Abstract

Nanoplasmonic optical antennas function as sensors and actuators, facilitating rapid and selective on-site molecular diagnostics for personalized precision medicine. Here, we highlight advancements in plasmonic biosensors and actuators within point-of-care diagnostics platforms, including optical trapping, cell lysis and ultrafast photonic polymerase chain reaction. Furthermore, we discuss nanoplasmonic optical sensing technologies, and commercial optical diagnostic systems. Nanoplasmonic optical antennas are essential to photonic sample-to-answer systems, significantly enhancing advancing preventive, personalized, and precision medicine.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The emergence of infectious diseases like COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2), monkeypox, and avian influenza has threatened public health and global economies, with particularly severe impacts on low-income countries1,2,3. Significant advancements in infectious disease research and therapeutic development have been made to overcome these challenges, focusing on biosecurity, predictive and preventive medicine, and personalized healthcare. Among numerous technologies devoted to rapidly monitoring infectious diseases, plasmonic biosensors are a powerful tool because of their great specificity and sensitivity in sample collection and recognition. Plasmonic nanostructures or nanoplasmonic optical antennas (NOAS), typically made of metals, have the unique property to concentrate and couple with light for its oscillation and resonance of electrons on their surface4,5 at highly localized hotspots. These hot spots in nanostructures generate a photothermal effect, benefiting the localized photothermal lysis of pathogens, exosomes, or cells, and enhancing nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) through photonic/plasmonic polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or isothermal methods6 such as loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP), rolling circle amplification (RCA), and recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA)7,8,9. NOAS also enable quantitative detection of molecules through their fingerprints by enhancing their vibrational and electronic excitations near its surface. Molecular fingerprints can be identified without labels using surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS)10, plasmon resonance energy transfer (PRET), quantum biological electron tunneling (QBET)11,12, reverse PRET13, or the naked eyes (colorimetric detection)14.

NOAS can be optimized to explore cellular environments15 and monitor molecular dynamics5. Size, shape, and composition of nanoparticles can be designed with specific localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) wavelengths from the ultraviolet–visible (UV–vis) to the infrared (IR) region16. Various shapes offer different optical properties, including nanospheres17, nanorods18, nanoshells19, nanocages20, nanocrescents21, and nanostars22 (Box 1). Structures with sharp edges, like nanocrescents23,24 and magnetic nanocrescents25 with high electromagnetic field enhancement factors and near-IR (NIR) absorption, serve as alternatives for SERS substrates, and deeper penetration and reducing photothermal damage in biomedical imaging. Anisotropic nanostructures like nanorods, nanoshells, and nanocages with near-infrared LSPR are especially useful for photothermal therapy due to reduced light attenuation in biological tissues26,27,28,29,30,31.

Plasmonic detection platforms offer stable solutions for identifying biological components at low concentrations or at the single-molecule level, which makes them ideal for early diagnosis and patient monitoring32. A thorough understanding of the physical chemistry of nanomaterials is crucial for designing molecular diagnostic systems that achieve ultra-fast detection, especially in infectious disease diagnostics, where quicker results can lower both time and costs in clinical environments.

This review highlights recent developments in plasmonic biosensors and actuators, designed to create advanced integrated molecular diagnostic systems that enable sample preparation and detection on a single chip. We investigate the principles of plasmonic trapping, the enrichment of biomarkers, and the design plasmonic nanostructures to improve photothermal lysis efficiency in biological samples. Furthermore, we address how these nanostructures contribute to ultrafast photothermal cycles in PCR for nucleic acid amplification. Finally, we examine label-free plasmonic biosensors and their potential applications for future ultrasensitive molecular diagnostics aimed at early diagnosis in preventive and precision medicine.

Biosensing workflow from sample-to-answer diagnosis

Biological samples such as blood, saliva, nasal swabs, or urine provide biomarkers for disease-related endogenous genes and infectious microorganisms at the molecular diagnostic level. In general, a comprehensive biosensing workflow for sample-to-answer diagnosis involves transforming biological samples into either qualitative or quantitative diagnostic results. This process incorporates several steps: (1) sample collection, (2) enrichment and purification, (3) lysis, (4) target amplification, (5) signal detection, and (6) data transmission. However, current chemical or mechanical sample preparation techniques are often time-consuming, non-selective, and damaging to delicate samples, which limit the purification yield of target molecules. Moreover, traditional biosensing methods, including NAATs, generally require large instruments and multiple sample preparation steps, and they exhibit a lower signal-to-noise ratio when dealing with complex clinical biological samples.

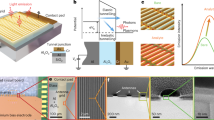

Conversely, plasmonic biosensing and actuation techniques are particularly suitable for miniaturized integrated platforms tailored for point-of-care (POC) diagnostics (Fig. 1). These methods can selectively enrich target molecules, execute one-step localized plasmonic photothermal lysis, enable efficient and ultrafast photothermal heat cycling for the amplification of nucleic acids, or incorporate optical detection combined with artificial intelligence (AI) analysis. They offer improved signal amplification and processing speed, positioning them as an alternative to traditional methods in various applications.

In molecular diagnosis, biological samples such as blood, saliva, nasal swabs, or urine serve as biomarker sources for disease-related endogenous genes and infectious microorganisms. Nanoplasmonic optical antennas play a role in many biosensing applications, including sample collection, enrichment and purification, lysis, target amplification, and signal detection.

Plasmonic actuators for trapping and enriching nucleic acids, proteins, exosomes, cells, and pathogens

A refined method known as plasmonic optical tweezers allows capturing biomolecules such as nucleic acids, exosomes, cells and pathogens in low concentrations, greatly minimizing the requirement for extensive sample preparation equipment and chemicals. The optical forces involved in these trapping platforms arise from interactions between light and matter, mainly influenced by the scattering and gradient forces of the electromagnetic field33,34,35,36,37,38,39 (Box 2).

The plasmonic effect of nanostructures40 can improve optical trapping, significantly reducing the necessary optical power. Therefore, combining nanoplasmonic structures and optical tweezers can improve the force scale and potential well depth41 for efficient optical enrichment of biological samples (Box 2c). Plasmonic nanostructures can be engineered to efficiently propagate light and concentrate it into a hotspot36 (Box 2d). When a dielectric particle is located at position (r) near the plasmonic nanostructure surface, the intensified optical near-field promotes trapping near the gold pads. Simultaneously, the lateral scattering forces induced by the coupling of evanescent waves drag the particle along the surface42:

The particle size affects the resulting electromagnetic field distribution, creating an optical potential landscape Ugrad(R) which can impact the particle motion. This potential energy Ugrad(R) originates the gradient (or polarization) force, 〈Fgrad(t)〉:

in which \(P\left(r,{\omega }_{0}\right)=\frac{\epsilon \left({\omega }_{0}\right)-1}{4\pi }\varepsilon (r,{\omega }_{0})\) is the vector electric polarization, which correlates to the dielectric constant ϵ(ω0) of the material, the local electric field E(r, t) and magnetic field H(r, t) created by the incident light. Then, a standard gradient relation expressed as:

where the potential Ugrad(R) defined from the optical index nbead of the particle material and the electric near-field intensity |E(r,ω0)|2, is given by:

This potential depth can be actively tuned by altering the illumination wavelength λ0 = 2πc/ω0 or the incident angle θ. A near-field plasmon resonance and thus the trapping potential can be significant amplified by the increasing the integral \({\int }_{v}dv{|{E}(r,{\omega }_{0})|}^{2}\).

