Abstract

Electrolyte for high-temperature and high-voltage lithium metal batteries face challenges of thermally decomposition of lithium salt and interfacial corrosiveness with aluminum current collectors/cathode materials. Herein, we report a non-corrosive asymmetric lithium salt, i.e., lithium fluorinated aryl sulfonimide (LiFAS). Due to the fluorinated aryl substituent on the bis-sulfonylimide anion, the LiFAS exhibits several desirable physiochemical properties for high-temperature and high-voltage applications, i.e. high thermal stability (decomposition temperature ~388 °C), high voltage tolerance (anodic decomposition potential ~5.5 V vs. Li/Li+), and a high Li+ transference number of 0.62. Moreover, the LiFAS is able to efficiently inhibit the notorious Al-corrosion issue by forming a dense Al(FAS)3/AlF3 passivation layer on the surface of Al current collector. In addition, LiFAS could also promote the formation of inorganic-rich interphases on the cathode and anode. The unique advantages of LiFAS endow Li||NCM811 full cells great cycling stability and capacity retention at harsh cycling conditions (81% after 230 cycles at 60 °C and 4.5 V, 0.5 C charge/1 C discharge). This work inspires molecular engineering strategy for designing functional lithium salts to enhance the cycle life of LMBs under high-temperatures and high-voltages.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Conventional lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) with graphite negative electrodes are widely used in consumer electronics, electric vehicles, and energy storage systems1,2,3,4. However, their theoretical specific energy poses a significant limitation for further development. Lithium (Li) metal, with its ultra-high theoretical specific capacity (3860 mAh g−1) and the lowest negative electrochemical potential (−3.04 V vs. standard hydrogen electrode), is considered as one of the promising candidate negative electrode materials for the next-generation energy storage devices5,6. For instance, rechargeable lithium metal batteries (LMBs) assembled with high nickel positive electrodes and lithium metal negative electrodes can achieve energy densities exceeding 500 Wh kg−17,8. Nevertheless, traditional lithium salts used in LMBs struggle to deliver satisfactory battery performance at high temperatures (≥60 °C) and high voltages (≥4.5 V) conditions due to issues such as aluminum (Al) collector corrosion, lithium salt decomposition, positive electrode particle breakage, and poor negative electrode stability9,10. These challenges are closely linked to the chemistry of the salt anions.

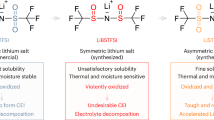

Lithium hexafluorophosphate (LiPF6) is commonly used in commercial battery electrolytes due to its moderate conductivity and low cost11,12. However, LiPF6-based electrolytes become unstable at high temperatures (>55 °C), decomposing into PF5, POF3 and HF, which accelerates the aging process of the battery13,14. These decomposition products further damage the cathode electrolyte interface (CEI)/solid electrolyte interface (SEI), accelerating solvent degradation and ultimately causing rapid performance decay of LMBs. In addition, from the perspective of molecular structure, the instability of LiPF6 at high temperatures is attributed to the high electronegativity of the fluorine atom, which creates a highly polarized P-F bond. This polarization results in an unbalanced electron distribution, making the bond susceptible to breakage and promoting decomposition15. To enhance the thermal stability of lithium salts, replacing P-F bonds with C-F bonds can significantly improve chemical and thermal stability, reduce the generation of corrosive by-products, and further enhance the electrochemical performance of the electrolyte, thereby prolonging battery life16,17. Based on these design principles, researchers have developed lithium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide (LiTFSI) salts with thermal and electrochemical stability. The introduction of C-F bonds with high bond energies provides high thermal stability for LiTFSI at high temperatures18,19. Additionally, the fluorine-containing groups effectively promote salt dissociation, contributing to high ionic conductivity20,21. However, LiTFSI severely corrodes the Al collector, especially at high temperatures and high voltages (potential >3.8 V vs. Li/Li+), leading to quick decay of the battery capacity22,23. The basic properties of different lithium salts are compared as shown in Fig. 1. In this regard, although strategies such as asymmetric lithium salt anions with supramolecular folding structures for realizing a self-cleaning SEI mechanism24, leveraging π-π stacking interactions to enhance the ionic conductivity of polymer electrolytes25, and special oxidizable sulfoximide-based lithium salts for constructing high-performance bilayer CEI on the high-voltage positive electrode surface26, these studies have not investigated the role of asymmetric lithium salts in high-temperature and inhibition of Al collector corrosion. Electrolyte formulations optimization lithium salts design has been explored27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34, well-tailored lithium salt molecules that shows a comprehensive advancement of combining the advantages of high thermal stability, high voltage tolerance, high Li+ transfer efficiency and stable CEI/SEI formation capability is still highly desirable.

Herein, we report an asymmetric lithium salt, i.e., fluorinated aryl sulfonimide (LiFAS), by replacing the trifluoromethyl group of the state-of-the-art TFSI anion with fluorinated aryl groups35. The LiFAS shows several advantages: I) High thermal stability with a decomposition temperature up to 388 °C, high voltage stability with an anodic decomposition potential of 5.5 V (vs. Li/Li+), and a high Li+ transference number of 0.62. The combination of the above physicochemical properties in a single lithium salt is critical for the stable electrochemical performances of LMBs at harsh cycling conditions such as high-voltage and high-temperature. II) The LiFAS could form a dense protective layer, mainly composed of insoluble Al(FAS)3 and AlF3, on the surface of Al current collector. Therefore, electrolyte with LiFAS is able to efficiently inhibit the notorious Al-corrosion issue of the electrolyte, especially at high-voltage and high-temperature conditions. In addition, LiFAS could also promote the formation of a thin and homogeneous interfacial passivation layer, rich in inorganics such as LiF, both on the NCM811 positive electrode and Li metal negative electrode. These combined benefits of LiFAS translated to favorable battery performance at high-temperature (60 °C) and high-voltage (4.5 V) in Li||NCM811 full cells (capacity retention of 81% after 230 cycles). This work highlights the potential of developing lithium salts with functional anions to overcome Al corrosion and improve the cycle life of LMBs under demanding operating conditions.

