Abstract

Artificial intelligence (AI) shows promising results for improving early breast cancer detection and overall screening outcomes, particularly in European studies. Breast cancer screening in the USA is unique owing to its technology (digital breast tomosynthesis), single-reading paradigm, annual cadence and diverse population, including increased risk groups. Therefore, evaluating AI workflows for scalable and equitable impact is needed. Here the AI-Supported Safeguard Review Evaluation (ASSURE) study evaluates an AI workflow on digital breast tomosynthesis exams from women across four states to optimize early cancer detection. This workflow integrated an AI-based computer-aided detection and diagnosis tool with an AI-driven safeguard review, where at-risk cases received additional review by a breast imaging radiologist. Comparing the AI-driven workflow (N = 208,891) with the prior standard of care (N = 370,692) resulted in a +21.6% increase in cancer detection rate (CDR; 5.6 versus 4.6 per 1,000), +5.7% recall rate (RR; 11.1% versus 10.6%) and +15.0% positive predictive value (PPV1; 5.0% versus 4.4%). The CDR increased between 20.4% and 22.7%, and no CDR, RR or PPV1 disparities were found across racial and density subpopulations with the AI workflow. Implementation of the AI workflow improved screening effectiveness with equitable benefits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer worldwide, representing a major public health challenge1. Population-based mammography screening has proven to be the most effective way to detect breast cancer early and reduce mortality2,3. Yet disparities in patient outcomes persist—women with dense breast tissue that can mask cancer lesions in mammograms face higher cancer risk and greater likelihood of missed cancer diagnoses; and Black women in the USA experience significantly higher breast cancer mortality, despite a lower incidence compared with white women. This racial disparity is linked to not only differences in tumour biology but also systemic barriers that result in reduced access, follow-up and delayed diagnoses for Black women4. Differences in outcomes based on race and breast density have led the US Preventive Services Task Force to call for more inclusive and effective screening strategies for these increased risk groups. Artificial intelligence (AI) has shown strong potential to improve screening outcomes including increases to the cancer detection rate (CDR) with no increase or a decrease in the recall rate (RR)5,6,7,8,9,10, and positive indications of improved outcomes generalizing to limited subpopulations11. However, such large-scale evaluations have exclusively been conducted in European settings with bi- or tri-ennial population-based invitations to screening and double reading9,10 of full-field digital mammography. This paradigm substantially differs from US practice with annual, opportunistic screening and single-reading workflows with digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT).

With the USA representing one of the largest and most diverse screening populations, and performing approximately 40% of worldwide screening mammograms each year12,13, this study, called AI-Supported Safeguard Review Evaluation (ASSURE), addresses an important evidence gap. We evaluate the real-world deployment and clinical use of a validated14 DBT-compatible AI-driven workflow, tailored for single-reading paradigms, at scale for over half a million women across 109 sites. Clinical outcomes were stratified by breast density and racial subgroups to assess whether outcomes were equitable across groups at increased risk of their cancer being missed (for example, women with dense breasts) or at increased risk of poor cancer outcomes (for example, Black women).

Results

Real-world deployment of the multistage AI-driven workflow was conducted at 5 practices across the USA (109 sites, 96 radiologists) in a diverse, nationally distributed (California, Delaware, Maryland and New York) outpatient imaging setting. The multistage AI-driven workflow aids the radiologist at two points in the workflow (Fig. 1a). First by interpreting the mammogram with a computer-aided detection and diagnosis (CADe/x) device (DeepHealth Breast AI version 2.x) and second by an AI-supported safeguard review (SafeGuard Review). The CADe/x device provides an overall four-level category (minimal, low, intermediate and high) of suspicion for cancer and localized bounding boxes for suspicious lesions14. The SafeGuard Review routes exams above a predetermined DeepHealth Breast AI threshold that were not recalled by the interpreting radiologist for review by a breast imaging specialist (reviewer). Reviewers were selected by the breast imaging practice leadership based on experience and clinical performance record. If the reviewer agreed with the AI and found the exam suspicious, they provided feedback on the exam to the interpreting radiologist, who made the final recall decision. The standard-of-care workflow consisted of single reading of DBT exams without the use of the multistage AI-driven workflow.

a, During the standard-of-care period, patients followed a typical screening workflow; during the multistage AI-driven workflow period, a CADe/x device (DeepHealth Breast AI) was added for the initial reader and, if routed by SafeGuard Review, a safeguard review was performed by a breast imaging specialist to detect possible missed cancers. b, Times during which exams were collected during the standard-of-care and multistage AI-driven workflow periods. BCSC, Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium.

