Abstract

Silicon-based technologies have been researched extensively over the past few decades, but one ongoing problem has been bringing these technologies into the sub-THz regime. For wireless communications, these bands exhibit potential for massive improvements to bandwidth, data rates, etc., but overcoming the limits of operating frequency to allow devices to enter the sub-THz regime has proven challenging when designing working systems. Despite this, researchers have been developing novel ways to construct transceiver systems above 200 GHz. In this article, we showcase interesting designs that push the envelope towards more powerful, faster, and more useful silicon-based transceiver systems. We discuss transmitter systems grouped by modulation schemes as well as incoherent and coherent receiver systems. This allows us to point out the specific difficulties seen throughout these works and describe the direction needed to improve these systems. Finally, we discuss the future direction and application of silicon-based wireless communication systems as they move towards sub-THz regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

At this point in time, bridging the THz gap in wireless communications has potential for massive improvements for the field, especially in terms of data rates and latency1. Electronic devices (Transistors, Vacuum Tubes, etc.) tend to reach their maximum operating frequency (fmax) well below 1 THz, despite research in exotic materials trying to overcome this. Similarly, photonic devices (Lasers, LEDs, etc.) tend to operate at optical wavelengths, and research is still ongoing with respect to room temperature, high brightness Quantum Cascade Lasers that can operate around 1 THz2,3. That being said, there has been an ongoing push to fill this gap from about 0.1 THz to 10 THz, leaving us with the following questions: What is so interesting about this region? Why should electronic solutions be adopted? What work is being done to reach sub-THz? The following work is meant to address these questions, starting with how this region differs from lower frequencies.

Radio Frequency (RF) communication systems below 30 GHz, like WiFi and Bluetooth4,5, are extensively utilized due to their ability to cover long distances with minimal atmospheric attenuation, making them well-suited for applications like cellular networks, satellite communications6, and long-range wireless links. These lower frequencies often provide higher signal-to-noise ratios (SNR), allowing reliable signal reception over large distances. However, the widespread adoption of RF bands has resulted in congestion and limited available bandwidth7, restricting the capacity for high-speed data transmissions.

Sub-THz electronics, on the other hand, sacrifice range and SNR to address the need for higher data rates by offering significantly wider bandwidths8. Generally speaking, system bandwidth as a percentage of the center frequency tends to remain mostly constant regardless of the frequency, resulting in larger absolute bandwidths at higher frequencies9. This makes them an attractive option for emerging high-speed wireless communication systems, such as 6G and beyond. For example, the D-Band (130 to 174.8 GHz) is currently seeing significant development10,11,12,13 and is used for fixed service systems. However, one drawback for D-Band is that its allocations are fragmented into non-continuous segments (130–134 GHz, 141–148.5 GHz, 151.5–164 GHz, and 167–174.8 GHz)14. Fortunately, the IEEE 802.15.3d standard was recently adopted in 2017, specifying a high-data-rate wireless physical layer for the 252-325 GHz region while supporting an uninterrupted 44 GHz-wide band from 252 to 296 GHz, which also allows data rates up to 100 Gb/s15. For this reason, there has been recent research towards this 300 GHz band for applications in backhaul networks and consumer electronics, despite the device fmax limitations being much harsher than D-Band. In fact, output power in silicon technologies tends to reduce at a super-linear rate of f−3 1, limiting applications to short-range, high-capacity links, such as wireless backhaul, indoor communication, and high-speed data centers. In these environments, sub-THz can reach latencies and data rates far superior to RF systems for the same channel capacity. In addition to the available bandwidth, there are some extra benefits for this band. While radiated sub-THz waves are more susceptible to path loss and atmospheric absorption, which limits their effective range16, the 252–296 GHz band avoids resonant peaks and only suffers about 3 dB/km17. Additionally, higher frequencies miniaturize on-chip antennas, enabling the development of system-on-chip (SoC) phased arrays and multiple-input-multiple-output (MIMO) transceivers18.

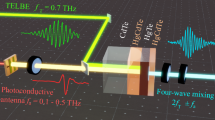

The generation and manipulation of sub-THz frequencies can be achieved using both electronic19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27 and optical28,29,30,31,32,33,34 approaches, each offering unique advantages and suited for different applications. Electronic sub-THz systems utilize high-frequency transistors, diodes, and integrated circuits based on semiconductor technologies such as silicon CMOS35, SiGe36, and III-V compounds (e.g. GaAs, InP, GaN)37, often times choosing a technology based on the transistor’s fmax. Because these systems are so close to fmax, unique techniques for generating sub-THz signals are employed, such as frequency multipliers22, harmonic generation, and direct oscillation using high-speed transistors coupled with resonant structures20,38,39. One primary advantage of electronic sub-THz systems over, for example, optical systems lies in their potential for compact, fully integrated designs, which can be fabricated using conventional semiconductor manufacturing processes. In fact, an entire system with a full antenna array can be as small as a few mm2. This compatibility for integration allows for efficient mass production as well as portability of the entire system.

Also, for electronic sub-THz frequencies above 200 GHz, hardware constraints inherent in THz transceivers, such as limited linearity, increased phase noise, and a restricted dynamic range, severely hinder the ability to accurately modulate both amplitude and phase simultaneously. This makes advanced schemes like Quadrature Amplitude Modulation (QAM), which rely on precise amplitude and phase constellation mapping, particularly vulnerable to errors and distortion40. In contrast, simpler modulation techniques such as Amplitude Modulation (AM), Frequency Modulation (FM), and Phase Modulation (PM), which require less stringent transceiver performance and are more robust to the imperfections of THz components, become more feasible choices for reliable wireless communication in this band. It should be noted that while mathematically many advanced modulation schemes can be viewed as combinations of fundamental modulation techniques (e.g., AM and PM), practically synthesizing them simultaneously and without distortion is a challenge. Despite this, the boost in data rates for these advanced schemes, as seen in Fig. 1, makes them highly sought after in the field41.

The solid, dashed, and dash-dot black curves are the Shannon-capacity ceilings \({C}_{\max }(f,d)\), while the light--tan area above the 10 m envelope marks the theoretically non--feasible region. Straight colored lines (Binary Phase Shift Keying (BPSK)–256 Quadrature Amplitude Modulated (QAM) \({\eta }_{{{\rm{mod}}}}=\{1,2,4,6,8\}\,{{\rm{bit}}}\,{{{\rm{s}}}}^{-1}\,{{{\rm{Hz}}}}^{-1}\)) show nominal raw data-rates. All calculations assume transmitted power of 20 dBm, transmit and receive antenna gain of 15 dBi each, and a receiver noise figure that rises linearly from 5 dB at 10 GHz to 20 dB at 300 GHz and remains flat beyond. Vertical dashed lines delineate two spectral windows: below half of the maximum frequency of power gain (fmax/2) (blue, encompassing the D-band) and above fmax/2 (primary focus of this work).

For the remainder of this article, we aim to showcase recent sub-THz electronic systems for communications, describe issues that are seen, and hopefully paint a picture of the future direction for improving systems and adapting them to useful applications. While many of these systems are transceivers, for the sake of this article, they will be categorized into transmitters and receivers, as each has its own challenges at hand.

Recent innovative designs in sub-THz transmitters

When it comes to sub-THz transmitters, all systems will suffer the issues described above (challenging signal generation, low output power, etc.). However, the modulation scheme chosen by the designer causes trade-offs in other specific ways, and so we will organize transmitters based on their modulation scheme, starting with Amplitude Modulation.

Amplitude Modulation

Modulating data symbols into different amplitude levels requires minimal hardware, as On-Off Keying (OOK) does not need a dedicated modulator, and a simple Digital-to-Analog Converter (DAC) can serve as an amplitude modulator. Due to the simplicity of the modulator design, amplitude modulation is often implemented directly at sub-THz frequencies rather than in baseband. For higher modulation orders, which provide increased throughput, a well-designed high On-Off ratio sub-THz switch is crucial to maintain SNR performance when transmitting signals at the lowest power levels.

