Abstract

O-GlcNAcylation of ribonucleotide reductase large subunit M1 (RRM1) at position 734 influences high glucose-induced genomic instability and cell transformation in normal pancreatic cells. By disrupting the ribonucleotide reductase complex, it reduces dNTPs. Although the impact of RRM1 O-GlcNAcylation on pancreatic cancer progression remains unexplored, our CRISPR knock-in technology created the RRM1-T734A mutation to minimize RRM1 O-GlcNAcylation. In pancreatic cancer PANC-1 cells with this mutation, we observed heightened replication stress-induced DNA damage, S-phase delays, and diminished in vitro tumor cell growth. Mechanistically, RRM1-T734A enhanced its interaction with RRM2 while impairing binding to RRM2B, leading to decreased NTPs and disrupted dNTP equilibrium. Notably, it doubled dTTP levels via TK1 stabilization mediated by thymidine, resulting in S-phase delay. TK1 silencing restored RRM1-T734A-induced effects on S-phase retardation and decreased colony formation. Our findings highlight the pivotal role of O-GlcNAcylation of RRM1 at T734 in maintaining genomic stability and promoting pancreatic cancer malignancy. Furthermore, reducing RRM1 O-GlcNAcylation increased pancreatic cancer cell sensitivity to gemcitabine, proposing a potential therapeutic strategy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ribonucleotide reductase (RNR) plays a pivotal role in safeguarding genomic stability by controlling cellular dNTP levels for DNA replication and repair [1]. RNR forms tetrameric complexes involving RRM1 and RRM2 (or RRM2B), orchestrating the rate-limiting conversion of ribonucleoside diphosphates (NDPs) into deoxy (d)NDPs in the de novo pathway [2]. Irregularities in RNR activity, marked by elevated levels of RRM2 and RRM2B, along with modified RRM1 and RRM2—including acetylation [3], phosphorylation [4, 5], or O-GlcNAcylation [6],—are linked to genomic instability and are hallmark traits across various cancers. Additionally, diverse RNR inhibitors with distinct mechanisms have proven effective in cancer treatment [7, 8]. Gemcitabine, a pivotal agent in pancreatic cancer therapy, disrupts RNR by binding to RRM1, halting DNA elongation through integration into DNA strands [9]. However, resistance to gemcitabine remains a significant challenge in achieving effective chemotherapy.

Several studies indicate that heightened RRM1 levels correlate with gemcitabine resistance [10,11,12]. Elevated RRM1 expression also impacts the prognosis and overall survival of individuals with pancreatic cancer [13]. The clinical implications of RRM1 expression levels have been clarified [14, 15]. Furthermore, RRM1 protein undergoes modification via O-linked N-Acetylglucosaminylation (O-GlcNAcylation) at position 734 in pancreatic cells exposed to high glucose [6]. This modification influences high glucose-induced genomic instability and cell transformation in normal pancreatic cells by reducing dNTPs through disruption of the ribonucleotide reductase complex [6].

O-GlcNAcylation is a reversible post-translational modification (PTM) characterized by the addition of N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) units from UDP-GlcNAc to serine and threonine residues of proteins [16]. This process relies on O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT), which adds UDP-GlcNAc to target proteins, and O-GlcNAcase (OGA), responsible for removing O-GlcNAc from O-GlcNAcylated proteins [16]. Notably, O-GlcNAcylation expression is higher in tumors than in normal pancreatic tissue [17]. In pancreatic cancer, O-GlcNAcylation governs key tumor-related proteins such as p53, c-Myc, β-catenin, Ras, and NF-κB, promoting oncogene function while suppressing tumor suppressor genes [18]. Despite the known involvement of O-GlcNAcylation of RRM1 at T734 in pancreatic cancer initiation, the precise impact of RRM1-T734 O-GlcNAcylation on pancreatic cancer progression and gemcitabine sensitization remains unclear.

In our study, we employed CRISPR knock-in technology to generate the RRM1-T734A mutation, reducing RRM1 O-GlcNAcylation. This mutation increased DNA damage and replication stress in PANC-1 cells, resulting in S-phase delays and slower in vitro tumor growth. Furthermore, it led to reduced tumor growth and metastasis in vivo. Mechanistically, the RRM1-T734A mutation enhanced RRM1’s interaction with RRM2 while weakening its association with RRM2B, causing an imbalance in nucleotide levels—most notably doubling dTTP due to TK1 stabilization. Importantly, silencing TK1 reversed the phenotypic alterations induced by RRM1-T734A, highlighting the crucial role of RRM1 O-GlcNAcylation at T734 in pancreatic cancer. Additionally, reducing RRM1 O-GlcNAcylation in pancreatic cancer cells increased sensitivity to gemcitabine, suggesting a promising therapeutic strategy.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

The human pancreatic cancer cell lines PANC-1, MiaPaCa-2, and BxPC-3 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA. These cell lines were cultured under standard conditions at 37°C with 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator. PANC-1 and MiaPaCa-2 cells were maintained in high-glucose DMEM, while BxPC-3 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium. All media were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 IU/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 1% L-glutamine, and 1% nonessential amino acids (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The medium for MiaPaCa-2 was additionally supplemented with 2.5% horse serum. The cells were regularly monitored for mycoplasma infection.

Establishment of RRM1-T734A knock-in of PANC-1 cells

To generate an RRM1-T734A knock-in within PANC-1 cells, we designed a comprehensive CRISPR-Cas9 plasmid. This plasmid, developed by the National RNAi Core Facility in Taipei, Taiwan, contains a lentivirus backbone with sgRNA, Cas9, EGFP, and pPuro. The donor template, an oligonucleotide synthesized by Mission Biotech, has the following sequence:

5′-CTTATTTAGAGTGAACTGGATTGGATTAGCTGCTGGTCTCGTCCTTAAATAATA CATCCCAGCCTTAAGACCCTACAAGGAAAGTAAAGACAATTATTAG-3′.

To introduce the all-in-one plasmid and donor template into PANC-1 parental cells, we employed LT1 reagent for transfection, followed by cell sorting based on GFP expression. For single colony selection, we used 96-well dishes containing GFP-positive cells, followed by puromycin selection and serial dilution in each dish. Each resulting colony was isolated for confirmation of knock-in through PCR and sequencing. The PCR primers used were as follows: Forward primer: 5′-CGGCTGGACAGGAATGTATTT-3′ Reverse primer: 5′-CAGCAAAGCCTTACCACCTC-3′.

Plasmids

The lentiviral shRNA expression vectors pLKO.1-shLacZ, shTK1#1 (TRCN0000010135), shTK1#2 (TRCN0000318728) and shOGT (TRCN0000035064) were obtained from the National RNAi Core Facility (Taipei, Taiwan). Additionally, we purchased the C-GFPSpark-tag Human Thymidine Phosphorylase lentiviral cDNA (I-HG10432-ACGLN) and the lentiviral C-GFPSpark tag vector from Sino Biological.