Data from the multistage AI-driven workflow was included from 3 August 2022 to 31 December 2022 after a 2-month training period, and compared with a standard-of-care cohort before deployment, from 1 September 2021 to 19 May 2022 (Fig. 1b). In both cohorts, radiologists had access to non-AI-based computer-aided detection outputs. A prospective consecutive case series study design was selected for this investigation for two reasons: (1) to capture the real-world impact of the device when used for routine reading in a clinical setting; and (2) a double-blind randomized control trial was not possible as the reading radiologists could not use the device while blinded.

The primary outcomes of the ASSURE study were unadjusted CDRs, RRs and positive predictive value of recalls (PPV1) before and after deployment of the multistage AI-driven workflow for the overall screening population, and prespecified subpopulations of women with dense breasts and Black, non-Hispanic women. Secondarily, unadjusted and adjusted CDR, RR and PPV1 were investigated before and after AI deployment for the whole population and all subpopulations. Adjusted analyses utilized generalized linear models with generalized estimating equations controlling for race and ethnicity, breast density, and age, as well as grouping by interpreting radiologist as performed in previous studies15,16,17. The study was powered to detect a change in the CDR and in PPV1 in the whole population and to detect a change in the CDR in all prespecified racial and ethnic and density subpopulations of interest.

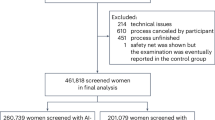

Patient characteristics

This study included 579,583 exams: 370,692 (64%) in standard of care and 208,891 (36%) in the multistage AI-driven workflow. Exams were included only if they were bilateral, DBT, and were from an eligible manufacturer. A flow chart of exam exclusions based on study and product exclusion and inclusion criteria is shown in Fig. 2. The same exclusion criteria were applied to both cohorts despite the AI algorithm not processing the standard-of-care cohort exams. Only a small number of DBT exams did not meet the device inclusion criteria (standard of care, 6,772 (1.5%); multistage AI-driven workflow, 2,678 (1.1%)). Population demographics, including patient age, race and ethnicity, and breast density, were similar between the cohorts (Table 1). Out of the 208,891 exams that went through the multistage AI-driven workflow, 16,763 underwent an additional safeguard review (8.0% of all exams). Zero adverse events were reported during the study period. Practice specific clinical performance and differences in demographics between practices are presented in Supplementary Tables 4 and 5, respectively.

Exam excl., exam exclusion criteria; Pt. excl., patient exclusion criteria; Rad. excl., radiologist exclusion criteria. Exclusion because an exam was not or would not be accepted by DeepHealth Breast AI included product-level requirements (see Supplementary Note 1 for more detail).

