Abstract

Hard-flaccid syndrome (HFS) is a rare condition characterised by a semi-rigid penis in the flaccid state, often accompanied by perineal and urinary symptoms. It may also induce psychological distress, which can exacerbate physical symptoms, creating a vicious cycle. There is currently no standardised treatment for HFS, and management typically focuses on addressing both the underlying causes and presenting symptoms. A systematic review of the literature identified 8 eligible studies. Although the exact aetiopathogenesis remains unclear, it is hypothesised that an initial penile trauma may trigger a cascade of neurovascular and inflammatory events. The associated psychological impact may further perpetuate symptoms, reinforcing the cycle of dysfunction. Common symptoms include perineal pain, urinary disturbances, and erectile and ejaculatory dysfunction. Evaluation involves a comprehensive clinical history, relevant blood and radiological investigations to exclude other pathologies, and the use of symptom questionnaires. Reported treatments include phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors, anxiolytics, low-intensity shockwave therapy, pelvic floor physical therapy, spinal surgery, and biopsychosocial therapy. Management should be individualised, with a focus on relieving symptoms and breaking the self-perpetuating cycle of HFS. Further evidence-based studies are needed to better understand the pathophysiology of HFS, as well as to develop clear diagnostic criteria and management guidelines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hard-flaccid syndrome (HFS) is characterised by a semi-rigid penis in the flaccid state which may be associated with other erectile, urinary, ejaculatory, perineal and psychological symptoms [1]. Similar to other male sexual dysfunctions, HFS may cause distress, frustration and interpersonal issues [1]. HFS was first reported and described by Gul et al. following a review of complaints on a hard-flaccid state shared by patients on internet forums and chat groups [2, 3]. The aetiology is not entirely clear but may be related to a trauma-associated event causing injury to the neurovasculature resulting in a complex of erectile, sensory, urinary and musculature symptoms [1]. Goldstein and Komisaruk suggested that HFS associated penile pain is a form of genito-pelvic dysesthesia and may be secondary to pathological activation of a pelvic/pudendal-hypogastric reflex [4, 5].

Due to the rarity of this syndrome and lack of familiarity among clinicians [6], there are no established consensus or guidelines on the diagnostic criteria, workup or management of HFS. Current treatments used include phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors (PDE5i) with or without low-intensity shockwave therapy (Li-SWT) [2, 7], pelvic floor physical therapy [7,8,9] and biopsychosocial therapy [8]. Results from a survey demonstrated that the effects of various biopsychosocial interventions are not promising, and patients are not completely satisfied with treatments they received [10]. Current knowledge on HFS arise from case reports, mainly coming from Europe, USA and China. We aimed to perform a systematic review to summarise current perspectives on the aetiopathogenesis, current presentations and how HFS have been managed by other centres who have encountered such cases in order to shed more light on this disorder.

Methods

The systematic review was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42025634962) and performed with reference to the the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines (Supplementary Table 1) [11].

Study inclusion and exclusion criteria

Our inclusion criteria followed the PICOS framework [12]:

Population (P): men with hard-flaccid syndrome; Intervention (I): any medical or surgical treatment including pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, physical therapy; Comparison (C): any of the above interventions; Outcome (O): clinical assessment, investigations and treatment outcomes; Study (S): all study and article types including congress abstracts were included. Men without HFS were excluded, as well as articles not in English.

Search strategy

A search on Medline/PubMed, Embase and Cochrane library using the terms “hard flaccid” OR “hard-flaccid” between 01st January 2018 and 13th April 2025 was performed. We decided to search from 2018 onwards because HFS was initially described at around that time. The titles and abstracts of the articles retrieved from the search were screened for eligibility (KHP and JRF) according to our pre-defined PICOS inclusion criteria. Included abstracts were selected for full-text review. Reference lists of the included full-text articles were also screened for eligible studies.

Data extraction

Data were collected (KHP and JRF) according to a pro forma which included the author’s name, year of publication, type of study, geographical area, number of patients, clinical signs and symptoms, diagnostic tests performed, interventions and treatment outcomes.

