Abstract

Endosomal entrapment limits the intracellular delivery of many chemotherapeutics, creating a need for nanoparticle systems that promote endosomal escape and improve therapeutic efficacy. This study presents the design and characterization of a novel family of pH responsive polybasic nanogels prepared by UV initiated polymerization. Their pH dependent swelling behavior, which is critical for targeted delivery, was systematically tuned by incorporating different hydrophobic groups into the P(DEAEMA) grafted PEGMA system using n-alkyl methacrylate monomers that vary in steric bulk and chain length. These parameters altered the nanogel pKa, the critical swelling pH, and the onset of swelling, enabling strong endosomolytic activity at the pH values of early and late endosomes. The resulting nanogels have an appropriate size to exploit the enhanced permeability and retention effect, exhibit high drug loading, remain stable in biological media, and show no intrinsic toxicity. Together these features create an efficient platform for intracellularly targeted drug delivery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nanoparticle carriers enable precise control over drug biodistribution, pharmacokinetics, and intracellular delivery1. By exploiting the enhanced permeation and retention (EPR) effect, nanoparticle formulations can achieve several-fold higher accumulation in tumors compared with free drug administration, while reducing systemic exposure and dose-limiting toxicity2,3,4,5. They also provide a route to deliver drugs directly into the cytosol or nucleus, bypassing efflux pumps that drive multidrug resistance6. Despite decades of progress, however, most carriers still face fundamental engineering barriers that restrict clinical translation7,8,9. Following systemic injection, nanoparticles must navigate circulation, avoid rapid clearance by the mononuclear phagocyte system, and resist aggregation or opsonization caused by protein corona formation10. Even when these hurdles are overcome, intracellular trafficking presents the most significant bottleneck as majority of nanoparticles remain trapped in endosomal compartments, where payloads are degraded rather than released11. At the same time, most formulations are optimized for either hydrophilic or hydrophobic drugs, but not both, limiting their utility in modern oncology regimens that increasingly rely on combination therapies12. The absence of predictive design rules linking material chemistry to intracellular performance has slowed progress, leaving nanoparticle development heavily empirical. Addressing these challenges requires materials in which network composition can be systematically tuned to couple stability in circulation with responsive behavior inside cells.

Polybasic, pH-responsive nanogels provide such a platform because their chemical architecture directly connects polymer composition to function13. Protonation of pendant amines in acidic endosomal environments induces osmotic swelling, generating internal pressure that disrupts membranes and enables cytosolic release of encapsulated cargo14. Poly (ethylene glycol) (PEG) grafts further stabilize nanogels in circulation by reducing protein adsorption and prolonging half-life15. The balance of these properties swelling dynamics, colloidal stability, cytocompatibility, and drug–polymer interactions is governed by copolymer composition16. A defining advantage of nanogels is their capacity for stimuli-responsiveness17. Beyond pH, polymer systems have been designed to respond to enzymatic activity, redox gradients, temperature, and ionic strength, but pH is particularly attractive because it leverages predictable gradients across biological environments: neutral blood, acidic tumor extracellular matrix, and progressively acidic endosomes and lysosomes18,19. Harnessing these differences requires careful tuning of nanogel pKa and transition sharpness, ensuring stability under physiological conditions but rapid destabilization after uptake. Among compositional levers, hydrophobic modification is especially effective. Side-chain length and steric bulk alter polymer pKa, adjust the onset of swelling, and modulate affinity for hydrophobic molecules. This tunability is critical for engineering carriers that are simultaneously stable in circulation and active inside cells. The design space, however, is constrained since the insufficient hydrophobicity yields poor loading and weak endosomal activity, while excessive modification promotes aggregation or toxicity. Previous reports have demonstrated benefits using isolated modifiers such as tert-butyl methacrylate, but no systematic framework exists to compare how distinct hydrophobic chemistries shape nanogel performance18. As a result, development has remained largely empirical, with limited predictive value for future designs.

Here, we establish such a framework by synthesizing a family of P(DEAEMA-g-PEGMA) nanogels via aqueous, UV-initiated photo emulsion polymerization. This scalable method produces sub-100 nm particles without requiring RAFT or ATRP chemistry, enabling rapid evaluation of compositional variables20. Using a library of ten n-alkyl methacrylate comonomers including methyl, ethyl, isopropyl, tert-butyl, phenyl, cyclohexyl, benzyl, butyl, hexyl, and ethylhexyl derivatives we systematically evaluated how hydrophobic moieties govern nanogel function. Comparative analysis revealed how chain length and steric bulk tune nanogel pKa, swelling dynamics, colloidal stability, drug loading, cytocompatibility, and endosomolytic activity. These results provide direct structure–property–function relationships, shifting nanogel design from trial-and-error optimization toward predictive engineering. Beyond extending the P(DEAEMA)-g-PEGMA platform for chemotherapeutic delivery, the design principles established here apply broadly to stimuli-responsive polymer networks. In particular, they demonstrate how targeted hydrophobic modification can be leveraged to balance stability, responsiveness, and compatibility across diverse therapeutic contexts. By linking polymer chemistry to biological outcomes, this study advances nanogel development toward rule-based design, providing a foundation for translational progress in oncology and other biomedical applications.

Results and discussion

Nanogel design and synthesis

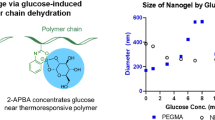

A novel family of Poly (DEAEMA-g-PEGMA) nanoscale hydrogels (nanogels) with varying network hydrophobicity was designed and synthesized. The nanogel base formulation is comprised of: (i) a hydrophilic, cationic monomer 2-(diethylamino)ethyl methacrylate (DEAEMA) that imparts the pH-response by ionization of amine pendant groups, (ii) a tetra ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (TEGDMA) crosslinker to improve drug retention and mechanical stability over self-assembled counterparts, and (iii) a poly(ethylene glycol) methacrylate (PEGMA) graft to impart solution and serum stability. The structures of the monomers are shown in Fig. 1. To synthesize these particles, we have previously developed a novel, robust method for synthesizing pH-responsive nanogels using an aqueous, UV-initiated emulsion free radical polymerization21. This heterogeneous polymerization allows the hydrophobic cationic monomer to form the nanoparticle core and PEGMA to be grafted primarily onto the surface without interfering with the polymer buffering properties. The P(DEAEMA-g-PEGMA) nanogels undergo a pH-dependent hydrophobic-to-hydrophile phase shift. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 1, the 90-nm nanogels (hydrodynamic diameter) collapse in neutral conditions and can swell to 130-nm in response to acidic pH. The nanogels have a highly controllable particle diameter and polydispersity and show a rapid transition to the swollen state with a large volume swelling ratio. These characteristics are desired to improve diffusional release of the drugs in the swollen state.

