Abstract

Polygenic prediction has yet to make a major clinical breakthrough in precision medicine and psychiatry, where the application of polygenic risk scores is expected to improve clinical decision-making. Most widely used approaches for estimating polygenic risk scores are based on summary statistics from external large-scale genome-wide association studies, which rely on assumptions of matching data distributions. This may hinder the impact of polygenic risk scores in modern diverse populations due to small differences in genetic architectures. Reference-free estimators of polygenic scores are instead based on genomic best linear unbiased predictions and model the population of interest directly. We introduce a framework, named hapla, with a novel algorithm for clustering haplotypes in phased genotype data to estimate heritability and perform reference-free polygenic prediction in complex traits. We utilize inferred haplotype clusters to compute accurate heritability estimates and polygenic scores in a simulation study and the iPSYCH2012 case-cohort for depression disorders and schizophrenia. We demonstrate that our haplotype-based approach robustly outperforms standard genotype-based approaches, which can help pave the way for polygenic risk scores in the future of precision medicine and psychiatry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Polygenic prediction has become a major field of interest due to its potential impact and role in personalized medicine using estimated polygenic risk scores (PRSs)1. A PRS is a summarization of an individual’s genetic predisposition for a given disease or trait and is in its simplest form a weighted sum of risk alleles usually derived from large-scale genome-wide association studies (GWAS). However, most common diseases are complex traits and have thousands of risk-associated single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with very small effect sizes, limiting the breakthroughs for the clinical utility of PRSs in personalized medicine. Early large-scale quantitative genetics research has additionally been biased towards individuals of European ancestry, further limiting the clinical utility of PRSs in modern diverse populations and the majority of the global population2.

Polygenic prediction is also of great interest to precision psychiatry, where the complex etiologies of psychiatric disorders are yet to be untangled, and PRSs have the potential to aid in the clinical decision-making and individualized treatment for patients in the future3,4. Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a disabling common illness and an increasing global health concern as it contributes substantially to the growing disease burden5, whereas schizophrenia (SCZ) remains a substantial burden to society even with a low population prevalence of ~1%6,7. Severe mental disorders therefore call for action to further efforts in understanding the genetic contributions in their etiologies. MDD and SCZ are both highly polygenic traits with 243 identified risk loci from a large-scale meta-analysis8 for MDD, and 287 distinct loci for SCZ as well from a large-scale meta-analysis9.

The two main approaches for performing polygenic prediction are denoted reference-based and reference-free, also referred to as summary statistics based and individual-level data based, respectively. Recent work shows that the combination of the two approaches can lead to increased predictive performance for complex traits10. The reference-based approach is based on summary statistics from an external large-scale GWAS, where the marginal regression coefficients of the SNPs are used to construct a PRS estimator11,12,13. Unfortunately, the reliance on an external large-scale GWAS has shown the now well-known portability problem in PRS estimators14. Issues arise due to assumptions of similarity in the generative phenotype process between the reference population and the target population including their linkage disequilibrium (LD) patterns leading to restrictions in the SNP set used for polygenic prediction2,15,16,17. The genetic distance between the reference population and the target population has been shown to be directly correlated with the portability issues of a constructed PRS estimator18. Even for homogeneous ancestries, it has been shown that reference-based PRS estimators are still strongly influenced by the external GWAS, as PRSs can correlate with uncorrected population structure19,20,21.

Reference-free polygenic prediction does not rely on pre-estimated summary statistics of an external GWAS but is instead based on the joint modeling of SNPs in the target population using a linear mixed model (LMM)22, thus accounting for LD between SNPs23. LMMs are the state-of-the-art approach to account for population structure and cryptic relatedness in modern GWAS methods24,25. The LMM frameworks estimate SNP heritability of a trait based on genome-based restricted maximum likelihood (GREML) given an estimated genome-wide relationship matrix (GRM)26. The inferred SNP heritability is implicitly used in the prediction of a polygenic score as well, also known as the best linear unbiased prediction (BLUP)27. However, recently it has been shown that naive BLUPs overfit the genetic effect by modeling non-genetic effects as well, and the study introduces a well-performing leave-one-out cross-validated BLUP (cvBLUP) estimator28.

Haplotype-based methods have received greater interest in recent years due to their increased power in detecting fine-scale population structure29,30, local ancestry inference31, heritability estimation, and GWAS32, and additionally, having increased accuracy in genomic prediction33,34 but they have yet to make an impact in precision medicine and psychiatry. These methods directly model LD patterns through haplotype information and should therefore be able to tag unobserved causal SNPs, which are poorly captured by an SNP array or imputed genotype data, due to the unobserved SNPs likely being in identity-by-state for long haplotypes being in identity-by-state35. Multiple approaches including local ancestry tracts inferred from haplotypes have also been developed to estimate SNP heritability36 and construct reference-based PRS estimators37.

In this work, we introduce a novel haplotype-based framework, hapla, which infers haplotype clusters in windows along the genome from phased genotype data in a fast and parallelized approach. We utilize haplotype cluster assignments to construct a GRM, estimate heritability, and perform reference-free polygenic prediction in complex traits using cvBLUPs that outperform standard genotype-based approaches. We show and evaluate its performance in a simulation study and hereafter showcase its capabilities in heritability estimation and polygenic prediction of depression disorders and SCZ in the large Danish Integrative Psychiatric Research Consortium (iPSYCH) 2012 case-cohort38. The gain from leveraging haplotype information efficiently has the potential to advance precision medicine and psychiatry in modern diverse populations.

Results

Overview of the hapla framework

The hapla framework aims to leverage haplotype information in heritability estimation and polygenic prediction through inferred haplotype clusters from phased genotype data. We introduce a novel clustering algorithm (PDP-DC-Medians) which we use to cluster haplotypes in windows along the genome (Step 1, Fig. 1). The size of the windows is determined as a fixed number of predefined SNPs, B, and windows are allowed to overlap, which effectively creates a sliding window approach for a given step-size, L, being 1≤L≤B SNPs. Different choices of window sizes and step-sizes can model distinct aspects of the haplotype architecture. Haplotype clusters are modeled as cluster medians that act as representatives of all their assigned haplotypes. We therefore assign haplotypes to the inferred clusters based on the Manhattan distance between the corresponding cluster medians and the haplotypes, to obtain window-based haplotype cluster assignments across the genome for each individual. The cluster assignments across all windows are summarized in a genotype format based on the inferred haplotype cluster alleles, which we then use to estimate a GRM that captures the covariance between individuals using haplotype cluster information (Step 2, Fig. 1). We finally use the estimated GRM based on haplotype cluster alleles in the GCTA26 software to estimate SNP heritability and leave-one-out cross-validated polygenic predictions (cvBLUPs) in a LMM (Step 3, Fig. 1).

Haplotypes are clustered in windows along a chromosome to produce haplotype cluster assignments in each genomic window (Step 1). The haplotype cluster assignments across the genome are aggregated for each individual and are used to estimate the genome-wide relationship matrix (Step 2). Using the GCTA software, the genome-wide relationship matrix is used for heritability estimation and polygenic prediction (Step 3).

