Abstract

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) biosensoris a new type of high sensitivity, real-time, label-free detection technology, which plays an increasingly important role in the biomedicine field. Considering the urgent requirement of trace detection, especially for diagnosing early-stage diseases, the demand for high detection sensitivity of sensors is increasing. In recent years, various nanostructures have been proposed to design SPR biosensors. By constructing composite nanostructures, the detection sensitivity has been significantly enhanced, which has become a promising solution to expand the application of SPR biosensors. This review systematically summarized the basic principle, fabrication and illustrative application of SPR biosensors based on versatile nanostructures. Firstly, the mechanisms of various nanostructures to enhance the detection sensitivity of SPR biosensors were clarified. Then, the preparation strategies of various nanostructures were comprehensively illustrated. In addition, this review also summarized the latest applications of SPR biosensors with different structures. Finally, this review carefully highlighted the current challenges and possible development directions in future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

To date, SPR biosensor is a highly sensitive, real-time and label-free sensing technology based on the collective oscillation effect of free electrons on the surface of noble metals1,2,3,4. Free electrons on the surface of noble metals (such as gold and silver) oscillate collectively under the action of light field, forming propagating surface plasmon polaritons (PSPPs)5,6. Under a well-matched frequency, the incident photon drives coherent oscillations of surface electrons, the SPR effect is realized, and the resonance condition is extremely sensitive to the small change of the refractive index (RI) of the surrounding medium7,8,9. Therefore, the biosensor based on this principle can realize the real-time detection of nearby biological molecules10,11,12,13. With the advantages, SPR biosensor technology has rapidly become a core tool in the fields of life science, medical diagnosis and environmental monitoring14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22. The key performance index of SPR biosensor - detection sensitivity (usually measured by the resonant wavelength or angular shift caused by the change of RI unit)—directly determines its practical application value in the detection of trace biomarkers23,24,25.

Notation | GST | Ge2Sb2Te5 | |

|---|---|---|---|

0D | Zero-dimensional | LECT2 | Leukocyte chemokine-2 |

1D | One-dimensional | LSPR | Local surface plasmon resonance |

2D | Two-dimensional | LSP | Local surface plasmon |

AA | Ascorbic acid | LOD | Limit of detection |

AuNPs | Gold nanoparticles | MTAP | MXene TA Au PEG |

AuNPs@Mem | Membranes functionalized AuNPs | MOF | Metal-organic frameworks |

BIC | Bound States in the Continuum | NIL | Nanoimprint lithography |

BP | Black phosphorus | PDA | Polydopamine |

CCD | Charge coupled device | PD-L1+ | Programmed cell death ligand-1 positive |

CD-AuNPs | Cyclodextrin-functionalized AuNPs | PSM | Plasmon scattering microscope |

CEA | Carcinoembryonic antigen | PM | Plasmon metasurface |

CFP-10 | 10 kDa culture filtrate protein | PVD | Physical vapor deposition |

CNTs | Carbon nanotubes | PVP | Polyvinyl pyrrolidone |

CQ | Chloroquine phosphate | PVT | Physical vapor transport |

CTAB | Hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide | Quasi-BIC | Quasi Bound States in the Continuum |

CVD | Chemical vapor deposition | RF | Radio frequency |

CTCs | Circulating tumor cells | RI | Refractive index |

DDA | Discrete dipole approximation | RIU | Refractive index unit |

DLW | Direct laser writing | SEM | Scanning electron microscope |

EBL | Electron beam lithography | SNR | Signal-to-noise ratio |

FDTD | Finite-difference time-domain | SPR | Surface plasmon resonance |

FEM | Finite element method | SPRM | Surface plasmon microscopes |

FOM | Figure of Merit | SWCNTs | Single-walled carbon nanotubes |

FIB | Focused ion beam | TB | Tuberculosis |

FWHM | Full width at half maximum | TBG | Twisted bilayer graphene |

GHS | Goos-Hänchen shift | TDN | Triple DNA nanoswitch |

TMDs | Transition metal dichalcogenides | ||

GHP | Grotthuss-Hankins-Prigogine | UV | Ultraviolet |

GNR | Gold nanorods | VCDG | Vertically coupled double-layer gratings |

GO | Graphene oxide | vdWhs | Van der Waals heterostructures |

Traditional SPR biosensors mainly rely on uniform noble metal films as the sensing interface26. Its sensitivity is limited by the lack of electromagnetic field attenuation length (approximately 200 nm) and local field enhancement ability, which has gradually been difficult to meet the demand27,28,29. In recent years, through cross fusion of nanophotonics and materials science, SPR technology has experienced a paradigm shift from “thin film sensing” to “precise control of nanostructures”30,31,32. Through the customized design of nanostructures, enhancing local electromagnetic fields, expanding sensing areas and increasing bio-molecular binding sites have become the key directions to break through the bottleneck of existing technologies33,34,35,36.

The first is the composite structure of metal nanoparticles and metal films, which can improve the detection sensitivity through the coupling effect of SPR and local surface plasmon resonance (LSPR)37,38,39. For example, Chen et al. designed a MoSe2/ZnO composite sensing film plasmonic sensor for non-enzymatic glucose detection40, which obtained a 72.17 nm(mg/mL) detect sensitivity, and the detection limit is 4.16 μg/mL. Wulandari et al. introduced the SPR chip modified with MoS2-MoO3 nanoflowers prepared by hydrothermal method to detect the tuberculosis (TB) marker of 10 kDa culture filtrate protein (CFP-10)41, and obtained a response ten times higher than that of single plasmonic gold film. Liu et al. proposed a SPR strategy for functionalizing gold nanoparticles using red blood cell membranes and Circulating tumor cells (CTCs) membranes (AuNPs@Mem)42. It is used for high sensitivity detection of CTCs. AuNP in AuNPs@Mem as a signal amplification molecule, obtained a detection interval from 5 × 103 to 1 × 106 particles/mL, and the measurement limit was 868.11 particles/mL.

Secondly, two-dimensional (2D) materials (such as graphene and transition metal sulfide) can enhance SPR response through interface charge transfer and exciton-plasmon coupling due to their atomic thickness, high carrier mobility and tunable band gap characteristics, which has gradually attracted wide attention43,44,45. Phan et al. designed a SPR biosensor combined with 2D antimonene and applied it to the detection of microRNA46. The detection resolution of miR-21-5p and miR-125-5p is 21.29 fM and 27.65 fM, respectively. Banerjee et al. designed a SPR biosensor based on gold film and 2D materials gallium nitride (GaN) to detect four kinds of bacteria in drinking water47. The highest sensitivity of Escherichia coli is approximately 2.13 × 104 nm/RIU (refractive index unit, RIU). Kumar et al. designed a SPR biosensor combined with 2D graphene oxide (GO) for real-time and label-free detection of chloroquine phosphate (CQ) in water48. The limit of detection values of CQ in the final detected water and real samples (serum) were 0.21 μM and 0.34 μM, respectively.

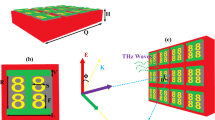

In addition, metasurface can precisely control the wavefront, phase and polarization of light through a sub-wavelength structure array49,50, providing a multi-dimensional signal enhancement mechanism for SPR sensors51,52,53. In recent years, metasurface has been gradually used in the design of SPR biosensors. Hu et al. developed a SPR sensor54 of selectively adjusting the resonance mode, which can either enhance the sensitivity to a theoretical maximum of approximately ~105 nm/RIU. The sensor achieved an detection limit for 27.5 fM for the detection of d-biotin molecule (MW = 244 Dalton). Another work by Shokova et al. investigate the sensing performance of gold silicon dioxide-gold optical cavity with nanopore array in the dielectric layer and top metal layer used finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) method55. By adjusting the size of the resonator and the spacing between the holes, the quality factor can reach the order of 5–7.