A The nanogels are comprised of (1) a hydrophilic, cationic monomer 2-(diethylamino) ethyl methacrylate (DEAEMA) that imparts the pH-response by ionization of amine pendant groups; (2) a tetraethylene glycol dimethacrylate (TEGDMA) crosslinker to improve CA retention; and (3) surface-grafted poly (ethylene glycol) methacrylate (PEGMA) to impart serum stability. Nanogels are synthesized using a UV-initiated oil-in-water emulsion polymerization using Brij30 and MyTAB as emulsion stabilizers and Irgacure 2959 as the initiator. B Hydrophobic n-alkyl methacrylate monomers incorporated into the co-polymer network with systematic variation in chain length (methyl, ethyl, butyl, hexyl, and 2-ethylhexyl methacrylate) and in steric bulk (ethyl, isopropyl, tert-butyl, phenyl, cyclohexyl, and benzyl methacrylate).

To successfully apply the nanogels for intracellular delivery, swelling must occur in the pH range of the early endosome inside the cell. However, the P(DEAEMA-g-PEGMA) polymer pKa demonstrated swelling and release in physiological conditions, prior to cell uptake (Supplementary Fig. 1, swelling onset at pH 7.6 and critical swelling at pH 7.3). The nanogel pH-swelling response is critical for targeted drug delivery and depends heavily on the co-polymer composition and ratios. The tumor microenvironment is characterized as slightly acidic compared to physiological pH (pH 6.8-7.2) due to lactate secretion from anaerobic glycolysis, and the intracellular early and late endosomes are characterized as pH 4.5-6.822. In addition, initial loading studies with the particles demonstrated suitability for loading and release of a single hydrophilic compound23. However, approximately 40% of chemotherapeutic agents currently on the market and 90% of molecules in the pharmaceutical discovery pipeline are highly lipophilic and water insoluble24.

To this extent, the inclusion of hydrophobic moieties in the copolymer network was investigated to both shift the nanogel pKa lower and increase drug loading by improved drug-polymer interactions. The aqueous, UV-initiated emulsion free radical polymerization method represents a platform from which abundant combinations of methacrylate-based hydrogels could be produced to create responsive hydrogels with nanoscale dimensions and tunable physicochemical properties.

As shown in Fig. 1, inclusion of hydrophobic moieties in the P(DEAEMA)-g-PEGMA polymer system was explored in a systematic fashion with a series of n-alkyl methacrylate monomers. The monomers varied in both steric bulk and chain length (methyl methacrylate, ethyl methacrylate, isopropyl methacrylate, tertbutyl methacrylate, phenyl methacrylate, cyclohexyl methacrylate, benzyl methacrylate, butyl methacrylate, hexyl methacrylate, and ethylhexyl methacrylate). All nanogels were made using the same molar feed ratios.

Composition analysis by 1H-NMR and FTIR spectroscopy

ATR-FTIR and 1H NMR spectroscopy was utilized to assess the composition for each set of nanogels. As shown in Fig. 2, 1H-NMR was utilized to estimate nanogel composition using the respective linear polymer synthesized without the crosslinking agent. All spectra were obtained in deuterium oxide and were normalized to an internal standard. Peaks of DEAEMA (δ 3.14, 4H) demonstrate that the cationic monomer can be copolymerized successfully without significant differences while varying the co-monomer composition. Each hydrophobic monomer was analyzed according to its respective peak shift, and minimal differences in the molar ratio were observed with variations in the co-monomer composition. Additionally, minimal differences were observed in PEG compositions among formulations synthesized with different hydrophobic monomer species.

A 1H-NMR spectra of linear cationic nanogels with varied co-monomer composition through inclusion of n-alkyl methacrylate monomers with varied chain length. All spectra obtained in deuterium oxide and are normalized to the internal standard. B 1H-NMR spectra of linear cationic nanogels with varied co-monomer composition through inclusion of n-alkyl methacrylate monomers with varied steric bulk. All spectra obtained in deuterium oxide and are normalized to the internal standard. C ATR-FTIR spectra of nanogels with varied co-monomer composition through inclusion of n-alkyl methacrylates with varied chain lengths. All spectra are normalized to ester carbonyl peak at 1725 cm−1. Full spectra of original particle (dark blue), methyl methacrylate (blue), ethyl methacrylate (green), hexyl methacrylate (orange), and 2-ethylhexyl methacrylate (red). Spectra shifted vertically for clarity. Spectra shown on same scale, regions 3100 to 2700 cm−1 and 1550 to 1250 cm−1, respectively.

As shown in Fig. 2, ATR-FTIR was utilized to assess the composition of lyophilized nanogels in the crosslinked state. In each case, the characteristic methacrylate ester carbonyl stretching vibration at 1725 cm−1 was used to normalize the spectrum. Formulations were compared for differences in hydrophobic content (aromatic rings, simple CH stretching vibrations for saturated aliphatic species in the range of 3000 and 2800 cm−1) and poly (ethylene glycol) content via the ether peak at 1106 cm−1 relative the ester C-O-C peak at 1142 cm−1. Characteristic peaks for tertiary amines and aliphatic were not readily distinguished. The O-H stretch band can be seen in the 3500–3200 cm−1 is representative of the ester groups and possible hydrogen bonding.

PEG has characteristic strong absorption peaks arising from the C-H and C-O stretching vibrations detected in all the polymer formulations. Like the 1H-NMR analysis, minimal differences were seen in PEG compositions among formulations synthesized with different hydrophobic monomer species. With the presence of saturated aliphatic species, increasing and a slight shift in the –CH stretching vibrations is observed in the range of 3000 and 2800 cm−1. Interesting to note is the decreasing presence of simple –C-H- bending vibrations in the 1500–1300 cm−1 range that can be seen for the nanoparticles with increasing chain length owing to the presence of a long hydrocarbon side chain, and the increasing presence of those peaks in methyl methacrylate and ethyl methacrylate due to absence of a long hydrocarbon side chain.