Screening performance of the multistage AI-driven workflow

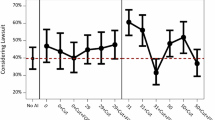

In the whole population, compared with the standard of care, the multistage AI-driven workflow cohort was associated with an absolute increase in the CDR (Δ0.99 cancers per 1,000 exams = 21.6%, 95% confidence interval (CI) 12.9–31.0%, P < 0.001), RR (Δ0.60 recalls per 100 exams = 5.7%, 95% CI 4.1–7.3%, P < 0.001) and PPV1 (Δ0.66 cancers per 100 recalls = 15.0%, 95% CI 7.0–23.7%, P < 0.001) (Fig. 3 and Table 2). All prespecified subpopulations had a higher CDR (Δ0.73–1.23 cancers per 1,000 exams = 20.4–22.7%, P ≤ 0.045) associated with the multistage AI-driven workflow (see Table 2 for values for prespecified subpopulations and Supplementary Table 1 for values for additional subpopulations). All prespecified subpopulations also had a higher RR (Δ0.48–0.99 recalls per 100 exams = 5.0–9.2%, P ≤ 0.001), except women in the ‘other race’ category (Δ0.31 recalls per 100 exams = 2.6%, P = 0.135). CDR increases were greater than RR increases in all cases, resulting in a significant improvement in PPV1 in 4 out of the 7 subpopulations of interest (whole population; white, non-Hispanic women (Δ0.95 cancers per 100 recalls = 16.0%, 95% CI 3.7–29.7%, P = 0.010); women with non-dense breasts (Δ0.74 cancers per 100 recalls = 13.8%, 95% CI 2.8–26.1%, P = 0.014); and women with dense breasts (Δ0.56 cancers per 100 recalls = 15.3%, 95% CI 3.9–27.8%, P = 0.008)). In the other three subpopulations (Black, non-Hispanic women, Hispanic women, and women in the ‘other race’ category of race and ethnicity), a similar trend was observed with a non-significantly higher PPV1 for the multistage AI-driven workflow cohort; however, the study was not powered to detect an increase in PPV1 in any of the subpopulations. The distribution of cancers across AI suspicion levels did not change between cohorts (Supplementary Table 2).

CDR, RR and PPV1 in the standard of care versus the multistage AI-driven workflow cohort across the whole population, in individual race and ethnicity subpopulations, and divided up by breast density. See Table 2 for numerator and denominator values. Data are presented as the unadjusted rate, and lines are the 95% Agresti and Coull CIs. All standard of care (grey) and multistage AI-driven workflow (purple) paired comparisons indicated with an asterisk are significant (*P < 0.05) under an unadjusted one-sided chi-squared comparison (see Table 2 for exact P values). See Supplementary Table 1 for details of CDR, RR and PPV1 and comparisons for other demographic groups.

Adjusted results, which simultaneously accounted for age, race and ethnicity, breast density, and the radiologist reading the study, showed an overall marginal effect for the CDR of 1.29 cancers per 1,000 exams (95% CI 0.35–2.23, P = 0.007), for RR of 0.72 recalls per 100 exams (CI 0.03–1.41, P = 0.04) and for PPV1 of 0.92 cancers per 100 recalls (95% CI 0.07–1.78, P = 0.03). The consistency of these adjusted effects with the unadjusted findings indicates that the improved CDR and cancer detection efficiency observed are robust, even after controlling for potential confounding variables such as patient age, race and ethnicity, breast density, and the reading radiologist. This result further supports comparable performance of the multistage AI-driven workflow across all patient subpopulations. In addition, interaction terms between the multistage AI-driven workflow and patient factors such as age, race and ethnicity, and breast density were not statistically significant, with the exception of the term for multistage AI-driven workflow in ≥80 years; however, the population of women ≥80 was small (N = 15,550). This suggests comparable performance of the multistage AI-driven workflow across all patient subpopulations. See Supplementary Table 3 for full details on all terms in the adjusted models.

Discussion

This large real-world study demonstrated that a multistage AI-driven workflow for screening mammography deployed across several diverse US screening practices was associated with improved CDR across all prespecified breast density and race and ethnicity subpopulations. For the overall population, the CDR increased by 0.99 per 1,000 screens (4.59 to 5.58, P < 0.001). PPV1 also improved for the whole population and all powered subpopulations of interest in both the unadjusted and adjusted analysis. While RR increased by 5.7% (10.6 to 11.1, P = 0.015) overall, the increase in PPV1 suggests that additional recalls and diagnostic evaluations were appropriate because they led to a higher rate of additional cancer diagnoses. Increases in CDR held for women with dense and non-dense breasts, as well as for Black, non-Hispanic; Hispanic; and white, non-Hispanic women. Our results suggest that the multistage AI-driven workflow would not widen existing disparities in US screening outcomes, but rather could provide equitable benefits across key subpopulations of women. This level of increase in the CDR represents a potential additional 34,097 cancers found through early breast cancer screening over the 43 million mammograms performed in the USA each year, assuming that 80% of these are screening mammograms13.