In this review, the methods for improving the sensitivity of SPR biosensors, which are based on diverse nanostructures, have been summarized, focusing on the theoretical explanations of different nanostructures to enhance the detection sensitivity and the recent progress, as shown in Fig. 1. The Review is divided into four parts: the first part describes the basic mechanism of SPR biosensors based on nanostructures; The second part summarizes the preparation methods of various nanostructures; The third part discusses the design of various nanostructured SPR biosensors and their applications in ultra-high sensitivity detection; The fourth part summarizes the current situation of this research field and prospects the future development trend.

Modulation methods of SPR biosensing technology

The SPR effect of metallic materials is closely related to the RI of the medium on the metal surface. When there is a slight change in the RI of the metal surface, the position of the SPR resonance peak will also change. If the cause of this change is a variation in the amount of biological analytes near the metal material surface, the concentration level of the biological analyte can be determined based on the change of the SPR resonance56. Therefore, the plasmonic biosensing detection technology developed based on this principle.

Based on different test parameters, SPR biosensing technology primarily employs four modulation methods: angle modulation57,58,59, wavelength modulation60,61, phase modulation29,62, and spatial displacement modulation63. The first two methods are the most widely used, and most commercial SPR detection instruments employ these two modulation methods due to their advantages of mature technology and stable and reliable results. However, angle modulation and wavelength modulation are gradually unable to meet the increasing sensitivity requirements. The third method, with high sensitivity, is currently in the stage of gradually maturing technology. Its disadvantage is that the experimental equipment is complex and relies on the quality of the optical path, which is not conducive to application promotion. The fourth method, which adopts a different measurement strategy from the above, avoids the instability caused by light intensity distribution by accurately measuring the Goos-Hänchen shift (GHS) caused by changes in RI. Therefore, it has higher accuracy and detection sensitivity, and has gradually gained attention and developed rapidly in recent years.

First, angle modulation is employed, which utilizes the light with a fixed frequency. By altering the incident angle, the intensity of the reflected light is detected as it varies with the incident angle, revealing the incident angle corresponding to the minimum reflected light intensity, namely the SPR resonance angle. Changes in the RI or concentration on the surface of plasmonic metallic thin film can be monitored through variations in the SPR angle. SPR sensors developed according to the principle of resonance angle changes are one of the earliest research directions in SPR detection, with detection sensitivity defined as the angle-dependent rate of change in RI (dθ/dRIU). There are primarily two methods for angle modulation. Firstly, the incident angle is altered through a mechanical rotating device, and SPR reflection spectra at various angles are obtained64, subsequently determining the SPR resonance angle, then the RI change of the target analyte can be determined. The second method involves directly incidenting the light at a certain range of incident angles, with the intensity of reflected photons being detected by a charge coupled device (CCD) to reveal the reflection spectrum65, determining the SPR angle and further obtaining the RI change of the target analyte.

Angle modulation has developed into a highly mature technology, characterized by high stability and reliable results. In situations where detection sensitivity is not particularly high or the reaction process is relatively slow, angle modulation remains a good choice. However, for the first method, it has stable performance, is constrained by the long time required for the mechanical rotation device to change the incident angle, making it disadvantageous in fast-response detection. The second method can quickly obtain reflection spectra at different angles, offering excellent real-time performance. But because the limit of the angle range or response interval of CCD, this method has a narrow detection range and is not suitable for situations where the RI of the target analyte changes significantly. Additionally, an improved intensity modulation method based on angle modulation is also a widely used modulation type. This method tracks the change in reflected light intensity at a fixed incident angle66, with detection sensitivity defined as the rate of change in reflected light intensity to RI change (dp/dRIU). Overall, the development of angle modulation has been relatively slow. With the rapid development of wavelength modulation and phase modulation methods, the disadvantages of angle modulation in terms of detection sensitivity are continuously magnified, gradually failing to meet the needs for detection sensitivity.

The second modulation method is wavelength modulation. In this method, a broad-spectrum light source, typically white light, is used as the probe light. With a fixed incident angle, the spectrum of the reflected light is detected and analyzed to obtain the reflectance curve as a function of wavelength. The resonant wavelength is recorded, and changes in the RI of the medium are detected through changes in the resonant wavelength. This, in turn, reveals the reaction progress of the target reactant. The detection sensitivity is defined as the rate of change of wavelength to RI (dλ/dRIU). The detection device employs a spectrometer. The advantage of a wavelength-modulated SPR biosensor is that it does not require a mechanical rotating device, offers good real-time performance, and has a wide spectral detection range. However, this method has a high dependence on the performance of the light source. The linewidth and intensity of ordinary light sources sometimes fail to meet detection requirements, and white light lasers are expensive, making them unsuitable for widespread use.

The third method is phase modulation. When light is incident on a metal surface at an angle greater than the critical angle for total reflection, in addition to significant changes in light intensity before and after reflection, the phase of p-wave (TM wave) also undergoes a drastic change, while the phase change of s-wave (TE wave) is much smaller. Therefore, s-wave can be used as a reference light, and the change in RI or concentration can be analyzed by measuring the phase difference between p-wave and s-wave in the reflected light. The detection sensitivity is defined as the angle-to-RI change rate (dΔφ/dRIU)62. The biggest characteristic of phase modulation is that its sensitivity is significantly improved compared to angle modulation and wavelength modulation, which has high application value in the field of micro-detection. Phase detection technology is also very suitable for real-time detection. Compared to the previous two modulation methods, phase detection technology requires more complex optical design and higher operational precision.

The final method is spatial displacement modulation. Its core idea is not to measure traditional changes in reflected light intensity, but to precisely measure the GHS caused by changes in RI and amplified by the SPR effect. SPR itself has already converted small changes in RI into shifts in resonance angle. Near the SPR point, the rate of change of GHS with respect to angle (dGHS/dθ) is much larger than the response change of reflectivity with regarding to angle (dR/dθ)63. This means that the same change in RI causes a much larger change in GHS than in reflected light intensity. Therefore, by measuring displacement rather than light intensity, theoretically, higher detection sensitivity can be achieved compared to traditional intensity methods. Additionally, traditional SPR sensors measure the absolute value of light intensity. As a result, they are very sensitive to noise caused by fluctuations in light source intensity, drift in detector sensitivity, and contamination on the surface of optical components. These factors directly lead to measurement errors. GHS, on the other hand, measures the movement of the light spot position, which is a relative value. As long as the spatial mode of light source is stable, the measurement of its central position is insensitive to absolute fluctuations in light intensity. This greatly reduces the system’s requirements for light source stability and electronic device noise, improving the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and long-term measurement stability.

Sensitivity enhancement mechanisms of SPR biosensors using plasmonic nanostructures

The versatile nanostructures can improve the performance of SPR biosensors, and it has different theoretical mechanisms respective. In this section, we will discuss the theoretical description of several structures such as metal nanoparticles, 2D materials and metasurface structure for the sensitivity enhancement of SPR biosensors.

Mechanism of metal nanoparticles-based enhancement in detection sensitivity

It is widely recognized that metal nanoparticles are capable of sustaining local surface plasmon (LSP) modes, which correspond to the plasmonic oscillations of free electrons within the particles67,68. Owing to the radiative nature of LSP modes, they can be directly excited by incident light69. Therefore, in a system composed of metal nanoparticles near the metal film surface, the electromagnetic interaction between LSP and SPP modes can be realized as long as the SPP mode excitation is controlled. The direct result of this interaction is the enhanced local electric field distribution in the gap region, which is applied to improve the detection sensitivity of SPR sensor37.

In order to describe the optical properties of SPR when metal nanoparticles interact with metal films, there is a special type of electromagnetic normal mode, the so-called “gap mode”, which exhibits strong spatial localization in the interstitial region between the particle and the substrate surface70. Gap mode is considered to be the source of local electric field enhancement.

In fact, the simplified electromagnetic theory can explain this phenomenon qualitatively. If the radius R of the ball is very small than the wavelength of the incident light, the delay effect of the electromagnetic field can ignore, and with dielectric function ε1(ω), which is located in the medium with dielectric constant \({{\rm{\varepsilon }}}_{m}\). Then the resonant frequency corresponding to LSP excitation can be given by ε1(ω)=− \({{\rm{\varepsilon }}}_{m}\) (l + 1)/l, where l is an integer (l = 1,2,…)70. The amplitude attenuation of the electric field outside the ball is r− (l+2), where r is the distance from the center of the ball71. The dipole mode with l = 1 is mainly excited. Then the metal ball is close to the metal surface ε2(ω), in this case, dipole-dipole interaction is used. This problem can be viewed qualitatively and the LSP mode is changed. However, a comprehensive treatment of this issue ought to incorporate all multipoles of the sphere, and the detailed theoretical analysis will not be reiterated herein71.

