Abstract

Gangliosides in the brain play a crucial role in modulating the integrity of vertebrate central nervous system in a region-specific manner. However, to date, a comprehensive structural elucidation of complex intact ganglioside isomers has not been achieved, resulting in the elusiveness into related molecular mechanism. Here, we present a glycolipidomic approach for isomer-specific and brain region-specific profiling of the mouse brain. Considerable region-specificity and commonality in specific group of regions are highlighted. Notably, we observe a similarity in the abundance of major isomers, GD1a and GD1b, within certain regions, which provides significant biological implications with interpretation through the lens of a theoretical retrosynthetic state-transition network. Furthermore, A glycocentric-omics approaches using gangliosides and N-glycans reveal a remarkable convergence in spatial dynamics, providing valuable insight into molecular interaction network. Collectively, this study uncovers the spatial dynamics of intact glyco-conjugates in the brain, which are relevant to regional function and accelerates the discovery of potential therapeutic targets for brain diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gangliosides, a subtype of glycosphingolipids, are composed of a hydrophilic glycan chain that contains sialic acid and a hydrophobic ceramide moiety, making them the most complex and diverse lipid species1. Importantly, gangliosides, highly concentrated in the neural tissue, account for over 10% of the total brain lipids2. They play an essential role in neurophysiology, including synaptic plasticity3,4,5, brain development6, nerve formation and transmission7,8, and memory formation9,10. Inevitably, gangliosides are intimately associated with brain disorders such as neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease11,12,13,14. The significance of ganglioside isomers in neuro-diseases has garnered wide attention from scientists15. In particular, the positional isomers are very important in neurodegenerative diseases, mounting evidence suggested that the disease could dictate the different quantitative changes in GD1a and GD1b isomers, as exemplified by Parkinson’s Disease16. While the isomer-specific elucidation of ganglioside structure is imperative, uncovering their spatial distribution is equally crucial. Over the years, several papers have highlighted that gangliosides are not uniformly distributed across different brain regions. Their distribution varies uniquely from one region to another. Furthermore, the alteration in their distribution is influenced by the presence of diseases, showing a disease-specific topographical dependence. For instance, the concentration of GD1a/GD1b isomers changes in a region-specific manner in Alzheimer’s disease17,18,19 and multiple sclerosis20. These findings imply the existence of distinctive characteristics among ganglioside isomers in various brain regions, which could be linked to specific brain functions and the onset of pathological conditions.

To probe the complex structural and functional organization of the mammalian central nervous system, comprehensive and systemic approaches are required. Large-scale initiatives of genome, proteome, glycome, and metabolome have been launched to establish functionally informative connectomes and develop global simulations of the brain21,22,23,24,25,26. However, despite gangliosides being key functional components in neuronal cells, the spatial distribution and biological function remain limited due to a lack of sensitive analytical methods for the detection, identification, and quantification of brain gangliosides at the molecular level. Previous studies mainly utilized chemical and immunohistochemical methods, which only provide partial information on glycan or ceramide portion27,28,29,30. Mass spectrometry has emerged as a powerful tool, revealing remarkably subtle molecular distributions of gangliosides as well as structural variants that may result from the headgroup and the lipid tail simultaneously31,32. In addition to various LC–MS-based approaches, methods such as direct infusion shotgun mass spectrometry, GC-MS, and CGE-LIF have been employed to separate ceramides and headgroups. These methods achieve high sensitivity and allow for the analysis of ganglioside headgroup isomers33. Recent developments in mass spectrometry, such as modified composition of LC solvent and the use of ion mobility spectrometry, have greatly been able to facilitate effective differentiation of glycosphingolipid isomers34,35. Yet, no gold-standard analytical method has been established for a comprehensive structural elucidation of complex gangliosides. In particular, insufficient tools for isomer distinction could lead to a lack of accuracy in assignments of gangliosides from complicated samples such as various biological sources36.

Herein, we report the identification of ganglioside in an isomer-specific manner across various regions of mouse brain tissue, including the cerebral cortex, prefrontal cortex (PFC), striatum, hippocampus, olfactory bulb, diencephalon, midbrain pons-medulla, cerebellum based on ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography-quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (UPLC-Q-TOF MS). Using a powerful analytical platform optimized with the addition of formic acid in the LC mobile phase, ganglioside isomers of GD1a and GD1b were completely separated on a reverse phase column system, and structures of the separated ganglioside isomers, including ceramide information, were further confirmed by MS/MS. Another advantage of the addition of formic acid to the aqueous phase is that the peak retention time (RT) of each analyte was shortened, and the peak shape became narrower, suggesting that the addition of formic acid improved the ionization efficiency and enhanced the signal response35. In addition, a mathematical equation based on the logarithmic relationship between the ceramide carbon number and RTs enabled the prediction of theoretically possible gangliosides. Via the obtained information on ganglioside isomers, a theoretical retrosynthetic state-transition network was proposed, which provides useful information on the pathway, including the type of branching by the differentiation of a- and b-series. Furthermore, importantly, although glycan synthesis and degradation or the expression levels of related enzymes were not directly specified in this study, this theoretical network framework provides hints at region specificity within a series of biological systems related to the ganglioside biosynthetic connectivity. By expanding our investigation to encompass N-glycan distribution in nine distinct brain regions of mice prepared under identical conditions, we present the data at the phenotype level, indicating a close association between the spatial distribution of gangliosides and N-glycans in the brain. These findings contribute to the understanding of glycosphingolipid functions and associated molecular mechanisms, particularly those involving glycan, in relation to brain region specificity and function. The implications of our discoveries hold promise for inspiring future research endeavors in this domain.

Results

To examine brain ganglioside diversity across different brain regions, a total of 36 mice brain samples were collected from four adult male mice, encompassing nine corresponding brain areas. A streamlined workflow for the study of brain gangliosides is illustrated in Fig. 1.

a Brain tissue preparation. Multiple regions of the mouse brain were dissected, and following tissue homogenization, gangliosides were enriched using a modified Folch method and C18 Solid Phase Extraction (SPE). CB cerebellum, CC cerebral cortex, DC diencephalon, Hip hippocampus, MB midbrain, OB olfactory bulb, PFC prefrontal cortex, P-M pons-medulla, ST striatum. b LC–MS/MS Data Acquisition. Ganglioside isomers were separated, and the obtained qualitative and quantitative data were subjected to a bioinformatic approach for comparative regional profiling. c Biological interpretation. Integration of biosynthesis pathways and a glyco-centric approach was performed to garner the functional roles of gangliosides in neurological processes. Some elements in this figure were created with BioRender.com, released under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Structural identification of mouse brain gangliosides via MS/MS and RT prediction

The structural investigation of gangliosides has been particularly challenging due to the diversity and complexity of their structures. Here, we employed a combination of column RT, exact mass value, and MS/MS analysis to determine and identify the structure of the gangliosides, including both glycan and ceramide moieties. To achieve efficient resolution, chromatographic separation, and ionization for mass spectrometry of complex amphipathic gangliosides, we employed strategically balanced proportions of organic solvents. First, a streamlined workflow based on the positive-ion detection mode with a UHPLC Q-TOF MS was optimized using porcine brain gangliosides as a standard. The separation of gangliosides was based on their ceramide portion on a reverse phase C18 column. To further characterize the heterogeneity of brain gangliosides with different glycan headgroups, we introduced formic acid to the mobile phase, allowing the separation of isomers35. Finally, the separated ganglioside isomers were identified and structurally elucidated by diagnostic fragment ions obtained through tandem MS. See Methods for details of experimental conditions.