Establishment of stable cell lines

To establish stable cell lines expressing LacZshRNA, TK1shRNA and OGTshRNA, we infected PANC-1 cells with lentivirus carrying the specified shRNA and then subjected them to selection using 1 μg/mL puromycin. For the creation of a stable cell line expressing the C-GFPSpark-tag vector, or TP, PANC-1 cells were infected and subsequently sorted based on GFP expression using flow cytometry.

Immunoprecipitation of RRM1 and O-GlcNAcylation detection

For RRM1 immunoprecipitation, we lysed cells using IP lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP40, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM Na2VO3, 1 mM DTT, 0.1% SDS, and 2 mM PMSF. We also included phosphatase inhibitors and protease inhibitors. Protein concentrations were determined using the Bradford assay (Bio-rad, Cat# 5000006) and normalized to 1 mg/mL. Subsequently, 500 μg of protein lysate was incubated with either 1 μg of anti-RRM1 antibody (Santa Cruz, Cat# sc-11733) or 1 μg of anti-goat-IgG antibody (Santa Cruz, Cat# sc-2028) at 4 °C overnight. Afterward, we incubated the lysates with protein G beads (Genetex) at 4 °C for 1 h. Following three washes with IP lysis buffer, we eluted the proteins using Laemmli sample buffer for subsequent Western blot analysis. O-GlcNAcylation detection was performed using the O-linked N-Acetylglucosamine (RL2) antibody (Abcam, Cat# ab2739) and the anti-O-GlcNAc (CTD110.6) antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Cat# 9875).

Immunofluorescence staining

To conduct foci staining of γH2AX, 53BP1, and RPA, we seeded 5000 cells per well in 96-well dishes overnight. The cells were then fixed and permeabilized using 100% methanol for 15 min at −20 °C. After fixation, they underwent three 5 min washes with 0.1% Triton X-100 in TBS buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl) on a shaker at room temperature. The cells were blocked with MAXblockTM (Active Motif, Cat# 15252) for 1 h at 37°C and then stained overnight at 4°C with anti-γH2AX (1:1000, Merck Millipore, Cat# 05-636), anti-53BP1 (1:1,000, Merck Millipore Cat# MAB3802), or anti-RPA (1:500, Abcam, Cat# ab109084) antibodies. Following three additional 5 min washes with 0.1% TBST buffer, cells were stained with Alexa Fluor 488 (1:100) or Texas Red (1:200) conjugated secondary antibodies and DAPI (10 mg/ml, 1:1000, Life Technologies) for 1 h at room temperature. Finally, the cells were washed and immersed in PBS for foci analysis using the MD Image Xpress Micro XLS.

Cell proliferation assay

To assess cell proliferation, we seeded 5000 cells per well in a 96-well dish containing 100 μl of growth medium, supplemented with an additional 20 μl of growth medium daily. Cell proliferation was monitored over five consecutive days using the Cell Proliferation Kit II (XTT) (Roche, Cat# 11465015001) following the manufacturer’s guidelines. Results were measured using a Thermo Scientific™ Multiskan™ GO Microplate Spectrophotometer, recording absorbance at OD492 and OD690 nm.

Cell death analysis

The viability of PANC-1 cells was assessed using the LIVE/DEAD™ Cell Imaging Kit (488/570) (Invitrogen, Cat# R37601). A 2X stock solution containing live green and dead red reagents was prepared and mixed with PBS. This mixture was incubated with the cells at room temperature for 15 min, along with Hoechst 33342 to stain the cell nuclei. Fluorescence imaging was conducted to classify cells as viable (green fluorescence) or non-viable (red fluorescence).

Cell cycle synchronization and analysis

To synchronize the cell cycle, cells were exposed to 100 ng/mL of nocodazole (Sigma-Aldrich) for 16 h, followed by two PBS washes. Cells were then plated in culture media for 6, 12, 18, and 24 h. Approximately 1 million cells were fixed with 70% cold ethanol and stored at −20 °C overnight. The fixed cells were centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 5 min, and the supernatant was removed. After washing with cold PBS, a PI staining buffer (0.04 mg/mL Propidium Iodide, 2 mg RNase A, and 0.1% Triton X-100) was applied and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. Stained cells were analyzed using a flow cytometer.

Soft agar colony formation assay

For the soft agar colony formation assay, 500 cells were seeded in a 0.35% agar layer over a 0.5% agar layer in 12-well dishes. The cells were cultured in a humidified 37 °C incubator for 9 days. Colony-forming efficiency was assessed using light microscopy, counting colonies with diameters exceeding 50 μm.

Sphere formation assay

The sphere formation assay involved seeding 5000 cells per well in a low-attachment 6-well dish, incubating for 6 days. Spheroids larger than 100 μm in diameter were counted and analyzed using light microscopy.

Western blot analysis

Cells were lysed using RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM PMSF, 50 mM NaF, 1% Nonidet P-40) supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail and a phosphatase inhibitor cocktail. Equal amounts of protein lysates were separated via SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. Membranes were blocked with 5% milk in TBST (0.1% Triton X-100) at room temperature for 1 h, then incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. After incubation with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h, signals were visualized using Immobilon Forte Western HRP Substrate (Merck Millipore, Cat# WBLUF0500) and captured using the UVP BioSpectrum 500 Imaging System. Gel-Pro software was used to quantify the intensity of each band in the immunoblotting.

Animal protocol

All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Utilization Committee of Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan (IACUC#20-03-1451 and IACUC#23-11-2084). Mice were housed in a specific pathogen-free facility at 20 °C ± 2 °C with a 12/12 h light/dark cycle and were given unrestricted access to water and standard laboratory chow.

Tumor growth in mice

To create GFP-Luc PANC-1 cells, PANC-1 cells were infected with a GFP-Luciferase lentivirus and subsequently sorted for GFP expression via flow cytometry. NOD/SCID/IL2Rγnull (NSG) mice, obtained from Jackson Laboratory, were bred in-house at the Academia Sinica animal core facility. Eight-week-old male NSG mice of similar body weights were selected for the experiments. In the subcutaneous tumorigenicity assay, 10 million PANC-1 cells were mixed with 50 μl of Matrigel and injected subcutaneously into the right flanks of NSG mice. Tumor size and body weight were monitored weekly. Seven weeks post-implantation, mice were euthanized, and their tissues were collected. Tumor volume was calculated using the formula: tumor volume = 1/2 × width2 × length. For the orthotopic tumorigenicity assay, 5 × 106 cells in 30 μl of Matrigel were injected into the pancreas of NSG mice. Two months after orthotopic implantation, mice were euthanized, and tumor size and weight were measured. The metastases of PANC-1 cells to liver and lung metastases was assessed using the IVIS kinetics imaging system (Caliper LifeSciences).