Particle size, polymer pKa, and pH-swelling response

Overall, all nanoparticles synthesized maintained diameters appropriate for tumor accumulation by the EPR effect (Table 1). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) of particles made with no hydrophobic monomer confirmed the nanoscale size of the particles and confirmed a uniform spherical morphology with minimal aggregation (Supplementary Figure 2). Nanoparticles made with increasing hydrophobicity by either steric bulk or chain length are slightly smaller in diameter and showing a uniform spherical morphology.

The swelling response observed by dynamic light scattering (DLS) illustrates the influence of hydrophobic moiety incorporation on pH-dependent volume swelling of the NP formulations. The volume swelling ratio (VSR) is calculated from the volume of the particle in the fully swollen state divided by the volume of the particle in the fully collapsed state. The critical swelling pH is defined by fitting a hyperbolic tangent or sigmoidal function to the measured hydrodynamic diameter (DH) and determining the inflection point. In this case, data were fit to a hyperbolic tangent function of the form:

Taking the second derivative of Eq. 1 yields the inflection point of the curve, which is taken to represent the critical swelling pH (pHcritical):

Figure 3 shows the particle volume swelling ratio as a function of pH. A broad range of physicochemical properties can be imparted through modification to the network hydrophobicity, polymer composition, and chain length versus steric bulk. The degree of volume swelling decreases as the network hydrophobicity is increased, regardless of increasing chain length or steric bulk. This observation may be ascribed to the persistence of hydrophobic associations in the polymer network that resist solvation and limit elastic deformation of the network. Increasing the alkyl chain length significantly broadens the transition with negligible impact to onset of swelling, while increasing the steric bulk maintains breadth of transition while offering a substantial decrease in onset. This is ideal as it requires more acidic conditions to trigger swelling and still maintain a rapid, tight transition from collapsed to swollen.

A Increasing alkyl chain length significantly broadens the transition with little impact to onset, while (B) increasing steric bulk maintains breadth of transition while offering a substantial decrease in onset. Data represent mean ± SEM (n = 3). C Nanogel effective surface ζ-potential as a function of pH demonstrates that the modifications to the co-polymer composition predominantly affect the network core. For simplicity, shown are the select formulations with varied pHcritical values and volume swelling ratios. Data represent mean ± SEM (n = 3).

Importantly, addition of a hydrophobic monomer to the co-polymer network enables to precisely tune the response to swell in the early endosomal compartment. Swelling in ionizable hydrogel systems is driven by a balance of thermodynamic and physical forces. As network hydrophobicity increases, greater ionization (i.e., lower pH) is required to promote polymer/solvent/ion interactions over polymer/polymer interactions, resulting in more acidic swelling onset and critical pHs25.

The polymer pKa was estimated using a well-known microwell plate pKa assay based upon 2-(p-toluidinyl) naphthalene-6-sulfonic acid (TNS)26. The anionic fluorophore interacts with cationic charges, such as the tertiary amine in 2-(diethylamino)ethyl methacrylate when protonated in acidic pH envrionments. As such, minimal fluorescence was observed above the pKa when nanogels were in the uncharged state and fluorescence reached a maximum when cationic charges and hydrophobic interactions dominate. All nanoparticles were fully deprotonated at pH 10, and subsequently titrated to pH 4. The pKa was determined from the resulting fluorescence titration using a curve-fit analysis.

Increasing the hydrophobicity of the polymer network shifts the estimated pKa to lower values (Table 1). As expected, the estimated nanoparticle pKa follows a linear relationship with the logP value of the hydrophobic monomer, regardless of increasing chain length or steric bulk (Fig. 4). Similarly, the critical swelling pH (pHcritical) determined from dynamic light scattering follows a linear relationship with the logP value of the hydrophobic monomer, though the slope of the linear relationship varies significantly between increasing chain length or increasing steric bulk (Fig. 4).

A–C The estimated nanoparticle pKa from the TNS assay follows a linear relationship with the logP value of the hydrophobic monomer, regardless of increasing chain length or steric bulk. D–F The critical swelling pH (pHcritical) determined from dynamic light scattering follows a linear relationship with the logP value of the hydrophobic monomer, though the slope of the linear relationship varies significantly between increasing chain length or increasing steric bulk. G–I The estimated pKa and critical swelling pH differ significantly with increasing chain length of the hydrophobic moiety but showed insignificant differences with increasing steric bulk.

The estimated pKa was also compared to the critical swelling pH determined by dynamic light scattering. The estimated pKa and critical swelling pH differed significantly with increasing chain length of the hydrophobic moiety but showed insignificant differences with increasing steric bulk (Fig. 4). This is expected as it was observed that increasing the chain length significantly broadens the pH-swelling transition with minor impact to onset of swelling. Overall, the nanogels demonstrated their suitability as a customizable multicomponent system, and varying the type and ratio of n-alkyl methacrylate monomer allows for precise control over nanogel both pKa and the dynamic swelling response.

Particle surface charge and isoelectric point

Measurements of the effective surface ζ-potential as a function of pH showed insignificant differences between all of the varied formulations. For simplicity, Fig. 3 shows the formulations with the most varied hydrophobicity and volume swelling response. This data is consistent with our expectation that the grafted-PEG content of these particles is the same and demonstrates that the modifications in polymer composition predominately affect the network core. These observations are consistent with those by Amalvy et al., who noted the nature of grafted stabilizer was more important in determining IEP than the nature of core particles in PDEAEMA microgels27. All the formulations have a reversible surface charge, with the same isoelectric point, and a slightly positive ζ-potential at pH 7.4.

At physiological pH, the slightly positive ζ-potential may help facilitate non-specific cell-uptake. The negative ζ-potential observed from pH 10.5 to ~ pH 8.0 can be ascribed to the adsorption of negatively charged hydroxyl ions on the PEG-coated surface and has been noted previously in similar DEAEMA-based materials28,29. Similarly, the positive ζ-potential can be ascribed the surface adsorption of hydronium ions and protonation of amine-containing groups in the network core, which serve to establish an electrical double layer around the particles.