In the early 2010s, Park et al. presented a 260 GHz CMOS OOK transmitter with a Voltage-Controlled Oscillator (VCO) and a balanced distributed modulator, which either shifts the power generated by the VCO to a Power Amplifier (PA) or to a dummy load42. Followed by the PA, there is a frequency quadrupler which converts the OOK-modulated data to 260 GHz (see Fig. 2a). The transmitter prototype consumes 688 mW. To reduce current consumption, Wang et. al later designed a 210 GHz fundamental oscillator to replace the power-hungry PA and the quadrupler, followed by a switch which functions as the OOK modulator. Benefiting from the efficient sub-THz fundamental oscillator, the overall power consumption was reduced to 240 mW43. Jiang et al. then extended the idea to a 12-core oscillator array which encodes the data symbols into four different amplitude levels and then further doubled the data rate by exploiting spatial orthogonality with orthogonally polarized on-chip antennas (See Fig. 2b). Due to the OFF-state parasitic capacitance at sub-THz frequencies, the measured ON-OFF range of four distinct power levels is lower than 10 dB, which limits the Bit Error Rate (BER) performance at high data rates44. To resolve the low ON-OFF ratio of the switch at sub-THz frequencies, Liang et al. implemented a high-Q surface wave resonator at 160 GHz, which provides 40 dB extinction ratio and thus enabled higher order amplitude modulation45. Along with high data rate applications, Garay et al. presented a 150 GHz regenerative 2 × 2 low-power transceiver array demonstrating a 10 Mb/s data rate with BER less than 10−5 at a distance of 70 cm while consuming 11.6/10 mW for the Transmitter/Receiver (Tx/Rx), respectively46.

a An On-Off Keying transceiver, reproduced with permission from Park et al.42. b A four-level dual-polarized Amplitude Shift Keying system, reproduced with permission from Jiang et al.44. c The architecture for a cryptographic transceiver, reproduced with permission from Lee et al.48. d An analog predistortion for a transmitter, reproduced with permission from Tang et al.49.

Recently, as intrinsic high-frequency performance metrics, like fmax, of advanced CMOS nodes (particularly FinFET technologies) have stagnated due to increased levels of parasitics, researchers have increasingly shifted focus from standalone sub-THz AM transceiver designs to more integrated systems with advanced on-chip features. Dolatsha et al. addressed the sub-THz transmitter’s packaging challenges and enhanced power coupling to free space by incorporating 3D-printed lenses into their OOK transmitter designs47. Lee et al. explored the use of sub-THz OOK transmitters for cryptographic authentication, achieving a record low power consumption of just 2.88 μW with a 264 GHz wake-up receiver48. Tang et al. pushed the boundaries by integrating analog pre-distorted power amplifiers with sub-THz AM transmitters, achieving an ultra-wide bandwidth from 90 GHz to 180 GHz - significantly outperforming earlier sub-THz designs that utilized only a narrow fraction of the carrier frequency49. These advancements underscore the potential to bridge the gap between academic research and practical applications in both high-speed data-rate communications and low-power Internet-of-Things connectivity.

Frequency modulation

Unlike AM, which encodes data into amplitude, FM encodes data into frequency. FM is generally considered to be more reliable than AM since the encoded data is not affected by amplitude variation due to path loss, multipath, etc. Additionally, current sub-THz communication systems tend to struggle with full bandwidth efficiencies and power consumption. If the bandwidth is already not fully being utilized, FM can improve power consumption at only a small tradeoff to data rate. This is largely due to the fact that FM can use more nonlinear power amplifiers, such as class C, as opposed to QAM, AM, etc., which require linear amplification, such as class A. So, if a system is aiming at data rate power efficiency, FM provides a lightweight solution compared to other schemes50.

In terms of conventional hardware implementation, FM can be realized from either synthesizer frequency switching or switching between different synthesizers. The first approach suffers from the settling time when switching between bits, while the second requires extra area proportional to the number of bits. Due to these limitations, FM is rarely explored in sub-THz wireless transceivers where the bit rate could exceed the settling time or the area is important. To address the bottleneck of long frequency shift settling times in conventional FM hardware, Chen et al. proposed a coupled-oscillator-based Frequency Shift-Keying (FSK) transmitter architecture (see Fig. 3a). Compared to the conventional implementation where the design load was put on the synthesizer side, the proposed coupled oscillator architecture utilizes phase shifters (Fig. 3b) in between the oscillator cores to modulate the data. Due to the Barkhausen criteria, this extra phase results in the oscillator’s frequency shifting to reach a loop phase shift of 2nπ. Interestingly, Chen then showed that this frequency shift settles much faster than a traditional VCO, largely because the phase shift has been separated from the oscillator core51.

a A description of the settling time of an injection locked oscillator vs coupled oscillators, reproduced with permission from Chen et al.51. b The phase shifters from the same work, reproduced with permission from Chen et al.51. c An example 4-symbol Frequency Shift Keying Transmitter, reproduced with permission from Afzal et al.52. d A PIN diode-based transmitter, reproduced with permission from Razavian et al.53.

Recently, Afzal et al. moved one step further by extending the modulation into 4FSK. To do so, they revisited a more conventional technique of using switched varactors (see Fig. 3c), which, while having a slower settling time than the coupled oscillator system, was still fast enough for their target 17 Gb/s data rate at 165 GHz52. Additionally, Razavian et al. pushed their FSK transceiver’s frequency to 400 GHz by relying on a PIN diode for frequency multiplication and the transistor biasings for frequency switching (see Fig. 3d). While switching the biasing potentially moves the oscillator away from the ideal bias, it does show one way to avoid using lossy varactors, which tend to seriously impede sub-THz systems. Though the achieved data rate is lower than the other works discussed here, considering the required time for a PIN diode’s operation mode change, they managed to demonstrate a wireless link at a distance of 20 meters, which is among the highest at these frequencies53.

These works help FM stand out for its low-power and high-reliability characteristics despite its lower channel efficiency. Given that most current exploratory work focuses on the transmitter side and is incoherent, developing over-the-air injection-locked receiver systems and sub-THz Phase Locked Loops (PLL) will be an important next step towards enabling higher-order FM communications.

Phase modulation

PM is a digital modulation technique that encodes data into the phase of a carrier signal. Compared to the previous schemes, PM offers similar spectral efficiency as AM while keeping a constant carrier envelope as in FM. However, this scheme requires more complicated circuitry since encoding data into phase accurately and demodulating this phase coherently is an exceptional problem at sub-THz frequencies. Additionally, for Quadrature Phase Shift Keying (QPSK), generating accurate quadrature signals has been a focus for some research.

One typical issue with modulating PM architectures is minimizing the power loss of the modulator, especially when sub-THz oscillators have low output power to begin with. Recent advancements have improved on-chip modulators and antennas to minimize losses and enhance power output efficiency. Chen et al. demonstrated a low-power Binary Phase Shift Keying (BPSK) transmitter, shown in Fig. 4a, which makes use of a unique coupled oscillator and BPSK modulator54. This modulator works by manipulating transmission line impedance transformations with shunt bipolar switches to steer oscillator power based on constructive phase interference, resulting in 2 dB modulator loss. This low-loss transmitter achieved up to 40 Gb/s at 196 GHz.

a A low-loss Binary Phase Shift Keying modulator at 196 GHz, reproduced with permission from Chen et al.54. b An 8-symbol Phase Shift Keying modulator using direct modulation and high-speed phase shifters, reproduced with permission from Nazari et al.55. c A diagram of the switched phase shifters for phase modulating the signal, reproduced with permission from Nazari et al.55. d Example transmit and receive antennas utilizing polarization orthogonality for Multiple-Input-Multiple-Output operation, reproduced from Rodríguez-Vázquez et al.56. e Constellation visualization of strong and weak leakage from right- to left-handed circular polarization and vice versa. The main causes of the leakage are antenna cross-polarization and leakage inside the transmitter-receiver circuitry, reproduced from Rodríguez-Vázquez et al.56.

In a multiplier-based architecture, Nazari et al. presented an 8PSK transmitter at 170 GHz with direct modulation, which reached 15 Gb/s55. A key advantage of this architecture is that the signal is split into I and Q before the modulator, as amplification is much simpler at 57 GHz instead of the transmitted 170 GHz. The proposed architecture, as seen in Fig. 4b, uses high-speed switched phase shifters (SPS) and over-neutralized power amplifiers to increase the modulation order to 8PSK. These SPS blocks, shown in Fig. 4c, were also driven by an on-chip Pseudo-Random Binary Sequence (PRBS) generator. The outputs are mixed and amplified by power amplifiers, which drive a 1 × 2 antenna array, boosting output power and Effective Isotropic Radiated Power (EIRP).

