Abstract

This study investigates the dual-track paradox in China’s welfare governance, where formal state-led programs and informal relational strategies coexist and interact. Using the 2021 Chinese Social Survey data (N = 9260), it examines how formal social security participation and informal gift-giving behavior relate to individual life stress. Results indicate that while formal participation is associated with lower stress (β = –0.037, p < 0.001), this effect is significantly weaker among rural residents (interaction β = –0.004, n.s.) and those outside public-sector employment (β = –0.012, n.s.). By contrast, reliance on gift-giving—reported by 5.82% of respondents—is positively associated with higher stress (β = 0.103, p < 0.001), particularly when unsuccessful (β = 0.290, p < 0.001). Perceived fairness shows the strongest negative correlation with stress (r = –0.204, p < 0.001), while interpersonal and government trust offer modest buffering effects. Moving beyond a psychological framing, the study conceptualizes stress as an ontological condition emerging from procedural opacity, moral entanglement, and symbolic exclusion. The results suggest that layered governance shapes unequal access and adds relational and emotional strain to welfare navigation. Policy implications include enhancing procedural transparency, recognizing culturally embedded informal practices, and building institutions that address both material inequality and symbolic disenfranchisement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

China’s welfare regime exemplifies a hybrid governance structure, in which formal institutions and informal practices not only coexist but shape one another. Historically, welfare provision has been deeply embedded in relational infrastructures—Confucian familism, kinship-based obligations, and community reciprocity (Dutton, 1988). Mutual aid, gift-giving, and interpersonal obligations formed a culturally grounded layer of welfare long before the advent of formal social policy (Watson, 2009). Even with institutional modernization, these informal systems have remained resilient, adapting to shifting political-economic conditions rather than being supplanted (Gao et al., 2013; Zhu, 2016).

Formal welfare institutions became most prominent during the Maoist era through the work-unit (Danwei) system, which provided urban state employees with housing, healthcare, pensions, and job security (Davis, 1989). However, this urban-centered model created a bifurcated welfare architecture from the outset, systematically excluding rural residents and informal-sector workers (Huang, 2015; Osburg, 2018). This dual-track configuration—of state entitlements and relational provisioning—became structurally embedded, reinforcing broader patterns of economic dualism and urban-rural segmentation (Lau et al., 2000).

Since 2018, this dualism has intensified. Economic slowdown and renewed emphasis on state-led growth—reflected in the slogan “the state advances, the private sector retreats” (Hillman, 2019)—have widened disparities between institutional insiders and outsiders. Despite rhetoric around “common prosperity,” many citizens, especially rural migrants, face procedural opacity, administrative discretion, and selective inclusion (Ma and Christensen, 2019). For these groups, informal mechanisms remain necessary yet unreliable, deepening relational strain and emotional vulnerability (Liu, 2023).

Rather than framing this configuration as a paradox of incomplete modernization, this study reconceptualizes China’s dual-track welfare as a historically sedimented governance logic. Formal universality is layered atop morally contingent relational systems that are not transitional, but selectively activated across bureaucratic levels and social domains. Institutional ambiguity may function less as a sign of failure than as a mechanism that manages the boundary between entitlement and symbolic inclusion (Gao et al., 2013; Osburg, 2018; Zhu, 2016). This study approaches welfare hybridity in China as a persistent governance logic, rather than a problem of incomplete modernization.

The consequences are not only material but existential. Individuals must perform eligibility within discretionary systems, navigate opaque procedures, and sustain emotionally demanding informal ties (Lu, 2014; Jiang and Wang, 2022). Stress emerges not merely as a psychological symptom but as an ontological condition: the burden of sustaining moral coherence amid institutional inconsistency. This study thus reframes stress as a socially embedded response to normative contradiction—the demand to trust untrustworthy institutions, reciprocate within contingent moral economies, and remain legible in unstable bureaucratic terrains.

These tensions are starkly visible in social phenomena such as Duanqin (断亲)—the deliberate severance of kinship ties (Yi, 2024). Often interpreted as a symptom of individualism, Duanqin reflects deeper structural fatigue: as individuals retreat from kin-based obligations under emotional and economic pressure, networks once seen as adaptive become sources of guilt, stress, and moral dislocation (Zhang, 2020; Xu and Dellaportas, 2021). What was once a buffer against institutional insufficiency now functions as a site of structural entrapment.

This study situates these dynamics within a layered governance framework that moves beyond a binary of state versus society. It conceptualizes welfare as a stratified field, where formal rules and informal obligations operate concurrently but asymmetrically, generating recursive effects (Osburg, 2018; Wu, 2019). Declining trust in formal provision increases dependence on informal ties, which in turn intensify exposure to contingent reciprocity and emotional labor (Smart, 2018; Lipsky, 2010). Over time, citizenship rights become blurred with relational privilege, and entitlement recoded as performance (Lu, 2014).

International comparisons sharpen the distinctiveness of this configuration. Nordic welfare regimes have displaced informal family obligations through procedural transparency and universalistic entitlements, minimizing emotional burdens (Saraceno, 2016). Latin American systems, by contrast, reveal how informalism institutionalizes inequality through personalized access and patronage (Holland and Schneider, 2017). China occupies a third position: formal programs are extensive but unevenly implemented; informal networks are indispensable yet morally taxing. This hybrid formation yields both institutional resilience and systemic ambiguity, making China a critical site for theorizing welfare hybridity not as administrative failure, but as lived contradiction (Wu, 2019).

Against this backdrop, the study addresses three questions: (1) How does the dual-track welfare regime manifest in lived experience, particularly in terms of psychological and ontological stress? (2) How do informal mechanisms, while once adaptive, evolve into structural sources of inequality and emotional burden? (3) What insights can comparative welfare models offer for managing the symbolic and relational tensions embedded in hybrid governance?

To answer these questions, the study integrates nationally representative survey data with a sociological reframing of stress, trust, and fairness as indicators of institutional saturation and symbolic overload. Rather than resolving the dual-track paradox, the study advocates a pragmatic reinterpretation: welfare hybridity should be seen not as a flaw to correct, but as a logic to understand, inhabit, and recalibrate. In doing so, the study contributes to broader debates on informal institutions, state-society relations, and the emotional infrastructures of hybrid welfare governance.

Literature review

Dual-track welfare systems and the symbolic structure of layered governance

Welfare governance in contemporary China reflects a structural dualism that challenges conventional distinctions between formal and informal provision. While formal institutions offer universalistic entitlements grounded in bureaucratic rationality, informal mechanisms persist as culturally embedded access strategies. Earlier scholarship often framed this hybridity as transitional—a remnant of underdevelopment expected to yield to institutional modernization (Rawls, 1991; Osburg, 2018; Jiang and Wang, 2022). More recent perspectives, however, interpret this hybridity as a durable governance logic rather than a temporary compromise (Williams, 2021; Dean, 2024).

