Abstract

Metalens is the next generation of optical metasurfaces for compact imaging, sensing, and display applications that allow the phase, polarization, frequency, amplitude, angular momentum, etc. of the incident light to be designed with high degrees of freedom to meet the application requirements, which has attracted broad interest in the field of planar optics. One significant challenge in implementing applications for metalens is the efficient fabrication of large-scale nanostructures with high resolution, robustness and uniform patterning. In this review, we first introduced the manufacturing techniques compatible with metasurfaces fabrication in detail, including masked lithography, maskless lithography, and additive manufacturing, discussed the limitations and provided some insights. Next, we introduced the applications of metalens from the perspective of non-imaging and imaging optics fields. Metalens can enhance the illumination effect, shape beams, and improve the energy conversion efficiency in non-imaging optics. In imaging optics, the role of metalens in replacing traditional optical components in lithography, astronomical observation, microscopic and endoscopic systems is demonstrated. Finally, the challenges that the metalens facing on the road to commercial application are discussed, and the field’s future development is prospected.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Traditional optical elements are based on the properties of light absorption, refraction and reflection, and use the accumulation of optical path in the medium to regulate the phase, amplitude and polarization of light, so the traditional optical elements are thick and heavy, and cannot adapt to the current development trend of optical components miniaturization. Therefore, the development of artificial micro/nano optical devices and materials has become the starting point for people to study light, and two major fields have been developed: metamaterials and metasurfaces.

In 1996, the Pendry team1 proposed periodic structures built of very thin metal wires, whose equivalent plasma frequency changes with the distance between metal wires and the radius of metal wires. Adjusting the equivalent plasma frequency to make it greater than the operating frequency can achieve a negative dielectric constant. Then, in 1999, the Pendry team2 proposed the split ring structure array built from nonmagnetic conducting sheets. It achieves equivalent negative permeability by changing the size parameters of its cell structure and spacing. Next, in 2000, the Smith team3 demonstrated a composite medium, the “left-handed” medium, based on split rings and wires in periodic array, which concurrently shows negative effective permeability and permittivity simultaneously in a frequency region at the microwave band. By artificially manipulating and designing materials’ optical and electromagnetic effects to guide light propagation, this idea has gradually become a reality with the development of advanced micro/nano processing techniques, and researchers began to study metamaterials4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15. Metamaterials have been widely studied in the microwave or terahertz band. However, in the optical wave band, the processing and preparation of metamaterials are complicated and high cost. Compared with metamaterials, planar artificial optical structures are relatively easy to fabricate and have lower loss in the process of interacting with light waves, so they have received extensive attention and research.

In 2011, the Capasso team16 proposed the generalized Snell’s Law, and demonstrated V-shaped antennas with diverse structural parameters to realize the regulation of the phase of linearly polarized light waves from 0 to 2π at subwavelength scale, successfully realizing the manipulation of the wavefront of transmitted light. The metasurfaces can effectively control the phase of the light wave at the subwavelength scale to control the wavefront of the light wave17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28. Subsequently, in 2012, the Capasso team29 proposed the 3D generalized Snell’s Law. In 2016, the Capasso team30 demonstrated the metalens with diffractive limit focusing and imaging with subwavelength resolution at visible wavelengths. In 2019, the Capasso team31 proposed the matrix Fourier optics for treating polarization in paraxial diffractive optics. Metalens provides a promising resolution for compact integrated optical systems, offering advantages such as reduced volume and weight, cost-effectiveness, and improved imaging capabilities. The manipulation of the structure’s shape, rotation direction, and height enables precise control over the polarization, phase, and amplitude of light. In the past decade, thanks to the advancement of micro/nano manufacturing techniques, the metalens has a high degree of design freedom, making it meet the requirements of various fields of application, including: augment reality or virtual reality32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39, holography40,41,42, microscopy and endoscopy43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54, spectroscopy55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63, wide field imaging64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80, projector81, optical logic gate82, polarizer83,84, etc.

In this paper, we reviewed fabrication, non-imaging and imaging applications of metalens, and discussed the challenges and prospects in the commercialization process. In the manufacturing section, the manufacturing methods for metalens with micro/nano-structures are summarized, including two main types of lithography methods: masked lithography (photolithography, nanoimprint lithography) and maskless lithography (electron beam lithography, focused ion beam, laser direct writing). In addition, additive manufacturing techniques (fused deposition modeling, stereo lithography apparatus, two-photon polymerization) offer a new approach to personalize metalens with irregular structures that cannot be obtained through conventional etching methods. The applicable scenarios, limitations, and prospective solutions for each technique are discussed. In the application section, metalenses have an extensive range of applications in the optical field and are highly innovative. In non-imaging optics, the non-imaging optical theory of metasurfaces has been initially established. However, the framework still needs to be further enriched by using geometric optics and wave optics. Metalens can shape and direct light beams, which is very suitable for laser systems and can enhance lighting efficiency or customize the lighting area in a personalized way. The light energy capture ability of metalens can enhance photodetectors’ efficiency and improve solar cells’ energy conversion efficiency. In imaging optics, metalens can be used in lithography to support micro/nano processing, assist astronomical observations, and improve imaging quality under microscopes and endoscopes. Two-photon polymerization lithography systems based on metalens can achieve commercial-grade precision. A single metalens without additional optical components can perform telescope functions. Microscopic or endoscopic systems based on metalens can further reduce their size and are particularly suitable for in vivo imaging systems. Finally, we discussed the environmental adaptability that is necessary for the development of metalenses from the laboratory to commercialization, the inverse design methods of metalens, evaluation methods of metalens, and some applications in emerging fields. Such as unmanned aerial vehicle platforms, perception and detection in autonomous driving, quantum optics, lightsails, etc. Further, the combination with artificial intelligence may be the future development trend. In conclusion, metalens possess high degrees of optical modulation freedom that traditional optical lenses cannot match, and they also have the characteristic of being compatible with semiconductor manufacturing, allowing for integration with existing optoelectronic device designs. Thus, metalenses will drive the development of the next generation of optics.

Metalens manufacturing technique

Masked lithography

Photolithography

Photolithography, being the most extensively employed micro-/nano-manufacturing technique to date, provides technical support for manufacturing micro- and nano-structures in various fields by transferring designed patterns to photosensitive materials. Although photolithography technique is limited by diffraction effects (Moore’s Law85), it can easily complete the manufacturing of subwavelength-scale metasurfaces, thanks to the high precision, high resolution, large-scale parallel processing capability, and high automation of lithography technique. By enhancing the parameters and methods employed in the lithography process, it is possible to enhance the accuracy and resolution of lithography to fulfill the precision demands of metasurfaces manufacturing. Its massively parallel processing capabilities and compatibility with manufacturing methods for complementary metal oxide semiconductor (CMOS) processes also provide additional possibilities for metasurfaces manufacturing.

The metasurfaces manufacturing route is consistent with the traditional processes of the mature integrated circuit industry, and with the help of algorithms, there is an opportunity to achieve centimeter-scale that is not possible with conventional designs. She et al.86 used a compaction algorithm to design a large-scale (2-cm-diameter) metalens. Figure 4a illustrates the fabrication process, which is a conventional and standard top-down etching-based approach. The subsequent references’ processes with similar etching-based methods are generally the same as this schematic representation, so they will not be presented redundantly. A 0.6-μm thick amorphous silicon (a-Si) layer is deposited on a 4 in. fused silica (SiO2) wafer substrate by the plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD) technique. Then, an adhesion promoter, the 1.1-μm-thick photoresist, and the 0.4-μm-thick photobleachable contrast enhancement material are spin-coated and baked successively. As shown in Fig. 2a, the photoresist is patterned using 5× reduction stepper lithography technique, throughputs of up to several hundred wafers per hour can be achieved. Then, the a-Si layer is etched using the inductively coupled plasma reactive ion etching (ICP RIE) technique to form nanostructures. Finally, the remaining photoresist is lifted-off. The final sample is shown in Fig. 1a. Furthermore, they indicated that metalens could be produced using chip manufacturing technique from approximately ten years ago, which revitalized the outdated equipment. Although the most advanced equipment still has advantages in some scenarios, it is not a necessary condition for achieving this goal. Then, Park et al.87 demonstrated an all-glass metalens of 1-cm-diameter and 0.1 numerical aperture (NA), operating at visible wavelengths. The fabrication process is as follows. A 100-nm-thick chrome (Cr) layer is deposited on a 100-mm-diameter SiO2 wafer substrate (as the hard mask). The photoresist is patterned using 4× reduction stepper lithography technique. Next, the Cr layer is etched using the ICP technique, and then the SiO2 layer is etched using the ICP technique to form nanostructures. Finally, the remaining Cr is lifted-off. The final sample is shown in Fig. 1b. As weight and drive distance increase, the force required for micro electro mechanical system (MEMS)-based centimeter-scale devices can become too great, and the required voltage can cause electrical breakdown, resulting in device failure. Colburn et al.88 took the Alvarez lens as inspiration and proposed a 1-cm-aperture, large area and focal length adjustable metalens system working in the near infrared (NIR) band by combining two independent metasurfaces. The fabrication process is as follows. A 2 μm thick silicon nitride (SiN) layer is deposited on a silicon (Si) wafer (100-mm-diameter) substrate by the PECVD technique. As shown in Fig. 2a, the photoresist is patterned using 5× reduction stepper lithography technique. A 150-nm-thick Al layer is evaporated (as the hard mask), and then the photoresist is lifted-off. The SiN layer is etched using the ICP technique to form nanostructures. Finally, the remaining Al is lifted-off. The final sample is shown in Fig. 1c. The visible metasurface needs to have sub-hundred-nanometers in size, which can be mass-produced using lithography technique.

