Abstract

Biohybrid robots integrate skeletal and cardiac muscle tissues with synthetic components, emulating energy-efficient, adaptive natural movements. Skeletal muscles enable precise control suited for walking and gripping, whereas cardiac muscles offer rhythmic contractions ideal for swimming and pumping. Despite significant progress, achieving stability, scalability, and precise biotic-abiotic integration remains challenging. This review summarizes recent advances, identifies critical obstacles, and proposes strategies for next-generation biohybrid robotic systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

An actuator, a device that converts energy into motion, is fundamental to biological organisms and engineered systems and drives essential movements and functions. In living organisms, three main muscle types, cardiac, smooth, and skeletal, enable a wide range of involuntary and voluntary activities necessary for survival1,2,3. Cardiac muscles located in the heart sustain rhythmic contractions that pump blood throughout the body4, ensuring efficient oxygen and nutrient delivery. Smooth muscle, found in the walls of blood vessels and organ systems, facilitates peristaltic and directed fluid transport4. Meanwhile, skeletal muscle, comprising ~40% of body mass, powers voluntary actions, such as walking and chewing, making it vital for mobility and environmental interaction5. The maintenance and repair of these tissues are indispensable for overall health, emphasizing their biological importance1,2,3. As each muscle type offers distinct functional advantages, biohybrid robotics harnesses these biological principles by integrating living tissues with synthetic components. Autonomous and rhythmic contractions of cardiac muscles make them particularly suitable for continuous actuation tasks such as pumping and swimming6,7. In contrast, skeletal muscles provide precise spatial and temporal control, enabling diverse movements such as grasping and walking8,9,10,11,12,13. Although less frequently utilized in existing biohybrid systems, smooth muscles are promising for peristaltic or fine-scale fluid regulation. By leveraging these varying muscle properties, biohybrid robots can emulate natural locomotion with remarkable adaptability, often surpassing the capabilities of conventional synthetic actuators9,14,15,16. The interdisciplinary nature of biohybrid robotics has fostered innovation in robotics and biological sciences. Bioengineers have successfully developed bioinspired robots capable of functioning in real-world settings by emulating natural movement strategies4,17,18,19,20. Biohybrid robots have become valuable platforms for testing hypotheses in biology, enabling researchers to investigate multicellular systems under controlled conditions21,22,23. These efforts have provided critical insights into biophysics and physiology, while informing the predictive design of biohybrid systems24,25,26.

These biological tissues, derived from living cells, offer unique advantages for robotics, as they are inherently adaptable, responsive to external stimuli, and energy efficient. For instance, skeletal and cardiac muscle cells can integrate optical, thermal, and mechanical signals to produce outputs, such as force generation, chemical release, and self-repair4,27. These attributes make biohybrid actuators particularly appealing for applications in dynamic and uncertain settings, ranging from drug delivery and surgical tools to exploratory robotics28,29,30,31.

Despite these advantages, implementing living tissues on a scale requires strict control of temperature, humidity, pH, oxygen levels, and specialized nutrient media tailored to each cell type, creating formidable obstacles for large-scale manufacturing and long-term stability14. Recent progress in bioengineering, including advances in three-dimensional (3D) bioprinting and optogenetics, has addressed these challenges by enhancing tissue fabrication, maturation, and functional integration32,33,34. These methods facilitate the creation of robust biohybrid systems that merge the adaptability and responsiveness of living tissues with the precision and durability of the synthetic scaffolds. Nonetheless, a critical gap remains in achieving fully autonomous biohybrid robots that can function without using constant external power sources or control inputs. Achieving fully self-regulating energy-autonomous systems would revolutionize robotic technology, while opening new frontiers in biological research.

This review offers an in-depth examination of biohybrid actuators based on muscle cells, focusing on the recent progress, significant challenges, and future prospects. By exploring advancements in robots that swim, walk, grip, and pump, this study highlights the potential of incorporating biofabricated actuators into engineered systems. It also pinpoints essential research gaps, such as creating strong abiotic/biotic interfaces and scaling up manufacturing processes, to steer the development of adaptive and multifunctional biohybrid robots. This interdisciplinary approach not only boosts the capabilities of robotics but also deepens our understanding of biological systems, paving the way for groundbreaking applications in fields such as medicine and biology. This review presents a cohesive perspective on biohybrid actuators by focusing on the functional comparison and integration of the skeletal and cardiac muscle systems. This emphasizes the complementary roles of each muscle type and explores the synergistic potential of combining them within hybrid platforms. We offer new insights into the design of next-generation multifunctional and adaptive biohybrid robots by treating the skeletal and cardiac muscles as cooperative bioactuation modules rather than as separate strategies.

Biohybrid robots: concept and design principles

Components of biohybrid robots

Biotic components

The biotic components in biohybrid robots encompass living cells and tissues, notably skeletal and cardiac muscles, which function as biological actuators. Cardiomyocytes stand out for their autonomous, rhythmic contractions, making them particularly well-suited for continuous tasks, such as pumping and swimming6. These cells are often derived from neonatal rat ventricular myocytes or human-induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) and are cultured to form contractile tissues (Fig. 1a). This property makes them ideal for applications requiring consistent long-term actuation, such as micropumps or swimming robots. In contrast, skeletal muscle tissue can generate precise external control. Engineered from myoblasts (C2C12), these tissues mainly require a 3D scaffold, frequently a hydrogel, that promotes proper cellular alignment and differentiation11. Such alignment is essential for effective muscle function in bioactuators, which require complex coordinated movement. It tends to offer greater control over the timing and strength of contractions, making it suitable for tasks that require more precise and varied movements. In addition to the widely used C2C12 mouse myoblasts, a variety of alternative cell sources have been employed in engineered skeletal muscle tissues to better replicate the physiological relevance or improve clinical translatability. Primary myoblasts isolated from the hindlimb muscles of neonatal rats exhibit superior contractile function and maturation potential compared with immortalized cell lines11,35. Recently, human skeletal muscle cells (hSkMCs) derived from biopsies or stem cell differentiation protocols have gained increasing attention owing to their clinical relevance and immunological compatibility15,36. These cell sources offer distinct advantages in terms of species specificity, alignment fidelity, and force output, and their inclusion is essential for building translationally relevant muscle-actuated systems.

a Cell Sources: Biohybrid robots utilize cardiac and skeletal muscle tissues derived from primary tissues or induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). b Abiotic Materials: Structural and functional components were fabricated using biomaterials such as Matrigel, GelMA, PDMS, carbon nanotubes, and metallic elements (gold/platinum). c Fabrication Techniques: Various methods, including photolithography, 3D printing, soft lithography, and laser cutting, have been employed to construct biohybrid robots. d History of Biohybrid Robot Design: A timeline of notable biohybrid robots from 2012 to the present, highlighting advancements in skeletal and cardiac muscle-based bioactuators, neuromuscular junction integration, and machine-learning approaches for autonomous control. e Muscle Contraction and Control Mechanisms: Biohybrid actuators function through spontaneous contraction, external electrical stimulation, optical stimulation via optogenetics, or neuromuscular junction-based activation, thereby enabling precise motion control.

To enhance the maturation, contractile function, and regenerative capacity of both cardiomyocytes and skeletal muscle cells in biohybrid systems, co-culture with additional supportive cell types is essential. Cardiac fibroblasts and endothelial cells are frequently incorporated into cardiac constructs to mimic the native myocardial microenvironment. Cardiac fibroblasts secrete extracellular matrix (ECM) components and paracrine factors that promote the structural organization and electrophysiological maturation of cardiomyocytes37. Endothelial cells, in contrast, contribute to vascular-like networks that support tissue viability and stimulate cardiomyocyte alignment and function37. In skeletal muscle-based actuators, the incorporation of fibroadipogenic progenitors (FAPs) and motor neurons can significantly improve muscle maturation and function. FAPs help regulate the muscle stem cell niche and prevent fibrotic remodeling38, while motor neurons establish neuromuscular junctions (NMJs), enabling neuron-driven contraction and more physiologically relevant responses38.