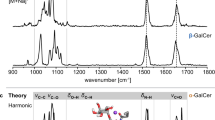

Figure 2 illustrates the identification of mouse brain gangliosides by comparing the LC RTs and tandem MS spectra of porcine brain gangliosides. Under optimized analytical conditions, gangliosides including GM1a 36:1;O2, GD1a 36:1;O2, GD1b 36:1;O2, GT1 36:1;O2 and GQ1 36:1;O2 from porcine brain and mouse brain were effectively separated and structurally elucidated. Notably, identical fragment pattern with diagnostic fragment ions was obtained, irrespective of the sample origin, highlighting the reliability of our approach. The positive-ion detection mode MS/MS provided comprehensive structural information, allowing for the interpretation of both ceramide and glycan moiety, respectively. In specific, the diagnostic ions such as m/z 292.11 (NeuAc1, [M + H]+) and m/z 657.25 (Gal1GalNAc1NeuAc1, [M + H]+) confirmed the presence of sialic acid37. The isomeric structure of GM1a was stipulated through the ion of m/z 1181.78 (Cer-Glc1Gal1NeuAc1, [M + H]+) (Supplementary Fig. 1a, b). For the major ganglioside isomers of GD1a and GD1b, baseline separation was achieved, enabling their identification. Interestingly, the definite diagnostic fragment ion of two coupled sialic acids corresponding to NeuAc2 (m/z 583.21, [M + H]+) was observed only in the GD1b isomer structure (Fig. 2a, b). In the case of GT1 and GQ1, we were only able to narrow down the identification of peaks as b- or c-series isomer since fragment ion of NeuAc2 (m/z 583.21, [M + H]+) was commonly obtained for both gangliosides. A diagnostic peak such as oligomer fragment peak of NeuAc3 (m/z 874.29, [M + H]+) to distinguish as c-series isomer was not observed. However, taking into account previous reports indicating that brain gangliosides in adult mammals are predominantly composed of five closely related structures (GM1, GD1a, GD1b, GT1b, and GQ1b) which account for the majority (97%)38,39, the candidate could be inferred to the b-series isomer (Supplementary Fig. 1c–f).

a, b Representative EICs and CID-MS/MS spectra of GD1a 36:1;O2 and GD1b 36:1;O2 from porcine and mouse brains, respectively. c Representative EIC of GQ1c 36:1;O2 with 2 O-acetylation from porcine and mouse brain. d CID-MS/MS spectra of GQ1c 36:1;O2 with 2 O-acetylation from mouse brain were shown. Diagnostic ions were highlighted with red asterisks. Monosaccharide legend: blue circle-Glucose, yellow circle-Galactose, Yellow square-N-acetylgalactosamine, Purple diamond-N-acetylneuraminic acid, Red triangle-Fucose. The ceramide tail was indicated by ‘Cer’. Some elements in this figure were created with BioRender.com, released under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

In particular, O-acetylation of sialic acid is recognized as one of the most common and important covalent modifications of gangliosides, which considerably influences their physiological properties such as protection against sialidase, development, tumor progression, and pathogen binding40,41,42,43. In Fig. 2c, the representative tandem MS spectrum illustrates O-acetylated NeuAc at m/z 334.09 [M + H]+ consisting of (NeuAc1 + OAc1) and m/z 625.16 [M + H]+ consisting of (NeuAc2 + OAc1). Unique fragment ions at m/z 667.17 (NeuAc2 + OAc2, [M + H]+) and m/z 1938.50 (Glc1Gal1NeuAc3GalNAc1Gal1NeuAc1 + OAc2, [M + H]+) indicate the presence of two O-acetylated NeuAc residues. As a result, we successfully obtained information on the structures of various types of brain gangliosides, including those with O-acetylation modifications, through tandem MS. Notably, this approach provided structural insights not only into the glycan chain but also into the ceramide portion, encompassing the fatty acyl chain and sphingoid base. As shown in Fig. 2, fragments of ceramide moieties (m/z 566.51 corresponding to [36:1;O2]) were apparently obtained.

The regularity in the order of RT on the reverse phase column was further examined to enhance the identification of brain ganglioside, including minor ones at low concentrations where reliable evidence from tandem MS for identification is often not available. We developed a mathematical model aimed at providing valuable information for identification and predicting the RT of unknown gangliosides from complex samples44. The correlation between RTs with the number of sialic acids in the glycan moiety, the number of double bonds, and the number of carbons in the ceramide moiety was identified. This correlation is exemplified by GT1-related compounds, which were highly expressed in mouse brains (Supplementary Fig. 2). Gangliosides having a higher degree of sialic acid with identical ceramide moiety (36:1;O2) were early eluted (Supplementary Fig. 2a), with the RT difference between neighboring glycans differing in a NeuAc ranging from 0.4 min to 0.9 min. In addition, as the number of double bonds increased, gangliosides with the same number of carbons and glycan moiety were early eluted (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Lastly, Supplementary Fig. 2c shows that with the elongation of the number of carbon in ceramide, the RT increased on average by 1.59 min. Based on the correlations elaborated above, a mathematic model was established to predict the RT of the ganglioside based on the number of ceramide carbons (refer to Supplementary Fig. 2d for GT1-related compounds and Supplementary Fig. 3 for total equations from the porcine brain standard). A strong positive correlation between the number of ceramide carbons and RT in the gangliosides on the reversed-phase system was obtained. In Supplementary Data 1, the predicted retention time (pRT) was calculated as the sequential product of the calculated relative RT and relative retention time (rRT) by considering the reference compound (RT = 9.112 in this GT1 36:1;O2) The resulting error values indicated that the pRTs of all ganglioside compounds obtained from the mathematical models matched well with their rRTs. Finally, a total of 94 gangliosides identified in porcine brain gangliosides standard by MS tandem confirmation and RT prediction approach were listed in Supplementary Data 2. For minor brain gangliosides without MS/MS spectrum, a mathematical model was established on the basis of a logarithmic relationship to predict the RTs of all theoretically possible gangliosides. Through prerequisite analysis of the characteristics of ganglioside compounds identified from porcine brain ganglioside standard materials, we found a total of 83 different ganglioside structures, including 17 predicted gangliosides in mouse brain samples across all 9 brain regions (refer to Supplementary Data 3 for the full list of gangliosides identified by MS tandem confirmation and RT prediction approach).

