Abstract

p85β is a regulatory subunit of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K). Emerging evidence suggests that p85β goes beyond its role in the PI3K and is functional in the nucleus. In this study, we discover that nuclear p85β is enriched at gene loci and regulates gene transcription and that this regulatory role contributes to the oncogenic potential of nuclear p85β. A multi-omics approach reveals the physical interaction and functional cooperativity between nuclear p85β and a transcription factor BCLAF1. We observe genome-wide co-occupancy of p85β and BCLAF1 at gene targets associated with transcriptional responses. Intriguingly, the targetome includes BCLAF1 of which transcription is activated by p85β and BCLAF1, indicating a positive autoregulation. While BCLAF1 recruits p85β to BCLAF1 loci, p85β facilitates the assembly of BCLAF1, the scaffold protein TRIM28 and the zinc finger transcription factor ZNF263, which together act in concert to activate BCLAF1 transcription. Collectively, this study provides functional evidence and mechanistic basis to support a role of nuclear p85β in modulating gene transcription.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The p85 regulatory subunit of the heterodimeric class IA phosphoinositide-3 kinases (PI3K) has two isoforms: p85α (PIK3R1) and p85β (PIK3R2)1. Growing evidence has shown that p85 exhibits activities apart from its canonical role in regulating p110 and that in contrast to p85α which is tumor suppressive, p85β promotes oncogenic transformation2,3,4. We are only beginning to unravel the molecular mechanisms underlying the oncogenicity of p85β. p85β has been shown to promote melanoma invasion through Rho GTPases5. Our group demonstrated that in ovarian cancer, p85β regulates the autophagy pathway to inhibit protein degradation of the receptor tyrosine kinase AXL, which induces p110/PDK1/SGK3 signaling axis and thereby ovarian tumorigenesis6. Interestingly, the contrasting functional roles of p85α and p85β are echoed by the distinct expression patterns of the two isoforms in cancers. Reduced p85α expression or loss-of-function PIK3R1 gene aberrations are frequent. Conversely, p85β is often overexpressed in multiple cancer types4,5. Further, p85α predominantly localizes to the cytosol, but p85β can be found in the nucleus in addition to the cytosol5,7. However, how the subcellular distribution underlies the functions of p85β is not fully understood. Interactions between p85 and nuclear proteins have been reported for the regulation of unfolded protein response (UPR). p85α and p85β bind to XBP1 and facilitate the nuclear translocation of XBP18,9. XBP1 is a transcription factor that modulates UPR to restore endoplasmic reticulum (ER) homeostasis. This interaction between p85 and XBP1 can be stimulated by insulin but becomes defective in the context of ER stress, obesity, insulin resistance or diabetes8,9,10. It was later discovered that p85 binds to another nuclear protein BRD7 and that p85 is crucial for connecting XBP1 to BRD7, which in turn increases the nuclear import and the transcription activity of XBP111,12.

BCLAF1 (Bcl-2-associated transcription factor 1) was first discovered as a binding protein for the adenoviral Bcl2 homolog and a repressor of transcription13,14. Subsequent studies have demonstrated that BCLAF1 can also activate transcription15,16,17,18,19. BCLAF1 can bind directly to DNA and mediate interaction of the bound proteins with the target sequence17. Alternatively, BCLAF1 can be recruited to regulatory motifs through tethering to other transcription factors14,15,18. So far, studies have indicated that BCLAF1 can be tumor suppressor or oncogene in different cancer types. BCLAF1 promoted apoptosis of lung cancer cells through inhibiting p21 and autophagic cell death in myeloma20,21. On the contrary, in liver cancer, BCLAF1 induced HIF1A transcription and angiogenesis16. Oncogenic activity of BCLAF1 was also observed in colon cancer and acute myeloid leukemia through mechanisms yet to be uncovered22,23. Here we report BCLAF1 as one of the mediators of nuclear p85β. The data provide insights into the mechanistic action of p85β and BCLAF1 in the nucleus that contributes to gene transcription regulation and tumorigenesis.

Results

Nuclear p85β is oncogenic

First, we examined the subcellular distribution of p85β in ovarian cancer cells. Ovarian cancer cells were chosen as cell model because of the frequent PIK3R2 amplification and the demonstrated oncogenicity of p85β in the disease6. Using immunofluorescence and subcellular fractionation, endogenous p85β was detected in the cytoplasm and nucleus in two ovarian cancer cell lines (OVCAR8 and SKOV3) (Fig. 1A, B). In contrast, p85α localized predominantly in the cytoplasm (Fig. 1A, B).

A Immunofluorescence staining of p85β (red; left panel), p85α (green; right panel) in OVCAR8 and SKOV3 cells. Nuclei (blue) were stained with DAPI. Scale bar, 10 µm. B Subcellular fractions were isolated and immunoblotted for p85β and p85α. GAPDH and lamin A/C served as markers of the cytoplasm and nucleus respectively. DOV13 or SKOV3 cells stably expressing PIK3R2 (R2-OX) or PIK3R2 with nuclear export signal (NES) at N-terminal (NES-R2-OX) or empty vector control (Vector) were subjected to (C) total protein harvest and western blotting with ERK2 as loading control, (D) subcellular fractionation, (E) cell viability assay, (F) colony formation assay, or transwell assay for (G) cell migration and (H) cell invasion capabilities. Scale bar, 200 μm (DOV13) or 100 μm (SKOV3). Assays in (E) were done in triplicates and data are shown as mean ± SD. The numbers of cells on the transwell membrane were counted in 5 random fields and data represent mean ± SD (G, H). All data and images shown are representative of 3 independent experiments, except that the bar graph in (F) shows the mean colony number ± SD from three independent experiments. The numbers below the western blots are densitometry values normalized to the loading control, except for those in (B), which are normalized to the cytosolic level. The P-values shown were calculated using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To determine whether nuclear p85β is oncogenic, a classical leucine-rich nuclear export signal (NES; LALKLAGLDI)24 was added at the N-terminal of p85β. Wild-type (WT) p85β or NES-p85β was stably expressed in DOV13 and SKOV3 cells, which express low or moderate endogenous p85β protein levels respectively. The total expression levels of WT p85β and NES-p85β in the cells were comparable but fractionation experiments showed that the abundance of NES-p85β was markedly reduced in the nucleus (Fig. 1C, D), indicating the effectiveness of the NES addition. Importantly, while overexpressing WT p85β promoted oncogenic phenotypes (cell viability, colony formation, migration and invasion) as previously demonstrated2,3,4,5,6,7, the ability of NES-p85β to promote these phenotypes was significantly reduced (Fig. 1E–H), suggesting that nuclear p85β contributes to the oncogenicity of p85β. We investigated whether the hampered phenotypes in NES-p85β-expressing cells were due to alteration of p110 or inhibition of the downstream pro-survival signaling. First, the expression of NES-p85β had no effect on the protein levels and localization of p110 (Supplementary Fig. 1A, B). Second, similar to WT p85β, NES-p85β did not alter the binding between endogenous p110α and p85 (Supplementary Fig. 1C). This observation, which aligns with the unchanged p110 protein level since binding is associated with p110 protein stabilization, could be explained by the notion that endogenous p85 is more abundant than p11025,26. Third, NES-p85β and WT p85β demonstrated a comparable level of binding to p110 (Supplementary Fig. 1D). Lastly, we previously reported that p85β activates PDK1/SGK3 signaling through AXL6. NES-p85β could induce PDK1 and SGK3 phosphorylation similar to that seen in WT p85β (Supplementary Fig. 1E).

We next expressed WT p85β and NES-p85β in WT mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) and MEFs deficient in all p85α and p85β gene products (p85α−/− p55α−/− p50α−/− p85β−/−; thereafter denoted as p85−/− MEFs)27 (Supplementary Fig. 2A, B). As shown in Supplementary Fig. 2C, p110 protein levels and activity of downstream signaling (PDK1 and SGK3) were found to be similar after the expression of WT p85β and NES-p85β in these cells. Yet, NES-p85β showed a compromised ability to promote cell viability, colony formation, migration and invasion when compared with WT p85β in both WT MEFs and p85−/− MEFs (Supplementary Fig. 2D-G). Together, these data imply that the reduced oncogenic manifestations conferred by NES-p85β are not due to suppression of the endogenous p85 protein or PI3K signaling.

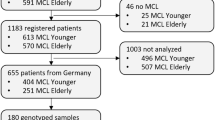

Nuclear p85β increases BCLAF1 protein level

Next, we mined the transcriptomic and proteomic data generated from PIK3R2 knockdown cells in an attempt to understand the mechanistic action of p85β. Figure 2A depicts the analyses we conducted. First, RNA-seq revealed 589 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) commonly found in both OVCAR4 and OVCAR8 transfected with two independent PIK3R2 siRNAs, with 242 upregulated DEGs (fold change >1.5, P < 0.05) and 347 downregulated DEGs (fold change <0.67, P < 0.05). To gain insight into the potential transcription factors that mediate these transcriptomic changes, transcription factor enrichment analysis was performed using Enrichr (https://maayanlab.cloud/Enrichr/)28 which resulted in a prediction of 24 transcription factors. Because transcription factor activity can be regulated through expression levels and/or phosphorylation modifications29, we hypothesized that PIK3R2 may alter the activity of transcription factor(s) which in turn generates the observed transcriptomic changes. We thus analyzed mass spectrometry-based proteome and phosphoproteome data of these 24 transcription factors in PIK3R2 siRNA-transfected SKOV3 cells (published by our group previously6). Interestingly, 13 out of 24 transcription factors showed changes at the total protein and/or phosphorylation level upon PIK3R2 depletion (fold change >1.5 or <0.5) (Fig. 2B).

