Abstract

Axonal fusion represents an efficient way to recover function after nerve injury. However, how axonal fusion is induced and regulated remains largely unknown. We discover that ferroptosis signaling can promote axonal fusion and functional recovery in C. elegans in a dose-sensitive manner. Ferroptosis-induced lipid peroxidation enhances injury-triggered phosphatidylserine exposure (PS) to promote axonal fusion through PS receptor (PSR-1) and EFF-1 fusogen. Axon injury induces PSR-1 condensate formation and disruption of PSR-1 condensation inhibits axonal fusion. Extending these findings to mammalian nerve repair, we show that loss of Glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4), a crucial suppressor of ferroptosis, promotes functional recovery after sciatic nerve injury. Applying ferroptosis inducers to mouse sciatic nerves retains nerve innervation and significantly enhances functional restoration after nerve transection and resuture without affecting axon regeneration. Our study reveals an evolutionarily conserved function of lipid peroxidation in promoting axonal fusion, providing insights for developing therapeutic strategies for nerve injury.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Damage to the central nervous system (CNS) often causes lifelong morbidity and the functional recovery requires re-establishing the lost connections. Regenerative axonal fusion provides an efficient repair mechanism to achieve reconnection1. Axonal fusion was first reported in Procambarus clarkii in 19672 and has then been observed in various organisms3,4,5,6, including Caenorhabditis elegans7. Although axonal fusion has not been directly demonstrated in mammals, fusion-inducing mechanisms has been used to promote nerve repair in mammals1. Chemical fusogen polyethylene glycol (PEG) has been shown to be effective to promote functional recovery after nerve injury in both peripheral nerve and spinal cord injury in mammalian animal models8,9,10,11,12,13,14.

Axonal fusion is metabolically efficient because it only requires a single connection with the distal axon to the target tissue without reconstructing the entire peripheral terminals from the detached part to the target tissue2. It has been shown that axonal fusion of C. elegans mechanosensory neurons is mediated by EFF-1 fusogen15 and requires apoptotic pathway components16, and that let-7 miRNA inhibits axonal fusion by reducing CED-7 expression17. Axonal fusion is initiated with the exposure of phosphatidylserine (PS) to the outer membrane to serve as a recognition signal1. Exposed PS is then bound by both secreted and transmembrane proteins that mediate interactions between the injured distal segment and the regrowing segment, mechanistically mimicking the process of apoptotic cell death16,18. Despite decades of research, the molecular mechanisms behind axonal fusion are still elusive.

Unlike apoptosis, ferroptosis is an iron-dependent cell death triggered by severe membrane lipid peroxidation (LPO), which relies on ROS generation19. LPO occurs when oxidants such as free radicals or non-radical species attack lipids containing carbon-carbon double bonds20. This process is initiated with prooxidant like hydroxyl radical (HO•) abstract the allylic hydrogen forming the carbon-centered lipid radical (L•). Lipid radical then rapidly reacts with oxygen to form a lipid peroxyl radical (LOO•) which abstracts hydrogen from another lipid molecule generating new lipid radicals and lipid hydroperoxide (LOOH)20,21. Glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) is an endogenous suppressor of ferroptosis that limits peroxidation by catalyzing the glutathione (GSH)-dependent reduction of lipid hydroperoxides to lipid alcohols (LOH) and water (H2O)22. Various GPX4 inhibitors, including RSL323, ML16224, and ML21025, can increase the production of lipid ROS, thereby inducing ferroptosis.

Biomolecular condensation has emerged as a crucial mechanism driving cellular organization and diverse biological functions26. These phase-separated biomolecular condensates form specialized compartments devoid of a surrounding membrane. Notably, condensation processes extend to membrane interfaces27,28,29,30, where they influence the genesis and behavior of condensates by either acting as assembly platforms or establishing direct interactions. Recent research underscores the involvement of biomolecular condensates in various membrane-associated events, including focal adhesions and vesicle fusion31. But it has not been explored whether axonal fusion involves biomolecular condensation.

Here, we report an evolutionarily conserved function of lipid peroxidation in promoting axonal fusion. We show that mutations in gpx genes in C. elegans either promotes axonal fusion or leads to increased axonal debris. Similarly, treatment with GSH synthesis inhibitors or GPX4 inhibitors can impact the regenerative response after axon injury in a dose-sensitive manner, with a low dose promoting axonal fusion and a high dose causing axonal debris. We further show that ferroptosis signaling enhances injury-triggered PS exposure, which promotes axonal fusion in a PS receptor (PSR-1) and EFF-1 fusogen-dependent manner. We demonstrate that PSR-1 forms condensates in vitro and in vivo and that the biophysical properties of PSR-1 condensates can be altered by hydrogen peroxide and DTT. Furthermore, applying ferroptosis inducer ML162 in a mouse injury model significantly enhances functional recovery after sciatic nerve transection without affecting axon regeneration. The neuromuscular junction (NMJ) at the ipsilateral plantar muscles was detected in ML162-treated animals 3 days post-operation, when NMJ has degenerated in untreated animals, indicating ML162-induced axonal fusion. Enhanced functional restoration was also detected in GPX4 cKO mice after sciatic nerve injury. Thus, our study reveals a mechanism of axonal fusion and identifies compounds that might be used to facilitate functional recovery after nerve injury.

Results

gpx loss-of-function affects the regenerative response of injured neurons

We have previously shown that injury-induced autophagy promotes axon regeneration through degrading notch receptors (NOTCH)32. Given the emerging evidence supporting the crosstalk between autophagy and ferroptosis33,34,35, we sought to test whether ferroptosis pathway is involved in axon regeneration by examining axon regrowth in available loss-of-function mutants of C. elegans gpx genes, which are homologous to human GPX genes36 Fig. 1A, B). We assayed axon regrowth in vivo using touch sensory PLM neurons, a well-established model for axon regeneration37,38. Touch neuron-specific reporter alleles muIs32 (Pmec-7::GFP) and zdIs5 (Pmec-4::GFP) were used to label the touch sensory neurons for morphological analysis and single-neuron laser axotomy. We performed axotomy at Day 1 young adult stage and measured axon regrowth 24 h post-injury. As GPX4 is known to suppress ferroptosis, an iron-dependent and ROS-reliant cell death39 (Fig. 1A), we expected to see reduced axon regeneration in gpx mutants. However, we observed a high frequency of axonal fusion, with the amputated proximal axons reconnected with the distal segment, in gpx-3(tm2059), gpx-5(tm2024), and gpx-8(tm2108) mutants (Fig. 1C–F). This enhanced axonal fusion frequency was not found in gpx-1(tm2100), gpx-4(tm2111), and gpx-7(2166). Instead, a significant number of gpx-1(tm2100) and gpx-4(tm2111) animals displayed debris-like structures around the regenerative growth cone (Fig. 1E, G). These debris-like structures displayed similar morphology as previously reported axon debris, the removal of which by CED-1-mediated cell engulfment is critical for axon regeneration post injury40. The distinct phenotypes in mutants of different gpx genes might be due to differential GPX activities and lipid oxidation levels in these mutants.

A Schematic diagram showing the ferroptosis pathway. B Illustration of protein structures of human GPx4 protein and C. elegans GPX proteins. The listed human homologues of C. elegans GPX proteins were identified based on information provided by the WormBase (https://wormbase.org). C–G Representative images and quantification of PLM axonal fusion and debris phenotypes at 24 h post laser axotomy in the genetic mutants of indicated gpx genes. The dotted box indicates the same region as the zoomed-in image on the right, which displays a different focal plane. Axon was visualized by touch neuron-specific GFP expression driven by Pmec-7. Quantification of axonal fusion (H) and debris-like structure (I) in worm strains with indicated genotypes. The index scores were calculated by normalizing to WT control. For instance, if the fusion rate in WT animals is 10% and the fusion rates of gpx-1 mutants in 3 different experiments are 20%, 25% and 30%, then the fusion index of gpx-1 mutant is the average of 20%/10%, 25%/10% and 30%/10% [Fusion Index = (2 + 2.5 + 3)/3 = 2.5]. Quantification of axonal fusion (J, L and N) and debris-like structure (K, M and O) in worm strains with indicated genotypes. Scale bar: 20 µm. Statistics: One-way ANOVA or Student’s t-tests; mean ± SEM. The total animals of each condition (total number indicated above or in each bar) were randomly divided into 2 or 3 groups for statistical analyses. Source data of all figures are provided as a Source Data file.

To examine whether gpx genes regulate axonal fusion cell-autonomously, we generated touch neuron-specific GPX transgenes in gpx mutant background. The enhanced axonal fusion frequency in gpx-5 mutants was rescued by touch neuron-specific GPX-5 expression (Fig. 1H), indicating a cell-autonomous function of GPX-5. Furthermore, transgenic expression of GPX-1 or GPX-4 was sufficient to rescue the fusion phenotype in gpx-5 mutants (Fig. 1H), suggesting conserved function among GPX paralogs. The axon debris phenotype in gpx-1 and gpx-4 mutants was also rescued by transgenic GPX-1 and GPX-4 expression in touch neurons (Fig. 1I). These data suggest that gpx genes act within touch neurons to impact the injury response. When human GPX4 was expressed in touch neurons, it was sufficient to suppress ML162-induced axonal fusion (Fig. 1J, K). Similarly, the axonal fusion and debris phenotypes in gpx-5 and gpx-1 mutants respectively was suppressed by human GPX4 (Fig. 1L–O), indicating an evolutionally conserved function of GPX protein.