Heritability estimation and polygenic prediction in simulation study

To evaluate the capabilities of hapla in heritability estimation and polygenic prediction, we generated genetic data of a 100Mb chromosomal segment for a total of 20,000 individuals from two different populations in an out-of-Africa demographic model (AFR and EUR). We also evaluated the combined data, denoted ALL, to investigate the effect of modeling a structured population. We simulated phenotypes independently in each population for three different scenarios, sampling 1000 causal loci from the full variant sets, replicated 10 times. The genetic liabilities were defined as an additive model, and the causal effects were assumed to be Gaussian. Scenario 1 and 2 were SNP-based assuming h2 = 0.8 and h2 = 0.2, respectively, and Scenario 3 was haplotype cluster-based assuming h2 = 0.8 using overlapping windows of B = 8 SNPs. Additionally, we generated datasets with downsampled SNP sets to emulate loss of information due to for example imperfect imputation or using SNP arrays, which we evaluated as well for all scenarios. We reported the SNP heritability estimates and the predictive performance of the estimated polygenic scores (cvBLUPs), which were evaluated using a standard R2 metric with the phenotypes. We included the top 20 principal components as fixed-effects covariates to account for population structure in the GREML and cvBLUP estimations, which were estimated independently for each dataset.

Hyperparameters of hapla and multiple genetic effects

The window size used in hapla might affect the haplotype information extracted, and we therefore investigated its performance using different window sizes, as well as a joint approach with multiple genetic effects that combines the different window sizes, to find an optimal modeling procedure. We inferred haplotype clusters in overlapping windows across the simulated chromosomal segment for multiple window sizes, B = {1, 8, 16, 32} using a step-size L = ⌈B/2⌉ in each case, to capture potential recombination events (Supplementary Table 2). Here B = 1 represented the usage of standard SNP information within our framework. We clustered the haplotypes in less than 3.5 min across all window sizes for all datasets, showcasing the speed of our clustering algorithm (Supplementary Fig. 2).

We evaluated the window sizes independently, but also jointly, where we estimated multiple genetic effects by including the computed GRMs of each of the window sizes, which we referred to as “Multi” in the following results. The results of the different window sizes were shown in Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 5 for Scenario 1. When evaluating the window sizes independently using the full datasets, the heritability estimates were very consistent around 0.8 across the different subsets, however, the predictive performance decreased for larger window sizes in comparison to B = 1, of which the phenotypes were simulated from. A similar pattern of consistent heritability estimates was observed for the downsampled datasets except for B = 1, which heavily underestimated the heritability in AFR with 0.6706, however, we saw again a general decrease in the predictive performance for increasing window sizes. In Scenario 2 (Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 6), the phenotypes were simulated using h2 = 0.2. We observed the same overall consistent heritability estimates across the different window sizes using both full and downsampled datasets, except for B = 1 using the downsampled datasets, which again underestimated the heritability in all three subsets with 0.1488, 0.1785, and 0.1663 for AFR, EUR and ALL, respectively. The genetic predictions followed the same trend as in Scenario 1, where the predictive performance decreased for larger window sizes. Lastly, Scenario 3 produced almost identical results to Scenario 1, though with an overall reduced performance across all combinations for both the full and downsampled datasets (Supplementary Fig. 5 and Supplementary Table 7). Here B = 8, of which the phenotypes were simulated from, had the overall best performance using the full datasets as expected.

Lastly, we modeled the genetic effects from each GRM jointly, and we observed that it performed almost identically to B = 1 in Scenario 1 and 2 and B = 8 in Scenario 3 using the full datasets, which were also separate partitions in the Multi approach. It outperformed every other configuration in all three scenarios using the downsampled datasets in terms of the predictive performance of polygenic scores, and it almost matched the best-performing configuration in heritability estimations, which was most often itself. This indicated that the different window sizes captured different haplotype information, such that the Multi approach could take advantage of all partitions and retain overall high accuracy in heritability estimates and predictive performance of polygenic scores, and thus, we would only consider the Multi approach from this point on. We tested the robustness of hapla in terms of choices for its hyperparameters (λ and L) using the Multi approach in Scenario 1 (Supplementary Fig. 8). The results were consistent across all three subsets for both the full and downsampled datasets, demonstrating that hapla is robust to hyperparameter changes, and we use the default values (λ = 0.1 and L = ⌈B/2⌉) in all following analyzes.

Comparison of hapla to genotype-based approaches

We compared the results of the hapla approach using multiple genetic effects from different window sizes to two genotype-based GRMs computed in GCTA to demonstrate the gain of using haplotype information in heritability estimation and polygenic prediction. Here one was estimated in a standard procedure, referred to as “GCTA”, and the other was based on LD pruned genotype datasets, referred to as “Pruned”, which was a common procedure to reduce computational burdens.

In Scenario 1 (h2 = 0.8), we immediately observed that hapla was outperforming the other two approaches in all three subsets for both the full and the downsampled datasets based on heritability estimation and predictive performance of its polygenic scores (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 8). The predictive performance of the standard GRM in GCTA was relatively close to hapla in AFR and EUR, even though its heritability estimates were much less accurate. Our haplotype-cluster approach had relative increases in R2 of 6.8%, 4.2%, and 14.9% in the full data for AFR, EUR, and ALL, respectively, and 4.9%, 2.9%, and 10.9% in the downsampled data in comparison to GCTA. The heritability estimates of hapla were consistently more accurate, whereas the genotype-based approaches, except in ALL using the full dataset, overestimated the heritability as 0.8666 and 0.8325 for GCTA, and 0.8628 and 0.8332 for Pruned in AFR and EUR, respectively. Meanwhile in the downsampled datasets, hapla were almost on par with the heritability estimates from the full data with 0.7797, 0.7721, and 0.7775 for AFR, EUR, and ALL, respectively, whereas the genotype-based approaches severely underestimated the SNP heritability in general.

Heritability estimation and polygenic prediction in Scenario 1 across 10 phenotype simulations. The top row shows the SNP heritability estimates using the different GRMs across three subsets using either full or downsampled data, while the bottom row shows the squared correlations between the leave-one-out cross-validated polygenic predictions (cvBLUPs) and the simulated phenotypes. AFR: N = 10,000, EUR: N = 10,000, and ALL: N = 20,000. The true simulated h2 = 0.8 is displayed with a dashed line. Data are presented as mean values ± standard deviations. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Next, we performed the same analyzes in Scenario 2 with h2 = 0.2, and we similarly saw that hapla outperformed GCTA and Pruned in all scenarios based on both heritability estimation and polygenic prediction, except for the heritability estimate in ALL using the full dataset with 0.2023, 0.2027, and 0.1977 for hapla, GCTA and pruned, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 6 and Supplementary Table 9). Interestingly, we again observed a large overestimation of the SNP heritability for both GCTA and Pruned in AFR and EUR using the full dataset. Compared to GCTA, the relative increases in R2 for hapla in the full data were 11.8%, 7.7%, and 12.6% for AFR, EUR, and ALL, respectively, and 4.3%, 4.4%, and 6.9% in the downsampled data, thus showcasing larger gains from using haplotype information in the full data for Scenario 2.

