Abstract

While hyperuricemia is recognized as a risk factor for chronic kidney disease (CKD), the risk of CKD in subjects with a low level of serum uric acid (UA) remains controversial. Here, we examined whether the association of CKD risk with serum UA level differs depending on the sex and age of subjects in a general population. Of subjects who received annual health checkups, we enrolled 6,779 subjects (male/female: 4,454/2,325; age: 45 ± 9 years) with data from a 10-year follow-up after excluding subjects taking anti-hyperuricemic drugs and those with CKD at baseline. During the follow-up period, 11.4% of the males and 11.7% of the females developed CKD. A significant interaction of sex, but not age, with the effect of baseline UA level on CKD risk was found. A restricted cubic spline analysis showed a U-shaped association of the baseline UA level with the risk of CKD in females. Multivariable Cox proportional hazard analyses for females showed that baseline UA levels in the 5th quintile (Q5, ≥5 mg/dL; HR: 1.68) and the 1st quintile (Q1, ≤3.5 mg/dL; HR: 1.73) were independent risk factors for CKD when compared with UA levels in the 4th quintile (Q4, 4.5–4.9 mg/dL). In males, restricted cubic spline analysis indicated increased CKD risk in subjects with a higher baseline UA level but not in those with a low UA level. In conclusion, a low UA level is a significant risk factor for CKD in females, while an elevated UA level increases the risk of CKD in both sexes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hyperuricemia is widely recognized as a risk factor for cardiovascular events [1,2,3] and the development of chronic kidney disease (CKD) [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. Interestingly, hypouricemia has also been reported to be associated with increased cardiovascular disease mortality [2, 3]. However, the relationship between low serum uric acid (UA) levels and the time course of renal function decline is controversial because of discrepant findings reported in the literature. In a cross-sectional study, hypouricemia was found to be associated with reduced renal function in males but not in females [15]. A prospective cohort study showed a U-shaped relationship between serum UA level and loss of kidney function in healthy males but not in healthy females [9]. A retrospective cohort study also showed a U-shaped relationship between UA level and the development of CKD in males [10]. On the other hand, in patients with IgA nephropathy, a U-shaped association between serum UA level and poor renal survival was found in females but not in males [11]. A significant association between hypouricemia and a decline in renal function was not observed in other studies [5,6,7,8, 12,13,14]. The reasons for the discrepancies among the results of studies have not been elucidated.

It has been shown that serum UA levels are higher in male subjects than in female subjects in a general population [16]. One possible reason for the sex difference is the UA-lowering action of estrogen in females [17,18,19]. In contrast to the findings of serum UA levels, vulnerability of the kidney to hyperuricemia-associated damage has been shown to be higher in females than in males [14, 20]. In addition to the sex difference, age seems to influence the impact of serum UA on renal function. Age is a major determinant of the natural history of renal function, and it is often accompanied by risk factors other than hyperuricemia, such as elevated blood pressure and glucose intolerance. In fact, a recent meta-analysis of 15 cohort studies revealed that serum UA levels were independently associated with the risk of CKD in middle-aged adults (age < 60 years) but not in elderly individuals (age ≥ 60 years) [4]. Based on the findings of earlier studies [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20], we postulated that the inconsistent findings regarding the impact of hypouricemia on the time course of renal function decline can be explained by the heterogeneity of study subjects and the fact that hypouricemia and hyperuricemia are independent risk factors for CKD in distinct subgroups of subjects of different sexes and/or ages. To examine this possibility, we investigated the relationship between the basal level of serum UA and the decline in renal function during a 10-year follow-up period in a general population and examined the interactions of the UA level with sex and age.

Methods

In this study, a retrospective analysis of data from a cohort was conducted as the second project for CKD of the Broad-range Organization for Renal, Arterial, and Cardiac Studies by Sapporo Medical University affiliates (BOREAS)-CKD2. This project was designed and conducted separately from the previous study BOREAS-CKD1 [14]. This study conformed to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and was performed with the approval of the institutional ethics committee of Sapporo Medical University (number: 29–2–64). Written informed consent was obtained from all of the study subjects.