While the measured ζ-potential for all formulations fall outside the limits for electrostatically driven colloidal stability ( ± 30 mV), no flocculation or aggregation was observed throughout the pH range, even that where nanoscale hydrogels possessed a net surface charge of ± 5 mV. This provides additional evidence of the steric stabilization afforded by the PEG surface grafts. Additionally, previous work has estimated the ζ-potential of neat P(DEAEMA) nanogels to be approximately -45 mV at pH 10 and 75 mV at pH 429. This data is consistent with our expectation that the surface layer of PEG is effective at shielding charge at the nanoparticle surface in our formulations.

Drug-polymer Interactions

Improving drug and polymer network interactions is critical to enabling the simultaneous delivery of hydrophobic and hydrophilic therapeutic agents. These interactions can be optimized by tuning the polymer chemistry to accommodate the physicochemical properties of the therapeutic agents.

The effect of the network hydrophobic moiety on the drug-polymer interactions was investigated using hydrophilic and hydrophobic model compounds. Ideally, the hydrophobic drug loading ability can be improved without significantly hindering the ability to load relatively hydrophilic compounds. In this method, two dyes were used as model compounds to enable a more rapid screening approach, rhodamine B as the hydrophilic and fluorescein as the hydrophobic. Both dyes have low molecular weights, and similar logP values and ionization states to commonly used chemotherapeutic agents.

As shown in Fig. 5, the single agent loading studies showed hydrophilic compound loading is minorly affected by variation in network hydrophobicity, and trends with the volume swelling ratio observed by dynamic light scattering. Hydrophobic loading is influenced by improved interactions between drug and hydrogel and is able to overcome the decrease in the volume swelling ratio due to enhanced solubility.

A, B Single agent loading showed hydrophilic compound loading is minorly affected by variation in NG hydrophobicity, and trends with the volume swelling ratio (VSR) observed by dynamic light scattering. Hydrophobic loading is influenced by improved interactions between drug and hydrogel, and is able to overcome the decrease in VSR. C Competitive co-loading demonstrated similar trends. Data represent mean ± SEM (n = 3, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 from “None”).

Competitive co-loading of both agents demonstrated similar trends. The hydrophilic compound is more affected by the variation in hydrophobic monomer when co-loaded with a hydrophobic agent, and as expected still generally trends with the maximum volume swelling ratio. Similarly, the hydrophobic agent loading is affected by the presence of a hydrophilic agent in the more hydrophilic networks, and the networks with increasing hydrophobicity still show preference for the hydrophobic agents. Overall, this data shows promise for being able to achieve a ratiometric loading of multiple therapeutic agents with varying physicochemical properties in a repeatable fashion.

Cytocompatibility

The influence of polymer composition on live cell membrane destabilization and overall live cell health (maintained at pH 7.4) was investigated using an ovarian cancer model cell line (OVCAR-3) as shown in Fig. 6. Cytocompatibility is a measure of overall cell health after exposure to the non-drug loaded particles and can be predictive of any unintended toxic effects from the delivery vehicle alone. The optimal nanogel would be inert at a wide range of concentrations, and, conversely, a non-optimal nanogel would only be inert at very low concentrations (Fig. 6).

Representative results are shown for no hydrophobic monomer (λ) and cyclohexyl methacrylate monomer (•) from (A) a 2 hour MTS assay measuring cell proliferation, (B) a 2 hour LDH assay measuring cell viability, (C) a 24 h MTS assay measuring cell proliferation, and (D) a 24 h LDH assay measuring cell viability. Data represent mean ± SEM (n = 3).

The effect of particle concentration from 0.002 to 2 mg/mL and exposure time at both 2 and 24 h were investigated. Two commercially available assays were used to evaluate overall cell health. The first assay is a colorimetric quantification of viable cells based on the reduction of the soluble tetrazolium salt [3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H tetrazolium] (MTS) compound and serves as an indication of cell proliferation. The second assay is a fluorescent method to detect release of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) from cells with a damaged membrane and serves as an indication of cell viability.

Representative data is shown in Fig. 7 as an example to compare two formulations: the original particle with no hydrophobic monomer, and a nanoparticle synthesized with increased network hydrophobicity using the cyclohexyl methacrylate co-monomer. As shown from the graphs, the original particle is toxic at both 2 and 24 h of exposure in a range potentially relevant to the conservative concentration needed for delivery (0.1 to 0.26 mg/mL of nanogels). The nanoparticles synthesized with increased hydrophobicity are significantly more inert across all concentrations, regardless of increasing chain length or steric bulk.

A, B The calculated effective concentration of all nanoparticles tested (EC50, shown in mg/mL of nanoparticle) for cytotoxicity shown as a function of nanoparticle pKa estimated from the TNS assay measured by cell viability (open symbols) and proliferation (filled symbols) after (A) 2 h and (B) 24 h exposure. C Hemolytic activity of nanoparticles measured using sheep red blood cells in phosphate buffers at pH 7.4, 6.5, and 5.5, corresponding to extracellular, early endosomal, and late endosomal environments, respectively. Nanoparticles were tested over concentrations ranging from 2 to 2000 µg mL−1; for clarity, hemolysis at a representative concentration (14 µg /ml) is shown. Data represent mean ± s.e.m. (n = 3). D–F Effective concentration (EC 50 mg /mL) for endosomolytic activity, quantified by red blood cell hemolysis, plotted as a function of nanoparticle pKa estimated from the TNS assay at (D) pH 7.4, (E) pH 6.5, and (F) pH 5.5. Data represent mean ± s.e.m. (n = 3).

To summarize the data from all formulations and concentrations tested, the effective concentration of nanogel in mg/mL for a 50% reduction (EC50) in cell viability and proliferation was calculated relative to the positive media control. Ideally, the nanoparticles are inert across all concentrations tested and have little to no effect on cell viability and cell proliferation at both exposure times tested. From Table 2, several formulations with increased hydrophobicity meet the ideal criteria and show minimal cytotoxicity in cell viability and proliferation for both 2- and 24-h exposure times. The formulations with less network hydrophobicity began to show cytotoxicity in a range potentially relevant to the conservative concentration needed for delivery (0.1 to 0.26 mg/mL of nanogels).

The calculated effective concentration of all nanoparticles tested (EC50, shown in mg/mL of nanoparticle) shown as a function of nanoparticle pKa estimated from the TNS assay for both cell proliferation and viability at all exposure times tested is shown in Fig. 7. As expected, the cytotoxicity profiles and calculated EC50 values demonstrate that nanogel pKa plays a prominent role in and has a strong correlation with nanoparticle in vitro compatibility.

