Abstract

Testosterone insufficiency disrupts spermatogenesis and expedites male aging. Autophagy facilitates testosterone synthesis. However, a molecular reduction mechanism of autophagy-related protein 4 homolog B (ATG4B) has not been established. Herein, we reveal that peroxiredoxin 1 (PRDX1) is clinically associated with male fertility disorders. Adult mutant mice with Leydig cell (LC)-specific deletion of the Prdx1 gene exhibit premature testicular aging and infertility. A series of in vivo and in vitro experiments, in combination with multi-omics analyses, demonstrate that PRDX1 inactivation impairs lipophagy and testosterone synthesis in LCs. Mechanistically, Cys52 and Cys173 in PRDX1 specifically target the redox-site Cys78 in ATG4B to preserve the delipidating activity of Cys74 in ATG4B, thereby promoting autophagic flux. Furthermore, PRDX1 dysfunction exacerbates testicular and systematic aging in aged mice, which can be alleviated by a 2-cysteine mimic, ebselen. Collectively, our findings demonstrate that PRDX1 promotes lipophagy and testosterone synthesis by regulating ATG4B. Our findings also propose the potential application of ebselen in the prevention and treatment of aging-related disorders, including late-onset hypogonadism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Infertility is a multifactorial pathological condition affecting an estimated 70 million people worldwide, with ~15% of couples experiencing fertility issues1,2. Male factor infertility accounts for approximately 50% of these cases, in which decreased sperm number and/or motility are the key contributing factors2,3. Male gametogenesis is a complicated process that occurs in seminiferous tubules and encompasses two consecutive processes, spermatogenesis and spermiogenesis. The former involves spermatogonial differentiation into spermatocytes and two rounds of meiotic division to produce spermatids. The latter involves the maturation of round spermatids into specialized spermatozoa with flagella, which further mature in the epididymides to acquire fertilization capability4,5,6. Sertoli cells provide direct physical and nutritional support for germ cell differentiation7, while Leydig cells (LCs), located in the testicular interstitium, produce over 95% of the testosterone in the human body8. This hormone is essential not only for spermatogenesis and sperm maturation but also for physical development and systematic metabolic homeostasis. In men, the testosterone concentration in the blood begins to decline gradually after the age of 30. Late-onset hypogonadism (LOH) is a clinical and biological syndrome associated with aging, characterized primarily by serum testosterone deficiency9. The main symptoms of LOH include reduced libido, erectile dysfunction, decreased muscle mass and strength, increased adiposity, osteoporosis/osteopenia, depressed mood, and fatigue10. Moreover, LOH is closely related to neurodegeneration, diabetes, and cardiovascular dysfunction11.

Autophagy is a highly conserved eukaryotic cellular recycling process that delivers aged materials to lysosomes for degradation recycling via double-membrane organelles called autophagosomes12. The processing of ubiquitin-like ATG8 proteins (LC3 and GABARAP families in mammals) is critical for autophagosome formation13,14. The cysteine protease ATG4 regulates LC3/GABARAP processing through two key steps. In the lipidation step, newly synthesized pro-LC3/GABARAP is primed (LC3-I/GABARAP-I) for conjugation to phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) to form LC3-II/GABARAP-II for autophagosome biogenesis. In the delipidation step, LC3/GABARAP is deconjugated from PE to facilitate autophagosome maturation and autophagic flux, as well as to maintain the cytoplasmic pool of LC3I and LC3II15,16,17,18,19. Of the four members of ATG4, ATG4B exhibits the highest activity and broadest specificity towards LC3/GABARAP20. Study suggests that ATG4B is regulated by redox mechanisms, such as through the formation of a reversible intramolecular disulfide bond or the reversible oxidative modification of the redox-sensitive site cysteine 7821,22,23. However, the physiological and pathophysiological significance of these redox mechanisms in vivo remains unclear. Furthermore, it is unknown whether a specific molecular reducing machinery counteracts the inhibitory oxidative modification of ATG4 to maintain its function and autophagic flux. Although thioredoxin has been proposed to reduce ATG4 in yeast, evidence of their direct molecular interaction is lacking24. Thus, a precise redox mechanism regulating ATG4 function in mammals has yet to be elucidated.

Initially considered a cell survival mechanism, emerging evidence suggests that autophagy plays a critical role in cellular metabolism and energy homeostasis. For example, during starvation, autophagy recycles unnecessary cellular components into metabolic pathways to support mitochondrial function and maintain energy homeostasis25. The autophagic degradation of lipid droplets (LDs), known as lipophagy, is essential for cellular lipid metabolism26. Defects in lipophagy are strongly associated with metabolic disorders such as obesity, hepatic steatosis, and atherosclerosis27. In the testes, autophagy is highly active in young LCs but very weak in aged LCs28. Autophagy is crucial for cholesterol uptake and cholesterol ester degradation into free cholesterol for testosterone synthesis29. However, the molecular network governing autophagy regulation and testosterone biosynthesis in LCs remains to be established.

Peroxiredoxins (PRDXs) are a ubiquitous family of thiol-dependent, selenium-independent, non-heme peroxidases that regulate peroxide levels within cells30. In mammals, PRDX1 is a member of the subfamily and uses a typical 2-cysteine mechanism30. The two key redox-active cysteines in PRDX1 are Cys52 and Cys173. The two form an intermolecular disulfide bond, enabling PRDX1 to function as a homodimer31. Another important cysteine, Cys83, facilitates decamer formation through homodimer interactions32. Therefore, PRDX1 can exist as a monomer, dimer, or decamer in cells. When PRDX1 reacts with peroxides, Cys52 and Cys173 become oxidated and even hyperoxidated, rendering PRDX1 catalytically inactive. This inactivation can be reversed by sulfiredoxin33. Studies show that human PRDX1 is rapidly inactivated by as little as 100 μM H2O2, limiting its role as a primary peroxide-scavenging enzyme31. Instead, increasing evidence suggests PRDX1 functions as a redox sensor and signaling transducer. For example, PRDX1 binds and protects PTEN from oxidation-induced inactivation to inhibit tumorigenesis34. It also controls neuronal differentiation through thiol-redox-dependent activation of GDE235. Furthermore, PRDX1 modulates the nuclear localization and transcriptional activity of FOXO3 through redox regulation36. Interestingly, PRDX1 is involved in autophagy activation, and its deficiency impairs lipophagy in macrophages, contributing to atherosclerosis-like pathology37. These findings highlight the critical role of PRDX1 in redox signaling and autophagy regulation. However, the precise function and underlying mechanism remain unclear.

In this study, we showed that decreased PRDX1 expression is clinically associated with testicular dysfunction and male infertility. To investigate the role and mechanism of PRDX1 in LCs, we generated conditional knockout (cKO) mice with Prdx1 deletion in LCs and TM3 cells with stable Prdx1 knockdown (KD cells). Our findings show that PRDX1 inactivation, both in vivo and in vitro, impairs lipophagy and testosterone synthesis in LCs. Mechanistically, PRDX1 activates ATG4B in a redox-dependent manner to modulate autophagic flux. PRDX1 dysfunction accelerates aging and LOH-related syndromes in aged mice, which were rescued by ebselen, a 2-cysteine mimic. In summary, our results elucidate a molecular mechanism by which PRDX1 specifically fine-tunes ATG4B activity to monitor autophagy, and suggest the potential application of ebselen for preventing and treating LOH by restoring autophgy in aged LCs.

Results

PRDX1 is involved in spermatogenesis

To identify genes associated with spermatogenic defects, testes biopsies were collected from patients with non-obstructive azoospermia (NOA) and OA for proteomics analyses using isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantification (iTRAQ) analysis (Fig. 1a). The OA group served as the control. The proteins with a fold-change (NOA vs OA) greater than 1.5 or less than 0.67 were considered as differentially expressed proteins (DEPs). The results revealed that PRDX1 was among the top DEPs, showing a significant downregulation (Fig. 1b). To validate this finding, we performed immunohistochemical staining for PRDX1 on a testis biopsy tissue microarray comprising 30 NOA and 25 OA samples (Fig. 1c). Expression intensity ranking, combined with Wilcoxon signed-rank test, confirmed that PRDX1 expression was significantly reduced in the testes of NOA patients (Fig. 1d). Additionally, Venn diagram analysis integrating our proteomic data with three independent single-cell RNA sequencing datasets for human NOA, human LOH, and mouse testis aging showed that PRDX1 expression was reduced across these testicular pathologies (Fig. 1e). These findings suggest that PRDX1 downregulation is implicated in testicular dysfunction.

a Representative H&E images of testicular biopsies of OA and NOA patients. n = 3 independent experiments with similar results. b Proteomic analyses by iTRAQ showing the relative protein level of PRDX1 in the testicular biopsies of OA versus NOA patients. Test-1, −2, −3 indicate the tests with three randomly paired samples. AVG, average; CV, coefficient of variation. c Representative IHC images showing the ranking of PRDX1 expression in testicular biopsies of OA and NOA groups. d PRDX1 expression ranking in a tissue microarray composed of testicular biopsies from NOA (n = 30) and OA (n = 25) patients. The differences in the PRDX1 expression between groups were tested using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. e Venn diagram analysis integrating our proteomic data with three independent single-cell RNA sequencing datasets for human NOA, human LOH and mouse testis aging. Note that downregulation of PRDX1 was consistently involved in these pathologies. f Serum testosterone concentration of NOA (n = 30) and OA (n = 25) patients. g, h Co-immunofluorescence of PRDX1 (red) and DDX4 (green), a germ cell marker, in the testes of OA and NOA patients. Quantification data is presented in (h). n = 5 for each group. i, j Co-immunofluorescence of PRDX1 (red) and 3β-HSD1 (green), a LC marker, in the testes of OA and NOA cases. Quantification data is presented in (j). n = 5 for each group. k BODIPY staining showing lipid deposition in testes of OA and NOA patients. Quantification data for LD number in interstitial area are presented in (l). n = 5 for each group. Values in (f) represent Mean ± SD, others represent Mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Data in (f) (h), (j) and (l) were analyzed by t-test. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bars = 100 μm in (a) and (c), 50 μm in (g), (i) and (k).