Two main strategies that can amplify optical forces on nanoparticles are using surface plasmons generated by manipulating metal nanoparticles to increase their mechanical response to the surrounding optical fields43,44 or to create intensified fields45. The magnitude of light transmission is highly influenced by excitation light’s wavelength and polarization, as well as the nanostructure’s geometry and surrounding dielectric environment46. Typically, metallic structures are patterned on dielectric substrates containing target molecules in biological fluid samples. Among various geometries, plasmonic dimers, consisting of two identical metal nanoparticles separated by a nanogap, exhibit properties that concentrate propagating light beyond its diffraction limit47,48,49,50. When the propagating light and the particles are linearly polarized, it results in tight confinement and an intense light spot within the gap area51 (Fig. 2a). During light exposure, plasmonic nanostructures undergo Joule heating due to the strong absorption in metals. The heating creates a temperature gradient at the interface between the nanostructure and its surrounding area, which depends on the power and time of irradiation. In fact, in nano-optical trapping, the temperature in a nanohole can increase by 10 °C by the illumination of moderate light intensity (2 mW/μm2)52 or illumination on a gold film at an intensity of 6.67 mW/μm2 (at λ0 = 1064 nm)53. The thermal effect can consequently disturb the stable trapping by speeding up diffusion and changing biological conformation54 due to thermophoresis, convection, and thermos-osmosis55. The single nanohole structure exhibits a self-induced back action (SIBA) effect, in which the trapped object reinforces the restoring force within the trap56. The double nanoholes also dramatically enhanced field gradients at the inner-aperture junction to further create a sharper trapping potential46,57,58 (Fig. 2b). Moreover, Crozier’s group demonstrated a nano-optical tweezer based on all-silicon nanoantennas without deleterious thermal effect59. To achieve high-speed trapping and low concentration without perturbation of thermophoresis forces, electrothermoplasmonic (ETP) effects, a combination of plasmonic heating with an a.c./d.c. (alternating current/direct current) electric field, induces the capturing and forcing of suspended particles to the trapping area on the timescale of a second. The a.c. field is then switched to a d.c. field or a low-frequency a.c. field <10 Hz to permanently lock the particles in the hotspot even when light illumination and d.c. field turning off60. By alter laminar flows in microfluidics, the ETP can be implemented in LSPR assay to accelerate the trapping of IgG to the sensor surface, resulting in improved sensitivity and faster detection time61 (Fig. 2d). However, when the plasmonic heating is dissipated by high thermal conductivity substrate, the photothermal hotspot is eliminated, preventing ETP flow induced particle transportation62.

a Reversible trapping of lambda DNA on a metallic nanostructure by switching femtosecond-pulsed NIR laser irradiation on and off. Reprinted with permission from ref. 51. Copyright 2013 American Chemical Society. b The nanogap of a gold bowtie can create intense optical hot spots that trap DNA translocation through its nanopore, offering physical control over the speed of DNA movement. Reprinted with permission from ref. 54. Copyright 2015 American Chemical Society. c Plasmonic bacteria are forced to align on the nanopore. Reprinted with permission from ref. 285. Copyright 2018 Springer Nature. d An electrothermoplasmonic effect-based LSPR microfluidic sensing chip can overcome optoelectrical convection flow, demonstrated through high fluid velocities and improved immunoglobulin G detection performance. Reprinted with permission from ref. 61. Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society. e Thermophoretic force is created when photothermal heating around gold nanorods under resonant laser irradiation (785 nm) drives convection flow, enabling the localized plasmonic gold nanorods assembly with micro-sized bacteria without requiring specific linkers or templates. Reprinted with permission from ref. 70. Copyright 2022 Wiley-VCH GmbH. f Nanocavities of geometry-induced electrohydrodynamic tweezers (GET) allow a.c. electro-osmotic flow at the center of the void region where individual EVs are to be trapped, enabling plasmon-enhanced optical trapping under laser illumination without causing harmful heating effects. Reprinted with permission from ref. 62. Copyright 2023 Spinger Nature.

Moreover, optical traps are typically constrained to small sample volumes. For low concentrations of biomolecules, exosomes, or pathogens, it may not ensure reliable trapping and detection. Whang et al. integrated a nanoporous mirror with hydrodynamic trapping to enhance bacterial enrichment on the nanopores of a plasmonic optical array (Fig. 2c). Strong near-field enhancement occurs due to focused light from interference and diffraction at the nanopore, nanoplasmonic particles attached and assembly on the bacterial surface, and interactions of a plasmonic mirror surrounding the nanopore. The diffraction of the incident light within the nanopore on gold film causes constructive interference that can amplify the electric field between gold nanoparticles and a gold film35,47,63. When a particle tries to escape, a reduction in light momentum (ΔT) generates a force (F) that draws the particle back into the nanopore64. Opto-hydrodynamic trapping, the combination of opto-hydrodynamic effect and optical trapping, is used for trapping different nanosized bio-samples such as viruses, mycoplasmas, and pathogenic bacteria65. Moreover, photothermal actuation of Marangoni flow allows microswarm robots to perform collective migration, self-organization and group rejection66. This microswarm technology has been applied to optothermal, damage-free gene delivery in biomedical applications67. Additionally, Xin’s group introduced an opto-thermal-hydrodynamic approach for precise manipulation and flexible patterning of large-scale particle assemblies (up to 2000 particles) with a variety of shapes and sizes (0.5–20 µm)68, as well as direct 4D patterning with single-particle resolution69.

Although convection flow comes with the disadvantages of photothermal heating, photothermal-induced convection flow can be utilized to enhance the assembly of various colloids with different gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria (E. coli, B. subtilis, B. cereus, and M. luteus) for strengthening the SERS signal without the need of specific linker or templates70 (Fig. 2e). The motions of colloids depend on sizes and densities under same velocities. Drag force pulls the small sub-100 nm molecules follow the convection flow by their density. As the size of the molecule increased, gravity and the buoyancy forces became more significant. Yet, when the molecule density was approximately equal to that of water, drag force dominated and controlled the transport. However, this method is still suffering from particle aggregation so that it is not sufficient to use for single particle trapping and fingerprint detection of a single biomolecule. Geometry-induced electrohydrodynamic tweezers (GET) are introduced as an ideal for massive single nanosized particles within seconds without detrimental heating at the hotspot (Fig. 2f). The GET platform uses a scalable circular array of plasmonic nanoholes with a central void to generate electrohydrodynamic potentials that trap single nanosized particles at the void center, while also enhancing fluorescence emission through surface plasmon waves62. The plasmonic photothermal forces enable applications such as particle separation71,72,73,74, cell/colloid manipulation75, extracellular vesicle (EV) analysis76, DNA size manipulation77, blood sorting78, and bacteria separation79.

Plasmonic optical trapping or plasmonic nanotweezers can become an alternative method for enrichment of biomolecules since they have the ability to overcome the diffraction limit for trapping and detection of biomolecules with low laser powers as well as chip device integration. Its application remains limited application from lab-to-industry due to complex fabrication methods, small trapping range and thermal effects although there are many efforts to overcome its limitations, including increasing inverse design, accurate trapping potential and perturbation, simplified instrumentation80.

Enhanced lysis efficiency by nano-plasmonic structures

Photothermal heating does not necessarily have to be destructive when it facilitates a hotspot area. If the temperature surpasses the trapped particles, it can reshape the melt molecules into various forms depending on the power and illumination time. Biological membranes of exosomes, cells, or pathogens are highly vulnerable to heat, particularly within the range of 60–100 °C, which disrupts their structural integrity and functionality81,82,83,84. Therefore, the activation of nanoplasmonic photothermal lysis with localized heating up to 300 °C can effectively disrupt cellular membranes85. Moreover, metal nanoparticles are promising alternatives for antibacterial purposes due to their ability to produce reactive oxygen species (ROS) (⋅OH, ⋅O2−, and 1O2), release cations, damage biomolecules, deplete ATP, and interact with bacterial membranes86,87 (Box 3). As nanoparticle size decreases, their specific surface area increases, enhancing their interaction with the surrounding environment88,89. Bacterial cells interacting with polyvalent gold nanoparticles can lead to cell damage through two main pathways: (1) direct contact and (2) light-induced photothermal effect (Fig. 3a). A simple setup using LED illumination (excitation wavelength and exposure time) through focused beams that match the optical absorption of nanoparticles or nanostructures90 can be coupled with LSPR91,92,93 for localized photothermal heating. The stability of local heating can be achieved by controlling metallic nanostructures with less energy consumption94. Additionally, enhanced heating efficiency can be further achieved by controlling the geometry of nanoparticles (such as size, shape, and wavelength) and adjusting optical absorption at desired wavelengths95,96,97 or by using a concise channel in a microfluidic chip to obtain efficient optical absorption. For instance, Fig. 3b shows gold nanoparticles embedded in the modified herringbone structure of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) microfluidic chips for bacteria trapping and DNA extraction. Bacteria captured were irradiated with a 532 nm laser for 10 minutes to complete the DNA extraction for the PCR process98. Using the same 532 nm laser in the lysis chamber containing magnetic particles, a 15 min irradiation can extract DNA from the foodborne pathogens99. Spherical gold nanoparticles were irradiated by white light laser beams to disrupt microbial membranes at 100 °C within 2 min98. Moreover, the excitation by blue LED (447.5 nm) on gold-coated polycarbonate membranes quickly disrupts the membrane proteins of E. coli at a temperature of 90 °C within 1 min, making them useful for point-of-care urinalysis (Fig. 3c). NIR lasers were used to irradiate high-aspect-ratio gold nanorods to achieve efficient localized photothermal bacterial lysing within 30 s100. Moreover, the highly efficient photothermal cell lysis chip (HEPCL chip) composed of PDMS chips and plasmonic gold nanoislands enables broad-spectrum absorption and can evenly distribute temperature across the chamber, reaching the optimal temperature for cell lysis within 30 s (Fig. 3e). The heating efficiency of gold nanoislands can trigger lipid membrane photoporation and successfully lyses 93% of PC9 cells at 90 °C while minimizing DNA denaturation7. Compared to continuous light, LED-pulsed plasmonic photothermal can extract enzymes and enhance the capability of detecting antimicrobial resistance enzymes like β-lactamase101. Using on-chip LED-pulsed plasmonic photothermal lysis achieves cell lysis without protein denaturation (Fig. 3f). However, photothermal heating can cause non-specific lysis of cells, mitochondria, bacteria, and vesicles, which may create unwanted background interference. This interference complicates downstream analysis and differentiates between target and non-target molecules in complex biological samples such as bodily fluids (e.g., blood, saliva, and urine) or tissue extracts. Moreover, photothermal heating can lead to uneven temperature distributions between the hotspot and surrounding areas, resulting in either partial lysis or complete breakdown of cellular components. To address this issue, it is essential to optimize optical power precisely to promote efficient lysis while minimizing excessive non-uniform heating. An appropriate sample pretreatment or purification step may also be necessary before photothermal lysis of cells and cellular components to ensure controlled and selective processing.