Moreover, mesenchymal stem cells are often introduced into both cardiac and skeletal muscle systems for their trophic support, immunomodulatory effects, and ability to enhance regenerative outcomes through paracrine signaling39. Importantly, immune cells, particularly macrophages, play an emerging role in orchestrating tissue development and remodeling in engineered muscle constructs. Macrophages not only contribute to debris clearance and inflammation resolution during tissue repair, but also secrete cytokines and growth factors that modulate myogenic and cardiogenic differentiation40. The distinct polarization states of macrophages (e.g., pro-inflammatory M1 and pro-regenerative M2) have been shown to differentially influence the balance between inflammation and regeneration, with M2-like macrophages enhancing vascularization, myotube formation, and functional recovery. Incorporating macrophages into biohybrid constructs or modulating their activity through cytokine delivery is a promising strategy to accelerate tissue maturation and improve the performance of living actuators.

Nonetheless, when it comes to utilizing living organisms, relying on mammalian cells, particularly cardiomyocytes and skeletal myocytes, presents several challenges. These cells require precisely controlled conditions, such as a temperature of 37 °C, specific humidity, oxygen levels, pH, and nutrient supply4. While these limitations restrict the design and application possibilities of biohybrid robots, they reflect the origins of the tissue engineering field in research focused on human health4. Moreover, using explanted muscle tissue for actuators is unsustainable because it involves sacrificing animals for each use and is subject to inherent variability in tissue properties4. Therefore, employing engineered tissues remains the most promising strategy for the development of scalable and consistent biohybrid robots.

Recent studies have demonstrated the benefits of mechanical and electromechanical stimulation during in vitro cultivation for enhancing the maturation and force generation of engineered skeletal muscle actuators. Guix et al. developed a self-stimulating spring-like skeleton that provides cyclic mechanical loading via its restoring force during spontaneous contractions, resulting in improved myotube alignment and a significantly enhanced contractile output9. This system enabled biohybrid swimmers to reach speeds of up to 800 μm/s, outperforming many cardiomyocyte-based constructs. To enhance the performance of biohybrid actuators, Yang et al. developed two distinct approaches targeting skeletal muscle maturation and system design. They introduced an electromechanical co-stimulation system that applied real-time adjustable mechanical resistance alongside electrical pulses, recapitulating in vivo training conditions. This method significantly improved myogenic differentiation and enabled muscle tissues to drive a biohybrid robot at a speed of 2.38 mm/s41. In another work, they proposed a modular muscle actuator system optimized for structural scalability and assembly. By engineering narrow and double-striped muscle constructs, they achieved enhanced alignment and contractility, with a maximum force of 2.92 ± 0.07 mN and responsiveness up to 10 Hz. These modular units were integrated into various biohybrid robots, demonstrating versatile morphologies and high actuation performance42.

Abiotic components

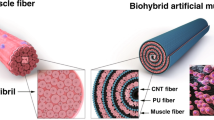

Abiotic components, including hydrogels, synthetic polymers, conductive materials, and electronic circuits, form the critical structural and functional foundations of biohybrid robots. These components play an essential role in enabling precise control and facilitating effective interactions with their biotic counterparts, thereby reinforcing the seamless integration of biological and mechanical systems. Among these components, hydrogels such as Matrigel11,36,43,44, fibrin-thrombin9,12,13,35,36,45, gelatin6,46, and gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA)47 have been extensively utilized because of their exceptional biocompatibility and ability to mimic the natural ECM (Fig. 1b). This mimicry is an essential requirement in tissue engineering as it creates an environment conducive to cell growth and differentiation. Fibrin-thrombin hydrogels offer a biofunctional approach by simulating the natural processes of wound healing and tissue regeneration. The enzymatic action of thrombin on fibrinogen leads to the formation of a fibrous network that significantly promotes cell migration and adhesion. This property is especially advantageous for tissues requiring meticulous cellular organization, such as cardiac and skeletal muscles, where structural integrity and proper cell alignment are vital48. Gelatin hydrogels have been recognized for their versatility as scaffolds that promote cell adhesion and proliferation. Their tunable mechanical properties make them particularly suitable for engineered tissues that require specific characteristics, such as elasticity and tensile strength, to closely match native tissues49. GelMA represents a transformative advancement in hydrogel technology, particularly when modified with carbon nanotubes (CNTs), to enhance both electrical conductivity and mechanical strength47. These enhancements are imperative for synchronizing the contraction of cardiomyocytes and facilitating the development of biohybrid robots that closely emulate the functionality of natural organisms.

Synthetic polymers, such as polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) and polylactic acid, are preferred for their robust mechanical properties and compatibility with optical systems (Fig. 1b). PDMS is widely favored in the fields of microfluidics and soft robotics owing to its optical clarity, flexibility, and ease of manipulation. These characteristics make it an ideal material for creating intricate designs of lab-on-a-chip devices. In addition, conductive materials, including CNTs47, gold nanoparticles50, and graphene51, enhance the electrical interfaces between robotic components and biological tissues. This integration improves the signal transmission efficiency in biohybrid systems, enabling real-time feedback and interaction between the mechanical and biological elements52.

The fabrication of biohybrid robots relies on advanced materials and precise engineering methods to construct functional platforms that are seamlessly integrated with living tissues. A widely used approach involves the use of resin-based materials49 to form a robot’s structural chassis. These resins provide both mechanical stability and design flexibility, enabling complex movements and withstanding repeated biomechanical stresses during actuation. Notably, techniques such as 3D printing, photolithography, and soft lithography are frequently employed to pattern and assemble resin-based components with a high spatial resolution (Fig. 1c). Highly conductive materials were incorporated into the design to support signal transmission and stimulation. CNTs, known for their excellent electrical conductivity and mechanical strength, are frequently embedded in scaffolds to enhance electrical interfaces with muscle tissue47. For example, poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene)-coated multiwalled carbon nanotube sheets have significantly improved the efficiency of electrical stimulation (ES) in engineered muscle constructs, directly contributing to enhanced contractility and responsiveness53. Concurrently, other conductive materials such as gold nanoparticles and liquid metals are used to fabricate flexible and stretchable circuits52. These materials ensure continuous conductivity during motion and support reliable power delivery and signal processing, which are essential for precise control. Together, these abiotic components, including structural resins, hydrogels, conductive polymers, and microfabrication methods, form the physical and functional backbones of biohybrid robots. They enable the synchronized operation of biological actuators and electronic systems, and exemplify the importance of material innovation in advancing the field. As synthetic components continue to evolve, their synergy with biological tissues further enhances the adaptability, precision, and autonomy of next-generation biohybrid robotic systems.

Design principles and fabrications of biohybrid robots

Biohybrid robots are meticulously engineered by integrating living tissues with synthetic materials to achieve nature-inspired6,7 and energy-efficient locomotion54,55 while ensuring physical and chemical compatibility between biological and engineered components. By adopting geometries that emulate propulsive mechanisms, refined over millions of years of evolution, observed in natural organisms such as fish fins or antagonistic muscles, these systems reduce energy consumption and enhance maneuverability. These innovative systems leverage specialized biological functionalities, such as swimming6,7,8,46,47,54,56,57,58,59, walking12,35,45,60,61,62, pumping63,64,65,66, and gripping11,36,67, to imitate and expand upon versatile locomotive strategies found in nature (Fig. 1d and Table 1). In biohybrid systems, rhythmic contractions of the cardiac muscle tissues are prominently employed in applications such as swimming. The biohybrid fish6 shows creation that closely mirrors the propulsion mechanics of real fish by integrating engineered cardiac muscle tissues on each side of a gelatin-based elastomeric body. Conversely, when it comes to tasks that demand high force output and delicate precision, skeletal muscles are particularly advantageous. By designing a biohybrid robot that utilizes an antagonistic pair of skeletal muscle tissues44,53, this arrangement effectively mimics vertebrate-like walking patterns, thereby demonstrating how biological muscle configurations can be harnessed for robotic locomotion. Moreover, the complex architecture of the human hand provides inspiration for advanced gripping mechanisms in these robots, enabling them to perform delicate and precise object manipulation, which is essential for applications, such as surgery or delicate assembly tasks36. Energy efficiency is another critical consideration in the design of a biohybrid robot. Biological tissues can convert chemical energy from nutrients into mechanical energy with efficiencies exceeding 50%58. This attribute presents a significant advantage for autonomous robotic systems in which energy conservation is essential for prolonged operational capabilities55.

