Abstract

Gaseous phytohormone ethylene regulates various aspects of plant development. Ethylene is perceived by ER membrane-localized receptors, which are inactivated upon binding with ethylene molecules, thereby initiating ethylene signal transduction. Here, we report that a novel E3 ligase RING finger for Ethylene receptor Degradation (RED) and its E2 partner UBC32 ubiquitinate ethylene-bound receptors for degradation through an ER associated degradation (ERAD) pathway in both Rosa hybrida and Solanum lycopersicum. The depletion of RED or UBC32 leads to hypersensitivity to ethylene, which is manifested as premature leaf abscission and petal shedding in roses, as well as the dwarf plants and accelerated fruit ripening in tomatoes. Disruption of the conserved ethylene binding site of receptors prevents RED-mediated degradation of the receptors. Our study discovers an ERAD branch that facilitates the ethylene-induced degradation of receptors, and provides insights into how the plant’s response to ethylene can be controlled by modulating the turnover of ethylene receptors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ethylene regulates various aspects of plant growth and development, including seed germination, seedling growth, organ abscission, leaf and flower senescence, fruit ripening and response to multiple abiotic and biotic stimuli1. Ethylene receptors are localized in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane and act as negative regulators. In Arabidopsis thaliana, ethylene receptors are divided into two subfamilies due to their structural features2,3,4,5,6,7: subfamily I proteins (ETR1 and ERS1) containing three transmembrane domains and an intact histidine kinase domain, and subfamily II receptors (ETR2, ERS2 and EIN4) with four transmembrane domains and a degenerate histidine kinase domain8,9.

The receptors act as negative regulators in the ethylene-signaling pathway. In the absence of ethylene, the receptors activate CTR1, a Ser/Thr kinase that suppresses the ethylene response. Upon binding ethylene, the receptors undergo conformational changes5,10,11 that prevent the activation of CTR1, consequently releasing the suppression on the downstream signaling components. Given that the half-life for the dissociation of ethylene from the receptors typically ranges from 10 to 12 h12,13, it is critical for the ethylene-bound receptors to be replaced by active receptors in a timely manner. The process of protein proteolysis has long been suggested as an effective pathway for preventing the accumulation of ethylene-bound receptors and preserving the capacity for ethylene perception over extended periods14,15. However, the precise mechanism underlying this process remains unknown.

In this study, we have discovered that the degradation of ethylene receptors is regulated by the endoplasmic reticulum associated degradation (ERAD) system. Through analysis in rose and tomato plants, it was found that these receptors are targeted for degradation by a specific module comprised of a novel ER-based RING finger E3 ligase (RED) and a conserved ERAD E2 conjugating enzyme (UBC32). This degradation process is dependent on the ethylene binding because mutation of ethylene binding site abolishes the UBC32-RED module-mediated degradation of ethylene receptors. Knockdown either UBC32 or RED results in a hypersensitive response to ethylene. Taken together, these findings elucidate the pathway by which subfamily II ethylene receptors are degraded, and show how this process affects the plant’s response to ethylene.

Results

Ethylene induces degradation of ethylene receptor RhETR3 in roses

Ethylene plays a crucial role in plant development, particularly in facilitating specific biological processes. For example, it is essential for flower opening and senescence/abscission in ethylene-sensitive flowers such as roses and orchids16,17,18,19,20,21, as well as for the ripening of climacteric fruits like tomatoes and bananas22, where a rapid and substantial increase in ethylene production is required. In rose, ethylene significantly accelerates flower opening and senescence/abscission (Fig. 1a)23,24, and the ethylene receptor RhETR3 has been reported to be responsible for these processes25,26. Expression of RhETR3 increases as flower opening and senescence27,28, and is highly induced by ethylene in petals (Fig. 1b).

a Effects of ethylene on flower opening and petal abscission. Rose flowers at stage 2 were treated with 10 ppm ethylene for 0, 12, 24, 36 or 48 h. Ten flowers were used for each treatment. Scale bar, 2 cm. b The expression of RhETR3 is induced by ethylene. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of RhETR3 expression in stage 2 rose flowers treated with 10 ppm ethylene for 3 h. RhUBI was used as an internal control. The mean values ± SD are shown from 3 biological replicates. Asterisks indicate significant differences (two-sided Student’s t-test, ****P < 0.0001). c RhETR3 protein levels in rose petals as the flowers age. Petal proteins were probed with anti-RhETR3 antibody. Coomassie brilliant blue (CBB) staining was used to show protein loading (bottom panel). 2, 3, and 5, the flower opening stages. Stage 2, opened buds; Stage 3, partially opened flowers; Stage 5, fully opened flowers. Scale bar, 1 cm. d Ethylene promotes the degradation of RhETR3 proteins. Rose flowers at stage 2 were treated with 10 ppm ethylene for 3 h. RhETR3 protein was visualized using an anti-RhETR3 antibody. CBB staining was used to show protein loading (bottom panel). e Degradation pattern of the RhETR3 proteins. Nicotiana benthamiana leaves expressing RhETR3-Flag were infiltrated with were infiltrated with DMSO control, 50 µM MG132, or 75 µM CHX for 6 h prior to a 3-h treatment with or without 100 ppm ethylene. Total proteins were isolated for Western blot analysis. ACTIN protein was used as a loading control. For (a–e) 3 independent experiments were performed, representative results are shown. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The rose genome encodes six putative ethylene receptors: RhETR1, RhETR3, RhERS1, RhERS1X2, RhERS2, and RhEIN429. To determine the accumulation pattern of RhETR3 proteins, we raised a polyclonal antibody against a RhETR3-sepcific region (509–729 aa) based on sequence alignment and confirmed the antibody’s specificity for RhETR3 using Western blot and LC-MS analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1a–d). The protein level of RhETR3 decreased as flower opening (Fig. 1c). Exposure to ethylene decreased the RhETR3 protein level, while the proteasome inhibitor MG132 blocked the ethylene-induced degradation of RhETR3 proteins (Fig. 1e and Supplementary Fig. 1e). In the presence of ethylene, RhETR3 protein levels were higher in DMSO control than in Cycloheximide (CHX, a translation inhibitor) treatment but lower than in CHX + MG132 treatment (Fig. 1e). Given that ethylene also induces RhETR3 expression, we conclude that ethylene simultaneously promotes de novo RhETR3 protein synthesis and RhETR3 degradation via the ubiquitin-26S proteasome pathway.

The ethylene sensitivity of roses is controlled by two interactors of RhETR3, RhRED, and RhUBC32

To investigate the potential mechanism underlying the ethylene-induced turnover of RhETR3, we conducted a screening of a rose petal cDNA library to identify interaction proteins that contribute to the degradation of RhETR3 using a dual split-ubiquitin membrane yeast two-hybrid (MYTH) approach (Supplementary Data 1). We identified 58 proteins potentially interacting with RhETR3, including 4 proteins related to protein degradation pathway (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Data 1). Florescence co-localization demonstrated that subcellular localization of RhETR3 was overlapped with two of these candidates, including a ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (RchiOBHm_Chr4g0424811) and a putative RING (Really Interesting New Gene) E3 ligase (RchiOBHm_Chr4g0439841) (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Figs. 2, 3). By combining MYTH and Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation (BiFC), we confirmed that RhETR3 physically interacts with protein products of both RchiOBHm_Chr4g0424811 and RchiOBHm_Chr4g0439841 (Fig. 2c, d). According to the phylogenetic analysis, RchiOBHm_Chr4g0424811 and RchiOBHm_Chr4g0439841 were named after RhUBC32 and RhRED (RING finger for Ethylene receptor Degradation), respectively (Supplementary Figs. 2a, 3a).

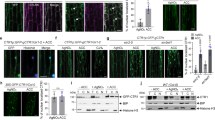

a Putative RhETR3 interactors involved in the ubiquitin-26S proteasome degradation pathway. The listed proteins were identified through a split-ubiquitin yeast two-hybrid screen. b RchiOBHm_Chr4g042481-GFP and RchiOBHm_Chr4g0439841-GFP were Co-located with RhETR3-mCherry in transiently expressed N. benthamiana leaves, respectively. ER-mCherry is an endoplasmic reticulum (ER) localization marker. Scale bar, 50 μm. 3 independent experiments were performed, representative results are shown. c Split-ubiquitin Y2H (MYTH) assay for interaction of RhETR3 and RchiOBHm_Chr4g042481, RchiOBHm_Chr4g0439841. Top, schematic representation of RhETR3 and two truncated fragments. Bottom, MYTH assay for RhETR3 and RchiOBHm_Chr4g042481, RchiOBHm_Chr4g0439841. pPR3N with pBT3-STE-RhETR3 was used as a negative control. d BiFC analysis of RhETR3 and RchiOBHm_Chr4g042481, RchiOBHm_Chr4g0439841 in tobacco leaves. The full-length coding sequence of RhETR3 was cloned into pSPYNE (R) and the full-length coding sequence of RchiOBHm_Chr4g042481, RchiOBHm_Chr4g0439841 was inserted into pSPYCE (M). RhETR3-nYFP with cYFP was used as a negative control. Scale bar, 50 μm. 3 independent experiments were performed, representative results are shown. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In order to explore the function of RhUBC32 and RhRED, we first analyzed their expression pattern in various tissues. RhUBC32 and RhRED showed higher expression levels in petals and leaves than in roots and stems (Supplementary Figs. 2c, 3d). Expression of both genes increased in petals during flower opening and was elevated after 6, 12, and 24 h of ethylene treatment (Fig. 3a). To confirm whether RhUBC32 and RhRED influence the sensitivity of rose flowers to ethylene, we generated RhUBC32-RNAi and RhRED-RNAi lines (Fig. 3b, c). Under normal conditions, both RhUBC32-RNAi and RhRED-RNAi lines displayed noticeable decreases in plant height and premature leaf abscission, particularly in RhUBC32-RNAi lines, in comparison to the wild-type (WT) plants (Fig. 3c, d). When exposed to exogenous ethylene, the RhUBC32-RNAi and RhRED-RNAi lines showed enhanced petal abscission, with the former displaying particularly pronounced effects (Fig. 3e). Expression of the ethylene-induced genes RhPR10.1 and RhHB6 was significantly higher in RhUBC32-RNAi and RhRED-RNAi lines than in the WT, and this difference was further enhanced by ethylene treatment (Fig. 3f). These results suggested that the silencing of either RhUBC32 or RhRED in roses leads to a hypersensitive response to ethylene.