Results

LiFAS was synthesized via the reaction of fluorinated aryl sulfonyl chloride and trifluoromethanesulfonamide. The detailed synthesis procedures are provided in the supplementary information and methods. 19F and 7Li NMR spectra (Supplementary Fig. S1) and inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) confirmed the successful synthesis of LiFAS (Supplementary Table 1). Initially, we studied the basic physical and electrochemical properties of LiFAS salts and its structural analogue, LiTFSI, was also comparatively studied to better understand its “chemical structure-function” relationship. The thermal stability of both lithium salts was assessed using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), as shown in Fig. 2a. The decomposition temperature (Td, defined as a 5 wt% weight loss) of LiFAS was 388.4°C, higher than that of LiTFSI (378.7 °C), suggesting that the introduction of the fluorinated aryl group enhances its thermal stability. We dissolve the LiFAS salt in the carbonate solvent mixture, i.e. ethylene carbonate (EC)/ethyl methyl carbonate (EMC)/dimethyl carbonate (DMC) (v/v = 1:1:1) to a concentration of 1 M, and the electrolyte was denoted as LiFAS electrolyte. Similarly, the LiTFSI electrolyte (1 M LiTFSI in EC/EMC/DMC) was also prepared and comparatively studied. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) observed no obvious heat absorption peak at 25–85 °C for both electrolytes, indicating that the electrolytes can operate stably at 60 °C (Supplementary Fig. S2). The ionic conductivities of LiFAS electrolyte and LiTFSI electrolyte at room temperature are 8.38 mS cm−2 and 9.35 mS cm−2, respectively. The ionic conductivity of the LiFAS electrolyte was also slightly lower than that of the LiTFSI electrolyte at high temperatures (Fig. 2b), which can be attributed to its larger anionic volume. The electrolyte viscosity shows a similar trend (Fig. 2c, 3.78 mPa s for LiFAS, 2.85 mPa s for LiTFSI, room temperature; 2.43 mPa s for LiFAS, 1.63 mPa s for LiTFSI, 60°C). The contact angles of different electrolytes on the separator (Celegard 2325) were measured to assess their wettability as shown in Supplementary Fig. S3. The contact angles of LiFAS electrolyte and LiTFSI electrolyte were 58.2° and 53.2°, respectively. Good wettability promotes interfacial contact and Li+ transport. As shown in Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. S4, LiFAS electrolyte shows a higher lithium ion transference number (tLi+) at 60 °C compared to LiTFSI electrolyte, i.e., tLi+ = 0.62 for LiFAS vs. tLi+ = 0.53 for LiTFSI. This trend was also observed at room temperature (Supplementary Fig. S5). Temperature-dependent molecular dynamics (MD) simulations (mean square displacement (MSD) of Li+) revealed that LiFAS exhibits higher Li⁺ diffusion coefficients than LiTFSI, favoring improved Li+ transference number (Supplementary Fig. S6 and Supplementary Data 1–6). We further calculated the solvation structure of the electrolyte (Fig. 2e, Supplementary Fig. S7), the increase in aggregates (AGG) at high temperatures is consistent with the elevated Li+ transference number. The radial distribution function (RDF) and coordination number (CN) of the different electrolytes reveal a decrease in the coordination number of Li-solvent and an increase in the coordination number of Li-anion at high temperatures (Supplementary Fig. S8, Supplementary Table 2). The lifetime of Li+ coordination bonds (both with solvent and anions) provides direct evidence for enhanced Li+ transference at high temperature. The coordination bond lifetimes of the Li-solvent and Li-anion are significantly shorter for both LiFAS electrolyte and LiTFSI electrolyte at high temperatures (specific values are shown in Supplementary Table 3). The shorter coordination bond lifetimes indicate rapid dissociation and reformation of coordination bonds, allowing Li⁺ to shuttle more freely between different ion-pair configurations at high temperatures, accelerating the ion transport process and in turn improves the Li+ transference number. As shown by the linear scanning voltammetry (LSV) of Li||Al cell in Fig. 2f, the anodic stability of the LiFAS electrolyte was higher than that of the LiTFSI electrolyte (i.e., 5.5 V for LiFAS and 4.5 V for LiTFSI), which should be attributed to the preferential formation of AlF3-containing passivation layers at the interface by the FAS- anions36,37. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed to evaluate the unoccupied molecular orbitals (LUMO) and highest occupied molecular orbitals (HOMO) of the electrolyte components. As shown in Fig. 2g and Supplementary Table 4, the HOMO energy level of LiFAS (−8.1563 eV) is higher than that of LiTFSI (−8.6415 eV), further supporting LiFAS improved passivation capability and anodic stability. Electrostatic potential (ESP) calculations show that Li+ in LiFAS delocalizes the electron cloud on the F atoms, resulting in more polar C-F bond, which is more likely to break to form a passivation layer of fluorine-rich compounds (Supplementary Fig. S9 and Supplementary Data 7–12). Interestingly, the Mayer bond levels of C-F bonds on different lithium salts also show consistent results (Supplementary Fig. S10). The relevant physicochemical properties of the electrolyte and lithium salt are shown in Supplementary Table 5. In addition, the electrochemical stability of the Al current collector was assessed by measuring the leakage current of the electrode at 4.5 V. The polarized current density of the LiFAS electrolyte decreased sharply in the initial stage and remained at around 1 μA cm−2 throughout the long-term constant voltage polarization after 7200 s. Even at 4.9 V, the Al current collector still shows high stability with a leakage current density lower than 2 μA cm−2 in LiFAS electrolyte (Supplementary Figs. S11, S12). In contrast, the polarized current density of LiTFSI electrolyte initially decreased to 16 μA cm−2, then rapidly increased to 100 μA cm−2, and finally stabilized at 75 μA cm-2 (Fig. 2h) under the same condition, indicating that the Al collector undergoes severe corrosion at 4.5 V. This sharp contrast strongly suggests that LiFAS could effectively inhibits Al current collector corrosion.

a Thermogravimetric analysis profiles. b Ionic conductivity of different electrolytes at 30 °C and 60 °C. c Viscosity of different electrolytes at 30 °C and 60 °C. d Li+ transference number (tLi+) calculated from DC polarization measurements at 10 mV and 60 °C. e Ion-pair percentage changes of LiFAS and LiTFSI at different temperatures. f LSV curves of Li||Al cells with electrolytes containing different lithium salts. g HOMO/LUMO energy levels for each component of the electrolyte. Colors for different elements: Li-violet, H-white, B-brown, C-gray, F-cyan, N-blue, O-red, S-yellow. h Leakage current profiles of Li||Al cells at 4.5 V.

The evolution of the Al surface morphology after leakage current testing (at 4.5 V) was investigated using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). As shown in Fig. 3a, b, the Al shows a smooth and intact morphology after electric polarization in LiFAS electrolyte, while in the LiTFSI electrolyte shows numerous pits and holes. This highlights the crucial role of FAS− anions in preventing Al corrosion. As shown in Fig. 3c, XPS reveals that the LiFAS electrolyte displayed significant peaks of both AlF3 and LiF, which have been well acknowledged to be able to prevent Al corrosion in conventional organic electrolytes38,39. In contrast, no AlF3 peaks were detected in the LiTFSI-based electrolyte, with only trace amounts of LiF detected (Fig. 3d, Al 2p, F 1s). Instead, strong peaks of Al(TFSI)3 (i.e., ca. 74.8 eV in Al 2p spectra; Fig. 3d) and no Al2O3 signal are detected (Fig. 3d, Al 2p and Supplementary Fig. S13, O 1s, suggesting that the surface of the Al electrodes has been severely corroded due to the continuous formation and dissolution of Al(TFSI)3. This observation is further supported by the SEM image in Fig. 3b. Therefore, it is hypothesized that the FAS−, alongside with its anodically decomposition product such as F−, may exhibit strong binding affinity with the Al3+ dissolved into the electrolyte during the anodic polarization. The preferential interaction leads to the formation of insoluble Al(FAS)3 and AlF3, which precipitates on the Al current collector and prevents its further anodic corrosion. However, in case of LiTFSI, the Al(TFSI)3 is soluble in the carbonate electrolyte and fails to passivate the current collector40,41,42

