Abstract

The treatment selection for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma (rHCC) within Milan criteria after hepatectomy remains challenging. Here, we present HEROVision, a Vision Transformer-based model designed for personalized prognosis prediction and treatment optimization between thermal ablation (TA) and surgical resection (SR). HEROVision is trained on initial HCC cohorts (8492 images; 772 patients) and independently tested on rHCC cohorts (9163 images; 833 patients) from five centers. Propensity score matching (PSM) forms two groups of rHCC patients underwent TA and SR to fairly evaluate whether optimized treatment selection by HEROVision have clinical benefits. HEROVision significantly outperforms all six guideline staging systems in the external testing cohort, both in time-dependent concordance index and area under the curve (all P < 0.002). After PSM, 35.9% (23/64) and 6.6% (6/91) high-risk rHCC patients are identified, who could achieve improved prognosis by changing their treatments. HEROVision shows promise in optimizing individualized treatment between TA and SR for early-stage rHCC, complementing current clinical guidelines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) stands as the predominant primary hepatic malignancy, presently ranking as the sixth most prevalent type of cancer and third principal cause of cancer-related mortality globally1,2. According to the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging classification system, patients with very early (BCLC 0 stage) or early (BCLC A stage) HCC are recommended curative modalities, including local ablation, hepatic resection, and liver transplantation3. However, >60% of patients with early-stage HCC develop recurrent HCC (rHCC) within 5 years of initial curative hepatic resection or percutaneous ablation therapy4,5.

In real-world clinical practice, the treatment alternatives for rHCC after hepatic resection remain identical to the initial therapeutic choices. Thus, repeat hepatic resection (RHR) and thermal ablation (TA) are frequently employed in the management of rHCC owing to the shortage of available organs for transplantation, especially in China. Surgical resection (SR) is predominantly employed in patients with HCC exhibiting a favorable performance status, sufficient functional liver remnants, and the absence of vascular invasion6. Conversely, patients with diminished performance, progressing liver disease, restricted residual liver, and potential technical challenges arising from abdominal adhesions have been shown to benefit from TA, particularly through radiofrequency ablation (RFA) or microwave ablation5. There are currently no definitive classification systems or clinical practice guidelines advocating an individual preference for treatment options for these patients7,8,9,10. Several previous studies have compared the safety and long-term outcomes of RHR and RFA in patients with rHCC11,12,13,14. However, the findings of these studies have some disparities. Notably, a randomized clinical trial indicated that RHR may be associated with superior local disease control and long-term survival among patients with rHCC measuring greater than 3 cm15. To our knowledge, the optimal treatment regimens for rHCC remain undefined in both guidelines and literature compared to those established for initial HCC (iHCC).

Noninvasive imaging surveillance is warranted after curative-intent therapy, with both contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) being employed to detect rHCCs16. Multimodal imaging, owing to its specific advantages, plays a pivotal role in the detection of smaller and earlier lesions in rHCC. However, these methods do not assist physicians in recommending the most beneficial strategy for treating rHCC. Deep learning (DL), an emerging technology based on data-driven learning, has recently emerged as a promising strategy for guiding clinical decision-making17. The Vision Transformer (ViT) is a groundbreaking architecture, representing the first fully Transformer-based model adapted for image tasks. Networks that leverage the Transformer’s self-attention mechanism have demonstrated greater efficiency in training and inference, particularly for capturing long-range dependencies and relationships within images compared to convolutional neural networks (CNNs)18. Additionally, Transformers can significantly outperform CNNs in generalization on out-of-distribution samples19. Although DL analysis has shown promise as a technology for treatment selection in patients with primary HCC, currently, there are no reports facilitating the optimized selection of treatment between RHR and TA for patients with rHCC using multimodal imaging. The biggest challenge with this issue is the lack of sufficient rHCC patient data to train and validate a DL model. Previous studies demonstrated that the treatment prognosis of patients with early-stage iHCC closely resembled that of patients undergoing secondary treatment for early-stage rHCC (within Milan criteria after hepatectomy)2,5,15.

In this work, a DL model, trained on data from iHCC, achieves effective prognosis prediction in patients with rHCC. We develop a ViT-based strategy, named HEROVision (HCC optimizing treatments with Vision Transformer network), to assist clinical decision-making by learning prognosis-related features from CEUS and MRI. This approach aims to develop and validate a ViT-based model designed for optimizing individual treatment selection between RHR and TA for patients with early-stage rHCC in real-world scenarios.

Results

Patient characteristics

The clinico-radiological characteristics of the training, internal validation and external testing datasets are shown in Table 1. In the TA dataset, 1002 patients were enrolled, median age was 58 years (IQR, 51–65 years), and the median follow-up duration was 3.09 years (range, 1.98–4.61 years). In the SR dataset, 603 patients were enrolled, median age was 58 years (IQR, 50–66 years), and the median follow-up duration was 2.90 years (range, 1.79–4.01 years).

Development and validation of the HEROVision in iHCC dataset

We trained the HEROVision-TA and -SR models to predict the hazards of progression-free survival (PFS) using the 1stTA and 1stSR datasets, respectively (Fig. 1). These models combined a ViT network with key clinical factors described above to formulate a multimodal imaging-based PFS hazard model (Fig. 2). The selection of key clinical factors is presented Supplementary Note 8 and Supplementary Table 2. The corresponding nomograms based on HEROVision-TA and -SR are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2, which can be used to visualize the individual PFS risk.

a A real-world clinical decision-making scenario for rHCC. b Construction of HEROVision models for TA and SR using the 1stTA and 1stSR datasets, respectively. c Clinical application of HEROVision-TA and -SR models. Cross-stratifications were executed by employing HEROVision-TA and -SR models on CEUS and MRI from exchanged patient cohorts, respectively. Subsequently, individualized prediction of PFS was compared between the original and re-stratified patient subgroups for each of the 2ndTA and 2ndSR datasets. iHCC initial hepatocellular carcinoma, rHCC recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma, CEUS contrast-enhanced ultrasound, MRI magnetic resonance imaging, TA thermal ablation, RHR repeat hepatic resection, SR surgical resection, CAD computer-aided diagnosis, T2WI T2-weighted imaging, DWI diffusion-weighted imaging, PFS progression-free survival, HEROVision hepatocellular carcinoma optimizing treatments with Vision Transformer network.