a Expression pattern of RhUBC32 and RhRED in rose petals as flowers aged (top) and in response to ethylene. The stage 2 flowers were treated with 10 ppm ethylene for 3, 6, 12, and 24 h. RhUBI was used as an internal control. The mean values ± SD are shown from three biological replicates. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05, one-way ANVOVA analysis with Tukey’s HSD test). b Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of RhUBC32 and RhRED expression in petals of WT, RhUBC32-RNAi (top), and RhRED-RNAi (bottom) lines at stage 5. RhUBI was used as an internal control. The mean values ± SD are shown from three biological replicates. c Phenotypes of RhUBC32-RNAi and RhRED-RNAi plants. Photographs were taken of plants 6 weeks after transplant. Scale bar, 2 cm. d Statistical analysis of the plant height in (c). Data are presented as mean values ± SD, n = 5 (WT of left), n = 4 (RhUBC32-RNAi#18), n = 4 (RhUBC32-RNAi#22), n = 9 (WT of right), n = 7 (RhRED-RNAi#3), n = 7 (RhRED-RNAi#5). e Morphology of RhUBC32, RhRED silenced rose flowers in response to ethylene. Flowers in stage 2 (opened buds) were treated with 10 ppm ethylene for 24 h. Representative images of three independent experiments are shown. Scale bar, 2 cm. For each experiment, at least 15 WT control plants and 15 RhUBC32-RNAi, RhRED-RNAi plants were analyzed (n ≥ 15). Representative results from one experiment are shown. f Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of RhPR10.1 and RhHB6 in petals of WT and RhUBC32-RNAi, RhRED-RNAi lines. The flowers at stage 2 were treated with 0, 10 ppm ethylene for 3 h. RhUBI was used as an internal control. The mean values ± SD are shown from three biological replicates. For (b), (d), and (f), asterisks indicate statistically significant differences compared to WT (two-sided Student’s t-test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001). Source data is provided as a Source Data file.

RhUBC32 functions as an E2 enzyme, while RhRED acts as an E3 ligase

In Arabidopsis, UBC32, the homolog of RhUBC32, shares homology with Ubc6p, a known ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme in yeast, and UBE2J1, an equivalent enzyme found in mammals30,31. Previously, UBC32 was reported to play a conserved and indispensable role in the ERAD pathway in plants by facilitating the degradation of misfolded proteins that accumulate in the ER, such as the mutated forms of the brassinosteroid receptor bri1-5 and bri1-932. To confirm whether RhUBC32 is a functional ERAD ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme, we analyzed its conserved domains using EMBL. We discovered a ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme catalytic domain (UBCc domain) with a conserved active Cys located at position 93 in the N-terminus of RhUBC32, and a transmembrane domain in the C-terminus of the protein (Supplementary Fig. 2b). We then conducted an in vitro thioester formation assay and observed a linkage between the recombinant RhUBC32-Myc proteins and the ubiquitin proteins. The linkage was labile in the presence of dithiothreitol (DTT), a reducing agent (Fig. 4a), which confirmed that RhUBC32 has ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme activity.

a E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme activity of RhUBC32-Myc. Top, schematic representation of RhUBC32. An UBCc domain (yellow) and a transmembrane domain (gray) are predicted by TMHMM2 program. aa, amino acid. The star indicates the RhUBC32-ubiquitin adducts detected by anti-Myc and anti-ubiquitin antibodies. b, f In vitro autoubiquitination assay of RhRED. GST-RhRED, His-AtE1 and Ub were incubated with Human E2 (b) or RhUBC32-Myc (f). Immunoblot analysis was performed using anti-GST and anti-ubiquitin antibodies. The unmodified GST-RhRED proteins are indicated by an arrow, and the ubiquitylated GST-RhRED proteins are indicated by a bracket. c The RINGv domain is required for E3 ligase activity of RhRED. Top, schematic representation of the wild type and mutated forms of the predicted RINGv finger domain of RhRED. C62A indicated the mutation of Cysteine at position 62 to Alanine; H88A indicated the mutation of Histidine at position 88 to Alanine (similar annotations follow the same pattern). d BiFC analysis of RhUBC32 and RhRED in tobacco leaves. RhRED-cYFP with nYFP was used as a negative control. Scale bar, 50 μm. e Split-ubiquitin Y2H (MYTH) assay for interaction of RhUBC32 and RhRED. pPR3N-RhRED with pBT3-STE was used as a negative control. g RhUBC32 and RhRED facilitates the degradation of MLO-12. MLO-12-Myc protein was visualized using an anti-Myc antibody. ACTIN protein was used as a loading control. Co-infiltration of MLO-12-Myc and GFP was used as a negative control. h Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of RhBiP3 in leaves of WT, RhUBC32-RNAi, and RhRED-RNAi lines. RhUBI was used as an internal control. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences compared to WT (two-sided Student’s t-test, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001). Three independent experiments were performed for (a–d) and (f). Representative results are shown. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In order to characterize RhRED, we performed an initial phylogenetic analysis and searched the possible conserved domain of RhRED. Phylogenetic analysis showed that homologs of RhRED were discovered in various species and RhRED is relatively close to known E3 ligases of ERAD pathway, such as DEGRADATION OF ALPHA2 10 (DOA10) (Supplementary Fig. 3a). The conserved domain analysis revealed that RhRED comprises a C4HC3 RING finger domain at its N-terminus and two transmembrane domains at its C-terminus (Supplementary Fig. 3b, c). To determine whether RhRED functions as an E3 ligase, we conducted an in vitro self-ubiquitylation assay. The recombinant GST-RhRED protein was combined with Arabidopsis E1 (AtUBA1), human E2 (UBCH5b), and Arabidopsis ubiquitin (AtUBQ14), and the resulting mixture was subjected to Western blot analysis. Polyubiquitylated GST-RhRED proteins were detected using an anti-ubiquitin antibody but were not detected in mixtures lacking E1 or E2, indicating that RhRED has self-ubiquitination activity that is dependent on both E1 and E2 (Fig. 4b). We created three mutants in RING domain of RhRED, including RhRED12A (where all 9 cysteine residues and 3 histidine residues in the RING domain were substituted with alanine), RhRED5A (where C62/65/78/80/81 were substituted with alanine), and RhRED7A (where C91/96/104/107 and H88/94/108 were substituted with alanine) (Supplementary Fig. 4). Self-ubiquitination activity was not observed in any of the three mutated RhRED isoforms. Further analysis of single mutations at these 12 sites revealed that except for C80 and C96, mutations at the other sites disrupted the self-ubiquitination activity of RhRED (Fig. 4c). Based on these results, we considered that RhUBC32 is a ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme, while RhRED functions as an E3 ligase.

RhUBC32 and RhRED form a functional ERAD E2-E3 pair for degradation of RhETR3

In order to evaluate the compatibility of RhUBC32 with RhRED, we first conducted a bi-molecular fluorescence complementation assay and found that RhRED interacted with RhUBC32 on the ER membrane (Fig. 4d). This interaction was further confirmed through MYTH analysis (Fig. 4e). The in vitro ubiquitination assay confirmed that RhRED exhibited autoubiquitination activity in the presence of RhUBC32, suggesting that RhUBC32 is capable of serving as the E2 enzyme for RhRED (Fig. 4f).

To further confirm the involvement of RhUBC32 and RhRED in the ERAD pathway, we assessed their capacity to degrade MLO-12, which is recognized as a specific ERAD substrate in yeast and plants33. Co-expression of either RhUBC32 or RhRED with MLO-12 would result in reduced amounts of MLO-12 proteins, suggesting that RhUBC32 and RhRED participated in ERAD pathway (Fig. 4g). In addition, the expression of RhBiP3, a well-established marker of the ER stress response34,35, was significantly induced in the RhUBC32-RNAi and RhRED-RNAi plants (Fig. 4h), confirming that RhUBC32 and RhRED are essential components of the ERAD.

To understand if RhUBC32 and RhRED affect the stability of RhETR3 proteins, we first co-expressed RhETR3-Flag with RhUBC32-GFP or GFP alone in tobacco leaves. The presence of RhUBC32 leads to a decrease in the level of RhETR3 proteins. Furthermore, an elevated ratio of RhUBC32 to RhETR3 is associated with a more pronounced reduction in RhETR3 protein levels (Fig. 5a, b). However, this reduction of RhETR3 protein caused by RhUBC32 can be prevented by MG132 (Fig. 5a). To investigate whether the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme activity of RhUBC32 is required for RhETR3 degradation, we created a variant called RhUBC32C93A by introducing a mutation at the catalytic active site (Cys93) of RhUBC32. Subsequent assessment of the impact of this mutation on RhETR3 stability revealed that when Cys93 was mutated, the degradation of RhETR3 caused by RhUBC32 was completely abolished with or without ethylene (Fig. 5c). This indicates that the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme activity of RhUBC32 is indeed indispensable in the RhUBC32-mediated degradation of RhETR3, and ethylene treatment accelerates this degradation process. Similarly, we found that RhRED induced the degradation of RhETR3 in a dosage-dependent manner, and this degradation process can be effectively blocked by MG132 (Fig. 5d, e). Moreover, RhREDC62A, the mutation version lacking ligase activity, was found to be incapable of inducing the degradation of RhETR3 with or without ethylene (Fig. 5f).