Ferroptosis-inducing drugs promote axonal fusion in a dose-dependent manner

Having shown that mutations of gpx genes promoted axonal fusion, we next tested ferroptosis-inducing agents (Fig. 2A) for their effects on axonal fusionML162, ML210, and RSL3 are small molecules that inactivate GPX4 to induce ferroptosis41. We found that low doses (ML162, ML210 and RSL3) of ferroptosis-inducing agents significantly improved axonal reconnection, with a much higher frequency of regenerated axons fused to the distal fragments (Fig. 2B). This fusion-promoting effect was observed in both reporter strains with either muIs32 or zdIs5 allele (Fig. 2B–D). ML162-induced axonal fusion was also found in ALM mechanosensory neurons (Fig. 2E, F).

A Schematic diagram showing the ferroptosis inhibitor Fer-1 and ferroptosis inducers at their functional points in the pathway and their roles in regulating lipid peroxidation. B–D Representative images and quantification of axonal fusion at 24 h post laser axotomy in the reporter strains with indicated treatments showing that ferroptosis inducers can promote axonal fusion. E, F Representative images and quantification of axonal fusion at 24 h post laser axotomy in ALM axon with indicated treatments. G Representative images of a fused PLM axon (labeled with Pmec-7::GFP) 24 h post axotomy and kymographs showing synaptic vesicles (labeled with Pmec-4::mCherry::RAB-3) moving across the fusion site. The zoomed-in images of the boxed regions on the kymograph are on the right. The dashed line marks the fusion site, and the arrows point to the vesicles moving across the dashed line. H Touch sensitivity assay showing that ML162-induced axonal fusion improved touch response. The numbers of responses to 10 posterior touches were quantified. I Representative images of axonal debris at 24 h post laser axotomy in WT strain treated with a high dose of ferroptosis inducers. J, K Quantification of axonal fusion and debris rates of animals treated with different concentrations of ferroptosis inducers. Low doses of inducers promote axonal fusion, while high doses lead to axonal debris. L Representative images showing that ML162 and RSL3-induced axonal fusion can be suppressed by ferroptosis inhibitor Fer-1. M, N Quantification of axonal fusion rates in the two reporter strains with indicated treatments. Dashed line in the graphs indicates the average percentage of axonal fusion in animals treated with ferroptosis-inducing agents. The induced axonal fusion can be suppressed by Ferrostatin-1. Scale bar: 20 µm. The dotted box marks the tip of the regenerative axon, and a zoomed-in image of the region is presented on the right or below. The total animals of each condition (total number indicated above or in each bar) except for (H) were randomly divided into 2 or 3 groups for statistical analyses. Statistics: One-way ANOVA or Student’s t-tests; mean ± SEM.

To determine whether the ferroptosis-induced axonal fusion is functional, we examined vesicle trafficking across the fusion site. We expressed mCherry-tagged RAB-3 in touch neurons (Pmec-4::mcherry::rab-3) to label synaptic vesicles17. We observed both anterograde and retrograde motion of RAB-3-labelled vesicles across the connection site in the PLM of ML162 treated animals (Fig. 2G), indicating that ferroptosis signaling-induced axonal fusion is functional and can support intracellular transport. We further assessed functional recovery of the fused PLM axons post axotomy using the touch sensitivity assay42. We performed laser axotomy in Day 1 adult animals (24 h post L4 stage) treated with ML162 and tested touch sensitivity 24 h post injury, immediately followed by assessment of axon regrowth status. In the mock control group, in which animals received mock laser surgery but not axotomy, they responded to nearly 100% of light touches at the tail region. In the axotomy group, animals with axon regrowth but no axonal fusion responded to 6 out of 10 posterior gentle touches on average, while animals with axonal fusion showed a significantly improved response rate compared to those without fusion (Fig. 2H). Taken together, these data suggest that ferroptosis-induced axonal fusion is functional and can restore the neural circuit. We noticed that the effects of ferroptosis agents were dose dependent. When we treated the animals with a higher dose of ML162, we observed a reduced fusion rate compared to the lower dose treatment (Fig. 2I–K). In the high dose group, we also observed debris structures around the terminal of a regenerative axon, which was often near the injury site due to the limited axonal regrowth (Fig. 2I–K). The debris structures were similar to those found in gpx-1(tm2100) and gpx-4(tm2111) mutants (Fig. 1D–G). As low dose of ferroptosis-inducing agents mimics the effects of gpx-3(tm2059), gpx-5(tm2024) and gpx-8(tm2108) mutations, while high dose mimics the effects of gpx-1(tm2100) and gpx-4(tm2111) mutations, it’s possible that loss of GPX-3, GPX-5 or GPX-8 leads to a low level of lipid oxidation, and loss of GPX-1 or GPX-4 causes a higher level of lipid oxidation. In both reporter strains (muIs32 and zdIs5), we found that Ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1), an antioxidant agent that traps LOO• and thus can function as a ferroptosis inhibitor43, suppressed axonal fusion induced by GPX4 inhibitors (ML210, ML162, and RSL3) (Fig. 2L–N). Together, these results suggest that a moderate level of ferroptosis signaling promotes axonal fusion, while excessive ferroptosis signaling leads to axonal debris, possibly due to ferroptosis-induced axon degeneration.

Axonal fusion is tightly controlled by lipid peroxidation

We next sought to understand how ferroptosis signaling regulates injury response. N-Acetylcysteine (NAC) is the synthetic precursor of intracellular GSH and is used to increase GPX enzyme activity (Fig. 3A)44,45,46. We observed no effects of NAC treatment on axonal fusion rate or axon debris phenotype in wildtype animals (Fig. 3B, C). We next tested whether inhibiting ferroptosis with NAC can affect fusion or debris in gpx mutants, which showed either enhanced fusion rate or debris frequency (Fig. 1D–G). In gpx-1(tm2100) animals, which normally exhibited high debris rate and low fusion rate, NAC treatment significantly enhanced fusion rate and reduced the percentage of animals showing axonal debris (Fig. 3D, E). These results support a notion that gpx-1(tm2100) has a high level of ferroptotic signaling and lowering the level with NAC results in a moderate degree of lipid oxidation, a condition favoring axonal fusion. Further supporting this notion, we observed that heterozygous gpx-1(tm2100) mutants had a higher fusion rate and a lower debris frequency compared to the homozygous mutants (Fig. 3D, E). We also accessed the effect of NAC in gpx-5(tm2024), which appeared to have a low lipid oxidation level and normally showed a high fusion rate and a low debris rate. We found that NAC treatment was sufficient to lower the fusion rate but not to affect the already low debris rate in gpx-5(tm2024) (Fig. 3F, G). And heterozygous gpx-5(tm2024) mutants also showed a lower fusion rate compared to the homozygous mutants (Fig. 3F, G). Together, these results suggest that an optimal level of ferroptosis signaling is required for a high axonal fusion efficiency. Ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 (FSP1) is a CoQ10 plasma membrane oxidoreductase and protects cells against glutathione-independent ferroptosis (Fig. 3A)47,48. We found that touch neuron-specific overexpression of WAH-1, the ortholog of human AIFM1 and FSP1 (aka AIFM2), inhibited ML162-induced axonal fusion (Fig. 3H, I). Also, the debris rate in gpx-1(tm2100) and axonal fusion rate in gpx-5(tm2024) were decreased by WAH-1 overexpression (Fig. 3H–K), suggesting that axonal fusion and debris phenotypes are tightly controlled by the level of ferroptosis signaling and lipid peroxidation.

A Schematic diagram showing the ferroptosis pathway and the function points of NAC and WAH-1. Representative images (B, D and F) and quantification of axonal fusion and debris in WT (C), gpx-1 (E) and gpx-5 (G) deletion mutants with indicated genotypes. Representative images (H) and quantification of axonal fusion and debris in WT (I), gpx-1 (J) and gpx-5 (K) mutants. WAH-1 overexpression suppressed debris in gpx-1 mutant and fusion in gpx-5 mutant. L Representative images and quantification of BODIPY 581/591 C11 staining in the tail region (where PLM is located) of adulty day 1 (A1) wildtype animals treated with ML162 or Fer-1. ML162 significantly increased BODIPY staining intensity. M Representative images and quantification of BODIPY 581/591 C11 staining in the tail region of indicated strains at A1 stage. BODIPY staining intensity was higher in gpx mutants. N Representative images and quantification of hydrogen peroxide sensor HyPer in PLM cell body showing that hydrogen peroxide level in indicated strains. O Quantification of axonal fusion and debris. Manipulating the lipid peroxidation levels with Fer-1 or ML162 in gpx mutants altered the injury responses, suggesting that an optimal level of lipid peroxidation is required for axonal fusion. See Supplementary Table 1. P, Q Representative images and quantification of axonal fusion and debris of indicated conditions. Fer-1 treatment lowered lipid peroxidation level, shifting injury response from debris to axonal fusion. R, S Representative images and quantification of axonal fusion and debris in gpx-8 mutants with indicated treatments. Fer-1 lowered lipid peroxidation level and reduced axonal fusion. ML162 increased lipid peroxidation, shifting the injury response from fusion to debris. The dotted box marks the tip of the regenerative axon, and a zoomed-in image of the region is presented on the right or below. Statistics: One-way ANOVA; mean ± SEM. For all bar graphs of fusion and debris rates, the total animals of each condition (total number indicated above or in each bar) were randomly divided into 2 or 3 groups for statistical analyses.

