Abstract

Hydrogel nanofibers provide a regeneration-permissive environment conducive to the regrowth of numerous nerve fibers, thereby enhancing regenerative capacity in cases of peripheral nerve injury and spinal cord injury. However, developing hydrogel nanofiber-based nerve guidance conduits (NGCs) with tailored drug release profiles to synergistically promote angiogenesis and axonal regeneration remains a significant challenge. In this study, novel polydopamine (PDA)-modified gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA) hydrogel nanofibers are developed as an efficient drug delivery platform for sustained release of Secreted Frizzled-Related Protein-2 (SFRP2). This platform aims to promote neurite outgrowth, facilitate nerve function recovery, and enhance angiogenesis through Wnt signaling pathways. Results indicate that PDA coating significantly improves the hydrophilicity and mechanical properties of GelMA hydrogel nanofibers, which were fabricated using a combination of electrospinning and photo-crosslinking technology. This modification enables SFRP2 loading for sustained release through π-π stacking interactions and hydrogen bonding. In vitro experiments demonstrate that SFRP2-loaded hydrogel nanofibers effectively enhance the adhesion, proliferation, viability, and migration of Mouse Schwann Cells (MSCs), while also promoting tube formation and ameliorating the inflammatory microenvironment of Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs). Furthermore, the SFRP2-loaded hydrogel nanofibers are confirmed to exert their functions for angiogenesis and peripheral nerve regeneration via the calcium-dependent calcineurin/NFATc3 signaling pathway. Finally, the hydrogel nanofiber-based NGCs are applied in a mouse model of peripheral nerve injury, and results demonstrate that the SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA conduit significantly enhances angiogenesis, promotes peripheral nerve repair, and facilitates target muscle restoration and functional recovery, thus presents a promising therapeutic strategy for patients with peripheral nerve injuries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Peripheral nerve injury is a prevalent cause of long-term disability, affecting individuals globally and resulting in a range of debilitating symptoms, including severe pain and significant muscle function impairment1. In clinical practice, autologous nerve repair remains the gold standard for the treatment of peripheral nerve injuries2,3. However, this approach is associated with several drawbacks, including secondary neuroma formation, limited donor availability, and mismatched nerve diameters4. Artificial nerve guidance conduits (NGCs) offer an effective alternative by providing a supportive mechanical structure and microenvironment for damaged nerves, inhibiting scar tissue formation, and ultimately promoting nerve repair5,6,7,8. For example, hydrogels and nanofibers, renowned for their good biocompatibility and solute permeability, have been widely developed for the fabrication of various NGSs9. These materials not only enhance cell-extracellular matrix interactions, cellular proliferation, and migration10,11, but also enable the integration of bioactive molecule delivery and the encapsulation of stem cells, thereby accelerating nerve repair and regeneration11. To combine the advantages of hydrogels (e.g., high viscoelasticity and rapid environmental responsiveness) with the benefits of nanofibers (e.g., high specific surface area and enhanced nutrient/oxygen permeability), hydrogel nanofibers have recently been explored to promote cell recruitment, angiogenesis, and harness the body’s regenerative capacity for nerve repair12,13.

In addition to axonal regeneration, ensuring adequate delivery of oxygen and nutrients is crucial for the survival and proper functioning of nerve cells, particularly in the aftermath of peripheral nerve injuries, which primarily depend on angiogenesis14. Previous studies have primarily focused on enhancing neuronal functionality, either directly or indirectly, to augment the repair processes of injured nerves6,15,16,17,18. This enhancement often involves facilitating the migration of nerve cells and inducing angiogenesis. Considering that angiogenesis and axonal regeneration are typically regulated by common signaling pathways, such as the Wingless-related integration site (Wnt) pathway19,20, the strategic selection of bioactive molecules capable of modulating the Wnt pathway can concurrently improve neuronal functionality and promote local neovascularization. This represents an innovative therapeutic approach for treating peripheral nerve injuries. Secreted Frizzled-related protein-2 (SFRP2), a soluble secreted protein, functions primarily through Wnt signaling, including both the canonical Wnt pathway (i.e., Wnt/β-catenin) and noncanonical Wnt pathway (i.e., Wnt/PCP and Wnt/Ca2+)21,22. Accumulated studies have confirmed that SFRP2 promotes neurite outgrowth and facilitates the recovery of nerve function by suppressing the canonical Wnt pathway21,23,24, while also enhancing angiogenesis through activation of the noncanonical Wnt pathway in endothelial cells21,25,26. Therefore, the combination of hydrogel nanofibers with SFRP2 presents a promising treatment strategy for peripheral nerve regeneration.

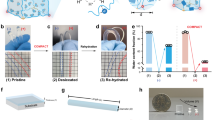

Methacrylated gelatin (GelMA) represents a quintessential collagen-like hydrogel formulation27, and recent studies on GelMA-based hydrogels have centered on integrating various molecules to enhance their physicochemical and biological properties for improved nerve regeneration13,28,29. Polydopamine (PDA), a melanoid polymer derived from dopamine, boasts high phenolic compound content and ROS (Reactive Oxygen Species)-scavenging properties, making it an effective strategy to mitigate ROS-mediated damage and inflammation30. PDA also exhibits exceptional drug loading capacity through π-π stacking interactions and hydrogen bonding, positioning it as a promising candidate for drug delivery systems and the fabrication of nerve conduits31. Consequently, modifying PDA with GelMA hydrogel nanofibers enables the construction of a drug delivery system for SFRP2 loading, with the capacity to simultaneously promote angiogenesis and axonal regeneration for nerve repair (Fig. 1). To confirm this, GelMA hydrogel nanofibers were fabricated using a combination of electrospinning and photo-crosslinking techniques, followed by PDA modification (termed PDA@GelMA) for subsequent SFRP2 loading (SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA). After comprehensive characterization of the physicochemical properties, the in vitro biofunctions (such as Schwann cell migration and endothelial cell tube formation) and in vivo therapeutic efficacy (including motor function recovery, nerve regeneration, angiogenesis, remyelination, and target muscle restoration) of SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA were further validated. Overall, this study presents an alternative nerve conduit for the treatment of peripheral nerve injuries.

A GelMA hydrogel nanofilm was fabricated based on electrospinning technology. B GelMA nanofilm was coated with PDA. C PDA@GelMA nanofilm was modified with SFRP2 protein to obtain the SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA nanofilm. D The SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA nanofilm was curled into a nerve conduit. E The SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA conduit was used to enhance the repair of PNI through promoting angiogenesis and activation of Schwann cells.

Results and discussions

Fabrication of PDA@GelMA hydrogel nanofibers

Gelatin, a hydrolysis product of collagen, has been widely utilized in nerve regeneration applications32. Its excellent cytocompatibility and strong cellular affinity stem from collagen, which incorporates arginine–glycine–aspartic acid (RGD) and matrix metalloproteinase sequences, facilitating cellular adhesion and remodeling33. In order to create a photosensitive hydrogel, methacrylate is incorporated to react with the amine-containing side groups of gelatin without compromising its functional assemblies. This enables gelatin-methacrylate (GelMA) molecules to undergo solidification under UV light through chemical crosslinking of the methacryloyls34,35. This convenient crosslinking procedure confers several advantages to gelatin-based hydrogels. Firstly, it brings in high water content, which facilitates the supply of nutrients and removal of metabolites in the substrate36. Additionally, the crosslinking process extends the molecular chain within the hydrogel nanofibers, imparting the higher degree of softness to the scaffold. This improved softness promotes cellular metabolism and differentiation, even in the absence of protection from the bony spinal canal33. Moreover, the biomimetic nanofibrous microstructure, resembling the extracellular matrix (ECM) of nerves, provides favorable conditions for cellular adhesion and directional growth. In this context, GelMA hydrogel nanofibers were fabricated using electrospinning followed by the exposure of UV light (Fig. 2A). The immobilization of biologically functional molecules onto GelMA hydrogel nanofibers is further achieved through surface coating strategies utilizing mussel-inspired adhesive PDA. This approach has gained considerable attention due to its versatility and adaptability for post-modification of amino-containing molecules, as well as its exceptional bio-affinity for cell adhesion and growth37. Hence, in this study we employed a facile and effective one-pot coating method to modify the hydrogel nanofibers with a PDA coating layer, enabling subsequent grafting of biomolecules.