a, b SEM images of Al electrode surface after leakage current test for LiFAS and LiTFSI, respectively. Scale bar is 2 μm. c, d XPS spectra of Al electrode surface after leakage current test for LiFAS and LiTFSI, respectively. e ICP-OES analysis of Li||Al cell cycled in different electrolytes. The electrochemical test conditions for (a–e) are Li||Al cells after leakage current test (4.5 V, 10 h). f 27Al NMR spectra of the Al(TFSI)3 solution with equimolar LiFAS. g Binding energy of Al3+ and different anions. Colors for different elements: Al-pink, C-gray, F-cyan, N-blue, O-red, S-yellow.

To prove the above hypothesis, we carried out the following studies. I) ICP-OES was used to determine the dissolved Al content in Li||Al cell with different electrolytes. Under the 4.5 V leakage current test (10 h), the LiFAS electrolyte exhibited minimal Al dissolution (0.01 ppm), whereas significantly higher Al dissolution (0.39 ppm) was observed in the LiTFSI electrolyte (Fig. 3e). These findings suggest that the LiFAS electrolyte has the ability to suppress Al collector corrosion. II) We synthesized the corresponding aluminum salts, i.e., Al(TFSI)3 (see Supplementary Fig. S14 and Methods) and tested its solubility in carbonate solvents. Al(TFSI)3 was placed in an NMR tube with EC/EMC/DMC (v/v = 1:1:1) and then heated in an oven at 60 °C for 24 h. Al(TFSI)3 was completely soluble in the carbonate solution and a broad peak associated with Al3+ cations were observed (Supplementary Fig. S15). Thus, the high solubility of Al(TFSI)3 in the carbonate solvent is believed to significantly contribute to Al collector corrosion in LiTFSI-based carbonate electrolytes. The continuous dissolution of the Al lead to the gradual loss of electrical connection between the active positive electrode material and the current collector, ultimately causing cell failure. III) Solutions of Al(TFSI)3 in EC/EMC/DMC were prepared and then equimolar amounts of LiFAS were added to the solutions. The 27Al NMR spectral signals were monitored during this process. As shown in Fig. 3f, the addition of LiFAS induced a distinct upfield shift in the 27Al NMR spectral signals, which indicated that FAS- was strongly participated in the solvation structure of Al3+43,44. In addition, we calculated the binding energies of different anions with Al3+ using DFT. As shown in Fig. 3g and Supplementary Data 13–14, the binding energy of FAS- with Al3+ is −6.02 eV, which is significantly higher than that of TFSI- (−4.13 eV). This further suggests that the strong coordination of the FAS- anion with Al3+ is critical for the non-corrosive property of LiFAS salt to Al current collectors.

The non-corrosive property of LiFAS to Al current collectors was further assessed using Li||NCM811 cells under high temperature and high voltage cycling conditions, respectively. In both circumstances, the corrosive Al current collector is one of the main reasons for cell failure. Firstly, at room temperature (RT), with galvanostatic cycled with a voltage window of 3.0–4.3 V at a 1C rate (for half-cell, 1 C = 0.6 mA cm−1), the half-cell in LiFAS (0.8 M LiTFSI + 0.2 M LiFAS + 0.1 M LiBOB in EC/EMC/DMC, v/v = 1:1:1, denoted as E-LiFAS) retained 81.2% of its initial capacity after 700 cycles, while the base electrolyte (1 M LiTFSI + 0.1 M LiBOB in EC/EMC/DMC, v/v = 1:1:1, denoted as E-base) decayed to 80% of its initial capacity after only 280 cycles (Supplementary Fig. S16). Further testing at RT and higher voltage (3.0–4.5 V) showed that the E-LiFAS electrolyte exhibited stable cycling performance, retaining 80% of its initial capacity after 450 cycles (Fig. 4a). In contrast, the E-base electrolyte rapidly failed after 100 cycles due to Al collector corrosion. Secondly, the high-temperature performance of the cells with the two electrolytes differed markedly (Supplementary Fig. S17). The average coulombic efficiency (CE) of E-LiFAS cells is 99.8% from 5th to 350th cycles, with a capacity retention of 78.4% (210 mAh g−1 at 5th cycle to 174 mAh g−1 at 130th cycle). Conversely, high temperature exacerbated Al collector corrosion in the presence of LiTFSI, causing the average CE of E-base cells is 96.7% from 5th to 130th cycles, with a rapid decline in battery capacity (from 212 mAh g−1 at 5th cycle to 174 mAh g−1 at 130th cycle) at 60 °C. It is worth noting that without LiBOB, the base electrolyte cannot operate for two formation cycles (Supplementary Fig. S18). Therefore, LiFAS plays a leading role in enhancing battery performance (Supplementary Fig. S19). Thirdly, the galvanostatic cycling performance of the cells under more extreme conditions, i.e. high voltage plus high temperature (4.5 V and 60 °C) further highlighted the advantages of LiFAS. The E-LiFAS cell retaining 82% of its initial capacity at 250th cycles and maintaining an average CE of 99.5% (Fig. 4b, c). In contrast, the cell with the E-base electrolyte experienced overcharging phenomenon just at the second cycle (Fig. 4d). This overcharging phenomenon is attributed to Al collector corrosion, which disrupts the electrical connection between the positive electrode material and the current collector, ultimately leading to cell failure. Moreover, the Li||NCM811 cell at 4.7 V was able to cycle stably for 150 cycles (78.8% retention) (Supplementary Fig. S20). Fourthly, the E-LiFAS battery shown a higher voltage stability compared to the E-based battery during a 30-h high temperature and high voltage self-discharge measurements (Fig. 4e, Supplementary Fig. S21). The Li||NCM811 cell with E-LiFAS electrolyte has a slow voltage decay and shows a high stable value of 4.25 V after 30 h at 60 °C. In contrast, the voltage of the E-base cell drops rapidly to 4.19 V after 30 h. Overall, the above tests indicate that LiFAS can significantly enhance the electrochemical performances of the high energy Li||NCM811 LMBs at high temperatures and high voltages.

a Cycling performance of Li(300 μm)||NCM811(3 mg cm−2) cells between 3.0 and 4.5 V in E-LiFAS and E-base at RT. b Cycling performance of Li (300 μm)||NCM811(3 mg cm−2) cells between 3.0 and 4.5 V in different electrolytes at 60 °C. c, d Corresponding voltage-capacity curves for Li||NCM811 cells in c E-LiFAS and d E-base. e Self-discharge curves of Li||NCM811 cells stored at 60 °C. Each half-cell electrolyte volume: 70 μL.