Supplementary Figs. 3a, b and 4a, b show Harrell’s concordance index (C-index) and time-dependent area under the curve (AUC) at different points in the TA and SR datasets. The 2-year C-indexes for the training and internal validation cohorts of the HEROVision-TA model were 0.95 (95% confidence intervals [CI]: 0.93–0.97) and 0.87 (95% CI: 0.80–0.94), respectively. Correspondingly, the 2-year AUCs were 1.00 (95% CI: 0.99–1.00) and 0.90 (95% CI: 0.81–1.00), respectively (Supplementary Fig. 3c). Supplementary Fig. 4a–c show similar performances of HEROVision-SR. It achieved high levels of 2-year C-indexes, with values of 0.92 (95% CI: 0.90–0.95) and 0.83 (95% CI: 0.73–0.92) in the training and internal validation cohorts, respectively. It provided 2-year AUCs of 0.95 (95% CI: 0.93–0.98) and 0.92 (95% CI: 0.79–1.00) in these two cohorts.

As expected, the performance of the HEROVision model surpassed that of the clinical model, as evidenced by significantly higher C-indices and time-dependent AUCs in all training and internal validation cohorts for TA and SR (P = 5.320 × 10−21–0.003). Additional performance metrics of the 2-year PFS, including accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and F1 score, are shown in Supplementary Table 3.

Based on the optimum cutoff in the training cohort, patients were divided into low- and high-risk subgroups. In the training cohort, the 2-year PFS rates were 99.4% (1stTA dataset) and 98.0% (1stSR dataset) for the low-risk group, in contrast to 19.6% and 23.9% for the high-risk group (Fig. 3a, d). Similarly, in the internal validation cohort, the 2-year PFS rates were 95.5% and 96.4% in the low-risk group and 59.7% and 42.7% in the high-risk group (Fig. 3b, e).

a–c TA dataset in the training, internal validation, and external testing cohorts, respectively. d–f SR dataset across all three cohorts. The error bands (dashed lines) represent the 95% confidence intervals, and the P values were calculated using the two-sided Log-rank test. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. TA thermal ablation, SR surgical resection, PFS progression-free survival, HR hazard ratio.

HEROVision for individualized prognostic prediction in rHCC dataset

HEROVision was directly applied to 2ndTA and 2ndSR datasets from five centers for independent external tests. As expected, HEROVision models did not perform as well as they did on the training and internal validation cohorts (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4). However, the 2-year C-indexes of HEROVision-TA and -SR still reached 0.72 (95% CI: 0.69–0.76) and 0.71 (95% CI: 0.65–0.77) in the external testing cohorts, respectively. Corresponding 2-year AUCs were 0.78 (95% CI: 0.74–0.82) and 0.81 (95% CI: 0.75–0.88). All these values significantly surpassed those of the clinical models using the DeLong test (P = 2.186 × 10−7–6.377 × 10−4). All detailed quantitative measures are presented in Supplementary Table 3. Comparisons of C-index, time-dependent AUC, and 2-year AUC between HEROVision and clinical models in each center cohort are shown in Supplementary Figs. 5–7.

Furthermore, we confirmed a significantly different prognosis between high- and low-risk patients stratified by HEROVision in the external testing cohort for both TA and SR (Fig. 3c, f). The 2-year PFS rates for the low-risk group were 72.6% (2ndTA dataset) and 75.0% (2ndSR dataset), whereas those for the high-risk group were 40.8% and 29.9%, respectively. Hazard ratios of HEROVision-TA and HEROVision-SR were 2.88 (95% CI: 2.31–3.60; Log-rank test: P = 3.30 × 10−22) and 2.69 (95% CI: 1.77–4.08; Log-rank test: P = 1.72 × 10−6) between the low- and high-risk groups.

To assess the clinical benefit value, we used decision curve analysis to determine the model score interval that could potentially benefit patients based on the HEROVision model recommendations at 1, 2, and 3-years. In the external testing cohort, for the 2ndTA dataset, clinical net benefits were observed to be higher than zero at two years, when the threshold was set within the range of 0.29–0.68; For the 2ndSR dataset, clinical net benefits exceeded 0, when the threshold was set within the interval of 0.25–0.72. Supplementary Fig. 8 depicts the decision curves of all models for each interval.

Comparisons with major guideline methods

HEROVision consistently performed better than all six major staging systems proposed by different guidelines, whether for the training, internal validation, or external testing cohorts, and regardless of TA and SR, in terms of C-index values and time-dependent AUCs (Fig. 4a–d). In the external testing cohort, Table 2 shows that the 2-year C-index of HEROVision (0.72 for the 2ndTA and 0.71 for the 2ndSR datasets) was significantly higher than those of the six staging systems (0.51–0.58 for the 2ndTA and 0.53–0.57 for the 2ndSR datasets, P = 2.665 × 10−15–0.002); Moreover, 2-year AUCs also exhibited significant differences between HEROVision and the six staging systems (0.78 vs. 0.51–0.61 for the 2ndTA dataset, 0.81 vs. 0.55–0.61 for the 2ndSR dataset, P = 1.210 × 10−35–1.200 × 10−6).

For TA (a, b) and SR (c, d) datasets, the C-index values in the training, internal validation, and external testing cohorts (a, c), along with the time-dependent AUCs in all three cohorts (b, d), shows that HEROVision consistently outperformed all six major staging systems proposed by different guidelines for prognostic prediction. Furthermore, there were noticeable enhancements in 2-year C-index and AUC for the six staging systems, after they were supplemented with HEROVision for both 2ndTA (e, f) and 2ndSR (g, h) datasets. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. TA thermal ablation, SR surgical resection, C-index concordance index, AUC area under the curve, AJCC American Joint Committee on Cancer, BCLC Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer, CNLC China Liver Cancer, HKLC Hong Kong Liver Cancer, ITA.LI.CA Italian Liver Cancer, UICC Union for International Cancer Control.

Furthermore, the 2-year C-index and AUC of the six staging systems were significantly enhanced (all P values < 0.001), after incorporating HEROVision into the analysis for both 2ndTA and 2ndSR datasets (Fig. 4e–h and Supplementary Fig. 9). This revealed that HEROVision could improve the 2-year PFS prediction accuracy of major guideline methods for patients with rHCC in clinical practice.

