Abstract

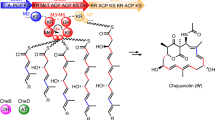

Polyketide synthases (PKSs) programme the assembly of polyketides that possess a wide range of pharmacological properties. In addition to assembly logic, carboxylic-acid-derived substrates underpin the structures and associated biological activities of these biosynthetically related natural products. Known type II PKSs exclusively use a malonyl extender unit for decarboxylative condensation and elongation, restricting the structural diversity. Based on investigations into the biosynthesis of siderochelins, a group of ferrous ion chelators, here we report a distinct five-component type II PKS that catalyses diketide formation and uses a methylmalonyl extender unit for condensation with the 3-hydroxypicolinyl starter unit during the formation of the pyrroline ring. Genome mining, gene inactivation, isotopic labelling and detailed biochemical characterization rationalize the capability of this type II PKS to use non-malonyl carboxylic substrates for starting and extending polyketide synthesis. The utility of this type II PKS is further recognized by its high compatibility with carboxylic acid substrate variation and by its ability to evolve to tolerate unnatural and/or unacceptable extenders.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data underlying the findings of this study are available in this Article and its Supplementary Information. The DNA sequence of the sid cluster has been deposited in GenBank with the accession number OR778683.1.

References

Hertweck, C. The biosynthetic logic of polyketide diversity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 4688–4716 (2009).

Shen, B. Polyketide biosynthesis beyond the type I, II and III polyketide synthase paradigms. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 7, 285–295 (2003).

Carreras, C. W., Pieper, R. & Khosla, C. Iterative polyketide synthases. Topics Curr. Chem. 188, 98–108 (1997).

Shen, B. Biosynthesis of aromatic polyketides. Topics Curr. Chem. 209, 1–51 (2000).

Hertweck, C., Luzhetskyy, A., Rebets, Y. & Bechthold, A. Type II polyketide synthases: gaining a deeper insight into enzymatic teamwork. Nat. Prod. Rep. 24, 162–190 (2007).

Rix, U., Fischer, C., Remsing, L. L. & Rohr, J. Modification of post-PKS tailoring steps through combinatorial biosynthesis. Nat. Prod. Rep. 19, 542–580 (2002).

Olano, C., Mendez, C. & Salas, J. A. Post-PKS tailoring steps in natural product-producing actinomycetes from the perspective of combinatorial biosynthesis. Nat. Prod. Rep. 27, 571–616 (2010).

Walsh, C. T. Polyketide and nonribosomal peptide antibiotics: modularity and versatility. Science 303, 1805–1810 (2004).

Walsh, C. T. & Fischbach, M. A. Natural Products version 2.0: connecting genes to molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 2469–2496 (2010).

Hillenmeyera, M. E. et al. Evolution of chemical diversity by coordinated gene swaps in type II polyketide gene clusters. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 13952–13957 (2015).

Chen, S., Zhang, C. & Zhang, L. Investigation of the molecular landscape of bacterial aromatic polyketides by global analysis of Type II polyketide synthases. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202202286m (2022).

Grammbitter, G. L. C. et al. An uncommon type II PKS catalyzes biosynthesis of aryl polyene pigments. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 16615–16623 (2019).

Du, D. et al. Structural basis for selectivity in a highly reducing type II polyketide synthase. Nat. Chem. Biol. 16, 776–782 (2020).

Deng, Z. et al. An unusual type II polyketide synthase system involved in cinnamoyl lipid biosynthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 153–158 (2021).

Shi, J. et al. In vitro reconstitution of cinnamoyl moiety reveals two distinct cyclases for benzene ring formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 7939–7948 (2022).

Moore, B. S. & Hertweck, C. Biosynthesis and attachment of novel bacterial polyketide synthase starter units. Nat. Prod. Rep. 19, 70–99 (2002).

Ray, L. & Moore, B. S. Recent advances in the biosynthesis of unusual polyketide synthase substrates. Nat. Prod. Rep. 33, 150–161 (2016).

Wilson, M. C. & Moore, B. S. Beyond ethylmalonyl-CoA: the functional role of crotonyl-CoA carboxylase/reductase homologs in expanding polyketide diversity. Nat. Prod. Rep. 29, 72–86 (2012).

Malpartida, F. & Hopwood, D. A. Molecular cloning of the whole biosynthetic pathway of a Streptomyces antibiotic and its expression in a heterologous host. Nature 309, 462–464 (1984).