a Schematic diagram illustrating the mechanism of cell disruption by the oxidative mechanism through two main pathways: (1) direct contact and (2) light-induced photothermal effect. Reprinted with permission from ref. 286. Copyright 2019 Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim. b Gold nanoparticles embedded in conjunction with a modified herringbone-structured GASI microfluidic chip to capture, enrich, and extract their DNA via a 532 nm laser with a power of 300 mW for 10 irradiations. Reprinted with permission from ref. 98. Copyright 2017 Elsevier B.V. c Gold-coated nanoporous membrane enables 40,000-fold bacterial enrichment from a 1 mL sample in 2 min and photothermal lysis of bacteria within 1 min through ultrafast light-to-heat conversion. Reprinted with permission from ref. 8. Copyright 2019 American Chemical Society. d Multi-principal element nanoparticles (FeNiCu) show the release of metal ions (Cu, Ni, and Fe cations) with different binding affinity to bacterial cell membrane protein functional groups, leading to the disruption of bacterial walls. The release of ions decreased from copper to nickel and then to iron. Reprinted with permission from ref. 102. Copyright 2023 American Chemical Society. e Strongly absorbed plasmonic gold nanoislands (SAP-AuNIs) generate uniform photothermal heating, achieving rapid cell lysing 93% of PC9 cells at 90 °C in 90 s without nucleic acid degradation. Reprinted with permission from ref. 7. Copyright 2023 American Chemical Society. f A rapid antimicrobial-resistance point-of-care identification device (RAPIDx) can extract contamination-free active target enzyme by photothermal lysis of bacterial cells on a nanoplasmonic functional layer on-chip without destroying the enzymatic activity by pulsed LED. Reprinted with permission from ref. 101. Copyright 2024 Wiley-VCH GmbH.

The multiple-element nanoparticles made of iron–nickel–copper (FeNiCu) selectively promote the release of ions to E. coli cell membrane protein groups, depending on metal binding affinity to membrane proteins. Specifically, copper ions were released significantly more than nickel, while iron showed the least release102. This highlights the potential of multi-principal element nanoparticles for controlled metal ion release in antibacterial applications (Fig. 3d). Recent focus has shifted toward leveraging the synergy between metals’ surface plasmon resonance and semiconductors, broadening LSPR and enabling the excitation of adjacent semiconductors103,104. By semiconductor supports, hot electrons generated from plasmonic metals are transferred to semiconductors under incident light and extending the lifetime of these hot carriers105. For example, an interfacial bismuth sulfide/titanium carbide MXene (Bi2S3/Ti3C2Tx) Schottky junction showed intense photocatalytic activity under near-infrared radiation by facilitating charge transfer, thereby increasing electron density, and consequently generating reactive oxygen species, then enhancing bacteria membrane permeability106. The antibacterial efficiency was up to 99.86% against S. aureus and 99.92% against E. coli within 10 min; moreover, plasmon excitation of gold nanorods distributed on titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanosheets can induce light-driven production of hot electrons and ROS for broad-spectrum photocatalytic activity107. However, the substantial ROS can disrupt biomolecules and organelle structures, leading to DNA/RNA damage108,109. Therefore, precise control of nanoparticle design and light irradiation is necessary to maintain the cellular components for further diagnosis. Oxidative reactions from plasmonic lysis can produce unwanted byproducts like lipid peroxidation and protein oxidation. These reactions may also cause structural changes, jeopardizing biomolecular integrity, leading to false-negative results in follow-up analyses. In addition, biological systems contain inherent antioxidants and reducing agents that can neutralize ROS or aid in molecular repair, which can markedly reduce overall lysis efficiency. Like photothermal heating, ROS-mediated plasmonic lysis can cause non-specific cell damage and inconsistent efficiency, necessitating thorough optimization and purification to achieve selective and reproducible results.

Nano-plasmonic structures enhanced nucleic acid amplification

Photothermal heating involves four primary steps, occurring within a timescale of ~100 ps110,111,112,113. First, when a photon from an incident light reaches and is absorbed by the metal nanostructures, a generation of electron-hole pair is generated, exciting electrons and holes and driving them out of equilibrium. Next, these exciting, high-energy carriers undergo thermalization by the relaxation of energy through electron-electron scattering. Then, these electrons dissipate their thermal energy into the lattice by electron–phonon interaction. Finally, this lattice energy dissipates into the surrounding environment114,115,116,117 (external thermalization) (Fig. 4a). Electron thermalization occurs extremely quickly in bulk metals (500 fs for gold and 350 fs for silver)115,118, making plasmonic photon-to-heat conversion adequate for use in NAAT application. In a subsequent study, mixing gold nanoparticles into bulk solution119,120 improved PCR sensitivity121 and reduced reaction time to 10 min122 (Fig. 4b). In 2017, a remarkable achievement of 30 thermal cycles in just 54 s was accomplished by incorporating plasmonic gold nanorods (aspect ratio 4.1) using an 808 nm NIR laser (2 W) to photogenerated heating123. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Cheong et al., by integrating magneto-plasmonic nanoparticles having a diameter of 16 nm illuminated by an 80-mW laser diode wavelength of 532 nm with a portable device, could detect SARS-CoV-2 RNA in 17 min124. Integrating ultrafast photonic PCR with microfluidic platforms for point-of-care devices has involved extensive research on thin metal films125 to accelerate amplification by minimizing sample volume and improving heat transfer rates. Son et al. used a thin gold film (65% absorption, 120 nm thick) as a photothermal heater for achieving 30 cycles within 5 min (Fig. 4c). Then, two gold films form optical mirrors to increase the photothermal heating efficiency and increase the sensitivity up to 2 DNA copies (cp)/μL126. Plasmonic pillar arrays, which absorb the light at the whole visible range, can induce the photogenerated heating for photonic PCR127,128 (Fig. 4d). Photonic PCR is an effective solution for nucleic acid amplification, reducing amplification time, improving accuracy, and lowering costs through integrated plasmonics-based optofluidics and a low-cost complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) sensor. Controlling photothermal heating requires careful material selection, choice of light source, and integration with microfluidic chips (Table 1). However, current university-level demonstrations are underdeveloped and often perceived as expensive systems, primarily due to limited experience with integrated circuits and photonics within existing educational frameworks. As a result, students and postdoctoral researchers lack opportunity to gain experience comparable to that of professional device engineers in the industry. Skilled engineers can mass-produce integrated optofluidics and CMOS sensors, creating low-cost POC devices suitable for both developed and low-resource settings.

a Electron–phonon coupling leads to lattice heating. This coupling causes energy transfer. b Schematic illustration of nucleic acid amplification in bulk solution when switching the LED on and off. c Schematic illustration of nucleic acid amplification in a nanofilm. d Schematic illustration of nucleic acid amplification in nanopillar structure. e Schematic illustration of plasmon-enhanced colorimetric detection in isothermal amplification. f Schematic illustration of nucleic acid amplification in a metasurface near-perfect absorber.