In the last scenario for haplotype cluster-based phenotypes with h2 = 0.8, we observed identical results compared to Scenario 1, though with overall decreased performance for all approaches (Supplementary Fig. 7 and Supplementary Table 10). However, the gap in predictive performance between hapla or GCTA did slightly increase in favor of hapla using the downsampled data. We saw relative increases in R2 of 2.9%, 4.5%, and 14.9% for AFR, EUR, and ALL, respectively, in the full data and 9.1%, 5.2%, and 19.2% in the downsampled data. Overall we observed that LD pruning only affected results negatively in polygenic prediction across all tested scenarios and almost only produced worse heritability estimates in comparison to the standard genotype-based approach. hapla therefore in general produced more accurate and unbiased heritability estimates and more predictive polygenic scores in the simulated datasets in comparison to genotype-based approaches across multiple phenotype scenarios and diverse data subsets.

Predicting mental disorders in the iPSYCH2012 case-cohort

Following the results of the simulation study, we inferred haplotype clusters and computed GRMs in the phased imputed genotype datasets of the iPSYCH2012 case-cohort using the same window sizes and modeled multiple genetic effects (Supplementary Table 2). We evaluated three mental disorder categories, MDD, recurrent depressive disorder (REC), and SCZ, which each consisted of 20,620, 7128, and 3211 cases, respectively. We included age, gender, and the top 20 principal components as fixed-effects covariates in GREML and cvBLUP estimations, where we reported the log-likelihood, and heritability estimates on both the observed and the liability scale. The PRSs were evaluated using both Nagelkerke’s pseudo \({R}_{N}^{2}\) and Lee’s pseudo \({R}_{L}^{2}\) metrics, where Lee’s pseudo \({R}_{L}^{2}\) is more interpretable on the liability scale and takes into account case-control ascertainment bias39. We have further performed statistical significance tests on the difference in R2 metrics using the r2redux R package based on linear models40.

Heritability estimation and reference-free polygenic risk scores

Similarly to the simulation study, we compared hapla to standard genotype-based approaches in heritability estimation and predictive performance of reference-free PRSs. We clustered the haplotypes of chromosome 1 in less than 9 min for all three mental disorders using hapla, demonstrating its fast functionalities again (Supplementary Fig. 2). hapla had better predictive performance of 7.1%, 12.6%, and 12.8% relative increases in \({R}_{N}^{2}\) compared to the standard genotype-based approach in GCTA for MDD, REC, and SCZ, respectively, and of 22.3%, 32.1%, and 30.9% relative increases compared to the LD pruning approach (Fig. 3 and Table 1). We found that the differences in R2 between hapla and the two approaches are statistically significant for all evaluated cases using r2redux, with p = 0.0072, p = 0.019, and p = 0.031, when evaluated against the standard approach in GCTA, and p = 1.2 × 10−6, p = 0.0015 and p = 0.0076, evaluated against the LD pruning approach for MDD, REC, and SCZ, respectively. Similar to what we found in the simulation study, we expected heritability estimates of hapla to be more accurate and less biased, and we observed that hapla and GCTA produced relatively similar heritability estimates with 0.1447, 0.1111, and 0.1513 for MDD, REC, and SCZ, respectively, using hapla, and 0.1442, 0.1070, and 0.1544 using the standard approach in GCTA, on the liability scale. Compared to GCTA, the heritability estimates of hapla were slightly larger for depression disorders but lower for SCZ. As we observed in the simulation study, LD pruning only affected the performances negatively in polygenic prediction and overestimated heritability in comparison to the two other approaches. The log-likelihoods from GREML estimations using hapla were consistently the highest for all three mental disorders alongside predictive performance, thus further showcasing the gain from the inferred haplotype clusters.

Heritability estimation and polygenic prediction in the iPSYCH2012 case-cohort. The left plot shows the SNP heritability estimates on the liability scale using the different GRMs across the three disorders, while the right plot shows Nagelkerke’s pseudo R2 between the leave-one-out cross-validated polygenic predictions (cvBLUPs) and the binary outcomes. MDD: N = 45,848, REC: N = 32,968, and SCZ: N = 29,205. Data in the left plot are represented as heritability estimates ±1.96 × SE. Data in the right plot are represented as \({R}_{N}^{2}\) values and the interval bars span the 2.5% and 97.5% percentiles from non-parametric bootstrapping of 1000 iterations. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Reference-based polygenic risk scores from summary statistics

We computed reference-based PRSs using PRSice, a standard clumping and thresholding approach and one of the most widely used software for PRS estimation. We used GWAS summary statistics from individuals of European ancestry in the Psychiatric GWAS Consortium (PGC)9,41 excluding iPSYCH case-cohorts for both MDD and SCZ and excluding 23andMe samples for MDD to evaluate it against the reference-free approaches. The reference-based PRSs were based on ~2.5x and ~20x more cases than were available in the iPSYCH2012 case-cohort for MDD and SCZ, respectively, and the best models optimizing \({R}_{N}^{2}\) were reported (Supplementary Table 11). However, their predictive performance was 0.0037 and 0.0114 for the disorders, and they did therefore not outperform hapla (0.0241 and 0.0123) or even the other genotype-based reference-free approaches for MDD. The difference in R2 between hapla and the reference-based PRSs was statistically significant using r2redux for MDD (p = 1.2 × 10−32). PGC GWAS summary statistics were not available for REC.

We further computed correlations between the reference-based PRSs and the estimated principal components, which were used as fixed-effects covariates in all the reference-free estimations and the model optimization of PRSice, for indications of uncorrected population structure in the original GWASs. This clearly demonstrated that the reference-based PRSs correlated with structure in the iPSYCH2012 case-cohort captured by the principal components in comparison to hapla (Supplementary Fig. 9). The reference-based polygenic risk scores were highly correlated with PC1 (r = 0.3084) and PC2 (r = 0.2065) for MDD, as well as for SCZ (r = 0.4615 and r = 0.3649, respectively, for PC1 and PC6), which could inflate their predictive performance due to modeling non-genetic effects through uncorrected population structure but still did not outperform hapla.

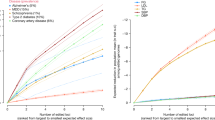

Predictive performance in individuals with at least one non-Danish born parent

Reference-based PRSs suffer from portability problems, and we investigated the predictive performances of all approaches in subsets of individuals in the iPSYCH2012 case-cohort, based on the country of birth of their parents, as we did not remove individuals due to ancestry or ethnicity in the reference-free approaches. We observed that all approaches had increased performances when focusing on individuals with both parents born in Denmark in comparison to evaluations on the full sample (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Tables 12 and 13), where the reference-based approach using PRSice was the best performing method in this subset for SCZ. The portability problem for reference-based polygenic scores was clearly shown for individuals with at least one parent not born in Denmark, where the predictive performance was severely impacted for MDD and SCZ. The reference-free PRSs were in general more robust, as there had also been no filtering based on ancestry or ethnicity in the GREML and cvBLUP estimations. hapla experienced the smallest change in predictive performance between the subsets of individuals with relative decreases in \({R}_{N}^{2}\) of 6.2%, 10.0%, and 6.9% for MDD, REC, and SCZ, respectively, compared to its best values, while outperforming all other approaches. This was in stark contrast to the reference-based PRSs of PRSice that collapsed with relative decreases of 85.2% and 85.7% for MDD and SCZ, respectively. We found the difference in R2 using r2redux between hapla and the standard genotype-based approach in GCTA statistically significant for MDD in the subset of having at least one non-Danish born parent (p = 0.046). There were still statistically significant differences for MDD between hapla and the reference-based PRSs in both subsets (p = 5.4 × 10−14 and p = 6.0 × 10−6), as well as for SCZ, in the subset of having at least one non-Danish born parent (p = 0.042). We had therefore generated more predictive and robust PRSs for individuals in the iPSYCH2012 case-cohort using our haplotype cluster approach against both standard reference-free and reference-based approaches, and even outperforming or matching reference-based PRSs from very large sample sizes in individuals with both parents born in Denmark.