Study subjects and clinical outcomes

All subjects who received annual medical checkups at Keijinkai Maruyama Clinic, Sapporo, in 2006 were enrolled in this registry. Subjects who did not undergo a full set of laboratory examinations in 2006, subjects who had not received medical checkups or laboratory examinations in 2016, subjects who had been treated with anti-hyperuricemic drugs in 2006, and subjects who had an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 at baseline in 2006 were excluded from this study. The distribution of UA levels was divided into quintiles. The clinical endpoint was the development of CKD defined as a decline in eGFR to <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 [21]. The clinical endpoint and the use of anti-hyperuricemic drugs were assessed at the time of each annual health checkup during a 10-year period from 2006 to 2016.

Measurements

Medical examinations, including blood pressure measurements and samplings of urine and blood, were performed in the early morning after an overnight fast. Urinary protein was qualitatively examined by a dipstick method. eGFR was calculated from data for serum creatinine, age and sex using equations for the Japanese population [22]. A self-administered questionnaire survey was performed to obtain information on smoking, exercise, and alcohol consumption habits as well as medications, including anti-hypertensive drugs, lipid-lowering drugs, antidiabetic drugs, and anti-hyperuricemic drugs. Body height and weight were measured with the participant in light clothing without shoes, and body mass index (BMI) was calculated as body weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. The Brinkman index was obtained by multiplication of the average number of cigarettes smoked per day by smoking years. Regular exercise was classified as follows: mild, desk work, or few opportunities to walk; moderate, stand-up work, or habits of exercising occasionally; and vigorous, manual labor, or habits of exercising daily. Alcohol drinking habits were defined as drinking alcohol beverages more than 5 days a week.

Statistical analysis

Numeric variables are expressed as the means ± SDs for parameters with normal distributions or medians (interquartile ranges) for parameters with skewed distributions. The distribution of each parameter was tested for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Comparisons between two groups were performed with Student’s t test for parametric parameters. Intergroup differences in percentages of demographic parameters were examined by the chi-square test. One-way analysis of variance was used to detect significant differences in data between multiple groups. The hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for the development of CKD were calculated by using a Cox proportional hazard model with adjustment for confounders, including age, eGFR, BMI, systolic blood pressure, hemoglobin, albumin, urinary protein, Brinkman index, regular exercise, alcohol drinking habit, use of drugs for dyslipidemia, and use of drugs for diabetes mellitus at baseline. These confounders were selected on the basis of a causal diagram analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1A) using the graphical tool DAGitty [23, 24]. The use of drugs for dyslipidemia and diabetes mellitus at baseline were considered to indicate the presence of dyslipidemia and diabetes mellitus, respectively, in this study. The use of anti-hyperuricemic drugs during a 10-year follow-up period was assessed at annual health checkups, and the duration of treatment with anti-hyperuricemic drugs during the follow-up period was also adjusted in the model as a time-dependent variable (Supplementary Fig. 1B). Since there was a significant interaction between baseline UA level and sex in regard to the impact on the clinical endpoint (see Results), we analyzed data for males and females separately. We first examined the relationship between serum UA level and the HR for the development of CKD by a multivariable-adjusted Cox proportional hazard model with a restricted cubic spline. In addition, HRs in five subgroups according to quintiles of baseline serum UA level (Q1–Q5) were calculated and compared. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data were analyzed by using EZR software [25] and R version 3.6.1.

Results

Baseline characteristics

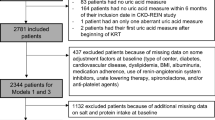

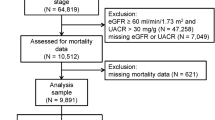

A total of 28,990 Japanese subjects received medical checkups in 2006 at Keijinkai Maruyama Clinic (Fig. 1). Among the subjects, 22,211 were excluded from the analysis for the following reasons: 7478 due to a lack of a full set of laboratory data in 2006, 14,415 due to not participating in medical checkups in 2016, 194 for treatment with anti-hyperuricemic drugs in 2006, and 124 due to low eGFR (<60 ml/min/1.73 m2) in 2006. Thus, a total of 6779 subjects (male/female: 4454/2325; mean age: 45 ± 9 years) were enrolled for analyses in the present study. The mean follow-up period was 9.6 years (range: 1–10 years), and the total follow-up was 64,850 (male/female; 42,812/22,038) persons-years.

The baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the study subjects are summarized in Table 1. Uric acid levels were significantly higher in male subjects than in female subjects (6.1 ± 1.2 vs. 4.3 ± 0.9 mg/dL, P < 0.001). Comparisons of the study subjects subgrouped by UA quintiles for males and females are shown in Table 2 and Table 3, respectively. In male subjects, higher UA quintiles were associated with higher BMI; higher systolic and diastolic blood pressures; higher levels of LDL cholesterol, triglycerides, and hemoglobin; and lower levels of eGFR and HDL cholesterol (Table 2). In females, higher UA quintiles were associated with more advanced age; higher BMI; higher systolic and diastolic blood pressures; higher levels of LDL cholesterol, triglycerides, and hemoglobin; lower eGFR and HDL cholesterol; and a higher percentage of subjects on anti-hypertensive drugs (Table 3).

Uric acid level and risk of CKD development

During the follow-up period, CKD developed in 509 male subjects (11.4%) and 271 female subjects (11.7%). The numbers of male and female subjects who had been treated with anti-hyperuricemic drugs during the follow-up period were 373 (8.4%) and 8 (0.3%), respectively, and the difference between the numbers of males and females was statistically significant (P < 0.001). The analysis of the interaction indicated a significant interaction between sex and baseline serum UA level in regard to the risk of CKD development (P = 0.04). Thus, we performed the following analyses separately for males and females.

In male subjects, a restricted cubic spline analysis showed that the risk of CKD development after adjustment for confounders, including age at baseline, increased with higher baseline UA levels (Fig. 2a). When the 1st quintile (Q1) of UA was used as the reference, multivariable Cox proportional hazard model analysis showed no significant difference in the incidence of CKD development between the five UA quintile subgroups (Q1–Q5), though HR tended to be higher in Q5 (Fig. 2b).

Hazard ratio of the development of CKD by baseline uric acid levels in male subjects. a A multivariable-adjusted restricted cubic spline of the hazard ratio (HR) for the development of chronic kidney disease (CKD) by baseline uric acid levels in male subjects after adjustment for age, estimated glomerular filtration rate, BMI, systolic blood pressure, hemoglobin, albumin, urinary protein, Brinkman index, regular exercise, alcohol consumption habit, use of drugs for dyslipidemia, and diabetes mellitus at baseline and the duration of treatment with anti-hyperuricemic drugs during a 10-year follow-up period. Solid line: hazard ratio; dashed line: 95% confidence interval (CI). The reference value of uric acid was 0.6 mg/dL b HR and 95% CI for the development of CKD by quintiles of baseline uric acid levels in male subjects analyzed by a multivariable Cox proportional hazard model after adjustment of the above confounders

In female subjects, a restricted cubic spline analysis showed that the risk of CKD development after adjustment for confounders exhibited a U-shaped association (Fig. 3a). When the 4th quintile (Q4) of UA (UA of 4.5–4.9 mg/dL) was used as the reference, the HR for CKD development in female subjects was higher not only in the Q5 subgroup (UA ≥ 5 mg/dL; HR: 1.68 [1.14–2.47]) but also in the Q1 subgroup (≤3.5 mg/dL; HR: 1.73 [1.08–2.77]) (Fig. 3b).

