Abstract

The rapid spread of respiratory viruses and their similar symptomatology pose significant challenges for early diagnosis, transmission control, and effective clinical management. We introduce a multianalyte diagnostic platform based on plasmonics for the rapid identification, discrimination, and quantification of viral antigens for the most common respiratory viruses (SARS-CoV-2, Influenza A/B, and RSV) in nasopharyngeal swabs. The biosensor chips are functionalized with four specific antibodies targeting viral nucleoproteins and are integrated into a single-use microfluidic cartridge, reaching low detection limits (ng/mL level). A clinical validation with positive and negative samples (n = 46) demonstrates an excellent correlation with PCR-based molecular tests. Furthermore, the novel diagnostic platform exhibits high sensitivity (97.22%) and specificity (100%), overcoming limitations associated with rapid antigen tests. Together with its accuracy and user-friendly design, our multibiosensor is positioned as a disruptive diagnostic tool for rapid and multiplexed diagnosis of viral infections at the point-of-care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Infectious diseases have become a major health concern in the 21st century, accounting for billions of cases annually and resulting in increasing mortality rates1. While most infections can be effectively treated and cured, the lack of rapid and reliable diagnostic methods for early detection and efficient population screening can result in serious health complications and uncontrolled widespread outbreaks due to their rapid transmission2,3. A clear example is viral respiratory tract infections, such as severe bronchiolitis caused by the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)4 and new emerging variants of coronaviruses, including Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)5. The incidence of these respiratory infections is alarmingly increasing, with more frequent outbreaks of emerging viruses, resulting in significant economic and social impacts6. The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed the deficient preparedness of our society, both in developing and developed regions, to respond effectively to new pathogens. However, the problem is not limited to emerging viruses; it also extends to recurrent seasonal viral pathogens7,8. For instance, Influenza viruses infect approximately one billion people globally each year, leading to 3 to 5 million cases of severe illness and resulting in up to 650,000 deaths annually9.

The seasonality of respiratory viruses shows a peak incidence of Influenza, RSV, and SARS-CoV-2 between November and April in the Northern Hemisphere. The co-circulation of these viruses and their overlapping clinical symptoms —such as fever, headache, sore throat, and cough— pose significant challenges during the winter season. This overlap in clinical manifestations complicates the ability to distinguish between these viral infections based solely on symptoms. To effectively control the spread of respiratory viruses, guide timely treatment decisions, and prevent widespread outbreaks, expanding access to rapid diagnostic testing for multiple pathogens is crucial10,11.

Routine laboratory tests based on nucleic acid amplification, particularly polymerase chain reaction (PCR), have become the gold standard for diagnosing respiratory viral infections12. These tests work by amplifying and identifying specific viral genome sequences using samples collected from nasopharyngeal or nasal swabs13,14. Many manufacturers have improved and adapted existing PCR technologies to enable real-time and multiplexed detection of 4 to 22 pathogens in a single test. Commercial systems such as BioFire FilmArray (BioMérieux, France), Xpert Xpress (Cepheid Inc., US), and QIAstat-Dx (Qiagen, Germany) deliver high sensitivity and specificity within 40 minutes to 2 hours15,16,17,18. However, their implementation is often restricted by the high costs of both instrumentation and disposable cartridges (typically ranging from $65–100 (Xpert Xpress) to $120–180 (BioFire and QIAstat) per cartridge). Additionally, the need for centralized laboratory settings further limits accessibility in resource-constrained environments. These limitations hinder their applicability for routine population-level surveillance during seasonal epidemic periods, for example, at primary care centers, where timely and accessible testing is essential to support clinical decision-making and to differentiate between co-circulating respiratory infections.

As an alternative to molecular tests, rapid antigen tests (RATs) based on lateral-flow assays can be used at the point-of-care by non-specialized personnel and the end-user. These tests allow for the rapid (<20 min) and direct recognition of specific structural proteins of viruses, including nucleoprotein (NP), spike (S), and hemagglutinin (HA), among others, in nasopharyngeal and nasal swab samples, providing a qualitative result. Currently, several manufacturers, such as Certest Biotec S.L. (Spain), SureScreen Diagnostics Ltd (UK), and Shenzhen Microprofit Biotech Co. (China), offer RATs that simultaneously detect Influenza, RSV, and SARS-CoV-2 in a single test. Studies have revealed that the performance of these tests is moderate or low, particularly in individuals with low viral load (i.e., asymptomatic patients or those in the early stages of infection), with varied sensitivity depending on the virus19,20,21.

Point-of-care alternatives are actively being developed, with biosensors representing a key technology under investigation for broad implementation. Electrochemical-based designs have been studied in various configurations to detect antigens, whole virions, or immune responses22,23. Similarly, optical biosensors have been widely explored as a viable alternative to multiple antigen tests, as these devices can offer straightforward, rapid, portable, and low-reagent consumption analyses with high sensitivity and selectivity24,25. Several examples have been reported for the individual and specific detection of respiratory virus antigens26,27,28. However, clinical validation with real samples remains limited, as shown by the few studies reported to date, mainly for SARS-CoV-229,30,31. Similarly, the ability to perform multiplexed identification for diagnostic applications has only been demonstrated in a handful of cases24,32.

Acknowledging the advantages that label-free plasmonics can offer for such purposes, we have advanced our proprietary technology33,34,35,36 towards a more versatile prototype that allows multianalyte detection for up to four different targets with a disposable cartridge design that facilitates the delivery of one single sample (Fig. 1). The device design ensures both sensitivity and rapid response in the four-channel configuration, with custom biofunctionalization being crucial to maximizing sensing performance and eliminating cross-talking among sensing areas37. In this work, we have fully implemented a diagnostic platform for the rapid identification, discrimination, and quantification of viral antigens from the four most common respiratory viruses: RSV, Influenza A and B, and SARS-CoV-2 in nasopharyngeal swab samples. The system combines a disposable microfluidic cartridge with integrated plasmonic chips functionalized with specific antibodies targeting each nucleoprotein (NP), enabling direct and label-free detection of multiple viral antigens in a single sample (see Fig. 1). The biosensor device detects and quantifies the viral antigens in the low ng/mL range in nasopharyngeal swabs, and it has been clinically validated using nasopharyngeal samples (n = 46) collected from hospital patients, including both positive and negative cases. Results were benchmarked against standard nucleic acid amplification tests and commercial rapid antigen tests, confirming the potential of this integrated cartridge-based multianalyte system for clinical use.

The biosensor device integrates all essential components (halogen lamp, spectrometer, and motorized stage) into a compact design. The device features a disposable cartridge with four sensing channels (CH1 – CH4), each biofunctionalized with a specific antibody for direct capture of viral NPs. The readout software provides a user-friendly interface for real-time monitoring of shifts in plasmonic resonance peaks (Δλ in nm) across all four channels, which are proportional to the amount of viral nucleoprotein present, enabling both qualitative and quantitative analysis. Created with BioRender. Ramirez Priego, P. (2025) https://BioRender.com/sx43f2m.