Data analysis

The risk of bias (RoB) of included studies were assessed (KHP and JRF) using the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for case reports, case series and cohort studies [13, 14]. Disagreements between reviewers during study selection, data extraction and RoB assessment were resolved amongst themselves or involving the senior author (YZ). Only a qualitative synthesis of the included studies was possible due to the high heterogeneity of data and the small number of reports on HFS, which hindered any comparative quantitative analysis.

Results

Study selection and characteristics

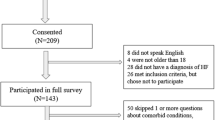

The study selection is summarised in the PRISMA flow chart (Fig. 1). The initial search identified 51 articles. After removing duplicates, 37 titles/abstracts were screened. Three congress abstracts were included from the first stage of screening and 5 studies were retrieved for full-text screening. Overall, 8 studies were included for data extraction [2, 4, 7,8,9, 15,16,17]. There were 2 retrospective studies [16, 17], 1 case series which included 4 patients [2], and 5 case reports [4, 7,8,9, 15], 1 of which included 2 patients [15].

Risk of bias assessment

The results of the RoB assessment of the included studies based on the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist are summarised in Supplementary Table 2. Most studies were case reports and 3 of the included studies were congress abstracts which resulted in a high risk of bias.

Results of individual studies

The study characteristics, and details on patients presenting signs and symptoms, investigations and treatments are summarised in Tables 1–3.

Gul and Serefoglu initially presented 2 cases in a congress abstract [3] and later updated their series to include 2 extra patients resulting in a 4-patient case series [2]. All 4 patients reporting a history of jelqing, aggressive masturbation or trauma during sexual intercourse. Investigations including a penile doppler were normal and all 4 patients were prescribed PDE5i (5 mg tadalafil or 50 mg sildenafil) to manage their symptoms and erectile dysfunction, but this provided temporary or no benefits. One patient received both tadalafil and 6 sessions of Li-SWT with initial relief, however symptoms recurred at 6 months [2].

Nico et al.’s patient was a 16-year-old who develop HFS following masturbation. He was successfully managed with physical therapy. However, the physical therapy protocol and follow-up were not reported [9].

Goldstein and Komisaruk reported a patient who had HFS secondary to a lumbar disc protrusion and was managed definitively with a discectomy. The patient initially presented 4 years prior and conservative treatment including sex therapy and pelvic floor physical therapy were unsuccessful. When the patient revealed a history of back pain and sciatica, a lumber MRI was performed which demonstrated a L5-S1 lumbar disc protrusion with annular tear. Epidural spinal injection provided transient improvement in HFS symptoms, but a L5-S1 lumbar endoscopic interlaminar discectomy provided significant improvement in his HFS symptoms [4]. In a subsequent abstract presentation, Goldstein et al. [16] assessed the prevalence of a lumbosacral annular tear in 21 men with HFS. Overall, 76% had an annular tear, with L5-S1 and L4-L5 being the most common location. In addition, 38% also had concomitant complaints of lower back pain and lower limb sciatica.

Billis et al. reported a more extensive diagnostic workup of a 30-year-old man with HFS secondary to intense sexual intercourse who had 85% symptom improvement at 3 months following biopsychosocial management [8]. The authors evaluated symptoms through validated questionnaires including the International Index for Erectile Function-5 (IIEF-5) and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) surveys. In addition, abdominal, pelvic floor and perineal muscles were assessed through external palpation and internal digital rectal examination. Pelvic floor muscle mobility was assessed by transabdominal ultrasound scan (USS). Daily 5 mg tadalafil was initiated together with 5 physical therapies, pain management and coping strategies, lifestyle and stress-release modifications. At 3 months, there were improvements in IIEF-5 and HADS scores and pelvic floor muscle mobility on USS. In addition, perineal and penile pain/stiffness were no longer present, however, the patient still had stress-related response issues and sexual performance anxiety [8].