The overall CDR increase observed here of 21.6% is greater than estimates of increased CDR (11%) associated with double reading 100% of exams in the USA18, highlighting the efficiency of combining a CADe/x device with a safeguard review in which only 8% of cases required a second review. This CDR increase is in addition to that already expected from a transition from full-field digital mammography to DBT of approximately 36% (ref. 19). Finally, the CDR increase was greater than that reported in ref. 5, which found an increase of 0.7 cancers per 1,000 screens, or ref. 9, which found a 17% increase in CDR in a double-reading standard-of-care cohort. The study in ref. 5 was of a prospective trial of 16,000 exams implementing an additional review process, analogous to the SafeGuard Review presented here, but in a European screening setting with double reading of full-field digital mammograms in women with 2-year screening intervals. References 9,10 demonstrated that, in the European double-reading setting, replacing one of the two readers with AI can achieve an increase in CDR or non-inferior CDR, respectively, alongside a decrease in the RR. However, double reading is not standard in the USA, so it is difficult to directly compare results in Europe with the USA. These different results highlight the importance of demonstrating the effectiveness of AI-assisted screening across varied populations and within the context of different workflows, screening paradigms and algorithm versions.

The CDR was 22.7% higher for women with dense breasts with versus without the multistage AI-driven workflow, suggesting that it may help address concerns for missed cancers in this subpopulation. With new US federal mandates requiring that women be informed of their density category after each screening mammogram20,21, the multistage AI-driven workflow may represent a welcome choice for women with dense breasts. These results are in contrast to those recently reported by ref. 6, which showed a non-significant improvement of CDR in dense breasts over a large age-restricted (50–69 years) prospective European cohort; however, this study used a different AI algorithm and different workflow where AI assistance was added to double reading.

Black and Hispanic women showed large relative improvements in their CDR (20.4% and 21.8%, respectively). Absolute increases in CDR were smaller for Black, non-Hispanic and Hispanic women than for white, non-Hispanic women, which can be explained by the lower reported incidence of cancer in Black, non-Hispanic and in Hispanic than in white, non-Hispanic women22,23 that is also seen in our data (Fig. 3). One of the driving forces for the recent revisions to the US Preventive Services Task Force screening recommendations for starting age of 40 years rather than 50 years was to improve health equity in breast cancer outcomes, especially for Black women24. By increasing the CDR, our study suggests that the multistage AI-driven workflow may facilitate the detection of cancers in earlier screening exams for racial and ethnic minorities, a population that has historically faced breast cancer diagnosis at later stages with worse morbidity and mortality24.

The clinically meaningful and statistically significant increase in PPV1 in the whole population and trend observed across all subpopulations of interest indicate that the additional recalls made with the multistage AI-driven workflow resulted in detecting additional cancers at a higher rate than the standard of care. Although the absolute increase in PPV1 was smaller for Black, non-Hispanic women than it was for white women (0.60 versus 0.95), the adjusted model did not demonstrate a statistically significant difference in the impact of the multistage AI-driven workflow on different racial and ethnic subpopulations. This suggests that, when demographic and radiologist-level factors are controlled, the relationship between the multistage AI-driven workflow and CDR, RR and PPV1 is similar for all subpopulations.