A Outline of the analyses to identify potential downstream effectors that mediate the transcriptional changes induced by p85β. B Heatmap showing the 13 transcription factor candidates from transcription factor enrichment analysis and with total and/or phosphorylated protein level changes after PIK3R2 knockdown. Names of the transcription factors are listed on the left of the heatmap and the detected phosphosites are on the right. Phosphosites with antibodies commercially available are marked with asterisks. C Transcription factor candidates with phosphorylation changes determined by mass spectrometry were examined by western blotting with cells transfected with 4 independent sequences of PIK3R2 siRNA for 72 h. ERK2 was loading control. D Total protein lysates of OVCAR8 and SKOV3 cells transfected with PIK3R2 siRNA for 72 h or DOV13 cells stably expressing PIK3R2 (R2-OX) or vector control were subjected to western blotting. E, F Subcellular fractionation was performed with (E) DOV13 stable cells or (F) SKOV3 cells transfected with PIK3R2 siRNA for 72 h prior to western blotting with GAPDH and lamin A/C as markers of the cytoplasm and nucleus respectively. G OVCAR8 cells were transfected with two PIK3R2 siRNA targeting the 5’ UTR for 24 h prior to lentivirus-mediated overexpression of PIK3R2 for another 48 h. H DOV13 or SKOV3 cells stably expressing PIK3R2 (R2-OX) or PIK3R2 with nuclear export signal (NES) at N-terminal (NES-R2-OX) or vector control were subjected to western blotting. I Serous ovarian tumor samples (n = 49) were examined by immunohistochemical staining for p85β and BCLAF1. Left, representative images and their magnified areas are shown. Scale bar, 50 μm. Right, immunostaining scores of BCLAF1 and nuclear p85β or cytoplasmic p85β were analyzed for Pearson’s correlation coefficient r with two-tailed P-value and are depicted in scatter plot. The western blots are representative of n = 3 biological replicates and densitometry values normalized to the loading control are shown (C–H). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Phosphorylation changes of 7 transcription factors with commercially available antibodies were examined using western blots (Fig. 2C). STAT3 was included as a negative control; its total protein or phosphorylation (S727) level was unchanged as shown by mass spectrometry. Consistent with the phosphoproteomic data, the phosphorylation levels of BCLAF1 at S512 could be confirmed in both OVCAR8 and SKOV3 upon PIK3R2 silencing using 4 independent siRNAs (Fig. 2C). In contrast, phosphorylation changes of the other proteins were less consistent. Indeed, PIK3R2 depletion led to decreases in multiple phosphorylation sites of BCLAF1 (Supplementary Fig. 3A), suggesting a possibility that decreased total protein level causes these phosphorylation changes. Remarkably, the levels of total BCLAF1 protein echoed that of the phosphorylated form. The protein levels of total BCLAF1 were downregulated by PIK3R2 knockdown and were upregulated upon PIK3R2 overexpression (Fig. 2D). We also noted a lower total BCLAF1 total protein level in the p85−/− MEFs compared with the WT MEFs (Supplementary Fig. 2A). Concordant with the fact that BCLAF1 predominantly localizes in the nucleus, the altered protein levels upon PIK3R2 knockdown or PIK3R2 overexpression were manifested in the nuclear fractions (Fig. 2E, F). To determine the specificity of the regulation, PIK3R2 5’ UTR-targeting siRNA and PIK3R2 overexpression plasmid were co-transfected into the cells. This rescue experiment demonstrated that PIK3R2 overexpression could reverse the effects of PIK3R2 silencing on BCLAF1 protein level (Fig. 2G), indicating the specificity. Further, the other p85 isoform (p85α) does not regulate BCLAF1 because PIK3R1 siRNA had no effect on BCLAF1 protein level (Supplementary Fig. 3B).

We then explored the effect of nuclear p85β on the regulation of BCLAF1. Strikingly, in contrast to WT p85β, NES-p85β failed to increase BCLAF1 protein level (Fig. 2H), suggesting that the regulation is mediated by nuclear p85β. Immunohistochemistry study with a set of ovarian cancer patient samples (n = 49) also revealed a positive correlation between nuclear p85β and nuclear BCLAF1 levels (Pearson’s correlation coefficient r = 0.51, P = 0.0002) (Fig. 2I). Such correlation was not seen between cytoplasmic p85β and nuclear BCLAF1. Notably, this regulation of BCLAF1 by p85β does not involve p110. First, knockdown of PIK3CA (p110α), PIK3CB (p110β), PIK3CD (p110δ) or PIK3CG (p110γ) had no effect on the increased levels of BCLAF1 pS512 or total BCLAF1 in p85β-overexpressing cells (Supplementary Fig. 3C). Second, nuclear translocation of p85β was not affected by any of the p110 isoforms (Supplementary Fig. 3D).

BCLAF1 partially mediates the oncogenicity of p85β

To evaluate the contribution of BCLAF1 to p85β oncogenicity, empty vector- or p85β-overexpressing DOV13 cells were transfected with BCLAF1 siRNA (Fig. 3A). Intriguingly, similar to NES-p85β, silencing BCLAF1 inhibited p85β-induced oncogenicity including cell migration and invasion (Fig. 3B, C). In another set of experiment, we silenced BCLAF1 in OVCAR8 mock or PIK3R2-depleted cells (Fig. 3D). BCLAF1 siRNA led to significantly reduced cell migration and invasion in the mock cells (Fig. 3E, F). However, BCLAF1 siRNA did not cause further reduction when combined with PIK3R2 siRNA, suggesting that p85β and BCLAF1 are along the same pathway axis. Also, although BCLAF1 single knockdown resulted in a greater reduction of BCLAF1 protein than PIK3R2 single knockdown, the inhibition of the phenotypes was more potent with PIK3R2 single knockdown. This implies the existence of other mediators of p85β oncogenicity besides BCLAF1. Reconstitution of BCLAF1 expression partially rescued the deceased cell migration and invasion upon PIK3R2 knockdown (Supplementary Fig. 4A, B), again implicating that BCLAF1 and p85β act in the same pathway and that BCLAF1 contributes partly to p85β oncogenicity.

A–C DOV13 stable cells expressing vector or PIK3R2 (R2-OX) were transfected with BCLAF1 siRNA for 72 h, followed by (A) western blotting for the knockdown efficiency with ERK2 as loading control, or (B) cell migration assay, or (C) cell invasion assay. D–F OVCAR8 cells were transfected with PIK3R2 siRNA or BCLAF1 siRNA alone or in combination for 72 h. Cells were harvested for (D) western blotting, (E) cell migration or (F) invasion assay. G, H DOV13 stable cells expressing vector or PIK3R2 (R2-OX) were transfected with BCLAF1 siRNA. Cells were subjected to (G) cell viability assay or (H) cell cycle analysis. I–L DOV13 and OVCAR8 cells stably expressing BCLAF1 (BCLAF1-OX) or vector control were harvested for (I) western blotting, (J) cell viability assay, (K) cell migration assay, or (L) invasion assay. Assays in (G, J) were done in triplicates and data are shown as mean ± SD. The numbers of cells on the transwell membrane were counted in 5 random fields and data represent mean ± SD (B, C, E, F, K, L). Data and images shown are representative of 3 independent experiments, except data in H which shows the mean of 3 independent experiments ± SD. The numbers below the western blots are densitometry values normalized to the loading control. Scale bar, 200 μm (B, C, K, L); 100 μm (E, F). The P-values shown were calculated using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test (B, C, E–H) or two-tailed t-test (J–L). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We next examined the potential role of BCLAF1 in cell viability and cell cycle progression. After knockdown of BCLAF1, viability and colony formation of empty vector- or p85β-overexpressing DOV13 cells were inhibited (Fig. 3G; Supplementary Fig. 4C). Also, flow cytometry analysis demonstrated that BCLAF1 depletion delayed cell cycle progression (Fig. 3H). The effects of BCLAF1 on these phenotypes are not attributed to an altered p85β expression level or subcellular localization. Silencing BCLAF1 did not affect the total protein level (Supplementary Fig. 4D) or subcellular distribution of p85β (Supplementary Fig. 4E). The functional role of BCLAF1 in ovarian cancer was further determined by overexpressing BCLAF1 in DOV13 and OVCAR8 cells (Fig. 3I). The expression of BCLAF1 significantly promoted cell viability, colony formation, cell migration and invasion (Fig. 3J–L; Supplementary Fig. 4F).