Decoding ganglioside profiles and their connection to brain regions

Interestingly, we observed both qualitative and quantitative conservation and divergence in the elution behavior of chromatograms of gangliosides across various regions of the mouse brain. Supplementary Fig. 4 shows the representative total compound chromatograms of gangliosides from 9 brain regions. Notably, GT1 36:1;O2 (9.164 min) consistently presented the biggest chromatogram in all brain regions, indicating its prevalence. Meanwhile, spatial differences were apparent, leading to the categorization into two groups with high intragroup similarity: Group I (PFC, OB, and CB) and Group II (CC, ST, Hip, DC, MB, and P-M), as exemplified by the area of separated chromatograms of GD1 36:1;O2 isomers. The ratio of early-eluting GD1a 36:1;O2 to late-eluting GD1b 36:1;O2 was lower in Group I, while vice versa for Group II. Furthermore, based on the GT1 36:1;O2, the higher ratio of major early-eluting species with greater acidity, GQ1 (with or without O-acetylation) which contains the highest degree of NeuAc linked to an identical ceramide portion, was observed in Group I compared to Group II. On the other hand, the major late-eluting species in Group I were biosynthetically more advanced gangliosides with sialic acid (with or without O-acetylation), such as GT1 and GQ1, whereas GM1 or minor GT1 predominated in Group II.

To comprehensively understand ganglioside profiles, we compared the identification data against a plot of each ganglioside composition versus its frequency (occurrence) of detection. We quantified the normalized abundance of 83 individual gangliosides in quadruplicates by chromatographic peak area for quantitative inspection of ganglioside from each brain region (see Fig. 3, and Supplementary Data 4 for the full list of gangliosides and their abundances). Despite variations in the identified gangliosides, from 55 in the OB to 90 in the PFC as shown in Fig. 3b, a core set of 43 gangliosides representing 95.07% to 97.66% (normalized absolute peak intensity, NAPI) was consistently detected in all 9 mouse brain regions. This core set is highlighted with the dotted black box in Fig. 3a. Among these, 13 gangliosides with mono-, di-, tri-, and tetra-sialylated glyco-portions, featuring 36- and 38-carbon ceramides with a single double bond, were consistently observed in all 36 samples, regardless of individual or spatial variations. The distinctive characteristics of glyco- and ceramide portions in these 13 gangliosides are the primary contributors to the overall distribution of total gangliosides, as illustrated in Fig. 3c, d, respectively.

a Frequency of detection of gangliosides compositions in mass profiles across different regions. Dotted black boxes highlight the gangliosides observed in all regions. Gangliosides shown with 100% frequency are indicated in gray. b Comparative analysis of the number of identified gangliosides across 9 brain regions. The values within the heatmap indicate the count of gangliosides observed in both brain regions and the quantitative percentage of these gangliosides relative to the total gangliosides. c, d Normalized absolute peak intensities (NAPIs) of gangliosides according to glycan and ceramide moieties in each brain region. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Through univariate analysis using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), we identified 58 altered gangliosides across all brain region groups (Supplementary Fig. 4). These gangliosides were then plotted as clusters in a heat map to investigate statistical variations and similarities among individual samples (Fig. 4a). Notably, all samples were clustered well with their replicates, showcasing region-specific ganglioside expression patterns. The chromatographic differences between Group I (PFC, OB, and CB) and Group II (CC, ST, Hip, DC, MB, and P-M) eventually led to a distinct division into two major clusters. Interestingly, biosynthetically ganglioside compositions relevant to biosynthesis segregated into nine cluster groups, as observed on the y axis to the left side in Fig. 4a. In particular, there was a strong tendency for a- or b-series gangliosides to cluster separately, resulting in homogeneous clusters of and a-series species (Cluster VI and VII) and b-series species (Cluster I, III, IV, and VIII).

a A heat map for the hierarchical clustering of gangliosides for nine mouse brain regions from four mice. The scale bar indicates z-scores of standardized ganglioside values, with high and low ganglioside expression shown in red and blue, respectively. Rows indicate clusters of 58 significantly different gangliosides by brain regions (P < 0.001, two-sided one-way ANOVA), with a-series gangliosides marked by solid black bar and b-series by a diagonal-fill pattern. The left side of the rows indicates the nine sub-clusters of gangliosides. b, c The radar chart displays the distribution of glycan and ceramide portion across the 9 brain region, respectively. The scale bar for Pearson’s r values for each region is located below the radar chart. d, f partial least squares-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) of 9 brain regions based on the relative abundances of total gangliosides with its 2-D indication. e, g Glycan portion and ceramide portion according to loading 1 values of PLS-DA, respectively. The variables are ranked by the absolute values of their loadings. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Gangliosides paly a variety of functions and pathophysiological roles ranges from regulating receptor tyrosine kinases to facilitating cell–cell recognition governed by both glycan and ceramide moieties45. Therefore, we reorganized the data to simultaneously measure glycan and ceramide moieties using our optimized analytical method, aiming to determine independent correlation with region specificity (Fig. 4b, c for NAPI of glycan and ceramide portion, respectively). Interestingly, the similarity between each sample was lower in the glycan moiety (Pearson’s r = 0.45–0.99, Fig. 4b, left) compared to the ceramide moiety (Pearson’s r = 0.69–0.99, Fig. 4c, right). This suggests that the glycan moiety exhibited greater heterogeneity than the ceramide moiety depending on brain regional variation (Please refer to Supplementary Fig. 5 for detailed value for Pearson’s r). As shown in Fig. 4b, the main gangliosides were GM1, GD1, GT1, and GQ1 accounting for 91.08–97.82% of the total in every region. The remaining brain components consisted of minor gangliosides such as lactosyl series gangliosides, GM3 (sialyllactosylceramide), GD3, GM2, with proportions varying across species from 1.96% (PFC) to 8.05% (CC).

Particularly, GT1 was the most abundant, averaging 51.06% in all regions except OB, where GQ1 was the most dominant species (47.86%). This observation is consistent with previous findings that ganglioside profile in the rodent brain is dominated by simpler species (GM3 and GD3) at early developmental stages and then their expression is down-regulated with concomitant up-regulation of complex species, remaining relatively constant during adulthood46. Additionally, the concentration of GD, which is highly present in the embryonic brain is known to rapidly reduce after birth47. Analysis of Fig. 4b, moving clockwise from the top of the radar chart, allows for a comparison between the simpler/fewer sialic acid (a-series) and complex/more sialic acid (b-series) gangliosides on the right and left sides of the chart, respectively. Specifically, Group I (PFC, OB, CB) and ST showed relatively low levels of GD1, a major component of a-series. Continuing from the bottom and up the left side of chart, more striking differences become apparent. GQ1, which is biosynthetically highly processed species in b-series showed a higher portion in Group I (PFC, OB, CB) and ST accounting for more than 20%. According to the characteristic variations of GD1, GT1, and GQ1, the regions in Group I exhibited a clear segregation in the score plot of partial least squares-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) (component 1 = 51%, Fig. 4d, e). Regarding the ceramide moiety, most gangliosides in every brain region predominantly carry 36- and 38- carbon ceramides, where ceramide 36:1;O2 is the most dominant accounting for over 50% in common. However, long-chain ceramide(38:1;O2) was more common in Group I than in Group II (Fig. 4c). Despite some overlaps, PLS-DA (component 1 = 97.6%, Fig. 4f, g) showed a clear clustering of Group I and II. These results finally demonstrated that both glycan and ceramide moieties in gangliosides are closely associated with brain regional specificity. For an in-depth characterization of the biological relevance of region-specific gangliosides, 58 statistically significant mouse brain gangliosides (P < 0.001, ANOVA) were further examined using Pearson’s correlation. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 6, exhibiting only strong correlations (Pearson’s r > 0.5), nine main clusters of mouse brain gangliosides were significantly associated with regional differences. Gangliosides from the same origin, a- or b-series tend to cluster together, demonstrating positive correlations (see y axis of right side). Meanwhile, negative correlations are observed between a- and b-series originated ganglioside as marked with X in Supplementary Fig. 6.