The case with the longest follow-up was reported by Yazar et al. The 36-year-old patient was treated with trimodality therapy incorporating daily 5 mg tadalafil, 6 sessions of Li-SWT and 1–2 weekly physical therapy over 10–12 weeks. At 24 months, the patient remained symptoms free [7].

Pang et al. [15] presented 2 cases, both of which experienced some form of penile trauma either by aggressive masturbation, thread embedding acupuncture therapy (TEAT) or red light therapy (RLT). Similar to Billis et al., they used IIEF-5, HADS as well as erectile hardness score (EHS), International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) and the National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis Symptom (NIH-CPSI) survey to evaluate the patients’ symptoms. Blood tests and colour doppler ultrasound (CDUS) were normal. One patient had a nocturnal penile tumescence rigidity (NPTR) scan, which showed suboptimal erections. Both patients were offered anxiolytics, analgesia and tadalafil as required and patient-1 was on anti-depressants prescribed by his psychiatrist. At a follow-up of 1–2 months, both patients claimed that their symptoms improved. Moreover, patient-2 had vast improvements in his IPSS and NIH-CPSI scores (Table 3).

The erectile haemodynamics were evaluated in 88 patients with HFS by Sullivan et al. [17]. Seventy-five percentage (n = 66) of these patients also had a history of depression or anxiety and 45.5% (n = 40) were actively using anxiolytics or anti-depressants. On penile CDUS, all patients had normal peak systolic velocity (PSV), 2 (2.3%) patient had an abnormal end diastolic velocity (EDV) and no patient had elevated echogenicity on B-mode scanning.

Discussion

In this systematic review, we provided an update on the current clinical presentation and management of patients with HFS.

Clinical presentation

From the current systematic review, men diagnosed with HFS are aged between 16–42 years old. In the studies that reported potential aetiologies, all patients had a history of some form of trauma including aggressive masturbation, intense sexual intercourse, lumbar disc prolapse, annular tears, penile skin stretching/injury and possibly TEAT and RLT. It is evident that HFS associated symptoms varied across all patients and there was no standardised reporting of symptoms as demonstrated in Table 4. It is important to standardise reporting of symptoms in order for data to be compared in future studies to avoid heterogenicity. Since there are no agreed diagnostic criteria, it is appropriate to use the clinical features “list” described by Gul et al. as it represents the commonest symptoms identified from patient forums [1, 2, 18].

A survey distributed at the 2023 American Urological Association (AUA) meeting received 36 responses and nearly a third of participants had never seen HFS in their practice and about half of the respondents who had encountered HFS were confident in its legitimacy as a real medical syndrome. This survey highlighted the ongoing lack of familiarity [6].

HFS includes a cluster of symptoms reported by patients on the internet. The suggested diagnostic features were developed through the qualitative analysis of internet forum discussions on HFS [2, 18]. There are currently no objective tests to help diagnose HFS as the aetiology and pathophysiology is not entirely clear, and the diagnosis is mainly based on subjective symptoms review and exclusion of other pathologies through blood and radiological tests. A recent survey conducted by Niedenfuehr and Stevens on HFS distributed on social media platforms received 143 responses [10]. The mean age of the participants in the survey was 27.4 years confirming that HFS predominantly affects young men. The authors presented a more extensive list of symptoms compared to Gul et al.’s [2], and the most common symptoms (experienced by >65% of patients) were: changes in penis shape/size (92.3%), rigid penis when not erect (90.9%), psychological distress, anxiety and/or depression (89.5%), weak, tight and/or overactive pelvic muscles (85.3%), numbness/loss of sensation anywhere on the penis (74.8%), difficulty or inability to have an erection (74.1%), decreased force of urinary stream (72.7%), changes in dorsal vein size (71.8%), cold glans (66.7%) and loss of morning erections (66.2%) [10]. Since the most common symptoms apart from having a rigid penis when not erect were changes in penile shape/size and psychological symptoms, it is appropriate to include these 2 symptoms to Gul et al.’s [2] “list” as both of our patients had psychological distress, 1 of which also reported a change in penile size. In addition, in Sullivan et al.’s study 75% of patients had a history of depression or anxiety [17].

