Abstract

Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) remodels the host chromatin structure and induces a host-to-virus transcriptional switch during lytic infection. We combine super-resolution imaging and chromosome-capture technologies to identify the mechanism of remodeling. We show that the host chromatin undergoes massive condensation caused by the hijacking of RNA polymerase II (RNAP II) and topoisomerase I (TOP1). In addition, HSV-1 infection results in the rearrangement of topologically associating domains and loops, although the A/B compartments are maintained in the host. The position of viral genomes and their association with RNAP II and cohesin is determined nanometrically. We reveal specific host–HSV-1 genome interactions and enrichment of upregulated human genes in the most contacting regions. Finally, TOP1 inhibition fully blocks HSV-1 infection, suggesting possible antiviral strategies. This viral mechanism of host chromatin rewiring sheds light on the role of transcription in chromatin architecture.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In all eukaryotes, the mechanisms that direct the genome’s three-dimensional (3D) structure are key to understanding the processes that govern life. Eukaryotic DNA is organized in nucleosome clutches that form chromatin fibers, which condense into secondary and tertiary structures, and eventually assemble into highly compacted mitotic chromosomes1,2,3,4. Human chromatin organization is strongly regulated, and its different levels of compaction play a vital role in the state of the cell3,5. Some of the main chromatin arrangements are the A and B compartments, which contain transcriptionally active euchromatin and transcriptionally repressed heterochromatin, respectively6,7. These compartments include topologically associating domains (TADs), formed by cohesin-extruded loops anchored by boundaries that are highly enriched in CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF)8,9,10,11,12,13. Loop formation is a dynamic process that regulates physical contacts between DNA regions, which controls DNA accessibility, and links DNA structure with gene expression11,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21. In recent years, genomic techniques and single-molecule localization microscopy (SMLM) approaches have revealed transcription to be one of the potential key players in controlling genome architecture7,15,17,22,23,24,25. Inhibition of transcription results in global compaction of the chromatin, which concentrates at the nucleus edges and the perinucleolar region22,26. The negative supercoiling generated by the activity of RNA polymerase II (RNAP II) is an important regulator for loop formation in vivo22. However, further investigation is needed to dissect the transcription-mediated mechanisms that shape chromatin architecture.

DNA viruses largely depend on the molecular machinery of host cells and provide an attractive model for elucidating central aspects of eukaryotic gene regulation27. Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) is a double-stranded DNA virus that initially infects human epithelial cells by lytic cycle. HSV-1 then establishes lifelong infections in the surrounding sensory neurons by latent cycle28. In the lytic infection, how HSV-1 competes with the human genome for cell resources, and how this affects nuclear organization, have remained largely unexplored. Previous works have shown that the host genome is marginalized at late times post lytic infection29,30,31. Concurrently, the nuclear lamina stiffness increases32 and the nuclear volume expands29. However, the specific architectural changes in the host chromatin remain unknown. Currently, there is no consensus about the organization of the relatively large genome of HSV-1 (~152 kb), its putative unstable associations with host intact nucleosomes, or the nucleosome density of the viral DNA33,34,35,36,37,38. During lytic infection, HSV-1 transcription occurs inside the viral replication compartments (VRCs)39,40 in the nucleus and is dependent on the host RNAP II and the phosphorylation in the serine 5 of its C-terminal domain (herein, RNAP II phSer5)41,42,43,44. Sequestering cellular RNAP II to the viral genome alters the occupancy of RNAP II on human genes, leading to a drastic deregulation of cellular transcription45,46,47. The expression of viral genes is sequentially coordinated in three phases with a cascade that regulates the transcription of the three gene groups: the immediate early (IE), the early (E), and the late (L) genes48,49. IE genes mostly encode transcription factors, such as ICP4, while E and L genes encode replication machinery factors and virion structural proteins, respectively50,51,52,53. Interestingly, as the viral genes are being highly transcribed by RNAP II, the human genome undergoes a major shutoff47,54. Despite the efforts to elucidate the mechanisms that switch from human to virus expression, we are far from understanding how the changes in viral and cellular chromatin are mediated, and specifically, how the human genome is altered and manipulated by the virus28. A potential limitation in previous studies has been the lack of single-cell analysis and high-resolution methods.

To overcome these difficulties and to account for inherent cell heterogenicity, we took advantage of a variety of SMLM techniques, including stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM)55,56,57, DNA point accumulation for imaging in nanoscale topography (PAINT)58, and OligoSTORM59, to study the reshaping of the human DNA in HSV-1 infected cells at the single-cell level with nanometric resolution. We combined these techniques with genomic Hi-C approaches to visualize the changes of the chromatin structure. In agreement with previous reports29,30, we observed that the active viral transcriptional state and the repressed state of the human genome occur in parallel with the changes in the host chromatin spatial distribution inside the nucleus. We determined that the DNA compaction induced by HSV-1 infection is dependent on the major loss of RNAP II, cohesin, and DNA topoisomerase I (TOP1) from the host genome, and on their sequestration to the VRCs. Inspection at nanoscale resolution revealed that the newly replicated viral genomes are arranged in clusters associated with active RNAP II and cohesin in the VRC. Importantly, inhibition of TOP1 fully blocked HSV-1 infection. Finally, by combining SMLM with Hi-C, we found that the genome of HSV-1 preferentially contacts the A compartment of the host chromosomes; in particular, it interacts with gene-dense genomic regions that remain transcriptionally active and harbor human genes needed for viral infection. Despite the global loss of insulation and loops at late times post-infection, some of these domains are rewired and form new loops. Remarkably, chromatin compartments are maintained in the highly compacted human genome, indicating that the overall 3D spatial organization of chromatin is resilient to major physical reshaping induced by HSV-1.

Results

Human chromatin undergoes high compaction and relocalizes without major epigenetic changes after HSV-1 infection

To study the human chromatin reorganization at the nanometric level at different times post–HSV-1 infection, we performed single-color STORM imaging of the genome of HSV-1 infected A549 cells. The nucleotide analog 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxycytidine (EdC) was added to the medium before HSV-1 infection to ensure its incorporation and labeling of the whole human DNA. EdC-labeled A549 cells were infected with HSV-1 KOS strain and fixed at different times post-infection that correspond to the different states of the HSV-1 lytic cycle: IE, at 1 h post-infection (hpi); E, at 3 hpi; and L, at 8 hpi (Fig. 1a). The times post-infection were selected based on the expression of the IE protein ICP4, the E protein ICP8, and the L protein ICP5 (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Remodeling of human DNA (hDNA) started as early as 1 hpi and continued to condense until it reached a state of very high compaction at 8 hpi (Fig. 1b). This compaction was accompanied by a change in the hDNA spatial distribution inside the nucleus, with it becoming highly condensed in the nuclear periphery, as previously described29,30,31,60, with a few accumulations in the center of the nucleus, which were visible at 8 hpi. The same host DNA compaction and spatial distribution was also confirmed in human fibroblasts (hFibs) upon HSV-1 infection (Supplementary Fig. 1b).

a Scheme showing hDNA labeling. A549 cells were cultured in medium supplemented with 5 µM EdC for 64 h before HSV-1 infection to ensure the complete labeling of the whole cellular DNA. Cells were infected with HSV-1 (MOI = 3), and fixed at different times post infection. Samples were then labeled with the azide-Alexa 647 (AF647). b Representative STORM density rendering images of hDNA in mock or HSV-1 infected A549 cells. Top: Whole nucleus. Scale bar: 2 µm. Bottom: Zoomed-in regions are shown in yellow boxes. Scale bar: 200 nm. Differences in DNA density follow the color scale bar; top: 0.00001 nm−2 (dark blue) to 0.01281 nm−2 (white); bottom: 0.00001 nm−2 (dark blue) to 0.02001 nm−2 (white). c Cumulative distribution of the Voronoi polygon densities for hDNA distribution in mock (n = 29), and HSV-1 infected cells at 1 hpi (n = 27), 3 hpi (n = 27), and 8 hpi (n = 45). Thick lines show the median and light colors, the interquartile range. ns, p > 0.05; ****p < 0.0001, calculated by ordinary one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnet’s multiple comparison test against mock. d Percentage of hDNA-free area per nucleus of EdC-AF647 labeled hDNA in mock (n = 29), and HSV-1 infected cells at 1 hpi (n = 27), 3 hpi (n = 27), and 8 hpi (n = 45). Mean and SD represented; ns, p > 0.05; ****p < 0.0001, calculated by ordinary one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test against mock. e Cropped representative STORM-PAINT images of EdC-AF647 labeled hDNA (magenta), immunolabeled ICP4 (cyan), and their merge in mock and HSV-1 infected cells. Yellow dotted line delimits the location of HC and VRCs. Scale bar: 2 µm f (Top) Cropped representative STORM-PAINT images of EdC-AF647 labeled hDNA (magenta), immunolabeled H3 (green), and their merge in mock and HSV-1 infected A549 cells. Scale bar: 2 µm. (Bottom) Zoomed-in regions are shown inside yellow boxes. Scale bar: 200 nm. g Percentage of hDNA-free and H3-free areas per nucleus quantified from SR images of mock (n = 16), or HSV-1 infected A549 cells at 1 hpi (n = 13), 3 hpi (n = 16), and 8 hpi (n = 19). Mean and SD are represented. ns, p > 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001, calculated by ordinary one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test against hDNA or H3 mock, correspondingly. h Percentage of H3 clusters located in the HC over the whole nucleus at 3 hpi (n = 16) and 8 hpi (n = 19) in HSV-1 infected A549 cells. Mean and SD are shown. ns, p > 0.05, calculated by unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t test. i, j Dot plots showing the median number of localizations per cluster (i) and the median area per cluster (j) in mock (n = 16), and HSV-1 infected cells at 1 hpi (n = 13), 3 hpi (n = 16), and 8 hpi (n = 19). Analysis performed on H3 clusters localized in the whole nucleus for mock and 1 hpi and in the HC for 3 hpi and 8 hpi. Mean and SD are shown. ns, p > 0.05; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001, calculated by ordinary one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test against mock. k hDNA density as a function of the distance from the center of the H3 clutch in mock (n = 12), and HSV-1 infected cells at 1 hpi (n = 8), 3 hpi (n = 16), and 8 hpi (n = 18). Density is measured inside rings of increasing search radii. Mean and SD shown. l-o Dot plots showing the percentage of histone-free area (l), the cluster density (m), median localizations per cluster (n) and median area per cluster (o) for H3K27me3 in HSV-1 infected A549 cells. Mock (n = 13), 1 hpi (n = 11), 3 hpi (n = 10), 4 hpi (n = 9), 6 hpi (n = 13), 8 hpi (n = 12). Mean and SD are shown. ns, p > 0.05; **p < 0.01; ****p < 0.0001, calculated by ordinary one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test against mock. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. p values are indicated in Supplementary Data 1.

