Abstract

Psychedelics have garnered significant interest for their therapeutic potential in mental health conditions such as depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder. While research has primarily focused on well-studied psychedelics, phenethylamine derivatives have also gathered interest for their potential therapeutic applications. Thus, this study aims to investigate the pharmacological profile, safety and therapeutic potential of novel N-(2-fluorobenzyl) phenethylamine analogs (NBFs) of the 2C-X series—25C-NBF, 25B-NBF, and 25I-NBF. NBFs displayed high affinity and selectivity for the 5-HT2A receptor and demonstrated bias factors (defined in our study as the preference for Gq over β-arrestin pathways at 5-HT2A receptor) similar to that of 5-HT. Acute administration induced moderate head-twitch responses without affecting locomotion or pre-pulse inhibition. Our studies revealed no rewarding effects in mice nor reinforcing effects or changes in accumbal dopamine levels in rats after NBFs administration. Further characterization of 25C-NBF revealed psychoplastogenic effects (dendritogenesis, spinogenesis and increased Bdnf mRNA levels) both in vitro and in vivo. In addition, 25C-NBF reduced despair-like behavior in response to acute stress and exerted rapid antidepressant effects in a model of anhedonia-like behavior induced by chronic corticosterone administration. Taken together, these findings suggest that 25C-NBF, and further analogs, may hold potential as novel antidepressants with a rapid onset of action and a favorable safety profile in terms of no abuse potential or sensorimotor gating deficits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Psychedelics are a class of psychoactive compounds known for their ability to alter perception, mood and consciousness [1]. These compounds have traditionally been associated with spiritual practices, but have recently gained renewed attention for their therapeutic potential in treating various mental health conditions such as depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder [2]. Research in psychedelic compounds has shown promising results, leading to a growing interest in exploring their therapeutic effects in controlled settings [3].

Depression is a widespread and debilitating mental health condition, characterized by persistent low mood or diminished interest in activities, affecting millions worldwide [4]. Despite the availability of several antidepressants, a significant portion of patients fail to achieve adequate relief or experience undesirable side effects [5]. Moreover, a major limitation of conventional antidepressants is their delayed therapeutic onset, often requiring weeks for noticeable improvement [6]. In recent years, interest has grown in the potential of psychedelics, such as psilocybin and dimethyltryptamine (DMT), to provide rapid and long-lasting antidepressant effects [7, 8]. Additionally, these compounds have been shown to induce neural adaptations, including the promotion of synaptic plasticity, which may underlie their therapeutic benefits [9]. Therefore, psychedelics are often referred to as psychoplastogens – a term that describes compounds capable of rapidly promoting structural and functional changes in neural circuits [10]. Moreover, it is known that the prefrontal cortex (PFC) is a key brain region implicated in the pathophysiology of depression [11]. In fact, it is known that the loss of dendritic spines and reduced neuronal plasticity in the PFC are hallmarks of depression [12], therefore compounds capable of reversing these alterations could hold therapeutic promise. In this sense, ketamine, a non-competitive NMDA receptor antagonist with well-documented antidepressant properties, has demonstrated to rapidly increase spine density in the PFC [13]. Similarly, Shao and colleagues [14] reported that a single dose of psilocybin increases spine density and formation rate in the medial frontal cortex of mice.

While much of the current research has focused on well-known psychedelics (e.g. psilocybin, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) and DMT derivatives), other psychedelic compounds, such as certain phenethylamines, have also garnered interest for their potential therapeutic applications. Notably, the 2C-series phenethylamines, first described by Alexander and Anne Shulgin [15], and close analogs, have emerged not only as recreational drugs, but also as compounds with therapeutic interest. Among them, 2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodoamphetamine (DOI) is a potent serotonin 2 A receptor (5-HT2AR) agonist, which has been found to rapidly alleviate depressive-like behaviors in animal models through the promotion of synaptic plasticity [16]. Furthermore, other analogs from the 2C-series, such as N-2-methoxybenzyl-phenethylamines (NBOMes), have also been studied. Particularly, Ferri and coworkers [17, 18] recently reported antidepressant properties of a single dose of 25H-NBOMe or 25H-NBOH (a non-methylated analog). Unfortunately, this class of compounds has been shown to carry a significant risk of abuse [19,20,21,22], which diminishes their potential interest as therapeutic drugs. This highlights the pressing need to identify and develop novel phenethylamines with antidepressant potential that exhibit a reduced risk of adverse effects, including addictive properties. In this sense, very little is known about the pharmacological profile and therapeutic potential of novel N-(2-fluorobenzyl) analogs (NBFs) of the 2C-X series. Thus, the present study aimed to investigate the mechanism of action of 25C-NBF, 25B-NBF, and 25I-NBF, including their interactions with various 5-HT receptor subtypes and their effects on human serotonin (5-HT) and dopamine (DA) transporters (hSERT and hDAT, respectively). More importantly, the study also evaluated the psychedelic effects, rewarding and reinforcing properties of these compounds in vivo, alongside the potential antidepressant activity of 25C-NBF through mouse models of “anxiety-depression”-like behavior induced by physical and pharmacological stress, and its ability to promote neural plasticity both in vitro and in vivo.

Materials and methods

Subjects

Male Swiss CD-1 mice (6–8 weeks old) and Sprague-Dawley rats (10–12 weeks old) were used in this study, and randomly assigned to an experimental group. Animals were housed in climate-controlled rooms under a 12 h light/dark cycle with food and water provided ad libitum, except during specific test sessions. Animal care and experimental protocols applied in this study were approved by the local ethics commitees (Animal ethics Committee of the University of Barcelona and the Animal ethics Committee of the University of Valencia, under the supervision of the Autonomous Government of Catalonia and Comunitat Valenciana, respectively, as well as COMETHEA or Stockholms Norra djurförsöksetiska nämn following the directives of the Swedish Animal Welfare Act 1988:534) and are in accordance with the guidelines of the European Community Council (2010/63/EU), as amended by Regulation (EU) 2019/1010 and the “Principles of Laboratory Animal Care” (NIH publication No. 85-23). All animal procedures comply with the ARRIVE guidelines [23]. All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering and the number of animals used. For further details, refer to Supplementary Material.

Drugs and materials

NBFs were synthetized in racemic form as hydrochloride salts as described in the Supplementary Material. Vehicle consisted of 1% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) in isotonic saline solution. Radioligands were purchased from Revvity Inc. (Boston, MA, USA). 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) was provided by the National Health Laboratory (Barcelona, Spain). All other reagents were of analytical grade and purchased from several commercial sources. See the Supplementary Material for buffers and solutions composition.

In vitro assays

Uptake inhibition assays

The experiment followed our previous protocol [24]. Briefly, HEK293 cells expressing hDAT or hSERT were preincubated with varying drug concentrations in Krebs-HEPES-Buffer (KHB) for 5 min, then exposed to 0.02 µM [³H]MPP⁺ (3 min) or 0.1 µM [³H]5-HT (1 min), respectively. After incubation, cells were washed, lysed with 1% SDS, liquid scintillation cocktail added and radioactivity was measured using a beta-scintillation counter (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA). Non-specific uptake was determined using cocaine (DAT) or paroxetine (SERT). Data represent the mean (% uptake) of five experiments in triplicate.

Release assays

HEK293 cells expressing hSERT were preloaded with 0.1 µM [3H]5-HT in KHB for 20 min at 37 °C. Cells were washed (x3) with KHB and equilibrated for 10 min in KHB or in KHB + monensin (Mon) [25]. Next, cells were incubated with the drug in KHB or KHB + Mon and the resulting supernatant was transferred to a new well every 2 min (x4). Liquid scintillation cocktail was added to each well. Total radioactivity in the remaining cells and supernatant was set as 100%, with each fraction’s radioactivity expressed as a percentage. Assays were performed five times in duplicate.

Competitive binding assays

Competition binding assays were performed as described [26]. Briefly, membranes (10–15 µg of protein content) were incubated with the corresponding compound and radioligand (3 nM [³H]Imipramine for hSERT; 0.4 nM [³H]-8-hydroxy-DPAT for 5-HT1AR; 1 nM [³H]ketanserin for 5-HT2AR; 12 and 1 nM [³H]mesulergine for 5-HT2B/2CR). Non-specific binding was measured using 3 µM paroxetine (hSERT), 10 µM 5-HT (h5-HT1A/2A/2BR), or 10 µM mianserin (h5-HT2CR). Incubation occurred at 22 °C (hSERT) or 27 °C (5-HT receptors) for 1 h, followed by filtration (GF/B glass microfiber pre-soaked with 0.5% polyethyleneimine). Liquid scintillation cocktail was added and trapped radioactivity was quantified. Each experiment was conducted five times in duplicate.