a, d RhUBC32 and RhRED-caused degradation of RhETR3 were blocked by MG132. N. benthamiana leaves expressing RhETR3-Flag and RhUBC32-GFP or RhRED-GFP were infiltrated with MG132 before sampling. RhETR3-Flag protein was visualized using an anti-Flag antibody. ACTIN protein was used as a loading control. b, e RhUBC32 and RhRED-cause degradation of RhETR3 in a dosage-dependent manner. RhUBC32-GFP or RhRED-GFP was co-infiltrated into N. benthamiana leaves with different amounts of RhETR3-Flag. Total protein was extracted and immunoblot analysis was performed using an anti-Flag antibody. ACTIN protein was used as a loading control. c Mutation of the putative RhUBC32 active site abolishes RhUBC32-mediated degradation of RhETR3. RhETR3-Flag was co-infiltrated into N. benthamiana leaves with RhUBC32-GFP and the point-mutated form (RhUBC32C93A-GFP). N. benthamiana leaves were treated with or without ethylene. Total protein was extracted and immunoblot analysis was performed using anti-Flag and anti-GFP antibodies. ACTIN protein was used as a loading control. f Mutation of the putative RhRED active site abolishes RhRED-mediated degradation of RhETR3. RhETR3-Flag was co-infiltrated into N. benthamiana leaves with RhRED-GFP and the point-mutated form (RhREDC62A-GFP). N. benthamiana leaves were treated with or without ethylene. Total protein was extracted and immunoblot analysis was performed using anti-Flag and anti-GFP antibodies. ACTIN protein was used as a loading control. g RhRED and RhUBC32 ubiquitinates RhETR3 in vitro. GST-RhETR3, MBP-RhRED, RhUBC32-Myc, His-AtE1 and Ub were co-incubated with an in vitro ubiquitylation reaction mixture, and immunoblot analysis was performed using anti-GST and anti-ubiquitin antibodies. The unmodified GST-RhETR3 proteins are indicated by an arrow and the ubiquitylated GST-RhETR3 proteins are indicated by a bracket. h Western blot analysis of RhETR3 protein levels in WT, RhUBC32-RNAi, and RhRED-RNAi transgenic lines. Petal proteins of stage 2 rose flower treated with ethylene, were probed with anti-RhETR3 antibody. Coomassie brilliant blue (CBB) staining was used to show protein loading (bottom panel). For a–h the experiment was performed independently 3 times, and representative results are shown. The numbers of a-f and h indicate the relative intensity of the hybridization signal as detected. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Considering RhUBC32 and RhRED formed an E2-E3 pair, we next explored if RhETR3 receptors are targeted by the RhUBC32-RhRED module for degradation. After incubating purified GST-RhETR3 proteins with recombinant RhUBC32, RhRED, and Arabidopsis E1 (AtUBA1), we observed a significant reduction in RhETR3 levels in the presence of both RhUBC32 and RhRED (Fig. 5g, top). Polyubiquitylated RhETR3 proteins were also detected in mixtures containing RhUBC32 and RhRED, but not in mixtures lacking either RhUBC32 or RhRED components (Fig. 5g, bottom).

Correspondingly, Western blot revealed that RhETR3 levels were elevated in the RhUBC32-RNAi and RhRED-RNAi lines compared to the WT (Fig. 5h). Additionally, we observed that the ethylene-induced degradation of RhETR3 proteins was impeded in the RhUBC32-RNAi and RhRED-RNAi lines. These results suggest that RhUBC32 and RhRED collaborate to form a functional E2-E3 ERAD branch that controls the degradation of RhETR3.

The tomato homologs of RhUBC32 and RhRED regulate ethylene response by governing the degradation of ethylene receptor SlETR4

To investigate the functionality of the UBC32-RED ERAD branch in other plant species, we isolated homologs of RhETR3, RhUBC32, and RhRED from tomato, specifically SlUBC32 (Solyc12g099310), SlRED (Solyc05g007660), and SlETR4 (Solyc06g053710). Bi-molecular fluorescence complementation assays showed that SlUBC32, SlRED, and SlETR4 interact with each other in planta (Fig. 6a). Co-expression of SlUBC32 or SlRED with SlETR4 substantially reduced the level of SlETR4 proteins, while this degradation process was suppressed by MG132 (Fig. 6b, c). Both SlUBC32 and SlRED could induce degradation of MLO-12 (Fig. 6d). When SlUBC32-Myc proteins were incubated with recombinant Arabidopsis E1 (AtUBA1) and ubiquitin (AtUBQ14), ubiquitylated SlUBC32 were detected without DTT (Fig. 6e), confirming that a thioester linkage was formed between ubiquitin and SlUBC32. In the presence of Arabidopsis E1 (AtUBA1), human E2 (UBCH5b) and Arabidopsis ubiquitin (AtUBQ14), polyubiquitylated SlRED were detected (Fig. 6f), confirming that SlRED has the self-ubiquitination activity. Similar to what occurs with RhETR3, ubiquitylation of SlETR4 caused a shift in the gel migration of SlETR4 was detected by immunoblot analysis using anti-GST and anti-ubiquitin antibodies, respectively, in the presence of SlUBC32 and SlRED (Fig. 6g).

a BiFC analysis of SlETR4 and SlUBC32, SlRED in tobacco leaves. N. benthamiana leaves were co-infiltrated with SlRED-nYFP and SlUBC32-cYFP, or SlETR4-nYFP and SlRED-cYFP or SlETR4-nYFP and SlUBC32-cYFP constructs and imaged by confocal microscopy 2 d after infiltration. SlETR4-nYFP with cYFP and SlRED-nYFP with cYFP were used as negative controls. Scale bar, 50 μm. b, c SlUBC32 and SlRED-causes SlETR4 degradation. N. benthamiana leaves co-expressing SlETR4-Flag and SlUBC32-GFP or SlRED-GFP were infiltrated with or without 50 μM MG132 for 6 h before sampling. SlETR4-Flag was detected using anti-Flag antibody. ACTIN protein was used as a loading control. d SlUBC32 and SlRED facilitate the degradation of MLO-12. MLO-12-Myc was co-infiltrated into N. benthamiana leaves with SlUBC32-GFP or SlRED-GFP for 3 d. MLO-12-Myc protein was visualized using an anti-Myc antibody. ACTIN was used as a loading control. e E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme activity of SlUBC32 in vitro. SlUBC32-Myc was incubated with His-AtE1 and Ub for 5 min at 37 °C. Reactions were treated with 5 × SDS sample buffer with or without DTT. Immunoblot analysis was performed using anti-Myc and anti-ubiquitin antibodies. The ubiquitylated SlUBC32-Myc proteins are indicated by a star. f E3 ligase activity of SlRED in vitro. MBP-SlRED was incubated with His-AtE1, Human E2 and Ub for 1.5 h at 30 °C. Immunoblot analysis was performed using anti-MBP and anti-ubiquitin antibodies. The ubiquitylated MBP-SlRED proteins are indicated by a bracket. g SlRED and SlUBC32 ubiquitinates SlETR4 in vitro. GST-SlETR4 was incubated with AtE1, SlUBC32-Myc, MBP-SlRED and Ub for 2.5 h at 30 °C. The protein gel blot was analyzed using anti-GST and anti-ubiquitin antibody, respectively. The unmodified GST-SlETR4 proteins are indicated by an arrow and the ubiquitylated GST-SlETR4 proteins are indicated by a star. For (a–g), the experiment was performed independently 3 times, and representative results are shown. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We then knocked out SlUBC32 and SlRED in tomato using CRISPR/Cas9 system. Two homozygous SlUBC32-CR lines, slubc32–37 (1 bp deletion) and slubc32–69 (70 bp deletion), as well as two SlRED-CR lines, slred-60 (1 bp deletion) and slred-86 (261 bp deletion) were used for further tests (Fig. 7a, b). Compared to the plants transformed with the empty vector (EV), both slubc32 and slred lines exhibited smaller size with extra branches (Fig. 7c). The ripening time (days from anthesis to the red stage) of slubc32 or slred fruits were earlier than that of the EV fruits (Fig. 7d). Assessing the ripening behavior of detached mature green (MG) fruits revealed that ripening of both slubc32 and slred fuirts were significantly quicker than EV lines with or without ethylene treatment (Fig. 7e, f). Ethylene-induced degradation of SlETR4 receptors in fruits was suppressed in both slubc32 and slred lines (Fig. 7g). In addition, expression level of SlBiP3 was also significantly increased in slubc32 and slred lines (Fig. 7h). These results suggest that SlUBC32 and SlRED function as key components of ERAD and play a role in regulating the ethylene response in tomatoes by promoting the degradation of the ethylene receptor SlETR4.

a Gene structure of SlUBC32 with Protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequences (in green). 65 nucleotides (65 nt) indicate sequence not shown between two target sites, bars in black denote coding regions. b Gene structure of SlRED with PAM sequences (in green). 77 nucleotides (77 nt) indicate sequence not shown between two target sites, bars in black denote coding regions. c Plant architecture of slubc32–69, slubc32–37, slred-60, slred-86 and Empty Vector (EV) transgenic lines. The photographs were taken 6 weeks after transplant. The down row is a partial picture of the plant. The bottom row is a picture of the whole plant. Scale bar, 10 cm. d Days from anthesis to the red stage of Empty Vector (EV), slubc32–69, slubc32–37, slred-60, and slred-86 tomato fruits. DPA: days post anthesis. Data are mean ± SD, n = 166 (EV), n = 86(slubc32–37), n = 151 (slubc32–69), n = 166 (slred-60), n = 115 (slred-86). e Effect of exogenous ethylene on ripening progression of slubc32–37, slred-86 tomato fruit. EV, slubc32–37, and slred-86 tomato fruits were picked at MG stages and treated with Eth (100 ppm) for 24 h. Record the process of fruit ripening through photos. Fruits in horizontal rows are biological replicates. Bar, 5 cm. f Statistical analysis of the number of days to breaker in (e). Data are mean ± SD, from left to right, n = 18, 12, 11, 14, 17, 16, 13, 10, 18, 15. g Western blot analysis of SlETR4 protein levels in slubc32–69 and slred-60 lines treated with 20 ppm ethylene for 3 h. The protein were probed with anti-SlETR4 antibody. ACTIN was used as a loading control. h Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of SlBiP3 in immature fruits of WT, slubc32, and slred lines. SlACTIN was used as an internal control. The mean values ± SD are shown from 3 biological replicates. For (d), (f), and (g), asterisks indicate statistically significant differences compared to EV (two-sided Student’s t-test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Mutation of a conserved site essential for ethylene binding disrupted UBC32-RED module-mediated degradation of ethylene receptors