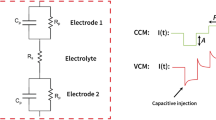

Precise and controllable stimulation strategies are indispensable for fully leveraging the dynamic potential of muscle-based actuators (Fig. 1e). Muscle contraction in these systems can be achieved through (1) spontaneous contractions, which are particularly effective in cardiac muscle-driven swimmers, such as gelatin-based biohybrid fish6. This innovative concept was introduced by researchers, who successfully cultivated and self-assembled cardiomyocytes into muscle bundles. These bundles were subsequently integrated with the micromechanical structures, resulting in a self-assembled microdevice propelled by the cardiac muscle. Autonomous operation of the device was achieved through the spontaneous contraction of cardiomyocytes, which efficiently converted chemical energy into mechanical energy. This groundbreaking demonstration established the feasibility of self-sustaining actuators powered by cardiac muscle60 (2) ES commonly applied in skeletal muscle systems using CNT or gold electrodes36,47,68. ES is a widely used method for controlling the contraction of myocyte-driven robots. By mimicking the bioelectrical transmission of motor neurons, ES induces membrane depolarization, triggering excitation–contraction coupling (ECC) in myocytes69. This technique has been shown to enhance the alignment and differentiation of myotubes, which are both critical factors in generating functional muscle tissues70. For example, a biohybrid robot powered by antagonistic skeletal muscle tissues was developed11, in which ES was used to manipulate object rotation angles and muscle strain by varying the frequency and magnitude of the electrical field11. However, ES presents challenges, such as electrolysis of the culture medium and localized high-voltage electric fields that can damage cells. Innovative electrode designs, such as ring-distributed multielectrodes, have shown promise in mitigating these issues by providing more uniform electric fields and improved differentiation of myotubes compared to conventional parallel electrodes43. (3) optogenetic activation, which allows precise control via light in engineered muscle actuators6,12,15,45,58,71. This technique involves genetically modifying muscle cells to express light-sensitive ion channels such as Channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2) and ChrimsonR, thereby enabling accurate and non-invasive control of muscle contractions via light stimuli. By allowing detailed manipulation of both the spatial and temporal aspects of muscle contraction, optogenetics significantly enhances the functional complexity of biohybrid systems, especially in tasks requiring intricate and adaptive actuation12,58,72. For example, optogenetically modified cardiomyocytes have been employed in a soft robotic ray58 to achieve synchronized and rhythmic swimming through periodic light stimulation58. Similarly, a biohybrid fish6 was developed with an antagonistic muscle bilayer and a self-regulating pacing node, enabling coordinated back and forth fin movements controlled by alternating blue and red light pulses6. However, optical stimulation has drawbacks, including potential heat-related effects and unintended cellular activity due to extended light exposure. These issues necessitate the fine-tuning of light-exposure parameters to maintain cell viability and proper function73,74. And (4) NMJs, which utilize motor neurons to replicate natural synaptic control over muscle movement8,46,75,76. Optogenetically modified motor neurons are employed to actuate biohybrid swimming devices, where light activation triggers muscle contractions that propel the robot8. Additionally, advancements have involved the creation of wirelessly steerable bioelectronic neuromuscular robots. These robots use engineered motor neurons to control cardiac muscle tissues, thereby enabling the modulation of movement through electrical signals46. These methods provide enhanced control and interaction between biological and mechanical components, replicating the intricate control mechanisms observed in living organisms. This enables more sophisticated robotic applications to operate autonomously in dynamic environments. Each method offers distinct benefits in customizing the actuation behavior of biohybrid robots based on the intended application. By combining these biomimetic strategies with robust synthetic frameworks, biohybrid robots can mimic the dynamic movements of living organisms while maintaining reliable performance, even in unpredictable and challenging environments. Collectively, these integrative design principles highlight the transformative potential of biohybrid robots across numerous fields, including medical technology and environmental monitoring. By setting the stage for new paradigms in robotic innovation, biohybrid robots may significantly enhance our ability to address complex challenges across various domains.

Muscle-based actuators: skeletal and cardiac muscle

Skeletal muscle actuators

The skeletal muscle is a primary actuator in biological organisms, distinguished by its modular architecture, scalable design, and remarkable ability to generate significant contractile forces. Structurally, skeletal muscles consist of elongated muscle fibers, each composed of thousands of myofibrils that contain billions of myofilaments organized into repeating units known as sarcomeres, the fundamental contractile units responsible for muscle contraction5,77. These sarcomeres facilitate contraction through intricate interactions between actin and myosin filaments, which are activated by calcium ions released into the cytoplasm in response to neuronal signaling78,79. In vivo, the initiation of skeletal muscle contractions is a finely tuned process triggered by motor neurons that release the neurotransmitter acetylcholine upon the arrival of an action potential. This release leads to depolarization of the sarcolemma, a specialized muscle cell membrane, allowing calcium ions to flow into myotubes, which subsequently activates the actin–myosin cross-bridging machinery77,80. Consequently, these biological processes enable skeletal muscle to produce contractile forces significantly greater than those of cardiac muscle, with specific studies reporting force outputs as high as 2.5 mN under controlled ES81 (Fig. 2a and Table 1). Additionally, the regenerative capacity of skeletal myocytes allows for recovery and repair after injury through the activation of satellite cells, an ability distinctly lacking in cardiomyocytes that do not exhibit comparable regenerative properties82. The unique structural and functional characteristics of skeletal muscles have inspired the development of biomimetic actuators in soft robotics. These artificial muscle-like structures replicate the modular architecture and force-generating capabilities of their biological counterparts. Recent advancements in materials science and engineering have led to the creation of synthetic actuators that can mimic the contractile behavior of skeletal muscles, albeit with limitations in terms of force output and efficiency. Taken together, the unique cellular architecture and contractile potential of skeletal muscles offer clear advantages for use in biohybrid actuation platforms. Unlike cardiac muscles, which operate autonomously and rhythmically, skeletal muscles provide externally controllable, forceful contractions that are highly tunable, making them ideal for precision-oriented tasks in robotics. Furthermore, its modularity and regenerative potential support long-term application and mechanical adaptability in engineered systems. Looking forward, deeper integration of skeletal muscles into robotic systems will likely benefit from coupling with advanced control interfaces, such as neural or optogenetic circuits, and enhanced mechanical scaffolds that guide alignment, maturation, and force propagation. Moreover, leveraging omics-based profiling of muscle cell states may enable predictive tuning of performance characteristics in engineered constructs.

a Electrical stimulation culture system for daily maintenance-free muscle tissue production (scale bar, 10 mm). Adapted with permission from ref. 81, The American Association for the Advancement of Science. AAAS: Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0). b Biohybrid robot powered by an antagonistic pair of skeletal muscle tissues [scale bars = 5 mm (left), 2 mm (right)], adapted with permission from ref. 11, The American Association for the Advancement of Science. c Three-dimensional printed biological machines powered by skeletal muscles (scale bar = 1 mm). Adapted with permission from ref. 35, PNAS. d Multi-actuator light-controlled biological robots [scale bars = 1 mm (left) and 2 mm (right)]. Adapted with permission from ref. 85. AIP Publishing, Creative Commons and CC. e Neuromuscular actuation of the biohybrid motile bots (scale bar = 250 µm). Adapted with permission from ref. 8. PNAS, Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-NoDerivatives License 4.0 (CC BY-NC-ND). f Force Modulation and Adaptability of 3D-Bioprinted Biological Actuators Based on Skeletal Muscle Tissue (scale bar = 100 µm). Adapted with permission from ref. 112, John Wiley and Sons.

