; 1 for controls) was used as the dependent variable. FC1 and FC2 data from 20% of individuals (chosen at random) from each group were used for hyperparameter optimization (HO dataset), and the data from remaining individuals was used for training the classification model (CT dataset).

Hyperparameter optimization

We implemented a multivariate logistic regression classifier model with elastic-net regularization, using sklearn.linear_model.LogisticRegression (v1.5.1) function with ‘class_weight’ set to ‘balanced’. We incorporated both L1- and L2-norm penalty terms; thus the model was tunable with two hyperparameters – strength of regularization, C, and L1-to-L2 ratio for balancing elastic net regression, L1_r. We iteratively varied both the parameters over a range of values, trained and tested the models using the fraction of data reserved for hyperparameter optimization (HO dataset; “Methods—Machine learning classification—Datasets”). We used a leave-one-out approach using the FC matrices in the HO dataset, where the test data contained both FC1 and FC2 of one participant from each group, and the train data contained remaining participants’ FC matrices. Thus, for each hyperparameter combination, independent repetitions of the model were trained, by iteratively leaving out pairs of subjects for testing. Value for C was varied from 0.001 to 0.1 in steps of 0.005, and L1_r from 0.01 to 0.2 in steps of 0.01. The classification performance corresponding to a given {C, L1_r} value combination was determined by aggregating all test data predictions from the leave-one-out repetitions. We also tracked the average number of variables that were assigned non-zero coefficients for a hyperparameter combination. The combination that yielded high F1-score with minimal difference between precision and recall, and utilized low number of FC variables, was chosen as the optimal hyperparameter pair in training the classification model.

Model training and accuracy evaluation

The classifier was trained on ROI-ROI FC to distinguish hyperacusis from controls, using a multivariate logistic regression model, with the hyperparameter values chosen based on the optimization procedure. The classifier was trained in leave-one-out repetitions using FC matrices from the CT dataset (“Methods—Machine learning classification—Datasets”) – where the test data contained both FC1 and FC2 of one participant from each group, and the train data contained remaining participants’ FC matrices. The classifier accuracy was obtained by combining the test data predictions across all leave-one-out repetitions. Precision, recall, and F1-score were calculated, considering correct hyperacusis predictions as true positives. Model coefficients were averaged across the independent repeated trainings and were analyzed as weights corresponding to the FC variables.

We generated a distribution of null accuracies by training the model with class labels shuffled in the train data. We obtained test accuracies for 500 null models (500 different permutations of training labels). Similar to classification model training, each null model was trained in leave-one-out repetitions, and evaluated by combining test predictions across the repetitions. The only difference in null model training was that the participant class labels in train data were permuted before training (with both FC1 and FC2 assigned the same label for a given participant). We compared the classification performances of the true model (obtained with original class labels) with the null models. P-value was estimated as (S + 1)/(number of permutations + 1) where S was the number of null accuracies greater than the true classification accuracy, and number of permutations was 500.

Statistical analysis

Group comparisons for the distributions of participant FC estimates (weighted/unweighted) were performed using two-sided Welch’s t-test, unless noted otherwise. These included comparisons on individual ROI-ROI FC edges, on sum of FC edges associated with individual ROIs, and on sum of FC edges associated with a network pair. For every family of comparisons, resulting p-values were corrected for multiple comparisons using Benjamini-Yekutieli25 procedure. Effect sizes were measured using Hedges’ g statistic, and 95% confidence intervals for g were determined with 10000 bootstrapped repetitions.

Reported correlation values were measured using Pearson’s r coefficient. Two-sided 95% confidence intervals (CI) for r were estimated non-parametrically with 10000 bootstrapped samples.

Results

Matched demographics and hearing profiles of individuals with and without hyperacusis

Recruited participants were students from a local university, ranging between 18 to 25 years in age, and categorized into two groups — hyperacusis (HA) and control (CTR) (“Methods—Participant recruitment and categorization”). The groups were comparable across attributes like age, sex, education, and hearing thresholds (PTA; Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1a). None of the participants reported having tinnitus. Audiological assessments showed significantly lower loudness discomfort levels (LDLs) in HA5 (\(p < 0.05\); Table 1). The groups also significantly differed in their Hyperacusis Questionnaire17 scores (HQ; Table 1), which assessed the presence and severity of hyperacusis. Symptoms of major depressive disorder (MDD) in the participants were below threshold and distributed comparably between the groups (Table 1).

Direct measures of functional connections among brain regions and cognitive networks

We acquired and pre-processed resting-state functional MRI scans for the participants in HA (n = 14) and CTR (n = 25) groups (“Methods—Brain imaging”). Average heart rate and head movement of participants did not show statistically significant differences between the groups (see “Methods—Brain imaging—MRI data pre-processing”, Supplementary Fig. 1b, c); moreover mean framewise displacement values for the participants were within the standard limit of 0.5mm26. We obtained individual functional connectivity matrices (FC) among 414 cortical and subcortical regions (ROIs) (Supplementary Data, “Methods—Functional connectivity—Between brain regions”). The median number of voxels per ROI was 92 (interquartile range: 57). Average individual FC matrices of HA and CTR were highly correlated (\(r=0.893,95 \% CI:0.891-0.894,p < 0.001\); Supplementary Fig. 2a). We compared the groups on (a) connectivity of the various ROI pairs (FC edges), and (b) net connectivity of an ROI with the whole brain (“Methods—Functional connectivity—Between region and whole brain”), and found no significant differences after correcting for multiple comparisons (\({p}_{corrected} > 0.05\); Supplementary Fig. 2b, c).