It has been long documented that binding of an ethylene molecule to its receptor results in the inactivation of the receptor and initiates signal transduction processes10. To investigate if the binding of ethylene molecules triggering the degradation of ethylene receptors, we firstly tested the effects of the ethylene action inhibitor 1-MCP (1-Methylcyclopropene) on the ethylene-induced receptor degradation. 1-MCP has a higher affinity for binding to ethylene receptors compared to ethylene, effectively blocking ethylene perception and signaling pathways36,37. 1-MCP pretreatment inhibited the ethylene-induced receptor degradation in rose flower and tomato fruit (Fig. 8a, e), suggesting ethylene binding is required for degradation of receptors. Previously, it was reported that a proline (residue 36) to leucine (P36L) substitution would totally abolish the ethylene-binding activity of AtETR111. Moreover, this site is highly conserved among ethylene receptors (Supplementary Fig. 5) and similar substitution of this conserve proline site produced two well-known dominant ethylene insensitive mutants, namely etr2-1 (P66L) in Arabidopsis and Nr (P36L) in tomato4,38. We thus generated a mutated version of RhETR3 by changing the corresponding conserved proline (residue 61) to a leucine (RhETR3P61L) (Supplementary Fig. 5). Luciferase complementation imaging and fluorescence co-colocalization assays demonstrated that the mutation of the conserved proline site does not impact the interactions of ethylene receptors with UBC32 and RED in both roses and tomatoes (Supplementary Fig. 6). Despite this, the mutation resulted in the abolishment of ethylene-induced degradation of RhETR3, even in the presence of RhUBC32 or RhRED (Fig. 8b–d). Similarly, SlETR4P60L, the corresponding mutation version of SlETR4, was unable to be degraded by ethylene (Fig. 8f–h). These results suggested that the binding of ethylene molecules to ethylene receptors could trigger UBC32-RED-mediated degradation through an ERAD pathway.

a Ethylene-induced degradation of RhETR3 was blocked by 1-MCP. Rose flowers were treated with ethylene, 1-MCP or 1-MCP and ethylene. RhETR3 protein was visualized using an anti-RhETR3 antibody. CBB staining was used to show protein loading (bottom panel). b The putative ethylene binding site of RhETR3 affects its stability under ethylene treatment. A mutation of the putative RhETR3 ethylene binding site RhETR3P61L-Flag was expressed in N. benthamiana leaves, then infiltrated with or without MG132 before ethylene treatment. Total proteins were isolated for Western blot analysis. ACTIN protein was used as a loading control. c, d Mutation of the putative RhETR3 ethylene binding site abolishes RhRED/UBC32-mediated degradation of RhETR3. RhUBC32-GFP or RhRED-GFP was co-infiltrated into N. benthamiana leaves with RhETR3-Flag and its point-mutated form RhETR3P61L -Flag, extracted their proteins after treated with ethylene in the 3th (d). RhETR3-Flag protein was visualized using an anti-Flag antibody. ACTIN protein was used as a loading control. e Ethylene-induced degradation of SlETR4 was blocked by 1-MCP. Tomato in immature green stage were treated with ethylene, 1-MCP or 1-MCP and ethylene. The protein was probed with anti-SlETR4 antibody. ACTIN was used as a loading control. f The putative ethylene binding site of SlETR4 affects its stability under ethylene treatment. A mutation of the putative SlETR4 ethylene binding site SlETR4P60L-Flag was expressed in N. benthamiana leaves, then infiltrated with or without MG132 before ethylene treatment. Total proteins were isolated for Western blot analysis. ACTIN protein was used as a loading control. g, h Mutation of the putative SlETR4 ethylene binding site abolishes SlRED/UBC32-mediated degradation of SlETR4. SlUBC32-GFP or SlRED-GFP was co-infiltrated into N. benthamiana leaves with SlETR4-Flag and its point-mutated form SlETR4P60L-Flag, extracted their proteins after treated with ethylene in the 3th (d). SlETR4-Flag protein was visualized using an anti-Flag antibody. ACTIN protein was used as a loading control. For (a–h), the experiment was performed independently 3 times, and representative results are shown. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The current model predicts that active receptors interact with CTR1, the central component of ethylene signaling, and keep CTR1 active in absence of ethylene. The receptors bound to ethylene undergo conformational changes and fail to activate CTR1, consequently initiating ethylene signaling39. Recent reports showed that ethylene treatment disrupts the interactions within ethylene receptors/CTRs complex and triggers the translocation of CTR1 from the ER to the nucleus40,41. Our data also showed that ethylene treatment impeded the interaction between RhETR3 and RhCTR1 (Supplementary Fig. 7), implying that UBC32-RED module-mediated degradation of ethylene-bound receptors might lead to release of CTR1 proteins from the receptor/CTR1 complex.

In summary, we propose that precise turnover of ethylene receptors is essential for proper plant development, particularly during processes involving high ethylene production, such as petal senescence and climacteric fruit ripening. Ethylene binding to receptors triggers their UBC-RED module-mediated degradation and initiates ethylene signaling. Concurrently, activated ethylene signaling promotes receptor gene expression and de novo receptor protein synthesis, restoring the plant’s ethylene-sensing capacity (Fig. 9).

In the absence of ethylene, the active ETRs interact with CTR1, suppressing the ethylene signaling pathway; ethylene could cause disassociation of CTR1 and ETRs and the released CTR1 will initiate ethylene signaling. The ethylene-bound receptors were recognized by UBC32-RED module and then degraded via ERAD. Meanwhile, activation of ethylene signaling resulted in elevation of ETRs expression and de novo synthesis of active receptors, replacing the degraded ethylene-bound receptors.

Discussion

Precise regulation of ethylene biosynthesis and signaling is crucial for plant development and responses to biotic and abiotic stresses. The ubiquitin–26S proteasome system (UPS) plays a well-documented role in controlling both processes. In ethylene biosynthesis, a subset of 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate synthase (ACS) enzymes, key regulators of ethylene production, are targeted for UPS-mediated degradation by an E3 ligases ETO1 (Ethylene Overproducer1) and EOL (ETO1-Like)42,43,44. In the absence of ethylene, active CTR1 phosphorylates EIN2, the central component of ethylene signaling, leading to targeting of EIN2 for UPS-mediated degradation by the F-box E3 ligases ETP1 (EIN2-TARGETING PROTEIN 1) and ETP245,46. Low EIN2 levels result in the UPS-mediated degradation of EIN3/EIL transcription factors by the F-box E3 ligases EBF1 (EIN3-BINDING F-BOX PROTEIN 1) and EBF247,48,49,50,51. In the presence of ethylene, CTR1 activity is inhibited, preventing EIN2 phosphorylation. Subsequently, EIN2-CEND is cleaved from the ER membrane and migrates into the nucleus to promote EIN3 binding to its target cis-elements to initiate transcriptional activation46,52,53. EIN2-CEND can also migrate into the cytoplasmic processing body (P-body) for translational repression of EBF1 and EBF2 and thus stabilizing EIN3/EIL154,55. Previous studies also showed that ethylene might induce UPS-mediated degradation of receptor proteins in Arabidopsis and tomato14,15. In this current study, we discovered that an ubiquitin conjugating enzyme, UBC32, and a RING E3 ligase, RED, consist of a core ERAD branch mediating ethylene-induced receptor degradation in roses and tomatoes. Ethylene binding to the receptors is required to trigger receptor degradation since mutation of ethylene binding site abolished UBC-RED module-mediated receptor degradation. Interestingly, combined ethylene and CHX/MG132 treatment confirmed that ethylene simultaneously induces receptor degradation via the ERAD pathway and promotes de novo receptor protein synthesis. Knock-out of either UBC32 or RED resulted in the accumulation of UBC-RED module-targeted receptor proteins and an ethylene-hypersensitive phenotype in rose and tomato plants. The UBC-RED module targets ethylene-bound receptors for degradation, initiating ethylene signaling; activated ethylene signaling, in turn, induces receptor gene expression and subsequent de novo receptor protein synthesis. Therefore, the UBC-RED module represents an indispensable branch of the ERAD pathway, regulating plant ethylene sensitivity through control of receptor homeostasis.

Given that ethylene binds to its receptors with surprisingly high affinity (Kd in the nM range in A. thaliana)12,13,56, repriming the receptors by dissociation from their ethylene ligand may not represent a viable mechanism to maintain ethylene sensitivity. Indeed, the half-life for dissociation of ethylene from its receptors in a heterologous yeast system was reported as being as long as 10–12 h12,13. On the other hand, in A. thaliana the phenomenon of ethylene-suppressed growth can be restored within 90 min once ethylene is removed57,58,59, and rapid release of ethylene from receptors (<30 min) has been observed in planta60,61. The apparent contradiction between the long half-life of the ethylene-receptor complex and the rapid release of ethylene from plants could be explained by our model of ethylene receptor turnover. This turnover maintains sensitivity to fluctuating ethylene concentrations, essential for adaptation and survival in dynamic environments.