A plasmonic colorimetric sensing strategy was developed as a simpler approach for rapid integration with a photonic PCR-based POC device. For example, Jiang et al. introduced a direct detection plasmonic PCR method by combining magnetic nanoparticles and gold nanoparticle-based cross-linking colorimetry, achieving the limit of detection (LOD) of 5 copies/μL within 40 min129. Additionally, AbdElFatah et al. developed a microfluidic cartridge for plasmonic LAMP and RCA with colorimetric detection (Fig. 4e)14. In this system, hot electrons are generated from the self-assembled plasmonic nanoparticles (400 nm), accelerating nucleophilic reactions during the amplification process. As a result, protons were significantly produced, leading to a rapid decrease in pH, causing a color transition from fuchsia to yellow. Moreover, to enhance the sensitivity of colorimetric signals, they combined them with machine-learning algorithms to analyze the readout. This algorithm is designed to interpret the color changes quantitatively, determining whether the results are positive or negative for the target nucleic acids14. This method can amplify nucleic acids within 10 min, making it suitable for POC testing. As an alternative to thermal cycling-based PCR, isothermal amplification methods with a wide range of temperatures can be performed using an inexpensive and simple heating device. However, they still achieve the detection of single RNA copies per reaction. Despite their technological advancements in nucleic acid detection, these methods are limited in protocol standardization and still suffer from inconsistency130, false positive results131, complicated multiple primer sets132, low amplification efficiency, and non-specific amplification133. Therefore, aside from LAMP, other isothermal amplification methods have experienced delayed US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval as primary diagnostic tools, while PCR remains the gold standard for NAATs.

One of the major limitations in enhancing light-to-heat conversion efficiency in photonic PCR devices is the light absorption of nanostructures134. Therefore, optimizing photothermal heating mainly focuses on tuning their plasmonic properties for enhancing light absorption and increasing electron–phonon coupling. A near-perfect absorber for an ultrafast metaphotonic PCR chip was recently introduced by Kim et al. as illustrated in Fig. 4f. A large-area titanium nitride (TiN)-based broadband meta-absorber on a 6-in. wafer can enable ultrafast DNA amplification within 6 min and 30 s using a compact single IR LED source operating at 940 nm with a power of 3.8 W. TiN offers significant advantages for photothermal heating over conventional plasmonic materials by increasing electron-electron scattering rise time (~115 fs) compared to gold (~1 ps), enabling quicker electron excitation. Moreover, TiN exhibits a 25–100 times stronger electron-phonon coupling than gold, resulting in a shorter thermalization time (0.15 ps versus 5–10 ps for gold) and a greatly enhanced photothermal effect135. Enhanced light absorption in nanostructures has led to the development of commercial photonic PCR systems now available on the market.

Plasmonic structures enhance optical detection for molecular diagnosis

For accurate molecular profiling, optical plasmonic antennas identify target molecules through their unique vibration and electronic excitations. By coupling optical antennas with target biomolecules, real-time and quantitative detection can be achieved through the corresponding spectra (Box 4).

Surface plasmon resonance

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) is an optical sensing technique based on the excitation of surface plasmon polaritons, electromagnetic waves that propagate along a metal-dielectric interface. SPR is used to measure the changes in the refractive index near the metal surface, typically at interfaces with media such as liquid or air136 (Fig. 5a). In SPR-based molecular detection, the sensing surface was immobilized with specific bioreceptors such as antibodies, DNA probes or ligands, which selectively bind to the target molecules. When the target molecules bind to immobilized bioreceptors, this leads to a change in refractive index, then causing spectra or angular shift137,138. SPR is known as a label-free method, which allows binding kinetics measurement and offers high sensitivity down to pg/μL139. Commercial SPR-based sensors are being developed for real-time monitoring of viruses140,141, proteins142, DNA143, exosomes144. SPR is considered a surface-sensitive technique; however, its primary limitations stem from surface interactions. One significant drawback is the non-specific signal response, which arises from the broad region of the evanescent field (~100 nm)145, whereas typical protein analyte sizes range only from 2 to 10 nm146. This discrepancy can result in non-specific signals from unintended contributions of molecules in the surrounding medium rather than actual surface-bound interactions. Additionally, shifts in the bulk refractive index in complex biological samples can induce a bulk response, leading to false-positive or misleading signals. Addressing this issue has driven considerable research efforts, including modulating the total internal reflection (TIR) angle to optimize surface interactions and utilizing polymer brushes under physiological conditions147. Developing robust strategies to eliminate bulk response remains essential for enhancing the specificity and accuracy of SPR-based biosensing.

a Schematic illustration of the surface plasmon resonance (SPR). SPR uses light-excited surface plasmon polaritons (SPPs) to detect the binding of ligands to receptors immobilized on a metallic thin film surface. b Schematic illustration of the localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR). LSPR refers to the collective oscillation of conduction electrons near the surface of metallic nanostructures when exposed to light, generating a localized electromagnetic field with unique optical properties. c Schematic illustration of surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS). The detected Raman shift is correlated to the excited vibration of the molecule, occurring during the inelastic scattering of photons (Stokes or anti-Stokes). d Schematic illustration of plasmon-enhanced fluorescence (PEF). The plasmonic nanoparticles enhance the local electromagnetic field, increasing the excitation rate and the radiative decay rate of the fluorophore nearby. e Schematic illustration of plasmonic dimer. Plasmonic coupling can enhance 104 stronger intensities than that of fluorophore molecules. f Schematic illustration of plasmon resonance energy transfer (PRET). Energy is transferred from plasmonic optical antennas to the molecule showing the quantized quenching dips at the absorption peaks of the molecule on the scattering spectrum of the nanoplasmonic optical antennas. g Schematic illustration of plasmonic resonance energy transfer-based metal ion sensing (PRET-MIS). Metal ions can be identified explicitly by conjugated metal–ligand complexes and a single gold nanoparticle using PRET-MIS. When the absorption spectrum of the metal–ligand complex matches with the scattering spectrum of the gold nanoparticle, it induces energy transfer, resulting in a distinguishable quenching dip on the gold nanoparticle scattering spectrum. Reproduced with permission from230. Copyright 2009 Springer Nature. h Schematic illustration of quantum biological electron tunneling (QBET). QBET spectroscopy uses PRET to observe real-time optical detection of quantum biological electron tunneling and electron transfer in mitochondrial cytochrome c during cellular apoptosis and necrosis in living cells. i Schematic illustration of reverse plasmon resonance energy transfer (rPRET). Monitoring dynamic intercellular communication can be achieved by interfacing plasmonic nanoantennas with resonating black hole quencher (BHQ-3) molecules, enabling cell–cell signaling detection through enzymes like azoreductase released via EVs or microvesicles (MVs).

Localized surface plasmon resonance

Localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) arises from the collective oscillation of free electrons throughout the entire metal nanostructure, leading to strong light absorption at specific wavelengths (Fig. 5b). In LSPR, the electromagnetic field decays exponentially with a length of approximately 5–10 nm, which is highly sensitive to the refractive index of the solution near the surface. Compared to SPR, LSPR offers higher spatial resolution due to the nanoscale confinement. This characteristic enables the development of refractive-index-based LSPR in biosensing fields148. This resonance, which depends on the refractive index, can be understood through the electrical resonance of an LCR circuit made up of an inductor (L), a capacitor (C), and a resistor (R). In this framework, the inductance is attributed to the material properties, the fringe capacitance is linked to the displacement current caused by the dipolar field interacting with the surrounding medium, and the resistance represents the limitations on electron oscillations at the surface147. In this model, the metal nanoparticle can be considered a nanoinductor, and the surrounding medium as a nanocapacitor, with capacitance directly related to the refractive index of that medium. The resonance frequency in electrical circuits is inversely proportional to (LC)1/2, which parallels plasmon resonance. Consequently, the plasmon resonance frequency rises as the refractive index of the surrounding medium drops. Diverse nanoplasmonic structures with different sizes and shapes are used to enhance the sensitivity of LSPR biosensors and maximize the Δλ (wavelength shift) upon biomolecule interactions149,150. The enhancement from plasmonic nanostructures has improved LSPR-based detection of biomolecules such as ATP151, proteins152,153,154, exosomes155.