In addition to the spatially-defined brain regions, we assessed functional connectivity among large functional brain networks24, by aggregating the FC edges along network pairs (Supplementary Data; “Methods—Functional connectivity—Between brain networks”). Average network connectivity matrix of HA group was found to be highly correlated with that of CTR (\(r={{\rm{0.999,\; 95}}} \% CI:0.997-0.999;p < 0.001\); Supplementary Fig. 3a). Comparing estimates of connectivity within or between the networks showed no significant differences between the groups (\(p > 0.05\); Supplementary Fig. 3b). Thus, direct measures of neural interactions associated with isolated brain regions or with wider functional networks did not capture any deviations in intrinsic functional connectivity in hyperacusis.

Distinguishing presence of hyperacusis using multivariate classification model

Next, we used a multivariate machine learning approach to assess group classification with individual FC measures. We trained an elastic-net logistic regression model27 with FC edges as the predictor variables, and group label (HA/CTR) as the predicted variable.

First, to increase the dataset size for model training, we obtained two FC matrices for each participant (FC1 and FC2) based on alternate scans from their fMRI data (“Methods—Machine learning classification—Datasets”). This increased the effective TR to 3000 ms, which would not markedly affect the connectivity estimates28. We verified this empirically – FC matrices were highly correlated within participant, as opposed to the FC matrices of other participants within group (\(p < 0.001\); Supplementary Fig. 4). Thus, participant FC estimates remained highly consistent following downsampling.

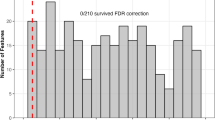

Next, we tuned the model hyperparameters using a small portion of the FC dataset (“Methods—Machine learning classification—Hyperparameter optimization”). The optimal value determined for regularization strength, C, was 0.021 and for penalty ratio, L1_r, was 0.08 (Supplementary Fig. 5). Using these hyperparameter values, we trained the classification model over independent repetitions, by leaving out pairs of subjects from the groups as test data (“Methods—Machine learning classification—Model training and accuracy evaluation”). Overall test classification F1-score was 0.679 (precision = 0.572, recall = 0.835; Fig. 1a). Importantly, the classification performance was statistically significantly higher compared to a distribution of null models (\(p < 0.01\), mean null F1-score = 0.575, precision= 0.509, recall = 0.661; Fig. 1b).

a Hyperacusis classification performance on test data of n = 209 leave-one-out model repetitions. Points represent scores for each model, bars represent the mean values. F1-score = 0.679 ( ± 0.021), precision = 0.572 ( ± 0.022), and recall = 0.835 ( ± 0.024). Error bars represent standard errors (standard deviation/no. of model repetitions) (b) Mean performance measures for 500 null models (histograms) compared against mean performance of true model (dashed lines) for F1-score (left panel; gray), precision (middle panel; blue), and recall (right panel; red). See “Methods—Machine learning classification—Model training and accuracy evaluation” for details.

Weighted functional connections among brain regions and cognitive networks

The model provided above-chance classification accuracy by exploiting the unified covariance in individual intrinsic brain connectivity. Owing to regularization, model training drove the coefficients to zero for 98.40 to 98.68% of the variables across training repetitions, thus effectively performing feature selection, and utilizing only a fraction of the FC edges for class prediction. Averaging coefficients across the models resulted in non-zero weights for 6112 edges (7.15%). The weights represented reliable evaluations on the group-discriminability of FC edges, as the high-valued coefficients were identified repeatedly and independently across several repetitions (Fig. 3). We elaborate further on this in a subsequent result.

Using the FC weights, we calculated weighted connectivity measures of ROIs with the whole brain and found significant group differences for 106 of 414 ROIs (\({p}_{corrected} < 0.05\); Hedges’ |g | > 1.003; Fig. 2a; Supplementary Fig. 6a); these ROIs were not anatomically or functionally clustered but were distributed across multiple cognitive networks and the subcortex.

a Classification model weights by ROIs. X-axis: ROIs arranged and color-coded by functional networks24 (Supplementary Data). Y-axis: Total weight (coefficient magnitude) summed across all FC edges associated with the ROI. Note break in axis. Welch’s two-sided t-test for group comparison of summed ROI connectivity was significant (pcorrected<0.05) for several ROIs – marked with open circles. See Supplementary Fig. 6a for effect sizes and p-values. b Weighted network connectivity matrices averaged for the two groups; Pearson’s r = 0.852, 95% CI [0.697 0.930]. C Control, D Default mode, A Dorsal Attention, L Limbic, S Salience/Ventral Attention, M Somatomotor, B Subcortex, T Temporal Parietal, V Visual. c Group comparison of weighted network connectivity measures using Welch’s two-sided t-test. Significantly different network pairs are highlighted with black dots for pcorrected < 0.05 and white circles for pcorrected < 0.001. See Supplementary Fig. 6b for effect sizes and p-values. d FC weights shown for Limbic network nodes, and e Default mode network nodes. Magnitude of FC coefficients were summed and sign was ignored. pcorrected values were corrected for multiple comparisons using Benjamini-Yekutieli25 method. OFC orbitofrontal cortex, Tem.Pole temporal pole, PFC prefrontal cortex, sgACC sub-genual anterior cingulate cortex, PHC parahippocampal cortex.

Next, we analyzed weighted network-to-network connectivity measures, by summing the weighted FC edges grouped by network pairs. Average weighted network connectivity matrix of the HA group was correlated with that of CTR with \(r=0.852\left(\right.95 \% CI:0.699-0.930;p < 0.001\); Fig. 2b), which was lower than the correlation for its unweighted counterpart (Supplementary Fig. 3a). Comparing measures between HA and CTR, between-network weighted-connectivity for 32 of 36 network pairs, as well as within-network weighted-connectivity for 6 of the 9 networks showed group distinctions (\({p}_{corrected} < 0.05\); Hedges’ |g | > 0.767; Fig. 2c black dots; Supplementary Fig. 6b).

