Abstract

A better understanding of genetic architecture will help enhance precision medicine and clinical care. Towards this end, we investigate sex-stratified analyses for several traits in the Hybrid Mouse Diversity Panel (HMDP) and UK Biobank to assess trait polygenicity and identify contributing loci. By comparing allelic effect directions in males and females, we hypothesize that non-associated loci should show random effect directions across sexes. Instead, we observe strong concordance in effect direction, even among alleles lacking nominal statistical significance. Our findings suggest hundreds of loci influence each mouse trait and thousands affect each human trait, including traits with no significant loci under conventional approaches. We also detect patterns consistent with spurious widespread epistasis. These results highlight the value of sex-stratified analyses in uncovering novel loci, suggest a method for identifying biologically relevant associations beyond statistical thresholds, and caution that pervasive main effects may produce misleading epistatic signals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Complex traits are affected by many genetic variants that together influence their severity, presentation, and prevalence1,2. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have successfully identified many such variants for a broad range of complex traits. However, for many traits, there are important differences between males and females that may reflect underlying differences in their respective genetic architectures. Most association studies combine sexes in their analyses and adjust for sex as a covariate, but this approach can conceal differences that a sex-stratified approach can reveal. The likelihood that sex differences exist is consistent with the frequent sex differences often seen in disease prevalence, severity, age of onset, or outcomes3. For example, the prevalence of autism spectrum disorder is 4 times higher in males than females, mortality rates associated with COVID-19 infection are elevated in males, and females have double the likelihood of developing multiple sclerosis4,5,6. Although factors beyond genetics likely contribute to these gender differences, it is becoming increasingly clear that genetic factors, both autosomal and sex-linked, contribute to the sexually dimorphic effects seen for many complex traits and diseases. A better understanding of the sex differences underlying complex traits and diseases between males and females may improve the accuracy and efficacy of precision medicine-based clinical care, as well as reduce health care disparities resulting from the historical relative lack of attention given to women’s health issues.

Although sex is typically accounted for as a variable in sex-combined association studies, a number of studies in both humans and model organisms have successfully improved the identification of genetic variants associated with a range of complex traits and diseases by performing sex-stratified analysis or testing for Genotype x Sex interactions7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15. These studies have often identified associations between specific variants or loci and their respective phenotype that were otherwise not identified in a sex-combined analysis or in the analyses of the opposite sex. In one study comparing sex-specific and combined-sex analyses of major depression based on the UK Biobank datasets, sex-specific polygenic risk scores were better at predicting major depressive disorder than sex-combined polygenic risk scores, indicating the importance of considering sex in genomic analyses for precision-based medicine going forward14. Similar findings were observed with testosterone levels, interactions between polygenic risk scores and sex for a number of blood cell traits and coronary artery disease risk, and cognitive function based on a polygenic risk score for schizophrenia16,17,18,19. These studies highlight the importance of considering sex as an important variable, and in certain instances, performing sex-specific analyses of genetic data to identify variants associated with risk or calculating polygenic risk scores that do not transcend sex.

In addition to sexually dimorphic loci that are identified in sex-stratified genomic analyses, we reasoned that by comparing results in the two sexes, we can potentially better elucidate the genetic architecture of complex traits. Under the null hypothesis that GWAS variants with a p value larger than an arbitrary threshold (typically 5 × 10−8 in human studies) have no effect on a phenotype, the expectation is that there should be no relationship between the effects attributed to a particular variant in both independent male and female analyses. However, if there is a real biological association between a genetic variant and a given phenotype, then one would expect that these variants might be enriched for similar effects in separate male and female analyses relative to that expected by chance. Applying this comparison across all genetic variants can provide an additional means of estimating the true number of variants that contribute to trait heritability, independent of the arbitrary p value threshold for significance that is used in most GWAS studies. Recent proposals to modify p value thresholds, apply other measures of confidence, or even abandon p values, highlight the growing sense that p values alone are not reliable measures of biological significance and should instead be integrated with other information, such as prior knowledge, mechanistic support, and data quality20,21,22. Alternative methods of incorporating biological information into statistical thresholds for significance have also been proposed and include measures of biological function such as chromatin accessibility or enhancer status or interactions with promoter regions23,24, applying pathway-based approaches as opposed to single variant analyses25, machine learning algorithms to interpret GWAS results26, and simply relaxing significance thresholds27,28.

To examine the role of sex-specific analyses on the ability to detect associations between genotypic and phenotypic variation, as well as test the hypothesis that large-scale comparison between the sex-specific analyses could reveal novel insights into genetic architecture, we compared a series of sex-specific and sex-combined analyses on metabolic and blood-related traits in the Hybrid Mouse Diversity Panel (HMDP). Prior studies have had success detecting associations for a wide range of mouse complex traits utilizing the HMDP, a population of more than 100 inbred and recombinant inbred mouse strains designed to measure and identify the genetic and environmental factors underlying complex traits29. Compared to GWAS in humans, the HMDP better controls variation due to environmental factors, has many relevant tissues available for phenotyping, and the strains can be used for the integration of follow-up studies. The HMDP also provides an order of magnitude greater mapping resolution compared to traditional linkage analyses in mice29,30. As evidence of these advantages, use of the HMDP has successfully identified novel genes for a diverse array of traits, including obesity, diabetes, atherosclerosis, and heart failure, many of which have been validated using transgenic or knockout models29,31,32,33. In addition, previous studies of the HMDP using sex-specific analyses demonstrated an improved ability to identify novel loci related to metabolic disease8. Given the outstanding questions related to defining the genetic architecture of complex traits in both males and females, the HMDP represents a powerful tool for identifying specific variants that regulate complex traits in mice, as well as discovering more complex patterns of how genetic variation influences trait variation and disease susceptibility34.

In this study, we report a comparison between sex-stratified and sex-combined association analyses of several metabolic and blood traits using F1 mice from a cross between strain C57BL/6 J and strains from the HMDP. The male and female genotype and trait data were published by Bennett et al, but only a sex-stratified analysis of female mice was previously described35. The findings in this study demonstrate an improved ability for detecting associations in a sex-stratified analysis in the HMDP. Additionally, they indicate that hundreds of additional loci throughout the genome contribute to the genetic architecture of complex traits, far beyond those identified using conservative and arbitrary p value cutoffs, even for complex traits for which not even a single statistically significant locus was identified. To extend these findings to humans, the quantitative traits BMI and height, as well as the qualitative traits obesity and type 2 diabetes, were analyzed using data from the UK Biobank study36. Sex-stratified analyses of these traits were performed, analogous to the HMDP studies, to assess whether patterns of association transcend species.

Results

Heritability

To determine the additive and non-additive heritability components for a series of complex traits in the HMDP, narrow-sense and broad-sense heritability were calculated separately for male and female mice for 8 metabolic traits and 3 blood-related traits (Table 1). On average, the metabolic traits had higher heritability than the blood traits in both sexes. Broad sense heritability was greater than narrow sense heritability in males and females for all traits except adiposity in males. The heritability estimates differed between the two sexes for many of the traits. For example, the narrow sense heritability of adiposity was less in females (0.566) than in males (0.740), and the narrow sense heritability of body weight was larger in females (0.598) than in males (0.463). However, on average, heritability was similar between the sexes. That said, it is important to exercise caution when comparing heritability estimates, or genetic correlations as discussed below, between traits and sexes, given the relatively small sample sizes involved.