a Photograph of the 4 fabricated 20-mm-diameter metalenses, measured by a ruler. SEM image shows the ring-arrangement a-Si nanopillars, scale bar: 2 μm. b Photograph of the 45 fabricated 10-mm-diameter metalenses on the 4 in. SiO2 wafer. c Photograph of the fully exposed and developed 100-mm-diameter wafer, showing the capability to make large area devices. d Photograph of the fabricated metasurfaces with the colored logo “IME”. e Photographs of the fabricated samples on the 12 in. glass wafer, and the central die, with a highlighted section indicating the metalens. f Photograph of the fabricated InP wafer containing 5000 metalenses. g Photograph of the entire fabricated 80-mm-diameter metalens on the 4 in. fused silica wafer, the border of the pattern stitching can be vaguely identified. h Photograph of the entire fabricated 50-mm-diameter metalens, measured by a caliper. Inset: the side view of metalens. i Photograph of the entire fabricated 100-mm-diameter metalens on the 6 in. fused silica wafer, compared with a table tennis racket. a Reprinted with permission from ref. 86. Copyright 2018 Optical Society of American. b Reprinted with permission from ref. 87. Copyright 2019 American Chemical Society. c Reprinted with permission from ref. 88. Copyright 2018 Optical Society of American. d Reprinted with permission from89. Copyright 2018 Optical Society of American. e Reprinted with permission from ref. 90. Copyright 2020 De Gruyter. f Reprinted with permission from ref. 91. Copyright 2024 Springer Nature. g Reprinted with permission from ref. 95. Copyright 2023 Optical Society of American. h Reprinted with permission from ref. 96. Copyright 2024 American Association for the Advancement of Science. i Reprinted with permission from ref. 97. Copyright 2024 American Chemical Society

a The large number of metalens’ patterns are obtained by conventional stepping method (the pattern is from single mask). b–d The large area metalens’ pattern is obtained by rotation-and-stitching method (the patterns are from serval masks). c The large area metalens’ pattern is obtained by step-and-stitching method (the patterns are from serval masks)

Hu et al.89 demonstrated a color display metasurfaces with critical dimension under 100 nm. The fabrication process is as follows. A 70-nm-thick SiN layer and 130-nm-thick a-Si layer are deposited successively on a 12 in. silicon wafer substrate by the PECVD technique. As shown in Fig. 2a, the photoresist is patterned using the ArF immersion lithography technique, and the a-Si layer is etched using the ICP technique to form nanostructures. Finally, the remaining photoresist is lifted-off. The reflectance spectra exhibit experimental observations of metasurfaces resonating at wavelengths of 675 nm, 570 nm, and 420 nm. This leads to the display of letters “I”, “M” and “E” in red, green, and blue colors respectively as depicted in Fig. 1d. The detection and handling of glass wafers pose challenges for lithography and etching tools compared to silicon wafers. Therefore, employing a layer transfer process can effectively address this concern. Then, Hu et al.90 demonstrated a 2-mm-diameter metalens working at 940 nm for fingerprint imaging. The fabrication process is as follows. A 1-μm-thick SiO2 layer and 600-nm-thick a-Si layer are deposited successively on a 12 in. Si wafer substrate by the PECVD technique. As shown in Fig. 2a, the photoresist is patterned using ArF immersion lithography technique, and the a-Si layer is etched using the ICP technique to form nanostructures. Next, a siloxane interlayer with a thickness of 60 μm is applied onto the patterned Si wafer, which is then bonded to a 12 in. glass wafer. Subsequently, the Si wafer is subjected to grinding and polishing on its reverse side to reduce the thickness of the wafer to approximately 20 μm. The remaining Si is etched by wet etching technique until etched to the SiO2 layer (as the stopping layer). The final sample is shown in Fig. 1e. Compared to SiO2, silicon nitride (Si3N4) exhibits a comparable transmission bandgap while exhibiting an elevated refractive index. Additionally, the compatibility of Si3N4 with indium phosphide (InP) foundry processes enables the potential advancement in downsizing optical devices through their integration with metalenses on InP platforms. De Vocht et al.91 developed a fabrication process for metalens that eliminates the need for metal hard masks. They demonstrated a broadband achromatic metalens with a reduction of chromatic aberration by 40%. The fabrication process is as follows. A 2-μm-thick SiO2 layer and a 750-nm-thick Si3N4 layer are deposited successively on the 3 in. InP wafer substrate. An anti-reflection coating (ARC) layer, a photoresist layer and an ARC layer are spin-coated and baked successively. As shown in Fig. 2a, the photoresist is patterned using the 4× reduction stepper lithography technique. The Si3N4 layer is etched using the ICP RIE technique to form nanostructures. Finally, the remaining photoresist and ARC are lifted off. The final sample is shown in Fig. 1f, which contains 5000 metalenses.

Metalenses that operate in the visible and NIR bands are mostly manufactured on SiO2 substrates. However, there is a notable absorption loss in the mid-infrared (MIR) observed in SiO2. Similarly, substrates like Si are susceptible to reflection losses. Therefore, an innovative manufacturing method is needed to manufacture metasurfaces that work in the MIR. Leitis et al.92 developed a method to overcome the challenge of manufacturing MIR metasurfaces due to the limited selection of materials with suitable optical properties. The proposed technology utilizes CMOS processes to fabricate metasurfaces on Si wafers, enabling the production of optically transparent aluminum oxide (Al2O3) membranes with DUV lithography. These nanoscale membranes, approximately 100-nm-thick, possess excellent transmission properties and an effective refractive index that closely approximates unity across a wide range of MIR wavelengths (from 2 to 20 μm). A single metalens on a sensor is difficult to achieve a large field of view (FOV), Hu et al.76 demonstrated a metalens array integrated with sensor for large FOV microscope. They fabricated the metalens array using one metalens mask through a standard Si nanofabrication process based on the 4× reduction stepper lithography technique. They proposed a mask compensation method, specific to the lithography machine used, by making a grating sample, comparing its feature size to the design value, and optimizing the mask design to compensate for the difference. This improves manufacturing quality and reduces the average size deviation (<30 nm) between designed and manufactured devices. In mask design, optical proximity correction93 can further improve accuracy. While dielectric metalens exhibit excellent transmission efficiency, the fabrication of flexible or multilayer devices poses significant challenges. Yang et al.94 proposed a multilayer metalens. They employ the technique of multilayer lithography to manufacture the metalens integrated with three metasurfaces, comprising three aluminum (Al) layers, each having a thickness of 200 nm, and interspersed by two polyimide (PI) layers with 50 μm in thickness. In addition, a 10-μm-thick top PI layer and a 10-μm-thick bottom PI layer are added as a protective layer. The final sample consists of four flexible PI layers and three Al layers. The metalens constructed on a metal-dielectric-metal sandwich architecture demonstrates a quadratic phase distribution.