The results above supported the hypothesis that injury responses (axon regrowth, axonal fusion and debris) are convertible by manipulating lipid peroxidation level. To test this hypothesis, we first examined the effects of ferroptosis agents and GPX mutations on lipid peroxidation using BODIPY staining. Consistent with its role in promoting lipid peroxidation, treatment with 0.5 µM of ML162 significantly elevated BODIPY intensity, and increasing the dose of ML162 to 1 µM further enhanced BODIPY intensity (Fig. 3L). Despite the elevated lipid peroxidation level, this dose increasement of ML162 abolished the effects of ML162 on promoting axonal fusion (Fig. 2J), suggesting that axonal fusion requires a moderate level of lipid peroxidation. Similarly, loss of GPX-1 or GPX-5 led to increased BODIPY staining, and treatment with ML162 or Fer-1 enhanced or diminished BODIPY intensity in gpx-5 mutants respectively (Fig. 3M). Using the genetically encoded hydrogen peroxide senser Hyper49, we found that gpx-1 and gpx-5 mutants displayed higher levels of hydrogen peroxide in PLM neurons (Fig. 3N). We next examined the effects of Fer-1 and ML162 in wildtype and gpx mutants. In young adult wildtype control, low dose of ML162 treatment enhanced axonal fusion rate and Fer-1 treatment did not show an effect (Fig. 3O, and Supplementary Table 1). Inhibiting ferroptosis with Fer-1 in gpx-1(tm2100) reduced debris rate and enhanced fusion rate, but ML162 treatment did not affect the injury response pattern in gpx-1(tm2100) (Fig. 3P, Q). Similar pattern was found in gpx-4(tm2111) and gpx-7(tm2166), except for that gpx-7(tm2166) did not normally show debris (Fig. 3O, and Supplementary Table 1). Thus, gpx-1(tm2100), gpx-4(tm2111) and gpx-7(tm2166) animals might have a relatively high level of lipid peroxidation. Fer-1 treatment might reduce lipid peroxidation to a moderate level which favors axonal fusion, whereas ML162 treatment might not further enhance the already high lipid peroxidation level. In the cases of gpx-3(tm2059), gpx-5(tm2024) and gpx-8(tm2108), they normally showed high fusion rate and low debris rate (Fig. 1D–G), suggesting a moderate level of lipid peroxidation. Reducing their lipid peroxidation level with Fer-1 decreased fusion rate but did not affect debris rate. Enhancing the lipid peroxidation with ML162 led to decreased fusion rate and increased debris rate (Fig. 3O, R, S, and Supplementary Table 1). This is consistent with the notion that gpx-3(tm2059), gpx-5(tm2024) and gpx-8(tm2108) mutants have a moderate level of lipid oxidation and that either enhancing or reducing the level disrupts axonal fusion. Taken together, these results suggest that an optimal level of lipid peroxidation is required for axonal fusion and that manipulating the level is sufficient to shift the injury response from one to another.

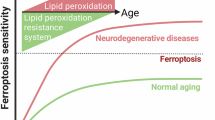

Aged neurons possess higher ROS and show increased axonal fusion

ROS levels increase during normal physical aging due to an increase in oxidation products and a decline in antioxidants defenses50. Exposure to ROS can induce lipid peroxidation, which occurs when ROS oxidizing agents interact with membrane phospholipids51. Given the role of lipid peroxidation in promoting axonal fusion, we examined injury responses in aged neurons. We found that axonal fusion and debris rates were both increased in Adult Day 10 PLM neurons compared to Day 1 (Fig. S1A–C). An enhanced axonal fusion rate was previously observed in aged neurons18. Using HyPer and roGFP reporters, genetically encoded fluorescent sensor for detecting intracellular hydrogen peroxide and ROS respectively49,52, we confirmed that aged neurons possessed a higher level of ROS (Fig. S1D, E). The enhanced axonal fusion in aged neurons was suppressed by ferroptosis inhibitor Fer-1 and by GPX-1 overexpression. It was also suppressed by ferroptosis inducer ML162 (Fig. S1F). For the enhanced axonal debris rate in aged animals, it was suppressed by Fer-1, overexpression of GPX-1 or GPX-5, as well as NAC, the glutathione precursor and an antioxidant, but not by ML162 (Fig. S1G). The reduction of oxidative levels in aged PLM neurons caused by NAC was confirmed by the HyPer sensor (Fig. S1H). These results support that aged neurons possess a moderate-to-high level of lipid ROS, as confirmed by BODIPY staining (Fig. S1I), resulting in higher fusion and debris rates than young neurons (Fig. S1J). Fer-1 and GPX expression can reduce the lipid ROS level and suppress axonal fusion and debris, while ML162 treatments further enhance lipid ROS level, therefore shifting the cells from a status supporting fusion to a status causing debris.

Ferroptosis signaling activates PS exposure to promote axonal fusion

It has been previously reported that phosphatidylserine (PS) externalization in PLM axon after injury serves as an important “save me” signal for the regrowing axon to recognize and connect16. It was further demonstrated that the level of PS exposure correlates with axonal fusion rate18. PS exposure serves as a conserved “eat me” signal for phagocytic uptake of dying cells53. Lipid peroxidation is known to promote PS exposure54,55, and a recent study reported that ferroptosis can induce PS exposure in a cultured human T cell line56. To determine whether ferroptosis signaling can induce induced PS exposure to promote axonal fusion, we visualized touch neuron-specific PS with a mKate2-tagged Annexin V (Pmec-4::mKate2::AnxV). In this system, Annexin V is expressed in touch neurons under the mec-4 promoter. Annexin V can be then translocated across the plasma membrane and secreted via extracellular vesicles, followed by binding to the exposed PS on the outer membrane57. Consistent with previous reports16, we observed mKate2-Annexin V in the distal fragment of the injured PLM of wildtype animals 1 h post injury, while in intact neurons mKate2 signal was detectable only in the cell body (Fig. 4A, B). AnxV was detectable in intact axons of gpx-1(tm2100), and its level was further elevated and significantly higher than that in wildtype after injury (Fig. 4A, B), indicating that ferroptosis signaling can induce PS exposure. We further tested other gpx mutants and found that AnxV levels were increased in all gpx mutants. gpx-1(tm2100), gpx-4(tm2111) and gpx-7(tm2166), which displayed a high debris rate and a low fusion rate (Fig. 1F, G), showed significantly higher AnxV level in injured axons than wildtype (Fig. 4B). In contrast, gpx-3(tm2059), gpx-5(tm2024) and gpx-8(tm2108), which displayed a high axonal fusion rate and a low debris rate (Fig. 1F, G), showed slightly higher level compared to wildtype (Fig. 4B). Therefore, these results suggest that a low level of PS exposure promotes axonal fusion, while a high level of PS exposure leads to axonal debris.

A Ferroptosis signaling induces PS exposure. Representative images of PS exposure immediately before axotomy and 1 h post axotomy. PS exposure was visualized by mKATE2-tagged Annexin V expression. B Quantification of PS exposure in the indicated strains. The foldchange of mKate2-AnxV intensity in the distal axon between right before axotomy and 1 h post injury was plotted. High debris rates correlated with high PS exposure, while high fusion rates associated with a moderate PS exposure. C Quantification of axonal fusion in the indicated strains and conditions. ML162-induced axonal fusion is abolished in psr-1 mutants. D, E Representative images and quantification of axonal fusion in WT (muIs32) with indicated genotypes and conditions. PSR-1 overexpression further increased ML162-induced axonal fusion. F, G Representative images and quantification of axonal fusion. ML162-induced axonal fusion is abolished in eff-1 mutant. H, I Representative images and intensity plot profile of mCherry::PSR-1 before and 1 h post axotomy. Injury-triggered PSR-1 condensation at the tips of injured axons is reduced by 1,6-HD treatment. J Percentage of animals showing PSR-1 localization at the injury site 1 h post axotomy. 1,6-HD inhibits PSR-1 condensation at the injury site. K, L Representative images and intensity plot profile of mCherry::PSR-1 at the regenerative axon and distal stump 12 h post injury. PSR-1 condensates are enriched at the regenerative growth cone and the reconnection site. M In vitro droplet formation assay showing that recombinant mCherry::PSR-1 forms droplets and aggregates in the presence of 10% PEG8000. Addition of 5 mM H2O2 in the droplet formation buffer led to enhanced PSR-1 aggregation. PSR-1 droplets and aggregates melt in the presence of 5 mM DTT. N Zoom out images and schematic illustrations of mCherry::PSR-1 droplets and aggregates at indicated conditions. Multiple images with overlapping fields were stitched to produce a panorama. O, P Representative images and quantification of FRAP analyses on mCherry::PSR-1 condensates. Statistics: One-way ANOVA or Student’s t-tests; mean ± SEM. For all fusion and debris bar graphs, animals of each condition (total number indicated) were randomly divided into 2 or 3 groups for statistical analyses.

