Abstract

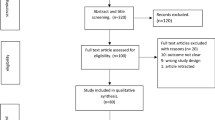

Since 2002, three novel coronavirus outbreaks have occurred: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV-1), Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), and SARS-CoV-2. A better understanding of the transmission potential of coronaviruses will result in adequate infection control precautions and an early halt of transmission within the human population. Experiments on the stability of coronaviruses in the environment, as well as transmission models, are thus pertinent.

Here, we show that transgenic mice expressing human DPP4 can be infected with MERS-CoV via the aerosol route. Exposure to 5 × 106 TCID50 and 5 × 104 TCID50 MERS-CoV per cage via fomites resulted in transmission in 15 out of 20 and 11 out of 18 animals, respectively. Exposure of sentinel mice to donor mice one day post inoculation with 105 TCID50 MERS-CoV resulted in transmission in 1 out of 38 mice via direct contact and 4 out of 54 mice via airborne contact. Exposure to donor mice inoculated with 104 TCID50 MERS-CoV resulted in transmission in 0 out of 20 pairs via direct contact and 0 out of 5 pairs via the airborne route. Our model shows limited transmission of MERS-CoV via the fomite, direct contact, and airborne routes. The hDPP4 mouse model will allow assessment of the ongoing evolution of MERS-CoV in the context of acquiring enhanced human-to-human transmission kinetics and will inform the development of other transmission models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the last two decades, three novel coronaviruses have caused outbreaks in the human population. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV-1) was first identified in 2003 after it caused human cases in the Guangdong province, China, in November 2002. From Guangdong, the virus spread to 37 countries, resulting in >8000 infected people with a case fatality rate of 9.5%1. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) was first detected in 2012 and still circulates in the dromedary camel population, from which it infects the human population. Since 2012, more than 2600 cases with a case fatality rate of 36%2 have been reported. The largest pandemic with a coronavirus to date started in December 2019 and was caused by SARS-CoV-2. To date, more than 770 million cases have been reported, resulting in nearly 7 million deaths3.

A better understanding of the transmission potential of coronavirus is crucial when devising personal protection equipment for healthcare staff and quarantine measurements. The stability of MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV-1, and SARS-CoV-2 has been investigated under several different environmental conditions in both fomites and aerosols4,5,6. Experimental transmission models have been developed for SARS-CoV-2 and focus mainly on hamsters and ferrets7,8,9,10,11,12,13, whereas SARS-CoV-1 transmission has been shown in ferrets and cats13,14. However, transmission of MERS-CoV in animal models has not yet been reported.

A review of 681 MERS cases in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) estimated that 12% of cases were infected via direct exposure to dromedary camels, and 88% resulted from human-to-human transmission15. Analysis of transmission dynamics showed that the number of subsequent generations is limited. The risk of a human-to-human transmission event differs per generation: the initial zoonotic transmission risk is 22.7%. Then it drops to 10.5% for the second generation, 6.1% for the third generation, and 3.9% for the fourth generation16. This shows that although human-to-human transmission contributes significantly to the number of human MERS-CoV cases, transmission is not sustained. Human-to-human transmission of MERS-CoV can be divided into household-associated healthcare-associated (nosocomial transmission). Epidemiological modeling of MERS-CoV transmission estimates nosocomial transmission to be ten times higher than household transmission17.

Virus transmission can occur via different routes, including fomites, direct contact, and aerosols. Knowledge on the transmission routes of emerging coronaviruses is essential in designing broad preemptive countermeasures against zoonotic and human-to-human transmission. More specifically, it will improve the ability of hospitals to reduce the likelihood of human-to-human transmission by implementing appropriate personal protective equipment and hospital hygiene procedures.

The best transmission models for SARS-CoV-2 are the hamster and ferret models7,8,9,10,11,12,13. However, these animals are not naturally susceptible to MERS-CoV18,19 and likely will require expression of hDPP4. Although transmission in mice is likely more limited than in hamsters or ferrets, SARS-CoV-2 transmission has been shown in mice20,21. Therefore, we utilize a transgenic mouse model expressing human DPP4 (hDPP4 mice) to investigate whether MERS-CoV can transmit via fomites, direct contact, or the airborne route.