It is challenging to manufacture large-scale metasurfaces with scanning-based lithography, but by combining multiple exposures with pattern stitching and rotation, it is possible to achieve this. Zhang et al.95 successfully designed a metalens telescope system based on an 80-mm-aperture metalens that exhibits exceptional efficiency for capturing celestial images. The metalens is fabricated by multiple-exposure processes with lithography, which involves the rotation-and-stitching of the pattern, as shown in Fig. 2b. The fabrication process is as follows. A 1-μm-thick a-Si layer is deposited on 4 in. fused silica wafer substrate. A 60-nm-thick ARC layer and 600-nm-thick photoresist layer are spin-coated and baked successively. Using 4 masks (each mask containing 4 patterns), a total of 16 patterns, the photoresist is patterned using the rotation-and-stitching method by the 4× reduction stepper lithography technique. After the ARC layer is removed using the oxygen plasma technique, the a-Si layer is etched using the ICP RIE technique to form nanostructures. Finally, the remaining photoresist and ARC are removed by the oxygen plasma technique. The final sample is shown in Fig. 1g, the border of the pattern stitching can be vaguely identified. The conventional MIR lenses have encountered various obstacles that hinder the extensive utilization of infrared thermography, such as limitations in aperture size, lens temperature, and the need for supplementary filtering. Hou et al.96 demonstrated a metalens-based thermographic camera using a metalens with a large 5-cm-aperture. They devised a method called “multi-reticle joint stepper lithography” to delineate the metalens pattern using nine masks. This concurrent stitching process is synchronized with the exposure of each mask, enabling simultaneous generation of multiple metalens patterns, as shown in Fig. 2c. The fabrication process is as follows. A photoresist is spin-coated and baked on a 6 in. Si wafer substrate. The photoresist is patterned by the stepper lithography technique. Nine different masks are employed to reveal nine distinct patterns. Simultaneously, the alignment marker ensures accurate positioning and connection of these patterns, creating four comprehensive metalens designs. The Si layer is etched by the ICP technique to form nanostructures. Finally, the remaining photoresist is lifted off. The final sample is shown in Fig. 1h, measured by a caliper. Park et al.97 demonstrated an all-glass metalens with a diameter of up to 100 mm for imaging the cosmos, composed of 18.7 billion nanostructures. The 100-mm-diameter area is divided into a grid comprising 25 square sections, arranged in a pattern of 5 × 5. By utilizing the rotational symmetry of the metalens, it can effectively represent these 25 sections using only seven distinct sections: one positioned at the center of the metalens and six others replicated at four different rotation angles. As a result, only seven photomasks are required for this purpose, as shown in Fig. 2d. The fabrication process is as follows. A 150-nm-thick Al layer is deposited on a 6 in. fused silica wafer substrate by the electron beam evaporation (EBE) technique. A 62-nm-thick ARC layer, a 600-nm-thick photoresist layer are spin-coated and baked successively. The photoresist is patterned by the 4× reduction stepper lithography technique to form the alignment marks. The underlying Al layer is exposed by employing the RIE technique to etch the ARC layer, followed by a wet-etch technique that removes approximately 120-nm-thick of the Al layer. This ensures compliance with the phase-contrast detection system requirements within the lithography system. The remaining photoresist and ARC are removed by the oxygen plasma technique. After the alignment marks are fabricated. A 62-nm-thick ARC layer and a 500-nm-photoresist layer is spin-coated on the wafer with alignment marks, and baked successively. Using the seven masks, the photoresist is patterned using the rotation-and-stitching method by the above lithography technique. The ARC layer is etched by the ICP RIE technique to expose the underlying Al layer. Then the Al layer is etched by the ICP RIE technique as the hard mask. The wafer is subjected to the plasma treatment downstream technique, which effectively removes any remaining photoresist and ARC, leaving behind only the patterned Al. Then, the SiO2 layer is etched by the ICP RIE technique to form 1.5-μm-tall nanostructures. The remaining Al is removed using the ICP RIE technique. The final sample is shown in Fig. 1i, compared with a table tennis racket.

Nanoimprint lithography

Currently, the development of lithography equipment has reached a bottleneck due to the diffraction limit of ultraviolet light wavelengths and the standing wave effect, which has limited the photolithography accuracy. Based on this, a new technique is proposed. The nanoimprint lithography (NIL) is proposed by Chou et al.98 in 1995, and since then, many scholars have conducted extensive research on the subject. In essence, it is the filling process of liquid polymers into template structure cavities and the demolding process of solidified polymers, so its resolution is only related to the template size and is not limited by the wavelength of light, the NA of the objective lens, the focusing system, etc. It has broken through the resolution limit of traditional optical exposure lithography processes. Additionally, NIL lithography technique has advantages such as high aspect ratio (AR), high efficiency, low cost, and high output.

At first, in the metasurface manufacturing process, nanoimprint technique was only used to pattern photoresist. In 2014, Yao et al.99 demonstrated a high-contrast grating (HCG). The fabrication process is as follows. To create a 2D hole-array Si master, they employ the interference lithography technique to produce a 1D periodic grating Si master. Subsequently, a flexible Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) mold is replicated from it. The photoresist on a Si substrate is imprinted twice in orthogonal directions using the PDMS mold. Follow by Cr deposited, photoresist lifted off, Si etched to form the 2D hole and Cr lifted-off. Then another 2D PDMS mold is duplicated from the 2D hole-array Si master. A titanium dioxide (TiO2) layer is deposited on a SiO2 substrate by the magnetron sputtering technique. The photoresist on the TiO2 layer is imprinted using the 2D PDMS mold. Follow by Cr deposited, photoresist lifted off, TiO2 layer and SiO2 layer etched to form the nanostructures and Cr lifted-off. The final sample is shown in Fig. 3h. Next, in 2016, Yao et al.84 presented a stacked metasurface design that exhibits high-contrast asymmetric transmittance in the visible-to-infrared wavelength range specifically for horizontally polarized light. The fabrication process is as follows. The 1D periodic grating Si master is fabricated by interference lithography technique, from which the mold is duplicated. A 190 nm high 1D Al grating is patterned on the SiO2 substrate, then a 355-nm-thick resist layer is spin-coated and cured as the buffer layer. A 510-nm-thick silicon nitride (SiNx) layer is deposited on the buffer layer by the PECVD technique. The photoresist on the SiNx layer is imprinted using a 1D hybrid grating mold. Follow by Cr deposited, photoresist lifted off, SiNx etched to form the nanostructures and Cr lifted-off. The final sample is shown in Fig. 3i. Then, nanoimprint molds are used to transfer the patterned nanostructures. In 2018, Lee et al.100 demonstrated a 20-mm-diameter transparent metalens with 0.61NA. The fabrication process is as follows. The Si master is fabricated by the electron beam lithography (EBL) technique, from which the polyurethane-acrylate (PUA) mold is duplicated. A 5-nm-thick gold (Au) layer, a 25-nm-thick Cr layer, and a 10-nm-thick SiO2 layer are deposited successively on the PUA mold by the EBE technique. A layer of polycrystalline silicon (p-Si) with a thickness of 100 nm is applied onto the quartz wafer substrate through the utilization of low-pressure chemical vapor deposition (LPCVD) technique. Subsequently, an adhesive layer with thickness of 10 nm is spin-coated onto the surface. The PUA mold with Au, Cr, and SiO2, is attached to the quartz substrate using adhesive in combination with p-Si. Following this step, pressure is applied to aid in transferring the deposited substances. The p-Si layer is etched to form the nanostructures (the transferred Cr patterns is used as the hard mask). Finally, the Cr is lifted off and the metalens is cleaned.

a Schematic of the fabrication process of facile nanocasFabrication methods and images of fabricated metalenses via the NIL technique.Fabrication methods and images of fabricated metalenses via the NIL techniqueFabrication methods and images of fabricated metalenses via the NIL techniqueting. b Schematic of the fabrication process based on nanocomposite material. c Schematic of the fabrication process with stamp fabrication (spin coating and thermal cure) and imprinting (spin coating, stamp placement, UV cure and stamp release) to produce tens of thousands of devices. d Schematic of the fabrication process based on the ALD technique. e Schematic of the fabrication process for twisted bilayer metadevice, the top layer is reversal nanoimprinted onto the bottom layer with a twist angle. f Schematic of the fabrication process based on wet etching technique. g Schematic of the fabrication process with tape-assisted, which enables duplication of residual layer-free meta-atoms. h SEM image shows the fabricated high-contrast grating with the TiO2-SiO2 bilayer nanopillars. i SEM image shows the fabricated meta-polarizer with SiNx metagrating, buffer layer, and Al metagrating. j SEM image shows the fabricated metalens with high AR TiO2 PER nanopillars with different sizes. k SEM image shows the cross-section of the fabricated bilayer metadevice with an intermediate layer. Photographs of replicated metasurfaces on various substrates: glass substrate (l), curved substrate (m), and flex substrate (n). Inset: the top view of metasurfaces. Photographs of replicated metalenses on various substrates: glass substrate (o), flex substrate (p), convex substrate (q), and concave substrate (r). a, l–n Reprinted with permission from ref. 101. Copyright 2019 American Chemical Society. b Reprinted with permission from ref. 103. Copyright 2021 American Chemical Society. c–j Reprinted with permission from ref. 104. Copyright 2021 American Chemical Society. d Reprinted with permission from ref. 105. Copyright 2023 Springer Nature. e–k Reprinted with permission from ref. 107. Copyright 2023 De Gruyter. f, o–r Reprinted with permission from ref. 108. Copyright 2023 Springer Nature. g Reprinted with permission from ref. 112. Copyright 2025 John Wiley and Sons. h Reprinted with permission from ref. 99. Copyright 2014 American Vacuum Society. i Reprinted with permission from ref. 84. Copyright 2016 Optical Society of America