We then analyzed the spatial organization of the human genome by Voronoi tessellation quantitative analysis. Voronoi analysis uses single localizations as seeds for Voronoi polygon areas (tessels). The area of each tessel is inversely proportional to the DNA density, and it has been proven to be an accurate tool for measuring DNA compaction5,61,62. We found a clear increase in the density distribution of hDNA at the different times post-infection, with a maximum level at 8 hpi (Fig. 1c). The relocation of hDNA left hDNA-free areas inside the nucleoplasm that were measured by black space analysis63. These areas occupied 40.2% of the whole nuclear area at 3 hpi, and 70.4% at 8 hpi (Fig. 1d). We next investigated whether the free space was occupied by the VRCs by co-visualizing the hDNA together with viral protein ICP4 using STORM-PAINT5. As the infection progressed, we could clearly distinguish two compartments inside the nucleus: the VRC and the nuclear volume occupied by the hDNA, which we named host compartment (HC). The VRCs started to form between 1 hpi and 3 hpi, and contained little if any hDNA (Fig. 1e).

As nucleosome organization can affect the compaction of hDNA, and H1 linker histone was reported to be excluded from VRCs64, we next investigated the spatial distribution of the histone H3 and hDNA during HSV-1 infection. H3 is a nucleosome core histone, hence we used it as a proxy to reveal nucleosome arrangement within the chromatin fiber. STORM-PAINT co-imaging of the hDNA and H3 showed at the nanometric level that H3 was tightly associated with hDNA and occupied the same nuclear area (Fig. 1f and Supplementary Fig. 1c, d). As expected, and using a previously developed cluster identification algorithm3 (Supplementary Fig. 1e, Supplementary Note 1), we found that H3 in mock-infected cells (herein, mock cells) was clustered in discrete and spatially separated nucleosome clutches3,5. During the infection progression, our results show a severe reorganization of the hDNA and the nucleosome clutches, with high-density accumulations of the chromatin fibers at the nuclear edge (Fig. 1f). This reorganization correlated with the expansion of hDNA-free and H3-free nuclear areas quantified by black space analysis63 (Fig. 1g). From 3 hpi onwards, we could clearly distinguish VRCs and HC. By calculating the ratio of H3 clusters in the HC over the total number of H3 clusters in the whole nucleus area, we found that 94.8% and 95.9% of the H3 clusters localized in the HC at 3 hpi and 8 hpi, respectively (Fig. 1h). Our results indicate that histones are mostly absent in the VRC, consistently with previous works64,65. Notably, during latent infection, HSV-1 has been reported to associate with histones66,67,68, and in one study, although histones were reported to associate with the viral genome during lytic infection, this association decreased at late stages post-infection69. From 3 hpi onwards, we observed denser and bigger nucleosome clutches within the HC (Fig. 1i, j). To address whether HSV-1 infection altered the packaging of the DNA around clutches, we analyzed the density of hDNA as a measure of the distance to the center of the H3 clutches. The hDNA density increased showing a progressively tighter association of hDNA to nucleosomes at later times post-infection (Fig. 1k). These results suggest that both hDNA and nucleosome clutches undergo a major coupled compaction during infection, and that nucleosome histones remain tightly associated with hDNA.

Next, we investigated whether the compaction of the human chromatin was due to global heterochromatinization or to changes of a subset of epigenetic modifications induced by HSV-1 infection. We used STORM imaging to analyze the distribution and abundance of the heterochromatin-specific histone markers H3K27me370,71 and H3K9me372,73, as well as the active chromatin marker H3K9ac74 and total H3 (Fig. 1l–o, Supplementary Fig. 2 and 3, see also Supplementary Note 2). As the infection progressed, H3 clusters re-localized and became closer to the edge of the nucleus, while some clusters accumulated in the central part of the nucleoplasm, as expected (Supplementary Fig. 2a). H3K27me3 and H3K9me3 showed a defined clustered pattern (Supplementary Fig. 2b,c), with clusters packed at the peripheral and central regions of the nucleus, in accordance with previous reports showing that heterochromatin markers are excluded from the VRCs64. Similarly, H3K9ac was barely present in the VRCs, while it remains associated with hDNA, in line with previous observations75 (Supplementary Fig. 2d). Using quantitative analysis, we determined that the percentage of the histone-free area increased at comparable level (Fig. 1l and Supplementary Fig. 3a-c). As the chromatin got compacted, the cluster densities of H3, H3K27me3, H3K9me3, and H3K9ac increased significantly at 3 hpi, and these high densities were maintained at 8 hpi (Fig. 1m and Supplementary Fig. 3d-f). As expected, the number of H3 localizations per cluster and cluster areas significantly increased during HSV-1 infection (Supplementary Fig. 3g, j); in contrast, H3K27me3 and H3K9me3 localizations per cluster and cluster areas remained comparable with those of mock cells (Fig. 1n, o and Supplementary Fig. 3h, k). This suggests that the inspected heterochromatin marks were not globally altered by the progression of HSV-1 infection. We also found a transient significant increase of H3K9ac localizations per cluster and cluster areas at early times post-infection, likely due to an early antiviral immune response (Supplementary Fig. 3i, l). However, at late times post-infection, H3K9ac clusters were similar to those in mock cells, further suggesting that HSV-1 did not alter the active H3K9ac epigenetic marks while infection progressed. Although previous works have shown that inhibition of histone mark deposition can have profound effects on the progression of infection76,77, our results indicate that the observed chromatin compaction is not accompanied by global changes in the analyzed epigenetic chromatin markers, making their involvement in human chromatin compaction unlikely.

Sequestering of RNAP II phSer5 from HC to VRCs is associated with human genome condensation

It is known that RNAP II is sequestered from the host genome upon HSV-1 infection47,78. The viral IE protein ICP22 triggers the selective loss of the elongating RNAP II phSer279, reducing its occupancy across the gene body80. However, during HSV-1 infection, the serine 5-phosphorylated form of RNAP II (RNAP II phSer5), which serves as a marker of transcription initiation, is maintained and participates in the promoter clearance and transcription elongation of the viral genes41,81,82. Previous studies have suggested that RNAP II phSer5 and hypophosphorylated RNAP II are recruited to the VRC, while RNAP II phSer2 is either excluded or degraded via proteasomal degradation79. This mirrors the response to double-strand breaks (DSB), which also lead to Rpb1 proteasomal degradation, with a more pronounced effect on the elongating RNAP II phSer2 form83,84. Not only does the stress induced by DSB resembles HSV-1 infection, but salt stress and heat shock have been reported to decrease transcription in the same active compartments that are repressed during HSV-1 infection76.