The strengths of our study include that this is one of the largest real-world US studies evaluating mammography screening with AI so far and includes data across 4 states, 109 individual sites and 96 individual radiologists. Most previous studies measuring CDR with DBT have been small and performed predominantly in academic research centres2,3. In contrast, our study represents real-world evidence collected from a large number of geographically diverse outpatient imaging centres and may better reflect the average US patient experience. The combination of (1) a CADe/x device on all cases and (2) a safeguard review by an expert reviewer for high-suspicion cases interpreted as normal by the initial radiologist is unique, particularly in a single-reading paradigm. The second-stage SafeGuard Review provides a process analogous to the consensus review in double-reading screening programmes in which all exams are read by at least two radiologists. However, in our workflow, only a small set of patients (8%) at highest risk for having cancer are double read. This enables nearly the full cancer detection benefits of double reading for <10% of the added effort and the cost of the software. To reduce radiologist-level factors, only radiologists who interpreted a minimum number of exams in both cohorts and only exams from sites that were present in both cohorts were included. As such, the sites, interpreting radiologists and patient characteristics are comparable in the two cohorts. Furthermore, a 2-month learning curve period before starting the post-intervention period was used, similar to previous studies25. Finally, we observe similar changes in CDR, RR and PPV1 across the radiology practices (Supplementary Table 4) indicating that the AI algorithm and SafeGuard Review workflow are generalizable across the diverse set of practices investigated.

There are also several limitations to our study. First, there were insufficient follow-up data after screening to report sensitivity, specificity, false-negative rates, interval cancers or cancer stage at diagnosis. However, previous work comparing radiologist performance with versus without this CADe/x device (in both cases without the SafeGuard Review component) showed that radiologists improved sensitivity (80.8% without versus 89.6% with the device, P < 0.01) and did not reduce specificity (75.1% without versus 76.0% with the device, P = 0.65)14. In addition, the same study showed that radiologists reading with DeepHealth Breast AI had improved sensitivity across all lesion sizes and pathologies (invasive versus non-invasive), and ref. 26 reported similar distributions of invasive and triple negative cancers using the SafeGuard Review workflow described here compared with cancers identified without AI assistance. Second, it was not possible to extract the clinical impact of the CADe/x device from the SafeGuard Review owing to the unique aspects of the AI-driven workflow (for example, integration with existing imaging viewing software; workflow paths that include both the CADe/x and SafeGuard Review devices on a single exam; and user training and knowledge of both devices). Our results are therefore applicable to only the device under investigation. Third, we chose not to correct for multiple comparisons because our outcomes were highly correlated (for example, Black, non-Hispanic women were also included in the whole population; CDR, RR and PPV1 are related by radiologist behaviour and so on). However, we do account for correlation in the data through the adjusted generalized estimating equations models, and these adjusted results support the conclusions drawn from the unadjusted results. Finally, the cohorts were divided into two sequential groups in this real-world observational study, which does not control for unknown biases and confounders in the patient groups as a randomized trial would. However, the study prioritized external generalizability by assessing the AI workflow in a real-world clinical setting, thus avoiding biases that could arise from a highly controlled interventional study. Comparison between demographics, however, showed similar patient characteristics between groups, and these main confounders were controlled in the adjusted analysis.

In summary, the ASSURE study presents large-scale, real-world evidence that using a multistage AI-driven workflow is associated with improved mammography screening performance for the population as a whole and across density and key race and ethnicity subpopulations. These results demonstrate that the multistage AI-driven workflow can provide significant and equitable cancer detection benefits to women.

Methods

Data were collected in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and under Advarra institutional review board approval (DH-ACC-001-030623) with a waiver of consent. A multistage AI-driven workflow for breast cancer screening was prospectively deployed in the USA at 5 practices (109 sites, 96 radiologists) in a diverse, nationally distributed (California, Delaware, Maryland and New York) outpatient imaging setting. All radiologists were board certified and Mammography Quality Standards Act (MQSA) qualified, and no trainees were included in this study. A mixture of breast imaging specialists and general radiologists were investigated. Our primary outcomes were unadjusted CDR, RR and PPV1 before and after deployment of the multistage AI-driven workflow for the overall screening population, and for the key subpopulations of women with dense breasts and Black, non-Hispanic women. Secondarily, adjusted and unadjusted CDR, RR and PPV1 were investigated before and after AI deployment for all subpopulations including women with non-dense breasts; Hispanic women; white, non-Hispanic women; and women whose race and ethnicity was not Black, non-Hispanic; Hispanic; or white, non-Hispanic (other race); and obtained multivariable adjusted CDR, RR and PPV1 estimates.