Conventional NIL technique often necessitates additional processes like deposition and etching, leading to decreased productivity, limited substrate compatibility, and reduced price competitiveness. In 2019, Kim et al.101 introduced a cost-effective and efficient nanocasting method for producing dielectric metasurfaces, eliminating the need for additional processes. This basically laid the foundation for the current mainstream method of nanoimprint metasurfaces. Figure 3a shows the fabrication process. A hard-polydimethylsiloxane (h-PDMS) mold is replicated from the master, achieving sub 100 nm replication resolution. Then, a PDMS layer is coated on the h-PDMS layer as the buffer layer. A layer of particle-embedded resin (PER) is spin-coated onto the h-PDMS mold to form the nanostructures, the PER is a low-loss material, which consists of TiO2 nanoparticles (NPs) and the ultraviolet (UV) curable resin. Then the h-PDMS mold is placed PER-side down on the glass substrate. Pressure and UV exposure are applied to the transfer process. Finally, the h-PDMS mold is removed smoothly. The refractive index of the PER layer is sufficiently high, which makes it a suitable candidate for metasurface structuring without requiring etching or deposition procedures. Moreover, this method can be applied to various substrates such as glass substrate (Fig. 3l), curved substrate (Fig. 3m), and flex substrate(Fig. 3n). Then, Yoon et al.102 used a method similar to the above to fabricate a metalens. The difference is that the PER is dropped on the glass substrate instead of spin-costing on the mold.

In 2021, Yoon et al.103 demonstrated a novel demolding processes, that is, applying a self-assembled monolayer (SAM). Figure 3b shows the fabrication process. A liquid-phase SAM is coated on the master to facilitate smooth demolding processes. Next, a h-PDMS mold is produced by replicating the master, followed by applying a PDMS layer as a buffer on top of the h-PDMS layer. A layer of Si nanocomposite is spin-coated onto the h-PDMS mold to form the nanostructures. Then the h-PDMS mold is placed upside down on the glass substrate. Pressure and heat are applied to the transfer process. Finally, the h-PDMS mold is removed. The presence of TiO2 as a photooxidation catalyst can induce the yellowing of the carbon content within the polymeric matrix, resulting in enhanced absorption and reduced efficiency of the metalens. Einck et al.104 demonstrated a 0.2NA metalens. Figure 3c shows the fabrication process. The Si master is fabricated by the EBL technique, from which the h-PDMS mold is duplicated. A PDMS layer is coated on the h-PDMS layer as the stress dissipation layer. A layer of TiO2-based nanoparticle inks (The UV-assisted curing process of the NIL ink utilizes the photocatalytic properties of TiO2, leading to the formation of an inorganic substance) is spin-coated on a Si substrate. Then the h-PDMS mold is placed upside down on the glass substrate, and pressure and UV are applied to form the nanostructures. Finally, the h-PDMS mold is removed. The final sample is shown in Fig. 3j, indicated that a high AR up to 7.8 for the imprinted nanopillar.

In 2023, Kim et al.105 demonstrated the efficient mass manufacturing of 1-cm-aperture metalenses by using the immersion lithography technique to manufacture the master plate. Additionally, by depositing a thin metallic oxide film, such as TiO2, onto the surface of the resin nanostructures, the conversion efficiency can be enhanced. Figure 3d shows the fabrication process. The 12 in. Si master is fabricated by the ArF immersion lithography technique, which has 669 dies of a 1-cm-diameter metalens patterns, from which the h-PDMS mold is duplicated. A layer of resin is spin-coated on the h-PDMS mold to form the nanostructures, and then the h-PDMS mold is placed upside down on the glass substrate. Pressure and UV exposure are applied to the transfer process, and the h-PDMS mold is removed smoothly. Finally, a thin film of TiO2 is then coated onto the nanostructures by the atomic layer deposition (ALD) technique. Through the 12 in. mold imprinting, a high resolution enables a 75-nm-wide critical dimension and a 40-nm-gap critical dimension. The transfer yield of metalenses from a 4 in. wafer is high at 95%, but there is a reduction in yield as the size of the wafer increasing. To achieve a high AR structure with injection molding process can realize reproducible metalens with high throughput. Ishii et al.106 introduced an advanced method for replicating high AR nanostructures in metalenses. This process involved utilizing nickel (Ni) molds and injection molding to create multi-level nanopillars. The fabrication process is as follows. A mold is duplicated from the master, then a layer of hybrid polymer is spin-coated on the glass substrate, and then the mold placed on the glass substrate. Pressure and UV exposure are applied to form the nanostructures, and the mold is removed smoothly. A Ni layer is deposited on the nanostructured glass substrate by conformal deposition and electroplating technologies to form a Ni stamper. Subsequently, the prepared Ni stamper is removed from the glass substrate. They used an injection molding machine and Ni stamper to fabricate a metalens, thermoplastics (polycarbonate and Iupizeta) as the material. It is challenging to design a metasurface using low-refractive index materials, such as the commonly used transparent polymer material known as SU-8 photoresist. Chen et al.107 demonstrated a bilayer metadevice with relative twist angles. The fabrication process is shown in Fig. 3e. A 180-nm-thick SU-8 layer is coated and baked on a 0.5-mm-thick glass slide (as the adhesive layer). Then, a 350-nm-thick SU-8 layer is coated on the sample and baked, and it is imprinted with the silane-coated IPS mold under pressure and UV exposure. The IPS mold is demolded resulting in nanohole array with depth of 280 nm, the bottom layer is fabricated. Next, a 350-nm-thick SU-8 layer is coated on a silane-coated IPS mold. This SU-8 IPS mold is upside-down and placed on the bottom layer, with a rotation angle of 64.4°. The transfer process involves the application of pressure and exposure to UV, which effectively enhances the bonding between the top layer and the bottom layer, resulting in top layer with nanohole array (280-nm-depth). Finally, the IPS mold is removed. Figure 3k shows the cross-section of the fabricated bilayer metadevice with an intermediate layer. The conventional NIL technology employing the h-PDMS mold unavoidably induces shear stress on the nanostructures, leading to detrimental structural impairment. Choi et al.108 proposed a new wet etching NIL method without a demolding process. Figure 3f shows the fabrication process. The Si master is fabricated by the EBL technique, and then a liquid-phase SAM is coated on the master to facilitate smooth demolding processes. Then the water-soluble polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) mold is duplicated form the master. The TiO2 PER is spin-coated on the PVA mold, and then the mold placed upside on the pretreated substrate. Pressure and UV exposure are applied to the transfer process. Finally, the mold is removed by including deionized (DI) water wet etching technology, wet etching of the PVA mold does not apply any external pressure to the nanostructure. Furthermore, this method is compatible with various substrates, including glass substrate (Fig. 3o), and flex substrate (Fig. 3p), convex substrate (Fig. 3q), and concave substrate (Fig. 3r).

In 2024, Park et al.42 proposed a new fabrication method for fabricating metasurfaces using the stepper lithography and the NIL technique to overcome the high cost and mass production limitations of EBL technology. The fabrication process is as follows. The 8 in. Si master is fabricated by the ArF stepper lithography technique, containing 266 metasurfaces, from which the h-PDMS mold is duplicated. The TiO2 PER is spin-coated on the h-PDMS mold, and then the mold placed upside down on an 8 in. glass substrate. Pressure and heat are applied to the transfer process. Finally, the h-PDMS mold is removed from the glass substrate. The results demonstrate the production of practical metasurfaces using low-cost and high-throughput processes. Kim et al.109,110 used the above method to mass-produce highly efficient, 1-cm-diameter, UV metalenses with 0.2NA. The fabrication process is as follows. The 8 in. Si master is fabricated by the ArF stepper lithography technique, from which the h-PDMS mold is duplicated. A PDMS layer is coated on the h-PDMS layer as the buffer layer. The UV curable resin is spin-coated on the h-PDMS mold, and then the mold placed resin-side on the 8 in. SiO2 substrate. Pressure and UV exposure are applied to the transfer process, and then the h-PDMS mold is removed from the SiO2 substrate. Finally, A zirconium dioxide (ZrO2) thin film is deposited on the nanostructures using the plasma enhanced atomic layer deposition (PEALD) technique to improve conversion efficiencies significantly. TiO2 suffer from high absorption losses in the UV region, leading to significant optical losses, reducing the overall efficiency of the optical devices. Kang et al.111 proposed using ZrO2 PER instead of TiO2 PER. ZrO2 PER is transparent and exhibits a refractive index of approximately 1.8 at 320 nm, suitable for operating in the UV band.