Indeed, various numerical analysis methods based on classical electromagnetism are used for the theoretical analysis of this system. Discrete dipole approximation (DDA)72, finite element method(FEM)28 and FDTD methods73 can be used to calculate the plasmonic properties of more complex nanoparticles and nanostructures. These calculation methods produce optical response of arbitrary nanoparticle geometry, it can achieve high accuracy (depending on grid density, time step, etc.) within the classical framework. It is the main tool to deal with complex practical problems at present74,75,76.

Recently, the plasmon hybridization theory provides a clear, convenient and simple method for calculating the SPR of composite nanostructures37,77. Plasmon hybridization theory decomposes nanoparticles or composite structures into simpler fundamental geometries, and subsequently computes the interaction or hybridization behavior of SPR in composite particles.

Due to the different SPR modes of the nanoparticles near the surface of the metal film, the SPR-LSPR energy coupling effect will occur, resulting in a very strong electric field distribution in the middle region, which is called the plasmon hybridization mechanism. The intensity of energy coupling is relying on the distance of two surfaces, and when these nanoparticles approach the metal surface, the plasmonic energy of the nanoparticles will show a strong shift. These offsets include not only the contribution of similar images generated by the interaction between nanoparticle plasmons and their images in metals, but also the hybrid offsets generated by the dynamic interaction between plasmonic modes. While the interaction consistently induces a red shift in plasmons and a decrease in nanoparticle spacing, the hybridization effect may result in either a red shift or a blue shift, depending on the relative energy levels of the plasmons associated with the nanoparticles and the surface. The electromagnetic enhancement is caused by the surface charge associated with the plasmonic oscillation and occurs at a frequency close to the plasmon energy of the film.

In the plasmon hybridization method, when the noble metal nanoparticles and noble metal nanofilms meet the spectral matching and the spacing is small enough (nanoscale), the plasmon mode between them will be strongly coupled, resulting in a new hybrid mode, which is anti-cross in spectrum78. The core advantage of strong coupling lies in the generation of super strong local electromagnetic “hot spots” in the gap between particles and films, and the hybrid modes that are has an extremely sensitive to the surrounding environment changes79. As a result, the response of the system to the change of external RI is much larger than that of a single structure, which improves the detection sensitivity of SPR sensor. It is one of the important strategies to realize ultra-high sensitivity optical sensor at present. In addition, when the strong coupling effect is applied to the SPR biosensor system, it can not only significantly improve the detection sensitivity, but also produce two coherent SPR vibration peaks due to the SPP mode splitting, so the proportional biosensor can be constructed to further improve the detection accuracy.

Mechanism of 2D materials-enhanced SPR detection sensitivity

In recent years, research on metal-2D material composite structure SPR sensors has become the hottest research direction in this field80,81,82. Some works have shown that by integrating 2D materials on the surface of metal thin films and constructing SPR sensing layers63,83,84, significant improvements in detection performance have been achieved, especially in the research direction of biosensors, which has gradually become the mainstream choice85,86. For sensors with 2D material/metal composite structure, it is generally believed that the electronic property of 2D materials, that is, the Fermi energy level (work function) of 2D materials is the key to enhance the sensitivity of SPR biosensors27,28. When the layered 2D material contacts with the noble metal film, the continuity of Fermi level causes the generation of charge transfer87,88. It is found that the charge transfer mechanism between noble metal surface and graphene can obtain a large amount of excitation energy, and the direction of charge transfer will be from graphene to Au film27. In addition, the 2D material can also increase the surface area volume ratio and optimize the distribution of surface active sites, which enhances the specific adsorption of the sensor to biological analytes, and will further improve the detection sensitivity, providing a new path for the development of biological detection devices with high integration and high response performance89,90.

Because this composite structure involves microscopic phenomena such as charge transfer, so the interaction between 2D materials and a series of metal surfaces can well explain by using the first principles. Taking graphene as an example43,91, it was found that the adsorption of graphene on Al, Cu, Ag, Au and Pt (111) surfaces resulted in physical adsorption, which retained the typical electronic structure of graphene, including cone point. In the case of physical adsorption, there are short-range graphene metal interactions. These results in the shift of the Fermi level of graphene relative to the conical point, and the work function of the grapheme-metal system changes significantly compared with the metal surface.

To characterize the physical adsorption and charge transfer mechanism between graphene layers and plasmonic metal, the DFT approach is employed. This model then takes only the work functions of isolated graphene and metal as input parameters, and predicts the work function shift of the metal–graphene system.

The work function W of grapheme-metal system is given by the Fermi energy level (W=− EF)91. For physically adsorbed graphene with very weak interaction so that its electronic structure remains unchanged, W should be related to Fermi level shift:

Where WG is the work function of freestanding graphene. We can see that although expression has a large separation between graphene sheet and metal surface for d = 5.0 Å, there is a small deviation ∼ 0.08 eV when the equilibrium separation d ≈ 3.3 Å, which can be traced back to the disturbance of physical adsorption of graphene, which cannot be described as a rigid offset and it can ignore this small disturbance.

Because WG and WM are different, if two systems communicate, electrons will transfer to balance the Fermi level. The charge transfer between metal and graphene leads to the formation of interface dipole layer and the related potential step. Once ΔEF is determined, it can be used to obtain the work function W.

This model describes the interaction of graphene and metal and the work function shift in grapheme-metal system.

In addition to the charge transfer mechanism, the exciton-plasmon energy coupling is also considered an effective approach to enhance the detection sensitivity of SPR sensors in 2D materials-metal system78,92,93. The strong coupling between excitons and plasmons in 2D materials resulting in exciton-plasmon hybridization, thereby improving the detection sensitivity of SPR sensors.

Firstly, electromagnetic enhancement occurs when the exciton resonance energy of a 2D material matches the SPR energy, leading to a strong coupling effect. This is manifested as the appearance of two new, separated peaks (i.e., Rabi splitting) in the spectrum, representing new quasiparticles-plasmon polaritons (plexcitons). This hybrid state more strongly confines electromagnetic energy to the 2D material layer and its surface region. The plasmon of the noble metal film provides significant field enhancement, while the exciton further “focuses” the energy within the atomically thin 2D material plane. This means that the electromagnetic field intensity in the sensitive area of the sensor is greatly amplified. In this case, when the analyte (such as a biomolecule) is adsorbed onto the surface of the 2D material, the local RI change it induces occurs in such a strong electromagnetic field environment94. Therefore, the enhanced electromagnetic field “amplifies” the small RI change into a large, easily detectable spectral signal shift.

Secondly, the interface interaction is enhanced. Few-layer 2D materials possess extremely high specific surface area, abundant dangling bonds, and active surface chemical properties, making them easy to functionalize and efficiently capture target molecules. They are inherently excellent “molecular capture layers”. The characteristics of excitons in 2D materials (energy, intensity, lifetime) are extremely sensitive to their surrounding dielectric environment (i.e., whether there is molecular adsorption)95. Even the adsorption of a single molecule can perturb the excitonic state. Additionally, in composite structures, the adsorption of molecules first directly modulates the excitons themselves (for example, leading to excitonic resonance red shift or quenching). Subsequently, this modulated excitonic state efficiently modulates the plasmonic resonance state through coupling. This is equivalent to adding a “signal amplifier”: molecular adsorption to excitonic change (via coupling) to significant plasmonic change. Traditional SPR is a one-step process of “molecular adsorption to plasmonic change”, whereas here it is a two-step process, with the second step playing an amplifying role.