Genetic correlation of traits

Given that heritability estimates appeared to differ between sexes for some of the traits, sex-stratified genetic correlations were calculated to measure the genetic trait variability within and between sexes. The genetic correlations between pairs of all traits were first compared within each sex. The absolute value of the correlation between traits within the same sex was on average ±0.34 (SD = 0.23) in males and ±0.29 (SD = 0.21) in females. Related phenotypes were highly correlated in both sexes. For example, cholesterol and triglycerides were highly correlated in both males (0.88) and in females (0.65) and body weight and insulin were highly correlated in both males (0.63) and females (0.76) (Table S1). Some traits appeared more strongly correlated in one sex than the other. For example, fat mass and insulin were more correlated in females (0.83) than in males (0.43) (Table S1). Additionally, body weight and monocyte % were more correlated in males (0.52) than in females (0.13). Some traits were not correlated, such as adiposity and insulin in both males (−0.06) and females (−0.04). Additionally, adiposity and cholesterol were not correlated in either males (−0.02) or females (−0.08).

The genetic correlation of each trait was also calculated between male and female mice. The average of the absolute value of the correlations was 0.58 (SD = 0.22). Some traits had strong correlations across sexes, including body weight (0.88) and glucose (0.86) (Table S2). Other traits had much lower correlations across sexes, including HDL (0.17) and white blood count (0.35) (Table S2). While traits were on average more correlated across sexes than between traits of the same sex, some traits were more correlated to other traits within the same sex than to the same trait across sexes. For example, HDL is not very correlated across sexes (0.17) but is much more strongly correlated with triglycerides in males (−0.69) and with glucose in females (−0.46) (Table S2). A similar trend is seen for white blood count, where the trait is not very correlated between sexes (0.35) yet is highly correlated with insulin in males (−0.60) and with granulocyte % in females (−0.76) (Table S2).

Detection of loci with main effects

Given that the heritability estimates and genetic correlations underlying some metabolic traits were variable between males and females, main effects were determined using sex-stratified analyses. Main effect associations for eight metabolic traits were tested in females using 694 mice encompassing 98 strains from the HMDP. The Bonferroni-corrected threshold for significant main effects, based on the number of haplotype blocks and independent SNPs not within any of the haplotype blocks tested, was p < 4.13E-6. At this threshold, there were no significant main effects in females (Table 2). While we were unable to detect statistically significant main effects using a conservative Bonferroni threshold, we identified associations that were previously observed by Bennett et al. in this HMDP dataset35. That study used a slightly different strain composition and an FDR-based threshold for significance at p < 1.3E-535. Using the less conservative threshold, we replicated five unique SNPs in adiposity and 1 unique SNP in HDL that were discovered as significant in the Bennett et al. analysis (Table S3).

While these traits were previously analyzed in female mice by Bennett et al, the same traits were not analyzed in males. Thus, the main effects of the same eight metabolic traits were assessed in males using 664 mice from 102 strains from the HMDP. The Bonferroni-corrected threshold for significant main effects was based on the number of haplotype blocks and SNPs independent of the haplotype blocks tested. The main effect significance threshold was p < 2.89E-6. There were multiple significant main associations detected for adiposity (n = 58), body weight (n = 22), and fat mass (n = 60), which are the traits with the largest narrow-sense heritability among those studied (Table 2, Table S4). We also found an enrichment for main effects over that expected by chance (Table S5). As adiposity, body weight, and fat mass are highly related, we examined whether the significant SNPs overlapped between these traits. Overall, 20 haplotype blocks contained SNPs associated with all three traits. Thirty-five additional haplotype blocks contained SNPs associated with two of the traits, including thirty-three blocks associated with both adiposity and fat mass, 1 block associated with both adiposity and body weight, and 1 block was significantly associated with both body weight and fat mass (Figs. S1 and S2, Table S6). Only 10 haplotype blocks were unique to one of the three traits (Fig. S1, Table S6). Among the loci identified, there was little overlap with a similar analysis of the HMDP mice when fed a different obesogenic diet (Table S7)8, suggesting a strong Gene x Environmental component to the sex-specific loci identified in each study.

In addition to studies of metabolic traits, and to test the generalizability of any findings to complex traits more broadly, main effects for 3 blood-related traits were assessed in females using 670 mice encompassing 97 strains and in males using 640 mice encompassing 98 strains, using the HMDP. The Bonferroni-corrected threshold for significant main effects was again based on the number of haplotype blocks and SNPs outside of the haplotype blocks tested. The main effect significance threshold was p < 2.87E-6 in females and p < 2.91E-6 in males. At these thresholds, there were no significant main effects detected in either males or females (Table 2).

GWAS often only measure main effects using a sex-combined analysis with an adjustment for sex. Thus, in addition to the sex-stratified analyses, we also analyzed the HMDP data using a combined-sex approach to assess if similar or different main effects could be detected. Main effects for the 8 metabolic traits and three blood traits were assessed in the sex-combined analysis with both male and female samples, adjusting for sex as a variable in the regression analyses. The Bonferroni-corrected threshold for significant main effects was p < 2.87E-6, and thus similar to that for each of the sex-stratified analyses. At this threshold, there was one main effect locus detected for adiposity. However, this region was not one of the 58 loci detected in the male-only analysis. There were also six main effect loci detected for body weight, with four of these also observed in the male-only analysis. There were five main effect loci detected for fat mass, with four of these loci also observed in the male-only analysis. There was also one main effect locus detected for the blood trait granulocyte % that was not detected in the male-only analysis (Table 2). Thus, of the 13 total main effect loci detected in the sex-combined analyses, five were not also detected in the male-specific analysis. Conversely, among the 140 loci detected across all traits in the male-specific analyses, only eight were detected in the combined sex analyses (Table 2). These results indicate that the power to detect QTLs in the HMDP is diminished in sex-combined analyses that adjust for sex as a variable, rather than conducting separate sex-stratified analyses.

Normalization of trait data did not significantly alter QTL detection

Metabolic and blood traits were tested for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk’s method to measure if a non-normal distribution could be driving the male-specific main effects. Nearly every trait in both sexes was non-normally distributed (Table S8). Therefore, to test whether the significant loci identified above were artifacts due to a non-normal distribution of the trait data, phenotypes were normalized using both a rank-based normalization and a Box-Cox normalization. Performing QTL detection for adiposity using the rank-based normalized data resulted in the identification of 54 significant QTLs, whereas using the Box-Cox normalized data resulted in the identification of 63 significant QTLs. All but 1 of the rank-based normalized QTLs were also detected in the unadjusted model (Table S9). There were more Box-Cox significant QTLs detected than were found in the unadjusted model, but all of the QTLs detected based on the unadjusted data were also identified in the Box-Cox normalized data. Thus, there were nearly identical results, regardless of whether the regression analyses were performed on unadjusted or normalized trait data. In addition to these results for adiposity, similar findings were observed for all other traits studied for both the sex-stratified and sex-combined analyses (Table S9). Collectively, this demonstrates that the QTL mapping findings were robust to the transformation of the trait data.

