Abstract

Current methods for detecting Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M.tb) in centralized medical facilities are a bottleneck in TB surveillance, particularly in resource-constrained regions. In response, we present a groundbreaking portable bio-tool, the lab-in-a-cartridge (LIC) system, designed for on-site detection of lipoarabinomannan (LAM) in trace amounts within the urine. The innovative design combines pumpless liquid handling and magnetic force-based enrichment with horseradish peroxidase polymer amplification to precisely quantify low biomarker levels. Employing a tetramethylbenzidine-based colorimetric reaction, the LIC enables semi-quantitative LAM detection. This LIC incorporates all necessary reagents, achieving a detection threshold of as low as 0.01 pg/mL in pooled urine samples within 40 minutes. The LIC distinguishes TB patients in clinical urine samples with 92% sensitivity and 88% specificity. This pioneering device not only sets an improved standard for detecting low LAM concentrations but also holds the potential to realize a decentralized diagnosis of TB.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a major challenge for public health worldwide, particularly in low-income and developing countries, where it ranks among the top ten causes of death1,2. The timely delivery of medication is crucial; delayed treatment initiation increases disease progression and development of complications which may lead to increased mortality3. Therefore, monitoring TB in low concentration is of great practical importance, and early detection sensors are drawing more and more attention. The World Health Organization (WHO) introduced the END TB strategy in 2014, aiming to eradicate TB4. In developed countries, many number of centralized medical facilities enable early detection and effective disease management5. Conversely, in developing countries, the scarcity of diagnostic facilities and limited access to healthcare services pose significant challenges to TB diagnosis and treatment6. This necessitates the development of point-of-care (POC) testing tools to support decentralized diagnostic approaches.

Currently, acid-fast bacilli (AFB) smear microscopy of sputum samples remains one of the most widely used methods for TB detection due to its simplicity and low cost7. This technique facilitates the direct visualization and detection of high bacterial loads; however, it is inadequate for detecting bacteria in the early stages of TB infection when bacterial counts are low8,9,10. In cases where initial tests are inconclusive, bacterial culture, considered as the gold standard, is performed to improve the detection of mycobacteria11,12. Nevertheless, it requires well-equipped laboratory infrastructure, takes several weeks to yield results, and incurs high operational costs13. To mitigate these limitations, nucleic acid amplification-based methods, which target the genetic material of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M.tb), offer superior sensitivity and specificity14,15. Despite these advantages, their dependence on sputum samples constrains their utility in patients unable to produce sputum, such as those coinfected with HIV and M.tb, individuals with extrapulmonary tuberculosis (EPTB), or pediatric TB cases16,17,18,19. The need for specialized equipment, such as thermocyclers, also hinders their widespread adoption in resource-limited settings20. PCR is well-established for TB diagnosis. It offers high sensitivity and specificity, with results available in a few hours. However, its high cost limits its widespread use in low-income countries (Supplementary Table 1)21.

To address the limited access of potential patients to traditional TB diagnostics, the WHO has advocated the development of POC tools for on-site and self-testing22,23. Numerous research teams have focused on developing POC tools targeting lipoarabinomannan (LAM), which have emerged as promising diagnostic alternative for meeting these criteria24. LAM, a lipoglycan found in the cell membrane of M.tb, is released into the bloodstream upon bacterial metabolism or degradation and can be detected in urine due to its small molecular size (17.4 kDa)25. The presence of LAM in urine is proportional to the bacterial load in the infected individual26. Urine-based LAM detection offer a non-invasive alternative to sputum or blood-based tests and is especially advantageous for patients unable to provide sputum samples, including individuals coinfected with HIV and TB, or those contracted with extrapulmonary TB (EPTB) or pediatric TB27,28,29,30. However, TB detection in HIV-negative patients using urine tests remains challenging due to the extremely low concentration of LAM in their urine. This low concentration hampers the identification of TB in HIV-negative patients with current POC methods, such as lateral flow immunoassays31,32,33. Although various studies have attempted to improve the sensitivity of LAM detection through sample processing or signal amplification, many of these methods rely on bulky or costly instrumentation, limiting their applicability in decentralized or resource-limited settings (Supplementary Table. 2)34,35,36,37,38,39. Therefore, there remains a critical need for portable, cost-effective, and highly sensitive diagnostic platforms capable of detecting low concentrations of LAM. Such tools would significantly improve early TB detection, particularly among vulnerable populations and in settings with limited access to centralized diagnostics.

Herein, we introduce a LIC for the detection of LAM in urine, enabling on-site and self-monitoring of TB. Figure 1a illustrates that the conventional TB diagnostic process involves multiple steps, including hospital visits, sample transportation, and bacterial culture in laboratory facilities. Typically, urine samples from suspected TB patients are collected and sent to healthcare centers, where they undergo bacterial culture and analysis—a process that takes 7 to 14 days. In contrast, the LIC system provides a rapid and efficient alternative, delivering results in less than 40 minutes. It leverages magnetic-based enrichment to concentrate LAM, horseradish peroxidase (HRP) polymers to amplify signal intensity, and a tetramethylbenzidine (TMB)-based colorimetric transducer for direct visual analysis without the need for additional signal processing equipment as shown in Fig. 1b. By integrating pumpless fluid actuation, magnetic capture, enzymatic amplification, and semi-quantitative visual readout in a fully self-contained platform, the LIC overcomes the key limitations of current LAM-based POC tests. This groundbreaking system also features a pumpless cartridge design that automates liquid handling, replicating complex laboratory procedures in a portable format. The semi-quantitative analysis can be performed with the naked eye by comparing color intensities in the control and target chambers, offering a user-friendly interface. The high sensitivity and enhanced reproducibility of the LIC, driven by its automated assay, represent a significant advancement over existing visual inspection methods. Especially in rural and underserved areas, the LIC is poised to make a substantial contribution to the decentralized monitoring of TB, aligning with the WHO’s END TB strategy.

a The conventional methods require significant hands-on sample treatment, leading to potential delays to diagnose for tuberculosis (TB). Created in BioRender. Jung, H. (https://BioRender.com/8rz9zwn). b Detailed illustration of the LIC detection process for TB from urine samples. After urine collection and pretreatment, magnetic enrichment occurs to capture the target TB biomarkers using magnetic particles. TMB catalytic reaction leads to a color change for TB-positive samples. The results could be semi-quantitatively analyzed by comparing the color between control and result chamber.

Result and discussion

Design of colorimetric assay for LAM detection

To address the challenge of analyzing urinary LAM below 10 pg/mL for point-of-care TB detection34,37,40,41,42, we applied magnetic force-based enrichment and a colorimetric signal-transducing method. This approach enhances sensitivity and cost-effectiveness by eliminating the need for bulky instrumentation. The assay steps for LAM detection are illustrated in Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 1. The magnetic beads (MB) were conjugated with a LAM antibody (Ab) by activating the amide bond between the carboxyl group on the MB surface and the amine group on Ab using ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC). We evaluated the antibody’s conjugation efficiency to the magnetic bead surface to maximize target capture (Supplementary Fig. 2). The efficiency gradually increased with the treated Ab concentration and became saturated above 0.4 mg/mL. Therefore, we determined the amounts of Ab treated on MB surface as 0.4 mg/mL. Salmon sperm DNA (SSD) was utilized as a blocking agent for preventing nonspecific absorption and 1 mg/mL of the blocker was selected for minimizing background signal that could interrupting detection with naked eye (Supplementary Fig. 3). Subsequently, LAM and an HRP–aptamer conjugate (H-apt) were introduced into the SSD–Ab–MB suspended matrix and a sandwich complex was generated by capturing LAM between SSD–Ab–MB and H-apt. Different amounts of H-apt deriving TMB reaction were explored after the formation of the sandwich complex (Supplementary Fig. 4). The absorbance at a wavelength of 280 nm was gradually increased after the binding of apt on LAM–SSD–Ab–MB complex because of the HRP and the highest value at 200 ng/mL was observed. Therefore, the H-apt of 200 ng/mL was utilized for the detection of LAM. Moreover, 0.5 % Tween 20 in 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was employed as a washing buffer for effective removal of unbounded H-apt and impurities (Supplementary Fig. 5). After removing the supernatant, the complex was suspended in the TMB solution. In the presence of HRP, TMB was oxidized to oxTMB, resulting in a color change from transparent to blue. The optimal reaction time was determined as 5 min generating the largest difference of color (Supplementary Fig. 6). Finally, the reaction was stopped by isolating the complex using magnetic force from the TMB solution and the LAM concentrations was semi-quantitatively measured by analyzing the degree of color change and absorbance of 650 nm wavelength.