Retrosynthetic ganglioside network: region specificity and commonalities in gangliosides across diverse brain regions

To gain deeper insights into the region-specific implications within the context of synthetic connectivity and to identify common patterns across diverse brain regions, we reconstituted the region-specific retrosynthetic ganglioside network48. This reconstruction was based on both quantitative and qualitative data regarding ganglioside isomers from nine distinct brain regions (Fig. 5). The resulting map, showing the biological interconnections among brain gangliosides, not only integrates individual ganglioside findings but also provides biological plausibility to the context of biosynthesis. Indeed, all depicted glycan moieties in the map including four major compounds, GM1, GD1, GT1 and GQ1, were intricately linked to each other, implying that gangliosides in the regional mouse brain primarily follow the a-, b-series. As illustrated in the map, two main pathways in mammalian brain designated a-series (GM2, GM1a, GD1a, GT1a) and b-series (GD3, GD2, GD1b, GT1b, GQ1b) go through stepwise glycosylation starting from GM3, a common precursor derived from lactosylceramide49. Remarkably, the isomers, GD1a and GD1b both featuring the most abundant ceramide moiety 36:1;O2, were distinctly quantified across various brain regions. (Fig. 5b). Specifically, Group I (PFC, OB, and CB) highlighted with the blue boxes showed a higher abundance of GD1b, whereas GD1a was more prevalent in Group II (CC, ST, Hip, DC, MB, and P-M) indicated by the red boxes. Note that Group I regions exhibited a relatively high quantification of GQ1 which contains multiple sialic acid residues, resulting in separating the group as evident clusters in PLS-DA analysis (Fig. 4c, d).

a Regional differentiation of ganglioside isomer distribution, GD1a and GD1b on a 36:1;O2 ceramide base. Values are represented as normalized mean abundances ± SD (n = 4 biological replicates). b The proposed region-specific retrosynthetic network of gangliosides in nine mouse brain regions based on isomer-specific ganglioside analyses. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Comparative assessment of N-glycans and gangliosides: commonality in regional divergence

Researchers have significantly advanced our understanding of how N-glycosylation reactions influence the biology of glycolipids and glycoproteins50,51,52. Particularly, N-glycosylation and subsequent trimming by glucosidases I and II are reported to critically affect the glycolipid biosynthesis such as the subcellular localization and stability of glycosyltransferase complex including GD3 synthase and GM1/GD1a synthase53. However, the detailed molecular mechanisms by which N-glycan and glycosyltransferases contribute to ganglioside metabolism remain unclear. This includes how switch a- to b-series gangliosides and even whether N-glycans are important for the pathway process as well as functional roles of pathway switch in brain.

Here, we performed the first parallel inspection of region specificity in N-glycans and gangliosides using identical regional mouse brain samples. To determine how the interdependence is observed in our spatially resolved datasets of N-glycan and ganglioside phenotypes, we further performed comparative analysis of both molecules using identical set of mouse brain regional samples. As shown in Fig. 6, the Pearson’s correlation using the statistically significant 58 gangliosides and 73 N-glycans revealed that gangliosides (r = 0.605−0.990) exhibit greater interregional heterogeneity compared to N-glycans (r = 0.874−0.992) (Fig. 6a). Notably, we could identify some similarities in the regional variation between gangliosides and N-glycans. The PFC (r = 0.794−0.969 and r = 0.874−0.964 for gangliosides and glycans, respectively) and OB (r = 0.605−0.843 and r = 0.930−0.983 for gangliosides and glycans, respectively) were the most heterogeneous regions for both molecules, which showed little correlation with other regions. Conversely, the other 7 regions showed relatively greater similarity between them. (r = 0.849−0.990 and r = 0.955−0.992 for gangliosides and glycans, respectively). Especially, 9 brain regions could be discriminated into two groups for both molecules, Group I (PFC, OB, and CB) and Group II (CC, ST, Hip, DC, MB, and P-M) (Fig. 6b, c for PLS-DA using ganglioside data and sPLS-DA using N-glycan data, respectively).

a, b Two-sided Pearson correlation analyses using NAPI values of statistically significant gangliosides (a) and N-glycans (b) across samples from 9 mouse brain regions (p < 0.001, two-sided one-way ANOVA). The brain regions with the highest and lowest correlations for each of the 9 brain areas are indicated by their corresponding heatmap colors on the brain illustration. c PLS-DA score plots of mouse brain samples by gangliosides across nine brain regions. d, e Gangliosides according to loading 1 (d) and loading 2 (e) values in the PLS-DA. f sPLS-DA score plots of mouse brain samples by N-glycans across nine brain regions. g, h N-glycan species according to loading 1 (g) and loading 2 (h) values in the sPLS-DA. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Our findings highlighted a significant correlation between specific gangliosides and N-glycans, which is consistent with previous studies on the interdependence of these two molecules. This correlation also aligns with the regional segregation trend shown in Fig. 6b, c. For example, the inhibition of N-glycan trimming by glucosidases I and II in mouse and human embryonic brain dramatically alters ganglioside composition by inhibiting synthesis of highly sialylated and complex b-series gangliosides at the time point of proliferation and migration of neural progenitor and intermediate neuron54. On the other hand, a decrease in mature-type core α1,3-fucosylated N-glycans and an increase in unusual N-glycans with terminal fucosylated hexose structure were observed in Caenorhabditis elegans in which α-glucosidase I gene that encodes a polypeptide with 36% identity to human α-glucosidase I was knocked down by RNAi55. In a similar vein, our dataset showed that less sialylated and a-series gangliosides (GM3 36:1;O2 and GD1a 36:1;O2) were significantly low in Group I, while species with higher degree of sialylation (GT1 38:1;O2 with mono-/di-O-acetylation and GQ1 38:1;O2 without or with mono-/di-O-acetylation) were abundant (Fig. 6b). Additionally, we observed an increase in a N-glycan having core fucose residue (Hex3HexNAc6Fuc1) and a decrease in species with fucosylated hexose in Lewis Y(B) epitope (Hex5HexNAc4Fuc3 and Hex5HexNAc5Fuc3) in Group I (Fig. 6c). These findings demonstrate a significant convergence in the spatial dynamics of N-glycans and gangliosides across the brain56,57,58. Our study is the first to examine the relationship between these two molecules at both molecular and phenotype levels across the nine brain regions, offering a comprehensive perspective on the entire molecular profile within the central nervous system. This approach not only confirms the intricate relationship between N-glycans and gangliosides but also sets the stage for future research to further understand their complex interactions.