A Schematic illustration of the fabricated process of PDA@GelMA. B SEM images. Scale bar: 5 μm. C FTIR spectra. D Surface wettability. E XPS spectra. F The deconvolution of C1s and N1s peaks of GelMA. G The deconvolution of C1s and N1s peaks of PDA@GelMA. H Rheological properties of samples against frequency at 25 °C.

The microscopic morphology of GelMA hydrogel nanofibers was analyzed using SEM. As depicted in Fig. 2B, the PDA@GelMA samples showed randomly aligned and uniform nanofibers, demonstrating the insolubility of the crosslinked sample in aqueous solutions, even after the subsequent PDA modification. This observation confirms the successful crosslinking of GelMA molecules for hydrogel formation. Additionally, compared to the smooth surface of GelMA, the PDA@GelMA exhibited a rough surface attributed to the accumulation of PDA nanoaggregates with non-covalent crosslinking, such as π-π stacking and hydrogen bonds, as illustrated in Figure A38. The FTIR spectra (Fig. 2C) exhibited characteristic peaks at 3278 cm−1 and 1260 cm−1, attributed to the N−H stretching in the amine vibration and the C–N stretching in the aromatic amine vibration, respectively. The increased intensity of the broad N−H peak and the appearance of the small C–N peak provide further confirmation of the successful PDA coating modification. Notably, the PDA modification significantly enhanced the surface wettability of the hydrogel nanofibers, attributable to the increased presence of hydrophilic groups, including -NH2 and phenolic hydroxyl groups (Fig. 2D). XPS analysis of the surface chemistry also confirmed the presence of the PDA coating on the hydrogel nanofibers (Fig. 2E). High-resolution C 1 s and N 1 s scans (Fig. 2F, G) revealed that the C 1 s core-level spectrum could be fitted with three peaks at 284.8 eV (C−C), 285.8 eV (C−N), and 289.0 eV (C=O), while the N 1 s core-level spectrum was fitted with three peaks at 398.4 eV (−N=), 399.7 eV (−NH−), and 401.9 eV (−NH2)37. Comparing the C1s core-level spectrum of PDA@GelMA with pristine GelMA (Fig. 2F), a significant increase in the composition of C–N groups and a decrease in the composition of C=O groups were observed. This indicates the occurrence of Schiff-base reactions during PDA polymerization37. Similarly, the N 1 s core-level spectrum of PDA@GelMA (Fig. 2G) showed an increased content of –N= groups coupled with a sharp decrease in the percentage of -NH- groups, indicating a higher prevalence of Schiff-base reactions over Michael addition reactions during PDA polymerization. The mechanical properties of hydrogel nanofibers, characterized by their stiffness and flexibility, have a substantial impact on cell phenotype, cell adhesion, and cellular functions39. As such, the viscoelastic behavior of GelMA and PDA@GelMA was analyzed using a rheometer. As depicted in Figure H, both G′ and G″ values of the hydrogel nanofibers increased progressively after PDA coating, indicating enhanced stability and stiffness. This can be attributed to the heightened cross-linked network density on the surface of the fibers.

SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA possess the sustainable release of SFRP2 to improve nerve-associated cell growth

Living systems rely on intricate and precise regulatory mechanisms to modulate the controlled release or modification of biologically active substances, ensuring normal metabolic homeostasis40. However, many human tissues exhibit limited self-regulatory and self-repair capabilities, necessitating the utilization of biologically active substances or drugs to facilitate tissue regeneration41,42. In this context, electrospun fibers have emerged as promising drug carriers due to their high porosity and large specific surface area43, which enhance drug-loading efficiency and enable rapid stimulus-responsive release. Moreover, their biomimetic ECM-like morphology inherently facilitates cellular uptake of drugs37. In this study, the PDA coating layer is a supramolecular structure formed through hydrogen bonding and π-π interactions between dopamine monomers, with trimers and tetramers being the predominant forms. Despite its complex surface chemistry, the PDA layer exhibits inherent chemical reactivity on its surface owing to the presence of catechol quinone moieties and catechol radical species that allow it to interact with nucleophiles such as amine and thiol groups in proteins44,45. This fundamental property enables the utilization of GelMA hydrogel nanofibers coated with a PDA-coating layer as an effective carrier for protein loading.

Previous studies have reported that SFRP2 plays a crucial role in promoting angiogenesis21,25,26 and nerve regeneration23,24. In the current study, we confirmed a significant reduction in both mRNA and protein expression levels of SFRP2 following sciatic nerve injury (Fig. S1). These research findings robustly endorse the supplementation of SFRP2 as a potential therapeutic intervention for the repair of peripheral nerve injuries. Therefore, we aimed to develop an innovative conduit for nerve repair by combining SFRP2 protein with PDA@GelMA hydrogel nanofilm.

In this study, recombinant SFRP2 protein was physically adsorbed onto sterilized PDA@GelMA and GelMA nanofilms. The concentration of SFRP2 protein in the supernatants was measured at 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th week using ELISA to evaluate the protein release capability of these two materials. (Fig. 3A). Both PDA@GelMA and GelMA exhibited continuous release of SFRP2; apparently, the release performance of PDA@GelMA showed greater stability. Therefore, we selected PDA@GelMA to construct a stable release system for SFRP2 to achieve better bioavailability in vivo.

A Sustained release properties of SFRP2 in different hydrogels. B The viability of HUVECs on different nanofilms. C The viability of MSCs on different hydrogel nanofilms. D The viability of HUVECs on SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA nanofilm with 1000 ng/ml SFRP2. E The viability of MSCs on SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA nanofilm with 1000 ng/ml SFRP2. F The cell death ratios of HUVECs and MSCs after treating with different hydrogel nanofilms. G Live/dead cell staining of HUVECs and MSCs on different hydrogel nanofilms. Red cells represent dead cells, and green cells represent live cells. Scale bar: 200 μm. H Representative images of the attached cells on different hydrogel membranes. Nuclei are shown in blue and cytoskeleton staining in orange. Scale bar: 150 μm. I Representative images of intracellular ROS in HUVEC attached to different hydrogel membranes. ROS-up indicates positive control. Scale bar: 500 μm. J Quantification of intracellular ROS levels in HUVEC under different treatments. K Representative images of intracellular ROS in MSC attached to different hydrogel membranes. ROS-up indicates positive control. Scale bar: 500 μm. L Quantification of intracellular ROS levels in MSC under different treatments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ns not significant.

Moreover, bioactive molecules need to exert their biological functions at a certain concentration,, and different cells receive extracellular signals with different strengths46. To determine the optimal concentration of SFRP2 to promote the growth of the two types of cells (Schwann cells and endothelial cells), we incubated these cells in SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA nanomembrane-impregnated solutions with different SFRP2 concentrations (0, 500, 1000, 1500, 2000, 2500 ng/ml). CCK-8 assays revealed that both cell types exhibited optimal cellular activity at an environmental SFRP2 concentration of 1000 ng/ml (Fig. 3D, E and Fig. S2). Consequently, we employed SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA nanomembranes, which can stably release SFRP2 at a concentration of 1000 ng/ml, to fabricate artificial nerve conduits.