a Schematic representation for generation of MB complex and TMB reaction for LAM detection. b Characterization of different assay steps of MB surface via UV–vis spectra absorbance at 260 nm, 280 nm, 650 nm. TEM image of (c) MB, (d) SSD–Ab–MB and (e) H-apt–LAM–SSD–Ab–MB using Ab and apt labeled with AuNPs with sizes of 60 and 20 nm, respectively (inset shows the corresponding high-magnification TEM images). f Calibration curves of UV-vis spectra at different concentrations of LAM in 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.4) and mixed urine (n = 20) at 650 nm, respectively. The LAM concentrations detected ranged from 10−2 to 103 pg/mL. g Specificity of the assay for LAM detection. Concentrations of 1.0 × 102 pg/mL for ESAT-6, IFN-γ, IL-2, TNF-α and 1.0 × 10−1 pg/mL LAM were utilized. h Selectivity of the assay for LAM detection. Concentrations of C. albicans, S. aureus, B. cereus, E. coli, S. enterica, P. putida, S. aeruginosa lysates are 1.0 × 107 pg/mL and 1.0 × 102 pg/mL M.tb lysate were utilized. i Specificity of the assay against cross-reactive. Concentration of 0.1 mg/mL for IgG, 3 mg/mL for glucose, 3 mg/mL for BSA, 0.3 mg/mL for albumin and 0.01 mg/mL for hemoglobin were utilized. j Specificity of the assay against endogenous interference. Concentration of 0.5 mg/mL for uric acid, 15 mg/mL for urea, 3 mg/mL for creatinine, 2.3 mg/mL for KCl, 1.26 mg/mL for NH4Cl, 1.75 mg/mL for NaCl, 1.75 mg/mL for CaCl2 were utilized. k Specificity of the assay against exogenous interference. Concentration of isoniazid, rifampicin and paracetamol were 30 µg/mL, while the ibuprofen was 5 µg/mL. A concentration of 1.0 × 101 pg/mL LAM was used in all interference tests (i–k). All data points and error bars correspond to average values and standard deviation obtained from four independent measurements. Data are presented as means ± standard errors of the mean. In the graph, asterisks indicate statistical significance as follows: ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001. Statistical analysis was conducted using a paired t-test.

Characterization of assay steps by exploring the different states of MB surface

After establishing the optimal assay conditions, we characterized each step of the assay by investigating the UV-vis absorption spectra (Supplementary Fig. 7, and Supplementary Fig. 8) and quantifying the absorbance at wavelength of 260, 280, and 650 nm, indicating the amount of nucleic acid, protein and oxTMB, respectively. The sequential treatment with Ab, SSD and H-apt led to increase of the absorbance at 260 and 280 nm owing to an increase in the number of resonance structures of purine, pyrimidine bases and aromatic chains on the amino acids such as tryptophan and tyrosine residues, respectively43,44 (Fig. 2b). The blue color (absorbance peak at 650 nm) was shown due to the oxTMB generated from the catalytic reaction45. The UV–vis spectra indicated that the colorimetric assay for LAM detection was successfully achieved.

Furthermore, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images were obtained to identify the immobilization of Ab on the MB surface and the formation of the sandwich complex. Due to the significant size disparity between the MBs (1 – 4 μm) and the bioreceptors (Ab: ~10 nm, aptamer: ~2 nm), distinguishing the bioreceptors on the MB surface in TEM images was challenging (Fig. 2c). To address this visualization challenge, gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) with sizes of 60 nm and 20 nm were conjugated to Ab and apt, respectively, for use as labels (Supplementary Fig. 9). The labeled bioreceptors were sequentially treated with bare MBs and LAM–SSD–Ab–MB complex. TEM images show the immobilization of Ab on the bead (Fig. 2d) and the formation of the complex (Fig. 2e) were successfully accomplished based on the presence of AuNPs on the bead surface. Additionally, the conjugated MB complexes were evaluated using dynamic light scattering (DLS) and zeta potential analysis to verify their structural stability (Supplementary Fig. 10).

Interference inhibition in assay of urine samples

We encounter the issue of derivation of high non-specific signal on the LAM assay in the case of using real urine samples. To address the issue, the materials that used in this study potentially leading to non-specific signal were investigated. Each step of MB complex treated with urine were monitored for the effect on non-specific signal. The color change occurred exclusively after the apt treatment step, confirming that it was due to the H-apt. (Supplementary Fig. 11). Consequently, to investigate the selectivity of Ab for substances other than LAM and the nonspecific adsorption of HRP to the bead surface due to urine components, we measured the changes in absorbance over time. (Supplementary Fig. 12). The difference in the rate of transition from TMB to oxTMB for PBS and urine indicates that the specificity of Ab is not a major cause of nonspecific signal (Supplementary Fig. 12a). Furthermore, the HRP non-conjugated with apt did not adsorbed on MB complex (Supplementary Fig. 12b). Therefore, we suspect that a certain substance in urine boosts the non-specific binding of apt to the bead surface. Next, we focused on the component of LAM with analogs. According to previous reports, LAM is a lipopolysaccharide that is primarily composed of sugar compounds, including arabinogalactan, mannose, and fatty acids46. The utilized Ab is reported to bind to the branched sections of LAM, specifically with Ara4 and Ara6 capped with Manp, and apt binds to mannan area47,48. As observed in previous experimental results, the H-apt nonspecifically binds to the surface of bead complex when actual urine is applied, leading to increased background noise. Based on this observation, it was deduced that certain substances in urine bind to the bead surface and also, the H-apt cross-reacts with these specific substances in urine. Compounds such as Mannan, N-acetyl-D (+)-glucosamine, and lactose, displaying glycan motifs similar to ManLAM, are known to participate in competition during the binding process of the apt49. Furthermore, the aforementioned sugar components are recognized to be present in urine in the following concentrations: 10–200 ng/mL glucosamine, 500–700 ng/mL mannose, 670–710 mg/L lactose, and 100–300 mg/L glucose50,51,52,53,54. Until now, no blocking agents have been reported to prevent the nonspecific adsorption of sugar compounds, leading us to select Concanavalin A (ConA) as a candidate to inhibit interference. The protein is known to bind specifically to the D-mannosyl and D-glucosyl groups of sugar, glycoprotein, and glycolipids48. Furthermore, the dissociation constant for each bioreceptor and ConA towards LAM showed that the two bioreceptors were 7–9 times more capable of effectively binding to the target substance compared with ConA, indicating their potential utility as inhibitors (Supplementary Table. 3). Based on this knowledge, we expect that ConA can prevent the non-specific adsorption of interferents and also hinder the binding of the H-apt (Supplementary Fig. 13a). To evaluate the feasibility of ConA as an inhibitor, LAM was added to pooled urine samples from TB-negative patients (n = 20) with various concentrations of ConA. The absorbance of the blank and the LAM of 1 ng/mL spiked in urine with ConA exhibited in Supplementary Fig. 13b. The blank and the target signal could be distinguished due to the ConA as an inhibitor in the range of 0.1–100 ng/mL. The discrepancy mostly expanded after treatment with 10 ng/mL of ConA, displaying that non-specific signals were effectively suppressed. Therefore, the ConA of 100 ng/mL was utilized as an inhibitor for quantifying LAM in a real urine sample.