Results

Intranasal or aerosol inoculation of hDPP4 mice with MERS-CoV

In our hDPP4 mouse model, expression of hDPP4 can be found in the nasal turbinates, trachea, lungs, and the kidney (Fig. 1a−d). Intranasal inoculation with 105 TCID50 MERS-CoV strain HCoV-EMC/2012 resulted in >20% weight loss and 100% lethality (Fig. 1e, f). Viral gRNA could be detected in oropharyngeal swabs on all six days during the experiment (Fig. 1g). Infectious virus was detected in lung tissue at three days post-inoculation (dpi) and at endpoint, as well as in brain tissue at end point, but not in the kidney (Fig. 1h). In contrast, littermates of the hDPP4 mice which were negative for hDPP4, were not susceptible to MERS-CoV infection. We then investigated whether inoculation via aerosols would result in productive infection of hDPP4 mice. We inoculated ten mice via aerosols with an estimated 3.8 × 102 TCID50 MERS-CoV per mouse. All mice reached the endpoint criteria (Fig. 2a). Shedding, as measured by gRNA presence in oropharyngeal swabs, could be detected on all days (Fig. 2b). Viral RNA was detected in lung tissue (four out of four) and brain tissue (one out of four) on three dpi and all tissue on the day of endpoint criteria (Fig. 2c). Using immunohistochemistry, we compared the cellular tropism of MERS-CoV replication in hDPP4 mice between intranasal (inoculation dose = 103 TCID50) and aerosol inoculation (3.8 × 102 TCID50) in the upper and lower respiratory tract at three dpi (Fig. 3). For both groups, viral replication was detected in lung tissue: type I and type II pneumocytes were positive for MERS-CoV antigen. However, even though we showed that cells lining the trachea, as well as the nasal turbinates, of hDPP4 mice express hDPP4 (Fig. 1a−c), MERS-CoV antigen staining was negative in the trachea. No staining in the nasal turbinates was detected for the aerosol-inoculated group, whereas staining in the nasal turbinates of the intranasally inoculated group was very limited (Fig. 3). This MERS-CoV respiratory tropism is similar to what has been observed in humans22; MERS-CoV predominantly targets the cells in the lower respiratory tract.

Detection of hDPP4 expression in hDPP4 mice using immunohistochemistry in (a) nasal mucosa; (b) trachea; and (c) type I and II pneumocytes, bronchiolar and endothelial cells in lung tissue. d Comparison of hDPP4 expression in lung and kidney tissue obtained from wildtype and hDPP4 mice using flow cytometry. N = 3, bars represent median. e Survival curves of mice after inoculation with 5 × 105 TCID50 MERS-CoV. N = 4 (Wildtype) or 5 (hDPP4). ** = p < 0.01. f Relative weight loss in mice after MERS-CoV inoculation. The lines represent median±range. Mice were euthanized upon reaching >20% of body weight loss (dotted line). g Viral load (gRNA) in oropharyngeal swabs obtained from mice after inoculation with 5 × 105 TCID50 MERS-CoV. h Infectious MERS-CoV titers in lung, brain, and kidney tissue of hDPP4 mice. Dotted line detection limit.

a Survival curves of mice inoculated with 3.8 × 102 TCID50 MERS-CoV via aerosols. N = 6. b Viral load (gRNA) in oropharyngeal swabs obtained from mice inoculated with 3.8 × 102 TCID50 MERS-CoV via aerosols. Bars represent median. b Viral load (gRNA) and c (infectious virus) in lung and brain tissue of hDPP4 mice inoculated with 3.8 × 102 TCID50 MERS-CoV via aerosols.

a, b Nasal turbinates; (c, d) Trachea; (e, f) Lungs; (a, c, e) Intranasal inoculation; (b, d, f) Aerosol inoculation. Tissues were stained with an in-house produced rabbit polyclonal antiserum against HCoV-EMC/2012 for the detection of viral antigen. Immunohistochemistry staining reveals MERS-CoV antigen in type I and type II pneumocytes and limited staining in nasal turbinates (image represents only staining found). Inserts highlight affected cells. Nasal turbinates (200x), trachea (200x) and lung tissue (100 and 400x insert) are shown.