Hazard ratio of the development of CKD by baseline uric acid levels in female subjects. a A multivariable-adjusted restricted cubic spline of the hazard ratio (HR) for the development of chronic kidney disease (CKD) by baseline uric acid levels in female subjects after adjustment for age, estimated glomerular filtration rate, BMI, systolic blood pressure, hemoglobin, albumin, urinary protein, Brinkman index, regular exercise, alcohol consumption habit, use of drugs for dyslipidemia, and diabetes mellitus at baseline and the duration of treatment with anti-hyperuricemic drugs during a 10-year follow-up period. Solid line: hazard ratio; dashed line: 95% confidence interval (CI). The reference value of uric acid was 4.5 mg/dL b HR and 95% CI for the development of CKD by quintiles of baseline uric acid levels in female subjects analyzed by a multivariable Cox proportional hazard model after adjustment of the above confounders

In contrast to the sex difference, age was not shown to significantly interact with the baseline serum UA level with respect to the risk of CKD development in the analysis of overall study subjects (P = 1.00), male subjects alone (P = 0.12), or female subjects alone (P = 0.90). We additionally performed subgroup analyses by dividing the study subjects according to tertiles of age (i.e., aged < 42 years, 42–48 years, and >48 years in males, aged < 41 years, 41–47, and >47 years in females). However, there was no significant difference in the UA level–CKD risk relationship between the tertile subgroups of males or females.

Discussion

As a novel finding, the present study showed that low serum UA levels in females in a general population were associated with an increased risk of CKD development. Although such an association has been suggested by a few earlier studies [9, 11], we employed approaches to critically test the relationship. First, we examined the relationship between the serum UA level and incidence of CKD using two statistical methods: a multivariable-adjusted Cox proportional hazard model with a restricted cubic spline and calculation of HRs in UA quintile subgroups. Second, we excluded subjects who were receiving pharmacological treatment for hyperuricemia at baseline and conducted comprehensive adjustment of confounders, including duration of treatment with an anti-hyperuricemic agent during the follow-up period. There was a U-shaped relationship between the baseline serum UA level and the risk of CKD development in females, while male subjects with a low UA level did not show increased CKD risk. Although we postulated that both sex and age impact the association of serum UA level with the risk of CKD, an interaction of age was not supported by the results of the present study.

The impact of changes in serum UA levels on the incidence of CKD has been examined in cohort studies [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14], a cross-sectional study [15], and a meta-analysis of 15 cohort studies [4], the results of which have consistently indicated that a high level of serum UA is a risk factor for CKD (Table 4). However, the association of low UA levels with the risk of CKD has not been fully characterized. A cross-sectional study by Wakasugi et al. [15] in which 90,710 male and 136,935 female subjects were enrolled showed that hypouricemia (UA level ≤ 2 mg/dl) was associated with eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 in male subjects (odds ratio: 1.83 [95% CI, 1.23–2.74]) but not in female subjects. A retrospective cohort study by Mun et al. [10] showed that both high and low serum UA levels were risk factors for CKD development in males, while only a high UA level was associated with CKD development in females. In a cohort study by Kanda et al. in which healthy people were enrolled [9], an increased risk of CKD was observed in males with low or high serum UA levels but not in females. However, when a decline in eGFR of ≥25% during the follow-up was used as an endpoint, an association of low UA levels and eGFR decline was observed in subgroups of subjects with a low serum UA level (males, <5 mg/dl; females, <3.6 mg/dl) [9]. A study focusing on patients with IgA nephropathy showed that there was a U-shaped association between serum UA level and poor renal survival in female patients [11]. The present study showed for the first time a significant association of low serum UA levels with an increased risk of CKD development in females in a general population (Fig. 2a, b). The difference of these results compared with the results of earlier studies may be attributable to differences in study design, such as the exclusion of patients treated with anti-hyperuricemic drugs at baseline and the inclusion of the duration of treatment with anti-hyperuricemic drugs during the follow-up period as a confounding variable.

The mechanism by which a low serum level of UA is associated with an increased risk of CKD in females remains unclear. However, some speculations can be made. Since UA itself has an antioxidant effect [26,27,28], a decrease in circulating UAs might reduce tissue tolerance to oxidative stress-mediated injury. A low serum UA level was also suggested to reduce eGFR by constricting afferent arterioles in the kidney [29]. Uedono et al. [29] reported that serum UA levels have a U-shaped association with the resistance of afferent arterioles in the kidney in healthy adults. A cross-sectional study by Lee et al. [30] showed that UA levels have a U-shaped association with arterial stiffness assessed by brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity in postmenopausal females, suggesting that the arteriole changes associated with low serum UA are not specific to the kidney.