The diversity of receptor function may originate from the evolutionary history of the different receptors, although conservation of ethylene as a plant hormone is more than 450 million years old62. An ETR1 receptor is present in the charophyte Klebsormidium flaccidum63, while the EIN4/ETR2-like receptor first appeared in A. trichopoda, one of the most early diverging angiosperm species64. In A. thaliana and tomato, the receptor interacting protein REVERSION-TO-ETHYLENE SENSITIVITY1/ GREEN-RIPE (RTE1/GR) interacts and modulates the action of ETR1 only65,66,67. The UBC32 and RED pair represents a conserved regulatory system in rose and tomato. Here, we show that a UBC32-RED pair mediates degradation of RhETR3 in rose and SlETR4 in tomato (Figs. 5, 6). Interestingly, both RhETR3 and SlETR4 belong to the subfamily II receptors, which are A. thaliana ETR2 homologs. It is notable that, unlike in A. thaliana, the subfamily II member RhETR3 of rose is the predominant receptor involved in regulating flower opening and senescence27,28,68. In tomato, knockdown of subfamily II receptors, LeETR4 or LeETR6, but not other receptor genes, leads to early fruit ripening15,58, while in tobacco, the subfamily II receptor NTHK1 affects growth and responses to salt stress69. Moreover, mutation of rice (Oryza sativa) ETR2 results in an enhanced ethylene response and early flowering and affects starch accumulation65. Our discovery of ERAD-mediated turnover of ETR2 homologs is important for understanding the regulation of these ETR2 homologs-dependent physiological processes, including flower senescence and fruit ripening. However, unexpectedly, in RhUBC32-RNAi and RhRED-RNAi rose lines, expression of RhETR1, RhERS1, and RhEIN4, in addition to RhETR3, was significantly elevated in leaves and petals compared to WT (Supplementary Fig. 8). Similarly, in tomato, expression of SlETR3 and SlETR6, in addition to SlETR4, was significantly increased in leaves and immature green fruits, although SlETR4 expression is much higher than SlETR3 and SlETR6 (Supplementary Fig. 9). Furthermore, a luciferase complementation assay demonstrated that, in addition to SlETR4, SlUBC32 and SlRED also interact with SlETR3 and SlETR6 (Supplementary Fig. 10). Therefore, the UBC32-RED degradation module may target receptors beyond RhETR3 and SlETR4 which are tested in this study.

Besides ethylene receptors, this UBC32-RED degradation module may regulate degradation of other proteins. Knock-out of either UBC32 or RED significantly induces the expression of Bip3, suggesting activation of the unfolded protein response (UPR). Considering that ethylene receptors are localized on the ER membrane, the abnormal accumulation of receptor proteins caused by knock-out of UBC32 or RED may be a causal factor for the activation of UPR in the UBC32 and RED. On the other hand, our results also indicate that the UBC32-RED module is capable of degrading MLO-12, suggesting that ethylene receptors might not be the only substrate of UBC32-RED module.

RhRED or SlRED represents a conserved E3 and shed light on the role of ERAD in specific physiological processes. ERAD was previously considered to be a surveillance system for ER protein quality only, of which E3 ligases are a central and defining component due to their roles in substrate recognition, connecting substrates and E2 enzymes, and activating E2-Ub66,67. To date, most knowledge of E3 ligases in the ERAD pathway has been obtained from studies in yeast and mammals. Hrd1 (HMG-COA reductase degradation 1) and Doa10 (Degradation of alpha2 10) from budding yeast are the two best characterized E3 ligases in the ERAD pathway70,71.

There is growing evidence that the ERAD pathway is also involved in the regulation of physiological processes by governing the turnover of specific proteins. For example, in yeast and mammals, the E3 ligases Hrd1/Gp78 and Doa10/Teb4 are responsible for ERAD processing of 3-hydroxy-3methyglutaryl acetyl-coenzymes-A reductase (HMGR) and squalene monooxygenase, respectively, and for maintaining sterol homeostasis72,73,74. In plants, the degradation of HMGR is controlled by SUD1 (a homolog of Doa10) and MKB1 (a RING membrane-anchored E3 ligase), associated with mevalonic acid synthesis and saponin accumulation, respectively75,76. In addition, A. thaliana Hrd1A/1B and EBS5 (EMS-mutagenized bri1 suppressor 5), a homolog of yeast Hrd3/mammalian Sel1L, can mediate degradation of bri1-5 and bri1-9, two ER-retained mutant variants of the cell-surface receptor for brassinosteroids31,77. The E3 ligase ECERIFERUM9 (CER9), a homolog of yeast Doa10, is involved in both wax/cutin synthesis and abscisic acid biosynthesis, and thus regulates maintenance of plant water status and seed germination78,79. Our results demonstrate that RhRED interacts with RhUBC32, a homolog of A. thaliana UBC32, to degrade the RhETR3 ethylene receptor (Figs. 4, 5). Silencing of RhRED elevated flower sensitivity to ethylene (Fig. 4). We propose that the RhUBC32-RhRED pair defines an ERAD mechanism involved in regulating development through the shaping of ethylene sensitivity. Notably, protein sequence homology analyses identified close homologs of RhRED in several early diverging land plant species, including A. trichopoda and S. moellendorffii (Supplementary Fig. 3c), indicating that RED is an evolutionarily conserved plant RING ER-anchored E3 ligase.

Another interesting question is how RhRED recognizes ethylene-bound receptors. In the case of HMGR regulation, high levels of sterols lead to the accumulation of 24, 25-dihydrolanosterol, an intermediate sterol biosynthesis metabolite. Binding of 24, 25-dihydrolanosterol to HMGR triggers the recognition of HMGR by Insig-1/2, an adapter of E3 ligase, and its subsequent degradation. Whether ethylene binding causes conformational and/or protein modification changes of the receptor, and thereby triggers substrate recognition by RhRED is a topic for future investigation73.

In summary, our findings revealed an ERAD module for regulating the degradation of ethylene receptors (Fig. 9), and thus shed light on the underlying mechanism for attenuation of ethylene sensitivity in diverse physiological processes.

Methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

Rosa sp. cv. Samantha plantlets were propagated by tissue culture as previously described80. Rose stems with at least 1 node were used as explants and cultured on MS media (Duchefa Biochemie, Haarlem, Netherlands) supplemented with 1.0 mg L−1 6-BA, 1.0 mg L−1 GA3, and 0.05 mg L−1 α-NAA for 30 days at 22 ± 1 °C, under a 16 h light/ 8 h dark photoperiod. The shoots were then transferred to 1/2-strength MS medium supplemented with 0.1 mg L−1 NAA for 30 days for rooting. The rooted plants were transferred to pots containing peat moss: vermiculite (2:1), and were grown at 22 ± 1 °C with a relative humidity of ~60% and a 16 h /8 h (light/dark) photoperiod. Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) M82 and transgenic tomato plants were grown in a greenhouse in Beijing, China, with long-day conditions. N. benthamiana plants were grown in pots in a growth chamber at 23 °C under a 16 h/8 h photoperiod and ~60% relative humidity.

Plasmid construction

Vector construction related to rose study. The full-length coding sequences of RhETR3 were insert into pBT3-STE in the Sfi I site, pSuper1300-Flag vector between the Sal I and Kpn I sites, pSuper1300-Mcherry vector between the Sal I and Kpn I sites, pSPYNE(R) vector between the BamH I and Kpn I sites, pCAMBIA-nLUC vector between the BamH I and Spe I sites, pGEX4T-2 vector between the BamH I and Sal I sites. The RhUBC32 coding sequence was inserted into pPR3N-N in the Sfi I site, pSuper1300-GFP vector between the Sal I and Kpn I sites, pSuper1300-Flag vector between the Sal I and Kpn I sites, pSPYCE(M) vector between the BamH I and Kpn I sites, pCAMBIA-cLUC vector between the BamH I and Spe I sites, pET28a-myc vector between the Sac I and Xho I sites, the mutant of RhUBC32 ubiquitin binding enzyme active site RhUBC32C92A was insert into pSuper1300-GFP between the Sal I and Kpn I sites, the Gene-specific fragments of RhUBC32 (403 bp in length) was insert into pTRV2 between the Kpn I and Sac I sites. The RhRED coding sequence was inserted into pPR3N-N in the Sfi I site, pSuper1300-GFP vector between the Hind III and Kpn I sites, pSPYCE (M) vector between the BamH I and Spe I sites, pCAMBIA-cLUC vector between the BamH I and Spe I sites, pGEX4T-2 vector in the BamH I and Sal I sites, pMalC2 vector between the BamH I and Sal I sites, the mutants of RhRED ubiquitin ligase enzyme active sites were insert into pMalC2 between the BamH I and Sal I sites, the Gene-specific fragments of RhRED (390 bp in length) was insert into pTRV2 between the Xba I and Kpn I sites. All primers used in this study are listed in Supplementary Data 2.

Vector construction related to tomato study. The full-length coding sequences of SlETR4 were insert into pSuper1300-Flag between the Sal I and Kpn I sites, pSPYNE (R) vector between the BamH I and Kpn I sites, pGEX4T-2 vector between the BamH I and Sal I sites, the mutant of SlETR4 putative ethylene binding site SlETR4P60L was insert into pSuper1300-Flag between the Sal I and Kpn I sites, a SlETR41594–2052 fragment (10) was inserted into pET28a in the BamH I and Sal I sites. The SlUBC32 coding sequence was inserted into pSuper1300-GFP vector between the Sal I and Kpn I sites, pSPYCE (M) vector between the BamH I and Kpn I sites, pET28a-myc vector between the Sac I and Xho I sites. The SlRED coding sequence was inserted into pSuper1300-GFP between the Sal I and Kpn I sites, pSPYCE (M) vector between the BamH I and Xho I sites, pSPYNE (R) vector between the BamH I and Xho I sites, pMalC2 vector between the BamH I and Sal I sites. All primers used in this study are listed in Supplementary Data 2.

Rose transformation

For the RhUBC32 RNAi construct, two primer sets with different restriction enzyme sites were used to amplify a 405 bp gene-specific fragment. One set, with Asc I and Swa I sites, was digested and inserted in sense orientation into the pFGC1008 vector; the other, with Pac I and Bam H I sites, was digested and inserted in antisense orientation into the pFGC1008 vector.