Ablation studies

To understand the impact of training data size on the model’s performance, we examined the C-index and time-dependent AUC with different proportions of the TA and SR datasets, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 10. In the internal validation cohort, varying the dataset partitioning ratios had minimal effect on model performance (Supplementary Table 4). To validate the effectiveness of using fusion modalities, we analyzed the impact of solitary modalities on the ViT model’s performance. The fusion modality (CEUS + MRI) demonstrated superior performance compared to solitary modalities in both C-index and time-dependent AUC (Supplementary Fig. 11). In the internal validation cohort of the TA dataset, the fusion modality’s 2-year C-index was 4–7% higher, and the 2-year AUC was 0–6% higher than those of solitary modalities (Supplementary Table 5). For the SR dataset, the fusion modality showed a 4–14% increase in the 2-year C-index and a 6–14% increase in the 2-year AUC (Supplementary Table 5). These results suggest that incorporating information from multiple modalities enhances the prediction of PFS. We also compared several DL models against our ViT model for predicting PFS in rHCC. The results are presented in Supplementary Figs. 12 and 13 and Supplementary Table 6. In the external testing cohort of the TA dataset, our ViT model outperformed other methods on most evaluation metrics, achieving a 2-year C-index of 0.72 compared to 0.68–0.71 for other models (P = 0.073–0.633), and a 2-year AUC of 0.78 compared to 0.72–0.77 (P = 0.019–0.744). Similarly, in the external testing cohort of the SR dataset, our model achieved a 2-year C-index of 0.72 versus 0.63–0.68 for other models (P = 0.064–0.381), and a 2-year AUC of 0.81 compared to 0.72–0.79 (P = 0.022–0.647). These results indicate the superior performance of our ViT model in predicting PFS for rHCC.

Subgroup analyses

We next considered subgroups based on sex, age, tumor size, the number of tumors, manufacturers, and centers in the 2ndTA and 2ndSR datasets. The C-index, time-dependent AUC, and other metrics for these subgroup analyses are presented in Supplementary Figs. 14 and 15 and Supplementary Table 7. The 2-year C-index showed no significant statistical differences among subgroups in both the 2ndTA dataset (0.68–0.76, P = 0.307–0.996) and the 2ndSR dataset (0.68–0.76, P = 0.238–0.892). In the 2ndTA dataset, the 2-year AUC for Center D showed a significant difference compared to Center A (0.90 versus 0.75, P = 0.005). However, there were no significant statistical differences in other subgroups within the 2ndTA dataset (0.75–0.87, P = 0.077–0.951) or across all subgroups in the 2ndSR dataset (0.72–0.88, P = 0.167–0.942). Furthermore, the subgroup analyses demonstrated that HEROVision’s performance remained consistent regardless of sex, age, tumor size, the number of tumors, manufacturers, and centers.

Optimize treatment selection in real-world rHCC

After propensity score matching (PSM), 214 patients (35.0%; 214/611) from the 2ndTA dataset and 214 patients (96.4%; 214/222) from the 2ndSR dataset were matched, demonstrating balanced baseline characteristics for the real-world study (all standardized mean differences [SMDs] <0.200; Supplementary Table 8). Then, HEROVision-TA and -SR were successively applied to the matched 2ndTA group for prognostic stratification and re-stratification. Similarly, HEROVision-SR and -TA were successively applied to the matched 2ndSR group. Supplementary Fig. 16 presents the individual clinical variables and risk scores of these patients.

In the 2ndTA group, 23 out of 214 rHCC patients changed their risk categories after re-stratification by HEROVision-SR. Among them, 23 original high-risk patients could be downgraded to low-risk, if they switched from TA to RHR (Fig. 5a, displayed by the orange to blue branch), constituting 35.9% of the original high-risk patients. According to HEROVision-TA, the median risk score of the original high-risk subgroup (n = 64) was 8.65 (IQR: [5.32, 12.88]). In contrast, the median risk score of the 23 selected patients was reduced to 1.71 (IQR: [1.04, 2.04]) based on HEROVision-SR, which was a significant reduction comparing with their original subgroup (P = 1.400 × 10−8; Fig. 5b). Supplementary Fig. 17a shows that their median risk score decreased from 3.86 (IQR: [1.90, 5.74]) to 1.71 (IQR: [1.04, 2.04]) (P = 0.0023) by changing the treatment, which indicated a significant improvement in the expectation of achieving 2-year PFS. Baseline characteristics (Supplementary Table 9) between the subgroup downgraded from high-risk to low-risk (n = 23) and the subgroup remaining high-risk after re-stratification (n = 41) showed no significant differences (P = 0.101–1.000), except for AFP levels (P < 0.001).

a In the matched 2ndTA group, 23 out of 214 rHCC patients changed their risk categories after re-stratification by HEROVision-SR. Among them, 23 original high-risk patients could be downgraded to low-risk if they switched from TA to RHR (displayed by the orange to blue branch). b Comparison of predicted risk scores between the 64 high-risk patients and the 23 of them who required a change of treatment in the 2ndTA group. c Kaplan–Meier curves of PRS stratified by HEROVision-TA in the matched 2ndTA group. d The same analysis as (c) in the matched 2ndTA group after removing the 23 identified patients. e In the matched 2ndSR group, 10 out of 214 rHCC patients changed their risk categories after re-stratification by HEROVision-TA. Among them, six original high-risk patients could be downgraded to low-risk if they switched from RHR to TA (displayed by the orange to blue branch). f Comparison of predicted risk scores between the 91 high-risk patients and the six of them who required a change of treatment in the 2ndSR group. g Kaplan–Meier curves of PRS stratified by HEROVision-SR in the matched 2ndSR group. h The same analysis as (g) in the matched 2ndSR group after removing the six identified patients. P values were computed using the two-sided Mann–Whitney U test (b, f). Boxes indicate the upper and lower quartiles (Q3 and Q1), with a line at the median. Whiskers extend to the maximum and minimum values within 1.5 times the interquartile range. Outliers are shown as circles and identified via the interquartile range rule. The error bands (dashed lines) represent the 95% confidence intervals, and the P values were calculated using the two-sided Log-rank test (c, d, g, h). Source data are provided as a Source Data file. TA thermal ablation, SR surgical resection, RHR repeat hepatic resection, PFS progression-free survival, PRS post-recurrence survival.

After applying HEROVision-TA in the 2ndTA group for prognostic stratification (Fig. 5c), the post-recurrence survival (PRS) significantly differed between the low- and high-risk subgroups (median PRS, 90.8 months vs. 38.3 months; P = 0.00012). However, if remove the 23 identified patients from the original high-risk subgroup, the median PRS of the rest 41 patients was improved to 45.5 months, suggesting an overall improvement of prognosis may be obtained for the high-risk patients (Fig. 5d).

In the 2ndSR group, 10 out of 214 rHCC patients changed their risk categories after re-stratification by HEROVision-TA. Among them, six original high-risk patients could be downgraded to low-risk if they switched from RHR to TA (Fig. 5e, displayed by the orange to blue branch). According to HEROVision-SR, the median risk score of the original high-risk subgroup (n = 91) was 1.67 (IQR: [1.05, 2.67]). In contrast, the median risk score of the six identified patients was reduced to −2.95 (IQR: [−4.01, −2.69]) based on HEROVision-TA, which was a significant reduction comparing with their original subgroup (P = 0.00077; Fig. 5f). Supplementary Fig. 17b shows that their median risk score decreased from 0.71 (IQR: [0.63, 0.76]) to −2.95 (IQR: [−4.01, −2.69]) (P = 0.0043), if they underwent TA instead of RHR. Baseline characteristics (Supplementary Table 9) between the subgroup downgraded from high-risk to low-risk (n = 6) and the subgroup remaining high-risk after re-stratification (n = 85) revealed no significant differences (P = 0.055–1.000), except for DWI signal (P = 0.001).