Regulation of BCLAF1 by p85β is at transcriptional level

After establishing BCLAF1 as mediator of the oncogenicity of p85β, we sought to investigate the regulatory mechanism of BCLAF1 by p85β. We have recently demonstrated that p85β regulates protein stability of AXL through autophagy pathway. To address if AXL signaling is involved in the regulation of BCLAF1, and/or BCLAF1 may in turn regulate AXL expression, BCLAF1 or AXL expression was depleted by specific siRNA respectively. The results showed that in parental or p85β-overexpressing cells, inhibition of BCLAF1 did not affect the expression of AXL and vice versa (Supplementary Fig. 5A, B). Therefore, p85β-mediated regulation on AXL and BCLAF1 are likely two independent events. Next, cycloheximide (CHX)-chase experiment was performed to examine whether the half-life of BCLAF1 protein is regulated by p85β. However, the degradation rate of BCLAF1 protein was unaffected by PIK3R2 knockdown (Fig. 4A; Supplementary Fig. 5C). In parallel experiments, protein levels of AXL were analyzed as positive control. PIK3R2 knockdown reduced AXL protein stability as previously reported6 (Fig. 4A). These results together indicate that the regulatory mechanism of BCLAF1 by p85β is distinct from that of AXL. A previous study reported that nuclear p85β promotes the protein stability of histone methyltransferase EZH1/2 through recruiting deubiquitinase USP7 to EZH1/230. We therefore explored whether USP7 is involved in the regulation of BCLAF1 by p85β. As shown in Supplementary fig. 6, knockdown of USP7 did not alter BCLAF1 protein levels in empty vector- or p85β-overexpressing cells. We then determined whether p85β modulates BCLAF1 mRNA expression and observed a reduction of BCLAF1 mRNA level in PIK3R2-depleted cells (Fig. 4B). Complementarily, PIK3R2 overexpression increased BCLAF1 mRNA level (Fig. 4B). In line with the effects on mRNA expression, luciferase reporter assays showed that the promoter activity of BCLAF1 was reduced upon PIK3R2 depletion but was increased by PIK3R2 overexpression (Fig. 4C). BCLAF1 mRNA level or promoter activity remained unchanged by PIK3R1 siRNA (Supplementary Fig. 7A, B).

A SKOV3 cells were transfected with PIK3R2 siRNA for 60 hr, followed by treatment of 20 μg/mL cycloheximide (CHX) for the indicated time course. ERK2 was a loading control. The mean densitometry values ± SD of BCLAF1 or AXL levels normalized with that of ERK2 from three independent experiments are plotted. B Real-time PCR analysis of BCLAF1 mRNA expression in (left) ovarian cancer cell lines with PIK3R2 silencing (R2 si) for 72 h or (right) DOV13 stable cells expressing vector (Vector) or PIK3R2 (R2-OX). C Left, OVCAR8, OVCAR4 and SKOV3 cells were transfected with PIK3R2 siRNA for 48 h prior to co-transfection of pRL-TK Renilla luciferase plasmid and human BCLAF1 promoter luciferase plasmid or pGL3-Basic plasmids for another 48 h. Right, SKOV3 stable cells expressing vector or PIK3R2 (R2-OX) were transfected with the luciferase plasmids for 48 h. D Real-time PCR analysis of BCLAF1 mRNA expression in DOV13 cells stably expressing PIK3R2 (R2-OX) or PIK3R2 with nuclear export signal (NES) at N-terminal (NES-R2-OX) or vector control. E SKOV3 R2-OX or NES-R2-OX or vector-expressing cells were transfected with pRL-TK Renilla luciferase plasmids and human BCLAF1 promoter luciferase plasmid or pGL3-Basic plasmids for 48 h prior to dual luciferase reporter assay. F Cross-linked chromatin from DOV13 cells stably expressing PIK3R2 was immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibody or rabbit IgG control. The precipitated DNA was analyzed by real-time PCR using BCLAF1 promoter-specific primers. The blots in (A) and data shown in (B, D) are representative of three independent experiments and data represent mean ± SD. Each individual data point in (C, E, F) represents the average of triplicates from one independent experiment; therefore, the data shown (mean ± SD) are from three independent experiments. P-values were calculated using two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparison test (A), one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test (B left, C left, D, E) or two-tailed t-test (B right, C right, F). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Next, the role of nuclear p85β in the transcriptional regulation was evaluated. Consistent with the data that NES-p85β could not induce BCLAF1 protein level, the mRNA level and promoter activity of BCLAF1 were barely influenced in NES-p85β-expressing cells (Fig. 4D-E). To investigate the possibility that nuclear p85β directly regulates BCLAF1 gene transcription by binding to BCLAF1 promoter, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays with anti-HA antibody against HA-tagged p85β expressed in the cells because there is no validated ChIP-grade anti-p85β antibody. Real-time PCR with primers targeting regions within the BCLAF1 promoter luciferase reporter was performed. Normal IgG and input DNA were used as negative and positive controls respectively. Surprisingly, enrichment of p85β at BCLAF1 promoter could be detected (Fig. 4F). In the control assay, nonspecific IgG did not immunoprecipitate BCLAF1 DNA. Together these results suggest that nuclear p85β, which is enriched at BCLAF1 promoter, regulates the transcription of BCLAF1.

p85β and BCLAF1 co-occupy BCLAF1 genomic loci

Sequence homology search of the p85β protein did not reveal any potential DNA binding protein domain, we therefore speculated that p85β may activate BCLAF1 promoter activity through interaction with other proteins. To identify p85β-bound nuclear proteins that mediate DNA binding, we performed immunoprecipitation (IP) using anti-p85β antibody prior to mass spectrometry (MS) profiling. The interactome revealed 50 proteins that localize in the nucleus and have been previously implicated in transcription control and/or DNA binding (Fig. 5A; Supplementary Data 1). Interestingly, BCLAF1 was one of these p85β interaction partners. IP validation experiments using whole cell lysates or nuclear extracts confirmed the interaction between p85β and BCLAF1 (Fig. 5B, C). There was no detectable interaction between p85α and BCLAF1 (Fig. 5B), suggesting a specificity of interaction. Of note, in contrast to previous studies8,9,10,11,12, we did not detect binding between p85β and XBP1 or BRD4 in our IP-MS profiling, suggesting the possibility of context-dependent protein interaction.

A The dots in the scatterplot of Andromeda scores (at an arbitrarily cut-off of 10) represent p85β-interacting proteins detected with one or more unique peptides by mass spectrometry and with reported roles in transcriptional regulation in the nucleus. B Total protein lysates of OVCAR8 and SKOV3 cells were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-p85α antibody or anti-p85β antibody. IP with normal IgG was control. C Nuclear extract of DOV13 stably expressing PIK3R2 were subjected to IP with anti-p85β antibody. D ChIP-seq was performed using anti-HA antibody or anti-BCLAF1 antibody in DOV13 cells stably expressing PIK3R2. ChIP-seq tracks for HA and BCLAF1 over the BCLAF1 gene and input signal are shown. E Cross-linked chromatin from DOV13 cells stably expressing PIK3R2 was immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibody or anti-BCLAF1 antibody or rabbit IgG. DNA fragments were amplified with primers for (left) BCLAF1 promoter, (middle) locus 1 and (right) locus 2. F ChIP-PCR analysis of chromatin enrichment of HA (p85β) at the BCLAF1 loci in DOV13 stably expressing PIK3R2 transfected with BCLAF1 siRNA for 72 h. G, H re-ChIP experiments were performed using (G) anti-BCLAF1 antibody and anti-HA antibody or IgG control, or (H) anti-HA antibody and anti-BCLAF1 antibody or IgG control. I Cells were transfected with PIK3R2 siRNA or BCLAF1 siRNA alone or in combination for 48 h prior to co-transfection of Renilla luciferase plasmid and BCLAF1 promoter luciferase reporter or pGL3-Basic plasmid for another 48 h. The blots in (B, C) are representative of three independent experiments. The ChIP-seq data in (D) are from triplicates and the experiment was done once. Each individual data point in (E–I) represents the average of triplicates from one independent experiment; therefore, the data shown (mean ± SD) are from three independent experiments. P-values were calculated using two-tailed t-test (E left, G, H) or one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test (E middle and right, I) or two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test (F). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The observations that p85β and BCLAF1 physically interact in the nucleus prompted us to investigate whether p85β and BCLAF1 bind cooperatively to the genome. First, to analyze the genome-wide occupancy of p85β and BCLAF1, ChIP-seq was performed using anti-HA or anti-BCLAF1 antibody respectively. Interestingly, consistent with the ChIP-PCR data which demonstrated the enrichment of p85β at BCLAF1 promoter (Fig. 4F), the ChIP-seq analysis also revealed that BCLAF1 itself was able to bind to its own promoter and the bound regions colocalized with that of p85β (Fig. 5D). In addition, we found two other overlapping binding sites of p85β and BCLAF1 that were located upstream of the BCLAF1 promoter. The binding could be validated by ChIP-PCR (Fig. 5E). Remarkably, knockdown of BCLAF1 diminished the occupancy of p85β at these BCLAF1 loci (Fig. 5F), indicating that p85β is tethered to the loci at least partially through BCLAF1. To examine whether p85β and BCLAF1 bind to the loci regions in a same complex, we performed two sets of sequential ChIP (re-ChIP) experiments. In one set, DNA was first immunoprecipitated with anti-BCLAF1 antibody and the eluant was then immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibody (Fig. 5G). In another set, the sequence of the antibodies was reversed (Fig. 5H). IgG was used as a second antibody in control experiments. These re-ChIP assays confirmed that p85β and BCLAF1 co-localized to BCLAF1 gene loci in the same protein complex (Fig. 5G, H). Next, we assessed the functional significance of the co-localization on BCLAF1 promoter activity. Transcriptional autoregulation of BCLAF1 promoter is supported by the finding that BCLAF1 siRNA led to reduced BCLAF1 promoter activity (Supplementary Fig. 8). Combined knockdown of PIK3R2 and BCLAF1 could achieve stronger inhibition effect on BCLAF1 promoter activity compared with single knockdown (Fig. 5I). This aligns with the results on BCLAF1 protein levels as shown by western blots (Fig. 3D). Taken together, these findings indicate that p85β and BCLAF1 have cooperative functions in regulating gene promoter activity.