Skeletal muscle characteristics and advantages

Skeletal muscle actuators are exceptionally effective in applications demanding precise motion control and substantial force output. Their hierarchical structure, which incorporates various fiber types and connective tissues, facilitates scalable force generation and quick activation/deactivation. This adaptability renders skeletal muscles particularly appropriate for incorporation into biohybrid systems, including soft robotics and prosthetic devices, which strive to emulate natural movement patterns4. Distinguishing itself from the cardiac muscle, skeletal muscles have an innate ability to self-repair. This regenerative capacity is facilitated by satellite cells, which are activated in response to mechanical damage or stress, thereby enabling biohybrid robots to recover from injuries more effectively15. The combination of fine control, adaptability, and regenerative properties positions the skeletal muscle as an optimal choice for robotic systems that demand coordinated spatial and temporal movements, such as in dynamic environments or in tasks requiring delicate manipulation. The structural hierarchy and fiber-type diversity of skeletal muscles provide a biologically optimized framework for scalable fast-response actuation. Their ability to regenerate through satellite cell activation offers a significant advantage over non-regenerative tissue types, particularly in long-term or damage-prone environments. These features collectively position skeletal muscle as a uniquely versatile component in the design of biohybrid actuators. Future biohybrid systems may exploit the regenerative properties of skeletal muscle not only for mechanical recovery, but also as a foundation for self-healing robotic platforms. Incorporating cell-responsive materials that dynamically modulate mechanical cues could further enhance the interplay between synthetic scaffolds and biological tissues during both operation and repair.

Challenges

Despite these advantages, skeletal muscles face long-term stability and energy-efficiency challenges. Engineered skeletal muscle derived from cell lines often shows lower contractile performance compared to native tissue, achieving only 1–5% strain and ~1 kPa of stress, in contrast to 20% strain and 0.5 MPa stress in vivo12,30,83,84. Some studies have suggested that using primary cells or improving biofabrication methods could help close this performance gap11 (Fig. 2b and Table 1). Additionally, the metabolic demands of skeletal muscle and its reliance on vascularization and innervation are significant challenges to scalability and sustained functionality4. Efforts to bridge this performance gap have included the utilization of primary muscle cells, which more closely replicate native muscle properties, as well as advancements in biofabrication techniques that enhance the tissue architecture. Furthermore, the intrinsic metabolic demands of skeletal muscle, combined with its dependence on adequate vascularization and innervation, pose considerable hurdles for scalability and sustained functionality in biohybrid systems4. These challenges necessitate ongoing research and innovation to optimize skeletal muscle integration for practical application. The difference in contractile efficiency, strain, and stress between engineered and native muscles underscores the importance of improving both cellular sources and fabrication strategies. Vascularization and neuromuscular integration remain critical bottlenecks that limit long-term functionality and scalability. Addressing these limitations will likely involve the convergence of tissue engineering, biomaterial science, and synthetic biology. Approaches, such as pre-vascularized scaffolds, microfluidic perfusion systems, and genetic enhancement of energy metabolism, may help overcome metabolic constraints. Long-term machine-learning-based feedback systems may also be employed to optimize contractile performance through adaptive stimulation and environmental conditioning.

Applications

Skeletal muscle actuators are extensively used in various biohybrid robots, including walkers, grippers, and swimmers. For example, 3D-engineered skeletal muscle has powered walking robots that can achieve locomotion speeds of up to 1.5 body length per minute under electrical or optical control35,85 (Fig. 2c, d). Grippers that utilize agonist–antagonist muscle pairs can manipulate objects with a rotational range of ~100°, showcasing the adaptability of skeletal muscles in performing dexterous tasks11 (Fig. 2b). Skeletal muscles have also been integrated into swimming robots, where optogenetic muscle-neuron systems allow for precise control over trajectory and velocity, achieving speeds of ~1 µm/s8 (Fig. 2e). These examples highlight the versatility and precision of skeletal muscles in various robotic applications. Ongoing advancements in biofabrication methods, such as 3D bioprinting and electrospinning, have enhanced skeletal muscle actuators by refining their alignment and maturation processes85,86 (Fig. 2f). As robots powered by skeletal muscles continue to evolve, the incorporation of additional cell types, particularly motor neurons, can enhance their adaptability and functionality. These innovations pave the way for the development of intelligent biohybrid systems capable of dynamic, autonomous operation in challenging environments. These applications demonstrate the remarkable versatility of skeletal muscle actuators across diverse robotic modalities, from walkers and swimmers to grippers capable of fine manipulation. The compatibility of skeletal muscles with optical and ES platforms, combined with their mechanical strength and responsiveness, enables a wide range of design possibilities for next-generation soft robotics and humanoids. As fabrication techniques, such as 3D bioprinting and electrospinning, continue to mature, the precision and scalability of skeletal muscle actuators will be greatly enhanced. Future systems may incorporate complex neuromuscular networks, enabling autonomous decision-making and environmental adaptation. Ultimately, skeletal muscle-driven robots can be used in real-world applications, such as surgical robotics, prosthetic augmentation, or remote exploration in unstructured terrains.

Cardiac muscle actuators

Cardiac muscle is widely regarded as an excellent actuator for biohybrid robotics because of its intrinsic system and inherent capacity to spontaneously generate rhythmic contractions without external stimuli6,7,63 (Fig. 3a–c). This property is vital for continuous and stable motion in applications, such as heart-inspired pumping devices or biomimetic swimmers inspired by efficient aquatic locomotion. At the cellular level, cardiomyocytes form a syncytium via intercalated discs containing gap junctions that facilitate rapid electrical coupling and coordinated contractions87. Each action potential begins with a swift influx of Na⁺, leading to depolarization, followed by a sustained plateau phase mediated by Ca²⁺ influx, and concludes with repolarization driven by K⁺ efflux88. This electrochemical sequence supports ECC, wherein Ca²⁺ triggers the sliding filament mechanism in sarcomeres and the fundamental contractile units87,89. Notably, high-resolution assays using nanopatterned microelectrode arrays (MEAs) have captured transient action potentials in cardiomyocyte monolayers, highlighting their autorhythmic behavior90,91. To enhance the directional control of cardiac muscle performance in engineered systems, researchers have devised microengineered substrates that replicate the anisotropic architecture of native cardiac tissue. For instance, culturing cardiomyocytes on microgrooved or micropatterned surfaces can improve cell alignment and elevate contractile efficiency by up to 20% compared to unpatterned substrates48. When integrated with flexible polymers such as PDMS, gelatin-hydrogel substrates enable biohybrid devices capable of controllable fluid pumping63 (Fig. 3c) and lifelike swimming6,7,58 (Fig. 3a, b, d). However, external control often remains critical for tailoring cardiomyocyte function for specific needs. ES can synchronize beating, tissue maturation, and force output6,58 (Fig. 3a, d). In parallel, optogenetic methods, in which cells are genetically modified to express light-sensitive ion channels (e.g., ChR292, ChrimsonR93), allow remote, finely tuned control over contraction timing and amplitude6,30 (Fig. 3a). These techniques offer high spatial and temporal precision, which is essential for orchestrating complex actuation patterns in biohybrid robots. Despite notable progress, several obstacles remain before engineered cardiac tissues can match the maturity of native myocardium. Although highly functional, primary cardiomyocytes face challenges in terms of scalability and regeneration, fueling research on hiPSC-derived cardiomyocytes. However, these hiPSC-based tissues frequently exhibited immature electrophysiological attributes6,94 (Fig. 3a, e). Current efforts involve exercise-inspired training regimes, including cyclic mechanical stretching and biochemical modulation, to boost differentiation and contractile power95. These attributes make them especially well-suited for continuous, synchronized tasks such as pumping and swimming, underscoring their central role in the emerging generation of biohybrid robotic systems7,96 (Fig. 3b).