Transmission of MERS-CoV in hDPP4 mice

Next, we investigated the transmission of MERS-CoV within our mouse model via three different routes: fomite, direct contact, and the airborne route.

Fomite transmission

MERS-CoV-containing media was pipetted on different objects in the cage, including on two plastic and two metal washers, after which two mice were introduced per cage (Fig. S1). Upon exposure to 5 × 104 TCID50/cage, 11 out of 18 mice reached endpoint criteria (Fig. 4a). Brain and lung tissue were harvested from non-survivors, and viral gRNA was detected in brain tissue of eleven mice and lung tissue of seven mice (Fig. 4b). sgRNA was detected in brain tissue of three mice, and lung tissue of one mouse (Fig. 4c). Infectious virus was recovered from brain tissue, but not lung tissue, of three mice (Fig. 4d). The remaining seven mice were euthanized at 28 dpe; six animals were seropositive for MERS-CoV S1 (Fig. 4e). We then exposed twenty mice to 5 × 106 TCID50/cage, again two mice per cage. Fifteen out of 20 mice were euthanized (Fig. 4a). Viral gRNA was detected in lung and brain tissue of all the non-survivors (Fig. 4b). Viral sgRNA was detected in brain tissue of all mice and lung tissue of six mice (Fig. 4c). Infectious virus was isolated from brain tissue, but not lung tissue, of eight mice (Fig. 4d). Four out of five surviving animals were found to be seropositive for MERS-CoV S1 protein (Fig. 4e).

hDPP4 mice were exposed to 5 × 104 TCID50 MERS-CoV (N = 18) or 5 × 106 TCID50 MERS-CoV (N = 20). a Survival curves of hDPP4 mice exposed to fomites containing MERS-CoV. Viral gRNA (b) or sgRNA (c) in lung and brain tissue of hDPP4 mice that reached endpoint criteria. d Infectious MERS-CoV detected in lung and brain tissue of hDPP4 mice that reached endpoint criteria. e Serology titers in sera of survivors obtained 28 dpe. ELISA assays were performed using MERS-CoV S1 protein. Dotted line = limit of detection. ** = p < 0.01.

Contact transmission

Twenty mice in two separate experiments were inoculated intranasally with 104 TCID50 MERS-CoV, and single-housed. One day later, one sentinel mouse per cage was introduced. No sentinel mice reached endpoint criteria (Fig. 5a). One mouse seroconverted with a titer of 100 (Fig. 5e). Subsequently, 38 mice in three separate experiments were inoculated with 105 TCID50 MERS-CoV, and sentinel mice were introduced one day later. One sentinel mouse was euthanized five days post-exposure (dpe) (Fig. 5a). A low amount of viral gRNA was detected in both lung and brain tissue (Fig. 5b), but no sgNA was detected (Fig. 5c). Likewise, no infectious virus was recovered from tissue (Fig. 5d). All 37 remaining sentinels survived exposure. Antibodies against S1 were detected in one surviving animal (Fig. 5e).

hDPP4 mice were inoculated intranasally with 104 TCID50 MERS-CoV (N = 20) or 105 TCID50 MERS-CoV (N = 38). a Survival curves of mice directly exposed to donor mice infected with MERS-CoV. Viral gRNA (b) or sgRNA (c) in lung and brain tissue of hDPP4 mice that reached endpoint criteria. d Infectious MERS-CoV detected in lung and brain tissue of hDPP4 mice that reached endpoint criteria. e Serology titers in sera of survivors obtained 28 dpe. ELISA assays were performed using MERS-CoV S1 protein. Dotted line = limit of detection.