In addition to single antenna radiators, there have been demonstrations of Multiple Input Multiple Output (MIMO) systems capable of transmitting and receiving QPSK signals. One MIMO system is demonstrated by Rodríguez-Vázquez et al.56. This system utilizes Right-Hand and Left-Hand circular polarization (RHCP & LHCP) as orthogonal channels. As can be seen in Fig. 4d, the slot antenna utilized in this design generates RHCP and LHCP using two signals with a 90∘ phase difference, which, despite the leakage seen in Fig. 4e, was suitable for increasing the channel capacity. The transmitter is a multiplier chain followed by power amplifier stages to help meet the link budget for a 1-meter distance.

While these recent works in phase modulation architectures show improvements to spectral efficiency, output power, and integration at sub-THz frequencies, several challenges remain. Encoding and decoding phase information at these high frequencies with acceptable distortion will require further optimization or potentially new techniques, particularly for reducing phase noise and improving quadrature signal generation. Future research on minimizing modulator losses and increasing output power will also be key for future PM-related improvements.

Quadrature amplitude modulation

Quadrature Amplitude Modulation (QAM) offers multiple benefits compared to simple AM, such as higher spectral efficiency, but this technique usually results in complex design challenges, especially when operating at high frequencies. For transmitters, it is necessary to synthesize an in-phase and a quadrature signal, modulate both, and then radiate their sum, and most solutions to these come at a cost for high-frequency operation. An oscillator can sacrifice tuning range and phase noise performance to forcibly generate a quadrature output, while couplers take up space and have a trade-off between bandwidth and loss. Generally, it is preferable to modulate a low-frequency signal and upconvert to high frequency, but this is not feasible for quadrature modulation with high spectral content, and also broadens the required bandwidth. However, designing a low-loss modulator at frequencies near fmax is difficult with conventional mixer topologies. Additionally, summing two wide-band signals can be done with transformers, microwave combiners, or constructive interference in space, but these all take up massive amounts of space and result in loss for an already low-power signal.

Despite these inherent design issues, the benefit to spectral efficiency still pushes for innovation in this area. In 2019, Lee et al. presented an 80 Gb/s 16QAM transceiver operating at 300 GHz57. A typical multiplier chain feeding on-chip quadrature hybrids was used to generate the Local Oscillator (LO), but a unique design was used for the modulation. A semi-balanced quadrature mixer was used to intentionally leak the LO and generate an Intermediate Frequency (IF) (see Fig. 5a), which was then squared and fed into a double-rat-race coupler (see Fig. 5b). The rat-race coupler allows separate Tx and Rx modes by combining the data and rejecting LO for Tx and vice-versa for Rx (see Fig. 5c). Additionally, the double-rat-race increased output power by combining the Tx chain with an inverted copy of itself. The efficiency of 22.4 pJ/bit does not show the state of the art compared to other modulation schemes, but the data rate of 80 Gb/s with only 16QAM shows potential.

a The semi-balanced mixer meant to leak the local oscillator (LO), reproduced with permission from Lee et al.57. b The method used to reuse the transmitter LO for the receiver circuit, reproduced with permission from Lee et al.57. c The double-rat-race coupler for power combining and choosing the transmit or receive mode, reproduced with permission from Lee et al.57. d The signal vectors needed for conventional Quadrature Amplitude Modulation (QAM) vs Outphasing QAM58. e The non-isolating power combiner and radiator, reproduced with permission from Standaert et al.58. f The modulator and 15-stage power amplifier, reproduced with permission from Wang et al.60. g The packaging used for the 2D 64-element array, reproduced with permission from Wang et al.60.

Usually, sub-THz transmitters use mixers or multipliers at the end of the chain to upconvert to the desired frequency. Standaert et al. showed that harmonic outphasing (see Fig. 5d) could be a method to improve the multiplier-last architectures by driving the PAs with phase-modulated signals and keeping them at the optimal drive for efficiency. To show this, they produced a transmitter at 390 GHz, which is above fmax58. Despite the lower data rate achieved in this specific work, the argument that this technique reduces distortion is still valid and possibly a valuable solution to reaching more complicated modulation schemes at extremely high frequencies. Additionally, they combined the signals using a non-isolating combiner, which can also radiate. The combiner has been shown to be efficient for this operation59, although the antenna is only capable of radiating the out-of-phase components (see Fig. 5e).

In 2024, Wang et al. showcased a transmitter capable of 16 and 32QAM at about 250 GHz60. Their design shows the difficulty of amplifier-last architectures at these frequencies in that after optimizing the input/output impedances and tuning the gain of each stage to have two peaks for wideband amplification, they still needed a 15-stage PA (see Fig. 5f) to achieve above 20 dB gain and -8 dBm output power. This challenge is simply due to the previously stated problems when nearing fmax. However, they then showcase a great strength of this frequency band by turning their design into a 2D phased array. Due to the small wavelength, each chip fits four Vivaldi antennas, which is an interesting topology for making a compact array using stacked Printed Circuit Boards (PCBs). Overall, they fit 64 antennas as a 2D array into about a 1.1 x 0.2 cm2 area (see Fig. 5g). It is possible that designs like this will be key for overcoming low output power at these frequencies.

At present, multiple works have been done at D-band (110–170 GHz) as well for QAM11,61,62,63, showing promising results for increasing modulation complexities with extremely high channel capacities. However, many of these types of systems struggle above fmax/2 largely due to the lack of gain and output power above D-band. As these systems improve, it is likely that they too will increase modulation complexities so that they can outperform lower frequency systems.

Recent innovative designs in Sub-THz receivers

Broadly speaking, sub-THz receivers are a bottleneck of transceiver systems, with the primary challenges being SNR and coherence. Because the systems are pushing the limits of the device fmax, amplification of the carrier frequency becomes difficult in many cases. So, most receivers are left deciding between two poor choices - having a noisy, low-gain amplifier chain or having a noisy, lossy mixer-first chain. Both cases cause significant noise detriments compared with traditional architectures. One compromise seen recently in sub-THz designs is to use sub-harmonic mixers, which alleviate the lossy nature of high-frequency LO requirements at the cost of noise and potential interference. Additionally, due to the difficulty of creating a powerful, low-phase noise, low-frequency drift signal on chip, achieving coherence becomes a difficult procedure. The following section will showcase ways in which researchers are developing incoherent and coherent receivers.

Incoherent methods

The simplest form of incoherent reception is direct detection, in which the intensity of the electric field is converted directly to a current or voltage, and this method is usually the simplest for characterizing transmitters when coherency is not necessary. For sub-THz works, this is typically implemented via an ultra-wideband photodiode (often a Schottky Barrier Diode) with high sensitivity, low noise equivalent power (NEP), and a high-gain antenna. It is common to see this setup used in both electronics and optics, but while these tend to use discrete components, work has been done to integrate this receiver style onto CMOS. To do so, researchers create antenna-coupled transistor detectors, in which an integrated antenna directly feeds a MOSFET (or similar)64,65,66,67,68. As an example, if an antenna is connected to the source and gate of a transistor and feeds it a sub-THz signal, the signal will self-rectify and produce a DC voltage from source to drain if the channel is long enough to attenuate the impinging signal (see Fig. 6a)69,70.

a Self-rectification via an antenna-coupled field-effect transistor. b An example optimization for a direct-detector, reproduced with permission from Lee et al.48. c A receiver with cascaded phase-locked loops, reproduced with permission from Memioglu73. d A sliding-intermediate-frequency superheterodyne receiver, reproduced with permission from Li et al.74. e A receiver featuring Hartley image rejection, reproduced from Abdo75. f A chip to printed circuit board interface for connecting to a WR-3.4 rectangular waveguide, reproduced from Hara et al.76. g A generic Kramer’s -Kronig Receiver, similar to Ghozzy and Allam’s design77.

An example of this can be seen in Ferreras et al.’s work, in which a receive antenna is directly connected to a FET, which senses and outputs the signal65. This specific work achieved an NEP of \(50\,pW/\sqrt{Hz}\) at 0.84–1.29 THz in CMOS. For perspective, a non-integrated Schottky Diode Photodector from a commercial company achieves about \(27.1\,pW/\sqrt{Hz}\) at 0.75–1.1 THz71. For more examples in the sub-THz regime, \(1.9\,pW/\sqrt{Hz}\) NEP and 9kV/W responsivity (electrical output per optical input) was achieved at 292 GHz in SiGe68, and \(3.5\,pW/\sqrt{Hz}\) NEP and 2kV/W responsivity at 315 GHz was achieved in CMOS72.