Most studies on PER-NIL have primarily focused on investigating suitable materials to improve the efficiency of imprinted metasurfaces. However, the challenge of PER-NIL is the high-index residual layer that remains on the substrate, which introduces unwanted noise and restricts the efficiency and functionality of the imprinted samples. In 2025, Park et al.112 proposed a novel method named tape-assisted PER-NIL, achieving one-step removal of the residual layer using a tape. The ideal PER concentration and the tape suitable for the residual layer removal process are determined to establish a stable transfer scheme, that is, particle size of 30 nm TiO2 PER (weight ratios of 60%) and polyethylene tape. Figure 3g shows the fabrication process. The Si master is fabricated using the EBL technique. The soft mold (toluene-diluted PDMS) is duplicated from the master, then the TiO2 PER is coated on the soft mold. The tape is attached and detached from the PER-filled soft mold to remove the residual layer uniformly. This process is repeated until the soft mold appears clean. PER-filled soft mold is pressed onto the substrate the pretreated substrate. Pressure and UV exposure are applied to the transfer process. Finally, the soft mold is gently removed. Tape-assisted PER-NIL demonstrates promising applications in the manufacturing of dielectric structural color or hologram metasurfaces. The imprinted structural color metasurfaces feature a sharp single reflectance peak that cannot be achieved using conventional NIL. The imprinted hologram metasurfaces produce high-quality images over a wide wavelength range, outperforming traditional methods.

Two main techniques of masked lithography for fabricating metalenses or optical metasurfaces are reviewed. Without the need for mass production, using mature photolithography to manufacture research metalenses is relatively cost-effective, because the conventional lithography technique has semiconductor-level accuracy and the cost is lower than the price of the EBL technique. The further expansion of existing DUV lithography equipment to the broader research market will take some time to settle until most research teams can afford it. This will encourage more research to take full advantage of these devices. For the large-area metalens using multiple masks, higher precision mark alignment is also a research direction that needs to be overcome, as well as the coincidence and transition of pattern boundaries. For metalenses that need to be mass-produced, especially for future commercial applications on a large number of consumer-grade devices, the use of nanoimprint lithography is fairly cost-effective, because only using one master to imprint could obtain multiple metalenses in a short time. Further research is needed on the abrasion of nanostructures on the master plate and the removal of residual polymers after each imprint, and also on how to integrate with existing die stamping equipment for standardized production. In addition, metasurfaces can be manufactured by the self-assembly lithography technique113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120, the printed circuit technique121,122,123, the decal transfer technique124, the nano-skiving technique125,126, and the align-bond-peel technique127.

Maskless lithography

The precision of processing surface micro/nano-structures by the conventional photolithography technique mainly depends on the accuracy of the mask plate. Although the processing method of high-precision mask plates is relatively mature, the preparation of mask plates requires equipment such as mask graphic data processing systems, optical graphic generators, mask resist coaters, mask developers, and mask duplicators. The process is highly complex and costly. Maskless lithography techniques such as electron beam lithography, focused ion beam lithography, and laser direct writing are attracting increasing attention from researchers.

E-beam lithography

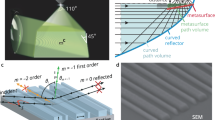

Electron-beam lithography (EBL) is a maskless lithography that uses very short-wavelength focused electrons to directly act on the surface of electron-sensitive photoresist to draw micro/nano-structures that match the design pattern. The electron beam lithography system has ultra-high resolution and flexible patterning advantages. Still, due to low exposure efficiency and complex control, the EBL technique is more commonly used in producing lithography masks, advanced principal prototypes and nanoscale scientific research and development. Manufacturing metasurfaces using the conventional top-down etching-based method generally uses the EBL technique to define the pattern, as shown in Fig. 4a. Deposition, etching, lift-off and other processes are required, which introduce manufacturing defects. Figure 4b,c shows a novel bottom-up deposition method for manufacturing metasurfaces, it will be explained in detail in the subsequent content.

a the conventional top-down etching-based method and (b) the novel bottom-up deposition method (nanostructures are defined using patterned EBR), no proportional relationship. c Fabrication process for freestanding bilayer metasurfaces. Reprinted with permission from ref. 140. Copyright 2025 Springer Nature

The EBL technique is based on scanning, which makes it possible to define a variety of complex patterns. Wang et al.128 proposed a design principle to achieve achromatic metasurfaces and presented a broadband achromatic metalens that operating in the NIR region. This metalens can concentrate light of various wavelengths at the same focal plane. The fabrication process is as follows. A 150-nm-thick Au layer and a 3-nm-thick Cr film are deposited successively on the Si substrate by the EBE technique, and then a 60-nm-thick SiO2 layer is deposited by the PECVD technique. A 100-nm-thick EBR layer is spin-coated and baked, and then the EBR is patterned using the EBL technique. A 3-nm-thick Cr film and a 30-nm-thick Au layer are deposited successively on the patterned substrate. Finally, the remaining EBR is lifted off. The final sample is shown in Fig. 5a. The EBL technique can also be used to fabricate metagrating structures arranged symmetrically at the center129. Yao et al.130 demonstrated a nonlocal metalens. The fabrication process is as follows. A 327-nm-thick a-Si layer and a 22-nm-thick Cr layer (as the hard mask) are deposited successively on the SiO2 substrate by the EBE technique. An 80-nm-thick PMMA layer is spin-coated and baked on the sample, and then the PMMA is patterned by the EBL technique. The Cr and a-Si layers are successively etched by the ICP technique to form the nanostructures. Finally, the remaining Cr is removed. The final sample is shown in Fig. 5b, which consists of crescent-moon-like nanostructures.

a SEM image of the metalens with different Au metaatoms. b SEM image of the fabricated metalens with crescent-moon-like nanostructures (integrated-resonant unit) with different sizes. c SEM image of the fabricated metalens with complementary GaN nanofins with different orientations, scale bar: 10 μm. d SEM image of the fabricated metalens with complementary GaN nanofins with different orientations. e SEM image of the fabricated metaform mirror with Ag nanostructures with different sizes. f Photograph of the fabricated 280-mm-diameter nanoimprint master on the 300-mm-diameter Si wafer, compared with a 1€ coin. g SEM image of the fabricated metahologram with high AR TiO2 nanofins with different orientations. h SEM image of the fabricated metalens with high AR TiO2 nanofins with different orientations. i SEM image of the fabricated metalens with high AR TiO2 nanopillars with different sizes, scale bar: 600 nm. j SEM image of the fabricated metalens with high AR TiO2 nano-fishnets with different sizes. k SEM image of the fabricated metasurfaces with bilayer high AR TiO2 nanofins with different orientations. l SEM image of the fabricated metalens with cavity bilayer Al nanorods with different orientations, scale bar: 300 nm. m SEM image of the fabricated metasurface with high AR resist nanofins. n SEM image of the fabricated metasurface with resist gratings. a Reprinted with permission from ref. 128. Copyright 2017 Springer Nature. b Reprinted with permission from ref. 130. Copyright 2024 Springer Nature. c Reprinted with permission from ref. 131. Copyright 2018 Springer Nature. d Reprinted with permission from ref. 132. Copyright 2019 Springer Nature. e Reprinted with permission from ref. 135. Copyright 2021 American Association for the Advancement of Science. f Reprinted with permission from ref. 136. Copyright 2023 Society of Photo-Optical Instrumentation Engineers. g Reprinted with permission from ref. 137. Copyright 2016 National Academy of Sciences. h Reprinted with permission from ref. 30. Copyright 2016 American Association for the Advancement of Science. i Reprinted with permission from ref. 138. Copyright 2016 American Chemical Society. j Reprinted with permission from ref. 139. Copyright 2020 Springer Nature. k Reprinted with permission from ref. 140. Copyright 2025 Springer Nature. l Reprinted with permission from ref. 141. Copyright 2020 Springer Nature. m Reprinted with permission from ref. 142. Copyright 2020 American Chemical Society. n Reprinted with permission from ref. 143. Copyright 2023 Chinese Laser Press