Airborne transmission

Five hDPP4 mice were inoculated intranasally with 104 TCID50 MERS-CoV. Sentinel mice were introduced in the same cage as the donor animal at one dpi. Animals were separated by a perforated divider, which did not allow direct contact but allowed airflow from the donor to the sentinel animal (Fig. S1, also described in7). No animals reached endpoint criteria (Fig. 6a). Three surviving animals were found to be seropositive for S1 at very low titers (Fig. 6e). In eight different experiments, 54 hDPP4 mice were inoculated with 105 TCID50 MERS-CoV. Sentinel animals were introduced one dpi. Four animals reached endpoint criteria (Fig. 6a). Viral gRNA could be detected in all brain tissues and three out of four lung tissues (Fig. 6b). Viral sgRNA was detected in brain and lung tissue of two mice, and infectious virus was found in the brain, but not lung tissue, of one mouse (Fig. 6c, d). All 50 remaining sentinels survived exposure. Seven of the surviving animals were found to be seropositive for S1 (Fig. 5e).

hDPP4 mice were inoculated intranasally with 104 TCID50 MERS-CoV (N = 5) or 105 TCID50 MERS-CoV (N = 54). a Survival curves of mice exposed to donor mice infected with MERS-CoV. Viral gRNA (b) or sgRNA (c) in lung and brain tissue of hDPP4 mice that reached endpoint criteria. d Infectious MERS-CoV detected in lung and brain tissue of hDPP4 mice that reached endpoint criteria. e Serology titers in sera of survivors obtained 28 dpe. ELISA assays were performed using MERS-CoV S1 protein. Dotted line = limit of detection.

Discussion

The continued circulation of MERS-CoV in the dromedary camel population highlights the need for a better understanding of the transmission potential of MERS-CoV. Like MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2 are thought to use a combination of different transmission routes between humans, including fomite, direct contact, and airborne transmission. Which one of these routes is most important is difficult to ascertain. However, it is clear that human-to-human transmission of MERS-CoV is restricted compared to SARS-CoV-1 and, in particular, SARS-CoV-2, and is primarily nosocomial17.

Within hospitals, MERS-CoV viral RNA has been detected on various surfaces up to five days after viral RNA was detected in patient samples. In addition, infectious virus was isolated from different hospital surfaces23 and air samples24. Likewise, SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2 RNA could be detected in air and surface samples25,26. Experimentally, infectious MERS-CoV at 20 °C and 40% relative humidity could be recovered from plastic and steel surfaces for up to 48 h4, and using a similar setup, SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2 likewise retained viability for 48 h5. Superspreader events have been documented for all three viruses27,28,29, and in some scenarios, airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2 appears to be the most likely scenario for specific human-to-human transmission clusters27,30,31,32.

Animal models are crucial for experimental transmission studies, as transmission involves several factors: shedding of virus from an infected host, survival of the virus in aerosols or on surfaces, and infection of the sentinel host. Our data suggest that MERS-CoV can utilize a variety of different transmission routes, although the fomite route was much more efficient than both the direct contact and airborne routes.

In our airborne transmission setup the cage divider prevents direct contact, but allows the movement of larger droplets and aerosols from the donor cage to the sentinel cage. Therefore, we cannot distinguish between transmission events by aerosols (droplets < 100 µm), larger droplets (>100 µm), or a combination of these two33. An experimental setup exclusively allowing transmission of aerosols as designed for SARS-CoV-234 would be able to distinguish between aerosol and droplet transmission.

Our overall data agree with limited human-to-human transmission of MERS-CoV in the general population. Given the tropism of MERS-CoV for the lower respiratory tract and minimal evidence of infection of the upper respiratory tract22,35,36,37, there is likely little to no natural generation of infectious aerosols in patients. We hypothesize that the propensity of MERS-CoV to transmit relatively efficiently in hospital settings is linked to performing aerosol-generating procedures, such as intubation and bronchoscopy, on infected patients38,39,40 rather than the natural generation of aerosols containing MERS-CoV from the respiratory tract of the patient. Combined with a potentially more susceptible hospital population41, this could lead to a relatively high nosocomial transmission compared to household transmission.

In this study, we showed MERS-CoV transmission via the fomite and in limited numbers via direct contact and airborne routes. The hDPP4 transmission model will be invaluable in assessing the transmission potential of novel MERS-CoV strains without prior adaptation to the mouse host in light of the continuing virus evolution during human outbreaks and the camel population42,43. In addition, this work will allow the development of effective countermeasures to block human-to-human transmission of MERS-CoV.