Predictive performance of polygenic risk scores in subsets of the iPSYCH2012 case-cohort. The left plot shows the performance on the subset of individuals with both parents being born in Denmark, while the right plot shows the performance on the subset of individuals with at least one parent born outside Denmark. “PGC” represents the reference-based polygenic risk scores from PGC GWAS summary statistics using PRSice. PGC GWAS summary statistics were not available for REC. In the left plot, MDD: N = 39,856, REC: N = 28,504, and SCZ: N = 24,881, while in the right plot, MDD: N = 5992, REC: N = 4464, and SCZ: N = 4324. Data are represented as \({R}_{N}^{2}\) values and the interval bars span the 2.5% and 97.5% percentiles from non-parametric bootstrapping of 1000 iterations. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Discussion

We presented our framework, hapla, which performed window-based haplotype clustering in phased genotype data using our proposed PDC-DP-Medians algorithm. We explored the benefits of leveraging haplotype information in heritability estimation and reference-free polygenic prediction through the inferred haplotype clusters. In an extensive simulation study, we showcased the performance gain from our inferred haplotype clusters in multiple scenarios of diverse data subsets. hapla outperformed the widely used genotype-based GREML approach in GCTA when evaluating the accuracy of SNP heritability estimates and the predictive performance of estimated polygenic scores in the simulated data. We hypothesize that this is due to an increased tagging ability of the inferred haplotype clusters, which was especially apparent in the mixed population. Another innovation in hapla is that we combine GRMs computed from haplotype clusters of different window sizes and through this retain more haplotype information, leading to an increase in the accuracy of both heritability estimates and polygenic scores. Strikingly, the gain from utilizing haplotype clusters was even more pronounced in the downsampled datasets that resemble common cases of imperfect imputation or SNP arrays. Here hapla showcased superior performance based on both heritability estimates and polygenic scores, which almost matched the genotype-based approach having full information. This is highly promising for genetic studies where sequencing data or accurate imputation are not available. Additionally, we show that even though LD pruning has become a common procedure in large-scale genetic studies to lower computational costs, we only observed that it was detrimental to performance and should therefore be avoided.

Due to the current reliance on external summary statistics for PRS estimation, it has become common practice to remove admixed individuals and individuals of different ancestries in genetic studies that potentially affect relatively large proportions of modern populations. When applying hapla to the iPSYCH2012 case-cohort for MDD, REC, and SCZ, we were able to model all individuals directly. As shown in the simulation study, we again outperformed the two genotype-based approaches based on the predictive performance of estimated reference-free PRSs. The gain from using inferred haplotype clusters of hapla was especially large for SCZ, which notably had a significantly lower number of cases than the depression disorders. We further compared hapla to a widely-used reference-based approach (PRSice) using state-of-the-art GWAS summary statistics from European samples of the PGC for MDD and SCZ. The predictive performance of the reference-based PRSs for MDD was far below the reference-free PRSs of all other approaches, while the reference-based PRSs for SCZ performance almost matched hapla. The GWAS summary statistics of the reference-based approach were based on far more cases, especially for SCZ, thus indicating the need for much larger sample sizes to reach the performance of reference-free approaches. However, we further investigated the correlation between the reference-based PRSs of PRSice and the estimated principal components in the iPSYCH2012 case-cohort, as it is known to potentially inflate their predictive performance, which was the case for PRSice in both MDD and SCZ. This means that the PRSs estimated from the PGC GWASs potentially capture non-genetic effects due to for example uncorrected population structure, thus highlighting further potential bias in relying on external summary statistics. Finally, we demonstrated that hapla was more robust in comparison to other approaches when evaluating the PRSs for individuals with at least one non-Danish born parent. The well-known portability problem affected the reference-based approach to a very large degree, such that it lost most of its predictive performance in MDD and SCZ. The results of hapla are therefore very promising for real-world populations by overcoming some of the inclusion problems that persist in reference-based PRS, as the inferred haplotype clusters were shown to model a structured population better than other standard reference-free approaches, and in general, estimated more predictive PRSs that can advance the fields of precision medicine and psychiatry.

The standard GREML approach in GCTA assumes an infinitesimal prior on the effect sizes and multiple variations have been proposed to either increase the accuracy of heritability estimates42,43 or polygenic scores44,45. Our approach can be combined with recent advancements using more complex priors to increase the predictive performance of the reference-free polygenic scores, however, we found it within the scope of our study to solely focus on GREML as a proof of concept with our new data structure, obtaining both unbiased heritability estimates and accurate polygenic scores. Another limitation of our study is that we cluster haplotypes in genomic windows of fixed lengths. In homogeneous populations, it could be more beneficial to use LD-informed blocks as windows34,46, as boundaries of the inferred haplotype clusters would reflect frequent breakpoints, tailored to the target population, and potentially eliminate the need for clustering in overlapping windows across multiple window sizes. We further note that the reference-based PRSs from the widely used PRSice, leveraging an optimized clumping and thresholding approach, may not represent the broader range of reference-based approaches, and other available methods could achieve better predictive performance. However, most other reference-based approaches rely on population-specific LD maps, heavily restricting the SNP set used, which could also deteriorate performance in diverse populations even further, or would require the need for acquiring summary statistics from multiple large-scale GWAS, covering a diverse range of populations47.

With the ability to disentangle genetic information at haplotype level, we hypothesize that our framework can model haplotype-specific effects implicitly through the usage of inferred haplotype clusters instead of SNPs. Thus we can potentially find novel associations, which are not detected in standard SNP-based approaches for structured populations or large-scale multi-population studies. Finally, the data structure of our inferred haplotype clusters opens up exciting future research and extensions to our framework, as the clusters can be used to infer fine-scale population structure and be used in sequential models to infer local ancestry and identity-by-descent tracts as examples. The haplotype cluster medians can also serve as condensed reference panels for large-scale phasing or imputation problems and potentially mitigate privacy issues.