To find out the origin of the enhanced electrochemical performance with LiFAS, a comprehensive characterization of Li||NCM811 cells cycled (3.0–4.3 V) after 50 cycles at 60 °C was performed. The SEM images revealed that NCM811 particles cycled in the E-LiFAS electrolyte maintained an intact structure and smooth surface (Fig. 5a). In contrast, NCM811 particles cycled in the E-base electrolyte exhibited severe cracks and surface roughness (Fig. 5b). A similar difference was also shown at RT (Supplementary Fig. S22). In transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images, it is observed that a thin and uniform CEI layer with a thickness of about 8.5 nm on the NCM811 surface cycled in the E-LiFAS electrolyte (Fig. 5c). However, a non-uniform CEI layer with the thickest region reaching 104 nm (Fig. 5d) was formed in the E-base electrolyte. A thicker CEI layer was also present at RT with the E-base electrolyte (Supplementary Fig. S23). The CEI composition of the cycled NCM811 positive electrode was characterized by XPS. As shown in Fig. 5e, f, the Al 2p spectra revealed a clear difference between the two electrolytes. No Al-containing signals were detected on the NCM811 positive electrode surface in the E-LiFAS electrolyte, demonstrating that LiFAS is compatible with Al current collectors (Supplementary Fig. S24). In contrast, the E-base electrolyte showed a large amount of Al(TFSI)3 (74.8 eV) on the NCM811 positive electrode surface which should be attributed to Al collector corrosion. Additionally, time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (TOF-SIMS) analysis revealed a substantial presence of AlF4- fragments on the positive electrode surface in the E-base electrolyte, whereas no AlF4- fragments were detected in the E-LiFAS electrolyte (Fig. 5g, h and Supplementary Fig. S25). Electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS) spectra provide important information about the composition and structure of CEI. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S22, the EELS spectra showed no Al K-edge signal in the CEI formed by E-LiFAS, whereas E-base shows a prominent Al K-edge at ~1560 eV. In addition, the EELS elemental mapping of CEI (Supplementary Fig. S26) also shows that E-base exhibits more pronounced Al elements and less F elements compared to E-LiFAS. And the organic component (C and O elements) shows a similar trend (i.e., less E-LiFAS than E-base). This further validates the Al corrosion inhibition property of LiFAS. The F 1s spectra revealed a higher LiF (684.5 eV) content on the positive electrode surface in the E-LiFAS cell compared to that in the E-base cell. This suggests that the presence of fluorinated aryl groups in LiFAS promotes the formation of an inorganic-rich CEI layer. Consistently, TOF-SIMS 2D and 3D reconstruction maps further confirm a greater abundance of LiF2- fragments on the positive electrode surface of E-LiFAS cells (Fig. 5g, h and Supplementary Fig. S27). Both the C 1s and O 1s spectra showed insignificant signals of C-O (C 1s 285.9 eV, O 1s 534.3 eV) and C=O (C 1s 290.6 eV, O 1s 532.9 eV) species (Fig. 5e) in the E-LiFAS electrolyte, which suggests the effectively suppressed solvent decomposition of E-LiFAS45. However, the CEI formed in the E-base electrolyte exhibited significantly higher C-O and C=O peaks, suggesting a significant solvent decomposition of the E-base electrolyte. The TOF-SIMS 3D reconstruction map also demonstrates fewer organic fragments (C2HO-, C2H3O-) in E-LiFAS compared to E-base (Fig. 5g, h and Supplementary Figs. S28, S29). Therefore, the decomposition of solvents in the E-LiFAS electrolyte is reduced, resulting in the formation of a thin and uniform inorganic-rich CEI layer. Combined with the Al protection of LiFAS, the electrochemical performance of the battery is significantly enhanced.

SEM images of the NCM811 positive electrode side in a E-LiFAS and b E-base, scale bar is 2 μm. TEM images of the NCM811 positive electrode in c E-LiFAS (scale bar is 10 nm) and d E-base (scale bar is 20 nm). e, f XPS analysis of the cycled NCM811 positive electrode in different electrolytes. TOF-SIMS 3D reconstruction maps of C2HO-, C2H3O-, LiF2- and AlF4- in the different electrolytes: g E-base and h E-LiFAS.

The morphology of the Li metal negative electrode and the SEI layer are crucial factors in the performance of LMBs. SEM images revealed that the Li metal negative electrode in the LiFAS electrolyte (E-LiFAS) has a dense and uniform structure (Fig. 6a), whereas that in the E-base electrolyte displays numerous cracks (Fig. 6b). The Li deposition in the E-LiFAS electrolyte showed dense and large lithium particles (Fig. 6c), ensuring stable Li plating/stripping during the cycling process. In contrast, numerous inhomogeneous Li dendrites were formed in the E-base electrolyte (Fig. 6d). These dendrites can evolve into “dead Li” – Li metal deposits that lose electrical connection over cycling, ultimately contributing to rapid capacity degradation in the battery46,47. XPS analysis of the SEI components on the Li metal negative electrode surface cycled in different electrolytes showed distinct differences (Fig. 6e, f). The C 1s spectra in the E-LiFAS electrolyte showed a few of C-C/C-H (284.8 eV) and C-O (285.8 eV) species (Supplementary Fig. S30). However, the E-base electrolyte showed a remarkable increase in organic moieties, suggesting more organic solvent reduction at the negative electrode surface. Additionally, the SEI formed in E-LiFAS showed fewer C=O (531.3 eV) products in the O 1s spectra and more LiF (684.8 eV) in the F 1s spectra compared to E-base electrolyte, indicating that the introduction of fluorinated aryl groups in LiFAS promotes the formation of an inorganic-rich SEIs on the Li metal negative electrode surface. TOF-SIMS depth profiles, 2D recombination maps, and 3D recombination maps also demonstrate stronger inorganic species (LiF2-) signals and weaker organic species (C2HO-, C2H3O-) signals in E-LiFAS electrolyte (Fig. 6g and Supplementary Figs. S31–S33). A pronounced difference was also observed in the Al 2p spectra. No Al-containing species were detected on the Li metal negative electrode cycled in E-LiFAS electrolyte (Fig. 6e), while that in the E-base electrolyte exhibited a strong peak at 74.8 eV, which should be attributed to the Al(TFSI)3 diffused from the positive electrode to the negative electrode side (Fig. 6f). This observation is further supported by the AlF4- fragments (Fig. 6h and Supplementary Fig. S34). These findings emphasize the crucial role of salt anion chemistry in inhibiting Al collector corrosion especially at high temperature and high voltage. Schematics 6i and 6j depict the proposed working mechanism for LiTFSI and LiFAS electrolytes, respectively. In the LiTFSI electrolyte, the reaction between LiTFSI and the Al current collector generates soluble Al(TFSI)3, leading to Al corrosion and the formation of a thick, non-uniform CEI on the positive electrode surface. The Al(TFSI)3 then diffuses to the electrolyte and deposited on the Li metal negative electrode surface. The cross-talk between positive electrode and negative electrode severely deteriorates the SEI and promotes lithium dendrite growth33. Conversely, LiFAS could efficiently passivate the Al current collector by forming a dense and stable interfacial layer composed of Al(FAS)3 and AlF3, effectively preventing further Al corrosion and mitigating the followed-up, undesirable cross-talk between positive electrode/negative electrode.