Liu, W. C. et al. A new ferrous-ion chelating agent produced by Nocardia. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 34, 791–799 (1981).

Okuyama, D. et al. Isolation, racemization and absolute configuration of siderochelin A. J. Antibiot (Tokyo) 35, 1240–1242 (1982).

Lu, C. H., Ye, F. W. & Shen, Y. M. Siderochelins with anti-mycobacterial activity from Amycolatopsis sp. LZ149. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 13, 69–72 (2015).

Wells, J. S. et al. 3,4-Dihydro-4-hydroxy-5-(3-hydroxy-2-pyridinyl)-4-methyl-2H-pyrrole-2-carboxamide. US patent 4249008 (1981).

Wells, J. S. et al. Process for preparing antibiotic EM 4940. US patent 4339535 (1982).

Lee, D.-R. et al. Anti-multi drug resistant pathogen activity of siderochelin A, produced by a novel Amycolatopsis sp. KCTC 29142. Korean J. Microbiol. 52, 327–335 (2016).

Qu, X. D. et al. Caerulomycins and collismycins share a common paradigm for 2,2′-bipyridine biosynthesis via an unusual hybrid polyketide–peptide assembly logic. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 9038–9041 (2012).

Fu, P. et al. Acyclic congeners from Actinoalloteichus cyanogriseus provide insights into cyclic bipyridine glycoside formation. Org. Lett. 16, 4264–4267 (2014).

Chen, D., Zhao, Q. & Liu, W. Discovery of caerulomycin/collismycin‑type 2,2′‑bipyridine natural products in the genomic era. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 46, 459–468 (2019).

Born, Y. et al. Fe2+ chelator proferrorosamine A: a gene cluster of Erwinia rhapontici P45 involved in its synthesis and its impact on growth of Erwinia amylovora CFBP1430. Microbiology 162, 236–245 (2016).

Namwat, W., Kinoshita, H. & Nihira, T. Identification by heterologous expression and gene disruption of VisA as l-lysine 2-aminotransferase essential for virginiamycin S biosynthesis in Streptomyces virginiae. J. Bacteriol. 184, 4811–4818 (2002).

Huang, T. et al. Identification and characterization of the pyridomycin biosynthetic gene cluster of Streptomyces pyridomyceticus NRRL B-2517. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 20648–20657 (2011).

Yun, X. et al. In vitro reconstitution of the biosynthetic pathway of 3-hydroxypicolinic acid. Org. Biomol. Chem. 17, 454–460 (2019).

Cummings, M. et al. Assembling a plug-and-play production line for combinatorial biosynthesis of aromatic polyketides in Escherichia coli. PLoS Biol. 17, e3000347 (2019).

Liu, X. et al. Heterologous biosynthesis of type II polyketide products using E. coli. ACS Chem. Biol. 15, 1177–1183 (2020).

Quadri, L. E. N. et al. Characterization of Sfp, a Bacillus subtilis phosphopantetheinyl transferase for peptidyl carrier protein domains in peptide synthetases. Biochemistry 37, 1585–1595 (1998).

Pfeifer, B. A., Admiraal, S. J., Gramajo, H., Cane, D. E. & Khosla, C. Biosynthesis of complex polyketides in a metabolically engineered strain of E. coli. Science 291, 1790–1792 (2001).

Bumpus, S. B. & Kelleher, N. L. Accessing natural product biosynthetic processes by mass spectrometry. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 12, 475–482 (2008).

Pang, B. et al. Caerulomycin and collismycin antibiotics share a trans-acting flavoprotein-dependent assembly line for 2,2′-bipyridine formation. Nat. Commun. 12, 3124 (2021).

Guo, S. J. et al. Enzymatic α-ketothioester decarbonylation occurs in the assembly line of barbamide for skeleton editing. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 5017–5028 (2023).

Hitchman, T. S., Crosby, J., Byrom, K. J., Cox, R. J. & Simpson, T. J. Catalytic self-acylation of type II polyketide synthase acyl carrier proteins. Chem. Biol. 5, 35–47 (1998).

Yan, Y. et al. Multiplexing of combinatorial chemistry in antimycin biosynthesis: expansion of molecular diversity and utility. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 12308–12312 (2013).

Zhang, L. H. et al. Rational control of polyketide extender units by structure-based engineering of a crotonyl-CoA carboxylase/reductase in antimycin biosynthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 13462–13465 (2015).