Interestingly, serum testosterone levels in NOA patients were significantly decreased compared with those in OA patients (Fig. 1f). Co-immunofluorescence (IF) of PRDX1 with a germ cell marker DDX4 or a Leydig cell (LC) marker, 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3β-HSD1), revealed that PRDX1 signals were predominantly distributed in the interstitial area and co-localized with 3β-HSD1, with mild signals in the tubules co-localizing with DDX4 (Fig. 1g–j). This indicates that PRDX1 plays a role in LC function. Besides, the testes of NOA patients showed decreased levels of PRDX1 and 3β-HSD1, suggesting that PRDX1 is involved in LC functions and its levels are reduced in NOA testes. Additionally, BODIPY staining showed that neutral lipids were accumulated in the interstitial area of NOA testes (Fig. 1k, l). These results suggest that PRDX1 downregulation is associated with testosterone deficiency and lipid accumulation.

Loss of Prdx1 in LCs induces testosterone deficiency and male infertility in mice

To confirm whether PRDX1 expression pattern is conserved in mice, we performed IF staining of PRDX1 on mouse testicular sections to assess the spatiotemporal expression of PRDX1 during postnatal testis development. At postnatal day (PND) 1, PRDX1 was predominantly expressed in the interstitial regions, with weak expression in the seminiferous tubules. As the development of the testis progressed, its level increased. By PND 28, strong IF signals were observed in the interstitial regions, and by PND 56, PRDX1 expression began to decline. In 12-month-old mice, PRDX1 signals were almost undetectable in the testes (Supplementary Fig. 1a). This pattern is in line with that in human and indicates that PRDX1 expression decreases with age after adulthood. WB analyses confirmed that PRDX1 expression gradually declines with age and is undetectable in 20-month-old mice (Supplementary Fig. 1b), which corresponds to ~60 years of age in humans38. Co-IF for PRDX1 and SF1 showed that PRDX1 was also predominantly expressed in LCs in mice (Supplementary Fig. 1c). These data support that PRDX1 is highly involved in LC function and that its decreased expression is associated with testicular aging.

To investigate the role of PRDX1 in LC function and spermatogenesis, we generated cKO mice with Prdx1 deletion specifically in LCs using the Cre-loxP system29 (Sf1-Cre, Prdx1-loxP) (Supplementary Fig. 1d). Mutant mice with each genotype were obtained, and they followed Mendelian inheritance patterns. Male mice positive for Sf1-Cre and homozygous for Prdx1-loxP alleles (Sf1-Cre+, Prdx1loxP/loxP) were designated as cKO mice, while littermates homozygous for Prdx1-loxP and negative for Sf1-Cre (Sf1-Cre-, Prdx1loxP/loxP) served as control (Ctrl) mice (Supplementary Fig. 1e, f).

IF and WB analyses confirmed that PRDX1 expression was cleared in the LCs of cKO mice (Fig. 2a–c). Histomorphological examination showed that all stages of germ cells were present in the testes of cKO and Ctrl mice. However, the cKO testes exhibited a mild decrease in germ cell numbers (Fig. 2d–g), indicating that Prdx1 deficiency does not induce significant changes in testicular architecture. Testis weight in the cKO mice decreased significantly after 4 months old, and the body weight decreased after 7 months (Fig. 2h). Notably, the reproductive capacity of cKO mice began to decline at 3 months and was completely lost by 6 months, ~5 months earlier than in the Ctrl mice (Fig. 2i). This finding suggests that Prdx1 deletion in LCs causes early loss of male fertility. Sperm count in cKO mice was not significantly reduced until 10 months (Fig. 2j), while sperm motility was significantly decreased at 2 months (Fig. 2k). Sperm quality is closely associated with testosterone levels. Testicular testosterone levels in cKO mice were also significantly reduced at 2 months (Fig. 2l). These findings demonstrate that PRDX1 dysfunction in LCs leads to testosterone deficiency, reduced sperm motility, and male infertility, closely mirroring the syndromes observed in patients.

a, b Co-immunofluorescence of PRDX1 (green) and SF1 (red) in testes from 1-month-old Ctrl and cKO mice. Quantification of PRDX1 intensity was showed in (b). c WB analyses of PRDX1 level in testes from 3-month-old Ctrl and cKO mice. d, e Representative H&E images showing testis morphology of 3- and 6-month-old Ctrl and cKO mice. d in box indicates the diameter of tubules and r indicates the radius. Quantification data were showed in (e). f, g Immunofluorescence of DDX4 (green), a germ cell marker in testes from 3- and 6-month-old Ctrl and cKO mice. Quantification of intensity was showed in (g). h Curves for the body (B) and testis (T) weight of Ctrl and cKO mice from 2 to 12 months old. i Curves for the cumulative litter size of Ctrl and cKO mice from 2 to 12 months old. Note that cKO mice became infertile at 6 months old, compared with 11 months old in Ctrl mice. j Sperm count of Ctrl and cKO mice from 2 to 12 months old. k Sperm motility of Ctrl and cKO mice from 2 to 12 months old. Note that the sperm motility of cKO mice at 2 months old equivalent to that of Ctrl mice at 8 months old. Type a, rapid progression; type b, low or sluggish progression; type c, nonprogressive. l Testicular testosterone levels of Ctrl and cKO mice from 2 to 12 months old. Testosterone levels were measured with total testis homogenates and values are presented as ng/mg protein. Five mice from each group were analyzed (n = 5). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. n.s. not significant. All values represent Mean ± SEM. Data in (b) were analyzed by t-test, others by two-way ANOVA and sometimes followed by the Dunnett test for between-group differences. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bars = 50 μm in (a), (d) and (f).

Deletion of Prdx1 induces lipid accumulation and testosterone insufficiency in LCs

We next explored the potential reasons for testosterone deficiency caused by Prdx1 inactivation. The serum level of luteinizing hormone was comparable between Ctrl and cKO mice (Fig. 3a), excluded an impairment in pituitary-gonadal axis. qRT-PCR analyses showed that the mRNA levels of the steroidogenic enzymes involved in testosterone biosynthesis39, including Lhcgr, Star, Hsd3b1, and Hsd17b3, were not significantly changed. By contrast, the mRNA levels of Cyp11a1 and Cyp17a1 were significantly elevated in the cKO testes (Fig. 3b). This indicates that the steroidogenic pathways in the cKO testes were not impaired. Although the levels of total triglyceride and total cholesterol in whole testes were unchanged (Fig. 3c, d), their levels in the cKO LCs were significantly elevated (Fig. 3e, f). By contrast, the level of free cholesterol, a direct substrate for testosterone synthesis, and its proportion in total cholesterol, were significantly decreased in the cKO LCs (Fig. 3g, h). Consequently, testosterone synthesis was notably compromised in the cKO LCs (Fig. 3i). The mRNA levels of Ldlr and Scarb1, which mediate the uptake of low- and high-density lipoproteins into LCs, respectively, were comparable between the Ctrl and cKO groups (Fig. 3j). Therefore, we excluded an impairment in the upstream pathways controlling cholesterol uptake. We also excluded disturbances in LC differentiation, as the expression of markers for fetal and adult LCs39,40 were unaffected following Prdx1 deletion (Fig. 3k). Immunofluorescences for SF1 and 3β-HSD1 confirmed that Prdx1 deficiency did not cause loss of LCs (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Fig. 1g–i). Oil Red O staining revealed that lipid droplets (LDs), rich in triglycerides and cholesterol esters, were prominently deposited in the interstitial region of the cKO testes (Fig. 3l). Both the number and size of LDs were significantly increased (Fig. 3l, m). BODIPY 493/503 staining for neutral lipids confirmed these findings (Fig. 3n, o). Together, these results demonstrate that lipids aberrantly accumulate in the cKO testes, potentially contributing to cholesterol insufficiency.

a ELISA assay of serum luteinizing hormone (LH) levels in 2- and 6-month-old Ctrl and cKO mice. b mRNA levels of the genes participating in testosterone biosynthesis in Ctrl and cKO mice. Total triglyceride (TG, c) and total cholesterol (TC, d) levels in testes. Total testis homogenates were used and values are presented as mg/g protein. Total triglyceride (e), total cholesterol (f), and free cholesterol (FC, g) levels in freshly isolated LCs. Total LC homogenates were used and values are presented as mg/g protein. h Ratio of free to total cholesterol in freshly isolated LCs. i Testosterone levels in freshly isolated LCs. Values are presented as μg/g protein. n = 5 biological replicates. j mRNA levels of Ldlr and Scarb1 in testes. k mRNA levels of adult and fetal LC markers in testes. l, m Oil red O staining showing lipid deposition in testicular interstitial area. Lipid droplets (LDs) with a diameter <0.5 μm (small, S), 0.5–1.0 μm (median, M), >1 μm (large, L) were counted and quantification was showed in (m). n, o BODIPY 493/503 staining showing lipid deposition (green) in testicular interstitial area. Quantification was showed in (o). p–r Co-fluorescence of BODIPY 493/503 (green) and LC3 (red) in interstitial area. Relative intensity within the indicated area outlined in (p) was measured and the values indicate percentages of colocalizing signals (q). A.U., arbitrary units. Pearson’s colocalization coefficients were determined (r). s, t TEM images displaying LDs and LD-autophagic vacuole (AV) contacts in interstitial area. Yellow asterisks indicate LDs, blue triangles indicate AV-associated LDs. Magnification and quantification were showed in (t). Values indicate the percentage of AV-associated LDs. u WB analyses of LC3 and p62 levels in testes. The relative levels of LC3-II/LC3-I and p62/tubulin were presented. Total testis extracts were used. All mice tested were 3 months old unless otherwise specified. Five mice from each group were analyzed (n = 5). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. n.s. not significant. All values represent Mean ± SEM. Data in (c–i), (o) (r) and (t) were analyzed by t-test, others by one-way ANOVA followed by the Dunnett test for between-group differences. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bars = 10 μm in (l), 20 μm in (n), 100 μm in (p), and 1 μm in (s).