To study the link between RNAP II hijacking and the compaction of the host genome at the nanoscale, we co-imaged RNAP II phSer5 and hDNA with STORM-PAINT (Fig. 2a). In mock A549 cells and in hFibs, RNAP II phSer5 displayed a heterogeneous pattern with clusters of different sizes associated with hDNA and was distributed across the whole nucleus, with a few localizations in the nuclear edge and in the nucleoli (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 4a). From 3 hpi onwards, as the chromatin compacted, RNAP II phSer5 was hijacked to the VRCs and gradually unloaded from the human genome. RNAP II phSer5 clusters in the VRCs became progressively bigger and denser, while the clusters on the human genome became smaller and sparser (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 4a). Of note, we observed some large aggregates of RNAP II phSer5 clusters at the interphase between viral and host compartments at late times post-infection (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 4a, arrowheads). These aggregates did not co-localize with ICP4 (Supplementary Fig. 4b) or Viral-Induced Chaperone-Enriched (VICE) domains85 (Supplementary Fig. 4c), thereby excluding they were the same domains, and further establishing RNAP II blobs as a feature of HSV-1 infection. The 3D-rendered spatial distribution of RNAP II phSer5 along with hDNA at 8 hpi clearly shows that RNAP II was sequestered out of the compacted hDNA (Supplementary Movies 1 and 2).

a (Left) Cropped representative STORM-PAINT images of EdC-AF647 labeled hDNA (magenta), immunolabeled RNAP II phSer5 (green), and their merge in mock and HSV-1 infected A549 cells at 1 hpi, 3 hpi, and 8 hpi. Yellow arrowheads indicate large aggregates of RNAP II phSer5. Scale bar: 2 µm. (Right) Zoomed-in regions are shown in yellow boxes. Scale bar: 200 nm. b Percentage of RNAP II phSer5 clusters located in VRCs over the whole nucleus in HSV-1 infected A549 cells at 3 hpi (n = 20), and 8 hpi (n = 14). Mean and SD are shown. **p < 0.01, calculated by unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t test. c–e Dot plots showing the median number of RNAP II phSer5 localizations per cluster (c), the median area per cluster (d) and the NND between clusters (e), for mock (n = 44) and HSV-1 infected A549 cells at 1 hpi (n = 32), 2 hpi (HC, n = 15; VRC, n = 8), 3 hpi (HC, n = 20; VRC, n = 20), and 8 hpi (HC, n = 14; VRC, n = 28). Mean and SD are shown. ns, p > 0.05; *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001; calculated by ordinary one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test against mock. f Representative conventional images of hDNA (magenta), conventional ICP4 (cyan), and cropped STORM images of RNAP II phSer5 (green), in mock, HSV-1 infected cells and HSV-1 n12 infected cells at 3 and 8 hpi. Scale bar: 2 µm. g Representative STORM density rendering images of hDNA in mock or HSV-1 WT and HSV-1 n12 infected A549 cells. Scale bar: 2 µm. Differences in DNA density follow the color scale bar; top: 0.00001 nm−2 (dark blue) to 0.01518 nm−2 (white). h Cumulative distribution of the Voronoi polygon densities for hDNA distribution in mock, HSV-1 and HSV-1 n12 infected cells at 3 hpi and 8 hpi. Mock (n = 24), 3 hpi WT (n = 22), 3 hpi n12 (n = 32), 8 hpi WT (n = 26), 8 hpi n12 (n = 24). Thick lines show the median and light colors, the interquartile range. ns, p > 0.05; **p < 0.001, ***p < 0.001, calculated by ordinary one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnet’s multiple comparison test against mock. i Percentage of hDNA-free area per nucleus of EdC-AF647 labeled hDNA in mock, HSV-1 WT and HSV-1 n12 infected cells at 3 hpi and 8 hpi. Mock (n = 24), 3 hpi WT (n = 22), 3 hpi n12 (n = 32), 8 hpi WT (n = 26), 8 hpi n12 (n = 24). Mean and SD represented; ns, p > 0.05; ****p < 0.0001, calculated by ordinary one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test against mock. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. p-values are indicated in Supplementary Data 1.

The percentage of RNAP II phSer5 clusters inside the VRCs at 3 hpi was 52.8%, reaching 72.0% at 8 hpi (Fig. 2b). Moreover, the number of RNAP II phSer5 localizations per cluster and its cluster area inside the VRC significantly increased from 3 hpi onwards (Fig. 2a, c, d). Interestingly, although the number of RNAP II phSer5 localizations per cluster in the HC barely changed, the cluster area decreased and the nearest neighbor distance (NND) highly increased from 3 hpi onwards, indicating a sparser organization of RNAP II in the HC (Fig. 2c–e). Overall, these results show that RNAP II phSer5 is sequestered from the HC and, from 3 hpi onwards, it aggregates inside the VRCs into larger clusters including an increased number of molecules as compared to the HC clusters.

The RNAP II sequestering along with the host DNA condensation phenocopy previous results where hDNA compaction was induced upon chemical inhibition of transcription or by RNAP II degradation22. We then compared the effects of chemical inhibition of transcription and viral replication in HSV-1 infected cell using actinomycin D (ActD) and phosphonoacetic acid (PAA), respectively (Supplementary Fig. 4d). As previously reported22, in non-infected cells, the ActD-mediated inhibition of transcription led to the compaction of hDNA (Supplementary Fig. 4e,f) and the formation of hDNA-free areas (Supplementary Fig. 4g). This is comparable to what we observed in HSV-1 infected, untreated cells. In HSV-1 infected cells, ActD treatment induced hDNA compaction (Supplementary Fig. 4e,f) and hampered the expression of the IE viral protein ICP4 (Supplementary Fig. 4e). Conversely, PAA-mediated inhibition of viral replication did not induce hDNA compaction (Supplementary Fig. 4e,f) or the formation of hDNA-free areas (Supplementary Fig. 4g). Notably, due to the inhibition of replication, the number of viral genome copies did not increase. Consequently, fewer viral genomes were available to load RNAP II. As a result, PAA treatment not only inhibits viral replication but also prevents the viral transcriptional takeover, thereby preserving transcriptional activity in the host genome. These results suggest that the HSV-1-mediated RNAP II hijacking leads to hDNA compaction, mirroring ActD mediated inhibition of transcription.

To further demonstrate the relationship between transcriptional machinery hijacking and host chromatin compaction, we used a HSV-1 mutant strain coding for a truncated, non-functional form of ICP4 (HSV-1 n12 strain)86, which cannot recruit RNAP II from host genes41. As expected, n12 mutant failed to hijack RNAP II (Fig. 2f). Moreover, infection with n12 mutant did not induce hDNA compaction (Fig. 2g, h) or the formation of hDNA-free areas (Fig. 2i), even at 8 hpi. These results suggest that hampering the sequestering of RNAP II affects the compaction of host chromatin.

As control, we confirmed that the infection with n12 in E5 cells, which express ICP4, restored the RNAP II hijacking and the hDNA compaction comparable to HSV-1 WT infection (Supplementary Fig. 4h). Our results indicate that ICP4-mediated hijacking of RNAP II induces host DNA compaction.

Next, we performed STORM-PAINT experiments to co-image RNAP II with viral DNA (vDNA). To label newly replicated HSV-1 genomes, we cultured infected cells for only 1 h with EdC before fixation at the different time points post infection (Fig. 3a). As early as 2 hpi, the sequestered RNAP II localized with vDNA in the newly formed VRCs (Fig. 3b). As the infection progressed, RNAP II was progressively entrapped in the VRCs, and associated with the vDNA. Alongside this, the synthesis of new viral genomes progressively increased (Fig. 3c).

a Scheme showing the labeling of newly replicated viral DNA. A549 cells were infected with HSV-1 for 1 h at 37 °C. At the chosen times post infection, the medium was supplemented with 40 µM EdC for 1 h before fixation. Cells were fixed and click chemistry was performed. Only the DNA replicated during this 1 h could incorporate EdC, ensuring the exclusive labeling of the vDNA synthetized at the timepoints of interest. b (Left) Cropped representative STORM-PAINT images of EdC-AF647 labeled newly replicated vDNA (magenta), immunolabeled RNAP II phSer5 (green), and their merge in mock and HSV-1 infected A549 cells. Scale bar: 2 µm. (Right). Zoomed-in regions are shown in yellow boxes. Scale bar: 200 nm. c–e Dot plots showing newly replicated vDNA cluster density (c), median number of localizations per vDNA cluster (d) and median area per vDNA cluster (e) for HSV-1 infected A549 cells at 2 hpi (n = 14), 3 hpi (n = 19), and 8 hpi (n = 28). Mean and SD are shown. ns, p > 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; calculated by ordinary one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. f, g Nearest neighbor distance (NND) distribution plot of the distance between RNAP II phSer5 and newly replicated vDNA clusters, using either active polymerase (f) or vDNA (g) as the origin, in HSV-1 infected A549 cells at 2 hpi (n = 8), 3 hpi (n = 19) and 8 hpi (n = 28). Experimental data are shown as continuous lines, random simulated data are displayed as dotted lines. The dotted line at 100 nm represents the threshold for considering that the two clusters interact. **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001; calculated by paired, two-tailed Student’s t test. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. p-values are indicated in Supplementary Data 1.