Furthermore, the biocompatibility of the aforementioned materials was evaluated in order to establish a robust foundation for their in vivo application. Initially, the impact of diverse material combinations on the survival of two cell types was assessed. The results of the CCK-8 assay indicated that GelMA and PDA@GelMA nanofilms did not exhibit any notable cytotoxic effects on these cells (Fig. 3B, C). We subsequently conducted a direct comparison of the toxic effects of SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA and PDA@GelMA on both cells. Fig. 3G displays AM/PI staining images of Schwann cells and HUVECs after co-culturing with SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA or PDA@GelMA for 48 h, and no significant difference in cell death ratios was observed (Fig. 3F). Secondly, the impact of distinct material combinations on the attachment and morphology of both cells was assessed. Fig. 3H illustrates phalloidin staining images of Schwann cells and endothelial cells co-cultured for a period of 48 h. Both Schwann cells and HUVECs exhibited excellent biocompatibility with the SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA nanofilm, as evidenced by their ability to adhere to the nanofilm while maintaining normal cellular morphology. Based on the co-culture system of cells and hydrogel nanofilm, we detected the intracellular ROS levels. Compared with the control group (GelMA alone) and the positive control group (ROS-up, GelMA with H2O2), both PDA@GelMA and SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA significantly reduced the intracellular ROS levels in both cell types (Fig. 3I–L).

The in vitro results demonstrated that the SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA nanofilm is biocompatible and facilitates attachment of the two cell types. Consequently, nerve conduits prepared with it can achieve conformal contact with damaged nerves without causing significant cell death or limiting angiogenesis. Meanwhile, it possesses effective antioxidant properties, which can alleviate ROS-related cellular damage and support proper cellular function.

SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA exhibits the capacity to recruit host cells for nerve regeneration

In the context of peripheral nerve repair, Schwann cells play a pivotal role in the restoration of damaged myelin sheaths. They provide a physical scaffold for axon repair through cell migration and proliferation, facilitating the regeneration of damaged nerves. Concurrently, endothelial cells form new microvessels through cell proliferation and migration, ensuring the delivery of essential nutrients to surrounding cells47. It can be reasonably deduced that the enhancement of the migration and proliferation of the two cell types represents a pivotal mechanism of action for artificial nerve conduits in the promotion of peripheral nerve repair. In order to evaluate the promotional effects of different material combinations on the horizontal and vertical migration of the two cell types, the scratch healing model and the Transwell non-contact co-culture model, respectively, were employed. In order to eliminate the influence of cell proliferation, Schwann cells and HUVECs were serum-starved prior to the experiments.

The results of the 48-h scratch assay demonstrated that PDA@GelMA promoted the horizontal migration of both cells (Fig. 4A, E), and the addition of SFRP2 effectively enhanced the pro-migratory effect of PDA@GelMA (Fig. 4B, F). Similarly, The Transwell assay revealed that the SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA nanofilms effectively promoted the vertical migration of both cells (Fig. 4C, G), with a significantly stronger effect than that of PDA@GelMA (Fig. 4D, H).

A Representative images of scratch experiment of HUVECs after treating with different hydrogel extracts for 0 h, 24 h, and 48 h. Scale bar: 500 μm. B Quantification of the healing area at 24 h and 48 h of HUVECs. C Representative images of Transwell assay for HUVECs after treating with different hydrogel extracts for 24 h. Scale bar: 300 μm. D Quantification of cell migration per field in Transwell assay of HUVECs. E Representative images of scratch experiments of MSCs after treating with different hydrogel extracts for 0 h, 24 h, and 48 h. Scale bar: 500 μm. F Quantification of the healing area at 24 h and 48 h of MSCs. G Representative images of Transwell assay for MSCs after treating with different hydrogel extracts for 24 h. Scale bar: 300 μm. H Quantification of cell migration per field in Transwell assay of MSCs. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ns not significant.

The SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA construct was observed to facilitate the migration of two distinct cell types in both horizontal and vertical directions. These observations indicate that the nerve conduit fabricated using SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA can simultaneously stimulate the migration and proliferation of Schwann cells and endothelial cells in damaged nerves in multiple directions while maintaining optimal conformality, thereby establishing a robust cellular foundation for nerve repair. Therefore, a robust cellular foundation for nerve repair has been established.

SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA enhances tube formation of endothelial cells through the calcium-dependent calcineurin/NFATc3 signaling axis and modulates inflammatory microenvironment

Following damage of the peripheral nerves, local endothelial cells proliferate and migrate, forming newborn microvessels and improving local blood perfusion. This supports the proliferation and migration of subsequent nerve cells, thereby maximizing the mobilization of the nerve repair process48. Consequently, a considerable number of studies have concentrated on the promotion of blood vessel formation as a strategy for facilitating the repair of damaged nerves19,49,50. Prior research has demonstrated that SFRP2, which was employed in the present study, has the capacity to promote blood vessel formation by endothelial cells in tumors21, inhibit hypoxia-induced endothelial cell apoptosis in the heart51, and mobilize bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells in chronic wound healing52, thereby promoting wound vascularization.

SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA was employed as a source of SFRP2 and its extract was co-cultured with endothelial cells. The effect of 1000 ng/ml SFRP2 on endothelial cells was then evaluated, thereby confirming the hypothesis that SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA promote local angiogenesis. After the effect of cell proliferation was excluded, the results of the tube formation assay demonstrated that the number and density of intercellular junctions and the number of blood vessels per unit area of endothelial cells co-cultured with the SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA extract were significantly increased (Fig. 5A–D). Furthermore, the tube-forming ability of endothelial cells was significantly enhanced. This confirmed that SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA could promote the angiogenesis ability of endothelial cells following stable release of SFRP2 in vitro. This provides a foundation for its potential application in promoting angiogenesis of damaged nerve segments following preparation of nerve conduits.

A Representative images of tube formation of HUVECs after treating with different hydrogel nanofilms for 4 h. Scale bar: 500 μm. B Quantitative analysis of the number of cell connections in the tube formation assay. C Quantitative analysis of the number of blood vessels per field in the tube formation assay. D Quantitative analysis of the density of cell connections in the tube formation assay. E Volcano plot of differential gene expression in RNA-seq of HUVECs after culturing on SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA nanofilm. Red dots indicate significantly up-regulated genes, and green dots indicate significantly down-regulated genes of HUVECs. F Heatmap of z-scored average expression for top differential gene in RNA-seq of HUVECs after culturing on SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA nanofilm. G Quantitative analysis of RNA expression of NFATC3, CTNNB1, PPP3CA, VEGFA, VEGFB, ANGPT1 in HUVECs after culturing on SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA nanofilm. H Western blot of protein expression of calcineurin, nfatc3 and β-catenin in HUVECs after culturing on SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA nanofilm. I Western blot of protein expression of Ang-1, VEGF in HUVECs after culturing on SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA nanofilm. J–M ELISA analysis of IL-6, TNF-α, IL-10, IL-4 secretion of HUVECs after culturing on SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA nanofilm. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ns not significant.

To clarify the cellular and molecular mechanisms of SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA in promoting endothelial cell angiogenesis, we examined the SFRP2-related intracellular signaling pathways. Bulk RNA-seq and differential gene expression analysis of SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA-treated endothelial cells were performed. The volcano plot (Fig. 5E) showed that the NFATC3 gene was markedly up-regulated in endothelial cells. Additionally, the heatmap (Fig. 5F) summarizing the top differentially expressed genes drew the same conclusion. Subsequent KEGG enrichment analysis demonstrated that calcium-related signaling pathways with cytoskeleton and energy metabolism-related pathways were markedly activated in endothelial cells (Fig. S3B), which imply that SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA-treated endothelial cells received SFRP2 molecular signals, and that intracellular calcium ions, functioning as the activated primary messenger, were involved in cytoskeleton reorganization, thereby exhibiting active cell migration and cellular tube formation. Prior research has demonstrated that the primary activation pathway of SFRP2 is the Wnt-related pathways25. The co-activation of NFATC3 and calcium signaling indicates that the noncanonical Wnt/Ca2+ signaling pathway may also be activated. Consequently, we conducted a transcriptional and translational analysis of NFATC3 mRNA (encoding NFATc3) and PPP3CA mRNA (encoding calcineurin), while CTNNB1 mRNA (encoding β-catenin). The results demonstrated that non-canonical Wnt/Ca²⁺ signaling pathways in endothelial cells are also activated. The results demonstrate that the non-canonical Wnt/Ca2+ signal pathway is indeed activated in endothelial cells, while the canonical Wnt pathway is either not activated or not inhibited. In conclusion, the stable release of SFRP2 molecules by SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA will significantly promote cell migration and cellular tube formation in endothelial cells by activating the non-canonical Wnt/Ca²⁺ signaling pathway, but not by inhibiting the canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, which is consistent with the findings of previous studies21,25,26,53. Additionally, we investigated whether SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA induced expression of VEGF or Ang-1. Differential gene expression analysis (Fig. 5F, G) and Western blotting experiments (Fig. 5I) revealed no upregulation of VEGF or Ang-1 at both transcriptional and translational level. Therefore, the role of SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA in promoting angiogenesis is not mediated through the classical angiogenic signals VEGF or Ang-1.