Abramson, J. et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 630, 493–500 (2024).

Keatinge-Clay, A. T. et al. An antibiotic factory caught in action. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11, 888–893 (2004).

Bräuer, A. et al. Structural snapshots of the minimal PKS system responsible for octaketide biosynthesis. Nat. Chem. 12, 755–763 (2020).

Morris, G. M. et al. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 30, 2785–2791 (2009).

Trott, O. & Olson, A. J. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 31, 455–461 (2010).

Zhao, H. & Caflisch, A. Discovery of Zap70 inhibitors by high-throughput docking into a conformation of its kinase domain generated by molecular dynamics. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 23, 5721–5726 (2013).

Guerra, J. V. et al. ParKVFinder: a thread-level parallel approach in biomolecular cavity detection. SoftwareX 12, 100606 (2020).

Zeng, H. et al. Highly efficient editing of the actinorhodin polyketide chain length factor gene in Streptomyces coelicolor M145 using CRISPR/Cas9-CodA(sm) combined system. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 99, 10575–10585 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFC2303100) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32030002, 22193070 and 21621002).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Q., J.G. and M.C. performed the gene inactivation experiments. Y.Q. conducted the isotope-labelling studies. Y.Q. and J.G. carried out the biochemical experiments. Y.Q. and W.H. conducted the structural modelling and associated engineering studies. Y.Q., J.G., M.C., B.P., Z.T. and W.L. analysed and discussed the results. M.C., B.P., Z.T. and W.L. developed the hypothesis. Y.Q. and W.L. prepared the manuscript. W.L. designed and organized the research.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Synthesis thanks Sacha Pidot, Lihan Zhang and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Thomas West, in collaboration with the Nature Synthesis team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Biogenesis of proferrorosamine A.

(a) Comparation of the biosynthetic gene clusters of PFR-A and SIDs. (b) Proposed biosynthetic pathway of PFR-A29. The atom origins of the pyrroline unit (ring A) and associated precursors are indicated by different colours. PFR-A, proferrorosamine A; SID, siderochelin; AT, acyltransferase; KS, ketosynthase; CLF, chain length factor; ACP, acyl carrier protein; PKS, polyketide synthase; CoA, coenzyme A; PA, picolinic acid; PLP, pyridoxal phosphate; and ID, identity.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Multi-Angle Light Scattering analysis of the SidF–SidE complex in solution.

kDa, kilodalton; and Da, dalton.

Extended Data Fig. 3 In vitro determination of the selectivity of SidB between methylmalonyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA.

The S-acylation of SidD (ACP) for the formation of methylmalonyl-S-SidD and malonyl-S-SidD is shown above. Transformations were conducted by incubating the mixture of equimolar methylmalonyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA with Ppant-functionalized SidD in the absence (i) and presence (ii) of SidB (AT), respectively. The bar height represents the average amount of product formed from three independent replicates with the error bars representing the standard deviation. AT, acyltransferase; ACP, acyl carrier protein; CoA, coenzyme A; and Ppant, phosphopantetheinyl.

Extended Data Fig. 4 In vitro non-enzymatic formation of 3-HPA-S-SidD (ACP) and methylmalonyl-S-SidD.

Reaction mixtures were subjected to HPLC-HR-MS analysis after Glu-C digestion to determine the ratio between acylated SidD and holo-SidD. (a) Examination of 3-HPA-S-P2 and P2. Reactions were conducted in the mixture that contains SidD and 3-HPA-CoA. (b) Examination of methylmalonyl-S-P2 and P2. Reactions were conducted in the mixture that contains SidD and methylmalonyl-CoA. ACP, acyl carrier protein; 3-HPA, 3-Hydroxypicolinic acid; P, peptide; CoA, coenzyme A; HPLC, high performance liquid chromatography; HR, high resolution; MS, mass spectrometry; and NL, normalized level.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Examination of KS S-acylation by HPLC-HR-MS.

For the formation of methylmalonyl-S-SidF (KS) or propionyl-S-SidF, acylated P1 serves as the target sequence. (i), P1 (calculated 991.1811, found 991.1798 and error 1.31 ppm); (ii), propionyl-S-P1 (calculated 1009.8552, not observed); and (iii) methylmalonyl-S-P1 (calculated 1024.5185, not observed). KS, ketosynthase; P, peptide; CoA, coenzyme A; HPLC, high performance liquid chromatography; HR, high resolution; MS, mass spectrometry; EIC, extracted ion chromatogram; and NL, normalized level.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Quantification of SidBCDEF-catalysed, in vitro diketide formation.