It has been reported that after capsid exit and nuclear import, prelabeled HSV-1 infecting viral genomes undergo progressive decondensation as viral transcription begins87. Here, we aimed to study the characteristics of newly replicated viral genomes at different times post infection; therefore, EdC was incorporated at the corresponding times (Fig. 3a). Newly replicated viral genomes appeared less compacted than the highly condensed hDNA and were arranged in a cluster-like distribution (Fig. 3b). The increase in vDNA cluster density at late times post-infection, when the VRC area has expanded, demonstrates a significant rise in the number of replicating viral genomes (Fig. 3c). Despite the increase in replicated genomes, the characteristics of the vDNA clusters remained relatively unaltered during the course of the infection. The vDNA clusters were formed by 10.2, 9.3, and 9.4 mean localizations per cluster at 2, 3, and 8 hpi, respectively (Fig. 3d), with cluster areas of 445.3, 408.2, and 453.1 nm2 at each respective timepoint (Fig. 3e). These results show that the vDNA organization of newly replicated vDNA was constant inside the VRCs and did not change during the course of infection, despite the increased number of viral genomes. The constant and unchanged organization of newly replicated vDNA suggests that each of the visualized clusters might correspond to a single viral genome. However, we could not exclude that this homogeneity of viral genome clusters was due to the limitation of incorporating EdC for just one hour that we carried out to label the newly synthesized genomes. Hence, we aimed to visualize all the viral genomes in the nuclei.

We then used OligoSTORM59 and a library of specific oligonucleotides to label and analyze the total viral DNA present in the nuclei (Supplementary Fig. 5a). We confirmed that despite the increase in viral molecules as infection progressed, the vDNA cluster characteristics were comparable at all timepoints (Supplementary Fig. 5b-e), suggesting that we successfully labeled clusters of single viral genomes in progressively denser VRCs.

We then investigated the topological interactions of newly replicated vDNA molecules with the RNAP II phSer5 within VRCs. We paired each RNAP II phSer5 cluster with its closest vDNA cluster, measuring the distance between both molecules (Fig. 3f). Due to the differences in the relative abundance and nature of these molecules, we additionally performed the analysis in the opposite direction, pairing the vDNA clusters with their closest RNAP II phSer5 cluster (Fig. 3g). RNAP II phSer5 clusters were significantly associated with vDNA molecules as compared to a random NND simulation (Fig. 3f). RNAP II phSer5–vDNA pairs were associated at a median distance of 79.5 nm at 8 hpi, with a maximum peak of association at 25–35 nm. We determined that 54.4% (2 hpi), 41.1% (3 hpi), and 59.7% (8 hpi) of the RNAP II phSer5 clusters were closer than 100 nm to the newly produced vDNA molecules. Moreover, as only the vDNA molecules replicated in the 1 h pre-fixation were labeled, we cannot rule out that the rest of the population of active RNAP II was also associated with non-labeled viral molecules. Similarly, newly synthesized vDNA molecules were in significantly close association with RNAP II phSer5 clusters (Fig. 3g). vDNA-RNAP II phSer5 pairs associated within distances of 40-60 nm in all three timepoints. As a result, 68.1% (2 hpi), 54.2% (3 hpi), and 66.6% (8 hpi) of the vDNA clusters were closer than 100 nm and interacted with active RNAP II phSer5 clusters. These data show that at all times post-infection, a high percentage of newly replicated vDNA molecules were associated with active RNAP II and were therefore likely to be transcriptionally active, suggesting that a high transcription activity is coupled with viral replication, consistent with previous reports88.

Sequestered RNAP II produces large and dense RNA nanodomains in VRCs

To investigate the transcriptional activity during infection, nascent RNA was co-imaged using a modified STORM technique that we previously developed23 (Fig. 4a). Nascent RNA was organized in comparable nanodomains in both mock and 1 hpi cells (Fig. 4b). At 3 hpi, the majority of RNAP II was entrapped in the VRCs along with the increase of nascent RNA; however, a substantial fraction of RNAP II still remained in the HC. At 8 hpi, nearly all the newly transcribed RNA overlapped with the active RNAP II in VRCs (Fig. 4b). Newly synthesized RNAs and hDNA did not overlap at late times post-infection (Fig. 4c). The density of the RNA nanodomains largely increased in the expanding VRCs as compared to the shrinking HC, suggesting a transcriptional switch from the HC to the VRC (Fig. 4d). Despite the reduction of total HC area, RNA nanodomain density in the HC remained unaltered, which is consistent with a global reduction in host transcription. In contrast, in the expanding VRCs, the density of RNA nanodomains triplicated at 8 hpi (Fig. 4d), suggesting increased viral transcription. Finally, the number of localizations per RNA nanodomain and their areas increased at 3 hpi, but largely increased even more at 8 hpi in VRC (Fig. 4e, f).

a Scheme showing the labeling of the nascent transcriptome. A549 cells were infected with HSV-1 for 1 h at 37 °C. Cells were incubated in medium with 1 mM EU for 30 min. Only the newly transcribed RNA is labeled. b Cropped representative STORM images of EU-AF647 labeled RNA (magenta), conventional images of immunolabeled RNAP II phSer5 (green), and their merge in mock and HSV-1 infected A549 cells. Scale bar: 2 µm. (Right). Zoom of the RNA regions inside the yellow boxes. Scale bar: 200 nm. c Conventional image of EU-AF647 labeled RNA (magenta) and DAPI labeled DNA (cyan) in A549 cells at 8 h post HSV-1 infection. Scale bar: 5 µm. d–f Dot plots showing the RNA nanodomain density (d), the median number of localizations per RNA nanodomain (e) and the median area per RNA nanodomain (f) in mock (n = 19) and HSV-1 infected A549 cells at 1 hpi (n = 18), 3 hpi (n = 18), and 8 hpi (n = 30). Mean and SD are shown. ns, p > 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001, calculated by ordinary one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test against mock. g Percentage of total TPM belonging to human (orange) or viral (blue) transcripts in mock and HSV-1 infected A549 cells at 1, 3, and 8 hpi. n = 3 for each condition. Mean and SD are shown. h–j Scatter plots showing the levels of mRNA expression of protein coding genes observed in the mock condition versus 1 (h), 3 (i) and 8 (j) hpi. Dotted red line shows the regression. k Heatmap showing the averaged z-score of genes of interest in mock and HSV-1 infected cells at 1, 3, or 8 hpi, after DESeq2 analysis. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. p-values are indicated in Supplementary Data 1.

Changes in transcriptional activity were analyzed with poly(A) RNA-seq, which showed a great reduction of human transcripts of up to 9.69% ± 0.22% of total transcription at 8 hpi (Fig. 4g). Although this reduction in host transcriptome is also influenced by the HSV-1 endonuclease virion host shutoff (vhs), it has been reported that vhs-mediated RNA decay activity degrades only around 30% of cellular mRNAs. Moreover, total RNA changes in cells infected by HSV-1 mutants, which were defective of vhs, were dominated by the global RNAP II loss54. Our data together with previous studies suggest that some of the observed changes in the host and viral poly(A) transcripts could arise from RNAP II hijacking upon HSV-1 infection. This progressive reduction in human gene expression did not equally affect all genes, as a small population of genes displayed higher transcripts per million (TPM) after infection (Fig. 4h–j). This transcriptional shutoff confirmed our super-resolution (SR) data that show that an HC-to-VRC transcription switch occurs in parallel to the sequestration of the initiating RNAP II from hDNA along with the hDNA condensation.

To further evaluate transcriptional changes upon HSV-1 infection, we performed differential gene expression analysis using DESeq289,90 (Supplementary Fig. 6a, see Methods). We found an increasing number of differentially expressed genes as the infection progressed (Supplementary Fig. 6b). This modulation of the human gene expression is not linear during the infection. We observed different clusters of DESeq2-upregulated genes at different timepoints (Supplementary Fig. 6c), which even if named as upregulated from here on, in reality, are genes less downregulated with respect to the global average (see Supplementary Fig. 6a and Methods). Some genes were upregulated only in the IE, E, or L phase, and others were upregulated in more than one of these phases (Supplementary Fig. 6d). At 1 hpi, most of the upregulated genes were related to immune response and signaling; while, at later timepoints, they were mostly involved in biosynthetic pathways, protein degradation and chromatin/transcription-related proteins, in accordance with previous studies91,92 (Supplementary Fig. 6e-g). Remarkably, in the group of upregulated genes, we found several genes encoding subunits of the RNAP II complex (Fig. 4k and Supplementary Fig. 6h).