Multistage AI-driven workflow

The multistage AI-driven workflow consists of two components (Fig. 1a): interpreting the mammogram with a computer-aided detection and diagnosis (CADe/x) device (DeepHealth Breast AI version 2.x, DeepHealth) and an AI-supported SafeGuard Review. The previously validated CADe/x device showed improved performance for both general radiologists and breast imaging specialists in a reader study14. The SafeGuard Review routes exams above a predetermined DeepHealth Breast AI threshold that were not recalled by the interpreting radiologist for review by a breast imaging specialist (reviewer). Reviewers were selected by the breast imaging practice leadership based on experience and clinical performance record. If the reviewer agreed with the AI and found the exam suspicious, they discussed the exam with the interpreting radiologist, who made the final recall decision.

Study design

All screening exams at the five practices during the study period were eligible for inclusion in the study. Exams between 1 September 2021 and 19 May 2022 did not receive the multistage AI-driven workflow and formed the standard-of-care comparison cohort. The multistage AI-driven workflow was deployed on all exams satisfying the product instructions for use from 20 May 2022 to 31 December 2022 (Fig. 1b). Data were collected from 3 August 2022 to 31 December 2022, starting 2 months after deployment to allow radiologists to adapt to the new technology (multistage AI-driven workflow cohort). Radiologists in both cohorts had access to non-AI-based computer-aided detection outputs (ImageChecker, Hologic). AI suspicion levels were determined for screening exams resulting in a cancer finding for both periods using DeepHealth Breast AI 2.x.

Exam eligibility

Exams were included if they met all exam, patient and radiologist criteria (Fig. 2). Exam criteria included: bilateral screening DBT without implants or additional diagnostic imaging; American College of Radiology Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) interpretation of 0, 1 or 2; valid breast density; compatibility with DeepHealth Breast AI 2.x; and met DeepHealth Breast AI 2.x input requirements (see Supplementary Note 1 for details). Patient criteria: ≥35 years old and self-reported as female. Radiologist criteria: interpreted screening mammograms during both study periods based on the MQSA required minimum of 960 every 2 years17 (for example, 372 exams during the standard-of-care period and 175 exams during the multistage AI-driven workflow period) resulting in excluding 83 radiologists and the 14,472 (5.7%) exams they read.

Data collection

Examination-level, patient-level and outcome-level data were collected from screening mammograms during both study periods. Exam data collected included screening BI-RADS assessment and breast density (non-dense: BI-RADS A, fatty or B, scattered fibroglandular; versus dense: C, heterogeneously dense or D, extremely dense) as reported by the interpreting radiologist. Patient data collected included self-reported sex, age at exam, and self-reported race and ethnicity (Asian; Black, non-Hispanic; Hispanic; Native American; Pacific Islander; white, non-Hispanic; multiracial (listed ≥1 race) or other; or declined to specify). Owing to limitations on sample size, women who identified as Asian; Native American; Pacific Islander; multiracial or other; or who declined to specify were combined for some analyses into a category called other race. Four exams missing breast density were excluded. Adverse events were monitored as part of post-market surveillance activities.

Metrics

Metrics were calculated based on the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium Standard Definitions v3.1 and the BI-RADS Atlas 5th edition, and included CDR, RR and PPV1 (refs. 27,28). The CDR was defined as the number of BI-RADS 0 (positive) exams with a malignant biopsy (invasive lobular carcinoma, invasive ductal carcinoma, ductal carcinoma in situ) divided by the total number of exams multiplied by 1,000. The RR was defined as the percentage of screening exams that were positive. The PPV1 was defined as the percentage of positive exams that resulted in a malignant biopsy.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics (unadjusted mean and 95% CI29) were used to evaluate the CDR, RR and PPV1 in both cohorts for the whole population and for all subpopulations. Chi-squared tests were used for unadjusted CDR, RR and PPV1 estimates for the multistage AI-driven workflow across the whole population and in the subpopulations of interest (Black, non-Hispanic women; Hispanic women; white, non-Hispanic women; women with non-dense breasts; and women with dense breasts). As these are real-world data, and because all the results are correlated and not independent, we did not correct for multiple comparisons. To account for the correlated nature of the data and to test whether the multistage AI-driven workflow showed differences between subpopulations, generalized linear models with generalized estimating equations were used to predict multivariable adjusted CDR, RR and PPV1 fit with terms for covariates known to influence screening performance, including race and ethnicity, breast density, and age, and grouped on interpreting radiologist to account for radiologist-level factors on screening metrics15,16,17. To evaluate differences in the multistage AI-driven workflow performance across subpopulations, terms were included for the cohort and for the interaction between cohort and each of the subpopulation terms (for example, multistage AI-driven workflow: Black, non-Hispanic; multistage AI-driven workflow: dense). Number of exams undergoing the SafeGuard Review workflow and their outcomes were also reported. All analyses were performed with Python 3.10 (packages: statsmodels, scipy) with a critical P value of 0.05.