Informal strategies such as Guanxi, gift-giving, and discretionary negotiation do not merely supplement formal programs; they constitute a parallel moral economy. These strategies stabilize access in the face of institutional insufficiencies but simultaneously embed it within unequal, culturally sanctioned networks (Smart, 2018; Wu, 2019; Ferguson, 2020). In this configuration, formality and informality are not separate spheres but co-produce symbolic legitimacy, distributing recognition, resources, and obligations through overlapping but stratified logics. Williams (2021) refers to this configuration as relational hybridity, wherein formal rules and informal norms operate jointly through mechanisms of contingent reciprocity and selective exposure.

This interplay exemplifies the logic of layered governance—the institutionalization of ambiguity through the concurrent operation of multiple normative orders (Dean, 2024). In China, policy implementation and administrative control continue to rely heavily on relational mediation (Lipsky, 2010), reinforcing a structure in which access depends as much on moral performance as on legal eligibility. Informality thus emerges not as institutional failure but as a culturally legible infrastructure for navigating selective inclusion.

Drawing on Scott’s (1985, 1990) concepts of “hidden transcripts” and “everyday resistance,” informal welfare behaviors can be read as tacit critiques of formal universality. Individuals navigate bureaucratic opacity through culturally encoded practices—ritualized reciprocity, symbolic gift exchange, and relational tact (Graycar and Jancsics, 2017; Ruan, 2021). While often adaptive, these practices also produce hierarchies of legitimacy and visibility, reinforcing structural vulnerability through morally contingent recognition (Cederberg, 2012).

Yet, the ambivalence of informality must be acknowledged. As Ferguson (2020) observes, relational strategies offer short-term relief while reinforcing long-term dependency. Williams’s (2021) intersectional analysis further reveals how solidarity and reciprocity, while ethically embedded, often deepen inequalities along lines of class, gender, and geography. Informality may both shield and entrap—providing access while institutionalizing moral indebtedness and psychological strain (Sen, 2013; Li, 2018; Dreier and Lake, 2019).

Simultaneously, formal institutions—though rhetorically committed to procedural fairness—are stratified by Hukou regimes, sectoral divides, and regional disparities (Gao et al., 2013). Urban residents and public-sector employees disproportionately benefit from institutional predictability, while rural and informal workers are exposed to administrative discretion and institutional fragility (Barbalet, 2018; Wu, 2019). As such, the formal system legitimizes structural inequality while symbolically preserving a universalistic façade, sustaining governance through selective visibility and asymmetrical recognition (Osburg, 2018).

Welfare, stress, and the symbolic burdens of layered governance

From institutional design to emotional consequence

Recent advances in welfare state research have moved beyond institutional architectures and material redistribution to foreground the emotional, moral, and symbolic dimensions of governance (Fraser, 2008; Barbalet, 2018; Dean, 2024). This “emotional turn” recognizes that the experience of welfare is not merely technical or administrative but existential. Citizens do not simply access benefits—they interpret, feel, and navigate institutions through emotional registers of recognition, trust, and worth (Lister, 2013). As such, stress becomes a critical lens: not as an individual psychological trait, but as a socially produced emotonal state arising from disjunctures between institutional promises and lived realities (Sønderskov and Dinesen, 2016; Ayres, 2022).

In hybrid regimes like China, where formal and informal systems intertwine, the emotional consequences of layered governance are particularly pronounced. Here, stress is not only a signal of resource scarcity but a relational index of symbolic exclusion and normative ambiguity (Lewin-Epstein et al., 2003; Smith, 2010; Wu, 2019; Ruan, 2021). This study builds a conceptual framework that treats stress as an ontological condition of inhabiting stratified welfare logics, and it derives four hypotheses based on distinct but interrelated governance layers: formal institutional justice, informal moral economies, trust infrastructure, and symbolic recognition.

Formal systems and the failure of institutional promise

Modern welfare institutions are typically justified by principles of legal universality and procedural fairness (Rawls, 1991; You, 2012). Yet in practice, these promises are often unevenly realized, particularly in dualized regimes. In China, welfare access is shaped by Hukou classification, employment sector (Huang, 2015), and geographic location (Gao et al., 2013), producing what Esping-Andersen (1999) calls “stratified universalism.” These stratifications generate not only material deprivation but symbolic misrecognition, where individuals are formally included but experientially excluded (Lister, 2013).

Barbalet (2018) notes that in centralized welfare regimes, symbolic coherence is as important as material coverage: the performance of care and order legitimizes the state, even as access remains uneven. Individuals encountering this dissonance may experience stress as a moral dislocation—the emotional cost of being structurally legible but substantively invisible.

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Formal welfare participation is negatively associated with life stress, but this relationship is conditioned by institutional segmentation—particularly urban–rural and public–private divides.

Informal mechanisms and the paradox of relational security

In contexts where formal access is unstable, individuals turn to informal strategies—guanxi, gift-giving, and discretionary favors—as alternative pathways to security (Smart, 2018; Li, 2018; Ruan, 2021). Drawing on these exchanges should not be seen as merely instrumental but as morally saturated acts embedded in systems of obligation, indebtedness, and recognition (Xu and Dellaportas, 2021; Liu, 2023).

Yet this moral economy is inherently ambivalent. Ferguson (2020) argues that while informal practices may humanize distribution, they also reproduce structural dependency and symbolic hierarchies. Williams (2021) further shows that these networks—though appearing solidaristic—intensify inequality along class, gender, and regional lines. In this sense, gift-based access produces what Sen (2013) calls “entrapment by moral reciprocity”: individuals must perform worthiness in emotionally taxing ways, leading to chronic stress, guilt, and relational fatigue.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): Informal coping mechanisms, particularly gift-giving, are positively associated with life stress due to their entanglement in contingent reciprocity and symbolic debt.

Trust, uncertainty, and the limits of buffering

Trust is often theorized as the emotional infrastructure that undergirds institutional stability (Sønderskov and Dinesen, 2016; Institutional trust, in particular, signals belief in the fairness, transparency, and reliability of governance systems. Its absence intensifies perceptions of risk and procedural injustice (Cederberg, 2012; Ma and Christensen, 2019). Interpersonal trust, meanwhile, provides a compensatory resource—but one that is itself structured by inequality and symbolic stratification (Ferguson, 2020).

In hybrid systems, trust becomes a double-edged currency: it can mitigate uncertainty, but it can also signal resignation to institutional failure. Dreier and Lake (2019) suggest that in contexts of chronic opacity, trust becomes emotionally overburdened—tasked with sustaining hope where procedural safeguards fail. This ambivalence limits trust’s buffering capacity and renders its protective effects highly conditional.