In addition to the formation of new blood vessels, endothelial cells undergo self-destruction to a certain degree following peripheral nerve injury. This process induces a localized inflammatory response, recruits inflammatory cells and produces neurotrophic factors that promote axonal growth54. However, excessive endothelial-derived inflammation can trigger persistent immune infiltration, leading to fibrotic scar formation after nerve conduit implantation and hindering axonal extension55. In order to evaluate the effect of SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA on the production of inflammatory molecules by endothelial cells, an in vitro study was conducted. The results demonstrated that the capacity of endothelial cells to produce TNF-α, IL-6, as markedly diminished in the SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA co-culture system. Interestingly, the levels of anti-inflammatory factors IL-10 and IL-4 were also significantly reduced. This might reflect the dynamic regulation of SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA on the inflammatory balance: it inhibits the over-activated bidirectional inflammatory/anti-inflammatory signals in the early stage and prevents the formation of chronic inflammatory microenvironment (Fig. 5J–M).

SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA demonstrated proliferation-promoting and migration-promoting effects for both cell types. Further analysis of its effects on endothelial cells revealed that it could promote microvessel formation by activating the non-canonical Wnt signaling pathway and inhibiting endothelial cell-derived inflammation. This suggests that SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA may facilitate the formation of beneficial microvessels in peripheral nerves and mitigate endothelium-associated excessive inflammatory responses in peripheral nerve repair, which could be advantageous for early peripheral nerve repair.

SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA conduit effectively promotes angiogenesis and peripheral nerve regeneration

By tightly wrapping the hydrogel nanofibrous membrane around the outer membrane of the damaged nerve segment to fabricate a neural conduit, the unilateral mouse sciatic nerve crush model was established to investigate the effects of different nerve conduits on peripheral nerve repair. PDA@GelMA nanofilm and SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA nanofilm were fabricated into 5 mm long nerve conduits, which were then carefully wrapped around the crushed sciatic nerve (Fig. 6A). All mice underwent successful surgery without any noticeable surgical complications. No detachment or sepsis occurred after the operation. Histological examination using H&E staining further confirmed that there were no unusual pathological changes in any of the experimental groups (Fig. 6B).

A Schematic diagram of the surgical methods in different treatment groups. The yellow rectangle represents the surgical segment of the mouse sciatic nerve, the narrow part represents the sciatic nerve subjected to clamp injury, and the translucent rectangles represents the different nerve conduits. B H&E staining of sciatic nerves in different treatment groups. Black indicates the hydrogel nerve conduit. Scale bar: 300 μm. C Representative images of CD31 staining in different groups. Scale bar: 150 μm. D Quantitative analysis of microvessel density (CD31 staining) in different groups. E Representative images of CD34 staining in different groups. Scale bar: 80 μm. F Quantitative analysis of CD34 positive area in different groups. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ns not significant.

The SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA nerve conduit has been developed to facilitate stable release of its constituent SFRP2 within the in vivo environment. The results of in vitro experiments have demonstrated that this conduit can exert a considerable impact upon the processes of angiogenesis and Schwann cell migration and proliferation. Consequently, damaged segments of the sciatic nerve were harvested at 4 weeks postoperatively to assess the biological effects of the SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA nerve conduit in vivo. Firstly, endothelial cells within the damaged nerves were labeled with CD31 (Fig. 6C, D) and angiogenesis with CD3456,57 (Fig. 6E, F). The results indicated that the number of endothelial cells in the damaged nerve segments under the SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA nerve conduit was higher and the density of microvessels was higher than that observed in the PDA@GelMA and control groups. The SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA nerve conduit has been demonstrated to effectively promote vascularization in damaged nerves in vivo, which provides essential nutrients, such as oxygen, to Schwann cells, thereby facilitating their regeneration and improving the long-term survival of axons. Furthermore, the formation of new microvessels provides tracks for Schwann cells to migrate in neural bridges, which guides axon growth58,59.

Secondly, a comprehensive evaluation was conducted to ascertain the restoration of axons and myelin sheaths in the affected ganglion segments. Remyelination of peripheral nerves is crucial for axonal extension and subsequent functional recovery60,61,62. Therefore, we employed transmission electron microscopy (TEM) to compare the myelin sheath thickness and axonal diameter in the central section of the collected sciatic nerve (Fig. 7A). The control group exhibited predominantly thin and loosely arranged myelin sheaths with evident demyelination. In the SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA group, the myelin sheath was observed to be thick and well-defined, with a notable recovery of the myelin sheath. The mean myelin thickness in the SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA groups exhibited a significantly higher value than that observed in the PDA@GelMA and control groups (quantitative statistics) (Fig. 7B). A similar trend was observed in the statistics of mean axonal diameter (Fig. S4). Furthermore, axons and myelin were labeled with NF200 and S100, respectively, and the repair of axons and myelin in peripheral nerves was accurately quantified by immunohistochemical staining. The results demonstrated that the neurofilament-positive area and myelin-positive area in the SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA group exhibited a significantly superior outcome compared to the other two groups (Fig. 7C–E). Schwann cells are known to migrate to the site of damaged peripheral nerves, where they then undertake specific phenotypic transitions in order to form new myelin sheaths. The formation of these sheaths allows for the encasement of axons and provides the foundation for subsequent axon regeneration and maturation47. The utilization of SFRP2-PDA@GelMA nerve conduits in vivo was observed to markedly enhance the migration and proliferation of Schwann cells, facilitate the restoration of myelin sheath integrity, and facilitate the regeneration of injured nerve axons.

A Representative TEM images of sciatic nerves in different groups. B Quantitative analysis of myelin sheath thickness in different groups. C Representative images of myelin sheath and axon of sciatic nerves in different groups by immunofluorescence staining. S100 (green) and NF200 (red). Scale bar: 50 μm. D Quantitative analysis of NF200 positive area in different groups. E Quantitative analysis of S100 positive area in different groups. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005, ns not significant.

The in vivo experimental results demonstrated that SFRP2-PDA@GelMA nerve conduits could stably release SFRP2 locally and effectively enhance neovascularization within damaged nerve segments, thereby promoting the reconstruction of nerve blood flow. Moreover, the reparative effect of Schwann cells on nerves was markedly augmented.

Angiogenesis and neurogenesis exhibit coordinated progression during embryonic development, with both processes being governed by overlapping molecular and cellular regulatory pathways. This synergy is also reflected in the repair of adult neural tissues after injury63. In this study, the SFRP2-PDA@GelMA nerve conduit demonstrated the capacity to concurrently enhance angiogenesis and functional recovery of Schwann cells. Appropriate angiogenesis ensures sufficient nutrition and oxygen to support the survival and regeneration of nerve cells. Furthermore, angiogenesis establishes a regenerative microenvironment conducive to repair of peripheral nerve through dual mechanisms involving inflammatory factor clearance and glial scar reduction64,65. These findings collectively suggest that angiogenesis represents a pivotal therapeutic target in nerve repair, and the dual promotion of both vascularization and neuronal functional restoration may synergistically optimize regenerative outcomes66,67,68 (Fig. S3A).

SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA conduit promotes restoration of target muscle and functional recovery without biotoxicity

To further assess the promotional effect of SFRP2-PDA@GelMA nerve conduits on nerve repair following their application, we conducted a comprehensive evaluation of the recovery of muscle function innervated by the nerve. The gastrocnemius muscle serves as a crucial indicator of functional recovery following sciatic nerve injury. At 4 weeks post-operation, bilateral gastrocnemius muscles were harvested from mice. Gross images revealed evident atrophy of the gastrocnemius muscle on the side of the crushed nerve in all experimental groups (Fig. 8A). Thus, we conducted a comparative analysis of the muscle wet-weight ratio between the healthy and affected sides. The findings revealed that the extent of gastrocnemius atrophy was markedly reduced in the SFRP2-PDA@GelMA group (Fig. 8B), suggesting a more expeditious restoration of impaired nerve function. Moreover, we employed histochemical staining techniques to more effectively contrast the variations in muscle atrophy across the experimental groups (Fig. 8C). The findings of Masson staining revealed that the mean diameter of the muscle fibers in the gastrocnemius muscle (see Fig. 8D) of the SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA group was larger and the degree of muscle atrophy was less pronounced. The normal form and function of the muscle are inextricably linked to its innervation. Following damage to the sciatic nerve, the gastrocnemius muscle is innervated and loses the nutritional function of the nerve, leading to gradual disuse atrophy69. The application of SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA nerve catheter effectively slowed down the atrophy of the gastrocnemius muscle, demonstrating its efficacy in promoting sciatic nerve repair.

A Representative images of bilateral gastrocnemius muscles at 4 weeks after surgery. B The wet weight ratios of gastrocnemius muscle. C Representative images of Masson staining of the gastrocnemius muscles. Scale bar: 100 μm. D Quantitative analysis of mean diameter of gastrocnemius muscles. E Representative images of walking footprints of mice at 4 weeks after surgery. F SFI values of different groups. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005, ns not significant.

In order to comprehensively assess the function of the gastrocnemius muscle in mice, we evaluated the sciatic functional index (SFI) of all mice prior to sacrifice (Fig. 8E). Following sciatic nerve injury, there were changes observed in toe spread among the mice. Gait analysis revealed that both the SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA group and sham group exhibited larger toe spread compared to the PDA@GelMA group and control group. SFI significantly decreased after sciatic nerve injury; SFI of mice in SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA group decreased the least, which was significantly better than that in the other two groups (Fig. 8F). The gastrocnemius function of mice was decreased to a certain extent after sciatic nerve injury. However, the functional decline of gastrocnemius was significantly improved after the application of SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA nerve catheter, which further indicated that SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA nerve catheter can effectively promote sciatic nerve repair.

In conclusion, the utilization of SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA nerve catheter has been demonstrated to effectively enhance the atrophy and functional decline of the gastrocnemius muscle, thereby indicating that it can markedly facilitate the repair of damaged sciatic nerve. Furthermore, the major organs of the mice were identified by H&E staining (Fig. S5). No evident signs of inflammation, hemorrhage, or necrosis were observed in the heart, liver, spleen, lungs, and kidneys across all three groups. This demonstrates that the SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA neural conduit also exhibits good biocompatibility in vivo.

Conclusion

We successfully constructed a multifunctional drug delivery system based on PDA@GelMA nanofilms and fabricated it into a neural conduit for application in a nerve injury model, thereby validating its promotional effect on the repair of peripheral nerve injuries. Initially, the GelMA hydrogel nanofibrous membrane (named as PDA@GelMA) was fabricated through the combination of electrospinning and photo-crosslinking techniques, followed by the PDA modification for the subsequent SFRP2 loading. The obtained SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA exhibited a sustained release capability of SFRP2 protein and effectively facilitated the proliferation and migration of Schwann cells and endothelial cells, as well as enhanced angiogenesis and alleviated inflammatory microenvironment of endothelial cells in vitro. Mechanistically, the functionality of SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA was mediated through the calcium-dependent calcineurin/NFATc3 signaling axis. After the implantation into a murine model with peripheral nerve injury. The SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA conduit has demonstrated outstanding performance in promoting peripheral nerve injury repair by simultaneously facilitating angiogenesis and nerve regeneration. The SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA conduit holds great promise for treating peripheral nerve injuries.

Experimental sections

Preparation of GelMA hydrogel nanofibers

Electrospinning was employed to fabricate nanofibrous membranes of Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA). GelMA (degree of substitution: 60%, Engineering For Life, China) was dissolved in 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFIP) to prepare the spinning solution (4% w/v). A small amount (0.3% w/v) of high molecular weight poly (ethylene oxide) (PEO, Mw ~1,000,000, Shanghai yuanye Bio-Technology, China) was added to facilitate jet formation. The electrospinning parameters were set as follows: applied voltage 6–8 kV, flow rate 20 μL/min, needle tip to drum-collector gap distance 20 cm, drum collecting speed 50 rpm, and ambient conditions. The resulting GelMA nanofibers were subsequently vacuum-dried.

To promote the formation of GelMA hydrogel nanofibers, 2-hydroxy-4’-(2-hydroxyethoxy)-2-methylpropiophenone (photoinitiator, Irgacure 2959, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was fully dissolved in anhydrous alcohol to produce a photo-crosslinking solution (5% w/v). Subsequently, the electrospun nanofibrous membranes were immersed directly in the photo-crosslinking solution for 2 h, followed by exposure to 365 nm UV light (90 W) for 10 min. Excess photoinitiator was removed by washing the GelMA hydrogel nanofibers with anhydrous alcohol, resulting in the obtained nanofibers for subsequent experiments.

PDA coating on GelMA hydrogel nanofibers

A dopamine (DA) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) solution was prepared by dissolving DA (2 mg/mL) in Tris buffer (10 mM, pH 8.5, Solarbio, China). Subsequently, the GelMA hydrogel nanofibers were immersed in the DA solution (exposed to air) and gently shaken for 24 h at room temperature. Following this, the treated nanofibers were retrieved, thoroughly rinsed, and vacuum-dried. The resulting nanofibers were designated as PDA@GelMA.

Characterization of PDA@GelMA

The surface morphology of GelMA and PDA@GelMA hydrogel nanofibers was examined using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, Sigma 300, ZEISS) with an acceleration voltage ranging from 0.02 to 30 kV. Prior to imaging, the samples were sputter-coated with a layer of gold for 60 s to enhance conductivity.

Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was performed to qualitatively analyze the GelMA and PDA@GelMA hydrogel nanofibers using an FTIR spectrometer (Thermo IS5, USA) over the wavenumber range of 4000–800 cm−1. Data collection was conducted by accumulating 32 scans with a resolution of 4 cm−1.

The surface elemental composition of GelMA and PDA@GelMA hydrogel nanofibers was analyzed using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Thermo Scientific K-Alpha+, USA) with a monochromatic Al Kα excitation source operating at an energy of 100 eV. The C 1 s and N 1 s spectra were fitted using the Gaussian-Lorentzian function in Origin 8.0 software.

The surface wettability of GelMA and PDA@GelMA hydrogel nanofibers was evaluated by measuring the water contact angle (WCA) using an optical tensiometer (Dataphysics DCAT20, Germany). In brief, 2 μL of deionized water was used as the probe liquid and dropped onto each fibrous membrane. The resulting droplets were photographed to obtain images of the water contact angle.

The mechanical properties of GelMA and PDA@GelMA hydrogel nanofibers in a wet state (after immersion in deionized water for 2 h) were characterized using a rheometer (Haake MARS III, Thermo, USA). The storage modulus (G′) and loss modulus (G″) of the samples were dynamically scanned over an angular frequency range of 0.1–10 rad s−1, at a shear amplitude of 1%.