It is possible that some females with hypouricemia have paradoxically increased activity of xanthine oxidoreductase (XOR). XOR catalyzes the formation of UA from hypoxanthine and xanthine, which potentially increases the levels of superoxide and reactive oxygen species [31]. We and others previously demonstrated that plasma XOR activity is associated with obesity, smoking, liver dysfunction, hyperuricemia, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, and adipokines [32,33,34,35]. Furthermore, we unexpectedly found that some elderly female subjects with relatively low levels of UA had significantly elevated XOR activities, and most of those subjects had obesity, liver dysfunction, and insulin resistance [36]. Nevertheless, the clinical and metabolic profiles of patients with a low serum level of UA need to be further characterized to clarify how hypouricemia is linked to increased CKD risk. In clinical practice, it is uncertain whether normalizing UA levels improves renal prognosis in elderly females with low UA levels. However, improving lifestyle-related diseases may prevent the hypouricemia-associated risk of CKD by reducing the inadequate activation of XOR activity.

Some groups of investigators reported a significant relationship between the lower quartile of serum UA level and an increased decline in renal function during follow-up in males (Table 4) [9, 10, 15]. However, such a relationship was not found for male subjects in the present study. We do not have a clear explanation for the differences in results, though the number of male subjects with a very low serum uric level in the present study might have been insufficient for detection of the impact of hypouricemia on eGFR decline in males.

This study has several limitations. First, a selection bias of subjects may exist in the present study since 22,221 of 28,990 subjects were excluded because of data defects in 2006, not attending checkups in 2016 and the presence of hyperuricemic therapy or CKD at baseline. Most of the subjects in this study were employees of companies and their family members in Sapporo, and most of the companies allow employees to select a clinic for annual health checkups from several health checkup centers. Thus, we speculate that participants moving from Sapporo and changing their clinic for health checkups are the main reasons for data unavailability in 2016. Second, we could not monitor new-onset CKD every 3 or 4 months to confirm that eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 was chronic because the present study was designed by using subjects who received “annual” health checkups. Therefore, we could not exclude acute kidney injury cases, if any, that were overlooked by a self-administered questionnaire. In addition, subjects might have had opportunities to receive guidance for lifestyle change and therapy during intervals between annual checkups. Thus, we cannot exclude the possibility of misclassification of CKD in some of the study subjects. Third, data for lifestyle factors, including dietary habits, affecting serum UA levels were not obtained from the subjects and thus could not be incorporated into the multivariate analyses. Fourth, since CKD development was defined using only eGFR because of the lack of quantitative data for proteinuria in the present study, the impact of low-and high-serum UA levels on the risk of CKD defined by proteinuria remains unclear. Finally, we did not exclude subjects taking anti-hypertensive agents and/or anti-diabetic medications. Thus, we cannot exclude the possibility that some of the medications, such as losartan, irbesartan, thiazide diuretic, fenofibrate, and sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, might have affected UA level and/or eGFR data as unadjusted confounding factors.

In conclusion, a U-shaped association between baseline serum UA level and the development of CKD during a 10-year period was observed in female subjects. In both male and female subjects, high levels of UA were associated with the development of CKD. A significant interaction of age with the impact of serum UA on the incidence of new-onset CKD was not demonstrated. The findings suggest that the risk of CKD associated with changes in serum UA levels differs by sex but not age.

References

Feig DI, Kang DH, Johnson RJ. Uric acid and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1811–21.

Verdecchia P, Schillaci G, Reboldi G, Santeusanio F, Porcellati C, Brunetti P. Relation between serum uric acid and risk of cardiovascular disease in essential hypertension. The PIUMA study. Hypertension 2000;36:1072–8.

Zhang W, Iso H, Murakami Y, Miura K, Nagai M, Sugiyama D, et al. Serum uric acid and mortality form cardiovascular disease: EPOCH-JAPAN study. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2016;23:692–703.