NTP and dNTP quantification

Total 1 × 107 cells were suspended in 1 ml of 80% cold methanol ( − 20 °C), then sonicated and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube and dried using a SpeedVac (LaboGene). The pellets were reconstituted in 1 ml of ddH2O, mixed with 3.75 ml of cold chloroform/methanol (1:1), and agitated using an ELMI Intelli-mixer ERM-2 for 10 to 15 min at 4 °C. Next, 1.25 ml of cold chloroform (4 °C) was added, vortexed for 1 min, followed by 1.25 ml of ice-cold ddH2O, and further vortexedfor 1 min. The sample was stored at −80 °C for 25 min, then centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The upper hydrophilic layer was collected into a new tube and dried using a SpeedVac for LC-ESI-MS detection.

Nucleoside metabolite analysis

Total 5 × 106 cells were harvested and washed with chilled PBS. The pellets were reconstituted in a solution of methanol: acetonitrile: ddH2O (2:2:1) and sonicated three times for 30 s each. After centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C, the supernatant was collected and dried using a SpeedVec (LaboGene). The dried samples were reconstituted in 50% methanol ( − 20 °C) for LC-ESI-MS detection.

LC-ESI-MS for metabolomics detection

To amplify signals of carboxylic acid and organic phosphate, 5 µl of aniline/HCl reaction buffer (0.3 M aniline [Sigma-Aldrich, USA] in 60 mM HCl) and 5 µl of 20 mg/ml N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC; Sigma-Aldrich, USA) were added to each hemocyte residue sample. After vortexing, the mixtures were incubated at 25 °C for 2 h. The reaction was halted by adding 5 µl of 10% ammonium hydroxide. The aniline-derivatized samples were analyzed using an LC-ESI-MS system consisting of an ultra-performance liquid chromatography system (Ultimate3000 RSLC, Dionex) and a quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer with an electrospray ionization (ESI) source (maXis UHR-QToF system, Bruker Daltonics). Metabolites were separated via reversed-phase liquid chromatography on a BEH C18 column (2.1 × 100 mm, Waters). The LC settings were autosampler temperature at 4 °C, injection volume of 10 µl, and flow rate at 0.4 mL/min. The elution began with 1% mobile phase B (0.1% formic acid in ACN) for 4 min, followed by a gradient from 99% mobile phase A (0.1% formic acid in ddH2O) and 1% mobile phase B. After being held at 1% for 0.5 min and increased to 60% over 5 min, mobile phase B was further elevated to 90% in an additional 0.5 min, maintained at 90% for 1.5 min, and then reduced back to 1% in 0.5 min. Subsequently, the column was re-equilibrated by pumping 99% B for 4 min. The LC-ESI-MS chromatograms were acquired under these conditions: dry gas temperature at 190 °C, dry gas flow rate at 8 L/min, nebulizer gas at 1.4 bar, and capillary voltage at 3500 V. Mass spectra in the negative ion mode were recorded across the range of m/z 100–1000. Data acquisition was done using HyStar and microTOF control software (Bruker Daltonics), and analyzed with DataAnalysis and TargetAnalysis software (Bruker Daltonics). Each metabolite was identified by matching its theoretical m/z value and isotope pattern derived from its chemical formula. Quantification was performed by summing the corresponding area of the extracted ion chromatogram.

RNA extraction and qPCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted from the cells using the TRIzol method (Life Technologies, 15596018) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The isolated mRNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using the Maxima First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit from Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. Gene expression levels were quantified by real-time PCR with the SYBR FAST qPCR Kit (KAPA Biosystems, Wilmington, MA, USA) on a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). GAPDH was used as the internal control for normalizing mRNA expression. Fold changes were calculated using the 2-ΔΔCt method after normalization with the internal control. The sequences of the QPCR primers for specific genes were as follows:

TK1 forward primer: 5’-CCTTCCTGCCACTGCCGCCTACTG-3’, TK1 reverse primer: 5’-TCCACGCCTCCCGACTTCCTCCTG-3’; TP forward primer: 5’-CTGGAGTTATTCCTGGATTCA-3’; TP reverse primer: 5’-TCTGCTCTGGGCTCTGGATGA-3’; GAPDH forward primer: 5’-GCTGCAGGGCCTCACTCCTTTT-3’; GAPDH reverse primer: 5’-AGAGCCAGTCTCTGGCCCC-3’.

TK1 stabilization analysis

PANC-1 cells were seeded in a 6-well dish and allowed to adhere overnight. These cells were treated with 50 μg/ml cycloheximide (CHX, Sigma, Cat# C1988) for 0, 2, 4, and 8 h, then collected using RIPA buffer for Western blot analysis.

Cell cytotoxicity assay

A total 5 × 103 cells were plated per well in 96-well dishes and exposed to varying concentrations of gemcitabine (0–100 μM) for 3 days. Cell viability was assessed using the Cell Proliferation Kit II (XTT) (Product No. 11465015001) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The IC50 value was calculated using GraphPad Prism 9 software.

Statistical analysis

The data were presented as means ± SD, as detailed in the figure legends. A two-tailed Student’s t-test was used to compare differences between the control and experimental groups. * denotes statistical significance with p < 0.05, ** indicates p < 0.01, *** represents p < 0.001 and **** represents p < 0.0001. The specific n numbers used in the respective sections were described in the figure legends.

Results

Reduction of RRM1 O-GlcNAcylation exacerbates genomic instability in human PDAC PANC-1 cells

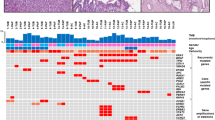

To explore the potential role of RRM1 O-GlcNAcylation in pancreatic cancer malignancy, we conducted immunoprecipitation (IP) assays on various pancreatic cancer cell lines and the non-tumorigenic pancreatic cell line HPDE. Our findings revealed significantly elevated levels of protein O-GlcNAcylation, specifically on RRM1, in pancreatic cancer cells compared to non-tumorigenic cells (Supplementary Fig. S1). This suggests a potential association between RRM1 O-GlcNAcylation and pancreatic cancer development. In our previous research, we identified that O-glycosylation at the T734 site of the RRM1 protein plays a crucial role in inducing genomic instability and cell transformation in non-tumorigenic pancreatic cells under high-glucose conditions [6]. Remarkably, this specific T734 site in RRM1 is highly conserved across different species (Supplementary Fig. S2), underscoring its functional importance. To inhibit O-GlcNAcylation, a common strategy involves mutating threonine to alanine. Furthermore, observations indicate that approximately 41% of pancreatic cancer cells harbor the KRASG12D mutation, while 32% and 16% possess KRASG12V and KRASG12R mutations, respectively [19]. Leveraging CRISPR knock-in technology, we generated RRM1-T734A mutant PANC-1 cells (which carry the common single KRASG12D mutation) [20] to reduce RRM1 O-GlcNAcylation. Two successfully mutated clones were confirmed by sequencing (Fig. 1A) and exhibited significantly diminished RRM1 O-GlcNAcylation levels compared to parental cells (Fig. 1B).