Hypothesis 3 (H3): Institutional and interpersonal trust are negatively correlated with stress, but their moderating effects are constrained by institutional fragility and relational inequality.

Fairness, inclusion, and symbolic legitimacy

Finally, perceived fairness—defined as the subjective experience of procedural justice and distributive equity—emerges as a decisive mediator of emotional wellbeing (Lewin-Epstein et al., 2003; Smith, 2010). Research across welfare contexts consistently finds that fairness perceptions often outweigh actual benefit levels in shaping psychological outcomes (You, 2012; Sønderskov and Dinesen, 2016). In hybrid regimes, fairness operates not only as a political value but as a symbolic claim to institutional belonging (Fraser, 2008; Wu, 2019).

Rawls (1991) and Lister (2013) argue that justice requires not only impartiality in outcomes but transparency in procedures. In China, selective visibility—who is seen, heard, and counted by the welfare state—becomes a powerful axis of symbolic inclusion (Li, 2018). Where fairness is absent, individuals may experience stress not from exclusion per se, but from the erasure of their moral worth (Graycar and Jancsics, 2017).

Hypothesis 4 (H4): Perceived fairness is more strongly associated with stress than material inadequacy, highlighting the central role of symbolic recognition in welfare experience.

These four hypotheses articulate a multi-layered model of stress as an outcome of symbolic governance. Drawing from Fraser (2008), and Foucault (1991), this framework understands stress not as a residual psychological state but as a relational signal of institutional saturation, moral burden, and recognition deficit. The emotional experience of welfare is produced not simply by what one receives, but by how one is seen—legally, morally, and symbolically (Sen, 2013; Williams, 2021; Ayres, 2022; Dean, 2024).

This study thus situates stress at the intersection of layered governance and emotional justice, arguing that hybrid welfare systems do not just stratify resources—they distribute uncertainty, emotional labor, and ontological ambiguity. In doing so, the framework contributes to broader debates on informal institutions and the emotional economies of welfare governance under conditions of institutional ambivalence.

Methods

Data

This study draws on data from the 2021 Chinese Social Survey (CSS2021), administered by the Institute of Sociology at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. The CSS employs a nationally representative, multi-stage sampling strategy. First, 151 counties were selected from a pool of 2870 using probability proportional to size (PPS). Within each county, 604 village or neighborhood committees were sampled, followed by 10,268 households identified through systematic residential mapping. One respondent per household was randomly selected. Data were collected using Computer-Assisted Personal Interviewing (CAPI) to enhance accuracy and consistency. After rigorous cleaning procedures, the final analytic sample includes 9260 valid cases from 31 provinces.

Given the sensitivity of certain behaviors, particularly gift-giving, the study cross-validated responses using adjacent survey items and acknowledges potential reporting bias in the interpretation of findings.

Measures

Categorical variables include: (1) Gift-Giving Behavior (1 = yes, 0 = no); (2) Employment Sector (1 = public, 0 = private); (3) Gender (1 = male, 0 = female); (4) Hukou Type (1 = urban, 0 = rural); (5) Marital Status (six categories, dummy-coded); and (6) Region (eastern, central, western).

Ordinal variables include: Education Level (1 = no formal education to 8 = doctoral degree) and Local Socioeconomic Status (SES, 1 = lowest to 5 = highest). These are treated as continuous variables to preserve analytical parsimony, with robustness checks confirming consistent results under categorical specifications.

Continuous variables include: Life Stress Index (dependent variable); Social Security Participation Index; Gift-Giving Success Rate; Fairness Perception Index; Interpersonal Trust Index; Government Trust Index; Age (in years).

Dependent variable

The Life Stress Index captures cumulative stress across 13 household domains, including housing quality, education expenses, caregiving burdens, healthcare costs, employment instability, family conflict, ceremonial obligations, financial pressure, crime, environmental hazards, and others. Respondents answered each item dichotomously (1 = yes, 0 = no). The index is calculated as the mean of affirmative responses, yielding a scale from 0 (no stress) to 1 (maximum cumulative stress), adapted from multidimensional stress measures (Roohafza et al., 2011) and contextualized to Chinese social pressures (Anderloni et al., 2012).

Key independent variables

Social Security Participation Index

Measures participation in six formal programs—pensions, medical insurance, unemployment, work injury, maternity, and minimum living guarantee. Each is coded 1 if enrolled and 0 otherwise; the index reflects the average across programs (Hernandez and Pudney, 2007).

Gift-giving behavior

Captures whether respondents gave gifts to facilitate access across six domains (medical care, education, job search, promotions, litigation, business). If any behavior was reported, the variable is coded 1; otherwise, 0.

Success rate

For those who reported gift-giving, outcomes were rated on a 3-point scale (3 = success, 2 = pending, 1 = failure), averaged across applicable domains (Millington et al., 2005).

Fairness Perception Index

Self-reported perception of fairness in resource distribution, scored from 1 (very unfair) to 10 (very fair).

Interpersonal Trust Index

Measured on a 10-point scale (1 = low to 10 = high).

Government Trust Index

Calculated as the average of trust scores for central, county, and township governments (1 = low to 4 = high).

Employment sector

Public sector includes government, public institutions, state-owned enterprises, and the military (coded 1); private sector includes private firms, foreign companies, non-profits, and self-employment (coded 0).

Control variables

To address potential confounders of life stress (Businelle et al., 2014), the models control for: (1) Age (continuous); (2) Gender; (3) Marital status (dummy-coded); (4) Hukou type; (5) Region; (6) Education level; (7) Local SES (self-rated, 5-point scale).

Statistical modeling

Three models were estimated using Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression with robust standard errors:

Baseline model

Tests the association between formal welfare participation and life stress.

where \({X}_{i}\) represents control variables for demographic and socioeconomic characteristics.

Interaction model

Includes Social Security × Gift-Giving and Social Security × Success Rate terms to examine joint effects.

Moderation model

Tests whether trust and fairness moderate the association between gift-giving and stress.

All models passed multicollinearity tests (VIF < 2). Sensitivity analyses—including ordered logit models and subgroup analyses by Hukou and employment sector—confirmed the robustness of the results.

Causal inferences are not made due to the cross-sectional design. Observed associations may reflect reciprocal or unobserved dynamics; stress may arise from prior experiences that also shape welfare behavior. Accordingly, interaction effects are interpreted as conditional associations, not causal mechanisms.

Methodological reflexivity

While this study maps structural patterns between welfare governance and reported stress, it does not capture how stress is lived and interpreted. In layered regimes, individuals are not only materially constrained but symbolically exposed. Variables like gift-giving and fairness, though modeled quantitatively, also carry emotional and moral weight. A gift may reflect obligation or social hope; fairness may signal disappointment or exclusion.