Evaluation of assay performance

In order to eliminate the interference of non-specific signal in urine and maximize the assay performance of LAM in urine, the adjustment of MB concentration, various blocker, buffer for H-apt with various pH were conducted and explore the effect of pH on LAM detection (Supplementary Fig. 14, and Supplementary Fig. 15, Supplementary Fig. 16). As a result, the MB of 1 mg/mL (5.0 × 107 particles/mL), SSD and carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.6) shows large signal difference between blank and the target. Subsequently, the assay performance was evaluated by conducting absorbance measurement on serially diluted LAM in pooled urine added with 100 ng/mL of ConA in 0.1 M PBS. In addition, storage at 4 °C maintained the functional activity of the magnetic bead complex (SSD-Ab-MB) and H-aptamer for up to 14 days (Supplementary Fig. 17). Under the optimized experimental conditions, the analytical performance of the designed assay was evaluated by conducting absorbance measurement on serially diluted LAM in 0.1 M PBS and actual urine matrix. The absorbance peak obtained from the UV–vis spectra gradually decrease with declining concentrations of the LAM (Supplementary Fig. 18). Figure 2f shows the absorbance change is linearly related to the logarithms of each LAM concentration in 0.1 M PBS (R2 = 0.99) and pooled urine (R2 = 0.98). The limits of detection (LOD) of the constructed assay in 0.1 M PBS was estimated as 2.3 × 10−3 pg/mL and in actual urine matrix was 3.7 × 10−3 pg/mL with respect to the sum of the change in the current of the blank sample and three standard deviations. The LOD value implies that trace amounts of LAM can be detected in the urine of HIV-negative/TB-positive patients. In addition, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 19, the absorbance at 650 nm increased proportionally with LAM concentration from 1.0 × 10⁻² to 1.0 × 10³ pg/mL. Beyond this concentration, the signal reached a plateau, indicating saturation of the colorimetric response. Therefore, the detection range in this study was defined as 1.0 × 10⁻² to 1.0 × 10³ pg/mL, ensuring accurate quantification within the linear response region.

Evaluation of specificity and selectivity

To evaluate assay specificity, the signals for LAM at 1 × 10-1 pg/mL were compared with responses for four TB-related biomarkers at 100-fold excess concentrations (1 × 102 pg/mL)48,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58. These interferent biomarkers, even at 100-fold higher concentrations, produced signals nearly identical to the blank (Fig. 2g). Furthermore, LAM noticeable signal alterations of higher magnitudes, effectively separating it from interference. The signal differences were statistically significant (***p < 0.001) highlighting the excellent specificity of the assay for detecting LAM even in the presence of potential interference. To assess the selectivity of the assay in urine, the signals corresponding to 1.0 × 102 pg/mL of M. tb lysate were compared with those obtained from 105-fold excess concentrations (1.0 × 107 pg/mL) of lysates from seven bacteria commonly known for infecting human. The lysates of the bacteria were added to pooled urine and then utilized in the test. In pooled urine, bacterial lysates generated signals close to blank, whereas M. tb lysate induced a marked signal increase (Fig. 2h). This significant distinction (***p < 0.001) demonstrates the assay’s capability to selectively detect M.tb in urine, even with high concentrations of potentially interfering bacteria.

Furthermore, to comprehensively evaluate cross-reactivity and assay robustness, abundant urinary proteins and metabolites such as IgG, glucose, BSA, albumin, and hemoglobin were tested (Fig. 2i). Although these molecules are not structurally related to LAM, they are frequently present in urine and may cause nonspecific binding or affect the colorimetric readout. To further assess assay robustness, we evaluated potential interference from endogenous substances (Fig. 2j) (uric acid, urea, creatinine, KCl, NaCl, NH4Cl, CaCl2) and exogenous compounds (Fig. 2k) (isoniazid, rifampicin, ibuprofen, and paracetamol), which may be present in urine due to metabolic activity or pharmacological treatment. All substances were spiked into artificial urine samples, and no significant interference with the assay signal was observed under standard assay conditions.

Design and operation of LIC

The device was consisted with two main modules. One is assay operation module sequentially transporting the sample and reagent at a certain point of time. The other is power control module for revealing sequential transportation of liquid at desired time by inducing rotation of reaction cylinder (Fig. 3a). We incorporated the steps of the assay into a handheld device to realize the sample-to-answer detection of LAM in a short time (Fig. 3b). The combination of these two modules in this system could realize handheld type POC based detection of LAM and finally, we developed LIC. The magnetic-force-based enrichment and direct visual readout from the catalytic reactions of TMB with HRP were followed by the rotation of the reaction cylinder (Fig. 3c, and Supplementary Fig. 20, Supplementary Fig. 21)). After a user introduced the reaction mixture containing a urine sample into the sample chamber, the cartridge was activated by winding the switch on the device. The gear system delivered constant power for rotating the reaction cylinder. During the rotation of the cylinder, the reaction mixture containing the MB sandwich complex with LAM was introduced into the reaction channel under gravity, and the complex was enriched. Subsequently, the washing buffer flushed out unbound H-apt and other irrelevant materials. Next, the TMB solution was added to the MB complex attached to the channel, and the HRP on the complex triggered the oxidation of TMB to oxTMB. Finally, the reactant was separated from the complex by transferring the solution into the detection chamber (Supplementary Fig. 22, and Supplementary Table. 4, Supplementary Video). We detected the presence of LAM by comparing the color changes in the detection and control chambers through visual observation. Furthermore, we minimized the unit cost of the device by making the assay operation module disposable and detachable from the combination of the converter and power control module. Therefore, the unit cost for test could be minimize facilitating the on-site detection of TB, particularly in underdeveloped regions (Supplementary Fig. 23, Supplementary Fig. 24).

a The main components of LIC and (b) dimensions of the cartridge. c Schematic illustration of workflow for the detection conducted sequentially in assay operation module. The LAM detection could be started by adding reaction mixture into sample chamber from collection tube containing urine sample. The cartridge operation is initiated by winding up the switch and the gear system deliver constant power for rotating reaction cylinder. The rotation of the cylinder induces the enrichment of MB complex at the bottom of the channel located in the cylinder. Subsequently, the wastes and unbound apts are flushed out by using washing buffer transported from gravity. Next, the TMB reaction is derived by delivering TMB solution in the channel and it trigger oxidation of TMB. The blue color deepens as the number of oxTMB molecules increases. After the reaction cylinder is rotated for 5 min, the TMB solution is transported to the detection chamber to separate it from the complex. d Rack gear force at different angles of main gear. Each data point represents the mean ± SD of five independent technical replicates (n = 5), with each replicate corresponding to a distinct device. Error bars indicate standard deviation (SD). Measurements were collected at multiple angles, with each device as the independent experimental unit. e Angular velocity at different angles of the reaction cylinder. Data points show mean ± SD from five independent replicates (n = 5), each performed on a distinct device. Error bars indicate SD. Measurements were acquired at multiple time points, with each device as the independent experimental unit. f Leakage rate and contamination rate for operating cartridge by using various sealing methods. Data points show mean ± SD from five independent replicates (n = 5), each corresponding to an independent sealing assembly. Error bars indicate SD.