Discussion

Gangliosides play a pivotal role in neural development, synaptic plasticity, and signaling within the mammalian brain. Their involvement in neurological disorders further underscores their significance59. Despite this importance, comprehensive regional mapping of brain gangliosides has faced analytical challenges, including structural diversity, that have limited the sensitivity and specificity of methods for the separation, detection, and quantification of these complex gangliosides in the brain. In addition, the analysis and interpretation of ganglioside data have been hampered by a lack of databases and computational tools. The glycan portion in gangliosides exhibits a high degree of structural heterogeneity due to variations in monosaccharide sequence, linkage, anomericity, and branching. This complexity is further compounded by modifications such as sulfation, phosphorylation, and acetylation60. Here, we address these challenges by establishing a comprehensive analytical platform for the analysis of mammalian brain gangliosides with the creation of the adult mouse brain region-specific and isomer-specific reference library. Our approach, distinct from previous studies that predominantly utilized antibody-based tools focusing on glycan portions, provides a detailed profile of individual gangliosides at the isomer level. This method encompasses both the glycan head and ceramide moiety in a single analysis, overcoming traditional hurdles in isomer separation61. Using this platform, we analyzed gangliosides from nine different brain regions of 10-week-old mice as a model, uncovering the correlation between the spatial distribution of gangliosides and brain function in normal adult brains.

We observed a notable distinction in the similarity between different brain regions, with lower similarity in the glycan moiety and higher in the ceramide moiety, as depicted in Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 5. This suggests greater heterogeneity in the glycan moiety, potentially being closely associated with region-specific brain function. Our findings align with the established knowledge that much of the biological function of ganglioside is determined by their glycan headgroups62. We also examined consistency in brain region-specific glycan isomer distribution, aligning with prior research that employed quantitative profiling of intact gangliosides. In detail, high expression of GD1a was observed in hippocampus (rat)63, striatum (mouse)64, pons-medulla (mouse)39, mid-brain (mouse)39, and cerebral cortex (mouse)39, while GD1b was found to be the major component of olfactory bulb (mouse)39, cerebellum (mouse)39, and PFC (human)17. These results, which are in line with earlier investigations, not only serve as a biological cross-confirmation of our data but also underscore the feasibility of our analytical platform as a robust tool for reliable mammalian brain studies. Notably, we simultaneously compared nine different brain regions and conducted quantitative analyses to assess the varying expression of each isomer of GD1a and GD1b across these different brain regions. This approach offers significant advantages for unbiased searches, facilitating the identification of potential drug targets, including individual gangliosides, specific epitopes, or relevant enzymes.

As highlighted throughout the results section, a prominent feature of our study, examining the nine distinct brain regions, is the consistent clustering of these regions into two primary groups across three separate analyses: (1) comprehensive ganglioside profile (Fig. 4a), (2) the region-specific quantification of ganglioside GD1a/GD1b isomers (Fig. 5), and (3) the N-glycan profile (Fig. 6c). Group I comprise the PFC, olfactory bulb, and cerebellum, while Group II include cerebral cortex, striatum, hippocampus, diencephalon, midbrain, and pons-medulla. Each group showed a high degree of internal similarity among its regions, but significant differences were noted between the two groups. Further intermolecular analyses are warranted to elucidate the detailed mechanisms associated with the spatial specificity of glycans and gangliosides. Given the distribution of the isomers and the products of each series pathway in different brain regions, the retrosynthetic ganglioside network exhibited region specificity and commonality in the mouse brain. In the retrosynthetic network, the ganglioside products from the b-series pathway were dominant in Group I, while those from the a-series pathway were dominant in Group II. Importantly, distinguishing the different pathways for synthesizing each ganglioside isoform could provide valuable insight into the molecular mechanism underlying region-specific biological functions. Particularly, the roles of ganglioside isomers, GD1a and GD1b, are of interest due to their significant implications in neurological disorders like Alzheimer’s disease, and in various brain functions including myelin-axon interaction maintenance, development, and overall brain health65,66. Considering the multiple approaches employed in this study, which include analysis based on (i) total individual gangliosides, (ii) only glycan moieties, (iii) only ceramide moieties, and (iv) only the positional isomer GD1a/GD1b, the results consistently support the primary classification into Group I and Group II. This robust evidence underlines the notion of clear region-specific distributions of ganglioside isomers, encouraging further spatially resolved studies to uncover the underlying region-specific molecular mechanisms.

The brain’s intricate network of connections supports its complex functionality, making it difficult to assign specific roles to brain regions based solely on their interconnectivity. Despite this complexity, notable patterns have been observed in Group I regions, which include the PFC, olfactory bulb, and cerebellum. It is well-established that ganglioside expression varies across different cellular and structural compartments, such as various cell types, and between white and gray matter39,67. Yet, there are no comprehensive comparative studies that identify unique commonalities in cellular and structural similarities across these three regions, which could be an interesting area for future research. Beyond the variation in ganglioside expression influenced by cellular and structural components, there is evidence that ganglioside contributes to synaptic transmission and synapse formation requiring for functional neural circuit formation in the brain6,68,69,70. These observations raise the possibility that these regions may exhibit functional connectivity, potentially linked to specific patterns of neuronal activation. However, direct evidence for such associations remains to be established. Notably, these regions are central to odor processing71. The direct connection between the olfactory bulb and the PFC is vital for integrating olfactory and cognitive functions. Moreover, recent studies have suggested that the cerebellum plays a role in emotional responses to olfactory stimuli, showing increased activation in response to unpleasant odors. These findings hint at potential, yet unexplored, roles for specific gangliosides in neural activation and synaptic transmission within the brain’s functional networks. However, since we have not yet conducted concrete studies to explore these possibilities, these remain speculative but compelling areas for future investigation. Our comprehensive profiling of mouse brains using an isomer-specific analytical platform undoubtedly serves as a valuable reference for future brain ganglioside research, elucidating the relationship between brain function and these molecules. Our findings also offer significant insights into the potential connections between gangliosides and glycans, which have thus far remained missing pieces of the puzzle. Furthermore, given the notably higher interspecies similarities in the glycan portions of brain gangliosides between humans and mice compared to those in blood or other non-neural tissues72. This similarity is likely due to the reduced presence of NeuGc modifications in the mouse brain, underscoring the relevance of mice as an animal model for studying human brain gangliosides. Previous postmortem studies in humans have demonstrated that neurological disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease exhibit region-specific glycosylation changes in several key proteins73,74,75. Broadly speaking, our methodologies and current molecular-level findings may contribute to future research endeavors aimed at exploring the causal relationship between altered brain region-specific gangliosides and cognitive or emotional functions, as well as the pathogenesis of neuropsychiatric and neurodegenerative diseases. By elucidating these glyco-related mechanisms, our research opens avenues for identifying targets for drug development and therapeutic interventions.