It is particularly noteworthy that, beyond its direct impact on detection sensitivity, the coupling effect can narrow the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the resonance peak in certain coupling modes. A sharper resonance peak implies that the shift in peak position (dip) is more easily and precisely identifiable and measurable when displacement occurs, significantly enhancing the SNR and detection accuracy (Figure of Merit, FOM) of the sensor. This makes it possible to detect extremely weak signals.

Both theoretical and experimental evidence have confirmed that 2D materials and van der Waals heterostructures (vdWhs) can significantly enhance the detection sensitivity of SPR sensors27,96. This is primarily due to the mechanisms of charge transfer and exciton-plasmon coupling. It is important to note that vdWhs also exhibit excitonic characteristics that differ from those of 2D materials97,98. Moreover, the material properties of arbitrary material stacking can produce customized excitonic characteristics, making them one of the key research directions in the field of SPR sensors. In addition to altering materials to construct customized excitonic schemes, the lattice mismatch and Moiré superlattice generated in twisted bilayer structures (homojunctions or heterojunctions, such as twisted bilayer grapheme (TBG) or MoS2/WS2) can produce field amplification hotspots through unique mechanisms, further enhancing the performance of SPR sensors99. Firstly, the Moiré periodic potential field leads to uneven charge distribution, forming regions of extremely strong local electric fields. For example, the atomic-scale local strain present in TBG can alter the density of electronic states, further enhancing the local field. This restricts the extremely high field to a very small volume near the sensing region, making it sensitive to small amounts of analytes. By changing the twist angle, twisted bilayer structures precisely control the Moiré fringe periodicity, local strain field, and hotspot distribution. Thus, external electric fields or strain can further regulate electronic behavior, optimizing the sensor’s operating point and sensitivity. Additionally, twisted bilayer structures exhibit synergistic effects with plasmonic nanostructures, achieving plasmon-exciton coupling and significantly amplifying the signal. It is considered promising to achieve extremely high field enhancement and localization, potentially detecting binding events of individual biomolecules. Simultaneously, it can detect changes in RI and molecular conformation. By regulating the twist angle through an electric field, a laminated device dynamically adjusts the sensor’s sensitivity and operating range.

However, this also faces some challenges. Firstly, precise control of the twist angle, large-scale preparation of high-quality and uniform twisted bilayer structures, and their integration with SPR sensing structures still pose technical difficulties. Secondly, ensuring the long-term stability and signal reproducibility of complex heterostructures in the sensing environment is crucial. Lastly, the preparation and device processing costs of such advanced materials are high, and there is still a long way to go before they can be standardized and commercialized.

Mechanism of metasurface-based enhancement in detection sensitivity

The metasurface structure can significantly improve the detection sensitivity of SPR sensor after integrating with noble metal films100. The enhancement mechanism mainly has three factors. The first is SPR-LSPR synergy: noble metal nanoparticles support LSPR, while continuous metal films support propagating SPR. When the distance between the two is less than 10 nm, the electromagnetic field is strongly coupled to form a hybrid mode (upper branch/lower branch mode), and a “hot spot” is generated at the nano-gap, which increases the electric field intensity by several orders of magnitude. This mechanism has been introduced when the isolated metal nanoparticles are near the metal thin film discussed above77,101,102,103,104. The hybrid mode after coupling has both the large detection depth of SPR and the strong localization of LSPR, which significantly expands the electromagnetic energy density of the sensing region. Secondly, the metasurface structure (such as defective silver nanoribbons and stacked nanorings) can excite Fano resonance81,105,106,107,108, and its asymmetric line shape is due to the interference of bright mode (radiation mode) and dark mode (nonradiation mode)109. This kind of resonance has sharp spectral lines (FWHM) and is very sensitive to small changes in RI. High Q value directly improves the resolution of the sensor.

In metasurface structures, the phenomenon of bound states in the continuum (BIC) is also a concept that cannot be ignored. Although the research on SPR biosensing technology based on this principle is still in its initial stage, its strong vitality in the detection field has attracted widespread attention. Therefore, we believe it is necessary to discuss the positive role of this principle in the development of SPR biosensing technology. BIC is a theoretically existing special physical state that exists in the continuum but is not coupled with radiation channels110,111. It can be regarded as a resonance with zero leakage and zero linewidth, possessing an infinitely large quality factor Q. Obviously, perfect BIC is difficult to apply directly in reality. However, by intentionally introducing some perturbations (such as breaking structural symmetry), BIC can be transformed into quasi bound states in the continuum (Quasi-BIC)112. Although Quasi-BIC loses a little bit of energy, it still maintains a very high Q factor (far exceeding traditional SPR modes), and becomes observable and excitable. Therefore, it is actually Quasi-BIC that is considered to have broad prospects in the field of sensitive detection.

Firstly, it is important to note that Quasi-BIC exhibits Fano line-shaped spectra, leading to the misconception that any system exhibiting Fano line shapes necessarily satisfies Quasi-BIC. In fact, Quasi-BIC is one of the mechanisms that give rise to extremely high-Q Fano resonances. However, Fano resonances are not necessarily Quasi-BIC. For instance, a common micro-ring resonator, Fabry-Perot cavity, or Mie resonant particle can exhibit Fano line shapes as long as its resonant mode is coupled with the background channel. In such cases, the quasi-bound state behind the Fano resonance cannot be referred to as a Quasi-BIC.

Therefore, we can refer to the promotion effect of Fano resonance on SPR biosensing technology to analyze the improvement of Quasi-BIC on the sensitivity of traditional SPR sensors. Quasi-BIC brings about a qualitative leap in the following aspects: Firstly, the Quasi-BIC mode can achieve an extremely high Q factor, which is very important because this is precisely why we discuss Quasi-BIC separately. Although other Fano resonances can also achieve high Q values, they are still far less than those produced by Quasi-BIC. In theory, a perfect BIC has an infinitely large Q value, which means that its resonance peak is extremely sharp and narrow. When there is a slight change in the RI of the sensor surface, such a sharp resonance peak, even if it produces an extremely small shift, is more easily and precisely measurable, significantly improving the detection accuracy FOM and SNR. Secondly, quasi-BIC can greatly localize light energy within a very small area on the sensor surface, generating strong electromagnetic field enhancement. When the analyte (such as a biomolecule) enters this enhanced region, the interaction between the two is amplified, thereby amplifying the sensing signal. Finally, BIC and Quasi-BIC can be implemented through various platforms, including all-dielectric metasurfaces, metal-dielectric hybrid structures, etc. This provides the possibility for customized sensor design according to different sensing requirements (such as avoiding metal absorption loss and pursuing ultimate sensitivity).

Finally, the metasurface can dynamically adjust the reflection phase through geometric parameters (such as the period of the nanocup and the orientation of the nanorods)113, so as to adjust the resonant wavelength of the Tamm plasmon without changing the thickness of the dielectric layer60. At the same time, the metasurface localizes the light field at the subwavelength scale (breaking the diffraction limit), reducing the mode volume. For example, the volume of Tamm plasmon microcavity based on metasurface is smaller than that of traditional structure mode, which enhances the strong coupling between light and exciton (such as WS2), and the Rabi splitting increases.

Preparation strategies of various nanoparticles

Nanostructures have been gradually applied to the design and application of SPR biosensors in recent years, thanks to the rapid development of nano-preparation technology114,115,116,117. The precise synthesis technology of metal nanostructures became the driving force to promote the breakthrough development of SPR biosensors118,119,120,121. By adjusting the morphology and size (such as the preparation of gold nanorods (GNR) by seed growth method, the synthesis of silver nano-triangles by photochemical reduction, etc.)59,61,122,123, high-density electromagnetic “hot spots” can be constructed at the sensing interface to excite the ultra-strong local field enhancement effect (up to 104-106 times)124,125.

The dimensionality of nanomaterials is defined based on the number of external dimensions at the nanoscale (typically referring to at least one dimension ranging from 1 to 100 nanometers). This classification criterion focuses on the number of directions in which electrons are restricted in their movement through space, thereby determining their unique physical and chemical properties126.

-

1.