A Threonine at position 734 of the RRM1 amino acid sequence was substituted with alanine in PANC-1 cells using CRISPR/Cas9. Two clones were validated via sequencing and used for further experiments. A silent mutation in leucine was introduced to confirm the success of the CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in. B The O-GlcNAcylation status was assessed in parental PANC-1 cells and the two RRM1-T734A PANC-1 clones. The left and right panels display O-GlcNAcylation levels in total cell lysates and immunoprecipitated RRM1, respectively. Protein O-GlcNAcylation was detected using anti-RL2 and anti-CTD 110.6 antibodies. Relative expression levels were normalized for the P84 internal control and parental cells. C–E Representative (left panels) and quantitative (right panels) green immunofluorescence images showing γH2AX (C), 53BP1 (D), and RPA (E) foci, respectively. PANC-1 cells with more than ten foci in the nucleus were classified as positive. DAPI was used to stain the nuclei (blue signal). Data are presented as the mean ± SD. Each dot represents an independent experiment. n = 8 for (C) and (D), and n = 7 for (E). **** p < 0.0001 (two-tailed Student’s t-test). Scale bar, 50 μm.

In our previous study, we demonstrated that high glucose-induced O-GlcNAcylation of RRM1 triggers genomic instability in non-tumorigenic pancreatic cells [6]. Consistent with these findings, we observed elevated levels of O-GlcNAcylated RRM1 (Supplementary Fig. S1) and increased genomic instability (Supplementary Fig. S3) in human PDAC PANC-1 cells compared to non-tumorigenic HPDE cells. To further investigate the functional role of reduced O-GlcNAcylation in PANC-1 cells, we examined genomic instability in parental PANC-1 cells and RRM1-T734A mutant cells with impaired O-GlcNAcylation. Immunofluorescence staining revealed that PANC-1 cells harboring RRM1-T734A exhibited significantly more foci of γH2AX (a marker for DNA double-strand breaks and genomic instability), 53BP1 (indicating DNA double-strand breaks and replication stress), and RPA (associated with single-strand breaks and replication stress) compared to parental PANC-1 cells (Fig. 1C–E). Additionally, Western blot analysis confirmed elevated levels of phosphorylated RPA (Ser33), a marker of replication stress, in PANC-1 RRM1-T734A cells (Supplementary Fig. S4). Surprisingly, these results suggest that reduced O-GlcNAcylation of RRM1 at the T734 site may exacerbate genomic instability in human PDAC PANC-1 cells.

The RRM1-T734A mutation in PANC-1 cells suppresses tumor malignancy through S-phase arrest, limiting proliferation, growth, and metastasis

High levels of DNA damage can trigger either uncontrolled cell growth (malignant proliferation) or growth inhibition. To investigate the impact of the RRM1-T734A mutation on PANC-1 cell proliferation, we employed the XTT assay. Notably, PANC-1 cells carrying the RRM1-T734A mutation exhibited a significant decrease in proliferation rate compared to parental cells (Fig. 2A). To determine whether the slower growth resulted from cell cycle arrest or increased cell death, we synchronized cells at the G2/M phase using nocodazole. Subsequent analysis involved assessing cell cycle progression via flow cytometry and cell viability using LIVE/DEAD™ staining (Fig. 2B–D). Our findings revealed that RRM1-T734A in PANC-1 cells led to delayed cell growth primarily due to S-phase retardation (Fig. 2B), without inducing substantial cell death (Fig. 2D). Furthermore, sphere and colony formation assays demonstrated that RRM1-T734A mutant PANC-1 cells had a reduced ability to form spheres and colonies compared to parental cells (Fig. 2E, F). Collectively, these results suggest that the decreased O-GlcNAcylation of RRM1 caused by the T734A mutation suppresses the malignant behavior of pancreatic cancer cells in vitro by inducing S-phase retardation.

A Each well of a 96-well plate was initially seeded with 5000 cells in 100 μl of growth medium, with an additional 20 μl of growth medium added daily. The relative cell growth of PANC-1 cells was measured using the Cell Proliferation Kit II (XTT) over five consecutive days. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. n = 5, **** p < 0.0001 (two-tailed Student’s t-test). B, C PANC-1 cells were synchronized at the G2/M phase by treating them with 100 ng/mL of Nocodazole for 16 h. After washing with PBS, cells were harvested at the indicated time points for flow cytometry analysis using Propidium Iodide (PI) staining to assess the cell cycle. The figures show representative (B) and quantitative (C) cell cycle profiles of both asynchronized and nocodazole-released PANC-1 cells. n = 3, **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001 (two-tailed Student’s t-test). D The death rate of PANC-1 cells was assessed using a live/dead staining kit. Dead cells were indicated by red fluorescence using BOBO-3 iodide, while Hoechst 33342 stained the cell nuclei in blue. Representative images and the percentage of dead cells are shown in the left and right panels, respectively. Each dot represents an independent experiment (n = 3). E, F PANC-1 cell sphere formation (E) and colony formation assays (F) were conducted and quantified. Representative images are shown in the left panels. The right panels show quantitative data on sphere numbers and colony numbers, considering diameters larger than 100 μm and 50 μm, respectively. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. Each dot represents an independent experiment. n = 6 for (E) and n = 8 for (F), **** p < 0.0001 (two-tailed Student’s t-test).

To further validate the role of RRM1 O-GlcNAcylation in vivo, we conducted subcutaneous (Fig. 3A–C) and orthotopic (Fig. 3D, E) injections of GFP-luciferase-labeled parental and RRM1-T734A mutant PANC-1 cells into NSG mice. Remarkably, while body weight remained unchanged between the groups (Fig. 3A), tumors derived from RRM1-T734A mutant cells exhibited significantly smaller size and reduced weight in both subcutaneous (Fig. 3B, C) and orthotopic models (Fig. 3D). Additionally, IVIS imaging revealed a marked decrease in bioluminescence intensity in the livers of mice injected with RRM1-T734 A cells compared to parental cells (Fig. 3E), suggesting suppressed liver metastasis. Collectively, these findings underscore the role of reduced RRM1 O-GlcNAcylation by the T734A mutation in suppressing pancreatic tumor growth and metastasis in vivo.