Fabrication and biocompatibility of SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA in vitro

The recombinant mouse SFRP2 protein (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) was co-incubated with GelMA and PDA@GelMA hydrogel nanofilms for 2 h at 37 °C. Then two nanofilms were placed in PBS, and the supernatant at the 1th, 2th, 3th, and 4th week were collected and measured using a commercially available ELISA kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and mouse Schwann cells (MSCs) obtained from Shanghai Cell Bank, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). The effects of GelMA and PDA@GelMA nanofilms on the proliferation of HUVECs and MSCs were detected with CCK-8 kit (Dojindo Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan). The extracts of GelMA and PDA@GelMA nanofilm were obtained by physical damage. The blank well was considered as control group. Both HUVECs and MSCs were inoculated in 96-well plates at a density of 5 × 104 per well and cultured for 4 h at 37 °C under 5% CO2. Then these extracts were added into the wells and incubation for another 72 h. The CCK-8 assay was performed at every 24 h. The absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader (Thermo Scientific, USA). To identify the optimal concentration of SFRP2 in SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA conduit for promoting nerve repair, PDA@GelMA membranes were immersed in different concentrations of SFRP2 protein (0, 500, 1000, 1500, 2000, 2500 ng/ml) for 2 h. The extracts of SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA nanofilms were collected. Then HUVECs and MSCs were cultured with different extracts of SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA nanofilms in 96-well plate for 96 h. The cell viability was also assessed with CCK-8 assay.

To further evaluate the biocompatibility of SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA nanofilm on endothelial cells and Schwann cells, the SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA nanofilm were placed in 24-well culture plates, then HUVECs and MSCs were added onto membrane at a density of 2 × 104 cells/well and cultured for 48 h. The viability of HUVECs and MSCs was detected using calcein AM/PI staining. Specifically, the cells were washed with PBS for 3 times, and 2 μM Calcein-AM and 8 μM propidium iodide (Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd. Beijing, China) were added and incubated at room temperature for 45 min. The cells were washed again with PBS for 3 times and observed and photographed under a fluorescence microscope (BX53; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The adhesion ability of HUVECs and MSCs on different hydrogel membranes was detected by Phalloidin staining. After washed with PBS for three times, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Solarbio, China) for 45 min at room temperature and then infiltrated with 0.1% Triton X-100 (Solarbio, China) for 10 min. After washing with PBS, the cells were stained with 5 μg/mL TRITC-labeled Phalloidin (Solarbio, China) for 50 min and stained with DAPI (Solarbio, China) for 20 min. The cells were then observed and photographed using a laser confocal scanning microscope (CLSM; LSM 710; Zeiss).

Evaluation of Intracellular ROS

To investigate the effect of different hydrogel membranes on intracellular ROS, HUVECs and MSCs were seeded on separate hydrogel surfaces. Once the cell density reached an appropriate density, ROS levels were measured using the fluorescent probe 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) (Solarbio, China). Meanwhile, the positive control group (ROS-up) was established by treating cells with 200 µM H₂O₂ for 1 h, followed by ROS detection. Cells were incubated with DCFH-DA under dark conditions at room temperature for 30 min. Subsequently, an inverted fluorescence microscope was employed to observe and photograph the cells, the fluorescence intensity was analyzed semi-quantitatively using Image J software. using Image J software (NIH, USA).

Scratch assay

HUVECs and MSCs were cultured in a 6-well culture plates. When the fusion rate reached 90%, uniform cell scrapings were prepared with the tip of a 1 mL pipette gun tip and the detached cells were washed with PBS. Then PDA@GelMA and SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA extracts with serum-free medium were added to the plates, the incubation was continued for 48 h at 37 °C under 5% CO2. Serum-free medium of the control group did not contain any nanofilms extracts. Observations and photographs were taken every 24 h. After 48 h incubation, the cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 45 min under room temperature, then stained with 5% crystal violet (Solarbio, China) for half an hour, and recorded with an inverted microscope (Leica, Germany). Cell scratch images were analyzed with Image J software (NIH, USA).

Transwell assay

HUVECs and MSCs were added to the upper chamber of a 24-well Transwell plate (pore size: 8 μm; Corning, NY, USA) with 500 μl of serum-free medium. The lower chamber was filled with serum-free medium, PDA@GelMA, or SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA extracts, and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Then the upper chamber was removed, and the cells at the top were gently removed with a cotton swab, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature, and washed three times with PBS. Finally, the cells were stained with 5% crystal violet, and an inverted microscope was used to record representative images of each group.

Tube formation assay

Matrigel solution (BD Biosciences, USA) was added to the wells of pre-cooled 96-well plates and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min to allow gel formation. HUVECs were suspended in serum-free medium, PDA@GelMA or SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA extracts at a density of 2 × 104/ml. Then HUVECs suspensions were added to the solidified Matrigel (BD Biosciences, USA) and then incubated at 37 °C for 4 h. Representative images of each group were recorded using an inverted microscope. The number of junctions, junctions’ density, and vessels area were analyzed using Image J software (NIH, USA).

RNA sequencing and bioinformatics analysis

HUVECs were cultured on SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA or blank well for 48 h, then total RNA was isolated using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Transcriptome RNA sequencing was performed by Shanghai Personal Biotechnology (Shanghai, China). Reads containing adapter or ploy-Nb reads, and low-quality reads, were removed to ensure clean, high-quality data for subsequent analysis. DEGSeq2 software (ver. 1.42.0) was used for differential gene expression analysis. A corrected p value of 0.05 and absolute fold change of 2 were set as the thresholds for significantly differential expression. The clusterProfiler R package (ver. 4.8.1) was used to analyze differentially expressed genes in Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways. In this study, the volcano plot was created using the ggplot2 (ver. 3.5.2) package and the heatmap was generated using the pheatmap (ver. 1.0.12) package. The heatmap displayed the top differentially expressed genes as well as the genes corresponding to VEGF and Ang-1 respectively.

Protein extraction and western blot

HUVECs were incubated in blank well or SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA for 48 h. Proteins in HUVECs were extracted by the Protein Extraction Kit (KeyGen Biotech, China) and quantified by the Bicinchoninic Acid (BCA) Protein Quantification Kit (KeyGen Biotech, China) for quantification. Equal amounts of cleavage products were separated in SDS-PAGE gels (FDbio Science, China) and transferred to PVDF membranes (Roche Applied Sciences, Switzerland). The membranes were then closed in PBST solution (BD Difco, USA) containing 5% skimmed milk and incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibody followed by incubation with appropriate secondary antibody. Signal detection was performed using a Pico ECL kit (FDbio Science, China). Primary antibodies used in this study included β-actin (66009-1-Ig, Proteintech), β-catenin (51067-2-AP, Proteintech), nfatc3 (18222-1-AP, Proteintech), calcineurin (13422-1-AP (13422-1-AP, Proteintech), calcineurin (13422-1-AP, Proteintech), VEGF (66828-1-Ig, Proteintech), Ang-1 (27093-1-AP, Proteintech).

Detection of inflammatory cytokines in vitro

HUVECs were cultured on blank well or SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA for 48 h. The supernatants were then collected, and the levels of IL-6, TNF-α, IL-10, IL-4 were assayed using commercially available ELISA kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Surgical procedures

All animal experimental procedures in this study were approved by the Ethical Review Committee for Laboratory Animals of the Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital, Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine (Shanghai, China). In this study, the animal experimental section has been conducted by complying with the the ARRIVE Guidelines 2.070, ensuring the standardization of experimental procedures (Fig. S6). C57BL/6 mice (GemPharmatech Co, Ltd., Jiangsu, China) were anesthetized with isoflurane via inhalation. The right lateral thigh was shaved and coated with depilatory cream. Then all mice were randomly divided into four groups: control group (n = 5, the sciatic nerve was subjected to crush injury); PDA@GelMA conduit group (n = 5, the sciatic nerve was subjected to crush injury and encased in a PDA@GelMA conduit); SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA conduit group (n = 5, the sciatic nerve was subjected to crush injury and encased in a SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA conduit); and sham group (n = 5, the sciatic nerve was exposed but not subjected to crush injury). Sciatic nerve crush was performed using the previously reported method of using a uniform instrument to pinch for 30 s to create an injury of 3 mm in length71. The PDA@GelMA and SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA were curled into conduits with a length of 5 mm and wrapped around the injured sciatic nerves. The conduits were fixed with 8–0 sutures, muscles and skins were sutured with 6–0 nylon thread.