Results

Multiplexed assay development and analytical characterization

The biosensor device integrates all essential components into a compact design, utilizing external elements such as a white halogen lamp for illumination, a compact spectrometer for detection, and a motorized stage for sequential measurement across four sensing channels (CH1–CH4). These components can be housed in a portable case for easy handling and transportation. For standardizing the methodology during the laboratory phase, a conventional microfluidic setup using PDMS (polydimethylsiloxane) flow cells enabled real-time continuous measurements via active pumping. To enhance user-friendliness for routine use, we developed disposable cartridges compatible with both active and passive liquid delivery systems (see Fig. 1 and Fig. S1). Their performance was thoroughly evaluated before implementation in clinical validation with real samples (see Fig. 1).

To enable sensitive and specific detection of Influenza A, Influenza B, RSV, and SARS-CoV-2, we selected the viral nucleocapsid or nucleoprotein (NP) as the target antigen, due to its high abundance and intra-family conservation, which allows for early and differential diagnosis38,39. Capitalizing on the multiplexed architecture of the plasmonic biosensor, we have designed a biofunctionalized layout with four specific antibodies immobilized, targeting each one of the NP of the four viruses (see Fig. 1), which enables simultaneous detection, discrimination, and quantification of the four different viral NPs from a single sample. The specific arrangement of antibodies in the experiments is as follows: CH1 for Influenza B (anti-IBV), CH2 for RSV A/B (anti-RSV), CH3 for Influenza A (anti-IAV), and CH4 for SARS-CoV-2 (anti-COV). Antibodies were selected for their reported specificity towards their respective target viral proteins, with no cross-reactivity between A and B subtypes in the case of influenza. They were validated by the manufacturers to ensure broad recognition across various circulating variants and strains. The anti-RSV antibody used recognizes both RSV A and B subtypes, which is beneficial since both subtypes can often co-circulate and show comparable clinical severity.

To evaluate the overall specificity of the detection system, each viral nucleoprotein was individually injected at a relatively high concentration (2.5 µg/mL). This allowed the identification of any potential cross-reactivity between targets over the antibodies or any undesired binding to the surface at standard detection conditions. The biosensor response showed significant non-specific binding in the four sensing channels (Fig. 2A), especially relevant in the case of NPs of Influenza A, RSV A, and Influenza B, which the biosensor was unable to discriminate against. These interferences were removed by adding dextran sulfate (DS) to the buffer employed for conditioning the biofunctionalized chips before detection, an additive previously shown to effectively reduce non-specific interactions in similar studies35,40,41 (see Fig. 2B). High concentrations of each viral NP produced minimal response in non-target channels, confirming the absence of cross-reactivity and ensuring accurate discrimination among the viruses. The addition of DS to the running buffer significantly enhanced specific binding responses, for example, the signal for RSV A NP increased from 0.183 nm in PBST to 1.507 nm in PBST-DS, while remaining negligible in the other channels.

Effect of the buffer composition (PBST and PBST-DS). A Biosensor signal response for the four distinct viral NP (each one at a concentration of 2.50 µg/mL) employing PBST as running conditioning buffer. B Biosensor signal response for the four distinct viral NP (each one at a concentration of 2.50 µg/mL) employing PBST-DS as running buffer. In all cases, the nucleoprotein solutions were prepared in PBST buffer and injected individually across the four biofunctionalized channels (CH1 – CH4), each coated with an antibody specific to one viral NP. The position of each antibody is as follows: CH1 – anti-IBV; CH2 – anti-RSV; CH3 – anti-IAV, and CH4 – anti-COV. Each column represents the mean ± SD of biosensor responses from duplicate measurements. Signals indistinguishable from background levels are marked with an asterisk (*), indicating no detectable response in those channels.

Standard samples containing individual viral NPs were injected over the biofunctionalized sensor surface. Figure S2 presents representative real-time sensorgrams for four viral NP at different concentrations: Influenza B (0.50 μg/mL), RSV B (2.50 μg/mL), Influenza A (1 μg/mL), and SARS-CoV-2 (2.50 μg/mL). These results demonstrate the sensor’s ability to discriminate in real-time between different viral NPs, even at both high and low concentrations.

Under these conditions, the biosensor was calibrated by generating dose-response curves for each virus. In channel 2 (CH2), two calibration curves were obtained, one for the nucleoprotein from RSV A and another for RSV B. The results obtained are summarized in Table 1 and Fig. S3, achieving a limit of detection (LOD) of 31.43 ng/mL for Influenza B NP, 30.63 ng/mL for RSV A NP, 19.95 ng/mL for RSV B NP, 118.18 ng/mL for Influenza A NP, and 10.60 ng/mL for SARS-CoV-2 NP, respectively. While the LOD for all cases falls between 10 and 30 ng/mL, the LOD for Influenza A is significantly worse. This may be due to a lower affinity of the antibody employed for the specific viral NP, leading to lower detection signals and sensitivity.

No cross-reactivity was observed from the non-specific viral NPs for the range of concentrations measured. Only a slight recognition of Influenza A antigen at high concentrations (5000 ng/mL) was observed in the channel modified with anti-IBV (CH3, see Fig. S3C). This result could be attributed to the fact that Influenza A and B share a significant percentage of homology (at least 37%) in their nucleoprotein sequences42. Despite this cross-reactivity, the results remain unaffected, as the biosensor responses for the Influenza B nucleoprotein are still highly specific, as shown in Fig. S3A.

The results, along with the low cross-reactivity observed, support the biosensor’s capability to effectively identify, differentiate, and quantify viral antigens from four distinct respiratory viruses simultaneously.

Biosensor performance in nasopharyngeal samples

Effective detection in antigen-based assays relies on the prior release of viral nucleoproteins for capture by sensor surface-immobilized antibodies. Nasopharyngeal swabs are the standard sample type for diagnosing respiratory viruses, including those targeted here, and are typically processed in transport or lysis media depending on the downstream assay. Nasopharyngeal samples, retrospectively collected and stored in a viral preservation medium, were used to evaluate the performance of the multiplexed biosensor. Given that antigen release is required before detection, we assessed the impact of different lysis buffers —similar to those employed in commercial rapid antigen tests— on the biosensor response, as well as the influence of the sample matrix itself. Five samples from healthy individuals (nasopharyngeal swabs), preserved in saline solution, were treated with lysis buffer at ratios of 1:5 and 1:10 (one part buffer to five or ten parts sample) (see Fig. S4) for 30 minutes according to the manufacturer’s instructions and then evaluated with the biosensor. The biosensor response resulted in significant non-specific binding for both conditions (i.e., 0.47 ± 0.16 nm for 1:5 dilution and 0.96 ± 0.20 nm for the 1:10 dilution, average of four channels, as shown in Fig. S4), which would hinder the accurate detection in positive samples.