Autophagy plays a key role in degrading cholesterol esters into free cholesterol for testosterone synthesis29. To examine lipophagy in the cKO testes, we performed co-staining of BODIPY 493/503 and LC3. In the testis, LC3 signals were predominantly localized in the interstitial region. The co-localization of BODIPY 493/503 and LC3 was significantly decreased in the cKO testes (Fig. 3p–r). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) clearly showed an increased deposition of LDs in the cKO LCs, with few LDs associated with autophagic vacuoles; LDs were neither in contact with nor engulfed by autophagic vacuoles (Fig. 3s, t; Supplementary Fig. 1j). Additionally, the total LC3 level, the ratio of LC3II/ LC3I, and the p62 level were significantly elevated in the cKO testes (Fig. 3u). These results suggest that the loss of Prdx1 interferes with the autophagic process and lipid degradation in LCs, likely contributing to testosterone insufficiency.

Loss of Prdx1 impairs lipid metabolism in the testis

Based on the above observations, we performed lipidomics analysis to investigate lipid metabolism in the cKO testes. Orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) showed a good discrimination between the Ctrl and cKO groups (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Consistent with the observed lipid accumulation, the total lipid content was significantly increased in the cKO testes (Supplementary Fig. 2b). In the cKO testes, 158 lipid molecules were upregulated, and 217 were downregulated (Supplementary Fig. 2c). The altered lipid molecules primarily belonged to the superclass of glycerolipids (GLs), glycerophospholipids (GPs), and sphingolipids (SPs) (Supplementary Fig. 2d). For the lipid species, the percentage of triglycerides in total lipids was significantly elevated, while that of ceramides was reduced in the cKO testes (Supplementary Fig. 2e). Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis showed that the upregulated lipid molecules were mainly associated with “autophagy”, whereas the downregulated lipid molecules were mainly associated with “regulation of lipolysis in adipocytes”, “glycerophospholipid metabolism”, “fat digestion and absorption”, and “cholesterol metabolism”. These findings suggest that both autophagy and lipid metabolism were impaired in the cKO testes (Supplementary Fig. 2f).

To further investigate global metabolism in the testis, we performed full-spectrum metabolomics. OPLS-DA showed a good discrimination between the two groups (Supplementary Fig. 3a). We identified 2184 molecules with a significant elevation and 1071 molecules with a significant reduction (Supplementary Fig. 3b). These differential metabolites primarily belonged to the superclass of “organic acids and derivatives”, “organic oxygen compounds”, and “lipids and lipid-like molecules” (Supplementary Fig. 3c). KEGG pathway analyses indicated that these differential metabolites were primarily associated with “central carbon metabolism in cancer”, “pyrimidine metabolism”, “ABC transporters”, and “biosynthesis of amino acids”. These findings suggest that Prdx1 deficiency alters the metabolic activity in the testes (Supplementary Fig. 3d).

PRDX1 regulates lipophagy in LCs

To precisely characterize the role and mechanism of PRDX1 in regulating lipophagy in LCs, we generated a mouse TM3 Leydig cell line with stable Prdx1-knockdown (KD) using lentivirus harboring shRNA targeting Prdx1. WB analyses confirmed that PRDX1 expression was nearly undetectable in the KD cells (Fig. 4a). Consistent with observations in the cKO testes, the total LC3 level, the ratio of LC3II/LC31, and the p62 level were increased in the KD cells (Fig. 4a). However, the levels of ULK1 and beclin, two upstream regulators of autophagy, remained unchanged, indicating a defect in autophagic flux (Fig. 4a). To further address this, we employed various autophagy inhibitors or activators. Treatment with 3-methyladenine (3-MA), a PtdIns3K inhibitor, reduced total LC3 signals, yet a strong LC3II signal persisted in the KD cells (Fig. 4b, lanes 3, 4). When autophagosome–lysosome fusion was blocked with chloroquine (CQ) or lysosomal degradation was inhibited with pepstatin A (PA) or leupeptin (LP), total LC3 signals increased, but LC3II levels remained elevated in the KD cells (Fig. 4b, lanes 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10). Additionally, a minor increase in LC3II was observed after rapamycin treatment (which inhibits mTORC1 activity, lanes 11 and 12). In all KD groups, p62 accumulation was evident after these treatments, confirming a blockage of autophagic flux. The levels of LC3II and p62 were also increased after treatment with MRT68921 to inhibit ULK1 activity or with Bafilomycin A1 to block autophagosome–lysosome fusion (Supplementary Fig. 4a, b). Interestingly, PRDX1 protein levels decreased after 3-MA treatment, while they increased after CQ, LP, or PA treatment (Fig. 4b), suggesting that PRDX1 is involved in autophagy. The accumulation of LC3II and p62 was also observed in the KD cells under oxidative stress induced by H2O2 or of serum deprivation (Fig. 4c; Supplementary Fig. 4c). These findings suggest that PRDX1 inactivation blocks autophagy, a defect that cannot be eliminated by autophagy activators or lysosomal inhibitors. Moreover, despite its role as an antioxidant, PRDX1 KD did not increase reactive oxygen species levels in TM3 cells (Supplementary Fig. 4d), indicating that PRDX1 deficiency-impaired autophagy does not involve oxidative stress.

a WB analyses of autophagy-related proteins in negative control (NC) and PRDX1 knockdown (KD) TM3 cells. The relative levels of LC3 and p62 were showed. b WB analyses of LC3 and p62 levels in cells after indicated treatments for 8 h. The relative levels of LC3 and p62 were showed. 3-MA (3-methyladenine, 10 mM), CQ (chloroquine, 20 μM), PA (pepstatin A,10 μg/mL), LP (leupeptin, 100 μM), Rapa (rapamycin, 10 nM). c WB analyses of LC3 and p62 levels in cells after treatment with gradient H2O2 for 1 h. The relative levels of LC3 and p62 were showed. d–f Co-immunofluorescence of LC3 (green) and LAMP1 (red), a lysosome marker, in cells with or without H2O2 treatment (100 μM, 1 h). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Relative intensity within the indicated area outlined in (d) was measured and the values indicate percentages of colocalizing signals (e). A.U., arbitrary units. Pearson’s colocalization coefficients were determined (f). n = 5 for each group. g, h LC3-GFP-RFP dual-fluorescence assay showing autophagic flux. Cells were transfected with lentivirus harboring LC3-GFP-RFP. The ratio of RFP+GFP+ (presents autophagysome) to RFP+GFP- (presents autolysosome) was calculated and showed in (h). n = 5 for each group. i, j Proteinase K and Triton X-100 assay to examine the integrity of autophagosome membrane. Quantification of p62 level was showed in (j). n = 5 for each group. k–m Co-fluorescence of BODIPY 493/503 (green) and LC3 (red). Relative intensity within the indicated area outlined in (k) was measured and the values indicate percentages of overlapping signals (l). A.U., arbitrary units. Pearson’s colocalization coefficients were determined (m). n = 5 for each group. n–p Co-fluorescence of BODIPY 493/503 (green) and LysoTracker (red). Relative intensity within the indicated area outlined in (n) was measured and the values indicate percentages of colocalizing signals (o). A.U. arbitrary units. Pearson’s colocalization coefficients were determined (p). n = 5 for each group. q, r Lipoprotein uptake and degradation assay. Dil-HDL was added into media for 2 h and then withdrew for 8 h. Live-cell images were captured at indicated time-points. Average Dil-HDL intensity (red) per cell was measured and the curves were showed in (r). n = 5 for each group. s Time-lapse imaging of contacts between lipoproteins (Dil-HDL, red) and autophagic vacuoles (LC3, green). In NC group, lipoproteins were quickly degraded (white arrowheads), while in KD group, they kept steady (blue arrowheads). See Supplementary Movies 1 and 2. t Time-lapse imaging of contacts between autophagic vacuoles (LC3, green) and lysosome (LysoTracker, red). In NC cells, LC3 puncta frequently contacted with lysosomes and then disappeared (gray arrowheads), with new LC3 puncta approaching lysosomes (cyan arrowheads). While in KD cells, a majority of LC3 puncta did not associated with lysosomes and remained visible (pink arrowheads), and even those having contacts with lysosomes kept visible (yellow arrowheads). See Supplementary Movies 3 and 4. n = 50 cells examined over 5 independent experiments. ***P < 0.001. n.s. not significant. All values represent Mean ± SEM. Data in (h) were analyzed by chi-square test, those in (m) and (p) were analyzed by t-test, and others by two-way ANOVA followed by the Dunnett test for between-group differences. Scale bars = 5 μm in (d), (k) and (n), 100 μm in (g), 10 μm in (q), 1 μm in (s) and (t).