Methods

Materials

HEPES, Methanol, Chloroform, Potassium chloride, Potassium hydroxide, and sucrose were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (MO, USA). Sep-Pak C18 cartridge was obtained from Waters (Milford, MA). Ammonium formate and Formic acid were obtained from Honeywell (North Carolina, US). Ganglioside standard was purchased from Avanti Polar Lipid, Inc. (Alabaster, AL). A protease inhibitor cocktail (Set V, Animal-Free) was purchased from Calbiochem (CA, USA). Ethanol was purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany).

Animals

C57BL/6 J mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory and bred in-house for experiments. The mice were housed in a controlled environment with ambient temperatures maintained between 20 and 22 °C and humidity levels set at 40−60%, with unrestricted access to food and water. A 12-hour light/dark cycle was implemented to mimic natural circadian rhythms. No more than five mice were housed in a single cage after weaning at postnatal day 19−21. Mating cages were monitored daily in the morning to determine exact birthdates, with the day of birth defined as postnatal day 0. All procedures were performed in compliance with the Institute for Basic Science (IBS) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) guidelines.

Tissue samples

Tissue samples were collected from four male mice per age group (n = 4) on postnatal day 72 (week 10). Mice were euthanized via carbon dioxide inhalation followed by cervical dislocation, after which their brains were immediately harvested. The brains were then dissected into nine regions: cerebral cortex, PFC, striatum, hippocampus, olfactory bulb, diencephalon, midbrain, pons-medulla, and cerebellum, following previously established protocols with slight modifications76. Tissue from both hemispheres was collected, flash-frozen, and stored at −80 °C until further processing for glycan analysis.

Mouse brain tissue homogenization

Dissected mouse brain regions were homogenized by grinding with lysis buffer. The homogenization buffer (0.25 M sucrose, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5) contained a 1:100 protease inhibitor mixture (Calbiochem/EMD Chemicals).

Extraction of gangliosides from mouse brain

Extraction of gangliosides from mouse brain tissue was performed using a modified protocol based on the Folch77 and Bligh-Dyer methods78. Initially, 3 vol of homogenized tissue samples were mixed with methanol/chloroform (8:4; v/v). The solutions were sonicated for 30 min and centrifuged at 8800 × g for 2 min at 4 °C. Supernatants were collected, and the pellet was re-extracted sequentially with chloroform/methanol/water (4:8:3; v/v/v), chloroform/methanol (1:1; v/v), and chloroform/methanol (2:1; v/v). All supernatants were combined, dried under vacuum, and partitioned again with chloroform/methanol (2:1; v/v). For Folch partitioning, 200 μL of 0.1 M KCl was added, and the solution was centrifuged at 8800 × g for 2 min at 4 °C. The upper fraction was collected, and the lower fraction was re-extracted with 400 μL of methanol/0.1 M KCl (1:1; v/v). This step was repeated once more. The pooled upper fractions were washed with 500 μL of chloroform/methanol (2:1; v/v). Gangliosides were further purified and enriched using C18-SPE. The Sep-Pak C18 cartridge (200 mg, 3 mL) was pre-washed with methanol, chloroform/methanol (1:1; v/v), and water. The upper fraction of extracted gangliosides was loaded onto the cartridge, which was then washed with water to remove salts and buffers. Gangliosides were eluted stepwise with chloroform/methanol (1:1; v/v) and chloroform/methanol/water (4:8:3; v/v/v). The two fractions were dried under Speed Vac and resolubilized with methanol/water (1:1; v/v)78.

Positive-ion detection mode UHPLC Q-TOF MS analysis of gangliosides

Extracted gangliosides were chromatographically separated and analyzed using an Agilent 6550 Q-TOF MS coupled with an Agilent 1290 series UHPLC system. (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Reversed-phase analysis was performed on an Agilent Eclipse Plus C18 column (2.1 × 50 mm, 1.8 μm particle size) for chromatographic separation. Solvent A consisted of water, and solvent B was methanol. Both solvents contained 10 mM ammonium formate and 0.2% formic acid. The flow rate was 0.4 mL/min, and the column temperature was controlled at 45 °C. The injection volume was 2–5 μL. The gradient used for this separation was as follows: 0 min: 20.0% A + 80.0% B; 3 min: 15.0% A + 85.0% B; 17–19 min: 0.0% A + 100.0% B; 19.01-20 min: 20.0% A + 80.0% B. Finally, the re-equilibration time between runs is 20 min. The Agilent 6550 Q-TOF MS was detected in the positive-ion mode for MS scans as well as MS/MS. The acquisition parameters were as follows: 14 l/min for drying gas flow, 200 °C for drying gas temperature, 20 psi for nebulizer pressure, 11 l/min for sheath gas flow, 250 °C for sheath gas temperature, and 4000 V for spray voltage. In addition, MS and MS/MS mass range were m/z 300–2000 and m/z 100–3000, respectively. And acquisition rates were 1.0 s/spectra for MS and 1.0 s/spectra for MS/MS. Used collision gas was nitrogen. CID-MS/MS analysis was performed in positive mode with collision energy (CE) set at 20, 40 and 60 eV. But the slope and offset values of the energy-m/z ram could be adjusted to higher or lower values in order to produce more or less fragmentation.

Statistical method

The identification of gangliosides was accomplished by examining their m/z, RT, and MS/MS fragmentation patterns. MetaboAnalyst 4.0 by PLS-DA and unsupervised hierarchical clustering heatmaps was utilized for. Multivariate analyses of the differentially expressed gangliosides. The gangliosides’ quantified intensity was normalized by the quantile normalization method after imputing missing values with half of the minimum value in the data, followed by log transformation and mean centering. To assess the differences between the cell lines, ANOVA was performed, followed by Fisher’s post-hoc test. Finally, the hierarchical clustering of gangliosides was carried out using the Euclidean distance and Ward clustering algorithm, with only those gangliosides having a p value <0.05 being included in the analysis.

MS data processing for quantification

The data underwent processing through Agilent Technologies’ Mass Hunter Qualitative Analysis software, specifically Version B.06.00 SP1. The molecular feature extractor algorithm was utilized to extract compounds with a 20 ppm mass tolerance. Through the use of the anticipated isotopic distribution, charge state information, and RT, all isotopologues that are linked with a specific compound were combined, including the doubly protonated ion, triply protonated ion, and other relevant ions, and the neutral mass of the compound was determined. Subsequently, a compilation of all compound peaks in the sample was created based on this information. The accurate mass enabled computer algorithms to recognize the ganglioside compositions.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the supplementary information. Any additional raw data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Mlinac, K. et al. Structural analysis of brain ganglioside acetylation patterns in mice with altered ganglioside biosynthesis. Carbohydr. Res. 382, 1–8 (2013).

Ariga, T. & McDonald, M. P. Robert KY. Thematic review series: sphingolipids. Role of ganglioside metabolism in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease—a review. J. Lipid Res. 49, 1157–1175 (2008).

Svennerholm L. Gangliosides and synaptic transmission. In: Structure and function of gangliosides. Springer (1980).

Mocchetti, I. Exogenous gangliosides, neuronal plasticity and repair, and the neurotrophins. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 62, 2283–2294 (2005).

She, J. Q., Wang, M., Zhu, D. M., Sun, L. G. & Ruan, D. Y. Effect of ganglioside on synaptic plasticity of hippocampus in lead-exposed rats in vivo. Brain Res. 1060, 162–169 (2005).