Co-regulated genes are enriched in proliferation and migration

We further analyzed the ChIP-seq data to identify genome-wide binding sites of p85β and BCLAF1. We mapped a total of 5485 p85β peaks and 5261 BCLAF1 peaks. The p85β or BCLAF1 peak calls were centered around annotated transcription start site (TSS) (Fig. 6A) and existed most frequently at promoter regions (Fig. 6B). When we assessed the overlap of the p85β and BCLAF1 peaks, we found that 16.8% (920 out of 5485) of the p85β-enriched regions were also occupied by BCLAF1 (Fig. 6C). The overlapping peaks were found to be enriched (>60%) in regions within a 1 kb distance of the TSS, especially downstream from the TSS (Fig. 6D, E). These 920 shared ChIP-seq peaks were assigned to 725 genes using the nearest gene approach. De novo motif deduction and motif comparison using MEME31,32 and TOMTOM31,33 revealed that the top three motifs that are statistically enriched in the overlapping peaks are best known as the binding sites for FOXP1 (P = 0.002), ZNF263 (P = 0.0006) and EGR1 (P = 0.0004) (Fig. 6F).

A ChIP-seq was performed using anti-BCLAF1 antibody or anti-HA antibody in DOV13 cells stably expressing PIK3R2. Average plot (top) and heatmap (bottom) of BCLAF1 or HA-p85β ChIP-seq read density within ±3 kb from an annotated transcription start site (TSS) are shown. B Top, distribution of BCLAF1 or HA-p85β ChIP-seq peaks relative to the closest TSS. Bottom, pie charts showing distribution of annotated genomic features of BCLAF1 or HA-p85β ChIP-seq peaks. C Venn diagram of overlapping binding regions between BCLAF1 and HA-p85β. D Top, distribution of BCLAF1 and HA-p85β overlapping ChIP-seq peaks relative to the closest TSS. Bottom, distribution of annotated genomic features of BCLAF1 and HA-p85β overlapping ChIP-seq peaks. E Average plot (top) and heatmap view (bottom) of BCLAF1 and HA-p85β overlapping ChIP-seq peaks within TSS ± 3 kb regions. F De novo motif enrichment on BCLAF1 and HA-p85β overlapping ChIP-seq peaks using MEME and TOMTOM. Shown are matches ranked top 3 by statistical significance. P-values were obtained by two-sided likelihood ratio test. G DOV13 cells stably expressing vector or PIK3R2 (R2-OX) were mock-transfected or transfected with BCLAF1 siRNA for 72 hr prior to RNA-seq. The heatmaps show log2-transformed fold changes of p85β-induced differentially expressed genes (DEGs) mediated by BCLAF1, which were defined when the changes observed in R2-OX were reversed upon BCLAF1 depletion (R2-OX+BCLAF1si). H Overlap between genes associated with p85β and BCLAF1 overlapping ChIP-seq peaks and p85β-induced DEGs mediated by BCLAF1. I Gene Ontology (GO) classification of the potential p85β and BCLAF1 co-regulated genes (n = 102). Y-axis represents GO biological process terms and X-axis represents the gene ratio (the number of DEGs against the number of genes associated with the GO term). Classified processes with gene ratio>0.1 are shown. J mRNA levels of CCND1, ADAMTS1 and ALCAM from RNA-seq data. Data represent mean ± SD. P-values were obtained using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. These ChIP-seq and RNA-seq data were generated from biological triplicates. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To identify high-confidence target genes that are co-regulated by p85β and BCLAF1, we linked the overlapping peaks to differentially expressed genes by integrating the cistrome and transcriptome data. We performed RNA-seq with p85β-overexpressing DOV13 cells with or without silencing BCLAF1. Genes with expression changes induced by p85β overexpression (fold change < 0.5 or >1.5; P < 0.05) but were abolished upon BCLAF1 knockdown (P < 0.05) are likely p85β-regulated genes through BCLAF1. p85β overexpression led to 2733 DEGs, of which 363 (13.3%) were abolished after BCLAF1 knockdown (Fig. 6G; Supplementary Data 2). Among the 725 genes that were bound by both p85β and BCLAF1 according to ChIP-seq analysis, RNA-seq data were available for 576 genes. Importantly, 102 out of the 363 DEGs (28%) intersected with these 576 genes that were co-bound by p85β and BCLAF1 (Fig. 6H; Supplementary Data 3). These 102 DEGs in the intersection likely represent the direct transcriptional responses that are cooperatively driven by p85β and BCLAF1. We then aimed to understand the potential biological impacts of these co-regulated genes. Gene ontology analysis was performed to classify the 102 DEGs into biological processes. Among the top-level categories are cell proliferation and cell migration (Fig. 6I), which are consistent with the phenotypes displayed by p85β- and BCLAF1-expressing cells. Representative DEGs belonging to these two biological processes are CCND1 (cyclin D1 which promotes cell cycle progression34), ADAMTS1 (a metalloprotease that promotes invasion, migration and epithelial-mesenchymal transition35,36) and ALCAM (a cell adhesion molecule which promotes metastasis of cancers including that of ovary37,38) (Fig. 6J).

p85β and BCLAF1 localize to putative ZNF263 recognition motif

We next investigated the mechanism underlying the cooperative transcriptional regulation by p85β and BCLAF1. As shown in IP-MS data (Fig. 5A), TRIM28 was identified as a binding partner of p85β. TRIM28 is a scaffold protein that physically assembles transcription factors and co-regulators for gene regulation39,40. Intriguingly, a reported TRIM28-bound transcription factor is ZNF263, which is a Küppel associated box (KRAB) zinc finger protein that binds to TRIM28 through its KRAB domain40,41. Recognition motif of ZNF263 was enriched in p85β and BCLAF1 overlapping ChIP-seq peaks (Fig. 6F), including those located at the BCLAF1 loci (Fig. 7A). Therefore, we hypothesized that TRIM28 connects p85β and BCLAF1 with other regulatory proteins or transcription factors such as ZNF263. To test this hypothesis, we first examined the binding between TRIM28, p85β, BCLAF1 and ZNF263. Consistent with IP-MS, we were able to detect interaction between p85β and TRIM28 in IP experiments using anti-p85β antibody or reciprocally using anti-TRIM28 antibody (Supplementary Fig. 9A, B). Strikingly, TRIM28 could also bind to BCLAF1. IP after subcellular fractionation showed that the binding of TRIM28 with p85β or BCLAF1 or ZNF263 occurred mostly in the nucleus (Fig. 7B). Reciprocal IP using an anti-p85β antibody or anti-ZNF263 antibody further confirmed the interaction (Fig. 7B). Remarkably, we found that the binding of BCLAF1 with TRIM28 and ZNF263 was more prominent in p85β-overexpressing cells (Fig. 7C), suggesting that p85β enhances the complex formation. To complement our findings from IP, we utilized proximity ligation assay (PLA) to detect the protein interactions in situ. Consistently, the interaction between BCLAF1, TRIM28 and ZNF263 in the nucleus was enhanced upon p85β expression (Fig. 7D; Supplementary Fig. 9C). Furthermore, our data showed that the protein levels of ZNF263 and TRIM28 remained unchanged under the conditions of PIK3R2 overexpression or USP7 knockdown (Supplementary Fig. 6).

A A schematic of the BCLAF1 gene showing the putative ZNF263 recognition motif within locus 1, locus 2 and promoter region. The mutated nucleotides within the motif in the mutant BCLAF1 promoter reporter are highlighted in red. B Cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts of OVCAR8 cells were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-p85β antibody, anti-ZNF263 antibody or anti-TRIM28 antibody. IP with IgG was control and input represents total cell lysate. C Lysates of SKOV3 stably expressing vector or PIK3R2 (R2-OX) were subjected to IP with anti-BCLAF1 antibody. BCLAF1 protein levels were normalized prior to IP by using proportional amounts of lysates. The numbers below the blots are densitometry values relative to vector control. The bar graphs display the mean relative densitometry values from three independent experiments. D SKOV3 cells were subjected to proximity ligation assay with anti-ZNF263 and anti-BCLAF1 antibodies. The individual antibody alone served as negative control. The number of signals per nucleus of 200 cells from three independent experiments is presented as mean ± SD. Scale bars, 9 μm. E, F Cross-linked chromatin from DOV13 cells stably expressing PIK3R2 was immunoprecipitated with (E) anti-TRIM28 antibody or (F) anti-ZNF263 antibody or rabbit IgG. DNA fragments were amplified with primers for BCLAF1 promoter. G–I re-ChIP was performed with the indicated sequence of antibodies, with the first antibody against (G) BCLAF1, (H) ZNF263 or (I) HA. Normal rabbit IgG in second ChIP served as control. J DOV13 or SKOV3 cells were transfected with human WT (pGL3-BCLAF1-luc) or mutant (pGL3-BCLAF1-mut-luc) BCLAF1 promoter luciferase reporter or pGL3-Basic plasmid for 48 h. K ChIP-PCR for ZNF263 at BCLAF1 promoter in SKOV3 cells transfected with PIK3R2 siRNA for 72 h. The blots in (B, C) are representative of three independent experiments. Each individual data point in (E–K) represents the average of triplicates from one independent experiment; therefore, the data shown (mean ± SD) are from three independent experiments. P-values were obtained using two-tailed t-test (C–I) or two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test (J, K). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We reasoned that TRIM28 and ZNF263 bind to the BCLAF1 genomic loci where p85β and BCLAF1 co-occupy. Using anti-TRIM28 or anti-ZNF263 antibodies, ChIP-PCR revealed enrichment of TRIM28 and ZNF263 at the three BCLAF1 loci (Fig. 7E, F; Supplementary Fig. 10A, B). To investigate whether ZNF263, TRIM28, BCLAF1 and p85β bind to these loci as a complex, we performed re-ChIP experiments in which ZNF263- or BCLAF1-bound chromatin was re-immunoprecipitated with antibodies against one of the other three proteins. The re-ChIP analysis showed enrichment of all BCLAF1 loci, suggesting co-occupancy at these loci (Fig. 7G, H; Supplementary Fig. 10C, D). In addition, re-ChIP assay using anti-HA antibody and anti-TRIM28 antibody demonstrated that the loci were co-bound by p85β and TRIM28 (Fig. 7I; Supplementary Fig. 10E). We generated a mutant BCLAF1 promoter in which the putative ZNF263 binding motif was mutated (Fig. 7A). The luciferase activity of the mutant was significantly lower compared to that of the WT promoter (Supplementary Fig. 10F). Importantly, p85β failed to induce the promoter activity of the mutant (Fig. 7J). These data suggested that the motif is functional. To assess the role of p85β as a cofactor, we examined the contribution of p85β to ZNF263 occupancy at these loci. Remarkably, silencing p85β resulted in a reduction of ZNF263 binding to the BCLAF1 loci, whereas p85β overexpression enhanced the binding (Fig. 7K; Supplementary Fig. 11A, B). Similar effects on TRIM28 binding to the BCLAF1 locus could also be observed in these p85β-depleted or overexpressing cells (Supplementary Fig. 11C, D). Nuclear protein level of ZNF263 or TRIM28 was unchanged (Supplementary Fig. 11E). Therefore, the altered binding was not due to changes in protein abundance.