Quantitative models reveal distributional patterns but remain silent on how people make sense of institutional ambiguity. This study thus offers a partial view—structurally grounded, but analytically distant from the lived narratives that shape and sustain emotional burden.

Findings

Descriptive analysis: mapping the dual-track structure through formal and informal indicators

Descriptive statistics (Table 1) offer a snapshot of China’s dual-track welfare regime. The Life Stress Index (mean = 0.212, S.D. = 0.194) indicates moderate overall stress levels, with notable variation across respondents—suggesting differentiated exposure to welfare-related vulnerability. The Social Security Participation Index (mean = 0.242, S.D. = 0.221) is relatively low, confirming the partial and uneven nature of institutional coverage. This limited range (0–1) reflects structural inequalities in access to formal welfare, especially for rural residents and individuals employed outside the public sector—aligning with previous findings on selective institutional inclusion (Osburg, 2018; Jiang and Wang, 2022).

Turning to informal mechanisms, gift-giving behavior was reported by just 5.82% of respondents. While this suggests infrequency, the number is likely deflated due to survey sensitivity and social desirability concerns. Among those who did report gift-giving, the Success Rate is strikingly low (mean = 0.048, S.D. = 0.212), showing the fragility and unpredictability of relational strategies. The data suggest that such practices are associated with uncertain outcomes and emotionally ambiguous expectations. Rather than functioning as stable coping mechanisms, they serve as performative acts with contested legitimacy. These findings resonate with and Ferguson’s (2020) analyses of the psychological burden and moral ambiguity of informal reciprocity under institutional opacity and material precarity.

Trust indicators add further nuance. The Interpersonal Trust Index (mean = 6.691, S.D. = 2.170, on a 10-point scale) reflects relatively high reliance on personal networks. In contrast, the Government Trust Index (mean = 3.107, S.D. = 0.891, on a 4-point scale) displays greater variability, pointing to inconsistent confidence in formal governance structures. Together, these patterns suggest continued dependence on informal social infrastructures—albeit infrastructures whose efficacy and legitimacy remain contingent and morally unstable.

Distributional patterns further reflect institutional fragmentation. Among respondents reporting employment sector status (N = 3958), only 28% were employed in the public sector, while 72% worked in the private or informal economy. Public-sector affiliation likely correlates with more stable welfare access. Similarly, Hukou stratification persists: just 34.74% of respondents held urban Hukou, while 65.26% were registered as rural. These institutional alignments—both employment and registration status—are deeply tied to differences in stress exposure, trust levels, and welfare entitlements.

Finally, the Fairness Perception Index (mean = 6.990, S.D. = 2.070) reflects moderate perceived distributive justice but with considerable dispersion. This heterogeneity suggests uneven evaluations of fairness across socio-institutional groups. It reinforces the conceptualization of welfare governance in China as layered and stratified—where individuals’ perceived positions within both formal institutions and informal moral economies shape their emotional experience of inclusion, legitimacy, and symbolic worth.

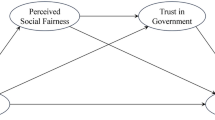

Correlation patterns: structural differentiation and symbolic exposure

Bivariate correlations (Table 2) further illuminate the relational dynamics of China’s dual-track welfare system. Perceived fairness exhibits the strongest negative association with stress (r = −0.204, p < 0.001), revealing the psychological and symbolic importance of distributive legitimacy. Even in contexts where formal entitlements are limited, a subjective sense of fairness appears to function as a cognitive and emotional buffer against perceived exclusion and institutional neglect (Lewin-Epstein et al., 2003; Wu, 2019).

By contrast, gift-giving behavior is positively correlated with higher stress levels (r = 0.103, p < 0.001), and this effect is amplified among those reporting low success rates (r = 0.075, p < 0.001). These findings lend empirical support to theoretical accounts that portray informal reciprocity not merely as adaptive behavior, but as a source of relational strain, moral complexity, and symbolic vulnerability (Sen, 2013; Xu and Dellaportas, 2021). In uncertain governance environments, gift-giving may exacerbate stress by demanding emotional labor without guaranteeing return or recognition—thereby transforming moral exchange into psychological burden.

Both interpersonal trust (r = −0.147, p < 0.001) and institutional trust (r = −0.136, p < 0.001) also correlate negatively with stress, although their effects are weaker than that of fairness. These patterns suggest that trust functions as a secondary emotional resource—providing modest psychological support in navigating institutional uncertainty. However, its protective effects are likely constrained in settings where access remains contingent, opaque, and relationally mediated.

Lastly, public-sector employment is negatively associated with stress (r = −0.127, p < 0.001), further affirming the stabilizing role of institutional affiliation. As prior literature suggests, public-sector workers are more likely to experience procedural clarity, benefit predictability, and symbolic alignment with the state (Gao et al., 2013).

Institutional welfare and embedded stratification

Regression results (Table 3) reveal a clear but contingent relationship between formal welfare participation and life stress. In the baseline model, higher social security participation is significantly associated with lower stress (β = −0.037, p < 0.001). However, this association becomes statistically insignificant (β = −0.012) once employment sector is included, indicating that the protective effect of formal institutions is conditional on public-sector affiliation. These results highlight the selective absorption of formal entitlements, where institutional protection is unevenly realized across occupational hierarchies (Hillman, 2019).

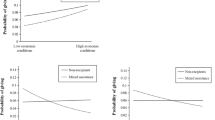

Further nuance emerges in Model 3. Urban Hukou holders report significantly lower stress (β = −0.065, p < 0.001), while the interaction term for rural Hukou and formal participation is non-significant (β = −0.004). This indicates that rural residents derive limited psychological benefit from formal participation, consistent with prior findings on geographically stratified access (Watson, 2009; Shen and Williamson, 2010). Overall, these results underscore how sectoral and spatial hierarchies mediate the experience of “universal” welfare, reproducing embedded stratification within formal systems.

Informal strategies: adaptive or entrapping?

Regression results in Table 4 shift focus to informal coping mechanisms. Gift-giving behavior is positively associated with increased life stress (β = 0.103, p < 0.001), suggesting that while relational strategies may be culturally embedded, they carry emotional and psychological costs (Ferguson, 2020). Model 5 disaggregates this effect: individuals reporting low success in gift-based exchanges exhibit markedly higher stress (β = 0.290, p < 0.001), compared to those reporting high success (β = 0.081, p < 0.001). These findings demonstrate the contingent nature of informal coping—effective only under specific, often rare, conditions of successful reciprocity.

Notably, formal welfare participation moderates the burden of failed informal efforts. Among those with low gift-giving success, participation in formal programs significantly buffers stress (interaction β = −0.440, p < 0.001). This suggests that institutional mechanisms, while limited in general, provide meaningful relief when informal channels falter. However, when informal exchanges are perceived as successful, formal participation has no significant additional benefit (interaction β = −0.007, n.s.), illustrating a substitutive logic: informality displaces, rather than complements, formality under conditions of perceived effectiveness.