Calcium mobilization assays

CHO/K1 cells expressing human 5-HT2AR were used for functional assays using the Invitrogen™ Fluo-4 NW Calcium Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). Cells were seeded (0.35 million cells/well), incubated with probenecid and the fluorochrome (45 min, 37 °C; 30 min, room temperature), and then treated with compounds. Fluorescence was quantified using a VICTOR Nivo Multimode Plate Reader (Perkin Elmer). Emax was defined as percentage of the 5-HT (10−4M) response. Experiments were performed at least four times in triplicate.

NanoBiT® recruitment assay by means of transient transfection

Cells were transfected with the receptor construct (5-HT2AR fused to the LgBiT component of the NanoBiT® system) and SmBiT-βarr2 or SmBiT-miniGαq, as previously described [27,28,29,30]. After 24 h, cells were seeded into PDL-coated 96-well plates (50 000 cells/well) and incubated for 24 h. Cells were washed twice with Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS), 100 µL of HBSS was added to each well, followed by 25 µL of NanoGlo Live cell reagent (diluted 1/20 in NanoGlo LCS Dilution buffer). Luminescence was measured in a Tristar2LB 942 multimode microplate reader during equilibration. Upon signal stabilization, 10 µL of 13.5x concentrated agonists or solvent controls were added to each well and luminescence was monitored for 2 h. LSD and 5-HT were used as reference agonists. βarr2 and miniGαq assays were conducted in parallel across at least three independent experiments performed in duplicate.

Behavioral assays

Head-twitch response

Mice received the corresponding intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection (vehicle 5 ml/kg, 25C-, 25B- or 25I-NBF 0.3, 1, 3 or 10 mg/kg) and were immediately placed into an open field arena (25 × 25 × 40 cm) and video-recorded. Four trained observers blind to treatment conditions visually scored (with slow-down videos) the number of head-twitch responses (HTR) for 10 min after administration of the corresponding drug.

Horizontal locomotor activity and thigmotaxis

The same animals and assay used for the assessment of HTR were video-monitored for 1 h, and the total travelled distance was measured (Smart3.0, Panlab, Barcelona, Spain). The time spent in the center (8 × 8 cm) or the periphery of the arena was also analyzed.

Pre-pulse inhibition

Startle responses were recorded using two pre-pulse inhibition (PPI) devices (CIBERTEC, S.A., Madrid, Spain) equipped with a loudspeaker, each consisting of a Plexiglas tube with a sensor-equipped platform inside a soundproof chamber. Briefly, mice underwent the PPI test, carried out in three phases; specific conditions summarized in Supplementary Material. PPI was calculated as %PPI = 100 - [(startle with prepulse/startle alone) × 100]. Pre-drug PPI values were used to allocate animals into three groups with similar PPI levels (Supplementary Material Fig. 6). PPI was reassessed immediately and 2 h post-NBF administration. The program included 1 min of 65 dB white noise, followed by 50 trials (120 dB pulse and four prepulse-pulse types, 10 each) in pseudorandom order separated by a 20-s interval, lasting 18 min.

Conditioned place preference

The rewarding effects of the studied compounds (1, 3 and 10 mg/kg, i.p.) were assessed in mice using a place conditioning paradigm, as described [24], at the same doses and administration route as in the locomotor test.

The apparatus consists of a two-compartment chambers (and corridor) with distinct visual and tactile cues. It includes three phases: preconditioning (15-min free exploration), conditioning (drug or saline injections 20 min-paired and counterbalanced with specific compartments over four days), and post-conditioning (15-min free exploration). The preference score was calculated as the time difference spent in the drug-paired compartment before and after conditioning. Mice with a strong initial preference ( > 70% of session time) were excluded (3 mice excluded).

Self-administration

Catheter implantation was performed as described [31]. After recovery, experiments were conducted in MedAssociates operant chambers with retractable levers, cue-lights, and a house light, and controlled and recorded by MedAssociates interfaces and MED-PC IV software (www.medassociates.com). Rats were trained to self-administer methamphetamine (50 µg/kg/injection; 10–15 daily 2h-sessions) before switching to one of the NBFs at a dose of 100 µg/kg/injection, selected based on prior findings [32]. NBFs self-administration was assessed over five consecutive 2h-sessions. All drugs followed a Fixed Ratio 1 (FR1) reinforcement schedule. A single press on the active lever resulted in one intravenous (i.v.) infusion and activated the light (5 s on, 5 s pulsing, followed by a 5 s time-out). Inactive lever presses had no effect.

Microdialysis

Microdialysis experiments were conducted on awake rats, as described previously [33]. Briefly, rats were implanted, under anesthesia with isoflurane, with a guide cannula followed by a microdialysis probe (CMA/12, 0.5 mm o.d., 2 mm membrane, 20 kDa cut-off) in the nucleus accumbens (NAcc) (AP + 2.2 mm; L −1.2 mm; DV −5.6 mm−7.6 mm) and connected to a perfusion system using artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF). The aCSF was pumped with a syringe pump (CMA/100 Microinjection pump) at a flow-rate of 1 µl/min.

After 120 min stabilization, three baseline samples were collected before administering the test compound (3 mg/kg, subcutaneous (s.c.)) or vehicle, and samples were collected for 4 h. Concentrations of DA, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC) and homovanillic acid (HVA) were measured using ultra high-performance liquid chromatography with electrospray tandem mass spectroscopy (UHPLC-MS/MS) as described [31, 34]. For more details, see also Supplementary Material.

Neuroplasticity

Primary cortical neurons and drug treatment

Primary cortical neurons were obtained from E16 embryonic brains and cultured as described in the Supplementary Material. Neurons at DIV4 were exposed to 1, 5 or 10 µM of 25C-NBF or solvent control (0.1% ethanol) for 24 h. The concentrations of 1, 5, and 10 μM were chosen based on previous studies using similar in vitro approaches [10, 35], where 10 μM approximates brain levels achieved by antidepressant doses of related compounds in vivo [36], allowing for relevant and consistent evaluation of NBF-induced neuroplasticity.

Immunofluorescence

At DIV7, cells were fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized (0.1 M PBS containing 0.05% Triton X-100, 10 min) and blocked for 1 h at room temperature in a blocking solution. Cells were washed (x3 PBS containing 0.05% Triton X-100) and incubated overnight at 4 °C with the primary antibody against microtubule associated protein 2 (MAP2; Sigma Aldrich; M4403). The next day, cells were washed and incubated for 45 min at room temperature with the appropriate secondary antibody (Thermo Fisher; A11001). Finally, cells were rinsed with washing solution and the glass slide cover was mounted using mounting medium (Invitrogen; 00-4958-02). Images were collected using a microscope (Leica Thunder Imager; Leica Microsystems) at 20x. A total of 40 neurons from four independent experiments were analyzed.

Analysis of dendritic arbor

The dendritic complexity was analyzed from the acquired images of MAP2 immunocytochemistry, via Sholl-analysis using the plugin SNT of Image J. Neurons were manually outlined and 10 μm was set as the radius step size. The number of intersections between the dendrites and the concentric rings was provided by the software. All replicates used for dendritic arborization originate from independent cultures.

RNA extraction and qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from the treated neurons with TRIzol TRItidy G (A4051; PanReac AppliChem) following a typical phenol-chloroform extraction [37]. Total RNA concentrations were measured on a NanoDrop One/One (ND-ONE-W; ThermoFisher). To obtain cDNA, 1 µg of RNA was reverse transcribed using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (4368814; Applied biosystems) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

To perform the qPCR, 25 ng of the resulting cDNA were added in a 96-well plate together with the Taqman Gene Expression Master Mix (4369016; Applied biosystems) and probes against mouse Bdnf (brain-derived neurotrophic factor; Mm04230607; Applied biosystems), Arc (activity-regulated cytoskeleton-associated protein; Mm00479619; Applied biosystems) and Egr-1 (early growth response protein 1;Mm00656724; Applied biosystems). Mouse Actin B (10546355; Applied biosystems) was used as a housekeeping gene. qPCR was performed on a QuantStudio 3 Real Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using the following protocol: 95 °C for 10 min and then 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, and 60 °C for 1 min. qPCR analyses were conducted in duplicate (n > 3). Fold-change differences were calculated relative to the control group. All replicates used for gene expression analyses originate from independent cultures.