Palmano, K., Rowan, A., Guillermo, R., Guan, J. & McJarrow, P. The role of gangliosides in neurodevelopment. Nutrients 7, 3891–3913 (2015).

Sugiura, Y. et al. Sensory nerve-dominant nerve degeneration and remodeling in the mutant mice lacking complex gangliosides. Neuroscience 135, 1167–1178 (2005).

Sántha, P., Dobos, I., Kis, G. & Jancsó, G. Role of gangliosides in peripheral pain mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 1005 (2020).

Ariga, T. The pathogenic role of ganglioside metabolism in Alzheimer’s disease-cholinergic neuron-specific gangliosides and neurogenesis. Mol. Neurobiol. 54, 623–638 (2017).

Rahmann, H. Brain gangliosides and memory formation. Behav. Brain Res. 66, 105–116 (1995).

Yoon, J. H. et al. Brain lipidomics: from functional landscape to clinical significance. Sci. Adv. 8, eadc9317 (2022).

Schneider J. Gangliosides and glycolipids in neurodegenerative disorders. In: Glycobiology of the Nervous System. Springer (2014).

Ariga, T. Pathogenic role of ganglioside metabolism in neurodegenerative diseases. J. Neurosci. Res. 92, 1227–1242 (2014).

Han, X., MH, D., McKeel, D. W. Jr., Kelley, J. & Morris, J. C. Substantial sulfatide deficiency and ceramide elevation in very early Alzheimer’s disease: potential role in disease pathogenesis. J. Neurochem. 82, 809–818 (2002).

Mabe, N. W. et al. Transition to a mesenchymal state in neuroblastoma confers resistance to anti-GD2 antibody via reduced expression of ST8SIA1. Nat. Cancer 3, 976–993 (2022).

Huebecker, M. et al. Reduced sphingolipid hydrolase activities, substrate accumulation and ganglioside decline in Parkinson’s disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 14, 40 (2019).

Kracun, I., Kalanj, S., Talan-Hranilovic, J. & Cosovic, C. Cortical distribution of gangliosides in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem. Int. 20, 433–438 (1992).

Svennerholm, L. & Gottfries, C. G. Membrane-lipids, selectively diminished in Alzheimer brains, suggest synapse loss as a primary event in early-onset form (type-I) and demyelination in late-onset form (type-Ii). J. Neurochem. 62, 1039–1047 (1994).

Kalanj, S., Kracun, I., Rosner, H. & Cosovic, C. Regional distribution of brain gangliosides in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurol. Croat. 40, 269–281 (1991).

Jana, A. & Pahan, K. Sphingolipids in multiple sclerosis. Neuromol. Med. 12, 351–361 (2010).

Lee, J. et al. Spatial and temporal diversity of glycome expression in mammalian brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 28743–28753 (2020).

Sharma, K. et al. Cell type- and brain region-resolved mouse brain proteome. Nat. Neurosci. 18, 1819–1831 (2015).

Ivanisevic, J. et al. Brain region mapping using global metabolomics. Chem. Biol. 21, 1575–1584 (2014).

Hawrylycz, M. J. et al. An anatomically comprehensive atlas of the adult human brain transcriptome. Nature 489, 391–399 (2012).

Ng, L. et al. An anatomic gene expression atlas of the adult mouse brain. Nat. Neurosci. 12, 356–362 (2009).

Lee, B. & An, H. J. Small but big leaps towards neuroglycomics: exploring N-glycome in the brain to advance the understanding of brain development and function. Neural Regen. Res. 19, 489–490 (2023).

De Baecque, C., Johnson, A. B., Naiki, M., Schwarting, G. & Marcus, D. M. Ganglioside localization in cerebellar cortex: an immunoperoxidase study with antibody to GM1 ganglioside. Brain Res. 114, 117–122 (1976).

Byers, D. M., Irwin, L. N. & Cabeza, R. Ganglioside patterns mature at different rates in functionally related subregions of the rat pons. Dev. Neurosci. 24, 478–484 (2002).

Laev, H., Rapport, M. M., Mahadik, S. P. & Silverman, A.-J. Immunohistological localization of ganglioside in rat cerebellum. Brain Res. 157, 136–141 (1978).

Molander, M., Berthold, C. H., Persson, H. & Fredman, P. Immunostaining of ganglioside GD1b, GD3 and GM1 in rat cerebellum: cellular layer and cell type specific associations. J. Neurosci. Res. 60, 531–542 (2000).

Goto-Inoue, N. et al. The detection of glycosphingolipids in brain tissue sections by imaging mass spectrometry using gold nanoparticles. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 21, 1940–1943 (2010).

Colsch, B. & Woods, A. S. Localization and imaging of sialylated glycosphingolipids in brain tissue sections by MALDI mass spectrometry. Glycobiology 20, 661–667 (2010).

Li, Z. & Zhang, Q. Ganglioside isomer analysis using ion polarity switching liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 413, 3269–3279 (2021).

Wojcik, R. et al. Lipid and glycolipid isomer analyses using ultra-high resolution ion mobility spectrometry separations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18, 183 (2017).

Hu, T., Jia, Z. X. & Zhang, J. L. Strategy for comprehensive profiling and identification of acidic glycosphingolipids using ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 89, 7808–7816 (2017).

Kirschbaum, C. et al. Unravelling the structural complexity of glycolipids with cryogenic infrared spectroscopy. Nat. Commun. 12, 1–7 (2021).

Lee, J. et al. Comprehensive profiling of surface gangliosides extracted from various cell lines by LC-MS/MS. Cells 8, 1323 (2019).

Sturgill, E. R. et al. Biosynthesis of the major brain gangliosides GD1a and GT1b. Glycobiology 22, 1289–1301 (2012).

Vajn, K., Viljetic, B., Degmecic, I. V., Schnaar, R. L. & Heffer, M. Differential distribution of major brain gangliosides in the adult mouse central nervous system. Plos One 8, e75720 (2013).

Kohla, G., Stockfleth, E. & Schauer, R. Gangliosides with O-acetylated sialic acids in tumors of neuroectodermal origin. Neurochem. Res. 27, 583–592 (2002).

Mandal, C., Schwartz-Albiez, R. & Vlasak, R. Functions and biosynthesis of O-acetylated sialic acids. Top. Curr. Chem. 366, 1–30 (2012).

Siebert, H.-C. et al. Molecular dynamics-derived conformation and intramolecular interaction analysis of the N-acetyl-9-O-acetylneuraminic acid-containing ganglioside GD1a and NMR-based analysis of its binding to a human polyclonal inununoglobulin G fraction with selectivity for O-acetylated sialic acids. Glycobiology 6, 561–571 (1996).

Varki, N. M. & Varki, A. Diversity in cell surface sialic acid presentations: implications for biology and disease. Lab. Invest. 87, 851–857 (2007).

Hájek, R., Jirásko, R., Lísa, M., Cifková, E. & Holcapek, M. Hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry characterization of gangliosides in biological samples. Anal. Chem. 89, 12425–12432 (2017).