To date, most of these examples of CMOS detectors are discussed in the context of imaging, but this self-rectification could also be used for demodulating non-coherent schemes. One example of such a CMOS detector used for communications at 264 GHz is seen in Lee et al.’s work48. In this work, a detector receiver was chosen primarily for its low-power characteristic as part of a wake-up receiver, and the authors decided to feed the detectors with two antennas to provide a more optimal ratio of signal at the gate to signal at the drain (see Fig. 6b).

Coherent methods

Despite the simplicity of the previous incoherent strategies, coherent detection is important for any system that requires phase information. To do so, a local oscillator is needed, requiring the need for either multipliers or PLLs, which can be lossy, difficult to design, and difficult for maintaining coherency. One such example of a 300 GHz receiver is seen in Memioglu’s work73, in which the authors chose a heterodyne architecture with three PLLs. They show that having cascaded PLLs offered benefits to phase noise and power consumption. By using a heterodyne system, they were also able to avoid having two mixers at the start of the chain and then implement an IF amplifier as well as quadrature mixers at lower frequencies. With this architecture seen in Fig. 6c, they achieved 18 dB gain, 20 dB Noise Figure, and 52 mW DC power consumption.

Conversely, a 220 GHz receiver architecture based on multipliers can be seen in Li et al.’s work74. They focused on a sliding IF superheterodyne architecture in which a fundamental LO, as well as its third harmonic, are used to up/down-convert to/from RF (see Fig. 6d). As such, their LO generation circuit is simpler than the previous example, but struggles to maintain high output power and low power consumption as it goes through two tripler circuits. Their NF was under 13.8 dB, but their power consumption was 495 mW.

Another strategy that is being employed to alleviate LO frequency requirements at the cost of SNR is the subharmonic mixer. An example of this can be seen in Abdo’s transceiver system, which implements a bidirectional system topology for Tx/Rx modes75. The LO needed either 90° or 45° depending on which mode it was operating in, because the authors implemented their receiver for Hartley image rejection, which requires an extra 90° phase shift (see Fig. 6e). This architecture achieved 40 dB image rejection and was capable of 18 Gbaud.

A multiplier-based receiver which focuses on reaching the IEEE 802.15.3d standard,d was designed in 2022 by Hara et al.76. The actual topology is rather simpler with a rat-race coupler combining the RF and LO and then feeding a mixer-first chain, achieving 17.4 dB NF and 26 dB gain. However, they also provided an interesting packaging technique allowing the system to be mounted to a WR 3.4 waveguide, which, while reducing the system integrability, allows it to be attached to a high-gain antenna (see Fig. 6f). Additionally, they showed QPSK functioning over about one third of the available channels in the 802.15.3d standard at a distance of one meter (albeit at a lower data rate of 4.32 Gb/s.

In 2024, Ghozzy and Allam designed a coherent receiver around 100 GHz based on Kramers-Kronig reception77. In this method, it has been shown that if a single sideband signal meets a minimum phase criterion, the phase can be reconstructed from a measured amplitude. Therefore, it is actually possible to achieve coherence with a direct-detection receiver and some added signal processing78. The basic algorithm for Kramers-Kronig reception is shown in Fig. 6g. While it is possible to feed the detected signal directly to an Analog-to-Digital Converter (ADC) for digital phase reconstruction, Ghozzy and Allam’s work implements fully analog signal processing. At present, this receiver is complicated, requiring blocks such as a logarithmic amplifier and an N-path Hilbert filter, but it does not require a high-frequency synthesizer. This shift of focus away from traditional LO mixing could be promising for future high-frequency coherent receivers.

Discussion

The previous sections discussed some of the benefits and challenges of various modulation schemes and showcased recent designs that innovate on the basic template for high-frequency system design. While we focused primarily on CMOS system design, there is also some important work in nearby areas that impact on-chip sub-THz communications as a whole.

For example, above D-band, all CMOS-based systems struggle with output power, and this metric is a major bottleneck for closing a link with high enough SNR to increase the modulation order and hence data rates and efficiency. Maximum output power is inherent to the device fmax, which is determined by the mobility of silicon and the process node. So, over the past few decades, foundries have improved their devices for higher fmax79 and catered to advanced process nodes, such as FDSOI80 and FinFET81, for RF applications. While these improvements have directly improved sub-THz communication systems, device research can only go so far, as the parasitics that limit them can only be reduced so much.

An example of a system improvement to overcome device limitations is to use other devices. Many high-frequency systems already use materials such as InP, GaAs, and GaN, as their band gaps and fmax (using HEMTs) are larger than CMOS. However, CMOS still garners attention due to its cost and maturity. As such, the heterogeneous integration of CMOS chips and other devices has attracted attention, with heavy focus on the design of low-loss THz interconnects82,83,84 and silicon photonics85,86. These heterogeneous systems can easily outperform CMOS-only systems in terms of output power, maximum frequency, and data rates, potentially by orders of magnitude. For this reason, these systems act as an interesting trade-off of fantastic sub-THz performance for more cost and complexity.

Another improvement on the circuit side, which shows potential for sub-THz improvement,s is injection locking. While not a new concept, its usefulness will be key for fully integrated systems due to its impact on signal generation. Many of the front ends presented in this work use off-chip sources with multiple chains due to the availability of a high-power, low-phase-noise signal when working off-chip. Put simply, free-running oscillators in CMOS are not feasible for sub-THz communications. There have been a few works showcasing the use of coupled oscillator systems for tuning and power20 and fast settling times51, control loops for quadrature locking and phase/frequency stabilization61, injection locked frequency multipliers87, self-injection locking for stabilization88, and also coupled array structures for beam steering89,90. These coupling and injection techniques are improving over time and will certainly become a requirement for fully-integrated sub-THz communications, especially using phase information such as higher-order QAM.

In addition to the specific works discussed in the body of this manuscript, we find it useful to reiterate recent general works in sub-THz CMOS transceivers. See tables below for a brief overview of the state-of-the-art for designs at both D-band (Table 1) and above D-band (Table 2) from recent years. Additionally, we show in Fig. 7 how certain metrics have been trending with frequency lately. It seems that for transmitters, the expected decline of output power over frequency is evident, and increasing both the output power and frequency would be key to future advancements. The data rates are also generally still higher for lower frequencies, but more importantly, we can see that the higher-order modulation schemes tend to vastly outperform the many simpler schemes shown in the literature. Additionally, receiver gain decreases and noise figure increases, as expected. In these graphs, we show a “goal” which is essentially a region for each, which, if any are achieved, would constitute a major improvement for this field.

The values from Tables 1 & 2 arranged to show interesting trends in recent years. (top-left) Transmitter output power decreases with frequency. (top-right) Data rate slightly decreases with frequency. (bottom-left) Receiver noise figure increases with frequency. (bottom-right) Receiver gain decreases with frequency.

Conclusion & future direction

In light of the advancements in CMOS-based design of communication transceivers operating at sub-THz frequencies, the realization of 6G and beyond is now a few major steps closer. However, several key challenges remain, requiring further research and innovation to enable high-performance sub-THz and THz communication systems for both backhaul infrastructure and consumer electronics91. Figure 8 depicts a comprehensive overview of the challenges and proposed solutions in the development of secure and reliable THz communication networks.

The world in which these communication systems operate offers multiple challenges, such as multipath reflections, severe weather, and unintended recipients or interferences. THz communication systems will need to overcome many, if not all, of these challenges to be considered feasible for common consumer usage.

One of the foremost challenges is enhancing signal chain performance, particularly in terms of output power92. While CMOS technology has demonstrated feasibility in high-frequency applications, its relatively low gain and output power continue to be limiting factors, especially in backhaul networks where cost is not a primary concern. To address these limitations, the hybrid integration of high-performance compound semiconductors (e.g., III-V materials93) with CMOS circuits is a growing area of research. Multi-chip solutions integrating a CMOS-based analog/mixed-signal front-end with III-V power amplifiers are emerging as a promising approach to enhance transmission efficiency94. This trend requires significant advancements in packaging and heterogeneous integration, particularly in designing interconnects and transitions that minimize losses at sub-THz frequencies. Recent studies have explored packaging strategies for CMOS-III-V integration at these frequencies95, demonstrating initial feasibility, though practical implementation remains challenging. Nevertheless, despite the fmax limitations and low output power of CMOS technologies, they remain the most widely used in consumer electronics due to their scalability and low cost for mass production18.