Removal of outliers did not significantly alter QTL detection

In addition to testing whether normalization of the trait data significantly altered the QTL mapping studies, we sought to test whether the QTL detection results were being driven by either a few outlier mice or outlier strains of mice. To test this, outliers were removed from the phenotypic data that were greater than three standard deviations from the mean. Outliers were removed either by removing individual mice that met this criterion or removing strains that collectively met this criterion. When individual mouse outliers were removed from male mice, there were 35 adiposity main effects detected, and all 35 of these effects were previously found in the unadjusted male-only model (Table S9). For body weight, 24 significant main effects were detected, again, with all these loci already detected in the unadjusted male-only model (Table S9). There were 55 significant main effects detected for fat mass, with 53 of these effects detected in the unadjusted male-only model (Table S9). Of the traits that detected main effects in the unadjusted model, none of the adiposity traits (adiposity, body weight, or fat mass) had outlier strains that were removed due to their average strain values and the criteria described above. Insulin and granulocyte % had strain outliers, but both traits failed to detect QTLs using the unadjusted, normalized, or outlier-removed data. Thus, as with data normalization, removal of outliers had only minor effects on the detection of loci that control these metabolic traits in the HMDP.

Randomization of sex prevented detection of most sexually dimorphic QTLs

After applying various quality control measures to the trait data in the HMDP prior to QTL detection, one of the most striking findings, which was robust to these modifications, was the difference in the number of QTLs that associate with adiposity-related traits in male mice relative to the lack of QTLs identified that associate with adiposity-related traits in female mice. This was surprising, as the overall heritability across all three of the adiposity traits appeared similar between males and females, and the traits were highly genetically correlated across sexes (0.55–0.88) (Table S2). Thus, to test the robustness of these findings, the sex of each mouse was randomized as either a male or a female and the linear regression analysis was performed again. Adiposity was analyzed as it had the largest average narrow-sense heritability across sexes (0.653) (Table 1). Main effects were detected for adiposity, with sex randomly assigned for 100 permutations. Among the 100 permutations, there were few instances where significant main effects were detected in either females (mean = 0.41, SD = 2.04, range = 0,17) or males (mean = 0.79, SD = 2.06, range = 0,13) (Table S10), indicating that the sex-specific QTLs were not likely to be artifacts, but instead represented true sexual-dimorphic QTLs.

Concordant directionality of main effects in male and female mice

Despite the increased number of significant main effects detected in males relative to females, the overall correlation of all beta values between males and females were nonetheless significantly positive for all of the metabolic and blood traits in the HMDP, with a mean correlation of r = 0.4182 (range: 0.2549 (HDL)–0.6015 (glucose)) (Table 4) (Figs. S3 and S4). Thus, we wondered whether genetic associations in females had the same direction of effect on each trait as that detected in males, even if they did not reach the level of statistical significance in females. For example, SNP rs48316748 was the most significant SNP associated with body weight in male mice in the HMDP (p = 1.27E-11, Beta = 2.94), with the “A” allele being associated with increased body weight. The “A” allele at this SNP was also associated with an increase in body weight in the analysis of body weight in females, although the p value was not statistically significant (p = 0.11, Beta = 0.74) (Fig. S5). In contrast, SNP rs36473704 was associated with a positive beta value of 0.16 in males (p = 0.67) but was associated with a negative beta value of −0.40 (p = 0.30) in females. As such, SNP rs48316748 had a concordant direction of effect in males and females, whereas SNP rs36473704 was not concordant for direction of effect between the sexes. To test the concordance of direction of effect among statistically significant loci, the direction of effect of each SNP was assessed in each sex and compared. If there were no effects shared between male and female mice, the null hypothesis is that the direction of effects in the two sexes should be the same ~50% of the time, based on the equivalence of random effects. However, among two of the three traits for which significant main effects were detected in males (body weight and fat mass), the allelic direction of effect was the same in males and females significantly more frequently than by chance alone (Table 3). The enrichment in the number of significant main effects with the same allelic direction of effect was significant in body weight (p = 4.20E-8) and fat mass (p = 0.003) but not in adiposity (p = 0.22) (Table 3). Therefore, although the significant main effects may not be statistically significant in both sexes, they nonetheless had a consistent effect direction in both male and female mice (Table S11).

To extend these findings beyond the loci with p values that met the conservative Bonferroni-adjusted threshold for significance, we next tested whether the direction of effects was similar in males and females for all main effects tested, regardless of statistical significance. Concordance between males and females was analyzed and sorted based on the p value for association in males. Male p values were used as all significant main effects were detected in males. For all traits examined, the percentage of loci with effects in the same direction in males and females was far greater than the 50% expected by chance (Fig. 1A, B) across nearly all levels of statistical significance. The enrichment relative to chance was greatest among the most significant loci and decreased towards the 50% expected by chance as the male p values increased, asymptotically approaching 50% as p values approached 1.

The percentage of all HMDP main effect loci with consistent direction of effects in the two sexes was plotted according to the male-derived p values. Main effect p values > 0.95 were excluded due to many low-frequency alleles. Directionality was determined using the sign of the effect size of each main effect locus. The phenotypes measured included A metabolic traits, B blood traits, and C simulated phenotypes (n = 10 simulations per group) using an increasing number of “causal” SNPs. Error bars were calculated using ggplot2 as mean values ±standard deviation.

To test whether the effect size of each locus demonstrated a similar enrichment of concordance among larger effect sizes than smaller effect sizes, we similarly compared the concordance between the directions of effects in male and female mice for each SNP grouped by their absolute beta value. Similar to grouping by p value, SNPs with larger absolute beta values were more likely to be concordant between males and females, with the enrichment again seen not just for SNPs with the largest beta values, but seen in most of the groups of beta values, with diminishing concordance rates until the lowest beta values at which point the concordance rates approached random assortment (Fig. 2).

The percentage of all HMDP main effect loci with consistent direction of effects in the two sexes was plotted according to the male-derived beta values. Directionality was determined using the sign of the beta value of each main effect locus. Values were graphed by decile according to the absolute value of the beta value. The phenotypes measured included A metabolic traits and B blood traits.

To estimate the number of SNPs with heritable effects on a given trait that would be consistent with the observed enrichment of greater than 50% of loci with effects in the same direction in males and females, phenotypes were simulated based on the exact HMDP genotypes. Phenotypes were simulated with a heritability of 0.4 to approximate the heritability of the metabolic traits (Table 1). To recapitulate the independent analysis of male and female mice, all SNPs in the simulation were assigned an artificial beta value. For SNPs defined as having a “true” causal effect that was consistent in both male and female mice, these SNPs were assigned beta values in the same direction (i.e., both positive or both negative) in both the male and female simulations. To simulate a SNP with no causal effect, beta values were randomly assigned separately in the male and female analyses and were thus on average in the same direction 50% of the time. Phenotypes were simulated with a range of “causal” SNPs, from a minimum of zero causal SNPs to a maximum where half of the total number of SNPs are estimated as causal (n = 10,998). After independently simulating the phenotype data under each of these conditions 10 times, linear regression analyses were performed on each of the 10 simulations as was done for the actual trait data.