Aetiology and pathophysiology

The onset of symptoms was hypothesised to arise from some form of minor trauma [1, 2, 19]. However, in Niedenfuehr and Stevens HFS survey, 58% claimed that their HFS symptoms appeared following an incident or injury [10]. Therefore, HFS could possibly be idiopathic in origin. In Pang et al.’s [15] report, a patient received penile TEAT and both patients underwent RLT in the private sector for which the indication and therapeutic benefits were not entirely clear. TEAT involves inserting biodegradable sutures into acupoints, usually subcutaneously. It is practiced in Korean and Traditional Chinese Medicine with the aim to provide continuous stimulation of the acupoint avoiding regular acupuncture visits [20, 21]. Randomised-controlled trials have demonstrated that TEAT is effective in managing musculoskeletal pain such as osteoarthritic pain [22], or low back pain [23, 24] and abdominal obesity [25]. In addition, penile TEAT has been demonstrated to be effective in managing premature ejaculation [26]. However, there are currently no published clinical data on the role of TEAT in managing erectile dysfunction. In rat models with cavernous nerve injury, it has been shown that red-light controllable nitric oxide releaser, NORD-1 with red-light irradiation improved erectile function [27]. However, its role in human erectile dysfunction is unknown as there have been no clinical studies on human evaluating this.

The hypothesis on the aetiology and pathophysiology of HFS includes the initiation of inflammation following a trauma-like event involving the pudendal nerve and/or vasculature inducing neuropathy, penile hypoxia and muscle spasms. These muscle spasms may increase the intracavernosal pressuring during the flaccid phase of erection and inhibit optimal erection during the rigid phase, causing a hard-flaccid penis. In addition, the muscle spasms may also be associated with symptoms seen in chronic pelvic pain and primary prostatic pain syndromes. The neuropathy and penile hypoxia may cause the coldness and numbness in the glans and penile shaft reported by patients. The symptom complex may induce anxiety and distress and in turn worsen muscle spasms and symptoms resulting in a vicious circle between psychological ad HFS symptoms [1, 2, 18].

Interestingly, Goldstein and Komisaruk hypothesised that HFS is a result of pathological activation of a somato-visceral and/or a viscero-visceral reflex that they termed a “pelvic/pudendal-hypogastric” reflex [4]. This reflex may be pathologically activated via triggers located in 5 regions: (1) end organ (penis); (2) pelvis/perineum; (3) cauda equina; (4) spinal cord; (5) brain. Any insult at these levels, for example penile injury (e.g. aggressive masturbation) or pelvic/perineum injury would result in excess sympathetic activity and penile and pelvic/perineal symptoms respectively. Symptoms relief may be obtained by down-regulating the sympathetic drive, for example anti-inflammatory medications or Li-SWT for penile symptoms, and muscle-relaxants or pelvic floor physical therapy for pelvic/perineal symptoms [4]. In Goldstein and Komisaruk’s case, the patient had a disc prolapse resulting in injury in “region 3” and subsequent lumber discectomy resulted in significant relief of symptoms. Whilst this hypothesis is intriguing and logical, more research and patient cases are required to test this. In addition, Goldstein et al. identified that in 21 men with HFS and sacral radiculopathy, 16 (76%) had a surgically treatable annular tear [16]. Further follow-up regarding whether surgery was performed and whether symptoms resolved were unknown.

In Pang et al.’s [15] cases, psychotropic medications were given to both patients, and symptoms appeared to have improved, further suggesting a psychological component to HFS. In irritable bowel syndrome the gut-brain-axis represents a complex communication network between the gastrointestinal tract and the central nervous system. In individuals with irritable bowel syndrome, this system is believed to be dysregulated, resulting in atypical responses to stress, emotions, and gastrointestinal function [28]. Similarly, in the case of HFS, there may be a comparable “penis-brain-axis” involved in the manifestation of symptoms. However, this remains a hypothesis that requires further scientific investigation. Given the relatively mild degree of injury in these two patients, it cannot be ruled out that the trauma may have triggered the onset of HFS by inducing psychological abnormalities in individuals with an underlying psychological vulnerability.