The formulations decrease in the extent of toxicity with a decrease in pKa. This trend agrees with the result of shifting pKa to lower values through a more hydrophobic network. The more hydrophobic networks have both a lower pKa and critical pH and are significantly less toxic. As the pKa of the polymer is lowered, the nanoparticle is not capable of disrupting the outer membrane of the cell and rather is able to only induce rupture once compartmentalized in an acidic environment. This is true for both the 2- and 24-hour time points but has a more pronounced effect on cell viability. The dramatic increase in cytotoxicity for the higher pKa formulations demonstrates the impact of a narrow volume swelling range.

Endosomolytic activity

The influence of copolymer composition and network hydrophobicity was analyzed using a whole red blood cell hemolysis assay. In order for the particles to be suitable for intracellular delivery, they must be able to release their cargo and provide a mechanism for endosomal escape and delivery to the site of action. Once nanoparticles are taken up in the cell, they can either by recycled and exocytosed out of the cell or trafficked to organelles.

The intravesicular pH drops along the endocytic pathway, from pH 6.0 to 6.5 in early endosomes to pH 4.5 to 5.5 in late endosomes and lysosomes. Ideally, the nanoparticles will leverage this acidification to facilitate cytosolic delivery. Membrane transport through endosomal compartments can be perturbed by agents that interfere with endosome acidification, such as polymeric weak bases (i.e., 2-(diethylamino)ethyl methacrylate) or by inhibitors of the endosomal proton pump. To this extent, polymers with a buffering capacity between pH 5.2 to 7.0 can mediate their endosomal escape through the proton-sponge effect, where the proton-absorbing polymer induces osmotic swelling of the endosome and its eventual rupture22.

An ex-vivo red blood cell (RBC) hemolysis assay was used to screen the nanoparticles for hemolytic ability30. Briefly, whole RBCs from sheep blood were incubated with the nanoparticles as a function of pH for 1 h at 37 °C. The amount of hemoglobin released from lysed cells was measured, and the percent RBC disruption was relative to positive control samples lysed with 20% Triton X-100. Ideally, the nanoparticles will have very little lysis at physiological conditions (pH 7.4), and maximum lysis in the conditions representing the early and late endosomal compartments (pH 6.5 and 5.5, respectively).

All nanoparticles were tested as a function of concentration from 2 to 2000 µg/mL. As shown in Fig. 7, nanogels with increased hydrophobicity demonstrated hemolytic ability at low pH, with no observed lysis at pH 7.4 at 14 µg/mL. The nanoparticles made with a hydrophobic monomer of increased chain length or steric bulk demonstrate the desired hemolytic ability, where at pH 7.4 we see that the particles with increasing hydrophobicity are inert and non-disruptive, and at pH 6.5 and 5.5 those same particles are now capable of membrane disruption.

To summarize the data from all formulations and concentrations tested, the effective concentration of nanogel in mg/mL to induce 50% lysis (EC50) was calculated relative to the positive lysis control. From Supplementary Table 2, several formulations with increased hydrophobicity meet the ideal criteria. Only at the pH values of the early and late endosome, the formulations with increased network hydrophobicity showed strong endosomolytic activity well below a range potentially relevant to the conservative concentration needed for delivery (0.1 to 0.26 mg/mL of nanogels).

The calculated hemolytic 50% effective concentration values of all nanoparticles tested (EC50, shown in mg/mL of nanoparticle) shown as a function of nanoparticle pKa estimated from the TNS assay for endosomolytic activity is shown in Fig. 7. As expected, the data demonstrate that nanogel pKa plays a prominent role in and has a strong correlation, inverse to that observed with in vitro cytotoxicity.

At the pH of the early endosome (pH 6.5), the hemolytic 50% effective concentration values for butyl, hexyl, 2-ethyl hexyl, tert-butyl, and cyclohexyl methacrylate were all well below 2 µg/mL, more potent than other successful delivery vehicles reported in literature.

Overall, this work explores the fabrication of a novel family of nanoscale hydrogels based on P(DEAEMA-g-PEGMA), with inclusion of hydrophobic moieties in pH-responsive polymer system investigated in systematic fashion. The resulting family of polymer nanoparticles possess tunable pH-response profiles, drug-polymer interactions, cytocompatibility, and endosomolytic activity depending on polymer composition and the choice of increasing hydrophobicity through either increasing n-alkyl methacrylate pendant group chain length or steric bulk.

Varying the type and ratio of n-alkyl methacrylate monomer allows for precise control over the nanogel pKa, critical swelling pH, and onset of swelling. Further, the rational design and characterization of P(DEAEMA)-g-PEGMA networks was necessary for tailoring the cationic nanogel system as a platform for the synchronous and ratiometric delivery of multiple chemotherapeutic agents with varying physicochemical properties in a single carrier. The hydrophilic compound loading is minorly affected by variation in network hydrophobicity, and trends with the volume swelling ratio observed by dynamic light scattering. The hydrophobic loading is influenced by improved interactions between drug and hydrogel and overcomes the decrease in the volume swelling ratio due to enhanced solubility.

The particles were evaluated for the desired biological properties as intracellular delivery vehicles. The cytotoxicity profiles and calculated EC50 values demonstrate that nanogel pKa plays a prominent role in and has a strong correlation with nanoparticle in vitro compatibility. The formulations decrease in the extent of toxicity with a decrease in pKa. The dramatic increase in cytotoxicity for the higher pKa formulations demonstrates the impact of a narrow volume swelling range. Only at the pH values of the early and late endosome, the formulations with increased network hydrophobicity showed strong endosomolytic activity well below a range potentially relevant to the conservative concentration needed for delivery (0.1 to 0.26 mg/mL of nanogels).

Ultimately, the family of nanoparticles can be ranked against criteria for the ideal candidate for targeted intracellular delivery (Supplementary Table 1). This criteria can be broadly described in categories that ensure the leading formulation is: (i) stable and does not aggregate, (ii) has the appropriate size to take advantage of the EPR effect, (iii), is able to intelligently respond to the intracellular environment, (iv) is capable of repeatable, ratiometric drug loading, (v) and does not impart any toxic effects from the vehicle alone. The co-polymer made using the cyclohexyl methacrylate monomer displays the desired properties and response required for intracellular-targeted delivery applications.