A–C Subcutaneous injection and (D, E) orthotopic injection of GFP-Luc PANC-1 cells were performed on eight-week-old male NOD/SCIDγ mice. A Body weight and (B) tumor volume of mice injected subcutaneously with PANC-1 cells were measured continuously for 7 weeks. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. ****p < 0.0001 (two-tailed Student’s t-test). C Seven weeks after subcutaneous implantation, mice were euthanized, and tumors were dissected and weighed. Tumor images are shown in the left panel, and tumor weight is displayed in the right panel. Each dot represents one mouse. parental and T734A#1, n = 6; T734A#2, n = 5. Data are presented as mean ± SD. **** p < 0.0001 (two-tailed Student’s t-test). D Two months after orthotopic implantation, mice were euthanized, and tumors were dissected and measured for volume and weight. Tumor images are shown in the left panel, and tumor volume and weight are displayed in the right panel. Each dot represents one mouse. Data are presented as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ****p < 0.0001 (two-tailed Student’s t-test). E IVIS images of GFP-Luc PANC-1 cells in the liver were obtained from mice following two months of orthotopic PANC-1 cell implantation (left panel). Bioluminescence intensity was quantified and is presented in the right panel. Each dot represents one mouse. Data are presented as mean ± SD. n = 4 in the parental and RRM1-T734A #1 groups; n = 5 for the RRM1-T734A #2 group. *p < 0.05 (two-tailed Student’s t-test).

RRM1-T734A mutation affects RNR interactions, leading to imbalanced nucleotide pools and dTTP elevation in pancreatic cancer

RRM1 plays a crucial role as a subunit of ribonucleotide reductase (RNR), an enzyme responsible for maintaining balanced deoxyribonucleotide (dNTP) pools essential for DNA synthesis and repair [21]. RRM1 interacts with Tip60, a histone acetylase, facilitating recruitment to DNA damage sites for dNTP supply during repair [22]. Our previous research demonstrated that O-GlcNAcylation of RRM1 modulates its binding affinity to RRM2 and RRM2B, the other RNR subunits [6]. We hypothesized that the T734A mutation in RRM1 might alter its binding to these subunits and Tip60, impacting RNR function and leading to imbalanced nucleotide pools and DNA damage. Immunoprecipitation analyses revealed that RRM1-T734A mutant PANC-1 cells exhibited increased binding affinity to RRM2 compared to parental cells but decreased binding to RRM2B. Interestingly, Tip60 binding remained unaffected (Fig. 4A). While the precise link between altered RNR binding and slow tumor growth requires further investigation, the increased RRM1-RRM2 interaction in RRM1-T734A mutants may significantly impact nucleotide pool production through altered RNR activity.

A Lysates from specified PANC-1 cells underwent RRM1 immunoprecipitation, followed by Western blot analysis. The left panel shows representative blots probed with antibodies against RRM2, RRM2B, and Tip-60. The right panel illustrates the relative protein binding affinity of RRM1 compared to parental PANC-1 cells. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Each dot represents an independent experiment (n = 3). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 (two-tailed Student’s t-test). B, C NTP (B) and dNTP (C) pool levels were assessed by LC/MS analysis and normalized against those in parental PANC-1 cells. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Each dot represents an independent experiment (n = 3). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 (two-tailed Student’s t-test). D Diagram illustrating the relative abundance of metabolites involved in DNA synthesis between RRM1-T734A and parental PANC-1 cells, as detected by LC/MS. Red and blue colors denote significantly up- and down-regulated metabolites, respectively (p < 0.05). E Western blot analysis of thymidine-related key enzymes. The left panel displays representative images, while the right panel shows TP and TK1 protein levels relative to parental PANC-1 cells. Each dot represents an independent experiment (n = 3). *p < 0.05 and ****p < 0.0001 (two-tailed Student’s t-test). F PANC-1 cells were treated with cycloheximide (CHX) at the indicated time points and subjected to Western blot analysis. The left panel shows representative images, while the right panel indicates relative TK1 protein levels at various time points post-CHX treatment compared to untreated conditions. All data are represented as mean ± SD (n = 3). *p < 0.05 (two-tailed Student’s t-test).

LC/MS analysis of cellular nucleotide pools revealed a striking decrease in all NTPs (ATP, UTP, CTP, and GTP) in RRM1-T734A cells compared to parental cells (Fig. 4B). Additionally, the mutant cells exhibited a significant dNTP pool imbalance, characterized by elevated dTTP levels and reduced dATP, dCTP, and dGTP levels (Fig. 4C). Notably, dTTP levels were more than twofold higher in RRM1-T734A cells. Given that dTTP serves as a crucial allosteric effector of RNR, its elevation can contribute to genomic instability and disruptions in the cell cycle [23]. To investigate the source of elevated dTTP, we analyzed dTTP synthesis-related metabolites using LC/MS. Interestingly, both thymidine and dTMP (precursors of dTTP) were significantly increased in RRM1-T734A cells compared to parental cells (Fig. 4D). Western blot analysis further supported these findings, revealing significantly lower expression of thymidine phosphorylase (TP), the enzyme converting thymine to thymidine, and conversely, higher expression of thymidine kinase 1 (TK1), the enzyme converting thymidine to dTMP, in RRM1-T734A cells (Fig. 4E). Notably, protein levels of thymidylate synthase and thymidylate kinase (TMPK), other key dTTP synthesis enzymes, remained unchanged (Fig. 4E and Supplementary Fig. S5). qPCR analysis indicated that only TP mRNA levels were significantly decreased in RRM1-T734A mutant cells (Supplementary Fig. S6), suggesting transcriptional downregulation of TP expression. Interestingly, a previous study reported that thymidine, the substrate for TK1, can regulate its protein stability [24]. Consistent with these findings, we observed high thymidine and TK1 protein levels in RRM1-T734A cells. To assess whether the elevated TK1 protein levels resulted from increased stability, we treated cells with cycloheximide, a protein synthesis inhibitor, and monitored TK1 protein decay over time. Kinetic analysis of TK1 protein levels revealed a significantly longer half-life in RRM1-T734A cells compared to parental cells, confirming enhanced TK1 protein stability (Fig. 4F).

These findings collectively demonstrate that the RRM1-T734A mutation disrupts RNR subunit interactions, resulting in imbalanced nucleotide pools and elevated dTTP levels. The mechanism underlying this imbalance includes the downregulation of TP expression and the increased stability of TK1, the enzyme responsible for dTTP synthesis. These results underscore the significance of RRM1 O-GlcNAcylation in regulating nucleotide metabolism and suggest its potential role in the progression of pancreatic cancer.