Golgi-Cox Staining

Mice were i.p. injected with vehicle or 25C-NBF (10 mg/kg) and euthanized 24 h post-injection by cervical dislocation. Brains were processed according to the FD Rapid GolgiStainTM Kit (FD Neurotechnologies, Inc., Columbia, MD, USA) and sectioned (100 µm). Images were obtained with a microscope (Leica Thunder Imager; Leica Microsystems). The quantification of dendritic spines was carried out in the anterior cingulate (AC) and prelimbic (PL) cortex of the PFC and in the dentate gyrus (DG) and CA1 region of the hippocampus. Five neurons per zone and animal were selected and dendritic spines were quantified both in the terminal fragment and in secondary branches. Spine density was analyzed as described [38] and expressed as the number of spines per 30 µm of dendrite. Six animals per group were analyzed.

Behavioral Assessment of Antidepressant Effects in Mice

Models of induction of depression/stress-like behaviors

The antidepressant effects of 25C-NBF were studied in two different models of induction of depression-like behaviors in mice; acute restraint stress (ARS) and corticosterone (CORT)-induced depression models.

Acute Restraint Stress mouse model

The physical restraint was performed in mice as previously reported [39], with minor modifications (5 h instead of 4, to ensure a significant stress response). Mice were exposed to 5 h physical restraint in an individual rodent restraint device to evaluate the behavioral impact of an acute stressor. After, mice were immediately administered with either vehicle or 25C-NBF and returned to their home cage.

Corticosterone-induced depression in mice

Mice were subjected to 21 days of s.c. administrations of CORT (20 mg/kg) to induce a “depression-like” state. The dose was based on literature data [40]. CORT was dissolved in vehicle containing 0.1% DMSO and 5% Tween-80.

Tail Suspension Test

Control mice, depression-induced mice, and mice treated with 25C-NBF (10 mg/kg, i.p.) following CORT administration or ARS were individually suspended by their tails for 6 min 24 h and one-week after drug treatment. Three observers, blinded to the treatment assignment, manually assessed the immobility time during the last 4 min.

Sucrose Preference Test

The procedure was performed as previously described [41], with some modifications. For baseline measurements, mice were singly housed and given access to two bottles – one containing tap water and one with a 1% sucrose solution- for 14 h, starting 1–2 h begore the dark cycle, with bottle positions swapped the next day. Preference (%) is calculated as (weight of 1% sucrose solution consumed/total liquid weight consumed)x100. Mice were then group housed, and a depression-like phenotype was induced by daily s.c. injections of 20 mg/kg of CORT for 21 days. Sucrose preference was re-tested before and 24 h after treatment with vehicle or 25C-NBF (10 mg/kg, i.p.). As a priori criteria, mice had to have a preference for sucrose of >65% at baseline (4 mice excluded) and display a preference of <70% and at least a 10% decrease in sucrose preference on the confirmation of anhedonia (13 mice excluded); for more details refer to Supplementary Material Fig. 11.

Data and statistical analysis

Non-linear regression was used to fit competition and concentration-response curves, and data were best fitted to a sigmoidal curve to obtain an IC50, EC50 and Emax values. Selectivity ratios were calculated as (1/DAT IC50 : 1/SERT IC50) and (1/5-HT2AR Ki : 1/5-HT1A/2C/2BR Ki). The affinity constant (Ki) was calculated using the Cheng-Prusoff equation: Ki = EC50/(1 + [radioligand concentration/Kd] [42]. Data from batch release assays were statistically analyzed with a mixed-effects model, employing Šidák’s correction for multiple comparisons. Efficacy was calculated as a percentage of 5-HT or LSD maximum response. Bias factors were calculated using the “intrinsic relative activity” (Rai) approach [29, 43, 44], defined as the quotient between the Emax/EC50 ratio of the test compound and the Emax/EC50 ratio of the reference agonist:

The RAi values from each pathway were then combined to obtain the bias factor (βi):

Which, by definition, is equal to 0 for the reference agonist; >0 relative tendency towards βarr2 recruitment (relative to the reference agonist); or <0 towards miniGαq recruitment. Normal distribution was tested before selecting statistical tests used for analysis. Statistical differences in the HTR experiment were determined using Kruskall-Wallis followed by Dunn’s test. For the rest of the experiments, one way/two-way ANOVA of repeated measures, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test if F was significant, was used when appropriate. The α-error probability was set at 0.05 (p < 0.05). GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad software, San Diego, CA, USA) was used for statistical analysis. The sample size was determined using GPower software. For clarity purposes, all statistical results are presented in Supplementary Material.

Results

NBFs exhibit high selectivity for 5-HT2AR and low DAT/SERT ratios

The IC50 values for DA and 5-HT uptake inhibition assays, binding affinities for hSERT and 5-HT receptors and EC50 and Emax values for 5-HT2AR-mediated calcium efflux are summarized in Table 1 and depicted in Fig. 1. All tested NBFs showed micromolar potency at inhibiting 5-HT uptake but much lower potency at hDAT (Fig. 1D, E), resulting in low DAT/SERT ratios. Moreover, all NBFs showed higher hSERT affinity than MDMA (Fig. 1D) without evoking 5-HT release (Fig. 1F and Supplementary Material Fig. 2). Specifically, hSERT affinity increases with halogen volume. NBFs showed higher affinity for the 5-HT2A/2B/2CR compared to both MDMA and DMT (Fig. 1H-K). Regarding 5-HT1AR, all NBFs showed higher affinity than MDMA but lower than DMT. Moreover, the NBFs showed a high selectivity for 5-HT2AR over 5-HT1AR, but also moderate over 5-HT2B/2CRs. Decreasing the volume of the halogen group increased 5-HT2A/2BRs affinity; whereas there is no clear tendency for 5-HT1AR. For 5-HT2CR, all compounds showed similar affinities. Moreover, all tested compounds showed >90% efficacy and equal potency in 5-HT2AR activation-induced calcium mobilization (Fig. 1L).

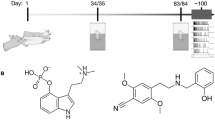

Structures of 25C-NBF (A), 25B-NBF (B) and 25I-NBF (C). Concentration-effect curves of 25C-NBF, 25B-NBF, 25I-NBF on [3H]MPP + uptake at hDAT (D) and [3H]5-HT uptake at hSERT (E) in comparison with MDMA. Data are expressed as percentage of control uptake (absence of compound). Effect of 25C-NBF on transport-mediated release of preloaded [3H]5-HT from HEK293 cells stably expressing hSERT (F). MON = monensin. Competition [3H]Imipramine binding curves of NBFs compounds at hSERT in comparison with MDMA (G). Competition [3H]8-OH-DPAT, [3H]Ketanserin and [3H]Mesulergine binding curves of 25C-NBF, 25B-NBF and 25I-NBF at 5-HT1AR (H), 5-HT2AR (I) and 5-HT2B/2CR (J and K), respectively, in comparison with DMT and MDMA. Data are expressed as percentage of control binding (absence of compound). 5-HT2AR-mediated calcium mobilization assay of the tested NBFs and reference compounds 5-HT (full agonist) and DA (partial agonist) (L). Concentration-response curves of NBFs in the β-arrestin 2 (M) and miniGαq (N) recruitment assays at the 5-HT2AR normalized to the Emax of LSD. All data are expressed as means ± SD for n ≥ 3 experiments.

NBFs show similar potency than LSD at βarr2 recruitment, with a bias factor resembling 5-HT at 5-HT2AR

To elucidate the precise mechanism at 5-HT2AR, two analogous in vitro bioassays were performed, βarr2 and miniGαq protein recruitment [45]. The EC50 and Emax values (normalized to the Emax of LSD) are summarized in Table 1; for Emax values normalized to the Emax of 5-HT refer to Supplementary Material Table 1. All NBFs displayed nanomolar potency at 5-HT2AR in both βarr2 and miniGαq assays, consistent with a previous study using 25I-NBF [27]. The halogen substituent had no impact in the potency or efficacy in these assays, except for a slightly lower Emax in the miniGαq assay for 25I-NBF. All compounds tested showed similar efficacies and potencies in the βarr2 recruitment assay. Although all NBFs appear to be 2-–3-fold less potent than LSD in the miniGαq recruitment assay, the overlap of confidence intervals suggests comparable potencies. Additionally, 25C- and 25B-NBF showed similar efficacy to LSD in the miniGαq recruitment assay (Fig. 1M, N). Moreover, the calculated β-factor values relative to LSD of all the NBFs compounds are >0, similar to the bias factor obtained for 5-HT. Lastly, EC50, Emax and β-factor values of LSD and 5-HT align with previous studies [27,28,29].