Investigation of fluid movement in LIC

To maximize the washing effect in the channel of reaction cylinder, we employed a two-stage cleaning strategy and investigated the flow velocity driven by gravity at channel in reaction cylinder by using computational fluid dynamics simulations (Supplementary Fig. 25, and Supplementary Fig. 26). The enrichment of MB complex takes place at the bottom of the channel where the magnet is located, leading to a stronger washing effect at the site of enrichment as the velocity of the fluid passing through the channel increases. Therefore, the flow velocity distribution across different channel widths was investigated, and the simulated result showed that wider channels lead to weaker forces of surface tension acting on the flow of the fluid, thereby accelerating the flow velocity. Furthermore, to enhance slipperiness by increasing the hydrophobicity of the channel walls, silane was applied at varying concentrations, and the contact angle was analyzed (Supplementary Fig. 27). The contact angle became saturated at 0.5 % silane treatment, also it led to remove the fluid retention rate on channel wall (Supplementary Fig. 28). Additionally, to evaluate the mechanical functionality of the engineered POC tool, we investigated the consistency of rack gear force and angular velocity in the reaction cylinder (Fig. 3d, e) and confirming both the rack gear force and angular velocity displayed gradients within the permissible tolerance ranges at various angles. Besides, in order to prevent fluid leakage and cross-contamination of reagents between chambers during the operation of LIC, four types of sealing methods were compared (Fig. 3f, and Supplementary Fig. 29, Supplementary Fig. 30). Reagent leakage did not occur during the operation when capillary slots and polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) seals were used. However, only PDMS seals showed no leakage and contamination rates owing to their elasticity, which enabled them to fill the small gaps between the surfaces.

Analytical performance of LIC

The internalization and automated operation of the developed assay using the LIC are demonstrated by employing pooled urine samples. To enhance the applicability of the LIC for decentralized testing, pooled urine samples were initially pretreated through syringe filtration, which allowed for the removal of excessive interference. The preprocessed samples were incubated for 10 min with reagents containing H-apt, functionalized MB, and ConA. Subsequently, they were injected into the cartridge, and when the device operation was completed, we assessed the results shown on the target chamber in the detection part. As observed in the detection part of the LIC, the amount of oxTMB transferred to the target chamber increased with the LAM concentration, resulting in a deeper blue color (Fig. 4a). The color intensity in the control chamber was engineered such that the threshold value of the absorbance obtained from the assay of urine samples was 0.16 OD. In addition, the analysis of the reactant absorbance in the target chamber showed a linear range. Notably, the assay for LAM detection showed lower standard deviation values compared with manual assays (Fig. 4b). This indicates that the capacity of the device for automatic detection could reduce signal variability, which probably occurred during manual testing, while improving accuracy (Fig. 4c, d). Intra- and inter-assay variations were examined to determine the reproducibility of the biosensor. Under optimal conditions, the relative standard deviation (RSD) was evaluated four times using LAM of 1.0 × 10−2 pg/mL. The RSDs of the intra- and inter-assay variations were estimated to be 4.60 % (n = 4) and 3.84 % (n = 4), respectively (Fig. 4e). To further confirm the robustness and consistency of the LIC system, Supplementary Fig. 32 presents a lot‑to‑lot variability assessment. To evaluate batch consistency, three independent lots were tested using LAM samples at concentrations of 0.01, 1, and 100 pg/mL (n = 10 per lot). The absorbance values showed no significant differences among the batches, with coefficients of variation below 5%, indicating the robust and reproducible performance of the LIC. Hence, the obtained results endorse the reliable repeatability and reproducibility of the proposed strategy.

a Schematic drawing and image of detection part at the end of LIC operation for different concentrations of LAM (1.0 × 10−2 – 1.0 × 103 pg/mL) in pooled urine (n = 20). The generated color of control chamber designed for representing threshold value of the blank (0.16 OD). b Corresponding calibration plot of oxTMB absorbance extracted from LIC. Dashed line represents a blank value. c Comparison for repeatability and (d) reproducibility of manual detection and utilization of LIC by using 1.0 × 10−2 pg/mL of LAM. Boxplots show absorbance values (650 nm) measured by manual assays and LIC. Medians are indicated by center lines; boxes denote interquartile ranges (IQR, 25th–75th percentile), and whiskers extend to the most extreme values within 1.5 × IQR. Each data point represents one independent replicate measurement. The left panel illustrates variability across five test batches, while the right panel shows measurements from five consecutive assay days. e Inter-, intra- analysis of the assay for LAM detection by using LIC. All the data points and error bars correspond to average values and standard deviation obtained from four independent measurements.

Clinical validation of LIC

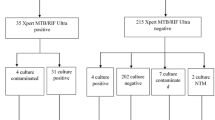

After confirming the LIC’s utility for applying LAM detection in urine, we explored the practical feasibility of the LIC using clinical urine samples obtained from 60 TB-positive and 40 TB-negative patients. All the patients were HIV-negative, and the urine samples of the TB patients were collected while they underwent microbiological examinations. The LIC exhibits the fastest detection rate from urine samples to answer than other conventional tuberculosis detection methods (Fig. 5a). Figure 5b shows the quantitative results of the absorbance for these clinical samples using the developed device. Although both methods were based on TMB chromogenic reactions, the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was only able to yield positive results ( > 0.1 OD) in two out of 60 positive samples and exhibited low absorbance values, whereas significantly stronger signals were observed with LIC (Supplementary Fig. 33). The difference in signals indicated that when compared to the surface area available for capturing biomolecules on ELISA plates, the area of the MB-based assay used inside the LIC is about 20 times larger, leading in more amount of target capture. Additionally, the polymer form of HRP used further induced more oxTMB transitions, thereby secondarily amplifying the signal and contributing to the observed difference in signal intensity. The results from the LIC were verified by comparison with the multiple clinical diagnostic results using ELISA for targeting LAM, mycobacterial cultures, AFB smear result (Supplementary Table. 5). The cut-off of absorbance values was determined as 0.16 OD for distinguishing between non-TB patients and TB patients in order to enhance diagnostic accuracy and specificity and also, this value was almost similar with LOD of LIC. Employing the established cut-off value, LIC was able to distinguish 35 of 40 non-TB patients and 55 of 60 TB patients, with LAM results from 90/100 samples aligning with the clinical diagnosis representing that the LIC play a significant role in auxiliary diagnosis. The clinical samples were further examined with naked eye observing the detection chamber of LIC. The signal difference was observed in urine samples between TB-positive and TB-negative patients (Supplementary Fig. 35). The degree of color changes of urine samples from non-TB patients were lower compared to those of urine samples from TB patients and also lower than the control chamber. These results confirmed that the semi-quantitative differentiation method based on naked-eye observation can also be effectively utilized for the analysis of LAM in clinical urine samples. Furthermore, the positive or negative results of LAM detection by using LIC and ELISA were compared to conventional methods with AFB smear, culture, and RT-PCR results from 40 TB-positive patients and 20 TB-negative patients uninfected from HIV (Fig. 5c). Only 2 positive cases could be discerned by ELISA. However, RT-PCR distinguish all 60 number of TB-positive, negative patients. Also, the observed result of AFB smear and culture shows 31/40 and 38/40 positive, respectively, and also the 20/20 negative result. Furthermore, LIC could determine 38/40 positive and 18/20 negative results presenting the utility of the proposed monitoring tool for TB testing. Moreover, the diagnostic value and application potential of LIC were further investigated in 23 clinical urine samples from 3 HIV, TB co-infected patients, 10 HIV-negative/TB-positive patients, and 10 HIV-negative/TB-negative patients. The results are shown in Fig. 5d and suggest that those who are co-infected had higher levels of LAM detected. Although more number of samples investigations are required for HIV-positive/TB-positive patients due to the low case of samples, the observed results highlight the significance of identifying LAM at low concentrations and throughout a wide range for patients with both HIV-positive/TB-positive and HIV-positive/TB-negative patients. As for the clinical diagnostic efficacy, the result for LAM detection of all the enrolled cases are shown in Fig. 5e. Our LAM detection method shows sensitivity of 92 % (55/60) for confirmed TB (culture-positive) with in non- TB patients of 88 % specificity (35/40) with a cut-off value of 0.16 OD. The receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) curves are shown in Fig. 5e. The area under the curve (AUC) was 0.91 when the controls were only non-TB patients. Compared to other methods, the method presented in this study was found to possess the highest sensitivity, fulfilling criteria recommended by the WHO’s END TB strategy (sensitivity > 90%, specificity > 70%) (Fig. 5f).