Importantly, we found that AnxV level in gpx mutants could be altered by ML162 or Fer-1 treatment. In general, a high AnxV level could be decreased by Fer-1 and a moderate or low level of AnxV signal could be elevated by ML162 (Fig. S2A–E; Supplementary Table 2). We next sought to evaluate the relationship between the level of PS exposure and axon injury responses by generating heatmaps using average index values of AnxV levels, axonal fusion and debris from wildtype and gpx mutants under different conditions. Our results highlighted that a moderate level of lipid peroxidation leads to moderate PS exposure and promotes axonal fusion, while a high level of lipid peroxidation induces a high level of PS exposure which is associated with the formation of a debris-like structure (Fig. S2F–H).

Ferroptosis-induced axonal fusion requires PSR-1 and EFF-1

The exposed PS after axon injury is recognized and bound by PS receptor PSR-1, one of the molecules involved in apoptotic engulfment pathways that recognize the PS ‘eat-me’ signal and mediate the clearance of dying cells by phagocytes1,16,58. PSR-1 functions upstream to EFF-1, the membrane fusogen that mediates the fusion of the two membranes of regrowing axon and the distal axon fragments16. We next tested whether axonal fusion induced by ferroptosis signaling required the engulfment pathway components and EFF-1. We found that ML162 failed to induce axonal fusion in two independent psr-1 mutants (Fig. 4C). Overexpression of PSR-1 was sufficient to increase axonal fusion rate in young animals treated with ML162 (Fig. 4D, E), as well as untreated aged animals (Fig. S1K, L). Similar to psr-1 mutation, eff-1 mutation completely abolished the effect of ML162 in promoting axonal fusion (Fig. 4F, G). It’s known that TTR-52 can bind PS exposed by apoptotic cells59 and it has been previously reported that TTR-52, CED-6, and CED-7, which are components of a phagocytic pathway, are required for injury-induced axonal fusion16. We next tested if ferroptosis-induced axonal fusion is dependent on these components. We observed that in ced-6, ced-7, and ttr-52 mutants, ML162 treatment led to significantly increased fusion rates, even though the fusion rates were lower than that in WT (Fig. S3A–D). Therefore, these data suggest that ferroptosis signaling-induced axonal fusion is predominantly mediated by PSR-1 and EFF-1.

PSR-1 forms phase-separated condensates and the condensates are responsive to oxidative agents

To investigate PSR-1’s role in enhanced fusion under oxidative conditions, we examined its localization in PLM axons. GFP::PSR-1 was predominantly localized in the cell body in intact neurons. One hour post injury, we observed strong GFP::PSR-1 puncta at the severed axon stumps (Fig. 4H, I; Fig S3A, B), and this localization pattern was not affected by ML162 (Fig. 4J). During the active regeneration phase (12-24 hours post-injury), PSR-1 puncta were constantly found at the tips of regenerative growth cones and at the axonal fusion sites (Fig. 4K, L).

Injury-induced PSR-1 puncta formation prompted us to test if PSR-1 undergoes phase-separated condensation. We first tested if PSR-1 puncta could be affected by 1, 6-Hexanediol (1,6-HD), an aliphatic alcohol that has been routinely used to disrupt multivalent hydrophobic protein-protein interactions to disassemble phase-separated droplets60,61. We found that 1,6-HD significantly reduced PSR-1 localization at the tip of injured axons (Fig. 4M). 1,6-HD treatment also abolished the fusion-promoting effects of ML162 at PSR-1 overexpression background (Fig. 4D, E), suggesting that PSR-1 condensation is required for effective axonal fusion.

We next purified recombinant mCherry::PSR-1 protein (Fig. S4A–C) and performed in vitro droplet formation assays. In the presence of PEG8000, purified PSR-1 formed both droplets and aggregates (Fig. 4N, O). The size of the PSR-1 droplets and aggregates correlated with protein concentration (Fig. S4D, E). Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) to assess the liquidity of condensation systems62 observed a slow and partial recovery from both droplets and aggregates (Fig. 4P, Q), indicating that these condensates exhibit gel-like characteristics63.

As PSR-1 is required for ferroptosis signaling-induced axonal fusion, we next tested if PSR-1 condensates were affected by oxidative environment. We performed droplets formation assay in the presence of 5 mM H2O2 and found that H2O2 promoted PSR-1 aggregation, converting the scattered droplets and aggregates into clustered aggregates (Fig. 4N, O). These clustered aggregates display low percentage recovery of FRAP like the scattered droplets and aggregates (Fig. 4P, Q). We further examined the effect of DTT on PSR-1 condensation in vitro. The presence of DTT in the droplet formation buffer greatly diminished PSR-1 droplets and aggregates (Fig. 4N, O). These results suggest that the redox state might regulate PSR-1 condensation and its function in axonal fusion.

PSR-1 CTD modulates PSR-1 condensate properties and PSR-1 function

Proteins that form phase separated condensates through multivalent interactions usually fall into two categories: those featuring modular domains and those characterized by intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs)64. The CTD of PSR-1 harbors amino acid sequences indicative of an IDR (Fig. S4A). To test if CTD is mediating PSR-1 condensation, we purified the CTD-deleted PSR-1 protein and performed droplet formation assay (Fig. S4C). Unlike full-length PSR-1, which forms both droplets and aggregates, PSR-1(ΔCTD) formed only circular droplets, which were also sensitive to 1,6-HD (Fig. S4D, E). PSR-1(ΔCTD) localization pattern was not affected by ML162 and reduced by 1,6-HD (Fig. S4F). H2O2 transformed dispersed PSR-1(ΔCTD) droplets into aggregated forms, transitioning from a more fluid-like state to a gel-like consistency, as evidenced by FRAP outcomes (Fig. S4G–J). Complete dissolution of PSR-1(ΔCTD) droplets was observed upon treatment with DTT (Fig. S4G, H). Additionally, in contrast to full-length PSR-1, overexpression of PSR-1(∆CTD) not only failed to enhance ML162-induced axonal fusion but also partially inhibited this process (Fig. S4K). The reduced axonal fusion in PSR-1(∆CTD) transgenic animals was further abolished by 1,6-HD. These observations suggest that the CTD of PSR-1 can modulate PSR-1 condensation and function.

Axonal fusion is specifically induced by ferroptosis signaling, but not other cell death signaling

Given the important role of a moderate level of PS exposure induced by ferroptosis signaling in promoting axonal fusion, we asked whether other signals that trigger PS exposure can also promote axonal fusion. PS exposure on the outer plasma membrane has long been considered a feature of apoptotic cells, and recent studies have reported that PS exposure is also detected in other types of cell death, including necroptosis and ferroptosis56,65. We first tested whether axonal fusion rate in gpx mutants can be affected by apoptosis or necroptosis inhibitor, similar to ferroptosis inhibitor. We used pan-caspase inhibitor zVAD-fmk and receptor-interacting serine/threonine kinase 1 (RIPK1) kinase activity inhibitor Necrostatin-1 (Nec-1)66,67 to inhibit apoptosis and necroptosis, respectively. As we showed above, ferroptosis inhibitor Fer-1 treatment on gpx-1(tm2100) animals, which normally displayed a high debris rate and a low fusion rate, was sufficient to decrease the debris rate and increase the fusion rate (Fig. 3P, Q). However, zVAD-fmk or Nec-1 treatment did not significantly alter the injury response in gpx-1(tm2100) (Fig. 5A, B). In gpx-5(tm2024), Fer-1 treatment reduced its fusion rate, while zVAD-fmk or Nec-1 treatment did not have an obvious effect on either the fusion rate of the debris rate (Fig. 5C, D). These results suggest that apoptosis or necroptosis signaling might not be involved in axonal fusion regulation. We also examined the effect of an apoptosis-inducing agent, Bisphenol A (BPA)68, on injury response in wildtype animals. BPA treatment reduced the length of axon regeneration, but axonal fusion rate was not enhanced by any tested concentration of BPA. Instead, debris-like structures were observed in animals treated with high concentrations (25 or 50 µM) of BPA (Fig. 5E, F). This is consistent with a previous report that the core apoptotic pathway genes, including CED-9/BCL-1, CED-4/APAF-1 and cell-killing caspase ced-3, are not required for axonal fusion16. Antimycin A is an inhibitor of electron transport from cytochrome b to cytochrome complex III69. Similar to BPA, antimycin A treatment led to reduced PLM axon regrowth length and enhanced axonal debris rate in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 5G, H), but did not promote axonal fusion. These data suggest that axonal fusion is specifically induced by ferroptosis signaling, but not other cell death signaling.