Transgenic rose plants were generated as described previously with minor modifications81. The RNAi construct was introduced into Agrobacterium strain EHA105 and grown overnight. The bacteria were collected by centrifugation and re-suspended in infiltration solution (MS + 45 g L−1 glucose + 100 mM acetosyringone). The bacterial suspension was adjusted with infiltration solution to an OD600 = 0.5 and incubated for 2 h at 28 °C with shaking (200 rpm). The somatic embryos were immersed in the bacterial suspension exposed to a vacuum of −25 KPa twice, each for 5 min and incubated for 40 min at 28 °C with shaking (180 rpm). The somatic embryos were briefly washed and dried on sterilized paper towels to remove excess bacterium solution. The somatic embryos were incubated on Co-cultivation Medium (CM, MS + 1.0 mg L−1 2, 4-D + 0.05 mg L−1 6-benzylamino-purine (6-BA) + 60 g L−1 glucose + 2.5 g L−1 GEL + 100 mg L−1 casein hydrolysate (CH) + 100 mM acetosyringone) at room temperature in the dark for 3 days without selection. The somatic embryos were selected on Selective Proliferation Medium (SPM, MS + 1.0 mg L−1 2, 4-D + 0.05 mg L−1 6-BA + 60 g L−1 glucose + 2.5 g L−1 GEL + 20 mg L−1 Hygromycin B + 300 mg L−1 cefotaxime sodium) and incubated at 23 ± 1 °C under a 16-h light/ 8-h dark photoperiod. The somatic embryos removed to new medium every 2 weeks. After two months selection, the healthy somatic embryos were removed to Selective Germination Medium (SGM, MS + 1.0 mg L−1 6-BA + 0.05 mg L−1 NAA + 1.0 mg L−1 GA3 + 0.1 mg L−1 CH + 30 g L−1 sucrose + 7.0 g L−1 agar + 20 mg L−1 Hygromycin B + 300 mg L−1 cefotaxime sodium), replace new medium every month. When resistant shoots appeared, they were transformed to Rooting Medium (1/2 MS + 0.1 mg L−1 NAA + 30 g L−1 sucrose + 7.0 g L−1 agar) to induce roots. Rooted plants were transferred to pots containing a 2:1 volume of peat moss and vermiculite and grown at 22 ± 1 °C with a relative humidity of ~60% and a 16 h /8 h (light/dark) photoperiod. To identify the transgenic plants, genomic DNA was extracted from young plant leaves using CTAB and used as a template to amplify the selective gene (Hyg) and T-DNA insert. Quantitative RT-PCR was used to analysis the expression of RhUBC32 in the transgenic line flowers. Primers used are listed in Supplementary Data 2.

CRISPR-Cas9 mutagenesis and tomato transformation

Two target sites (gRNA) for each gene were selected using the CRISPR program (http://crispor.tefor.net/crispor.py), and the assembled gRNA spacers were introduced in one step into pDIRECT_22C with a previously reported protocol82. The plasmids were transformed into the Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101, and used to transform wild tomato M82 cotyledons83. For genotyping of the T0 and T1 transgenic lines, the young tomato leaves were collected and extracted genomic DNA with the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method. These genomic DNA were used as templates to amplify the SlUBC32, SlRED fragment, then Sanger sequencing was performed to identify mutations in target genes of T0 and T1 CRISPR plants. gRNA and primer sequences for genotyping can be found in Supplementary Data 2.

Western blot analysis

To generate an anti-RhETR3 antibody, a RhETR31525–2187 fragment was inserted into the pET-32a vector and the recombinant protein was expressed in, and purified from, the E. coli Rosetta strain. The purified recombinant proteins were injected into rabbits to generate polyclonal anti-RhETR3 antibody (ABclonal Biotech, Wuhan, China, https://abclonal.com.cn/). The antibody was validated by Western blot and liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS) assay.

To generate an anti-SlETR4 antibody, a SlETR41594–2052 fragment (10) was inserted into the pET28a vector and the recombinant proteins were expressed in, and purified from, the E. coli BL21 (DE3) strain. The purified recombinant proteins were injected into rabbits to generate polyclonal anti-SlETR4 antibodies (ABclonal Biotech, Wuhan, China, https://abclonal.com.cn/).

For Western blot analysis, protein extraction was performed as previously described. Protein extracts were separated on 8% SDS-PAGE gels, and then transferred to a PVDF (Millipore) or a NC (GE) membrane using transfer buffer (39 mM glycine, 48 mM Tris, 20% [V/V] methanol). The target proteins were detected with anti-GFP (Abmart, P30010; EASYBIO, BE2002), anti-MBP (NEB, E8032), anti-GST (EASYBIO, BE2013), anti-Flag (Abclonal, AE005), or anti-ubiquitin (Beyotime, AF1075; EASYBIO, BE4002) antisera, each in a 1:5,000 dilution. For anti-RhETR3, in a 1:2,000 dilution, for anti-SlETR4, in a 1:3000 dilution. Peroxidase conjugated anti-rabbit/mouse antibody (EASYBIO) was used in a 1:10,000 dilution as the secondary antibody.

In vivo and in vitro protein degradation assay

For the stability assay of RhETR3 and SlETR4 proteins, RhETR3-Flag, SlETR4-Flag, and SlETR4P60L-Flag were expressed in N. benthamiana leaves for 3 days, and then the plants were sealed in air-tight containers with, or without, 100 ppm ethylene for 3 h. Subsequently, total protein was extracted from the N. benthamiana leaves with 2 × SDS protein loading buffer, boiled and subjected to Western blot analysis as described above84.

For the RhUBC32-, RhRED-accelerated degradation of RhETR3, RhETR3-Flag was co-expressed with RhUBC32-GFP or RhRED-GFP in N. benthamiana leaves for 3 days, and then infiltrated with 0 or 50 μM MG132 for 6 h before ethylene treatment. Proteins were extracted from infiltrated leaves for Western blot analysis. Co-expression of RhETR3-Flag with GFP was used as a control.

For the assay determining RhUBC32, RhRED-accelerated degradation of RhETR3, RhETR3-Flag was co-expressed with RhUBC32-GFP or RhRED-GFP in different ratios RhUBC32-GFP, RhRED-GFP/RhETR3-Flag were 0/1, 0.5/1, 1/1, 2/1, (v/v) in N. benthamiana leaves for 3 days. Proteins were extracted from infiltrated leaves for Western blot analysis. Co-expression of RhETR3-Flag with GFP was used as a control.

To test the effects of RhUBC32 and RhRED active sites on the stability of RhETR3, RhETR3-Flag was co-expressed with RhUBC32-GFP and point mutant form (RhUBC32C93A-GFP) or RhRED-GFP and the mutant form (RhREDC62A-GFP) in N. benthamiana leaves for 3 days, and then treated with or without 100 ppm for 3 h. Proteins were extracted from the infiltrated leaves for Western blot analysis.

For the assay determining SlUBC32/SlRED-accelerated degradation of SlETR4, SlETR4-Flag, SlETR4P60L -Flag were co-expressed with SlUBC32-GFP, SlRED-GFP in N. benthamiana leaves for 3 days, and then the plants were sealed in air-tight containers with 100 ppm ethylene for 3 h after MG132 treatment. Proteins were extracted from infiltrated leaves for Western blot analysis. Co-expression of SlETR4-Flag, SlETR4P60L -Flag with GFP was used as a control.

E2 ubiquitin conjugation assay

The E2 ubiquitin conjugation assay (formation of DTT sensitive thioester bonds) was performed as previously described32,85. RhUBC32-Myc-His, SlUBC32-Myc-His were expressed in E. coli strain BL21 (DE3) and the recombinant proteins were purified using Ni-NTA His-Bind resin (Millipore).

Thioester bond assays were performed in a total reaction volume of 30 μL, consisting of 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM ATP, 50 ng A. thaliana E1 (AtUBA1), 2 μg purified E2 protein (RhUBC32-Myc, SlUBC32-Myc), and 10 μg His-tagged A. thaliana ubiquitin (AtUBQ14). The reactions were incubation for 5 min at 37 °C and terminated by addition of 5 × SDS sample buffer with or without DTT and boiled for 10 min. Finally, the reaction products were separated by SDS-PAGE and detected using an anti-Myc and anti-ubiquitin antibody, respectively.

Autoubiquitination of E3 ligase

E. coli BL21 expressed GST-RhRED and MBP-RhRED, or the MBP-RhRED12A, MBP-RhRED5A, MBP-RhRED7A and MBP-SlRED proteins, were purified using Glutathione SepharoseTM 4B (GE) (for GST fused proteins) or Amylose Resin E8021S (NEB) (for MBP fused proteins). The purified proteins were used for RhRED and SlRED autoubiquitination assays. Briefly, the assays were performed in a total reaction volume of 30 μl, consisting of 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 25 mM MgCl2, 10 mM ATP, 2.5 mM DTT, 50 ng A. thaliana E1 (AtUBA1), 100 ng human E2 (UBCH5b) or RhUBC32, 500 ng E3 (GST- or MBP-RhRED, MBP-SlRED), and 4 μg His-tagged A. thaliana ubiquitin (AtUBQ14). The reaction mixture was incubated for 90 min at 30 °C with shaking at 900 rpm. Reactions were terminated by adding 6 μl of 5 × SDS loading buffer, and proteins were separated on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel and visualized by immunoblotting, using anti-GST/MBP and anti-ubiquitin antibodies.

In vitro ubiquitylation assay

The in vitro ubiquitination assay was performed as previously described85, RhUBC32-Myc, SlUBC32-Myc, MBP-RhRED, MBP-SlRED, GST-RhETR3, and GST-SlETR4 were expressed in E. coli Rosetta (DE3) cells, respectively. The assays were performed63n a total reaction volume of 30 μl, consisting of 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 25 mM MgCl2, 10 mM ATP, 2.5 mM DTT, 100 ng A. thaliana E1 (AtUBA1), 100 ng human E2 (UBCH5b)/ RhUBC32-Myc/ SlUBC32-Myc, 500 ng MBP-RhRED/ MBP-SlRED, 500 ng GST-RhETR3/ GST-SlETR4 and 4 μg His-tagged A. thaliana ubiquitin (AtUBQ14). Reactions were performed at 30 °C with agitation in an Eppendorf Thermomixer for 2.5 h and then were terminated by adding 6 μl of 5 × SDS loading buffer, and proteins were separated on 8% SDS-PAGE gel and visualized by immunoblotting using anti-GST and anti-ubiquitin antibodies.