After applying HEROVision-SR in the 2ndSR group for prognostic stratification (Fig. 5g), the PRS significantly differed between the low- and high-risk subgroups (median PRS, >72 months vs. >72 months; P = 0.0028). But unfortunately, because only six potentially profitable patients were identified, after removing them from the original high-risk subgroup, changes in the median PRS of the rest 85 patients can be ignored (Fig. 5h).

Discussion

Optimizing curative-intent treatment for patients with rHCC who are at high risk of postoperative early-stage progression is essential for personalized decision-making and improved survival outcomes15. The implementation of risk stratification for rHCC undergoing TA or RHR is likely to be promoted using ensemble learning on multimodal imaging data, such as US and MRI. However, this has not been explored by DL approaches for rHCC in previous studies. Therefore, our study aimed to develop a multimodal-based DL model, named HEROVision, that can optimize the personalized curative-intent treatment selection between TA and RHR for rHCC patients who initially underwent SR as their first treatment. The multimodal images (US and MRI), clinical characteristics, and postoperative follow-up data of 1605 patients with iHCC and rHCC, who underwent curative-intent TA and SR within the Milan criteria in five centers located in different geographical regions of China, were used to train and validate the HEROVision model.

To achieve our goal, HEROVision must first be able to stratify the prognosis of rHCC patients receiving TA and RHR, respectively. As a result, it achieved a 2-year C-index of 0.72 and 0.71, and a 2-year AUC of 0.78 and 0.81 in the independent 2ndTA and 2ndSR datasets, respectively. It consistently and significantly outperformed six major staging systems proposed in various guidelines by comparing C-index and AUC (regardless of time-dependent or 2-year), whether in training, internal validation, or external testing cohorts (all P < 0.002). Furthermore, we found that the 2-year PFS prediction accuracy of the six guideline methods could all be improved after using HEROVision as assistance for rHCC patients. While current staging systems were not specifically designed for recurrent disease and there are no rHCC-specific guidelines, this comparison was intended to validate the effectiveness and potential clinical utility of HEROVision in addressing this critical gap.

After HEROVision-TA and SR were validated independently for their prognosis prediction capabilities in the multicenter external testing cohort, they were applied to conduct personalized treatment selection between TA and RHR for rHCC by prioritizing treatment outcomes. Although we successfully enrolled 833 patients with rHCC in the external testing cohort (2ndTA dataset n = 611 vs. 2ndSR dataset n = 222), only 428 of them were selected for the real-world study by applying 1:1 PSM (214 vs. 214), so that the negative impacts of selection bias and confounding factors between two treatments were minimized. To assess the contribution and importance of various components in the model, we conducted three ablation studies. First, varying the dataset partitioning ratios had minimal effect on model performance, and we aimed for the model to have as much training data as possible, while ensuring the validation set was sufficiently large to effectively reflect the model’s generalization performance. Consequently, the final ratio was chosen as 4:1, which aligns with most literature reports20,21. Second, the performance of the solitary modalities was inferior to that of the fusion modality in both the TA and SR datasets, demonstrating the effectiveness of multimodal fusion. Third, we compared several DL algorithms, with our constructed ViT model outperforming others in the external testing cohort on both the TA and SR datasets. The performance of Convolution-based models was lower than that of Transformer-based models. GC-ViT, an improved variant of the ViT model, did not outperform the original ViT on the TA and SR datasets, likely because it was not specifically designed for medical imaging. Geographic and demographic variability in our retrospective datasets may introduce potential information biases, possibly impacting the model’s generalizability. To address this, we conducted comprehensive subgroup analyses to evaluate HEROVision’s consistent performance across the 2ndSR and 2ndTA datasets. In addition to performing well on datasets from different geographical regions of China, HEROVision’s performance was also assessed across subjects with varying demographics, including age and sex, as well as tumor characteristics such as tumor size and the number of tumors, and across different manufacturers. The model’s performance remained consistent across these subgroups, confirming its robustness and generalizability. However, our dataset lacks racial diversity and international data, which will be incorporated in future research to further minimize potential biases.

In the matched 2ndTA group, 23 out of 64 high-risk patients who underwent TA were identified, and they should receive RHR instead of TA. If this actually happened, their risk scores will be significantly reduced, indicating an effective improvement in the expectation of achieving 2-year PFS. We can question whether this result is only based on model calculations and lacks direct evidence. However, Kaplan–Meier analyses of the real prognostic data also demonstrated that HEROVision-TA achieved accurate stratification in PRS. Moreover, after removing the 23 identified patients from the high-risk group, the median PRS of the rest 41 patients reached 45.5 months, which was much closer to the low-risk group (median PRS: 90.8 months). These results reveal that applying HEROVision-TA and -SR preoperatively for rHCC patients scheduled to undergo TA, is likely to identify a considerable proportion of them who may significantly benefit from switching TA to RHR, resulting in an overall improvement in PRS for the high-risk patients (Fig. 5c, d).

Unfortunately, in the matched 2ndSR group, HEROVision-SR and -TA were not equally effective. After applying the same strategy, only six high-risk patients were identified, whose prognosis may benefit from switching RHR to TA. Because the proportion is very low, the overall impact on the high-risk subgroup is basically negligible. However, these results do not mean that RHR is a priority treatment over TA. We believe it shows that HEROVision can serve as a preoperative decision-maker to objectively and quantitatively guide personalized selection between TA and RHR for rHCC patients.

Currently, there are no established guidelines or definitive classification systems for the management of rHCC7,8,9,10, with most consensus recommendations still following the staging and treatment guidelines for iHCC. The HEROVision model offers an approach to individualized preferences in optimizing treatment for rHCC within the Milan criteria. By accurately re-stratifying patients into good and poor prognosis groups based on their specific clinical and imaging profiles, HEROVision facilitates more personalized treatment decisions with significant clinical implications (Supplementary Fig. 18). For TA, 35.9% of patients initially categorized as high-risk could be downgraded to low-risk after re-stratification, and switching from TA to RHR could probably improve their prognosis and extend survival time, despite the higher average cost associated with surgery22,23. Conversely, for RHR, although only 6.6% of high-risk patients who could benefit from switching RHR to TA, they would have a higher probability of better prognosis, less invasive procedure with lower complication rates, reduced economic burden, and better preservation of liver function24,25. Obviously, the above personalized treatment changes are of great clinical significance. For patients initially categorized as low-risk but upgraded to high-risk following re-stratification, any change in treatment strategy would be unnecessary and might make outcomes worse. For patients who remain low-risk after re-stratification, both treatment options could be effective, and the decision should be made collaboratively by doctors and patients. For those who remained high-risk after re-stratification, more aggressive sequential treatment strategies (such as combining with transarterial chemoembolization [TACE] or systemic therapies) along with implementing closer monitoring might be warranted. Ultimately, the integration of HEROVision into clinical practice has the potential to enhance treatment outcomes, improve hospital efficiency, and contribute to more personalized patient management. By tailoring treatment strategies to the individual risk profiles of rHCC patients, HEROVision could play a critical role in advancing the standard of care and optimizing resource allocation in clinical settings.