Because a majority of the network pairs emerged statistically different between the groups, we further restricted the threshold alpha value. Our goal was to extract the characteristic connectivity signatures of hyperacusis; because the model precision was lower than the recall (Fig. 1a), we further minimized the likelihood of type-1 errors, i.e. mistaken identification of a group difference as significant for HA (albeit increasing type-2 errors). Applying a stricter statistical threshold of \({p}_{corrected} < 0.001\) did not eliminate the effects, rather highlighted many network connections with medium and large effect sizes (Hedges’ |g| between 0.698 and 2.428; Supplementary Fig. 6b). The effects were primarily driven by model weightage assigned to the limbic network and the default mode network (Fig. 2c white circles). Bulk of the limbic ROI connectivity weights were localized in the orbitofrontal cortex and the temporal poles (Fig. 2d), and for default mode ROIs in the para-hippocampal cortex, the sub-genual anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), and the dorso-medial prefrontal cortex (PFC) (Fig. 2e).

Brain connectedness discerning hyperacusis presence

Because the model was based on a monotonic (sigmoid) function and the FC variables were standardized (“Methods—Machine learning classification—Datasets”), FC weights (Fig. 3a, b) could be interpreted as relative contributions of the FC edges in driving accurate class identification. To determine the most distinguishing FC edges of hyperacusis, we compared mean and standard deviation for the coefficients obtained across training repetitions (Fig. 3c). 0.75% of the variables, or 645 FC edges, were assigned non-zero coefficients in atleast 70% of repetitions (Fig. 3b, c dark-colored data), indicating that the FCs were regularly recruited in the independently trained models. In addition, average coefficient for these particular FC edges had larger magnitude compared to the others (lay on right extreme of x-axis in Fig. 3b, c) or carried high weightage for classification prediction. Lastly, coefficients for these FCs showed low variance across the independent training repetitions (lay closer to or below the diagonal line of mean = standard deviation in Fig. 3c), meaning that the FC evaluations were consistent. Hence using model coefficients, we obtained a collection of FC edges that were relevant, reliable, and crucial in distinguishing brain connectivity of HA from CTR.

Average model coefficients assigned to FC variables – a sign matrix and b magnitude histograms shown for non-zero values only. Dark-colored histograms correspond to ‘consistently-weighted’ FC variables. c FC coefficients: mean and standard deviation across model repetitions, shown in log scale. Yellow dots: FC edges with a non-zero average coefficient. Green dots: ‘consistently-weighted’ FC edges, i.e., having non-zero coefficient across more than 70% of the independent training repetitions. Black dashed line: coefficient mean = coefficient standard deviation. d Correspondence between mean model coefficient sign (x-axis) and direction of FC effect size (Hedges’ g; y-axis) comparing HA with CTR. Each dot represents an FC edge. Legend: same as (c). Because the class variable was encoded as ‘0’ for HA and ‘1’ for CTR, positive coefficients corresponded to FC edges that showed decreased connectivity trend in HA compared to CTR, and vice-e-versa for negative coefficients.

We estimated weighted linear combination of FC for all participants, by including only the identified FC edges, and setting all other FC coefficients to zero. Weighted sum of only the highly-weighted FC edges showed no statistically significant difference compared to the full weighted FC (Wilcoxon signed rank p = 0.929; Pearson’s r = 0.999; Supplementary Fig. 7). Notably, the sign of FC weights were consistent with the direction of effect sizes for the (unweighted) FC measures between the groups (Fig. 3d), and hence could be interpreted as increasing (for negative coefficients) or decreasing (for positive coefficients) for HA compared to CTR.

Among the consistently highly-weighted FC edges (Fig. 3b-d dark-colored data), more than 50% were concentrated at a small number of ROIs, signifying these regions as key hubs of connectivity differences in HA (Table 2). Some of the highly-weighted FC edges were as follows. ROIs in bilateral occipito-temporal (fusiform) regions showed widely distributed patterns of decreased connectivity (in HA compared to CTR), namely – (1) connectivity of the left ROI with left visual processing areas (within fusiform gyrus and extrastriatal visual cortex), left supplementary motor area (SMA), left temporo-parietal junction (TPJ), right thalamus, and right amygdala (Fig. 4b left hemisphere); (2) ipsilateral connectivity of the right ROI largely with the salience network (insula), middle temporal gyrus (MTG), frontal eye fields (FEF), anterior/dorsolateral PFC, inferior frontal gyrus (IFG), and putamen (Fig. 4b right hemisphere).

FC weights (average model coefficients) shown for a all edges of auditory ROIs (ROIs are marked in yellow squares), and b–f consistently highly-weighted edges for key ROI hubs (see Table 2) marked in yellow squares. b Occipito-temporal/ fusiform areas, c Parahippocampal cortex (PHC), Globus Pallidus, and Nucleus Accumbens, d Orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) and inferior temporal gyrus (ITG)/ temporal poles (tp), e Anterior & Dorsolateral Prefrontal cortex (a.PFC/dlPFC), and f Superior parietal lobule (SPL). Threshold for panel (a) was chosen heuristically (see Supplementary Fig. 7a). Edges shown in (b–f) are thresholded at half-maximum FC weight for each ROI. (a–c) show ventral views, (d–f) show dorsal views. Left and right hemispheres are marked with L and R respectively.