a An autonomously swimming biohybrid fish designed with human cardiac biophysics [scale bar = 5 mm (left), 50 µm (right), 5 mm(bottom)], Adapted with permission from ref. 6, The American Association for the Advancement of Science. b Tissue-engineered jellyfish with biomimetic propulsion [scale bar, 1 mm (left), 5 µm (middle left), 10 µm (middle right), 50 µm (right)], adapted with permission from ref. 7, Springer Nature. c A microspherical heart pump powered by cultured cardiomyocytes (scale bar = 3 mm), adapted with permission from ref. 63, Royal Society of Chemistry. d Phototactic guidance of a tissue-engineered soft robotic ray (scale bar = 5 mm), adapted with permission from ref. 58, The American Association for the Advancement of Science. e Electrically Driven Microengineered Bioinspired Soft Robots (scale bar = 5 mm). Adapted with permission from ref. 113, John Wiley and Sons.

Cardiac muscle actuators

Cardiac muscle characteristics and advantages

Cardiomyocytes possess two key electrophysiological and mechanical characteristics, which are vital for their use in biohybrid robotics. From an electrophysiological perspective, these cells are distinct in their capacity to produce action potentials through the complex interaction of ion channels. This process involves the sequential activation of inward sodium (Na⁺) and calcium (Ca²⁺) channels, followed by inactivation and activation of outward potassium (K⁺) channels88. This inherent property, termed autorhythmicity, results in spontaneous and rhythmic electrical activity, which is essential for heart function. Such electrical activity can be precisely monitored using advanced sensor technologies such as MEAs. Mechanically, the action potential in cardiomyocytes triggers a process known as ECC, in which calcium ions (Ca²⁺) are essential for converting electrical signals into mechanical force generation87,89. Cardiomyocytes typically measure 10–25 µm in diameter and can extend up to 100 µm in length, with contraction amplitudes ranging from 2 to 15 µm. These contraction properties are highly dependent on the availability of extracellular Ca²⁺ levels97,98. Cardiac tissue is well known for its remarkable contractile capabilities, allowing it to undergo numerous actuation cycles with minimal fatigue. Various methods have been demonstrated to enhance this contractile force, including the development of microgrooved surfaces and the application of mechanical stimulation. These findings illustrate how physical factors enhance cardiomyocyte efficiency48,52. Additionally, studies have indicated that engineered cardiac tissue can produce contractile stresses ranging from 10 to 50 kPa when adhered to microgrooved gelatin hydrogels, further highlighting the material’s capabilities49. The synchronized contraction of cardiomyocytes, facilitated by intercellular connections known as gap junctions, makes cardiac tissue an exceptional biomimetic material for applications requiring continuous and rhythmic motion, such as the design of pumping mechanisms and swimming robots28,63 (Fig. 3c). The integration of these properties makes cardiomyocytes a vital component in the advancement of biohybrid robots and engineered tissue systems.

Challenges

Cardiac muscles face several significant challenges in biohybrid robotics, particularly when engineered tissues are integrated into functional robotic systems. Early studies utilizing primary cardiomyocytes showed performance levels that approached those of native cardiac tissue, as demonstrated30. However, factors such as scalability, limited availability of primary cells, and long-term sustainability of these tissues have proven to be persistent hurdles63,94,95 (Fig. 3c, e). Recent advancements have turned to hiPSCs for generating cardiac tissue, which have shown promising developments in terms of functional performance and structural organization. Despite these improvements, the engineered tissues often exhibit a level of maturity that remains inadequate compared to that of in vivo cardiac tissues, as highlighted by previous studies6,94 (Fig. 3a, e). These engineered tissues often display immature electrophysiological properties and contractile functions, which impede their ability to mimic the robust performance required in living organisms. To address tissue maturity and enhance functional output, researchers have proposed exercise-based training regimens that can stimulate the development of engineered cardiac muscles. These regimens include mechanical stretching, ES, and biochemical cues that promote differentiation and maturation. Nonetheless, further refinement is essential to fully overcome the ongoing limitations associated with tissue functionality and integrated performance95. Moreover, the intrinsic cardiac dependence on tightly regulated environmental conditions, such as optimal temperature, precise pH levels, and adequate oxygen supply, presents substantial obstacles for seamless long-term integration into biohybrid robots. Maintaining these conditions externally during robotic operations is essential because fluctuations can adversely affect cardiac function. Achieving fine-tuned control over these environmental factors, along with enabling autonomous operation under dynamic and potentially unpredictable conditions, remains a core challenge for the development of efficient biohybrid robotic systems.

Applications

The ability of the cardiac muscle tissue to contract and generate force has made it an essential element in the creation of pump-like biohybrid systems. Researchers have developed a novel design featuring a hollow elastomeric sphere encased in a two-dimensional cardiac muscle sheet63 (Fig. 3c). This innovative approach successfully replicated the functional characteristics of natural hearts, producing pulsatile flow rates between 0.01 and 0.1 μL/min through downstream capillary tubes63 (Fig. 3c). Biohybrid swimmers inspired by the movements of aquatic animals such as jellyfish, stingrays, and spermatozoa have been successfully developed using synchronized contractions of the cardiac muscle. A robotic model that mimics the motion of a jellyfish was created by employing cardiomyocytes to achieve rhythmic propulsion in water7 (Fig. 3b). Furthermore, submillimeter-scale robots were crafted, driven by contractile cardiomyocytes and epidermal progenitor cells, allowing them to swim directionally at ~20 μm/s, demonstrating the effectiveness of cardiac muscles in small-scale robotics99. These engineered cardiac tissues also include fluorescent reporters, enabling robots to detect and signal environmental interactions, thereby broadening their potential applications in exploration and monitoring100. Cardiac muscles have also been effectively integrated into robotic systems for crawling and gripping purposes. Notable advancements have been achieved by combining engineered cardiac tissue with soft robotic structures, facilitating various movements, particularly crawling and gripping actions, which are essential for a range of robotic applications101,102. The use of cardiac muscle actuators holds exceptional promise for a variety of continuous rhythmic tasks in biohybrid robotics. Ongoing research has focused on enhancing tissue maturation, boosting environmental resilience, and scaling these systems for greater applicability. Essential advancements in conductive scaffolds are expected to improve the integration of cardiac tissues into robotic frameworks, whereas developments in wireless power technologies will facilitate a more efficient energy distribution. Moreover, optogenetic techniques are anticipated to play a pivotal role in enhancing the performance of cardiomyocyte-based systems, allowing for finer control over muscle contraction and movement47,103,104. Beyond their practical applications, cardiomyocyte-driven robots serve as valuable experimental models for investigating fundamental biological processes, such as ECC, effectively bridging the disciplines of robotics and life sciences, and paving the way for future innovations.