Split-ubiquitin yeast two-hybrid assay

Screening for RhETR3 interactors was performed as previously described80, using a split-ubiquitin based membrane yeast two-hybrid system (DUALsystems biotech, Schlieren, Switzerland). The coding region of RhETR3 was amplified by PCR using rose cDNA (generated from total RNA extracted from leaves) as a template and cloned into the pBT3-STE bait vector, using the Sfi I restriction site. To construct the R. sp. cv Samantha cDNA library, mRNA was isolated from rose petals with the PolyA Tract mRNA Isolation System II (Promega), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was synthesized using a Dualsystems Biotech EasyClone cDNA synthesis kit, and then transformed into yeast strain NMY51 according to the user manual (DUALsystems Biotech, Switzerland). The yeast transformants were plated onto synthetic dropout (SD, FunGenome, China) medium without leucine (Leu) and tryptophan (Trp) to confirm the co-transformation efficiency. The yeast transformants were also spread with different dilution onto SD medium lacking histidine (His). Positive clones were grown on the SD-Leu-Trp-His-Ade selection medium and tested in the presence of β-galactosidase. Plasmids were extracted from the positive yeast clones using a Yeast Plasmid Mini Kit (Omega, USA) and transformed into E. coli for sequencing.

The vectors pPR3N and pBT3-STE were used in this assay. The full-length RhETR3 coding sequence or truncated sequences with or without transform domain were cloned into pBT3-STE, while the full-length RhUBC32/RhRED were cloned into pPR3N. The corresponding plasmids were co-transformed into yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) NMY51 cells as described previously. After 3 days, yeast colonies grew on yeast synthetic dropout medium lacking Leu and Trp were suspended in water, then the suspended cells were diluted to 1×, 10×, and plated on yeast synthetic dropout medium lacking His, Leu, Trp, and Ade with or without β-galactosidase to test protein interactions.

BiFC assay and subcellular location analysis

The full-length RhETR3, SlETR4, and SlRED were fused with N-terminal YFP vector pSPYNE(R), and RhUBC32, RhRED, SlUBC32, SlRED were fused with C-terminal YFP vector pSPYCE(M). Agrobacterium strain GV3101 was transformed with the above vector or control vector were resuspended in infiltration buffer (10 mM MgCl2, 200 mM acetosyringone, and 10 mM MES, pH 5.6) to a final OD600 = 3.0 and then mix the above Agrobacterium strains in a ratio of 1: 1: 1 (v/v/v), shaking with 200 rpm at 28 °C for 3 h before injected into young N. benthamiana leaves. Fluorescence signals were observed with confocal microscopy in the 2th d after injection. The RhETR3 was fused with pSuper1300-mCherry, and RhUBC32, RhRED were fused with pSuper1300-GFP. Agrobacterium strain GV3101 was transformed with the above vector or control vector were resuspended in infiltration buffer to a final OD600 = 1.5, P19 strain OD600 = 1.0 and then mix the above Agrobacterium strains in a ratio of 1: 1: 1 (v/v/v), placing in the dark at room temperature for 3–5 h before injection. Fluorescence signals were observed with confocal microscopy on the 2th d after injection.

Firefly luciferase complementation imaging (LCI) assays

The RhETR3 was fused to the N-terminal of pCAMBIA-nLUC, and RhUBC32, was fused to the C-terminal of pCAMBIA-cLUC vectors. Agrobacterium strain GV3101 was transformed with the above vector or control vector were resuspended in infiltration buffer to a final OD600 = 3.0, P19 strain OD600 = 1.0 and then mix the above Agrobacterium strains in different ratios, RhETR4-nLUC: RhUBC32-cLUC were 1/0, 1/0.25, 1/1, 1/2, (v/v), P19 was added to ensure efficient expression of the fusion proteins. After 3–5 h, the bacteria were injected into yang tobacco leaves. Two days later, 1 mM luciferin was sprayed onto the leaves, and kept in the dark for 5–10 min, the exposure time was 15 min. A low-light cooled CCD imaging apparatus (CHEMIPROHT 1300B/LND, 16 bits; Roper Scientific) was used to capture the LUC image.

RNA extraction and quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted, as previously described27,80 and then reverse transcribed using HiScript II Q RT SuperMix (R223-01, Vazyme Biotech Co., Nanjing, China). Quantitative RT-PCR was performed on a Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, CA, USA) with ChamQ SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Q331-01, Vazyme Biotech Co., Nanjing, China). The rose RhUBI gene was used as an internal control, and all the reactions were performed in triplicate. PCR primers are listed in Supplementary Data 2.

Protein extraction and immunoprecipitation

Protein extraction of rose flowers and tomato fruits was performed as previously described. ~500 mg of plant tissue was ground in liquid nitrogen to a fine powder using a mortar and pestle. The powder was homogenized with 1 ml of 10% TCA/acetone and centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 3 min (4 °C). The pellet was washed once with 80% methanol, 0.1 M ammonium acetate and once with 80% acetone, before being air-dried at room temperature for at least 15 min to remove residual acetone. The pellet was dissolved in 0.8 ml of 1: 1 phenol (pH 8.0, Sigma) / SDS buffer (30% sucrose, 2% SDS, 0.1 M Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 5% β-mercaptoethanol) by vortexing and centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 5 min (4 °C). The upper phenol phase was transferred into a new tube and mixed with 1.5 ml of 100% methanol containing 0.1 M ammonium acetate. The proteins were precipitated at −20 °C for 30 min and then collected by centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 5 min (4 °C). The pellet was washed once with 100% methanol and once with 100% acetone, and then briefly air-dried. The pellet was then dissolved in 2 × SDS loading buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 20% glycerin, 4% SDS, 0.2% bromophenol blue, 5% β-mercaptoethanol) and the proteins fractionated by SDS-PAGE.

The harvested tobacco leaves were ground in liquid nitrogen and resuspend in extraction buffer on ice and centrifuged at 13000 g at 4 °C for 10 min. The supernatant was subjected to protein gel blots. Two different protein extraction buffers were used: denaturing buffer (2 × SDS loading buffer: 200 mM Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 4% SDS, 5% β-mercaptoethanol, 20% glycerinum), native extraction buffer (NB: 50 mM Tris-HCl pH7.5, 5 mM EDTA, 5 mM EGTA, 10 mM Na3VO4, 10 mM NaF, 50 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 10 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, 5% glycerol, and 1X EDTA-Free cOmplete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail).

For immunoprecipitation and co-immumoprecition asssy, the N. benthamiana leaves expressed RhUBC32-Flag, co-expressed RhETR3-Flag and GFP or RhETR3-Flag and RhUBC32-GFP were extracted with native extraction buffer (NB) as described above. Total protein extracts were incubated with prewashed ANTI-FLAG M2 Affinity Agarose Gel (sigma) at room tempreture for 1 h. The agarose gel was washed 3 times with the TBS (50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) and boiled with 5 × SDS loading buffer, separated by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted with anti-Flag and anti-GFP antibodies.

Ethylene treatment

For ethylene-induced degradation assay, the rose plants with the flowers in stage 2 were sealed in air-tight containers and treated with 0 or 10 ppm ethylene for 3 h. For tomato, the tomato fruits in the mature green stage were sealed in air-tight containers and treated with 0 or 20 ppm ethylene for 3 h. For N. benthamiana, the plants on the 3th d after injection were sealed in air-tight containers with, or without, 100 ppm ethylene for 3 h.

For ethylene-induced flower opening, rose flowers in stage 2 were sealed in air-tight containers and treated with 0 or 10 ppm ethylene for 24 h. 1 M NaOH solution was present in the containers to prevent CO2 accumulation21.

For 1-MCP and 1-MCP + ethylene treatment, rose flowers at stage 2 were treated with 2 ppm 1-MCP 16 h or 10 ppm ethylene for 3 h after 1-MCP treatment. For tomato, the tomato fruits in immature green stage were treated with 2 ppm 1-MCP 16 h or 20 ppm ethylene for 3 h after 1-MCP treatment.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., USA: http://www.graphpad.com/). Comparisons between two groups of data were made using a two-sided Student’s t-test (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available in the main text or the supplementary information. The RhETR3 mass spectrometry proteomics data generated in this study have been deposited in the ProteomeXchange database under accession code PXD064054. The biological materials used in this study are available from N.M. on request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Abeles, F. B., Morgan, P. & Saltveit, M. J. Ethylene in Plant Biology. Academic Press (1992).

Hua, J., Chang, C., Sun, Q. & Meyerowitz, E. M. Ethylene insensitivity conferred by Arabidopsis ERS gene. Science 269, 1712–1714 (1995).

Hua, J. et al. EIN4 and ERS2 are members of the putative ethylene receptor gene family in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 10, 1321–1332 (1998).

Sakai, H. et al. ETR2 is an ETR1-like gene involved in ethylene signaling in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 5812–5817 (1998).

Bleecker, A. B. Ethylene perception and signaling: an evolutionary perspective. Trends Plant Sci. 4, 269–274 (1999).

Chang, C. & Stadler, R. Ethylene hormone receptor action in Arabidopsis. Bioessays 23, 619–627 (2001).

Schaller, G. E. & Kieber, J. J. Ethylene. The Arabidopsis Book. (American Society of Plant Biologists, 2002).

Gamble, R. L., Coonfield, M. L. & Schaller, G. E. Histidine kinase activity of the ETR1 ethylene receptor from Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 7825–7829 (1998).

Moussatche, P. & Klee, H. J. Autophosphorylation activity of the Arabidopsis ethylene receptor multigene family. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 48734–48741 (2004).

Hua, J. & Meyerowitz, E. M. Ethylene responses are negatively regulated by a receptor gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana. Cell 94, 261–271 (1998).