Trust: modest buffer, structural constraint

As shown in Table 5, both government trust (β = −0.017, p < 0.001) and interpersonal trust (β = −0.009, p < 0.001) are negatively associated with stress. This suggests that trust functions as a modest psychological resource. However, interaction terms indicate that trust offers limited moderation. The interaction between government trust and gift-giving is not statistically significant (β = −0.009), and the interaction with interpersonal trust is only marginally significant (β = −0.009, p < 0.05). These weak effects suggest that trust alone cannot meaningfully alter the emotional burdens of navigating contingent relational obligations.

In fragmented welfare environments, trust appears constrained by structural exposure: it may ease individual anxiety but cannot resolve the deeper contradictions of symbolic uncertainty and procedural opacity that accompany informal reliance (Cederberg, 2012; Dreier and Lake, 2019).

Fairness and symbolic recognition

Table 6 examines the role of perceived fairness. As expected, higher fairness perceptions significantly predict lower stress (β = −0.016, p < 0.001). Strikingly, once fairness is included in the model, the previously significant effect of social security participation disappears (β = −0.050, p = 0.257). This suggests that the emotional efficacy of formal programs is mediated not by objective inclusion, but by subjective perceptions of justice. Welfare participation, in itself, does not guarantee psychological relief—feeling fairly treated does.

These findings carry important implications: they emphasize that symbolic justice, rather than material coverage alone, plays a central role in shaping emotional responses under layered welfare governance. Moreover, gift-giving continues to predict increased stress (β = 0.109, p = 0.013), while urban Hukou retains its protective association (β = −0.019, p = 0.001). These patterns reflect the co-production of psychological vulnerability by formal and informal systems—not only through resource inequality but also through misrecognition and procedural exclusion (Zhu, 2016; Wu, 2019; Zhang, 2020).

Robustness checks: validating layered vulnerability

Robustness tests (Table 7) confirm the stability of core results. An Ordered Logit Model reproduces key findings: formal welfare participation is associated with reduced stress (β = −0.335, p < 0.001), while gift-giving is strongly associated with elevated stress (β = 1.551, p < 0.001). Subsample analyses also validate spatial and sectoral asymmetries. Among urban residents, formal participation has a stronger stress-reducing effect (β = −0.077, p < 0.001) than among rural residents (β = −0.062, p < 0.001). At the same time, gift-giving is more commonly reported by urban respondents (β = 0.210, p < 0.001), possibly reflecting intensified pressures in competitive urban bureaucratic environments.

Trust interaction models offer moderate confirmation. Government trust modestly enhances the buffering effect of formal participation (β = −0.029, p < 0.001), but this remains a secondary effect. Importantly, the correlation between informal reliance and stress remains significant even under conditions of high trust. This suggests that institutional legitimacy and symbolic exposure operate through distinct mechanisms. Trust can stabilize individual expectations—but it does not eliminate the emotional contradictions embedded in navigating layered welfare systems.

Discussion

The empirical findings of this study offer a multi-layered portrait of China’s welfare governance, where formal participation is associated with lower stress only in specific institutional contexts, and informal strategies appear linked to heightened emotional strain. These patterns do not merely affirm the existence of welfare dualism—they illuminate a deeper logic of structured differentiation and controlled ambiguity that defines how welfare is experienced across institutional layers.

Conditional protection and symbolic exposure

Descriptive statistics show moderate life stress (mean = 0.212) alongside limited social security coverage (mean = 0.242), suggesting that institutional incompleteness is a common structural condition. However, regression results (Table 3) reveal that the association between formal participation and reduced stress is neither robust nor evenly distributed. This association appears stronger among urban hukou holders and attenuated among rural residents, echoing longstanding scholarship on Hukou-based fragmentation (Shen and Williamson, 2010; Wu, 2019; Huang, 2015). Similarly, once employment sector is controlled, the association between formal welfare and reduced stress becomes insignificant—suggesting that institutional proximity to the public sector remains key to experiencing the intended benefits of social security (Davis, 1989; Gao et al., 2013).

This conditionality reflects what Barbalet (2018) and Ferguson (2020) describe as institutional proximity as symbolic capital—the idea that benefits are not merely distributed materially but mediated through culturally and politically salient signs of belonging. The Hukou system and sectoral hierarchies constitute more than administrative filters: they encode assumptions of legitimacy, trustworthiness, and inclusion (Watson, 2009; Lu, 2014). In this sense, China’s welfare architecture mirrors the moral economy of distribution, whereby entitlement is not only formalized through law but also socially performed through institutional alignment and symbolic visibility (Rawls, 1991; Fraser, 2008; Smart, 2018).

Stress, then, should not be interpreted purely as a psychological reaction to need deprivation. Drawing from Sønderskov and Dinesen (2016) and Businelle et al. (2014), stress in this context operates as an emotional signal of procedural ambiguity and ontological insecurity. As Barbalet (2018) notes, emotional responses to welfare systems are shaped by how systems render individuals intelligible or obscure. For marginalized groups—such as rural migrants, informal-sector workers, or the Danwei-disconnected—formal institutions may appear opaque, inaccessible, and morally indifferent (Osburg, 2018; Jiang and Wang, 2022).

This layered exposure aligns with Dean’s (2024) argument that hybrid governance regimes rely on calibrated ambiguity, where rights are neither fully withheld nor consistently granted, but ambiguously maintained. Individuals must navigate “zones of partial recognition” where eligibility fluctuates depending on administrative discretion, political visibility, and institutional trust (Lipsky, 2010; Holland and Schneider, 2017). This resonates with Scott’s (1990) concept of hidden transcripts, whereby citizens publicly comply with the system while privately cultivating narratives of distrust, frustration, and exclusion.

In such settings, ontological insecurity—here to refer to social worth and moral legibility—becomes a central emotional outcome. As Sen (2013) and Williams (2021) argue, welfare exclusion generates not only material disadvantage but symbolic harm: a denial of recognition, status, and collective belonging. Hence, stress emerges as an emotional corollary of stratified symbolic inclusion.

Far from signifying implementation failure, this institutional design reflects what Ferguson (2020) calls the politics of distribution without equality. Universalist rhetoric persists, but the reality is governed by strategic narrowing, wherein access is concentrated around specific groups that maintain alignment with the state’s ideological, organizational, or demographic priorities (Hillman, 2019; Ma and Christensen, 2019). Urban registration, public-sector affiliation, and perceived administrative docility often function as gateways to legitimacy and benefit—leaving others in a state of symbolic precarity.