To monitor the status of autophagosome-lysosome fusion, we performed co-IF of LC3 and LAMP1, a lysosomal marker. Under physiological conditions, PRDX1 KD increased LC3 puncta while decreasing their colocalization with LAMP1. Treatment with H2O2 further increased LC3 puncta but disrupted the LC3–LAMP1 association (Fig. 4d–f). To further assess autophagic flux, we used the LC3-GFP-RFP dual fluorescence assay41. In this system, when an autophagosome fuses with a lysosome, the acidic environment quenches GFP signals, resulting in red fluorescence. In KD cells, green signals were significantly preserved (Fig. 4g, h), indicating a failure in autophagosome–lysosomes fusion. Next, we used proteinase K and Triton X-100 assays to assess the maturation of autophagosomes (i.e., closure of the autophagosome membrane)42. Although p62 accumulated in the KD cells, its signal disappeared after proteinase K treatment, and Triton X-100 completely cleared p62 in both groups (Fig. 4i, j). These results suggest that PRDX1 deficiency impairs the closure of autophagosome membranes, thus preventing their fusion with lysosomes. We further examined lipophagy by co-staining BODIPY 493/503 with LC3 or LysoTracker. In the KO cells, both BODIPY 493/503 and LC3 foci were enhanced, but their co-localization was significantly reduced (Fig. 4k–m). Similar results were observed for the co-staining of BODIPY 493/503 and LysoTracker (Fig. 4n–p). These results suggest that PRDX1 inactivation impairs autophagosome maturation and induces lipophagy defects in TM3 cells.

To gather more evidence, we examined the uptake and utilization of high-density lipoprotein (HDL), an important source for cholesterol, as autophagy has been suggested to mediate HDL uptake in LCs29. HDL labeled with 1,1’-dioctadecyl-3,3,3’,3’-tetramethyl-indocarbocyanine perchlorate (Dil-HDL) was added to the culture media and then removed. We observed that Dil-HDL signals in TM3 cells increased with incubation time, peaking at 2 h. There was no significant difference in HDL uptake between the NC and KD cells (Fig. 4q, r), indicating that HDL uptake was normal in KD cells. However, after HDL withdrawal, Dil-HDL signals in NC cells rapidly decreased and disappeared by 8 h. By contrast, Dil-HDL signals remained in KD cells, indicating that HDL could not be degraded (Fig. 4q, r). We further conducted live-cell imaging to trace the lipophagic process of HDL. In NC cells, LC3 puncta gradually moved towards and contacted HDL, which was then incorporated into LC3 puncta and eventually disappeared (NC, white arrowheads, Fig. 4s; Supplementary Movie 1). In KD cells, however, HDL and LC3 puncta showed superficial overlapping, and HDL signals were unchanged (KD, blue arrowheads, Fig. 4s; Supplementary Movie 2). Consistently, GFP-LC3-LysoTracker double-labeling showed that in NC cells, LC3 puncta frequently contacted lysosomes and then disappeared (NC, gray arrowheads, Fig. 4t), with new LC3 puncta approaching lysosomes (NC, cyan arrowheads, Fig. 4t; Supplementary Movie 3). By contrast, in KD cells, most LC3 puncta did not contact lysosomes and remained visible (KD, pink arrowheads, Fig. 4t; Supplementary Movie 4). Although some LC3 puncta showed limited contact with lysosomes, their signals did not disappear (KD, yellow arrowheads, Fig. 4t; Supplementary Movie 4). These results demonstrate that PRDX1 dysfunction disrupts the engulfment of LDs or HDL into autophagosomes, preventing delivery to lysosomes for degradation. Interestingly, PRDX1 inactivation did not induce notable autophagic activity targeting mitochondria or endoplasmic reticulum (Supplementary Fig. 4e–j). In line with these observations, ectopic expression of PRDX1 in KD cells reduced accumulation of LC3 and p62, restored lipophagy, and promoted LD degradation (Supplementary Fig. 4k–p). Lastly, we employed the Keima system to tackle the autophagic flux, which is pH-sensitive and emits red fluorescence when situated within acidic lysosomes43. The inactivation of PRDX1 did not result in a significant elevation of red mito-Keima fluorescence; rather, it induced an increase in red Plin1-Keima fluorescence (Supplementary Fig. 4q–t). These findings imply that PRDX1 primarily regulates lipophagy in TM3 cells.

We finally tested these observations in primary LCs, and found that Prdx1-deficient primary LCs also exhibited accumulation of LC3II and p62, decreased association of LC3 and LAMP1, reduced colocalization of BODIPY with LC3 or lysosome, decreased incorporation of HDL into lysosomes (Supplementary Fig. 5). Taken together, these findings provide solid evidences that PRDX1 plays a critical role in regulating lipophagy in LCs.

Lipidomics and transcriptomics for Prdx1-KD cells and integrated analyses

To investigate the impact of PRDX1 inactivation in LCs and identify the molecular mechanism, we performed integrated lipidomics and transcriptomics analyses on NC and Prdx1-KD TM3 cells. OPLS-DA analysis showed a good discrimination between the two groups (Fig. 5a). Heatmap analysis revealed significant changes in specific lipid molecules in the KD cells compared with the NC cells (Fig. 5b). A volcano plot identified 417 lipid molecules with significant upregulation and 182 with downregulation in the KD cells (Fig. 5c). For superclass, GLs were downregulated, while SPs were upregulated in the KD cells, with GPs showing significant changes (Fig. 5d). These results suggest that PRDX1 deficiency induces profound changes in lipid metabolism in TM3 cells.

a OPLS-DA plot of lipidomics analyses with NC and KD TM3 cells (n = 6). b Heat map displaying the overall changes of lipid molecules in each group. c Volcano plot of lipid molecules with significant upregulation or downregulation. d Volcano plot of lipid superclass referred from altered molecules in (c). e Heat map displaying the overall differences in mRNA levels between NC and KD cells revealed by transcriptomics (n = 3). f Top KEGG pathways shared in lipidomics and transcriptomics. The pathways associated with autophagy and lipid metabolism were highlighted in red.

Additionally, transcriptomic analyses identified 2124 differential transcripts in the KD cells, with 1459 upregulated and 665 downregulated (Fig. 5e; Supplementary Data 1). Importantly, KEGG pathway analyses integrated with lipodomics and transcriptomics revealed that the significantly altered mRNA and lipid molecules were primarily associated with “sphingolipid metabolism”, “autophagy”, “inositol phosphate metabolism”, “phosphatidylinositol signaling pathway”, “regulation of lipolysis in adipocytes”, “glycerolipid metabolism”, “fat digestion and absorption”, and “cholesterol metabolism” (Fig. 5f). These results, both at global and molecular levels, show that PRDX1 plays a critical role in regulating autophagy and lipid metabolism in LCs.

PRDX1 controls autophagy by modulating LC3 delipidation through redox-dependent regulation of ATG4B

To elucidate the mechanism by which PRDX1 regulates autophagy, we performed co-IF analysis. Under physiological conditions, PRDX1 did not associate with LC3. However, after blocking autophagic flux with CQ, LP, or PA, PRDX1 associated with LC3 puncta (Supplementary Fig. 6a–c). To identify the target of PRDX1, we performed co-IP assays to screen the potential binding partners in autophagy pathway, including the ATG8 family (LC3 and GABARAP), four ATG4 isoforms (ATG4A, ATG4B, ATG4C, and ATG4D), and the E1-, E2- and E3-like ATG8 conjugating system (ATG7, ATG3, and ATG5/10/16L, respectively), as well as p62 and PEBP1 (Fig. 6a). Our results showed that PRDX1 did not directly bind to LC3. Instead, it exclusively interacted with ATG4B (Fig. 6a). Treatment with dithiothreitol (DTT) to reduce disulfide bonds abolished this interaction (Fig. 6b), indicating that PRDX1/ATG4B binding is thiol-dependent. PRDX1 KD did not alter the protein levels of these autophagy-related proteins, including ATG4B (Supplementary Fig. 6d). ATG4B is a critical member of the ATG4 family, responsible for processing and delipidating of ATG8 proteins17. To determine whether PRDX1 affects the association between ATG4B and LC3, we examined their co-localization. In NC cells, ATG4B and LC3 showed dispersed localization under physiological conditions. After CQ treatment, they both formed puncta, and their co-localization increased (Fig. 6c–e). By contrast, in PRDX1 KD cells or H2O2-treated NC cells, ATG4B and LC3 showed dispersed localization (Fig. 6c–e), indicating that PRDX1 deficiency mimics the effects of H2O2 to sequester LC3 and ATG4B. To address this, we expressed GFP-LC3 and conducted co-IP assays to assess the effects of PRDX1 knockdown or overexpression, or H2O2 treatment on the association between ATG4B and LC3. The results showed that PRDX1 knockdown decreased the association between ATG4B and LC3, whereas H2O2 treatment abolished it (Fig. 6f). Conversely, PRDX1 overexpression restored this association (Fig. 6f). Consistent with the results shown in Fig. 6a, PRDX1 was not detected in the GFP-LC3 precipitates, confirming that PRDX1 does not directly interact with LC3.