To mitigate the non-specific adsorptions, several strategies were evaluated, including the modification of the buffer composition, sample dilution, and filtration. Based on previous findings, the inclusion of surfactants such as Tween 20 has proven effective in reducing non-specific interactions and minimizing matrix effects during target recognition. Accordingly, 0.5% of Tween was added to the lysis buffer, resulting in a slight decrease of the background signal in both dilution ratios (Δλ1:5 = 0.53 ± 0.24 nm and Δλ1:10 = 0.69 ± 0.26 nm, Fig. S4). Further reduction was achieved by filtering the sample. Notably, 1:5 and 1:10 dilutions yielded a significant reduction of non-specific binding, with background signals of 0.21 ± 0.07 nm and 0.29 ± 0.07 nm, respectively. Ultimately, a 1:1 dilution provided a background signal of 0.008 ± 0.016 nm, confirming the effective elimination of non-specific adsorptions under these conditions.

According to these last conditions and the results obtained from negative samples, a cut-off value was established for all the biosensor assays. This threshold, set at a biosensor signal of Δλ > 0.059 nm, corresponds to three times the standard deviation of the mean signal from negative samples and was used to differentiate positive from negative responses for each virus.

To preliminarily assess the recovery efficiency under the optimized conditions, a nasopharyngeal swab sample diluted 1:1 with lysis buffer was spiked with 2.50 µg/mL of SARS-CoV-2 nucleoprotein and compared to the standard conditions (PBST). The biosensor response (Δλ = 2.33 nm) showed a signal similar to that obtained with buffer conditions (Δλ = 2.56 ± 0.43 nm) (see Fig. S4), confirming both the lack of nonspecific interactions and the retention of the specific recognition by the antibody immobilized on the sensor surface.

Under these conditions, the detection capabilities of each viral NP assay within the multiplexed biosensor were carried out by fortifying a pool of nasopharyngeal swab samples from healthy patients with known amounts of viral NP ranging from 150 ng/mL to 5 µg/mL. Figure 3 shows the analytical curves for viral nucleoproteins from Influenza B, RSV A and B, Influenza A, and SARS-CoV-2 in nasopharyngeal swabs diluted 1:1 with lysis buffer and filtered, respectively. The LODs achieved for each viral nucleoprotein are compiled in Table 1 and compared to those obtained under standard conditions. Slightly better sensitivities were obtained for Influenza B, RSV A, RSV B, and SARS-CoV-2, suggesting that some components of the lysis buffer create a more favorable environment for the antibody-antigen interactions. In contrast, the LOD for Influenza A worsened, but the cross-reactivity observed under buffer conditions in the channel containing anti-IBV was resolved, presumably due to the different composition of the media.

Chips are biofunctionalized as follows: CH1: anti-IBV; CH2: anti-RSV; CH3: anti-IAV; CH4: anti-COV. Individual NP solutions (ranging from 100 to 5000 ng/mL) were prepared and flowed across all the channels. Calibration curves for each specific target/channel are shown: A NP from Influenza B, B NP from RSV A (solid line) and B (dashed line (---)), C NP from Influenza A, D NP from SARS-CoV-2. The non-specific signals from the non-target nucleoproteins in each channel are also shown. Each data point represents the mean ± SD of duplicate measurements. The dotted line (···) indicates the zero value for reference.

The recovery of the sample processing and the performance of the multiplexed plasmonic biosensor were further evaluated with a set of blind spiked samples, employing nasopharyngeal swabs from healthy individuals with varying concentrations of the four viral NP. Eleven blind samples were prepared for which the concentrations and the pathogen were unknown to the researcher conducting the analysis. These samples simulated a unique respiratory virus infection involving one viral NP (S1 – S9) or a co-infection of two respiratory viruses, simultaneously measuring two viral NPs (S10 – S11). All samples were prepared to cover the working range of the immunoassay developed for each viral antigen (see Table 1). The biosensor responses from the four channels were monitored simultaneously in real-time (see Fig. S5), and the concentration in each sample was determined from the calibration curves (Fig. 3). The results obtained are summarized in Table 2. An excellent performance was observed in the identification of viral NP, even in those samples with multiple viruses. The multiplexed biosensor assay exhibited excellent specificity, with signal exclusively detected in the channels containing the corresponding target antibody (see Fig. S5). The quantification of viral antigens also showed a good correlation according to the concentration spiked into the sample. Most recovery values fell within the range of 80% to 120%, commonly accepted in many analytical processes. However, certain samples (S3, S4, S7, and S8) showed overestimations, with values ranging from 128.70% to 158.30%. This was the case of a couple of samples containing Influenza A, and a sample containing SARS-COV-2 close to the saturation concentration, or Influenza B, with values close to the limit of detection.

Novel disposable microfluidic cartridge for real sample analysis

We have made a significant step forward in deploying this methodology to decentralized laboratories by introducing a custom-made disposable microfluidic cartridge. This cartridge, measuring 50 × 28 mm, is specifically designed for single-use point-of-care applications and serves as an alternative to the PDMS microfluidics employed before. The cartridge is made from a combination of poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) and pressure-sensitive adhesive (PSA) substrates. It features four sensing areas (CH1, CH2, CH3, and CH4) arranged in a serpentine layout, in a single inlet-outlet configuration as illustrated in Fig. 1 and S1B. This design is compatible with both active (i.e., pumps) and passive (i.e., capillary action and pipetting) fluid flow methods.

The plasmonic sensor chips biofunctionalized with the four specific antibodies were assembled with the disposable cartridge and placed in the biosensor setup for the evaluation of the samples. To assess any significant variation in the performance related to the microfluidic design, different NP samples at several concentrations were prepared, and the biosensor result was compared with the one generated with the microfluidic PDMS-based flow cell. Both results were comparable in all cases (see Fig. S6). According to this, single-use microfluidic cartridges were employed to validate the multiplexed plasmonic biosensor with clinical samples.

Clinical validation of the multiplexed biosensor device

The multiplexed plasmonic biosensor with the disposable microfluidic cartridge has been validated with a clinical sample collection of 46 nasopharyngeal swab samples. This collection included 36 positive samples for one of the respiratory viruses (Influenza A/B, RSV A/B, or SARS-CoV-2) and 10 negative samples (see Table S1). All the samples were previously characterized by RT-PCR at the hospital reference laboratory and were evaluated using the multiplexed plasmonic biosensor and a commercial multiplexed lateral flow test (Tables S2 and S3).