Informal coping and symbolic overexposure: the ambivalence of gift-giving

Empirical findings reveal the complex and often counterproductive role of gift-giving within China’s dual-track welfare regime. While commonly perceived as culturally legitimate and morally acceptable, gift-giving is significantly associated with elevated life stress (β = 0.103, p < 0.001, Table 4). Despite being reported by only 5.82% of respondents—a figure likely suppressed by self-censorship (Graycar and Jancsics, 2017)—the statistical signal is robust. Informal strategies, far from alleviating vulnerability, appear to amplify emotional strain, consistent with Titmuss’s (2019) concept of the moral cost of reciprocity under scarcity.

This contradiction is deepened by the low success rate of gift-giving attempts (mean = 0.048, Table 1), which points to high failure rates, interpretive ambiguity, and relational fragility. Even when perceived as successful, the buffering effect is modest (β = 0.081, p < 0.001), while unsuccessful exchanges correlate with markedly higher stress (β = 0.290, p < 0.001). Informal strategies offer uncertain relief and may carry emotional and symbolic costs (Millington et al., 2005; Smart, 2018).

Gift-giving operates beyond transactional logic. As Smart (2018) and Ferguson (2020) suggest, it is better understood as a ritualized negotiation of symbolic inclusion. Individuals offer gifts not only to gain access but to perform deference, signal loyalty, and assert moral legibility within selectively enforced bureaucracies. These performances constitute semiotic labor—emotionally charged efforts to secure conditional recognition under uncertain institutional regimes (Foucault, 1991; Lipsky, 2010).

From this view, gift-giving is less about outcomes than about signaling proximity to informal networks of discretion and obligation (Lister, 2013; Barbalet, 2018). When reciprocity fails, the consequences are not merely instrumental but symbolic—a rupture in one’s perceived standing within a moral economy of exchange (Smith, 2010; Sen, 2013).

This symbolic reading helps explain why informal strategies persist despite their emotional cost. In contexts of institutional fragmentation, individuals rely on relational infrastructures that—though fragile—remain socially intelligible and morally resonant (Cederberg, 2012; Ayres, 2022). The improvisational nature of these exchanges is itself socially meaningful: it is how individuals appear as moral actors in worlds where procedural clarity is absent and entitlement must be signaled rather than assumed (Fraser, 2008; Holland and Schneider, 2017).

Contemporary socio-emotional pressures further intensify this burden. Practices like Duanqin (断亲, “cutting off kin”), increasingly prevalent in overburdened family networks, reflect emotional exhaustion and retreat from reciprocal obligations once seen as sacred (Zhang, 2020; Yi, 2024). Within this context, gift-giving becomes a residue of performative trust—a symbolic effort to sustain relational credibility in an atmosphere of pervasive distrust (You, 2012; Ma and Christensen, 2019). Its breakdown is experienced not merely as transactional failure but as moral rejection—a delegitimization of one’s worth in an unequal normative order.

Rather than interpreting gift-giving as a failed adaptation to weak institutions, the findings suggest that such practices are structurally induced. The absence of dependable rules and the opacity of formal eligibility create conditions under which informal coping becomes simultaneously necessary and hazardous (Watson, 2009; Gao et al., 2013). These practices fill governance vacuums while exposing individuals to moral disappointment, emotional depletion, and symbolic alienation (Businelle et al., 2014; Dreier and Lake, 2019).

Trust, fairness, and symbolic inclusion in layered governance

The empirical results suggest that China’s welfare dualism is sustained not only through material distribution or institutional segmentation, but through a deeper symbolic architecture—one embedded in perceptions of legitimacy, recognition, and moral worth. Correlation patterns (Table 2) show that perceived fairness has the strongest negative association with life stress (r = −0.204, p < 0.001), exceeding that of government trust (r = −0.136) and interpersonal trust (r = −0.147). This gradient highlights a key insight: subjective evaluations of procedural justice may shape emotional well-being more consistently than institutional participation alone (Lewin-Epstein et al., 2003; Smith, 2010; Sønderskov and Dinesen, 2016).

Regression models reinforce this pattern. Once fairness is included (Table 6), the previously significant association between formal social security participation and lower stress becomes statistically insignificant (β = −0.050, n.s.). This suggests that perceived justice—not institutional enrollment per se—shapes how individuals interpret their standing within welfare structures (Rawls, 1991; Fraser, 2008; Lister, 2013). Welfare, in this light, functions not only as a redistributive mechanism, but as a moral economy—a domain where symbolic inclusion and exclusion are continually negotiated (Williams, 2021; Dean, 2024).

Meanwhile, the moderating role of trust appears limited. Although both institutional trust and interpersonal trust correlate negatively with stress, their interaction with informal coping behaviors—specifically gift-giving—yields weak or non-significant results (Table 5). The interaction between government trust and gift-giving is statistically insignificant; interpersonal trust shows only a marginal effect (β = −0.009, p = 0.054). These findings are consistent with arguments that trust, especially in hybrid governance settings, is structurally constrained and relationally uneven (Cederberg, 2012; Dreier and Lake, 2019; Ma and Christensen, 2019).

As Williams (2021) and Ayres (2022) argue, trust in such systems is not a universally available emotional resource—it is a morally situated and contingent orientation, shaped by one’s position within hierarchies of recognition and access. In contexts marked by procedural ambiguity and selective enforcement, trust becomes transactional: it is sustained where symbolic inclusion is affirmed, but weakens where individuals must rely on relational cues and discretionary pathways (Lu, 2014; Smart, 2018). In such settings, stress may reflect not merely unmet needs, but symbolic misrecognition—the feeling of being visible only as a supplicant, not as a rights-bearing citizen (You, 2012; Sen, 2013).

What appears paradoxical—continued reliance on informal exchange within a formal welfare regime—is, in fact, a rational adaptation to layered governance. Individuals learn to optimize within regimes where relational competence matters as much as procedural conformity (Gao et al., 2013; Hillman, 2019). Trust alone cannot dissolve this paradox, nor can expanding coverage without addressing symbolic inequality. As Fraser (2008) and Dean (2024) emphasize, legitimacy rests not merely on redistribution, but on recognition—the affirmation of moral worth within systems of governance.

In this sense, stress emerges not simply from scarcity, but from moral ambiguity—from having to signal need, perform gratitude, and negotiate worth under conditions of contingent recognition. It is a relational expression of navigating inconsistent bureaucratic expectations and uncertain symbolic inclusion (Businelle et al., 2014; Barbalet, 2018).

Comparative insights: layered hybridity and global forms of governance exposure

China’s dual-track welfare system—where formal entitlements coexist with informal practices—has often been framed as paradoxical. Yet in comparative perspective, such hybridity is neither unique nor anomalous. It reflects a broader class of governance regimes where institutional ambiguity and symbolic misrecognition are routine, not exceptional (Fraser, 2008; Ferguson, 2020; Dean, 2024).