A, B Quantification of axonal fusion and debris rates in gpx-1 mutants treated with ferroptosis inhibitor Fer-1, apoptosis inhibitor z-VAD and necrosis inhibitor Nec-1. Only Fer-1, but not z-VAD or Nec-1, is sufficient to shift injury response from debris to fusion in gpx-1 mutants. C, D Quantification of axonal fusion and debris rates in gpx-5 mutants treated with Fer-1, z-VAD and Nec-1. Only Fer-1, but not z-VAD or Nec-1, can suppress axonal fusion in gpx-5 mutants. E, F Quantification of regrowth, axonal fusion, and debris in the reporter strain treated with Bisphenol A, an apoptosis inducer. Bisphenol A does not promote axonal fusion at all concentrations tested. Bisphenol A treatment at higher concentrations leads to axonal debris. G, H Quantification of regrowth, axonal fusion, and debris in the reporter strain treated with antimycin A, an inhibitor of the electron transport chain in mitochondria. Antimycin A fails to promote axonal fusion but causes axonal debris at a high concentration. Representative images (I) and quantification of regrowth (J), axonal fusion and debris (K) in the WT (reporter) strain. 3 mM H2O2 promotes axon regrowth and axonal fusion, while 30 mM H2O2 leads to axonal debris. L Quantification of axonal fusion and debris in the WT (reporter) strain. Axonal fusion induced by H2O2 is suppressed by Fer-1. M, N Representative images and quantification of fusion and debris rates with the indicated strains and conditions. O Schematic summary showing that a moderate (blue arrows) level of ferroptosis signal promotes axonal fusion, while a high (orange arrows) level leads to axonal debris. Apoptotic signaling and mitochondrial dysfunction can lead to axonal debris but not axonal fusion. Scale bar: 20 µm. Statistics: One-way ANOVA; mean ± SEM. For all fusion and debris bar graphs, animals of each condition (total number indicated) were randomly divided into 2 or 3 groups for statistical analyses.

Lipid peroxidation can be induced by cellular ROS, among which hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is a non-radical ROS and a major member of ROS family21. Given that an optimal level of lipid peroxidation is associated with a moderate level of PS exposure to promote axonal fusion (Fig. S2), we next tested whether H2O2 could promote axonal fusion. We found that treating animals with 3 mM H2O2 led to significantly longer axon regrowth (Fig. 5J). This promotive effect of H2O2 in axon regeneration has been reported previously in zebrafish sensory neurons70,71. However, when we treated the animals with a higher H2O2 concentration (30 mM), the regrowth enhancing effect was abolished (Fig. 5J). 3 mM H2O2 treatment also significantly enhanced axonal fusion rate, while 30 mM H2O2 treatment led to axonal debris (Fig. 5I, K). To determine whether the effect of H2O2 on axonal fusion is mediated by lipid peroxidation, we applied H2O2 and Fer-1 simultaneously and examined if blocking lipid peroxidation could block H2O2-induced axonal fusion. We found that axonal fusion induced by 3 mM H2O2 was partially rescued by 0.5 µM Fer-1 and completely rescued by 1 µM Fer-1 (Fig. 5L), indicating that cellular ROS can promote axonal fusion through lipid peroxidation. We next examined mutants of skn-1 gene, the C. elegans ortholog of the key regulator of antioxidant response pathway Nrf272. Consistent with the role of SKN-1/Nrf2 as a transcription factor that regulates expression of Gpx genes and other ferroptosis genes73, a point mutation skn-1(zj15) led to a slightly enhanced axon fusion rate (Fig. 5M, N). However, ML162-induced axonal fusion was partially diminished by the point mutation skn-1(zj15) and fully abolished by the deletion mutation skn-1(ok2315) (Fig. 5M, N). Furthermore, ML162 treatment in skn-1(ok2315) resulted in enhanced axonal debris formation. These results further support that axonal fusion requires a moderate level of ferroptosis signaling and is inhibited by a high level.

Ferroptosis signaling promotes functional recovery after sciatic nerve injury in mice

Although axonal fusion after injury has not been directly demonstrated in vertebrates to date, there is extensive evidence showing that axonal fusion-like mechanisms can be induced to promote nerve repair in mammals, including humans1. The chemical fusogen polyethylene glycol (PEG) has been used to promote membrane fusion by removing water from the area, thus forcing membranes into close contact74. PEG has been shown to be highly effective in restoring function in transected nerves and PEG treatment has become a common strategy in pre-clinical trials for robust functional recovery1,8,9,75,76. To test if ferroptosis signaling can induce axonal fusion in mammalian neurons, we applied the ferroptosis inducing agent ML162 to transected and re-sutured mouse sciatic nerves and examined the effect on functional restoration (Fig. 6A). We adapted the defined five-step process used in PEG fusion76. First, the mouse sciatic nerve was transected with flat ends. Second, cut ends were then rinsed with Ca2+-free hypotonic saline to prevent plasmalemmal sealing. Third, the ends were re-joined with microsutures. Fourth, ML162 (0.25 µM) and/or PEG (500 mM) solution was applied to the sutured nerve to induce membrane fusion. Fifth, the nerve was rinsed with Ca2+-containing isotonic solution to remove ML162 and/or PEG and to promote vesicle-mediated membrane repair (Fig. S5A). We compared the control and treated animals before and after surgery using various behavioral tests: the pinprick, foot fault (FF) asymmetry, and toe spreading test (Fig. S5B–D)77,78.

A Schematic diagram indicating neuron degeneration and its regeneration after sciatic nerve transection & resuture. B Quantification of pinprick test in FVB/NJ mice. 8 weeks old animals were tested for pinprick response right before the operation (Day 0). Immediately after SNT/resuture, the injured nerves were treated with saline control (resuture only), PEG, ML162, and ML162 + PEG. The 4 different treatment groups were then evaluated at different time points for a month. PEG or ML162 treatment was sufficient to improve pinprick response at mid-stage, while combination treatment of PEG and ML162 resulted in improved pinprick scores at all stages. n = 5 for resuture only; n = 3 for PEG; n = 10 for ML162; n = 9 for ML162 + PEG. C Quantification of foot fault (FF) asymmetry test using the same experimental animals from (B). PEG or ML162 treatment individually improved FF asymmetry scores and ML162/PEG co-treatment showed further improvement at early stage. D, E Representative images and quantification of toe spreading test using the same experimental animals from (B). ML162/PEG co-treatment group showed significant improvement compared to other groups. F Quantification of pinprick test in GPX4fx/fx;Avil-Cre-ER+ mice. Tamoxifen was administered to 8 weeks old mice intraperitoneally at a dose of 60 mg/kg for a total of five injections (once daily) to induce Cre expression. SNT/resuture was performed one day after the final dose of tamoxifen was given. GPX4fx/fx;Avil-Cre-ER- animals were used as control. GPX4 cKO animals only survived for ~3 weeks after tamoxifen injection was completed. GPX4 cKO animals showed similar pinprick scores as control animals at time points tested. n = 4 for each group. G Quantification of foot fault (FF) asymmetry test using the same experimental animals from (F). GPX4 cKO mice display significantly higher FF asymmetry scores compared to the control animals. H, I Representative images and quantification of toe spreading test using the same animals in (F). GPX4 cKO mice display significantly higher toe spreading scores than the control mice. Statistics: One-way ANOVA; mean ± SEM.

The nociceptive sensitivity in the mice was measured by applying a pinprick to the distal skin territory of the injured sciatic nerve. After a sciatic nerve injury, the resuture-only group showed a gradual recovery of nociceptive sensitivity in the skin of the lateral paw. At 27 days post-surgery, the pinprick score has restored to a level comparable to pre-injury (Fig. 6B, and Fig. S6A). PEG treated group displayed a higher pinprick score than the resuture-only control group at most time points, suggesting an improved functional recovery. Similarly, ML162 treated animals showed higher pinprick scores than the control group. Notably, animals treated with both PEG and ML162 displayed the best pinprick scores among the 4 groups (Fig. 6B, and Fig. S6A).

FF is more sensitive to proximal sensory-motor functions and earlier behavioral recovery following sciatic nerve injury78. We found that the FF score of the control group did not improve until 14 days post injury (Fig. 6C, and Fig. S6B). In contrast, either the PEG or ML162 groups showed a significantly increased FF score in the early stage (from Day 4 to Day 10). Like in the pinprick test, the ML162 and PEG co-treatment group showed better FF scores compared to either ML162 or PEG-treated groups, particularly at early stages (Day 4 to Day 10) (Fig. 6C, and Fig. S6B). Considering that the severed nerves are degenerative within 1–3 days (Fig. 6A)79,80, an enhanced behavior restoration score before Day 4 suggests that axonal fusion might have occurred to prevent axon degeneration. We noticed that the FF scores of the resuture-only control group increased rapidly from Day 14, resulting in a gradually reduced difference between the control group and other treatment groups (Fig. 6C, and Fig. S6B). This rapid restoration of physical function after Day 10 is likely due to the effect of axon regeneration, as the axon regrowth rate is about 1-2 mm per day81,82, and it takes roughly 10–14 days for the injured sciatic nerves to regenerate and reinnervate to the target muscles. Therefore, although this evidence is indirect, the functional restoration observed between Day 4 and Day 10 in the ML162-treated groups suggests that ML162 may induce axonal fusion in mice.