O-GlcNAcylation of RRM1 alters cell cycle and PDAC malignancy via Thymidine kinase 1 stability

Previous studies suggest that elevated dTTP levels can lead to S-phase arrest [24]. To understand how TP downregulation and TK1 upregulation contribute to S-phase retardation in RRM1-T734A PANC-1 cells, we manipulated their expression levels. We stably increased TP expression in RRM1-T734A cells using a lentiviral vector. However, this overexpression did not reverse the S-phase arrest phenotype (Supplementary Fig. S7). This suggests that TP downregulation might not be the primary driver of S-phase retardation in these cells. In contrast, knocking down TK1 expression with lentiviral shRNA significantly alleviated S-phase arrest in RRM1-T734A PANC-1 cells (Fig. 5A–C). Additionally, these TK1 knockdown cells displayed increased colony formation compared to control cells (Fig. 5D). This suggests that TK1 upregulation in RRM1-T734A PANC-1 cells plays a more prominent role in promoting S-phase arrest and suppressing cancer cell growth.

A Western blot analysis of thymidine-related key enzymes in LacZ and TK1-knocked-down PANC-1 cells. B, C PANC-1 cells stably expressing LacZshRNA or TK1shRNA were synchronized at the G2/M phase using nocodazole treatment. After release from nocodazole at 0, 18, and 24 h, these cells were harvested for cell cycle analysis. B Representative of cell cycle profiles, (C) Quantitative data for both asynchronized and nocodazole-released PANC-1 cells (n = 3), **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001 (two-tailed Student’s t-test). D The left panel presents representative images of soft agar colony formation in PANC-1 cells stably expressing LacZshRNA or TK1shRNA. The right panel shows the quantified number of colonies larger than 50 μm. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Each dot represents an independent experiment. n = 12/group. ****p < 0.0001 (two-tailed Student’s t-test).

These findings indicate that the reduced O-GlcNAcylation of RRM1 primarily contributes to S-phase retardation and tumor suppression in PANC-1 cells by enhancing TK1 stability and promoting dTTP synthesis. TP downregulation appears to have a less significant role in this process.

Targeting RRM1 O-GlcNAcylation enhances Gemcitabine efficacy

Pancreatic cancer remains a highly aggressive malignancy with limited therapeutic options. Gemcitabine, a standard chemotherapy treatment for pancreatic cancer, often faces limitations due to dose-related toxicities and the development of resistance in many patients [25]. RRM1, a known gemcitabine target, exhibits expression levels linked to drug sensitivity [10,11,12]. Based on our RRM1-T734A findings (Figs. 2 and 3), we explored targeting RRM1 O-GlcNAcylation to enhance Gemcitabine sensitivity.

Our data reveal that RRM1-T734A cells exhibit reduced viability and higher sensitivity to gemcitabine compared to parental PANC-1 cells (Fig. 6A, B). As RRM1-T734A enhances TK1 stability and dTTP synthesis, leading to S phase retardation and growth inhibition (Figs. 4 and 5), we investigated TK1’s role in the increased gemcitabine sensitivity. Knocking down TK1 in RRM1-T734A cells and assessing gemcitabine’s effect on viability revealed that TK1 knockdown restores gemcitabine sensitivity in the RRM1-T734A cells (Supplementary Fig. S8), confirming TK1’s crucial role. Given that OGT regulates RRM1 O-GlcNAcylation in vitro [6] and in vivo (Supplementary Fig. S9), and that OSMI-1 is a selective OGT inhibitor [26], we explored whether OSMI-1 could mimic the RRM1-T734A mutation’s gemcitabine-sensitizing effects. We found that OSMI-1 increases gemcitabine sensitivity, primarily by regulating RRM1 O-GlcNAcylation (Supplementary Fig. S10). To further explore the therapeutic potential of modulating RRM1 O-GlcNAcylation for gemcitabine sensitization, we used OSMI-1 to analyze its effects in various pancreatic cancer cell lines. Remarkably, OSMI-1 treatment alone suppressed cell viability in parental cells, and the combination of OSMI-1 with gemcitabine had a significantly greater cytotoxic effect than gemcitabine alone (Fig. 6C, D). These suggest that reducing RRM1 O-GlcNAcylation via the T734A mutation and OSMI-1 treatment enhances gemcitabine sensitivity. Furthermore, we confirmed the synergistic effect of gemcitabine and OSMI-1 in other pancreatic cancer cell lines, including MiaPaCa-2 and BxPC-3 cells (Fig. 6E–H).

A, B Parental and RRM1-T734A PANC-1 cells were treated with indicated concentrations of gemcitabine for three days and subjected to viability analysis. A Cell viability in the absence of gemcitabine treatment was normalized to parental cell numbers (n = 5). ****p < 0.0001 (two-tailed Student’s t-test). B Cell viability following gemcitabine treatment in parental and RRM1-T734A PANC-1 cells was normalized to their respective untreated conditions. C–H Parental PANC-1 (C, D), MiaPaCa-2 (E, F), and BxPC-3 (G, H) cells were exposed to OSMI1 alone or in combination with gemcitabine, then evaluated for viability. C, E, G) show cell viability without gemcitabine treatment, normalized to their corresponding OSMI1-untreated conditions. PANC-1 cells (n = 4); MiaPaCa-2 and BxPC-3 cells (n = 8). **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001 (two-tailed Student’s t-test). D, F, H Cells were pre-exposed to OSMI1 for a day and then subjected to combined treatment with indicated concentrations of gemcitabine for three days to assess cell viability. B, D, F, H All IC50 were determined by GraphPad Prism 9. Analysis model: asymmetric sigmoidal, 5PL, X is log (concentration). I Proposed model illustrating how O-GlcNAcylation of RRM1 impacts pancreatic cancer malignancy.

Discussion

In this study, we explored the role of RRM1 O-GlcNAcylation, specifically through the RRM1- T734A mutation, in pancreatic cancer malignancy and its potential as a therapeutic target (Fig. 6I). Our initial observations revealed high levels of O-GlcNAcylation on RRM1 in pancreatic cancer cell lines (Supplementary Fig. S1). Using CRISPR-Cas9 knock-in technology, we confirmed that T734 on RRM1 is a crucial site for this modification, vital for maintaining genomic stability in pancreatic cancer PANC-1 cells (Fig. 1). The RRM1-T734A mutation in PANC-1 cells significantly suppressed tumor malignancy in both cell culture and animal models (Figs. 2, 3). Mechanistically, this mutation exerts its tumor-suppressive effects by disrupting nucleotide pools, notably increasing dTTP levels through the stabilization of TK1 (Figs. 4, 5). This imbalance in nucleotide pools likely hinders cancer cell proliferation by elevating replication stress and causing S-phase retardation. Additionally, PANC-1 cells with the RRM1-T734A mutation exhibited reduced viability and increased sensitivity to gemcitabine, a first-line chemotherapy for pancreatic cancer. The generalizability of the effects of RRM1 O-GlcNAcylation at T734 is further supported by our findings in HEK293T cells with RRM1-T734A KI mutation (Supplementary Fig. S11). Furthermore, our findings extend beyond genetic manipulation. Treatment with OSMI-1, a selective OGT inhibitor [26], also reduced cell viability in various pancreatic cancer cell lines. Notably, OSMI-1 synergized with gemcitabine, leading to enhanced cell death (Fig. 6). In conclusion, our data strongly suggest that targeting RRM1 O-GlcNAcylation, either by disrupting the modification site through mutation or by inhibiting the O-GlcNAc transferase enzyme with drugs like OSMI-1, represents a promising therapeutic strategy for pancreatic cancer. This approach has the potential to improve treatment efficacy, especially when combined with established therapies like gemcitabine.