Each clinical sample was evaluated in triplicate: twice using the PDMS flow cell and once using the disposable microfluidic cartridge (see Table S2). Figures S7 and S8 show representative responses for different samples measured with both microfluidic designs. Samples were considered positive or negative for a given virus according to the signal measured in each sensing channel and the established cut-off value. Figure 4 presents a heat map that summarizes the results obtained with the multiplexed plasmonic biosensor and the full sample collection, providing a visual representation of the biosensor specificity. Non-infected samples yield no positive signal in any channel, whereas infected samples produce a positive response exclusively in the channel functionalized with the antibody specific to the pathogen’s viral nucleoprotein. The color gradient correlates with the concentration of NP antigen determined in each case. The concentration of the NP varies among patients due to factors such as viral load, immune responses, and disease progression. As illustrated in Fig. 5, the concentrations range roughly between 100–500 ng/mL in the case of Influenza B and RSV, slightly lower for SARS-CoV-2, and significantly higher for Influenza A (with concentration around 1000–4000 ng/mL). Differences in patient viral loads are likely contributing to the observed variability. All negative samples fall below the established threshold, confirming an excellent specificity, while for all the positive samples except one, the causative viral pathogen is correctly identified. The sample positive for Influenza A (sample 101969897) identified as negative for all the viruses, presumably contained a low viral load according to the PCR data (i.e., high cycle threshold (Ct) = 33.44), consequently, low nucleoprotein concentration, likely below the biosensor LOD for Influenza A. This discrepancy was only observed with Influenza A, the biosensor with the worst limit of detection compared with the others (i.e., around one order of magnitude higher than the ones achieved with the other viruses). For the other respiratory viruses, we were able to accurately diagnose even in samples with very low viral loads, with Cts > 33, confirming that the biosensor responses for positive cases robustly enable both infection detection and pathogen identification. This is supported by the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test, which shows a highly significant difference (p-value < 0.0001) between positive and negative samples, whether positive cases are considered collectively or grouped by individual virus type. The developed antigen-based multiplexed plasmonic biosensor demonstrated excellent capabilities to diagnose respiratory viral infections caused by the four most common respiratory viruses, with a similar performance to PCR testing, even at low viral loads (i.e., high Cts), with a sensitivity of 97.22% (95% CI: 85.83–99.86%) and a specificity of 100% (95% CI: 91.24–100%). The diagnostic performance obtained by each viral infection is detailed in Table 3. Additionally, Table S4 compares the sensitivity, specificity, LOD, and time to results obtained in this study with the manufacturer-reported data from other commercially available multiplexed antigen tests.

The color gradient correlates with the biosensor signal and the antigen concentration (i.e., darker colors represent higher viral loads). The position of each antibody: CH1 – anti-IBV; CH2 – anti-RSV; CH3 – anti-IAV, and CH4 – anti-COV. For each sample (n = 46), the data represent the mean of triplicate measurements (twice using the PDMS flow cell and once using the disposable microfluidic cartridge).

To evaluate whether the concentrations of viral nucleoproteins measured by the multiplexed plasmonic biosensor correlate with RNA levels inferred from PCR Ct values (Table S3), we conducted a correlation analysis. Scatter plots for each viral infection, shown in Fig. S9, were generated to visualize the data distribution, showing a clear inverse correlation. The relationship between these two variables was analyzed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) to evaluate the strength and direction of their association. The results are detailed in Table 4 and demonstrate a statistically significant, strong negative linear relationship for all viral pathogens (r > −0.84 and p < 0.0042). This indicates that higher NP concentrations are associated with lower Ct values. The coefficient of determination (R²) supports this correlation, showing that 70.10% to 88.09% of the variance in NP concentration can be explained by changes in Ct values. These findings are consistent with the established interpretation of Ct values as inversely related to viral load —lower Ct values indicate higher RNA levels and, consequently, higher concentrations of viral nucleoproteins.

To comparatively assess its performance with other POC rapid testing, the set of clinical samples was also analyzed with a multiantigen lateral flow test that can identify SARS-CoV-2, Influenza A/B, and RSV. The RAT performed significantly worse than the biosensor device, as the sensitivity was globally much lower for the four viruses. Fifteen samples tested yielded false-negative (FN) results. Notably, all these FN samples had PCR Ct values greater than 28, indicating that the sensitivity of this RAT is insufficient for detecting moderate to low viral loads. Considering the whole sample collection (n = 46), the RAT test reports an overall sensitivity of 58.33% (95% CI: 42.20–72.86%) and a specificity of 100% (95% CI: 72.25–100%). However, the sensitivity of the RAT varies depending on the virus, ranging from 50 to 71.42%, as detailed in Table 3. Our findings are consistent with those described in the literature, where different studies have analyzed a large number of clinical samples19,20,21, but are in disagreement with the ones provided by the manufacturer. As shown in Table S3, the multiplexed plasmonic biosensor provides diagnostic performance comparable to PCR and superior sensitivity and specificity to antigen-based methods such as lateral flow rapid tests, across the tested sample set.

Discussion

There is a growing need for new diagnostic tools capable of identifying pathogenic infections in a simpler, faster, and more reliable manner, particularly in decentralized settings. This is particularly important for respiratory viruses such as SARS-CoV-2, Influenza A and B, and RSV, as their seasonal outbreaks and clinical manifestations often overlap. Accordingly, we have developed a user-friendly point-of-care multiplexed plasmonic biosensor capable of the simultaneous detection of multiple viral targets. The biosensor device allows for the rapid identification, discrimination, and quantification of viral antigens for the four most prominent viral pathogens (SARS-CoV-2, Influenza A and B, and RSV) in nasopharyngeal swabs. Our strategy enables the simultaneous, direct, and label-free detection of four viral nucleoproteins by immobilizing a specific antibody in each of the four dedicated sensing areas. Nucleoprotein was selected as the target antigen due to its presence in all RNA viruses, its high abundance, and its strong sequence conservation. This selection minimizes the impact of viral mutations, supporting the development of broadly applicable diagnostic assays.

An in-depth optimization has been performed on several parameters directly influencing the biosensor performance, focusing on minimizing the potential cross-reactivity among the different viral NPs to ensure accurate discrimination, and reducing non-specific adsorptions from nasopharyngeal swab samples that could hinder viral NP identification. Additionally, we have addressed the final validation of the biosensor by analyzing clinical samples from hospital patients, starting with the minimal sample treatment required to release NPs from viral particles and, subsequently, assessing its impact on the biosensor assay performance. The LODs achieved for each viral nucleoprotein were 32.03 ng/mL for Influenza B, 12.03 ng/mL for RSV A, 13.68 ng/mL for RSV B, 148.93 ng/mL for Influenza A, and 6.90 ng/mL for SARS-CoV-2 in diluted nasopharyngeal swabs, respectively.