Todeschini, A. R. & Hakomori, S. I. Functional role of glycosphingolipids and gangliosides in control of cell adhesion, motility, and growth, through glycosynaptic microdomains. Biochem. Biophys. Acta 1780, 421–433 (2008).

Itokazu, Y., Wang, J. & Yu, R. K. Gangliosides in nerve cell specification. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. 156, 241–263 (2018).

Ngamukote, S., Yanagisawa, M., Ariga, T., Ando, S. & Yu, R. K. Developmental changes of glycosphingolipids and expression of glycogenes in mouse brains. J. Neurochem. 103, 2327–2341 (2007).

Kronewitter, S. R. et al. The development of retrosynthetic glycan libraries to profile and classify the human serum N‐linked glycome. Proteomics 9, 2986–2994 (2009).

Kolter, T. Ganglioside biochemistry. ISRN Biochem. 2012, 506160 (2012).

Bieberich, E. et al. Regulation of ganglioside biosynthesis by enzyme complex formation of glycosyltransferases. Biochemistry 41, 11479–11487 (2002).

Giraudo, C. G., Daniotti, J. L. & Maccioni, H. J. F. Physical and functional association of glycolipid -acetyl-galactosaminyl and galactosyl transferases in the Golgi apparatus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 1625–1630 (2001).

Giraudo, C. G. & Maccioni, H. J. Ganglioside glycosyltransferases organize in distinct multienzyme complexes in CHO-K1 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 40262–40271 (2003).

Bieberich E. Synthesis, processing, and function of N-glycans in N-glycoproteins. In: Glycobiology of the nervous system. Springer (2014).

Bieberich, E., Freischutz, B., Liour, S. S. & Yu, R. K. Regulation of ganglioside metabolism by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. J. Neurochem. 71, 972–979 (1998).

Katoh, T. et al. Deficiency of α-glucosidase I alters glycoprotein glycosylation and lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. Glycobiology 23, 1142–1151 (2013).

Barone, R. et al. CSF N‐glycan profile reveals sialylation deficiency in a patient with GM2 gangliosidosis presenting as childhood disintegrative disorder. Autism Res. 9, 423–428 (2016).

Lawrence, R. et al. Characterization of glycan substrates accumulating in GM1 Gangliosidosis. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 21, 100524 (2019).

Cavender, C. et al. Natural history study of glycan accumulation in large animal models of GM2 gangliosidoses. Plos One 15, e0243006 (2020).

Hakomori, S. I. Structure and function of glycosphingolipids and sphingolipids: recollections and future trends. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1780, 325–346 (2008).

Veillon, L. et al. Characterization of isomeric glycan structures by LC-MS/MS. Electrophoresis 38, 2100–2114 (2017).

Ikeda, K. & Taguchi, R. Highly sensitive localization analysis of gangliosides and sulfatides including structural isomers in mouse cerebellum sections by combination of laser microdissection and hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization mass spectrometry with theoretically expanded multiple reaction monitoring. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom 24, 2957–2965 (2010).

Albrecht, S. et al. Comprehensive profiling of glycosphingolipid glycans using a novel broad specificity endoglycoceramidase in a high-throughput workflow. Anal. Chem. 88, 4795–4802 (2016).

Tettamanti G., Ledeen R., Sandhoff K., Nagai Y., Toffano G. Gangliosides and neuronal plasticity. In: Springer Science & Business Media (2013).

Maglione, V. et al. Impaired ganglioside metabolism in Huntington’s disease and neuroprotective role of GM1. J. Neurosci. 30, 4072–4080 (2010).

Barrier, L. et al. Genotype-related changes of ganglioside composition in brain regions of transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 28, 1863–1872 (2007).

Schnaar, R. L. & Lopez, P. H. Myelin‐associated glycoprotein and its axonal receptors. J. Neurosci. Res. 87, 3267–3276 (2009).

Vasques, J. F. et al. Gangliosides in nervous system development, regeneration, and pathologies. Neural Regen. Res. 18, 81–86 (2023).

Thomas, P. D. & Brewer, G. J. Gangliosides and synaptic transmission. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1031, 277–289 (1990).

Fujii, S. et al. Effects of the mono-and tetrasialogangliosides GM1 and GQ1b on ATP-induced long-term potentiation in hippocampal CA1 neurons. Glycobiology 12, 339–344 (2002).

Zhang, Z. et al. Ganglioside GQ1b induces dopamine release through the activation of Pyk2. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 71, 102–113 (2016).

Manan H. A., Yahya N., Han P., Hummel T. A systematic review of olfactory-related brain structural changes in patients with congenital or acquired anosmia. Brain Struct. Funct. 227, 177–202 (2022).

Seyfried, T. N., el-Abbadi, M. & Roy, M. L. Ganglioside distribution in murine neural tumors. Mol. Chem. Neuropathol. 17, 147–167 (1992).

Tena, J. et al. Regio-specific N-glycome and N-glycoproteome map of the elderly human brain with and without Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Cell Proteom. 21, 100427 (2022).

Frenkel-Pinter, M. et al. Interplay between protein glycosylation pathways in Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Adv. 3, e1601576 (2017).

Rebelo A. L., Drake R., Marchetti-Deschmann M., Saldova R., Pandit A. Changes in tissue protein N-glycosylation and associated molecular signature occur in the human parkinsonian brain in a region-specific manner. PNAS nexus 3, pgad439 (2022).

Spijker S. Dissection of rodent brain regions. In: Neuroproteomics (ed. Li K. W.). Humana Press (2011).

Folch, J., Lees, M. & Stanley, G. S. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 226, 497–509 (1957).

Li Q., Xie Y., Wong M., Barboza M., Lebrilla C. B. Comprehensive structural glycomic characterization of the glycocalyxes of cells and tissues. Nat. Protoc. 15, 2668–2704 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Institute for Basic Science (IBS-R001-D2-2023-A03) and the Commercialization Promotion Agency for R&D Outcomes (COMPA) funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (MSIT) (2024-24020010-11r, R&D Equipment Engineer Education Program). Additionally, this work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (Ministry of Science and ICT) (RS-2023-00267020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: C.J.L., H.-S.S., and H.J.A. Methodology: J.L., and H.J.A. Investigation: J.L., M.K., S.-W.K. H.H., D.Y., J.Y., and J.E.P. Funding acquisition: C.J.L., H.-S.S., and H.J.A. Visualization: J.L., D.Y., J.Y., and J.E.P. Writing—original draft: J.L. Writing—review and editing: J.L., B.L., D.Y., J.E.P, H.-S.S., and H.J.A.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Michal Holcapek, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, J., Yin, D., Yun, J. et al. Deciphering mouse brain spatial diversity via glyco-lipidomic mapping. Nat Commun 15, 8689 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53032-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53032-8

This article is cited by

-

Deficiency of Toll-like receptor 2 is a driver of sex-related compositional and structural rearrangements of membrane lipids

Communications Chemistry (2025)

-

The emerging landscape of brain glycosylation: from molecular complexity to therapeutic potential

Experimental & Molecular Medicine (2025)

-

Identification of nine mammal monosaccharides by solid-state nanopores

Scientific Reports (2024)