We confirmed that TRIM28 and ZNF263 are involved in p85β-induced transcription of BCLAF1 and oncogenicity. TRIM28 or ZNF263 siRNA reduced BCLAF1 promoter activity and BCLAF1 protein levels in parental ovarian cancer cells (Supplementary Fig. 12A–D). Concordant with these results, knockdown of TRIM28 or ZNF263 abrogated p85β-induced BCLAF1 mRNA and protein expression (Fig. 8A–D). Additionally, a combination of BCLAF1 siRNA with TRIM28 or ZNF263 siRNA caused an additive inhibition effect on BCLAF1 promoter activity, suggesting that TRIM28 and ZNF263 contribute to the autoregulation of BCLAF1 (Fig. 8E, F). Moreover, combined knockdown of TRIM28 and PIK3R2 led to a stronger reduction in BCLAF1 promoter activity and protein level than single knockdown (Supplementary Fig. 12E, F). In contrast, TRIM28 overexpression increased BCLAF1 protein level (Supplementary Fig. 12G) and reversed the reduction of BCLAF1 level upon PIK3R2 knockdown (Supplementary Fig. 12H). Lastly, to establish a functional role of ZNF263 in oncogenesis, multiple cancer phenotype assays were performed. Knockdown of ZNF263 decreased cell viability, colony formation, migration and invasion of parental or p85β-overexpressing cells (Fig. 8G–J). Taken together, these data suggest that BCLAF1 is autoregulated through cooperative activation by p85β, TRIM28 and ZNF263.

A–D DOV13 stable cells expressing vector or PIK3R2 (R2-OX) were transfected with (A, B) TRIM28 siRNA or (C, D) ZNF263 siRNA for 72 h, followed by (A, C) real-time PCR and (B, D) western blotting with ERK2 as loading control. OVCAR8 and SKOV3 cells were transfected with (E) BCLAF1 siRNA or TRIM28 siRNA alone or in combination or (F) BCLAF1 siRNA or ZNF263 siRNA alone or in combination for 48 hr prior to co-transfection of Renilla luciferase plasmid and human BCLAF1 promoter reporter or pGL3-Basic plasmid for another 48 h. G–J DOV13 stable cells expressing vector or PIK3R2 (R2-OX) were transfected with ZNF263 siRNA for 72 h, followed by (G) cell viability assay, (H) colony formation assay, or transwell assay for (I) cell migration or (J) cell invasion capabilities. Scale bar, 100 μm. Data (mean ± SD) in (A, C, G, I, J) and images in (B, D, H) are representative of three independent experiments. The bar graph in (H) shows the mean colony number ± SD from three independent experiments. The bar graph in (B) displays the mean relative densitometry values from three independent experiments. The numbers below the blots in (B, D) are densitometry values of the representative blots. Each individual data point in (E, F) represents the average of triplicates from one independent experiment; therefore, the data shown (mean ± SD) are from three independent experiments. The numbers of cells on the transwell membrane were counted in 5 random fields and data represent mean ± SD (I, J). P-values were calculated using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test (A–C, G–J) or one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test (E, F). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Co-activation of CCDC85B by p85β, BCLAF1, TRIM28 and ZNF263

CCDC85B was selected as another proof-of-concept gene to investigate the potential cooperativity of p85β, BCLAF1, TRIM28 and ZNF263 in transcription regulation. In RNA-seq and subsequent real-time PCR validation, CCDC85B mRNA expression was induced by p85β and the induction was abrogated upon BCLAF1 knockdown (Fig. 9A). ChIP-seq data further demonstrated that the CCDC85B gene locus bound by p85β and BCLAF1 contains a putative ZNF263 recognition motif (Fig. 9B). ChIP-PCR confirmed the binding of p85β, BCLAF1, TRIM28 or ZNF263 to the CCDC85B locus (Supplementary Fig. 13A). BCLAF1 mediates the binding of p85β to CCDC85B because p85β occupancy was substantially reduced upon BCLAF1 knockdown (Supplementary Fig. 13B). Additionally, the results from re-ChIP assays supported the co-occupancy of BCLAF1, ZNF263, p85β and TRIM28 on CCDC85B (Fig. 9C–E). Notably, when PIK3R2 was silenced, there was a reduction in ZNF263 occupancy at the CCDC85B locus (Fig. 9F). Knockdown of TRIM28 or ZNF263 also reduced CCDC85B mRNA levels (Fig. 9G, H). CCDC85B has been reported to promote cell proliferation and invasion in non-small cell lung cancer42. Concordantly, we observed a decrease in cell migration and invasion upon depletion of CCDC85B in both parental and p85β-overexpressing cells (Fig. 9I–K; Supplementary Fig. 13C–E).

A DOV13 stable cells expressing vector or PIK3R2 (R2-OX) were transfected with BCLAF1 siRNA for 72 h, followed by real-time PCR. B A schematic of the CCDC85B gene showing the locations of putative ZNF263 recognition motif. C–E re-ChIP experiments were performed with the indicated sequence of antibodies. The first ChIP was performed using antibody against (C) BCLAF1 or (D) ZNF263 or (E) HA (p85β). Normal rabbit IgG in second ChIP served as control. F ChIP-PCR analysis of chromatin enrichment of ZNF263 at CCDC85B locus in SKOV3 cells transfected with PIK3R2 siRNA for 72 h. G, H DOV13 stable cells expressing vector or PIK3R2 (R2-OX) were transfected with (G) TRIM28 siRNA or (H) ZNF263 siRNA for 72 h, followed by real-time PCR. I–K DOV13 stable cells expressing vector or PIK3R2 (R2-OX) were transfected with CCDC85B siRNA for 72 h, followed by (I) western blotting for the knockdown efficiency of CCDC85B with ERK2 as loading control, or (J) cell migration assay, or (K) cell invasion assay. Scale bar, 100 μm. Data and images in (A, G–K) are representative of three independent experiments with the bar graphs showing mean ± SD. Each individual data point in (C–F) represents the average of triplicates from one independent experiment; therefore, the data shown (mean ± SD) are from three independent experiments. The numbers below the western blots are densitometry values normalized to the loading control (I). The numbers of cells on the transwell membrane were counted in 5 random fields and data represent mean ± SD (J, K). P-values were calculated using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test (A, F–H, J, K) or two-tailed t-test (C–E). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Discussion

It is known that transcription factors often bind to gene regulatory regions in a cooperative manner to control gene expression43,44. The cooperativity may necessitate physical interactions between the transcription factors, which can be facilitated by cofactors44,45,46. This study defines a function of nuclear p85β in transcription regulation, potentially acting as a transcription cofactor and regulating cancer-related genes involved in cell proliferation, migration and invasion. p85β facilitates protein interactions among BCLAF1, TRIM28 and ZNF263 as well as promotes ZNF263/TRIM28 binding to gene loci. Important future investigations include (i) a comprehensive characterization of the protein interactions, and (ii) the impacts of these interactions on the binding repertoire of the transcription factors. Of note, this functional role of p85β in gene transcription control is unlikely dependent of the p110 subunits. Knockdown of the four p110 isoforms had no effect on p85β-induced regulation of BCLAF1 nor the nuclear translocation of p85β. Similarly, p85β has been shown to translocate into the nucleus after disassociating from p110α E545K to regulate protein stability in p110α-independent manner30. One study has demonstrated that a motif in p85β predicted to be a nuclear export signal regulates p85β nuclear export7. Investigating the export mechanism driven by this motif, such as binding analysis of the motif to exportin, would be an interesting area to pursue. Moreover, whether the cytoplasmic-to-nuclear ratio of p85β determines signaling outcomes warrants examination.