Methods

Ethics statement

Approval of animal experiments was obtained from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Rocky Mountain Laboratories. Performance of experiments was done following the guidelines and basic principles in the United States Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Work with infectious MERS-CoV strains under BSL3 conditions was approved by the Institutional Biosafety Committee (IBC). Inactivation and removal of samples from high containment was performed per IBC-approved standard operating procedures.

Development of hDPP4 mice

hDPP4 mice were developed by ingenious Targeting Laboratory. A ROSA26 knock-in vector containing a 3’ splice acceptor, LoxP-flanked neomycin stop cassette, Kozak sequence, human DPP4 cDNA sequence and bovine growth hormone poly-A tail was injected into balb/c embryonic stem (ES) cells via electroporation. ES cells were injected into balb/c blastocysts. Resulting chimeric mice were bred with wildtype balb/c mice. Heterozygous offspring were bred with BALB/c-Tg(CMV-cre)1Cgn/J mice (Jackson Laboratory) to produce mice ubiquitously expressing hDPP4. Deletion of the LoxP-flanked neomycin stop cassette occurs in all tissues, including germ cells, in BALB/c-Tg(CMV-cre)1Cgn/J mice. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed to genotype each mouse using a three primer set-up; forward primer (FP) AGCACTTGCTCTCCCAAAGTC, reverse primer 1 (RP1) GACAACGCCCACACACCAGGTTAG and reverse primer 2 (RP2) TCTTCTGTAATCAGCTGCCTTTTA.

Virus and cells

HCoV-EMC/2012 was kindly provided by Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands. Virus propagation was performed in VeroE6 cells in DMEM (Sigma) supplemented with 2% fetal calf serum (Logan), 1 mM L-glutamine (Lonza), 50 U/ml penicillin and 50 μg/ml streptomycin (Gibco) (2% DMEM). VeroE6 cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 1 mM L glutamine, 50 U/ml penicillin and 50 μg/ml streptomycin. Virus was titrated by inoculating VeroE6 cells with tenfold serial dilutions of virus in 2% DMEM. Five days after inoculation, cytopathic effect (CPE) was scored and TCID50 was calculated from four replicates by the method of Spearman-Karber.

DPP4 expression

The expression of DPP4 in mouse tissue was examined using flow cytometry. Lung and kidney tissues were collected from animals and a single cell suspension was made using the mouse lung dissociation kit (Miltenyi Biotec). Cells were washed two times in PBS containing 2% FBS, and incubated with anti-DPP4 (AF1180, R&D systems, 8 µg/mL in PBS with 2% FBS). After 1 h at 4 °C, cells were washed as above and incubated with donkey anti-goat AF488 (A-11055, Thermo Fisher, 1:500 in PBS with 2% FBS). Hereafter, cells were washed, fixed with 2% formalin and analyzed on a BD FACSymphony A5 (BD Biosciences) flow cytometer using a high-throughput sampler. DPP4 expression was analyzed using FlowJo 8 (BD Biosciences).

Inoculation experiments

Animal numbers were determined using statistical methods before study start. hDPP4 mice (4−10 weeks, male and female) were separated by sex and then randomly divided between the experimental group, ensuring sex distribution was even. Animals were acclimatized for at least 3 days. Hereafter, animals were anesthetized with inhalation isoflurane and inoculated intranasally with MERS-CoV isolate HCoV-EMC/2012 in a total volume of 30 µl. Aerosol inoculation using the AeroMP aerosol management platform (Biaera technologies, USA) was performed as described previously18. Briefly, mice that were awake were exposed to a single 10-minute aerosol exposure whilst contained in a stainless-steel wire mesh cage (5 mice per cage, 2 cages per run, mo anesthesia). Aerosol particles were generated by a 3-jet collison nebulizer (Biaera technologies, USA) and ranged from 1 to 5 µm in size. Respiratory minute volume rates of the animals were determined using Alexander et al. 44. Weights of the animals were averaged and the estimate inhaled dose was calculated using the simplified formula D = R x Caero x Texp45, where D is the inhaled dose, R is the respiratory minute volume (L/min), Caero is the aerosol concentration (TCID50/L), and Texp is duration of the exposure (min). After inoculation, animals were observed daily for signs of disease. Euthanasia was indicated at >20% loss of initial body weight, if severe respiratory distress was observed, or if neurological signs were observed. Oropharyngeal and nasal swabs were collected daily in 1 ml DMEM with 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin. Researchers were not blinded to study groups.