Another critical aspect is antenna design96,97, which plays a fundamental role in determining overall system efficiency at sub-THz frequencies. The design of high-gain, broadband antennas that can control antenna polarization, whether on-chip or off-chip, is crucial for improving radiated power and ensuring robust communication links98. Large bandwidths are necessary to achieve ultra-high data rates; however, maintaining broadband radiation characteristics in antenna arrays remains a significant challenge. This challenge is further complicated by the need for phased-array configurations and beam-steering capabilities, which are essential for dynamic and adaptive wireless links11. Additionally, the sensitivity of sub-THz links to weather conditions99 and issues with multipath reflections100 necessitate the use of appropriate radiated polarization to ensure a reliable communication link. Addressing these issues requires a comprehensive approach that balances the trade-offs between integration, efficiency, and scalability.

Moreover, the implementation of complex modulation techniques, such as frequency hopping spread spectrum (FHSS) and direct sequence spread spectrum (DSSS), is essential for ensuring secure and efficient multiple access in sub-THz/THz networks. Although methods like constellation scrambling101 and orbital angular momentum (OAM) beams102 have been proposed for secure THz communications, they achieve security at the expense of sacrificing multiple access capabilities, which is undesirable in real-world applications. Two significant security challenges in THz networks are interception103,104 due to beam divergence and antenna sidelobes, and jamming105 resulting from the large available bandwidth. These challenges can be mitigated by employing advanced modulation techniques in the THz band. Although the implementation of these complex modulation techniques can be computationally intensive in the THz band, particularly for multi-Gb/s transmissions with strict energy constraints and latency requirements106, innovative hardware-level solutions, such as the formation of frequency combs107, are necessary to effectively realize these techniques in integrated THz electronics.

Beyond hardware-level considerations, the system-level operation of MIMO and phased array sub-THz communication systems presents additional challenges. At sub-THz frequencies, carrier synchronization and aggregation become increasingly complex due to phase noise, frequency offsets, and signal dispersion108,109. Advanced signal processing techniques, including digital beamforming and machine learning-based equalization110, are being explored to mitigate these impairments. Additionally, new software layer security protocols must be developed to protect the sub-THz networks against eavesdropping and jamming111,112. While some preliminary solutions have been proposed, many of these system-level aspects are still not fully optimized for 6G and beyond, highlighting the need for further research.

Finally, the practical deployment of sub-THz communication circuits will largely depend on the evolution of applications such as backhaul communication and consumer electronics. Backhaul networks, which serve as the backbone of wireless infrastructure, stand to benefit from sub-THz links due to their potential for ultra-high-speed data transmission. However, the implementation of these systems in real-world scenarios is still limited by link reliability, atmospheric attenuation, and hardware constraints. Similarly, consumer electronics applications, including wireless VR/AR, ultra-high-definition media streaming, and high-speed device-to-device communication, will require significant technological maturation before they reach commercial viability. Nevertheless, with ongoing research and industry investment, these applications are expected to move closer to maturity in the next few years, enabling a transformative leap in wireless connectivity.

In conclusion, while CMOS-based sub-THz communication circuits have made remarkable progress, key challenges in signal chain design, antenna integration, complex modulations, MIMO synchronization, and real-world deployment must be addressed to fully unlock their potential for 6G and beyond. Continued advancements in circuit design, packaging, and system-level optimization will be crucial in shaping the future of high-frequency wireless communication.

Data availability

Any relevant data is shown in this work directly via tables. No other datasets were generated during this study.

References

Naghavi, S. M. H. et al. Filling the gap with sand: when CMOS reaches THz. IEEE Solid-State Circuits Mag. 11, 33–42 (2019).

Williams, B. S. Terahertz quantum-cascade lasers. Nat. Photonics 1, 517–525 (2007).

Li, R. et al. High brightness terahertz quantum cascade laser with near-diffraction-limited Gaussian beam. Light Sci. Appl. 13, 193 (2024).

Du, K.-L. & Swamy, M. N. S. Wireless Communication Systems: From RF Subsystems to 4G Enabling Technologies (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

Sairam, K. V. S. S. S., Gunasekaran, N. & Rama Redd, S. Bluetooth in wireless communication. IEEE Commun. Mag. 40, 90–96 (2002).

Toyoshima, M. Trends in satellite communications and the role of optical free-space communications. J. Opt. Netw. 4, 300–311 (2005).

Foschini, G. J. & Gans, M. J. On limits of wireless communications in a fading environment when using multiple antennas. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 6, 311–335 (1998).

Koenig, S. et al. Wireless sub-THz communication system with high data rate. Nat. Photonics 7, 977–981 (2013).

Mohan, S. S., Hershenson, M. D. M., Boyd, S. P. & Lee, T. H. Bandwidth extension in CMOS with optimized on-chip inductors. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 35, 346–355 (2000).

Maiwald, T. et al. A review of integrated systems and components for 6G wireless communication in the D-band. Proc. IEEE 111, 220–256 (2023).

Ahmed, A. et al. 140-GHz 2-D scalable on-grid 8×8-element transmit-receive phased arrays with up/down converters demonstrating a 5.2-m link at 16 Gbps. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 72, 2852–2868 (2024).

Wang, Z., Wang, H., Hassan, Y. O. & Heydari, P. A bits-to-antenna f-band 120-Gb/s CMOS RF-64QAM transmitter for FutureG wireless links. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 60, 1–17 (2025).

Nam, H. et al. A scalable 16-element and 45.5-dBm-EIRP D-band CMOS phased-array transceiver integrated with antenna-in-package for 6G communications. IEEE Access 13, 27007–27023 (2025).

ECC Recommendation (18)01. Electronic Communications Committee (2018).

International Telecommunication Union. Sharing and compatibility studies between land-mobile, fixed and passive services in the frequency range 275-450 GHz. ITU-R Report SM.2351 (2025).

Serghiou, D., Khalily, M., Brown, T. W. C. & Tafazolli, R. Terahertz channel propagation phenomena, measurement techniques and modeling for 6G wireless communication applications: a survey, open challenges and future research directions. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 24, 1957–1996 (2022).

International Telecommunication Union. Attenuation by atmospheric gases. ITU-R Recommendation P.676-11 (2016).

Fujishima, M. Challenges and innovations in CMOS-based 300-GHz transceivers for high-speed wireless communication. IEEE Open J. Solid-State Circuits Soc. 5, 21–32 (2025).

Momeni, O. & Afshari, E. High power terahertz and millimeter-wave oscillator design: a systematic approach. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 46, 583–597 (2011).

Tousi, Y. M., Momeni, O. & Afshari, E. A novel CMOS high-power terahertz VCO based on coupled oscillators: theory and implementation. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 47, 3032–3042 (2012).

Han, R. & Afshari, E. A high-power broadband passive terahertz frequency doubler in CMOS. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 61, 1150–1160 (2013).

Aghasi, H., Cathelin, A. & Afshari, E. A 0.92-THz SiGe power radiator based on a nonlinear theory for harmonic generation. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 52, 406–422 (2017).

Khatibi, H., Khiyabani, S. & Afshari, E. An efficient high-power fundamental oscillator above \({f}_{\max }/2\): a systematic design. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 65, 4176–4189 (2017).

Grzyb, J., Zhao, Y. & Pfeiffer, U. R. A 288-GHz lens-integrated balanced triple-push source in a 65-nm CMOS technology. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 48, 1751–1761 (2013).

Sengupta, K., & Hajimiri, A. A 0.28-THz power-generation and beam-steering array in CMOS based on distributed active radiators. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 47, 3013–3031 (2012).

Aghasi, H. et al. Terahertz electronics: application of wave propagation and nonlinear processes. Appl. Phys. Rev. 7, 021302 (2020).

Hadidian, B., Khoeini, F., Naghavi, S. M. H., Cathelin, A. & Afshari, E. A 220-GHz energy-efficient high-data-rate wireless ASK transmitter array. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 57, 1623–1634 (2022).

Igarashi, R. et al. First demonstration of 128-Gbit/s 300-GHz-band THz transmission using OFC-based transmitter and intradyne receiver. In Proc. OptoElectronics and Communications Conf. (OECC) & Int. Conf. Photonics in Switching and Computing (PSC) 1–3 (2022).

Zhang, Q. et al. 4.6-km D-band photonic-assisted terahertz wireless communication employing SIMO and MRC technology. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 72, 6657–6668 (2024).

Che, M., Chen, H., Ueda, Y. & Kato, K. Secured THz communication in photonic microcell networks based on spatial wave mixing of steered beams. Opt. Switch. Netw. 54, 100773 (2024).