Zero-dimensional nanomaterials (0D)

All 3D (length, width, height) are in the nanoscale (<100 nm). The movement of electrons in all three spatial directions is restricted, which is known as “quantum dots”127. Their characteristic is that due to the confinement of electrons in all directions, a strong quantum confinement effect occurs, and their optical and electronic properties (such as emission color, bandgap) are strongly dependent on their size, rather than their chemical composition. For example, quantum dots of different sizes can emit light of different colors after being excited. Such as quantum dots (such as CdSe, PbS quantum dots), metal nanoparticles (such as gold nanospheres, silver nanocubes), etc.

-

2.

One-dimensional nanomaterials (1D)

Definition: Materials with 2D on the nanoscale, while the 3D is much larger than the nanoscale (micrometer or even millimeter scale)128. Electrons can move freely in one direction. They exhibit excellent electron or charge transport capabilities in 1D direction, while possessing a high specific surface area. Their mechanical properties are usually excellent. Examples include nanowires and nanorods (such as silicon nanowires, GNR), nanotubes (such as carbon nanotubes (CNTs)), nanoribbons, etc

-

3.

Two-dimensional nanomaterials (2D)

Only 1D (thickness) is at the nanoscale, while the dimensions of the other 2D are macroscopic129. Electrons can move freely within the 2D plane. They possess a large specific surface area and extremely high in-plane carrier mobility. Many 2D materials exhibit unique electronic and optical properties that differ from their bulk counterparts (such as the Dirac cone in graphene and the direct bandgap in molybdenum disulfide). Common examples include graphene (a single layer of carbon atoms), transition metal chalcogenides (such as molybdenum disulfide MoS₂ and tungsten disulfide WS₂), MXenes and black phosphorus (BP).

Production of 0D nanostructures

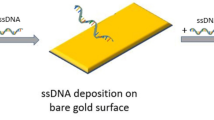

0D nanostructures (such as gold, silver nanospheres, etc.), due to its inherent LSPR effect, it is widely used in fields such as environmental detection, biochemical analysis, nanomedicine, etc130,131,132,133, and are synthesized in a many ways134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141. The commonly used principle is to reduce the metal precursor to nanoscale particles by chemical or physical means, and control its morphology, size and dispersion142,143,144,145,146. The main synthesis methods are as follows:

-

1.

Chemical reduction method (liquid phase method)

The liquid phase method is one of the most commonly used chemical synthesis strategies for preparing gold and silver nanoparticles (spheres). Its principle involves forming atomic nuclei by reducing metal ions in a solution, followed by controlling the growth and stabilization of the nuclei to ultimately obtain metal particles at the nanoscale.

-

a.

Sodium citrate reduction method (turkevich method, preparation of spherical gold nanoparticles147):

The sodium citrate reduction method is one of the most classic liquid-phase chemical reduction methods for preparing gold and silver nanoparticles. Sodium citrate serves as both a reducing agent and a stabilizer, enabling controlled reduction of metal ions and regulation of nanoparticle size/morphology. Its reduction mechanism relies on the reducibility of carboxyl groups, while its stabilization mechanism relies on electrostatic repulsion. This method can obtain about 10 ~ 100 nm gold nanospheres and 10 ~ 80 nm silver nanospheres. In addition, this method is often used as a precursor step of seed growth method to obtain nanoparticles “seeds”. The specific steps of this method, first, the aqueous solution of HAuCl4 (or AgNO3) with a certain concentration kept boiling, and a certain amount of trisodium citrate was added. After stirring and cooled to room temperature, the unreacted citric acid ions were removed by centrifugal cleaning to obtain gold/silver nanoparticles for use. By adjusting the concentration of sodium citrate, the size of nanoparticles can be controlled148,149.

-

b.

Sodium borohydride reduction method (preparation of small silver nanoparticles): Unlike sodium citrate, sodium borohydride is a strong reducing agent that can quickly reduce metal ions, but it has poor stability and requires balancing violent reactions with particle control. Therefore, when preparing silver nanoparticles using the sodium borohydride reduction method, it is necessary to control the reaction temperature and add suitable stabilizers such as sodium citrate or polyvinyl pyrrolidone (PVP) to inhibit particle agglomeration through steric hindrance and electrostatic repulsion. The specific steps of this method, firstly, rapid mixing of AgNO3 with an equimolar volume of chilled reductant solution (NaBH4 and trisodium citrate in deionized water) at 0°C. The excess reductant were removed by centrifugal cleaning to obtain small silver nanoparticles150,151. After washing with ethanol, it is dispersed in water or ethanol.

-

2.

Photochemical method (UV reduction)

Photochemical methods primarily utilize light energy to excite reducing agents or metal ions themselves, achieving controlled reduction through photogenerated radicals or electron transfer152,153,154,155. Common reducing agents include sodium citrate, triethanolamine, and ascorbic acid. The steps for preparing gold nanoparticles using photochemical method are as follows: first utilized an ethanolic mixture of HAuCl4 and PVP contained within a cuvette. Then, a continuous wave ultraviolet (UV) source (Generally, the wavelength is in the ultraviolet range) provided illumination at selected powers. After being exposed to light for a certain period of time, gold nanoparticles are formed. Finally, the unreacted PVP were removed by centrifugal cleaning to obtain gold nanoparticles for use156.

-

3.

Biosynthesis (green synthesis)

Green synthesis primarily refers to the method of using natural plant extracts or biomass resources as reducing agents and protective agents, replacing toxic and harmful chemical reagents in traditional chemical synthesis to prepare gold and silver nanoparticles157,158. The polyphenols, flavonoids, terpenoids in plant extracts, as well as aldehyde and carbonyl groups in biomass, all possess a certain degree of reducibility, capable of reducing metal ions to metal atoms. Simultaneously, macromolecules such as cellulose and hemicellulose in these natural products can provide steric hindrance effects, preventing nanoparticles from aggregating. Taking the synthesis of gold and silver nanoparticles using green tea extracts as a case in point, firstly, green tea aqueous extract was prepared by refrigerating leaves in deionized water. Extract was collected via filtration. The residual tea material was repeatedly extracted under identical conditions. Black tea aqueous extract followed analogous preparation. Ethanolic extracts utilized ethanol instead of water.

For AuNPs synthesis, mix HAuCl4 and tea extract in water and adjust pH employed NaHCO3 addition at ambient temperature, AuNPs were prepared. AgNPs were similarly prepared using AgNO3 instead of HAuCl4. Purified nanoparticles (20-50 nm) were stored in light-protected amber vials post-centrifugation159.

In conclusion, the chemical reaction synthesis method can synthesize nanoparticles with highly uniform size and regular morphology by precisely controlling reaction parameters (temperature, pH, reducing agent/stabilizer concentration, feed ratio, etc.)138. High monodispersity is crucial for SPR sensors because it can generate sharp and consistent LSPR absorption peaks, improve the energy coupling efficiency between nanoparticles and precious metal thin films LSPR-SPR, and improve the SNR and reproducibility of detection signals on the basis of increasing detection sensitivity. Liquid phase chemistry is easy to produce on a large scale, with relatively low costs, and can meet the high demand for materials in the commercialization of SPR sensors. During or after the synthesis process, various stabilizers or functional molecules can be conveniently introduced. This provides great convenience for the fixation of biological probes and is the basis for improving sensor selectivity. After decades of development, its synthesis mechanism has been thoroughly studied, the experimental plan is mature and reliable, and the repeatability is strong. However, the reducing agents, stabilizers, or other ions introduced in this method during the reaction may adsorb onto the surface of the nanoparticles, making it difficult to completely remove them. These residues can occupy the binding sites of biomolecules, non-specific adsorption of interfering molecules, or cause inactivation of biological probes, thereby reducing the selectivity and sensitivity of the sensor. Some nanoparticles prepared by chemical methods may aggregate in complex physiological environments or long-term storage, leading to SPR peak shift and broadening, which affects the stability and service life of the sensor.