The auto-regulation of BCLAF1 generates a positive feedback loop that echoes the oncogenic role of BCLAF1 in ovarian cancer cells. Known regulatory mechanisms of BCLAF1 are mostly at the transcriptional level. NF-κB bound to its cognate DNA sequence within BCLAF1 promoter thereby activating BCLAF1 transcription15, whereas BCLAF1 transcription was inhibited by Sirt1 which caused H3K56 deacetylation at BCLAF1 promoter47. Here we identified TRIM28 and ZNF263 as two nuclear proteins that contribute to BCLAF1 autoregulation. The scaffold protein TRIM28, which is also named KRAB-associated protein-1, interacts with the KRAB domain which can be found in the majority of the C2H2 ZNF transcription factors39. TRIM28 itself does not bind DNA and has no sequence specificity. Through interacting with ZNFs which recognize consensus motifs, TRIM28 has been shown to repress or activate gene transcription39,48. A relatively well-characterized model to explain the transcriptional repression ability of TRIM28 is its binding with histone-modifying proteins that consequently triggers heterochromatinization and gene repression49. However, the mechanism associated with activating transcriptional regulation by TRIM28 is not known. Perhaps the interactome of TRIM28 such as the bound ZNF can determine the transcriptional outcomes of the DNA binding and the directionality of regulation. There are hundreds of ZNF family members and some of them have been reported to activate gene transcription48,50. Previous ChIP-seq and RNA-seq analyses have demonstrated both activating and repressive effects of ZNF263 on the transcription of gene targets40. ZNF263 binding sites are primarily regions within ±2 kb of TSS40. This binding site distribution appears to be similar with that of p85β and BCLAF1. Study on the functional role of ZNF263 in cancer has been very limited. It has been shown in glioblastoma that high ZNF263 levels correlated with poor patient prognosis and that ZNF263 bound with TRIM28 and chromatin modifiers to cause epigenetic gene silencing41. In hepatocellular carcinoma, knockdown of ZNF263 expression inhibited cell viability and increased apoptosis51.

The functional role of each protein of the p85β/BCLAF1/TRIM28/ZNF263 complex in transcription regulation remains to be elucidated. We found that the enrichment of p85β at gene loci is, at least in part, mediated by BCLAF1. Phosphorylation sites of BCLAF1 were identified in our proteomic profiling as well as in published studies52,53,54,55. A few phosphorylation sites detected in our assay have been previously reported. For instance, Ser531 has been identified as a downstream phosphorylation site of GSK-3β52. Additionally, while the phosphorylation of Ser512 was inhibited by the anti-carcinogenic agent genistein, phosphorylation of Ser658 was induced in cases of heart failure53,54. However, the functional significance of BCLAF1 phosphorylation remains poorly understood. The only published study characterizing BCLAF1 phosphorylation demonstrated that BCLAF1 Ser290 facilitated DNA damage repair and mediated the oncogenicity of BCLAF1 in gastric cancer55. Functional investigation of the different BCLAF1 phosphorylation sites may provide insights into their roles in transcription regulation and its collaboration with other transcription factors. The genomic sequences that BCLAF1 known to bind to are diverse. BCLAF1 can directly bind IFN-stimulated response elements (ISRE) consensus sequence (AGTTTCACTTTCC)17. Alternatively, BCLAF1 can be recruited to “non-canonical motifs” through binding with other transcription factors. This type of interaction between transcription factors, term as tethered binding, is highly frequent43,56. In this regard, BCLAF1 could be recruited to C/EBPβ consensus motif and ETS binding sequence by C/EBPβ and ETS-family transcription factor SPIC, respectively14,15. BCLAF1 also bound to gene promoters through tethering to the NF-κB subunit p5018. The binding of BCLAF1 to these transcription factors may mediate or even modify the regulatory activities of these transcription factors. For example, BCLAF1 is required for SPIC-mediated transcriptional changes14. Silencing BCLAF1 abrogated 55% of the expression changes induced by SPIC14. On the other hand, p50, which is thought to act intrinsically as a transcriptional repressor, acquired the ability to activate gene transcription upon binding to BCLAF118. Given our findings of an enriched putative ZNF263 consensus sequence in the p85β/BCLAF1 co-bound regions and subsequent investigations, one would reasonably speculate that the proteins are recruited to the ZNF263 binding sites. It is noteworthy that other than ZNF263, several putative transcription factor binding sites were significantly enriched in the p85β/BCLAF1 overlapping ChIP-seq peaks. Therefore, p85β and BCLAF1 likely bind to other nuclear proteins and thereby other sequence motifs. Further, given the fact that p85β and BCLAF1 ChIP-seq peaks only partially overlapped, nuclear p85β may interact with other transcription factors in the absence of BCLAF1.

To summarize, on the basis of our findings, we propose that nuclear p85β can serve as a cofactor that modulates protein-protein interactions in transcription complex. We showed that the transcription factor BCLAF1 is one of the effectors of nuclear p85β. This conceptual contribution paves the way for further exploration of the mechanistic actions of p85β in the nucleus.

Methods

Cell lines

Human ovarian cancer cell lines OVCAR8, OVCAR4 and DOV13 were obtained from the National Cancer Institute (Bethesda, MD). SKOV3 and OVCAR3 cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). The cell lines were cultured in RPMI-1640 media (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA), supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (Gibco), 100 units/mL penicillin and 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin. They were authenticated by STR analysis. Immortalized MEFs (WT or p85α−/− p55α−/− p50α−/− p85β−/−) were kind gifts from Dr. Lewis C. Cantley27 and were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium with 15% FBS (Gibco). All cell lines were grown at 37 °C with 5% CO2, and validated to be free of mycoplasma contamination. Stable cell lines were established by lentivirus transduction followed by blasticidin or puromycin selection.

siRNA and plasmids

ON-TARGETplus siRNA targeting human PIK3R2, BCLAF1, PIK3R1, PIK3CA, PIK3CB, PIK3CD, PIK3CG, AXL and non-specific siRNA were obtained from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO). siRNA against human TRIM28, CCDC85B, ZNF263, USP7, BCLAF1 3’ UTR were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coraville, IA). siRNA transfection was performed using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Sequence information of siRNA was shown in Supplementary Table 1. Human BCLAF1 promoter (2199 bp) was cloned into pGL3 luciferase reporter plasmid. Mutant reporter plasmid with the conserved residues in the ZNF263 binding motif mutated was prepared using site-directed mutagenesis. The mutated sequence does not correspond to any known transcription factor binding motif. N-terminally HA-tagged PIK3R2 was subcloned into pLenti6/V5-DEST™ Gateway™ Vector (Thermo Fisher Scientific). To create the NES-p85β mutant, NES sequence (LALKLAGLDI) was inserted between the HA tag and the PIK3R2 opening reading frame. Expression plasmid of human BCLAF1 in pLVX-EGFP-C1 lentiviral vector was purchased from Youbio (Hunan, China). pcDNA6.2-GFP-TRIM28 was a gift from Kyle Miller (Addgene plasmid # 65397)57. The constructs were validated by DNA sequencing. DOV13 and SKOV3 cells with stable PIK3R2 overexpression or vector control were conducted by infection of lentivirus with pLenti6-PIK3R2 or empty pLenti6 vector followed by blasticidin selection. Likewise, DOV13 and OVCAR8 cells stably expressing BCLAF1 and the corresponding vector control were established by lentiviral transduction prior to puromycin selection.

Cell viability assay

Cells were seeded at density of 1000 cells/well in triplicate in 96-well plates. After 5 days of culture, cell viability was detected by incubating cells with 10% volume of resazurin (0.2 mg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO) for 3 h at 37 °C prior to measurement of absorbance at 570/600 nm (Excitation/Emission). The absorbance readings were subtracted with background reading (culture media only without cells).

Colony formation assay

Cells were seeded at a density of 1000 cells per well in 6-well plates in triplicate, with the media changed every 3 days. After 10 days, cell colonies were stained with 0.5% crystal violet dissolved in 20% ethanol and imaged. Colonies that contained ≥50 cells were counted.

Cell migration and invasion assays

Cells suspended in serum-free medium and were seeded into 1 mg/mL Matrigel-precoated (Corning Life Sciences, Corning, NY) (invasion assay) or uncoated (migration assay) 8-µm inserts (Millipore, Burlington, MA). Inserts were placed to individual wells of 24-well plates with 600 µL 10% FBS-containing culture medium in the lower chambers. Cells were then allowed to migrate or invade for 16 h before ice-cold methanol fixation and crystal violet (0.1%) staining. Five fields of each insert were randomly captured under light microscope and the number of invaded or migrated cells was counted.

Cell cycle analysis

Cells (2 × 105) were plated in 60 mm dishes. The next day, they were synchronized via two steps of 2 mM thymidine treatment (Sigma-Aldrich) for 16 h, with 8 h fresh medium release in between. After that, cells were released in fresh medium and collected 6 hrs later. Cells were harvested by trypsinization, washed with ice-cold PBS twice and fixed with ice-cold 70% ethanol overnight. To measure DNA content, the fixed cells were treated with RNase A solution (50 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min at 37 °C and then subjected to propidium iodide staining (20 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich). The samples were analyzed by flow cytometry using BD Accuri™ C6 Plus. At least 10,000 cells were assessed per measurement. Cell cycle analysis was performed by FlowJo software (10.8.1).

Immunofluorescence staining

Ovarian cancer cells were seeded onto sterile coverslips in 24-well plate. After attachment, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100. After blocking with 3% BSA for 1 h, cells were incubated with primary antibody overnight (Supplementary Table 2). Cells were washed with PBS for 3 times and then incubated with secondary antibody for another 1 h. Mounting medium with DAPI was added to the coverslip, prior to image capture using Carl Zeiss LSM-700 (Oberkochen, Germany).