Wang, W. Y. et al. Identification of important regions for ethylene binding and signaling in the transmembrane domain of the ETR1 ethylene receptor of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 18, 3429–3442 (2006).

Schaller, G. E. & Bleecker, A. B. Ethylene-binding sites generated in yeast expressing the Arabidopsis ETR1 gene. Science 270, 1809–1811 (1995).

O’Malley, R. C. et al. Ethylene-binding activity, gene expression levels, and receptor system output for ethylene receptor family members from Arabidopsis and tomato. Plant J. 41, 651–659 (2005).

Kevany, B. M. et al. Ethylene receptor degradation controls the timing of ripening in tomato fruit. Plant J. 51, 458–467 (2007).

Chen, Y. F. et al. Ligand-induced degradation of the ethylene receptor ETR2 through a proteasome-dependent pathway in Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 24752–24758 (2007).

Woltering, E. J. Interorgan translocation of 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic Acid and ethylene coordinates senescence in emasculated cymbidium flowers. Plant Physiol. 92, 837–845 (1990).

Stanley, P. et al. Ethylene and auxin participation in pollen induced fading of vanda orchid blossoms. Plant Physiol. 42, 1648–1650 (1967).

Gou, C. J. et al. Ethylene evolution and sensitivity in cut orchid flowers. Sci. Horticulturae 26, 57–67 (1985).

Nichols, R. Ethylene production during senescence of flowers. Hortic. Sci. 41, 279–290 (1966).

ERNST, J. et al. Role of ethylene in senescence of petals—morphological and taxonomical relationships. J. Exp. Bot. 39, 1605–1616 (1988).

Pei, H. X. et al. An NAC transcription factor controls ethylene-regulated cell expansion in flower petals. Plant Physiol. 163, 775–791 (2013).

Liu, X. et al. Characterization of ethylene biosynthesis associated with ripening in banana fruit. Plant Physiol. 121, 1257–1661 (1999).

Cheng, C. X. et al. Ethylene-regulated asymmetric growth of the petal base promotes flower opening in rose (Rosa hybrida). Plant Cell 33, 1229–1251 (2021).

Liang, Y. et al. Auxin regulates sucrose transport to repress petal abscission in rose (Rosa hybrida). Plant Cell 32, 3485–3499 (2020).

Qu, X., Hall, B. P., Gao, Z. & Schaller, G. E. A strong constitutive ethylene-response phenotype conferred on Arabidopsis plants containing null mutations in the ethylene receptors ETR1 and ERS1. BMC plant Biol. 7, 3 (2007).

Reid, M. S., Evans, R. Y., Dodge, L. L. & Mor, Y. Ethylene and silver thiosulfate influence opening of cut rose flowers. J. Am. Soc. Hort. Sci. 114, 436–440 (1989).

Ma, N. et al. Transcriptional regulation of ethylene receptor and CTR genes involved in ethylene-induced flower opening in cut rose (Rosa hybrida cv. Samantha). J. Exp. Bot. 57, 2763–2773 (2006).

Liu, D. F. et al. An organ-specific role for ethylene in rose petal expansion during dehydration and rehydration. J. Exp. Bot. 64, 2333–2344 (2013).

Zhang, Z. et al. Haplotype-resolved genome assembly and resequencing provide insights into the origin and breeding of modern rose. Nat. Plants 10, 1659–1671 (2024).

Bachmair, A., Novatchkova, M., Potuschak, T. & Eisenhaber, F. Ubiquitylation in plants: a post-genomic look at a post-translational modification. Trends Plant Sci. 6, 463–470 (2001).

Lenk, U. et al. A role for mammalian Ubc6 homologues in ER-associated protein degradation. J. Cell Sci. 115, 3007–3014 (2002).

Cui, F. et al. Arabidopsis ubiquitin conjugase UBC32 is an ERAD component that functions in brassinosteroid-mediated salt stress tolerance. Plant Cell 24, 233–244 (2012).

Müller, J. et al. Conserved ERAD like quality control of a plant polytopic membrane protein. Plant Cell 17, 149–163 (2005).

Martínez, I. M. & Chrispeels, M. J. Genomic analysis of the unfolded protein response in Arabidopsis shows its connection to important cellular processes. Plant Cell 15, 561–576 (2003).

Iwata, Y. & Koizumi, N. An Arabidopsis transcription factor, AtbZIP60, regulates the endoplasmic reticulum stress response in a manner unique to plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 5280–5285 (2005).

Sisler, E. C. & Serek, M. Compounds interacting with the ethylene receptor in plants. Plant Biol. 5, 473–480 (2003).

Blankenship, S. M. & Dole, J. M. 1-Methylcyclopropene: a review. Postharvest Biol. Tec. 28, 1–25 (2003).

Wilkinson, J. Q. et al. An Ethylene-Inducible component of signal transduction encoded by Never-ripe. Science 270, 1807–1809 (1995).

Zhao, H. et al. Ethylene signaling in rice and Arabidopsis: New regulators and mechanisms. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 63, 102–125 (2021).

Park, H. L. et al. Ethylene-triggered subcellular trafficking of CTR1 enhances the response to ethylene gas. Nat. Commun. 14, 365 (2023).

Li, X. K. et al. Membrane protein MHZ3 regulates the on-off switch of ethylene signaling in rice. Nat. Commun. 15, 5987 (2024).

Chae, H. S., Faure, F. & Kieber, J. J. The eto1, eto2, and eto3 mutations and cytokinin treatment increase ethylene biosynthesis in Arabidopsis by increasing the stability of ACS protein. Plant Cell 15, 545–559 (2003).

Wang, K. L., Yoshida, H., Lurin, C. & Ecker, J. R. Regulation of ethylene gas biosynthesis by the Arabidopsis ETO1 protein. Nature 428, 945–950 (2004).

Tan, S. T. & Xue, H. W. Casein kinase 1 regulates ethylene synthesis by phosphorylating and promoting the turnover of ACS5. Cell Rep. 9, 1692–1702 (2014).

Qiao, H., Chang, K. N., Yazaki, J. & Ecker, J. R. Interplay between ethylene, ETP1/ETP2 F-box proteins, and degradation of EIN2 triggers ethylene responses in Arabidopsis. GENE DEV 23, 512–521 (2009).

Ju, C. L. et al. CTR1 phosphorylates the central regulator EIN2 to control ethylene hormone signaling from the ER membrane to the nucleus in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 19486–19491 (2012).

Potuschak, T. et al. EIN3-dependent regulation of plant ethylene hormone signaling by two arabidopsis F box proteins: EBF1 and EBF2. Cell 115, 679–689 (2003).

Guo, H. & Ecker, J. R. Plant responses to ethylene gas are mediated by SCF (EBF1∕EBF2)-dependent proteolysis of EIN3 transcription factor. Cell 115, 667–677 (2003).

Gagne, J. M. et al. Arabidopsis EIN3-binding F-box 1 and 2 form ubiquitin-protein ligases that repress ethylene action and promote growth by directing EIN3 degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 6803–6808 (2004).

Binder, B. M. et al. The Arabidopsis EIN3 binding F-Box proteins EBF1 and EBF2 have distinct but overlapping roles in ethylene signaling. Plant Cell 19, 509–523 (2007).

An, F. Y. et al. Ethylene-induced stabilization of ethylene insensitive3 and ein3-like1 is mediated by proteasomal degradation of ein3 binding f-box 1 and 2 that requires ein2 in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 22, 2384–2401 (2010).

Qiao, H. et al. Processing and subcellular trafficking of ER-tethered EIN2 control response to ethylene gas. Science 338, 390–393 (2012).

Wen, X. et al. Activation of ethylene signaling is mediated by nuclear translocation of the cleaved EIN2 carboxyl terminus. Cell Res 22, 1613–1616 (2012).

Li, W. Y. et al. EIN2-directed translational regulation of ethylene signaling in Arabidopsis. Cell 163, 670–683 (2015).

Merchante, C. et al. Gene-specific translation regulation mediated by the hormone-signaling molecule EIN2. Cell 163, 684–697 (2015).

Rodríguez, F. I. et al. A copper cofactor for the ethylene receptor ETR1 from Arabidopsis. Science 283, 996–998 (1999).

Binder, B. M. et al. Arabidopsis seedling growth response and recovery to ethylene. A kinetic analysis. Plant Physiol. 136, 2913–2920 (2004).

Tieman, D. M., Taylor, M. G., Ciardi, J. A. & Klee, H. J. The tomato ethylene receptors NR and LeETR4 are negative regulators of ethylene response and exhibit functional compensation within a multigene family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 5663–5668 (2000).

Cancel, J. D. & Larsen, P. B. Loss-of-Function mutations in the ethylene receptor ETR1 cause enhanced sensitivity and exaggerated response to ethylene in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 129, 1557–1567 (2002).

Sanders, I. O. et al. Ethylene binding in wild type and mutant Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. Ann. Bot. 68, 97–103 (1991).

Chen, Y. F. et al. Ethylene receptors function as components of high-molecular-mass protein complexes in Arabidopsis. PLoS One 5, e8640 (2010).

Ju, C. L. et al. Conservation of ethylene as a plant hormone over 450 million years of evolution. Nat. Plants 1, 14004 (2015).

Hori, K. et al. Klebsormidium flaccidum genome reveals primary factors for plant terrestrial adaptation. Nat. Commun. 5, 3978 (2014).

Gallie, D. R. Appearance and elaboration of the ethylene receptor family during land plant evolution. Plant Mol. Biol. 87, 521–539 (2015).

Wuriyanghan, H. et al. The ethylene receptor ETR2 delays floral transition and affects starch accumulation in rice. Plant Cell 21, 1473–1494 (2009).

Ruggiano, A., Foresti, O. & Carvalho, P. ER-associated degradation: Protein quality control and beyond. J. Cell Biol. 204, 869–879 (2014).

Wu, X. & Rapoport, T. A. Mechanistic insights into ER-associated protein degradation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 53, 22–28 (2018).