As expected, in the absence of any “causal” SNPs in the simulation, there was no enrichment of male and female concordance above the 50% expected by chance (Fig. 1C). In contrast, when at least 100 “causal” SNPs were included in the model, a clear increase in the percentage of concordant effects in males and females was detected relative to the 50% expected by chance (Fig. 1C). Comparing the results from the real phenotype data to the results from the simulated phenotypic data, the metabolic and blood traits likely include between 200 and 1100 SNPs with a true main effect (Fig. 1). These data demonstrate that the main effects detected for many loci throughout the genome, even though they do not reach the conservative p value threshold for significance, are not simply random noise and instead indicate that these loci are in fact contributing to trait heritability via their main effects.

Phantom detection of loci with interaction effects

Given the strengths of using male/female concordance to estimate the number of contributing loci compared to a conservative Bonferroni threshold for significance, we wanted to assess whether this could be applied to SNP-SNP interactions, as the role of epistasis in complex traits remains controversial37,38,39. Replicating the methods described for main effects, we tested whether the direction of effects was similar in males and females for all pairwise interactions analyzed, regardless of statistical significance. Concordance between males and females was measured and sorted based on the p value for association in males. For all traits examined, the percentage of loci with effects in the same direction in males and females far exceeded the ~50% expected by chance across nearly all levels of statistical significance (Fig. 3A, B). As seen with the main effects, enrichment of concordant interactions relative to chance was greatest among the most statistically significant interactions and decreased towards the 50% expected by chance as the p values increased, asymptotically approaching 50% as p values approached 1. To evaluate the number of genome-wide pairwise interactions consistent with these findings, we again turned to the simulations of phenotypic data. Given the estimate that at least 200 main effects contribute to the heritable regulation of each trait, we applied that model of genetic architecture to the detection of genetic interactions. For comparison, we also modeled the effects of zero main effects as a negative control, and >10,000 main effects as a likely overestimation. Importantly, the genetic architecture simulated by the model included only main effects and did not include any simulated interactions. Thus, if analysis of this simulated genetic architecture appropriately failed to detect interactions, it would support the validity of widespread interactions as indicated by the elevated concordance of the male/female direction of effects. However, if the simulated genetic architecture, which included only main effects and no interactions, recapitulated the elevated concordance of the male/female direction of interaction effects, it would indicate that these findings were artifacts of the widespread main effects and did not represent true interactions.

The percentage of all HMDP pairwise interacting loci with consistent direction of effects in the two sexes was plotted according to the male-derived p values. Interaction p values > 0.95 were excluded due to many low-frequency alleles. Directionality was determined using the sign of the Beta value for each interaction. The phenotypes measured included A metabolic traits, B blood traits, and C simulated phenotypes (n = 10 simulations per group) using an increasing number of “causal” SNPs. Error bars were calculated using ggplot2 as mean values ±standard deviation.

As expected, when no main effects and no interactions were included in the model, there was no overrepresentation of male/female concordance for interactions relative to chance. However, when 200 main effects, but no interactions, were included in the model the male/female concordance rate for interactions was far greater than the 50% expected by chance, mirroring the results from the actual HMDP data (Fig. 3C). As the simulated data including only main effects had a pattern similar to the actual data, it is consistent with an interpretation that the interaction results were artifacts due to the widespread underlying main effects. There may nonetheless be some epistatic interactions contributing to the phenotype, as the broad sense heritability was higher than the narrow sense heritability, but we were unable to detect the signature of widespread interactions analogous to that which was detected for the main effects.

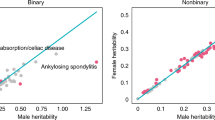

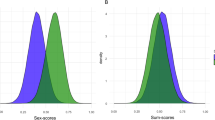

Concordant directionality of main effects in humans

To test whether the increased frequency of condordant directionality was also observed in human data, as it was in the HMDP (Figs. 1 and 2), we performed an analogous comparison of both quantitative and qualitative traits from the UK Biobank study36. The quantitative traits BMI and height were analyzed in 219,777 males and 260,528 female individuals. The qualitative trait of obesity (BMI < 30 vs. BMI ≥30) was analyzed in 163,248 control and 55,517 obese males and 198,564 control and 61,027 obese females, whereas type 2 diabetes (HbA1c < 5.8 vs. HbA1c > 6.5) was analyzed in 166,303 control and 5571 diabetic males and 199,924 control and 5682 diabetic females. As was detected in the HMDP, the correlation of all beta values between males and females was again significantly positive, with a correlation of r = 0.3653 for BMI and r = 0.5760 for height (Table 4) (Fig. S6). In addition, concordance rates between males and females were again significantly elevated relative to that expected by chance, with the highest concordance rates again observed among the most statistically significant loci, and with levels again asymptotically approaching 50% as the p values approached 1 (Fig. 4A). The concordance rates were significantly higher in the quantitative traits relative to the qualitative traits (Fig. 4A), as expected given the loss of information and statistial power associated with transforming a continuous variable to a dichotomous trait40. In addition to sorting by p value, concordance rates were also sorted by absolute beta value, and as was seen in the HMDP, when sorting by p values, concordance rates were significantly elevated relative to chance, particularly with the largest beta values, with concordance rates decreasing towards 50% as the beta values approached zero (Fig. 4B).

The percentage of all UK Biobank main effect loci with consistent direction of effects in the two sexes was plotted according to the male-derived p values. Main effect p values > 0.95 were excluded due to many low-frequency alleles. Directionality was determined using the sign of the effect size of each main effect loci. Phenotypes measured included BMI, height, obesity, and type 2 diabetes and are A sorted by male p values, or B sorted by absolute male beta values. C Simulated phenotypes (n = 10 simulations per group) using an increasing number of “causal” SNPs.

We also performed simulation studies to estimate the likely number of loci contributing to the regulation of BMI based on these concordance rates. The negative control experiment, with no simulated main effect loci, as expected demonstrated no enrichment of concordance at any p value (Fig. 4B). The simulation that most closely matched the actual BMI UK Biobank data was the one where one-third of all tested loci contained a main effect (Fig. 4B), consistent with tens of thousands of loci across the genome contributing to the regulation of this trait. The number of contributing loci with main effects is significantly higher than that estimated from the HMDP mouse data (Fig. 1C), likely due to the increased power obtained using hundreds of thousands of individuals compared to just hundreds of mice, although species differences in genetic architecture cannot be ruled out. Nonetheless, these analyses indicate that an order of magnitude more loci are contributing to the regulation of BMI and other complex traits relative to those identified as statistically significant using similarly sized populations41 and are instead more consistent with a genetic architecture estimated by GWAS using more than 10× the number of samples42.

Given the potential to more accurately estimate the number of loci regulating complex traits relative to standard GWAS mapping paradigms, we sought to test whether the same methodology could be used for traits with reduced sample sizes, which is often the case relative to the easily attainable measurements of height and BMI. To test the impact of reduced sample sizes, and therefore reduced statistical power, on the patterns of male/female concordance for a complex trait, we randomly downsampled the number of individuals from the UK Biobank BMI dataset prior to testing for concordance in the direction of effect between the beta values (Fig. 5). A sample size roughly half that of the UK biobank (~230 K combined male and female individuals) still detected roughly the same pattern of concordance bewteen males and females as the full dataset, whereas the concordance rates were much lower when one-quarter (~120 K individuals) or even more so one-tenth (~47 K individuals) of the dataset was used. This suggests that applying this methodology to the analysis of complex traits is dependent on sample sizes and statistical power, although it can nonetheless be applied to smaller sample sizes, albeit with a reduced ability to detect concordant loci between the sexes.