Western blotting and immunoprecipitation

Whole cell protein extracts were prepared using RIPA lysis buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate) containing dual protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Subcellular fractionation was performed using Minute™ Cytoplasmic and Nuclear Extraction Kit (Invent Biotechnologies, Plymouth, MN) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, cells were first harvested in cytoplasmic extraction buffer. After centrifugation, cytosolic fraction in the supernatant was collected whereas the pellet was dissolved in nuclear extraction buffer. Protein concentration was determined by BCA Protein Assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Samples with equal amounts of protein were prepared with the addition of 6 × SDS loading buffer and denatured. After SDS-PAGE, membranes were probed with primary antibodies (Supplementary Table 2) overnight at 4 °C, HRP-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (1:5000)(Amersham, Marlborough, MA) for 2 h at room temperature, and detected with Western ECL kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). ERK2 was detected as loading control. For immunoprecipitation, cells were lysed in buffer containing 50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, 5 mM EDTA, protease and phosphatase inhibitors. After protein extraction, samples were precleared with protein A/G agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX) at ratio of 20 µL beads per 1 mL cell lysate. The lysates were then incubated with antibody overnight at 4 °C and co-incubated with Protein A/G beads for another 4 h. The protein A/G beads containing protein-antibody immunocomplexes were washed with lysis buffer 5 times, eluted by 2×Laemmli sample buffer (62.5 mM Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 25% glycerol, 2% SDS, 0.01% bromophenol blue and 5% β-mercaptoethanol), and subjected to western blotting. The information of all antibodies used is shown in Supplementary Table 2. Densitometry values were obtained using ImageJ (version1.53k). Numbers below the blots in the figures are relative densitometry values of the representative blots shown. Densitometry data with statistical analysis of the triplicate blots are provided in Supplementary Data 4.

Immunohistochemistry

Human ovarian cancer tissue array was purchased from Pantomics (catalog number: OVC1021)(Richmond, CA). The slides were deparaffinized and rehydrated in graded ethanol prior to antigen retrieval using citrate buffer (pH 6.0). The slides were then incubated with 3% H2O2 Block solution for 5 min to deactivate the endogenous peroxidase prior to the blocking with 10% goat serum. Incubation with primary antibody was performed at 4 °C overnight, followed by biotin-conjugated secondary antibody (Dako, Carpinteria, CA) for 1 h at room temperature and detection by DAB (Amresco, Solon, OH). Protein levels of each case were represented by histoscores. Nuclear levels of p85β or BCLAF1 were represented by histoscore (0–16), which was calculated by multiplying the score of percentage of positive cells (0=negative, 1 = 1-25%, 2 = 26–50%, and 3 = 51–75% and 4 ≥ 76%) and the intensity score (0=negative, 1=weak, 2=moderate, and 3=intense and 4=very intense). Cytoplasmic levels of p85β protein (which is present in all stained cells) were represented by intensity score (0-4).

Realtime PCR

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent according to the instruction (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The concentration of RNA was determined using NanoDrop™ 2000 Spectrophotometers (Thermo Fisher Scientific). One microgram of total RNA was reverse transcribed using HiScript II 1st Stand cDNA Synthesis Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Vazyme Biotech, Nanjing, China), followed by cDNA amplification using AceQ qPCR SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Vazyme). Primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 3. The mean value of threshold cycle (Ct) of target genes was normalized to the housekeeping gene GAPDH (ΔCt), and the relative fold-change of mRNA expression was calculated by the 2-ΔΔCt method. The assays were performed in triplicate and repeated in three independent experiments.

Luciferase reporter assay

Cells were co-transfected with pGL3 basic luciferase vector (promoter-less control) or pGL3-BCLAF1 with Renilla luciferase plasmid (pRL-TK) using Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Some cells were transfected with siRNA for 48 h before promoter construct transfection. After 48 h, the activities of firefly and Renilla luciferase were measured by Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System according to the manufacturer’s instruction (Promega, Madison, WI). The firefly luciferase reading in each transfection was adjusted by normalizing it to the Renilla luciferase reading to account for variations in transfection efficiency. The numerical value was then further normalized relative to that of pGL3-Basic. Assays were performed in triplicate and repeated in three independent experiments.

Mass spectrometry (MS) analysis

The total proteome and phosphoproteome data of PIK3R2-depleted SKOV3 cells were previously published by our group (ProteomeXchange Consortium dataset identifier PXD018449). To prepare samples for immunoprecipitation-MS, protein lysates of OVCAR8 cells overexpressing p85β were subjected to immunoprecipitation using anti-p85β antibody to pull down p85β binding proteins or IgG as control (n = 1 for each condition). The eluted proteins were loaded in 8% SDS-PAGE gel and stained with coomassie blue. Subsequent protein sample preparation, liquid chromatography tandem MS (LC-MS/MS) and data analysis were performed at the Proteomics and Metabolomics Core, Centre for PanorOmic Sciences, University of Hong Kong. Protein was reduced by 10 mM TCEP (Thermo Fisher Scientific), alkylated by 55 mM 2-chloroacetamide (Sigma) and digested by 1 ng/μL trypsin overnight at 37 °C. After digestion, peptides were extracted from the gel pieces with 50% acetonitrile (ACN; J.T. Baker)/5% formic acid (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 100% ACN and were desalted using C18 StageTips. The samples were then analyzed on a nanoelute UHPLC coupled to Bruker timsTOF pro mass spectrometer. Raw MS data files were processed using MaxQuant 1.6.1458, the Andromeda search engine59 and were searched against the Human UniProt FASTA database (Apr 2020; 74,824 entries). Proteins with at least one unique peptide detected in sample immunoprecipitated with anti-p85β antibody but were absent in sample immunoprecipitated with IgG control were considered as p85β-interacting proteins.

RNA-seq

Total RNA from empty vector-expressing or PIK3R2-overexpressing DOV13 cells treated with siRNAs or mock for 72 hr (3 biological replicates per condition) were extracted using TRIzol. Quality of the extracted RNA was assessed using gel electrophoresis and BioAnalyser 2100 (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) for RNA integrity. Poly(A)-seq library preparation using NEBNext® Ultra™ RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina® (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) and paired end 150 bp sequencing on Illumina Novaseq 6000 (Illumina, San Diego, CA) were performed by Novogene (Beijing, China). After filtering low-quality reads and adapter sequences, the trimmed reads were aligned to human reference genome GRCh38 using STAR aligner version 2.7.3a60. RNA-seq read counts were normalized using median of ratios method (MRN) provided by DESeq2 version 1.26.0 software package61. The normalized counts were then used for the identification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs; PIK3R2 overexpression Vs empty vector). The thresholds for DEGs were set as fold-change ≥ 1.5 or fold-change ≤ 0.5 at P < 0.01. PIK3R2-induced DEGs mediated by BCLAF1 were defined when the changes were reversed upon BCLAF1 depletion (PIK3R2 overexpression + BCLAF1 siRNA Vs PIK3R2 overexpression) at P < 0.05. Gene ontology (GO) analysis of the p85β and BCLAF1 co-regulated genes was performed using the groupGO function in the clusterProfiler package62, which is a gene classification method to categorize the genes based on GO distribution (parameters we adopted: biological process, level 3).

ChIP-seq

Cells (5 × 106; three biological replicates/immunoprecipitation target) in culture medium were crosslinked with formaldehyde 1% for 10 min at room temperature and quenched with 125 mM glycine for 5 min. Fixed cells were resuspended in Farnham Lysis Buffer (5 mM PIPES pH 8.0, 85 mM KCl, 0.5% NP-40 with protease inhibitors). After centrifugation, nuclear pellet was resuspended in lysis buffer (1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS with protease inhibitors). Chromatin was sonicated at 4 °C using a Bioruptor Pico sonicator (Diagenode, Denville, NJ) for ten 1-min cycles (30 s ON/30 s OFF) to generate fragments of 100-300 bp in length (Supplementary Fig. 14A). The sheared chromatin diluted with dilution buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 0.01% SDS, 1.1% Triton X-100, 1.1 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl with protease inhibitor) was pre-cleared with magnetic protein G agarose beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 1 h with rotation at 4 °C. Pre-cleared supernatant was incubated with primary antibody or non-specific IgG and the magnetic beads overnight at 4 °C. Next, the beads were washed twice with low salt wash buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl with protease inhibitors), twice with LiCl wash buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 500 mM LiCl, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate with protease inhibitors), and twice with Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer pH 8.0 with protease inhibitors. Elution step was then performed by incubating the beads with elution buffer (1% SDS, 100 mM NaHCO3) for 15 min at 65 °C. The crosslinking was reversed by adding 100 mM NaCl with incubation at 65 °C overnight prior to RNase A (Sigma-Aldrich) and proteinase K (Thermo Fisher Scientific) treatment for another 1 h. ChIP-enriched DNA was purified using QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD). ChIP-seq library construction using NEBNext® Ultra™ II DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina® (New England Biolabs), library quality and quantity assessment by Qubit 2.0 fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and pair-end sequencing (PE150) on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform were performed by Novogene.