Clinical assessment and investigations

Most studies in this review performed baseline bloods including hormonal profile to rule out organic cause of the patients’ erectile symptoms. In addition, most studies included at least an USS, not to diagnose HFS as such, but to rule out any abnormal blood flow or penile masses that may explain the patients’ penile symptoms. Therefore, in patients presenting with HFS, initial baseline blood tests and USS are suggested to exclude any differential diagnoses. Sullivan et al. reported that all patients in their study who had a penile CDUS, all had normal PSV and only 2 (2.4%) patient had an abnormal EDV [17].

Apart from identifying a list of signs and symptoms from patients’ history, evaluation of the degree and impact of symptoms through relevant questionnaires or scoring aids may be useful. Billis et al. used VAS, IIEF-5 and HAD questionnaires [8], and Pang et al. [15] used IIEF-5, EHS, VAS for pain, IPSS, NIH-CPSI and HADS. Using these questionnaires, it was evident that, patient 1 had more symptoms of higher severity compared with patient 2 in their report [15]. In addition, both patients claimed that their symptoms had significant impact on the quality of life (QoL) this suggested that the degree of impact on QoL may not necessarily correlate with the severity of symptoms [15].

Pang et al. [15] also utilised NPTR to objectively assess penile tumescence and rigidity. Although this test may not be readily available outside specialised centres and may offer limited diagnostic value, it can be useful for evaluating underlying psychogenic erectile dysfunction when no clear cause is identified through biochemical or radiological investigations. However, its accuracy can be influenced by the patient’s sleep state.

If patients present with HFS associated with back pain, sciatica or signs of radiculopathy, a lumber spine MRI may be required to rule out any spinal pathology as demonstrated in Goldstein at al’s reports [4, 16].

Management and outcomes

Various treatment and outcomes were identified in this review which included PDE5i, Li-SWT, physical therapy and lumber spine surgery. In the reported cases, only 2 (20%) patients were symptom free, 1 patient following physical therapy [9], and the other patient following trimodal therapy with PDE5i, Li-SWT and physical therapy [7]. It is likely that patients require multimodal therapy to target different physical symptoms accordingly as suggested by Goldstein and Komisaruk [4]. In addition psychotherapy or anxiolytics/anti-depressants should be consider appropriately to break the vicious cycle of HFS. Billis et al. used a combination of biopsychosocial therapy and their patient reported 85% improvement in symptoms [8]. In addition Pang et al. [15] also reported improvement in symptoms with both patients following a course of anti-depressants or anxiolytics.

In Niedenfuehr and Stevens’s survey, treatments patients received included PDE5i, pelvic floor physical therapy, SWT, diet/nutrition changes, nerve blocks, muscle relaxants, anti-inflammatory medications, cognitive therapy and nerve pain medications. No treatments provided significant improvements or complete cure. PDE5i was perceived the most efficacious, with patients reporting between “little” to “moderate” improvement. The other treatments provided “no” to “little” improvement. In addition, no patients were completely satisfied with any of the treatments and PDE5i received the highest satisfaction score (mean 4.8 on an 11-point slider scale) [10].

It appears that, most treatments do not provide complete cure, and patients are commonly not satisfied with the treatments they received. HFS is a complex disease to manage, and treatment would require multimodal therapy via a multidisciplinary approach and should be personalised according to the patient’s presenting symptoms. Treatments may not result in a cure unless the aetiological factor is eliminated, but more to relief symptoms and break the vicious cycle of HFS and may require coping mechanism to focus on factors that relieve symptoms and to avoid factors that exacerbate symptoms.

Limitations

The limitation of this systematic review is the small number of patients and heterogenicity in data reporting which restricted any quantitative analysis. However, HFS is extremely rare and may be under-diagnosed or reported by clinicians due to the unfamiliarity. Larger case series are required in the medical literature to allow continued education to improve familiarity of HFS, and in order to increase the case load enabling more meaningful analysis in the future.