Nagatsuma, T. & Carpintero, G. Recent progress and future prospect of photonics-enabled terahertz communications research. IEICE Trans. Electron. E98-C, 1060–1070 (2015).

Nagatsuma, T., Fujita, M. & Yi, L. Millimeter-wave and terahertz photonics for communications and sensors. In Proc. Opt. Fiber Commun. Conf. Exhib. (OFC) 1–3 (2021).

Iwamatsu, S., Nishigami, N., Nishida, Y., Fujita, M. & Nagatsuma, T. Broadband terahertz resonant tunnelling diode transmitter integrated with coplanar-waveguide-fed slot-ring antenna. Electron. Lett. 57, 1001–1003 (2021).

Nagatsuma, T., Ducournau, G. & Renaud, C. C. Advances in terahertz communications accelerated by photonics. Nat. Photonics 10, 371–379 (2016).

Tousi, Y. & Afshari, E. A high-power and scalable 2-D phased array for terahertz CMOS integrated systems. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 50, 597–609 (2014).

Yu, J. et al. A 300-GHz transmitter front end with -4.1-dBm peak output power for sub-THz communication using 130-nm SiGe BiCMOS technology. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 69, 4925–4936 (2021).

Seo, M. et al. InP HBT IC technology for terahertz frequencies: fundamental oscillators up to 0.57 THz. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 46, 2203–2214 (2011).

Han, R. & Afshari, E. A CMOS high-power broadband 260-GHz radiator array for spectroscopy. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 48, 3090–3104 (2013).

Han, R. et al. A SiGe terahertz heterodyne imaging transmitter with 3.3 mW radiated power and fully integrated phase-locked loop. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 50, 2935–2947 (2015).

Cao, T. et al. Frequency multiplier-based millimeter-wave vector signal transmitter using digital predistortion with constrained feedback bandwidth. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 68, 1819–1829 (2020).

D’heer, C. & Reynaert, P. A fully integrated 135-GHz direct-digital 16-QAM wireless and dielectric waveguide link in 28-nm CMOS. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 59, 889–907 (2024).

Park, J.-D., Kang, S., Thyagarajan, S. V., Alon, E. & Niknejad, A. M. A 260-GHz fully integrated CMOS transceiver for wireless chip-to-chip communication. In Proc. Symp. VLSI Circuits (VLSIC) 48–49 (2012).

Wang, Z. et al. A CMOS 210-GHz fundamental transceiver with OOK modulation. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 49, 564–580 (2014).

Jiang, C., Cathelin, A. & Afshari, E. A high-speed efficient 220-GHz spatial-orthogonal ASK transmitter in 130-nm SiGe BiCMOS. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 52, 2321–2334 (2017).

Liang, Y. et al. D-band surface-wave modulator and signal source with 40-dB extinction ratio and 3.7-mW output power in 65-nm CMOS. In Proc. Eur. Solid-State Circuits Conf. (ESSCIRC) 142–145 (2018).

Garay, E. F., Munzer, D. J. & Wang, H. A 150-GHz lens-free large-FoV regenerative 2×2 transceiver array with 31% DC-to-EIRP efficiency and -70 dBm sensitivity for a 70-cm bidirectional peer-to-peer link. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 57, 2102–2113 (2022).

Dolatsha, N. et al. A compact 130-GHz fully packaged point-to-point wireless system with 3D-printed 26-dBi lens antenna achieving 12.5 Gb/s at 1.55 pJ/b/m. In Proc. IEEE Int. Solid-State Circuits Conf. (ISSCC) 306–307 (2017).

Lee, E. et al. A 1.54-mm2, 264-GHz wake-up receiver with integrated cryptographic authentication for ultra-miniaturized platforms. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 59, 653–667 (2023).

Tang, D. et al. 24.1 A 90-to-180-GHz APD-integrated transmitter achieving 18-dBm Psat in 28-nm CMOS. In Proc. IEEE Int. Solid-State Circuits Conf. (ISSCC) 67, 411–413 (2024).

Moriyama, M., Takashima, K., Sawada, H. & Matsumura, T. Basic study on FSK transmission using convolutional code in terahertz band. In Proc. 27th Int. Symp. Wireless Pers. Multimedia Commun. (WPMC) 1–5 (2024).

Chen, L., Nooshabadi, S., Cathelin, A. & Afshari, E. Variable-phase-shift-based high data-rate sub-THz FSK transmitter design: theory and implementation. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 71, 669–681 (2023).

Afzal, H., Li, C. & Momeni, O. A highly efficient 165-GHz 4FSK 17-Gb/s transceiver system with frequency-overlapping architecture in 65-nm CMOS. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 58, 3113–3126 (2023).

Razavian, S., Thomas, S., Hosseini, M. & Babakhani, A. A 0.4-THz efficient OOK/FSK wireless transmitter enabling 3 Gb/s at 20 m. In Proc. 2022 IEEE BiCMOS and Compound Semiconductor Integrated Circuits and Technology Symp. (BCICTS) 178–181 (2022).

Chen, L., Taba, M., Cathelin, A. & Afshari, E. A low-power 20 Gb/s 196-GHz BPSK wireless transmitter with energy-efficiency FoM of 0.15 pJ/bit/cm. In Proc. 2023 IEEE Custom Integrated Circuits Conf. (CICC) 1–2 (2023).

Nazari, P., Jafarlou, S. & Heydari, P. A CMOS two-element 170-GHz fundamental-frequency transmitter with direct RF-8PSK modulation. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits55, 282–297 (2020). A high performance PSK-based transmitter only requiring a 45∘ switched phase shifter.

Rodriguez-Vazquez, P., Grzyb, J., Heinemann, B. & Pfeiffer, U. R. A QPSK 110-Gb/s polarization-diversity MIMO wireless link with a 220–255 GHz tunable LO in a SiGe HBT technology. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 68, 3834–3851 (2020).

Lee, S. et al. An 80-Gb/s 300-GHz-band single-chip CMOS transceiver. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 54, 3577–3588 (2019).

Standaert, A. & Reynaert, P. A 390-GHz outphasing transmitter in 28-nm CMOS. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 55, 2703–2713 (2020).

Li, S., Chi, T., Park, J.-S., Nguyen, H. T. & Wang, H. A 28-GHz flip-chip packaged Chireix transmitter with on-antenna outphasing active load modulation. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 54, 1243–1253 (2019).

Wang, C. et al. 24.3 A 236-to-266-GHz 4-element amplifier-last phased-array transmitter in 65-nm CMOS. In Proc. IEEE Int. Solid-State Circuits Conf. (ISSCC) 67, 415–417 (2024).

Callender, S. et al. A fully integrated 160-Gb/s D-band transmitter with 1.1 pJ/b efficiency in 22-nm FinFET technology. IEEE Int. Solid-State Circuits Conf. (ISSCC) Dig. Tech. Pap. 65, 78–80 (2022).

Shopov, S., Gurbuz, O. D., Rebeiz, G. M. & Voinigescu, S. P. A D-band digital transmitter with 64-QAM and OFDM free-space constellation formation. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 53, 2012–2022 (2018).

Wang, Z., Wang, H., Hassan, Y. O. & Heydari, P. A CMOS fully integrated 120-Gb/s RF-64QAM F-band transmitter with an on-chip antenna for 6G wireless communication. In Proc. IEEE Radio Freq. Integr. Circuits Symp. (RFIC) 343–346 (2024).

Makhlouf, S. et al. Terahertz sources and receivers: from the past to the future. IEEE J. Microw. 3, 894–912 (2023).

Ferreras, M., Čibiraitė Lukenskienė, D., Lisauskas, A., Grajal, J. & Krozer, V. Broadband sensing around 1 THz via a novel biquad-antenna-coupled low-NEP detector in CMOS. IEEE Trans. Terahertz Sci. Technol. 11, 16–27 (2021).

Burasa, P., Mnasri, B. & Wu, K. Millimeter-wave CMOS sourceless receiver architecture for 5G-served ultra-low-power sensing and communication systems. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 67, 1688–1696 (2019).

Ludwig, F., Holstein, J., Krysl, A., Lisauskas, A. & Roskos, H. G. Modeling of antenna-coupled Si MOSFETs in the terahertz frequency range. IEEE Trans. Terahertz Sci. Technol. 14, 414–423 (2024).