Histological analysis

Mice were euthanized at 4 weeks after surgery, and bilateral sciatic nerves were isolated and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, followed by H&E staining (abcam, US) and immunofluorescence staining, including S100β(abcam, US), NF200(abcam, US), CD31(abcam, US), CD34(abcam, US), DAPI. Meanwhile, sciatic nerves were soaked in 2.5% glutaraldehyde and subjected to TEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) scanning. Bilateral gastrocnemius muscles were obtained and weighed for recordings. The wet weight ratio was calculated as wet weight of the injured limb/ wet weight of the contralateral limb × 100%. Each muscle was sectioned and used for Masson staining (abcam, US). Myelin thickness, axon diameter, immunofluorescence, and muscle fiber diameter were measured using Image J software (NIH, USA). To evaluate the biotoxicity of SFRP2 ~ PDA@GelMA conduit in vivo, major organs including heart, liver, spleen, lung and kidney were obtained and subjected to H&E staining.

Behavioral analysis

Motor function recovery of the damaged hindlimb was assessed based on SFI, which was calculated by recording the footprints of the damaged hindlimb at 4 weeks postoperatively referring to a previous report14. An SFI value of 0 indicated the damaged hindlimb was close to normal, whereas a value close to -100 was considered as fully dysfunctional.

Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Comparison between two groups or multiple groups were conducted using Student’s t test or one-way factor analysis of variance (ANOVA). All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS 13.0 software (Inc., Chicago, IL) or Graph-Pad Prism software (San Diego, CA). Differences were considered statistically significant when a p value less than 0.05.

References

Mehrotra, P. et al. Skeletal muscle reprogramming enhances reinnervation after peripheral nerve injury. Nat. Commun. 15, 9218 (2024).

Lopes, B. et al. Peripheral nerve injury treatments and advances: one health perspective. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 918 (2022).

Vijayavenkataraman, S. Nerve guide conduits for peripheral nerve injury repair: a review on design, materials and fabrication methods. Acta Biomater. 106, 54–69 (2020).

Kornfeld, T., Borger, A. & Radtke, C. Reconstruction of critical nerve defects using allogenic nerve tissue: a review of current approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 3515 (2021).

Rahman, M., Mahady Dip, T., Padhye, R. & Houshyar, S. Review on electrically conductive smart nerve guide conduit for peripheral nerve regeneration. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 111, 1916–1950 (2023).

Park, D. et al. Micropattern-based nerve guidance conduit with hundreds of microchannels and stem cell recruitment for nerve regeneration. npj Regen. Med. 7, 62 (2022).

Gong, B. et al. Neural tissue engineering: from bioactive scaffolds and in situ monitoring to regeneration. Exploration 2, 20210035 (2022).

Buncke, G. Peripheral nerve allograft: how innovation has changed surgical practice. Plast. Aesthet. Res. 9, 38 (2022).

Park, J. et al. Electrically conductive hydrogel nerve guidance conduits for peripheral nerve regeneration. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 2003759 (2020).

Yan, Y. et al. Implantable nerve guidance conduits: material combinations, multi-functional strategies and advanced engineering innovations. Bioact. Mater. 11, 57–76 (2022).

Rahmati, M. et al. Electrospinning for tissue engineering applications. Prog. Mater. Sci. 117, 100721 (2021).

Liu, X. et al. Fatigue-resistant hydrogel optical fibers enable peripheral nerve optogenetics during locomotion. Nat. Methods 20, 1802–1809 (2023).

Chen, Z. et al. NSC-derived extracellular matrix-modified GelMA hydrogel fibrous scaffolds for spinal cord injury repair. NPG Asia Mater. 14, 20 (2022).

Ma, T. et al. Sequential oxygen supply system promotes peripheral nerve regeneration by enhancing Schwann cells survival and angiogenesis. Biomaterials 289, 121755 (2022).

Javidi, H., Ramazani, Saadatabadi, A., Sadrnezhaad, S. K. & Najmoddin, N. Conductive nerve conduit with piezoelectric properties for enhanced PC12 differentiation. Sci. Rep. 13, 12004 (2023).

Zarrintaj, P. et al. Conductive biomaterials as nerve conduits: recent advances and future challenges. Appl. Mater. Today 20, 100784 (2020).

Li, R. et al. Growth factors-based therapeutic strategies and their underlying signaling mechanisms for peripheral nerve regeneration. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 41, 1289–1300 (2020).

Qiu, C., Hanwright, P. J., Khavanin, N. & Tuffaha, S. H. Functional reconstruction of lower extremity nerve injuries. Plastic Aesthet. Res. 9, 19 (2022).

Saio, S. et al. Extracellular environment-controlled angiogenesis, and potential application for peripheral nerve regeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 11169 (2021).

Tang, Y., Shen, J., Zhang, F., Yang, F. Y. & Liu, M. Human serum albumin attenuates global cerebral ischemia/reperfusion-induced brain injury in a Wnt/β-Catenin/ROS signaling-dependent manner in rats. Biomed. Pharmacother. 115, 108871 (2019).

van Loon, K., Huijbers, E. J. M. & Griffioen, A. W. Secreted frizzled-related protein 2: a key player in noncanonical Wnt signaling and tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 40, 191–203 (2021).

Tran, T. H. N. et al. Soluble Frizzled-related proteins promote exosome-mediated Wnt re-secretion. Commun. Biol. 7, 254 (2024).

Zhang, N. et al. Delivery of Wnt inhibitor WIF1 via engineered polymeric microspheres promotes nerve regeneration after sciatic nerve crush. J. Tissue Eng. 13, 20417314221087417 (2022).

Hollis, E. R. et al. Remodelling of spared proprioceptive circuit involving a small number of neurons supports functional recovery. Nat. Commun. 6, 6079 (2015).

Kaur, A. et al. sFRP2 in the aged microenvironment drives melanoma metastasis and therapy resistance. Nature 532, 250–254 (2016).

Fane, M. E. et al. sFRP2 supersedes VEGF as an age-related driver of angiogenesis in melanoma, affecting response to anti-VEGF therapy in older patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 26, 5709–5719 (2020).

Yi, B. et al. Overview of injectable hydrogels for the treatment of myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc. Innov. Appl. 9, 960 (2024).

Yao, S. et al. Axon-like aligned conductive CNT/GelMA hydrogel fibers combined with electrical stimulation for spinal cord injury recovery. Bioact. Mater. 35, 534–548 (2024).

Zhang, B. et al. Decellularized umbilical cord wrapped with conductive hydrogel for peripheral nerve regeneration. Aggregate 6, e674 (2025).

Gong, J. et al. Polydopamine-mediated immunomodulatory patch for diabetic periodontal tissue regeneration assisted by metformin-ZIF system. ACS Nano 17, 16573–16586 (2023).

Zhuang, W. R. et al. Applications of π-π stacking interactions in the design of drug-delivery systems. J. Control Release 294, 311–326 (2019).

Kim, J. et al. A gelatin/alginate double network hydrogel nerve guidance conduit fabricated by a chemical-free gamma radiation for peripheral nerve regeneration. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 13, 2400142 (2024).

Chen, C. et al. Bioinspired hydrogel electrospun fibers for spinal cord regeneration. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1806899 (2019).