The biosensor methodology has been validated with 46 clinical samples from infected and non-infected patients and has provided a successful identification and quantification of the presence of SARS-CoV-2, Influenza A and B, and RSV viruses, even in samples with low viral loads (i.e., high Ct values from PCR testing). The entire biosensor assay time included 30 minutes for lysis and 20 – 40 minutes for capture. The results showed an excellent correlation with those obtained with the gold standard method based on nucleic acid amplification. Furthermore, it outperforms established diagnostic techniques based on similar strategies for the detection of viral antigens, such as rapid antigen tests, which have moderate to low sensitivity depending on the viral infection when the Ct values exceed 28, indicating a low viral load. In contrast, the multiplexed plasmonic biosensor demonstrated a sensitivity of 97.22% (95% CI: 85.83−99.86%) and a specificity of 100% (95% CI: 91.24−100%). The developed biosensor can diagnose viral infections caused by the most common respiratory viruses with the same reliability as PCR tests. Moreover, a statistically significant correlation was observed between the biosensor response (Δλ) and the Ct values for all viral pathogens, reflecting the expected inverse relationship, where higher NPs abundance corresponds to lower Ct values. This finding emphasized the biosensor ability to quantify viral antigens without requiring complex RNA extraction protocols, demonstrating a quantitative advantage over rapid antigen tests.

Leveraging the excellent performance of the biosensor platform, we have made important advancements by adapting the methodology for decentralized, real-world applications. Specifically, we have designed and integrated biofunctionalized chips into single-use microfluidic cartridges for the first time, achieving performance comparable to that of conventional PDMS flow cells, restricted to laboratory settings. This advancement enables cost-effective large-scale production of microfluidic cartridges, supporting their use as single-use disposable consumables. The proposed biosensor platform advances towards improved usability and accessibility for non-specialized users and competes with RATs and even PCR-based molecular tests in cost, simplicity, analysis time, and deployability.

Our work provides the clinical validation of a multiplexed plasmonic biosensor designed for the simultaneous detection of four viral antigens in over 40 nasopharyngeal swab samples. Previous reported studies of plasmonic biosensing for respiratory infections rely on the detection of active infection of a single antigen, mainly the SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein, and analyzed samples ranging from 2 to 23 nasopharyngeal swab29,31,43. However, the small sample size did not allow for a detailed assessment of the diagnostic performance of the biosensors. Instead, the developments have been primarily focused on serological immunoassays, for example, for COVID studies, to identify up to three SARS-CoV-2-associated antibodies44,45, for the parallel processing of multiple samples44, or to profile antibody responses against multiple SARS-CoV-2 variants in combination with machine learning tools46. Focusing only on SARS-CoV-2, another study conceptualized the detection of ten biomarkers (six viral genes, two Spike subunits, two antibodies) in a single test. However, this high-throughput approach based on 96-well microplates only validated multiplexing for distinguishing IgG/IgM antibodies in real plasma samples47. The multiplexing capabilities of plasmonic devices for identifying respiratory viruses have been rarely explored, with reports limited to detecting viral genes from nine viruses, although via the detection of amplified PCR products48 or to the detection of isolated virions from SARS-CoV-2, Zika virus, and Norovirus49. Nevertheless, clinical validation remains limited with only the demonstration of the analytical performance in standardized conditions.

While our study demonstrates promising results, several aspects require further investigation before our findings can be integrated into clinical workflows. First, the sample size must be expanded through larger clinical studies to fully assess the diagnostic potential of the multiplexed plasmonic biosensor, especially in comparison to existing tests. Such expansion is crucial for regulatory compliance with in vitro diagnostic standards. Additionally, although not within the scope of the present study, the potential cross-reactivity of the developed immunoassays with other pathogens, as well as their performance with different virus variants, could be further explored in future studies. Overall, the results obtained position our multiplexed plasmonic biosensor as an accurate and robust tool for the simultaneous, rapid, and reliable identification, discrimination, and quantification of viral loads for four major viral pathogens: SARS-CoV-2, Influenza A and B, and RSV, using nasopharyngeal swabs. One of the key advantages of this biosensor is its versatility. Our design features independent, exchangeable, disposable, and ready-to-use biofunctionalized chips, allowing this technology to be applied to a variety of diagnostics, including viruses, bacteria, allergies, cancer, and more.

Methods

Chemical and biological reagents

Organic solvents, including acetone, ethanol, and absolute ethanol, were purchased from Panreac (Barcelona, Spain). Alkanethiols HS-C11-(EG)6-OCH2-COOH and HS-C11-EG4-carboxybetaine were supplied by ProChimia Surfaces (Gdynia, Poland). Reagents for carboxylic acid activation (N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N’-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC) and N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide (sulfo-NHS)) were obtained from TCI Europe N. V. (Zwijndrecht, Belgium). Tween 20, dextran sulfate sodium salt (DS, Mr ~ 40,000), sodium hydroxide (NaOH), ethanolamine hydrochloride (EA), 2-(N-morpholino) ethanesulfonic acid (MES), along with all reagents used for buffer preparation, were provided by Sigma-Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany). The viral lysis buffer, which contains Tween 20, ProClin-300, and other components in Tris buffer (pH 7.5), was purchased from ACROBiosystems AG (Basel, Switzerland).

Monoclonal IgG antibodies (mAb) against Influenza A (anti-IAV) and B (anti-IBV) nucleoproteins were acquired from HyTest (Turku, Finland). According to the manufacturer’s data, the anti-IAV can detect more than 25 distinct influenza A variants, including the most relevant circulating subtypes H1N1 and H3N2. Similarly, Anti-IBV has been tested against 6 common strains, showing high specificity for all of them and no cross-reactivity with influenza A viruses, RSV, or other respiratory viruses. Monoclonal IgG antibody against RSV A and B nucleoproteins (anti-RSV) was obtained from Abbexa Ltd (Cambridge, UK). A monoclonal IgG against SARS-CoV-2 nucleoprotein (anti-COV) was obtained from GenScript (Rijswijk, Netherlands). Specific viral nucleoproteins from Influenza A (strain: A/Wisconsin/67/2022 (H1N1)), Influenza B (strain: B/Austria/1359417/2021), RSV A (strain: A2), and RSV B (strain: 18537) were provided by Sino Biological Europe GmbH (Eschborn, Germany). The SARS-CoV-2 nucleoprotein was acquired from ACROBiosystems AG (Basel, Switzerland). The buffers used included the following: PBS (10 mM phosphate buffer saline, 2.7 mM KCl, 137 mM NaCl, pH 7.4), PBST (PBS with 0.05% Tween 20, pH 7.4), PBST-DS (PBST with 0.5 mg/mL DS, pH 7.4), MES 0.1 M (pH 5.5), EA (1 M, pH 8.5), MES 50 mM (pH 5.5), and acetate buffer (10 mM, pH 4.5 and 5.0). Milli-Q water was always employed.