Zhu P, Liu Y, Han L, Xu G, Ran JM. Serum uric acid is associated with incident chronic kidney disease in middle-aged populations: a meta-analysis of 15 cohort studies. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e100801.

Iseki K, Ikemiya Y, Inoue T, Iseki C, Kinjo K, Takishita S. Significance of hyperuricemia as a risk factor for developing ESRD in a screened cohort. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;44:642–50.

Obermayr RP, Temml C, Gutjahr G, Knechtelsdorfer M, Oberbauer R, Klauser-Braun R. Elevated uric acid increases the risk for kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:2407–13.

Bellomo G, Venanzi S, Verdura C, Saronio P, Esposito A, Timio M. Association of uric acid with change in kidney function in healthy normotensive individuals. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;56:264–72.

Kamei K, Konta T, Hirayama A, Suzuki K, Ichikawa K, Fujimoto S, et al. A slight increase within the normal range of serum uric acid and the decline in renal function: associations in a community-based population. Nephrol Dial Transpl. 2014;29:2286–92.

Kanda E, Muneyuki T, Kanno Y, Suwa K, Nakajima K. Uric acid level has a U-shaped association with loss of kidney function in healthy people: a prospective cohort study. PLoS ONE 2015;10:e0118031.

Mun KH, Yu GI, Choi BY, Kim MK, Shin MH, Shin DH. Effect of uric acid on the development of chronic kidney disease: the Korean multi-rural communities cohort study. J Prev Med Public Health. 2018;51:248–56.

Matsukuma Y, Masutani K, Tanaka S, Tsuchimoto A, Fujisaki K, Torisu K, et al. A J-shaped association between serum uric acid levels and poor renal survival in female patients with IgA nephropathy. Hypertens Res. 2017;40:291–7.

Wang S, Shu Z, Tao Q, Yu C, Zhan S, Li L. Uric acid and incident chronic kidney disease in a large health check-up population in Taiwan. Nephrol (Carlton). 2011;16:767–76.

Takae K, Nagata M, Hata J, Mukai N, Hirakawa Y, Yoshida D, et al. Serum uric acid as a risk factor for chronic kidney disease in a Japanese community- the Hisayama study. Circ J. 2016;80:1857–62.

Akasaka H, Yoshida H, Takizawa H, Hanawa N, Tobisawa T, Tanaka M, et al. The impact of elevation of serum uric acid level on the natural history of glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and its sex difference. Nephrol Dial Transpl. 2014;29:1932–9.

Wakasugi M, Kazama JJ, Narita I, Konta T, Fujimoto S, Iseki K, et al. Association between hypouricemia and reduced kidney function: a cross-sectional population-based study in Japan. Am J Nephrol. 2015;41:138–46.

Mikkelsen WM, Dodge HJ, Valkenburg H. The distribution of serum uric acid values in a population unselected as to Gout or Hyperuricemia: Tecumseh, Michigan 1959-1960. Am J Med. 1965;39:242–51.

Hosoyamada M, Takiue Y, Shibasaki T, Saito H. The effect of testosterone upon the urate reabsorptive transport system in mouse kidney. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2010;29:574–9.

Takiue Y, Hosoyamada M, Kimura M, Saito H. The effect of female hormones upon urate transport systems in the mouse kidney. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2011;30:113–9.

Yahyaoui R, Esteva I, Haro-Mora JJ, Almaraz MC, Morcillo S, Rojo-Martinez G, et al. Effect of long-term administration of cross-sex hormone therapy on serum and urinary uric acid in transsexual persons. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:2230–3.

Lee JE, Kim YG, Choi YH, Huh W, Kim DJ, Oh HY. Serum uric acid is associated with microalbuminuria in prehypertension. Hypertension 2006;47:962–7.

Levey AS, Coresh J, Balk E, Kausz AT, Levin A, Steffes MW, et al. National Kidney Foundation practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:137–47.

Matsuo S, Imai E, Horio M, Yasuda Y, Tomita K, Nitta K, et al. Revised equations for estimated GFR from serum creatinine in Japan. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53:982–92.