In our study, we developed HEROVision using iHCC data and validated it with rHCC data for several reasons. On one hand, the strategy to use iHCC for model development and rHCC for validation was primarily driven by practical constraints. Despite our collaboration with hospitals across northern, central, southern, and western China, assembling a large rHCC dataset for training was challenging due to difficulties in collecting a sufficient number of rHCC patients with comprehensive follow-up data and no additional treatments between interventions. On the other hand, from a pathological and tumor microenvironment (TME) perspective, the biological behavior of rHCC closely mirrors that of iHCC. Time to recurrence has been widely recognized as a biological surrogate marker: early recurrence, typically within 2 years post-surgery, is believed to share the same clonal origin as the iHCC, while late recurrence, occurring after more than 2 years, is thought to arise from a de novo origin, driven by underlying liver damage that persists despite tumor resection26,27,28. Furthermore, Ding et al.29 compared genetic features and found that 52% of rHCCs share the clonal lineage of the initial tumor. Both conditions are characterized by a similar liver environment due to underlying cirrhosis. This biological similarity supports our decision to use iHCC data for model development, offering a practical solution to the challenge of obtaining sufficient rHCC data. Although this approach may not be perfect, it effectively addresses data scarcity and enables meaningful model development. HEROVision demonstrated effectiveness in rHCC patients, as evidenced by our study: the 2-year AUC was 0.90 for the internal validation cohort and 0.78 for the external testing cohort in the TA dataset, and 0.92 and 0.81, respectively, in the SR dataset. Besides that, HEROVision is effective for several other reasons. First, it efficiently integrated US and MRI images by applying the specially designed ViT model with bi-direction feature extraction and non-uniformly scaled tokens17,30,31. Second, it leveraged the strength of DL in feature extraction, while accommodating the complexity of survival data and individual differences, by integrating the ViT model with the Cox regression32. Third, it integrated image DL features with important clinico-radiological variables as independent risk factors to construct nomograms for individual prediction. Therefore, HEROVision integrated preoperative information as much as possible and correlated them with prognostic information as accurate as possible by using smart algorithms.

The lack of interpretability in DL presents challenges, particularly in supervising systems based on complex neural networks33. While HEROVision model generates a risk score to classify patients into high- or low-risk groups, the computational process remains a “black box” due to the inherent complexity of neural networks. Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM), a visualization technique, identifies critical regions in the input image by calculating the gradient of the target class with respect to a specific convolutional layer34. However, the patch-based structure of ViT models often results in heatmaps with scattered distributions across the image, which may lack correlation with clinically relevant features and may not always provide a meaningful understanding of the decision-making35,36. Consequently, these heatmaps may fail to provide concentrated or clinically meaningful visualizations. To address this, we used nomograms to provide a clear and clinically applicable visualization of how individual variables contribute to risk predictions. In the future, integrating molecular data such as genomic markers with DL features holds great potential for improving interpretability, and we plan to explore this avenue in subsequent studies.

Our multivariate Cox regression analysis indicates that tumor imaging characteristics, postoperative adjuvant therapies, and coagulation status are key factors for both TA and SR, which is consistent with the results of previous studies37,38,39,40. Both coagulation and tumor markers play significant roles in the TME in HCC. Activation of the coagulation system influences the TME by recruiting and activating immune cells, potentially affecting HCC development and immune evasion, thus impacting prognosis40. Although the mechanism of how elevated carbohydrate antigen 19–9 (CA19-9) levels contribute to poor prognosis remains unclear in HCC patients, previous study indicated CA19-9 might impact the TME by influencing various physiological processes, potentially promoting tumor progression41.

Our study has several limitations. First, it was a retrospective multicenter study. Even though we minimized bias through the real-world study design based on PSM, whether HEROVision can provide benefit for rHCC patients through personalized treatment decision-making or not still needs to be verified in high-level prospective studies, which is what we are conducting in the next step. Second, because the number of patients with rHCC who underwent RHR is limited in clinical practice, we were forced to train HEROVision by employing iHCC data. Although the results proved that our strategy was correct, the performance of HEROVision is likely to be enhanced if it is sufficiently trained by real rHCC data. Third, HEROVision was developed specifically for patients experiencing early-stage recurrence after SR. As such, it may not be applicable to patients with advanced-stage recurrence or those who received non-surgical or non-ablative treatments, such as TACE or systemic therapies, between initial resection and subsequent recurrences. Fourth, for patients who remain high-risk after re-stratification, HEROVision does not recommend a specific next-step treatment. However, more aggressive sequential treatment and closer monitoring strategies may potentially improve outcomes. Further studies are needed to validate their efficacy. Finally, as more cases are accumulated, the use of CT—a commonly employed imaging modality for surveillance in clinical practice—will enhance HEROVision’s accuracy and generalizability.

In summary, by analyzing 1605 patients with HCC who underwent curative-intent TA and SR, we developed and validated a DL based HEROVision model. It integrates preoperative US and MRI, as well as clinical variables, to predict tumor progression and optimize personalized curative-intent treatment for early-stage rHCC. HEROVision holds promise to complement the existing clinical guidelines and enhance patient care in the management of early-stage rHCC.

Methods

Patient population

This multicenter retrospective study adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Review Board of The First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the requirement for written informed consent was waived. In compliance with data privacy, ethical standards, and institutional policies, patient imaging data is used exclusively for model development and validation. This process requires no additional tests or patient involvement, and therefore, no extra compensation is generally necessary.

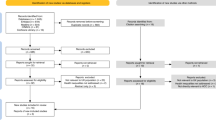

We enrolled 11,409 patients with HCC who underwent either ultrasound-guided local ablation or hepatectomy at five centers: Center A (The First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine) located in central China, Center B (Peking University Cancer Hospital) situated in northern China, Center C (The Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University) positioned in southern China, Center D (West China Hospital, Sichuan University) located in western China, and Center E (Fifth Medical Center of Chinese PLA General Hospital) situated in northern China. These centers are geographically distant from each other and collectively cover the HCC patient population from different regions across China. Details of patient participation are shown in Fig. 1 and Supplementary Note 1.