Clinical samples

Clinical samples (n = 46) were collected at Vall d’Hebron University Hospital (Spain) from patients with suspicion of acute respiratory infection. The viral diagnosis was performed by commercial real-time RT-PCR-based methods (Allplex respiratory panels 1A-3, Seegene, Korea; and Xpert® Xpress CoV-2/Flu/RSV, Cepheid, US). After testing, samples were stored at -80°C for further studies or molecular characterization. Institutional Review Board approval (PR(AG)144/2025) was obtained from the Vall d’Hebron University Hospital Clinical Research Ethics Committee.

Multichannel plasmonic biosensor device

The multichannel plasmonic device is integrated into a compact platform (20 × 20 cm) and allows the simultaneous detection of 4 sensing areas (i.e., sensing channels) in real-time. The device operates under the Kretschmann configuration at a fixed angle of incidence (θ = 70°). Plasmonic sensor chips (1 nm titanium and 49 nm gold; 22 ×22 mm) are employed and incorporated into flow cell or disposable cartridges for adequate sample delivery (see Fig. S1). When a polarized light passes through the prism, it generates an evanescent field at the sensor surface, which is highly sensitive to changes in refractive index. The reflected light is then collected and fiber-coupled to a CCD spectrometer (Flame series, Ocean Optics, US). For active pumping, a syringe pump is connected to a 6-port injection valve with a 500 μL loop. The microfluidics clamped to the biosensor chip is on a linear stage, which includes a motorized actuator connected to a stepper motor (K-Cube Brushed DC Servo Motor Controller, Thorlabs, US) that allows precise positioning along the channels defined by the microfluidics. The PDMS-based microfluidics flow cell includes a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) layer that defines four sensing areas (i.e., four flow channels, CH1, CH2, CH3, and CH4) and an external polymeric cover to facilitate the delivery of liquid solutions. The design is based on a 1:4 (inlet:outlet) configuration through symmetric splitting of the channels (see Fig. S1A). The distance between adjacent channels is 4000 μm. The four outlets are connected to flow restrictors to ensure constant and homogenous flow rates among the four channels. The disposable cartridge distributes the liquid sequentially in a serpentine configuration (see Fig. 1 and S1B) and can be adapted for sample injection through active pumping or passive delivery (i.e., with pipettes). Dedicated custom readout software (LabView, National Instruments, US) has been designed to track the plasmonic spectra and plot the position of the minimum of the plasmon resonance spectra (λSPR) in real-time for the four channels (i.e., biosensor response as wavelength displacement (Δλ, nm)) and to control the motorized stage to move sequentially among the channels and perform the corresponding data acquisition. The reflectivity spectra are acquired every 1 ms and 300 consecutive spectra for each channel. The position of the λSPR can be monitored in real-time via polynomial fit using the readout software and shifts λ1, λ2, λ3, and λ4. (Bio)chemical interactions occurring at the gold surface generate variations of the local refractive index (n1 to n2), which correlates with the minimum wavelength displacements (Δλ). λSPR is directly related to mass changes resulting from binding events (higher RI, positive wavelength shift) or desorption events (lower RI, negative wavelength shift) occurring on the gold surface. The software displays the average spectrum for each channel only after completing the acquisition and processing of all four channels, which takes approximately 20 seconds. The multiplexed plasmonic biosensor exhibits a bulk refractive index sensitivity of 3490 nm/RIU and a system noise of 0.00343 ± 0.00045 nm across the four sensing channels, resulting in a LOD of 3 × 10−6 RIU. The plasmonic spectra consistently display a reflectivity minimum at λSPR = 685 nm for all channels, with a calculated full width at half maximum (FWHM) of 53.08 ± 0.27 nm37.

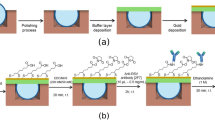

Plasmonic sensor chip functionalization

Plasmonic sensor chips were thoroughly cleaned using heated sonication at 80 °C for 1 minute in the following solvents: acetone, ethanol, and milli-Q water. Then, the sensor chips were dried with an N2 stream and placed inside a UV/Ozone ProCleaner Plus (BioForce Nanosciences, US) for 25 min. Subsequently, the sensor chips were rinsed with ethanol and dried using a N2 flow. Following the cleaning procedure, the plasmonic sensor chips were chemically modified by forming a mixed self-assembled monolayer (SAM) using a solution containing HS-C11-(EG)6-OCH2-COOH and HS-C11-EG4-Carboxybetaine in a 7:3 ratio, at a final concentration of 1 mM in absolute ethanol. The SAM formation was achieved by immersing the chips in the ethanolic thiol solution and heating them at 40 °C for 10 minutes. Finally, the sensor chips were incubated overnight at room temperature.

Ex-situ immobilization of different antibodies against viral nucleoproteins

The multi-antibody biofunctionalization of the sensor chips was carried out using a custom-designed incubation chamber, which allows separate modification of the 4 sensing channels37. The layout was maintained throughout all the experiments as follows (see Fig. 1): CH1 = anti-IBV (mAb Influenza B); CH2 = anti-RSV (mAb RSV A/B); CH3 = anti-IAV (mAb Influenza A); CH4 = mAb SARS-CoV-2. The covalent coupling of the antibodies was achieved through carbodiimide chemistry. Briefly, the SAM-modified chips were incubated with a solution containing 0.2 M EDC/0.05 M sulfo-NHS in MES 0.1 M (pH 5.5) for 40 min to activate the carboxyl groups. After this step, the sensor chip was placed into the incubation chamber for overnight incubation at 4°C with the different antibodies (20 µg/mL, 50 µL in each compartment in their optimal immobilization buffer: anti-IBV and anti-RSV in acetate 10 mM (pH 5.0), anti-IAV in acetate 10 mM (pH 4.5), and anti-COV in MES 50 mM (pH 5.5)). Finally, an EA solution was added and incubated for 2 minutes. The sensor chip was rinsed with Milli-Q water between each step and dried with a stream of N2. After removing the chip from the incubation chamber, the biofunctionalized chip was positioned in the optical device, clamped with the PDMS flow cell (Fig. S1A), or placed in a disposable microfluidic cartridge (Fig. 1 and S1B) for virus detection.

Nucleoprotein detection assay

The detection of each viral nucleoprotein was performed over antibody-coated plasmonic chips by direct capture. Individual solutions of each viral NP (Influenza A/B, RSV A/B, and SARS-CoV-2) were injected over the biofunctionalized sensor surface, with PBST-DS as running buffer at a constant flow rate of 20 μL/min in each channel. Calibration curves were obtained by analyzing different NP concentrations (between 150 ng/mL and 5 μg/mL) in duplicate in PBST or nasopharyngeal swab:lysis buffer (1:1). A NaOH 20 mM solution was employed to completely dissociate the antibody-antigen interaction. Antibody-coated plasmonic sensor chips could be reused up to 12 times if needed without altering or modifying the immobilized antibodies and the assay performance.