The hard mask layer not only acts as a medium for graphic transfer but also protects the underlying material. In the etching process, the underlying material may be physically or chemically damaged. These damages can be effectively reduced by adding one or more hard mask layers. Wang et al.131 demonstrated a broadband achromatic metalens operating in the visible region. The fabrication process is as follows. An 800-nm-thick undoped gallium nitride (GaN) layer is deposited on the sapphire substrate by the metal organic chemical vapor deposition (MOCVD) technique. Then, a 400-nm-thick SiO2 layer is deposited by the PECVD technique. A 100-nm-thick EBR layer is spin-coated and baked, and then the EBR is patterned using the EBL technique. Next, A 40-nm-thick Cr layer is deposited by the EBE technique (as the hard mask). Then, the remaining EBR is lifted off, and the SiO2 is etched by the RIE technique to transfer patterns (as the hard mask). The GaN layer is etched by the ICP RIE technique to form the nanostructures. Finally, the remaining SiO2 is removed. The final sample is shown in Fig. 5c, where well-defined nanofins and their inverse structures are obtained. Lin et al.132 demonstrated a full-color light-field achromatic camera based on a metalens array that can capture light-field information. The fabrication process is the same as that of131. The final sample is shown in Fig. 5d. Fan et al.133 demonstrated an algorithm-generated metalens for generating a side lobe suppressed, considerable depth of focus light sheet. The fabrication process is the same as the above fabrication process. Wang et al.134 developed a top-down etching-based method for the fabrication of TiO2 nanopillars, exhibiting unprecedented AR with pillar heights reaching 1.5 μm and vertical sidewalls at approximately 90°.

The EBL technique process on substrates with nonplanar surfaces poses significant difficulties due to the inherent constraint of electron beams’ limited depth of focus. Nikolov et al.135 successfully created the metaforms, which combine the advantages of freeform optics and metasurfaces into a unified optical element. The fabrication process is as follows. A 120-nm-thick silver (Ag) layer (as the ground layer) and a 75-nm-thick SiO2 layer are deposited successively on the toroid substrate by the EBE technique, the concave toroid area of the toroid substrate spanning a 6-mm-diameter circular aperture. A EBR bilayer containing the 60-nm-thick bottom layer (PMMA 495) and the 80-nm-thick top layer (PMMA 950) is spin-coated on the SiO2 layer. Adopting a focal zone splitting method, the EBR bilayer is patterned by the EBL technique. Next, an Ag layer is deposited on the sample by the EBE technique to form the nanostructures. Finally, the remaining PMMA is lifted off. The final sample is shown in Fig. 5e. The metagrating is constructed on a metal-dielectric-metal (Ag-SiO2-Ag) sandwich architecture, and covers the metaforms area of 2 × 1.5 mm.

The EBL technique may be able to manufacture large-scale metasurfaces. Zeitner et al.136 demonstrated the potential of utilizing the character projection (CP) EBL writing mode for efficient fabrication of optical nanostructures over large areas. This approach proves particularly advantageous when producing metasurfaces consisting of repetitive unit cells. A 280-mm-diameter nanoimprint master is fabricated on a 300-mm-diameter Si-wafer by the CP-based EBL technique. This master incorporates metagrating, consisting of densely packed arrays of dots with varying diameters and pitches. The final sample is shown in Fig. 5f. The minimum feature size is set at 100 nm, accompanied by a pitch of 200 nm. By employing the CP-based EBL technique, it becomes possible to significantly increase writing speed, surpassing previous methods by several orders of magnitude. Consequently, this CP-based EBL process emerges as the sole viable technology for efficiently realizing such large metasurfaces within an acceptable timeframe.

Achieving high AR nanostructures using conventional top-down dry etching method can pose challenges and potentially result in heightened roughness along the sidewalls. The Capasso team137 developed a novel method for fabricating metasurfaces with high AR based on the ALD technique. ALD is a process that naturally limits itself, ensuring the film thickness is controlled with precision and uniform coverage. Figure 4b shows the novel fabrication process. An adhesion promoter layer and 600-nm-thick EBR layer are spin-coated and baked on the fused silica substrate successively. A 10-nm-thick Cr film is coated on the sample by the EBE technique to mitigate charging effects that may occur during the writing process. The EBR is patterned using the EBL technique to determine the geometrical characteristics of the nanostructures. Next, a TiO2 film is coated on exposed surfaces until all features are entirely filled with TiO2 by the ALD technique. Notably, initial TiO2 deposition via the ALD technique conformally coats the sidewalls and top of the EBR and exposed substrate. The total TiO2 film thickness required is not less than half of the maximum width of all gaps. In practice, it is recommended that the TiO2 thickness be well beyond the minimum requirement to ensure that TiO2 entirely diffuses into all pores and there are no voids in the final nanostructure. Then the TiO2 layer is etched until the underlying EBR is exposed by the RIE technique. Finally, the remaining EBR is removed. The final sample is shown in Fig. 5g. Three metaholograms are designed to demonstrate the efficiency of the metasurfaces fabricated by this process. The metaholograms have efficiencies of 82%, 81%, and 78% at wavelengths of 480 nm, 532 nm, and 660 nm respectively. Then, the Capasso team30 demonstrated three high AR metalenses with 0.8NA at visible wavelengths. The fabrication process is the same as that of137, high AR nanostructures with near 90° vertical sidewalls are obtained rather than the top-down etching process. The final sample is shown in Fig. 5h. Experimental characterization demonstrates that the 3 metalenses, with same 240-mm-diameter and a 90 mm focal length, have focusing efficiencies of 86%, 73%, and 66% with corresponding wavelengths of 405 nm, 532 nm, and 660 nm. Next, the Capasso team138 demonstrated three metalenses with 0.6NA and another three metalenses with 0.85NA at visible wavelengths via the above fabrication process. The final sample is shown in Fig. 5i. Experimental characterization demonstrates that the three metalenses, with the same 0.6NA, have focusing efficiencies of 30%, 70%, and 90% with corresponding wavelengths of 405 nm, 532 nm, and 660 nm. The another three metalenses, with the same 0.85NA, have focusing efficiencies of 33%, 60%, and 60% with corresponding wavelengths of 405 nm, 532 nm, and 660 nm. These metalenses can concentrate incoming light into spots as tiny as ~0.64λ, achieving imaging with exceptional resolution. Ndao et al.139 demonstrated a fishnet achromatic metalens via the above fabrication process, as shown in Fig. 5j, and the unit-cell design of the metalens achieves multiple degrees of freedom thanks to the EBR, which determines the nanostructures’ shape. Recently, the Capasso team140 developed a novel method for fabricating bilayer metasurfaces with high AR. The metasurfaces are composed of free-standing TiO2 nanofins directly stacked on top of one another, operating in the visible band. Each nanofin enables independent 0–2π phase coverage at each layer using geometric phase. Figure 4c shows the novel fabrication process. The general process is consistent with their previous reports137. Moreover, it should be noted that when the e-beam process occurs on the top layer, the resist located on the bottom layer is also exposed to ballistic electrons. As a result, the exposed regions of both the top and bottom resists become soluble in a developer solution. Thus, selecting the resist material and the developer solution is crucial. Even though both resist layers are exposed simultaneously, if the chemicals in the exposed bottom layer resist are either insoluble or exhibit minimal solubility in the developer solution for the top layer resist, development will occur only in the top layer. Meanwhile, the bottom layer resist film will remain undisturbed. ZEP520A and o-Xylene are selected as the bottom resist layer and its developer, respectively. PMMA and MIBK/IPA 1:3 Positive Radiation Developer or H2O/IPA 1:3 solution are selected as the top resist layer and its developer, respectively. This set of resist and developer allows selective development of the top resist while minimizing the impact on the bottom resist. The final sample is shown in Fig. 5k, which consists of bilayer high AR TiO2 nanofins.