SEM images of Li metal negative electrode surface after cycling. a E-LiFAS and b E-base, scale bar is 10 μm; c E-LiFAS and d E-base, scale bar is 1 μm. e, f XPS analysis of the cycled Li metal negative electrode in different electrolytes. TOF-SIMS 3D reconstruction maps of AlF4- and LiF2- in the different electrolytes: E-LiFAS (g) and E-base (h). Schematic diagram of Al corrosion mechanism of LiTFSI (i) and Al protection mechanism of LiFAS (j).

To further assess the performance of LiFAS in LMBs, the cycling performance of Li||NCM811 full batteries with different positive electrode mass loadings was systematically investigated using a formulated advanced LiFAS electrolyte (E-LiFAS electrolyte with 0.05 M LiNO3) and a baseline electrolyte (E-base electrolyte with 0.05 M LiNO3) at various temperatures and voltages. The trace amount of LiNO3 was added to further improve the Li plating/stripping stability of the Li metal negative electrode (Supplementary Figs. S35, S36)48. When pairing a NCM811 positive electrode (mass-loading, 11 mg cm⁻2) with a thin Li metal foil (40-μm thick), the full cell (N/P ≈ 3.6) galvanostatic cycled (3.0–4.3 V, RT) in the advanced LiFAS electrolyte exhibited high capacity retention (up to 82%) and a high average CE of 99.8% after 400 cycles at a charging/ discharging rate of 0.5 C/1 C (for full cell, 1 C = 2.2 mA cm-2) (Supplementary Fig. S37). In contrast, the cell with the baseline electrolyte showed rapid capacity decay after 160 cycles. The performance of the advanced LiFAS electrolyte was further validated for the full cell at high temperature performance (60 °C). The Li||NCM811 full cell with the advanced LiFAS electrolyte maintained a higher capacity retention of 82.4% after 280 cycles, while that the baseline electrolyte decayed to 50% of the initial capacity after ~100 cycles (Supplementary Fig. S38). While increasing cell voltage elevates specific energy49,50, it also exacerbates the corrosion of the Al current collector by LiTFSI. As shown in Fig. 7a, the full cell with the advanced LiFAS electrolyte stably cycled for 300 cycles with 75% capacity retention (at RT, 3.0–4.5 V), while the baseline electrolyte rapidly failed after 130 cycles (Supplementary Fig. S39). To assess cell performance under harsher conditions, the cycling stability of the Li||NCM811 full cell was further tested at 60 °C with the voltage between 3.0 and 4.5 V. The cell with the advanced LiFAS electrolyte retained 81% capacity after 230 cycles (Fig. 7b), with the stable voltage profiles shown in Fig. 7c. In addition, the Li||NCM811 full cell with LiNO3-free electrolyte shows comparable performance (Supplementary Fig. S40). Conversely, the full cell with the baseline electrolyte was overcharged during the second formation (voltage profile shown in Supplementary Fig. S41) due to severe Al collector corrosion. A 350 mAh Li (50 μm)||NCM811 (17.5 mg cm−2) pouch cell was prepared to fulfill the practical parameter requirements. The pouch cell with advanced LiFAS electrolyte (3.0–4.3 V) achieved 82% capacity retention (70 mA charge/105 mA discharge, RT) after 100 cycles under lean electrolyte conditions (3.0 g Ah−1), while the baseline electrolyte cell failed after 20 cycles due to severe Al corrosion (Fig. 7d). These results clearly demonstrate that LiFAS effectively is a promising lithium salt for LMBs operating at elevated temperatures and high-voltages (Supplementary Table 6).

a Cycling performance of the Li(40 μm)||NCM811(11 mg cm-2) full cell (N/P ≈ 3.6) at RT between 3.0 and 4.5 V in different electrolytes. b Cycling performance of the Li(40 μm)||NCM811(11 mg cm-2) full cell in advanced LiFAS electrolyte. c Corresponding voltage-capacity curves for Li||NCM811 full cell in advanced LiFAS electrolyte. Each full-cell electrolyte volume: 50 μL. d Cycling performance of Li||NCM811 pouch cell (E/C = 3 g Ah-1). E/C electrolyte mass/cell capacity.

Discussion

In conclusion, we report an asymmetric LiFAS salt which is highly suitable for stable cycling of high energy LMBs at harsh conditions, such as high temperature and high voltage. Due to the fluorinated aryl substituent on the bis-sulfonylimide anion, the LiFAS exhibits a combination of high thermal stability, high voltage stability and a high Li+ transference number. Moreover, the LiFAS could form a dense protective layer composed of insoluble Al(FAS)3 and AlF3 on the surface of Al current collector, therefore efficiently mitigate the notorious Al-corrosion issue. In addition, LiFAS could also promote the formation of a thin, homogeneous and inorganic-rich CEI and SEI respectively on the cathode and anode. Notably, the Li||NCM811 full cell using the LiFAS based electrolyte retains 81% of its capacity after 230 cycles even cycling at elevated temperatures (60 °C) and high voltages (4.5 V). These results highlight the critical role of tailored salt anion design in promoting the practical application of high specific energy lithium metal batteries for high-voltage and high-temperature operations.

Methods

Materials

Anhydrous acetonitrile (99.8%), dichloromethane (99.9%), and N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP, 99.5%) were purchased from Aladdin. Anhydrous ether (AR) and acetone (AR) were obtained from Beijing Tongguang Co. Trifluoromethanesulfonamide (CF3SO2NH2, 98%) and potassium carbonate (K2CO3, 99%) were provided by Meryer. Bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide acid (HTFSI, 99%) was purchased by TCI. Battery-grade lithium bis(trifluoromethane sulfonimide) (LiTFSI, 99%) and lithium bis(oxalate)borate (LiBOB, 99%) were provided by Suzhou DoDoChem Co. Pentafluorobenzenesulfonyl chloride (98%) was obtained from Shanghai Bide Co. Lithium perchlorate (LiClO4, 99.9%) and aluminum perchlorate 9-hydrate (reagent-grade, 99%) were obtained from Adamas and Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd, respectively. Ethylene carbonate (EC): ethyl methyl carbonate (EMC): dimethyl carbonate (DMC) (1:1:1, v/v, 99.9%) was purchased by Suzhou DoDoChem Co. All chemicals were used as received without further purification. Metallic Li foil (40 μm) was purchased by China Energy Lithium Co., Ltd. The NMC811 positive electrode sheets were prepared by laying a mixture of 90 wt% NMC811 material, 5 wt% super P and 5 wt% PVDF900 (8 wt% NMP) on an aluminum foil current collector (12 μm) using an automatic coating machine (Shenzhen Kejing MSK-AFA-HC100), and then vacuum dried at 100 °C overnight. Cut NCM811 positive electrodes (loading: 11 mg cm-2) into 12 mm diameter discs (MSK-T10 Manual Slicer). Cut 40-μm thick Li foil into 14 mm diameter discs as negative electrodes. Celegard 2325 separator diameter: 19 mm, thickness: 25 μm, N/P ratio: 3.6. Industrial-grade 350 mAh Li||NCM811 pouch cell configuration (NCM811 loading: 17.5 mg cm-2, Li metal foil thickness: 50 μm, Celegard 2325 separator: 25 μm, E/C = 3 g Ah-1. E/C, electrolyte mass/cell capacity)