NBFs induce head-twitches but do not affect locomotion or sensory-motor desynchronization in mice

Acute i.p. administration of 3 and 10 mg/kg of all tested NBFs significantly increased the HTR (Fig. 2B-D), suggestive of psychedelic effects in humans [46]. Figure 2A serves as an illustrative representation of the HTR. Analysis of HTR counts for 25C-NBF across consecutive 10 min intervals revealed that the peak response occurred within the first 10 min post-administration, followed by a time-dependent decline (Supplementary Material Fig. 3). Moreover, none of the doses tested affected locomotion (Fig. 2F-H) nor induced thigmotaxis (Supplementary Material Fig. 5). Figure 2E shows a representative 1 h ambulation tracking. For horizontal locomotor activity (HLA) time-courses see Supplementary Material Fig. 4. Additionally, acute i.p. administration of 1 or 10 mg/kg 25C-NBF did not impair PPI of the startle reflex in short-PPI acute nor in the PPI session repeated after 2 h, thus suggesting no sensory-motor desynchronization (Fig. 2J). Figure 2I depicts the PPI procedure.

Graphical representation of HTR (source: image generated using DALL·E (OpenAI) and modified in PowerPoint, (A) and number of head-twitch events during a 10-min period for all NBFs tested (B-D). Data are presented as means ± SD. **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 vs vehicle, #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01 and ###p < 0.001 vs 0.3 mg/kg, $p < 0.05 and $$p < 0.01 vs 1 mg/kg (Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s test). n = 11–12/group. Tracking of the ambulation of one representative mouse for each experimental group of 25C-NBF (E) and effects of NBFs on cumulative locomotor activity in mice (ANOVA) (F-H). Data are presented as means ± SD of the total distance travelled in 60 min. n = 11–12/group. Representative scheme of the PPI procedure (I) and effects of 25C-NBF i.p administration (1 and 10 mg/kg) on PPI (J) (mixed-effects model). Data are presented as mean ± SD. n = 10–12/group.

NBFs do not induce rewarding nor reinforcing effects in rodents

The conditioned place preference (CPP) paradigm assessed the rewarding effects of 25C-, 25B- and 25I-NBF. On the test day, none of the compounds showed preference for the drug-paired compartment at any dose (Fig. 3A-C). Figure 3D summarizes CPP procedure. For self-administration studies, baseline methamphetamine self-administration levels (16–19 injections/session) were similar across groups. When substituted with NBFs, the number of injections obtained were not significantly different from vehicle treated mice as demonstrated by a lack of significant effect of treatment (Fig. 3E). Moreover, statistical analysis revealed a significant effect of the variable session (see statistical results in Supplementary Material) but no significant effect was observed in the interaction session x treatment. Therefore, NBF-treated rats behaved in a similar manner as the control group, suggesting a lack of reinforcing effects. The self-administration experiment is represented in Fig. 3F. Moreover, no changes in DA levels (Fig. 3G) nor its metabolites (Supplementary Material Fig. 7) were detected in the NAcc of awake rats after acute s.c. administration of 3 mg/kg of any of the phenethylamines tested. Figure 3H shows a schematic illustration of the probe placement in the rat NAcc.

Effects of 25C-NBF (A), 25B-NBF (B) and 25I-NBF (C) on the CPP test in mice, and graphical representation of the CPP test (D). Bars represent the mean ± SD of the preference score (difference between the time spent in the drug-paired compartment on the test day and the preconditioning day), (ANOVA). n = 10–12/group. Self-administration of different phenethylamines in rats trained to self-administer methamphetamine (E), and graphical representation of the self-administration experiment (F). Number of single press on the active lever by different cohorts of rats after establishing a baseline of self-administration with methamphetamine (50 μg/kg/inj), which was then substituted with 25C-NBF (100 μg/kg/inj), 25B-NBF (100 μg/kg/inj), 25I-NBF (100 μg/kg/inj), or their vehicle (1% DMSO in sterile saline) for five 2 h sessions. (Two-way ANOVA). n = 7–8/group. Extracellular levels of DA (G) in the NAcc of awake rats treated with NBFs (3 mg/kg s.c.) (mixed effects model, n = 4–6/group), and schematic illustration of the probe placement in the NAcc of a rat (H). Images source: images adapted and/or modified from Servier Medical Art, CC BY 3.0, via https://smart.servier.com (D,F) and from the Rat Brain Atlas by Gaidica [88] (H).

25C-NBF induces dendritogenesis and induction of neural plasticity genes in vitro as well as spinogenesis in vivo

Mouse primary cortical neurons treated with 1, 5 and 10 µM of 25C-NBF exhibited a higher number of crossings and, consequently, an increase of the area under the curve (AUC; Fig. 4B). Treatment with 5 and 10 µM significantly increased the total number of crossings and primary dendrites (Fig. 4C, E), while 10 µM also significantly enhanced the total number of branches and dendritic length (Fig. 4D, F). However, no changes were observed in the number of secondary/tertiary dendrites nor in the length of the longest dendrite (Supplementary Material Fig. 8). Moreover, 10 µM 25C-NBF significantly increased Bdnf expression 2 h after treatment (2-fold-change) (Fig. 4G) (30 min results at Supplementary Material Fig. 9A). However, no significant changes were detected in the expression levels of Arc nor Egr-1 (Supplementary Material Fig. 6B-C).

Representative images of untreated neurons and neurons treated with 10 µM of 25C-NBF at DIV 7 (A). Sholl analysis showing dendritic branching and its AUC (inlet) (B). Quantitative parameters include: maximum number of dendrite crossings (C), total number of branches (D), total number of primary dendrites (E), and total dendritic length (F). Data are presented as mean ± SD of 4 independent cultures (10 neurons/culture; total of 40 neurons/group). One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs control and #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 vs solvent control). Bdnf mRNA expression induced by 25C-NBF in primary cortical neurons (G). Data are expressed as the mean ± SD of fold changes in Bdnf mRNA levels. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test * p < 0.05 vs solvent control. n = 5/group. Quantification of dendritic spines of each 30 µm of dendrite in the anterior cingulate (H, J) and the prelimbic cortex (I, K), and representative images of each experimental group. Data are presented as mean ± SD of 6 animals/group (5 neurons per zone and animal). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 (student’s t-test).

Encouraged by the promising effects observed in vitro, we examined the impact of an acute administration of 10 mg/kg of 25C-NBF on spinogenesis in vivo. Acute treatment with 25C-NBF significantly increased spinogenesis in both the AC and PL regions of the mouse prefrontal cortex (Fig. 4H-K), suggesting enhanced cortical synaptic plasticity. In the hippocampus, spinogenesis increased in the DG but not in the CA1 region (Supplementary Material Fig. 10).

25C-NBF induces fast antidepressant effects in mice

Building upon observed effects of 25C-NBF on dendritogenesis and spinogenesis, we reasoned 25C-NBF may possibly exert antidepressant effects. First, we assessed the antidepressant effects of 25C-NBF in an ARS mouse model (Fig. 5A). 25C-NBF administration significantly reduced immobility time in the tail suspension test (TST) at both 24 h and one-week post-administration, compared to the stress-induced (restraint) control group (Fig. 5B, C). Additionally, as an alternative strategy, we employed a CORT-induced depression mouse model (Fig. 5D, G). In this model, the TST also revealed a significant reduction in the immobility time 24 h after 25C-NBF administration (Fig. 5E). However, no significant differences were observed among groups one-week post-administration (Fig. 5F). Using the same CORT-induced depression mouse model, the sucrose preference test (SPT) (Fig. 5G) confirmed an anhedonia state through a significant reduction in sucrose preference, which was rapidly restored by administration of 10 mg/kg of 25C-NBF (Fig. 5H).