a Co-IP/WB analyses of autophagy-related proteins in PRDX1 precipitates. Prdx1-KD TM3 cells were transfected with an adenovirus carrying FLAG-PRDX1. Co-IP was performed using an anti-FLAG antibody. b Co-IP/WB analyses of PRDX1-ATG4B interaction with or without dithiothreitol (DTT, 1 mM), a disulfide bond reducing agent. Treatments were the same as in (a). c–e Co-immunofluorescence of ATG4B (red) and LC3 (green) in NC and KD cells, or NC cells treated with CQ (20 μM, 8 h) or H2O2 (100 μM, 1 h). Relative intensity within the indicated area outlined in (c) was measured and the values indicate percentages of colocalizing signals (d). A.U., arbitrary units. Pearson’s colocalization coefficients were determined (e). n = 5 for each group. f Co-IP/WB analyses of ATG4B-LC3 interaction after PRDX1 knockdown or overexpression. NC and KD TM3 cells were transfected with GFP-LC3, and with or without FLAG-PRDX1 overexpression, finally treated with H2O2. Levels of PRDX1 and ATG4B in the GFP precipitates were detected by WB and quantified. g Roles of Cys52 and Cys173 in PRDX1 in association with ATG4B. HEK293 cells were transfected with plasmids of FLAG empty or FLAG-tagged WT PRDX1, or PRDX1 with single-point mutant C52A, C173A or C83A, or double-point mutant C52A/C173A. ATG4B level in the FLAG precipitates was detected by WB and quantified. h Effect of reconstitution of WT PRDX1 or mutants on the autophagic activity in KD cells. PRDX1-KD HEK293 cells were transfected with plasmids of FLAG-tagged WT PRDX1, or PRDX1 with C52A, C173A, C52A/C173A, or C83A mutation. Levels of LC3-II/I and p62 were detected by WB and quantified. i Roles of Cys74 and Cys78 in ATG4B in association with PRDX1 and LC3. HEK293 cells were transfected with plasmids of GFP tagged WT ATG4B, or ATG4B with Cys74S or Cys78S mutation, followed by treatment with or without H2O2. Levels of PRDX1 and LC3 were detected by WB and quantified. j GST pulldown assays of the molecular interaction between PRDX1 and ATG4B. 20 μg GST tag or GST-tagged PRDX1 proteins and 20 μg His-tagged ATG4B proteins were mixed, and pull downed by GSH magarose beads. k, l Measurement of the delipidation activity of ATG4B. The amount of LC3-I and LC3-II were quantified by gel densitometry, and the ratio of LC3I/LC3II was calculated as the readout for ATG4B delipidation activity. The quantification data were showed in (l). n = 5 for each group. m–o Co-immunofluorescence of ATG4B (GFP, green) and LC3 (red). HEK293 cells were transfected with plasmids of GFP-tagged WT ATG4B, or ATG4B with Cys74S or Cys78S mutation, followed by treatment with H2O2, with or without PRDX1 overexpression. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). GFP/LC3 colocalization was analyzed (n). Quantification of LC3 puncta was showed in (o). n = 50 cells examined over 5 independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. n.s. not significant. All values represent Mean ± SEM. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by the Dunnett test for between-group differences. Scale bars = 5 μm in (c) and (m).

To elucidate how PRDX1 interacts with ATG4B, we investigated its structural properties, focusing on its dimerization via intermolecular disulfide bonds. Studies suggest that PRDX1 forms homodimers via intermolecular disulfide bonds between Cys52 and Cys173 to exert its biological functions33,36. We first examined the monomeric and dimeric forms of PRDX1 in TM3 cells under DTT-free conditions, and found that PRDX1 primarily exists as a dimer under physiological conditions (Supplementary Fig. 6e). As the H2O2 concentration increased, the dimer gradually disappeared while the monomer increased (Supplementary Fig. 6e); Addition of DTT cleared all dimeric bands and only monomeric bands were remained, indicating that PRDX1 primarily acts as a dimer in LCs, which are highly sensitive to H2O2. Cys52 and Cys173 are critical for PRDX1 homodimer formation, while Cys83 is essential for decamer formation32. We then mutated each cysteine residue to alanine to investigate their roles in ATG4B binding. When expressed in cells, both the C52A and C173A single mutants, as well as the double mutant, could not form homodimers, whereas the C83A mutant could form under DTT-free conditions (Supplementary Fig. 6f). Addition of DTT cleared the bands for dimer, validating the dependence on disulfide bond. No bands corresponding to decamer was observed (Supplementary Fig. 6f). Consistently, the C52A or C173A mutation significantly reduced PRDX1–ATG4B binding, while the double mutation abolished it completely. In contrast, the C83A mutation had no impact on this interaction (Fig. 6g). Moreover, PRDX1WT or PRDX1C83A overexpression, but not PRDX1C52A or PRDX1C173A overexpression, efficiently prevented the accumulation LC3 and p62 in Prdx1-KD cells (Fig. 6h). These results demonstrate that PRDX1 functions as dimmer in LCs, with Cys52 and Cys173 being essential for its binding to ATG4B and regulation of autophagy.

The next question was which cysteine residue in ATG4B is targeted by PRDX1. In ATG4B, Cys74 is the catalytic active site16,44, while Cys78 is potentially the redox-sensitive site22. To investigate this, we expressed GFP-tagged ATG4B point mutants and performed co-IP assays. Interestingly, the C78S mutation abolished the ATG4B–PRDX1 association, while enhancing the ATG4B–LC3 association (Fig. 6i, IP), but less LC3II were delipidated (Fig. 6i, input). By contrast, the C74S mutation eliminated ATG4B–LC3 binding but enhanced ATG4B–PRDX1 binding (Fig. 6i). These interactions were abolished upon H2O2 treatment, indicating that the ATG4B–PRDX1 interaction is redox-sensitive. Furthermore, GST pulldown assays confirmed a direct interaction between PRDX1 and ATG4B (Fig. 6j). This interaction vanished when Cys52A/Cys173A mutations occurred in PRDX1 or the Cys78S mutation occurred in ATG4B (Fig. 6j). Consistent with the observation in Fig. 6i, the Cys74S mutation increased the PRDX1–ATG4B association (Fig. 6j). These findings validate that the interaction between PRDX1 and ATG4B depends on Cys52 and Cys173 in PRDX1 and Cys78 in ATG4B.

ATG4B can delipidate LC3II to LC3I17,45, a process essential for autophagosome maturation and lysosomal fusion by maintaining the proper ratio of LC3II to LC3I on the autophagosome membrane46,47. Based on the findings that PRDX1 knockdown led to LC3II and p62 accumulation, a phenomenon that was reversed by PRDX1 overexpression, we speculated that PRDX1 regulates the delipidating activity of ATG4B in a redox-dependent manner. To test this hypothesis, we constructed an in vitro delipidation system. TM3 cells were treated with CQ to induce LC3II accumulation and the LC3II-enriched membrane fractions were collected. Purified protein of WT or redox site-mutated (C78S) ATG4B was added, and the ratio of LC3I to LC3II was calculated as the final readout for ATG4B delipidating activity (Supplementary Fig. 7a). The results showed that LC3II was significantly enriched after CQ treatment (Fig. 6k, l, lanes 1 and 2). ATG4BWT efficiently delipidated LC3II to LC3I, but this activity was largely compromised by H2O2 (Fig. 6k, l, lanes 3 and 4). The addition of PRDX1 protein significantly antagonized the inhibitory effect of H2O2 and restored ATG4B delipidating activity (Fig. 6k, l, lane 5). Notably, ebselen, a 2-cysteine mimic37, not only completely counteracted the inhibitory effect of H2O2, but also further enhanced the ATG4B delipidating activity, with minimal LC3II signal detected (Fig. 6k, l, lane 6). However, the ATG4BC78S mutant showed no detectable delipidating activity and remained insensitive to all redox treatments, including inhibitory H2O2 and activating PRDX1 or ebselen (Fig. 6k, l, lanes 7–10). In line with these observations, co-IF analysis showed that GFP-ATG4BWT exhibited dispersed localization with LC3 under physiological conditions (Fig. 6m–o; Supplementary Fig. 7b). After H2O2 treatment, LC3 puncta increased and no longer associated with ATG4BWT, a phenotype reversed by ectopic PRDX1 (Fig. 6m–o; Supplementary Fig. 7b). ATG4BC78S increased LC3 puncta, and neither associated with LC3 nor responded to H2O2 or ectopic PRDX1 (Fig. 6m–o; Supplementary Fig. 7b). By contrast, ATG4BC74S significantly decreased LC3 puncta, and they sequestered with each other. In addition, ATG4BC74S was resistant to all treatments (Fig. 6m–o; Supplementary Fig. 7b). Finally, we investigated how ebselen protects the ATG4B activity from inhibition by H2O2. Treatment with H2O2 abolished the PRDX1/ATG4B interaction, which was significantly restored by ebselen (Supplementary Fig. 7c). Furthermore, ebselen treatment significantly prevented the H2O2-induced disassociation of ATB4B/LC3 (Supplementary Fig. 7d–f). Subsequently, an in vitro investigation was conducted to examine whether ebselen influences the cleavage activity of ATG4B on LC3-GST. Ebselen alone led to a reduction in the cleavage activity of ATG4B (Supplementary Fig. 7g–i), which is consistent with the prior discovery that ebselen covalently binds to ATG4B and inhibits its cleavage function in vitro48. Nevertheless, under H₂O₂ treatment, ebselen effectively restored the cleavage activity of ATG4B (Supplementary Fig. 7g–i). Furthermore, previous research have also demonstrated that ebselen alleviated the CQ-induced accumulation of LC3II48, which is consistent with our discovery that ebselen enhanced the delipidation function of ATG4B under CQ treatment (Fig. 6k). These results corroborate the hypothesis that the activity of ATG4B is strictly regulated by redox conditions. Furthermore, the findings suggest that ebselen preserves autophagic flux during H₂O₂ exposure by promoting the interaction between PRDX1 and ATG4B, along with the activity of ATG4B towards LC3.