For 0D nanoparticles, although the size can be well controlled, synthesizing unconventional and anisotropic 0D structures often requires more complex formulations and more stringent conditions, challenging their monodispersity. The entire process of photothermal synthesis is usually carried out in ultrapure water or organic solvents, without the need to add any chemical reducing agents or stabilizers. Therefore, the surface of the prepared nanoparticles is very “clean”, avoiding all the problems caused by chemical residues, which greatly helps to reduce non-specific adsorption and improve the selectivity and sensitivity of the sensor. The surface of laser prepared nanoparticles spontaneously forms a solvation layer (such as an OH⁻ layer in water), which enables them to maintain long-term colloidal stability without additional stabilizers, improving the reliability of the sensor. Multiple metal nanoparticles can be synthesized by simply changing the target material147. For SPR sensing, gold, silver, copper, and their alloy nanoparticles can be conveniently prepared to optimize the SPR response window and intensity. The laser ablation process can be synchronized with surface modification, and by selecting different liquid environments, nanoparticles with specific functional groups on the surface can be directly synthesized. Laser ablation is an instantaneous high-energy process that is difficult to finely control nucleation and growth at a “slow” pace like chemical methods. Therefore, the size distribution of the prepared nanoparticles is usually wide (with high polydispersity), which can lead to broadening of the SPR absorption peak, which is not conducive to obtaining high sensitivity and reproducibility signals. Compared to chemical methods, laser ablation requires larger equipment investment (high-energy lasers), has relatively lower synthesis efficiency, is difficult to produce on a large scale, and has higher costs. Although size can be controlled to some extent by adjusting laser parameters (energy, pulse width, wavelength) and solvent, its controllability and predictability are not as good as chemical methods, making it difficult to achieve on-demand synthesis of specific sizes.

The biosynthetic method (green synthesis method) uses biomass resources, with mild reaction conditions (constant temperature aqueous phase)160, no need for toxic chemicals, in line with the principles of green chemistry, extremely low cost, and sustainability. Biological templates (such as proteins and peptides) will directly coat the surface of nanoparticles while reducing metal ions. These biomolecules can naturally serve as recognition elements and can be directly used for detection, simplifying the sensor construction steps. Due to the use of biomolecules as coating layers, synthesized nanoparticles typically exhibit excellent biocompatibility and have great potential for in vivo biosensing applications. The biological molecule coating layer can provide good steric hindrance or electrostatic stability for nanoparticles. Poor monodispersity and controllability: This is the biggest weakness of green synthesis methods. The composition of biological extracts is extremely complex, and the differences in each batch lead to unpredictable reduction and stabilization abilities. Therefore, the size and morphology of synthesized nanoparticles vary greatly, and the reproducibility is extremely poor. This is a fatal disadvantage for SPR sensors that require uniform and stable signals. The surface of the particles is coated with a complex mixture of biomolecules, which may be arranged in a random manner. This not only makes it difficult to precisely control the fixed orientation and density of probe molecules, but it may also generate strong non-specific adsorption, seriously interfering with the specific recognition of target substances and significantly reducing the selectivity and sensitivity of the sensor. The reaction mechanism involves the synergistic effects of multiple biomolecules, which have not been fully elucidated to date. This makes it difficult to standardize and precisely regulate the process, resulting in a high dependence on the source and batch of biological raw materials. Overall, if pursuing high-performance and high reliability SPR sensors, chemical synthesis method is still the most practical choice after optimization. Photothermal synthesis, as a “pure” preparation method, is a strategic direction for solving specific adsorption problems in the future, but it needs to be combined with subsequent separation and purification technologies (such as centrifugation and filtration) to improve monodispersity. The concept of biosynthetic methods is attractive, but unless breakthroughs are made in mechanism research and process control (such as using genetically engineered bacteria to produce a single reducing protein), their applications will mainly be limited to fields that do not require high signal consistency.

Production of 1D nanostructures

1D nanostructures mainly refer to nanoscale structures such as nanowires and nanorods. 1D noble metal nanostructures have received widespread attention due to their flexible and adjustable LSPR resonance frequency161,162. This characteristic has been widely applied in various fields, especially in biological detecting and biomedical research163. The preparation of 1D gold and silver nanorods/wires primarily employs the seed growth method164, utilizing hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) as a template. By regulating the growth of gold and silver nanoparticles (with growth proceeding on a seed-based foundation), the aspect ratio of the nanorods can be modulated, thereby tuning their plasmonic resonance properties. The CTAB concentration is a crucial determining factor. Reducing agents commonly used include ascorbic acid (AA) and sodium borohydride. The preparation of gold/silver nanorods via the seed growth method: Firstly, preparation of seed solution: Add HAuCl4•3H2O aqueous solution to CTAB solution in a test tube (glass or plastic). The solution is gently mixed by reversing and the color is bright brown yellow. Then, immediately add cold NaBH4 aqueous solution, and then quickly reverse the mixing. It should be noted that the escaping gas is allowed to escape during the mixing process. The tubes were then stored in a water bath for future use. The seed solution can be used for more than 1 week.

Secondly, preparation of GNR: Take an appropriate amount of CTAB solution, water, HAuCl4, AgNO3, L-ascorbic acid and seed solution, remove them one by one in the test tube according to the given order, invert and gently mix. For example, CTAB, HAuCl4•3H2O and AgNO3 solution were added to the test tube in sequence, and then gently mixed by inversion. The solution at this stage exhibits a bright brownish-yellow color. Upon subsequent addition of L-ascorbic acid, the solution turns colorless after thorough mixing. Finally, add seed solution, gently mix the reaction mixture and let it stand for at least 3 h165,166,167.

Production of 2D materials

2D materials are synthesized through diverse methodologies, encompassing mechanical exfoliation, physical vapor deposition/transport (PVD/PVT), chemical vapor deposition (CVD), and solution-phase techniques96,168.

-

1.

Physical mechanical exfoliation

Physical mechanical exfoliation employs adhesive tapes to isolate atomically thin layers from bulk crystals169,170. It enables the production of both monolayer 2D materials and custom vdWhs, finding increasing application in surface plasmon resonance (SPR) sensors. The process involves: (i) isolating monolayers via sequential cleavage, (ii) transferring exfoliated flakes onto target substrates (e.g., quartz, SiO2/Si), and (iii) for heterostructure fabrication, precisely stacking monolayers with controlled twist angles (as shown in Fig. 2a. Interlayer cohesion in these heterostructures arises solely from vdW interactions.

-

2.

Physical vapor deposition/transport (PVD/PVT)

PVD or PVT refers to technology where in a vacuum environment171,172, vaporize source materials into atomic, molecular, or ionic species, subsequently condensing them onto substrates (as shown in Fig. 2b. Precise control over pressure, source material, and deposition parameters is critical for obtaining high-quality thin films.

-

3.

Chemical vapor deposition (CVD)

Chemical vapor deposition (CVD)173,174 recognized as the benchmark method for controlled synthesis of 2D materials and their heterostructures. This method facilitates precise modulation of growth orientation and crystallinity (as shown in Fig. 2c. Its major advantage lies in the ability to sequentially grow distinct 2D materials atop one another, forming heterostructures with atomically clean interfaces and minimal impurity incorporation.

-

4.

Liquid-Based Techniques

Fig. 2 Production of 2D nanostructures. a Physical mechanical exfoliation method170; Copyright 2021 Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group on behalf of the Korean Information Display Society. b CVD method174; Copyright 2025 Wley & Sons Australia, Ltd. c PVD method172; Copyright 2024 Wiley-VCH GmbH. d Liquid-Based Techniques method176. Copyright 2024 Wiley-VCH GmbH

In addition, Liquid-based exfoliation has emerged as a scalable platform for 2D material production, enabling applications in printed electronics and additive manufacturing175,176.

Ultrasonication of layered precursors in solvents generates inhomogeneous stress, leading to layer separation via pin-hole formation. For air-sensitive materials like BP, stability during processing is enhanced by: (i) surfactant addition or (ii) thermal exfoliation in high-boiling-point solvents matching the material’s surface energy. Challenges in controlling film thickness, lateral dimensions, and surface chemistry often necessitate post-processing for improved monodispersity (as shown in Fig. 2d. Alternatively, ion intercalation precedes mild sonication to weaken interlayer bonding in bulk crystals, yielding larger, higher-quality flakes177. However, this method chemically modifies the material, altering its intrinsic properties, making it suitable for specific application-driven syntheses.