O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation are known to regulate protein function through a complex interplay, often competing for the same modification sites [16]. Our data suggest a O-GlcNAcylation at T734 may affect phosphorylation of RRM1 (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Fig. S12). Specifically, the RRM1-T734A mutation, which disrupts O-GlcNAcylation, resulted in decreased serine/threonine phosphorylation levels compared to wild-type RRM1. This finding indicates that O-GlcNAcylation at T734 might inhibit phosphorylation at other sites, although further investigation is needed to elucidate this specific interplay. Previous studies have shown that phosphorylation of RRM1 at specific sites (S559 and S631) can impact DNA replication, dNTP pools, and gemcitabine sensitivity in various cancer types [5, 27]. The RRM1-T734A mutation in pancreatic cancer cells mirrors some effects of the S559A mutation observed in lung cancer (e.g., genomic instability and S-phase retardation). However, there are key differences: the RRM1-T734A mutation leads to elevated dTTP levels, whereas the S559A mutation reduces all four dNTP pools [5]. Additionally, the RRM1-T734A mutation enhances binding to RRM2, contrasting with the decreased binding observed with the RRM1-S631A mutation [27]. These findings suggest that the disruption of O-GlcNAcylation at T734 might influence RRM1 function through a mechanism distinct from known phosphorylation pathways. Future studies are warranted to dissect the precise interplay between O-GlcNAcylation at T734 and specific phosphorylation events on RRM1. Our study highlights a complex and context-dependent role for RRM1 O-GlcNAcylation in pancreatic carcinogenesis. In non-tumorigenic pancreatic cells, high-glucose levels induce RRM1 O-GlcNAcylation, disrupting the ribonucleotide reductase (RNR) complex, leading to genomic instability and cellular transformation. Conversely, the RRM1-T734A mutation, which reduces O-GlcNAcylation, mitigates these adverse effects by enhancing RRM1 binding to both RRM2 and RRM2B subunits [6]. Interestingly, pancreatic cancer cells exhibit elevated RRM1 O-GlcNAcylation and DNA damage compared to non-tumorigenic cells (Supplementary Figs. S1, S3). Paradoxically, further reduction of RRM1 O-GlcNAcylation via the T734A mutation in cancer cells enhances DNA damage and induces S-phase arrest, ultimately suppressing tumor malignancy (Figs. 1–3). This suggests that O-GlcNAcylation of RRM1 is a critical factor in pancreatic cancer cells, modulating genomic instability within a range that facilitates tumor progression. Mechanistically, the RRM1-T734A mutation has distinct effects on nucleotide pools compared to non-tumorigenic cells, specifically affecting RRM1’s interaction with RRM2, but not RRM2B. This mutation uniquely elevates dTTP levels while decreasing other dNTPs and NTPs, contributing to S-phase retardation and hindering tumor growth (Fig. 4). The increase in dTTP is likely due to thymidine-mediated TK1 stabilization, while the reduction in other dNTPs (dATP, dCTP, and dGTP). This imbalanced dTTP pool likely contributes to S-phase retardation and hinders tumor growth. However, the precise mechanism underlying the downregulation of other NTPs remains unclear. Elevated dTTP, likely resulting from TP downregulation and subsequent thymidine-mediated TK1 stabilization, contributes to S-phase retardation and tumor growth suppression in RRM1-T734A cells. However, TP overexpression does not affect TK1 expression or S-phase retardation (Supplementary Fig. S7), suggesting alternative mechanisms are involved. Additionally, high dTTP levels, despite being a known RNR allosteric effector, paradoxically decrease dCTP formation [2, 28]. The mechanisms behind the low levels of dATP and dGTP in RRM1-T734A cells are still unclear. Given the potential impact of O-GlcNAcylation on protein-protein interactions, further investigation is warranted to identify the interacting partners of RRM1-T734A compared to parental cells. Understanding these interactions will shed light on the complex regulatory roles of RRM1-T734A in nucleotide metabolism and their implications for pancreatic cancer progression. PDAC is a highly aggressive cancer heavily dependent on chemotherapy due to its anatomical and pathological characteristics. However, chemoresistance remains a significant challenge in PDAC treatment. Gemcitabine (dFdC), a first-line chemotherapeutic agent, targets RRM1 to inhibit RNR activity and DNA synthesis [29]. Elevated RRM1 levels have been linked to gemcitabine resistance and a poor prognosis in pancreatic cancer patients [10,11,12,13]. Our study reveals a novel role for RRM1 O-GlcNAcylation at the T734 site in maintaining pancreatic cancer malignancy. We demonstrate that inhibiting RRM1 O-GlcNAcylation, either by introducing the T734A mutation or using the O-GlcNAc transferase inhibitor OSMI-1, significantly enhances gemcitabine sensitivity in pancreatic cancer cells (Fig. 6). These findings underscore the potential of RRM1 O-GlcNAcylation as a therapeutic target for overcoming gemcitabine resistance. Interestingly, while OSMI-1 treatment shows growth-inhibitory effects and increases gemcitabine sensitization, its impact is less pronounced than that of the RRM1-T734A mutation. This suggests that selectively targeting RRM1 O-GlcNAcylation could be a more effective therapeutic strategy. Further investigation is required to elucidate the precise regulatory mechanisms of RRM1 O-GlcNAcylation and develop specific inhibitors for clinical application. Moreover, additional studies should explore the effects of targeting RRM1 O-GlcNAcylation in gemcitabine-resistant pancreatic cancer cells. Understanding the interplay between RRM1 O-GlcNAcylation and gemcitabine resistance could lead to novel therapeutic approaches, potentially.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Nordlund P, Reichard P. Ribonucleotide reductases. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:681–706.

Reichard P. Interactions between deoxyribonucleotide and DNA synthesis. Annu Rev Biochem. 1988;57:349–74.

Chen G, Luo Y, Warncke K, Sun Y, Yu DS, Fu H, et al. Acetylation regulates ribonucleotide reductase activity and cancer cell growth. Nat Commun. 2019;10:3213.