Effect of 25C-NBF on freezing behavior in an acute restraint stress (ARS) and CORT-induced depression-like model (A and D, respectively) in mice 24 h (B, E) and 7 days after acute administration (C, F) (One-Way ANOVA with Tukey’s test). Data are presented as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 (ANOVA with Tukey’s test). n = 13–21/group. Restoration of hedonic behavior after chronic stress 24 h post-administration of 25C-NBF (10 mg/kg), assessed by the SPT (G, H). Data are presented as mean ± SD. ***p < 0.001 vs corresponding baseline and ##p < 0.01 vs corresponding CORT-treated mice (Two-Way ANOVA with Tukey’s test). n = 12/group. Images source: images adapted and/or modified from Servier Medical Art, CC BY 3.0, via https://smart.servier.com.

Discussion

Treatment-resistant depression remains a major concern, with many patients unresponsive to current antidepressants. Additionally, the delayed therapeutic effects remain an issue [6]. Psychedelics - including ergoline, tryptamine and phenethylamine derivatives - are emerging as promising therapeutic alternatives [47]. However, certain phenethylamine-based psychedelics are recreationally abused, underscoring the necessity for thorough investigation of their pharmacological and toxicological profiles to ensure safety and efficacy [48]. Addressing this need, the present study comprehensively assesses the pharmacological properties of novel phenethylamines 25C-, 25B- and 25I-NBF, highlighting their potential therapeutic benefits alongside a lack of abuse potential and preserved sensorimotor coordination.

Our results demonstrated that NBF compounds potently interact with the 5-HT receptor system, highlighting a heightened affinity, agonist activity and selectivity for 5-HT2AR, one of the main plausible therapeutic targets of psychedelics for treating mental health conditions [49, 50]. Particularly, increased 5-HT2AR affinity over 5-HT1AR, compared to tryptamine-based psychedelics (i.e. DMT), has also been reported for other phenethylamines such as 2C-X derivatives [51]. Moreover, hallucinogenic effects of psychedelics are described to be mediated by activation of 5-HT2AR [26, 52]. In rodents, the HTR is a fast side-to-side rotational head movement used as a marker of hallucinogenic effects in humans [46]. Our results demonstrated that acute i.p. administration of 25C-, 25B- and 25I-NBF induce HTR in mice, suggesting similar hallucinogenic behavior among compounds. Notably, as observed for 25C-NBF, the peak HTR response occurred within the first 10 min post-administration, indicating a rapid onset of action and supporting the use of this time window to assess their maximal effect. HTR, as measured immediately after administration, induced by other phenethylamine-based psychedelics (e.g., NBOMes, NBOHs) has been reported in rodents [53, 54], however, the interspecies and intrastrain variability in these studies complicates direct comparisons. Notably, under identical experimental conditions—species, strain, HTR procedure, dose, and route of administration—our group previously reported that 5-MeO-DMT, a tryptamine-based psychedelic currently in clinical trials [55, 56], induces approximately 30 HTRs in 10 min [26]. In contrast, the tested NBFs elicited ~15 HTRs, suggesting a lower hallucinogenic response. The relatively moderate HTR observed compared to other tryptamine-based psychedelics could be due to the compounds’ affinity for the 5-HT2CR, as its activation has been shown to attenuate HTR in mice [57]. However, 5-HT2CR’s role in modulating HTR appears complex, as bimodal effects have been reported depending on the dose of 5-HT2CR antagonist before psilocybin treatment [58]. Beyond that, biased agonism has also been proposed as a key mechanism underlying the psychedelic and therapeutic properties of some 5-HT2AR agonists [27, 59, 60]. Psychedelics like LSD and 5-MeO-DMT activate both Gq and β-arrestin2 pathways via 5-HT2AR, though their specific roles remain unclear [61]. Our findings suggest that NBFs and LSD have comparable potencies in β-arrestin2 and Gq recruitment assays. While their EC50 values for Gq recruitment partially overlap, absolute values indicate NBFs may be slightly less potent than LSD. Moreover, all tested NBFs showed bias factors ( >0 relative to LSD) similar to 5-HT. Wallach and coworkers [62], recently demonstrated a positive relationship between 5-HT2A-Gq efficacy and HTR in structural related phenethylamines, whereas a β-arrestin-biased agonism would reduce psychedelic effects. In our experiments, all NBFs showed reduced Gq efficacy relative to 5-HT but still induced moderate HTR. However, differences in Gq recruitment assays protocols prevent direct comparison with our results. Further investigation is needed to clarify the factors behind psychedelics’ hallucinogenic effects.

5-HT2BR agonism has been associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes [63], prompting the FDA to issue guidance for industry on clinical investigations for psychedelics, strongly recommending the evaluation of binding to 5-HT2BR due to its link to heart valvulopathy [64]. In this sense, the high selectivity ( >100-fold) for 5-HT2AR over the 5-HT2BR observed for all NBFs underscores their favorable safety profile.

Several studies have reported that phenethylamines reduce locomotor activity, potentially reflecting hallucinogenic activity in mice [26, 65]. Wojtas and colleagues [66] suggested that this hypolocomotion may reflect fear/anxiety in novel settings and increased center avoidance induced by these substances. The absence of hypolocomotion and thigmotaxis observed for all NBFs may be attributed to their lower 5-HT1AR affinity compared to other psychedelics, particularly tryptamine-based psychedelics, known to reduce locomotion [26]. However, 25C-, 25B- and 25I-NBOMe, selective 5-HT2AR agonists, have been shown to dose-dependently suppress locomotor activity [66, 67]. Additionally, Tirri and coworkers [68] reported that NBOMe derivatives disrupt sensorimotor gating (PPI) in mice, similar to LSD. Our findings reveal that 25C-NBF did not cause sensory-motor desynchronization, a translational response of the potential “trance-like” behavior typical of users who abuse hallucinogenic substances. This lack of effect contrasts with structurally related phenethylamines [68] and other psychedelics known to disrupt PPI [69, 70].

Phenethylamines, including MDMA and the 2C-X series, have been widely used recreationally [71], with many posing significant abuse risk, limiting their viability and safety as therapeutic agents. For instance, NBOMe drugs have shown abuse potential in rodents [19,20,21,22, 72]. Moreover, the DA system is widely known to be highly associated with substance use disorder [73], with the NAcc being a crucial structure in reward development [74]. Previous studies have also reported that some NBOMe derivatives increase DA in the NAcc [22, 75, 76]. Our findings revealed that the tested NBFs had little to no effect at inhibiting DAT and very low DAT/SERT ratios in vitro, suggesting low abuse potential [77]. Further in vivo microdialysis experiments revealed no significant DA increases in the NAcc of awake rats after acute NBF administration. Moreover, unlike other 2C-X analogs [21, 22], none of the NBFs significantly increased preference scores in the CPP paradigm, indicating no reward-inducing properties. Additionally, NBF substitution after methamphetamine self-administration reduced injection numbers, comparable to the saline group, suggesting minimal to no reinforcing effects. Our findings partially differ from those of Hur and colleagues [32], who reported that extinction of self-administration behavior was slower for 25C-NBF than for vehicle. However, this is mostly due to their unusually fast extinction in the vehicle group whereas the 25C-NBF curve is actually very similar to ours showing decreased drug seeking and drug taking overtime, indicating that 25C-NBF does not maintain self-administration. Altogether, our findings highlight the improved safety profile of the tested NBFs, evidenced by minimal DAT inhibition and accumbal DA increases, low DAT/SERT ratios, absence of reward-inducing properties, and lack of reinforcing effects, suggesting reduced abuse potential. Additionally, their high affinity for the 5-HT2CR, a promising target for substance use disorder treatment [78, 79], may indicate an interesting area for further research.

The high affinity of NBFs for the 5-HT2AR together with their mild hallucinogenic effects - compared to other psychedelics under clinical trials - absence of changes in locomotion and sensory-motor desynchronization nor addictive effects, makes them promising candidates for further investigation of their potential therapeutic properties. In this context, we focused on 25C-NBF, the phenethylamine with the greatest 5-HT2AR affinity and selectivity. Given the link between psychedelic use and increased neuroplasticity (for a review see Calder and Hasler, 2023 [80]), we first evaluated, in vitro, 25C-NBF’s effects on dendritic branching and neuroplasticity-related genes. Our findings indicate that 25C-NBF enhances dendritic arbor complexity and increases Bdnf mRNA levels in primary cortical neurons, highlighting its potential as a psychoplastogen. It must be pointed out that although DIV4 represents an early developmental stage, it provides a sensitive window to detect subtle drug-induced changes in dendritic growth, a strategy widely employed in studies of rapid-acting antidepressants [35, 81], while acknowledging that extrapolation to adult cortical plasticity should be made cautiously. Moreover, we investigated the impact of 25C-NBF on in vivo dendritic spinogenesis, a cellular process impaired in depression [12]. Acute administration promoted spinogenesis in key mood-regulation regions, including the AC and PL cortex. This suggests a potential mechanistic link between 25C-NBF and structural plasticity, similar to other fast-acting antidepressants such as ketamine [82] and tryptamine-based psychedelics [14, 50, 83].