In addition to reduced connectivity with the right fusiform and the left visual cortical areas, ROIs in the right anterior/dlPFC exhibited increased connectivity with right posterior insula (Fig. 4e right hemisphere). Left anterior PFC showed widespread decreased connectivity with parts of default mode network (precuneus, dmPFC), ventral attentional network (dlPFC, insula, dorsal ACC), right primary sensory cortex, IFG, right TPJ, and left primary auditory cortex (Fig. 4e left hemisphere). Interhemispheric connectivity between the left and right dlPFC was found to be generally diminished. An ROI in the left superior parietal lobule (SPL) showed increased connectivity with multiple regions across the visual cortex and with the orbitofrontal cortex, whereas an ROI in the right SPL showed decreased connectivity with left dlPFC and left SMA (Fig. 4f).

Limbic network ROIs in the right temporal pole showed reduced connectivity with left anterior/dlPFC, left MTG, right SMA, and ACC, but heightened connectivity with left insula, left IFG, and PCC/precuneus. Left temporal pole ROI also showed reduced connectivity with sub-genual ACC (Fig. 4d). Right orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) showed increased connectivity with left OFC, and decreased connectivity with right FEF, right insula, and bilateral anterior/dlPFC (Fig. 4d). The left parahippocampal cortex showed increased connectivity with right anterior PFC (Fig. 4c). Among the subcortical regions, the right pallidum showed increased connectivity with regions in the left visual cortex; right accumbens showed increased connectivity with PCC/precuneus, and decreased connectivity with left OFC (Fig. 4c).

Weighted connectivity of auditory cortex

Previous neuroimaging studies of hyperacusis in both animals and humans have extensively focused on neural changes among early auditory processing regions, in the brainstem and in the primary auditory cortex29,30. Given the scope of our analyses, we investigated neural connectivity in hyperacusis between the auditory cortex and other functionally higher brain regions that are crucial for complex cognitive processes. We selected seven ROIs with MNI co-ordinates coinciding with the auditory cortex (Supplementary Data). All FC edges incident at the auditory ROIs amounted to only 2.003% of the total FC weight across brain-wide connections. Edges with large weightage included connections linking (1) auditory regions in the right hemisphere with regions in the right occipito-temporal cortex, and in the left pre-motor and supplementary motor areas, and (2) auditory regions in the left hemisphere with left PFC (Fig. 4a; Supplementary Fig. 8a). At a network level, more than 41% of weightage associated with reduced auditory FC (positive coefficients) was observed for the coupling with somatomotor network (Supplementary Fig. 8b).

We measured weighted connectivity for the auditory ROIs with rest of the brain. Group comparison of net auditory cortex connectivity yielded a Welch’s t-statistic of -3.545 (\(p=0.0019\); Hedges’ |g | = 1.264, 95% CI [-2.09 -0.53]), which did not exceed the level of distinction attained by the several pairs of cortical networks (compare with Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 6b), implying relatively smaller effect of hyperacusis on auditory network connectivity compared to other broader functional reorganizations.

Correlation between individual hyperacusis score and network connectivity

We further investigated whether the model weights could, in addition to detecting hyperacusis, also account for the general variability in sound tolerance severity among participants from both the groups. We measured correlation values for HQ scores of the participants with weighted and unweighted network connectivity. With weighted measures, several network pairs correlated significantly with HQ scores (\({p}_{{{\rm{corrected}}}} < 0.05\); Pearson’s |r | > 0.428; Fig. 5a; Supplementary Fig. 9) and overlapped substantially with those that discerned group differences (Fig. 2c). Again, to minimize the risk of false positives, we chose a stronger threshold (\({p}_{{{\rm{corrected}}}} < 0.001\); Fig. 5a white circles) which resulted in network pairs whose correlations with HQ ranged between \(r\) = -0.604 to -0.728, or \({r}^{2}\)= 0.364 to 0.530 (correlation plots shown in Supplementary Fig. 10 in green). These pairs largely involved the frontoparietal control network, the default mode network, and the limbic network. With the unweighted or direct connectivity estimates, correlation values with HQ were much weaker and not significant (\({r}^{2}\)= 0.0002 to 0.0412; \(p > 0.05\); Fig. 5b; correlation plots shown in Supplementary Fig. 10 in magenta).

Pearson’s correlation between participant hyperacusis score (HQ17) and measures of model-weighted (left panel) and unweighted (right panel) network connectivity. Statistically significant correlation values (two-sided non-parametric test) are highlighted with black dots for pcorrected < 0.05 and white circles for pcorrected < 0.001. None of the correlations with unweighted FC were significant. 95% confidence intervals and p values are shown in Supplementary Fig. 9, and correlation plots in Supplementary Fig. 10. pcorrected values were corrected for multiple comparisons using Benjamini-Yekutieli25 method. Control: frontoparietal control, DMN: default mode, D. Attn: dorsal attention, Limbic: limbic network, Salien: salience/Ventral attention, SoMot: somatomotor, SubCx: subcortex, TemPar: temporo-parietal, Visual: visual network.

Weighting neural connections with machine learning-derived coefficients allowed the linear combination of functional connections to capture robust variance structure, which closely aligned with individual variability in the degree of loudness sensitivity. Systematic model-training using intrinsic brain connectivity data not only detected the presence of hyperacusis, but also explained the spread in participant hyperacusis scores.

Discussion

We investigated alterations in brain connectivity associated with loudness hyperacusis, using resting-state functional MRI acquired in a cohort of young adults. Individuals in the hyperacusis group were carefully matched with the control group on demographic variables and hearing thresholds, and expectedly differed in their loudness discomfort levels across stimuli comprised of various frequencies and speech sounds31,32. The hyperacusis group exhibited divergent spontaneous functional connectivity across large-scale networks, including the default mode, limbic, frontoparietal control, and somatomotor networks. Regions in these networks showed patterns of both enhanced and diminished functional connectivity that are discussed here.