Methods

hapla framework

We denote X ∈ {0, 1}2N×M as the haplotype matrix of a chromosome for a given dataset of phased genotypes, consisting of 2N haplotypes and M diallelic SNPs. The haplotype matrix is assumed to be ordered such that two adjacent rows correspond to the maternal and paternal haplotypes of a single individual resulting in a total of N individuals. We split the chromosome into W genomic windows of a fixed size that can be overlapping or non-overlapping. For the sake of simple mathematical notation, we define windows in this section to be non-overlapping and to have a fixed length of B SNPs such that X = [X(1), …, X(W)] with X(w) ∈ {0, 1}2N×B for w = 1, …, W. The objective is to cluster haplotypes independently in each genomic window into a set of K haplotype clusters, where the number of defined clusters can vary between the different windows to account for non-uniform genetic diversity across the chromosome. Hereafter, we use the haplotype cluster assignments to estimate heritability and perform reference-free polygenic prediction.

Clustering algorithm

The haplotype clustering algorithm is applied to each window along a given chromosome independently. We have adopted a nonparametric clustering algorithm based on DP-Means48 and its recently proposed extension with a delayed cluster creation process, PDC-DP-Means49. The algorithms can be seen as generalizations of the K-Means algorithm, where K, the number of clusters, is unknown and inferred from the data. However, instead of minimizing the Euclidean distance between haplotypes and cluster centroids, we propose a delayed cluster creation algorithm based on minimizing the Manhattan distance between haplotypes and cluster medians50. We denote the algorithm as PDC-DP-Medians using similar terminology. The Manhattan distance is an appealing choice for binary genetic data (Hamming distance), as it can be viewed as the number of mutations between a haplotype and a cluster median, thus providing a natural evolutionary perspective to the constructed cluster medians. The cluster medians will here act as haplotype representatives of the inferred haplotype clusters. Our haplotype clustering approach (PDC-DP-Medians) is further detailed in Algorithm 1.

Algorithm 1 PDC-DP-Medians

The following definitions will be for a single genomic window. The cost function of PDC-DP-Medians for K haplotype clusters is defined as:

where xh ∈ {0, 1}B is the h-th haplotype, ck ∈ {0, 1}B is the k-th cluster median, zh ∈ {1, …, K} is the haplotype cluster assignment of the h-th haplotype for h = 1, …, 2N and ∥ ⋅ ∥1 being the L1-norm. The added penalty term penalizes the creation of clusters, and a new cluster will be generated if the Manhattan distance exceeds the specified λ parameter. We utilize the delayed cluster creation process introduced in PDC-DP-Means, where only one new cluster can be created per epoch, which allows for a fast parallelized implementation of the algorithm.

For extending the median to multiple dimensions, we use the marginal median to define cluster medians, where each component in the multivariate median is defined as a simple univariate median, and it is thus fast to compute for binary genetic data. An example for the j-th SNP in ck:

with \({\mathbb{I}}\left[\cdot \right]\) being the indicator function, \({\theta }_{kj}=\frac{1}{{n}_{k}}{\sum }_{h:{z}_{h}=k}{x}_{hj}\) being the mean of the haplotypes assigned to the k-th cluster for SNP j and nk the number of haplotypes assigned to cluster k. We initialize the algorithm with K = 1 and the first cluster median c1 being the marginal median considering all haplotypes such that zh = 1 for h = 1, …, 2N. The next cluster creation step after initialization is then defined as finding the haplotype with the maximum distance to its assigned cluster, and if the distance exceeds λ, the corresponding haplotype is set as a new cluster. The process is iterated until the haplotype cluster assignment step converges, and we have set λ = 0.1 for all analyses in our study. The computational complexity for performing haplotype clustering in a single window will be \({{\mathcal{O}}}(NBK)\).

When a window size of B = 1 is chosen, our algorithm naturally collapses to single SNP clusters representing the two alleles. We exclude rare haplotype clusters below a frequency threshold of δ = 0.01 in an iterative post-hoc re-clustering procedure, where haplotypes belonging to an excluded cluster will be reassigned to the next best cluster. We describe the procedure in Supplementary Algorithm 1 in Supplementary Methods. This step increases the computational runtime of our algorithm but ensures that all haplotypes are represented by and assigned to valid clusters, thus retaining information. λ and δ can be seen as smoothing hyperparameters that affect granularity, as they govern how many haplotype clusters will be generated and retained, respectively.

The haplotype cluster medians can further be used to infer cluster assignments of unseen haplotypes on the same set of variants. The unseen haplotypes will be assigned to the cluster median with the smallest Manhattan distance, allowing for some degree of missingness.

Genome-wide relationship matrix

The haplotype cluster assignment of a single haplotype h in window w is one-hot encoded such that \({{{\bf{z}}}}_{h}^{(w)}\in {\{0,1\}}^{K}\), with the k-th entry as 1 and 0 otherwise for \({z}_{h}^{(w)}=k\). We define a new matrix A(w) ∈ {0, 1, 2}N×K, which represents the aggregated haplotype cluster assignments for each individual, where \({a}_{ik}^{(w)}={z}_{hk}^{(w)}+{z}_{(h+1)k}^{(w)}\) for the i-th individual with its maternal and paternal haplotypes (h and h+1) in the w-th window, for k = 1, …, K. We will refer to A = [A(1), …, A(W)] as the full haplotype cluster allele matrix, which can span multiple chromosomes. Thereby in comparison to standard genetic data, we have changed the input unit from minor allele counts of SNPs (genotypes) to haplotype cluster allele counts. Note that each genomic window w has had an assumed fixed number of K haplotype clusters for simple notation, however in practice, K will vary in each window.

We define a general approach for estimating the GRM, \({{\bf{R}}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{N\times N}\), with our haplotype cluster allele matrix. The pairwise entry of individual i and j is defined as follows:

where \({\pi }_{k}^{(w)}\) represents the haplotype cluster allele frequency of the k-th haplotype cluster in window w and \(D=2{\sum }_{w=1}^{W}\mathop{\sum }_{k=1}^{K}{\pi }_{k}^{(w)}\left(1-{\pi }_{k}^{(w)}\right)\) scales R to be analogous to the numerator relationship matrix51. We further perform data and Gower centering on R to obtain accurate heritability estimates52 in the following approach.

Reference-free polygenic prediction is based on the BLUP from an LMM, using the GRM estimated above, such that a phenotype \({{\bf{y}}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{N}\) is modeled as a mixture of fixed and random effects using all SNPs, or in our case haplotype cluster alleles, jointly:

Here \({{\bf{P}}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{N\times Q}\) is a matrix of Q covariates, including inferred eigenvectors, with γ as the corresponding fixed effects, \({{\bf{g}}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{N}\) is a vector of the genetic effects, or polygenic scores, of the individuals with \({{\bf{g}}} \sim N\left(0,{{\bf{R}}}{\sigma }_{g}^{2}\right)\) and \({{\boldsymbol{\epsilon }}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{N}\) is a vector of residual effects with \({{\boldsymbol{\epsilon }}} \sim N\left(0,{{\bf{I}}}{\sigma }_{\epsilon }^{2}\right)\). The LMM can be extended to include genetic effects from multiple GRMs53,54 that each models different partitions of the data. The phenotype will therefore be modeled as

using S different GRMs with \({{{\bf{g}}}}_{s} \sim N\left(0,{{{\bf{R}}}}_{s}{\sigma }_{s}^{2}\right)\). For our haplotype-cluster approach, it will be GRMs estimated from haplotype clusters inferred from different window sizes. The variance components are estimated using GREML, and we define \({\sigma }_{g}^{2}={\sum }_{s=1}^{S}{\sigma }_{s}^{2}\).