Transmission experiments

All transmission studies were done at 21−23 °C and 40−45% relative humidity. Fomite transmission was examined by contaminating cages containing two metal and two plastic discs [3] with 0.5 mL of MERS-CoV isolate HCoV-EMC/2012 (total dose: 5 × 106 or 5 × 104 TCID50 per cage) in the following manner: 50 µl of virus was placed on the water bottle, 50 µl of virus was placed on the food, 50 µl of virus was placed per disc, and 4 × 50 µl of virus was placed on the flooring of the cage. Mice (4−10 weeks, male and female) were placed in the cages 10 min post contamination and followed as described above. Contact and airborne transmission were examined by intranasal inoculation of donors with 104 or 105 TCID50 of MERS-CoV. At 1 dpi, sentinel animals (4−10 weeks, male and female) were placed in the same cage (contact transmission) or in the same cage on the other side of a divider (airborne transmission) (Fig. S1). This divider prevented direct contact between the donor and sentinel mouse and the movement of bedding material. Only one transmission pair was housed per cage. Hereafter, mice were followed as described above.

Histopathology and immunohistochemistry

Murine tissues were evaluated for pathology and the presence of viral antigen as described previously46. Briefly, tissues were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin for 7 days and paraffin-embedded. Tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). An in-house produced rabbit polyclonal antiserum against HCoV-EMC/2012 (1:1000) was used as a primary antibody for the detection of viral antigen. A commercial antibody (AF1180, R&D resources) was used for the detection of DPP4.

Viral RNA detection

Tissues were homogenized in RLT buffer and RNA was extracted using the RNeasy method on the QIAxtractor (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was extracted from swab samples using the QiaAmp Viral RNA kit on the QIAxtractor. For one-step real-time qPCR, 5 μl RNA was used in the Rotor-GeneTM probe kit (Qiagen) according to instructions of the manufacturer. Standard dilutions of a virus stock with known titer were run in parallel in each run, to calculate TCID50 equivalents in the samples. Initial detection of viral RNA was targeted upstream of the envelope gene sequence (UpE)47, confirmation was targeted at the ORF1A48. MERS-CoV M-gene mRNA was detected as described by Coleman et al. 49. Values with Ct-values > 38 were excluded. For digital droplet PCR (ddPCR, Biorad), 8 µl RNA was added to supermix for probes and assay was run according to instructions of the manufacturer using UpE primers and probe allowing absolute quantification of target RNA.

Serology

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was performed as described previously50. Briefly, spike S1 antigen Sino Biological Inc., 0.5 µg/mL in 50 mM bicarb binding buffer (4.41 g KHCO3 and 0.75 g Na2CO3 in 1 L water) was bound to MaxiSorb plates (Nunc) and then blocked with 5% non-fat dried milk in PBS-0.1% Tween (5MPT). Serum samples were diluted in 5MPT. Detection of MERS-specific antibodies was performed with HRP-conjugated IgG (H + L) secondary antibody and developing solution (KPL) followed by measurement at 405 nm. Sera was termed seropositive if the optical density value was higher than the average + 3x standard deviation of sera obtained from randomly selected mice before MERS-CoV inoculation.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test to compare survival curves, and by Kruskall-Wallis test followed by Mann-Whitney test. P < 0.05 were considered significant.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in Figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24811923.

Change history

05 March 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44298-025-00094-0

References

WHO. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS). https://www.who.int/health-topics/severe-acute-respiratory-syndrome#tab=tab_1.

WHO. MERS situation update, September 2023. https://www.emro.who.int/health-topics/mers-cov/mers-outbreaks.html#:~:text=From%20April%202012%20till%20September,(CFR)%20of%2036%25.