The physical mechanical exfoliation method can produce 2D nanosheets with complete crystal structure, minimal defects, and clean surface. This is crucial for SPR sensors, as defects can introduce non radiative recombination centers, weaken signal enhancement effects, and may lead to non-specific adsorption. The non-destructive lattice ensures the intrinsic and excellent optical and electrical properties of the material, such as the high carrier mobility of graphene, which facilitates efficient plasma exciton coupling or charge transfer, thereby achieving maximum sensitivity enhancement. The process does not involve any chemical reactions, and the obtained nanosheets are very pure, avoiding interference from impurities in the biological recognition process and improving selectivity. The extremely low yield and lack of regulatory modeling are the most fatal drawbacks of this method. The process is cumbersome and highly random, making it difficult to obtain thin films of sufficient size and uniform thickness to cover standard SPR chips, which seriously hinders its application in practical sensors. The size, thickness, and shape of each peeled layer are inconsistent, resulting in significant differences in the performance of sensors based on different chips, making it difficult to ensure reproducibility and almost impossible to standardize production. Accurately and non-destructively transferring micrometer scale peeled thin films to specific locations on SPR chips is a huge technical challenge that is difficult to achieve automated integration. It is mainly used for basic mechanism research to verify the theoretical upper limit of the improvement of SPR performance by 2D materials themselves, but it is almost impossible to use for large-scale manufacturing of actual sensor devices.

PVD (especially sputtering) is very suitable for depositing large-area, uniformly thick continuous thin films (such as metal or dielectric layers of several nanometers) on flat substrates. This highly matches the requirement of uniform coating for SPR chips. Sedimentary particles have high energy, forming a thin film and not easily detached, improving the mechanical stability and service life of the sensor. The vacuum environment avoids pollution, and by precisely controlling the time, and substrate temperature, the film thickness can be well controlled, which is a key parameter for regulating SPR signals. PVD is a standard process in the semiconductor industry that is easy to integrate with other micro-nano processing technologies, laying the foundation for manufacturing miniaturized and arrayed SPR sensors. 2D polycrystalline films prepared by PVD, such as polycrystalline graphene, have more grain boundary defects. Grain boundaries scatter plasma and charge carriers, reducing sensor performance and potentially becoming non-specific adsorption sites. Mainly used for preparing graphene or simpler metal oxides, for complex transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) and other compounds, it is difficult to accurately control the stoichiometric ratio, and the material quality is usually lower than that of CVD method. Expensive vacuum equipment is required, resulting in higher costs. It is an ideal choice for preparing ultra-thin metal protective layers (such as sputtering a layer of ultra-thin graphene on silver film to prevent oxidation) and uniform dielectric reinforcement layers, which are very suitable for standardized and large-scale production of SPR sensor chips. CVD is the most mainstream method for preparing large-area, high-quality, and single crystalline 2D materials, especially graphene and TMDs. Its material quality is much higher than PVD and liquid-phase methods, close to mechanical exfoliation, while also having the potential for scaling up. By optimizing the catalyst, temperature, airflow, and reaction time, precise and controllable growth of single or specific layers can be achieved, which is crucial for finely regulating the sensitivity and operating range of SPR sensors. There are various types of 2D materials that can be prepared, including graphene h-BN、 Multiple TMDs and their heterojunctions provide the possibility to customize SPR sensors for different detection requirements, such as different laser wavelengths. Growth is typically carried out on rigid substrates such as copper foil and SiO2/Si at high temperatures (>800°C). Afterwards, the grown film needs to be transferred onto an SPR chip (usually glass or prism). The transfer process is prone to introducing wrinkles, cracks, contamination, and defects, seriously deteriorating material performance and sensor reproducibility. The equipment is expensive, the process parameters are complex, the requirements for operators are high, and the overall cost is higher than PVD and liquid-phase methods. The interface contact quality and adhesion between the transferred 2D material and the metal film of the SPR chip may not be as good as the film deposited directly by PVD, which may affect stability and thermal management. It is one of the preferred methods for preparing high-performance and high-end SPR sensors. Despite the transfer challenges, the high-quality materials it provides are irreplaceable for applications that pursue extreme sensitivity. Solving non-destructive transfer technology is a key research direction.

The liquid-phase synthesis method has a simple process, low equipment requirements, and can produce 2D material dispersions on a large scale, with significant cost advantages175,178. The obtained nanosheet dispersion can be easily and quickly coated onto SPR chips of any shape and material through various methods such as spin coating, droplet coating, spray coating, Langmuir Blodgett self-assembly, etc., without the need for high temperature and transfer steps, making integration simple. During or after the liquid-phase exfoliation process, it is convenient to perform covalent or non-covalent chemical modifications on the nanosheets, directly attaching biometric molecules to achieve material preparation and functionalization in one step. Liquid phase exfoliation can produce nanosheets with high defect density, small lateral dimensions, and uneven layers. Serious defects and edges will significantly weaken its optoelectronic performance and introduce a large number of non-specific adsorption sites, severely reducing the selectivity and SNR of the sensor. Thin films coated by solution method are usually randomly stacked from nanosheets, which have problems such as pores and non-uniformity, resulting in uneven SPR response and poor reproducibility. The solvents or surfactants used may be difficult to completely remove, and residues can contaminate the sensor surface and interfere with biometric recognition. Very suitable for disposable SPR sensors or test paper products with low performance requirements and extreme cost sensitivity. Strict centrifugal screening and subsequent processing can partially improve material quality, but breakthroughs are still needed to apply it to high-precision detection.

Production of metasurfaces

Metasurfaces are 2D artificial materials composed of nanostructures, which can accurately control the phase, amplitude and polarization of electromagnetic waves (light, microwave, etc.)50. The preparation methods are various, and the appropriate process should be selected according to the material system (metal, medium, composite) and the target function (holography, lens, polarization control). The main preparation methods and detailed steps are as follows:

-

1.

Electron beam lithography (EBL)

Electron Beam Lithography (EBL) is one of the core technologies for fabricating optical metasurfaces. It achieves precise processing of sub-wavelength structures by directly writing nano-patterns on a resist through focused electron beams, combined with subsequent pattern transfer processes (as shown in Fig. 3a. The general steps mainly include substrate preparation, coating, electron beam exposure, development, pattern transfer, and post-processing: Silicon wafers or glass substrates were subjected to successive ultrasonic cleaning in acetone, isopropanol, and deionized water, with subsequent drying using nitrogen gas. An SU-8 2000 photoresist formulation was spin-coated onto substrates, yielding uniform nm-thick films. Pre-exposure baking was performed on a hotplate. Post-exposure baking was intentionally omitted to minimize residual layer formation and prevent thermally induced crosslinking, thereby preserving feature dimensions. Exposed samples were developed at ambient temperature through sequential immersion in: (i) Propylene glycol monomethyl ether acetate, (ii) Isopropanol, (iii) Flowing deionized water rinse. Patterned substrates were dried under a nitrogen stream. Metal nanostructures were obtained by metal deposition and stripping (acetone ultrasound)179.

-

2.

Focused ion beam (FIB)

FIB is a technology that utilizes focused ion beams for material processing at the nanoscale. Its core principle involves bombarding the material surface with ion beams (usually gallium ions) focused to nanometer-sized dimensions, removing material through physical sputtering effects. The general steps for fabricating metasurfaces using FIB mainly include: First, substrate preparation: deposit the target material film (such as 30 nm gold film) on the silicon substrate. Second, ion beam etching: import design patterns into FIB system, select ion source (such as Ga+), set beam current and acceleration voltage. Direct scan etching removes excess metal and forms nanostructures. Third, Cleaning and characterization: the residue was removed by argon ion polishing, and the structural morphology was examined by scanning electron microscope (SEM)180. The core of fabricating FIB-induced metasurfaces lies in the synergistic regulation of physical sputtering and stress deformation, achieving sub-wavelength structure customization through a process of “2D etching → selective bombardment → three-dimensional transformation”.

-

3.