The ability of 25C-NBF to modulate neuroplasticity prompted us to investigate whether it could produce antidepressant outcomes similar to other psychedelics [18, 41, 50]. Thus, we assessed the antidepressant-like effects of 25C-NBF using established behavioral paradigms sensitive to antidepressant treatments [84, 85] applying two complementary approaches. The ARS paradigm was used as a tool to evaluate the behavioral response to an acute stressor, since altered stress reactivity is a core feature of depression. This approached allowed us to assess whether 25C-NBF could modulate stress-induced behavioral changes in a short-term context, complementing the chronic corticosterone model, in which a depression/anhedonia-like phenotype is pharmacologically induced. In the ARS paradigm, administration of 25C-NBF (10 mg/kg, i.p.) significantly reduced despair behavior in the TST compared to restrained control mice, both 24 h and one-week post-administration. In the CORT-model, administration of 10 mg/kg 25C-NBF restored both despair and hedonic behavior in the TST and SPT, respectively, and demonstrated significant antidepressant effects within 24 h. These effects align with those reported for other psychedelics, such as 5-MeO-DMT and DMT at the same dose [10, 50]. Finally, although no persistent effects were observed one-week after CORT treatment, it must be pointed out that CORT-treated animals did not exhibit despair behaviors at this time point, which hindered the ability to assess the drug’s antidepressant effects. Including alternative models involving social and/or environmental stressors will also provide valuable, ethologically and complementary insights, particularly regarding the compound’s sustained or long-term effects. Our results provide initial evidence of its therapeutic potential; however, further studies using additional behavioral and mechanistic approaches will be necessary to fully characterize its therapeutic potential.

Taken together, our findings suggest that 25C-NBF exhibits promising antidepressant properties with a rapid onset of action, supported by its ability to modulate neuroplasticity and restore behavioral deficits in preclinical models of depression. Its therapeutic efficacy, selectivity for 5HT2AR vs 5HT2BR, and lack of abuse potential and sensorimotor desynchronization, underscores its promise as a safer alternative in the realm of psychedelic-assisted treatments for depression. Nevertheless, further studies are warranted to optimize dosing regimens, assess non-hallucinogenic doses, evaluate repeated administration effects, and elucidate the underlying molecular pathways contributing to its antidepressant and neuroplasticity-promoting properties. Moreover, the present study is limited to male mice, which represents a limitation in light of the fact that human females are generally more susceptible to depression-related disorders [86]. However, previous studies have reported greater synaptic plasticity and antidepressant effects in female mice following a single administration of psilocybin or ketamine [14, 87]. This suggests equal or enhanced efficacy in females, warranting further investigation. Overall, the present study underscores that NBFs analogs might emerge as novel and compelling candidates for further research into their therapeutic potential for treating mood disorders, particularly treatment-resistant depression, and may also open avenues for exploring broader applications within this class of phenethylamines.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Nichols DE. Psychedelics. Pharmacol Rev. 2016;68:264–355.

Grieco SF, Castrén E, Knudsen GM, Kwan AC, Olson DE, Zuo Y, et al. Psychedelics and neural plasticity: therapeutic implications. J Neurosci. 2022;42:8439–49.

Geyer MA. A brief historical overview of psychedelic research. Biol Psychiatry: Cognit Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2024;9:464–71.

World Health Organization (WHO). Depression. https://www.who.int/health-topics/depression#tab=tab_1. Accessed date 25-02-2025.

Voineskos D, Daskalakis ZJ, Blumberger DM. Management of treatment-resistant depression: challenges and strategies. Neuropsychiatric Dis Treat. 2020;16:221–34.

Al-Harbi KS. Treatment-resistant depression: therapeutic trends, challenges, and future directions. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012;6:369–88.

Carhart-Harris RL, Bolstridge M, Day CMJ, Rucker J, Watts R, Erritzoe DE, et al. Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: six-month follow-up. Psychopharmacology. 2018;235:399–408.

Palhano-Fontes F, Barreto D, Onias H, Andrade KC, Novaes MM, Pessoa JA, et al. Rapid antidepressant effects of the psychedelic ayahuasca in treatment-resistant depression: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Psychological Med. 2019;49:655–63.

Olson DE. Psychoplastogens: a promising class of plasticity-promoting neurotherapeutics. J Exp Neurosci. 2018;12:1179069518800508.

Ly C, Greb AC, Cameron LP, Wong JM, Barragan EV, Wilson PC, et al. Psychedelics promote structural and functional neural plasticity. Cell Rep. 2018;23:4889–499.

Pizzagalli DA, Roberts AC. Prefrontal cortex and depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2022;47:225–46.

Qiao H, Li MX, Xu C, Chen HBin, An SC, Ma XM. Dendritic spines in depression: what we learned from animal models. Neural Plasticity. 2016;2016:8056370.

Li N, Liu RJ, Dwyer JM, Banasr M, Lee B, Son H, et al. Glutamate N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists rapidly reverse behavioral and synaptic deficits caused by chronic stress exposure. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69:754–61.

Shao LX, Liao C, Gregg I, Davoudian PA, Savalia NK, Delagarza K, et al. Psilocybin induces rapid and persistent growth of dendritic spines in frontal cortex in vivo. Neuron. 2021;109:2535–44-e4.

Shulgin AT, Shulgin Ann. Pihkal : a chemical love story. Transform Press 1991.

de la Fuente Revenga M, Zhu B, Guevara CA, Naler LB, Saunders JM, Zhou Z, et al. Prolonged epigenomic and synaptic plasticity alterations following single exposure to a psychedelic in mice. Cell Rep. 2021;37:109836.

Ferri BG, de Novais CO, Rojas VCT, Estevam ES, Dos Santos GJM, Cardoso RR, et al. Psychedelic 25H-NBOMe attenuates post-sepsis depression in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2024;834:137845.

Ferri BG, de Novais CO, Bonani RS, de Barros WA, de Fátima Â, Vilela FC, et al. Psychoactive substances 25H-NBOMe and 25H-NBOH induce antidepressant-like behavior in male rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2023;955:175926.

Jo C, Joo H, Youn D-H, Kim JM, Hong Y-K, Lim NY, et al. Rewarding and reinforcing effects of 25H-NBOMe in Rodents. Brain Sci. 2022;12:1490.

Lee JG, Hur KH, Hwang SBin, Lee S, Lee SY, Jang CG. Designer drug, 25D-NBOMe, has reinforcing and rewarding effects through change of a dopaminergic neurochemical system. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2023;14:2658–66.

Seo JY, Hur KH, Ko YH, Kim K, Lee BR, Kim YJ, et al. A novel designer drug, 25N-NBOMe, exhibits abuse potential via the dopaminergic system in rodents. Brain Res Bull. 2019;152:19–26.

Custodio RJP, Sayson LV, Botanas CJ, Abiero A, You KY, Kim M, et al. 25B-NBOMe, a novel N-2-methoxybenzyl-phenethylamine (NBOMe) derivative, may induce rewarding and reinforcing effects via a dopaminergic mechanism: evidence of abuse potential. Addiction Biol. 2020;25:e12850.

Percie du Sert N, Hurst V, Ahluwalia A, Alam S, Avey MT, Baker M, et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: updated guidelines for reporting animal research. Exp Physiol. 2020;105:1459–66.

Nadal-Gratacós N, Alberto-Silva AS, Rodríguez-Soler M, Urquizu E, Espinosa-Velasco M, Jäntsch K, et al. Structure–activity relationship of novel second-generation synthetic cathinones: mechanism of action, locomotion, reward, and immediate-early genes. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:2766.

Alberto-Silva AS, Hemmer S, Bock HA, Alves da Silva L, Scott KR, Kastner N, et al. Bioisosteric analogs of MDMA: improving the pharmacological profile? J Neurochem. 2024;168:2022–42.

Puigseslloses P, Nadal-Gratacós N, Ketsela G, Weiss N, Berzosa X, Estrada-Tejedor R, et al. Structure-activity relationships of serotonergic 5-MeO-DMT derivatives: insights into psychoactive and thermoregulatory properties. Mol Psychiatry. 2024;29:2346–58.