Nordic systems, grounded in transparency and universalism, reduce the need for informal navigation. Stress there often stems from unmet expectations of equality rather than procedural opacity (Lister, 2013; Saraceno, 2016). In contrast, Latin American regimes normalize informal brokerage, where personal networks structure access, producing enduring symbolic hierarchies (Holland and Schneider, 2017; Dreier and Lake, 2019).

China occupies a third path: its welfare programs are expansive but selectively implemented. Informality—manifested in gift-giving—is not residual but adaptive: a semiotic strategy for navigating bureaucratic ambiguity (Li, 2018; Ruan, 2021). As Ferguson (2020) argues, informality here acts as a “moral technology”—granting conditional visibility while imposing emotional risk.

Drawing on Foucault’s (1991) concept of governmentality, this hybrid configuration reflects not administrative failure but controlled ambiguity. Rules are known but unevenly enforced; inclusion is contingent on performed loyalty and relational compliance (Barbalet, 2018; Smart, 2018). Individuals are expected to perform trust, gratitude, and compliance without stable procedural anchors, rendering stress an index of governance exposure, not merely material precarity (Businelle et al., 2014; Williams, 2021). Under such conditions, individuals must remain legible across overlapping systems of recognition—where stress emerges not from lack alone, but from navigating unstable expectations and moral obligations (Watson, 2009; Yi, 2024).

Policy implications: institutionalizing symbolic inclusion

Recognizing that China’s dual-track welfare configuration is structurally embedded rather than transitional, policy interventions should shift from attempting to eliminate informality toward managing its consequences and recalibrating its coexistence with formal systems.

On the one hand, administrative transparency could be reoriented toward symbolic clarity. Real-time digital systems that display eligibility status, discretionary rules, and appeal procedures may reduce uncertainty and help prevent overreliance on informal negotiation. Yet clarity is not only legal—it is relational. Interfaces that make procedures intelligible in moral and emotional terms may do more to reduce symbolic confusion than abstract legal access alone.

On the other hand, formal systems might better accommodate informal moral intermediaries. Models such as “reciprocal trust zones”—local councils or community-appointed ombuds bridging bureaucratic and relational authority—could help translate informal reciprocity into recognized participation, mitigating reputational and affective risks without fully displacing culturally embedded practices.

Importantly, these interventions are not intended to resolve the dual-track paradox, but to stabilize expectations, reduce emotional ambiguity, and enhance predictability in moral and institutional interactions. In this view, welfare is not merely a matter of coverage or delivery, but of symbolic coherence—a structure through which inclusion must be both practiced and perceived.

Limitations and directions for future research

This study has several important limitations that constrain the interpretation and generalizability of its findings.

First, the analysis is based on cross-sectional survey data, which limits the ability to make causal claims. Although statistically significant associations are identified, the temporal direction of these relationships remains indeterminate. It is possible, for example, that individuals under greater stress are more likely to resort to informal strategies such as gift-giving, rather than the reverse.

Second, several key variables—such as gift-giving behavior, fairness perception, and institutional trust—are based on self-reported measures and may be influenced by social desirability bias or regional variation in interpretive norms. Gift-giving in particular is context-dependent, and its moral valence may differ across social groups and policy domains.

Third, the dataset excludes some of the most precarious populations, including economically inactive individuals, informal caregivers, and those disconnected from both formal institutions and social networks. As a result, the structural and symbolic burdens faced by these groups may be underrepresented in the analysis.

Fourth, while the study uses a multi-item stress index to capture subjective wellbeing, it cannot account for the complex emotional or narrative processes through which individuals interpret institutional ambiguity and moral obligation. The symbolic weight of informal reciprocity, procedural opacity, or failed recognition often exceeds what can be inferred from quantitative indicators alone.

Finally, the analysis is grounded in the Chinese welfare context, which is shaped by unique institutional legacies, cultural norms, and political-administrative structures. Although the theoretical framework of layered governance may have comparative relevance, the empirical findings should not be generalized across welfare systems without careful contextual translation.

Future research should pursue longitudinal and qualitative approaches to better understand how individuals experience and respond to hybrid welfare regimes over time. Ethnographic studies, narrative interviews, and discourse analysis could complement survey data by revealing how stress is lived, narrated, and morally negotiated in contexts where recognition is unstable and inclusion contingent.

Conclusions

This study reexamines China’s dual-track welfare system as a layered governance formation in which formal institutions and informal practices operate concurrently but unequally. While formal participation is associated with lower reported stress, this effect is uneven and conditional—primarily benefiting those with institutional proximity, such as urban Hukou holders and public-sector employees. Informal strategies like gift-giving, by contrast, are associated with higher stress levels, particularly when outcomes are uncertain or unsuccessful. Among all predictors, perceived fairness exhibits the strongest and most consistent association with stress reduction.

These findings do not support a deterministic link between welfare form and psychological outcome. Rather, they suggest that individuals experience stress through the symbolic contradictions of governance—navigating opaque procedures, performing eligibility, and absorbing relational uncertainty. The dual-track system imposes not only material disparities but also emotional and moral burdens that remain underacknowledged in dominant policy discourse.

Policy implications include the need to enhance procedural clarity and symbolic inclusiveness, particularly for those excluded from stable institutional channels. Recognizing the affective dimensions of welfare navigation—how people interpret, endure, and improvise under conditions of partial recognition—may help recalibrate welfare governance beyond technical coverage toward relational accountability. Future research should further explore how emotional distress is shaped not only by structural exclusion but by the semiotic labor of remaining visible and legitimate within layered systems.

Data availability

The data utilized in this study were obtained from the 2021 National Social Survey provided by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS). These data are publicly available and can be accessed upon registration and application through the official CASS Social Science Research Center website: http://csqr.cass.cn/project/dataExplore/6406f9d0ba08b693fbfb7334/dataSet/641c18a174d23097a3bc75e8/basic/info. Access to the dataset requires creating an account and submitting a data usage request as per the platform’s guidelines.