The percentage of all UK Biobank main effect loci for BMI with consistent direction of effects in the two sexes was plotted according to the male-derived p values. Samples were randomly downsampled to simulate smaller sample sizes. Main effect p values > 0.95 were excluded due to many low-frequency alleles. Directionality was determined using the sign of the effect size of each main effect loci.

Discussion

In the current study, we utilized the HMDP to measure the sex-specific heritability of several metabolic and blood traits. As expected, broad sense heritability was higher than narrow sense heritability across almost all traits and in both sexes, indicating a contribution from dominance or non-additive factors to total heritability. However, the additive component always comprised a majority of the total heritability. The contribution of non-additive or dominance factors to total heritability is consistent with many prior studies, as is the smaller contribution relative to additive effects35,43,44,45,46. It is worth noting that adiposity, body weight, and fat mass, the traits for which significant main effects were identified in males, exhibited the highest levels of narrow-sense heritability relative to all other traits. As main effects were detected in males only for these three traits, it is unsurprising that the narrow-sense heritability was greater in males than in females for adiposity and fat mass. Surprisingly, the narrow sense was greater in females than in males for body weight. This indicated there could be genetic differences underlying body weight that differ by sex.

The underlying genetic differences of metabolic and blood traits were further studied through the genetic correlation of traits across sexes and between traits within a single sex. Body weight was highly correlated across sexes, but adiposity and fat mass were less strongly correlated. Interestingly, some traits appeared more strongly correlated with another trait within the same sex than with the same trait in the other sex. Thus, the genetic makeup of some traits may be more closely related to other phenotypically related traits in the same sex. We therefore speculate that there are substantial genetic differences regulating some traits across sexes.

This study aimed to better understand the pervasive role of sex-dependent main effects in the underlying genetic architecture. Studies were performed using standard linear regression analyses and simulated phenotypes to identify significant main associations and non-additive epistatic interactions, and many such loci were discovered (Table 2). Normalization, randomization, and simulation studies all supported the finding of many more main associations in males relative to females. The simulation studies were key to determining the number of loci that were likely causative. The fact that we find many more SNPs that are concordant in the real data as compared to simulations may indicate that some of the concordant SNPs are themselves not causal but are in LD with those that are, as seen in virtually all other association studies.

The simulated phenotype analyses also indicated that detected epistatic interactions were likely the result of spurious signals from main effects mimicking an interaction, as has been previously reported47,48,49. Nonetheless, the higher broad sense heritability estimates relative to narrow sense are still consistent with a non-additive contribution, albeit given the statistical difficulties in detecting interactions, functional studies will be needed to discover such interaction effects.

Many detected main effects were sex-dependent as they were detected in analyses of male mice only, but were undetected in females alone or sex-combined analyses. Prior human GWAS have detected sex-dependent main effects for depression phenotypes14, apical periodontitis50, Behçet’s disease51, and blood pressure15. The sex-dependent nature of the significant main effects in our studies was further supported by randomizing sex in the analyses, which abolished the associations, providing an important control for spurious findings in the sex-specific analyses. Nonetheless, the significant main effects in males largely had the same direction of effect in females. This pattern was seen beyond the statistically significant loci, and thus, numerous possible small but likely real main effects were detected for each trait. The detection of many main effects likely contributing to the genetic architecture echoes previous findings of widespread genetic effects2, although a different statistical method was used, different traits were examined, and a different organism was studied. Thus, it is perhaps not surprising that analysis of BMI and height, and to a lesser extent obesity and type 2 diabetes, in humans demonstrated similar findings as the complex traits analyzed in the HMDP. Together, the results support the robustness of a highly polygenic model as a key feature in the genetic architecture of most, if not all, complex traits. It is also important to consider that the mice analyzed were all F1 mice from crosses between C57BL/6J and the HMDP strains. This somewhat limits the variation present, as alleles within the HMDP strains were all fixed in the heterozygous state; thus, it is expected that the loci identified underestimate the potential number of loci regulating each trait, given that HMDP alleles were not studied in the homozygous state. In addition, it is expected that if statistical power were further increased in the HMDP with the inclusion of additional strains and replicates, to more closely approximate the UK Biobank studies, the number of detected loci may yet be higher, potentially approaching omnigenic inheritance.

Accounting for the highly polygenic, or potentially omnigenic, nature of the genetic architecture may be important for improving the modeling of trait heritability in complex traits driven by many genetic associations. The incorporation of many loci may improve the ability to predict disease risk via more accurate polygenic risk scores (PRS) that account for variability accounted for by sex. As argued previously, we suggest PRS can be used to efficiently model the complex traits using many main effects52. As we detected between two hundred and ~1000 SNPs to have a main effect in mice and many thousands more in humans, we propose a method to better define the possible PRSs beyond just effect sizes and statistical significance by empirically estimating the number of SNPs to be included. We suggest that the number of SNPs should be determined by comparing male/female concordance from real data to simulated data, as we have shown in Fig. 4. We would argue that this is likely more robust than using just an arbitrary p value or effect-size cutoff. In the HMDP study, we were able to detect these polygenic effects with only 700 mice from each sex, and in the UK Biobank, these effects were detected using only a fraction of the total samples, although the power did diminish as the sample size was reduced. Thus, this method may be successful in studies of limited sample sizes, including studies with reduced statistical power. Using the top main effects, as determined either by statistical significance or by effect size, that fall within the number of variants suggested to contribute based on male/female concordance rates, is an additional method that could more accurately model the contribution of main effects in complex traits, regardless of sample size.

Our study had a few limitations. First, we recognize the limited diversity in the HMDP, although it is still better than most comparable mouse studies. Also, as noted above, all of the mice were F1s crossed with C57BL/6J, which may limit the generalizability. However, the human studies did not suffer from this limitation, and the overall results were still quite similar. For both the mouse and human studies, we only examined a limited number of traits that were either metabolic or blood-related. Hence, we cannot extrapolate with a high degree of confidence to unrelated traits. Finally, while we still think that the findings are noteworthy, we cannot explain the substantial difference in the significant association between males and females. Although it is well-known that male mice respond more strongly to obesogenic environments53, we recognize that our results warrant further explicit examination.

In conclusion, we present a relatively simple analysis applied to the HMDP and UK Biobank to detect poly- and perhaps omnigenic main effects regulating several correlated and uncorrelated complex traits, even for those traits that lacked any statistically significant main effects. This indicates that many loci spanning the genome are likely contributing to trait heritability and strongly argues that current conservative p value thresholds may not be the best means to approach association studies. Integration of this polygenic model may lead to more accurate genetic models for the most complex traits, for which current models fail to account for most heritability and similarly fail to accurately predict trait outcomes based on polygenic risk scores in distinct and diverse populations43,44,46,54,55,56. The results also indicate that there are likely multiple sex-dependent genetic effects/architectures that sex-combined analyses, even adjusting for sex, cannot detect. Therefore, future studies may more effectively model a trait’s heritability and complex genetic architecture by performing sex-dependent analyses as well as including the many main effects that play a role in heritability but are not statistically significant. With a more comprehensive understanding of the many main effects required to model genetic architecture, a clearer understanding of disease etiology will hopefully be achieved for many complex traits. Continued advances towards a better understanding of the genetic architecture of complex traits and diseases promise to improve disease risk prediction, help unravel disease pathophysiology, and guide the use of personalized medications and treatments with improved precision.