Implications of results

This systematic review has highlighted the range of symptoms associated with HFS, the differences in clinical assessment tools used and the different treatment approaches. In addition, this review summarised the current hypothesis suggested by experts in the field. Due to the heterogenicity in data reporting, lack of clinical guidelines on diagnostic workup and management, and lack of familiarity in general amongst clinicians, it is imperative that an expert consensus recommendation on HFS is developed. In addition, apart from the clinical aspects, future research in the basic science of HFS may unravel molecular mechanisms associated with the pathophysiology of this syndrome, allowing the investigation into therapeutic agents.

Conclusion

The aetiopathophysiology of HFS is not entirely clear but involves complex neurovascular pathways. Investigations should aim at ruling out any sinister pathologies which may explain the patient’s symptoms. Treatment usually requires multimodal therapy targeting physical and psychological symptoms.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Gül M, Fode M, Urkmez A, Capogrosso P, Falcone M, Sarikaya S, et al. A clinical guide to rare male sexual disorders. Nat Rev Urol. 2024;21:35–49. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41585-023-00803-5.

Gul M, Towe M, Yafi FA, Serefoglu EC. Hard flaccid syndrome: initial report of four cases. Int J Impot Res. 2020;32:176–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41443-019-0133-Z.

Gül M, Serefoglu EC. PO-01-037 hard flaccid: is it a new syndrome? J Sex Med. 2019;16:S58. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JSXM.2019.03.194.

Goldstein I, Komisaruk BR. Hard flaccid syndrome proposed to be secondary to pathological activation of a pelvic/pudendal-hypogastric reflex. In: AUA News. American Urological Association; 2023. https://auanews.net/issues/articles/2023/may-2023/hard-flaccid-syndrome-proposed-to-be-secondary-to-pathological-activation-of-apelvic/pudendal-hypogastric-reflex.

Goldstein I, Komisaruk BR, Pukall CF, Kim NN, Goldstein AT, Goldstein SW, et al. International society for the study of women’s sexual health (ISSWSH) review of epidemiology and pathophysiology, and a consensus nomenclature and process of care for the management of persistent genital arousal disorder/genito-pelvic dysesthesia (PGAD/GPD). J Sex Med. 2021;18:665–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JSXM.2021.01.172.

Gryzinski G, Hammad MM, Alzweri L, Azad B, Barham D, Lumbiganon S, et al. Hard-Flaccid syndrome: a survey of sexual medicine practitioners’ knowledge and experience. Int J Impot Res 2024. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41443-024-00917-3.

Yazar RO, Hammad MAM, Barham DW, Azad B, Yafi FA. Successful treatment of hard flaccid syndrome with multimodal therapy: a case report study. Int J Impot Res 2024. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41443-024-00955-X.

Billis E, Kontogiannis S, Tsounakos S, Konstantinidou E, Giannitsas K Hard flaccid syndrome: a biopsychosocial management approach with emphasis on pain management, exercise therapy and education. Healthcare 2023;11:2793. https://doi.org/10.3390/HEALTHCARE11202793.

Nico E, Rubin R, Trosch L. Successful treatment of hard flaccid syndrome: a case report. J Sex Med. 2022;19:S103. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JSXM.2022.01.218.

Niedenfuehr J, Stevens DM. Hard flaccid syndrome symptoms, comorbidities, and self-reported efficacy and satisfaction of treatments: a cross-sectional survey. Int J Impot Res. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41443-024-00853-2.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71.

Brown D. A review of the PubMed PICO tool: using evidence-based practice in health education. Health Promot Pract. 2020;21:496–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839919893361.

Munn Z, Barker TH, Moola S, Tufanaru C, Stern C, McArthur A, et al. Methodological quality of case series studies: an introduction to the JBI critical appraisal tool. JBI Evid Synth. 2020;18:2127–33. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBISRIR-D-19-00099.

Aromataris E, Lockwood C, Porritt K, Pilla B, Jordan Z. JBI manual for evidence synthesis. JBI; 2024. https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL.

Pang KH, Feng J, Zhang Y. Hard-flaccid syndrome: a report of two cases. Int J Impot Res. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41443-025-01058-X.