In summary, PRDX1 regulates ATG4B delipidating activity by targeting Cys78 in a redox-dependent manner. H2O2 abrogates the PRDX1/ATG4B association, thus impairing the delipidating activity of ATG4B. LC3II was inappropriately retained in the autophagosome membrane, hampering autophagosome maturation and fusion to the lysosome. PRDX1 dysfunction mimics the inhibitory effects and mechanism of H2O2, resulting in compromised ATG4B activity and autophagic flux. Overexpression of PRDX1 or treatment with ebselen can compensate for the effects of PRDX1 inactivation and H₂O₂ stress.

PRDX1 inactivation accelerates testis aging and LOH syndromes, which are efficiently rescued by ebselen

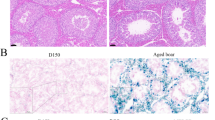

Autophagic activity is high in young LCs but very low in old ones28. As previously observed, PRDX1 expression was almost undetectable in testes of mice after 12 months of age. Given that PRDX1 regulates lipophagy in LCs and that adult cKO mice demonstrated severe testosterone deficiency, we reasoned that decreased PRDX1 expression leads to reduced autophagic activity and testosterone levels in aged testis. Therefore, we raised the following questions: 1) Does the loss of Prdx1 in LCs exacerbate testis aging and LOH? 2) Can PRDX1 overexpression or ebselen restore lipophagy and testosterone levels, thereby delaying testis aging? 3) Can ebselen attenuate LOH-related syndromes? To answer these questions, we used Ctrl and cKO mice at the advanced age of 20 months, which corresponds to humans ~60 years old38. A subset of these mice received ebselen treatment for 1 month, starting at 19 months of age. We also generated genetically engineered mice with conditional overexpression of PRDX1 in LCs using the Cre-loxP system (Supplementary Fig. 8). Compared with aged Ctrl mice, aged cKO mice showed lower body and testis weights (Supplementary Data 2). The testes of aged cKO mice were markedly more degenerated, characterized by severe tubular atrophy, thinner epithelial layers, fewer remaining germ cells, and increased germ cell apoptosis (Fig. 7a, b; Supplementary Fig. 9a–d). Ebselen treatment significantly improved testis morphology, preserved more germ cells, and reduced germ cell apoptosis (Fig. 7a, b; Supplementary Fig. 9a–d). Consistently, ebselen treatment also increased sperm count in aged cKO mice, and both ebselen treatment and PRDX1 overexpression greatly enhanced sperm motility (Fig. 7c, d). Promisingly, both ebselen treatment and PRDX1 overexpression increased testicular and serum testosterone levels in aged Ctrl and cKO mice (Fig. 7e, f). Compared with young mice (4 months old), aged mice (20 months old) showed reduced LC3 levels (Fig. 7g). Both ebselen treatment and PRDX1 overexpression markedly elevated LC3 levels (Fig. 7g), thus enhancing lipophagy (Fig. 7h–j; Supplementary Fig. 8e, f). Consistent with these findings, TEM analyses confirmed increased LD accumulation in aged cKO testes, with minimal autophagic vesicle-associated LDs (Fig. 7k, l). Both ebselen treatment and PRDX1 overexpression significantly increased autophagosome-LD contact (Fig. 7k, l), thus promoting lipophagy and elevating testosterone levels. Furthermore, in vitro ebselen treatment also promoted lipophagy in both young and aged primary LCs (Supplementary Fig. 9g–j).

a, b Representative H&E images showing testis morphology of aged Ctrl and cKO mice, Ctrl and cKO mice with ebselen treatment, and cOE mice (conditional overexpression of PRDX1 in LCs). d in box indicates the diameter and r indicates the radius of tubules. Quantification data were showed in (b). Sperm count (c) and motility (d) of aged mice. e, f Testicular and serum testosterone levels of aged mice. g WB analyses of LC3 levels in testes of adult (4 months old) and aged mice (20 months old). The relative level of total LC3 to tubulin was showed. h–j Co-fluorescence of BODIPY 493/503 (green) and LC3 (red) in testes. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Relative intensity within the indicated area outlined in (h) was measured and the values indicate percentages of overlapping signals (i). A.U., arbitrary units. Pearson’s colocalization coefficients were determined (j). k, l TEM images displaying LDs and LD-autophagic vacuole (AV) contacts in the interstitial area of testes. Yellow asterisks (*) indicate LDs, blue triangles indicate AV-associated LDs. Quantification was showed in (l). m–p Memory, behavior and maximal exercise capacity in aged mice, revealed by Y-maze test (m), open field trail (n), and run-to-exhaustion test (o). Representative track images for the open field test were showed in (p). Five mice from each group were analyzed (n = 5). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. n.s. not significant. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by the Dunnett test for between-group differences. Scale bars = 20 μm in (a), 50 μm in (h), 1 μm in (k).

In elderly humans, testosterone insufficiency is closely implicated in LOH-related syndromes, including but not limited to decreased memory, behavior and motor ability, osteoporosis, obesity and cardiovascular dysfunction9,11. We found that ebselen treatment effectively improved the parameters for memory, behavior, and maximal exercise capacity in both aged Ctrl and cKO mice, as revealed by the number of alternation behaviors (measured by Y-maze test), the total distance and exploratory behavior (measured by open field trail), and the time to exhaustion (measured by run-to-exhaustion test) (Fig. 7m–p). Ebselen treatment also increased the ratio of bone volume to tissue volume in aged cKO mice (Supplementary Fig. 10a, b; Supplementary Data 2). The liver is central to systematic metabolism. In aged cKO mice, lipids were accumulated in the liver, and this phenotype was alleviated after ebsenlen treatment (Supplementary Fig. 10c, d). Notably, we observed elevated levels of serum lactic dehydrogenase, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, and total bilirubin, all of which were rescued by ebselen (Supplementary Fig. 10e–h; Supplementary Data 2), suggesting that ebselen treatment improves liver function. Moreover, ebselen treatment normalized serum levels of triglyceride, total cholesterol, and glucose (Supplementary Fig. 10i–k; Supplementary Data 2), suggesting that ebselen may improve lipid and glucose metabolism. Ebselen treatment also attenuated cell senescence in the testis, brain and liver, as revealed by γ-H2AX immunofluorescence and β-galactosidase staining (Supplementary Fig. 11). To validate the effects of ebselen, we used an aging mouse model induced by β-galactoside administration and treated them with ebselen. We found that ebselen treatment also restored sperm motility and testosterone levels in β-galactoside-subjected mice (Supplementary Fig. 12a–f), likely by enhancing testicular lipophagy (Supplementary Fig. 12g–n). Parameters for behavior and motor ability (Supplementary Fig. 12o–r), cell senescence in the testis, brain and liver in this model were also attenuated (Supplementary Fig. 12s–z). These findings cumulatively demonstrate that ebselen effectively restores testosterone levels and alleviates LOH-related syndromes.

We noted adrenal gland enlargement and increased adrenal weight in aged cKO mice (Supplementary Fig. 12a; Supplementary Data 2). SF1-positive cells were also present in the adrenal gland. However, we did not consider Cre-mediated Prdx1 deletion in the adrenal gland49 (Supplementary Fig. 13a). Adrenal epinephrine levels were normal while adrenal testosterone levels were increased (Supplementary Fig. 13b, c). Therefore, it is possible that adrenal expansion may be a feedback response to serum testosterone insufficiency. We also excluded Cre-mediated Prdx1 deletion in SF1-positive neurons in hippocampus area49, which could explain memory and behavior changes in cKO mice, as PRDX1 was not expressed in these neurons (Supplementary Fig. 13d, e). Given that the luteinizing hormone level was normal (Fig. 3a), we could exclude a possible impairment in hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis. Thus, we conclude that all these phenotypes are attributed to loss of PRDX1 function in LCs.

Discussion

In this study, we first revealed that reduced PRDX1 expression is associated with clinical NOA. Based on three independent single-cell RNA sequencing datasets for human NOA, human LOH, and mouse testis aging, we further suggest that PRDX1 dysfunction is implicated in male fertility disorders. The cKO mice with LC-specific deletion of Prdx1 gene demonstrated severe testosterone deficiency, with testosterone levels in 3-month-old cKO mice comparable to those in 9-month-old Ctrl mice (Fig. 2l). The sperm motility was also largely compromised, with levels in 2-month-old cKO mice comparable to those in 8-month-old Ctrl mice (Fig. 2k). In addition, the male reproductive lifespan was significantly shortened, terminating at 6 months old in cKO mice compared with 11 months old in Ctrl mice (Fig. 2i). These findings suggest that loss of Prdx1 in LCs causes premature testicular aging, and highlight the important role of PRDX1 in LCs and testicular functions and male fertility.