Hyperacusis presents with persistent symptoms31 (rarely intermittent) and therefore maybe thought to induce neuroplastic changes and accompany functional rewiring in the brain. Although based on resting-state brain imaging, we interpret our results on network connectivity differences between the hyperacusis and control groups as atypical behavior traits across cognitive, social, and emotional domains33,34. Large proportion of model weightage was allotted to node connectivity in the default mode and limbic networks, aligning with previous findings in studies of hyperacusis, and in other auditory conditions marked by chronic aversion to sounds7,35,36,37,38 (e.g., tinnitus, misophonia). We interpret these results in the context of brain alterations associated with depression and anxiety in hyperacusis39,40,41, as these markers can potentially detect ‘at-risk’ individuals before symptoms worsen. Even though MDD rankings were below threshold for the participants in our study, strong connectivity alterations of limbic network nodes in medial OFC, and DMN nodes in dmPFC, as observed in HA, have generally been linked to rumination trait as a symptom of depression42,43. Disrupted dmPFC connectivity has psychopathological significance in first-episode MDD in young adults44, indicating a promising biomarker for the prognosis of psychological distress in younger population with mild to moderate hyperacusis45. In DMN, sub-genual ACC also showed aberrant connectivity in HA, consistent with the hypothesized predisposition for mood disorders46 in individuals with hyperacusis.

Additionally, we found altered connectivity at limbic network nodes in ITG/temporal poles, and DMN nodes in mPFC and PHC for the hyperacusis group. Trends in the former finding may affect processes of memory encoding and contextual associations47,48, while the latter could influence memory formations and retrieval in the context of binding social-affective information with perceived inputs49. We associate these neural connectivity differences in hyperacusis with possible alterations in mechanistic and cognitive traits underlying semantic processing.

Apart from hyperacusis presence, progressive effects of hyperacusis severity were clearly explained by the extent of connectivity disruptions involving the frontoparietal control and the somatomotor networks. In humans with hyperacusis, hyperactivity in the parietal context-switching areas50, and structural changes in motor regions51 presumably influence these connectivity trends and correspond to individual degree of loudness sensitivity as observed in our study. Moreover, connectivity of DMN and limbic networks, which manifested the presence of hyperacusis markers in brain-wide FC, also explained the variability along individual HQ scores. While HQ has been validated in several independent populations, these results interestingly highlight some of the neural bases for behavioral responses captured by HQ, i.e. attentional, social, and emotional subscales of hyperacusis17.

Localized connectivity reconfigurations in hyperacusis with respect to controls were found clustered at focal brain regions subserving fundamental cognitive processes—memory, attention and sensorimotor processing. Principal hubs of altered connectivity at the bilateral fusiform gyrus suggested evidence for significant alterations in semantic memory52,53,54; this compliments the parahippocampal patterns suggesting a skewed influence of contextual-memory on subsequent executive function55. Atypical and contrasting connectivity trends for SPL were indicative of enhanced visual/sensory-valuation along with reduced executive-sensorimotor integration56, and for anterior/dlPFC were indicative of aberrant top-down coordination, heightened executive–interoceptive coupling, and skewed somatosensory monitoring57,58. Shifts in globus pallidus connectivity (stronger visual links) also hint at altered gating of visual signal in sensorimotor coordination59,60. Lastly, differences in OFC and nucleus accumbens connectivities may represent impacted affect-valuation of sensory events due to sound sensitivity, as hyperexcitability of accumbens has been previously noted for noise-induced hyperacusis in animal models61. Together, these brain connectivity markers support neuropsychological models of hyperacusis where memory and attention are proposed as key cognitive factors linked to auditory behavioral outcomes62. Our findings also provide neural bases for some of the behavioral profiles described in a study by Sacchetto et al. 41, including altered somatic attention and hyper-awareness to bodily sensations in individuals with hyperacusis (and without tinnitus) when compared to age- and sex-matched controls.

Spontaneous functional coupling for the auditory cortex in hyperacusis was only modestly altered as compared to the other networks and regional hubs, possibly because all participants had normal hearing and were not engaged in auditory tasks during scanning. It is important to note here that previous studies that have reported enhanced auditory cortex activity were primarily based on explicit sound stimulation, or typically in a cohort experiencing chronic phantom auditory perception (tinnitus)7,8. However, lack of drastic effects in the intrinsic (resting-state) functional connectivity of auditory regions in hyperacusis suggests only modest alterations in trait-level auditory cortical interactions with higher processing areas.

In fact, with respect to auditory cortex coupling, larger disruptions were observed mainly with the somatomotor network. In light of these findings, we speculate that the central gain recruitment, which is widely theorized for hyperacusis10,11,12, need not result in severe or permanent changes to the fundamental auditory functional network architecture, even as hyperacusis appears to significantly rewire functional circuitry in extra-auditory areas. Our results provide rigorous evidence for substantial neural alterations in non-auditory regions and functional networks, and reinforce the need to focus on overall cognitive health in the context of treatment for loudness sensitivity31,63.

It must be noted that the hyperacusis participant sample in this study was based on highly selective criteria. Investigating the condition of hyperacusis in isolation from its comorbidities is essential to identifying divergence in behavior and function that are directly linked to loudness sensitivity. The limited heterogeneity of our sample reflects an inherent trade-off in our study design, aimed at isolating neural connectivity signatures that are especially characteristic of chronic sound sensitivity. We collected data from a clinically uncomplicated sample in order to avoid the significant neural confounds accompanying (1) broader age and demographic profiles, (2) hearing comorbidities like tinnitus and hearing loss7,8 (3) neurological comorbidities like autism spectrum disorder64,65 and (4) psychological factors like depression and anxiety which are highly prevalent in severe hyperacusis39,40. Additionally, participants in both the groups were college students leading broadly comparable lifestyles, including presumed exposure to similar environmental sound levels. Thus, taken together, the reported group differences in functional connectivity represent reshaping of cognitive mechanisms stemming directly from the presence of heightened sound sensitivity. However, as the HA group excluded severe cases (higher HQ scores) and broader age ranges, our results may not fully represent brain dysconnectivity patterns across the wider hyperacusis populations. Rather, we elucidate the neural coupling differences presenting due to sound sensitivity in our study sample, and facilitate future studies in better dissociation between the effects of hyperacusis from those of its co-occurring conditions like tinnitus, anxiety, or in different demographic contexts such as hyperacusis in older adults.