Methods

This research complies with all relevant ethical regulations. This research has been conducted using the UK Biobank Resource under Application Number 61255. All animal work was conducted according to relevant national and international guidelines and was approved by the UCLA Animal Research Committee, the UCLA IACUC.

Mice

The HMDP genotype and trait data are from Bennett et al. and included 8 metabolic traits (adiposity, body weight, cholesterol (unspecified), fat mass, glucose (unspecified), HDL, insulin, and triglycerides) and 3 blood traits (granulocyte %, monocyte %, and white blood count) and were obtained from the Mouse Phenome Database (https://phenome.jax.org/)35,57. These traits were selected for analysis because they had the largest sample sizes available among all HMDP datasets. Males and females were analyzed both separately (Fig. S7) and in a sex-combined analysis. A total of 694 female mice from 98 strains and 664 male mice from 102 strains were used in the metabolism trait analyses. Strain BXD24/TyJ-Cep290<rd16 > /J was removed from both male and female analysis as it carries a mutation that affects vision58, and four additional strains were removed due to missing phenotype or genotype data (Table S12). The female analyses also excluded strain BXD29-Tlr4<lps-2J > /J, and the male analyses excluded strains AXB13/PgnJ and NON/ShiLtJ due to missing phenotype or genotype data (Table S12)35. The blood trait analyses used 97 strains and 670 female mice and 98 strains and 640 male mice. Both the female blood trait and metabolism trait analyses used the same strains. The male blood trait strains were the same as the male metabolism strains except for three fewer strains (BXD31/TyJ, BXD6/TyJ, and CXB8/HiAJ were excluded) (Table S12).

Genotype analysis

The HMDP strains were previously genotyped using the Mouse Diversity Genotyping Array57. The number of genotyped SNPs in females was 200,885, and in males was 199,910 (Table S13)35. These genotype data excluded multiallelic SNPs; thus, only biallelic SNPs were included in these numbers and used in the analysis. SNPs were further pruned from the HMDP data using the PLINK linkage disequilibrium (LD)-based SNP pruning command using an R2 of 0.859 (Table S13). Haplotype blocks were calculated in PLINK from the remaining SNPs using a max block size of 15,000 kb59. For the female metabolic traits, 12,221 haplotype blocks plus 2314 SNPs located outside of any blocks were used in the analysis. For the male metabolic traits, 11,385 haplotype blocks plus 5907 SNPs located outside of blocks were used in the analysis (Table S3). For the female blood traits, 12,193 haplotype blocks plus 5221 SNPs located outside of blocks were used for analyses. For the male blood traits, 11,437 haplotype blocks plus 5752 SNPs located outside of blocks were used in the analysis (Table S13). The total number of haplotype blocks and SNPs for each trait was used to calculate the Bonferroni significance thresholds for female metabolism main effects (3.44E-6), male metabolism main effects (2.89E-6), female blood main effects (2.87E-6), and male blood main effects (2.91E-6). When determining significant main associations within a haplotype block, only the SNP with the most significant p value within the block was used. Similarly, when estimating the direction of effect for pairwise interactions between haplotype blocks or SNPs outside of the haplotype blocks, only the most significant SNP-SNP interactions within a block were considered. The thresholds for significance applied to main effects varied between this analysis and that of Bennett et al., due to the different number of strains analyzed and the FDR-based threshold previously used as opposed to the Bonferroni-based threshold in this study35.

In the sex-combined analyses, SNPs were removed that were not present in both male and female genotype data (1773) or had a differing minor allele (3922). After removing these SNPs, LD pruning was performed as described above. The sex-combined metabolic and blood traits had 22,284 SNPs remaining, resulting in 12,229 haplotype blocks with 5129 SNPs located outside of the blocks (Table S13). The total number of haplotype blocks and SNPs outside of the blocks was used to calculate the Bonferroni significance threshold for combined main effects (2.87E-6).

Statistical analysis (HMDP)

Trait heritability was estimated using two approaches, “narrow sense heritability” and “broad sense heritability”60. Narrow sense heritability, which refers to heritability due to additive genetic variance, was calculated using the Genome-wide Complex Trait Analysis (GCTA) software61. It estimates the proportion of phenotypic variance explained by all genome-wide SNPs for a complex trait, and the narrow-sense heritability estimate is based on sharing genomic regions identical by descent61. Broad sense heritability, which includes not only additive effects but dominance and other non-additive effects as well61, was calculated using the R package “heritability” and was estimated via reproducibility of trait measures in individuals of the same strain62.

The genetic correlation for trait data between and within sexes was estimated using GRM and GREML in the Genome-wide Complex Trait Analysis (GCTA) program61. GRM estimates the genetic relatedness from SNPs, and GREML estimates the variance explained by the SNPs in the GRM61. The reml-bivar command was used to compare the variance explained by the SNPs in the GRM for each trait across sexes. It also compared across traits within the same sex, comparing two traits at a time.

FaST-LMM (version 0.6.1), a linear mixed model method that accounts for population structure, was used for single locus main effects and pairwise interaction association tests63. A kinship matrix was constructed for the SNPs on all chromosomes except the one being tested to improve power and allow main effect SNPs to be tested only once for association in the regression equation. Not every main effect and interaction was measured in both sexes, as differences in haplotype block structure excluded different SNPs. Both interchromosomal and intrachromosomal SNP-SNP interactions were calculated63. FaST-LMM calculated the effect size for each SNP as the fixed-effect weight for main effects and as the Beta for each SNP-SNP interaction for epistasis tests63. The enrichment of associations identified at p value < 0.05 was calculated using chi-square tests.

The normality of all phenotypes was measured using the Shapiro–Wilk’s method via the R package “stats” (version 3.6.2). All phenotypes were rank-normalized using the R package “RNOmni” (version 1.0.0). Trait data was also Box-Cox normalized using the R package “bestNormalize” (version 1.8.3)64. Outliers were removed using two metrics: removing individual mice outside of 3 standard deviations away from the mean and strain averages outside of 3 standard deviations away from the mean.

GCTA was also used to simulate the phenotypic data61. The simulated phenotypes were calculated with a heritability of 0.4, similar to the heritability of the metabolic trait data for male and female mice (Table 1). Each simulation was performed separately for males and females to mimic the sex-specific analyses performed with the real HMDP data. Within the genotype data, we modeled SNPs as causal or having no effect. Beta values were assigned to both categories of SNPs. Causal SNPs were assigned a beta value that was identical in both size and direction in the independent male and female simulations. SNPs modeled to have no effect were randomly assigned a normally distributed beta value in each of the male and female simulations, with no link between these separate analyses as to the direction or magnitude of the effect for a given SNP. To mirror the effect sizes detected in the real trait data, the SNPs considered to have no effect were assigned an average beta value of ±0.2, while the SNPs considered to have a causal effect were assigned an average beta value of ±3.0. The number of causal SNPs that were simulated ranged from zero to half of all SNPs and included the following sets of causal SNPs: half, one-fourth, one-eighth, one-twentieth, 200, 100, 50, 10, and 0. For the simulations where zero SNPs were considered causal, no beta values were included in the simulation, so that they were again randomly assigned in each of the male and female simulations. Interactions were tested using simulated data based on either half, two hundred, or zero SNPs considered as causal for a main effect, with no true interactions modeled in the simulated data. Each phenotype simulation and analysis of main effects and interactions was repeated 10 times.