Pottie E, Dedecker P, Stove CP. Identification of psychedelic new psychoactive substances (NPS) showing biased agonism at the 5-HT2AR through simultaneous use of β-arrestin 2 and miniGαq bioassays. Biochemical Pharmacol. 2020;182:114251.

Pottie E, Poulie CBM, Simon IA, Harpsøe K, D’Andrea L, Komarov IV, et al. Structure-activity assessment and in-depth analysis of biased agonism in a set of phenylalkylamine 5-HT2A receptor agonists. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2023;14:2727–42.

Poulie CBM, Pottie E, Simon IA, Harpsøe K, D’Andrea L, Komarov IV, et al. Discovery of β-arrestin-biased 25CN-NBOH-derived 5-HT2AReceptor agonists. J Medicinal Chem. 2022;65:12031–43.

Pottie E, Cannaert A, Van Uytfanghe K, Stove CP. Setup of a Serotonin 2A Receptor (5-HT2AR) bioassay: demonstration of its applicability to functionally characterize hallucinogenic new psychoactive substances and an explanation why 5-ht2ar bioassays are not suited for universal activity-based screening. Anal Chem. 2019;91:15444–52.

Nadal-Gratacós N, Mata S, Puigseslloses P, De Macedo M, Lardeux V, Pain S, et al. Unveiling the potential abuse liability of α-D2PV: a novel α-carbon phenyl-substituted synthetic cathinone. Neuropharmacology. 2025;272:110425.

Hur K-H, Kim S-E, Lee B-R, Ko Y-H, Seo J-Y, Kim S-K, et al. 25C-NBF, a new psychoactive substance, has addictive and neurotoxic potential in rodents. Arch Toxicol. 2020;94:2505–16.

Kehr J, Yoshitake T. Monitoring brain chemical signals by microdialysis. Encycl Sens. 2006;6:287–312.

Song P, Mabrouk OS, Hershey ND, Kennedy RT. In vivo neurochemical monitoring using benzoyl chloride derivatization and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2012;84:412–9.

Dunlap LE, Azinfar A, Ly C, Cameron LP, Viswanathan J, Tombari RJ, et al. Identification of Psychoplastogenic N, N-Dimethylaminoisotryptamine (isoDMT) Analogues through Structure-Activity Relationship Studies. J Medicinal Chem. 2020;63:1142–55.

Yang Y, Cui Y, Sang K, Dong Y, Ni Z, Ma S, et al. Ketamine blocks bursting in the lateral habenula to rapidly relieve depression. Nature. 2018;554:317–22.

Duart-Castells L, López-Arnau R, Vizcaíno S, Camarasa J, Pubill D, Escubedo E. 7,8-Dihydroxyflavone blocks the development of behavioral sensitization to MDPV, but not to cocaine: differential role of the BDNF-TrkB pathway. Biochemical Pharmacol. 2019;163:84–93.

Espinosa-Jiménez T, Cano A, Sánchez-López E, Olloquequi J, Folch J, Bulló M, et al. A novel rhein-huprine hybrid ameliorates disease-modifying properties in preclinical mice model of alzheimer’s disease exacerbated with high fat diet. Cell Biosci. 2023;13:52.

Casaril AM, Domingues M, Bampi SR, de Andrade Lourenço D, Padilha NB, Lenardão EJ, et al. The selenium-containing compound 3-((4-chlorophenyl)selanyl)-1-methyl-1H-indole reverses depressive-like behavior induced by acute restraint stress in mice: modulation of oxido-nitrosative stress and inflammatory pathway. Psychopharmacology. 2019;236:2867–80.

Głuch-Lutwin M, Sałaciak K, Pytka K, Gawalska A, Jamrozik M, Śniecikowska J, et al. The 5-HT1A receptor biased agonist, NLX-204, shows rapid-acting antidepressant-like properties and neurochemical changes in two mouse models of depression. Behavioural Brain Res. 2023;438:114207.

Hesselgrave N, Troppoli TA, Wulff AB, Cole AB, Thompson SM. Harnessing psilocybin: antidepressant-like behavioral and synaptic actions of psilocybin are independent of 5-HT2R activation in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2021;118:e2022489118.

Prusoff ChengY-C. WH. Relationship between the inhibition constant (KI) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 per cent inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochemical Pharmacol. 1973;22:3099–108.

Ehlert FJ. On the analysis of ligand-directed signaling at G protein-coupled receptors. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch Pharmacol. 2008;377:549–77.

Rajagopal S, Ahn S, Rominger DH, Gowen-MacDonald W, Lam CM, DeWire SM, et al. Quantifying ligand bias at seven-transmembrane receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2011;80:367–77.

Nehmea R, Carpenter B, Singhal A, Strege A, Edwards PC, White CF, et al. Mini-G proteins: novel tools for studying GPCRs in their active conformation. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0175642.

Halberstadt AL, Chatha M, Klein AK, Wallach J, Brandt SD. Correlation between the potency of hallucinogens in the mouse head-twitch response assay and their behavioral and subjective effects in other species. Neuropharmacology. 2020;167:107933.

Kalfas M, Taylor RH, Tsapekos D, Young AH. Psychedelics for treatment resistant depression: are they game changers? Expert Opin Pharmacotherapy. 2023;24:2117–32.

Heal DJ, Gosden J, Smith SL. Evaluating the abuse potential of psychedelic drugs as part of the safety pharmacology assessment for medical use in humans. Neuropharmacology. 2018;142:89–115.

Celada P, Puig MV, Amargós-Bosch M, Adell A, Artigas F. The therapeutic role of 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors in depression. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2004;29:252–65.

Cameron LP, Patel SD, Vargas MV, Barragan EV, Saeger HN, Warren HT, et al. 5-HT2ARs mediate therapeutic behavioral effects of psychedelic tryptamines. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2023;14:351–8.

Rickli A, Luethi D, Reinisch J, Buchy D, Hoener MC, Liechti ME. Receptor interaction profiles of novel N-2-methoxybenzyl (NBOMe) derivatives of 2,5-dimethoxy-substituted phenethylamines (2C drugs). Neuropharmacology. 2015;99:546–53.

Glennon RA, Titeler M, McKenney JD. Evidence for 5-HT2 involvement in the mechanism of action of hallucinogenic agents. Life Sci. 1984;35:2505–11.

Halberstadt AL, Geyer MA. Effects of the hallucinogen 2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodophenethylamine (2C-I) and superpotent N-benzyl derivatives on the head twitch response. Neuropharmacology. 2014;77:200–7.

Elmore JS, Decker AM, Sulima A, Rice KC, Partilla JS, Blough BE, et al. Comparative neuropharmacology of N-(2-methoxybenzyl)-2,5-dimethoxyphenethylamine (NBOMe) hallucinogens and their 2C counterparts in male rats. Neuropharmacology. 2018;142:240–50.

Reckweg J, Mason NL, van Leeuwen C, Toennes SW, Terwey TH, Ramaekers JG. A Phase 1, dose-ranging study to assess safety and psychoactive effects of a vaporized 5-methoxy-N, N-dimethyltryptamine formulation (GH001) in healthy volunteers. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:760671.

Reckweg JT, van Leeuwen CJ, Henquet C, van Amelsvoort T, Theunissen EL, Mason NL, et al. A phase 1/2 trial to assess safety and efficacy of a vaporized 5-methoxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine formulation (GH001) in patients with treatment-resistant depression. Front Psychiatry. 2023;14:1133414.

Erkizia-Santamaría I, Alles-Pascual R, Horrillo I, Meana JJ, Ortega JE. Serotonin 5-HT2A, 5-HT2c and 5-HT1A receptor involvement in the acute effects of psilocybin in mice. In vitro pharmacological profile and modulation of thermoregulation and head-twich response. Biomedicine Pharmacotherapy. 2022;154:113612.

Shahar O, Botvinnik A, Esh-Zuntz N, Brownstien M, Wolf R, Lotan A, et al. Role of 5-HT2A, 5-HT2C, 5-HT1A and TAAR1 receptors in the head twitch response induced by 5-hydroxytryptophan and psilocybin: translational implications. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:14148.

Kyzar EJ, Nichols CD, Gainetdinov RR, Nichols DE, Kalueff AV. Psychedelic drugs in biomedicine. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2017;38:992–1005.