Greenland S, Pearl J, Robins JM. Causal diagrams for epidemiologic research. Epidemiology 1999;10:37–48.

Textor J, Hardt J, Knuppel S. DAGitty: a graphical tool for analyzing causal diagrams. Epidemiology 2011;22:745.

Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2013;48:452–8.

Johnson RJ, Lanaspa MA, Gaucher EA. Uric acid: a danger signal from the RNA world that may have a role in the epidemic of obesity, metabolic syndrome, and cardiorenal disease: evolutionary considerations. Semin Nephrol. 2011;31:394–9.

Ames BN, Cathcart R, Schwiers E, Hochstein P. Uric acid provides an antioxidant defense in humans against oxidant- and radical-caused aging and cancer: a hypothesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:6858–62.

Davies KJ, Sevanian A, Muakkassah-Kelly SF, Hochstein P. Uric acid-iron ion complexes. A new aspect of the antioxidant functions of uric acid. Biochem J. 1986;235:747–54.

Uedono H, Tsuda A, Ishimura E, Nakatani S, Kurajoh M, Mori K, et al. U-shaped relationship between serum uric acid levels and intrarenal hemodynamic parameters in healthy subjects. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2017;312:F992–F7.

Lee H, Jung YH, Kwon YJ, Park B. Uric acid level has a j-shaped association with arterial stiffness in Korean Postmenopausal women. Korean J Fam Med. 2017;38:333–7.

Nishino T, Okamoto K. Mechanistic insights into xanthine oxidoreductase from development studies of candidate drugs to treat hyperuricemia and gout. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2015;20:195–207.

Furuhashi M, Matsumoto M, Tanaka M, Moniwa N, Murase T, Nakamura T, et al. Plasma Xanthine Oxidoreductase Activity as a novel biomarker of metabolic disorders in a general population. Circ J. 2018;82:1892–9.

Washio KW, Kusunoki Y, Murase T, Nakamura T, Osugi K, Ohigashi M, et al. Xanthine oxidoreductase activity is correlated with insulin resistance and subclinical inflammation in young humans. Metabolism 2017;70:51–6.

Furuhashi M, Matsumoto M, Murase T, Nakamura T, Higashiura Y, Koyama M, et al. Independent links between plasma xanthine oxidoreductase activity and levels of adipokines. J Diabetes Investig. 2019;10:1059–67.

Furuhashi M, Koyama M, Matsumoto M, Murase T, Nakamura T, Higashiura Y, et al. Annual change in plasma xanthine oxidoreductase activity is associated with changes in liver enzymes and body weight. Endocr J. 2019;66:777–86.

Furuhashi M, Mori K, Tanaka M, Maeda T, Matsumoto M, Murase T, et al. Unexpected high plasma xanthine oxidoreductase activity in female subjects with low levels of uric acid. Endocr J. 2018;65:1083–92.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all of the study subjects who allowed the use of their medical checkup data for clinical studies, including the present study. We are also grateful to Dr. Tsuyoshi Yamamura for valuable discussion.

Funding

This study was supported by 2017 and 2018 Grants for Education and Research from Sapporo Medical University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mori, K., Furuhashi, M., Tanaka, M. et al. U-shaped relationship between serum uric acid level and decline in renal function during a 10-year period in female subjects: BOREAS-CKD2. Hypertens Res 44, 107–116 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-020-0532-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-020-0532-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Annual change in eGFR in renal hypouricemia: a retrospective pilot study

Clinical and Experimental Nephrology (2025)

-

Hyperuricemia and elevated uric acid/creatinine ratio are associated with stages III/IV periodontitis: a population-based cross-sectional study (NHANES 2009–2014)

BMC Oral Health (2024)

-

Development of risk models for early detection and prediction of chronic kidney disease in clinical settings

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Correlation between the increase in serum uric acid and the rapid decline in kidney function in adults with normal kidney function: a retrospective study in Urumqi, China

BMC Nephrology (2023)

-

An increase in calculated small dense low-density lipoprotein cholesterol predicts new onset of hypertension in a Japanese cohort

Hypertension Research (2023)