Power analysis

A post-hoc sample size calculation was completed based on two proportions, two-sided power analysis to determine the sample size required to address the primary outcome of the CDR across the whole population and in subpopulations of interest. Assuming a base CDR of 5 cancers per 1,000 exams, a 23% increase in th CDR from the standard of care to the multistage AI-driven workflow, α = 0.05, β = 0.2 and sampling ratio of 1.8 standard-of-care exams for each multistage AI-driven workflow exam, 94,822 exams were required in the standard of care and 52,679 exams for the multistage AI-driven workflow cohort. Using the same approach to determine the sample size required to evaluate PPV1, from a base PPV1 of 4% and a 15% increase between cohorts, 25,595 recalls were required in the standard of care and 14,219 recalls required in the multistage AI-driven workflow cohort.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study form part of DeepHealth Inc. intellectual property and are strictly controlled by the supervising institutional review board. As such the data are not accessible.

Code availability

The codes that support the findings of this study form part of DeepHealth Inc. intellectual property and are not accessible.

References

Sung, H. et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71, 209–249 (2021).

Tabár, L. et al. Swedish two-county trial: impact of mammographic screening on breast cancer mortality during 3 decades. Radiology 260, 658–663 (2011).

Marmot, M. G. et al. The benefits and harms of breast cancer screening: an independent review. Lancet 380, 1778–1786 (2012).

Miller-Kleinhenz, J. M. et al. Racial disparities in diagnostic delay among women with breast cancer. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 18, 1384–1393 (2021).

Ng, A. Y. et al. Prospective implementation of AI-assisted screen reading to improve early detection of breast cancer. Nat. Med. 29, 3044–3049 (2023).

Eisemann, N. et al. Nationwide real-world implementation of AI for cancer detection in population-based mammography screening. Nat. Med. 31, 917–924 (2025).

Hernström, V. et al. Screening performance and characteristics of breast cancer detected in the Mammography Screening with Artificial Intelligence trial (MASAI): a randomised, controlled, parallel-group, non-inferiority, single-blinded, screening accuracy study. Lancet Digit. Health 7, e175–e183 (2025).

Salim, M. et al. AI-based selection of individuals for supplemental MRI in population-based breast cancer screening: the randomized ScreenTrustMRI trial. Nat. Med. 30, 2623–2630 (2024).

Lauritzen, A. D. et al. Early indicators of the impact of using AI in mammography screening for breast cancer. Radiology 311, e232479 (2024).

Dembrower, K., Crippa, A., Colón, E., Eklund, M. & Strand, F. Artificial intelligence for breast cancer detection in screening mammography in Sweden: a prospective, population-based, paired-reader, non-inferiority study. Lancet Digit. Health 5, E703–E711 (2023).

Oberije, C. J. G. et al. Assessing artificial intelligence in breast screening with stratified results on 306 839 mammograms across geographic regions, age, breast density and ethnicity: A Retrospective Investigation Evaluating Screening (ARIES) study. BMJ Health Care Inform. 32, e101318 (2025).

Logan, J., Kennedy, P. J. & Catchpoole, D. A review of the machine learning datasets in mammography, their adherence to the FAIR principles and the outlook for the future. Sci. Data 10, 595 (2023).