Cohesin is partially sequestered from the HC and associates with the HSV-1 genome as the infection progresses

We previously showed that RNAP II inhibition in human cells resulted in chromatin compaction but also in the partial removal of cohesin from hDNA22. Interestingly, HSV-1 infection induces a similar phenotype. Moreover, cohesin was found in VRCs during HSV-1 infection46. However, we observed a significant downregulation of cohesin expression (Fig. 4k and Supplementary Fig. 6h). Hence, to study the hijacking of the cohesin upon HSV-1 infection at the nanoscale, we co-imaged the cohesin subunit SMC3 with hDNA or vDNA by STORM-PAINT (Fig. 5). In A549 mock cells, SMC3 strongly interacted with hDNA forming clusters of heterogeneous shapes and sizes (Fig. 5a). As the infection progressed, larger SMC3 clusters preferentially localized in VRCs where they associated with vDNA (Fig. 5b). The percentages of cohesin clusters sequestered into VRCs were 34.1% at 3 hpi, and 59.3% at 8 hpi (Fig. 5c). This sequestration is similar but less pronounced than that observed for RNAP II (Fig. 2b). Both the number of localizations per cluster and the cluster areas of SMC3 increased when cohesin was associated with vDNA at 3 and 8 hpi in the VRCs, indicating that SMC3 clusters in these compartments contained, on average, a larger number of cohesin molecules as compared to the HC clusters (Fig. 5d, e). Interestingly, while the overall SMC3 cluster area in the HC did not markedly change (Fig. 5e), the SMC3 clusters within the HC became sparser and the NND increased (Fig. 5f). Radial density analysis of cohesin with hDNA shows that hDNA is consistently more densely concentrated in the 20–160 nm range from the center of the SMC3 clusters, with a gradual density decrease, from 3 hpi onwards (Fig. 5g). This result indicates that, although cohesin is partially hijacked by HSV-1, the cohesin remaining in the HC is still loaded onto the hDNA, whose density increased due to the chromatin compaction. Similarly to A549 cell, HSV-1 infection of hFibs induced the sequestering of SMC3 to the VRCs (Supplementary Fig. 7a). Finally, to confirm whether hijacking of the transcriptional machinery affects the sequestering of SMC3 by HSV-1, we used the n12 mutant. Infection of A549 cells with n12 did not trigger SMC3 hijacking (Supplementary Fig. 7b).

a (Left) Cropped representative STORM-PAINT images of EdC-AF647 labeled hDNA (magenta), immunolabeled SMC3 (green), and their merge in mock and HSV-1 infected A549 cells. Scale bar: 2 µm. (Right). Zoomed-in regions are shown in yellow boxes. Scale bar: 200 nm. b (Left) Cropped representative nuclear STORM-PAINT images of EdC-AF647 labeled vDNA (magenta), immunolabeled SMC3 (green), and their merge in mock and HSV-1 infected A549 cells. Scale bar: 2 µm. (Right). Zoomed-in regions are shown in yellow boxes. Scale bar: 200 nm. c Percentage of SMC3 clusters located in the VRC over the whole nucleus in HSV-1 infected A549 cells at 3 hpi (n = 34), and 8 hpi (n = 14). Mean and SD are shown. ****p < 0.0001, calculated by unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t test. d–f Dot plots showing the median number of SMC3 localizations per cluster (d), median area per SMC3 cluster (e) and the NND between SMC3 clusters (f) for mock (n = 20) and HSV-1 infected A549 cells at 1 hpi (n = 19), 2 hpi (n = 13), 3 hpi (n = 50) and 8 hpi (n = 33). Mean and SD are shown. ns, p > 0.05; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ****p < 0.0001, calculated by ordinary one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test against mock. g hDNA density as a function of the distance from the center of the SMC3 clusters in mock (n = 12), and HSV-1 infected cells at 1 hpi (n = 17), 3 hpi (n = 21), and 8 hpi (n = 14). Density is measured inside rings of increasing search radii. Mean and SD are shown. h, i Nearest Neighbor Distance (NND) distribution plot of the distance between SMC3 and newly replicated vDNA clusters, taking SMC3 (h) or vDNA (i) as the origin, in 2 hpi (n = 13), 3 hpi (n = 16), and 8 hpi (n = 19) HSV-1 infected A549 cells. Experimental data displayed as continuous lines, random simulated data (control), as dotted lines. The dotted line at 100 nm represents the threshold to consider the two clusters interacting. **p < 0.01; ****p < 0.0001, calculated by paired, two-tailed Student’s t test. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. p-values are indicated in Supplementary Data 1.

To topologically characterize the inter-relation between cohesin and vDNA inside VRCs, we analyzed pair-distributions of NND between the two molecules (Fig. 5h, i). The measured pair-distributions were significantly closer than those of the random distribution simulation. Of note, SMC3 clusters were strongly associated with newly synthesized vDNA molecules at a similar distance in the three timepoints, with up to 69.8% (3 hpi) and 88.2% (8 hpi) of the SMC3 clusters associated at less than 100 nm with a newly replicated vDNA cluster (Fig. 5h). This association progressively increased during infection, with a maximum peak of 15–25 nm at 8 hpi. Surprisingly, vDNA showed a less prevalent association with cohesin (Fig. 5i). The median NND of vDNA-SMC3 pairs was 171.4 nm at 8 hpi, with a broad peak ranging from 100 to 150 nm for the three timepoints. Of the total number of newly replicated vDNA clusters identified, only 23.1% (2 hpi), 29.2% (3 hpi), or 23.8% (8 hpi) were associated closer than 100 nm to an SMC3 cluster. These results suggest that cohesin is sequestered from the HC, but that not all the viral genomes incorporate cohesin.

Interactions between human and viral genomes rewire human chromatin structure and transcription activity

We next measured chromatin structure and interactions by Hi-C in HSV-1 infected cells to study how HSV-1–induced loss of RNAP II and cohesin from hDNA affects the host chromatin 3D organization, and whether chromatin compaction is a non-random process. First, we confirmed the reproducibility of our results by Pearson Correlation Analysis (Supplementary Fig. 8a,b). Long-range interactions were maintained up to 8 hpi, despite the major condensation of the host chromatin (Fig. 6a). We found that the cis-interactions were clearly maintained in each chromosome during infection (Supplementary Fig. 8c), indicating that chromosomal territories are conserved. However, the pattern of inter-chromosomal contacts was partially lost at 8 hpi (Supplementary Fig. 8d), reflecting a partial, stochastic rearrangement of chromosome positioning at this timepoint. Similarly, cis-chromosomal contacts were blurred at 8 hpi (Supplementary Fig. 8e). Nevertheless, A/B compartments were identifiable, with little alterations from those in mock cells (Fig. 6b, Supplementary Fig. 8f). Segregation between compartments progressively increased at 1 and 3 hpi, in agreement with previous works showing strengthened compartmentalization after cohesin degradation93,94,95, but it strongly decreased at 8 hpi (Fig. 6c). Overall, this indicates that chromatin compartmentalization is mostly maintained during the infection, with no major changes due to chromatin compaction. This result is in agreement with the lack of epigenetic changes during infection (Supplementary Fig. 2, 3).

a Contact frequencies (Log10 average normalized counts) as a function of genome-wide distance for individual Hi-C replicates obtained in mock and HSV-1 infected A549 cells at 1, 3 and 8 hpi. b Left. Plots showing the eigenvector (PC1) obtained for chromosome 2 (100 kb resolution) for mock and HSV-1 infected A549 cells at 1, 3, or 8 hpi (compartments: A (blue), B (yellow)). Right. Scatterplots showing the correlation between PC1 values for each bin obtained for mock versus 1, 3, or 8 hpi. c Distribution of the compartmentalization score (Contacts within compartments/Contacts between compartments) for mock and HSV-1 infected A549 cells at 1, 3, or 8 hpi. d Plot showing the average insulation score at TAD boundaries (±300 kb) obtained for mock and HSV-1 infected cells at 1, 3, or 8 hpi. e, g Alluvial plot showing the number of created and maintained TADs (e) and loops (g) in the transitions between mock and HSV-1 infected A549 cells at 1, 3 and 8 hpi, with a tolerance of 50 kb. The yellow portion of the bars represent the TADs or loops present in mock, the blue portion of the bars represent the TADs or loops created at different times post-infection. f, h Plots showing the number of TADs (f) and loops (h) maintained, lost and new at each time point during infection, compared with mock, with a tolerance of 50 kb. Dark yellow represents maintained loops, pale yellow represents lost loops, and blue represents new loops in regards to mock. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Conversely, we found rearrangement of TAD and loop structures, even at very early times post infection (Fig. 6d–h, Supplementary Fig. 8g-l). TAD insulation and borders were maintained at early times post-infection, falling drastically at 8 hpi (Fig. 6d and Supplementary Fig. 8g). We observed a prominent rearrangement of TADs and loops from 1 hpi onwards (Fig. 6e, g). Most of the newly formed TADs and loops were unique for each time point. At 8 hpi, we saw an overall decrease of TADs and loops (Fig. 6f, h, Supplementary Fig. 8h-j) with many of them being newly formed (Fig. 6e–h). Furthermore, we found that TADs and loops became bigger at late times post-infection (Supplementary Fig. 8k, l). While both lost and newly formed TADs and loops were of similar size at 1 and 3 hpi; at 8 hpi the newly formed TADs and loops show a larger size than the lost ones (Supplementary Fig. 8m,n), resulting into an increase in the total TAD and loop sizes. The overall loss of TADs and loops at 8 hpi can be correlated with the loss of cohesin and CTCF from the HC (Fig. 5a, b, and Supplementary Fig. 8o). The internal organization and identity of TADs and loops were significantly altered, showcasing the capability of HSV-1 to dynamically rearrange the host chromatin.

We then explored the trans-interactions between the human and the viral genomes at the interphase between HC and VRCs. Strikingly, we detected interactions between the two genomes (Supplementary Table 1), which appeared to be non-random. At 1 hpi, viral genomes mainly contacted peripheral chromosomes (Supplementary Fig. 9a). This trans-interaction pattern changed at 3 and 8 hpi, at which points the viral genome preferentially interacted with gene-rich chromosomes, such as chromosome 19. Conversely, we found that the unique short region (US) of the virus was slightly enriched in contacts with the human genome, although the contact pattern was relatively homogeneous across the entire viral DNA (Supplementary Fig. 9b).