Methods

Materials

Poly(ethylene glycol) methyl ether methacrylate (Mn 2080) solution in 50 wt% in water (PEGMA), 2-(diethylamino)ethyl methacrylate (DEAEMA), tetraethylene glycol dimethacrylate (TEGDMA), methyl methacrylate (MMA), ethyl methacrylate (EMA), isopropyl methacrylate (IPMA), tertbutyl methacrylate (tBMA, 98%), phenyl methacrylate (PhenylMA), cyclohexyl methacrylate (CHMA), benzyl methacrylate (BenzylMA), butyl methacrylate (BMA), hexyl methacrylate (HMA), ethylhexyl methacrylate (EHMA), and myristyltrimethylammonium bromide (MyTAB) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Sigma-Aldrich Corporation, St Louis, MO). Irgacure 2959 was obtained from Ciba (Ciba Inc., Basel, Switzerland). Brij 30 and deuterium oxide (99.8% D) were purchased from Acros Organics. Acetone, 1X Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline (DPBS), hydrochloric acid, and sodium hydroxide were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). OVCAR-3 (ATCC® HTB-161™) and RPMI-1640 Medium (ATCC® 30-2001™) were obtained from ATCC (ATCC, Manassas, VA). Insulin from bovine pancreas solution (10 mg/mL insulin in 25 mM HEPES pH 8.2, Catalog I-0516) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, and fetal bovine serum (Corning, Catalog 35010CV) was obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Water used in all experiments was deionized (DI) with a Milli-Q Plus Ultrapure Water System (Millipore) equipped with a 0.22 μm in-line outlet filter. All chemicals were used as received.

Nanoparticle synthesis and purification

Poly(2-(diethylamino) ethyl methacrylate)-g-poly (ethylene glycol methyl methacrylate) (P(DEAEMA)-g-PEGMA) nanoparticles were synthesized via UV-initiated, aqueous emulsion free radical polymerization20. To synthesize nanoparticles, the prepolymerization mixture was prepared by combining DEAEMA (71.0 mol%), PEGMA (7.8 mol%), and the respective hydrophobic co-monomer (21.2 mol%) in a round bottom flask with deionized water. To form the emulsion, Brij 30, a non-ionic surfactant, and MyTAB, a cationic surfactant, were added to the aqueous solution at concentrations of 4 mg/mL and 1.16 mg/mL, respectively. The free radical initiator Irgacure 2925 was added at a ratio of 0.5 wt% of total monomer. The reaction pH was routinely pH 9.5-10.0.

The reagents were mixed by ultrasound for 20 min to form an oil-in-water emulsion, and the emulsion was purged with nitrogen to eliminate free radical scavengers. Subsequently, the emulsion was placed under a UV point source with an intensity of 140 mW/cm2 for 2.5 h with constant stirring (BlueWave 200 Spot Lamp System, Dymax Corporation, Torrington, CT).

The synthesized particles were purified by repeated ionomer collapse and resuspension to remove surfactants and unreacted monomers. Briefly, nanoparticles were titrated to pH 1.0 with 6 N HCl solution and allowed to stir for at least 5 min. The particles were then diluted to 10 v/v% with acetone and centrifuged at 20,000 g for 2–5 min (only until a pellet was formed). The supernatant was removed, and the nanoparticle pellets were resuspended in 0.5 N HCl solution.

The ionomer collapse, centrifugation, and resuspension process were repeated for 4 total cycles. Particles were subsequently dialyzed against distilled water for 7–10 days with the water changed twice daily. For 1H-NMR compositional analysis only, corresponding linear polymers were synthesized using the same process without the TEGDMA crosslinking agent. For FTIR and 1H-NMR analysis, the particle solutions were lyophilized under vacuum at −105 °C for 48 h.

1H-nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy analysis

Nanogel composition was estimated using 1H-Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy. Spectra were obtained using a 400 MHz NMR (Varian Direct Drive 400 or 58 Agilent MR 400) at 25 °C. To determine composition, dried linear polymers were diluted in deuterium oxide at 10–15 mg/mL. Spectra were analyzed using MestReNova 10.0 software via integration of DEAEMA (δ 1.22, 6H), PEGMA2k (δ 3.55ppm, 176H), and the respective hydrophobic monomer peaks.

Attenuated total reflectance fourier transform infrared (ATR-FTIR) spectroscopy analysis

Lyophilized crosslinked polymer nanoparticles were characterized with Attenuated Total Reflectance Fourier Transform Infrared (ATR-FTIR) Spectroscopy (Thermo Scientific Nicolet iS10) with a germanium crystal. Background spectra were collected immediately before each sample and used for background subtraction. In all cases, spectra were averaged over 64 scans with 0.482 cm−1 data spacing.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

Nanoparticle morphology and dry diameter were determined by transmission electron microscopy (FEI Tecnai Transmission Electron Microscope). Solutions of nanoparticles were prepared at 1 mg/mL in distilled water. Samples were negatively stained using 2% PTA (phosphotungstate) at pH 7.0 and prepared on thin bar hexagonal mesh standard thickness, formvar coated copper grids with 600 mesh. The particles were introduced on the grid for 20 s and then wicked dry, followed by a 20 s incubation with the stain.

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) and zeta potential

Nanoparticle hydrodynamic diameter was determined by dynamic light scattering (Zetasizer Nano, Malvern) using 0.5 mg/mL concentration in 1x DPBS (n = 3 per formulation). Each measurement was the average of a minimum of 12 tens second acquisitions. The effective surface charge was determined by zeta potential (Zetasizer Nano, Malvern) using 0.5 mg/mL concentration in 5 mM sodium phosphate (n = 3 per formulation). Both diameter and zeta potential were measured as a function of pH.

Polymer pKa determination

A microwell plate pKa assay based upon 2-(p-toluidinyl) naphthalene-6-sulfonic acid (TNS) was utilized to determine polymer pKa26. This assay used an anionic fluorophore that interacts with cationic charges. As such, minimal fluorescence was observed above the pKa when nanogels were in the uncharged state and fluorescence reached a maximum when cationic charges and hydrophobic interactions dominate. Particles were titrated from pH 4 to 10. Fluorescence was read using a Cytation3 plate reader, and the pKa was determined from the resulting fluorescence titration using a curve-fit analysis in GraphPad Prism.