Andree, M., Grzyb, J., Jain, R., Heinemann, B. & Pfeiffer, U. R. Broadband modeling, analysis, and characterization of SiGe HBT terahertz direct detectors. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 70, 1314–1333 (2022).

Dyakonov, M. & Shur, M. Detection, mixing, and frequency multiplication of terahertz radiation by two-dimensional electronic fluid. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 43, 380–387 (1996).

Tauk, R. et al. Plasma wave detection of terahertz radiation by silicon field effect transistors: responsivity and noise equivalent power. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89, 253511 (2006).

Virginia Diodes. Detectors. Available at: https://vadiodes.com/en/zbd. (Accessed: 5 December 2024).

Shaulov, E., Jameson, S. & Socher, E. A zero-bias J-band antenna-coupled detector in 65-nm CMOS. IEEE Trans. Terahertz Sci. Technol. 11, 62–69 (2021).

Memioglu, O., Zhao, Y. & Razavi, B. A 300-GHz 52-mW CMOS receiver with on-chip LO generation. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 58, 2141–2156 (2023).

Li, Z. et al. A 220-GHz sliding-IF quadrature transmitter and receiver chipset for high data rate communication in 0.13-μm SiGe BiCMOS. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 58, 1913–1927 (2023).

Abdo, I. et al. 22.2 A 300-GHz-band phased-array transceiver using bi-directional outphasing and Hartley architecture in 65-nm CMOS. In Proc. IEEE Int. Solid-State Circuits Conf. (ISSCC) 64, 316–318 (2021).

Hara, S. et al. A 76-Gb/s 265-GHz CMOS receiver with WR-3.4 waveguide interface. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 57, 2988–2998 (2022).

Ghozzy, S., Allam, M., Karahan, E. A., Liu, Z. & Sengupta, K. 12.2 A mmWave/sub-THz synthesizer-free coherent receiver with phase reconstruction through mixed-signal Kramers-Kronig processing. Proc. IEEE Int. Solid-State Circuits Conf. (ISSCC) 67, 220–222 (2024).

Mecozzi, A., Antonelli, C. & Shtaif, M. Kramers-Kronig coherent receiver. Optica 3, 1220–1227 (2016).

Debaillie, B. et al. B55x: a shift in STMicroelectronics BiCMOS technologies. In Key Enabling Technologies for Future Wireless, Wired, Optical and Satcom Applications (River Publishers, 2024).

Ong, S. N. et al. A 22-nm FDSOI technology optimized for RF/mmWave applications. In Proc. IEEE Radio Freq. Integr. Circuits Symp. (RFIC) 72–75 (2018).

Lee, H.-J. et al. Intel 22-nm FinFET (22FFL) process technology for RF and mmWave applications and circuit design optimization for FinFET technology. In Proc. IEEE Int. Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM) 14.1.1–14.1.4 (2018).

Li, C.-H. & Chiu, T.-Y. Low-loss single-band, dual-band, and broadband mmWave and (sub-)THz interconnects for THz SoP heterogeneous system integration. IEEE Trans. Terahertz Sci. Technol. 12, 130–143 (2022).

Li, C.-H. et al. A 37.5-mW 8-dBm-EIRP 15.5∘-HPBW 338-GHz terahertz transmitter using SoP heterogeneous system integration. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 63, 470–480 (2015).

Holloway, J. W., Dogiamis, G. C. & Han, R. 11.9 A 105-Gb/s dielectric-waveguide link in 130-nm BiCMOS using channelized 220-to-335-GHz signal and integrated waveguide coupler. Proc. IEEE Int. Solid-State Circuits Conf. (ISSCC) 64, 196–198 (2021).

Harter, T. et al. Silicon-plasmonic integrated circuits for terahertz signal generation and coherent detection. Nat. Photonics 12, 625–633 (2018).

Xie, J., Ye, W. & Zhou, L. A review on terahertz technologies accelerated by silicon photonics. Nanomaterials 11, 1646 (2021).

Iotti, L., LaCaille, G. & Niknejad, A. M. A dual-injection technique for mmWave injection-locked frequency multipliers. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 69, 5417–5428 (2021).

Hossein Naghavi, S. M. et al. 24.4 Sub-THz ruler: spectral bistability in a 235-GHz self-injection-locked oscillator for agile and unambiguous ranging. Proc. IEEE Int. Solid-State Circuits Conf. (ISSCC) 67, 418–420 (2024).

Jalili, H. & Momeni, O. 23.2 A 436-to-467-GHz lens-integrated reconfigurable radiating source with continuous 2D steering and multi-beam operations in 65-nm CMOS. Proc. IEEE Int. Solid-State Circuits Conf. (ISSCC) 64, 326–328 (2021).

Gao, L. & Chan, C. H. 24.1 A 0.64-to-0.69-THz beam-steerable coherent source with 9.1-dBm radiated power and 30.8-dBm lensless EIRP in 65-nm CMOS. In Proc. IEEE Int. Solid-State Circuits Conf. (ISSCC), 362–364 (2023).

Sharma, T., Chehri, A. & Fortier, P. Review of optical and wireless backhaul networks and emerging trends of next-generation 5G and 6G technologies. Trans. Emerg. Telecommun. Technol. 32, e4155 (2021).

Chafii, M., Bariah, L., Muhaidat, S. & Debbah, M. Twelve scientific challenges for 6G: Rethinking the foundations of communications theory. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tuts. 25, 868–904 (2023).

Urteaga, M., Griffith, Z., Seo, M., Hacker, J. & Rodwell, M. J. W. InP HBT technologies for THz integrated circuits. Proc. IEEE 105, 1051–1067 (2017).

Jeong, J. et al. Heterogeneous and monolithic 3D integration of III–V-based radio frequency devices on Si CMOS circuits. ACS Nano 16, 9031–9040 (2022).

Buckwalter, J. F. et al. Prospects for high-efficiency silicon and III-V power amplifiers and transmitters in 100-300 GHz bands. In Proc. IEEE Custom Integrated Circuits Conf. (CICC), 1–7 (2021).

Maktoomi, M. H. et al. A sub-terahertz wideband stacked-patch antenna on a flexible printed circuit for 6G applications. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 70, 10047–10061 (2022).

Bae, H. H., Jang, T. H., Kim, H. Y. & Park, C. S. Broadband 120 GHz L-probe differential feed dual-polarized patch antenna with soft surface. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 69, 6185–6195 (2021).

Maktoomi, M. H., Saadat, S., Momeni, O., Heydari, P. & Aghasi, H. Broadband antenna design for terahertz communication systems. IEEE Access 11, 20897–20911 (2023).

Schneider, T., Wiatrek, A., Preussler, S., Grigat, M. & Braun, R. P. Link budget analysis for terahertz fixed wireless links. IEEE Trans. Terahertz Sci. Technol. 2, 250–256 (2012).

Petrov, V., Moltchanov, D., Jornet, J. M. & Koucheryavy, Y. Exploiting multipath terahertz communications for physical layer security in beyond 5G networks. In Proc. IEEE INFOCOM Workshops, 865–872 (2019).

Sengupta, K., Lu, X., Venkatesh, S. & Tang, B. Physically secure sub-THz wireless links. In Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. Commun. Workshops (ICC Workshops), 6 (2020).

Khan, M. I. W. et al. A 0.31-THz orbital-angular-momentum (OAM) wave transceiver in CMOS with bits-to-OAM mode mapping. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 57, 1344–1357 (2022).

Ma, J. et al. Security and eavesdropping in terahertz wireless links. Nature 563, 89–93 (2018).

Shaikhanov, Z., Badran, S., Jornet, J. M., Mittleman, D. M. & Knightly, E. W. Remotely positioned metasurface-drone attack. In Proc. 24th Int. Workshop Mobile Comput. Syst. Appl. (HotMobile), 110–116 (2023).

Shrestha, R., Guerboukha, H., Fang, Z., Knightly, E. & Mittleman, D. M. Jamming a terahertz wireless link. Nat. Commun. 13, 1–9 (2022).

Poor, H. V. & Schaefer, R. F. Wireless physical layer security. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 19–26 (2017).

Yi, X. et al. A 4.8 THz FMCW comb radar in 65-nm CMOS with 100 GHz bandwidth. In Proc. IEEE Int. Solid-State Circuits Conf. (ISSCC), 90–92 (2020).

Wei, Z. et al. Carrier aggregation enabled integrated sensing and communication signal design and processing. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol., 2023.