Next, we quantified the human–virus contacts and identified the preferential contacting regions. Strikingly, from 3 hpi onwards, the viral genome showed a significantly high frequency of contacts with the host A compartment, reflecting a preferential organization of the viral compartment towards active regions of the host genome (Fig. 7a). Of note, HSV-1 genomes significantly contacted gene-rich regions in both A and B compartments (Fig. 7b). Furthermore, regions containing transcriptionally upregulated human genes were found to contact the viral genome even more frequently (Fig. 7a; see also Methods). We hypothesized that the contacts of vDNA with specific genes in the A compartment could rewire key interactions in the genomic structure and, consequently, alter the transcriptional state.

a Distribution of normalized human-virus contacts for all bins (gray), bins within the B compartment (yellow), within the A compartment (dark blue), containing downregulated genes (orange), or upregulated genes (green) at each timepoint post infection. Plot shows diagram of box (25–75 percentiles) and whiskers (±1.5 x IQR) for genomic bins with outliers shown as individual points and line at median. All bins from two biological replicates were pooled. *p < 0.05; ****p < 0.0001, calculated by Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison test against whole genome. b Distribution of normalized human-virus contacts for all 100 kb bins within the A (dark blue) or B (yellow) compartment according to their gene density at 8 hpi. *p < 0.05; ****p < 0.0001, calculated by Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison test between A and B. Plot shows diagram of box (25–75 percentiles) and whiskers (5–95 percentiles) for genomic bins with outliers shown as individual points and line at median. All bins from two biological replicates were pooled. Statistical significance of the number of genes over the human–virus contacts is p < 0.0001, calculated separately for A and B compartments by Kruskal-Wallis test (not included in the plot). c, d Human genomic regions (100 kb bins) were ranked in quintiles according to the quantity of human-virus contacts at each timepoint. c Percentage of bins from A or B compartments found in each quintile. d Percentage of total (blue), downregulated (orange), and upregulated (green) genes found in each quintile. ****p < 0.0001 for chi-squared analysis of the distribution. e Overlap between human genomic regions highly contacting with HSV-1 genome and highly upregulated human genes at 8 hpi. A two-tailed hypergeometric test was used to evaluate the significance of the overlap between the two sets. f Gene ontology analysis of the highly upregulated human genes at 8 hpi that belong to human genomic regions highly contacting with HSV-1 genome. g Comparative profiling of a genomic region with newly established loops at 8 hpi and the relation between (from top to bottom) contact matrices for mock and 8 hpi, A/B compartments, human-virus interaction score, differences in RNA transcription, insulation, ATAC-seq patterns (green bars represent open chromatin regions that are consistent across all biological replicates for mock and 8 hpi HSV-1 infected cells), CTCF binding sites (colors represent the direction of the motif), and the position of genes (RefSeq). Marked genes belong to the overlapping group in (e). Blue arrowheads indicate new loops. ATAC-seq data was analyzed from deposited GEO GSE18524096, green regions represent areas of high accessibility. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. p-values are indicated in Supplementary Data 1.

To confirm this hypothesis, we divided the human genome into quintiles on the basis of the number of its contacts with vDNA. The most-interacting quintiles indeed belonged preferentially to the A compartment (Fig. 7c) and included the highest upregulated genes (Fig. 7d). We found that in the most-interacting quintile, 56% of the regions were maintained at 3 and 8 hpi (Supplementary Fig. 9c), suggesting non-random interactions between the two genomes during infection. These results indicate that the number of contacts between viral and human genomes might affect the compartmentalization and expression of human genes.

Next, we performed a motif enrichment analysis on the top 1% human-virus contacting regions (Supplementary Data 2) and observed a significant enrichment of transcription factor binding sites, which were mainly for positive regulators of RNAP II–dependent transcription (Supplementary Fig. 9d).

To further confirm these data, we crossed the list of human upregulated genes with the one of the top 1% human genes that had higher contacts with the HSV-1 genome. Of note, there was a significant overlap between the two lists, further, we found 51 upregulated top-contacting genes (Fig. 7e; Supplementary Table 2) that encode factors controlling transcription, translation, and RNA metabolism of the virus (Fig. 7f). We then analyzed whether loops were rewired in some of these upregulated high-contacting genes. Strikingly, in the genomic region including genes such as nuclear RNA export factor 1 (NXF1), testis expressed 54 (TEX54), and WD repeat domain 74 (WDR74) (from the 51 above-mentioned set), we found a clear correlation between compartmentalization, human–virus contacts, transcription activity, insulation score, chromatin accessibility, and CTCF binding sites (Fig. 7g). We analyzed ATAC-seq data96 and did not find any significant change in chromatin accessibility, further supporting the idea that chromatin remodeling is not caused by nucleosome repositioning (Fig. 7g). Despite the global loss of TADs and loops at 8 hpi (Supplementary Fig. 8h,i), we observed an increased insulation score around these genes as compared to the same genes in the mock condition, in correlation with a high frequency of human–virus contacts and a maintained transcriptional activity (Fig. 7g). Moreover, newly formed loops were clearly generated in the HSV-1 infected cells at 8 hpi (Fig. 7g, arrowheads, Fig. 9, Supplementary Fig. 9e). In conclusion, these data suggest that the HSV-1 trans-interaction with host DNA actively rewires the human genome.

TOP1 inhibition prevents progression of HSV-1 infection

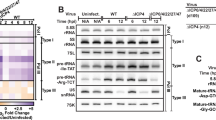

Supercoiling relief by topoisomerases is essential for transcription, and perturbing topoisomerase activity leads to a drastic condensation of the genome22, which resembles the compaction observed during HSV-1 infection. Interestingly, Topoisomerase 1 (TOP1) expression was upregulated during infection, while that of TOP2A and TOP2B was downregulated (Fig. 4k and Supplementary Fig. 6h). Hence, we studied the role of TOP1 in HSV-1 infection and the consequences of its inhibition using β-lapachone (β-lap), a TOP1 inhibitor, in mock-infected and HSV-1 infected cells (Supplementary Fig. 10a-d). Our imaging results showed that TOP1 was sequestered to VRCs and overlapped with ICP4 (an IE virus protein) at 3 and 8 hpi in infected cells (Fig. 8a), in accordance with previous results65,97. This hijacking is similar to that observed for RNAP II (Figs. 2a and 8b). To inhibit TOP1, we treated cells with β-lap before HSV-1 infection up to 3 hpi; we then fixed the cells (3 hpi–β-lap_pre) or allowed them to recover by removing β-lap at 3 hpi and fixing the cells at 8 hpi (8 hpi–β-lap_pre) (Supplementary Fig. 10b,c). After TOP1 inhibition, we observed a complete absence of ICP4 in 3 hpi–β-lap_pre (Fig. 8c, d, middle panels). Notably, ICP4 was also not recovered in 8 hpi–β-lap_pre cells (Fig. 8c, d, bottom panels). Moreover, using qPCR, we demonstrated that inhibition of TOP1 before infection prevents the expression of HSV-1 IE, E, and L genes (Supplementary Fig. 10e). TOP1 inhibition also hindered viral replication, as the relative viral genome copies did not increase at different times post-infection (Supplementary Fig. 10f). We further confirmed that the observed inhibition of transcription was not due to a general cytotoxic effect of β-lap, as the concentration and treatment duration used in our experiments did not affect cell viability (Supplementary Fig. 10g).

a-d, l and m Representative conventional images of white top hat-filtered hDNA (magenta), conventional ICP4 (cyan) and cropped STORM images of TOP1 (green), in mock and HSV-1 infected cells untreated (a) or treated with β-lap before (c) or during infection (l). Representative conventional images of hDNA (magenta), ICP4 (cyan) and cropped STORM images of RNAP II phSer5 (green), in mock and HSV-1 infected cells untreated (b) or treated with β-lap before (d) or during infection (m). Yellow dotted lines delimit the location of VRCs. Scale bar: 2 µm. e, f Percentage of TOP1 (e) and RNAP II phSer5 (f) clusters co-localizing with hDNA regions over the whole nucleus in mock or HSV-1 infected A549 cells treated or untreated with β-lap. For TOP1: mock (n = 11), mock β-lap treated (n = 9), 3 hpi (n = 7), 3 hpi–β-lap_pre (n = 12), 8 hpi (n = 10), 8 hpi–β-lap_pre (n = 16), 8 hpi–β-lap_post (n = 14). For RNAP II: mock (n = 7), mock β-lap treated (n = 7), 3 hpi (n = 7), 3 hpi–β-lap_pre (n = 13), 8 hpi (n = 11), 8 hpi–β-lap_pre (n = 16), 8 hpi–β-lap_post (n = 16). Mean and SD represented; Statistical significance compared to mock untreated is p < 0.0001 for all conditions (not included in the plots). Statistical significance compared to mock β-lap treated is shown in the graph (green): ns, p > 0.05; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001, calculated by ordinary one-way ANOVA test followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. g Percentage of hDNA-free areas per nucleus quantified from SR images of mock and HSV-1 infected cells, untreated or treated with β-lap. Mock (n = 4), mock β-lap treated (n = 18), 3 hpi (n = 11), 3 hpi–β-lap_pre (n = 15), 8 hpi (n = 8), 8 hpi–β-lap_pre (n = 17), 8 hpi–β-lap_post (n = 7). Mean and SD are shown; statistical significance compared to mock untreated is p < 0.0001 for all conditions (not included in the plots). Statistical significance compared to mock β-lap treated is shown in the graph (green): ns, p > 0.05; **p < 0.01; ****p < 0.0001, calculated by ordinary one-way ANOVA test followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. h–k Representative STORM density rendering images of hDNA in mock (h) or HSV-1 infected (i–k) A549 cells treated or not with β-lap. Top: whole nucleus. Scale bar: 2 µm. Bottom: Zoomed images of the regions inside the yellow boxes. Scale bar: 200 nm. DNA density follows the color scale bar; top: 0.00001 nm−2 (dark blue) to 0.01640 nm−2 (white); bottom: 0.00001 nm−2 (dark blue) to 0.01978 nm−2 (white)). Source data are provided as a Source Data file. p-values are indicated in Supplementary Data 1.