References

Anderloni L, Bacchiocchi E, Vandone D (2012) Household financial vulnerability: an empirical analysis. Res Econ 66(3):284–296

Ayres S (2022) A decentred assessment of the impact of ‘informal governance’ on democratic legitimacy. Public Policy Adm 37(1):22–45

Barbalet J (2018) Guanxi as social exchange: emotions, power and corruption. Sociology 52(5):934–949

Businelle MS, Mills BA, Chartier KG, Kendzor DE, Reingle JM, Shuval K (2014) Do stressful events account for the link between socioeconomic status and mental health? J Public Health 36(2):205–212

Cederberg M (2012) Migrant networks and beyond: exploring the value of the notion of social capital for making sense of ethnic inequalities. Acta Sociol 55(1):59–72

Davis D (1989) Chinese social welfare: policies and outcomes. China Q 119:577–597

Dean H (2024) Sociality: social rights and human welfare. Taylor & Francis, London

Dreier SK, Lake M (2019) Institutional legitimacy in sub-Saharan Africa. Democratization 26(7):1194–1215

Dutton M (1988) Policing the Chinese household: a comparison of modern and ancient forms. Econ Soc 17(2):195–224

Ferguson J (2020) Give a man a fish: reflections on the new politics of distribution. Duke University Press, Durham

Foucault M (1991) The Foucault effect: studies in governmentality. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Fraser N (2008) Abnormal justice. Crit Inq 34(3):393–422

Gao Q, Yang S, Li S (2013) The Chinese welfare state in transition: 1988–2007. J Soc Policy 42(4):743–762

Graycar A, Jancsics D (2017) Gift giving and corruption. Int J Public Adm 40(12):1013–1023

Hernandez M, Pudney S (2007) Measurement error in models of welfare participation. J Public Econ 91(1–2):327–341

Hillman B (2019) The state advances, the private sector retreats. In: China story yearbook 2018: power. ANU Press, Canberra, pp 295–309

Holland AC, Schneider BR (2017) Easy and hard redistribution: the political economy of welfare states in Latin America. Perspect Polit 15(4):988–1006

Huang X (2015) Four worlds of welfare: understanding subnational variation in Chinese social health insurance. China Q 222:449–474

Jiang A, Wang P (2022) Governance and informal economies: informality, uncertainty and street vending in China. Br J Criminol 62(6):1431–1453

Lau LJ, Qian Y, Roland G (2000) Reform without losers: an interpretation of China’s dual-track approach to transition. J Polit Econ 108(1):120–143

Lewin-Epstein N, Kaplan A, Levanon A (2003) Distributive justice and attitudes toward the welfare state. Soc Justice Res 16(1):1–27

Li L (2018) The moral economy of guanxi and the market of corruption: networks, brokers and corruption in China’s courts. Int Polit Sci Rev 39(5):634–646

Lipsky M (2010) Street-level bureaucracy: dilemmas of the individual in public service. Russell Sage Foundation, New York

Liu C (2023) The even darker side of gift-giving: understanding sustained exploitation in family consumption system. Mark Theory 23(4):709–723

Lu J (2014) Varieties of governance in China: migration and institutional change in Chinese villages. Oxford University Press, New York

Lister A (2013) Reciprocity, relationships, and distributive justice. Soc Theory Pr 39(1):70–94

Ma L, Christensen T (2019) Government trust, social trust, and citizens’ risk concerns: evidence from crisis management in China. Public Perform Manag Rev 42(2):383–404

Millington A, Eberhardt M, Wilkinson B (2005) Gift giving, guanxi and illicit payments in buyer–supplier relations in China: analysing the experience of UK companies. J Bus Ethics 57(3):255–268

Osburg J (2018) Making business personal: corruption, anti-corruption, and elite networks in post-Mao China. Curr Anthropol 59(S18):S149–S159

Rawls J (1991) Justice as fairness: political not metaphysical. In: Equality and liberty: analyzing Rawls and Nozick. Palgrave Macmillan, London, pp. 145–173

Roohafza H, Ramezani M, Sadeghi M, Shahnam M, Zolfagari B, Sarafzadegan N (2011) Development and validation of the stressful life event questionnaire. Int J Public Health 56(4):441–448

Ruan J (2021) Motivations for ritual performance in bribery: ethnographic case studies of the use of guanxi to gain school places in China. Curr Sociol 69(1):41–58

Saraceno C (2016) Varieties of familialism: comparing four southern European and East Asian welfare regimes. J Eur Soc Policy 26(4):314–326

Scott JC (1985) Weapons of the weak: everyday forms of peasant resistance. Yale University Press, New Haven

Scott JC (1990) Domination and the arts of resistance: hidden transcripts. Yale University Press, New Haven

Sen A (2013) Rights and capabilities. In: Morality and objectivity (Routledge Revivals). Routledge, London, pp 130–148

Shen C, Williamson JB (2010) China’s new rural pension scheme: can it be improved? Int J Sociol Soc Policy 30(5/6):239–250

Smart A (2018) The unbearable discretion of street-level bureaucrats: corruption and collusion in Hong Kong. Curr Anthropol 59(S18):S37–S47

Smith ML (2010) Perceived corruption, distributive justice, and the legitimacy of the system of social stratification in the Czech Republic. Communist Post-Communist Stud 43(4):439–451

Sønderskov KM, Dinesen PT (2016) Trusting the state, trusting each other? The effect of institutional trust on social trust. Polit Behav 38(1):179–202

Titmuss R (2019) The gift relationship: from human blood to social policy. Policy Press Scholarship Online. https://doi.org/10.1332/policypress/9781447349570.001.0001

Watson A (2009) Social security for China’s migrant workers–providing for old age. J Curr Chin Aff 38(4):85–115

Williams F (2021) Social policy: a critical and intersectional analysis. John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken

Wu X (2019) Inequality and social stratification in postsocialist China. Annu Rev Sociol 45(1):363–382

Xu G, Dellaportas S (2021) Challenges to professional independence in a relational society: accountants in China. J Bus Ethics 168:415–429

Yi Q (2024) New urban women identity construction and rural patriarchy deconstruction: an ethnographic discourse analysis of duànqīn. Lang Discourse Soc 12(2):107–123

You JS (2012) Social trust: fairness matters more than homogeneity. Polit Psychol 33(5):701–721

Zhang L (2020) Anxious China: inner revolution and politics of psychotherapy. University of California Press, Oakland

Zhu X (2016) Dynamics of central–local relations in China’s social welfare system. J Chin Gov 1(2):251–268

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YZ independently implemented conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, data curation, writing-original draft preparation, writing-review and editing, and visualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study is based on publicly available anonymized data from the 2021 Chinese Social Survey (CSS), which was conducted and ethically approved by the Institute of Sociology at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS). The original data collection followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (1964) and its later amendments. As CSS does not publicly disclose an ethics approval reference number for the dataset, such a number is not available to secondary data users and is therefore not applicable. Because this study involved only the analysis of anonymized secondary data and did not include direct contact with human subjects, no additional ethics approval was required by the Research Ethics Committee of Chongqing University.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained by the CSS research team during the original data collection process in 2021. Participants were informed about the purpose of the research, assured of voluntary participation, and guaranteed confidentiality. As the present study uses anonymized secondary data only, no new consent procedures were required.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Y. The dual-track paradox in social welfare—a layered governance perspective. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1217 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05601-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05601-5