Sex-stratified main effect analyses were also analyzed with sex randomized, using 100 permutations. In each permutation, the number of males and the number of females were consistent in each analysis, as there were more female mice than males. Randomization was performed in R using the transform command in base R (version 3.6.2).

Statistical analysis (UK Biobank)

UK Biobank genetic data, as well as height, BMI, and HbA1c clinical trait data, were obtained from the UK Biobank data repository. Obesity was calculated from the BMI data and defined in accordance with the Centers for Disease Control guidelines as a BMI ≥30, with controls defined as a BMI<30. Type 2 diabetes was defined in accordance with the American Diabetes Association guidelines from the HbA1c data and was defined as HbA1c > 6.5, with controls defined as HbA1c < 5.7. Trait data were rank-normalized in R. Quality control was run on males and females separately, consisting of removing non-biallelic variants, LD greater than 0.8, individuals with missing genotype data >2%, genotype missing data greater than 5%, Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium p values less than 10E-5, and variants present in both males and females. The complete dataset for BMI and height consisted of 219,777 males and 260,528 females. The complete dataset for obesity consisted of 163,248 controls and 55,517 obese males and 198,564 controls and 61,027 obese females. The complete dataset for type 2 diabetes consisted of 166,303 control and 5571 diabetic males and 199,924 control and 5682 diabetic females after removal of outlier samples with an HbA1c value greater than 2 standard deviations from the mean. Downsampling of the BMI dataset was performed separately for males and females using the random sample without replacement option in R.

FAST-LMM was used to detect main effects. To both limit computational resources and more closely mirror the HMDP studies, every 10th variant was included in the analysis for a total of 12,866 SNPs. GCTA was used to simulate the phenotypic data61. The simulated phenotypes were calculated with a trait heritability of 0.248, based on the heritability estimates for BMI obtained from the website http://www.nealelab.is/uk-biobank/. SNPs were modeled as either causal or having no effect using the same procedure as described for the HMDP data. SNPs classified as causal were randomly assigned a normally distributed average beta value of ±0.0235, which was identical in both size and direction in both the male and female simulations. SNPs classified as no effect were randomly assigned a normally distributed average beta value of ±0.0071 in each of the male and female simulations, with no link to the direction or magnitude between the sexes. The proportion of causal SNPs simulated included one-half, one-third, one-quarter, and zero.

Data availability

All genetic and phenotypic data for the HMDP was obtained from the Mouse Phenome Database (https://phenome.jax.org/). All genetic and phenotypic data for the UK Biobank was obtained from the UK Biobank data repository (https://ukbiobank.ac.uk).

References

Fu, W., O’Connor, T. D. & Akey, J. M. Genetic architecture of quantitative traits and complex diseases. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 23, 678–683 (2013).

Boyle, E. A., Li, Y. I. & Pritchard, J. K. An expanded view of complex traits: from polygenic to omnigenic. Cell 169, 1177–1186 (2017).

Khramtsova, E. A., Davis, L. K. & Stranger, B. E. The role of sex in the genomics of human complex traits. Nat. Rev. Genet. 20, 173–190 (2019).

Pradhan, A. & Olsson, P.-E. Sex differences in severity and mortality from COVID-19: are males more vulnerable?. Biol. Sex. Differ. 11, 53 (2020).

Walton, C. et al. Rising prevalence of multiple sclerosis worldwide: Insights from the Atlas of MS, third edition. Mult. Scler. Houndmills Basingstoke Engl. 26, 1816–1821 (2020).

Zeidan, J. et al. Global prevalence of autism: a systematic review update. Autism Res. J. Int. Soc. Autism Res. 15, 778–790 (2022).

Nuzhdin, S. V., Pasyukova, E. G., Dilda, C. L., Zeng, Z. B. & Mackay, T. F. Sex-specific quantitative trait loci affecting longevity in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 9734–9739 (1997).

Parks, B. W. et al. Genetic architecture of insulin resistance in the mouse. Cell Metab. 21, 334–347 (2015).

Graham, S. E. et al. Sex-specific and pleiotropic effects underlying kidney function identified from GWAS meta-analysis. Nat. Commun. 10, 1847 (2019).

Nievergelt, C. M. et al. International meta-analysis of PTSD genome-wide association studies identifies sex- and ancestry-specific genetic risk loci. Nat. Commun. 10, 4558 (2019).

Choquet, H. et al. A large multiethnic GWAS meta-analysis of cataract identifies new risk loci and sex-specific effects. Nat. Commun. 12, 3595 (2021).

Johnston, K. J. A. et al. Sex-stratified genome-wide association study of multisite chronic pain in UK biobank. PLoS Genet. 17, e1009428 (2021).

Ciesielski, T. H. et al. Late-onset neonatal sepsis: genetic differences by sex and involvement of the NOTCH pathway. Pediatr. Res. 93, 1085–1095 (2023).

Silveira, P. P., Pokhvisneva, I., Howard, D. M. & Meaney, M. J. A sex-specific genome-wide association study of depression phenotypes in UK biobank. Mol. Psychiatry 28, 2469–2479 (2023).

Yang, M.-L. et al. Sex-specific genetic architecture of blood pressure. Nat. Med. 30, 818–828 (2024).

Flynn, E. et al. Sex-specific genetic effects across biomarkers. Eur. J. Hum. Genet.29, 154–163 (2021).

Koch, E. et al. Sex-specific effects of polygenic risk for schizophrenia on lifespan cognitive functioning in healthy individuals. Transl. Psychiatry 11, 520 (2021).

Xu, Y. et al. Machine learning optimized polygenic scores for blood cell traits identify sex-specific trajectories and genetic correlations with disease. Cell Genomics 2, None (2022).

Surakka, I. et al. Sex-specific survival bias and interaction modeling in coronary artery disease risk prediction. Circ. Genom. Precis. Med. 16, e003542 (2023).

Wasserstein, R. L. & Lazar, N. A. The ASA statement on p-values: context, process, and purpose. Am. Stat. 70, 129–133 (2016).

McShane, B. B., Gal, D., Gelman, A., Robert, C. & Tackett, J. L. Abandon statistical significance. Am. Stat. 73, 235–245 (2019).

Hirschauer, N., Grüner, S. & Mußhoff, O. The p-value and statistical significance testing. In Fundamentals of Statistical Inference 63–96 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-99091-6_6. (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2022).

Kichaev, G. et al. Leveraging Polygenic Functional Enrichment to Improve GWAS Power. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 104, 65–75 (2019).

Hammond, R. K. et al. Biological constraints on GWAS SNPs at suggestive significance thresholds reveal additional BMI loci. eLife 10, e62206 (2021).

White, M. J. et al. Strategies for pathway analysis using GWAS and WGS data. Curr. Protoc. Hum. Genet. 100, e79 (2019).