We further measured toe spreading reflex to assess motor recovery after the sciatic nerve injury. We found that the ML162 + PEG co-treatment group showed significantly higher toe motor function restoration at the early stages compared to the rest three groups (Fig. 6D, E; Supplementary Video 1), which displayed rapid behavior recovery after Day 14 (Fig. 6D, E; Fig. S6C), likely due to nerve regeneration and reinnervation. The effect of ML162 + PEG on behavior recovery at early stages again suggest that a proper level of ferroptosis signaling may promote functional recovery through axonal fusion.

Having shown that the ferroptosis inducing drug ML162 can promote functional recovery likely through axonal fusion, we next asked if genetically suppressing GPX4 activity could promote axonal fusion and functional restoration. We crossed our GPX4 cKO strain with the Avil-CreER line83,84, and induced GPX4 conditional knockout (cKO) in sensory ganglia by tamoxifen injection at 8 weeks old. Tamoxifen treated GPX4fx/fx;Avil-CreER mice died within 3 weeks after tamoxifen injection, indicating that GPX4 expression in sensory neurons are essential for survival. Despite the lethal phenotype 3 weeks after GPX4 ablation, we observed improved behavior restoration in GPX4fx/fx;Avil-CreER mice after SNT and resuture as measured by FF asymmetry and Toe spreading test (Fig. 6F–I). This improved physical function in GPX4 cKO mice within 4 to 10 days after nerve transection further supports that manipulating GPX4 level may induce axonal fusion to promote functional recovery.

ML162 prevents denervation of neuromuscular junctions

The positive effect of PEG and ML162 on functional restoration prompted us to test if they had an impact on axon regeneration. We first assessed DRG axon regrowth after the behavior tests were completed (30 days post SNT and resuture) by staining for the regeneration marker SCG1085,86. As expected, SCG10-positive axons were present throughout the sciatic nerve and we did not observe any significant difference among the 4 groups: resuture only control group, PEG treated group, ML162 treated group, and PEG + ML162 co-treatment group (Fig. S7A, B). We next measured DRG axon regeneration 3 days post injury and observed SCG10 positive axons around the injury sites (Fig. 7A), indicating limited axon regeneration at this time point. PEG and/or ML162 treatment did not affect axon regeneration, as SCG10 intensity was at a similar level for all 4 groups (Fig. 7A, B). This further supports that the effect of PEG and ML162 on promoting functional recovery is through axonal fusion but not axonal regrowth.

A ML162 does not affect axon regeneration. Representative images of longitudinal sciatic nerve sections distal to the lesion, stained with anti-SCG10 (green), β-tubulin (red), and DAPI (blue) at 3 days post-operation. White asterisk marks the SNT/resuture site. 8 weeks old FVB/NJ mice were subjected to SNT/resuture and the injured nerves were treated with saline control (resuture only), PEG, ML162, and ML162 + PEG. 3 days post operation, sciatic nerves from the 4 different treatment groups were then collected for axon regeneration analyses. Scale bar: 1 mm. B Quantification of SCG10 intensity in sciatic nerve section at different distances from the SNT/resuture site, normalized to SCG10 intensity proximal to the SNT/resuture site. One-way ANOVA; mean ± SEM; n = 3 for each group. C Representative images showing the NMJs in abductor digiti minimi lateral plantar muscles. Cryostat sections were stained with BTX (green) and anti-NF-200 (red) at 3 days post-operation. NF-200 staining at NMJs was only detected in the ML162 + PEG co-treatment group, suggesting that the combination treatment can prevent NMJ denervation through promoting axonal fusion. Scale bar: 10 µm. D Quantification of innervated NMJs in the 4 experimental groups. One-way ANOVA; mean ± SEM; n = 3 for Contralateral; n = 2 for resuture only; n = 3 for PEG; n = 3 for ML162; n = 5 for ML162 + PEG. E Percentages of the innervated NMJs from the 5 individual animals in the ML162 + PEG experimental group. Innervated NMJs were detected in all 5 individual animals. F Schematic illustration to summarize experiments and results. Co-treatment of ML162 and PEG prevents denervation of NMJ at 3 days post nerve transection, likely through promoting axon fusion.

Previous studies have shown that distal axon fragments of mammalian DRG neurons degenerate within 1-3 days after axon injury, resulting in disruption of neuromuscular junctions (NMJ)79,80. After nerve injury, the regenerative axons will reinnervate muscles, but the reinnervation do not occur until two weeks post injury due to the rate limit of axon regeneration87. If the enhanced functional recovery in ML162 and/or PEG treated mice within the first week post injury is due to axonal fusion, we would expect to see innervated NMJs within the first week. We therefore examined the NMJs structure at 3 days after transection and resuture using anti-neurofilament (NF200) and α-Bungarotoxin (BTX) to label axon and postsynaptic membrane respectively. The resuture only control group showed no innervated NMJs on abductor digiti minimi lateral plantar muscles, indicating that motor neurons have completely degenerated 3 days post-operation (Fig. 7C–E). Very few innervated NMJs were detected in the PEG or ML162 treated groups. However, significantly more innervated NMJs were observed in the ML162 + PEG group and innervated NMJs were detected in the plantar muscles of all individual animals treated with ML162 and PEG (Fig. 7C–E). As expected, we detected full restoration of motor end plate reinnervation at Day 30, as a result of axon regeneration (Fig. S7A–C). The presence of innervated NMJs at Day 3 is consistent with the enhanced functional recovery in this group during the early period (Fig. 6). While we have not ruled out the possibility that ML162 may delay Wallerian degeneration, our results support that the combined treatment of ML162 and PEG prevents axon degeneration and NMJ denervation, possibly by promoting axonal fusion (Fig. 7F).

Discussion

Axonal fusion represents an efficient repair strategy after nerve injury. Axonal fusion has been demonstrated in multiple invertebrates including C. elegans, and significant advances have been made in identifying genetic factors involved in the process in the past decade. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying axonal fusion remains unclear. Here we report that mutations in gpx genes promotes functional axonal fusion of C. elegans touch neurons in a cell-autonomous manner. The enhanced fusion rate in gpx mutants can be reversed by ferroptosis inhibitors. We show that a low dose of ferroptosis inducing drugs can promote axonal fusion, while a high dose leads to axon debris but not axonal fusion. Furthermore, a moderate level of lipid peroxidation is associated with a moderate level of PS exposure and a high fusion rate, and that high level of lipid peroxidation is associated with high PS exposure and a high debris rate. Notably, PSR-1 undergoes phase-separated condensation, which correlates its function in axonal fusion and can be influenced by oxidative states. We also provide evidence that ferroptosis signaling promotes functional recovery after nerve injury in mice. In summary, we reveal that GPX modification can promote axonal fusion of injured axons in C. elegans, and our data suggest that combination treatment with ferroptosis inducers and chemical fusogens might be a promising therapeutic strategy to facilitate nerve repair in mammals.

Levels of lipid peroxidation determine the patterns of injury response

In wildtype young adult C. elegans, PLM axons typically regenerate 80 ~ 100 µm in length within 24 h post laser axotomy32,37,88. In a smaller portion of animals, the regenerative axon fuses with the distal fragment, preventing degeneration of the distal fragment16,17,18. In this study, we report that axonal fusion rate is significantly increased in mutants of gpx-3, gpx-5 and gpx-8. And in mutants of gpx-1 and gpx-4, we observed another pattern of injury response, debris formation, in addition to axonal regrowth and axonal fusion (Fig. 1). Consistent with the role of GPX in inhibiting ferroptosis, ferroptosis-inducing agents can promote axonal fusion and debris. The effects of ferroptosis-inducing agents are dose-dependent, with a low dose leading to fusion, while a high dose resulting in debris formation (Fig. 2). And the different injury responses (fusion vs debris) in different gpx mutants (gpx-3, gpx-5 and gpx-8 vs gpx-1 and gpx-4) are likely due to different levels of lipid peroxidation in these mutants. Ferroptosis is a regulated cell death characterized with severe membrane lipid peroxidation. Peroxidized phospholipids are known to cause significant changes in membrane structure and properties89,90,91,92. Axonal fusion caused by gpx mutation or ferroptosis-inducing can be rescued by inhibition of lipid peroxidation pharmacologically (Fer-1 treatment) or genetically (GPX or FSP expression) (Fig. 1, and Fig. 2). The debris phenotype in gpx-1 and gpx-4 mutants can be also rescued by ferroptosis inhibitor Fer-1 (Fig. 3). Importantly, Fer-1 treatment not only reduced debris rate, but also increased fusion rate in gpx-1 and gpx-4 mutants, suggesting that Fer-1 reduces the lipid peroxidation from a high level (that causes debris) to a moderate level to support fusion. In contrast, ML162 treatment enhanced debris rate in gpx-3, gpx-5 and gpx-8 mutants, which normally show high fusion rate. This suggests that ML162 pushes lipid peroxidation levels in gpx-3, gpx-5 and gpx-8 mutants from moderate to high, converting a fusion condition to a debris condition. Together, these results suggest that levels of lipid peroxidation determine the patterns of injury response, with a low level facilitating axon regrowth, a moderate level promoting fusion, and a high level causing debris.