Synthesis of LiFAS

Under the catalysis of K2CO3, CF3SO2NH2 and pentafluorobenzenesulfonyl chloride reacted at room temperature (25 ± 5 °C) for 36 h. The supernatant was rotary evaporated to obtain a white solid powder (KFAS). Subsequently, KFAS underwent a cation exchange reaction with LiClO₄ in acetonitrile to synthesize the crude product LiFAS. The pure LiFAS salt was obtained through sequential washing, followed by vacuum drying at 80 °C and transfer into an argon-filled glove box32.

Synthesis of Al(TFSI)3

3 g of HTFSI were dissolved in 50 ml of purified water, and an excess of Al foil was added and then reacted at 100 °C for 48 h. The unreacted Al was then filtered, and the remaining solution was concentrated using a rotary evaporator to obtain a viscous liquid. A white powder was obtained by drying in a vacuum oven at 120 °C and about 0.01 mbar. The composition was verified by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR).

Electrolyte preparation

1 M LiTFSI and 0.1 M LiBOB were dissolved in EC:EMC:DMC (v/v = 1:1:1) to obtain the E-base electrolyte. 0.8 M LiTFSI, 0.2 M LiFAS and 0.1 M LiBOB were dissolved in EC:EMC:DMC (v/v = 1:1:1) to obtain the E-LiFAS electrolyte. The advanced LiFAS electrolyte was prepared by dissolving 0.05 M LiNO3 additive into E-LiFAS electrolyte. The baseline electrolyte was prepared by dissolving 0.05 M LiNO3 additive into E-base electrolyte. All the electrolytes were prepared inside an Ar-filled glovebox (O2 < 0.01 ppm, H2O < 0.01 ppm) at room temperature (25 ± 5°C).

Characterizations

Thermal properties of pure lithium salts were recorded by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA, TA Q5000IR) under a N2 atmosphere at a heating rate of 10 °C min-1. 27Al, 7Li and 19F nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were recorded on a Bruker AVANCEIII-400M NMR spectrometer at room temperature (25 ± 5 °C). All cells used for characterization were disassembled in an argon filled glove box at room temperature and then cleaned using DEC. The cleaned material was cut to the appropriate size and transferred into the characterization instrument chamber through an argon-filled sealed plastic box for vacuum characterization testing. All characterization tests were performed at room temperature (25 ± 5 °C) unless otherwise noted. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM, JEOL, JSM-7401F, Japan, accelerating voltage of 3 kV) was used to characterize the lithium deposition morphology, positive electrode NMC811 particles, and Al current collectors. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM, JEOL, JEM-2100Plus, Japan) were used to characterize the CEI layers coating on positive electrode NMC811 particles. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Thermo Fisher Scientific Ltd., U.S.A) was applied to analyze the chemical composition of Al current collectors, SEI, and CEI layers. The XPS test conditions: The analysis chamber had a vacuum of ~2 ×10-7 mbar, with an Al Kα X-ray source (1486.6 eV) operating at 200 W for survey scans and 300 W for core level spectra. The binding energy was calibrated by the C 1s line at 284.8 eV. Time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (TOF-SIMS) was performed to characterize the components of CEI/SEI. TOF-SIMS (IONTOF GmbH, Germany) used Cs+ as the sputtering ion beam with a sputtering rate of 0.22 nm s-1 and a swept area of 100 × 100 μm. Electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS) characterization of the composition and elemental mapping of CEI. The EELS (Titan Cubed Themis G2 300) test has a 25 mrad convergence angle, 56.5 mrad collection angle, and 2 ms exposure time. Inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) was conducted on an Agilent 5800 to detect the concentration of Al3+ in the electrolyte and the purity of the LiFAS salt. For the Al3+ concentration measurement, we disassembled the cycled Li||Al cells (4.5 V leakage current test, 10 h) and soaked the cycled separators in 2 mL EC/EMC/DMC for 2 h in the Ar-filled glove box. All the liquid organic solution was collected for further tested by ICP-OES. For LiFAS salt purity testing, 10 mg of LiFAS was dissolved in 2 mL of EC/EMC/DMC solution within an argon-filled glove box, followed by further analysis via ICP-OES. The viscosity values of the different electrolytes were measured at room temperature and 60 °C using a viscosity tester (Anton Paar-MCR 102e). The contact angles of the different electrolytes on the separator (Celegard 2325) were measured using Dataphysics-OCA 20 to assess their wettability. The thermal stability of the two electrolytes were measured on DSC analyzer (DSC Q2000 V24.11 Build 124) at a heating rate of 5 °C min-1 with nitrogen as carrier gas from 30 °C to −85 °C and then to 85 °C.

Electrochemical measurement

The lithium transfer number (\({t}_{{Li}+}\)) was determined using the Bruce-Vincent method. A Li||Li symmetric cell was assembled and applied to a constant DC polarization voltage of 10 mV. The \({t}_{{Li}+}\) was calculated using the equation32:

where \({I}_{s}\) and \({I}_{0}\) are the steady-state and initial currents, respectively, and \({R}_{s}\) and \({R}_{0}\) are the steady-state and initial interfacial resistances, respectively.

The Li+ conductivity (\(\sigma\)) of the electrolyte was measured by assembling a stainless steel (SS) symmetric cell calculated as:

where L is the separator thickness (25 μm), S is the contact area between the two stainless steel electrodes (diameter 15.8 mm), R is the bulk resistance.

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements were performed applying a potentiostatic of 10 mV (peak-to-peak), with a frequency range of 0.1 Hz–100 kHz, and a resolution of 12 data points per decade. Prior to ElS measurements, the cell was left at open circuit voltage for 10 s to ensure stable electrochemical conditions.

Linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) tests (scan rate 5 mV s-1, voltage range: 3.0–6.5 V) were performed using a CHI760E electrochemical workstation with a 12 mm diameter Li-metal as the counter electrode and a 16 mm diameter Al foil as the working electrode. The charge−discharge performances of the Li||NCM811 batteries were conducted on a battery test system (LANHE CT3001A or NEWARE CT-4008Tn-5V10mA-164). Chronoamperometry (CA) and leakage current tests were performed using a Princeton electrochemical workstation under the following conditions: 4.5 V held at a constant voltage for 7200 s, and 0.2 V intervals from 4.3 V to 4.9 V held at constant voltage for 7200 s.