WHO. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/.

van Doremalen, N., Bushmaker, T. & Munster, V. J. Stability of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) under different environmental conditions. Eurosurveillence 18, 20590 (2013).

van Doremalen, N. et al. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N Engl. J. Med. 382, 1564–1567 (2020).

van Doremalen, N. et al. Surface‒aerosol stability and pathogenicity of diverse middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus strains, 2012‒2018. Emerg Infect. Dis. 27, 3052–3062 (2021).

Port, J. R. et al. SARS-CoV-2 disease severity and transmission efficiency is increased for airborne but not fomite exposure in Syrian hamsters. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.28.424565 (2020).

Sia, S. F. et al. Pathogenesis and transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in golden hamsters. Nature 583, 834–838 (2020).

Chan, J. F.-W. et al. Surgical mask partition reduces the risk of noncontact transmission in a golden syrian hamster model for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Clin. Infect. Dis. 71, 2139–2149 (2020).

Kim, Y.-I. et al. Infection and rapid transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in Ferrets. Cell Host Microbe 27, 704–709.e2 (2020).

Schlottau, K. et al. SARS-CoV-2 in fruit bats, ferrets, pigs, and chickens: an experimental transmission study. Lancet Microbe 1, e218–e225 (2020).

Richard, M. et al. SARS-CoV-2 is transmitted via contact and via the air between ferrets. Nat. Commun. 11, 3496 (2020).

Kutter, J. S. et al. SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 are transmitted through the air between ferrets over more than one meter distance. Nat. Commun. 12, 1653 (2021).

Martina, B. E. E. et al. Virology: SARS virus infection of cats and ferrets. Nature 425, 915 (2003).

Cauchemez, S. et al. Unraveling the drivers of MERS-CoV transmission. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 9081–9086 (2016).

Nishiura, H., Miyamatsu, Y., Chowell, G. & Saitoh, M. Assessing the risk of observing multiple generations of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) cases given an imported case. Eurosurveillence 20, 21181 (2015).

Poletto, C., Boëlle, P.-Y. & Colizza, V. Risk of MERS importation and onward transmission: a systematic review and analysis of cases reported to WHO. BMC Infect. Dis. 16, 448 (2016).

de Wit, E. et al. The Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) does not replicate in Syrian hamsters. PLoS ONE 8, e69127 (2013).

Raj, V. S. et al. Adenosine deaminase acts as a natural antagonist for dipeptidyl peptidase 4-mediated entry of the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J. Virol. 88, 1834–1838 (2014).

Pan, T. et al. Infection of wild-type mice by SARS-CoV-2 B.1.351 variant indicates a possible novel cross-species transmission route. Sig. Transduct. Target Ther. 6, 1–12 (2021).

Bao, L. et al. Transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2 via Close contact and respiratory droplets among human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 mice. J. Infect. Dis. 222, 551–555 (2020).

Ng, D. L. et al. Clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural findings of a fatal case of middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection in the United Arab Emirates, April 2014. Am. J. Pathol. 186, 652–658 (2016).

Bin, S. Y. et al. Environmental contamination and viral shedding in MERS patients during MERS-CoV outbreak in South Korea. Clin. Infect. Dis. 62, 755–760 (2016).

Kim, S.-H. et al. Extensive viable Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) Coronavirus contamination in air and surrounding environment in MERS isolation wards. Clin. Infect. Dis. 63, 363–369 (2016).

Booth, T. F. et al. Detection of airborne severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus and environmental contamination in SARS outbreak units. J. Infect. Dis. 191, 1472–1477 (2005).

Tan, K. S. et al. Detection of hospital environmental contamination during SARS-CoV-2 Omicron predominance using a highly sensitive air sampling device. Front. Public Health 10, 1067575 (2022).

Cho, S. Y. et al. MERS-CoV outbreak following a single patient exposure in an emergency room in South Korea: an epidemiological outbreak study. Lancet 388, 994–1001 (2016).

Wang, S. X. et al. The SARS outbreak in a general hospital in Tianjin, China – the case of super-spreader. Epidemiol. Infect. 134, 786–791 (2006).

Majra, D., Benson, J., Pitts, J. & Stebbing, J. SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) superspreader events. J. Infect. 82, 36–40 (2021).