It has been reported that autophagy activity is high in young LCs but declines with aging28. Autophagy is required for testosterone synthesis in LCs in human, mice and goat29,50. Multiple environmental exposures have been demonstrated to elicit dysfunction in LCs through the impairment of autophagy51,52,53. Nevertheless, this conclusion was derived primarily from in vitro observations. To further elucidate these findings, we introduced Prdx1-cKO mice, primary LCs derived from cKO animals, and Prdx1-KD TM3 cells. We systematically analyzed autophagic activity and LD deposition after PRDX1 inactivation. Through a series of rigorously controlled and complementary experimental approaches, we have demonstrated that autophagic flux, particularly the fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes, is significantly impaired following PRDX1 inactivation. Crucially, this finding was consistently validated through multiple independent methodologies, including dual-fluorescence labeling with BODIPY 493/503 and LC3 or LysoTracker, Dil-HDL uptake and degradation assays, as well as live-cell imaging of HDL autophagic delivery to lysosomes, all of which collectively establish that PRDX1 inactivation disrupts lipophagic processes in LCs. Comprehensive lipidomic profiling of whole testicular tissue, coupled with integrated transcriptomic and lipidomic analyses of LCs, revealed that PRDX1 dysfunction induces substantial alterations in autophagic pathways, along with profound perturbations in lipid and cholesterol metabolism. Previous research has indicated that autophagy facilitates testosterone biosynthesis through upregulation of SR-BI, a key regulator of cholesterol uptake29. Our current findings not only corroborate but substantially extend these observations by identifying PRDX1 as a critical upstream modulator that orchestrates lipophagy to regulate cholesterol homeostasis and testosterone production in LCs.

Intriguingly, our findings reveal that PRDX1 functions beyond its conventional role as an antioxidant. Specifically, it exhibits redox-dependent binding to ATG4B and modulates its activity toward LC3. Prdx1 knockdown mimicked the effect of H2O2 treatment, as they both disrupted ATG4B/LC3 interactions, which were restored by ectopic PRDX1 expression. In cells, PRDX1 can exist as monomer, dimer, or decamer32,33. Both Cys52 and Cys173 are required for dimer formation of PRDX1, and they form redox-dependent intermolecular disulfide bonds through which PRDX1 regulates the activity of target proteins32,33. In alignment with these reports, we demonstrated that both Cys53 and Cys172 are indispensable for PRDX1 binding to ATG4B, whereas Cys83, which participates in PRDX1 decamer assembly, is dispensable for this interaction. Correspondingly, a strong signal corresponding to the PRDX1 dimer, but not the decamer, was observed (Supplementary Fig. 6f). The PRDX1 decamer may either be present below the detection threshold or exhibit pronounced sensitivity to experimental parameters. Furthermore, mutations at Cys52 or Cys173, but not at Cys83, completely abrogated dimer formation. These results collectively indicate that in LCs, PRDX1 operates predominantly in its dimeric conformation, with Cys52 and Cys173 mediating both dimer stabilization and ATG4B binding. We have recently reported that a marine-derived piericidin glycoside S14, targets PRDX1 by binding to Cys83 to strengthen its decamer formation, therefore augments its peroxidase activity to alleviate acute kidney injury54. Our present findings complemented this report and suggested new mechanism underlying the action of PRDX1.

Another finding is that PRDX1 targets the Cys78 site to regulate ATG4B function. Cys78 has been previously identified as a redox-sensitive site that regulates Cys74 enzymatic activity16,22. We found that the ATG4BC78S mutant could not bind to PRDX1 but recruited more LC3, whereas the ATG4BC74S mutant could not target LC3 but bound more PRDX1. Therefore, Cys78 is the specific binding site for PRDX1. We also observed that, although ATG4BC78S recruited more LC3 (especially LC3II), higher LC3II and lower LC3I signals were detected (Fig. 6l, input), indicating that C78S mutation impairs ATG4B delipidating activity. Furthermore, H2O2 treatment abolished PRDX1/ATG4B binding, while inducing a significant accumulation of LC3II (LC3I did not change), suggesting that H2O2 treatment dissociates PRDX1 from ATG4B, thus inhibiting LC3II delipidation. Uncontrolled oxidative stress impairs autophagy in LCs53,55. Our findings advance the current understanding by demonstrating that PRDX1 serves as a sensitive redox sensor that regulates ATG4B delipidation activity. PRDX1 appears to be the primary target of oxidative damage induced by environmental toxicants and aging processes. ATG4B has been reported to play a primary role in processing pro-LC3/GABARAP20. We preclude that the processing activity of ATG4B is impaired after PRDX1 knockdown, as a higher LC3-I signal was observed. ATG4B is redundantly expressed in both primary LCs and TM3 cells compared with other ATG4 isoforms (Supplementary Fig. 14a, b). Although fully reconstituted delipidation assays showed that ATG4B has weaker delipidation activity than other ATG4 paralogs19, our results suggest that ATG4B and its delipidating function are more important in LCs and are specifically regulated by PRDX1. Therefore, we propose a mechanism whereby PRDX1 specifically preserves the activity of ATG4B, thereby safeguarding the functions of LCs. This proposal aligns with the robust expression of both PRDX1 and ATG4B observed in young LCs, and the undetectable levels of PRDX1 in aged LCs. Although similar results were obtained in HEK293 cells, further confirmation is required to ascertain whether this mechanism is a universal phenomenon present in other organs or cell types.

The solved three-dimensional structure of human Atg4B shows that Cys74 and Cys78 are situated at the beginning of an α-helix, both facing the same plane of the helix17,56,57. Due to the close proximity between the two cysteines, modifications on Cys78 could indeed affect the activity of Cys74. It was previously reported that oxidative stress causes Cys78 to form a reversible sulfenic acid bond that shields Cys74, or a disulfide bond between Cys78 and other cysteine sites, similarly shielding Cys7422. However, it has been proposed that Cys78 does not form disulfide bonds21. We favor the interpretation that oxidation of Cys78 alters the conformation around Cys74, hampering its accessibility to LC3 and subsequent delipidating activity, which can be prevent by PRDX1. In support of this, in vitro delipidating assay corroborated that H2O2 suppresses ATG4B delipidating activity towards LC3II, which can be efficiently rescued by PRDX1 and ebselen, and Cys78 is their target. Taken all our findings together, we propose a model that ATG4B primarily functions as a “scissor” to delipidate LC3II to maintain the autophagic process (Fig. 8). PRDX1, via Cys52 and Cys173, functions as a molecular safeguard, binding to the redox site Cys78 of ATG4B through thiol groups. This interaction maintains the molecular configuration surrounding the enzymatic site Cys74 and preserves its delipidating activity, akin to keeping the “scissor” in an open state. This process ensures the adequate delipidation of LC3II on autophagic vacuoles, thereby facilitating autophagosome maturation and augmenting autophagic flux. In cases where PRDX1 is inactivated, either due to gene mutation or exposure to oxidative stress, the PRDX1/ATG4B complex dissociates, leading to the oxidation of Cys78 and the subsequent impairment of the delipidating activity of Cys74 (the “scissor” is closed). Consequently, this blockage disrupts both lipophagy and testosterone synthesis. This dysfunction can be effectively rescued by PRDX1 overexpression and ebselen. While studies have only focused on the oxidative regulation of ATG4B21,22,23, our results extend this knowledge by identifying a molecular reducing machinery that specifically monitors ATG4B functions to maintain autophagic flux.

A ATG4B serves as a “scissor” enzyme responsible for the delipidation of LC3II. Dimeric PRDX1 functions as a molecular shield by specifically targeting Cys78 of ATG4B via its Cys52 and Cys173 residues, thereby safeguarding the enzymatic activity of Cys74. This ensures the appropriate delipidation of LC3II on autophagic vacuoles and maintains the equilibrium between LC3II and LC3I, thus facilitating autophagosome maturation and the lipophagic process. Lipid metabolism proceeds seamlessly, ultimately leading to the production of testosterone, which is crucial for spermatogenesis and systemic metabolism. B When PRDX1 is inactivated or when oxidative stress disrupts the PRDX1-ATG4B interaction, Cys78 becomes oxidized, impairing the delipidating activity of Cys74. Consequently, autophagosome maturation is compromised, and lipophagy and lipid metabolism are disrupted, resulting in testosterone deficiency. This deficiency ultimately leads to male infertility and accelerates the processes of LOH and aging. Notably, all these disorders can be effectively mitigated by the administration of ebselen. Created in BioRender. Keke, M. (2025) https://BioRender.com/hb6bsv1.

Another important finding of our study is that ebselen restores testosterone levels and alleviates the LOH-related syndromes in aged mice, manifested as improved memory, enhanced behavior and exercise ability, and decreased risk of cardiovascular dysfunction. These findings offer in vivo evidence that ebselen augments testosterone synthesis58. Testosterone deficiency is a hallmark of LOH9. Our results suggest that PRDX1 inactivation causes early-onset hypogonadism in young mice, with serum testosterone levels in 10-month-old cKO mice equivalent to those in 20-month-old Ctrl mice (Supplementary Fig. 14c), which further exacerbates testicular aging and LOH-related syndromes in aged mice (Fig. 7, Supplementary Figs. 9–11). Although testosterone replacement therapy can increase serum testosterone levels, it increases the risk of androgen-dependent cancers such as prostate cancer59. No adverse effects of ebselen were observed during our study. Furthermore, our results showed that ebselen also improved systematic metabolism and attenuated cell senescence in the testis, brain, and liver in aged cKO mice, in accordance with its substantial capacity to safeguard cellular components against oxidative stress and free radical-induced damage60. Previous research has demonstrated that ebselen inhibits ATG4B, thereby suppressing colorectal cancer in mice48. Conversely, another study has reported that ebselen ameliorates renal ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats by enhancing autophagy61. Our findings distinctly indicate that ebselen enhances the activity of ATG4B on LC3 under H2O2 treatment, potentially through targeting the redox site Cys78. This aligns with ebselen’s mechanism of action via thiol groups60. The observed disparity implies that the utilization of ebselen differs across diverse pathological contexts. Taken together, our findings provide a rationale for the application of ebselen as an efficient and safe therapeutic to prevent or treat testosterone deficiency and LOH, as well as aging-related diseases.