Loading studies

Loading studies were completed with model hydrophilic and hydrophobic compounds (rhodamine B and fluorescein dyes). Briefly, Stock dye solutions were prepared in 0.1X PBS solution at pH 4.0, with 2 v/v% DMSO, and the nanogels were incubated with the dyes for 24 h at a 10 w/w% ratio. The mixed solutions were placed on the rotary mixer for constant agitation in an oven set to 37 °C. After 24 h, the nanogels collapsed by rapid titration to pH 8.0, and unloaded dye was collected by filtration and analyzed against standard curves using absorbance readings from the BioTek CytationTM 3 plate reader, the data was analyzed by subtracting the average blank measurements and fit to a linear equation and used to interpolate the concentration of all unknown samples. The amount loaded into the nanogels was calculated by subtracting the supernatant concentration from the initial loading concentration and used to determine the encapsulation efficiency.

Cell culture

Human ovarian cancer adenocarcinoma cells (OVCAR-3) were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 0.01 mg/mL insulin from bovine pancreas and fetal bovine serum (FBS) to a final concentration of 20%. OVCAR-3 cells were used between passage 6 and 20. Cells were passaged by washing with pre-warmed Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline (1X DPBS) without divalent cations, and subsequent incubation with 0.25% Trypsin-EDTA at 37 °C. Trypsin was neutralized by equal volume addition of fresh pre-warmed complete medium, and cells were separated by centrifugation. The resulting pellet was suspended in complete medium, and cell count was determined using a TC20™ Automated Cell Counter (Biorad, Catalog 1450102) using Biorad dual chamber cell counting slides, with trypan blue stain for live/dead analysis. The cell suspension was diluted as necessary and added to tissue-culture treated flasks or multi-well plates. OVCAR-3 cells were typically passaged every 7 days at 1:3 ratio with media replenished every 2-3 days.

In vitro cytocompatibility screening

A live cell assay was used to investigate nanogel in vitro cytocompatibility using two commercially available cytotoxicity assays. Stock solutions of polymer were suspended in 1X DPBS without divalent cations, titrated to pH 7.4, and allowed to equilibrate overnight. OVCAR-3 cells were seeded in 96-well plates at 30,000 cells/well and incubated for 48 h prior in 200 μL complete medium. Media was aspirated and cells were washed 2 times with 1X DPBS. Polymer stock solutions at 10 times the final concentration was added to cells for another designated exposure times. After 2- or 24-h exposure time, the media and polymer were aspirated and replaced with a complete medium solution.

MTS assays were performed using the CellTiter 96 AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay kit (Promega Corp., Madison, WI) in which the soluble tetrazolium salt [3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H tetrazolium] (MTS) is reduced to a purple formazan product. The absorbance of the formazan product is proportional to the number of viable cells. Absorbance at 490 nm was recorded after 4 h incubation.

LDH assays were performed using a CytoTox-ONE™ Homogeneous Membrane Integrity Assay (Promega Corp., Madison, WI) to measure release of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) from cells with damaged membranes. Briefly, cells were seeded to 96-well plates and polymer solutions added as previously described. At designated time points, 50 µL aliquots of media was aspirated and combined with 50 µL LDH assay buffer in a black-walled 96-well plate. Following 10 minutes incubation at room temperature, the fluorescence was measured using 530 nm excitation and 590 nm emission wavelengths.

Red blood cell (RBC) hemolysis screening

A whole red blood cell hemolysis assay as a rapid screening approach to approximate endosomolytic ability. Whole red blood cells from sheep in sodium citrate were obtained from Hemostat Laboratories (Dixon, CA) and used for up to one week after receipt. Erythrocytes were isolated from whole blood by three successive washes with freshly prepared 150 mM NaCl. Red blood cells (RBCs) were separated by centrifugation from 10 min at 2000 × g. The supernatant and remaining buffer were carefully aspirated and discarded. After removing the supernatant following the final wash, RBCs were suspended in a volume of 150 mM phosphate buffer identical to that of the original blood aliquot at the pH matching that of the suspended polymers. This solution was diluted 10-fold in 150 mM phosphate buffer to yield an RBC suspension of approximately 5 × 108 cells/mL.

Phosphate buffers (0.15 M) from pH 5.5 to 7.4 were prepared by dissolving predetermined amounts of monosodium phosphate and disodium phosphate in ultrapure DI water. The buffer pH was adjusted as needed using 1 N HCl or 1 N NaOH. The pH values tested in this analysis range from pH 5.5 – pH 7.4; experiments performed at pH 5.5, 6.5, and 7.40. The concentrations tested range from 2–2000 µg/mL of nanogel suspended in 150 mM phosphate buffer at the specified pH.

In a typical experiment, 1 × 108 RBCs were exposed to nanogels at specified concentrations while shaking at 37 °C. Following a 60 min incubation period, samples were centrifuged at 14,500 RPM for 5 min to separate cells and membrane fragments. An aliquot of each sample was transferred to a clear 96-well plate and hemoglobin absorbance was measured at 541 nm. Negative controls (0% lysis) consisted of 150 mM phosphate buffer at experimental pH and positive controls (100% lysis) consisted of RBCs incubated in 20% Triton X-100. The amount of hemoglobin released from lysed cells was measured, and the percent RBC disruption was quantified relative to positive control samples.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Prism 9 (GraphPad Software). Differences were analyzed using two-tailed Student’s t and one-way ANOVA with tukey test. Details of the replicates are noted in the figure legend. For all figures, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001, and n.s. p > 0.05 were used.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Mitchell, M. J. et al. Engineering precision nanoparticles for drug delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 20, 101–124 (2021).

Davis, R., Duggal, I., Peppas, N. A., Gaharwar, A. K. Designing the next generation of biomaterials through nanoengineering. Adv. Mater. Published online July 11, (2025) https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202501761.

Cao, J., Huang, D. & Peppas, N. A. Advanced engineered nanoparticulate platforms to address key biological barriers for delivering chemotherapeutic agents to target sites. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. Elsevier B. V. 167, 170–188 (2020).

Park, K. Facing the truth about nanotechnology in drug delivery. ACS Nano. 7, 7442–7447 (2013).

Blanco, E., Shen, H. & Ferrari, M. Principles of nanoparticle design for overcoming biological barriers to drug delivery. Nat. Biotechnol. Nat. Publ. Group. 33, 941–951 (2015).