Moreover, the LSPR-based technique can be integrated with lateral flow-based POC sensing devices that rapidly perform colorimetric detection156,157,158. Compared to conventional SPR, LSPR provides an advantage due to its high aspect ratio, enhancing the surface area for biomolecular interactions and improving compatibility with complementary detection methods, including SERS and surface-enhanced fluorescence (SEF)140,159. While LSPR offers certain benefits, it typically exhibits lower sensitivity to refractive index changes than conventional SPR. Nonetheless, its higher aspect ratio allows for enhanced accommodation of biomolecules on the surface of metal nanoparticles, which in turn boosts detection sensitivity. Recent studies have explored SPR–LSPR hybrid systems to optimize sensor performance140. Although LSPR shows significant potential for POC biosensing, it encounters hurdles like low selectivity in complex biological fluids, challenges in detecting membrane-associated species, and issues with integration in multiplexed platforms and POC devices. Tackling these obstacles is vital for the progress of LSPR-based biosensing technologies.

Surface-enhanced Raman scattering

Surface-enhanced Raman scattering160,161 is an enhancement technique where Raman scattering (vibrational excitation) signals of molecules adsorbed on nanoplasmonic surfaces are amplified by up to several orders of magnitude (Fig. 5c). The scattering shift in the Raman spectrum is the energy difference between the emitted photons related to the excited state of molecular vibration9. Theoretically, SERS enhancement primarily arises from an electromagnetic mechanism (enhancement factor of ~1010–1011)162, which contributes more significantly compared to the chemical enhancement mechanism (enhancement factor of 103)163,164,165. The electromagnetic field, generated by the activation of LSPR in plasmonic structures, enables molecules near the nanostructure’s surface to absorb the near-field, then excite unique molecular vibrations. Coupling between the plasmon and molecular dipoles amplifies Raman polarizability, transmitting a far-field SERS signal of the molecule’s chemical fingerprint166. However, the most substantial SERS enhancements are confined to regions extremely close to the substrate, where the intensity decreases drastically with distance (as r−10 for spheres). The localized areas, known as SERS hotspots, exhibit enhancement factors ranging from 108 to 1012. They are often found at nanotips, interparticle gaps, and particle-substrate junctions167,168,169,170. Therefore, to increase SERS sensitivity, various hot spot-containing plasmonic optical antennas, with enhancement factors above 1010, were observed in individual gold nanocrescents and nanostars with sharp edges23,171. Hybrid nanostructure arrays with an enhancement factor of 107 exhibit a detection limit down to 10−15 M172,173. The large enhancement from plasmonic nanostructures has enabled their use in real-time monitoring molecular fingerprints of biomolecules (DNA, protein, lipid, exosomes)174,175,176, imaging in living cells177, and monitoring cellular processes at the single-cell level178. However, in contrast, the intrinsic ultra-sensitivity of SERS can be disadvantageous for accurate quantification. This sensitivity is strongly localized within nanogaps or nanotips of nanostructures, typically 1–10 nm, where intense local electromagnetic enhancement occurs179. Metal colloids and nanosubstrates can be easily aggregated, contaminated, and degraded under ambient conditions180. Additionally, fluctuations in laser intensity and optical alignment further contribute to the signal’s instability, compromising measurement reliability181. Moreover, SERS applications for detecting large molecules or cells, especially in complex biological matrices, remain a challenge due to the weak interaction between macromolecules and active surfaces and the low scattering cross-section of such molecules182. SERS also suffers from a high background noise level when the detected signal is weak, making signal extraction challenging and necessitating extensive data processing183 or the application of AI-based analysis184.

In this context, digital-SERS is becoming an alternative method for quantitative analysis, addressing the challenge of reduced analyte numbers, as long as a positive signal is generated185. Digital-SERS relies on the Poisson distribution principle, controlling the ratio between analytes and SERS substrates to ensure accurate single-molecule detection. It uses a binary detection system, “1” for positive signal and “0” for negative signal, allowing analyte numbers to be determined quantitatively181. While quantification at extremely low concentrations remains challenging, increasing the number of measurement events can significantly improve statistical reliability.

Plasmonic enhanced fluorescence (PEF)

Plasmonic surfaces and nanostructures have been shown to effectively enhance fluorescent reporters’ intensity over 103 magnitudes186,187,188 via locally intensified electromagnetic fields in biomolecular assays189,190,191,192. However, plasmonic properties of metal nanostructures affect fluorescence in two opposing ways: fluorescent emission enhancement or fluorescence quenching. Surface plasmon-quenched fluorescence occurs when a fluorophore is located within 10 nm of a plasmonic surface, leading to significant fluorescence quenching due to surface plasmon-induced resonance energy transfer from the excited state of the fluorophore to the surface plasmons of the nanoplasmonic structures193,194. By contrast, surface plasmon-enhanced fluorescence can occur at slightly larger distances, where the plasmonic field enhances the local electromagnetic field, increasing the fluorophore’s excitation rate and radiative decay rate194 (Fig. 5d). A metal nanocube film showed fluorescence lifetime measurements indicating fluorescence emission intensity increasing over a factor of 3 while sustaining high quantum efficiency (>0.5) and high directional emission achieving a collection efficiency of 84%195. A signal enhancement of nearly 3000-fold has been achieved by combining multiple factors: enhanced excitation, highly directional light extraction, improved quantum efficiency, and suppression of blinking through modifications to the quantum dot surface196. Modified nanorods (fluorescence enhancers) with light emitter (molecular fluorophores), spacer layer, and recognition element (such as biotin) can enhance fluorescence emission rate by over 6700-fold compared to an 800 continuous wave (CW) fluorophore and improve the sensitivity in fluorescence-linked immunoassays by approximately 4750-fold197. Using recent advances in plasmonic substrates for fluorescence enhancement, personalized POC devices can overcome the major challenges to rapid, sensitive, and specific diagnosis of diseases155,198,199,200,201,202. Surface plasmon-quenched and surface plasmon-enhanced fluorescence can be combined for selective detection of nucleic acids203,204,205,206, pathogens200,207, and cellular internalization208.

However, the distance sensitivity between fluorophore and metal, at which quenching and enhancement occur, is difficult to predict and control209. This difficulty leads to suppressed detection results and reduced signal fidelity in biosensing diagnosis. Therefore, functional spacer layers between fluorophores and metallic surfaces have been designed with precise thickness control and are now commercially available, such as atomically thin hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN)210, polysiloxane copolymer film211, dielectric layers212, or polydopamine (PDA)-coated plasmonic nanocrystals213.

Plasmonic dimer

Due to the complicated nature of designing plasmonic nanostructures for enhanced fluorescence emission, strong light-scattering plasmonic optical antennas can solve the problem corresponding to fluorophores117. Compared to fluorophore molecules or quantum dots, an increase in intensity of up to 103–104 can be observed in single gold nanoparticle-conjugated DNA probes coupled with target molecules9,214,215. The hybridization of nanoparticle probes with a single target mRNA leads to the formation of nanoparticle dimers with minimal interparticle spacing, causing a spectral peak shift resulting from strong plasmonic coupling214 (Fig. 5e). The scattering intensity of the nanoparticle dimer was approximately 4.7-fold higher than that of the monomer214,216. This phenomenon allows plasmonic gold nanoparticle dimer probes to be used for quantitative imaging of target mRNA and even multiple mRNA splice isoforms in living cells, which cannot be observed by fluorophore-based probes214. Moreover, the enhancement factors of up to approximately 105 have been reported for the two-dimensional (2D) nanoparticle arrays215,217,218.

The electromagnetic intensity in the space between two particles rises as the distance reduces from infinity to about 1 nm, resulting in a redshift of the energy mode that indicates stronger plasmonic coupling219. However, when the gap falls below 1 nm, the quantum tunneling of electrons across particle surfaces becomes significant, causing a notable reduction in electromagnetic field intensity220,221. The effectiveness of plasmonic utilization depends on selecting suitable nanoparticles, carefully controlling the nanogap for optimal coupling, and implementing molecular functionalization within the gap of the plasmonic nanoantenna222. Plasmonic optical antennas can be further functionalized to target biomolecules, enabling real-time tracking of molecular events117,223,224. This ability provides a valuable approach to investigating gene-related biological issues and diseases, including cancer, at the single-cell level.