All participants with hyperacusis were able to complete the audiological assessments and MRI scanning sessions. We acknowledge the caveat of scanner noise that is present during resting-state data acquisition in fMRI. To mitigate the impact of sound presence, we used double ear protection—ear plugs and MR-safe noise cancellation headphones—which significantly reduced the noise levels. Such protection has shown to reduce the noise levels to below 70 dB SPL66. Moreover, none of the participants reported feeling uncomfortable due to the noise, nor chose to terminate the scanning session early. However, we did not conduct a debriefing immediately after the scanning session to determine if they experienced any changes in their hearing status or hyperacusis.

Lastly, the regularized machine learning classification model and its resulting coefficients were crucial in detecting the key brain connections that precisely distinguished hyperacusis. Leveraging multivariate classification algorithm facilitated a comprehensive exploratory assessment of whole-brain interactions spanning the cortex and the subcortex, thereby overcoming the limitations of traditional hypothesis-driven or seed-based analyses. Rigorous and optimized feature selection techniques and leave-one-out cross-validation allowed us to filter a vast number of candidate ROI pairs and reliably isolate a small fraction of key functional connections. Data-driven reweighting and combination of FC exhibited clear separation between hyperacusis and controls, which the unweighted connections failed to capture. To our knowledge, this is the first study to adapt a data-centric approach to map brain-wide intrinsic functional connectivity alterations of loudness hyperacusis.

Conclusion

Our study augments the sparse literature on brain-wide differences in loudness sensitivity (without tinnitus) that manifest beyond the auditory regions67,68. Among the many connectivity patterns that distinguished HA from CTR in our study, there was recurrent evidence for substantial alterations in memory processes and differential contributions from sensory information (auditory/visual/somatic) towards semantic memory processing. Very few studies have examined neural links between semantic memory impairment and hyperacusis68 and further research is required to validate whether these findings represent adaptive or maladaptive functional reorganizations in individuals afflicted with sound sensitivity.

With respect to characterization of hyperacusis, future research should link how these connectivity disruptions may underlie behavioral performance and likelihood for developing psychiatric comorbidities41. With regards to treatment, our findings support psychological interventions, such as cognitive behavioral therapy, which can help patients modify cognitive deviations, ruminations, and anxiety traits; this has been tested only sometimes for hyperacusis through randomized clinical trials69. For assessment of hyperacusis, psychological evaluations/questionnaires are being increasingly integrated39; cognitive evaluation focused on general attention and working memory performance (not just with respect to sounds) could also provide important information to evaluate the impact of loudness sensitivity on an individual.

Data availability

All source data associated with the results and figures are available on Figshare70 (URL: https://figshare.com/s/017e8c2fe4cabf2beffc). Due to participant privacy protection and ethical restrictions, participant details, audiological assessments and MRI data are not publicly available. De-identified participant data can be obtained from the corresponding author, Dr. Fatima T. Husain, upon reasonable request via email. Timeframe for response to data requests may be at most three weeks.

References

Aazh, H., Moore, B. C. J., Lammaing, K. & Cropley, M. Tinnitus and hyperacusis therapy in a uk national health service audiology department: patients’ evaluations of the effectiveness of treatments. Int. J. Audiol. 55, 514–522 (2016).

Adams, B. et al. A delphi survey to determine a definition and description of hyperacusis by clinician consensus. Int. J. Audiol. 60, 607–613 (2021).

Jastreboff, P. & Jastreboff, M. Treatments for decreased sound tolerance (Hyperacusis and Misophonia). Semin. Hearing 35, 105–120 (2014).

Tyler, R. S. et al. Tinnitus and Hyperacusis. Pp. 726–742 in Handbook of clinical audiology. (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2009).

Tyler, R. S. et al. A review of hyperacusis and future directions: part I. Definitions and manifestations. Am. J. Audiol. 23, 402–419 (2014).

Chen, Y.-C. et al. Tinnitus and hyperacusis involve hyperactivity and enhanced connectivity in auditory-limbic-arousal-cerebellar network. ELife 4, e06576 (2015).

Hofmeier, B. et al. 2021. Functional biomarkers that distinguish between tinnitus with and without hyperacusis. Clin. Transl. Med. 11. https://doi.org/10.1002/ctm2.378.

Koops, E. A. & van Dijk, P. Hyperacusis in tinnitus patients relates to enlarged subcortical and cortical responses to sound except at the tinnitus frequency. Hearing Res. 401, 108158 (2021).

Wong, E. et al. Functional magnetic resonance imaging of enhanced central auditory gain and electrophysiological correlates in a behavioral model of hyperacusis. Hearing Res. 389, 107908 (2020).

Auerbach, B. D., Rodrigues, P. V. & Salvi, R. J. 2014. “Central Gain Control in Tinnitus and Hyperacusis.” Frontiers in Neurology 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2014.00206.

Knipper, M. et al. Advances in the neurobiology of hearing disorders: recent developments regarding the basis of tinnitus and hyperacusis. Prog. Neurobiol. 111, 17–33 (2013).

Sheppard, A., Stocking, C., Ralli, M. & Salvi, R. A review of auditory gain, low-level noise and sound therapy for tinnitus and hyperacusis. Int. J. Audiol. 59, 5–15 (2020).