Polygenic prediction

Reference-free polygenic prediction is implicitly performed using the GREML approach above to provide polygenic predictions in the target population with \({{\bf{g}}}=\mathop{\sum }_{s=1}^{S}{{{\bf{g}}}}_{s}\), where gs represents the predictions from the s-th partition. Importantly, we compute leave-one-out cvBLUP to avoid overfitting and biased estimates of the polygenic scores28, which allows for direct and useful predictions in the target population. We use GCTA (v1.94.1) to estimate the variance components for SNP heritability and cvBLUPs using flags –reml, –reml-no-constrain, –cvblup and –mgrm to include multiple GRMs.

Reference-based polygenic prediction is estimated using external GWAS summary statistics. We use PRSice (v2.3.5)12 to estimate PRSs based on a clumping and thresholding (C+T) approach using its default parameters that optimizes for R2 directly in the target dataset.

Implementation details

We have implemented our method in a fast and multithreaded command-line software, hapla, which is written in Cython (v3.0) and Python (v3.11). The software takes phased genotype data as input in VCF/BCF format using the cyvcf2 (v0.30) Python library55, which is read into NumPy (v1.26) arrays56 for fast array manipulation. The phased genotype data is read into 1-byte arrays such that the memory requirement is approximately NM bytes, which makes the haplotype clustering in the hapla software scalable to modern biobank sample sizes.

The output files of our software are either in binary NumPy format, binary PLINK format, or binary GCTA format for fast and easy integration into existing pipelines. The haplotype cluster medians can be saved as a binary array collection, such that they can easily be utilized to cluster unseen haplotypes of an independent phased genotype dataset. The software is open source and freely available at https://github.com/Rosemeis/hapla. All results generated in this study are based on hapla v0.11.

Simulated data

We simulate human genetic data based on a two populations out-of-Africa demographic model (‘‘OutOfAfrica_2T12’’)57,58 in the stdpopsim (v0.2) library59 using the msprime (v1.2.0) simulation engine60. The simulated data is used to evaluate hapla in estimating heritability and performing polygenic prediction in a realistic scenario including populations of different genetic architectures. The demographic model is visualized in Supplementary Fig. 1, and we simulate a total of 20,000 individuals with 10,000 from each of the two populations of different ancestry, African (AFR) and European (EUR). A chromosomal segment of 100Mb is simulated using a constant recombination rate of 1.28 × 10−8 and mutation rate of 2.36 × 10−8. We split the data into three subsets, AFR (N = 10,000), EUR (N = 10,000), and ALL (N = 20,000), where ALL represents a structured population containing all individuals. msprime simulates entire chromosomal segments such that the phasing information is known in the assembly of all diploid individuals. After minor allele frequency (MAF) filtering at a threshold of 0.01, we have 425,903 SNPs, 223,407 SNPs, and 388,746 SNPs, respectively, in the three subsets emulating whole-genome sequencing data with full information. The AFR subset has a larger number of SNPs, reflecting the increased genetic diversity in comparison to the EUR subset, as the EUR population underwent a severe bottleneck in the out-of-Africa event as defined in the demographic model.

We create downsampled datasets of the three subsets, where we downsample the SNP set by a factor of 10 to remove information that would potentially not be available in real datasets due to imperfect imputation or relying on SNP array data. We create 10 equally sized MAF bins from 0.01 to 0.5 and sample uniformly from each, which emulates a scenario where we have proportionally more frequent SNPs similar to SNP array data or imputed data in comparison to sequencing data. The downsampled datasets therefore only include 42,600, 22,350, and 38,880 SNPs for AFR, EUR, and ALL, respectively.

Additionally, we create LD pruned subsets of all mentioned datasets to evaluate a standard genotype-based method in which LD pruning has been performed. LD pruning is a common procedure to reduce the computational burden in LMMs and principal component analysis (PCA)43. It removes correlated SNPs in close proximity61, and we perform standard LD pruning using PLINK (v2.00a)62 with flag ‘–indep-pairwise 50 10 0.5’.

A complete overview of the generated simulated datasets is listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Phenotype simulations

We simulate phenotypes of complex traits in the simulated data for three different scenarios. We follow the simple approach in14, where we randomly sample Mc = 1000 causal variants from the full SNP sets. Causal effects are assumed to be independent and sampled from a Gaussian distribution, \({\beta }_{j} \sim N\left(0,\frac{{h}^{2}}{{M}_{c}}\right)\), for j = 1, …, Mc, where h2 is the narrow-sense heritability. The genetic liability of the trait for individual i is defined as an additive model of the causal variants such that

with αij being the genotype at the j-th causal variant. Environmental noise is sampled from a Gaussian distribution, ϵi ~ N(0, 1 − h2), and the phenotype of an individual i is then generated by \({y}_{i}={\bar{g}}_{i}+{\bar{\epsilon }}_{i}\). Here \({\bar{g}}_{i}\) and \({\bar{\epsilon }}_{i}\) represent scaled versions of gi and ϵi, which ensure that their variances are h2 and 1 − h2, respectively. We simulate SNP-based phenotypes using two different h2, which are 0.8 (Scenario 1) and 0.2 (Scenario 2). We also simulate phenotypes of quantitative traits using haplotype cluster alleles for h2 = 0.8 to demonstrate that our approach using haplotype clusters is unbiased (Scenario 3). We use haplotype clusters inferred from overlapping windows using B = 8.

Phenotypes are simulated independently in each generated dataset to ensure a correct scaling of the genetic liabilities and environmental noise. Each simulation scenario is replicated 10 times to account for sampling bias, and the results are reported with mean and standard deviation across the 10 replications.

iPSYCH2012 case-cohort

Research using the iPSYCH has been approved by the Danish Scientific Ethics Committee, the Danish Health Data Authority, and the Danish Data Protection Agency. The consent structure of iPSYCH, as governed by the Act on Research Ethics Review of Health Research Projects in Denmark, is exempted from obtaining informed consent from human research participants (https://ipsych.dk/en/data-security/health-research-and-ethical-approval/). iPSYCH2012 is a Danish population-based case-cohort of individuals with mental disorders and population controls38. The iPSYCH2012 case-cohort consists of selected Danish individuals born between 1981 and 2005, where dry blood spots have been taken at birth and have been genotyped on an Infininium PsychChip v1.0 array containing a large proportion of SNPs associated with psychiatric disorders. The population controls are part of a large random sample of individuals from the Danish population and can therefore have any of the disorders by chance. The array data of the iPSYCH2012 case-cohort has recently been phased and imputed using the Haplotype Reference Consortium v1.163. We utilize the phased and imputed genotype data to estimate heritability and perform polygenic prediction for MDD, REC, and SCZ using our inferred haplotype clusters. MDD is here defined by the 10th revision of International Classification of Disease (ICD-10)64 codes F32 and F33, whereas REC is a subtype of MDD (F33 only) and SCZ is defined by the ICD-10 code F20. All three disorders are analyzed independently, and population controls with a diagnosis of the given disorder in the Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register65 are then classified as cases in the respective analyzes, and the population controls will therefore differ between the disorders. We only consider individuals who are active, alive, and residents in Denmark at the end of 2016 from where we also calculate their respective ages.