Kolosov, N., Daly, M. J. & Artomov, M. Prioritization of disease genes from GWAS using ensemble-based positive-unlabeled learning. Eur. J. Hum. Genet.29, 1527–1535 (2021).

Williams, S. M. & Haines, J. L. Correcting away the hidden heritability. Ann. Hum. Genet. 75, 348–350 (2011).

Chen, Z., Boehnke, M., Wen, X. & Mukherjee, B. Revisiting the genome-wide significance threshold for common variant GWAS. G3 Bethesda Md. 11, jkaa056 (2021).

Lusis, A. J. et al. The Hybrid Mouse Diversity Panel: a resource for systems genetics analyses of metabolic and cardiovascular traits. J. Lipid Res. 57, 925–942 (2016).

Bennett, B. J. et al. A high-resolution association mapping panel for the dissection of complex traits in mice. Genome Res. 20, 281–290 (2010).

Farber, C. R. et al. Mouse genome-wide association and systems genetics identify Asxl2 as a regulator of bone mineral density and osteoclastogenesis. PLoS Genet. 7, e1002038 (2011).

Orozco, L. D. et al. Unraveling inflammatory responses using systems genetics and gene-environment interactions in macrophages. Cell 151, 658–670 (2012).

Parks, B. W. et al. Genetic control of obesity and gut microbiota composition in response to high-fat, high-sucrose diet in mice. Cell Metab. 17, 141–152 (2013).

Rau, C. D. et al. Modeling epistasis in mice and yeast using the proportion of two or more distinct genetic backgrounds: evidence for “polygenic epistasis”. PLOS Genet. 16, e1009165 (2020).

Bennett, B. J. et al. Genetic architecture of atherosclerosis in mice: a systems genetics analysis of common inbred strains. PLOS Genet. 11, e1005711 (2015).

Bycroft, C. et al. The UK Biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature 562, 203–209 (2018).

Hill, W. G., Goddard, M. E. & Visscher, P. M. Data and theory point to mainly additive genetic variance for complex traits. PLoS Genet. 4, e1000008 (2008).

Wilkins, J. F., McHale, P. T., Gervin, J. & Lander, A. D. Survival of the curviest: noise-driven selection for synergistic epistasis. PLoS Genet. 12, e1006003 (2016).

Mackay, T. F. C. & Anholt, R. R. H. Pleiotropy, epistasis and the genetic architecture of quantitative traits. Nat. Rev. Genet. 25, 639–657 (2024).

Yang, J., Wray, N. R. & Visscher, P. M. Comparing apples and oranges: equating the power of case-control and quantitative trait association studies. Genet. Epidemiol. 34, 254–257 (2010).

Yengo, L. et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies for height and body mass index in ∼700000 individuals of European ancestry. Hum. Mol. Genet. 27, 3641–3649 (2018).

Yengo, L. et al. A saturated map of common genetic variants associated with human height. Nature 610, 704–712 (2022).

Bloom, J. S., Ehrenreich, I. M., Loo, W. T., Lite, T.-L. V. & Kruglyak, L. Finding the sources of missing heritability in a yeast cross. Nature 494, 234–237 (2013).

Bloom, J. S. et al. Genetic interactions contribute less than additive effects to quantitative trait variation in yeast. Nat. Commun. 6, 8712 (2015).

Chen, A., Liu, Y., Williams, S. M., Morris, N. & Buchner, D. A. Widespread epistasis regulates glucose homeostasis and gene expression. PLoS Genet. 13, e1007025 (2017).

Matsui, T. et al. The interplay of additivity, dominance, and epistasis on fitness in a diploid yeast cross. Nat. Commun. 13, 1463 (2022).

Hemani, G. et al. Detection and replication of epistasis influencing transcription in humans. Nature 508, 249–253 (2014).

Wood, A. R. et al. Another explanation for apparent epistasis. Nature 514, E3–E5 (2014).

Hemani, G. et al. Phantom epistasis between unlinked loci. Nature 596, E1–E3 (2021).

Petty, L. E. et al. Genome-wide association study identifies novel risk loci for apical periodontitis. Res. Sq. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-2515434/v1. (2023)

Jo, Y. G. et al. Sex-specific analysis in Behçet’s disease reveals higher genetic risk in male patients. J. Autoimmun. 132, 102882 (2022).

Wray, N. R., Wijmenga, C., Sullivan, P. F., Yang, J. & Visscher, P. M. Common disease is more complex than implied by the core gene omnigenic model. Cell 173, 1573–1580 (2018).

Huang, K.-P. et al. Sex differences in response to short-term high fat diet in mice. Physiol. Behav. 221, 112894 (2020).

Martin, A. R. et al. Clinical use of current polygenic risk scores may exacerbate health disparities. Nat. Genet. 51, 584–591 (2019).

Veturi, Y. et al. Modeling heterogeneity in the genetic architecture of ethnically diverse groups using random effect interaction models. Genetics 211, 1395–1407 (2019).

Mathieson, I. The omnigenic model and polygenic prediction of complex traits. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 108, 1558–1563 (2021).

Bogue, M. A. et al. Mouse Phenome Database: a data repository and analysis suite for curated primary mouse phenotype data. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, D716–D723 (2020).

Seecharan, D. J., Kulkarni, A. L., Lu, L., Rosen, G. D. & Williams, R. W. Genetic control of interconnected neuronal populations in the mouse primary visual system. J. Neurosci. 23, 11178–11188 (2003).

Purcell, S. et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 81, 559–575 (2007).

Yang, J. et al. Common SNPs explain a large proportion of the heritability for human height. Nat. Genet. 42, 565–569 (2010).

Yang, J., Lee, S. H., Goddard, M. E. & Visscher, P. M. GCTA: a tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 88, 76–82 (2011).

Willem Kruijer, with a contribution from Ian White (the internal function pin). Contains data collected by Padraic Flood and Rik Kooke. heritability: marker-based estimation of heritability using individual plant or plot data. 1.4 https://doi.org/10.32614/CRAN.package.heritability (2014).

Lippert, C. et al. FaST linear mixed models for genome-wide association studies. Nat. Methods 8, 833–835 (2011).

Peterson, R. A. Finding optimal normalizing transformations via bestNormalize. R. J. 13, 294–313 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work made use of the High-Performance Computing Resource in the Core Facility for Advanced Research Computing at Case Western Reserve University. We acknowledge Dr. Carl Kadie for his assistance with analyses in FaST-LMM. This research was funded by grants DK119305 (D.A.B.), LM010098 (S.M.W), and 5T32HL007567-35 (A.K.M.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.K.M. led the analysis of the HMDP data and the writing of the manuscript. J.B. led the analysis of the UK Biobank data and contributed to the analysis of the HMDP data. C.P. assisted with analyses of the HMDP data. A.J.L. provided guidance with the HMDP data analysis. D.C.C. provided guidance for all analyses and assisted with the analysis of the UK Biobank data. S.M.W. and D.A.B. together developed the concept and oversaw all experimental design and data analysis. All authors edited and provided feedback for the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Dokyoon Kim, Rong Stephanie Huang and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Miller, A.K., Bartlett, J., Pan, C. et al. Concordance between male- and female-specific GWAS results helps define underlying genetic architecture of complex traits. Nat Commun 16, 8695 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63763-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63763-x