Plasmon resonance energy transfer (PRET)

In addition to vibrational excitations, the molecular electronic fingerprint can be captured and quantified through plasmon resonance energy transfer (PRET)225 (Fig. 5f). PRET represents the overlap between the resonance peaks of plasmon nanoparticles and the electronic resonance peaks of the biomolecule. Energy transfer likely occurs via dipole-dipole interactions between the resonating plasmon dipole in the nanoparticle and that of the biomolecule. If the plasmonic resonance energy aligns with the molecular electronic transition energy, the energy is transferred to the molecule226. The scattering spectrum of the nanoplasmonic optical antennas exhibits quantized quenching dips at the molecular absorption peaks (electronic transition frequency)5,9. Using a PRET nanosensor, plasmon quenching dips were observed to detect energy transfer in hemoglobin molecules and cytochrome C on a single nanoparticle’s surface12. However, individual plasmonic antennas have specific spectral widths, which restrict their ability to monitor multiple types of analytes or signals. This limitation complicates broad-spectrum sensing and multiplexing detection. Current nanoparticle fabrication technologies, including printing and patterning methods, exhibit nonuniform spatial detection, which diminishes the reliability of PRET measurements, such as chemical diffusion or cellular secretion. Due to spectral and spatial limitations in PRET, continuous and comprehensive tracking is hindered, especially in complex environments like live-cell monitoring. However, metasurface-based multiplexed platforms can be precisely designed to generate specific scattering spectra by gap plasmon and grating effects to overcome the limitations in FRET spectroscopy. These metasurfaces are composed of controllable arrays of metapixels, capable of spanning the entire visible spectrum with high spatial resolution (~1.5 µm) and supporting real-time, multiplexed detection of molecular interactions over a broad field of view with distinct absorption frequencies within the visible range227. Moreover, PRET can be optimized over a wide spectrum, such as UV or NIR, depending on the characteristics of metallic nanoparticles that determine their plasmon resonance wavelengths in these spectral regions228,229.

Plasmonic resonance energy transfer-based metal ion sensing (PRET-MIS)

Plasmonic resonance energy transfer-based metal ion sensing (PRET-MIS) nanospectroscopy merges metal-ligand coordination chemistry with plasmonic resonance energy transfer, resulting in enhanced sensitivity and molecular specificity at the nanoscale (Fig. 5g). This technique employs a gold nanoplasmonic probe to initiate selective energy transfer, which leads to resonant quenching in Rayleigh scattering by aligning electronic absorption bands with plasmonic resonance frequencies. Consequently, it enables accurate metal ion detection, delivering both sensitivity and selectivity through quantitative quenching that depends on the local ion concentration230.

Quantum biological electron transfer (QBET)

The principle of quantum biological electron transfer or tunneling (QBET) is similar to the PRET method. However, by precisely controlling the function of the linker molecules as tunnel junctions for QBET detection, electron transfer can be observed in live cells and living enzymes (Fig. 5h). By using QBET spectroscopy, real-time electron transfer in the electron transport chain during cytochrome C dynamics was first observed at the molecular level11. Different optical nanostructures, such as gold nanospheres231, gold nanorods232, gold plant viruses233, gold bipolar nanoelectrodes234, plasmonic cavities235, and pixelated metasurfaces227, have been developed to study and modulate electron transfer dynamics in biological reactions, as well as real-time biomolecular spectroscopic imaging236.

Reverse PRET

In contrast to PRET, reverse PRET can be intentionally employed for selective energy transfer for plasmonic quenching when molecular binding leads to a plasmonic resonance shift or intensity extinction. Owing to this phenomenon, gold nanorods functionalized with black hole quencher molecules (BHQ-3) enable real-time enzyme activity monitoring in single bacterial cells by detecting AzoR released via outer membrane vesicles, which cleaves the azo bond in BHQ-3, thereby recovering the scattering intensity of gold nanorods13 (Fig. 5i).

Data analysis and transmission in molecular diagnostics

The COVID-19 pandemic has shifted diagnostic testing from centralized laboratories to the POC platforms. Modern standard POC diagnostics follow REASSURED criteria (real-time connectivity, ease of specimen collection, affordable, sensitive, specific, user-friendly, rapid and robust, equipment-free or simple, and deliverable to end-users)237 to achieve high analytical sensitivity at low concentrations of biomarkers in biological samples. Therefore, there is a need for real-time data processing and error reduction to maintain REASSURED criteria in clinical settings. With the widespread integration of automated molecular assays into portable devices, the trend has shifted towards real-time connectivity, mobile data sharing, and integration with cloud-based health systems. These systems enable data to be transmitted and analyzed in real-time for quality control and long-term monitoring of public health238. Moreover, integration of POC sensors with AI- and machine learning (ML)-assisted smartphone-based assays can enhance image analysis, data and signal processing, and quantitative interpretation in sensing methods such as lateral flow assays (LFAs), NAATs, and optical-based technologies239,240. Designed AI and deep learning algorithms can be optimized to process complex datasets and accurately recognize small changes in protein, DNA, or RNA biomarkers from exosomes175 from multiplex or digital sensing approaches174,184. Moreover, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) were used as an alternative method to enhance optical-based diagnostics, offering faster and more reliable results241.

Commercial plasmonic detection system

Recently, various commercial optical techniques integrating nanoplasmonic structures have been used for POC diagnostics, such as SPR detection, handheld SERS, and enhanced colorimetric detection in lateral flow assays242,243,244.

As shown in Fig. 6a, Biacore was the first SPR-based sensor developed and is widely used for real-time, label-free analysis of molecular interactions in areas ranging from drug discovery to biotherapeutic development245. It is designed to qualify and quantify antibodies and proteins by evaluating their binding interactions, affinities, and kinetic profiles, from rapid association to slow dissociation rates, all while maintaining their biological function. Biacore SPR biosensors are designed with three core technologies: an optical detector system, a 50-nm layer of gold on the sensor chip, a microfluidic chip and liquid handling system246. Biacore systems generally achieve a LOD around 50 Da for low-molecular-weight analytes and provide various assays and monitoring capabilities to enhance the overall sensitivity of the system246. However, Biacore systems require careful surface chemistry optimization, and can be limited by non-specific binding in some applications. Furthermore, the system necessitates a large machine and, as a result, it tends to be quite costly. In contrast, Carterra offers a specialized high-throughput surface plasmon resonance (HT-SPR) system explicitly designed for antibody discovery and characterization (Fig. 6b). This HT-SPR technology facilitates 192 real-time interactions with molecules as small as 100 Da, utilizing the high resolution of a charge-coupled device (CCD) camera. For the kinetic and affinity measurement, HT-SPR can characterize up to 768 fragments and 1152 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs). Moreover, Carterra also develops epitope binning, which can handle interaction mapping up to 191 × 191 mAb–mAb comparisons and epitope mapping by screening up to 96 mAbs against a panel of 96 peptides. Beyond these workflows, Carterra offers flexible multiplexing, accommodating up to 192 ligands, including mutants, target variants, or controls, to meet a wide range of advanced biotherapeutic discovery and characterization needs247. While Carterra offers remarkably high-throughput capabilities and advanced epitope binning tools, its performance comes with trade-offs in sample consumption, system and dataset complexity, bulky instruments, and initial investment. When experiments are conducted by skilled users following SPR best practices with flexible assay design, both Biacore and Carterra platforms yield almost identical, reliable results, making them leading SPR platforms for label-free biomolecular interaction analysis and accelerating antibody library characterization toward clinical development248. However, in the development of POC diagnostic devices, handheld or palm-sized platforms have attracted significant attention as alternatives to bulky SPR instruments, while maintaining the capability to detect single viruses and particles smaller than 100 nm249.

a Biacore SPR sensor chip provides real-time, ready-to-go analysis of a wide range of molecular interactions, providing kinetics, affinity, and binding data (Credit: Cytiva Life Sciences (cytivalifesciences.com)). b Carterra SPR sensors integrate with HT-SPR technology, enabling fragments and small molecules screening and antibody discovery. c Detection principle of NG-Test CARBA 5 Lateral Flow Assay, NG Biotech. Reprinted with permission from ref. 250. Copyright 2018 Oxford Academic. d Principle of detection method for Nucleic Acid Lateral Flow Immunoassay (NALFIA), Pocket Diagnostic. Reprinted with permission from ref. 254. Copyright 2024 Springer Nature. e Klarite SERS substrate on an array of inverted pyramid structures (credit: optics.org). Reprinted with permission from ref. 287. Copyright 2011 Applied Spectroscopy. f Commercial Ocean Insight SERS substrate made of gold or silver, mounted in a microscope slide. Reprinted with permission from ref. 258. Copyright 2023 Springer Nature. g Nanopartz Plasmonic PCR and its 8-channels for POC system (credit: Nanopartz Inc. (nanopartz.com)). h Nexless P–IV transforms is an innovative Plasmonic PCR Technology, combining advanced plasmonic gold nanorod nanoparticles with real-time quantitative PCR. (Credit: Nexless Healthcare (nexlesshealthcare.ca)).