We filter out SNPs deviating from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium with p < 1.0 × 10−6 as well as using an imputation quality filter of DR2 ≤0.95 to estimate kinship coefficients using KING-robust66, implemented in PLINK, while pooling population controls and cases from all three disorders. We remove related individuals up to second-degree (0.0884) while keeping individuals in the related pairs that maximize the overall sample size. Using these definitions, we have 20,620 cases with a MDD diagnosis, 7128 cases with a REC diagnosis, 3211 cases with a SCZ diagnosis, and 25,228, 25,840, and 25,994 population controls in the three datasets, respectively. Hereafter we filter out SNPs with MAF <0.01 and we provide a full overview of the number of SNPs in the three datasets in Supplementary Table 3. We use a population life-time disease prevalence of 0.12285 for MDD, 0.05700 for REC, and 0.01745 for SCZ7,67 to convert SNP heritability estimates on the observed scale to the liability scale68. We infer the top 20 principal components using the PCAone (v0.4.2) software69, which is used to correct for population structure in downstream analyzes.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The simulated datasets generated in this study have been deposited on Figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26003419. In accordance with the Danish law and consent permissions governing iPSYCH, the individual-level genotype data from the iPSYCH2012 case-cohort can not be shared publicly. The data is hosted on GenomeDK and available to researchers involved with the consortium. The iPSYCH2012 case-cohort study was approved by the Danish Scientific Ethics Committee, the Danish Health Data Authority, and the Danish Data Protection Agency. Further information on iPSYCH data security can be found here: https://ipsych.dk/en/data-security, the ethical approval statement is available here: https://ipsych.dk/en/data-security/health-research-and-ethical-approval. Source data underlying figures are provided in a Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The hapla software is freely available on GitHub at https://github.com/Rosemeis/haplaunder a GNU GPL v3.0 license. hapla v0.11 is used in the entire study and is also independently available on Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14176691. Scripts are available in both repositories for reproducing data and the results of the simulation study.

References

Torkamani, A., Wineinger, N. E. & Topol, E. J. The personal and clinical utility of polygenic risk scores. Nat. Rev. Genet. 19, 581–590 (2018).

Kachuri, L. et al. Principles and methods for transferring polygenic risk scores across global populations. Nat. Rev. Genet. 25, 8–25 (2023).

Murray, G. K. et al. Could polygenic risk scores be useful in psychiatry? A review. JAMA Psychiatry 78, 210–219 (2021).

Ikeda, M., Saito, T., Kanazawa, T. & Iwata, N. Polygenic risk score as clinical utility in psychiatry: a clinical viewpoint. J. Hum. Genet. 66, 53–60 (2021).

Lépine, J.-P. & Briley, M. The increasing burden of depression. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 7, 3–7 (2011).

Charlson, F. J. et al. Global epidemiology and burden of schizophrenia: findings from the global burden of disease study 2016. Schizophr. Bull. 44, 1195–1203 (2018).

Pedersen, C. B. et al. A comprehensive nationwide study of the incidence rate and lifetime risk for treated mental disorders. JAMA Psychiatry 71, 573–581 (2014).

Als, T. D. et al. Depression pathophysiology, risk prediction of recurrence and comorbid psychiatric disorders using genome-wide analyses. Nat. Med. 29, 1832–1844 (2023).

Trubetskoy, V. et al. Mapping genomic loci implicates genes and synaptic biology in schizophrenia. Nature 604, 502–508 (2022).

Albiñana, C. et al. Leveraging both individual-level genetic data and gwas summary statistics increases polygenic prediction. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 108, 1001–1011 (2021).

Vilhjálmsson, B. J. et al. Modeling linkage disequilibrium increases accuracy of polygenic risk scores. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 97, 576–592 (2015).

Choi, S. W. & O’Reilly, P. F. Prsice-2: polygenic risk score software for biobank-scale data. Gigascience 8, giz082 (2019).

Mak, T. S. H., Porsch, R. M., Choi, S. W., Zhou, X. & Sham, P. C. Polygenic scores via penalized regression on summary statistics. Genet. Epidemiol. 41, 469–480 (2017).

Martin, A. R. et al. Human demographic history impacts genetic risk prediction across diverse populations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 100, 635–649 (2017).

Keys, K. L. et al. On the cross-population generalizability of gene expression prediction models. PLoS Genet. 16, e1008927 (2020).

Chen, S.-F. et al. Genotype imputation and variability in polygenic risk score estimation. Genome Med. 12, 1–13 (2020).

Patel, R. A. et al. Genetic interactions drive heterogeneity in causal variant effect sizes for gene expression and complex traits. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 109, 1286–1297 (2022).

Ding, Y. et al. Polygenic scoring accuracy varies across the genetic ancestry continuum. Nature 618, 774–781 (2023).

Sohail, M. et al. Polygenic adaptation on height is overestimated due to uncorrected stratification in genome-wide association studies. Elife 8, e39702 (2019).

Refoyo-Martínez, A. et al. How robust are cross-population signatures of polygenic adaptation in humans? Peer Community J. 1, e22 (2021).

Sakaue, S. et al. Dimensionality reduction reveals fine-scale structure in the Japanese population with consequences for polygenic risk prediction. Nat. Commun. 11, 1569 (2020).

Yang, J. et al. Common snps explain a large proportion of the heritability for human height. Nat. Genet. 42, 565–569 (2010).

Yang, J., Lee, S. H., Wray, N. R., Goddard, M. E. & Visscher, P. M. Gcta-greml accounts for linkage disequilibrium when estimating genetic variance from genome-wide SNPs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, E4579–E4580 (2016).

Kang, H. M. et al. Efficient control of population structure in model organism association mapping. Genetics 178, 1709–1723 (2008).

Loh, P.-R., Kichaev, G., Gazal, S., Schoech, A. P. & Price, A. L. Mixed-model association for biobank-scale datasets. Nat. Genet. 50, 906–908 (2018).

Yang, J., Lee, S. H., Goddard, M. E. & Visscher, P. M. Gcta: a tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 88, 76–82 (2011).

Robinson, G. K. That blup is a good thing: the estimation of random effects. Stat. Sci. 15–32 (1991).

Mefford, J. et al. Efficient estimation and applications of cross-validated genetic predictions to polygenic risk scores and linear mixed models. J. Comput. Biol. 27, 599–612 (2020).

Lawson, D. J., Hellenthal, G., Myers, S. & Falush, D. Inference of population structure using dense haplotype data. PLoS Genet. 8, e1002453 (2012).

Meisner, J. & Albrechtsen, A. Haplotype and population structure inference using neural networks in whole-genome sequencing data. Genome Res. 32, 1542–1552 (2022).

Maples, B. K., Gravel, S., Kenny, E. E. & Bustamante, C. D. Rfmix: a discriminative modeling approach for rapid and robust local-ancestry inference. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 93, 278–288 (2013).