Notably, we found that aged neurons displayed a higher fusion rate and a higher debris rate (Fig. S1A–C). This might be due to the relatively high basal level of ferroptosis signaling, leading to not only enhanced axonal fusion but also increased axon debris/degeneration. Consistent with this notion, GPX4 inhibition by ML-162 failed to promote axonal fusion in aged animals but led to an even higher debris rate (Fig. S1F, G). Importantly, GPX overexpression or treatment with ferroptosis inhibitors Fer-1 and NAC showed beneficial effects in aged animals (i.e. significantly reduced debris rate). We propose that if the ferroptosis signaling in aged neurons is reduced to an optimal level (by ferroptosis inhibitors or GPX overexpression), axonal fusion can be enhanced in aged neurons, while reducing axonal debris.

Lipid peroxidation functions upstream to PS exposure to regulate axonal fusion

PS exposure has been previously demonstrated to drive fusion after injury. PS normally localizes asymmetrically to the inner leaflet of the membrane. But this asymmetry is disrupted by axon injury, resulting in PS exposure to the outer membrane16,18. The exposed PS serves as a “save-me” signal that is recognized by the regrowing axon in a way similar to apoptotic engulfment1,93. It has been proposed that, following axonal injury, the exposed PS on the distal fragment is bound by the lipid binding proteins TTR-52 and NRF-5, which then interact with proteins on the surface of the regrowing axon for reconnection of the two segments. PS receptor PSR-1, which is involved in the parallel apoptotic engulfment pathway, is also required for axonal fusion. PSR-1 is localized to the mitochondria in intact axons but shifts to the regrowing axon tips after injury to facilitate reconnection16. Following reconnection, the membrane fusogen EFF-1 mediates membrane fusion by forming trimers in trans across apposing membranes94,95,96,97. The repurposing of proteins in apoptotic pathways for axonal fusion and the mechanistic similarity between apoptotic engulfment and axonal fusion raised an interesting question: how are the “eat-me” and “save-me” signals in these two processes regulated and recognized? In this study, we show that lipid peroxidation can serve as an upstream signaling to activate PS externalization. Lipid peroxidation has been demonstrated to cause significant changes in membrane structure and properties89,90,91,92. We found that inducing lipid peroxidation with ferroptosis drugs or gpx mutations was sufficient to elevate PS exposure (Fig. 4, and Fig. S2). Consistent with this, ferroptosis-induced PS exposure has been reported in human T cell line56. We provide evidence that a moderate level of lipid peroxidation leads to moderate PS exposure, which serves as a “save-me” signal to promote axonal fusion. In contrast, a high level of lipid peroxidation induces a high level of PS exposure, which might function as an “eat-me” signal associated with the formation of a debris-like structure (Fig. S2).

Injury-induced PSR-1 condensation on axonal membrane promotes axonal fusion

Phase separated condensation is a known mechanism for increasing the local concentration of particular components to promote their function98. Condensation can also occur on the plasma membrane27,28,30, facilitating cell signaling and membrane dynamics29,99,100,101,102. Our results support that axon injury and ferroptosis signaling triggers PSR-1 condensation on the axonal membrane to facilitate axonal fusion (Fig. S4L). Our in vitro data indicate that the biophysical characteristics of PSR-1 condensates can be influenced by oxidative states: H2O2 prompted a transition of PSR-1 condensates from dispersed droplets and aggregates to clustered aggregates, whereas DTT diminished PSR-1 condensates. Therefore, while ML162 treatment did not result in an enhancement of PSR-1 puncta localization at the tips of injured axons, it likely influenced the properties of PSR-1 condensates. We demonstrate that 1,6-HD effectively inhibits PSR-1 condensation in vivo and reduces axonal fusion triggered by overexpression of PSR-1. Although 1,6-HD is a general inhibitor of condensation driven by multivalent interactions, our findings suggest that PSR-1 condensation may act to increase its local concentration at the axonal membrane’s tip, thereby promoting the reconnection of the regenerating axon with its distal segment.

Axonal fusion is specifically induced by ferroptosis signaling

Ferroptosis is an iron-dependent cell death that differs from apoptosis and necroptosis. However, ferroptosis and the other types of regulated cell death share some common features, including ROS and PS exposure51,65. We found that H2O2, the major member of the ROS family, was sufficient to promote axonal fusion. The effect of H2O2 on axonal fusion can be suppressed by Fer-1 (Fig. 5L), indicating that its effect is mediated by lipid peroxidation. Our data also suggest that lipid peroxidation triggers PS externalization, which serves as a “save-me” signal to facilitate the reconnection of the regrowing axon to the distal fragment. Given that ROS and PS exposure are also associated with apoptosis and necroptosis, we tested whether inducing apoptosis or necroptosis could promote axonal fusion. Unlike ferroptosis-inducing drugs, which enhanced axonal fusion rate in a dose-dependent manner, the apoptosis inducing agent failed to promote fusion. Instead, they significantly enhanced the debris rate (Fig. 5E, F). Consistently, the core apoptotic pathway genes, including CED-9/BCL-1, CED-4/APAF-1 and cell-killing caspase ced-3, are not required for axonal fusion16. Furthermore, Fer-1 suppressed axonal fusion in gpx-5 mutants, but apoptosis and necroptosis inhibitors, z-VAD and Nec-1, failed to do so (Fig. 5A–D). These results suggest that axonal fusion is induced specifically by ferroptosis signaling, but not signaling of other types of cell death despite their similar effect on promoting PS exposure. It’s possible that, in addition to lipid peroxidation and PS exposure, apoptotic or necroptotic stimuli are causing detrimental effects that are not triggered by GPX inhibition. Future studies are required to understand why axonal fusion is specifically induced by ferroptosis signaling.

Combination treatment with ML162 and PEG

C. elegans neurons and mouse neurons likely have different ferroptosis signaling levels. Mouse neurons are more susceptible to ferroptosis due to their dependence on GPX4 and their more developed iron- and lipid-peroxidation-related processes. Evidence shows that mouse neurons are highly sensitive to GPX4 depletion, which results in a lethal phenotype84. In contrast, C. elegans gpx mutants remain viable. To test if ferroptosis signaling can promote axonal fusion in mouse neurons like in C. elegans, we applied ML162, alone or combined with PEG, to transected mouse sciatic nerves after resuture. The chemical fusogen PEG has been applied to both peripheral nerve and spinal cord injury in rodent and dogs10,11,12,13,14 since the first report in 1986 that PEG can mediate axonal fusion in the invertebrate crayfish75. PEG has also been used in pre-clinical trials to restore neuronal function1,9. Like PEG, we found that ML162 treatment improved physical function, particularly in the early phase (Day 4 through Day 10 post injury) (Fig. 6). Importantly, co-treatment with ML162 and PEG further improved functional restoration in the early phase. While restoration of lost behaviors in the late phase (Day 14 through Day 30) is a consequence of axon regeneration and nerve reinnervation, functional recovery in the early phase is more likely due to axonal fusion. Further evidence of axonal fusion was from sciatic nerve innervation analyses at Day 3 post injury, a time point when distal axons completely degenerate, and muscles become denervated (Fig. 6A). But in animals co-treated with ML162 and PEG, we detected retained axon innervation at Day 3 (Fig. 7). The improved physical function and retained muscle innervation in the early phase after nerve transection and resuture suggest that axonal fusion has occurred, thus preventing axon degeneration and muscle denervation. Therefore, combination treatment of ML162 and PEG represents a promising strategy to promote nerve repair through axonal fusion.

Limitations of the study

Using live imaging approach, we show that a moderate level of ferroptosis signaling induces functional axonal fusion in C. elegans. We also provide evidence that axonal fusion can be induced by ferroptosis signaling in mammalian neurons. However, the role of ferroptosis in the mouse model could be indirect. We were unable to directly demonstrate fusion, as histological evidence for direct axonal fusion using light microscopy or EM is not feasible in this context. Compound action potential (CAPs) are evoked action potentials extracellularly recorded from a set of axons. CAPs can be evoked to access electrophysiological function and continuity across the lesion site, thus evaluating PEG-fusion success76. It would be helpful to measure CAPs to confirm the effects of ML162 and GPX4 depletion on axonal fusion. Also, future studies are needed to identify which neurons can be induced to undergo fusion in response to ferroptosis signaling.

We show that PSR-1 forms condensates on the membrane at the tip of the growing axon in response to axon injury. PSR-1 condensates are sensitive to the reducing agent DTT and disruption of PSR-1 condensation with 1,6-HD resulted in reduced axonal fusion. Thus, PSR-1 condensation potentially serves as a mechanism to elevate its local concentration to facilitate the reconnection of the regenerative axon with the distal fragment. However, future studies are needed to determine whether the interaction between PS and PSR-1 can modulate PSR-1 condensation and whether other membrane proteins (e.g. EFF-1) co-condensate with PSR-1.