Cell assembly and testing

All cells for electrochemical testing were assembled in a glovebox using a Celegard 2325 separator (thickness, 25 μm) and a CR2032 case (case and spring materials: stainless steel). For the Li||NCM811 half-cells, 3 mg cm-2 NCM811 was assembled as the positive electrode (single-coating, 12 mm diameter) and 300 μm thickness Li metal as the negative electrode. Before the cycling tests (1 C charge/1 C discharge), all half-cells proceeded with a two formation at 0.2 C (voltage range: 3.0–4.3 V, current density: 0.2 C = 0.12 mA cm-2). The amount of electrolyte for all half-cells was 70 μL. For Li||NCM811 full-cells (N/P ≈ 3.6), a 40 μm-thickness Li foil paired with a high active material mass loading positive electrode of 11 mg cm-2 (single-coating, 12 mm diameter). Before the cycling tests (0.5 C charge/1 C discharge), all full-cells proceeded with a two formation at 0.1 C (voltage range: 3.0–4.3 V, current density: 0.1 C = 0.22 mA cm-2). To emphasize the reproducibility of results, three parallel samples were tested for each battery group (Supplementary Fig. S42). Select one set from the parallel samples as the battery data presented in the manuscript. For the pouch cell tests, all pouch cells were two-cycle formation at 0.1 C and degassed prior to normal cycling tests. The stack pressure of the pouch cells was ~350 kPa. The amount of electrolyte for all full cells was 50 μL (E/C ≈ 22.7 mL Ah-1). The Coulombic efficiency (CE) is calculated as the ratio of discharge capacity divided by the charge capacity in the preceding charge cycle, independently of whether a cell is assembled in a charged or discharged state. For Li||Li symmetric cell experiments (current density: 1 mA cm-2, areal capacity: 1 mAh cm-2), the diameter of the Li disc is 12 mm and the thickness is 300 μm.

Quantum chemical calculations

All quantum chemical calculations were performed by the density functional theory (DFT) with the Gaussian 16 program. All DFT calculations were carried out at the B3LYP/6-311 G(d,p) level. Multiwfn and VMD package were utilized to analysis electrostatic potentials (ESPs), Mayer bond level, and the HOMO and LUMO energies. The binding energies (\(\Delta {E}_{b}\)) between Al3+ and two anions were obtained according to the equation:

where \({E}_{{tot}}\) is the total energy, \(E\left({{Al}}^{3+}\right)\) is the energy of Al3+, and \(E(X)\) is the energy of TFSI- or FAS-.

MD simulations

Classical molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were conducted using the GROMACS package, where periodic boundary conditions were utilized. The force field was the General Amber Force Field (GAFF). Two non-aqueous electrolytes were obtained by Packmol software, where compounds were randomly arranged in a cubic box. Topology files for organic molecules and anions were generated using the Sobtop software. Multiwfn program were performed to gain the restrained electrostatic potential charge. Equilibrated by the steepest descent method, two electrolyte systems were simulated with a time step of 1 fs. During simulations, a cutoff of 1.2 nm was chosen for L-J interactions, and the particle mesh Ewald summation method was used to calculate the long-range electrostatic interactions. To obtain the mean squared displacement (MSD) for Li ions in the two systems, we performed the MD simulations at 300 and 335 K. For each target temperature, after equilibrated by V-rescale thermostat and C-rescale barostat for 20 ns, NPT simulations for 30 ns were utilized to calculate MSD. The coordination bond lifetimes of lithium ions and O in different solvents or anions were calculated from the average over all autocorrelation function of existence functions (either 0 or 1) of all coordination bonds:

While \({s}_{i}\left(t\right)=\{{\mathrm{0,1}}\}\) for coordination bond \(i\) at time \(t\). The integral of \(C\left(\tau \right)\) gives a rough estimate of the average coordination bond lifetime \(\tau\):

Data availability

The datasets analyzed and generated during the current study are included in the main text and its Supplementary Information. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Manthiram, A. A reflection on lithium-ion battery cathode chemistry. Nat. Commun. 11, 1550 (2020).

Tarascon, J. M. & Armand, M. Issues and challenges facing rechargeable lithium batteries. Nature 414, 359–367 (2001).

An, J., Wang, F., Yang, J.-Y., Li, G. & Li, Y. An Ion-Pumping Interphase on Graphdiyne/Graphite Heterojunction for Fast-Charging Lithium-Ion Batteries. CCS Chem. 6, 110–124 (2024).

Choi, J. W. & Aurbach, D. Promise and reality of post-lithium-ion batteries with high energy densities. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 16013 (2016).

Zhang, S. et al. Tackling realistic Li+ flux for high-energy lithium metal batteries. Nat. Commun. 13, 5431 (2022).

Liu, Y., Zhou, G., Liu, K. & Cui, Y. Design of Complex Nanomaterials for Energy Storage: Past Success and Future Opportunity. Acc. Chem. Res. 50, 2895–2905 (2017).

Zhang, S. et al. Oscillatory solvation chemistry for a 500 Wh kg−1 Li-metal pouch cell. Nat. Energy 9, 1285–1296 (2024).

Jie, Y. et al. Towards long-life 500 Wh kg−1 lithium metal pouch cells via compact ion-pair aggregate electrolytes. Nat. Energy 9, 987–998 (2024).

Xu, K. Electrolytes and interphases in li-ion batteries and beyond. Chem. Rev. 114, 11503–11618 (2014).

Liu, M. et al. Hydrolysis of LiPF6-containing electrolyte at high voltage. ACS Energy Lett. 6, 2096–2102 (2021).

Yuan, S. et al. Deshielding anions enable solvation chemistry control of LiPF6-based electrolyte toward low-temperature lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 36, 2311327 (2024).

Qin, M. et al. Doping in solvation structure: enabling fluorinated carbonate electrolyte for high-voltage and high-safety lithium-ion batteries. ACS Energy Lett. 9, 2536–2544 (2024).

Guéguen, A. et al. Decomposition of LiPF6 in high energy lithium-ion batteries studied with online electrochemical mass spectrometry. J. Electrochem. Soc. 163, A1095 (2016).

Spotte-Smith, E. W. C., Petrocelli, T. B., Patel, H. D., Blau, S. M. & Persson, K. A. Elementary decomposition mechanisms of lithium hexafluorophosphate in battery electrolytes and interphases. ACS Energy Lett. 8, 347–355 (2023).

Niedzicki, L. et al. New covalent salts of the 4+V class for Li batteries. J. Power Sources 196, 8696–8700 (2011).

Kim, Y.-S., Kim, T.-H., Lee, H. & Song, H.-K. Electronegativity-induced enhancement of thermal stability by succinonitrile as an additive for Li ion batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 4, 4038–4045 (2011).