Bhatia, G. et al. Haplotypes of common snps can explain missing heritability of complex diseases. Biorxiv 022418 (2015).

Utsunomiya, Y. T., Milanesi, M., Utsunomiya, A. T., Ajmone-Marsan, P. & Garcia, J. F. Ghap: an r package for genome-wide haplotyping. Bioinformatics 32, 2861–2862 (2016).

Won, S. et al. Genomic prediction accuracy using haplotypes defined by size and hierarchical clustering based on linkage disequilibrium. Front. Genet. 11, 134 (2020).

Powell, J. E., Visscher, P. M. & Goddard, M. E. Reconciling the analysis of ibd and ibs in complex trait studies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11, 800–805 (2010).

Zaitlen, N. et al. Leveraging population admixture to characterize the heritability of complex traits. Nat. Genet. 46, 1356–1362 (2014).

Wang, Y. et al. Polygenic prediction across populations is influenced by ancestry, genetic architecture, and methodology. Cell Genomics 3, 10 (2023).

Pedersen, C. B. et al. The ipsych2012 case–cohort sample: new directions for unravelling genetic and environmental architectures of severe mental disorders. Mol. Psychiatry 23, 6–14 (2018).

Lee, S. H., Goddard, M. E., Wray, N. R. & Visscher, P. M. A better coefficient of determination for genetic profile analysis. Genet. Epidemiol. 36, 214–224 (2012).

Momin, M. M., Lee, S., Wray, N. R. & Lee, S. H. Significance tests for R2 of out-of-sample prediction using polygenic scores. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 110, 349–358 (2023).

Howard, D. M. et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis of depression identifies 102 independent variants and highlights the importance of the prefrontal brain regions. Nat. Neurosci. 22, 343–352 (2019).

Yang, J. et al. Genetic variance estimation with imputed variants finds negligible missing heritability for human height and body mass index. Nat. Genet. 47, 1114–1120 (2015).

Loh, P.-R. et al. Contrasting genetic architectures of schizophrenia and other complex diseases using fast variance-components analysis. Nat. Genet. 47, 1385–1392 (2015).

Zhang, Q., Privé, F., Vilhjálmsson, B. & Speed, D. Improved genetic prediction of complex traits from individual-level data or summary statistics. Nat. Commun. 12, 4192 (2021).

Privé, F., Aschard, H. & Blum, M. G. Efficient implementation of penalized regression for genetic risk prediction. Genetics 212, 65–74 (2019).

Privé, F. Optimal linkage disequilibrium splitting. Bioinformatics 38, 255 (2022).

Ruan, Y. et al. Improving polygenic prediction in ancestrally diverse populations. Nat. Genet. 54, 573–580 (2022).

Kulis, B. & Jordan, M. I. Revisiting k-means: new algorithms via Bayesian nonparametrics. In Proc. 29th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML, 2012).

Dinari, O. & Freifeld, O. Revisiting dp-means: fast scalable algorithms via parallelism and delayed cluster creation. In Proc. 38th Conference on Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence (PMLR, 2022).

Bradley, P., Mangasarian, O. & Street, W. Clustering via concave minimization. In Proc. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 9 (NIPS, 1996).

VanRaden, P. M. Efficient methods to compute genomic predictions. J. Dairy Sci. 91, 4414–4423 (2008).

Zhang, B. C., Biddanda, A., Gunnarsson, Á. F., Cooper, F. & Palamara, P. F. Biobank-scale inference of ancestral recombination graphs enables genealogical analysis of complex traits. Nat. Genet. 55, 768–776 (2023).

Yang, J. et al. Genome partitioning of genetic variation for complex traits using common snps. Nat. Genet. 43, 519–525 (2011).

Speed, D. & Balding, D. J. Multiblup: improved snp-based prediction for complex traits. Genome Res. 24, 1550–1557 (2014).

Pedersen, B. S. & Quinlan, A. R. cyvcf2: fast, flexible variant analysis with python. Bioinformatics 33, 1867–1869 (2017).

Harris, C. R. et al. Array programming with numpy. Nature 585, 357–362 (2020).

Tennessen, J. A. et al. Evolution and functional impact of rare coding variation from deep sequencing of human exomes. Science 337, 64–69 (2012).

Fu, W. et al. Analysis of 6515 exomes reveals the recent origin of most human protein-coding variants. Nature 493, 216–220 (2013).

Adrion, J. R. et al. A community-maintained standard library of population genetic models. Elife 9, e54967(2020).

Kelleher, J., Etheridge, A. M. & McVean, G. Efficient coalescent simulation and genealogical analysis for large sample sizes. PLoS Comput. Biol. 12, e1004842 (2016).

Mathew, B., Léon, J. & Sillanpää, M. J. A novel linkage-disequilibrium corrected genomic relationship matrix for snp-heritability estimation and genomic prediction. Heredity 120, 356–368 (2018).

Chang, C. C. et al. Second-generation plink: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. Gigascience 4, s13742–015 (2015).

Appadurai, V. et al. Accuracy of haplotype estimation and whole genome imputation affects complex trait analyses in complex biobanks. Commun. Biol. 6, 101 (2023).

WHO. The ICD-10 Classification Of Mental And Behavioural Disorders: Diagnostic Criteria For Research, 2 (World Health Organization, 1993).

Mors, O., Perto, G. P. & Mortensen, P. B. The Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register. Scand. J. Public Health 39, 54–57 (2011).

Manichaikul, A. et al. Robust relationship inference in genome-wide association studies. Bioinformatics 26, 2867–2873 (2010).

Schork, A. J. et al. A genome-wide association study of shared risk across psychiatric disorders implicates gene regulation during fetal neurodevelopment. Nat. Neurosci. 22, 353–361 (2019).

Lee, S. H., Wray, N. R., Goddard, M. E. & Visscher, P. M. Estimating missing heritability for disease from genome-wide association studies. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 88, 294–305 (2011).

Li, Z., Meisner, J. & Albrechtsen, A. Fast and accurate out-of-core PCA framework for large scale biobank data. Genome Res. 33, 1599–1608 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by unrestricted grants from the Lundbeck Foundation (R380-2021-1225, J.M., and R278-2018-1411, M.E.B.) and the Novo Nordisk Foundation (NNF14CC0001 and NNF23SA0084103, S.R.). The genotyping of the iPSYCH samples was supported by grants from the Lundbeck Foundation (R102-A9118 and R155-2014-1724), the Stanley Foundation, the Simons Foundation (SFARI 311789), and NIMH (5U01MH094432-02). The funding sources had no role in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript or the decision to submit it for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.M. has conceived the study and derived the method. J.M. has implemented the method and performed the analyses. S.R. and M.E.B. have supervised the study. All authors have contributed to the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

S.R. is the founder and owner of BioAI. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Shing Wan Choi who co-reviewed with Lei Chen; and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Meisner, J., Benros, M.E. & Rasmussen, S. Leveraging haplotype information in heritability estimation and polygenic prediction. Nat Commun 16, 126 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-55477-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-55477-3

This article is cited by

-

Advances in haplotype phasing and genotype imputation

Nature Reviews Genetics (2026)