Finally, the study comprised 1605 patients with HCC. Among the patients with iHCC, 772 underwent first-line treatment between January 2015 and December 2022 at Center A, including 391 cases of TA (1stTA dataset) and 381 cases of SR (1stSR dataset). The 1stTA and 1stSR datasets were divided into a training cohort (n = 311 and n = 322, respectively) and an internal validation cohort (n = 80 and n = 59, respectively) in a 4:1 ratio, based on chronological order. Among the patients with rHCC, 833 received second-line therapies between May 2010 and August 2023 from five centers, including 611 cases of TA (2ndTA dataset) and 222 cases of SR (2ndSR dataset), which were designated as the external testing cohorts. PSM (1:1) was performed using binary logistic regression to reduce the effects of selection bias and confounding factors between the 2ndTA and 2ndSR datasets42. After PSM, 214 patients from the 2ndTA dataset and 214 patients from the 2ndSR dataset were successfully matched. Sex and age were determined based on the government-issued IDs. The sex and age distributions for the training, internal validation, and external testing cohorts are provided. Sex was not relevant to the model’s development or validation. Gender analysis was not conducted primarily because the objective of this study was to evaluate the performance of HEROVision, rather than investigate potential differences between sex and gender. Additionally, self-identified gender information was not collected from the patients.

Clinical and imaging data acquisition and preparation

Demographic and clinico-radiological characteristics were collected from electronic medical records system (Supplementary Note 2). Multimodal images, including T2-weighted imaging (T2WI), diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI; b-value = 800 s/mm2), grayscale ultrasound, and dynamic CEUS (Supplementary Table 1) were acquired from the five institutions. Detailed procedural information is depicted in Fig. 2a, b, and comprehensive treatment and imaging protocols can be found in Supplementary Note 3–5 and Table S1.

Study endpoints

The primary study endpoint was PFS, with secondary endpoints including overall survival (OS) and PRS. PFS was defined as the duration between initial treatment (for iHCC) or second treatment (for rHCC) and tumor progression (including local tumor progression, intrahepatic distance recurrence, or extrahepatic metastasis) or until the last follow-up43. OS was defined as the time between the initial TA or SR and death or last follow-up, whereas PRS was defined as the period from the first diagnosis of recurrence to death or last follow-up44. The final follow-up dates were 15 July 2023 (Center A), 25 January 2024 (Center B), 30 September 2023 (Center C), 15 May 2024 (Center D), and 1 January 2024 (Center E).

Development and validation of HEROVision-TA and -SR models

The HEROVision-TA and -SR models, based on the 1stTA and 1stSR datasets, were developed using a ViT Cox proportional hazard regression algorithm to predict the probability of PFS. For each patient, this algorithm automatically integrated images of T2WI (n = 3), DWI (n = 3), grayscale US (n = 2), and CEUS (n = 3). For each image, it learned attention-weighted features horizontally and vertically, respectively (Fig. 2b). Subsequently, convolutional layers were employed for feature fusion, followed by Cox regression to derive the risk score. The model extracted a total of 1408 features from annotated regions of interest across all modalities, intelligently learning key features specific for predicting PFS in the 1stTA and 1stSR datasets, respectively. A comprehensive analysis of the HEROVision-TA and -SR models is presented in Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Note 6.

To consistently improve the performance of both models and facilitate comprehensive utilization, we developed nomograms that combined risk scores from the clinical and ViT models through multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression. This approach enabled personalized predictions in the TA and SR groups. Clinical factors with a significance level of P < 0.20 in the univariate analysis underwent a stepwise multivariable analysis using the Akaike information criterion and previous studies to determine their inclusion in the clinical model20,45.

Transfer HEROVision model to rHCC for PFS prediction

To predict the PFS in patients with rHCC, the 2ndTA and 2ndSR datasets served as external testing cohorts (Figs. 1 and 2c). Patients undergoing TA or SR were categorized into high- and low-risk subgroups based on cutoff values determined by the “survminer 0.5.0” package in R software (version 4.2.2; https://www.rproject.org) from the training cohorts. Subsequently, the internal validation and external testing cohorts were stratified into two risk subgroups according to the optimal thresholds derived from the training cohorts.

The performances of the HEROVision-TA and -SR models in all cohorts were assessed using metrics such as C-index and the time-dependent AUC. Additionally, the performance of the HEROVision model in quantitatively predicting 2-year PFS across all cohorts was evaluated using measures such as AUC, accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and F1 score. A decision curve analysis was conducted to evaluate clinical utility.

Comparisons with major guideline methods

The HEROVision model was compared to different prognostic methods proposed in major guidelines for predicting the 2-year PFS in patients with rHCC (Fig. 2c). Six major staging systems were evaluated in this study, including the eighth American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system46, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system47, Chinese Liver Cancer (CNLC) staging system48, Hong Kong Liver Cancer (HKLC) staging system49, Italian Liver Cancer (ITA.LI.CA) system50, and the fifth modified Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) staging system51.

Ablation studies

We performed three ablation studies, investigating different training and internal validation cohort splitting ratios, various modality models, and different DL models. For the splitting ratios of the TA and SR datasets, based on chronological order, we retrained our ViT model under three settings, using 3/4, 4/5, and 5/6 of the training cohort, respectively, and then validated the model in each setting on the internal validation cohort. In exploring different modality models, we assessed the contributions of CEUS and MRI modalities to the final performance of our ViT model on both the training and internal validation cohorts. Lastly, for different DL models, we compared our ViT model with other DL models on both TA and SR datasets using the same experimental setup. This included two CNN models: ResNet5052 and ConvNext53, and two Transformer-based models: original ViT17 and GC-ViT54.

Subgroup analyses

To address potential variability and ensure the robustness of the findings, we conducted subgroup analyses in the 2ndTA and 2ndSR datasets, including sex (female and male), age (≤60 years and >60 years), tumor size (≤3 cm and >3 cm), the number of tumors (solitary and multiple), manufacturers (MyLab90 Xvision, Logiq E9, Siemens Acuson Sequoia, and Resona 7), and centers (Centers A, B, C, D, and E).

Real-world study of cross-stratification and treatment optimization for rHCC

PSM is a widely used method in medical research to balance covariates between treatment groups55. However, the validity of inferences regarding treatment effects based on PSM depends on whether the matched groups have comparable distributions of the measured baseline covariates. To reduce potential confounding effects arising from variations in baseline characteristics in our real-world study, the efficacy of the models in guiding cross-stratification was assessed using PSM at a 1:1 ratio for 2-year PFS56. Further details on the PSM methodology are provided in Supplementary Note 7.