a The detection rates compared between LIC and other conventional detection methods. Created in BioRender. Jung, H. (https://BioRender.com/8rz9zwn.) b Absorbance value of LIC and ELISA. c Heatmap for distinguishing result of ELISA, AFB smear, culture and LIC. d Boxplots comparing the results of LAM test enrolled clinical HIV-positive/TB-positive, HIV-negative/TB-positive, and HIV-negative/TB-negative patients. Medians are indicated by center lines; boxes denote interquartile ranges (IQR, 25th–75th percentile), and whiskers extend to the most extreme values within 1.5 × IQR. Statistical comparisons were performed using two-tailed t-tests. Sample sizes were 3 patients for the HIV-positive/TB-positive group and 10 patients each for the HIV-negative/TB-positive and HIV-negative/TB-negative groups. Each data point represents one patient. The HIV-negative/TB-negative group served as the negative control. e Receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) of LAM detection and comparison of diagnostic values obtained using ELISA, AFB smear, culture and LIC. f Performance summary of various methods for detecting M.tb.

Discussion

In this study, we introduced a highly sensitive POC platform for detecting LAM in urine, enabling decentralized visual inspection for TB diagnosis. Utilizing magnetic force-based enrichment and HRP polymers, we achieved LAM detection from femtogram to picogram levels. Incorporating ConA as an inhibitor successfully mitigated non-specific signals from sugar compound acting as interferences within the urine matrix, exemplifying an effective strategy to prevent non-specific adsorption of saccharides. The results demonstrated the LOD of 3.7 fg/mL, identifying LAM at concentrations as low as 10 fg/mL in HIV-negative/TB-positive patients. Moreover, the automated analysis using the LIC enabled real-time, field-based testing and simultaneously facilitated semi-quantitative interpretation by comparing target and control signals. The LIC exhibited 92% sensitivity and 88% specificity in the case study involving 103 clinical samples, indicating its suitability for decentralized TB monitoring. Additionally, its portability and low cost make it ideal for low-resource settings, potentially increasing testing rates and contributing to TB eradication efforts. The LIC aligns with the WHO’s END TB strategy, offering an accessible, efficient, and affordable diagnostic method, transforming TB diagnostics in developing countries. It surpasses existing portable diagnostic tools in sensitivity and affordability, eliminating the necessity for expensive equipment and specialized laboratory infrastructure. The enhancement is particularly beneficial to detect LAM in HIV-negative /TB-positive patients with low concentrations. The LIC introduces a practical and innovative approach for TB diagnostics, aiming to improve sensitivity and specificity, explore additional biomarkers, expand its application to other infectious diseases, and broaden the impact of global health. However, one limitation of this study is the limited number of HIV-positive patients included in the clinical validation. Given the promising sensitivity of our assay, future efforts will aim to recruit a larger cohort of HIV-positive individuals, including both TB-positive and TB-negative cases, to further validate the clinical performance in this high-priority population.

Methods

Materials

Streptavidin-poly HRP, 5,5′-Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB), ethanolamine, casein, bovine serum albumin (BSA), Tween-20 solution, 1H,1H,2H,2H-perfluorododecyl trichlorosilane, interferon-γ (IFN-γ), interleukin-2 (IL-2), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and Concanavalin A were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (USA). Carboxylated magnetic bead (MB) and 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC) were provided from ThermoFisher (USA). The DNA oligonucleotides (5’ –GGCGCCATAGCGACGGGGCCATTCCAAGAA -3’)53 tagged with biotin at 5’ terminal end were synthesized and purified by BIONEER (Republic of Korea). The CS-40 LAM antibody was generated by fusing splenocytes from immunized mice with myeloma cells in vitro to produce hybridoma cells, which were then cultured to secrete the antibody. The LAM antigen derived from the cell wall of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv and the M. tuberculosis lysate were acquired from BEI Resources (USA). ELISA kit for LAM was supplied from Mybiosource (Canada). Artificial urine was attained from Biochemazone™ (Canada). SLA and PLA resin for cartridge fabrication by using 3D printer were obtained from ANYCUBIC (England). Syringe filter with 0.22 μm pore size was provided from Millipore (USA). HFE7500 oil, 5 T polycarbonate (PC) plate were purchased from 3 M (USA). Gold nanoparticles with 20 nm and 60 nm size were provided from BBI Solutions (UK). ESAT-6 was supplied from PROSPEC (Israel). Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) and curing agent were delivered from Sewang Hitech (Republic of Korea). Bacteria species except for M.tb were obtained from the Korean Collection for Type Culture (Republic of Korea).

Preparation of functionalized MB and H-apt for capturing of LAM

The carboxyl group coated MBs of 2 mg/mL were completely dispersed in 0.1 M MES buffer (pH 4.7). Next, Ab (2 mg/mL) and EDC (10 mg/mL) were subsequently added and the mixture was shacked for 2 h at room temperature. After isolating the MBs using a magnet, the remaining EDC and antibody were eliminated. The MBs were washed three times with 0.1% Tween 20 in 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.4) and subsequently, the MBs treated with 1 mg/mL of SSD were mixed for 1 h at RT and then, the functionalized MB were washed three times from the 0.1% Tween 20 in 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.4). At the same time, the generation of H-apt was implemented by conjugating the 10 μM biotinylated apt and the 10 μM streptavidin conjugated poly-HRP through streptavidin-biotin binding in a ratio of 1 to 1 at RT for 30 min to achieve the HRP labeled apt. The H-apt was diluted to 0.1 μM with 0.5 % Tween 20 in 0.1 M carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.6).

Formation of sandwich complex by LAM capture and derivation of TMB reaction

In order to generate sandwich complex by capturing LAM between functionalized MB and H-apt, LAM and 0.1 μM of H-apt were added on the functionalized MB after washing steps. After 15 min of incubation, the generated MB complexes were washed three times with 0.1% Tween 20 in 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.4) and the TMB solution of 100 μL was sequentially added on the isolated complexes for 5 min. The absorbance of supernatant containing oxTMB at 650 nm wavelength was measured by using MMR Infinite® 200 Pro (TECAN, Swiss).

UV-spectra and TEM analysis of bead surface

The modification of MB surface from Ab conjugation to formation of sandwich complex and TMB reaction were investigated by UV-vis absorption spectra. The absorbance of the MBs at each step in the assay between 220 – 800 nm wavelength was estimated at 25 repeated number of scans. Furthermore, the surface of the beads at each step was evaluated by TEM images. Furthermore, in order to identify the conjugation of Ab and apt, the AuNPs of 60 nm were tagged on Ab and the AuNPs of 20 nm were tagged on apt through streptavidin-biotin bonding. The carbon meshed TEM grids (Electron Microscopy Science, USA) were prepared by drop-casting the solution of MB, Ab-MB, H-apt-LAM-Ab-MB. The morphology analysis was conducted with an accelerating voltage of 100 kV by using JEM-F200 (JEOL, Japan).