Recovery study with blind samples

To assess the accuracy of the biosensor assay, eleven spiked samples (S1−S11) were prepared by a different researcher, creating blind samples for the analyst. These samples were made by spiking nasopharyngeal swabs in saline solution with known concentrations of viral NP. Both single and mixed samples of different viral NP were diluted (1:1) in lysis buffer (with 0.5% Tween 20), incubated for 30 min, and then filtered using syringe filters (0.22 µm). The concentrations of the samples were determined by interpolating from the calibration curves generated in the lysis buffer (1:1). Recovery was determined by applying the following equation:

Analysis of clinical nasopharyngeal swab

Stored clinical samples were diluted in lysis buffer (1:1) and sonicated for 30 min. Then, the viral lysate was filtered with syringe filters (0.22 µm) and injected over the antibody-coated plasmonic chips. All these experiments were carried out in the ICN2 BSL2 facilities. A commercial RAT Fluorecare (Shenzhen Microprofit Biotech Co., China) for the qualitative detection of SARS-CoV-2, Influenza A/B, and RSV was employed for a comparative study. RATs were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, nasopharyngeal swabs were mixed with lysis buffer (1:1) and incubated for 1 min before being added to the corresponding loading area on the test cassettes. After 15 min, the results were reflected by the appearance of colored bands. The RAT results were classified as positive or negative based on whether a line appeared for the tested virus.

Data analysis

All data were analyzed using Origin 2018 (OriginLab, US) and GraphPad Prism 10 (GraphPad Software, US). The biosensor response (i.e., wavelength shift (Δλ, nm)) was considered after signal stabilization once all the samples had completely passed through the sensor chip. Calibration curves were obtained by evaluating various concentrations of each viral NP, with results presented as the mean and standard deviation (mean ± SD) of the sensor signal (Δλ) plotted against the corresponding NP concentration. The data were fitted using a non-linear regression equation (one site-specific binding). From the calibration curve, the limit of detection (LOD) for each viral NP was calculated as the concentration corresponding to three times the standard deviation of the blank. Threshold values (cut-off) to define positive samples were calculated from the mean + 3 SD of negative control samples. A value < 0.9Mean + 3 SD was considered negative (<0.058 nm); a value > 1.1Mean + 3 SD was considered positive (>0.059 nm), and a value between (0.9–1.1)Mean + 3 SD was considered indeterminate. The differences between the groups were analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis test. The correlation between nucleoprotein concentrations measured with the multiplexed biosensor and Ct values obtained from the PCR test were assessed using a Pearson correlation test. In both cases, a p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Diagnostic sensitivity and specificity

Sensitivity (SE) and specificity (SP) were obtained from the number of false positives (FP), false negatives (FN), true positives (TP), and true negatives (TN).

PCR Positive | PCR Negative | |

|---|---|---|

Biosensor Test Positive | TP | FP |

Biosensor Test Negative | FN | TN |

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files. Raw data files are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Bloom, D. E. & Cadarette, D. Infectious disease threats in the twenty-first century: strengthening the global response. Front. Immunol. 10, 549 (2019).

Baker, R. E. et al. Infectious disease in an era of global change. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 20, 193–205 (2022).

Leung, N. H. L. Transmissibility and transmission of respiratory viruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 19, 528–545 (2021).

Borchers, A. T., Chang, C., Gershwin, M. E. & Gershwin, L. J. Respiratory Syncytial Virus—A Comprehensive Review. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 45, 331–379 (2013).

Cascella, M., Rajnik, M., Aleem, A., Dulebohn, S. C. & Di Napoli, R. Features, Evaluation, and Treatment of Coronavirus (COVID-19). in StatPearls (StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL), 2025).

Lessani, M. N. et al. Human mobility and the infectious disease transmission: a systematic review. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 27, 1824–1851 (2024).

Del Riccio, M. et al. Global analysis of respiratory viral circulation and timing of epidemics in the pre–COVID-19 and COVID-19 pandemic eras, based on data from the Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System (GISRS). Int. J. Infect. Dis. 144, 107052 (2024).

Wang, S. et al. Emerging and reemerging infectious diseases: global trends and new strategies for their prevention and control. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 9, 223 (2024).

Krammer, F. et al. Influenza. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 4, 3 (2018).

Lewinski, M. A. et al. Exploring the Utility of Multiplex Infectious Disease Panel Testing for Diagnosis of Infection in Different Body Sites. J. Mol. Diagn. 25, 857–875 (2023).

Luštrek, M. et al. Influenza A, Influenza B, human respiratory syncytial virus and SARSCoV-2 molecular diagnostics and epidemiology in the post COVID-19 era. Respir. Res. 25, 234 (2024).

Harsh & Tripathi, P. Medical viruses: diagnostic techniques. Virol. J. 20, 143 (2023).

Mackay, I. M. Real-time PCR in virology. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 1292–1305 (2002).

Watzinger, F., Ebner, K. & Lion, T. Detection and monitoring of virus infections by real-time PCR. Mol. Asp. Med. 27, 254–298 (2006).

Chan, W.-S. et al. Clinical Evaluation of Xpert Xpress CoV-2/Flu/RSV plus and Alinity m Resp-4-Plex Assay. Diagnostics 14, 683 (2024).

Noble, L. D. et al. Rapid Evaluation of the Xpert® Xpress CoV-2 plus and Xpert® Xpress CoV-2/Flu/RSV plus Tests. Diagnostics 13, 34 (2022).

Cassidy, H., Van Genne, M., Lizarazo-Forero, E., Niesters, H. G. M. & Gard, L. Evaluation of the QIAstat-Dx RP2.0 and the BioFire FilmArray RP2.1 for the Rapid Detection of Respiratory Pathogens Including SARS-CoV-2. Front. Microbiol. 13, 854209 (2022).

Leber, A. L. et al. Multicenter Evaluation of BioFire FilmArray Respiratory Panel 2 for Detection of Viruses and Bacteria in Nasopharyngeal Swab Samples. J. Clin. Microbiol. 56, e01945–17 (2018).

Savolainen, L. E. et al. Clinical performance of two commercially available rapid antigen tests for influenza, RSV, and SARS-CoV-2 diagnostics. Microbiol. Spectr. 13, e01630–24 (2025).

Murphy, C. et al. Diagnostic performance of multiplex lateral flow tests in ambulatory patients with acute respiratory illness. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 110, 116421 (2024).

Bayart, J.-L. et al. Clinical performance evaluation of the Fluorecare® SARS-CoV-2 & Influenza A/B & RSV rapid antigen combo test in symptomatic individuals. J. Clin. Virol. 161, 105419 (2023).

Monteil, S., Casson, A. J. & Jones, S. T. Electronic and electrochemical viral detection for point-of-care use: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 16, e0258002 (2021).

Manring, N., Ahmed, M. M. N., Tenhoff, N., Smeltz, J. L. & Pathirathna, P. Recent Advances in Electrochemical Tools for Virus Detection. Anal. Chem. 94, 7149–7157 (2022).