Comparisons and synergies

Skeletal and cardiac muscles exhibit distinct strengths that cater to various applications in biohybrid robotics, each offering unique advantages based on their physiological properties and functional characteristics. The skeletal muscle is characterized by its hierarchical architecture, which includes well-organized muscle fibers, connective tissue, and NMJs that facilitate precise contraction control. This intricate structure allows for fine-tuned, on-demand motion, making skeletal muscles particularly advantageous for tasks that require coordinated spatial and temporal movements. Activities such as walking, crawling, and gripping require a high degree of accuracy and responsiveness, which skeletal muscles can deliver because of their direct connection with motor neurons43. Furthermore, skeletal muscle possesses remarkable regenerative capacity through satellite cells and progenitor cells that enable repair and growth after injury, ensuring robust long-term functionality and resilience against wear and tear82. In contrast, the cardiac muscle is uniquely suited for continuous, rhythmic operations because of its intrinsic property of autorhythmicity and the coordinated synchronization of its contractions. These features render cardiac muscles particularly effective in applications requiring prolonged repetitive actuation, such as pumping fluids or facilitating locomotion in soft robotic systems designed for swimming7,63 (Fig. 3b, c). The ability of cardiac muscle to sustain millions of contraction cycles without experiencing fatigue underscores its durability and reliability, making it an ideal candidate for long-duration tasks6,105 (Fig. 3a). The combination of skeletal and cardiac muscles in a hybrid actuator design presents an innovative solution to the limitations associated with each muscle type when used in isolation. The controllability and precision of skeletal muscle complement the endurance and rhythmic efficiency of cardiac muscle, allowing for the development of multifunctional systems that exhibit complex yet energy-efficient behaviors. For instance, an underwater exploration robot can utilize cardiac muscles to achieve sustained swimming capabilities while employing skeletal muscles for precise navigation through complex underwater environments and for intricate object manipulation. In the healthcare sector, integrating skeletal muscle for targeted drug delivery systems with the robust fluid-pumping capabilities of cardiac muscle could pave the way for groundbreaking therapeutic methods for drug administration or localized treatment.

To create these hybrid systems, it is essential to properly align the contraction patterns and mechanical linkages between the skeletal and cardiac tissues. Tackling the distinct environmental and metabolic requirements of each muscle type poses a significant technical challenge. Progress in tissue engineering, especially in developing robust biotic–abiotic interfaces and improving vascularization methods, is essential for overcoming these obstacles. By leveraging the complementary features of skeletal and cardiac muscles, hybrid biohybrid actuators have been poised to significantly enhance the capabilities of robotic systems. This collaboration not only enhances the performance of existing robotic platforms but also opens up new possibilities in fields such as medical diagnostics, environmental exploration, and advanced manufacturing processes. For example, one might imagine a biohybrid robot inspired by an octopus using cardiac muscle for smooth movement in its tentacles and skeletal muscle for precise, powerful manipulations, making it perfect for internal sensors for diagnosis or healing internal injuries. As research in this field advances, the integration of various muscle types is expected to become a fundamental aspect of biohybrid robotics, combining biological complexity with groundbreaking and novel engineering innovations.

Locomotion and current challenges in biohybrid robotics

Swimmers

Swimming robots that mimic the locomotion of marine organisms are vital for advancing our understanding of biological movements and for improving robotic designs. These systems combine biology and engineering, fostering the exploration of natural swimming strategies and their potential technological applications. They provide insights into efficient and adaptive movements that are useful for tasks, such as environmental monitoring and underwater exploration. Additionally, the development of these robots has advanced material science and synthetic biology, facilitating the creation of more autonomous and versatile robotic systems capable of operating in complex aquatic environments. Aquatic biohybrid robots mimic the swimming patterns of various organisms, including jellyfish, stingrays, and spermatozoa. A jellyfish-inspired robot utilizing cardiomyocytes has achieved coordinated propulsion through rhythmic contractions7 (Fig. 4a), offering a new perspective on energy-efficient marine locomotion. Furthermore, a ray-inspired biohybrid robot driven by optogenetic cardiomyocytes generated a steady forward thrust via controlled fin oscillations58, showing significant potential for precise maneuverability in fluid environments (Fig. 4b).

a Medusoids engineered to exhibit jellyfish-like stroke kinetics (scale bar = 1 mm). Adapted with permission from ref. 7, Springer Nature. b Phototactic steering of the tissue-engineered ray through an obstacle course [scale bar = 20 (left top), 2 mm (left bottom), 500 µm (middle), and 50 µm (right)]. Adapted with permission from ref. 58, The American Association for the Advancement of Science. c Bright-field images of swimmers after release from the anchors. The neurosphere is dislocated from its original seeding location owing to tension generated between the muscle and neurons [scale bar = 500 µm (left), 250 µm (right)]. Adapted with permission from ref. 8, PNAS, Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-NoDerivatives License 4.0 (CC BY-NC-ND). d Biohybrid soft robots with self-stimulating skeletons [scale bar = 100 µm (left), 3 mm (middle), 10 mm (right)]. Adapted with permission from ref. 9, The American Association for the Advancement of Science. e Autonomous BCF propulsion of a biohybrid fish designed using human cardiac biophysics (scale bar = 5 mm). Adapted with permission from ref. 6, The American Association for the Advancement of Science. f Free-floating ray during diastole and systole [scale bar = 20 µm (left), 500 µm (right)]. Adapted with permission from ref. 54, The American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Significant progress has been made in the utilization of skeletal muscles combined with motor neurons to enhance the control and efficiency of biohybrid swimmers8 (Fig. 4c). This integration allows for precise modulation of swimming trajectories and speeds, mimicking the natural swimming actions of small aquatic organisms. The integration of skeletal muscle with serpentine spring skeletons has enhanced both directional swimming capabilities and force output, allowing swimmers to achieve speeds up to 800 micrometers per second9 (Fig. 4d). This mechanical advantage is essential for effective propulsion and demonstrates the potential of skeletal muscles in aquatic applications. Additionally, the biohybrid fish, designed with human cardiac biophysics, swims autonomously by leveraging engineered cardiac muscle tissues that contract rhythmically6 (Fig. 4e), providing valuable insights into both natural aquatic locomotion and the potential for advanced robotic applications. Researchers have also utilized a machine-learning-based optimization (ML-DO) method to enhance biohybrid fin geometries for aquatic locomotion54 (Fig. 4f). This approach combines a genetic algorithm with a neural network framework to explore an extensive design space and identify fin shapes that optimize swimming performance. The refined configurations exhibited efficiencies near those of natural swimmers, closely following the established locomotive scaling laws. This technique not only outperforms conventional derivative-free optimization methods but also offers valuable insights into the structure–function relationships underlying effective propulsion in biohybrid systems.

Grippers

Biohybrid robotic grippers have evolved to mimic the complex movements of the human hand, thereby enhancing their application in precision tasks such as medical procedures and fine manufacturing. The integration of skeletal muscle actuators with flexible polymer structures enables these devices to precisely handle a variety of textures and shapes, making them ideal for both biomedical and industrial settings. The development of an agonist–antagonist muscle pair in biohybrid robotic grippers represents a significant advancement in robotic manipulation, offering precise control over rotational movement. This design mimics the natural muscle arrangements found in biological systems, allowing grippers to handle objects with enhanced precision and stability11 (Fig. 5a). This arrangement is essential for tasks that require high levels of dexterity and fine motor control, making these grippers highly effective for detailed and delicate operations in both medical and industrial applications. The ability to precisely control rotational angles extends the functionality of these grippers, providing them with the capability to perform complex manipulative tasks that were previously challenging for traditional robotic systems. Further advancements are exemplified by the Multiple Muscle Tissue Actuator (MuMuTA), a state-of-the-art system that uses bundles of human skeletal muscle strands arranged in a novel in-sheet formation36 (Fig. 5b). This design not only ensures consistent cell alignment and reduces cell death but also enables precise multi-joint finger actuation through a cable-driven mechanism. MuMuTA achieves a notable contractile force and has been engineered to address nutrient diffusion challenges, significantly enhancing the functional capabilities and longevity of biohybrid actuators. These innovations reflect the significant progress in the design and functionality of biohybrid robotic grippers, offering enhanced performance and expanding their utility in sensitive and precise operational environments.