Centers for Devices and Radiological Health MQSA national statistics. FDA https://www.fda.gov/radiation-emitting-products/mammography-information-patients/mqsa-national-statistics (2025).

Kim, J. G. et al. Impact of a categorical AI system for digital breast tomosynthesis on breast cancer interpretation by both general radiologists and breast imaging specialists. Radiol. Artif. Intell. 6, e230137 (2024).

Kerlikowske, K. et al. Population attributable risk of advanced-stage breast cancer by race and ethnicity. JAMA Oncol. 10, 167–175 (2024).

Sprague, B. L. et al. Assessment of radiologist performance in breast cancer screening using digital breast tomosynthesis vs digital mammography. JAMA Netw. Open 3, e201759 (2020).

Lawson, M. B. et al. Multilevel factors associated with time to biopsy after abnormal screening mammography results by race and ethnicity. JAMA Oncol. 8, 1115–1126 (2022).

Destounis, S. V. Computer-aided detection and second reading utility and implementation in a high-volume breast clinic. Appl. Radiol. 33, 8–12 (2004).

Alabousi, M. et al. Performance of digital breast tomosynthesis, synthetic mammography, and digital mammography in breast cancer screening: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 113, 680–690 (2020).

Liao, J. M. & Lee, C. I. Strategies for mitigating consequences of federal breast density notifications. JAMA Health Forum 4, e232801 (2023).

Kressin, N. R., Slanetz, P. J. & Gunn, C. M. Ensuring clarity and understandability of the FDA’s breast density notifications. JAMA 329, 121–122 (2023).

Mandelblatt, J. S. et al. Population simulation modeling of disparities in US breast cancer mortality. J. Natl Cancer Inst. Monogr. 2023, 178–187 (2023).

DeSantis, C. E. et al. Breast cancer statistics, 2015: convergence of incidence rates between black and white women. CA Cancer J. Clin. 66, 31–42 (2016).

Elmore, J. G. & Lee, C. I. Toward more equitable breast cancer outcomes. JAMA 331, 1896–1897 (2024).

Miglioretti, D. L. et al. Digital breast tomosynthesis: radiologist learning curve. Radiology 291, 34–42 (2019).

Haslam, B., Kim, J. & Soresen, A. G. An AI-based safeguard process to reduce aggressive missed cancers in dense breasts at screening mammography. In Proc. 2023 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium 84 PO2-29–04 (AACR, 2024).

Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium: Evaluating Screening Performance in Practice (National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services, 2004).

D’Orsi, C. et al. ACR BI-RADS® Atlas, Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (American College of Radiology, 2013).

Agresti, A. & Coull, B. A. Approximate is better than ‘exact’ for interval estimation of binomial proportions. Am. Stat. 52, 119–126 (1998).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge P. Radecki, R. Schnitman and A. Cochran, who helped evaluate DeepHealth Breast AI on cancer exams from the standard-of-care period. We also acknowledge B. Glocker for reviewing the paper and providing valuable insights. No external funding was provided for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.D.L. and E.A.W. analysed and interpreted the data and wrote the paper. B.H. and A.G.S. conceived of the study and contributed to writing and editing the paper. M.P.M., A.Y.N. and J.G.K. contributed to data analysis and editing of the paper. C.I.L. and D.S.M.B. assisted with study design, editing of the paper and analysis. All authors read and approved the final paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

L.D.L., E.A.W., M.M., A.Y.N., J.G.K., B.H. and A.G.S. are employees and/or shareholders of DeepHealth Inc. C.I.L. and D.S.M.B. are consultants to DeepHealth Inc. DeepHealth Inc products are used in this study. The medical devices used in this study utilize the following patents: US11783476B2, US12367574B2, WO2024233378A1.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Health thanks Aisha Lofters and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Note 1, Tables 1–5 and References.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Louis, L.D., Wakelin, E.A., McCabe, M.P. et al. Equitable impact of an AI-driven breast cancer screening workflow in real-world US-wide deployment. Nat. Health 1, 58–66 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44360-025-00001-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44360-025-00001-0