The EBL technique can also directly define the resist to form nanostructures without etching or lift-off processes, avoiding structural damage. Li et al.141 demonstrated a cavity-enhanced bilayer metalens with improved efficiency. The fabrication process is as follows. A 100-nm-thick polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) layer is spin-coated on the indium tin oxide (ITO) coated quartz substrate, and then the PMMA is patterned by the EBL technique. Finally, a 30-nm-thick Al layer is deposited on the patterned PMMA. The lift-off process is unnecessary, thereby preventing the structural fluctuations caused by it. The final sample is shown in Fig. 5l. Andrén et al.142 developed a method to construct metasurfaces directly from an exposed resist, eliminating the need for extra material deposition, lift-off or etching processes. The final sample is shown in Fig. 5m. Sin Tan et al.143 demonstrated the utilization of large-scale metasurfaces to create an economically viable manufacturing process for an all-dielectric multilevel security print aimed at anti-counterfeiting. This innovative approach relies on SU-8 gratings. The rapid achievement of a large area print (1 mm2) within a remarkably short duration (~11 min) is attributed to the exceptional sensitivity of the resist (~200 nm feature size). The fabrication process is as follows. An ~650-nm-thick SU-8 layer is spin-coated and baked on the Si substrate, and then the SU-8 is patterned using the EBL technique to form the nanostructures directly. Finally, the un-patterned SU-8 is removed. The final sample is shown in Fig. 5n. To minimize the occurrence of residual layers and prevent any crosslinking effects resulting from thermal exposure, it is advisable to avoid post-baking.

Focused ion beam

Focused ion beam (FIB) is an advanced nanomachine technique that uses high-energy ion beams to etch, deposit, and modify materials on a tiny scale as an atomic manipulation tool. During the etching process, most of the sputtering spilled particles are pumped away by the vacuum pump, but some will fall near the etched area, and this process becomes redeposition. Redeposition can fill adjacent structures, so when etching multiple adjacent structures, a parallel pattern is often used to minimize the impact of redeposition.

Principe et al.144 first demonstrated the metafibers, which integrate optical metasurfaces on the fiber tip, the meta-tips (MTs). The fabrication process is as follows. A 2-nm-thick Cr film (as the adhesion layer) and a 50-nm-thick Au layer are deposited successively on the facet of the fiber (single-mode fiber, SMF) by the EBE technique. Finally, the Au layer is etched by the FIB technique to form the nanostructures. The final sample (MT3) is shown in Fig. 6a, b. Five prototypes of MT are manufactured to serve as a proof-of-concept, encompassing beam steering and surface wave coupling, which aligns closely with the theoretical framework. Xomalis et al.145 demonstrated a metadevice for all-optical signal modulation based on coherent absorption. Figure 6c shows the functionality of the network, which is based on controlling light absorption with light on an ultrathin metamaterial absorber. The fabrication process is as follows. A 70-nm-thick Au layer is deposited on the facet of fiber (cleaved polarization-maintaining single-mode silica fiber) by the thermal evaporation technique. Next, the Au layer is etched by the FIB technique to form the nanostructures. The final sample is shown in Fig. 6c (inset). The fiber output is coupled to a second cleaved polarization-maintaining optical fiber using two micro-collimator lenses to realize an in-line fiber metadevice. Yang et al.146 demonstrated a metafibers for focusing light in the telecommunication regime. The fabrication process is as follows. A 40-nm-thick Au layer is deposited on the facet of large-mode-area photonic crystal fiber (PCF) by the magneton sputtering technique. Next, the Au layer is etched by the FIB technique to form the nanostructures. The final samples are shown in Fig. 6d (0.37NA) and Fig. 6e (0.23NA).

a SEM image of the fabricated metafiber, shows the entire fiber cross-section. b SEM image shows the entire metasurface with different sizes Au nanoholes (upper). SEM image shows two units (lower). c Light-light interaction on the metasurface exhibiting coherence. Inset: SEM image of the entire fabricated sample (right), black scale bar: 100 μm. Inset: SEM image shows the asymmetrical Au split ring apertures array (left), gray scale bar: 1 μm. SEM images of two fabricated PCF metalens with Au nanoholes with different orientations. NA of (d) and (e) is 0.37 and 0.23, respectively. f SEM image of the cross-section of the fabricated metafiber (left). SEM image shows the entire metasurface with Au nanoholes with different orientations. g SEM image of the cross-section of the fabricated metafiber. h SEM image shows the concentric ring Au nanogrooves (metagrating). SEM images show the fabricated single metalens (i) and the fabricated array of metalenses (j) is integrated with a μ-LED respectively, with different sizes GaN nanoholes. a, b Reprinted with permission from ref. 144. Copyright 2017 Springer Nature. c Reprinted with permission from ref. 145. Copyright 2018 Springer Nature. d, e Reprinted with permission from ref. 146. Copyright 2019 De Gruyter. f Reprinted with permission from ref. 147. Copyright 2023 De Gruyter. g, h Reprinted with permission from ref. 148. Copyright 2024 American Chemical Society. i, j Reprinted with permission from ref. 149. Copyright 2024 Elsevier

Hua et al.147 demonstrated the utilization of plasmonic metafibers in the development of cylindrical vector lasers with all-fiber Q-switching capabilities. The fabrication process is as follows. A 5-nm-thick Cr film and 50-nm-thick Au layer are successively deposited on the facet of fiber (two-mode fiber with a ceramic ferrule, TMF-CF) by the thermal evaporation technique. Next, the Au layer is etched by the FIB technique to form the nanostructures. The final sample is shown in Fig. 6f. Then, the TMF-CF with metasurfaces is packaged with a SMF-CF utilizing a ceramic casing. Liebtrau et al.148 investigated the coherent coupling between electrons and light in a circular metagrating positioned on the input surface of a multimode fiber. This interaction was achieved by utilizing the Smith-Purcell effect. The metagrating is composed of 237 concentric rings with an approximate radial spacing of 200 nm and a maximum diameter of 100 μm. The fabrication process is as follows. A 5-nm-thick Cr film and a 45-nm-thick Au layer are successively deposited on the facet of a multimode fiber. Next, the Au layer is etched by the FIB technique to form the nanostructures. The final sample is shown in Fig. 6g and h. Kim et al.149 demonstrated a micro-light-emitting diodes (μ-LED) with central emission wavelength of 390 nm, which integrated with metalens to improve extraction efficiency and directivity. The GaN surface of μ-LED (a 60-μm-diameter, hexagonally shaped) is etched by the FIB technique to form the nanoholes. A μ-LED integrated with a single metalens (60-μm-aperture) is fabricated, as shown in Fig. 6i. Moreover, a μ-LED integrated with an array of metalenses (each 10.9-μm-aperture) is fabricated, as shown Fig. 6j.

Direct laser writing

Direct laser writing (DLW) has been increasingly chosen as a micromachining route for efficient, economical, high-resolution material synthesis and conversion. It is one of the main techniques for making diffractive optical elements. It uses a laser beam with variable intensity to forms the required relief contour surface. When subjected to intense laser irradiation, the SiO2 substrate undergoes decomposition resulting in the formation of porous glass. The refractive index of this porous glass correlates directly with the intensity of the applied laser. More specifically, when employing a high-energy laser source, a plasma characterized by a significant concentration of free electrons is produced via a process known as multiphoton ionization. It is worth noting that these stripe-like nanostructures emerge due to interference occurring between this plasma and the incident light beam150. Femtosecond laser ablation has the characteristics of low damage threshold and small thermal diffusion zone, which can realize “non-thermal” micro-machining of materials, thus significantly reducing the negative impact of thermal effect in traditional long pulse laser processing.

Zhou et al.151 demonstrated a wideband photonic spin hall metalens (PSHM), which combining two types of geometric phase lenses into a single lens with dynamic phase integration. The glass substrate is etched by the femtosecond laser direct writing (FLDW) technique to form the spatially varying nanogrooves in the center of the substrate 4 mm×4 mm region. The final sample is shown in Fig. 7a. The results depicted in Fig. 7b offer supplementary proof that the laser therapy led to the creation of nanostructures aligned vertically, surpassing the wavelength limit at remarkably subwavelength scales. Then, Zhou et al.152 proposed a method for detecting edges across a wide range of frequencies using metasurfaces that utilize PB-phase. The glass substrate is etched inside by the FLDW technique (50 μm beneath the surface) to form the nanostripes in the center of the substrate 8 mm×8 mm region. The final sample is shown in Fig. 7c. Next, Zhou et al.153 demonstrated a phase imaging metadevice inspired by the eagle eye. The fabrication process is as follows. The fused silica plano-convex lens is etched inside by the FLDW technique (50 μm away from the flat surface) to form the nanostructures in the center of the substrate 6 mm diameter region. The final sample is shown in Fig. 7d and e. Wei et al.154 demonstrated a varifocal metalens. The fabrication process is as follows. The layer-by-layer method is employed to fabricate the graphene oxide (GO) layer, utilizing the self-assembly technique. The PDMS substrate is coated with alternating layers of poly dimethyl diallyl ammonium chloride (PDDA) and GO, where each bilayer of PDDA-GO has an approximate thickness of 4 nm. A total of 62 bilayers are utilized to construct the metalens. The PDDA-GO bilayers are etched by FLDW technology to form the concentric nanorings in the center of the substrate 150 μm diameter region. The final sample is shown in Fig. 7f. Hakamada et al.155 demonstrated a metalens operating at 0.8 THz with 2-cm-diameter of and a focal length of 30 mm. High-resistivity silicon substrate is etched by the FLDW technique to form 5,569 through-holes.