a Object manipulations performed by an antagonistic pair of skeletal muscle tissue biohybrid robots [scale bar = 5 mm (left), 5 mm (middle), and 1 cm (right)]. Adapted with permission from ref. 11, The American Association for the Advancement of Science. b Biohybrid hand actuated by multiple human muscle tissues (scale bar = 1 cm) adapted with permission from ref. 36, The American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Walker

Biohybrid walkers, designed to emulate the complex locomotion of living organisms, employ skeletal muscle actuators to enhance navigation across diverse terrains and improve interactions with their environments. These actuators, adept at producing significant force and precise movements, facilitate the integration of engineered skeletal muscle tissues into robotics, resulting in adaptable, efficient, and versatile platforms capable of performing tasks similar to those of living organisms, thereby expanding the potential applications from environmental exploration to healthcare. In the early stages, self-assembled microdevices demonstrated the potential of biohybrid systems by integrating individual cardiomyocytes into microfabricated structures to create autonomous walking systems. This setup used the intrinsic contractile activity of cells on a flexible substrate to mimic muscular and skeletal interactions. Coordinated muscle cell contractions drive the microdevice forward, enabling it to traverse various surfaces and simulate walking motion, showcasing the biohybrid’s ability to mimic complex locomotive functions on a miniature scale60 (Fig. 6a). Following this, miniaturized walking biological machines began to utilize biohybrid systems with microfabrication technologies, incorporating a combination of hydrogels and cardiomyocytes. These devices feature a cantilever structure acting as a muscle actuator, supported by a sturdy base for movement control. The natural contractile forces of the cardiomyocytes propelled the device, and the cantilever design was optimized to balance friction and propulsion for controlled movement61 (Fig. 6b). Recent developments have seen significant advancements in the use of hydrogel scaffolds and muscle tissues that enhance force production and motility in soft biological robotic actuators. The functional output was significantly increased by varying scaffold geometries and cellular constructs. Computational design has led to the fabrication of biological machines capable of generating millinewton forces, driving locomotion at speeds over 0.5 mm/s. The strong correlation between computational predictions and experimental outcomes has highlighted the potential for designing advanced biohybrid systems with the aim of solving real-world problems in fields such as medicine, environment, and manufacturing62 (Fig. 6c). Further integration of bioengineering techniques with 3D scaffolds has led to the development of biohybrid robots that combine living cellular components with onboard electronics and remote control, significantly enhancing functionality for applications in engineering, biology, and medicine. Equipped with wireless control through microinorganic LEDs, these robots can perform complex tasks, such as walking, turning, and transporting objects at individual and collective levels45 (Fig. 6d). Finally, the latest advancements include the development of a bipedal robot powered by cultured skeletal muscle tissues capable of performing fine maneuvers, such as turning in small circles. This robot integrates a float to maintain an upright posture in a culture medium, a PDMS body that includes two flexible substrates, and 3D-printed legs with muscle tissues. Despite the challenges in the manual method required for ES, which significantly slows the forward speed of the robot, the potential for precise and efficient movement remains promising, demonstrating the capability of skeletal muscle actuators in biohybrid robotic applications10 (Fig. 6e).

a Self-assembled microdevices driven by muscle (scale bar = 100 µm), Adapted with permission from ref. 60, Springer Nature. b Development of miniaturized walking biological machines (scale bar = 1 mm) adapted with permission from ref. 61, Springer Nature. Commons license (Attribution-Noncommercial). c Simulation and Fabrication of Stronger, Larger, and Faster Walking Biohybrid Machines [scale bar = 1 mm (top), 2 mm (middle bottom)]. Adapted with permission from ref. 62, PNAS. d Remote control of muscle-driven miniature robots with battery-free wireless optoelectronics [scale bar = 5 mm (top) and 1 cm (bottom)]. Adapted with permission from ref. 44. The American Association for the Advancement of Science. e Device stimulation of a geometrically symmetric two-leg bio-bot showed zero net locomotion predicted via finite element analysis and confirmed via electrical stimulation [scale bar = 1 mm (top), 2 mm (bottom)]. Adapted with permission from ref. 12, PNAS. f Biohybrid bipedal robot powered by skeletal muscle tissue [scale bar = 0.5 mm (top), 5 mm (bottom)]. Adapted with permission from ref. 10, Elsevier.

Pumping

Biohybrid pumping systems aim to replicate the natural pumping mechanics of the human heart by employing biological actuators such as cardiomyocytes to enhance the precision and efficiency of microscale fluid dynamics. These systems are pivotal in advancing applications from micropumps to lab-on-a-chip systems by integrating biological elements that offer adaptive responses, which are ideal for drug delivery and medical diagnostics. Cardiomyocytes cultured on stretchable membranes are employed to create microspherical heart pumps that deliver controlled pulsatile flow, which is indispensable for microfluidic systems and medical devices63 (Fig. 7a). Further refining this approach, cardiomyocytes directly seeded on diagonally stretched thin membranes facilitated effective fluid oscillation, achieving flow rates suitable for integrating precise fluid control into drug delivery systems and miniature organ models64 (Fig. 7b). The incorporation of CNTs into gelatin methacrylate (GelMA) hydrogels enhances the electrophysiological properties of cardiac tissues, forming electrically conductive and nanofibrous networks that improve cell adhesion and electrical signaling, which are critical for robust cardiac function47 (Fig. 7c). Innovative valveless pump bots, utilizing synchronized contractions of engineered cardiac tissues, demonstrate precise fluid movement through capillary-like structures, effectively expanding their application in sophisticated lab-on-a-chip technologies and targeted drug delivery systems65 (Fig. 7d). Each of these advancements has been built on previous developments, continually enhancing the sophistication and functionality of biohybrid pumping systems. These developments show the progressive evolution of biohybrid robots in effectively emulating and augmenting physiological functions, such as the pumping action of the heart, and point towards a future where these technologies could provide novel solutions across various applications in medicine and beyond.

a Microspherical heart-like pump powered by spontaneously contracting cardiomyocyte sheets driven without the need for external energy sources or coupled stimuli (scale bar = 3 mm). Adapted with permission from ref. 63, Royal Society of Chemistry. b Fluid actuation for a bio-micropump powered by previously frozen cardiomyocytes directly seeded on a diagonally stretched thin membrane [scale bar = 5 mm (top), 1 mm (bottom)], adapted with permission from ref. 64, Elsevier. c Carbon-Nanotube-Embedded Hydrogel Sheets for Engineering Cardiac Constructs and Bioactuators (scale bar = 5 mm, ruler marking is 1 mm), adapted with permission from ref. 47, Copyright American Chemical Society. d Biohybrid valveless pump-bot powered by engineered skeletal muscle. Adapted with permission from ref. 65, PNAS Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-NoDerivatives License 4.0 (CC BY-NC-ND).

Current advances and remaining challenges in biohybrid robotics

Biohybrid robotics has made substantial progress by integrating living tissues with synthetic systems to enable biologically inspired actuation, adaptability, and energy efficiency. Despite these strides, several critical challenges hinder scalability, robustness, and autonomous functionality, which are essential for industrial applications and long-term deployment. These challenges are not isolated but rather interconnected across biological tissue engineering, material science, energy management, and neuromechanical control. Addressing these issues requires synergistic advancements across multiple disciplines.

Stability, maturation, and longevity of engineered tissues

One of the foremost bottlenecks lies in the intrinsic instability of the engineered muscle tissues over time. Both skeletal and cardiac muscle constructs often exhibit spontaneous shrinkage, compromised alignment, and loss of contractile function during extended culturing. These shortcomings limit the mechanical reliability and practical integration of these materials into robotic platforms. Furthermore, current constructs frequently fail to recapitulate the hierarchical organization, vascularization, and mechanical endurance observed in native tissues. To overcome these limitations, researchers are exploring dynamic culture systems involving mechanical loading, ES, and the incorporation of vascular networks. Scaffolds designed with a biomimetic architecture and material stiffness also contribute to improved alignment and force generation. Achieving long-term functional maintenance and reproducibility remains a major research topic.