López-Giménez JF, González-Maeso J. Hallucinogens and serotonin 5-HT2A receptor-mediated signaling pathways. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2018;36:45–73.

Kim K, Che T, Panova O, DiBerto JF, Lyu J, Krumm BE, et al. Structure of a Hallucinogen-Activated Gq-Coupled 5-HT2A Serotonin Receptor. Cell. 2020;182:1574–7.e19.

Wallach J, Cao AB, Calkins MM, Heim AJ, Lanham JK, Bonniwell EM, et al. Identification of 5-HT2A receptor signaling pathways associated with psychedelic potential. Nat Commun. 2023;14:8221.

Ayme-Dietrich E, Lawson R, Côté F, de Tapia C, Da Silva S, Ebel C, et al. The role of 5-HT2B receptors in mitral valvulopathy: bone marrow mobilization of endothelial progenitors. Br J Pharmacology. 2017;174:4123–39.

Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). Psychedelic Drugs: Consid Clin Investigations Guidance Ind DRAFT GUIDANCE. 2023.

Glatfelter GC, Naeem M, Pham DNK, Golen JA, Chadeayne AR, Manke DR, et al. Receptor binding profiles for tryptamine psychedelics and effects of 4-propionoxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine in Mice. ACS Pharmacology Transl Sci. 2022;6:567–77.

Wojtas A, Herian M, Skawski M, Sobocińska M, González-Marín A, Noworyta-Sokołowska K, et al. Neurochemical and behavioral effects of a new hallucinogenic compound 25B-NBOMe in rats. Neurotox Res. 2021;39:305–26.

Gatch MB, Dolan SB, Forster MJ. Locomotor and discriminative stimulus effects of four novel hallucinogens in rodents. Behavioural Pharmacol. 2017;28:375–85.

Tirri M, Bilel S, Arfè R, Corli G, Marchetti B, Bernardi T, et al. Effect of -NBOMe compounds on sensorimotor, motor, and prepulse inhibition responses in mice in comparison with the 2C analogs and lysergic acid diethylamide: from preclinical evidence to forensic implication in driving under the influence of drugs. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:875722.

Rodriguiz RM, Nadkarni V, Means CR, Pogorelov VM, Chiu YT, Roth BL, et al. LSD-stimulated behaviors in mice require β-arrestin 2 but not β-arrestin 1. Sci Rep. 2021;11:17690.

Vollenweider FX, Csomor PA, Knappe B, Geyer MA, Quednow BB. The effects of the preferential 5-HT2A agonist psilocybin on prepulse inhibition of startle in healthy human volunteers depend on interstimulus interval. neuropsychopharmacology: official publication of the american college of neuropsychopharmacology. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:1876–87.

Sitte HH, Freissmuth M. Amphetamines, new psychoactive drugs and the monoamine transporter cycle. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2015;36:41–50.

Jeon SY, Kim Y-H, Kim SJ, Suh SK, Cha HJ. Abuse potential of 2-(4-iodo-2, 5-dimethoxyphenyl)N-(2-methoxybenzyl)ethanamine (25INBOMe); in vivo and ex vivo approaches. Neurochemistry Int. 2019;125:74–81.

Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Wang GJ. Role of dopamine in drug reinforcement and addiction in humans: results from imaging studies. Behavioural Pharmaco. 2002;13:355–66.

Di Chiara G, Bassareo V, Fenu S, De Luca MA, Spina L, Cadoni C, et al. Dopamine and drug addiction: the nucleus accumbens shell connection. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47:227–41.

Wojtas A, Herian M, Maćkowiak M, Solarz A, Wawrzczak-Bargiela A, Bysiek A, et al. Hallucinogenic activity, neurotransmitters release, anxiolytic and neurotoxic effects in Rat’s brain following repeated administration of novel psychoactive compound 25B-NBOMe. Neuropharmacology. 2023;240:109713.

Miliano C, Marti M, Pintori N, Castelli MP, Tirri M, Arfè R, et al. Neurochemical and behavioral profiling in male and female rats of the psychedelic agent 25I-NBOMe. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:1406.

Negus SS, Banks ML. Decoding the structure of abuse potential for new psychoactive substances: structure-activity relationships for abuse-related effects of 4-substituted methcathinone analogs. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2017;32:119–31.

Bubar M, Cunningham K. Serotonin 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptors as potential targets for modulation of psychostimulant use and dependence. Curr Top Medicinal Chem. 2006;6:1971–85.

Campbell EJ, Bonomo Y, Pastor A, Collins L, Norman A, Galettis P, et al. The 5-HT2C receptor as a therapeutic target for alcohol and methamphetamine use disorders: a pilot study in treatment-seeking individuals. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2021;9:e00767.

Calder AE, Hasler G. Towards an understanding of psychedelic-induced neuroplasticity. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2023;48:104–12.

Cameron LP, Tombari RJ, Lu J, Pell AJ, Hurley ZQ, Ehinger Y, et al. A non-hallucinogenic psychedelic analogue with therapeutic potential. Nature. 2021;589:474–9.

Duman RS, Aghajanian GK. Synaptic dysfunction in depression: potential therapeutic targets. Science. 2012;338:68–72.

Liao C, Dua AN, Wojtasiewicz C, Liston C, Kwan AC. Structural neural plasticity evoked by rapid-acting antidepressant interventions. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2024;26:101–14.

Liu M-Y, Yin C-Y, Zhu L-J, Zhu X-H, Xu C, Luo C-X, et al. Sucrose preference test for measurement of stress-induced anhedonia in mice. Nat Protoc. 2018;13:1686–98.

Can A, Dao DT, Terrillion CE, Piantadosi SC, Bhat S, Gould TD. The tail suspension test. J Visualized Experiments. 2012;59:e3769.

Noble RE. Depression in women. Metabolism: Clinical and Experimental. 2005;54:49–52.

Dossat AM, Wright KN, Strong CE, Kabbaj M. Behavioral and biochemical sensitivity to low doses of ketamine: influence of estrous cycle in C57BL/6 mice. Neuropharmacology. 2018;130:30–41.

Gaidica M Rat Brain Atlas. https://labs.gaidi.ca/rat-brain-atlas/. Accessed date 15-01-2025.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/ 501100011033 and by ERDF/EU (PID2022-137541OBI00), Plan Nacional sobre Drogas (2020I051), European Union (EU) Home Affairs Funds, NextGenPS project (number: 101045825) and by the Centre National pour la Recherche Scientifique, the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, the University of Poitiers, the Nouvelle Aquitaine CPER 2015-2020 / FEDER 2014-2020 program “Habisan”. DP, RLA, and EE belong to 2021SGR00090 from Generalitat de Catalunya. PP and CRC received a doctoral scholarship grant from Generalitat de Catalunya (AGAUR), 2022 FISDU 00004 and 2024 FI-1 00088, respectively. LG received the predoctoral scholarship PREDOCS-UB from the Universitat de Barcelona. ME is supported by a Serra Hunter contract (UB-LE-9115). This study has benefited from the facilities and expertise of PREBIOS platform (Université de Poitiers). The work of HHS is supported by grants from the Austrian Science Funds / FWF (P33955 and P35589). EP acknowledges funding from Ghent University’s Bijzonder Onderzoeksfonds (BOF23/PDO/073). We are grateful to Dr. Gemma Navarro and her staff for letting us to use their Nivo plate reader and the advice for using it.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RLA conceptualized and designed the study with the assistance of NNG and EE. NNG, PP, LG, NW, EP, CRC, VL, NT, FW, LK, IPE, GK and JM collected and analyzed the data. NNG, LG, EP, DP, MRA, ME, JK, CS, MS, HHS and RLA developed the methodology. NNG and XB synthetized the compounds. NNG, MRA, JK, CS, MS, HHS, EE and RLA interpreted the data. XB, MRA, ME, JK, CS, MS, HHS and RLA supervised research activities. NNG and RLA wrote the original draft. NNG, PP, EP, XB, DP, MRA, ME, JK, CS, MS, HHS, EE and RLA revised and edited the manuscript. RLA, EE, JK, CS, MS, DP and HHS acquired funding. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nadal-Gratacós, N., Puigseslloses, P., Guzmán, L. et al. The psychedelic phenethylamine 25C-NBF, a selective 5-HT2A agonist, shows psychoplastogenic properties and rapid antidepressant effects in male rodents. Mol Psychiatry (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-025-03341-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-025-03341-1