Quality control checks on raw sequencing data in FASTQ format was performed using FastQC (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/, version 0.11.9). Clean reads after trimming off adapter sequences and low-quality bases were mapped to human reference genome GRCh38 using BWA-MEM version 0.7.17 to generate bam files (default settings)63. Duplicated reads were marked with SAMBLASTER version 0.1.2664. SAMtools (Version 1.9)65 was used to remove reads with mapping quality less than 20. Peak detection was performed using MACS3 version 3.0.0b1 to identify regions of IP enrichment over input samples as the background66. A P-value of 0.0001 was used as threshold. Called peaks from the three biological replicates were merged for downstream analyses. Peaks were assigned to putative target genes using ChIPseeker version 1.30.367, which assigns each peak to the closest transcription start site (TSS). MEME 5.5.132 and Tomtom33 were used for motif discovery and comparison respectively.

ChIP-PCR

ChIP was performed using a commercially available kit (ChIP-IT Express Enzymatic Kit; Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, cells (1 × 107) were crosslinked with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature and quenched with 125 mM glycine for 5 min. The fixed cells were lysed for nuclei extraction. Chromatin was sheared enzymatically for 5 min. A portion of digested chromatin was subjected to crosslink reversal, proteinase K digestion and phenol-chloroform purification. Purified chromatin (1 μg) was analyzed on a 1.2% agarose gel (Supplementary Fig. 14B). Protein–chromatin complex was incubated with protein G-coated magnetic beads and anti-HA antibody, anti-BCLAF1 antibody, anti-ZNF263 antibody, or anti-TRIM28 antibody overnight at 4 °C. Rabbit IgG was used as negative control. The captured complexes were washed, and ChIP DNA was eluted from the beads with elution buffer provided in the kit prior to crosslink reversal at 65 °C for 2.5 h. ChIP DNA was subjected to proteinase K treatment at 37 °C for 1 h. Real-time PCR was performed with SYBR Green master mix on CFX Opus 96 Real-Time PCR System (Bio-Rad) using the primer sets listed in Supplementary Table 4. 1% of starting chromatin was used as input. ChIPs were normalized to input DNA.

Sequential ChIP (re-ChIP) was performed using Re-ChIP-IT magnetic chromatin re-immunoprecipitation kit (Active motif). Procedures were similar with the above except that eluted chromatin from the first ChIP was desalted over columns before incubation with protein G magnetic beads and the second antibody or IgG control. ChIP DNA eluted from the sequentially immunoprecipitated complexes was subjected to crosslink reversal and real-time PCR analysis. Assays were performed in triplicate and repeated in three independent experiments.

Proximity ligation assay (PLA)

The detection of interaction signals in PLA was carried out following the protocol provided by the Duolink PLA fluorescence kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Briefly, cells attached to cover slips were fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde, followed by permeabilization with 0.1% Triton X-100 and blocking. Subsequently, the cells were incubated overnight with a combination of two primary antibodies. As a negative control, one of the antibodies was replaced with IgG. Then, the cells were incubated with the PLA probes (PLUS and MINUS) for 1 h. The probe ligation was performed using a ligation-ligase solution containing two DNA nucleotides that form circular structures. PLA signals were amplified using an amplification-polymerase solution. Finally, the slides were mounted with a coverslip using a mounting medium with DAPI. Fluorescence signals were observed at 461 nm (DAPI) and 594 nm (Texas Red) using a PerkinElmer UltraVIEW VoX Spinning Disc Confocal Microscope. The microscope settings were kept constant for all image capture. The number of spots was counted using ImageJ (version1.53k) as described68. Briefly, auto-threshold (using the “Minimum” method) was applied to the 8-bit images and the spots were quantified (“Analyze Particles”) after global thresholding. The same quantification algorithm was applied to all images. The negative control samples showed no spot by ImageJ analysis and manual inspection. For each sample, the number of spots per cell was counted in at least 60 cells in each independent experiment. The assay was repeated three times.

Statistics and reproducibility

Experiments except omics profiling were performed three times independently. Results were analyzed using GraphPad Prism software (version 10.2.3) and data are displayed as the mean ± SD. Significance between two groups was determined by 2-sided Student’s t-test. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s post hoc test was used to determine statistical significance of differences among multiple groups. Linear correlation analysis was performed using Spearman’s correlation coefficient. P < 0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. No statistical method was used to predetermine sample size. No data were excluded from the analyses. The experiments were not randomized. The Investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The RNA-seq and ChIP-seq data have been deposited in NCBI’s GEO repository under accession numbers GSE266499 and GSE266856, respectively. The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE69 partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD052205. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Engelman, J. A., Luo, J. & Cantley, L. C. The evolution of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases as regulators of growth and metabolism. Nat. Rev. Genet. 7, 606–619 (2006).

Ito, Y., Hart, J. R., Ueno, L. & Vogt, P. K. Oncogenic activity of the regulatory subunit p85beta of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 16826–16829 (2014).

Luo, J. et al. Modulation of epithelial neoplasia and lymphoid hyperplasia in PTEN+/- mice by the p85 regulatory subunits of phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 10238–10243 (2005).

Cortes, I. et al. p85beta phosphoinositide 3-kinase subunit regulates tumor progression. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 11318–11323 (2012).

Cariaga-Martinez, A. E. et al. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase p85beta regulates invadopodium formation. Biol. Open 3, 924–936 (2014).

Rao, L. et al. p85beta regulates autophagic degradation of AXL to activate oncogenic signaling. Nat. Commun. 11, 2291 (2020).

Kumar, A. et al. Nuclear but not cytosolic phosphoinositide 3-kinase beta has an essential function in cell survival. Mol. Cell Biol. 31, 2122–2133 (2011).

Park, S. W. et al. The regulatory subunits of PI3K, p85alpha and p85beta, interact with XBP-1 and increase its nuclear translocation. Nat. Med. 16, 429–437 (2010).

Winnay, J. N., Boucher, J., Mori, M. A., Ueki, K. & Kahn, C. R. A regulatory subunit of phosphoinositide 3-kinase increases the nuclear accumulation of X-box-binding protein-1 to modulate the unfolded protein response. Nat. Med. 16, 438–445 (2010).

Madhusudhan, T. et al. Defective podocyte insulin signalling through p85-XBP1 promotes ATF6-dependent maladaptive ER-stress response in diabetic nephropathy. Nat. Commun. 6, 6496 (2015).

Chiu, Y. H., Lee, J. Y. & Cantley, L. C. BRD7, a tumor suppressor, interacts with p85alpha and regulates PI3K activity. Mol. Cell 54, 193–202 (2014).

Park, S. W. et al. BRD7 regulates XBP1s’ activity and glucose homeostasis through its interaction with the regulatory subunits of PI3K. Cell Metab. 20, 73–84 (2014).

Kasof, G. M., Goyal, L. & White, E. Btf, a novel death-promoting transcriptional repressor that interacts with Bcl-2-related proteins. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 4390–4404 (1999).

Soodgupta, D. et al. RAG-mediated DNA breaks attenuate PU.1 Activity in early B cells through activation of a SPIC-BCLAF1 complex. Cell Rep. 29, 829–843.e825 (2019).

Shao, A. W. et al. Bclaf1 is an important NF-kappaB signaling transducer and C/EBPbeta regulator in DNA damage-induced senescence. Cell Death Differ. 23, 865–875 (2016).

Wen, Y. et al. Bclaf1 promotes angiogenesis by regulating HIF-1alpha transcription in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene 38, 1845–1859 (2019).

Qin, C. et al. Bclaf1 critically regulates the type I interferon response and is degraded by alphaherpesvirus US3. PLoS Pathog. 15, e1007559 (2019).

Zhang, R. et al. Bclaf1 regulates c-FLIP expression and protects cells from TNF-induced apoptosis and tissue injury. EMBO Rep. 23, e52702 (2022).

Liu, H., Lu, Z. G., Miki, Y. & Yoshida, K. Protein kinase C delta induces transcription of the TP53 tumor suppressor gene by controlling death-promoting factor Btf in the apoptotic response to DNA damage. Mol. Cell Biol. 27, 8480–8491 (2007).

Lee, Y. Y., Yu, Y. B., Gunawardena, H. P., Xie, L. & Chen, X. BCLAF1 is a radiation-induced H2AX-interacting partner involved in gammaH2AX-mediated regulation of apoptosis and DNA repair. Cell Death Dis. 3, e359 (2012).

Lamy, L. et al. Control of autophagic cell death by caspase-10 in multiple myeloma. Cancer Cell 23, 435–449 (2013).

Zhou, X. et al. BCLAF1 and its splicing regulator SRSF10 regulate the tumorigenic potential of colon cancer cells. Nat. Commun. 5, 4581 (2014).

Dell’Aversana, C. et al. miR-194-5p/BCLAF1 deregulation in AML tumorigenesis. Leukemia 31, 2315–2325 (2017).

Wen, W., Meinkoth, J. L., Tsien, R. Y. & Taylor, S. S. Identification of a signal for rapid export of proteins from the nucleus. Cell 82, 463–473 (1995).

Ueki, K., Algenstaedt, P., Mauvais-Jarvis, F. & Kahn, C. R. Positive and negative regulation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase-dependent signaling pathways by three different gene products of the p85alpha regulatory subunit. Mol. Cell Biol. 20, 8035–8046 (2000).

Mauvais-Jarvis, F. et al. Reduced expression of the murine p85alpha subunit of phosphoinositide 3-kinase improves insulin signaling and ameliorates diabetes. J. Clin. Investig. 109, 141–149 (2002).

Brachmann, S. M. et al. Role of phosphoinositide 3-kinase regulatory isoforms in development and actin rearrangement. Mol. Cell Biol. 25, 2593–2606 (2005).

Xie, Z. et al. Gene set knowledge discovery with enrichr. Curr. Protoc. 1, e90 (2021).