Exploration of specificity of the LAM assay

The assay specificity was explored by utilizing biomarkers of TB. ESAT-6, IFN-γ, IL-2, TNF-α for 1.0 × 102 pg/mL and 1.0 × 10−1 pg/mL of LAM were prepared in 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.4). Each biomarker was incubated with functionalized MB and H-apt for 10 min and washed three times with 0.1% Tween 20 in 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.4). The TMB solution of 100 μL was sequentially added on the isolated complexes for 5 min and sequentially, the absorbance of supernatant containing oxTMB at 650 nm wavelength was measured.

Assessment of potential interferences in the LAM assay

Based on the classification of potential interferents, three separate experiments were designed and conducted to evaluate the effects of (1) cross-reactive proteins and metabolites, (2) endogenous urinary substances, and (3) exogenous drugs on the LAM assay. The cross-reactive proteins and metabolites (IgG at 0.1 mg/mL, BSA at 3 mg/mL, albumin at 0.3 mg/mL, hemoglobin at 10 µg/mL, and glucose at 3 mg/mL) and exogenous drugs (isoniazid, rifampicin, paracetamol at 30 µg/mL each; ibuprofen at 5 µg/mL) were prepared in artificial urine. Endogenous urinary substances (uric acid, urea, creatinine, K+, NH₄+, Na+, and Ca+ at physiologically relevant concentrations) were prepared in 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.4). Each interference component was incubated with functionalized MB and H-apt for 10 min, followed by three washing steps using 0.1% Tween-20 in 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.4). Subsequently, 100 µL of TMB substrate solution was added and incubated for 5 minutes and measured the absorbance of supernatant containing oxTMB at 650 nm wavelength.

Urinary LAM detection by using TMB reaction

The various concentrations of LAM were prepared by diluting in pooled urine (n = 20) with 1:9 ratio. Subsequently, in order to specifically capture LAM from H-apt and functionalized MB, the spiked LAM of 20 μL is added to reaction mixture of 180 μL consisted with the 2 mg/mL functionalized MB, 0.1 μM H-apt and 100 ng/mL ConA with 0.1 % Tween 20 in 0.1 M carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.6). The sandwich complex was generated by incubating the mixture for 10 min at RT. The complex was washed three times from the 0.1 % Tween 20 in 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.4). Subsequently, the catalytic reaction was initiated by adding the TMB solution of 100 μL on the isolated complex. After 5 minutes of reaction, the solution was separated from the complex by using magnetic force leading to terminate the transition from TMB to oxTMB. Finally, the degree of the color change was investigated through absorbance measurement at 650 nm wavelength.

Selectivity validation of the assay in urine

We employed others samples of seven bacteria (C. albicans, S. aureus, B. cereus, E. coli, P. putida, and S. aeruginosa), which were cultured overnight at 37 °C in lysogeny broth (LB) culture media. After bacteria cultivation, the samples were centrifuged at 9000 g for 5 min and placed at 0.1 M PBS. Subsequently, the bacteria were sonicated with 3 cycles of 15 seconds on, 5 seconds off, at 20% power and the samples were centrifuged at 15,000 g for 5 minutes. The lysates were resuspended in 0.1 M PBS and prepared as 1 mg/mL from measuring the absorbance at 280 nm by using Nanodrop 2000 (ThermoFisher, USA). All the lysates were prepared at 1 mg/mL and diluted to a concentration of 1.0 × 107 pg/mL. M.tb lysate was further diluted to 1.0 × 102 pg/mL and all the lysates were spiked in pooled urine (n = 20). The spiked samples of 20 μL were added into reaction mixture of 180 μL and incubated 10 min. After 3 times of washing steps the TMB reaction was derived and the absorbance measurement at 650 nm was conducted.

Cartridge construction for internalization of LAM detection assay and on-cartridge detection

The cartridge is modeled by Inventor (Autodesk, USA) 3D CAD software. The gear and the frame except for assay operation module were realized by fused filament fabrication (FFF) 3D printer (Sindoh, Republic of Korea) with polyactic acid (PLA) as a raw material for printing. Each part of assay operation module was fabricated by liquid-crystal display (LCD) based 3D printer (Sindoh, Republic of Korea) with photoresin (ANYCUBIC, China) (Supplementary Table. 6). The printed components can be assembled through the slots. To create the water-repellent surface on each internal structure of the assay operation module, 0.5 % (w/v) of 1H,1H,2H,2H-perfluorododecyl trichlorosilane dissolved in HFE7500 oil was applied and incubated for 3 min. Subsequently, any remaining hydrophobic solution was washed away using HFE750 oil and stored in a dry oven (65 °C) until further use. The sealing part of the device is made of PDMS (polydimethylsiloxane). PDMS is hydrophobic, has a high contact angle of 112°, and has a low water absorption of 0.1 v/v59, which can minimize sample loss from the contact surface and solution residue in the channel. First, the PDMS mold was fabricated by CNC machining (KANGINTECH, Republic of Korea) a 5 T polycarbonate (PC) plate. Inventor CAM (Autodesk, USA) were used for modeling and generate g-code for CNC. PC has a high heat distortion temperature of 130 °C, making it suitable for use as a PDMS mold cured at 80 °C, and has excellent transparency, making it easy to check internal bubbles60. Subsequently, PDMS and curing agent were mixed at a mass ratio of 10:1 and cured on a hot plate at 80 °C for 4 hours. The PDMS mixture was degassed in a vacuum chamber for 30 min before and after pouring into the mold to completely remove internal air bubbles (Supplementary Fig. 31). PDMS seals are inserted on each of the two contact surfaces, of the upper module and cylinder, and between the cylinder and lower module, fixed to each module by concavo-convex structure. Sealing on all four sides prevents fluid loss from the surfaces through a gasket-like structure. In order to prevent the solution from remaining in the channel due to capillary force when the spinner moves, the sealing has a thickness of 2 mm. In addition, silicone oil, which does not react with the solution, is applied to both sides to enhance waterproofing and lubrication. Construction of the whole body for cartridge was completed by assemble aforementioned parts with 5 V stepper motor controlled by Arduino Nano (Arduino, Italy).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for LAM detection

The LAM ELISA kit was used for LAM detection according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, the standard or urinary LAM of 100 µL was added per well with HRP-conjugate reagent and the plate was incubated at 37 °C for 60 min. Next, each well was washed four times with wash buffer and 50 µL of chromogen solution A and chromogen solution B were dispensed per well. The plate was incubated at 37 °C for 15 min in the dark and 50 µL of stop solution were added. The absorption at 450 nm was measured and the samples were analyzed in single replicate. Cut-off were used as 0.1 OD recommended by the manufacturer.

Clinical validation and usability assessment of LIC

Clinical urine samples from TB patients were collected with approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Yonsei University (IRB, No. 7001988-202305-BR-1904-01E) and the Institutional Review Board of Yonsei University College of Medicine (IRB, No. 4-2023-1041). Two milliliters of each urine sample was filtrated through syringe filter of 0.22 μm pore size for removing the impurities or undesirable components (e.g., suspended particulates and certain large protein complexes) in urine sample. The samples were divided into aliquots and stored at -80 °C to avoid frequent freeze-thaw cycles. Then, these pretreated 20 μL of urine samples was added to the sample tube and incubated with reaction mixture for 10 minutes. Subsequently the reaction mixture was added in the sample chamber of LIC and the cartridge operations was initiated by clicking the button. After the operation was finished the reagents at control and target chamber were semi-quantitatively analyzed by comparing the color of the two chambers. Additionally, the transported solution in the target chamber were further explored by measuring absorbance at 650 nm wavelength. Healthy controls were individuals without symptoms of active tuberculosis (ATB) and no recent history of contact with confirmed TB patients. To exclude both latent and active TB infection, all healthy controls had a negative interferon-gamma release assay (QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube, QFT-GIT), showed no abnormalities on chest X-ray, and had no prior history of TB diagnosis or treatment. In parallel, a preliminary usability assessment was conducted in a resource-limited field setting (Collaboration with local hospitals in Timor-Leste) to evaluate the system’s practical deployment potential. A total of 100 participants (10 healthcare workers and 90 laypersons) were recruited. After brief training, participants independently performed the LIC assay and completed a structured questionnaire assessing clarity of instructions, ease of use, and result interpretation. The system received a 90% satisfaction rate overall. These findings suggest that the LIC system is suitable for use by minimally trained individuals in field settings. The survey results are summarized in Supplementary Fig. 34.