The bar height represents the average amount of product formed from three independent replicates with the error bars representing the standard deviation.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Sequence alignment of SidF with selected KSs.

These KSs are involved in the biosynthesis of metathramycin (MmyP, QVQ68799.1), rubrolone (RubE8, AOZ61212.1), kosinostati (KstA1, AFJ52674.1), chartreusin (ChaA, CAH10161.1), saprolmycin (SprD, BAV16999.1), enterocin (EncA, QIC03940.1), whiE pigment (Orf III, CAA39408.1), colabomycin E (ColC4, AIL50166.1), aryl polyene (ApeO, 6QSP_A), youssoufene (YsfB, URG41680.1) and jadomycin (JadA, AAB36562.1). The conserved CHH motif was indicated by red star ( ). Four residues (that is, Phe136, Ala137, Pro235 and Leu362) that were unique to SidF were indicated by red triangle (

). Four residues (that is, Phe136, Ala137, Pro235 and Leu362) that were unique to SidF were indicated by red triangle ( ).

).

Extended Data Fig. 8 Phylogenetic analysis of SidE, SidF and their homologues.

The maximum likelihood method was used for tree construction. SidE and SidF were indicated by red star ( ). The units of the KS–CLF heterodimers AntD–AntE and Iga11–Iga12 were indicated by red triangle (

). The units of the KS–CLF heterodimers AntD–AntE and Iga11–Iga12 were indicated by red triangle ( ).

).

Extended Data Fig. 9 Structures of the KS–CLF heterodimer in complex with ACP.

(a) Modelling of SidD with SidF–SidE. The structural model was suggested by tools including AlphaFold 343. This predicted structure has a ptm value of 0.86 (>0.5, suggestive of an overall predicted fold of the complex that is similar to the true structure) and an iptm value of 0.85 (>0.8 indicative of a confident high-quality prediction in terms of the interfaces among the units SidD, SidE and SidF). Modelling with the ACP-channelled methylmalonyl extender was conducted using the tools Autodock and Ledock46,47,48. Autodock vina simulations were exhaustively (exhaustiveness = 8) run in a 12-12-20-Å box centred around the predicted pocket (8.5, 11.0, 9.0). The simulation in Ledock was also conducted based on the spatial parameters set by Autodock vina. The Ppant-S-methylmalonyl, SidD, SidE and SidF were shown in white, cyan, deepsalmon and pink, respectively. The reaction pocket structure was highlighted by black dashed line. (b) Reaction pocket in the SidDEF complex. The key active site residue (Leu362) is shown in magenta. (c) Superimposition of reaction pockets. The residues around methylmalonyl extender in SidF and Iga1213 are shown in pink and lightblue, respectively. The key active site residues (Leu362 in SidF and Phe395 in Iga11) are highlighted in red dashed line. KS, ketosynthase; CLF, chain length factor; ACP, acyl carrier protein; ptm, predicted template modelling; and iptm, interface predicted template modelling.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Active-site cavities shown in selected KS–CLF heterodimers.

ASCs were identified using the tool ParKVFinder49. Each heterodimer is composed of a KS unit (right) and a CLF unit (left). ASCs are indicated by shaded areas with different colours. The elongated intermediate in each cavity is shown. (a) ASC (red) in SidF–SidE. (b) ASC (blue) in Iga11–Iga12 (with the PDB ID number of 6KSD)13. (c) ASC (green) in AntD–AntE (with the PDB ID number of 6SMO)45. (d) Superimposition. The parts of the ASCs in the sides of the KS and CLF units are circulated with the black and red dashed lines, respectively. KS, ketosynthase; CLF, chain length factor; ACP, acyl carrier protein; ASC, Active-site cavity.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Text, Figs. 1–24, Tables 1–5, References and Uncropped scans of gels.

Supplementary Data 1

Source data for Supplementary Fig. 19.

Source data

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 6

Statistical source data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Qian, Y., Gao, J., Chen, M. et al. Analysis of siderochelin biosynthesis reveals that a type II polyketide synthase catalyses diketide formation. Nat. Synth 4, 219–232 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44160-024-00677-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44160-024-00677-4