Goldstein I, Komisaruk B, Goldstein S, Yee A. (149) Prevalence of lumbosacral annular tears in individuals with hard flaccid syndrome. J Sex Med. 2024;21. https://doi.org/10.1093/JSXMED/QDAE001.140.

Sullivan J, Salter C, Flores J, Guhring P, Parker M, Mulhall J. MP21-20 exploring erectile hemodynamics in men complaining of hard-flaccid syndrome (HFS). J Urol. 2022;207. https://doi.org/10.1097/JU.0000000000002554.20.

Gul M, Huynh LM, El-Khatib FM, Yafi FA, Serefoglu EC. A qualitative analysis of internet forum discussions on hard flaccid syndrome. Int J Impot Res. 2020;32:503–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41443-019-0151-X.

Abdessater M, Kanbar A, Akakpo W, Beley S. Hard flaccid syndrome: state of current knowledge. Basic Clin Androl. 2020;30:7. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12610-020-00105-5.

Huang JJ, Liang JQ, Xu XK, Xu YX, Chen GZ. Safety of thread embedding acupuncture therapy: a systematic review. Chin J Integr Med. 2021;27:947–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11655-021-3443-1.

Woo Y, Kwon BI, Lee DH, Kim Y, Suh JW, Goo B, et al. Appraising the safety and reporting quality of thread-embedding acupuncture: a protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e063927. https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJOPEN-2022-063927.

Woo SH, Lee HJ, Park YK, Han J, Kim JS, Lee JH, et al. Efficacy and safety of thread embedding acupuncture for knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Medicine. 2022;101:E29306. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000029306.

Lee HJ, Choi B, Il, Jun S, Park MS, Oh SJ, Lee JH, et al. Efficacy and safety of thread embedding acupuncture for chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Trials. 2018;19:680. https://doi.org/10.1186/S13063-018-3049-X.

Goo B, Kim JH, Kim EJ, Lee HJ, Kim JS, Nam D, et al. Thread embedding acupuncture for herniated intervertebral disc of the lumbar spine: a multicenter, randomized, patient-assessor-blinded, controlled, parallel, clinical trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2022;46:101538. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CTCP.2022.101538.

Ye W, Xing J, Yu Z, Hu X, Zhao Y. Systematic review and meta-analysis of acupuncture and acupoint catgut embedding for the treatment of abdominal obesity. J Tradit Chin Med. 2022;42:848–57. https://doi.org/10.19852/J.CNKI.JTCM.2022.06.002.

Gong W, Gao Q, Xu Z, Dai Y. Advances in the surgical treatment of premature ejaculation. National Journal of Andrology. 2018;24:346–69.

Mori T, Hotta Y, Ieda N, Kataoka T, Nakagawa H, Kimura K. Efficacy of a red-light controllable nitric oxide releaser for neurogenic erectile dysfunction: a study using a rat model of cavernous nerve injury. World J Mens Health. 2023;41:909–19. https://doi.org/10.5534/WJMH.220146.

Pellissier S, Bonaz B. The place of stress and emotions in the irritable bowel syndrome. Vitam Horm. 2017;103:327–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/BS.VH.2016.09.005.

Acknowledgements

YZ acknowledges support from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFC2702703) and the Key Laboratory of Male Reproduction and Genetics, National Health and Wellness Committee, Open Project, Exploration on the Construction of Diagnosis and Treatment System for Azoospermia with Unilateral Scrotum Touching vas deferens (KF202002).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and/or designed the work that led to the submission: KHP, YZ. Acquired data, and/or played an important role in interpreting the results: KHP, JRF, YZ. Drafted or revised the manuscript: KHP, JRF, YZ. Approved the final version: KHP, JRF, YZ. Agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved: KHP, JRF, YZ.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pang, K.H., Feng, J. & Zhang, Y. Hard-flaccid syndrome: a systematic review of aetiopathophysiology, clinical presentation and management. Int J Impot Res (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41443-025-01118-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41443-025-01118-2