Colorimetric lateral flow assays are widely favored in POC devices for their simplicity and low cost, enabling naked-eye detection of target biomarkers. LFAs utilize gold nanoparticles for rapid testing; however, their red color restricts their applicability for multiplex assays32. The NG-Test CARBA 5 by NG Biotech is a multiplex lateral flow immunoassay designed using gold nanoparticles conjugated with monoclonal antibodies that are specific for the five most prevalent carbapenemase families: KPC, OXA-48-like, VIM, IMP, and NDM (Fig. 6c). All 185 carbapenemase isolates were correctly detected in less than 15 min with achieving overall 100% sensitivity and 95.3–100% specificity250. By a simple protocol with minimal hands-on time, no specialized instrument, and excellent sensitivity and specificity, the CARBA5-LFA has been cleared by the FDA251 and registered in the European Database on Medical Devices (EUDAMED)252 as an in vitro diagnostic device. Another commercial Nucleic Acid Lateral Flow Immunoassay (NALFIA) from Pocket Diagnostic is a hybrid detection method combining nucleic acid amplification with LFA for visual detection of target DNA/RNA sequences (Fig. 6d). The target sequence is amplified initially with a fluorophore-labeled primer (biotin, fluorescein (FAM) or digoxigenin), then introduced onto the lateral flow strip, where it binds to nanoparticle-conjugated antibodies, producing a visible color change253. NALFIA obtains high sensitivity and specificity, comparable to real-time PCR254; however, it still suffers from quantitative accuracy, sensitivity and specificity at lower concentrations, and multiplexing capacity.

Highly scalable SERS sensors have emerged as the next generation in molecular detection due to their high sensitivity, noninvasiveness, and multiplex capability164,255. The commercially available Klarite substrate was fabricated using photolithography techniques on a silicon wafer (Fig. 6e) to fabricate an inverted pyramid array of hot spots with highly reproducibility and uniformity256. Under ideal conditions, these substrates obtain a typical relative standard deviation (RSD) from 10 to 15% under drop-and-dry conditions, with low substrate background257. Another ready-to-use SERS substrate from Ocean Insight is designed for rapid and sensitive detection of chemicals and biomolecules (Fig. 6f). The SERS active areas (5.5 mm diameter circle) are typically made of gold (excitation wavelength of 785 nm) or silver (excitation wavelength of 532 nm), offer reliable performance, and can be easily integrated with a handheld Raman spectrometer. A comparison of the LOD for three commercial SERS substrates from Hamamatsu, SERSitive, and Ocean Insight shows that at a 10−6 M concentration, SERSitive and Ocean Insight offer better performance. However, background noise limits their effectiveness at lower concentrations. However, at 10−8 M, the Hamamatsu substrate demonstrates higher sensitivity for thiophenol detection, especially at 633 nm excitation258. Although the commercial SERS substrates are well recognized, their practical applications remain challenges, including low reproducibility, small active surface areas, batch-to-batch variation, and high manufacturing costs.

Apart from direct virus capture, nucleic acid amplification plays a vital role in POC diagnostics. As illustrated in Fig. 6g, the photonic PCR platform developed by Nanopartz utilizes gold nanoparticles and gold nanorods in the PCR reaction mixtures.These particles rapidly convert light to heat, with over 90% absorption and 100% efficiency, achieving heating rates of up to 20 °C/s259. The Nanopartz photonic PCR prototype is simple, fast, offering thermocycling capability and highly specific amplification. Moreover, it is fully compatible with standard PCR protocols, making it a promising candidate for the integrating plasmonic and conventional PCR into a self-powered, portable POC device. The ultra-fast Nexless Kimera P-IV plasmonic RT-qPCR technology integrates gold nanorods and vertical surface-emitting lasers to replace conventional heating methods like Peltier blocks. This approach enables rapid thermal cycling and achieves a PCR efficiency of 88.3% in under 10 min (Fig. 6h). The device can detect as few as 1 DNA copy with 100% accuracy in direct-urine analysis260. However, to achieve reliable results, careful biological reagents preparation - such as primer designs - is needed, and further clinical validation is still required.

Future perspectives and challenges

While nanoplasmonics-based actuators for the selective trapping and enrichment of biological samples and biosensors for the sensitive detection of protein, RNA, and DNA biomarkers hold the promise of revolutionizing biomedical diagnostics, several challenges—including fabrication scalability, stability, and specificity—must be addressed to fully realize their potential for clinical applications.

Scalability and cost-effectiveness

The fabrication of highly organized and reproducible nanostructures continues to represent one of the principal challenges in the area of nanoplasmonics-based biosensors.

The prevailing top-down fabrication methods for laboratory-scale applications with resolution of 100 nm or better, including electron beam lithography (EBL) and focused ion beam (FIB) lithography, are characterized by high precision; however, they are also time-intensive, costly, and lack the scalability necessary for mass production. This scenario has engendered a demand for low-cost alternative manufacturing methods to facilitate commercialization.

In this context, large-scale and cost-effective top-down lithography techniques, such as nanoimprinting, nanostencils, interference lithography, and deep and extreme ultraviolet lithography, have emerged as viable alternative manufacturing strategies261,262. Attainment of uniformity and high throughput remains a critical concern. Low-cost, disposable biosensor chips are preferred to prevent cross-contamination and eliminate the need for complex cleaning processes when working with biological samples. Therefore, systems that support single-use cartridges paired with a stand-alone reader represent the most practical solution. However, intensive research is necessary to address challenges in fabrication methods as well as the cost of biomaterials (e.g., reagents) required to manufacture inexpensive single-use cartridges263.

Complex biological sample handling

The extensive range of analytes and matrix compositions—such as bodily fluids in medical diagnostics and food samples in food safety—presents distinct challenges for sample collection and processing, which are essential for on-site biosensing. Microfluidic systems demonstrate significant utility in biosensor integration by facilitating multiplexed functions such as sample preparation, concentration, and analyte transport, while simultaneously minimizing the volume of required samples and limiting the utilization of expensive reagents264,265,266. Furthermore, the nanoplasmonic actuators enhance purification and selectively enrich targeted biomarkers. Nanoplasmonic sensors can be integrated with nanoplasmonic actuators into a smart integrated photonics and microfluidic integrated circuit (IC) system, which can be employed for sample preparation, as previously discussed, and holds promise for integration with microfluidics. This combination aims to achieve high specificity and sensitivity in the detection of specific biomolecules within complex samples. However, several challenges remain that hinder the advancement of technology transfer and commercialization, primarily due to the complexities such as material compatibility, alignment precision, and fluidic control that are involved in integrating all components into a single, portable platform265. In addition, efficiently transferring light from an external source to the plasmonic structure within the microfluidic channel without significant loss requires clear optical paths that can be obstructed by microfluidic materials or channel designs.

Surface chemistry for biofunctionalization

While sensitivity, resolution, and detection speed represent crucial metrics for the assessment of nanoplasmonic biosensor performance, surface chemistry plays a vital role in determining the efficacy of biosensing through molecular recognition between receptors and targets. Thus, it is imperative that the surface chemistry of nanoplasmonic sensors is both robust and reliable to facilitate effective biofunctionalization, ensuring stable binding of biomolecules such as antibodies or aptamers. However, the nonplanar and heterogeneous characteristics of nanoplasmonic surfaces pose significant challenges for surface modification.

Nanoplasmonic surfaces, which often include three-dimensional or non-planar nanostructures such as nanoholes, nanopillars, or nanoparticles and may incorporate multiple materials, present greater challenges for uniform biofunctionalization compared to flat surfaces. This complexity necessitates the implementation of innovative approaches, such as material-selective or site-specific functionalization techniques.

Moreover, integrating nanoplasmonic sensors with biomembranes allows for the incorporation of membrane-bound receptors and mitigates nonspecific binding by passivating the sensor surface267. Furthermore, a notable lack of analytical methods capable of adequately evaluating and quantifying each step of functionalization persists, a gap that is crucial for assessing the diffusion of these sensors within the market263.