To optimize curative-intent treatment strategy selection between TA and RHR for rHCC, a stratification approach was applied to the external testing cohort. The original low-risk and high-risk stratifications in the 2ndTA dataset (2ndTA-oriLR and 2ndTA-oriHR) given by the HEROVision-TA model, were re-stratified into the low-risk and high-risk groups (2ndTA-newLR and 2ndTA-newHR) by applying the HEROVision-SR model. Similarly, the original low-risk and high-risk stratifications in the 2ndSR dataset (2ndSR-oriLR and 2ndSR-oriHR) given by the HEROVision-SR model, were re-stratified into the low-risk and high-risk groups (2ndSR-newLR and 2ndSR-newHR) by applying the HEROVision-TA model. Sankey diagrams were constructed, focusing specifically on patients with rHCC who were initially classified as high-risk (2ndTA-oriHR and 2ndSR-oriHR) by one treatment, but were re-categorized as low-risk (2ndTA-newLR and 2ndSR-newLR) after re-stratification using the other treatment. Moreover, we compared the PRS before and after re-stratification in the 2ndTA and 2ndSR datasets.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was conducted using R software and Python (version 3.7; http://www.python.org). Categorical variables were compared between the two groups using either the χ2 or Fisher’s exact test. Continuous data were evaluated using either the two-sample t test or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, as appropriate. Clinical data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median (25 quantile, 75 quantile). The performance of models was assessed using the C-index and time-dependent AUC, and comparisons were made using the DeLong test. Survival curves were estimated using Kaplan–Meier analysis with the Log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate analyses using Cox proportional hazards regression models were conducted to identify clinical factors associated with PFS. The optimal cutoff values for the prognostic nutritional index were determined using the maximum Youden index. The analyses provided P values, hazard ratio, and 95% CI. All statistical tests were two-sided. The threshold for statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Balance in baseline characteristics between 2ndTA and 2ndSR datasets was evaluated by the SMD.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The original images and clinical data used in this study are subject to access restrictions due to patient privacy and data protection laws. These datasets contain medical imaging data, which are governed by the hospital’s strict data management policies to ensure patient confidentiality and compliance. Access to the data is restricted to non-commercial, academic research purposes only. Interested parties may request access by contacting the corresponding authors at tiananjiang@zju.edu.cn or kun.wang@ia.ac.cn. All requests will be reviewed promptly, and access will be granted within 20 working days, subject to institutional approval. Access will be provided for a period of 12 months following approval, and any additional extensions will be reviewed on a case-by-case basis. Please note that the data will only be made available to researchers affiliated with recognized academic institutions, and use will be limited to academic research and non-commercial purposes. Data cannot be shared with external parties or used for commercial purposes without prior written approval from the corresponding author and the institution. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

All code related to this study was developed in Python and is publicly available under the MIT License, an open-source license approved by the Open Source Initiative. The full source code, including modules for image extraction, preprocessing, and deep learning model construction, has been deposited in the following GitHub repository57: https://github.com/Rujinyu/HEROVision/tree/main. The code is freely available for non-commercial research use. For any commercial or clinical use, please contact the corresponding author for permission.

References

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 74, 229–263 (2024).

Singal, A., Kanwal, F. & Llovet, J. Global trends in hepatocellular carcinoma epidemiology: implications for screening, prevention and therapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 20, 864–884 (2023).

Reig, M. et al. BCLC strategy for prognosis prediction and treatment recommendation: the 2022 update. J. Hepatol. 76, 681–693 (2022).

Lim, K. C. et al. Systematic review of outcomes of liver resection for early hepatocellular carcinoma within the Milan criteria. Br. J. Surg. 99, 1622–1629 (2012).

Bai, X. M. et al. The 10-year survival analysis of radiofrequency ablation for solitary hepatocellular carcinoma 5 cm or smaller: primary versus recurrent HCC. Radiology 300, 458–469 (2021).

Papaconstantinou, D., Tsilimigras, D. I. & Pawlik, T. M. Recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma: patterns, detection, staging and treatment. J. Hepatocell. Carcinoma 9, 947–957 (2022).

Marrero, J. A. et al. Diagnosis, staging, and management of hepatocellular carcinoma: 2018 Practice Guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 68, 723–750 (2018).

EASL. Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 69, 182–236 (2018).

Vogel, A. et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 29, iv238–iv255 (2018).

Heimbach, J. K. et al. AASLD guidelines for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 67, 358–380 (2018).

Zhong, J. H. et al. Repeat hepatic resection versus radiofrequency ablation for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma: retrospective multicentre study. Br. J. Surg. 109, 71–78 (2021).

Song, K. D. et al. Repeated hepatic resection versus radiofrequency ablation for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatic resection: a propensity score matching study. Radiology 275, 599–608 (2015).

Machairas N. et al. Meta-analysis of repeat hepatectomy versus radiofrequency ablation for recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancers 14, 5398 (2022).

Feng, Y. et al. Radiofrequency ablation versus repeat resection for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma (≤5 cm) after initial curative resection. Eur. Radio. 30, 6357–6368 (2020).

Xia, Y. et al. Long-term effects of repeat hepatectomy vs percutaneous radiofrequency ablation among patients with recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 6, 255–263 (2020).

Bansal, S. et al. A new proposal for secondary surveillance following potentially curative therapy of HCC: alternating MRI and CEUS. Abdom. Radio. 47, 618–629 (2022).

Dosovitskiy A, et al. An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. In International Conference on Learning Representations (2020).

Bertasius G., Wang H., Torresani L. Is space-time attention all you need for video understanding? In ICML (2021).

Bai, Y., Mei, J., Yuille, A. L. & Xie, C. Are transformers more robust than CNNs? Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 34, 26831–26843 (2021).

Liu, F. et al. Deep learning radiomics based on contrast-enhanced ultrasound might optimize curative treatments for very-early or early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Liver Cancer 9, 397–413 (2020).

Wang, F. et al. Multitask deep learning for prediction of microvascular invasion and recurrence-free survival in hepatocellular carcinoma based on MRI images. Liver Int. 44, 1351–1362 (2024).

Ikeda, K. et al. Cost-effectiveness of radiofrequency ablation and surgical therapy for small hepatocellular carcinoma of 3 cm or less in diameter. Hepatol. Res. 33, 241–249 (2005).

Wu, X., Lokken, R. P. & Mehta, N. Optimal treatment for small HCC (<3 cm): resection, liver transplantation, or locoregional therapy? JHEP Rep. 5, 100781 (2023).