Fu, A. et al. Highly stable operation of LiCoO2 at cut-off ≥4.6 V enabled by synergistic structural and interfacial manipulation. Energy Storage Mater. 46, 406–416 (2022).

Li, X.-Y. et al. Regulating lithium salt to inhibit surface gelation on an electrocatalyst for high-energy-density lithium–sulfur batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 14638–14646 (2022).

Phan, A. L. et al. Solvent-free electrolyte for high-temperature rechargeable lithium metal batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2301177 (2023).

Yan, S. et al. Zwitterionic matrix with highly delocalized anionic structure as an efficient lithium ion conductor. CCS Chem. 5, 1612–1622 (2023).

Xu, G., Shangguan, X., Dong, S., Zhou, X. & Cui, G. Formulation of blended-lithium-salt electrolytes for lithium batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 3400–3415 (2020).

Dahbi, M., Ghamouss, F., Tran-Van, F., Lemordant, D. & Anouti, M. Comparative study of EC/DMC LiTFSI and LiPF6 electrolytes for electrochemical storage. J. Power Sources 196, 9743–9750 (2011).

Morita, M., Shibata, T., Yoshimoto, N. & Ishikawa, M. Anodic behavior of aluminum current collector in LiTFSI solutions with different solvent compositions. J. Power Sources 119-121, 784–788 (2003).

Xia, Y. et al. Designing an asymmetric ether-like lithium salt to enable fast-cycling high-energy lithium metal batteries. Nat. Energy 8, 934–945 (2023).

Qiao, L. et al. Anion π–π stacking for improved lithium transport in polymer electrolytes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 9806–9816 (2022).

Lu, Y. et al. Breaking the molecular symmetricity of sulfonimide anions for high-performance lithium metal batteries under extreme cycling conditions. Nat. Energy 10, 191–204 (2024).

Jiao, S. et al. Behavior of lithium metal anodes under various capacity utilization and high current density in lithium metal batteries. Joule 2, 110–124 (2018).

Zheng, J. et al. Electrolyte additive enabled fast charging and stable cycling lithium metal batteries. Nat. Energy 2, 17012 (2017).

Zhang, Q.-K. et al. Homogeneous and mechanically stable solid–electrolyte interphase enabled by trioxane-modulated electrolytes for lithium metal batteries. Nat. Energy 8, 725–735 (2023).

Geng, Z. et al. Lithium metal batteries capable of stable operation at elevated temperature. Energy Storage Mater. 23, 646–652 (2019).

Han, H. et al. Lithium (fluorosulfonyl)(nonafluorobutanesulfonyl)imide (LiFNFSI) as conducting salt to improve the high-temperature resilience of lithium-ion cells. Electrochem. Commun. 13, 265–268 (2011).

Yan, S. et al. Asymmetric trihalogenated aromatic lithium salt induced lithium halide rich interface for stable cycling of all-solid-state lithium batteries. ACS Nano 17, 19398–19409 (2023).

Qiao, L. et al. Stable non-corrosive sulfonimide salt for 4-V-class lithium metal batteries. Nat. Mater. 21, 455–462 (2022).

Holoubek, J. et al. Tailoring electrolyte solvation for Li metal batteries cycled at ultra-low temperature. Nat. Energy 6, 303–313 (2021).

Yan, S. et al. Selectively fluorinated aromatic lithium salts regulate the solvation structure and interfacial chemistry for all-solid-state batteries. Sci. Adv. 11, eads4014 (2025).

Krause, L. J. et al. Corrosion of aluminum at high voltages in non-aqueous electrolytes containing perfluoroalkylsulfonyl imides; new lithium salts for lithium-ion cells. J. Power Sources 68, 320–325 (1997).

Qiao, L. et al. A promising bulky anion based lithium borate salt for lithium metal batteries. Chem. Sci. 9, 3451–3458 (2018).

Kühnel, R.-S., Lübke, M., Winter, M., Passerini, S. & Balducci, A. Suppression of aluminum current collector corrosion in ionic liquid containing electrolytes. J. Power Sources 214, 178–184 (2012).

McOwen, D. W. et al. Concentrated electrolytes: decrypting electrolyte properties and reassessing Al corrosion mechanisms. Energy Environ. Sci. 7, 416–426 (2014).

Yang, H., Kwon, K., Devine, T. M. & Evans, J. W. Aluminum corrosion in lithium batteries an investigation using the electrochemical quartz crystal microbalance. J. Electrochem. Soc. 147, 4399 (2000).

Brox, S. et al. Innovative, non-corrosive LiTFSI cyanoester-based electrolyte for safer 4 V lithium-ion batteries. ChemElectroChem 4, 304–309 (2017).

Meister, P. et al. Anodic behavior of the aluminum current collector in imide-based electrolytes: influence of solvent, operating temperature, and native oxide-layer thickness. ChemSusChem 10, 804–814 (2017).

Chen, J.-X. et al. Solvating lithium and tethering aluminium using di-coordination-strength anions for low-temperature lithium metal batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 17, 4036–4043 (2024).

Kim, D. Y., Singh, N. J. & Kim, K. S. Cyameluric acid as anion-π type receptor for ClO4− and NO3−: π-stacked and edge-to-face structures. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 4, 1401–1407 (2008).

Ren, X. et al. Enabling high-voltage lithium-metal batteries under practical conditions. Joule 3, 1662–1676 (2019).

Xiang, Y. et al. Gas induced formation of inactive Li in rechargeable lithium metal batteries. Nat. Commun. 14, 177 (2023).

Zhang, W. et al. Recovery of isolated lithium through discharged state calendar ageing. Nature 626, 306–312 (2024).

Zhang, W. et al. Engineering a passivating electric double layer for high performance lithium metal batteries. Nat. Commun. 13, 2029 (2022).

Chen, L. et al. Achieving high energy density through increasing the output voltage: a highly reversible 5.3 V battery. Chem 5, 896–912 (2019).

Li, Z. et al. Non-polar ether-based electrolyte solutions for stable high-voltage non-aqueous lithium metal batteries. Nat. Commun. 14, 868 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program (grant number 2023YFB2503700, K.L.), the National Key Research and Development Program (grant number 2023YFC3008804, K.L.), the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (grant number Z220020, K.L.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.L. and K.L. conceived the idea and designed the experiments. Z.L performed the material characterizations and electrochemical measurements with assistance from S.Y. and Y.L. X.M., P.Z., W.H., Y.O., Y.W., C.L., J.F., Q.C., X.P., Y.X., X.S., H.Z. and H.L. helped with discussion. Q.F provided theoretical calculations. S.Y provided the Li salt design. Z.L and K.L. analyzed the data and prepared the paper with contributions from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Haiming Xie, Yuki Yamada and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Z., Yan, S., Lu, Y. et al. Non-corrosive asymmetric fluorinated aryl sulfonimide lithium salt for high-temperature and high-voltage lithium metal batteries. Nat Commun 16, 9721 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64737-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64737-9