Koshy, S. T., Ferrante, T. C., Lewin, S. A. & Mooney, D. J. Injectable, porous, and cell-responsive gelatin cryogels. Biomaterials 35, 2477–2487 (2014).

Gao, S. et al. 3D-bioprinted GelMA nerve guidance conduits promoted peripheral nerve regeneration by inducing trans-differentiation of MSCs into SCLCs via PIEZO1/YAP axis. Mater. Today Adv. 17, 100325 (2023).

Seliktar, D. Designing cell-compatible hydrogels for biomedical applications. Science 336, 1124–1128 (2012).

Yi, B. et al. Lysine-doped polydopamine coating enhances antithrombogenicity and endothelialization of an electrospun aligned fibrous vascular graft. Appl. Mater. Today 25, 101198 (2021).

Yang, H.-C. et al. Mussel-inspired modification of a polymer membrane for ultra-high water permeability and oil-in-water emulsion separation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2, 10225–10230 (2014).

Yi, B., Xu, Q. & Liu, W. An overview of substrate stiffness guided cellular response and its applications in tissue regeneration. Bioact. Mater. 15, 82–102 (2022).

Evers, T. M. J., Holt, L. J., Alberti, S. & Mashaghi, A. Reciprocal regulation of cellular mechanics and metabolism. Nat. Metab. 3, 456–468 (2021).

Zhang, K. et al. Advanced smart biomaterials and constructs for hard tissue engineering and regeneration. Bone Res. 6, 31 (2018).

Gaharwar, A. K., Singh, I. & Khademhosseini, A. Engineered biomaterials for in situ tissue regeneration. Nat. Rev. Mater. 5, 686–705 (2020).

Li, L. et al. Electrospun fibers control drug delivery for tissue regeneration and cancer therapy. Adv. Fiber Mater. 4, 1375–1413 (2022).

Yi, B. C. et al. Step-wise CAG@PLys@PDA-Cu2+ modification on micropatterned nanofibers for programmed endothelial healing. Bioact. Mater. 25, 657–676 (2023).

Li, D. H. et al. Pro-vasculogenic fibers by PDA-mediated surface functionalization using cell-free fat extract (CEFFE). Biomacromolecules 25, 1550–1562 (2024).

Iwata, M., Sawada, R., Iwata, H., Kotera, M. & Yamanishi, Y. Elucidating the modes of action for bioactive compounds in a cell-specific manner by large-scale chemically-induced transcriptomics. Sci. Rep. 7, 40164 (2017).

Wei, C. et al. Advances of Schwann cells in peripheral nerve regeneration: from mechanism to cell therapy. Biomed. Pharmacother. 175, 116645 (2024).

Zoneff, E. et al. Controlled oxygen delivery to power tissue regeneration. Nat. Commun. 15, 4361 (2024).

Saffari, T. M., Mathot, F., Friedrich, P. F., Bishop, A. T. & Shin, A. Y. Revascularization patterns of nerve allografts in a rat sciatic nerve defect model. J. Plast., Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 73, 460–468 (2020).

Muangsanit, P., Roberton, V., Costa, E. & Phillips, J. B. Engineered aligned endothelial cell structures in tethered collagen hydrogels promote peripheral nerve regeneration. Acta Biomater. 126, 224–237 (2021).

Vatner, D. E., Oydanich, M., Zhang, J., Babici, D. & Vatner, S. F. Secreted frizzled-related protein 2, a novel mechanism to induce myocardial ischemic protection through angiogenesis. Basic Res. Cardiol. 115, 48 (2020).

Yang, J., Xiong, G., He, H. & Huang, H. SFRP2 modulates functional phenotype transition and energy metabolism of macrophages during diabetic wound healing. Front. Immunol. 15, 1432402 (2024).

Liang, C. J. et al. SFRPs are biphasic modulators of Wnt-signaling-elicited cancer stem cell properties beyond extracellular control. Cell Rep. 28, 1511–1525.e1515 (2019).

Zhang, T. et al. LDH-doped gelatin-chitosan scaffold with aligned microchannels improves anti-inflammation and neuronal regeneration with guided axonal growth for effectively recovering spinal cord injury. Appl. Mater. Today 34, 101884 (2023).

Zhang, F. et al. Combination therapy with ultrasound and 2D nanomaterials promotes recovery after spinal cord injury via Piezo1 downregulation. J. Nanobiotechnology 21, 91 (2023).

Siemerink, M. J. et al. CD34 marks angiogenic tip cells in human vascular endothelial cell cultures. Angiogenesis 15, 151–163 (2012).

Jiang, L. et al. Nonbone marrow CD34(+) cells are crucial for endothelial repair of injured artery. Circ. Res. 129, e146–e165 (2021).

Wariyar, S. S., Brown, A. D., Tian, T., Pottorf, T. S. & Ward, P. J. Angiogenesis is critical for the exercise-mediated enhancement of axon regeneration following peripheral nerve injury. Exp. Neurol. 353, 114029 (2022).

Wang, G. et al. Blood vessel remodeling in late stage of vascular network reconstruction is essential for peripheral nerve regeneration. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 7, e10361 (2022).

Salzer, J. L. Schwann cell myelination. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 7, a020529 (2015).

Caprariello, A. V. & Adams, D. J. The landscape of targets and lead molecules for remyelination. Nat. Chem. Biol. 18, 925–933 (2022).

Taveggia, C., Feltri, M. L. & Wrabetz, L. Signals to promote myelin formation and repair. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 6, 276–287 (2010).

Namini, M. S., Ebrahimi-Barough, S., Daneshimehr, F. & Ai, J. in Biomaterials for Vasculogenesis and Angiogenesis (eds Kargozar, S. & Mozafari, M.) 111–145 (Woodhead Publishing, 2022).

Lee, J.-H., Parthiban, P., Jin, G.-Z., Knowles, J. C. & Kim, H.-W. Materials roles for promoting angiogenesis in tissue regeneration. Prog. Mater. Sci. 117, 100732 (2021).

Eelen, G., Treps, L., Li, X. & Carmeliet, P. Basic and therapeutic aspects of angiogenesis updated. Circ. Res. 127, 310–329 (2020).

Xiao, Y. & Czopka, T. Myelination-independent functions of oligodendrocyte precursor cells in health and disease. Nat. Neurosci. 26, 1663–1669 (2023).

Dong, X. et al. An injectable and adaptable hydrogen sulfide delivery system for modulating neuroregenerative microenvironment. Sci. Adv. 9, eadi1078 (2023).

Yuan, T. et al. All-in-one smart dressing for simultaneous angiogenesis and neural regeneration. J. Nanobiotechnology 21, 38 (2023).

Ömeroğlu, H. & Ömeroğlu, S. In Musculoskeletal Research and Basic Science (ed. Korkusuz, F.) 443–451 (Springer International Publishing, 2016).

Percie du Sert, N. et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: updated guidelines for reporting animal research. PLOS Biol. 18, e3000410 (2020).

Huang, Q. et al. Graphene foam/hydrogel scaffolds for regeneration of peripheral nerve using ADSCs in a diabetic mouse model. Nano Res. 15, 3434–3445 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The work described in this paper was partially supported by the fundamental research program funding of Ninth People’s Hospital affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (JYZZ161), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82302388), Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. ZR2024QH150), Qingdao Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. 23-2-1-132-zyyd-jch). The National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82470510).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The experiments were conducted and supervised by L.Z., P.Q., and S.S., who also undertook data analysis and manuscript drafting. J.Q., Z.X., Y.Z., J.L., H.P., and J.L. contributed to the conceptualization of the project and provided revisions for the manuscript. L.Z. acknowledges X.L., B.Y., M.Y., Y.C., Q.H.’s support in conceptualization and funding. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, L., Qiu, P., Shen, S. et al. Polydopamine-modified hydrogel nanofibers for sustained SFRP2 release: synergistic promotion of angiogenesis and nerve regeneration. NPG Asia Mater 17, 29 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41427-025-00610-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41427-025-00610-x