Biotic–abiotic interface integration

At the core of biohybrid design, there is a need for seamless and stable integration between living tissues and synthetic frameworks. These interfaces must withstand mechanical stress while enabling effective communication between the biological actuator and robotic body—electrical, mechanical, or biochemical. Current interfaces, which are often based on soft elastomers or rigid electrodes, tend to suffer from signal attenuation, mechanical mismatch, or degradation over time. Recent innovations in stretchable electronics, conductive hydrogels, and organic bioelectronics have improved mechanical compliance and signal fidelity. Furthermore, the incorporation of real-time bioelectronic feedback loops is essential for translating muscle contractions into controlled robotic motion. Nevertheless, achieving long-term biocompatibility and responsiveness under dynamic conditions remains a critical engineering challenge.

Maintaining the viability and functionality of biological components in biohybrid systems requires a combination of advanced tissue engineering and integration strategies. Engineered muscle tissues are typically cultured within hydrogel matrices such as fibrin, GelMA, or Matrigel, which mimic the native ECM and support cell alignment, proliferation, and contractility4,47. To preserve long-term tissue function, perfusion systems or dynamic bioreactors have been employed to facilitate nutrient exchange, waste removal, and mechanical stimulation49,53. Additionally, microgrooved scaffolds and cyclic stretching regimens have been shown to improve sarcomere organization and force output, particularly in cardiac constructs48. For effective signal transduction, biological tissues are interfaced with conductive materials such as gold nanofilms, CNTs, or PEDOT-coated microelectrodes, which transmit electrical or optogenetic stimuli while preserving cellular integrity43,106. Recent studies have also implemented soft, stretchable bioelectronic systems that minimize the mechanical mismatch and enable real-time feedback during actuation43,106. These integration strategies are critical for ensuring stable performance and represent a central engineering challenge for deploying biohybrid systems under real-world conditions.

Energy autonomy and metabolic integration

Sustaining living tissues requires a continuous supply of glucose, oxygen, and other nutrients, which is an energetically demanding requirement that limits the autonomy of biohybrid robots. Most current systems rely on tethered setups or external perfusion systems, which restrict their mobility and applicability in real-world environments. Emerging strategies now focus on integrating microfluidic networks that mimic vascular systems, enabling localized nutrient delivery and waste removal. In parallel, energy-harvesting approaches, such as photovoltaic, piezoelectric, and enzymatic biofuel systems, are being explored to provide on-board power. These technologies hold promise for developing self-sustaining constructs capable of long-term untethered operations. Design optimization, driven by computational modeling and machine learning, also plays a role in enhancing energy efficiency and metabolic balance.

Neuromuscular control and feedback systems

Most biohybrid actuators rely on spontaneously beating cardiomyocytes or passively contracting muscle tissues, which offer limited control and adaptability. Autonomous systems intended for real-world interactions require sophisticated neuromuscular control that integrates sensory inputs and motor outputs in a closed feedback loop. Although efforts have been made to co-culture sensory neurons with muscle fibers or interface optogenetic systems, achieving robust and functional synaptic connectivity remains technically complex107,108. The development of stable modular neuromuscular units that can be integrated with robotic logic systems is a key step towards intelligent and context-aware biohybrid devices.

Compared with conventional non-biohybrid medical robots, biohybrid systems offer several unique advantages and limitations that warrant explicit comparison. Traditional robots are often entirely composed of rigid components, motors, and sensors that excel in durability, programmability, and consistent performance across extended operational cycles18,20. However, they frequently lack the biocompatibility, flexibility, and adaptive responsiveness required in dynamic biological environments25,30. In contrast, biohybrid robots leverage living tissues to achieve soft, compliant motion and environmentally responsive behaviors that are difficult to replicate using synthetic systems4. The integration of muscle tissues allows autonomous or reflexive adaptation to mechanical cues, which is particularly beneficial in applications such as soft surgical manipulators, implantable devices, and prosthetics4,30. Nevertheless, reliance on biological components imposes trade-offs in terms of stability, long-term functionality, and environmental sensitivity. Issues such as tissue dehydration, immune rejection, and degradation remain unresolved barriers to their deployment outside controlled laboratory conditions25. A hybrid framework that merges the mechanical robustness of conventional robotics with the intelligent adaptability of bioactuators could represent a promising future direction, bridging the performance gap while leveraging the best performance of both paradigms18,30.

True autonomy in biohybrid systems depends on their abilities to sense, interpret, and respond to environmental stimuli. Currently, most systems lack embedded sensors or adaptive control mechanisms, resulting in preprogrammed or open-loop behaviors. Integrating biologically inspired sensors, such as mechanoreceptors, chemosensors, or engineered optogenetic modules, can enable the dynamic modulation of actuation. Moreover, coupling these inputs with responsive neural networks or microcontrollers has the potential to create closed-loop architectures, allowing the system to learn, adapt, and optimize its behavior over time. Such integration would mirror the key aspects of natural sensorimotor systems and move biohybrid robots closer to functional autonomy.

Conclusion

Skeletal and cardiac muscle actuators offer distinct yet complementary capabilities for powering biohybrid robots. Skeletal muscle tissue provides rapid, on-demand contractions with fine-grained control and scalable force output, similar to voluntary movement, whereas the cardiac muscle is intrinsically rhythmic and self-pacing, ideally suited for continuous pumping or oscillatory motions4. Harnessing these differences in tandem can imbue robotic systems with multifunctional abilities, such as leveraging cardiac muscle rhythmic contractions for fluid pumping and circulation while utilizing skeletal muscle precise actuation for locomotion or gripping tasks. Recent demonstrations have highlighted a spectrum of muscle-powered robots capable of walking, swimming, pumping, and gripping, underscoring the synergy between muscle types in engineered devices. Integrating living muscles not only endows machines with lifelike motion and adaptability but also creates physiologically relevant platforms that bridge robotics and muscle biology, offering insights into muscle function under real-world mechanical demands.

Despite these advances, several interdisciplinary research gaps must be addressed to fully realize autonomous, robust biohybrid robots. Material integration remains a core challenge: engineered muscles require supportive scaffolds and interfaces that transmit forces effectively while sustaining cell viability and alignment. Developing robust abiotic–biotic interfaces is critical for long-term functions outside controlled environments. Similarly, neuromuscular control strategies are in their infancy; current muscle-driven systems often rely on external electrical or optical stimuli and lack the refined control of natural motor neurons77. Future designs must incorporate more sophisticated control loops, such as embedded sensors, on-board processors, and even co-cultured neural networks, to achieve closed-loop control and adaptive behavior. Advances in optogenetics and bioelectronics are promising steps towards untethered operation, enabling biohybrid robots to sense and respond to their environments without continuous human or computer intervention. Addressing these gaps will require tightly coupled efforts across biomechanics, cell biology, materials science, and control engineering.

Translating current prototypes into practical technologies also requires prioritizing key research directions and resources. (i) Tissue maturation: Enhanced maturation protocols are needed to achieve adult-like contractile strength and endurance in engineered muscles (e.g., through optimized growth factors, mechanical conditioning, and electrical pacing)30. (ii) Scalable fabrication: New biofabrication methods (such as 3D bioprinting and high-throughput tissue culture) must be developed for the consistent, large-scale production of muscle actuators. (iii) Real-world stability: Strategies to maintain cell viability and function outside the incubator are important; for instance, microfluidic perfusion or vascularization techniques to deliver nutrients and oxygen and protective encapsulation to prevent desiccation or contamination. Progress in these areas will improve the performance, longevity, and manufacturability of biohybrid devices, thereby bringing them closer to deployment in diverse settings.