Emerging directions

Advancements in materials science and optical physics are anticipated to facilitate further progress in nanoplasmonic biosensors. Recently, 2D materials such as graphene, transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs), and black phosphorus have been utilized with increasing frequency in nanoplasmonic biosensing, owing to their distinctive properties, thereby playing a crucial role in the detection of various biomolecules268. Low-dimensional van der Waals (vdW) materials provide distinct advantages for nanophotonic biosensing by generating highly confined polaritonic waves. Their diminished dimensionality—illustrated by two-dimensional graphene—augments plasmonic field confinement, leading to enhanced sensitivity and performance compared to conventional nanophotonic systems reliant on surface plasmons in metallic films269. Various biosensing techniques, including SPR270, FRET, and evanescent wave-based methods, along with the associated characteristics, synthesis approaches, and integration techniques of two-dimensional materials, have attracted significant attention. Alternative materials capable of generating plasmonically enhanced light–matter interactions have garnered considerable interest, particularly copper, aluminum, indium, and magnesium, as they present a cost-effective substitute for conventional metals such as gold and silver in large-scale applications271. Integrating microfluidics14, flexible electronics272, and wireless communication273 will facilitate the development of compact, portable, and user-friendly POC devices. Furthermore, the incorporation of AI274 and ML for real-time data analysis and interpretation will substantially enhance diagnostic accuracy, providing label-free, multiplexed detection at ultra-low concentrations. Through sustained interdisciplinary collaboration, nanoplasmonic biosensors hold the potential to transform healthcare, environmental monitoring, and biosecurity by means of rapid, reliable, and accessible sensing technologies.

Conclusion and outlook

In this review, we examine the advancements in nanoplasmonic optical antennas utilized as biosensors and actuators within the realm of molecular diagnostics. Integrated nanoplasmonic biosensors have the potential to optimize the sample preparation process while inflicting minimal damage through plasmonic trapping. Moreover, they facilitate label-free, real-time detection of a singular target through plasmonic photothermal actuation for the purposes of sample enrichment and lysis. Recent advancements in integrated molecular diagnostic systems utilizing nanoplasmonics demonstrate high sensitivity, rapid response times, and portability for disease detection through the application of the plasmonic photothermal effect in NAATs, rendering them particularly beneficial in resource-limited settings. Smartphones equipped with integrated detection systems utilizing plasmonic biosensors and sample preparation platforms will establish an efficient molecular diagnostic system. This system amalgamates sample enrichment, lysis, amplification, and detection processes onto a singular chip. Such systems represent promising instruments for remote healthcare and personalized health monitoring. Furthermore, nanoplasmonic optical antennas as actuators and biosensors exhibit substantial potential not only for advanced real-time healthcare tracking and monitoring but also for elucidating life sciences and quantum biology at the single-cell level. For instance, nanoplasmonics serve to illustrate intracellular quantum processes, such as electron transfer in mitochondria11 and bacterial communication13 with one another as well as with host cells, thereby illuminating the field of quantum biology. Furthermore, the cavity quantum electrodynamic properties stemming from the strong light-matter interaction between surface plasmons and emitters-whether they be fluorescent probe-tagged proteins or biomolecular emitters such as chlorophyll275,276, can be a promising quantum plasmonic biosensor platform that does not necessitate sophisticated measurement tools or cryogenic temperatures. Additionally, alternative plasmonic materials, such as graphene derivatives, may be integrated into biosensor systems277. Nanoplasmonic optical antennas are utilized in high-speed hyperspectral imaging systems to observe and analyze biomolecular interactions within living biological cells at a single-copy resolution. Future advancements in nanoplasmonics are expected to transition from research to practical healthcare applications, thereby fostering innovative diagnostics and personalized medicine.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Marchenko, V. Y. et al. Characterization of H5N1 avian influenza virus isolated from bird in Russia with the E627K mutation in the PB2 protein. Sci. Rep. 14, 26490 (2024).

Qun, L. et al. Early Transmission Dynamics in Wuhan, China, of Novel Coronavirus–Infected Pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 1199–1207 (2020).

Burki, T. Outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019. Lancet Infect. Dis. 20, 292–293 (2020).

Novotny, L. & Van Hulst, N. Antennas for light. Nat. Photonics 5, 83–90 (2011).

Liu, W., Chung, K., Yu, S. & Lee, L. P. Nanoplasmonic biosensors for environmental sustainability and human health. Chem. Soc. Rev. 53, 10491–10522 (2024).

Islam, M. M. & Koirala, D. Toward a next-generation diagnostic tool: A review on emerging isothermal nucleic acid amplification techniques for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 and other infectious viruses. Anal. Chim. Acta 1209, 339338 (2022).

Yu, E. S. et al. Highly Efficient On-Chip Photothermal Cell Lysis for Nucleic Acid Extraction Using Localized Plasmonic Heating of Strongly Absorbing Au Nanoislands. ACS Appl Mater. Interfaces 15, 34323–34331 (2023).

Cho, B. et al. Nanophotonic Cell Lysis and Polymerase Chain Reaction with Gravity-Driven Cell Enrichment for Rapid Detection of Pathogens. ACS Nano 13, 13866–13874 (2019).

Xin, H., Namgung, B. & Lee, L. P. Nanoplasmonic optical antennas for life sciences and medicine. Nat. Rev. Mater. 3, 228–243 (2018).

Kneipp, J., Kneipp, H. & Kneipp, K. SERS—a single-molecule and nanoscale tool for bioanalytics. Chem. Soc. Rev. 37, 1052–1060 (2008).

Xin, H. et al. Quantum biological tunnel junction for electron transfer imaging in live cells. Nat. Commun. 10, 3245 (2019).

Liu, G. L., Long, Y.-T., Choi, Y., Kang, T. & Lee, L. P. Quantized plasmon quenching dips nanospectroscopy via plasmon resonance energy transfer. Nat. Methods 4, 1015–1017 (2007).

Lu, D. et al. Dynamic monitoring of oscillatory enzyme activity of individual live bacteria via nanoplasmonic optical antennas. Nat. Photonics 17, 904–911 (2023).

AbdElFatah, T. et al. Nanoplasmonic amplification in microfluidics enables accelerated colorimetric quantification of nucleic acid biomarkers from pathogens. Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 922–932 (2023).

Nakatsuji, H. et al. Thermosensitive Ion Channel Activation in Single Neuronal Cells by Using Surface-Engineered Plasmonic Nanoparticles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 11725–11729 (2015).

Jain, P. K., Lee, K. S., El-Sayed, I. H. & El-Sayed, M. A. Calculated absorption and scattering properties of gold nanoparticles of different size, shape, and composition: Applications in biological imaging and biomedicine. J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 7238–7248 (2006).

Turkevich, J., Stevenson, P. C. & Hillier, J. A study of the nucleation and growth processes in the synthesis of colloidal gold. Discuss Faraday Soc. 11, 55–75 (1951).

Yu, Y. Y., Chang, S. S., Lee, C. L. & Wang, C. C. Gold Nanorods: Electrochemical Synthesis and Optical Properties. J. Phys. Chem. B 101, 6661–6664 (1997).

Oldenburg, S. J., Averitt, R. D., Westcott, S. L. & Halas, N. J. Nanoengineering of optical resonances. Chem. Phys. Lett. 288, 243–247 (1998).

Sun, Y. & Xia, Y. Shape-Controlled Synthesis of Gold and Silver Nanoparticles. Science ((1979)) 298, 2176–2179 (2002).

Charnay, C. et al. Reduced symmetry metallodielectric nanoparticles: chemical synthesis and plasmonic properties. J. Phys. Chem. B 107, 7327–7333 (2003).

Nehl, C. L., Liao, H. & Hafner, J. H. Optical properties of star-shaped gold nanoparticles. Nano Lett. 6, 683–688 (2006).

Lu, Y., Liu, G. L., Kim, J., Mejia, Y. X. & Lee, L. P. Nanophotonic crescent moon structures with sharp edge for ultrasensitive biomolecular detection by local electromagnetic field enhancement effect. Nano Lett. 5, 119–124 (2005).

Bukasov, R. & Shumaker-Parry, J. S. Highly tunable infrared extinction properties of gold nanocrescents. Nano Lett. 7, 1113–1118 (2007).

Liu, G. L., Lu, Y., Kim, J., Doll, J. C. & Lee, L. P. Magnetic nanocrescents as controllable surface-enhanced Raman scattering nanoprobes for biomolecular imaging. Adv. Mater. 17, 2683–2688 (2005).

Li, D., Zhang, Q., Xing, L. & Chen, B. Theoretical and in vivo experimental investigation of laser hyperthermia for vascular dermatology mediated by liposome@Au core–shell nanoparticles. Lasers Med. Sci. 37, 3269–3277 (2022).

Bhaskar, S. & Lim, S. Engineering protein nanocages as carriers for biomedical applications. NPG Asia Mater. 9, e371–e371 (2017).

Xia, Y. et al. Gold nanocages: from synthesis to theranostic applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 44, 914–924 (2011).

Wang, T. et al. Multifunctional hollow mesoporous silica nanocages for cancer cell detection and the combined chemotherapy and photodynamic therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 3, 2479–2486 (2011).