D’Angiolella V, Donato V, Forrester FM, Jeong YT, Pellacani C, Kudo Y, et al. Cyclin F-mediated degradation of ribonucleotide reductase M2 controls genome integrity and DNA repair. Cell. 2012;149:1023–34.

Shu Z, Li Z, Huang H, Chen Y, Fan J, Yu L, et al. Cell-cycle-dependent phosphorylation of RRM1 ensures efficient DNA replication and regulates cancer vulnerability to ATR inhibition. Oncogene. 2020;39:5721–33.

Hu CM, Tien SC, Hsieh PK, Jeng YM, Chang MC, Chang YT, et al. High Glucose Triggers Nucleotide Imbalance through O-GlcNAcylation of Key Enzymes and Induces KRAS Mutation in Pancreatic Cells. Cell Metab. 2019;29:1334–1349.e1310.

Aye Y, Li M, Long MJ, Weiss RS. Ribonucleotide reductase and cancer: biological mechanisms and targeted therapies. Oncogene. 2015;34:2011–21.

Huff SE, Winter JM, Dealwis CG. Inhibitors of the Cancer Target Ribonucleotide Reductase, Past and Present. Biomolecules 2022; 12.

Cerqueira NM, Fernandes PA, Ramos MJ. Understanding ribonucleotide reductase inactivation by gemcitabine. Chemistry. 2007;13:8507–15.

Chen P, Wu JN, Shu Y, Jiang HG, Zhao XH, Qian H, et al. Gemcitabine resistance mediated by ribonucleotide reductase M2 in lung squamous cell carcinoma is reversed by GW8510 through autophagy induction. Clin Sci (Lond). 2018;132:1417–33.

Minami K, Shinsato Y, Yamamoto M, Takahashi H, Zhang S, Nishizawa Y, et al. Ribonucleotide reductase is an effective target to overcome gemcitabine resistance in gemcitabine-resistant pancreatic cancer cells with dual resistant factors. J Pharm Sci. 2015;127:319–25.

Kato T, Ono H, Fujii M, Akahoshi K, Ogura T, Ogawa K, et al. Cytoplasmic RRM1 activation as an acute response to gemcitabine treatment is involved in drug resistance of pancreatic cancer cells. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0252917.

Lin X, Tan Y, Pan L, Tian Z, Lin L, Su M, et al. Prognostic value of RRM1 and its effect on chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2024;93:237–51.

Aoyama T, Miyagi Y, Murakawa M, Yamaoku K, Atsumi Y, Shiozawa M, et al. Clinical implications of ribonucleotide reductase subunit M1 in patients with pancreatic cancer who undergo curative resection followed by adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine. Oncol Lett. 2017;13:3423–30.

Chatzidavid S, Kontandreopoulou CN, Diamantopoulos PT, Giannakopoulou N, Katsiampoura P, Stafylidis C, et al. The Clinical and Prognostic Significance of Ribonucleotide Reductase Subunits RRM1 and RRM2 mRNA Levels in Patients with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Clin Hematol Int. 2023;5:92–100.

Yang X, Qian K. Protein O-GlcNAcylation: emerging mechanisms and functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2017;18:452–65.

Ma Z, Vocadlo DJ, Vosseller K. Hyper-O-GlcNAcylation is anti-apoptotic and maintains constitutive NF-kappaB activity in pancreatic cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:15121–30.

de Queiroz RM, Carvalho E, Dias WB. O-GlcNAcylation: The Sweet Side of the Cancer. Front Oncol. 2014;4:132.

Biankin AV, Waddell N, Kassahn KS, Gingras MC, Muthuswamy LB, Johns AL, et al. Pancreatic cancer genomes reveal aberrations in axon guidance pathway genes. Nature. 2012;491:399–405.

Deer EL, Gonzalez-Hernandez J, Coursen JD, Shea JE, Ngatia J, Scaife CL, et al. Phenotype and genotype of pancreatic cancer cell lines. Pancreas. 2010;39:425–35.

Yen Y. Ribonucleotide reductase subunit one as gene therapy target: commentary re: M-Y. Cao et al., Adenovirus-mediated ribonucleotide reductase R1 gene therapy of human colon adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:4304–8.

Niida H, Shimada M, Murakami H, Nakanishi M. Mechanisms of dNTP supply that play an essential role in maintaining genome integrity in eukaryotic cells. Cancer Sci. 2010;101:2505–9.

Ke PY, Kuo YY, Hu CM, Chang ZF. Control of dTTP pool size by anaphase promoting complex/cyclosome is essential for the maintenance of genetic stability. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1920–33.

Ke PY, Hu CM, Chang YC, Chang ZF. Hiding human thymidine kinase 1 from APC/C-mediated destruction by thymidine binding. FASEB J. 2007;21:1276–84.

Burris HA 3rd, Moore MJ, Andersen J, Green MR, Rothenberg ML. Improvements in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine as first-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer: a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2403–13.

Ortiz-Meoz RF, Jiang J, Lazarus MB, Orman M, Janetzko J, Fan C, et al. A small molecule that inhibits OGT activity in cells. ACS Chem Biol. 2015;10:1392–7.

Tian L, Chen C, Guo Y, Zhang F, Mi J, Feng Q, et al. mTORC2 regulates ribonucleotide reductase to promote DNA replication and gemcitabine resistance in non-small cell lung cancer. Neoplasia. 2021;23:643–52.

Thelander L, Reichard P. Reduction of ribonucleotides. Annu Rev Biochem. 1979;48:133–58.

Ueno H, Kiyosawa K, Kaniwa N. Pharmacogenomics of gemcitabine: can genetic studies lead to tailor-made therapy?. Br J Cancer. 2007;97:145–51.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the technical support provided by the confocal imaging core facilities at the Biomedical Translation Research Center, Taiwan. We also thank the Metabolomics Core Facility at the Agricultural Biotechnology Research Center, Academia Sinica, Taiwan for their assistance with metabolite analysis. We acknowledge the AS Animal Core Facility at Academia Sinica in Taiwan for providing essential animal support, and the National RNAi Core Facility at Academia Sinica in Taiwan for supplying shRNA plasmids.

Funding

This research work was supported by the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC) of Taiwan (NSTC110-2311-B001-016-MY3 and NSTC 113-2634-F-039-001). Open access funding provided by Academia Sinica.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CMH conceived the project and designed experiments. SCT, SM, and CMH performed experiments and interpreted the data. SCT, SM, and CMH wrote the manuscript. CMH edited the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Utilization Committee of Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan (IACUC#20-03-1451 and IACUC#23-11-2084). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tien, SC., Shih, M. & Hu, CM. RRM1 O-GlcNAcylation inhibition suppresses pancreatic cancer via TK1-mediated replication stress. Cancer Gene Ther 32, 550–562 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41417-025-00895-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41417-025-00895-8