a Photograph of the fabricated metalens, scale bar: 4 mm. b SEM image indicates the microscopic laser-written spatially varying nanogrooves, scale bar: 300 nm. c Photograph of the fabricated metasurfaces (left), scale bar: 5 mm. Optical image of the metasurface created using a polariscope (right), scale bar: 25 μm. The orientation of structures in one period is represented by the red bars. Inset: the induced nanostructures are depicted in the SEM image, scale bar: 500 nm. d Dark-field image depicting the cross-sectional view of the fabricated metadevice, scale bar: 50 μm. Inset: photograph of the fabricated metadevice. e SEM image shows the arrangement of nanopores, with a magnify image reveals the detail. f SEM image of the entire fabricated metalens (left). SEM image shows the concentric graphene oxide nanogrooves (right). g Schematic of the light modulation process employed by PPLL, which generates patterned pulses with energy distribution characterized by gradient boundaries. The polarization direction is indicated by the arrows. h Schematic of fabrication of nanohole arrays with optimized non-diffracting laser lithography, scale bar: 500 nm. i Schematic of optimization in phase diagram by a reverse-axicon phase diagram. j SEM images of fabricated metalens consists of 3-mm-diameter nanoholes with different depths. a, b Reprinted with permission from ref. 151. Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society. c Reprinted with permission from ref. 152. Copyright 2019 National Academy of Sciences. d, e Reprinted with permission from ref. 153. Copyright 2024 John Wiley and Sons. f Reprinted with permission from ref. 154. Copyright 2021 American Chemical Society. g Reprinted with permission from ref. 156. Copyright 2022 Springer Nature. h–j Reprinted with permission from ref. 157. Copyright 2025 John Wiley and Sons

Modulated laser beams with one-step patterning capabilities have attracted the attention of researchers. Huang et al.156 developed a patterned pulse laser lithography (PPLL) for fabricating the large-are metasurfaces with sub-wavelength feature resolution nanostructures. Repetitive ablated or modified structures can be rapidly generated by high-speed scanning of ultrafast laser pulses separated using patterned wavefronts created by quasi-binary phase masks. The use of gradient intensity boundaries and circular polarization in the wavefront, which is capable of reducing diffraction and polarization-induced asymmetric effects as light propagates, thus maintaining a high degree of uniformity. As shown in Fig. 7g, the modulation of a linearly polarized femtosecond laser with a distribution of polarizations, followed by filtering to maintain homogeneous linear polarization. Subsequently, this polarization state can be transformed into circular polarization using a quarter-wave plate, ultimately achieving customized patterns with controlled light intensity. Experimental characterization demonstrates that the large-area metasurfaces (10 × 10 mm2) with 250,000 concentric rings can be fabricated in only 5 min. Conventional metalenses with nanopillars often encounter issues related to limited phase delay, which is attributed to the constrained AR and duty cycle of their unit cells. Xu et al.157 proposed a novel high-speed non-diffracting laser fabrication method for all-glass metalens with nanoholes, assisted with thermal and chemical after-treatment, as shown in Fig. 7h. The laser is modulated using a spatial light modulator that is programmed with a distinctive inverted-axicon phase pattern and subsequently focused through an objective lens. High-speed laser scanning along a predefined 3D trajectory is enabled by an xyz-motion stage, which leads to spatially isolated single-pulse ablation on a glass substrate for the efficient initial creation of hole arrays. Then, subsequent after-treatments involve high-temperature annealing (removing stress concentration) and hot alkaline etching (enlarging the hole diameter reaching the target scale with polished side wall). The non-diffracting Bessel beam is optimized using a reversed-axicon phase profile to ensure the consistency of the nanohole diameter throughout its depth, as shown in Fig. 7i. This method could fabricate metasurfaces with a period as small as 0.8 μm, notably, the depth can be precisely controlled to be over 10 μm. Then, they fabricated a 3-cm-diameter metalens with 10 mm focal length as shown in Fig. 7j, high-speed scanning causes a slight shift in the distribution of nanoholes due to the position accuracy of the motion stage and pulse triggering. Subsequently, a meta blazed grating, a meta axicon lens, and a vortex plate are fabricated to further verify the broad applicability of this method.

Three main techniques of maskless lithography for fabricating metalenses or optical metasurfaces are reviewed. EBL is particularly suitable for manufacturing metalenses with high resolution, high AR nanostructures, as the side-wall effect can be avoided by defining the pattern with the polymer, resulting in near-vertical nanostructures. However, the point-by-point exposure of the EBL increases the manufacturing time compared to the large-area pattern obtained by a single exposure of photolithography. The EBL still has the potential for large-area lithography, where the focused electron beam is projected onto the polymer through a mask with patterned holes, and the pattern of a period can be obtained through a single point exposure. FIB is suitable for manufacturing metalenses with nanohole structures because of its ability to perform precision engraving directly on the surface of the material. However, target atoms may be deposited on the sample surface, and ions may be injected into the sample, affecting the device performance, which requires a balanced consideration of the working parameters of the FIB. DLW is the alternative chosen solution for manufacturing large-area metalenses, with relatively low cost and high throughput characteristics, but it remains a challenge to engraving precise and uniform nanostructures.

Additive manufacturing

At present, manufacturing methods are mainly divided into subtractive manufacturing method, additive manufacturing method and partial methods combining the two. Additive manufacturing (AM) methods manufacture the target structure point by point or layer by layer on the basis of a file generated by computer aided design. In recent years, AM or so-called 3D printing technique has been developed, because 3D printing technique can easily and flexibly manufacture complex structures, processing based on additive manufacturing technique has been widely used, including artificial tissues and organs158, automobile industry159, aerospace industry160, architecture industry161, electronics industry162, food industry163, and fashion164 industry et al. Moreover, combining 3D printing with inverse-design could revolutionize metasurfaces design and manufacturing165,166,167, include improving the freedom of design, realizing complex shapes and structures, shortening the manufacturing cycle, and reducing costs.

Fused deposition modeling

The core idea of fused deposition modeling (FDM) is to melt one or more fibrous raw materials and deposit them on the substrate layer by layer. The advantage of this technique is that the principle is simple and the manufacturing cost is low. The quality requirements of precision optical components are often not met when using the FDM technique for direct processing. The components produced through FDM commonly exhibit drawbacks such as non-uniformity and subpar surface quality. These shortcomings often lead to significant light scattering effects that are not desired in optical applications.

Callewaert et al.168 demonstrated a series of non-resonant, broadband inverse-design metadevices at millimeter wave frequencies, including polarization splitters (Fig. 8a), meta-gratings (Fig. 8b), and metalenses, which are made of high impact polystyrene (HIPS) materials and fabricated by the FDM technique. HIPS is a rigid and impact-resistant plastic that is derived from the polymerization of styrene monomers. It also exhibits low dielectric loss with a measured tan δ < 0.003 in the frequency range of 26 ~ 38 GHz. The real part of the dielectric constant of HIPS ε’≈2.3. Ballew et al.169 demonstrated a series of inverse-design mechanically reconfigurable metadevices at millimeter wave frequencies that exhibit capabilities such as focusing (Fig. 8c), spectral demultiplexing (Fig. 8d), and polarization sorting (Fig. 8e), which are made of polylactide acid (PLA) materials and fabricated by the FDM technique (UltiMaker S3, UltiMaker). PLA is a bio-based, sustainable plastic. The assumed refractive index of PLA is 1.5 at working band, whereas the actual refractive index of PLA is approximately 1.65, due to the presence of an air gap resulting from incomplete filling of the device (causing a shift in the effective index of the waveguide mode towards a value between air and PLA). Then, Ballew et al.170 investigated the diffusion of wave dynamics in multilayer structures of rod layers at frequencies. This investigation utilized terahertz time-domain spectroscopy (THz-TDS). The rods layers are made of acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) materials and fabricated by the FDM technique (i3 Mega, Anycubic). The findings indicate that the optical and geometrical characteristics of the structures result in distinct spectral forbidden bands for the incident THz radiation. Melouki et al.171 demonstrated a conformal metalens with multiple beam-shaping functionalities at millimeter wave frequencies. The metalens is made of PLA materials and fabricated by the FDM technique. The final sample is shown in Fig. 8f. The relative dielectric constant of PLA εr = 2.72 with tan δ = 0.08 measured at 28 GHz.