Methods

Experimental animals

C. elegans strains were maintained on standard NGM plates seeded with OP50 E.coli at 20 Celsius degree. C. elegans strains used in this study were obtained from the Mitani Laboratory or from the C. elegans Genetics Center which is funded by NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440). Transgenic animals were generated by microinjection of 10 ng/μl plasmid DNA and 90 ng/μl Pttx‐3‐rfp plasmid as a co‐injection marker unless otherwise noted. At least two lines were tested for each transgene. Mouse care and experimental procedures were in full accordance with the IACUC guideline of University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. Mice were housed in a vivarium maintained on a 12 h light/dark cycle, at 75 °F, with 40–60% relative humidity. FVB/NJ (Strain #: 001800) and Avil-Cre-ER (Strain #: 032027) mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. Gpx4 cKO allele (generated by QR group) was crossed to Avil-Cre-ER to generate sensory neuron-specific Gpx4 KO mice.

Laser axotomy in C. elegans

Laser axotomy37,38 was performed as followed. Adult Day 1 animals (or animals of indicated stages) were immobilized with 0.7% phenoxypropanol on agarose pads in batches of 12 animals per slide. GFP labeled axons were visualized with an Olympus IX83 microscope using a 100x objective. PLM axons were axotomized at 50 µm from the cell body of PLM using a Micropoint UV laser (Andor Technology, Oxford Instrument). Axotomized animals were recovered to agar plates and remounted 24 h later for scoring. All experiments were performed in parallel with a matched control. At least 20 animals were axotomized and 10 axons were measured using ImageJ for each genotype.

FIs, FINs, Hydrogen peroxide, Necrostatin-1 and z-VAD-FMK treatment

Ferroptosis inducers (FIs) such as ML210, ML162, RSL3, and Ferroptosis inhibitors (FINs) such as ferrostatin-1, liproxstatin-1 (SML1414, Sigma), N-acetyl-L-cysteine (A7250, Sigma) were dissolved in DMSO and added to the NGM agar plate at an indicated concentration in the figure above. Hydrogen peroxide (216763, Sigma) was diluted to indicated concentration in the figure, and 400 μl of diluted hydrogen peroxide was added to the NGM plate. The doses of the inducers/inhibitors of the cell death pathways were initially selected based on literature reports of functional doses (i.e., those that have been shown to induce ferroptosis, apoptosis or necrosis). We then tested these doses and observed their outcomes, such as cell death and axonal debris. Gradually, we reduced the doses, attempting to identify the effective concentrations that promoted axonal fusion. Necrostatin-1 (HY-15760, MedChemExpress, Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA) and z-VAD-FMK (A1902, APExBIO, Boston, MA, USA) were diluted to 5 μM with water, and 400 μl of diluted reagent was applied onto each NGM plate. Immediately after axotomy, animals were cultured on NGM plates with reagents above or vehicle control for 24 h at 20 °C. The dose of ML162 used in the mouse model was determined by our pilot studies using various concentrations of H2O2. We initiated with 100 mM of H2O2, followed by 10 mM, 2 mM and 1 mM. We found that treatment with 1-2 mM H2O2 + 500 mM PEG resulted in the best behavior scores. As 3 mM of H2O2 has a fusion-promoting effect equivalent to 0.5 µM ML162 in C. elegans, we decided to test ML162 at 0.25 µM in the mouse model.

Live imaging of vesicles trafficking across the fusion site

Live imaging of synaptic vesicles was performed 24 h after axotomy. Movie were taken on an Olympus IX83 for 5 min. Trafficking of synaptic vesicles were determined with the software Kymograph of Olympus IX83. Kymographs are a two-dimensional display of a movie whereby a line scan of each movie frame is sequentially assembled to show behavior of synaptic vesicles over time. The x-axis represents space along the process, whereas the y-axis represents time.

Gentle touch assay to evaluate function recovery in C. elegans

For analysis of gentle touch response, a modified version of the light touch assay103 was used to evaluate the functional recovery of fused PLM neurons. One PLM neuron of the adult Day 1 animal was laser-ablated, and the animals recovered on OP50 seeded NGM agar plates for 36 h before testing. Each animal was touched once on the anterior half of the body with an eyebrow hair mounted on a worm picker, and only worms moving backward in response to the anterior touch was touched again once on the posterior half. This was repeated for a total of 10 times for each animal. Only the response to posterior touch was quantified as PLM axotomy does not affect touch response to the anterior touch17. In response to the gentle touch, a movement of more than the body length was defined as a full response, no movement at all as no response, and a movement of less than the body length as a partial response. We quantified full response as 1, no response as 0, and partial response as 0.5.

Quantification of annexin V, HyPer and RoGFP

To measure PS exposure of touch neuron, Annexin V was expressed under the control of the touch neuron-specific mec-4 promoter. PS exposure bound with mKate2-tagged Annexin V was visualized with Olympus IX83 inverted microscope. Fluorescence intensities of distal axon segments were measured using ImageJ software. mKate2 expression 1 h post-axotomy was calculated relative to expression levels in the same axon fragment immediately before axotomy.

To examine cellular H2O2 and ROS levels, HyPer and RoGFP reporters were expressed under the control of mec-4 promoter respectively. HyPer is a fluorescent biosensor capable of detecting intracellular hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) through the H2O2-sensitive regulatory domain of the Escherichia coli (E. coli) transcription factor OxyR with the circularly permuted YFP (cpYFP)49. roGFP2-Orp1 is a fluorescent peroxide sensor which is a redox-sensitive green fluorescent protein (roGFP) variant roGFP2 artificially fused with H2O2 sensing peroxidase Orp152. Images of PLM expressing HyPer and RoGFP reporters were obtained using Olympus IX83 inverted microscope and fluorescence intensities were measured using Image J.

Protein purification and in vitro droplet formation assays

Constructs used for protein purification were generated through gateway LR recombination between entry clones containing PSR-1, PSR-1(ΔCTD) or EFF-1 cDNA and destination vector modified from pET-His-GFP-MED1104 (gift from Richard Young Lab). E. coli Rosetta (DE3) competent cells were used as the host strain for protein expression. The cells were transformed with PSR-1, PSR-1(ΔCTD) or EFF-1 plasmids and protein expression was induced with 0.1 mM IPTG in Luria Broth (LB) containing 1% glucose, 1X kanamycin, and 0.5X chloramphenicol. The culture was grown overnight at 18 °C and pelleted at 3000 rpm for 10 min and either proceeded fresh to lysis or stored at −80 °C. The cells were lysed in a Buffer A (50 mM Tris- HCl, pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche)) and subjected to sonication. The total cell lysate was centrifuged at 20,000 rpm for 30 min at 4 °C, and the soluble fraction was loaded onto a Ni-NTA agarose resin column (Qiagen) that was pre-equilibrated with Buffer A. The resin-bound protein was washed successively with Buffer A and finally eluted with the elution buffer containing a gradient increase in the concentration of Imidazole (50 mM Tris-HCL, pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl and 50 mM/100 mM/250 mM Imidazole). The eluted proteins were confirmed by running on a 12% SDS Gel, and the proteins were pooled together and subjected to overnight dialysis (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 125 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol and 1 mM DTT) at 4 °C. The dialyzed proteins were concentrated using the 3 K centricon (Millipore, Sigma) and either proceeded fresh for the droplet formation assays or aliquoted and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. The purified protein was diluted to 40 mM, 20 mM, 10 mM and 5 mM using the dialysis buffer (50 mMTris pH 7.5, 125 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol and 1 mM DTT).

The protein was mixed in a 1:1 ratio with droplet formation buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 125 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1 mM DTT, with 20% or 40% PEG8000) and 2 µl of the suspension was loaded onto a hand-made cassette with a clean glass slide, spacers, and a coverslip. The droplets were immediately observed under an upright confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM780) using a 10x or 100x/1.4 oil objective. ZEN black edition version 2.3 was used for acquisition.

Mouse sciatic nerve transection/resuture and drug treatment

Surgical experiments were performed using adult mice (8 to 10 weeks old). Both male and female mice were used and no obvious difference was observed between male and female animals. A group size of 4–6 each provided statistical power to detect differences of p < = 0.05 of >= 20% between an experimental and a control group105. Animals were randomly allocated to experimental groups, and surgical procedures were performed under isoflurane anesthesia of SomnoSuite low-flow anesthesia system (Kent Scientific, Torrington, CT, USA). Animals were placed on a heated pad in a position where the sciatic nerve can be observed under a stereo dissecting microscope. The right sciatic nerve was exposed below the sciatic notch (mid-tight level) under sterile conditions. The sciatic nerve was penetrated twice with a 10-0 nylon suture before amputation to minimize damage from the resuture procedure. Then, the sciatic nerve between the perforated threads was cut and immediately washed with Ca2+ free phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), followed by gently tying the suture thread (Fig. S5A). 0.25 µM of ML162 in PBS, 500 mM of PEG in PBS, or both were applied to the suture site for 1 min, followed by PBS rinse. All steps, from penetration to PBS rinse, were performed under a stereo dissecting microscope. The incision wound was then closed with sutures and the animals were placed on a heated pad for recovery.

Immunohistochemistry, NMJ analysis and quantification of DRG axon regeneration