Importantly, TOP1 inhibition induced a severe loss of both TOP1 and RNAP II from high-density host chromatin regions, both in mock (Fig. 8c, d, upper panels) and HSV-1 infected cells (Fig. 8c, d, middle and lower panels). This resembled the loss of TOP1 and RNAP II that occurred upon HSV-1 infection (Fig. 8a, b, middle and lower panels). The quantified numbers of TOP1 and RNAP II clusters on hDNA were drastically reduced and similar between β-lap treated cells, both in HSV-1 infected and non-infected cells (Fig. 8e, f).

We then asked whether TOP1 is a key determinant for chromatin compaction mediated by HSV-1. We found that 3 hpi–β-lap_pre and 8 hpi–β-lap_pre cells displayed levels of hDNA-free nuclear space (Fig. 8g) and hDNA compaction (Fig. 8i, j) comparable to mock cells treated with β-lap (Fig. 8h, compare zoomed-in panels). Interestingly, the level of hDNA compaction in infected cells was similar to the β-lap treated cells (Fig. 8h–j, zoomed-in panels).

Finally, we analyzed the effects of inhibiting TOP1 during infection. After infection, we treated the cells with β-lap from 3 hpi until 8 hpi, at which point cells were fixed (8 hpi–β-lap_post) (Supplementary Fig. 10d). We found that hDNA compaction and hDNA-free nuclear space (Fig. 8g) were comparable in 8 hpi–β-lap_post (Fig. 8k) and untreated infected cells at 3 hpi (Fig. 8i). Moreover, the expression of ICP4 and the nuclear distributions of both RNAP II and TOP1 were comparable to untreated, infected cells at 3 hpi (Fig. 8l, m as compared to Fig. 8a, b, middle panels). These data revealed that TOP1 inhibition stalls the infection progression, thus suggesting that TOP1 is essential also for late stages of HSV-1 infection.

Overall, our data indicate that the HSV-1–mediated hijacking of both RNAP II phSer5 and TOP1 drives a global reorganization of the human genome. Moreover, our data demonstrate the key role of transcription activity as a remodeler of genome organization.

Discussion

The advent of single-molecule localization imaging approaches along with chromosome conformation capture technologies have made it possible to study how the structural organization of the genome in the 3D nuclear space controls gene function3,5,98,99,100. In parallel, transcriptional activity is emerging as a key determinant for shaping 3D genome structure22,23. Viral infection provides an ideal model in which two different genomes co-exist and can interact in trans, thereby revealing yet-unknown mechanisms that control genome structure and how perturbation of genome folding and topology affect genome function.

Soon after HSV-1 infection, the human genome undergoes a massive compaction30,101, which in this study we analyzed at nanoscale resolution and in single cells. Despite the strong compaction of the host chromatin, H3K27me3, H3K9me3, and H3K9ac did not show global changes in infected cells as compared to non-infected ones, while the VRCs appear to be devoid of these histones. These results are also in agreement with previous ATAC-seq results showing no dramatic alteration of the positioning of nucleosomes around host TSS after infection40. Moreover, the lack in global alterations of H3K27me3 does not contradict a previous report suggesting that specific localized rearrangements of this epigenetic mark, together with macroH2A, are necessary for viral capsid egress76. Our results are also in accordance with previous work reporting maintenance of host genome accessibility41 and the relatively low abundance or absence of histones on viral genomes65. The chromatinization of viral genomes is a debated topic28,34,36,38,41,65,102,103. While some previous studies report co-immunoprecipitation of HSV-1 genomes with histones bearing active transcription marks33,104,105,106 or histone variants107; others document a largely nucleosome-free state of the viral genome, as shown by ATAC-seq analyses40,41 and micrococcal nuclease treatments36,108,109,110,111,112. With SR microscopy we can obtain single-cell spatial information on the localization of histones, in contrast to genomic approaches such as ChIP-seq, which provide only population-level information. Additionally, the differences in genome length and replicating activity of the HSV-1 and the host genome makes normalizing ChIPseq data from infected cells challenging. Using SR microscopy, we clearly showed that H3 was enriched in the HC and was mostly absent in the VRC, and therefore, could not be associated with newly replicated viral genomes in the VRC. Our results offer further evidence of the lack of chromatinization of the newly replicated viral genomes in the VRCs.

While the host genome maintains its association with histones during infection, it partially loses other interacting proteins. HSV-1 sequesters the cellular transcription machinery to the VRC40,41, leading to a major decrease in the binding of RNAP II to host promoters41,45,47,82 and to the hijacking of cohesin and TOP1 to viral genomes46,65,113. In light of our previous results showing that inhibition of RNAP II or TOP1 results in chromatin compaction and partial loss of cohesin22, we propose that the major structural reorganization of host chromatin following HSV-1 infection is induced by the redistribution of RNAP II and TOP1 within the nucleus. Indeed, we found a correlation between the progressive host chromatin condensation and the progressive loss of RNAP II, TOP1, and cohesin from the host genome. These coordinated events suggest that the host chromatin compaction might be dependent on the hijacking of the transcription machinery to the VRC. This observation is confirmed by the lack of host chromatin compaction and of RNAP II hijacking to the VRC upon n12 mutant strain infection. Additionally, we showed that inhibition of TOP1 in non-infected cells led to RNAP II detachment from the hDNA and host chromatin compaction, which parallels what we observed in infected cells. Taken together, these findings link the sequestration of transcriptional machinery away from the host genome to its compaction, suggesting a possible molecular mechanism for chromatin compaction which strongly implicates active transcription as a key determinant in the spatial organization of the chromatin structure.

Surprisingly, we also found that the compaction of the host genome is an organized process. The consistent identity of TADs and loops for each time post-infection in the different biological replicates indicates that chromatin condenses in an organized manner, showcasing a non-random and dynamic remodeling of the host chromatin by HSV-1. Additionally, at 8 hpi, we found compartmentalization to be maintained despite the hDNA condensation, and cohesin loss, in agreement with earlier works showing that A/B compartments are preserved when cohesin is degraded93,114. Interestingly, our results point towards an uncoupling of DNA physical compaction and chromatin compartmentalization. This maintenance of A/B compartments differs from what has been described for host genomes upon infection by different types of RNA viruses. The influenza A RNA virus (IAV), which replicates in the nucleus, induces a pervasive weakening of the A compartment115, while the SARS-CoV-2 RNA virus, which replicates in the cytoplasm, induces an A-to-B compartment switch116. This shows that HSV-1 uses a completely different strategy to exploit the host genome.

As the host genome undergoes a massive compaction and a general transcription shutoff, the highly transcriptionally active VRCs expand in the nuclear space during lytic infection. By using SR microscopy, we discovered that the newly replicated HSV-1 genomes form clusters of a constant size that are homogeneously distributed within VRCs and do not colocalize with histone H3, which further proves that newly replicated viral genomes barely interact with histones.

Previous studies have shown that prelabeled HSV-1EdC infecting viral genomes associate with RNAP II and components of the antiviral protein promyelocytic leukemia protein nuclear bodies (PML NBs) as early as 1 hpi113,117. However, by 2 hpi, PML NBs are no longer detectable113, and input viral genomes begin to associate with ICP465,113. In contrast, our work focused on investigating the association of newly synthesized viral genomes, rather than input viral genomes, with RNAP II and cohesin. The association of RNAP II and cohesin with viral genomes has been previously reported from bulk analysis41,42,46,118, but their nanometric distribution inside the VRCs and their association with viral genomes at the single-cell level remained unresolved. Using SR microscopy, we studied the association of each cluster of RNAP II and cohesin with viral genomes, expanding the findings of previous works40,65,119. Using SR imaging, we discovered that while clusters of RNAP II and newly replicated vDNA associated symmetrically, vDNA associated with cohesin non-symmetrically. Indeed, although most of the cohesin was highly associated with vDNA, most of the vDNAs appeared to be cohesin-free, in other words, the newly replicated viral genomes associated frequently with RNAP II but not with cohesin. These results suggest that RNAP II binding to the newly replicated viral genome is not promoted by cohesin, differing from previous observations46. Even though cohesin is known to play an important role in maintaining the latent episomal states of HSV-1, Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated virus (KSHV), and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)120,121, its role in transcription during the lytic cycle remains still elusive. Notwithstanding, the cohesin hijacking to the VRCs suggests that cohesin has a structural regulatory function on viral genomes, especially at later time points post-infection.