Statistical analysis

The data presented in this study have been expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (n = 5). Statistical analysis was conducted using a paired t-test. Results were interpreted based on the data with a p value < 0.05. In the graph, asterisks indicate statistical significance as follows: ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001. On the other hand, a p-value greater than 0.05 was considered non-statistically significant and represented as “ns”.

An a priori power analysis was performed using G*Power (version 3.1.9.4) to estimate the minimum sample size required for comparing TB-positive and TB-negative groups. Based on a two-tailed t-test, a large effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.8), significance level α = 0.05, and statistical power of 90%, the required sample size was calculated to be 34 participants per group (total n = 68). This ensures sufficient power to detect meaningful differences between the two groups with high confidence.

Ethical approval

Every experiment involving clinical samples has been carried out following a protocol approved by an ethical commission. The participants were recruited within the hospital setting, and no specific information on sex, gender, race, or ethnicity was collected. Roles and responsibilities were agreed amongst collaborators ahead of the research. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Yonsei University (IRB, No. 7001988-202305-BR-1904-01E) and the Institutional Review Board of Yonsei University College of Medicine (IRB, No. 4-2023-1041). The IRB protocol is provided in the Supplementary Information file.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary files. Any additional requests for information can be directed to and will be fulfilled by the corresponding authors. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Custom-written codes used to operate the LIC from this study are available from the GitHub: (https://github.com/phil9899/Operate-for-LIC/blob/main/LIC%20operate).

References

Floyd, K., Glaziou, P., Zumla, A. & Raviglione, M. The global tuberculosis epidemic and progress in care, prevention, and research: an overview in year 3 of the End TB era. Lancet Respir. Med. 6, 299–314 (2018).

Skeiky, Y. A. W. & Sadoff, J. C. Advances in tuberculosis vaccine strategies. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 4, 469–476 (2006).

Tedla, K., Medhin, G., Berhe, G., Mulugeta, A. & Berhe, N. Delay in treatment initiation and its association with clinical severity and infectiousness among new adult pulmonary tuberculosis patients in Tigray, northern Ethiopia. BMC Infect. Dis. 20, 1–10 (2020).

Uplekar, M. et al. WHO’s new End TB Strategy. Lancet 385, 1799–1801 (2015).

Tokel, O., Inci, F. & Demirci, U. Advances in plasmonic technologies for point of care applications. Chem. Rev. 114, 5728–5752 (2014).

World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2022. (World Health Organization, Geneva, 2022).

Al-Moamary, M. S., Black, W., Bessuille, E., Elwood, R. K. & Vedal, S. The Significance of the Persistent Presence of Acid-fast Bacilli in Sputum Smears in Pulmonary Tuberculosis. Chest 116, 726–731 (1999).

Putra, O., Damayanti, A., Nurrahman, N., Devi, T. & Aluf, W. Evaluation of category I of anti-tuberculosis therapy in intensive phase pulmonary TB by conversion of acid-fast bacilli sputum. Pharm. Sci. Res. 6, 3 (2019).

Siddiqi, K., Lambert, M.-L. & Walley, J. Clinical diagnosis of smear-negative pulmonary tuberculosis in low-income countries: the current evidence. Lancet Infect. Dis. 3, 288–296 (2003).

Fu, H.-T., Tu, H.-Z., Lee, H.-S., Lin, Y. E. & Lin, C.-W. Evaluation of an AI-based TB AFB smear screening system for laboratory diagnosis on routine practice. Sensors 22, 8497 (2022).

Heyckendorf, J., Gillespie, S. H. & Ruhwald, M. Culture-free proof of Mycobacterium tuberculosis - a new assay for viable bacteria. eBioMedicine 62, 103117 (2020).

Hamdi, A., Fida, M., Deml, S. M., Abu Saleh, O. & Wengenack, N. L. Utility of Mycobacterium tuberculosis PCR in ruling out active disease and impact on isolation requirements in a low prevalence setting. J. Clin. Tuberc. Other Mycobact. Dis. 21, 100181 (2020).

Yang, H. et al. A rapid, accurate, and low-cost method for detecting Mycobacterium tuberculosis and its drug-resistant genes in pulmonary tuberculosis: Applications of MassARRAY DNA mass spectrometry. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1093745 (2023).

Jaroenram, W. et al. Ultrasensitive detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by a rapid and specific probe-triggered one-step, simultaneous DNA hybridization and isothermal amplification combined with a lateral flow dipstick. Sci. Rep. 10, 16976 (2020).

Yee, E. H. & Sikes, H. D. Polymerization-based amplification for target-specific colorimetric detection of amplified Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA on cellulose. ACS Sens 5, 308–312 (2020).

Musisi, E., Ssesolo, A., Sloan, D. J., Gillespie, S. H. & Sabiiti, W. Detection and quantification of viable mycobacterium tuberculosis bacilli in saline-processed stool samples by tuberculosis molecular bacterial load assay: a potential alternative for processing stool. Microbiol. Spectr. 10, e00274–22 (2022).

Martino, R. J., Chirenda, J., Mujuru, H. A., Ye, W. & Yang, Z. Characteristics indicative of tuberculosis/HIV coinfection in a high-burden setting: lessons from 13,802 incident tuberculosis cases in Harare, Zimbabwe. Am. J. Tropical Med. Hyg. 103, 214–220 (2020).

Sharma, S. K., Mohan, A. & Kohli, M. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Expert Rev. Respir. Med. 15, 931–948 (2021).

Gopalaswamy, R., Dusthackeer, V. N. A., Kannayan, S. & Subbian, S. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis—an update on the diagnosis, treatment and drug resistance. J. Respir. 1, 141–164 (2021).

Weiss, D. J. et al. Global maps of travel time to healthcare facilities. Nat. Med 26, 1835–1838 (2020).

Rozales, F. P., Machado, A. B. M. P., De Paris, F., Zavascki, A. P. & Barth, A. L. PCR to detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis in respiratory tract samples: evaluation of clinical data. Epidemiol. Infect. 7, 1517–1523 (2014). 142.

Bulterys, M. A. et al. Point-of-care urine LAM Tests for tuberculosis diagnosis: a status update. J. Clin. Med. 9, 111 (2020).

High priority target product profiles for new tuberculosis diagnostics: report of a consensus meeting. Report of a consensus meeting. (World Health Organization, Geneva, 2014).

Flores, J., Cancino, J. C. & Chavez-Galan, L. Lipoarabinomannan as a point-of-care assay for diagnosis of tuberculosis: how far are we to use it? Front. Microbiol. 12, 638047 (2021).

Amin, A. G. et al. Urine lipoarabinomannan in HIV uninfected, smear negative, symptomatic TB patients: effective sample pretreatment for a sensitive immunoassay and mass spectrometry. Sci. Rep. 11, 2922 (2021).

Cantera, J. L. et al. Isolation and purification of lipoarabinomannan from urine of adults with active TB. Int. J. Tuberculosis Lung Dis. 27, 75–77 (2023).

Ketema, W. et al. A breakthrough in the challenges of tuberculosis diagnosis: lateral flow urine lipoarabinomannan (LAM) assay for the diagnosis of active tuberculosis in a subset of human immuno deficiency virus (HIV) patients at Hawassa University Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Hawassa, Ethiopia. IMCRJ 15, 393–397 (2022).