Kirtane, A. R., Kalscheuer, S. M. & Panyam, J. Exploiting nanotechnology to overcome tumor drug resistance: challenges and opportunities. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 65, 1731–1747 (2013).

Hua, S., de Matos, M. B. C., Metselaar, J. M., Storm, G. Current trends and challenges in the clinical translation of nanoparticulate nanomedicines: pathways for translational development and commercialization. Front. Pharmacol. 9 https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2018.00790 (2018).

Etheridge, M. L. et al. The big picture on nanomedicine: The state of investigational and approved nanomedicine products. Nanomedicine 9, 1–14 (2013).

He, H., Liu, L., Morin, E. E., Liu, M. & Schwendeman, A. Survey of clinical translation of cancer nanomedicines - lessons learned from successes and failures. Acc. Chem. Res. 52, 2673–2683 (2019).

Sousa de Almeida, M. et al. Understanding nanoparticle endocytosis to improve targeting strategies in nanomedicine. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 5397–5434 (2021).

Donahue, N. D., Acar, H. & Wilhelm, S. Concepts of nanoparticle cellular uptake, intracellular trafficking, and kinetics in nanomedicine. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 143, 68–96 (2019).

Li, X. et al. Multifunctional nanoparticle-mediated combining therapy for human diseases. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. Springer Nature. 2024;9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-023-01668-1.

Wagner, A. M., Spencer, D. S., Peppas, N. A. Advanced architectures in the design of responsive polymers for cancer nanomedicine. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 135 https://doi.org/10.1002/app.46154 (2018).

Torres-Vanegas, J. D., Cruz, J. C. & Reyes, L. H. Delivery systems for nucleic acids and proteins: barriers, cell capture pathways and nanocarriers. Pharmaceutics 13, 428 (2021).

Suk, J. S., Xu, Q., Kim, N., Hanes, J. & Ensign, L. M. PEGylation as a strategy for improving nanoparticle-based drug and gene delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. Elsevier B. V. 99, 28–51 (2016).

Spencer, D. S. et al. Biodegradable cationic nanogels with tunable size, swelling and pKa for drug delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 588, 119691 (2020).

Qiao, Y. et al. Stimuli-responsive nanotherapeutics for precision drug delivery and cancer therapy. WIREs Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 11 https://doi.org/10.1002/wnan.1527 (2019).

Liechty, W. B., Kryscio, D. R., Slaughter, B. V. & Peppas, N. A. Polymers for drug delivery systems. Annu Rev. Chem. Biomol. Eng. 1, 149–173 (2010).

Efthimiadou, E. K., Theodosiou, M., Toniolo, G., Abu-Thabit, N. Y. Stimuli-responsive biopolymer nanocarriers for drug delivery applications. In: Stimuli Responsive Polymeric Nanocarriers for Drug Delivery Applications: Volume 1: Types and Triggers 405–432 (Elsevier, 2018).

Huang, D. et al. Rational design of stimuli responsive nanoparticle systems for the controlled, intracellular delivery of immunotherapeutic and chemotherapeutic agents. J. Controlled Release 384, 113878 (2025).

Fisher, O. Z., Kim, T., Dietz, S. R. & Peppas, N. A. Enhanced core hydrophobicity, functionalization and cell penetration of polybasic nanomatrices. Pharm. Res. 26, 51–60 (2009).

Kato, Y. et al. Acidic extracellular microenvironment and cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 13, 89 (2013).

Forbes, D. C., Creixell, M., Frizzell, H. & Peppas, N. A. Polycationic nanoparticles synthesized using ARGET ATRP for drug delivery. Eur. J. Pharmaceutics Biopharmaceutics. 84, 472–478 (2013).

Kalepu, S. & Nekkanti, V. Insoluble drug delivery strategies: review of recent advances and business prospects. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 5, 442–453 (2015).

Brannon-Peppas, L. & Peppas, N. A. Equilibrium swelling behavior of pH-sensitive hydrogels. Chem. Eng. Sci. 46, 715–722 (1991).

Alabi, C. A. et al. Multiparametric approach for the evaluation of lipid nanoparticles for siRNA delivery. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 12881–12886 (2013).

Amalvy, J. I. et al. Synthesis and characterization of novel pH-responsive microgels based on tertiary amine methacrylates. Langmuir 20, 8992–8999 (2004).

Moriyama, K. & Yui, N. Regulated insulin release from biodegradable dextran hydrogels containing poly(ethylene glycol). J. Controlled Release 42, 237–248 (1996).

Marek, S. R., Conn, C. A. & Peppas, N. A. Cationic nanogels based on diethylaminoethyl methacrylate. Polym. (Guildf.). 51, 1237–1243 (2010).

Evans, B. C. et al. Ex vivo red blood cell hemolysis assay for the evaluation of pH-responsive endosomolytic agents for cytosolic delivery of biomacromolecular drugs. J. Vis. Exp. 50166 https://doi.org/10.3791/50166 (2013).

Acknowledgements

A.M.W. and N.A.P. gratefully acknowledge funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (EB000246, EB012726, EB022025, GM 56321), the NIH/NCI Center for Oncophysics (Grant CT O PSOC U54-CA-143837), the National Science Foundation (DGE-03-33080) and the UT-Portugal Collaborative Research Program. A.M.W. was supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (DGE-1610403), the S.E.S.H.A. Endowed Graduate Fellowship in Engineering, and the Philanthropic Educational Organization Scholar Award. N.A.P. acknowledges financial support from the Cockrell Regent’s Family Chair in Engineering (UT Austin).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.M.W. and N.A.P. conceived the study and developed the methodology. A.M.W., A.L., A.S., A.S. and N.A.-S. performed the investigations and data curation. A.M.W. and I.D and conducted the formal analysis, visualization, and contributed to both the original draft and the review and editing of the manuscript. J.J.R.C. and F.A.C.V. contributed to editing, visualization, and figure preparation. N.A.P. acquired funding and contributed to the review and editing of the manuscript. All authors commented on and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wagner, A.M., Duggal, I., Lawrence, A. et al. Systematic design of polybasic nanogels: influence of hydrophobic monomers on tunable physicochemical and biological properties. npj Biomed. Innov. 3, 8 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44385-025-00058-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44385-025-00058-2