Chen, G.-D., Radziwon, K. E., Kashanian, N., Manohar, S. & Salvi, R. Salicylate-induced auditory perceptual disorders and plastic changes in nonclassical auditory centers in rats. Neural Plasticity 2014, 1–18 (2014).

Gu, J. W. et al. Tinnitus, diminished sound-level tolerance, and elevated auditory activity in humans with clinically normal hearing sensitivity. J. Neurophysiol. 104, 3361–3370 (2010).

Brennan, C. R. et al. Misophonia and hearing comorbidities in a collegiate population. Ear Hearing 45, 390–399 (2024).

Jastreboff, M. M. & Jastreboff, P. Component of decreased sound tolerance: hyperacusis, misophonia, phonophobia. ITHS N. Lett. 2, 5–7 (2001).

Khalfa, S. et al. Psychometric normalization of a hyperacusis questionnaire. ORL 64, 436–442 (2002).

Aazh, H. & Moore, B. C. J. Factors related to uncomfortable loudness levels for patients seen in a tinnitus and hyperacusis clinic. Int. J. Audiol. 56, 793–800 (2017).

Lewin, A. B., E. A. Storch, and T. K. Murphy. 2015. “Like nails on a chalkboard: a misophonia overview.” https://iocdf.org/expert-opinions/misophonia/.

First, M. B., Williams, J. B. W., Karg, R. S. & Spitzer, R. L. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Disorders.” Clinician Version (SCID-5-CV, (2015).

Gorgolewski, K. J. et al. The brain imaging data structure, a format for organizing and describing outputs of neuroimaging experiments. Sci. Data 3, 160044 (2016).

Esteban, O. et al. FMRIPrep: a robust preprocessing pipeline for functional MRI. Nat. Methods 16, 111–116 (2019).

Schaefer, A. et al. Local-global parcellation of the human cerebral cortex from intrinsic functional connectivity MRI. Cereb. Cortex 28, 3095–3114 (2018).

Thomas Yeo, B. T. et al. The organization of the human cerebral cortex estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. J. Neurophysiol. 106, 1125–1165 (2011).

Benjamini, Y., and D. Yekutieli. 2001. “The Control of the False Discovery Rate in Multiple Testing under Dependency.” The Annals of Statistics 29. https://doi.org/10.1214/aos/1013699998.

Power, J. D., Barnes, K. A., Snyder, A. Z., Schlaggar, B. L. & Petersen, S. E. Spurious but systematic correlations in functional connectivity mri networks arise from subject motion. NeuroImage 59, 2142–2154 (2012).

Zou, H. & Hastie, T. Regularization and variable selection via the elastic net. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B: Stat. Methodol. 67, 301–320 (2005).

Huotari, N. et al. 2019. “Sampling rate effects on resting state FMRI metrics.” Frontiers in Neuroscience 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2019.00279.

Eggermont, J. J. Hearing loss, hyperacusis, or tinnitus: what is modeled in animal research? Hearing Res. 295, 140–149 (2013).

Zeng, F.-G. Tinnitus and hyperacusis: central noise, gain and variance. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 18, 123–129 (2020).

Baguley, D. M. & Hoare, D. J. Hyperacusis: major research questions. Hno 66, 358–363 (2018).

Sheldrake, J., Diehl, P. U. & Schaette, R. Audiometric characteristics of hyperacusis patients. Front. Neurol. 6, 105 (2015).

Ajmera, S., Hritik Jain, M., Sundaresan & Sridharan, D. Decoding task-specific cognitive states with slow, directed functional networks in the human brain. Eneuro 7, ENEURO.0512-19.2019 (2020).

Liégeois, R. et al. Resting brain dynamics at different timescales capture distinct aspects of human behavior. Nat. Commun. 10, 2317 (2019).

Husain, F. T. & Schmidt, S. A. Using Resting State Functional Connectivity to Unravel Networks of Tinnitus. Hearing Res. 307, 153–162 (2014).

Kumar, S. et al. The brain basis for misophonia. Curr. Biol. 27, 527–533 (2017).

Rosemann, S. & Rauschecker, J. P. Disruptions of default mode network and precuneus connectivity associated with cognitive dysfunctions in tinnitus. Sci. Rep. 13, 5746 (2023).

Schröder, A. et al. Misophonia is associated with altered brain activity in the auditory cortex and salience network. Sci. Rep. 9, 7542 (2019).

Aazh, H. & Moore, B. C. Usefulness of self-report questionnaires for psychological assessment of patients with tinnitus and hyperacusis and patients’ views of the questionnaires. Int. J. Audiol. 56, 489–498 (2017).

Jüris, L., Andersson, G., Larsen, H. C. & Ekselius, L. Psychiatric comorbidity and personality traits in patients with hyperacusis. Int. J. Audiol. 52, 230–235 (2013).

Sacchetto, L. et al. Psychological profile and social behaviors of patients with hyperacusis. J. Clin. Med. 11, 7317 (2022).

Kim, J. et al. A dorsomedial prefrontal cortex-based dynamic functional connectivity model of rumination. Nat. Commun. 14, 3540 (2023).

Rolls, E. T., Cheng, W. & Feng, J. The orbitofrontal cortex: reward, emotion and depression. Brain Commun. 2, fcaa196 (2020).

Zhu, X., Zhu, Q., Shen, H., Liao, W. & Yuan, F. Rumination and default mode network subsystems connectivity in first-episode, drug-naive young patients with major depressive disorder. Sci. Rep. 7, 43105 (2017).

McLaughlin, K. A. & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. Rumination as a transdiagnostic factor in depression and anxiety. Behav. Res. Ther. 49, 186–193 (2011).