Nanoimprint lithography (NIL)

The principle of nanoimprint technology is mechanical imprint transfer of patterns. It utilizes a mold with nanoscale patterns (usually fabricated through electron beam lithography) to imprint patterns on a substrate coated with resist or other moldable materials. Unlike optical lithography, NIL is not restricted by the diffraction limit, thus enabling higher resolution. Its general process includes (as shown in Fig. 3b): Initially, coat the thickening agent on the cleaned silica chip and subsequently heating on a heating plate. The UV-NIL resist was then coated onto the substrate, followed by UV-NIL using the fabricated fused quartz vertically coupled double-layer gratings (VCDG) mask aligner. Once the calibration is verified, UV exposure is used to crosslink the resist, and optical performance of the cured resist becomes a polymer similar to SiOx. UV resist has low viscosity and is easy to fill during nil to achieve high fidelity pattern transfer at relatively low pressure. After UV-NIL, a mild oxygen plasma process was used to treat the printed resist scaffolds to activate the hydroxyl groups on the surface. Evaporate a layer of Cr, and then deposit Al to form VCDG grating. The high vacuum level helps to obtain a smoother VCDG surface morphology by reducing the residual gas and pollutants in the chamber. Finally, a SiO2 layer was deposited as a packaging layer to avoid further oxidation of the aluminum surface181.

-

4.

Self-assembly technology

Self-assembly is a technique that utilizes intermolecular forces to spontaneously and orderly arrange structures to prepare regular patterns. The application of self-assembly technology in the fabrication of metasurfaces involves designing and controlling the weak interactions between nano/molecular “building blocks” and their interactions with the environment (especially the substrate), guiding these building blocks to spontaneously and large-scale arrange into stable and ordered structures with desired sub-wavelength features and spatial configurations, thereby achieving optical functions of metasurfaces. It primarily relies on non-covalent interactions (such as π-π stacking, etc.) between molecules, nanoparticles, or larger structural units. These interactions are relatively weak but possess directionality and selectivity. Generally, the preparation of metasurfaces using self-assembly technology involves two main steps (as shown in Fig. 4a: First, gold nanoparticles were synthesized by redispersion in deionized water. Second, Silicon/glass substrates were functionalized with sequential Cr adhesion and Au films via magnetron sputtering. These Au-coated substrates were immersed in colloidal dispersion for controlled durations. Electrostatic self-assembly occurs due to the negative surface charge inherent to sputtered Au films, which attracts functionalized Au nanoparticle (positive charge). Consequently, metasurfaces comprising Au film-coupled Au nanoparticle were fabricated. The surface coverage density was precisely modulated by varying immersion time, enabling tunable optical properties182.

-

5.

Direct laser writing (DLW)

Fig. 3 Fig. 4 Laser direct writing is a technique that utilizes computer-controlled high-precision laser beam scanning to directly expose and write any designed pattern on photoresist (in Fig. 4b. The core principle is to achieve precise fabrication of micro-nano structures by utilizing the interaction between laser and materials (such as photopolymerization, ablation, phase transition, etc.). The key processes include: First, Photoresist coating: spin the photoresist (such as SU-8) on the substrate with a thickness of 1–10 μM. Second, Laser exposure: femtosecond laser focused scanning, curing colloid through two-photon polymerization. The design path is controlled by CAD software. Third, Development and metallization: the developer removes the unexposed area to obtain the polymer structure. Sputter metal (such as aluminum) to form a conductive metasurface183.

In conclusion, EBL has the highest resolution (up to several nanometers) and can process metasurface units with extremely complex shapes and extremely small feature sizes. This provides the possibility for designing high-performance resonance modes, such as supporting local surface plasmon LSPR and surface lattice resonance (SLR) coupling, greatly improving the sensitivity and quality factor (FOM) of sensors179. No mask is required, and exposure can be directly based on digital design graphics, which is very suitable for scientific research exploration and prototype verification. Gradient, non-uniform, and encoded metasurfaces can be easily implemented for multifunctional integration, such as simultaneous detection of RI and thickness. The ability to achieve highly consistent structures on a single chip ensures high reproducibility of sensor response, which is crucial for quantitative analysis. Electron beam point-by-point scanning exposure is very slow and not suitable for large-scale production, only suitable for laboratory small-scale preparation. The expensive equipment, high maintenance costs, and complex process (requiring ultra-vacuum environment, etc.) result in extremely high preparation costs for individual chips. Electron scattering can cause unexpected exposure of the resist in non-target areas, affecting the processing fidelity of complex and dense patterns, requiring compensation through algorithms and increasing process difficulty.

FIB can directly engrave metasurface structures on metal thin films without the need for resist and pattern transfer processes. This makes it the fastest method for prototyping single devices/small arrays, making it very suitable for rapid iterative design. Similar to EBL, it has nanometer level machining accuracy, can process any 2D shape, and can be flexibly modified and edited. By controlling the ion beam dose and angle, superatomic particles with 3D contours can be created, providing more degrees of freedom for phase control. Similarly, point by point scanning is even less efficient than EBL, and the equipment is also expensive, making it unsuitable for large-scale production. High energy Ga⁺ ions can be injected into the sample, altering the lattice arrangement and photonic properties of the material, resulting in broadening of the SPR resonance peak, thereby reducing the sensitivity and SNR of the sensor. This is a fatal flaw for high-performance sensing. Usually, it can only process a very small range, making it difficult to prepare large-area uniform metasurfaces.

NIL, once the master is made, can replicate nanostructures at high speed and in large quantities like “stamping”, with a large single imprint area. This is the most promising path to achieve low-cost and commercial mass production of metasurface SPR sensors. The ability to perfectly replicate the nano features of the master plate, with high resolution and excellent batch consistency, ensures high reproducibility of sensor products. It can be processed on substrates such as glass, silicon, and even flexible polymers, providing the possibility for developing flexible and wearable SPR sensors. The production of large-area, defect free nanoimprint master plates requires expensive technologies such as EBL, and the master plates are prone to wear and contamination. Etching errors (multi-layer alignment), uneven filling of resist, and demolding defects can introduce processing defects, affecting the consistency of yield and sensor performance. The optical properties of the imprinting adhesive may not be ideal, and it is usually necessary to use it as a mask and then transfer it to functional materials, which increases the complexity of the process.

Self-assembly is a bottom-up process that allows for parallel formation of nanostructures over a large area, at a much lower cost than any top-down photolithography technique184. Especially with self-assembly, nanolattices or pore arrays with feature sizes<10 nm and extremely high densities can be easily prepared for exciting ultra-sharp resonance modes, which is expected to achieve extremely high sensitivity. In theory, nanostructures can be formed on complex surfaces. Limited structural design and controllability: The types of structures formed are limited by thermodynamic equilibrium states, making it difficult to arbitrarily design complex shaped superatoms and limiting the ability to control optical responses. Long range orderliness problem: self-assembly usually produces polycrystalline domains, which are ordered within domains but have grain boundaries and defects between domains. This can lead to uneven SPR response and poor reproducibility, which is a major obstacle to sensing applications. Process integration and reliability: It is difficult to integrate self-assembled materials with standard complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) processes, and the thermal and mechanical stability of the structure is sometimes poor. It has potential in specific and simple sensing applications, such as SERS detection that requires low consistency of ultra-high density hotspots.

DLW is the only option for creating 3D metasurfaces. Complex 3D structures such as suspended and stacked structures can be constructed, providing a platform for achieving richer light field control, thus developing new SPR sensing modes. Similar to EBL, it belongs to digital direct writing technology and is suitable for prototype development. The resolution can break through the diffraction limit and reach the level of hundreds of nanometers. Although it is a parallel process (two-photon absorption), it still scans point by point, which is slow and not suitable for large-scale production. Usually, polymer templates are processed first, and subsequent metallization steps (such as magnetron sputtering) are required to form plasmonic metasurfaces. The shape retention and surface roughness of metal coatings can affect the final performance. Besides, femtosecond laser systems are expensive. But it also is the core technology for developing the next generation of 3D SPR metasurface sensors. Used to explore sensing mechanisms based on new dimensions such as angular momentum and orbital angular momentum, but currently mainly in the laboratory research stage.

Recent progress of SPR biosensors using composite nanostructures