Lee, D. H. et al. Laparoscopic liver resection versus percutaneous radiofrequency ablation for small single nodular hepatocellular carcinoma: comparison of treatment outcomes. Liver Cancer 10, 25–37 (2021).

Xu, X. L., Liu, X. D., Liang, M. & Luo, B. M. Radiofrequency ablation versus hepatic resection for small hepatocellular carcinoma: systematic review of randomized controlled trials with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Radiology 287, 461–472 (2018).

Imamura, H. et al. Risk factors contributing to early and late phase intrahepatic recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatectomy. J. Hepatol. 38, 200–207 (2003).

Wu, J. C. et al. Risk factors for early and late recurrence in hepatitis B-related hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 51, 890–897 (2009).

Yoh, T. et al. Surgery for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma: achieving long-term survival. Ann. Surg. 273, 792–799 (2021).

Ding X. et al. Genomic and epigenomic features of primary and recurrent hepatocellular carcinomas. Gastroenterology 157, 1630–1645.e6 (2020).

Mo Y. et al. Hover-trans: anatomy-aware hover-transformer for roi-free breast cancer diagnosis in ultrasound images. In IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging (2023).

Liu Z. et al. Swin transformer: hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference On Computer Vision (2021).

Breslow N. E. Analysis of survival data under the proportional hazards model. In International Statistical Review/Revue Internationale de Statistique, 45–57 (1975).

Gulum, M. A., Trombley, C. M. & Kantardzic, M. A review of explainable deep learning cancer detection models in medical imaging. Appl. Sci. 11, 4573 (2021).

Selvaraju R. R. et al. Grad-cam: visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference On Computer Vision (2017).

Leem S., Seo H. Attention guided CAM: visual explanations of vision transformer guided by self-attention. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (2024).

Shamai, G. et al. Deep learning-based image analysis predicts PD-L1 status from H&E-stained histopathology images in breast cancer. Nat. Commun. 13, 6753 (2022).

Jha, R. C. et al. Small hepatocellular carcinoma: MRI findings for predicting tumor growth rates. Acad. Radio. 21, 1455–1464 (2014).

Cabibbo G. et al. Navigating the landscape of liver cancer management: study designs in clinical trials and clinical practice. J. Hepatol. 80, 957–966 (2024).

Xiang, C. et al. Effect of transarterial chemoembolization as postoperative adjuvant therapy for intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma with microvascular invasion: a multicenter cohort study. Int. J. Surg. 110, 315–323 (2024).

He Q., Yang J. & Jin Y. Immune infiltration and clinical significance analyses of the coagulation-related genes in hepatocellular carcinoma. Brief Bioinform. 23, bbac291 (2022).

Luo, G. et al. Roles of CA19-9 in pancreatic cancer: biomarker, predictor and promoter. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 1875, 188409 (2021).

Rosenbaum, P. R. & Rubin, D. B. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 70, 41–55 (1983).

Doyle, A. et al. Outcomes of radiofrequency ablation as first-line therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma less than 3 cm in potentially transplantable patients. J. Hepatol. 70, 866–873 (2019).

Yan, W. T. et al. Predictors and long-term prognosis of early and late recurrence for patients undergoing hepatic resection of hepatocellular carcinoma: a large-scale multicenter study. Hepatobil. Surg. Nutr. 12, 155–168 (2023).

Akaike, H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans. Autom. control 19, 716–723 (1974).

Amin M. B. et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. Springer (2017).

Singal, A. G. et al. AASLD Practice Guidance on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 78, 1922–1965 (2023).

Commission GOoNH. Standard for diagnosis and treatment of primary liver cancer (2022 edition). J. Clin. Hepatol. 38, 306–321 (2022).

Yau, T. et al. Development of Hong Kong Liver Cancer staging system with treatment stratification for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 146, 1691–1700.e1693 (2014).

Farinati, F. et al. Development and validation of a new prognostic system for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS Med. 13, e1002006 (2016).

Korean Liver Cancer Association & National Cancer Center. 2018 Korean Liver Cancer Association-National Cancer Center Korea Practice Guidelines for the Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Korean J. Radiol. 20, 1042–1113 (2019).

He K., Zhang X., Ren S. & Sun J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference On Computer Vision And Pattern Recognition (2016).

Liu Z. et al. A convnet for the 2020s. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference On Computer Vision And Pattern Recognition (2022).

Hatamizadeh A., Yin H., Heinrich G., Kautz J. & Molchanov P. Global context vision transformers. In International Conference on Machine Learning. (PMLR, 2023).

Austin, P. C. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity‐score matched samples. Stat. Med. 28, 3083–3107 (2009).

Ali, M. S. et al. Reporting of covariate selection and balance assessment in propensity score analysis is suboptimal: a systematic review. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 68, 112–121 (2015).

Ru J. Vision transformer-based biomarker can optimize curative-intent treatment for patients with recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancers 15, 1538 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This study has received funding by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Nos. 2023YFF1204600 [K.W.], 2022YFC2407405 [K.W.], and 2022YFC2405505 [T.J.]), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 82027803 [T.J.], 82441010 [P.L.], 82441011 [K.W.], 92159305 [P.L.], 92259303 [K.W.], 62027901 [J.T.], 82272029 [K.W.], 82171937 [Q.Z.], and 81227901 [J.T.]), Key Research and Development Project of Zhejiang Province (No. 2024C03092 [T.J.]), National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2022YFC2405505 [T.J.]), Beijing Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (No. JQ22013 [K.W.]), and Science and Technology Planning Program of Guangzhou, China (No. 2023A03J0218 [K.L.]). The authors would like to acknowledge the instrumental and technical support of the Multimodal Biomedical Imaging Experimental Platform, Institute of Automation, Chinese Academy of Sciences. They would also like to thank The First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Peking University Cancer Hospital, The Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, and the Fifth Medical Center of Chinese PLA General Hospital for providing clinical and imaging data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concept and design: K.Z., J.R., W.W., K.W., and T.J. Acquisition of data: K.Z., L.M., W.W., Q.M., Q.X., and J.W. Analysis and interpretation of data: K.Z., J.R., W.W., and J.P. Drafting of the manuscript: K.Z., J.R., W.W., and K.W. Critical revision of the manuscript: K.Z., J.R., W.W., Q.M., F.G., J.W., Z.D., Q.X., L.M., H.Z., J.P., L.X., Q.Z., J.T., J.Y., P.L., H.W., K.L., W.Y., K.W., and T.J. Statistical analysis: K.Z., J.R., J.P., and H.Z. Study supervision: J.Y., P.L., H.W., K.L., W.Y., K.W., and T.J.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, K., Ru, J., Wang, W. et al. Vision transformer-based model can optimize curative-intent treatment for patients with recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Commun 16, 4081 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59197-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59197-0