Our study also has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, while the Cys78 mutation in ATG4B abolished its interaction with PRDX1, this finding does not exclude the possibility that other cysteine residues may also bind to PRDX1, as previous studies have demonstrated that cysteines other than Cys78 can form intramolecular disulfide bonds21. Second, although ebselen is known to function through its thiol-reactive properties, we did not provide direct mass spectrometry evidence identifying the specific cysteine residue(s) in ATG4B targeted by ebselen, unlike previous investigations48. Though our data showed that Cys78 mutation prevented ebselen-mediated activation of ATG4B, further biochemical characterization is warranted. Third, while 1-month ebselen treatment significantly improved sperm concentration and testicular testosterone levels in aged cKO mice, this intervention showed no significant effect in aged control mice. Future studies should investigate whether initiating treatment earlier (e.g., at 17 months of age) and extending the duration (e.g., for 3 months) might yield more pronounced therapeutic benefits.

Methods

Testicular biopsy collection, proteomics analyses and testicular tissue microarray

Collection of testicular biopsy samples from clinical male patients with non-obstructive azoospermia (NOA) and OA were described in detail in our previous study62,63. Three testis biopsy samples from each group were subjected to isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantification (iTRAQ) analysis (conducted by Fitgene Biotech Company, Guangzhou, China), for the screening of differentially expressed proteins. The frozen testes were grinded by liquid nitrogen and then lysed in 500 μl of SDS lysis buffer (Add 1× PMSF before use) containing 7 M Urea, 2 M Thiourea, 20 mM Tris base and 0.2% SDS. Then the samples were sonicated and centrifuged to collect the supernatant. Protein concentration was estimated by the Bradford method. Then, proteins were digested with trypsin (Promega, USA) at 37 °C at a ratio of 1:50 (enzyme-to-substrate) overnight. Each sample was labeled separately with two of the eight available tags (OA: 114 and 116 tags; NOA: 117 and 119 tags) (Applied Biosystems, Sciex). All labeled peptides were pooled together. The Ultimate 3000 HPLC system (Dionex, USA) equipped with a 2.00-mm-inner diameter *100-mm-long Gemini-NX 3 u C18110Acolumns (Phenomenex, USA) was used for High-pH fractionation. The iTRAQ-tagged peptides fractionation was performed using a linear binary gradient from 15 to 50% B (20 mM HCOONH 4, 2 M NaOH, 80% ACN) (pH 10) at 0.2 ml/min for more than 45 min. The fraction was resuspended in loading buffer (0.1% FA,2% ACN) and separated with an Ultimate 3000 nano-LC system equipped with a C18 reverse phase column (100-μm inner diameter, 10-cm long, 3-μm resin from MichromBioresources, Auburn, CA). Then, the LC eluent was subject to Q Exactive (Thermo Fisher) in an information dependent acquisition mode. MS spectra were acquired across the mass range of 400–1250 m/z in high resolution mode (>30,000) using 250 ms accumulation time per spectrum. Tandem mass spectra were recorded in high sensitivity mode (resolution >15,000) with rolling collision energy on and iTRAQ reagent collision energy adjustment on62,63.

Tissue microarray processing, and immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining and expression ranking were performed as described previously, except an anti-PRDX1 antibody was used62. Biopsy samples were also processed to frozen section for immuno-staining. The Ethics Committee of the Third Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University approved the experiments involving human subjects (2017-055). The relevant research has obtained informed consent from all participating patients. All ethical regulations relevant to human research participants were followed.

Animals, husbandry and genotyping

The Nr5a1/Sf1-Cre mice was purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Jax number: 012462). The Prdx1-loxP mice (strain name C57BL/6N-Prdx1tm1c(EUCOMM)Wtsi/Cmsu) were obtained from the Cambridge-Suda Genome Resource Center (Suzhou, Jiangsu, China). To generate conditional knockout (cKO) mice with specific Prdx1 deletion in LCs29, Sf1-Cre+ mice were mated with homozygous Prdx1loxP/loxP mice to generate the males with homozygous Prdx1-loxP and positive Sf1-Cre (Sf1-Cre+, Prdx1loxP/loxP). These males were designated as cKO mice in this study, and the males from the same litter with homozygous Prdx1-loxP and negative Sf1-Cre (Sf1-Cre-, Prdx1loxP/loxP) were used as the control mice. A schematic depicting the detailed methodology for the generation of cKO mice is presented in Supplementary Fig. 1d.

To generate conditional PRDX1 overexpression (cOE) mice, a genetically engineered mouse strain C57BL/6J-Gt(ROSA)26Sor was constructed by the Shanghai Southern Model Biology Technology Development Co., Ltd. The CAG-loxP-stop-loxP cassette and the Prdx1-HA-IRES-EGFP-Wpre-polyA cassette were inserted into the Rosa26 gene foci, by using the CRISPR/Cas9 technology (Supplementary Fig. 8a). The gRNA sequence is GGGGACACACTAAGGGAGCT. The Gt(ROSA)26Sor mice do not exhibit any abnormality, and have no expression of PRDX1-HA due to the existence of stop cassette. When mated with mice with a Cre recombinase, the stop cassette will be removed, and PRDX1 will be overexpressed driven by the CAG promoter. We bred the Gt(ROSA)26Sor mice with the Sf1-Cre+ mice to generate the mice with homozygous Stop-loxP and heterozygous Sf1-Cre (Sf1-Cre+, StoploxP/loxP), which will have specific PRDX1 overexpression in LCs (Supplementary Fig. 8). DNA was isolated from tail biopsies for genotyping via PCR with primers listed in Supplementary Table S1. All animal experiments were approved by the Ethical Committee for Animal Research of Southern Medical University (ethical review number: L2018073 for cKO, L2018074 for cOE mice), and conducted according to the Committee’s guidance.

Aging mice model induced by D-galactose

2-month-old C57BL/6J males were subcutaneously injected once daily with D-galactose (500 mg/kg/day; SG8010, Solarbio, Beijing, China). The control group received an equal volume of saline. The injections were administered consecutively for 2 months, and then the mice were euthanatized for sample collection.

Ebselen treatment

The aged Ctrl and Prdx1-cKO mice (19 months old) were intraperitoneally injected with ebselen (20 mg/kg/day; HY-13750, MedChemExpress, Elizabeth, NJ, USA.) once daily for 1 month. The control group received an equal volume of saline. Those mice having received D-galactose administration for 1 month were given simultaneous treatments with ebselen and D-galactose for another 1 month, then the mice were euthanized for sample collection.

Tissue collection and histology

Tissue collection and histological examination were performed as described in our previous study39,41,62,63,64. Briefly, brain and bone tissues were harvested following perfusion with 4% paraformaldehyde. Testes were fixed in modified Davidson’s fixative, and other tissues were directly fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. The fixed tissues were processed to paraffin sections, then stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) (G1120, Solarbio) for regular histological examination. Frozen sections were used for Oil Red O (IO1720, Solarbio) or BODIPY 493/503 (D3922, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) staining for lipid examination41, or for β-galactosidase staining (G1580, Solarbio) for cell senescence assessment.

Immunofluorescence was conducted as described in our previous study41,62,64. Images were captured using a FluoView FV1000 confocal microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The fluorescence intensity was quantified using the Image J software (1.53t, National Institutes of Health, USA).

Cell apoptosis assay

Cell apoptosis was evaluated using the terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assay for in situ detection of DNA fragmentation41,62,64, using a commercially available kit DeadEnd™ Fluorometric TUNEL System (G3250, Promega, Madison, WI,USA).

Quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was extracted (19221ES), reverse-transcribed into cDNA (11141ES), and amplified and quantified using a SYBR Green Master Mix (High Rox Plus) (11203ES; all from Yeasen) on a StepOne Plus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA). The relative expressions of genes were normalized to Gapdh level using the 2−ΔΔCt method. The primer sequences were listed in Supplementary Table S2.

Western blotting

Western blotting (WB) was performed as described in our previous study41,62,63,64,65. Briefly, tissue or cell lysates were prepared on ice using RIPA buffer. Protein concentrations were determined using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (C503021, Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China). The samples were then mixed with 2× sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) loading buffer with or without dithiothreitol (DTT; ST045, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) and boiled. Subsequently, proteins were resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (TM-NC-R−22, Labgic, Beijing, China). The membrane was then incubated with indicated primary antibodies (listed in Supplementary Table S3), followed by horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA, USA), visualized using an enhanced ECL chemiluminescent substrate kit (36222ES, Yeasen Biotechnology, Shanghai, China), and finally captured by GeneSys (syngene, Cambridge, UK) or Biorad (ChemiDoc MP, CA, USA). Band densitometry was performed by using the Image J software.

Sperm quality analysis and male fertility assessment