Philippi, C. L., Motzkin, J. C., Pujara, M. S. & Koenigs, M. Subclinical depression severity is associated with distinct patterns of functional connectivity for subregions of anterior cingulate cortex. J. Psychiatr. Res. 71, 103–111 (2015).

Van Kesteren, M. T., Rijpkema, M., Ruiter, D. J. & Fernández, G. Retrieval of associative information congruent with prior knowledge is related to increased medial prefrontal activity and connectivity. J. Neurosci. 30, 15888–15894 (2010).

Müller, N. C. et al. Medial prefrontal decoupling from the default mode network benefits memory. Neuroimage 210, 116543 (2020).

Olson, I. R., Plotzker, A. & Ezzyat, Y. The enigmatic temporal pole: a review of findings on social and emotional processing. Brain 130, 1718–1731 (2007).

Han, J. et al. Increased parietal circuit-breaker activity in delta frequency band and abnormal delta/theta band connectivity in salience network in hyperacusis subjects. Plos One 13, e0191858 (2018).

Makani, P., Koops, E. A., Pyott, S. J., van Dijk, P. & Thioux, M. Hyperacusis is associated with smaller gray matter volumes in the supplementary motor area. NeuroImage Clin. 38, 103425 (2023).

Forseth, K. J. et al. A lexical semantic hub for heteromodal naming in middle fusiform gyrus. Brain 141, 2112–2126 (2018).

Kassuba, T. et al. The left fusiform gyrus hosts trisensory representations of manipulable objects. NeuroImage 56, 1566–1577 (2011).

Snowden, J. S. et al. Semantic dementia and the left and right temporal lobes. Cortex 107, 188–203 (2018).

Aminoff, E. M., Kveraga, K. & Bar, M. The role of the parahippocampal cortex in cognition. Trends Cogn. Sci. 17, 379–390 (2013).

Corbetta, M. & Shulman, G. L. Control of goal-directed and stimulus-driven attention in the brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3, 201–215 (2002).

Dixon, M. L. et al. Heterogeneity within the frontoparietal control network and its relationship to the default and dorsal attention networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 115, E1598–E1607 (2018).

Menon, V. Large-scale brain networks and psychopathology: a unifying triple network model. Trends Cogn. Sci. 15, 483–506 (2011).

Dong, J., Hawes, S., Wu, J., Le, W. & Cai, H. Connectivity and functionality of the globus pallidus externa under normal conditions and Parkinson’s disease. Front. Neural Circuits 15, 645287 (2021).

Lanciego, J. L., Luquin, N. & Obeso, J. A. Functional neuroanatomy of the basal ganglia. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2, a009621 (2012).

Liu, Y., Alkharabsheh, A. A. & Sun, W. Hyperexcitability of the nucleus accumbens is involved in noise-induced hyperacusis. Neural Plasticity 2020, 8814858 (2020).

Wagenaar O., Wieringa M., Verschuure H. A cognitive model of tinnitus and hyperacusis; a clinical tool for patient information, appeasement and assessment. Int. Tinnitus J. 16, 66–72 (2020).

Aazh, H. et al. Insights from the third international conference on hyperacusis: causes, evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment. Noise Health 20, 162–170 (2018).

Williams, Z. J., Suzman, E. & Woynaroski, T. G. Prevalence of decreased sound tolerance (hyperacusis) in individuals with autism spectrum disorder: a meta-analysis. Ear Hearing 42, 1137–1150 (2021).

Danesh, A. A., Howery, S., Aazh, H., Kaf, W. & Eshraghi, A. A. Hyperacusis in autism spectrum disorders. Audiol. Res. 11, 547–556 (2021).

Husain, F. T. et al. Discrimination task reveals differences in neural bases of tinnitus and hearing impairment. PLoS ONE 6, e26639 (2011).

Hwang, J. H., Chou, P. H., Wu, C. W., Chen, J. H. & Liu, T. C. Brain activation in patients with idiopathic hyperacusis. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 30, 432–434 (2009).

Mahoney, C. J. et al. Structural neuroanatomy of tinnitus and hyperacusis in semantic dementia. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 82, 1274–1278 (2011).

Jüris, L., Andersson, G., Larsen, H. C. & Ekselius, L. Cognitive behaviour therapy for hyperacusis: a randomized controlled trial. Behav. Res. Ther. 54, 30–37 (2014).

Ajmera, S. (2025). Sparse machine learning on resting-state fMRI maps brain-wide dysconnectivity in hyperacusis. figshare. Dataset. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29482034.

Acknowledgements

This work was conducted in part at the Biomedical Imaging Center of the Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (UIUC-BI-BIC). We thank the MRI technicians Holly Keleher and Nancy Dodge for their help with MRI data acquisition. This research was supported by a grant from the Misophonia Research Fund (https://www.misophoniaresearchfund.org/) to Dr. Fatima T. Husain.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.A. contributed to MRI data acquisition, data analysis design and programming, writing of original manuscript draft, revising manuscript, visualization of results. R.A.K. contributed to MRI data acquisition, reviewed the manuscript. N.J. performed audiological data collection, reviewed the manuscript. G.K. performed audiological data collection. A.C. conducted psychological interview. H.B. contributed to conceptualization, supervised psychological interview, reviewed the manuscript, and provided intellectual support. F.T.H. contributed to conceptualization, supervised entire study, reviewed the manuscript, provided intellectual support, and contributed to acquisition of funds.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Medicine thanks Zhaopeng Tong and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ajmera, S., Khan, R.A., Jain, N. et al. Sparse machine learning of resting-state fMRI reveals brain-wide dysconnectivity in hyperacusis. Commun Med 6, 55 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01313-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-025-01313-8