Strikingly, we also found that the HSV-1 viral genome trans-interacts with specific human chromosomal domains non-randomly (Fig. 9). Although host and viral genomes segregate to different regions of the nucleus, proteins can diffuse across the HC and VRC boundaries40. This indicates that these two compartments are not isolated, and that the genomes could interact at the interphase between the HC and the VRC. Contacts at this interphase might be permissive for specific regions of the host genome to access nuclear areas enriched in RNAP II, which might be related with the RNAP II blobs we observed at the VRC–HC interphase.

During HSV-1 infection, RNAP II (light green), TOP1 (yellow) and cohesin (green rings) are hijacked to the VRCs. As a result, a host-to-virus transcriptional switch occurs, and the host chromatin becomes highly compacted and transcriptionally repressed. At the same time, HSV-1 is found to contact specific gene-rich regions of the host genome, forming new loops. These regions are transcriptionally active, and include genes involved in infection progression.

Virus–host contacts have been reported at several days post-infection for DNA viruses, such as EBV122,123, hepatitis B virus, and adenovirus 5124. Here, we identified contacting regions between HSV-1 and host genomes during lytic infection as early as 3 hpi. We found that viral genomes preferentially contacted genomic regions containing both high gene density and active transcription motifs, suggesting that transcriptional activity might be related to genomic trans-contacts. It remains to be determined whether these contacts directly regulate host gene expression, or whether HSV-1 preferentially contacts transcriptionally active regions. In particular, the strongest correlation was between highly trans-contacting regions and regions containing upregulated genes. In these contacting regions, new loops were created that embrace genes involved in translation, gene expression, and metabolic processes, which are needed for infection progression, suggesting that new short-range contacts are formed. Indeed, while most human genes are downregulated during infection, HSV-1 likely actively rewires specific loops to activate host genes that are advantageous for infection. However, this trans-interacting rewiring of the host genome differs from the epigenetic rewiring observed for the herpesvirus EBV in gastric cells122.

Finally, we observed that TOP1 is essential for HSV-1 infection, as inhibition of TOP1 completely blocks the transcription of IE, E, and L genes, hampered the formation of VRCs, and critically hinders HSV-1 replication. Previous work has reported that the activity of TOP1 is needed for the replication of HSV-2125, KHSV126, and EBV127. However, we observed here that TOP1 was already essential for HSV-1 IE transcription prior to the beginning of replication. Of note, we found that infection progression was blocked early in infection, opening the possibility of using TOP1 inhibitors to treat HSV-1 infection, which is a worldwide health problem128,129,130,131. Thus, inhibition of topoisomerases could be a promising antiviral strategy.

Methods

Cell culture

A549 cells (Lung Carcinoma, American Type Culture Collection, ATCC CRL-185) were cultured in F-12K (Kaighn’s) medium (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, #21127022) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #10270106), and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #15140122). Cells were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. The A549 cell line was selected as an epithelial cell model to study the lytic cycle of HSV-1 infection as in previous studies132,133,134.

Human BJ fibroblasts (hFibs) (skin fibroblast, American Type Culture Collection, ATCC CRL-2522) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, high glucose, GlutaMAX™ Supplement, Thermo Fisher Scientific, #10566016) supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin–streptomycin, and 1% non-essential amino acids (Gibco, #11140050). Cells were grown in a humidified hypoxic incubator at 37 °C, 5% CO2, and 5% O2.

HeLa cells (human cervix adenocarcinoma, Maria Pia Cosma lab), Vero cells (African green monkey, kidney epithelial, ATCC CCL-81) and E5 cells (Vero-derived cell line which expresses ICP4, kindly donated by Prof. Neal DeLuca) were cultured at 37 °C in 5% CO2 in DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS, and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #15140122). All cell cultures were routinely tested for mycoplasma contamination by PCR (EZ-PCR™ mycoplasma detection kit, Biological Industries, #20-700-20).

Virus strain

HSV-1 (KOS strain, JQ673480.1), a generous gift from M. A. Sanz and L. Carrasco (Centro de Biologia Molecular Severo Ochoa (CBMSO), Spain), was grown in Vero cells cultured in DMEM supplemented with 2% FBS. HSV-1 n12 mutant strain that encodes a truncated, non-functional form of ICP4 was a kind gift from Prof. Neal DeLuca (University of Pittsburgh, U.S.A.). The strain was grown in E5 cells cultured in DMEM supplemented with 2% FBS. Virus preparations were titrated by plaque assay.

Sample preparation and virus infection

For imaging purposes, A549, hFib or E5 cells were plated in borosilicate glass bottom 8-well chambers (μSlide Ibidi, #80827) at a confluency of 20,000–30,000 cells/cm2.

For human DNA labeling experiments, A549, hFib or E5 cells were cultured with media supplemented with 5 µM 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxycytidine (EdC) (Sigma-Aldrich, #T511307) for 64 h prior to HSV-1 infection. After media wash, cells were infected with HSV-1 WT or HSV-1 n12 at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 3 for 1 h at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2, then, the medium was removed and replaced by fresh DMEM medium (supplemented with 2% FBS).

For viral DNA labeling experiments, infected cells were cultured with media supplemented with 40 µM EdC for 1 h prior to fixation.

For RNA labeling experiments, infected cells were cultured with media supplemented with 1 mM 5-ethynyl-uridine (EU) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #E10345) for 30 min prior to fixation. HSV-1 infection was performed as described above.

At the indicated times post-infection, cells were fixed with 4% PFA (Alfa Aesar, #43368) for 15 min at room temperature and then, rinsed with PBS three times for 5 min each. Then, cells were permeabilized with 0.4% Triton X-100 (Acros Organics, #327371000) in PBS for 15 min and rinsed with PBS three times for 5 min each. Click chemistry reaction was performed by incubating cells for 30 min protected from light at RT in click chemistry buffer (150 mM HEPES pH 8.2, 50 mM aminoguanidine hydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich, #396494), 100 mM ascorbic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, #A92902), 1 mM CuSO4 (Sigma-Aldrich, #C1297), 2% glucose (Sigma-Aldrich, #G8270), 0.1% Glox solution (described in STORM imaging) and 10 μM AlexaFluor647 (AF647) azide (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #A10277)). Afterwards, samples were washed three times with fresh PBS. Then, we directly proceeded with STORM imaging for single color DNA or RNA imaging experiments (see section STORM, STORM-PAINT, and OligoSTORM imaging) or we proceeded with immunolabelling for imaging experiments combining DNA or RNA with protein (see Immunolabelling for SMLM and STORM, STORM-PAINT, and OligoSTORM imaging).

Inhibition of Topoisomerase I, transcription, and viral replication

For topoisomerase 1 (TOP1) inhibition, cells were treated with β-lapachone (β-lap, Sigma, #L2037) at 10 µM in DMSO. Mock-infected cells were treated for 5 h prior to fixation. HSV-1 infected cells were treated before and during early phases of infection (pre) or at later times, after the beginning of infection (post). For pre-treatment, cells were treated 1 h before infection, during virus adhesion (1 h), and the first 3 h during the infection course. At 3 hpi, cells were either fixed (3 hpi β-lap_pre) or medium with β-lap was replaced with fresh medium up to 8 hpi, when cells were fixed (8 hpi β-lap_pre). For post-treatment, infected cells were treated with β-lap from 3 hpi to 8 hpi, then samples were fixed (8 hpi β-lap_post).

For assessing β-lapachone cytotoxicity, A549 cells were seeded overnight in 96 well plates. At 5 h and 24 h before the assay, β-lapachone was added to the media at different concentrations per well. MTT cell viability assay kit (Invitrogen, #V13154) was used according to manufactures instructions. Absorbance values at 570 nm were measured using a colorimetric plate reader (ThermoFisher, Multiskan SkyHigh Microplate Spectophotometer) and their values were compared with that of untreated cells.

Inhibition of transcription experiments were performed as described22,135. Briefly, A549 cells were treated with 4 µM actinomycin D (ActD, #A9415, Sigma) in DMSO. Mock-infected cells were treated for 5 h prior to fixation. HSV-1 infected cells were treated before and during early phases of infection until 3 hpi, when they were fixed.

Inhibition of viral replication experiments were performed based on previous literature136. Cells were treated with 350 μg/mL phosphonoacetic acid (PAA, #284270, Sigma) in DMSO. Mock-infected cells were treated for 3 h prior to fixation. HSV-1 infected cells were treated after viral adsorption.

Immunolabelling for SMLM imaging