Yu, I. T. S. et al. Evidence of airborne transmission of the severe acute respiratory syndrome virus. N Engl J. Med. 350, 1731–1739 (2004).

Yu, I. T. S., Wong, T. W., Chiu, Y. L., Lee, N. & Li, Y. Temporal-spatial analysis of severe acute respiratory syndrome among hospital inpatients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 40, 1237–1243 (2005).

Duval, D. et al. Long distance airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2: rapid systematic review. BMJ 377, e068743 (2022).

Prather, K. A. et al. Airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Science 370, 303–304 (2020).

Port, J. R. et al. Increased small particle aerosol transmission of B.1.1.7 compared with SARS-CoV-2 lineage A in vivo. Nat. Microbiol. 7, 213–223 (2022).

Alsaad, K. O. et al. Histopathology of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronovirus (MERS-CoV) infection - clinicopathological and ultrastructural study. Histopathology 72, 516–524 (2018).

Memish, Z. A. et al. Respiratory tract samples, viral load, and genome fraction yield in patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome. J. Infect. Dis. 210, 1590–1594 (2014).

Guery, B. et al. Clinical features and viral diagnosis of two cases of infection with Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus: a report of nosocomial transmission. Lancet 381, 2265–2272 (2013).

Fowler, R. A. et al. Transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome during intubation and mechanical ventilation. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 169, 1198–1202 (2004).

Christian, M. D. et al. Possible SARS coronavirus transmission during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 10, 287–293 (2004).

Tran, K., Cimon, K., Severn, M., Pessoa-Silva, C. L. & Conly, J. Aerosol generating procedures and risk of transmission of acute respiratory infections to healthcare workers: a systematic review. PLoS ONE 7, e35797 (2012).

Judson, S. D. & Munster, V. J. Nosocomial transmission of emerging viruses via aerosol-generating medical procedures. Viruses 11, 940 (2019).

Kim, Y. et al. Spread of mutant middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus with reduced affinity to human CD26 during the South Korean Outbreak. mBio 7, e00019 (2016).

Sabir, J. S. M. et al. Co-circulation of three camel coronavirus species and recombination of MERS-CoVs in Saudi Arabia. Science 351, 81–84 (2016).

Alexander, D. J. et al. Association of Inhalation Toxicologists (AIT) working party recommendation for standard delivered dose calculation and expression in non-clinical aerosol inhalation toxicology studies with pharmaceuticals. Inhal. Toxicol. 20, 1179–1189 (2008).

Hartings, J. M. & Roy, C. J. The automated bioaerosol exposure system: preclinical platform development and a respiratory dosimetry application with nonhuman primates. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 49, 39–55 (2004).

de Wit, E. et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) causes transient lower respiratory tract infection in rhesus macaques. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 16598–16603 (2013).

Corman, V. M. et al. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR. Eurosurveillance 25, 2000045 (2020).

Corman, V. M. et al. Assays for laboratory confirmation of novel human coronavirus (hCoV-EMC) infections. Eurosurveillence 17, 20334 (2012).

Coleman, C. M. & Frieman, M. B. Growth and Quantification of MERS-CoV Infection. Curr. Protoc. Microbiol. 37, 15E.2.1–9 (2015).

van Doremalen, N. et al. High prevalence of Middle East respiratory coronavirus in young dromedary camels in Jordan. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 17, 155–159 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Laura Tally and colleagues for assistance with mouse breeding, the Rocky Mountain Veterinary branch for assistance with high containment husbandry and cage design, Tina Thomas, Dan Long and Rebecca Rosenke for assistance with pathology and Anita Mora and Ryan Kissinger for assistance with the figures. This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Funding

Open access funding provided by the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.v.D. and V.J.M. wrote the main manuscript text. N.v.D., R.F., T.B., A.O., R.M., M.L., D.S., G.S., D.F.A., and V.J.M. performed the research. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

van Doremalen, N., Bushmaker, T., Fischer, R.J. et al. Transmission dynamics of MERS-CoV in a transgenic human DPP4 mouse model. npj Viruses 2, 36 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44298-024-00048-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44298-024-00048-y