Shapiro, A. E. et al. Complementary nonsputum diagnostic testing for tuberculosis in people with HIV using oral swab PCR and urine lipoarabinomannan detection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 60, e00431-22 (2022).

Magni, R. et al. Lipoarabinomannan antigenic epitope differences in tuberculosis disease subtypes. Sci. Rep. 10, 13944 (2020).

Zheng, W. et al. Diagnosis of paediatric tuberculosis by optically detecting two virulence factors on extracellular vesicles in blood samples. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 6, 979–991 (2022).

Puspita, S., Turbawaty, D. K., Tristina, N. & Lismayanti, L. Positive lateral flow urine lipoarabinomannan assay (LF-LAM) result in detection of active tuberculosis. Maj. Kedokt. Bdg. 53, 169–173 (2021).

Connelly, J. T. et al. Field evaluation of a prototype tuberculosis lipoarabinomannan lateral flow assay on HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients. PLOS ONE 16, e0254156 (2021).

Bjerrum, S. et al. Lateral flow urine lipoarabinomannan assay for detecting active tuberculosis in people living with HIV. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 10, CD011420 (2019).

Divagar, M., Bandaru, R., Janakiraman, V. & Sai, V. V. R. A plasmonic fiberoptic absorbance biosensor for mannose-capped lipoarabinomannan based tuberculosis diagnosis. Biosens. Bioelectron. 167, 112488 (2020).

Owens, N. A. et al. Detection of the tuberculosis biomarker mannose-capped lipoarabinomannan in human serum: Impact of sample pretreatment with perchloric acid. Analytica Chim. Acta 1046, 140–147 (2019).

Wang, L., Leng, C., Tang, S., Lei, J. & Ju, H. Enzyme-free signal amplification for electrochemical detection of Mycobacterium lipoarabinomannan antibody on a disposable chip. Biosens. Bioelectron. 38, 421–424 (2012).

Ramirez-Priego, P. et al. Label-free and real-time detection of tuberculosis in human urine samples using a nanophotonic point-of-care platform. ACS Sens 3, 2079–2086 (2018).

Crawford, A. C. et al. Detection of the tuberculosis antigenic marker mannose-capped lipoarabinomannan in pretreated serum by surface-enhanced Raman scattering. Analyst 142, 186–196 (2016).

Mukundan, H. et al. Rapid detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis biomarkers in a sandwich immunoassay format using a waveguide-based optical biosensor. Tuberculosis 92, 407–416 (2012).

World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2023. (World Health Organization, Geneva, 2023).

Chen, P. et al. Sensitive Urine Immunoassay for Visualization of Lipoarabinomannan for Noninvasive Tuberculosis Diagnosis. ACS Nano 17, 6998–7006 (2023).

Wood, A. et al. Ultrasensitive detection of lipoarabinomannan with plasmonic grating biosensors in clinical samples of HIV negative patients with tuberculosis. PLOS ONE 14, e0214161 (2019).

Martens, D. et al. A low-cost integrated biosensing platform based on SiN nanophotonics for biomarker detection in urine. Anal. Methods 10, 3066–3073 (2018).

Saipetch, K. et al. Exploring the fluorescence quenching interaction of amino acids and protein with natural organic matter by a multi-spectroscopic method. Water Supply 21, 3402–3415 (2021).

Shen, C.-H. Chapter 7 - Quantification and analysis of nucleic acids. in Diagnostic Molecular Biology (Second Edition) (ed. Shen, C.-H.) 181–208 (Academic Press, 2023).

Shaukat, S. N., Eugenin, E., Nasir, F., Khanani, R. & Kazmi, S. U. Identification of immune biomarkers in recent active pulmonary tuberculosis. Sci. Rep. 13, 11481 (2023).

Angala, S. K., Li, W., Boot, C. M., Jackson, M. & McNeil, M. R. Secondary extended mannan side chains and attachment of the arabinan in mycobacterial lipoarabinomannan. Commun. Chem. 3, 1–15 (2020).

Fontaniella, B., Millanes, A.-M., Vicente, C. & Legaz, M.-E. Concanavalin A binds to a mannose-containing ligand in the cell wall of some lichen phycobionts. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 42, 773–779 (2004).

Pan, Q. et al. Aptamer against mannose-capped lipoarabinomannan inhibits virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in mice and rhesus monkeys. Mol. Ther. 22, 940–951 (2014).

Corrigan, D. T., Ishida, E., Chatterjee, D., Lowary, T. L. & Achkar, J. M. Monoclonal antibodies to lipoarabinomannan/arabinomannan – characteristics and implications for tuberculosis research and diagnostics. Trends Microbiol. 31, 22–35 (2023).

Song, M., Hang, T.-J., Wang, C., Yang, L. & Wen, A.-D. Precolumn derivatization LC–MS/MS method for the determination and pharmacokinetic study of glucosamine in human plasma and urine. J. Pharm. Anal. 2, 19–28 (2012).

Mehta, I., Zimmern, P. & Reitzer, L. Enzymatic Assay of D-mannose from urine. Bioanalysis 10, 1947–1954 (2018).

Fetherston, C. M., Lai, C. T., Mitoulas, L. R. & Hartmann, P. E. Excretion of lactose in urine as a measure of increased permeability of the lactating breast during inflammation. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 85, 20–25 (2006).

Yao, Y. & Zhang, C. A novel screen-printed microfluidic paper-based electrochemical device for detection of glucose and uric acid in urine. Biomed. Microdevices 18, 92 (2016).

Xiao, Y. et al. Fluorescence and absorbance dual-mode immunoassay for detecting Ochratoxin A. Spectrochim. Acta Part A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 279, 121440 (2022).

Januarie, K. C., Uhuo, O. V., Iwuoha, E. & Feleni, U. Recent advances in the detection of interferon-gamma as a TB biomarker. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 414, 907–921 (2022).

Anes, E., Pires, D., Mandal, M. & Azevedo-Pereira, J. M. ESAT-6 a Major Virulence Factor of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Biomolecules 13, 968 (2023).

Qiu, X. et al. Is interleukin-2 an optimal marker for diagnosing tuberculosis infection? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Med. 52, 376–385 (2020).

Chuah, Y. J. et al. Simple surface engineering of polydimethylsiloxane with polydopamine for stabilized mesenchymal stem cell adhesion and multipotency. Sci. Rep. 5, 18162 (2015).

Kyriacos, D. Chapter 17 - Polycarbonates. in Brydson’s Plastics Materials (Eighth Edition) (ed. Gilbert, M.) 457–485 (Butterworth-Heinemann, 2017).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. 2020R1A5A1018052, No. 2021R1A2C3011254, H.I.J.), and the Commercialization Promotion Agency for R&D Outcomes(COMPA) grant funded by the Korea government(Ministry of Science and ICT) (RS-2024-00432946, H.I.J.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.H. and Q.W. developed lab-in-a-cartridge (LIC) system, analyzed the results, and wrote the paper. D.-U.K. contributed to the experimental design and analysis. J.S., S.P., S.J.P. and J.K. proceeded to review and edit the manuscript. Y.A.K. performed result validation and provided the resources. S.C. and H.-I.J. revised the paper. S.C. and H.-I.J. provided mentorship and supervised the research.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare the following competing financial interests: S.C., S.J.P., and S.P. are employees of The DABOM Inc., and H.I.J. is the founder of the company. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Richard Luxton, Jesus Rodriguez-Manzano and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Heo, W., Wang, Q., Choi, S. et al. Lab-in-a-cartridge for real-time detection of tuberculosis via precise measurement of urinary lipoarabinomannan. Nat Commun 16, 10299 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65217-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65217-w