Ramirez-Priego, P., Mauriz, E., Giarola, J. F. & Lechuga, L. M. Overcoming challenges in plasmonic biosensors deployment for clinical and biomedical applications: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Bio-Sens. Res. 46, 100717 (2024).

Park, H. & Jackman, J. A. Nanoplasmonic biosensors for detecting viruses and combating viral infections. npj Biosens. 2, 22 (2025).

Sharma, A. et al. Optical biosensors for diagnostics of infectious viral disease: a recent update. Diagnostics 11, 2083 (2021).

Soler, M., Estevez, M. C., Cardenosa-Rubio, M., Astua, A. & Lechuga, L. M. How nanophotonic label-free biosensors can contribute to rapid and massive diagnostics of respiratory virus infections: COVID-19 Case. ACS Sens 5, 2663–2678 (2020).

Ribeiro, B. V. et al. Biosensors for the detection of respiratory viruses: A review. Talanta 2, 100007 (2020).

Chen, L.-C. et al. Facile and unplugged surface plasmon resonance biosensor with nir-emitting perovskite nanocomposites for fast detection of SARS-CoV-2. Anal. Chem. 95, 7186–7194 (2023).

Saada, H. et al. Sensing of COVID-19 spike protein in nasopharyngeal samples using a portable surface plasmon resonance diagnostic system. Sens. Diagn. 1, 1021–1031 (2022).

Gumilar, G. et al. Rapid and label-free screening of SARS-CoV-2 virus in the infected human nasopharyngeal swab samples using UiO-66-modified SPR chip. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 127, 467–475 (2023).

Zheng, Y., Song, X., Fredj, Z., Bian, S. & Sawan, M. Challenges and perspectives of multi-virus biosensing techniques: A review. Anal. Chim. Acta 1244, 340860 (2023).

Peláez, E. C. et al. A compact SPR biosensor device for the rapid and efficient monitoring of gluten-free diet directly in human urine. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 412, 6407–6417 (2020).

Peláez, E. C. et al. Detection and quantification of hspx antigen in sputum samples using plasmonic biosensing: toward a real Point-of-Care (POC) for Tuberculosis Diagnosis. ACS Infect. Dis. 6, 1110–1120 (2020).

Calvo-Lozano, O. et al. Label-free plasmonic biosensor for rapid, quantitative, and highly sensitive COVID-19 serology: implementation and clinical validation. Anal. Chem. 94, 975–984 (2022).

Giarola, J. F. et al. An α-helical peptide-based plasmonic biosensor for highly specific detection of α-synuclein toxic oligomers. Anal. Chim. Acta 1304, 342559 (2024).

Giarola, J. F., Ramirez-Priego, P., Estevez, M. C. & Lechuga, L. M. Compact Multichannel Plasmonic Device for Rapid and Versatile Inflammatory Biomarker Analysis. Adv. Sens. Res. 4, e00050 (2025).

López-Muñoz, A. D. & Yewdell, J. W. Cell surface RNA virus nucleocapsid proteins: a viral strategy for immunosuppression? npj. Viruses 2, 41 (2024).

Šantak, M. & Matić, Z. The Role of Nucleoprotein in Immunity to Human Negative-Stranded RNA Viruses—Not Just Another Brick in the Viral Nucleocapsid. Viruses 14, 521 (2022).

Peláez, E. C. et al. Nanoplasmonic biosensor device for the monitoring of acenocoumarol therapeutic drug in plasma. Biosens. Bioelectron. 119, 149–155 (2018).

Giarola, J. F. et al. Validation of a plasmonic-based serology biosensor for veterinary diagnosis of COVID-19 in domestic animals. Talanta 271, 125685 (2024).

Londo, D. R., Davis, A. R. & Nayak, D. P. Complete nucleotide sequence of the nucleoprotein gene of influenza B virus. J. Virol. 47, 642–648 (1983).

Cennamo, N. et al. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein detection through a plasmonic D-shaped plastic optical fiber aptasensor. Talanta 233, 122532 (2021).

Djaileb, A. et al. Cross-validation of ELISA and a portable surface plasmon resonance instrument for IgG antibody serology with SARS-CoV-2 positive individuals. Analyst 146, 4905–4917 (2021).

Adi, W., Biswas, D., Shelef, M. A. & Yesilkoy, F. Multiplexed COVID-19 antibody quantification from human sera using label-free nanoplasmonic biosensors. Biomed. Opt. Express 13, 2130–2143 (2022).

Beisenova, A. et al. Machine-learning-aided multiplexed nanoplasmonic biosensor for COVID-19 population immunity profiling. Sens. Diagn. 2, 1186–1198 (2023).

Masterson, A. N. et al. Multiplexed and High-Throughput Label-Free Detection of RNA/Spike Protein/IgG/IgM Biomarkers of SARS-CoV-2 Infection Utilizing Nanoplasmonic Biosensors. Anal. Chem. 93, 8754–8763 (2021).

Shi, L. et al. Development of SPR biosensor for simultaneous detection of multiplex respiratory viruses. Bio-Med. Mater. Eng. 26, S2207–S2216 (2015).

Wallace, S. et al. Multiplexed biosensing of proteins and virions with disposable plasmonic assays. ACS Sens 8, 3338–3348 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the financial support received through the PROXIM project (2021 PROD 00191) from the Departament de Recerca i Universitats de la Generalitat de Catalunya through the Industria del Coneixement programme. The ICN2 is funded by the CERCA programme / Generalitat de Catalunya. The ICN2 is supported by the Severo Ochoa Centres of Excellence programme, Grant CEX2021-001214-S, funded by MCIU/AEI/10.13039.501100011033. The NanoB2A group is a consolidated research group (Grup de Recerca) of the Generalitat de Catalunya and has support from the Departament de Recerca i Universitats de la Generalitat de Catalunya (Expedient: 2021 SGR 00456). We also acknowledge Consorcio Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red - (CIBERINFEC, ISCIII - CIBER de Enfermedades Infecciosas), Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación and Unión Europea – NextGenerationEU.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.C.E. and L.M.L. conceptualized the project; M.C.E. supervised the project; M.C.E. and P.R.P. designed the experiments. P.R.P. and J.F.G. performed the experiments and data analysis and processing; C.A.V. and A.A.P. collected and selected the clinical samples and provided guidance on the samples; P.R.P. and M.C.E. wrote the manuscript. All authors read, edited, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Laura M. Lechuga is an Editorial Board member of the npj Biosensing journal. All authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ramirez-Priego, P., Giarola, J.F., Andrés, C. et al. Disposable Point of Care multiplexed plasmonic biosensor for rapid and specific identification of respiratory viruses. npj Biosensing 3, 4 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44328-025-00071-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44328-025-00071-w