Hokazono, Y., Kohara, H., Kishiyama, Y. & Asai, T. Extreme coverage extension in 6G: Cooperative non-terrestrial network architecture integrating terrestrial networks. In Proc. IEEE Wireless Commun. Netw. Conf. (WCNC), 138–143 (2022).

Mahmood, M. R., Matin, M. A., Sarigiannidis, P. & Goudos, S. K. A comprehensive review on artificial intelligence/machine learning algorithms for empowering the future IoT toward 6G era. IEEE Access 10, 87535–87562 (2022).

Siriwardhana, Y., Porambage, P., Liyanage, M. & Ylianttila, M. AI and 6G security: Opportunities and challenges. In Proc. Joint Eur. Conf. Netw. Commun. & 6G Summit (EuCNC/6G Summit), 616–621 (2021).

Porambage, P., Gür, G., Moya Osorio, D. P., Livanage, M. & Ylianttila, M. 6G security challenges and potential solutions. In Proc. Joint Eur. Conf. Netw. Commun. & 6G Summit (EuCNC/6G Summit), 622–627 (2021).

Townley, A., Baniasadi, N., Krishnamurthy, S., Sideris, C., Hajimiri, A., Alon, E. & Niknejad, A. A fully integrated, dual-channel, flip-chip packaged 113-GHz transceiver in 28-nm CMOS supporting an 80-Gb/s wireless link. In Proc. IEEE Custom Integrated Circuits Conf. (CICC), 1–4 (2020).

Dogiamis, G. C. et al. A 120-Gb/s 100-145-GHz 16-QAM dual-band dielectric waveguide interconnect with package-integrated diplexers in Intel 16. IEEE Solid-State Circuits Lett. 5, 178–181 (2022).

Mohammadnezhad, H., Wang, H., Cathelin, A. & Heydari, P. A 115-135-GHz 8PSK receiver using multi-phase RF-correlation-based direct-demodulation method. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits, PP, 1–14 (2019).

Brown, T. W. et al. A 50-Gb/s 134-GHz 16-QAM 3-m dielectric waveguide transceiver system implemented in 22-nm FinFET CMOS. IEEE Solid-State Circuits Lett. 4, 206–209 (2021).

Dens, K. et al. Design of a noncoherent 100-Gb/s 3-m dual-band PAM-4 dielectric waveguide link in 28-nm CMOS. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 59, 1398–1408 (2024).

Hamani, A. et al. A 112.64-Gb/s CMOS D-band channel-aggregation RX system-in-package. In Proc. IEEE Radio Freq. Integr. Circuits Symp. (RFIC), 283–286 (2024).

Agrawal, A. et al. A 128-Gb/s D-band receiver with integrated PLL and ADC achieving 1.95-pJ/b efficiency in 22-nm FinFET. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 58, 3364–3379 (2023).

Karakuzulu, A., Ahmad, W. A., Kissinger, D. & Malignaggi, A. A four-channel bidirectional D-band phased-array transceiver for 200-Gb/s 6G wireless communications in a 130-nm BiCMOS technology. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 58, 1310–1322 (2023).

Guan, P. et al. A fully integrated bit-to-bit 24/48-Gb/s QPSK/16-QAM D-band transceiver with mixed-signal baseband in 28-nm CMOS technology. In Proc. IEEE Asian Solid-State Circuits Conf. (A-SSCC), 1–3 (2023).

Liu, C. et al. A 640-Gb/s 4×4-MIMO D-band CMOS transceiver chipset. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 60, 1132–1149 (2025).

Singh, A. et al. A D-band radio-on-glass module for spectrally-efficient and low-cost wireless backhaul. In Proc. IEEE Radio Freq. Integr. Circuits Symp. (RFIC), 99–102 (2020).

Li, S., Zhang, Z., Rupakula, B. & Rebeiz, G. M. An eight-element 140-GHz wafer-scale IF beamforming phased-array receiver with 64-QAM operation in CMOS RFSOI. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 57, 385–399 (2022).

Elkhouly, M. et al. Fully integrated 2D scalable TX/RX chipset for D-band phased-array-on-glass modules. Proc. IEEE Int. Solid-State Circuits Conf. (ISSCC) 65, 76–78 (2022).

Hamani, A. et al. A D-band multichannel TX system-in-package achieving 84.48 Gb/s with 64-QAM based on 45-nm CMOS and low-cost PCB technology. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 70, 3385–3395 (2022).

Hamani, A. et al. A 84.48-Gb/s 64-QAM CMOS D-band channel-bonding TX front-end with integrated multi-LO frequency generation. IEEE Solid-State Circuits Lett. 3, 346–349 (2020).

González-Jiménez, J. L. et al. A D-band transmitter achieving 57.6-Gb/s and 30-dBm EIRP based on channel-aggregation 45-nm ICs and a low-profile flat lens antenna. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 72, 836–850 (2024).

Choi, K.-S., Lee, H., Yun, B. & Lee, S.-G. A D-band low-noise and high-gain receiver front-end adopting gmax-driven active mixer. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 72, 5576–5587 (2024).

Xie, F. et al. A 220-GHz planar triangular lattice transmitter array with 42.7-dBm peak EIRP for long-distance high-data-rate wireless communication. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 73, 3194–3208 (2025).

Grzyb, J., Rodríguez-Vázquez, P., Malz, S., Andree, M. & Pfeiffer, U. R. A SiGe HBT 215-240 GHz DCA IQ TX/RX chipset with built-in test of USB/LSB RF asymmetry for 100+ Gb/s data rates. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 70, 1696–1714 (2022).

Rodríguez-Vázquez, P., Grzyb, J., Heinemann, B. & Pfeiffer, U. R. A 16-QAM 100-Gb/s 1-m wireless link with an EVM of 17.

Eissa, M. H. et al. 100 Gb/s 0.8-m wireless link based on fully integrated 240 GHz IQ transmitter and receiver. In Proc. IEEE/MTT-S Int. Microwave Symp. (IMS), 627–630 (2020).

Eissa, M. H. et al. Wideband 240-GHz transmitter and receiver in BiCMOS technology with 25-Gb/s data rate. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 53, 2532–2542 (2018).

Steinweg, L., Hebeler, J., Meister, T., Zwick, T. & Ellinger, F. 8.0-pJ/bit BPSK transmitter with LO phase steering and 52-Gbps data rate operating at 246 GHz. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 71, 3217–3226 (2023).

Abdo, I. et al. A bi-directional 300-GHz-band phased-array transceiver in 65-nm CMOS with outphasing transmitting mode and LO emission cancellation. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 57, 2292–2308 (2022).

Trinh, V.-S., Song, J.-M. & Park, J.-D. A 260-300-GHz mixer-first IQ receiver with fundamental LO driver in 130-nm SiGe process. IEEE Microw. Wirel. Technol. Lett. 33, 435–438 (2023).

Abdo, I. et al. A 300-GHz wireless transceiver in 65-nm CMOS for IEEE 802.15.3d using push-push subharmonic mixer. In Proc. IEEE/MTT-S Int. Microwave Symp. (IMS), 623–626 (2020).

D’heer, C. & Reynaert, P. A high-speed 390-GHz BPOOK transmitter in 28-nm CMOS. In Proc. IEEE Radio Freq. Integr. Circuits Symp. (RFIC), 223–226 (2020).

Thomas, S. et al. A 400-GHz efficient radiator and OOK transceiver for multi-Gb/s wireless communication in silicon. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 59, 1381–1397 (2024).

Standaert, A. & Reynaert, P. A 410 GHz OOK transmitter in 28-nm CMOS for short-distance chip-to-chip communications. In Proc. IEEE Radio Freq. Integr. Circuits Symp. (RFIC), 240–243 (2018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.G. led the overall writing, structuring, and literature review of this work. H.Al. and A.T. wrote the Phase Modulation section. L.C. assisted with the Amplitude and Frequency Modulation sections. H.Ag. and H.N. wrote the Introduction and Future Direction Sections, as well as provided assistance with overall editing and structuring of the work. E.A. provided structural guidance for the work. All authors contributed to the design of figures, editing, and overall discussion of the direction of this work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Engineering thanks Aravind Nagulu, Suresh Venkatesh, and the other anonymous reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: [Yasaman Ghasempour] and [Rosamund Daw].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gruber, J., Alotaibi, H., Tabatabavakili, A. et al. Sub-THz communication systems: pushing the capabilities of silicon. Commun Eng 4, 213 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44172-025-00545-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44172-025-00545-9